1. Introduction

The oceans cover more than 70% of the planet’s surface [

1], and their resources and uses are fundamental for humanity. Achieving sustainability requires effective spatial planning. Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) [

2], coordinated by IOC UNESCO [

3] and DG MARE [

4], ensures compatibility of uses and aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals [

5], supported by initiatives under the UN Decade of Ocean Science [

6] and the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy [

7,

8]. MSP applies an ecosystem-based approach to minimize conflicts and enhance resilience, addressing areas such as protected zones, fisheries, aquaculture, renewable energy, climate change, and activities in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction [

9].

Coastal zones, where nearly half of the global population reside [

10,

11], are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts. Yet terrestrial planning often excludes the sea, limiting integration to the public maritime domain. As a result, MSP and Terrestrial Spatial Planning (TSP) have evolved separately, producing fragmented governance. National maritime zoning practices vary across the Mediterranean, where diverse legal traditions and administrative structures coexist. This heterogeneity illustrates the challenges of coordinating marine and terrestrial competences, reinforcing the need for an integration framework capable of bridging governance gaps across multiple jurisdictions Frameworks such as Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) [

12] and national adaptation strategies have advanced coordination but remain focused on narrow coastal strips or country-specific contexts. This article addresses that gap by proposing a unified methodology for Integrated Spatial Planning (ISP), linking oceanic waters defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea [

13] with equivalent terrestrial areas under common administrative levels. ISP enables coherent governance, sustainability, and resilience, offering a replicable model for coastal regions worldwide.

National maritime zoning practices vary across the Mediterranean, reinforcing the need for an integration framework capable of aligning marine and terrestrial competences across heterogeneous administrative contexts

2. Main Global Organizations Involved in the Sustainable Development of the Ocean

IOC-UNESCO

UNESCO, a UN agency for education, science, and culture, contributes to the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda [

14]. Within it, the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC), founded in 1960 and composed of 150 Member States, coordinates the UN Decade of Ocean Science (2021–2030). Its mission is to promote cooperation, research, and capacity building for sustainable ocean management (IOC Statutes, Article 2.1) [

15]. The IOC emphasizes knowledge of oceanographic conditions to address climate, resources, hazards, pollution, and CO₂ absorption [

16]. Given the ocean’s scale, international collaboration is essential. IOC initiatives also highlight the economic relevance of marine activities (~5% of GDP in some economies) and the importance of investment in observation, science, and cooperation. Since the ratification of UNCLOS (1994), coastal States gained jurisdiction over waters up to 200 nautical miles.

Figure 1.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda.

Figure 1.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda.

Visual representation of the 17 SDGs that frame the global strategy for environmental, social, and economic sustainability. These goals provide a transversal reference for the integration of marine and terrestrial spatial planning (MSP–TSP), particularly in contexts of urban adaptation to climate change and coastal governance.

HIGH LEVEL PANEL FOR A SUSTAINABLE OCEAN ECONOMY

The Ocean Panel, composed of 19 heads of state and government, represents nearly 50% of global coastlines and 44% of exclusive economic zones. Its Call to Action urges governments and stakeholders to build a sustainable ocean economy [

17]. The Panel promotes Sustainable Ocean Planning, a strategic framework integrating policies, investments, and Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) to balance economic, social, and environmental sustainability. The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the need for cooperative responses to global threats, highlighting the Panel’s vision of aligning ocean health with long-term prosperity.

GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP FOR OCEANS [

18]

Launched in 2012 by the World Bank, the GPO united over 150 partners (governments, organizations, civil society, private sector) to restore ocean health. It targeted overfishing, pollution, and habitat loss, recognizing their impact on food security, livelihoods, and ecosystem services. Although the World Bank no longer serves as Secretariat, it continues to support financing, reforms, and programs such as PROFISH+ to strengthen ocean governance. The GPO remains a broad alliance committed to sustainable and productive oceans.

3. State of the Art of Marine Spatial Planning

Basic Concepts of MSP

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) is conceived by IOC-UNESCO as an integrative framework to address ocean governance challenges and promote sustainability. Ocean governance refers to the way ocean affairs are managed by governments, communities, and stakeholders, based on law, customs, and institutions [

19]. Key terminology is provided in the MSPglobal International Guide [

20]:

Coastal Zone: interface between land and sea, often managed through ICZM plans.

Ocean Domain: three-dimensional ocean space (surface, water column, seabed).

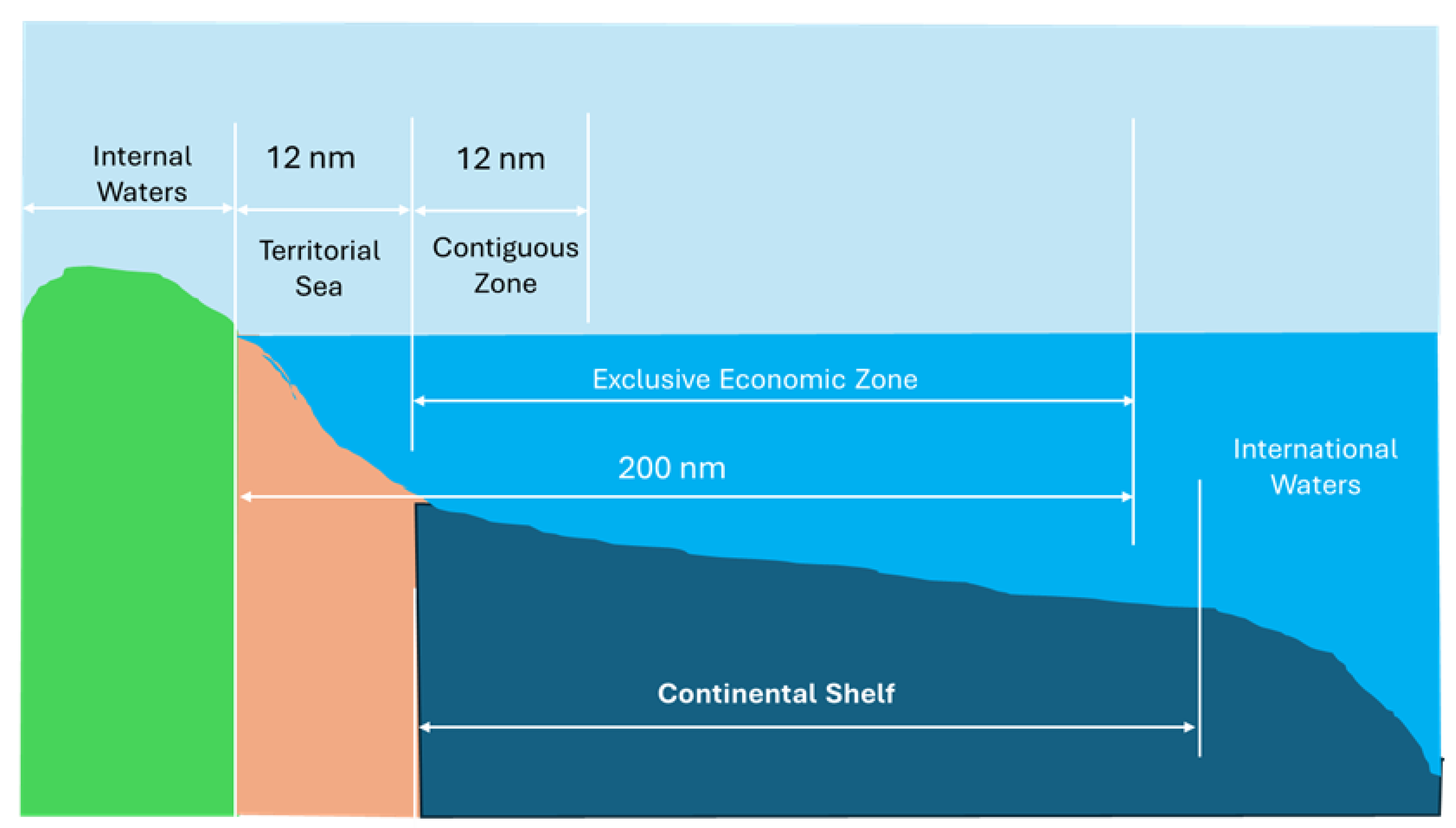

Maritime Boundaries: legal definitions under national and international law, covering territorial seas, EEZs, and continental shelves. Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ) remain without a planning authority. MSP is also linked to zone-based planning under United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) [

21] and the agreement on biodiversity in ABNJ [

22].

Figure 2.

-Legal Boundaries of the Oceans and Airspace. [

23].

Figure 2.

-Legal Boundaries of the Oceans and Airspace. [

23].

Diagram illustrating the maritime zones defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), including internal waters, territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone (EEZ), continental shelf, and international waters. These spatial boundaries establish the legal framework for coastal state jurisdiction and are essential for understanding the regulatory scope of marine spatial planning (MSP) in relation to terrestrial planning (TSP) and climate adaptation strategies. Definitions of MSP

IOC-UNESCO (2009) defines MSP as a public process for allocating human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives. The U.S. National Ocean Council (2013) emphasizes science-based planning for multiple uses [

24], while Directive 2014/89/EU establishes a framework for Member States to organize maritime activities for sustainable development [

25]. While all three definitions emphasize governance, stakeholder participation, and the balance between economic growth and conservation, they differ in scope and legal framing: IOC-UNESCO promotes a global, voluntary framework; the US National Ocean Council emphasizes domestic coordination and ecosystem services; and Directive 2014/89/EU establishes binding legal instruments for EU Member States, with a focus on cross-border coherence and integration with terrestrial planning.

Blue Economy

The ocean economy encompasses established sectors (fisheries, transport, tourism) and emerging ones (renewable energy, aquaculture, biotechnology). Growth is “brown” if unsustainable and “blue” when aligned with sustainability (Patil et al., 2018). MSP is considered a key enabler of the blue economy.

Ocean Multi-Use

Multi-use refers to intentional sharing of ocean space/resources across spatial, temporal, provisioning, or functional dimensions. It can be: polyvalent (independent uses), symbiotic (mutually beneficial), coexistence/co-location (simultaneous or alternating), or subsequent/re-use (sequential use of space/resources).

Marine Management

Sectoral regulation of activities at sea, including quotas, technical rules, transport regulations, and environmental protection measures.

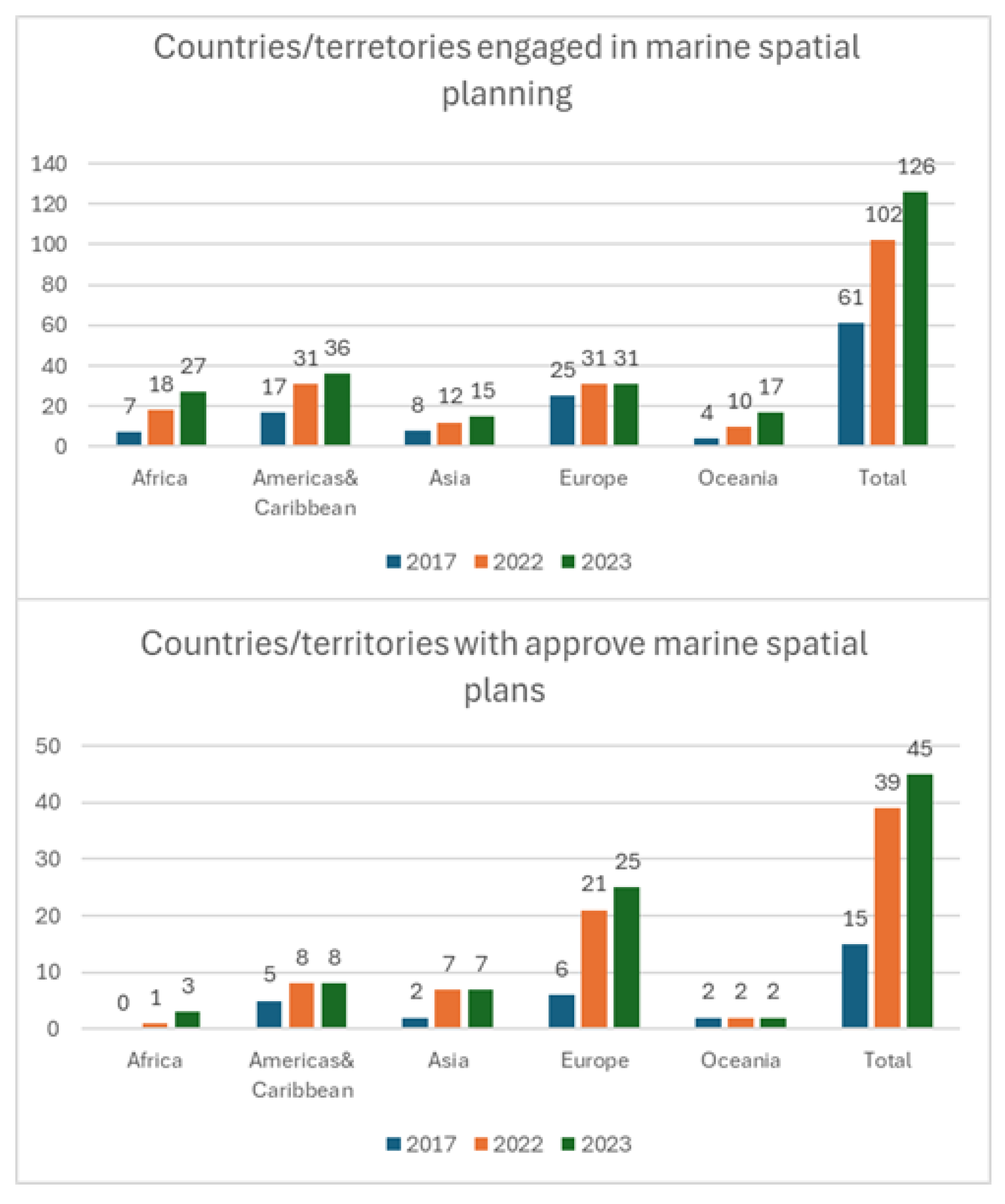

Figure 3.

- IOC-UNESCO assessments about marine spatial planning status around the world: a. Number of countries/territories engaged in MSP; and b. Number of countries/territories with approved marine spatial plans at national, subnational and/or local level. Source: IOC-UNESCO.

Figure 3.

- IOC-UNESCO assessments about marine spatial planning status around the world: a. Number of countries/territories engaged in MSP; and b. Number of countries/territories with approved marine spatial plans at national, subnational and/or local level. Source: IOC-UNESCO.

Sustainable Ocean Planning (SOP)

IOC-UNESCO defines SOP as a strategic framework guiding responsible management of marine areas, balancing economic, social, and environmental sustainability [

26]. SOP is characterized by inclusivity, integration, adaptability, place-based and ecosystem-based approaches, knowledge support, political backing, long-term financing, and adequate capacity.

SOP Program in the Ocean Decade [

27]

Launched to achieve 100% sustainable ocean planning, the program supports nations with tools, knowledge, and capacity development, emphasizing mission-oriented, collaborative, and equitable approaches. It fosters a global community of practice, particularly benefiting Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs).

Relationship Between MSP and Climate Change. Climate-Smart MSP [

28]

The integration of strategic climate objectives into general sustainable development and environmental policies related to the marine realm can be achieved through the use of a climate-smart and inclusive Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) as a common framework to establish meaningful and effective actions across all regions. This can be facilitated by establishing interdisciplinary MSP networks to develop climate-smart and inclusive design frameworks for ocean planning.

IOC-UNESCO’s Strategy on Sustainable Ocean Planning and Management [

29]

The importance of integrated ocean management is recognized in major international commitments, including the UN Sustainable Development Goals (especially Goal 14), the UNCLOS agreement on biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ), the UN Decade of Ocean Science, the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement, the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, and the Lisbon Declaration.

In response, IOC-UNESCO is developing a Strategy for Sustainable Ocean Planning and Management (SOPM) in consultation with member states and stakeholders. The Strategy seeks a unified approach to ocean governance, fostering cross-sector dialogue and alignment with global initiatives. It will build on and expand existing IOC programs such as MSPglobal, the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), and the International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IODE), alongside ocean science and tsunami initiatives.

The SOPM will serve as a guiding framework for IOC activities, supporting future observation, data management, early warning services, assessments, and the creation of innovative tools, knowledge products, and capacity-building initiatives tailored to sustainable ocean planning needs.

Relationship Between MSP and Climate Change. Climate-Smart MSP [

30]

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) is increasingly recognized as a climate-smart framework that integrates strategic climate objectives into sustainable development and marine environmental policies. By fostering interdisciplinary networks, MSP can design inclusive and adaptive approaches that strengthen resilience across regions.

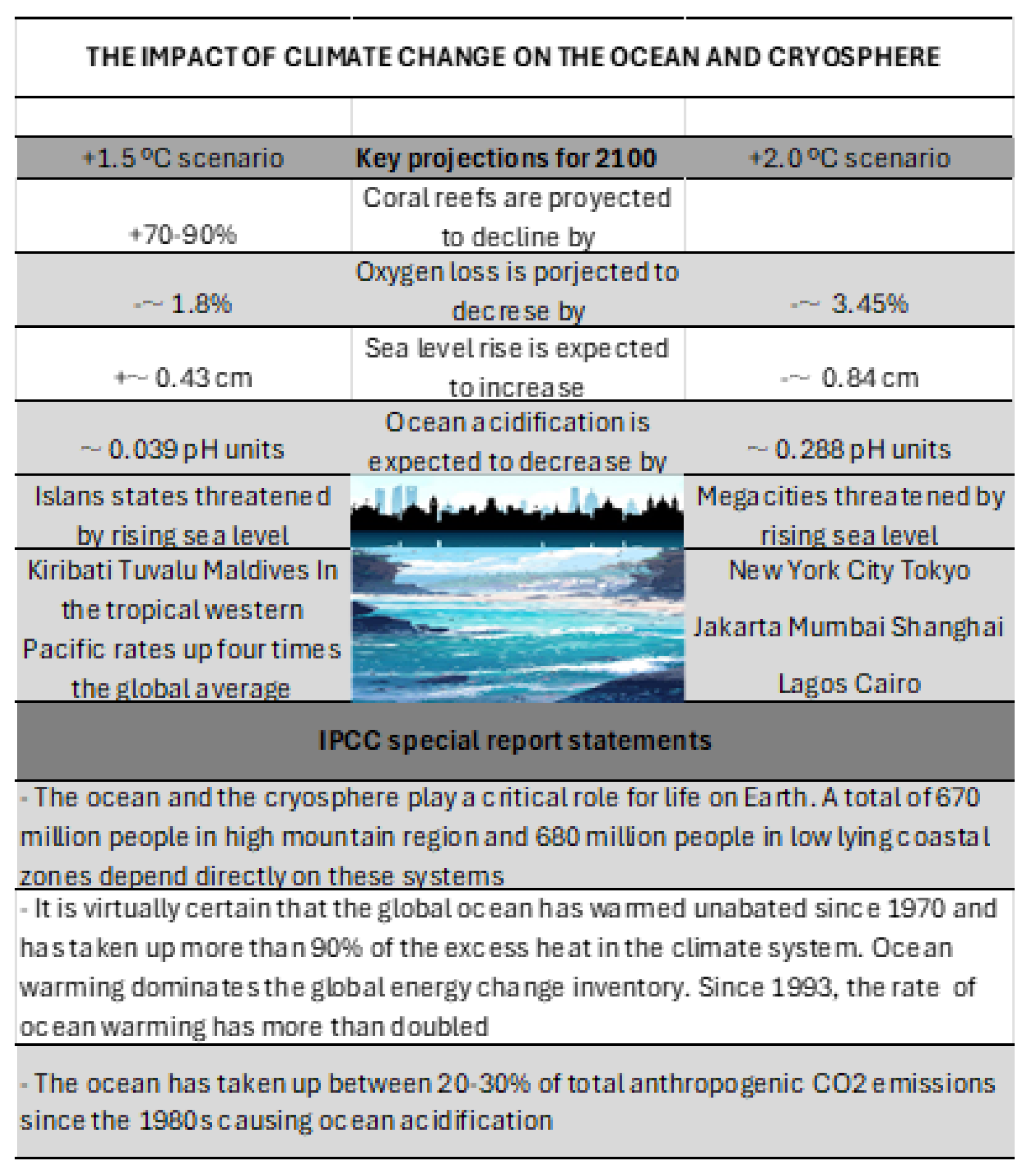

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the impacts of climate change on marine and coastal systems—such as ocean acidification, oxygen loss, and sea level rise—are projected to intensify significantly under a +2.0 °C scenario compared to +1.5 °C. These changes threaten both ecological integrity and human settlements, particularly in island states and megacities located in low-lying coastal zones. The figure underscores the urgency of embedding climate adaptation into spatial planning instruments across the land–sea interface.

Integrated Spatial Planning (ISP) builds on the climate-smart potential of MSP by extending its logic into terrestrial domains, enabling coherent governance across administrative levels. By aligning marine and terrestrial instruments, ISP ensures that climate resilience measures are not only designed but also implemented through binding, cross-sectoral planning frameworks.

Figure 4.

-Climate projections for 2100 under +1.5 oC and 2.0 oC scenarios.

Figure 4.

-Climate projections for 2100 under +1.5 oC and 2.0 oC scenarios.

This figure highlights key oceanic and coastal impacts of global warming, including oxygen loss, acidification, and sea level rise. It identifies vulnerable island states and megacities, reinforcing the need for Integrated Spatial Planning (ISP) to address land–sea interactions and enhance climate resilience. Source: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere.

Challenges in Incorporating Climate Change Impacts into MSP

Variable impacts: Climate change affects sectors, geographies, and scales differently, with cumulative effects from human activities [

31].

Knowledge gaps: Despite efforts to integrate climate change into spatial scenarios [

30], uncertainties remain due to complex processes [

32]. Studies must incorporate temporal evolution and scenarios [

33].

Uneven national responses: Adaptation capacities differ widely between developed and developing countries.

Climate-Smart MSP and Adaptive Capacity

A climate-smart MSP requires robust data on ecosystem impacts and human uses, combined with climate literacy and stakeholder knowledge. Inclusive design approaches [

34] enable dynamic governance. Crucially, integrated MSP–TSP planning strengthens adaptive capacity by linking land and sea management:

Flooding: Joint zoning of terrestrial and marine areas allows coordinated defenses (wetlands, dunes, breakwaters) that reduce flood risks.

Coastal erosion: Integrated planning aligns terrestrial land-use restrictions with marine ecosystem restoration, preventing maladaptive urban expansion.

Extreme events: Shared governance frameworks improve early warning systems and evacuation routes by connecting terrestrial infrastructure with marine hazard monitoring.

Recommendations for Action

Knowledge: Expand evidence on vulnerable uses and integrate relocation scenarios into MSP.

Policy: Embed climate objectives into sustainable development policies through climate-smart MSP and interdisciplinary networks.

Policy Actions in Europe and Spain

As an example of the political actions that have contributed to consolidating Marine Spa-tial Planning (MSP), some of the initiatives that have been carried out in Europe and also in Spain will be presented [

35]

The EU Directive 2014/89/EU [

35] established a framework for maritime spatial planning, transposed in Spain via Royal Decree 363/2017 [

37] under Law 41/2010 [

38]. This decree approved five maritime spatial plans, aligned with the European Green Deal [

38], Paris Agreement [

40], EU Climate Change Adaptation Strategy [

41], and EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2030 [

42]. Plans were developed with inter-administrative coordination and stakeholder participation.

Spain consolidated MSP with Royal Decree 150/2023 [

43], covering five marine regions (North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Strait and Alboran, Levantine-Balearic, Canary Islands) as defined in Law 41/2010 [

44]. These frameworks ensure sustainability of human activities at sea while directly supporting climate adaptation and risk reduction.

Figure 5.

The five marine regions defined by Spain’s Maritime Spatial Planning Plans (POEM).

Figure 5.

The five marine regions defined by Spain’s Maritime Spatial Planning Plans (POEM).

Spatial delineation of the five marine regions established under the POEM framework: Noratlántica, Sudatlántica, Canaria, Levantino-Balear, and Estrecho-Alborán. These regions reflect ecological, socio-economic, and administrative criteria, and serve as the operational basis for implementing MSP in Spain. Their definition is critical for coordinating marine and terrestrial planning processes in the context of climate adaptation and integrated coastal governance. Source: Executive Summary of the POEM. Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge.

4. State of the Art of Land Planning

Description of Land Planning

Land spatial planning is structured through instruments at national, regional, and local levels, depending on the scale of space being organized. While marine and land planning are based on state-specific legislation, here the focus is on common global aspects.

Definition of Territory

Unlike marine space, often public domain, land is predominantly private, especially in cities. Public space is reserved for infrastructures and services. Territory can be defined as a resource whose use requires programming and structuring under legal supervision [

45]. Planning is therefore organized around legal, political, economic, and social criteria.

Planning, Management, and Implementation

Urban growth, non-urban space planning, infrastructure integration, real estate development, and land market regulation are managed through scientific and technical criteria, forming the basis of urbanism and land planning.

Terrestrial Spatial Planning (TSP)

Land planning emerged as state policy in the 1930s, consolidating as a scientific discipline by the 1960s [

46]. In the U.S., the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Integrated Management Plan (1933) [

47], [

48] exemplified early comprehensive planning, addressing natural resources, energy, flood control, housing, and urban development. In Europe, land planning developed alongside urban planning: the UK, USSR, and France focused on large housing complexes, while Switzerland and Alpine countries prioritized accessibility and connectivity.

Land Planning in Europe

The European Charter for Territorial Planning (1983) established guiding principles: balanced regional development, improved quality of life and infrastructure, responsible resource management, and rational land use. Bengoetxea [

49] identifies different levels of planning based on territorial scope and approach. Land use planning is integrative, similar to MSP, addressing environmental, social, economic, infrastructural, and service-related issues. As Serrano (2001) notes, systemic management of space appropriation is essential to promote equity and sustainability, in line with the European Spatial Planning Charter.

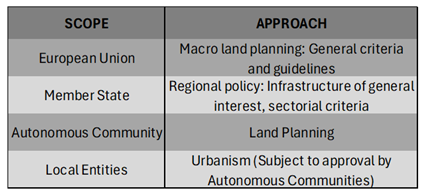

Table 1.

-Land Planning. Scope and Approach in Europe.

Table 1.

-Land Planning. Scope and Approach in Europe.

Overview of the hierarchical distribution of land planning responsibilities across governance levels in the European context. The table highlights the macro-level guidelines set by the European Union, the sectoral and infrastructural criteria defined by Member States, and the operational planning frameworks implemented by Autonomous Communities and Local Entities. This structure is essential for understanding the vertical coordination required in terrestrial spatial planning (TSP) and its integration with marine spatial planning (MSP). Source: Bengoetxea, 2000.

Land Use Planning Models in Europe [

50]

European land use planning reflects the political and administrative structures of each Member State, but shares common principles of sustainability and territorial balance.

United Kingdom: A unitary state with responsibilities divided among central government, counties, and municipalities. Since the 1990 Spatial Planning Act, planning emphasizes territorial balance and sustainability.

France: A unitary republic with decentralized powers since the 1980s. Regions, Departments, and Municipalities share responsibilities, with urban planning ultimately managed locally but integrated into broader frameworks [

51].

Germany: A federal state of sixteen Länder. Territorial planning is conducted at the federal level, implemented by states, and supported by municipalities and districts. Germany has been active in European territorial policy, contributing to the Leipzig Principles and the European Territorial Strategy [

52].

Spain: A unitary parliamentary monarchy with strong decentralization into 17 Autonomous Communities. The State retains authority over national laws and major infrastructures, while regions and municipalities manage planning. Coastal responsibilities are increasingly transferred to autonomous communities.

Italy: A unitary republic with strong regional decentralization. Regions hold exclusive competencies in land and urban planning, while the State retains authority over infrastructures of general interest, cultural heritage, and the environment [

53].

Conclusions on Land Use Management in the EU

The European Union has established guiding instruments: the European Spatial Planning Charter (1983), the European Territorial Strategy (1999) [

54],[

55], and the Guiding Principles for Sustainable Development (2005) [

54]. These emphasize territorial balance, sustainability, and environmental protection.

The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) [

56], created in 1975, addresses disparities among Member States, reflecting the coexistence of highly developed regions, developing regions, and Eastern Europe. Integration of efforts —such as the single currency and removal of internal borders—aim to strengthen territorial cohesion and competitiveness.

The European Spatial Planning Commission defines land use planning as the spatial expression of economic, social, cultural, and ecological policies, conceived as an interdisciplinary and holistic approach (Parejo, 2003). Overall, the EU approach is integrative, ensuring legal security, sustainability, and territorial balance.

SYSTEMATICS IN LAND USE PLANNING

Land use planning is structured through a hierarchy of instruments that operate at different levels (state, regional, municipal), ensuring systematic territorial organization [

57].

Territorial Development Plans: Regional or municipal strategies that set objectives and frameworks for spatial organization.

Coordination Programs: Align actions of public administrations with significant territorial impact.

Natural and Rural Land Use Plans: Protect and enhance areas of ecological, agricultural, or landscape value; in coastal regions, specific coastal land use plans regulate beaches and maritime fronts.

Regional Interest Actions: Exceptional instruments for urgent or strategic development.

Municipal Land Use Plans: Local strategic plans integrated into regional frameworks, ensuring coherence across scales.

Territorial Impacts of Sectoral Legislation Sectoral laws (coasts, water, forests, protected areas, roads, railways, airports, energy transport) [García-Ayllón, 2014] have hierarchical precedence over urban planning laws, requiring integration into territorial planning.

Urban Planning Instruments at Municipal Level Municipalities apply General Urban Planning Plans, classifying land as non-urbanizable, urbanizable (sectorized/non-sectorized), or urban (consolidated/non-consolidated/special). Development tools include:

General Urban Planning Plan

Development Planning

Partial Plans (zoning, land uses, building typologies)

Special Plans and Detail Studies (specific regulations)

Urbanization projects (infrastructure, mobility, green areas)

This system ensures territorial organization balances strategic development with ecological, social, and infrastructural considerations.

5. Materials and Methods

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) and Terrestrial Spatial Planning (TSP) have developed as distinct disciplines, each with its own instruments, scales, and institutional frameworks. The aim of this research is to propose a methodology for their integration, creating a unified system that can address the complexity of land–sea interactions. While at first glance integration may appear straightforward at the level of planning tools, in practice it presents significant challenges due to differences in governance structures, administrative competences, and the historical trajectories of both systems.

MSP has emerged more recently, often under the guidance of international frameworks such as MSPglobal (UNESCO-IOC/European Commission, 2021). It emphasizes the articulation of marine uses and the sustainable management of ecosystems. TSP, by contrast, has a longer history, with instruments ranging from national territorial strategies to detailed municipal urban plans. The convergence of these systems is particularly relevant in coastal zones, where boundaries between land and sea are blurred and where socio-economic activities and natural processes are tightly interwoven.

Land–sea interactions are central to this integration. They can be understood both environmentally—through processes such as sediment transport, nutrient flows, or coastal erosion—and economically, through activities such as port operations, aquaculture, or tourism [

58],[

59] & [

60]. Literature offers multiple definitions, but all converge on the idea of complex, evolving interconnections between socio-ecological systems and governance frameworks [

61],[

62],[

63] & [

64]. Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) and MSP are therefore complementary instruments that, when combined, provide a privileged mechanism for sustainable development of coastal and marine areas [

65], [

66], [

67] & [

68].

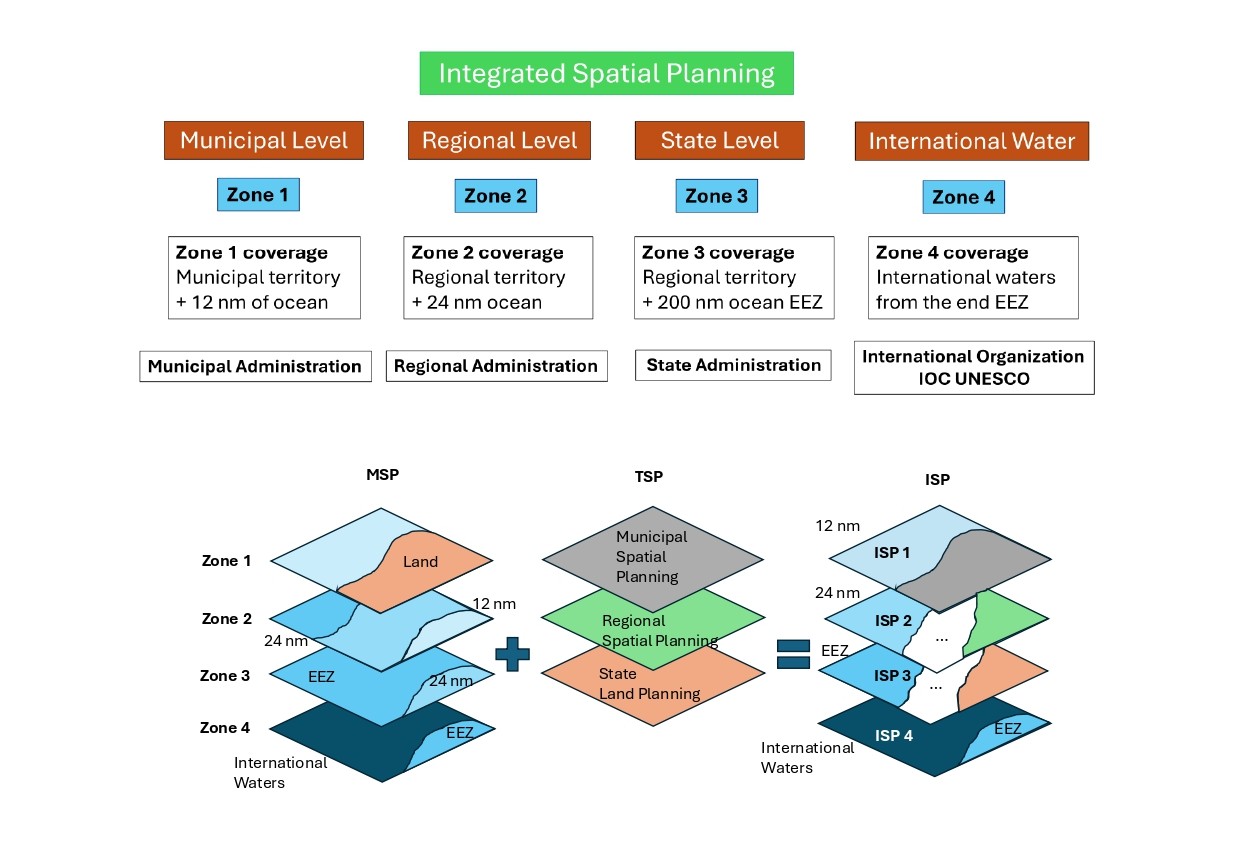

The methodology adopted here distinguishes four marine zones based on distance from the baseline: internal waters and territorial sea (Zone 1), contiguous zone (Zone 2), Exclusive Economic Zone (Zone 3), and international waters (Zone 4). Each zone is associated with a corresponding level of governance: municipal, regional, national, and international. This zoning provides the foundation for integration, ensuring that responsibilities are aligned with existing administrative structures.

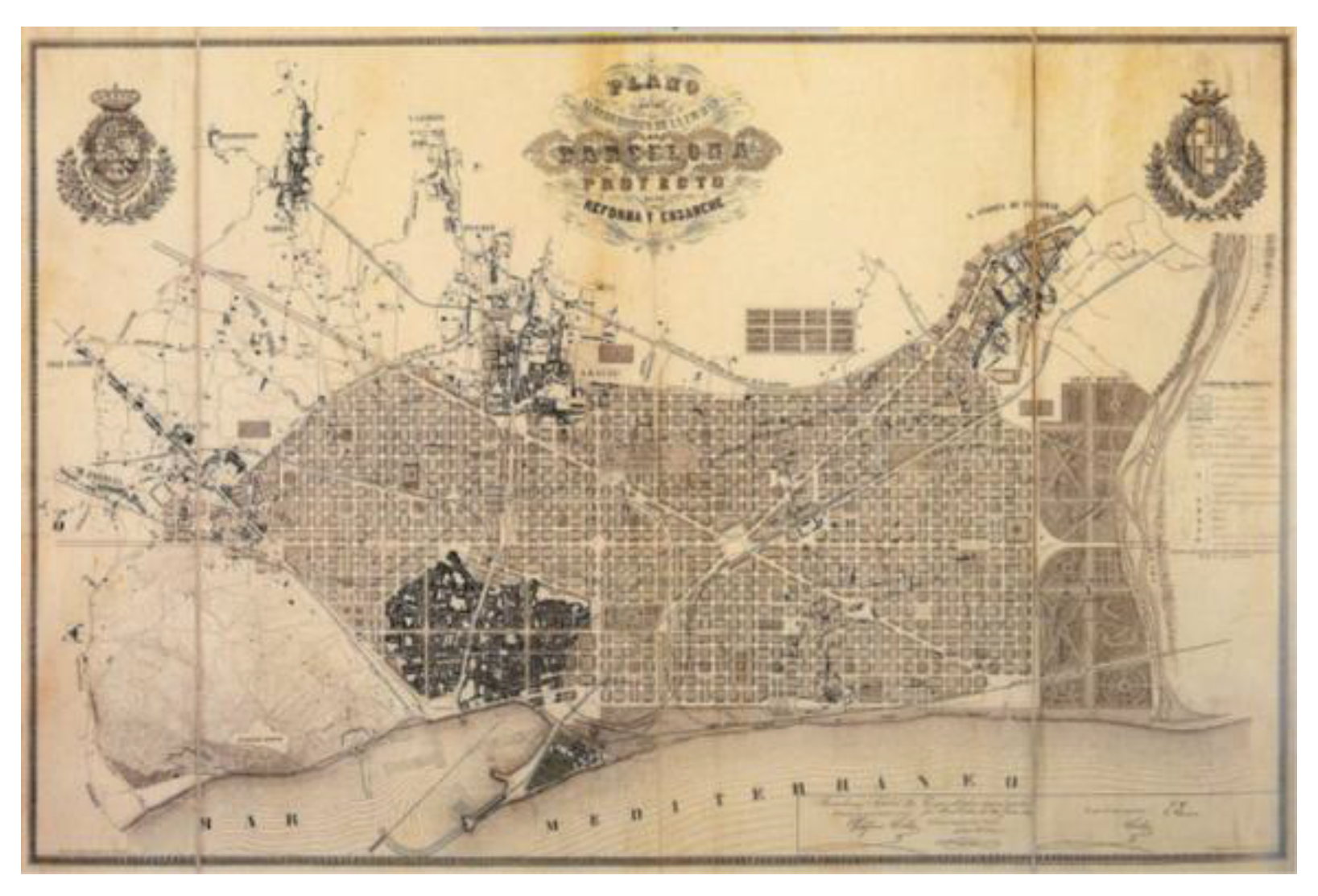

Figure 6.

The Cerdá Plan in Barcelona.

Figure 6.

The Cerdá Plan in Barcelona.

Historical map of Barcelona and its surroundings, illustrating the urban layout proposed by Ildefonso Cerdà in the mid-19th century. Despite his background as a Civil, Canal and Port Engineer, Cerdà’s visionary plan for the city was conceived with limited integration of the coastal interface, reflecting a historical disconnection between urban development and maritime spatial considerations. Source: City History Museum, Barcelona.

6. Results. Integrated Spatial Planning

Applying a top-down approach, integration is conceived from the most general to the most specific level. In international waters (Zone 4), MSP is governed by IOC-UNESCO frameworks, defining maritime routes, energy extraction, submarine cables, and offshore mining. These activities must be spatially organized within sustainability criteria, supported by monitoring stations and predictive models based on advanced AI techniques.

Within the Exclusive Economic Zone (Zone 3), national administrations hold responsibility. Here, integration requires a single document that combines MSP with state-level TSP instruments, covering transport networks, ports, energy grids, and communication systems. Similar methodologies for environmental monitoring and climate adaptation are applied, ensuring coherence between terrestrial and marine domains.

At the regional scale (Zone 2), territorial planning instruments—such as regional strategies, coastal plans, and action programs—must incorporate MSP elements. This integration ensures that supra-municipal infrastructures and uses are coordinated across land and sea.

Finally, at the municipal scale (Zone 1), General Urban Development Plans (GUDP) must extend into the maritime domain up to 12 nautical miles. These plans should integrate ICZM documents and MSP guidelines, addressing land–sea interactions directly. Importantly, the temporal dimension must be incorporated: integrated plans must anticipate climate change scenarios, including sea level rise, coastal retreat, and extreme events [Negro, Vicente, et al 2018]. Adaptive planning models are therefore essential, conditioning municipal development to evolving coastal configurations.

7. Discussion

The integration of MSP and TSP is not merely a technical exercise; it is fundamentally a matter of governance. Effective territorial governance requires coherence across scales: municipal authorities must manage urban growth and coastal discharges; regional administrations must coordinate infrastructures and environmental strategies; and national governments must regulate state-level uses within the EEZ. Without integration, responsibilities are fragmented, leading to inefficiencies and conflicts.

Figure 7.

Example of the PATRICOVA cartographic viewer. [69].

Figure 7.

Example of the PATRICOVA cartographic viewer. [69].

Screenshot of the digital cartography platform developed by the Generalitat Valenciana, displaying territorial layers related to urban planning, climate change exposure, and coastal dynamics. In addition to fluvial flood risk, the viewer integrates spatial analysis of extreme maritime storm events and the coastal inundation they produce. This tool exemplifies the use of geospatial platforms to support integrated land planning and climate adaptation strategies in vulnerable coastal zones. Source [https://mediambient.gva.es/es/web/planificacion-territorial-e-infraestructura-verde/cartografia-del-patricova]

Governance and institutional challenges

Institutional overlaps are among the most significant barriers. Sectoral legislations—covering coasts, water, energy, or transport—often have hierarchical precedence over urban planning laws, creating inconsistencies. Political barriers also arise from decentralization processes, where competences are distributed unevenly among levels of government. To address these challenges, integrated governance mechanisms are required: Inter-administrative coordination mechanisms (mixed land–sea committees).

Inter-administrative committees that bring together municipal, regional, and national authorities.

Unified legal instruments that harmonize sectoral regulations within integrated spatial plans.

Shared GIS platforms for transparency and cooperation.

Stakeholder participation to legitimize decisions and reduce conflicts.

Recent studies confirm that governance fragmentation and institutional segmentation remain critical obstacles for MSP implementation worldwide, reinforcing the need for integrative frameworks that bridge terrestrial and marine competences [

70], [

71].

Climate resilience

Integrated planning is also a tool for climate resilience. Flooding, erosion, and extreme events cannot be managed effectively if land and sea are treated separately. Joint defences—such as wetlands, dunes, and breakwaters—must be coordinated with marine ecosystem restoration. Early warning systems must integrate terrestrial and marine data, providing comprehensive risk management [

72], [

73] & [

74]. The integration of climate adaptation measures into binding spatial instruments is consistent with recent findings that emphasize the importance of overcoming spatial segmentation to reduce vulnerability in coastal regions [

75].

Case study: Region of Murcia

The Region of Murcia provides a particularly illustrative example of the operational potential of Integrated Spatial Planning (ISP). Located in the southeastern Iberian Peninsula, Murcia combines a highly urbanized coastal strip, intensive agricultural hinterlands, and ecologically sensitive marine environments such as the Mar Menor. This complexity makes it an ideal testing ground for the integration of Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) and Terrestrial Spatial Planning (TSP).

Current Frameworks

Murcia’s terrestrial planning system is governed by the Regional Land and Urban Planning Law [

76], which establishes the hierarchy of territorial and municipal instruments. At the municipal level, General Urban Development Plans (PGOU), such as those of Cartagena and San Pedro del Pinatar, incorporate measures for coastal adaptation and urban growth management [

77]. At the regional scale, the Territorial Strategy of Murcia [

78] provides a framework for supra-municipal coordination, while the Mar Menor Integrated Management Plan [

79] specifically addresses the ecological crisis of Europe’s largest coastal lagoon.

On the marine side, the Levantine Bareal Marine Spatial Plan (POEM) [

80], approved by the Ministry for Ecological Transition, defines spatial allocations for uses such as navigation, fishing, aquaculture, and offshore renewable energy. Complementary instruments include the Regional Climate Change Strategy [

81], which sets adaptation targets across sectors, and the Segura River Basin Hydrological Plan [

82], which regulates water resources and agricultural discharges. Finally, the Regional Coastal Adaptation Guidelines [

83] provide technical recommendations for managing erosion, flooding, and sea level rise.

Together, these instruments form a robust but fragmented framework. Each addresses specific domains—urban growth, water management, marine uses, or climate adaptation—but they remain largely disconnected.

Existing Gaps

Despite the breadth of instruments, several critical gaps emerge due to the absence of a unified ISP framework:

1.- Fragmented Governance: Municipal PGOU documents regulate land use up to the maritime-terrestrial boundary, while the POEM governs marine uses beyond it. This division leaves the first 12 nautical miles (Zone 1) subject to overlapping competences without a single integrated plan.

2.- Agricultural Runoff and Water Quality: The Segura Basin Plan regulates discharges, but its measures are not systematically linked to marine ecosystem objectives in the POEM. The result is persistent nutrient inflows into the Mar Menor, causing eutrophication and ecological degradation.

3.- Port and Coastal Infrastructure: Port expansions and coastal defences are planned under separate terrestrial and marine frameworks. Without integration, cumulative impacts on sediment transport, erosion, and biodiversity are poorly assessed.

4.- Renewable Energy Development: The POEM identifies offshore wind and other marine renewable energy zones, but these are not coordinated with regional land-use strategies or municipal PGOU. This creates uncertainty in transmission infrastructure planning and stakeholder acceptance.

5.- Climate Adaptation: While the Regional Climate Change Strategy and Coastal Guidelines provide adaptation measures, they are not embedded into binding urban or marine plans. This weakens their effectiveness in guiding development decisions.

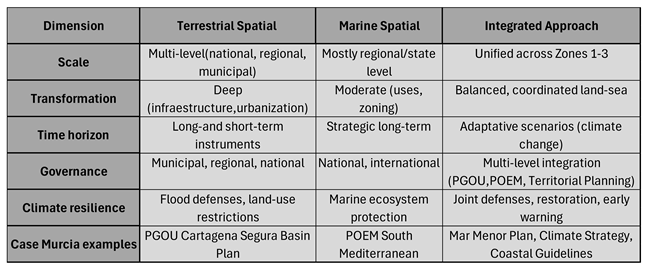

Table 2.

Comparative MSP vs TSP and Integrated Spatial Planning (ISP) in Murcia.

Table 2.

Comparative MSP vs TSP and Integrated Spatial Planning (ISP) in Murcia.

Synthesis of key dimensions across marine spatial planning (MSP), terrestrial spatial planning (TSP), and an integrated approach (ISP) in the Region of Murcia. The table compares scale, transformation intensity, time horizon, governance structures, climate resilience strategies, and applied case examples. It highlights the potential for coordinated land–sea planning to enhance adaptive capacity and regulatory coherence in coastal territories.

How ISP Would Address These Gaps

The adoption of an Integrated Spatial Planning framework would directly address these shortcomings by creating a single, multi-scale planning document that unifies terrestrial and marine domains.

Zone 1 (0–12 nm): Municipal PGOU documents would be extended seaward, incorporating MSP guidelines. This would ensure that discharges, coastal defences, and tourism activities are managed holistically. For example, Cartagena’s PGOU could integrate measures from the Mar Menor Plan and Coastal Guidelines, aligning urban growth with lagoon restoration.

Zone 2 (12–24 nm): Regional instruments such as the Territorial Strategy would explicitly include marine uses defined in the POEM. This would allow agricultural policies, water management, and offshore energy planning to be coordinated at the regional scale, reducing conflicts between sectors.

Zone 3 (24–200 nm): National planning would integrate POEM allocations with state-level infrastructures. Transmission lines for offshore wind farms, for instance, would be planned jointly with terrestrial energy grids, ensuring efficiency and minimizing environmental impacts.

Cross-cutting Climate Adaptation: ISP would embed the Regional Climate Change Strategy into binding land and marine plans. This would guarantee that adaptation measures—such as setback lines, ecosystem restoration, and resilient infrastructure—are not merely advisory but enforceable.

Expected Benefits

By filling these gaps, ISP would deliver multiple benefits:

Ecological Restoration: Coordinated land–sea management would reduce nutrient inflows into the Mar Menor, supporting recovery of its ecosystems.

Infrastructure Coherence: Ports, coastal defences, and renewable energy projects would be planned within a unified framework, minimizing cumulative impacts.

Governance Efficiency: Overlaps between municipal, regional, and national competences would be clarified, reducing conflicts and delays.

Climate Resilience: Binding adaptation measures would strengthen Murcia’s capacity to withstand flooding, erosion, and sea level rise.

Stakeholder Confidence: Farmers, fishers, tourism operators, and energy developers would benefit from transparent, integrated planning processes.

Governance Transformation in the Region of Murcia

One of the most significant challenges for the Region of Murcia lies in the fragmentation of governance across different administrative levels. At present, responsibilities are divided among municipal governments, the regional administration, and the national state, with additional oversight from European and international bodies. While each level has developed instruments to regulate land or marine uses, the absence of an integrated framework results in overlaps, gaps, and inefficiencies.

At the municipal level, General Urban Development Plans (PGOU) regulate land use and urban growth, but their jurisdiction ends at the maritime-terrestrial boundary. This artificial limit prevents municipalities from managing activities that directly affect their coasts, such as discharges, aquaculture, or tourism infrastructure. To implement ISP, municipal plans would need to be formally extended into the first 12 nautical miles, incorporating MSP guidelines from the POEM and ecological measures from the Mar Menor Plan. This change would empower municipalities to manage land–sea interactions holistically, while still subject to regional and national supervision.

At the regional level, the Autonomous Community of Murcia holds competences in territorial planning through the Regional Land and Urban Planning Law and the Territorial Strategy. However, marine competences are limited, as MSP is primarily regulated at the national level. ISP would require the regional administration to assume a coordinating role, integrating terrestrial strategies with marine allocations defined in the POEM. This would involve creating a Regional Land–Sea Planning Authority, tasked with harmonizing agricultural policies (Segura Basin Plan), climate adaptation measures, and coastal guidelines with marine uses such as aquaculture and renewable energy.

At the national level, the General State Administration governs the EEZ through the POEM and sectoral laws on ports, energy, and transport. Yet coordination with regional and municipal authorities is often weak, leading to conflicts over infrastructure siting and resource management. ISP would require the creation of joint governance mechanisms, such as inter-administrative committees, where national ministries, the regional government, and municipal representatives jointly approve integrated plans. This would ensure that state-level infrastructures (ports, transmission lines, offshore wind farms) are aligned with regional and local priorities.

Finally, at the European and international level, directives such as the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive and IOC-UNESCO guidelines provide overarching principles but are not directly embedded into Murcia’s planning instruments. ISP would require systematic incorporation of these frameworks into regional and municipal plans, ensuring compliance with European sustainability targets and international maritime governance.

In summary, governance transformation in Murcia would involve:

Extending municipal competences into the maritime domain (Zone 1).

Establishing a Regional Land–Sea Planning Authority to coordinate terrestrial and marine policies (Zone 2).

Creating inter-administrative committees to align national infrastructures with regional and local priorities (Zone 3).

Embedding European and international frameworks into binding regional and municipal instruments (cross-cutting).

Such reforms would not replace existing institutions but rather complement and integrate them, creating a coherent governance architecture capable of managing land–sea interactions and climate resilience in a unified manner.

Conclusion of the Case Study: Region of Murcia

The Region of Murcia illustrates both the opportunities and the limitations of current spatial planning frameworks. On the one hand, the region benefits from a wide array of instruments—municipal PGOU documents, the Regional Land and Urban Planning Law, the Territorial Strategy, the Mar Menor Integrated Management Plan, the Regional Climate Change Strategy, the Segura River Basin Hydrological Plan, and the Regional Coastal Adaptation Guidelines. On the other hand, these instruments remain fragmented, each addressing a specific domain without a unifying framework that bridges land and sea.

The absence of Integrated Spatial Planning (ISP) manifests in several critical gaps: disconnection between agricultural runoff management and marine ecosystem objectives, lack of coherence in port and coastal infrastructure planning, uncertainty in offshore renewable energy development, and weak embedding of climate adaptation measures into binding plans. These gaps undermine the effectiveness of existing policies and perpetuate ecological and governance challenges, particularly in the Mar Menor.

By introducing ISP, Murcia could transform these fragmented instruments into a coherent governance architecture. Municipal PGOU documents would extend into the maritime domain, regional authorities would coordinate terrestrial and marine strategies through a dedicated Land–Sea Planning Authority, and national infrastructures would be aligned with local and regional priorities via inter-administrative committees. European and international frameworks would be systematically embedded into regional and municipal instruments, ensuring compliance and coherence across scales.

The expected benefits of such integration are substantial: ecological restoration of the Mar Menor, improved coherence of infrastructure planning, enhanced governance efficiency, strengthened climate resilience, and greater stakeholder confidence. Yet these benefits cannot be achieved without governance transformation. ISP requires not only technical integration of planning instruments but also institutional reform—expanding competences, creating new coordinating bodies, and embedding adaptation measures into binding regulations.

In conclusion, Murcia demonstrates that Integrated Spatial Planning is both necessary and feasible. It offers a pathway to overcome fragmentation, align governance levels, and embed climate resilience into territorial management. As such, Murcia stands as a replicable model for Mediterranean and global coastal regions, showing how ISP can move from conceptual innovation to operational practice, ensuring sustainable development and adaptive governance in the face of climate change.

8. General Conclusions

The sustainable and integrated use of terrestrial and marine space represents one of the most pressing challenges of contemporary governance. While Terrestrial Spatial Planning (TSP) has evolved historically to provide sophisticated instruments for land management, Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) remains a relatively recent discipline, often lacking smaller-scale tools and clear integration with terrestrial frameworks. This disjunction has led to fragmented governance, inefficiencies, and partial solutions to problems that are inherently interconnected.

The methodology proposed in this article—Integrated Spatial Planning (ISP)—addresses these shortcomings by unifying MSP and TSP across governance levels. ISP is conceived as a multi-scale framework, extending from international waters under IOC-UNESCO guidance to national EEZs, regional administrations, and municipal authorities. By embedding the temporal dimension of climate change into planning instruments, ISP ensures that adaptive scenarios, resilience measures, and ecosystem sustainability are systematically incorporated into decision-making.

The case study of the Region of Murcia demonstrates the operational applicability of ISP. Despite the existence of numerous instruments—PGOU documents, the Regional Land and Urban Planning Law, the Territorial Strategy, the Mar Menor Integrated Management Plan, the Regional Climate Change Strategy, the Segura River Basin Hydrological Plan, and the Coastal Adaptation Guidelines —their fragmentation undermines effectiveness. Agricultural runoff continues to degrade the Mar Menor, port and coastal infrastructures are planned in isolation, renewable energy development lacks coherence with terrestrial strategies, and climate adaptation measures remain largely advisory.

By introducing ISP, these gaps can be closed. Municipal plans would extend into the maritime domain, regional authorities would coordinate terrestrial and marine strategies through a dedicated Land–Sea Planning Authority, and national infrastructures would be aligned with local priorities via inter-administrative committees. European and international frameworks would be systematically embedded into binding instruments. The expected benefits include ecological restoration, infrastructure coherence, governance efficiency, climate resilience, and stakeholder confidence.

Ultimately, the Murcia case illustrates that ISP is not only a conceptual innovation but also a practical governance reform agenda. It demonstrates how integration can move from theory to practice, offering a replicable model for Mediterranean and global coastal regions. ISP provides a holistic vision of the environment, treating land and sea as a single entity, and ensuring that socio-economic development is compatible with ecosystem sustainability.

In conclusion, Integrated Spatial Planning emerges as a necessary evolution of spatial governance. It strengthens resilience to climate change, clarifies institutional responsibilities, and provides a framework for sustainable growth in coastal territories. By bridging the divide between MSP and TSP, ISP offers a pathway towards adaptive, coherent, and sustainable governance—one that is urgently needed in the face of accelerating environmental and socio-economic pressures.

Author Contributions

F.J.C.D contributed to the work described in this paper by carrying out the analysis and evolution of Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) throughout the history. Comparing current standards followed by the experts in international organization for developing Marine Spatial Planning and the common characteristics of Terrestrial Spatial Planning in different countries and proposing a methodology for the integration of both: Marine (MSP) and Terrestrial Spatial Planning (TSP). V.N.V contributed organizing the development of the article, clarifying specialized concepts and introducing the relationships between climate change and the Spatial Planning, both marine and terrestrial. G.G.P, J.J.M and L.J.M.B. contributed with knowledgeable discussion and suggestion.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript, in order of appearance:

| MSP |

Marine Spatial Planning |

| TSP |

Terrestrial Spatial Planning |

| ECOREL |

Environment, Coast and Ocean Research Laboratory |

| CASEM |

Andalusian Centre for Maritime Studies |

| ISP |

Integrated Spatial Planning |

| IOC |

Intergovernmental Ocean Commission |

| UNESCO |

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| OCEAN PANEL |

High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy |

| GPO |

Global Partnership for Oceans |

| DG MARE |

Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

OCEAN

DECADE |

United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development |

| ABNJ |

Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| GDP |

Gross Development Product |

| SOP |

Sustainable Ocean Planning |

| SIDS |

Small Island Developing States |

| LCDs |

Least Developed Countries |

| BBNJ |

Biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction |

| UNFCCC |

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| SOPM |

Sustainable Ocean Planning and Management |

| GOOS |

Global Ocean Observing System |

| IODE |

International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange |

| EZZ |

Exclusive Economic Zones |

| UNEP |

United Nations Environmental Program |

| PAP/RAC |

Priority Actions Program/ Regional Activity Centre |

| ESPON |

European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion |

| ICZM |

Integrated Coastal Zone Management |

| GIS |

Geographic Information System |

References

- https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/ceneam/recursos/mini-portales-tematicos/reeducamar/abc-mar-principio1.html.

- https://www.ioc.unesco.org/en/marine-spatial-planning.

- https://www.ioc.unesco.org/en.

- https://commission.europa.eu/about/departments-and-executive-agencies/maritime-affairs-and-fisheries_en.

- https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- https://www.unesco.org/en/decades/ocean-decade.

- https://oceanpanel.org/.

- https://oceanpanel.org/call-to-action/.

- https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-09/ocean_and_waters_implementation_plan_for_publication.pdf.

- https://www.ipcc.ch.

- https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/cambio-climatico/temas/impactos-vulnerabilidad-y-adaptacion/executivesummary_informeevaluacionpnacc_tcm30-499189.pdf.

- European Parliament and Council Recommendation (2002/413/EC): Recommendation concerning the implementation of Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Europe. Official Journal L 148, 6 June 2002, pp. 24–27.

- https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

- https://www.unesco.org/en/brief.

- Statuts. Commission océanographique intergouvernementale, IOC). Collective author: IOC, [6611]. Document code: IOC/INF/1148, SC.2000/WS/57, 2000. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000124367.locale=en.

- IOC Brochure 2016-4, IOC/BRO/2016/4 REV, 2016. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000246085.

- https://oceanpanel.org/progress-report/the-journey.

- http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/737341637821958000/Global-Partnership-for-Oceans-GPO.

- BORGESE, E. M. 2001. Ocean Governance. Halifax (Canada), International Ocean Institute.

- Corporate author: IOC UNESCO, MSPglobal International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning. Directorate General for Fisheries and Maritime Affairs. IOC Manual and Guides, 89. Document code: IOC/2021/MG/89. ISBN: 978-84-09-33197-0, 2021. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379196.

- https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

- Official Journal of the European Union, no. 1962, July 19, 2024, pages 1 to 45 of the Eu-ropean Union: DOUE-L-2024-81141. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec/2024/1830/oj/eng.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366986362_Governing_the_Global_Commons_Challenges_and_Opportunities_for_US-Japan_Cooperation/figure.

- https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/final_marine_planning_handbook.pdf.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/89/oj/eng.

- https://www.ioc.unesco.org/en/sustainable-ocean-planning.

- https://oceandecade.org/actions/ocean-decade-programme-on-sustainable-ocean-planning/.

- VASSILOPOULOU, VASSILIKI, IOC policy brief, Licence type CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO, 2021. https://oceanexpert.org.

- IOC- UNESCO Draft IOC-Wide Strategy on Sustainable Ocean Planning and Management, IOC/EC-57/4.3. Doc(1) Rev. Paris, 3 June 2024., https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000375721.

- QIANG H. AND SILLIMAN, B.R. 2019. Climate Change, Human Impacts, and Coastal Ecosystems in the Anthropocene, Current Biology, Vol. 29, 19, p. R1021-R1035. [CrossRef]

- FRAZAO-SANTOS et al, 2020, Integrating climate change in ocean planning. Nature Sustainability, 3, p. 505-506. [CrossRef]

- RILOV et al,202. A fast-moving target: achieving marine conservation goals under shifting climate and policies. Ecological Applications 30 (1). [CrossRef]

- NEGRO, VICENTE; et al (2018) Action Strategy for Studying Marine and Coastal Works with Climate Change on the Horizon. Journal of Coastal Research, Special Issue No. 85, pp. 506–510.

- TENNET. 2019. Stakeholder consultation and nature inclusive design of the offshore grid. http://ecoadapt.org/data/documents/EcoAdapt_USFS_SoCal_Webinars_Mar2017_small.pdf.

- CORDOBA-DONADO et al (2024) Integration of Marine Spatial Planning and Terrestrial Spatial Planning and its implementation in Spain. JSM Environmental Science and Ecology. SciMedCentral. Vol. 12/ Issue 2 ISSN: 2333-7141. https://www.jscimedcentral.com/jounal-article-info/JSM-Environmental-Science-and-Ecology/Integration-of-Marine-Spatial-Planning-and-Terrestrial-Spatial-Planning-and-its-implementation-in-Spain-11855#.

- DIRECTIVE 2014/89/EU OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL OF 23 JULY 2014 establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning.

- ROYAL DECREE 363/2017, OF APRIL 8th, which establishes a framework for maritime spatial planning and ordered the approval of five maritime space management plans, one for each of the Spanish marine regions.

- LAW 41/2010, OF DECEMBER 29th, on the protection of the marine environment.

- THE EUROPEAN GREEN DEAL (EGD), APPROVED IN 2020, is a set of policy initiatives of the European Commission with the overall objective of making the European Union (EU) climate neutral by 2050.

- THE PARIS AGREEMENT, SIGNED ON APRIL 22nd, 2016. Is an agreement within the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that establishes measures to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The agreement seeks to maintain the increase in global temperature average below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and effects of climate change.

- https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2050-long-term-strategy_en. Striving to become the world's first climate-neutral continent by 2050.

- https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en. The EU’s biodiversity strategy for 2030 is a comprehensive, ambitious and long-term plan to protect nature and reverse the degradation of ecosystems. The strategy aims to put Europe's biodiversity on a path to recovery by 2030 and contains specific actions and commitments.

- ROYAL DECREE 150/2023, OF FEBRUARY 28th, 2023, approving the maritime spatial management plans of the five Spanish marine regions.

- Executive summary of the POEM. Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/costas/temas/proteccion-medio-marino/4resumenejecutivopoem_tcm30-552786.pdf.

- GARCÍA-AYLLÓN VEINTIMILLA, SALVADOR (2014) Urbanismo y ordenación del territorio. Manual de teoría. Escuela Universitaria de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos. Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena.

- SANÁBRIA-PEREZ, SOLEDAD. La ordenación del territorio: origen y significado. Terra Nueva Etapa, 2014 Vol. XXX, num. 47, p 13-32. Universidad Central de Venezuela. Caracas. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=72132516003.

- PALANCAR, M (s.f.). La Autoridad del Valle de Tennessee.

- BOISIER S. (1998). Postscriptum sobre desarrollo regional: modelos reales y modelos mentales. Revista Anales de Geografía. Vol. 18, p. 18-35.

- BENGOETXEA, J (2000). Principios jurídicos para la ordenación del territorio. Azkoaga, Vol. 08, p. 79-101.

- SERRANO, A. (2001). Hacia un desarrollo territorial más sostenible. ¿Una nueva forma de planificación? (p.2-11) Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. Asociación Interprofesional de Ordenación del Territorio, FUNDICOT, Valencia. http://www.cebem.org/biblioteca/fundicot/serrano.pdf.

- HILDENBRAND, A. (1997). Política de ordenación del territorio en Europa. Revista Estudios regionales num. 47 (1997), pp. 205-210. http://www.revistaestudiosregionales.com/pdfs/pdf977.pdf.

- PAREJO, T. (2003) La estrategia territorial europea. Tesis de doctorado. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. Tomos I y II. http://e-archivo.uc3m.es/dspace/handle/10016/562.

- https://rm.coe.int/6th-european-conference-of-ministers-responsible-for-regional-planning/168076dd93.

- https://enlargement.ec.europa.eu/strategy-paper-1999_en.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52005DC0218.

- https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/funding/erdf_en.

- https://www.bocm.es/boletin/CM_Orden_BOCM/2024/12/27/BOCM-20241227-1.PDF.

- https://wesr.unep.org/media/docs/assessments/unep_wwqa_report_web.pdf.

- http://www.pnuma.org/forodeministros/20-reunion-intersesional/documentos/UNEA2/PoW_draft_29_Sept_2015.pdf.

- https://maritime-spatial-planning.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/lsi_final20180417_digital5.pdf.

- Kidd, S. and Ellis, G. 2012. From the land to sea and back again? Using terrestrial planning to understand the process of marine spatial planning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 49-66. [CrossRef]

- https://paprac.org/.

- https://www.espon.eu/.

- https://www.mspglobal2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/MSPglobal_Flyer_LSI_EN.pdf.

- https://paprac.org/storage/app/media/Progress%20Reports/Progress%20Report%202018_2019.pdf.

- https://www.espon.eu/projects/msp-lsi-maritime-spatial-planning-maritime-spatial-planning-and-land-sea-interactions.

- Morf, A. (ed.), Cedergren, E., Gee, K., Kull, M. and Eliasen, S. 2019. Lessons, Stories and Ideas on How to Integrate Land-Sea Interactions into MSP. Stockholm, Nordregio.

- Kidd, S. et al. 2019. Taking account of land-sea interactions in marine spatial planning. In: J. Zaucha, J. and K. Gee, ed., Marine Spatial Planning: Past, Present, Future. Cham, Palgrave Macmillan.

- PATRICOVA cartographic viewer https://mediambient.gva.es/es/web/planificacion-territorial-e-infraestructura-verde/patricova-plan-de-accion-territorial-de-caracter-sectorial-sobre-prevencion-del-riesgo-de-inundacion-en-la-comunitat-valenciana.

- Chalastani, V. I., Tsoukala, V. K., Coccossis, H., & Duarte, C. M. (2021). A bibliometric assessment of progress in marine spatial planning. Marine Policy, 127, 104329. [CrossRef]

- Tsaimou, C. N., Papadimitriou, A., Chalastani, V. I., Sartampakos, P., Chondros, M., & Tsoukala, V. K. (2023). Impact of spatial segmentation on the assessment of coastal vulnerability—Insights and practical recommendations. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 11(9), 1675. [CrossRef]

- GÓMEZ PINA, GREGORIO (2015) ¿Qué es un tsunami?: importancia de la educación ciudadana. IERD El riesgo de maremotos en la Península Ibérica a la luz de la catástrofe del 1 de noviembre de 1755.

- GONZÁLEZ RODRÍGUEZ, MAURICIO (2015) Desarrollo de metodologías para el cálculo del riesgo por tsunami y aplicación para el caso de Cádiz. IERD El riesgo de maremotos en la Península Ibérica a la luz de la catástrofe del 1 de noviembre de 1755.

- PRIETO, J. M., ALMORZA, D., AMOR-ESTEBAN, V., MUÑOZ-PEREZ, J. J., & JIGENA-ANTELO, B. (2025). Identification of Risk Patterns by Type of Ship Through Correspondence Analysis of Port State Control: A Differentiated Approach to Inspection to Enhance Maritime Safety and Pollution Prevention. In Oceans (Vol. 6, No. 1, p. 15). MDPI.

- CRUZ-RAMÍREZ, CESIA J.; CHÁVEZ, VALERIA; SILVA, RODOLFO; MUÑOZ-PÉREZ, JUAN J.; RIVERA-ARRIAGA, EVELIA (2024) Coastal Management: A Review of Key Elements for Vulnerability Assessment. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. MDPI. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 386. https://www.mdpi.com/journal/jmse.

- Ley 13/2015, de 30 de marzo, de ordenación territorial y urbanística de la Región de Murcia. https://www.boe.es/eli/es-mc/l/2015/03/30/13/con.

- Plan General de Ordenación Urbana (PGOU) https://urbanismo.cartagena.es/urbanismo4/aspx/pln/plan.aspx?IDClave=2008-0001.

- Plan Estratégico de la Región de Murcia 2014-2020 https://transparencia.carm.es/-/plan-estrategico-de-la-region-de-murcia-2014-2020.

- Marco de Actuaciones Prioritarias para la Recuperación del Mar Menor https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/ministerio/planes-estrategias/mar-menor/marco-actuaciones-prioritarias-2024.html.

- POEM Levantine Balear Marine Spatial Plan (POEM) Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y Reto Demográfico. https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/costas/temas/proteccion-medio-marino/ordenacion-del-espacio-maritimo.

- Estrategia Regional de Mitigación y Adaptación al Cambio Climático de la Región de Murcia. https://transparencia.carm.es/-/estrategia-regional-de-mitigacion-y-adaptacion-al-cambio-climatico.

- Plan Hidrológico de la Cuenca del Río Segura 2022-2027 https://www.chsegura.es/es/cuenca/planificacion/planificacion-2022-2027/plan-hidrologico-2022-2027.

- Estrategia para el Cambio Climático de la Costa Española https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/costas/temas/proteccion-costa/estrategiaadaptacionccaprobada_tcm30-420088.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).