What is already known

Intake of dairy products is globally widespread but it is controversial as to whether this is beneficial. For example, dairy intake has been reported to be both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory in different studies; this includes in relation to the autoimmune disease rheumatoid arthritis (RhA).

What this study adds

We have used genetic data to perform a causal analysis of the links between lactose intolerance, RhA and body mass index (BMI). Congenital lactose intolerance increases the risk of RhA but adult-onset lactose intolerance reduces the risk of RhA. The protective effect of adult-onset lactose intolerance on RhA is conditional on reduced BMI.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

Our findings have translational implications and offer a mechanistic understanding of apparently contradictory findings in the literature. We conclude that dairy intake is likely to be anti-inflammatory, which explains why congenital lactose intolerance increases the risk of RhA. Moreover dairy intake is unlikely to cause harmful inflammation in the context of normal BMI.

1. Introduction

Dairy intake is an important source of calories globally, but it has been reported to be both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory in different studies. As non-dairy substitutes become increasingly available, determining whether or not dairy products carry specific benefits or harms has significant translational implications.

Lactose intolerance necessarily results in reduced intake of dairy products. To be absorbed from the intestine, lactose, which is present within dairy products, must be hydrolysed by the enzyme lactase. Lactose intolerance consists of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms after consuming lactose-containing foods and beverages [

1] caused by incomplete lactose digestion due to deficiency of functional lactase. Lactose intolerance can be congenital as a result of homozygous or complex heterozygous mutations within lactase [

2]. However, even without genetic loss-of-function, levels of lactase reduce through life in a majority of individuals [

3] and thus the majority of lactose intolerance actually presents in adulthood. Indeed globally, ~68% of the population is lactose intolerance to some degree, with varying prevalence across regions [

4]. In order to determine the effect of impact of dairy products, we have used genetic liability to lactose intolerance as a natural experiment leading to reduced dairy intake.

The role of dairy intake and systemic inflammation is debated. A recent meta-analysis concluded that dairy products are likely to be anti-inflammatory except in relatively rare cases of milk allergy [

5]. Consistent with this, dairy products contain a number of anti-inflammatory lipids [

6]. In contrast, lactose-intolerant individuals tend to have higher levels of bifidobacteria and other bacteria within their gut microbiome [

7] that produce anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acids from undigested lactose [

8]. Rheumatoid arthritis (RhA) is an autoimmune disease driven by inappropriate inflammation. It has been suggested that dairy products can trigger autoimmune diseases including RhA [

9]. However, other evidence points to a negative association between consumption of dairy products and risk of RhA [

10]. In our study of intake of dairy products we have taken genetic liability to RhA as a proxy for harmful inflammation resulting from dietary changes.

A third factor to consider is that both lactose intolerance and RhA have been linked to elevated body mass index (BMI). Elevated BMI is pro-inflammatory and is associated with autoimmune diseases including RhA [

11]; similarly low BMI has been observed to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines [

12]. Mendelian randomisation (MR) evidence has associated adult-onset lactose intolerance with reduced BMI [

13,

14] and atypical lactase persistence has been associated with increased BMI [

13]. If adult-onset lactose intolerance leads to a reduction in BMI this may reduce the risk of RhA, even if consumption of dairy products is anti-inflammatory. Here we have controlled for BMI as a potential confounder of the relationship between dairy intake and harmful inflammation.

We have used genetics to perform a causal analysis of the links between dairy intake, RhA and BMI. Our approach is summarised in

Figure 1. Genetic measures are by-definition upstream of an environmental exposure such as intake of dairy products or BMI. MR is a method used to assess whether an exposure, like lactose intolerance, significantly affects an outcome, such as RhA. MR uses genetic variants as natural experimental instruments, assigning participants into groups at conception based on their genetic liability to a particular exposure. These groups are compared to determine if the exposure has a causal effect on disease outcomes [

15]. The methodology relies on using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables to estimate causal effects. For MR to establish causation, three assumptions must be met: the genetic instruments should affect the exposure, not be related to confounders, and must influence the outcome only through the exposure. In our rare variant analysis, we have identified individuals likely to suffer congenital lactose intolerance because of homozygous or complex heterozygous mutations within the

LCT gene, which encodes lactase.

By comparing congenital lactose intolerance with adult-onset lactose intolerance and genetic liability to both RhA and BMI we can dissect the various contributing causes. We conclude that dairy products are anti-inflammatory and, although adult-onset lactose intolerance is protective against RhA, this is mediated by reduced BMI. Our data suggest that dairy intake, in the context of a normal BMI, may offer protection against RhA. Our findings have significant translational implications and offer a mechanistic understanding of apparently contradictory findings in the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Exposure and Outcome Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

GWAS used to measure genetic liability to adult-onset lactose intolerance was obtained from the FinnGen Biobank and included 453,733 Finnish biobank donors of whom 445 reported lactose intolerance with a mean age of onset of 38.3 years.

GWAS used to measure genetic determinants of BMI was a meta-analysis of 125 studies performed by the GIANT consortium [

16] which included 339,224 participants, of whom 322,154 individuals were of European descent.

GWAS used to measure genetic liability to osteoporosis was performed in UK Biobank participants and included 484,598 participants of European ancestry of whom 7,751 were diagnosed with osteoporosis [

17].

GWAS used to measure RhA was a meta-analysis of UK Biobank, FinnGen and Biobank Japan cohorts including 628,000 participants [

18]. Specific to RhA the study included 8,255 European ancestry cases and 409,001 European ancestry controls; and 5,348 East Asian ancestry cases and 173,268 East Asian ancestry controls.

2.2. Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization

For all MR tests we report the multiplicative random effects inverse variance weighted (IVW) [

19] estimate of causal inference because this carries the most statistical power and is more robust to heterogeneity than a fixed effects IVW [

15]. Genetic instruments were selected with a conservative

p -value cut-off (

p < 5E- 8) except for lactose intolerance where we used a positive control, the causal link between lactose intolerance and osteoporosis, to guide selection of instruments. Identified SNPs within a 10kb window were clumped for independence using a stringent cut-off of R

2≤0.001 within a European reference panel; where SNPs were in linkage disequilibrium (LD) those with the lowest

p -value were retained. Where an exposure SNP was unavailable in the outcome dataset, a proxy with a high degree of LD (R

2 ≥0.9) was identified within a European reference population. The effects of SNPs on outcomes and exposures were harmonised in order to ensure that the beta values were signed with respect to the same alleles.

For palindromic alleles, those with minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.42 were omitted from the analysis in order to reduce the risk of errors due to strand issues.

In order to increase confidence in the IVW results, we performed a series of robust MR measures and sensitivity analyses. We used an F-statistic to measure the strength of the association between instrumental SNPs and the exposure of interest. An F-statistic > 10 indicates that an SNP-derived estimate has a bias of < 10% of its intragroup variability and signifies an acceptable instrument. Pleiotropy occurs between SNPs where the difference in effect size for the exposure is not proportional to the difference in effect size for the outcome, and is usually due to a violation of one of the key assumptions underlying MR, the assumption that instrumental SNPs should be associated with the outcome only through the exposure [

15]. To account for pleiotropy, we removed SNPs where the p-value for the association with the outcome was lower than for the association with the exposure of interest. As IVW estimates are vulnerable to pleiotropic SNPs, we used Cochran’s Q test (p > 0.05) as a sensitivity measure to detect heterogeneity indicating pleiotropy. Moreover, radial-MR [

20] was used to remove statistically significant outlier SNPs. The

I2 statistic was used to measure the heterogeneity between variant-specific causal estimates, with a low

I2 indicating bias toward the null hypothesis [

21]. A leave-one-out (LOO) analysis was applied to identify results where one or more SNPs exert a disproportionate effect. TwoSampleMR (version 0.5.6), Mendelian Randomization (version 0.5.1) and RadialMR (version 1.0) R packages were used for all MR analyses.

2.3. Multivariable MR (MVMR)

MVMR [

22,

23] was used to test whether the effect of adult-onset lactose intolerance on RhA was conditional on changes in BMI. GWAS summary statistics were obtained as for two-sample MR analyses. The p-value cut-offs used to choose instrumental SNPs for each exposure were chosen so as to achieve adequate instrument strength for both exposures (conditional F-statistic >10 for each exposure [

24]). Reported results showed no evidence of instrument heterogeneity (Cochran’s Q-test p>0.05). Exposures were derived from independent cohorts and therefore a correction for the covariance between the effect of the genetic variants on each exposure was not necessary. MVMR was implemented using the MVMR (version 0.3)[

23] and Mendelian Randomization (version 0.5.1) [

22] R packages.

2.4. Rare Genetic Variant Burden Testing

To perform rare genetic variant burden testing to determine the effect of congenital lactose intolerance on risk of RhA we used whole-exome sequencing data from UK Biobank (Wang et al., 2021). We considered variants were high-quality variant-calls based on coverage, mapping quality, genotype quality, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. We were aiming to identify individuals with a complete LOF in

LCT and therefore we considered non-synonymous variants which were rare (MAF<0.0005 in both UK Biobank and GnomAD [

25]) and either homozygous or complex heterozygous (i.e. there were two qualifying but different variants within the same individual). Identified rare variants with a common biological effect were collapsed into a single Fisher's exact two-sided test to determine whether the burden of variants is different in RhA cases and controls.

3. Results

3.1. Congenital Lactose Intolerance Increases the Risk of Inflammatory Arthritis

Congenital lactose intolerance is caused by loss-of-function (LOF) mutations within

LCT, which encodes the lactase enzyme [

2]. The mutations occur in a homozygote or compound heterozygote pattern, and compromise both missense and nonsense mutations. We applied this model in UK Biobank participants to test whether congenital lactose intolerance is causally linked to risk of RhA (

Methods); whole exome sequencing data was available from >100,000 participants (

Table 1). RhA in children is considered within the diagnosis of juvenile arthritis and therefore we considered association between congenital lactose intolerance and both juvenile arthritis and RhA. Congenital lactose intolerance is causally associated with juvenile arthritis (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.03, OR=34.8,

Table 1) and, at borderline statistical significance, with adult-onset seropositive RhA (p = 0.07, OR = 2.4,

Table 1).

3.2. Positive Control Analysis to Guide Genetic Instrument Selection for Measurement of Adult-Onset Lactose Intolerance in MR

Lactose intolerance is causally related to osteoporosis [

26,

27] and is associated with a biologically plausible mechanism due to the reduced calcium intake. We took advantage of this fact to derive an appropriate set of genetic instruments for inferring lactose intolerance in our subsequent MR study of RhA.

The p-value cut-off for choice of genetic instruments (SNPs) in MR is a compromise: When the cut-off is too low, informative instruments will be lost, but when it is too high, non-informative instruments will be introduced and instrument pleiotropy is more likely to occur [

28]. We tested multiple p-value cut offs between 5e-8 and 5e-4 in order to identify the most appropriate (

Supplementary Table S1). Only one SNP met a genomewide threshold (p<5e-8) for association with lactose intolerance, which does not enable important quality controls including robust MR tests and sensitivity analyses (

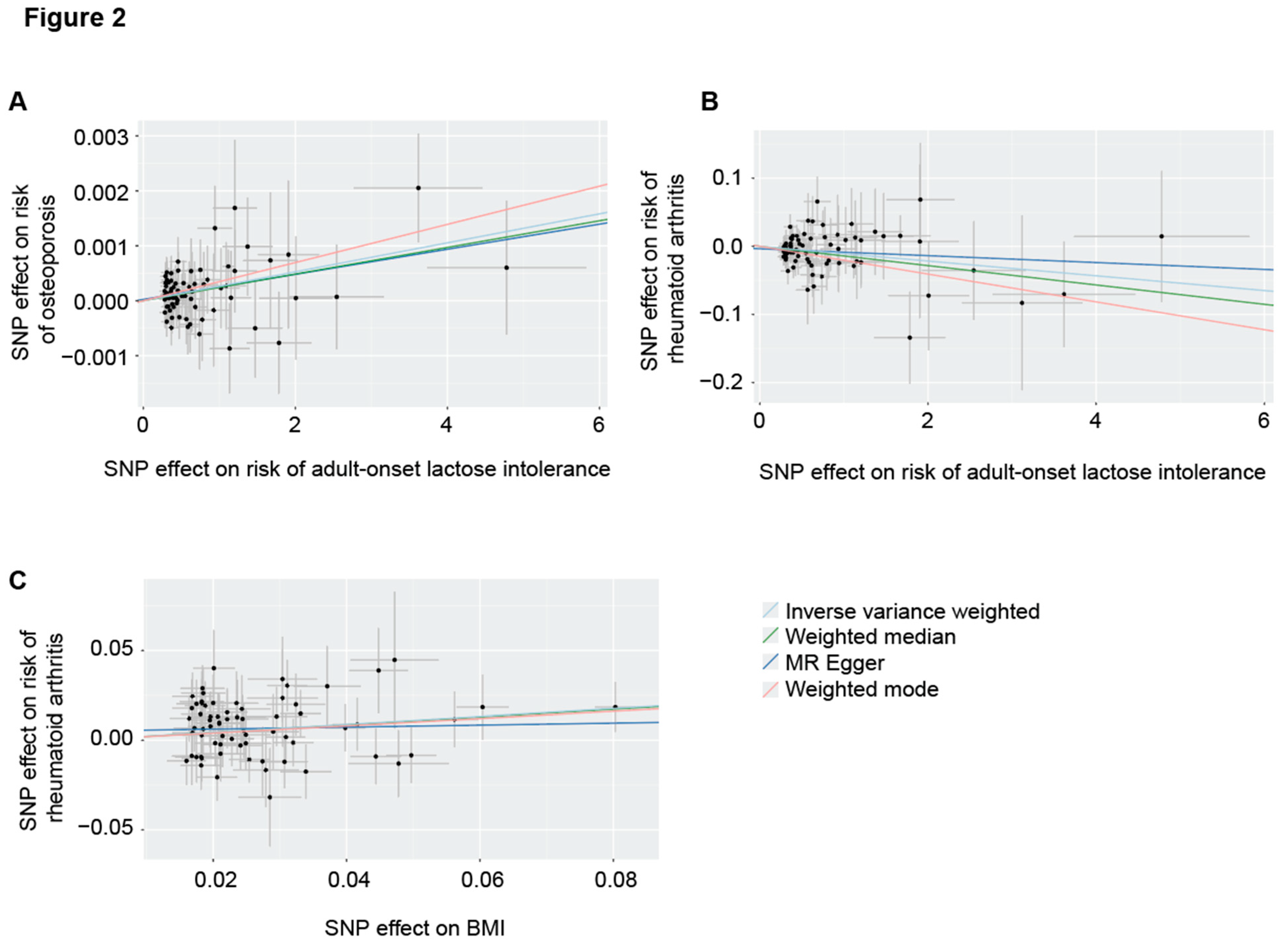

Methods). A p-value cut off of 5e-5 produced the most significant result (IVW, p= 9.4e-4, beta = 2.6e-4, se = 8.0e-5,

Table 2, Figure 2A).

3.3. Adult-Onset Lactose Intolerance Is Protective Against the Development of RhA

Our positive control analysis of the causal relationship between adult-onset lactose intolerance and osteoporosis enabled optimum instrument selection for a MR test to determine whether adult-onset lactose intolerance is causally linked to the development of RhA. Genetic liability to adult-onset lactose intolerance is causally linked to risk of RhA (IVW, p = 0.01, beta = -0.01, se = 0.004,

Table 2, Figure 2B). This result was also statistically significant in robust MR tests and, based on the sensitivity tests performed, none of these tests was invalidated by instrument pleiotropy or weak instruments (

Methods, Table 2).

3.4. Protective Effect of Adult-Onset Lactose Intolerance Against the Development of RhA Is Conditional on Elevated BMI

BMI is pro-inflammatory and is associated with autoimmune diseases including RhA [

11]. Given that reduced BMI is associated with adult-onset lactose intolerance [

13,

14] we hypothesised that the protective effect of adult-onset lactose intolerance on development of RhA might be mediated via reduced BMI.

First, we sort to confirm the causal relationship between elevated BMI and risk of RhA. Using a p-value cut-off of 5e-8 to select instruments, genetic liability to higher BMI has a significant causal effect on the risk of RhA (IVW, p = 5.9e-7, beta = 0.24, se = 0.05,

Table 2, Figure 2C). This result was also statistically significant in robust MR tests and, based on the sensitivity tests performed, none of these tests was invalidated by instrument pleiotropy or weak instruments (

Methods, Table 2).

The protective effect of adult-onset lactose intolerance was non-significant when conditioned on BMI (adult-onset lactose intolerance p=0.36, beta=-0.002, se=0.003 and BMI p=0.04, beta=0.14, se=0.07). The MVMR analysis achieved adequate instrument strength for both exposures and there was no evidence of instrument heterogeneity (Methods).

4. Discussion

Dairy products form a significant portion of the human diet almost universally. Therefore, it is important that the health benefits or harms of consumption of dairy products are well understood. Unfortunately, there has been significant controversy in the literature leading to conflicting advice with respect to the role of dairy intake in terms of systemic inflammatory response. Here, we have used traits linked to dairy consumption – lactose intolerance and BMI – to dissect the role of dairy consumption on harmful inflammation as exemplified by RhA. We have confined our analysis to genetic measures which are fixed at conception, and therefore our results are less vulnerable to selection bias or reverse causation than a conventional observational study. Moreover, this approach enables us to take advantage of several large datasets including UK Biobank, FinnGen Biobank and Biobank of Japan.

We have demonstrated that congenital and adult-onset lactose intolerance have opposite effects on the risk of RhA. Congenital lactose intolerance is causally linked to risk of RhA which is consistent with the idea that dairy consumption is anti-inflammatory. This is supported by a recent meta-analysis [

5], and with the observation that dairy products contain a number of anti-inflammatory lipids [

6]. Conversely, adult-onset lactose intolerance has a protective effect and reduces the risk of RhA. We have provided evidence to explain this apparently contradictory observation, by demonstrating that the protective effect of adult-onset lactose intolerance is conditional on reduced BMI. Indeed, after controlling for BMI, the protective effect of lactose intolerance becomes non-significant. Similarly, there is evidence from observational studies of a significant

inverse relationship between dairy intake and BMI after controlling for physical exercise and total dietary energy intake [

29]. This suggests that dairy product intake in moderation does not inevitably lead to harmful increase in BMI and should, in light of our data, be encouraged for its positive effect on autoimmune diseases.

We did not control for BMI in our analysis of congenital lactose intolerance because of the technical challenge of combining common and rare variant analyses. However, dairy intake in babies and children has been specifically associated with higher BMI [

30] suggesting that congenital lactose intolerance may be protective against obesity, and making the positive association we observe with RhA more striking.

An alternative explanation for the difference between our observations regarding congenital and adult-onset lactose intolerance is that dairy products have a different effect in development (e.g. [

31]) compared to in adulthood. Congenital lactose intolerance may therefore increase the risk of RhA via a mechanism which is not affected by adult-onset lactose intolerance where onset occurs after development has completed. It was not possible to discount this possibility in our analysis, however we can say that we do not find any evidence for a

pro-inflammatory effect of dairy products given that BMI completely explains the protective effect of adult-onset lactose intolerance.

A limitation of our study is that here is sample overlap between the GWAS used to measure lactose intolerance and the GWAS used to measure liability to RhA; the lactose intolerance GWAS was performed in FinnGen which forms a subset of the GWAS used for RhA; if weak instruments are present this can produce a biassed result [

32]. We have countered this by performing a positive control analysis to guide instrument selection for the measurement of lactose intolerance, and we showed that as measured by the F-statistic, we achieved adequate instrument strength.

In summary, in this study we have presented evidence that low levels of dairy product consumption can increase risk of RhA. Our findings may extend to other diseases underpinned by systemic inflammatory processes, and consequently this study supports the public health recommendations that dairy should form part of a healthy, balanced health diet

Author Contributions

AG: OFR and JCK conceived and designed the study. AG, OFR, EA, AK, TJ and JCK performed data analyses and methodology. AG, OFR, EA, AK, TJ and JCK interpreted the data. JCK supervised the work. AG and JCK wrote the manuscript with feedback from all other authors.

Funding

TJ is funded by a Medical Research Council (MRC) Clinical Research Training Fellowship [MR/Z504105/1]. JCK acknowledges funding from Target ALS, the ALS Association and the MND Association (MNDA).

Research Ethics Approval

Datasets utilised in our analysis are cited including reference to ethical approval, but no new Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval or informed consent was required for this article.

Data Availability

All data are available from the cited manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all individuals who donated biosamples and data used in this study. We also acknowledge the genotyping data provided through the AstraZeneca PheWAS Portal.

Competing Interest

AK has performed consultancy for HRA pharma.

References

- Di Costanzo M, Berni Canani R. Lactose Intolerance: Common Misunderstandings. Ann Nutr Metab. 2018;73 Suppl 4:30–7.

- Wanes D, Husein DM, Naim HY. Congenital Lactase Deficiency: Mutations, Functional and Biochemical Implications, and Future Perspectives. Nutrients. 2019;11. [CrossRef]

- Lee MF, Krasinski SD. Human adult-onset lactase decline: an update. Nutr Rev. 1998;56:1–8.

- Bayless TM, Brown E, Paige DM. Lactase Non-persistence and Lactose Intolerance. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19:23.

- Bordoni A, Danesi F, Dardevet D, et al. Dairy products and inflammation: A review of the clinical evidence. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:2497–525.

- Lordan R, Zabetakis I. Invited review: The anti-inflammatory properties of dairy lipids. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:4197–212.

- Brandao Gois MF, Sinha T, Spreckels JE, et al. Role of the gut microbiome in mediating lactose intolerance symptoms. Gut. 2022;71:215–7.

- Yoon SJ, Yu JS, Min BH, et al. Bifidobacterium-derived short-chain fatty acids and indole compounds attenuate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by modulating gut-liver axis. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1129904.

- Borba V, Lerner A, Matthias T, et al. Bovine milk proteins as a trigger for autoimmune diseases: Myth or reality? International Journal of Celiac Disease. 2020;8:10–21.

- Chen W, Jiang D, Liu K, et al. The association of milk products with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study from NHANES. Joint Bone Spine. 2024;91:105646.

- Li X, Zhu J, Zhao W, et al. The Causal Effect of Obesity on the Risk of 15 Autoimmune Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Obes Facts. 2023;16:598–605.

- Kumar NP, Nancy AP, Moideen K, et al. Low body mass index is associated with diminished plasma cytokines and chemokines in both active and latent tuberculosis. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1194682.

- Mendelian Randomization of Dairy Consumption Working Group. Dairy Consumption and Body Mass Index Among Adults: Mendelian Randomization Analysis of 184802 Individuals from 25 Studies. Clin Chem. 2018;64:183–91.

- Yang Q, Lin SL, Au Yeung SL, et al. Genetically predicted milk consumption and bone health, ischemic heart disease and type 2 diabetes: a Mendelian randomization study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:1008–12.

- Julian TH, Boddy S, Islam M, et al. A review of Mendelian randomization in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2022;145:832–42.

- Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518:197–206.

- Dönertaş HM, Fabian DK, Valenzuela MF, et al. Common genetic associations between age-related diseases. Nat Aging. 2021;1:400–12.

- Sakaue S, Kanai M, Tanigawa Y, et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1415–24.

- Burgess S, Davey Smith G, Davies NM, et al. Guidelines for performing Mendelian randomization investigations: update for summer 2023. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:186.

- Bowden J, Spiller W, Del Greco M F, et al. Improving the visualization, interpretation and analysis of two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization via the Radial plot and Radial regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:1264–78.

- Bowden J, Del Greco M F, Minelli C, et al. Assessing the suitability of summary data for two-sample Mendelian randomization analyses using MR-Egger regression: the role of the I2 statistic. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1961–74.

- Burgess S, Thompson SG. Multivariable Mendelian randomization: the use of pleiotropic genetic variants to estimate causal effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181:251–60.

- Sanderson E, Davey Smith G, Windmeijer F, et al. An examination of multivariable Mendelian randomization in the single-sample and two-sample summary data settings. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48:713–27.

- Sanderson E, Spiller W, Bowden J. Testing and correcting for weak and pleiotropic instruments in two-sample multivariable Mendelian randomization. Statistics in Medicine. 2021.

- Chen S, Francioli LC, Goodrich JK, et al. A genome-wide mutational constraint map quantified from variation in 76,156 human genomes. bioRxiv. 2022;2022.03.20.485034.

- Hodges JK, Cao S, Cladis DP, et al. Lactose Intolerance and Bone Health: The Challenge of Ensuring Adequate Calcium Intake. Nutrients. 2019;11. [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano M, Veneto G, Malservisi S, et al. Lactose malabsorption and intolerance and peak bone mass. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1793–9.

- Boddy S, Islam M, Moll T, et al. Unbiased metabolome screen leads to personalized medicine strategy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Commun. 2022;4:fcac069.

- Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi F. Dairy consumption and body mass index: an inverse relationship. Int J Obes . 2005;29:115–21.

- Braun KV, Erler NS, Kiefte-de Jong JC, et al. Dietary Intake of Protein in Early Childhood Is Associated with Growth Trajectories between 1 and 9 Years of Age. J Nutr. 2016;146:2361–7.

- Betsholtz C. Lipid transport and human brain development. Nat Genet. 2015;47:699–701.

- Burgess S, Davies NM, Thompson SG. Bias due to participant overlap in two-sample Mendelian randomization. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:597–608.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).