1. Introduction

Hallux rigidus (HR) is a degenerative change in the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint characterized by limited dorsiflexion of the hallux [

1]. Surgical treatment is considered when conservative management is ineffective. Cheilectomy is the standard procedure for early-stage HR, whereas arthrodesis is done in late-stage HR [

2,

3,

4]. In 1927, Cochrane observed that elastic resistance during hallux dorsiflexion persisted after cheilectomy, and this was attributed to the plantar soft tissues of the first MTP joint [

5]. To address this, the Cochrane procedure was developed, which involves a plantar longitudinal skin incision, retracting the flexor hallucis longus muscle, and releasing the flexor hallucis brevis (FHB) tendon, plantar capsule, and plantar portion of the lateral ligament. This procedure was able to achieve complete pain relief and patient satisfaction in 12 patients with HR, as well as alleviated the elastic resistance during hallux dorsiflexion. This novel procedure was able to identify and directly address the etiology of HR. However, no further case reports or series on the Cochrane procedure have been published since this initial report. With the advancement of arthroscopy, it is now possible to arthroscopically approach the soft tissues released in the Cochrane procedure through the first MTP joint [

6,

7].

This report describes a case of HR treated with arthroscopic FHB and plantar capsule release (Cochrane procedure).

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Case Presentation

In April 2015, a 73-year-old male with HR of the right foot sought consult after unsatisfactory conservative management of 1 year at a nearby clinic. He complained of a painful bony prominence, limited dorsiflexion, and pain during walking at the first MTP joint. The MTP joint was swollen, and a bony prominence at the dorsal joint was palpable. The passive dorsiflexion angle was 55°. The visual analog scale (VAS) score for pain during walking was 70, and the Japanese Society for Surgery of the Foot (JSSF) score [

8,

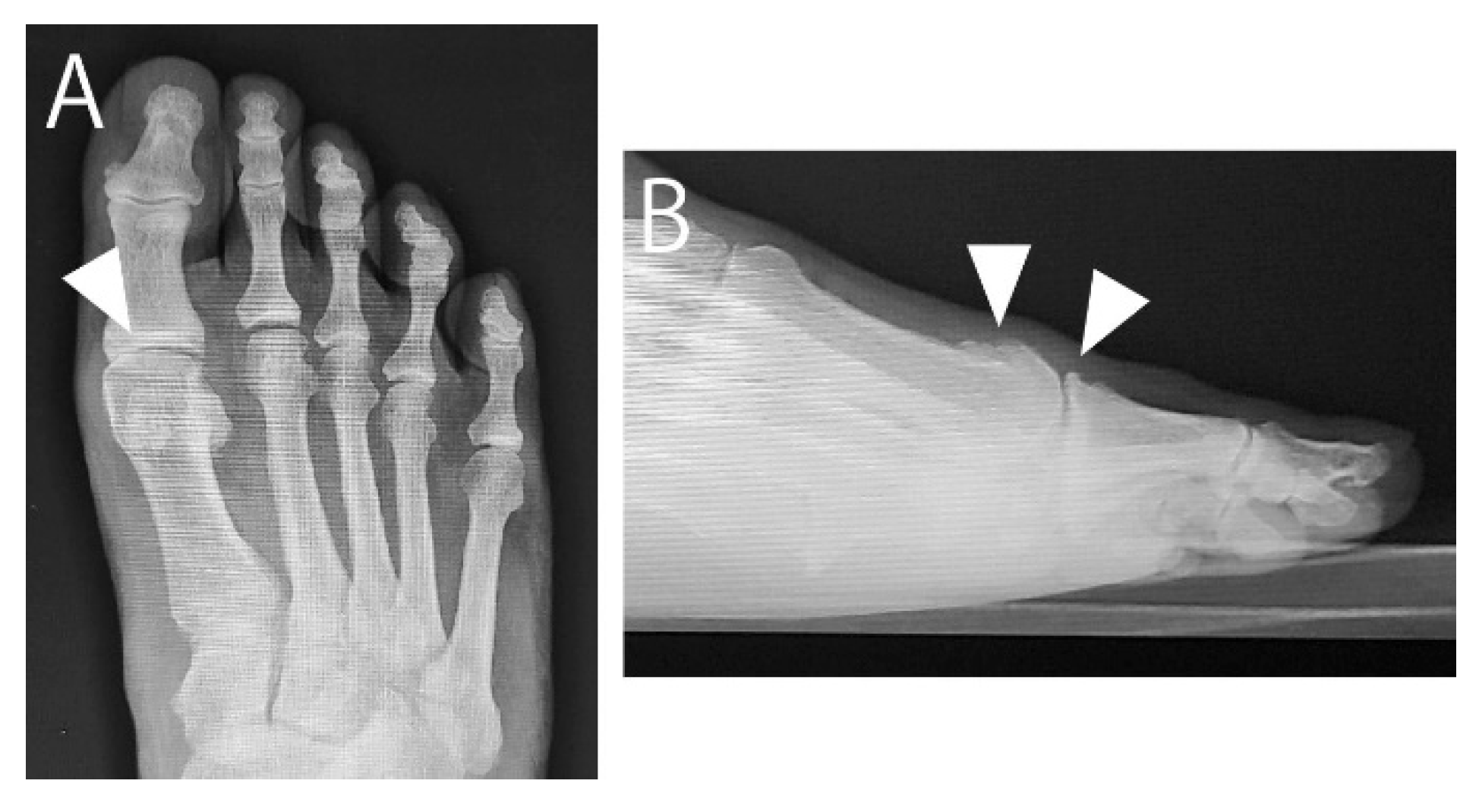

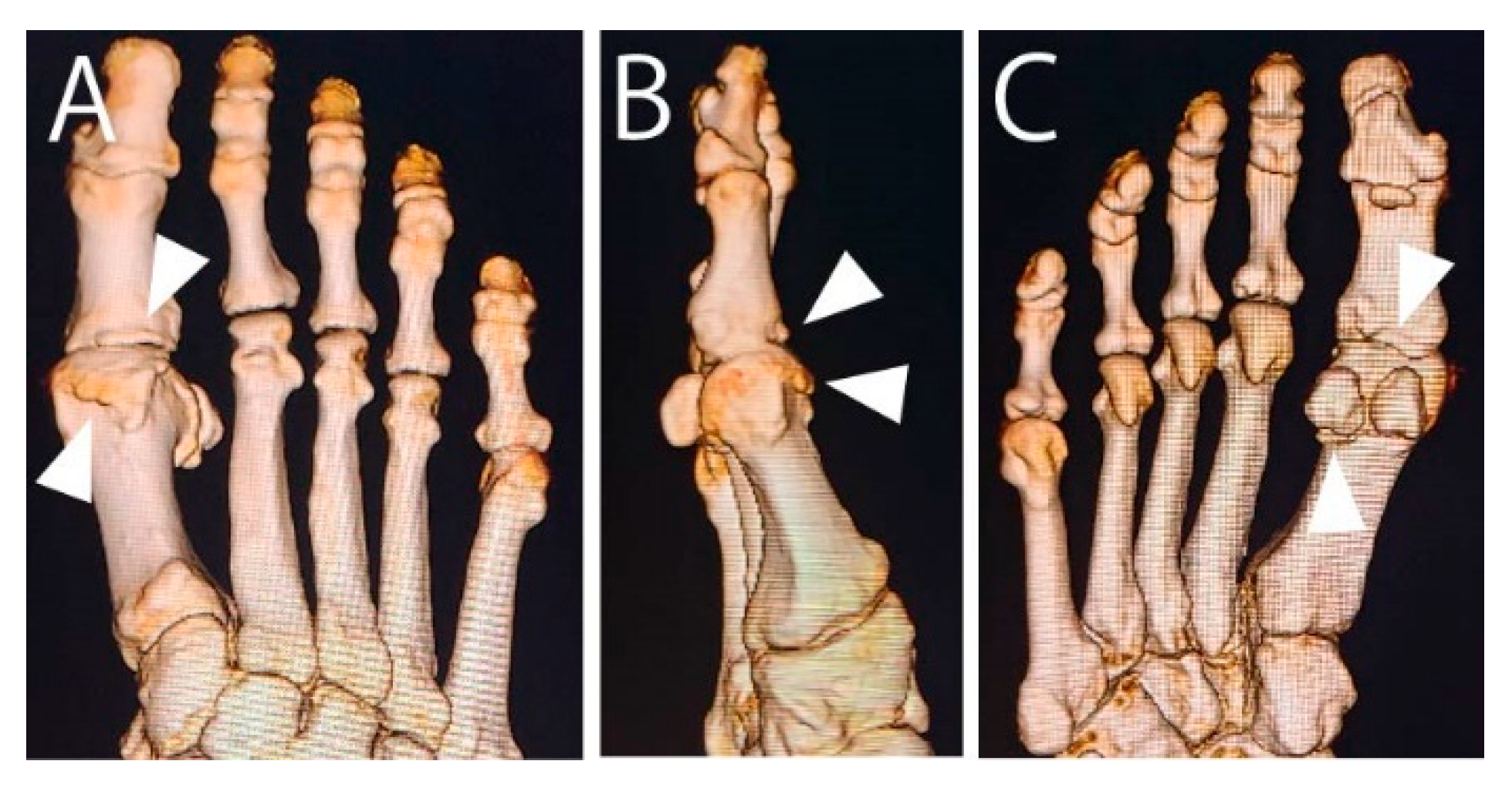

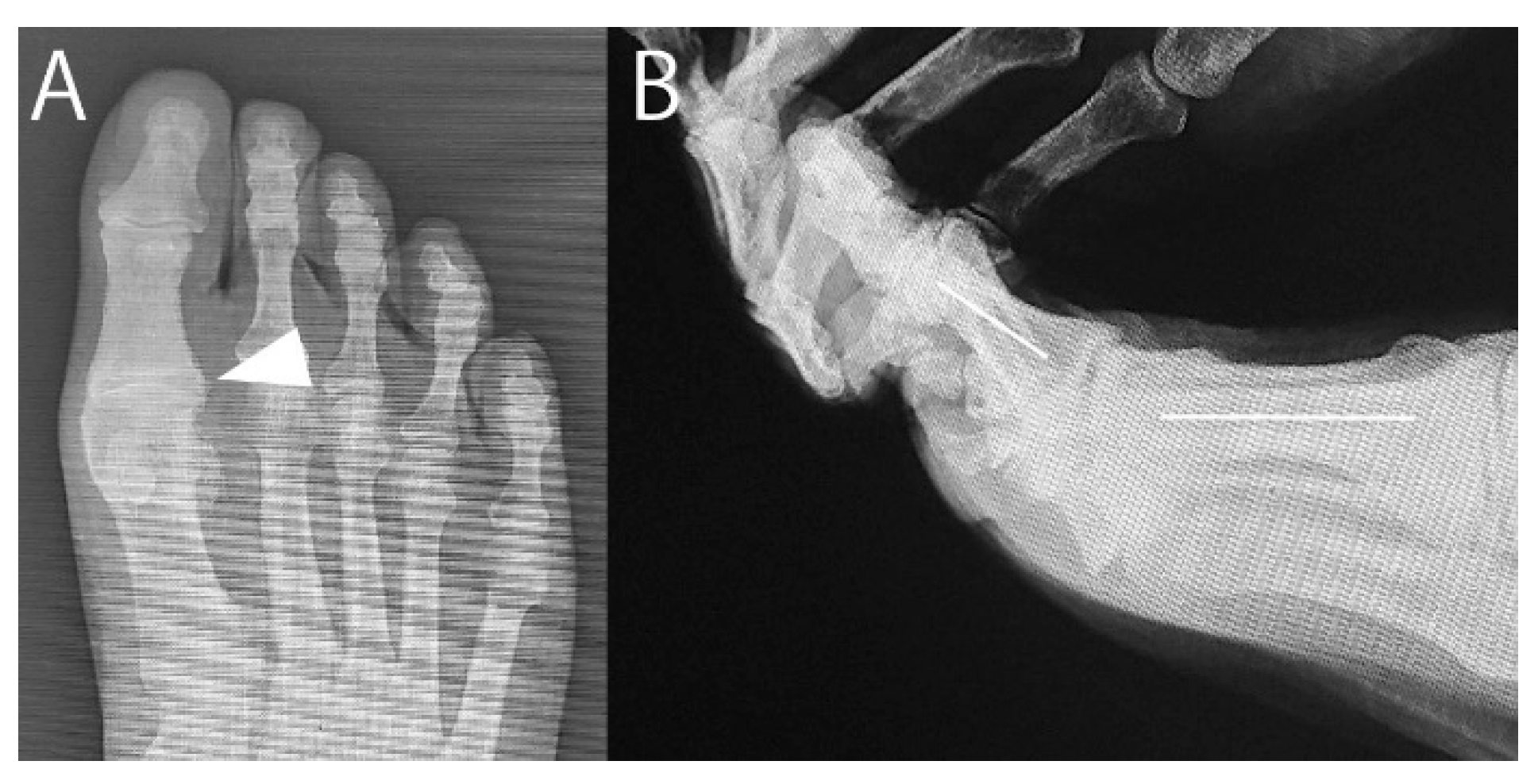

9] was 57. Radiographs showed a narrowed MTP joint space. Computed tomography revealed spur growth at the distal portion of the first metatarsal and the proximal portion of the proximal phalanx (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The patient opted for arthroscopic surgery; therefore, we proposed an arthroscopic cheilectomy and, if the improvement in dorsiflexion is insufficient, additional plantar soft tissue release can be performed.

2.2. Surgical Procedure

In July 2015, the patient underwent surgery. Dorsomedial, dorsolateral, proximal, and distal sesamoid portals were created [

10]. Traction was applied on the hallux using a soft wire penetrating the proximal phalanx. First, all spurs shown in

Figure 2 (except the spur at the plantar phalanx) were resected using a 3.0-mm hooded abrasion burr (Formula Compatible, Stryker) under fluoroscopic and arthroscopic guidance. However, hallux dorsiflexion did not improve enough after resecting the spurs in the MTP joint.

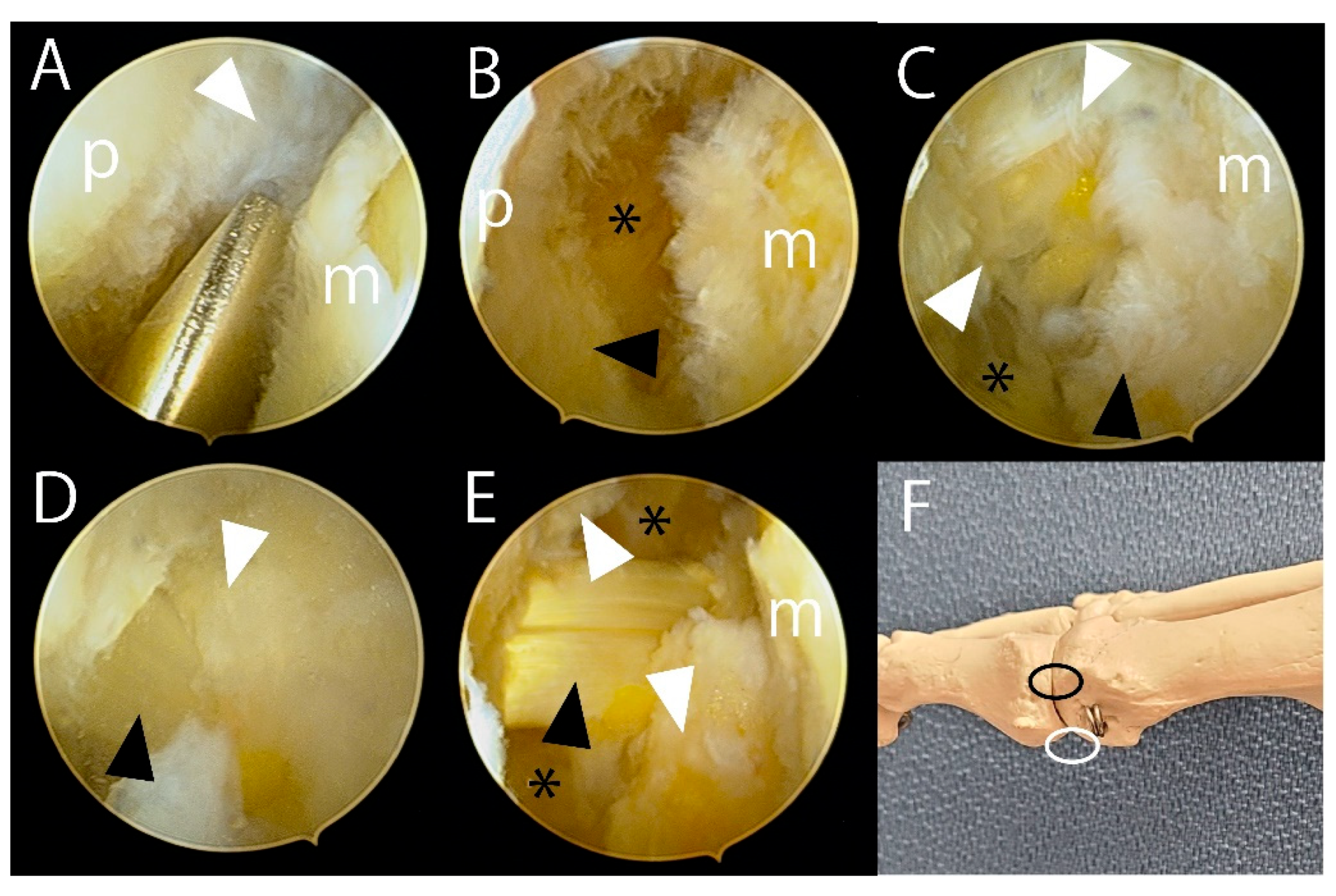

Then, a 2.3-mm 30° arthroscope was inserted through the dorsomedial portal, while a 2.5-mm arthroscopic cutter (Formula Aggressive Plus; Stryker) was introduced through the distal sesamoid portal. The synovium and the capsule at the medial plantar site of the MTP joint were resected using the cutter until the medial FHB tendon became visible (

Figure 3A). Subsequently, the medial FHB was released with a small hook-shaped knife (ECTRA Disposable Knife; Smith & Nephew), exposing the plantar fat pad (

Figure 3B). During FHB release, care was taken to avoid cutting the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon by verifying the width of the medial sesamoid under the fluoroscopic anteroposterior view of the foot.

After releasing the FHB, the FHL tendon sheath wrapped in fat tissue became visible behind the residual void space (

Figure 3C). The sheath was debrided to reveal the FHL tendon (

Figure 3D). Once the FHL tendon was identified, the lateral plantar synovium and capsule were excised to expose the lateral FHB tendon. This tendon and plantar portion of the lateral ligament were then released using the small knife. The completeness of the plantar soft tissue release, which had restricted dorsiflexion, was confirmed arthroscopically as the hallux was dorsiflexed. The FHL tendon did not impede dorsiflexion (

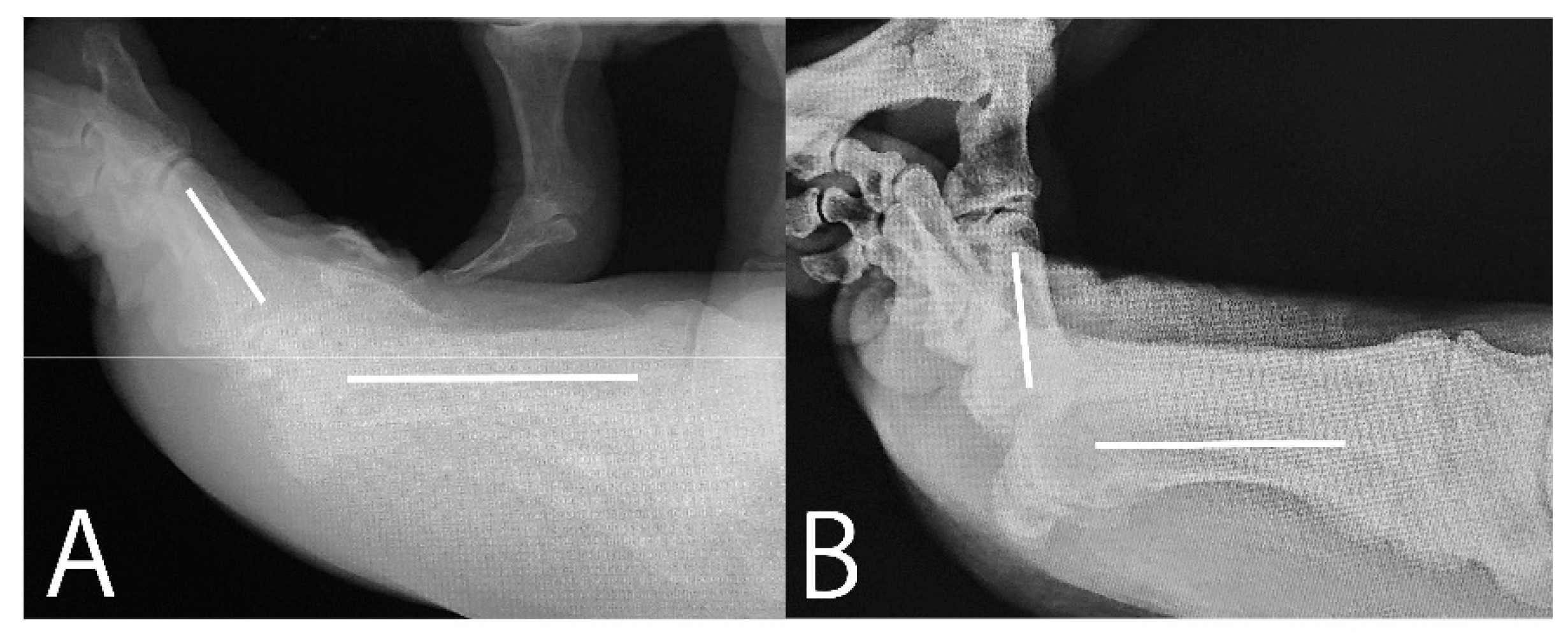

Figure 3E and 3F). The dorsiflexion improved from 55° to 85° (

Figure 4).

2.3. Postoperative Process

The patient followed up several times after surgery. However, at six months postoperatively, the patient opted to discontinue follow-up consultations since he had already achieved pain relief.

At 9 years postoperatively, contact was reestablished with the patient, who was still alive at 83 years old. He was able to follow-up at an orthopedist at nearby clinic, whose evaluation yielded VAS and JSSF scores were 0 and 88, respectively. The passive dorsiflexion angle on the lateral radiograph was 35° (

Figure 5). Photographs of the right foot showed no postoperative cockup deformity of the hallux after cutting the FHB (

Figure 6).

3. Discussion

This case report presented a patient with HR who underwent arthroscopic FHB tendon and plantar capsule release (Cochrane procedure). Improvements were seen in both VAS (70–0) and JSSF (57–88) scores from preoperatively to 9 years and 6 months postoperatively. No postoperative hallux deformity was observed.

During surgery, the dorsiflexion of the first MTP joint improved from 55° to 85° immediately after cutting the FHB tendon and plantar capsule, suggesting that the contraction of these tissues was the main cause of limited dorsiflexion in HR. Notably, the patient experienced no pain even at 9 years and 6 months postoperatively, likely because the primary cause of HR was addressed during surgery. Additionally, cutting the tendon did not cause a cockup deformity of the hallux, which is a major concern in this procedure [

11]. Thus, the arthroscopic Cochrane procedure appears to demonstrate safe and effective long-term outcomes.

Cochrane identified plantar soft tissue contracture as the main cause of HR and developed a procedure that directly addresses this etiology [

5]. However, most of the current surgeries for HR do not address its underlying cause. For instance, cheilectomy does not address the cause of HR and involves removing the dorsal third of the articular surface and the dorsal spur despite being a procedure for the early stages of HR [

2,

3,

7]. Cochrane considers this illogical, with other surgeons even regarding it as destructive. Arthrodesis and arthroplasty also do not address the cause of HR and are similarly considered destructive [

12,

13]. Meanwhile, although metatarsal decompression osteotomy does not directly address the plantar soft tissue, it alleviates FHB tension by shifting the metatarsal head plantarward and proximally [

7]. In turn, this reduces the stress on the dorsal surface of the metatarsal head and improving dorsiflexion [

14]. However, metatarsal head dorsiflexion osteotomy reduces stress on the dorsal surface of the metatarsal head [

15], but it does not reduce FHB tension because the sesamoid is not shift proximally with the osteotomy [

7]. Notably, one disadvantage of the Cochrane procedure is its use of a plantar skin incision [

5], which can cause wound problems. However, in this paper, we demonstrate that the Cochrane procedure can be performed arthroscopically. Therefore, the arthroscopic Cochrane procedure is a promising minimally invasive surgery that directly addresses and treats the etiology of HR.

The arthroscopic Cochrane procedure is a technically demanding yet safe procedure when performed correctly. The initial step involves the fluoroscopic resection of spurs. As the spurs occupy the joint space, the capsule is tight, and the joint space is narrow. Removing the spurs slightly widens the joint space, facilitating subsequent arthroscopy. However, fluoroscopic removal of spurs at the plantar phalanx and distal sesamoid is not recommended, as it may damage the FHL tendon. In the secondary step, arthroscopy of the plantar aspect of the first MTP joint in HR is challenging because of the abundance of synovium and the continuity of the structures, including the FHB sheath, the capsule, the periosteum of the distal sesamoid spur, and the cartilage of the sesamoid—all of which appear uniformly white. Therefore, we consider verifying the position of the sesamoid under fluoroscopic guidance and resecting the plantar soft tissue using a small arthroscopy cutter to be the most reliable approach. Releasing the medial FHB tendon further widens the joint space, making it easier to identify the FHL tendon sheath. The small cutter remains a safe tool for subsequently identifying the FHL tendon. Once the FHL tendon is identified and secured, releasing the lateral FHB tendon becomes straightforward. Lastly, the plantar soft tissues are arthroscopically examined to ensure they do not restrict hallux dorsiflexion. If the plantar portion of the lateral ligament is not completely released, dorsiflexion may remain limited.

This case report has several limitations. First, since this procedure was only done in one case, its applicability in various stages of HR needs further evaluation. Second, there was a 9-year gap between the last two consultations, making the influence of degenerative changes on the decrease in the hallux dorsiflexion unclear. Finally, the condition of the released FHB could not be evaluated since the final consultation was conducted by a different orthopedist.

4. Conclusions

This case demonstrates that the arthroscopic Cochrane procedure can achieve favorable long-term outcomes without postoperative cockup deformity, even at 9 years and 6 months postoperatively.

Author Contributions

Kenichiro Nakajima is the only author and performed everything regarding this research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This case report was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital (Approval ID: YIHCE2024-2).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for the use of medical records was obtained from the patient.

Data Availability Statement

The data for the present case is available from the author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HR |

Hallux rigidus |

| MTP |

Metatarsophalangeal |

| FHB |

Flexor hallucis brevis |

| FHL |

Flexor hallucis longus |

| VAS |

Visual analog scale |

| JSSF |

Japanese Society for Surgery of the Foot |

References

- Nakajima, K. Sliding oblique metatarsal osteotomy fixated with K-wires without cheilectomy for all grades of hallux rigidus: A case series of 76 patients. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2022, 7, 24730114221144048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlin, M.J.; Shurnas, P.S. Hallux rigidus. Grading and long-term results of operative treatment. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2003, 85, 2072–2088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Murphy, G.A. Treatment of hallux rigidus with cheilectomy using a dorsolateral approach. Foot Ankle Int. 2009, 30, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perler, A.D.; Nwosu, V.; Christie, D.; Higgins, K. End-stage osteoarthritis of the great toe/hallux rigidus: A review of the alternatives to arthrodesis: Implant versus osteotomies and arthroplasty techniques. Clin. Podiatr. Med. Surg. 2013, 30, 351–395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cochrane, W.A. An operation for hallux rigidus. Br. Med. J. 1927, 1, 1095–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, T.H.; Slocum, A.M.Y.; Li, C.C.H.; Kumamoto, W. Arthroscopic dorsal cheilectomy, plantar capsular release, flexor hallucis brevis release, and sesamoid cheilectomy for management of early stages of hallux rigidus. Arthrosc. Tech. 2025, 14, 103198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, K. Joint-preserving surgeries for hallux rigidus based on etiology: A review and commentary. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niki, H.; Aoki, H.; Inokuchi, S.; Ozeki, S.; Kinoshita, M.; Kura, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Noguchi, M.; Nomura, S.; Hatori, M.; Tatsunami, S. Development and reliability of a standard rating system for outcome measurement of foot and ankle disorders II: Interclinician and intraclinician reliability and validity of the newly established standard rating scales and Japanese Orthopaedic association rating scale. J. Orthop. Sci. 2005, 10, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niki, H.; Aoki, H.; Inokuchi, S.; Ozeki, S.; Kinoshita, M.; Kura, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Noguchi, M.; Nomura, S.; Hatori, M.; Tatsunami, S. Development and reliability of a standard rating system for outcome measurement of foot and ankle disorders I: Development of standard rating system. J. Orthop. Sci. 2005, 10, 457–465.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, K. Arthroscopy of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2018, 57, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haskell, A.; Mann, R.A. Biomechanics of the foot and ankle. In Mann’s Surgery of the Foot and Ankle, 9th ed.; Coughlin, M.J., Saltzman, C.L., Anderson, R.B., Eds.; Elsevier Saunders, 2014; pp. 56–163.

- Migues, A.; Slullitel, G. Joint-preserving procedure for moderate hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Clin. 2012, 17, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, K. Sliding oblique metatarsal osteotomy fixated with a k-wire without cheilectomy for hallux rigidus. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022, 61, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Derner, R.; Goss, K.; Postowski, H.N.; Parsley, N. A plantar-flexor-shortening osteotomy for hallux rigidus: A retrospective analysis. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2005, 44, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cho, B.-K.; Park, K.-J.; Park, J.-K.; SooHoo, N.F. Outcomes of the distal metatarsal dorsiflexion osteotomy for advanced hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2017, 38, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).