1. Introduction

Flow over a flat plate has many applications, and is one of the basic fluid dynamics and heat transfer topics for a better understanding of flows. It also has an important place in boundary layer flows because it is a zero pressure gradient flow, allowing for simplifications. Long and flat surfaces are encountered in many real flows. Examples of situations where the boundary layer forms over long and flat surfaces are flow over a ship's hull, flow over a submarine hull, flow over aircraft wings, and atmospheric flow over flat terrain. The flow characteristics over long and flat surfaces in engineering problems are similar to the flow event over a flat plate. Therefore, understanding the flow over a flat plate is important in terms of understanding the flow characteristics over flat and long surfaces in engineering problems.

In addition to earlier studies (Emmons, 1951), relatively earlier studies on flat plates have shown that inlet turbulence intensity has a significant effect on the transition from laminar to turbulent but that it increases heat transfer only slightly in the laminar region and that the turbulent boundary layer is only slightly affected (Kestin et al., 1961, Büyüktür et al., 1964). More recent studies have shown that high inlet turbulence values produce significant increases in heat transfer (Simonich and Bradshaw 1978, Maciejevski and Moffat 1992a, 1992b). However, it has also been reported that inlet turbulence intensity has no effect in the laminar region (Blair 1983a, 1983b).

The characteristics of laminar and turbulent boundary layers are different. Transition from laminar to turbulent or relaminarization can cause significant changes in the aerodynamic performance of the object. The aerodynamic forces and moments or heat transfer acting on the object in the fluid are directly affected by the position of the laminar to turbulent transition. In the laminar to turbulent transition region, a sudden increase in drag force and heat transfer occurs.

In order to reduce the drag force in the gas turbine airfoil, it is necessary to move the transition from laminar to turbulent to a certain distance from the leading edge. Sometimes, at low Reynolds numbers, the laminar region is extended in low inlet turbulent flow and flow separation occurs in the laminar region before it becomes turbulent, which is not preferred in terms of fuel economy. As a result, even a 1% saving in fuel is very important economically (Wissler 1998). The transition from laminar to turbulent can occur in 80% of the blade in low-pressure turbine blades if the inlet turbulence intensity is low (Suzen and Huang, 1999). Therefore, it is important to be able to correctly solve the transition from laminar to turbulent.

There are many factors that affect the transition to turbulence. These are pressure gradient, Reynolds number, surface roughness, heat transfer and inlet turbulence intensity. These effects cannot fully represent all types of situations with the theoretical or empirical expressions presented previously (Saric 1992). Therefore, it is a subject open to study.

For successful numerical computations, accurate prediction of the laminar to turbulent transition in a flat plate is necessary. We can divide the laminar to turbulent transition mechanism into three as Natural Transition, By-Pass Transition and Separated-Flow Transition. We encounter the first two of these transitions in the flow over a flat plate (zero pressure gradient flow). The characteristics of all three transition mechanisms are explained by Mayle (1991). Natural transition occurs with the formation of Tollmien-Schlichting Waves in the laminar boundary layer. It can be estimated by Linear Stability Analysis (Schlichting 1979). By-Pass transition occurs with the formation of direct turbulence spots in the laminar boundary layer and at high inlet turbulence intensities (Tu>%1). It is also explained analytically by the turbulence spot theory (Emmons 1951).

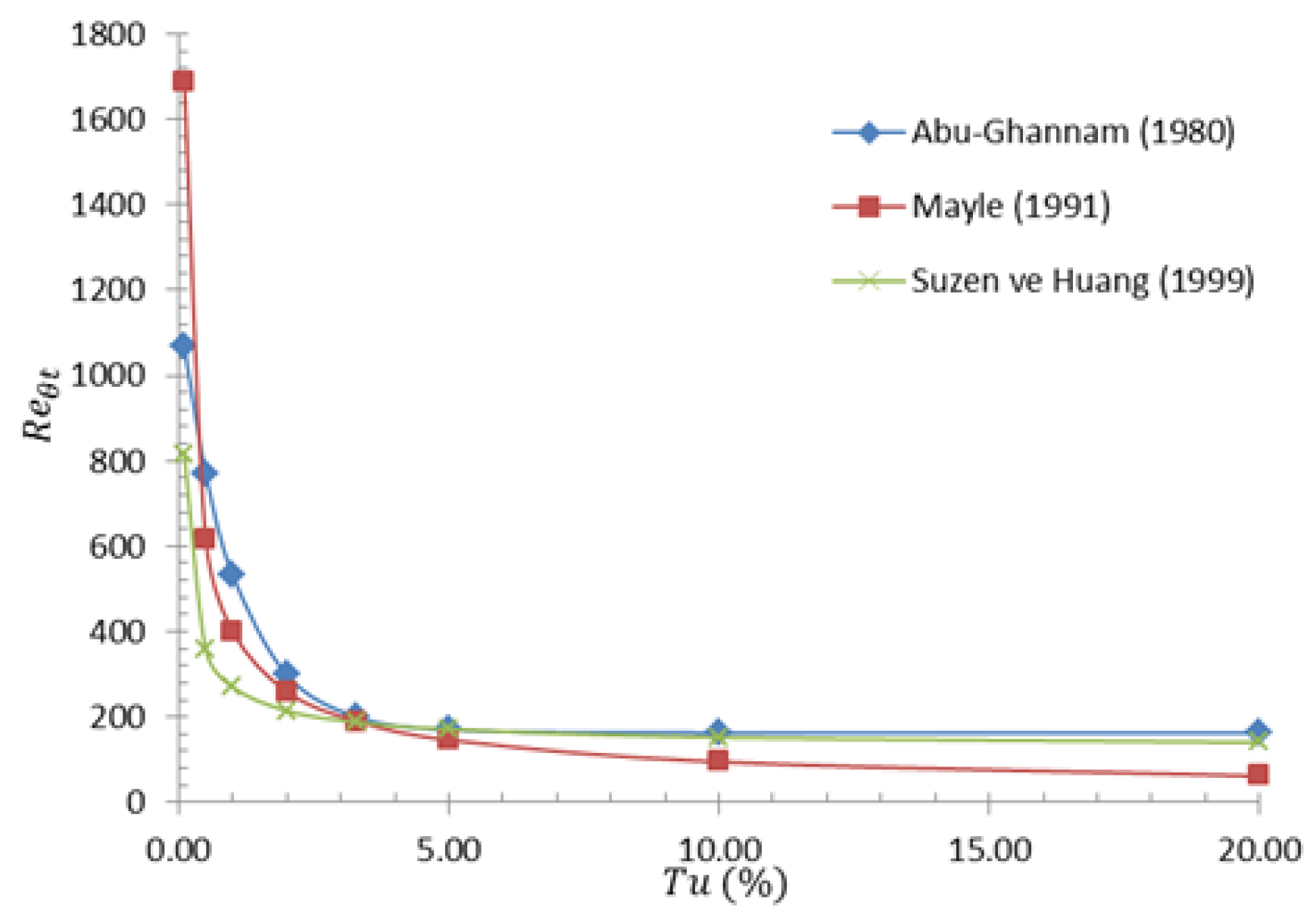

Abu-Ghannam and Shaw (1980) proposed a correlation between the Reynolds number of the transition to turbulence and the inlet turbulence intensity depending on the boundary layer momentum thickness. The correlation is expressed as follows:

The correlation suggested by Mayle (1991) is as follows:

Suzen and Huang (1999) included the following expression for the transition to turbulence in their numerical model:

The correlations expressing the turbulent transition Reynolds number according to the inlet turbulence intensity proposed by Abu-Ghannam and Shaw (1980), Mayle (1991) and Suzen and Huang (1999) mentioned above are compared in

Figure 1.

Taghavi-Zenous et al. (2008) experimentally investigated the laminar to turbulent flow on a flat plate at different inlet turbulence intensities. The measurements were taken with a hot wire velocimetry in the range of 1.5-4.4% inlet turbulence intensity. They stated that with the increase in inlet turbulence intensity, the transition region becomes smaller and regresses towards lower Reynolds numbers and they derived an empirical expression for the turbulent transition Reynolds number depending on the inlet turbulence intensity as follows:

where:

: 3346, 879.9, 419,5;

: -0.3656, -0.8927, -12.93;

: 0.2825, 1.782, 18.29

Figure 1.

Relationship between the Re number and the inlet turbulence intensity (Tu) at the transition to turbulence defined by the boundary layer thickness.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the Re number and the inlet turbulence intensity (Tu) at the transition to turbulence defined by the boundary layer thickness.

Sugawara et al. (1988) experimentally investigated the effect of turbulence intensity created by turbulent grids on heat transfer and flow characteristics. They stated that with the increase in inlet turbulence intensity, the Reynolds number from laminar to turbulent decreases and heat transfer increases, the flow in the laminar region is not affected by the inlet turbulence intensity, and the increase in Nu number is faster at high inlet turbulence intensity levels.

Peneau et al. (2004) investigated the effects of inlet turbulence intensity on the developing boundary layer on a plane plate using the LES (Large Eddy Simulation) turbulence model. They obtained results for different inlet turbulence intensities and compared them with experimental results. They stated that the LES turbulence model is suitable for investigating the effect of inlet turbulence intensity.

Langtry (2006) in his doctoral study modified the SST turbulence model for unstructured mesh structures and presented a correlation-based turbulence model using local variables that can solve the turbulence transition region more accurately. This model was soon included in the ANSYS CFX commercial CFD code. Langtry conducted validation studies on flat plates, helicopter aerodynamics, aircraft wing aerodynamics, and turbine blade aerodynamics in his doctoral study, and demonstrated that this model was more successful than Menter's SST model in the transition region. After this turbulence transition model was integrated into the ANSYS CFX code under the name Gamma-Theta, it was integrated into the other most well-known CFD codes in the market, ANSYS Fluent and Star CD, and became the most widely used turbulence model in the industry for solving the transition region. In the literature, the Gamma-Theta model has been used and validated in studies numerically examining the transition region (Bochon et al., 2008, Piotrowsky et al., 2008, Suluksna and Juntasaro, 2008).

Bochon et al. (2008) stated that the turbulence model that best solves the conjugate heat transfer in the transition region from laminar flow to turbulence is Gamma-Theta and that it is possible to obtain successful results by modifying other 2-equation models like Gamma-Theta.

Piotrowsky et al. (2008) studied the Gamma-Theta transition turbulence model on a plane plate and N3-60_04 turbine airfoil. As a result of the study, they stated that the Gamma-Theta turbulence model is in good agreement with the experimental results and can solve the transition to bypass and wake-induced turbulence very well.

Suluksna and Juntasaro (2008) studied to determine the effects of inlet turbulence intensity and pressure gradient on the transition region flow characteristics numerically using the Gamma-Theta model. They stated that the critical Re number changes only with the turbulence intensity, and that the pressure gradient does not affect the critical Re number much in zero pressure gradient and favorable pressure gradient flows, and the pressure gradient effect can be neglected.

Incropera and DeWitt (2003) mentioned in the literature that the inlet turbulence intensity and surface roughness affect the results up to 25% in forced convection.

Various studies on boundary layer transition are ongoing. A solver for boundary layer transition was developed by Bhushan and Walters (2014). Fabrizio (2014) investigated the critical phenomena in laminar-turbulent transition with a mean field model. A new turbulence model for modeling the turbulent transition according to mechanical priorities was proposed by Vizinho et al. (2015). The effects of wall heating on the boundary layer transition on a flat plate were investigated numerically by Subaşı and Güneş (2015). An evaluation of Reynolds Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS Reynolds Averaged Navşer-Stokes) turbulence models in convective heat transfer was made numerically by Abdollahzadeh et al. (2017). A new laminar kinetic energy model for the prediction of pre-transition velocity fluctuations and boundary layer transition was presented by Medina et al. (2018). Lienhard (2020) proposed a correlation for heat transfer in plane plate boundary layers under laminar, transitional and turbulent flow conditions.

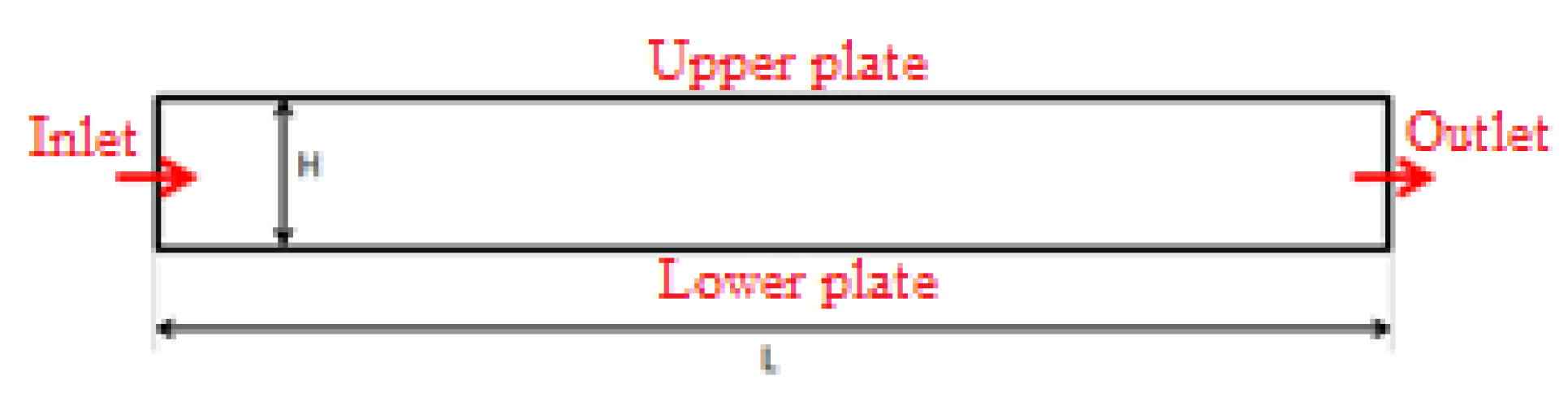

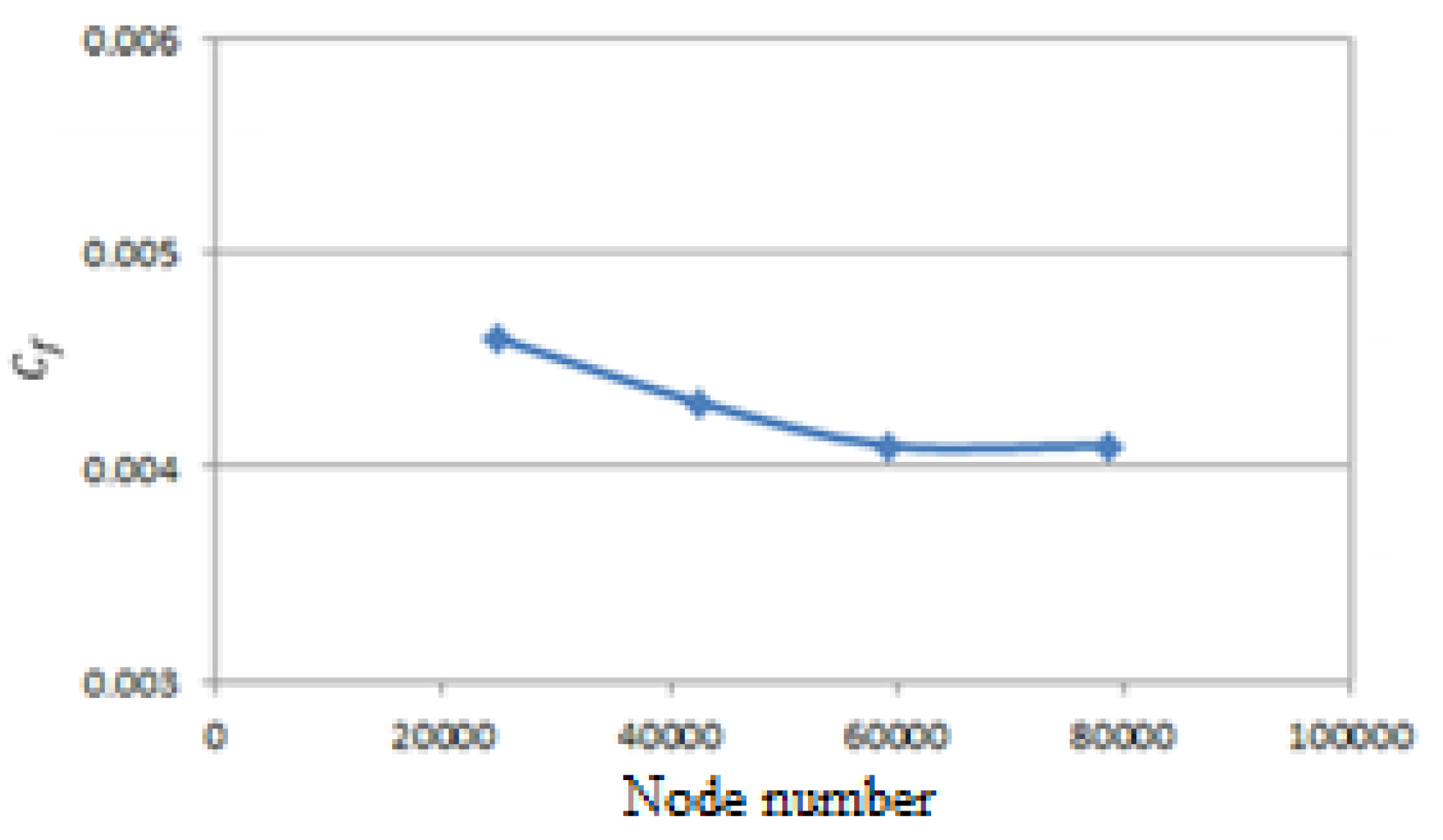

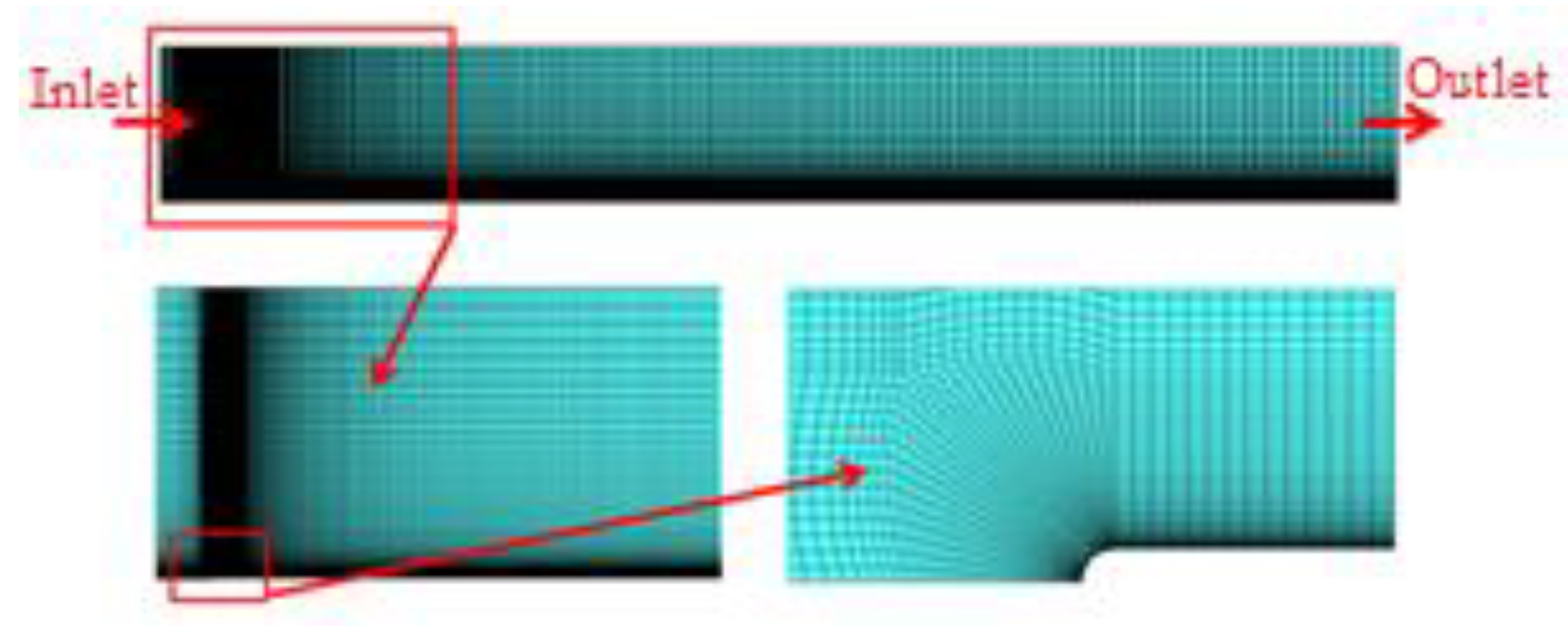

As can be understood from the above studies, the findings in some studies contradict each other and since the effect of external turbulence on the flat plate is encountered in important application areas, studies on this subject are needed. Since the flow on the flat plate is frequently encountered in engineering problems, it is important to develop basic flow equations such as boundary layer for flow on the flat plate, to control the boundary layer and to examine the transition to turbulence. In this study, the effects of the inlet turbulence level on the zero pressure gradient flow on the flat plate based on the ERCOFTAC T3A test setup were investigated by comparing various turbulence models and it was determined that the Gamma-Theta (GT) model was the most suitable model. Then, using this model, the effect of turbulence intensity on the friction coefficient (Cf) was calculated numerically by keeping the integral length scale constant and the results were given in comparison with the experimental results.

3. Results and Discussion

Laminar and turbulent numerical solutions for the ERCOFTAC T3A experimental test case on a flat plate are given and discussed in

Figure 5 below.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Gamma-Theta (GT), Std. k-ɛ, RNG k-ɛ, Std. k-ω and SST k-ω turbulence models (This study).

Figure 5.

Comparison of Gamma-Theta (GT), Std. k-ɛ, RNG k-ɛ, Std. k-ω and SST k-ω turbulence models (This study).

When defining the Reynolds number in the flow on a flat plate, the characteristic length is used as the length in the flow direction. In

Figure 5, from the experimental results, we see that the transition to turbulence begins at a local Re number of approximately 140000 in the flow and that the flow becomes fully turbulent at a local Re number of approximately 270000.

In

Figure 5, it is seen that the laminar numerical solution gives results that are inconsistent with the experimental data, as expected, in the turbulent transition and turbulent flow regions. It is seen that the results obtained using the Std. k-ɛ, Std. k-ω, SST k- ω, and RNG k-ɛ turbulence models are also inconsistent in the laminar and turbulent transition regions, as expected. As can be seen in

Figure 5, the solutions obtained with the Gamma-Theta-SST turbulent transition model are in agreement with the experimental results, unlike the other models, in the laminar, turbulent transition, and turbulent flow regions.

The above results show that the Gamma-Theta model is a suitable model for solving laminar, turbulent transition and turbulent regions in flat plate flow. However, although the compatibility with the experimental results in the turbulent transition region is not as good as in the laminar and turbulent regions, it can be said that it is at a quite acceptable level when the complexity of the flow in the transition region and the fact that other turbulence models cannot capture this region at all are taken into account. In the transition region, the Gamma-Theta model starts the transition earlier than the experimental data and completes the transition a little earlier. The friction coefficient is estimated at most 40% higher than the experimental results in this region. These results are for the ERCOFTAC T3A inlet turbulence intensity Tu=3.3 experimental case, and the turbulence length scale is not specified in this experimental case and the length scale is taken as LS=0.026 m in the calculations in this study. A certain part of the approximately 40% deviation from the experimental results in this region can be attributed to this.

When we inspect

Figure 5, if the flow were completely turbulent (Re

x > 270000), it is seen that the Gamma-Theta model is the most suitable turbulence model, and the model with the same suitability as this model is the Std. k-ω model. The other most suitable models are the SST- k-ω, Std. k-ɛ and RNG k-ɛ models, respectively. However, although the Gamma-Theta and Std. k-ω models are almost in agreement with the experimental data; the other models predict the friction coefficient below the experimental data at Reynolds numbers smaller than Re

x = 440000, and it can be said that all of them show almost the same performance. Again, if the flow were completely laminar, it is seen from

Figure 5 that the numerical solution is in very good agreement with the experimental data in the laminar region (0 < Re < 170000).

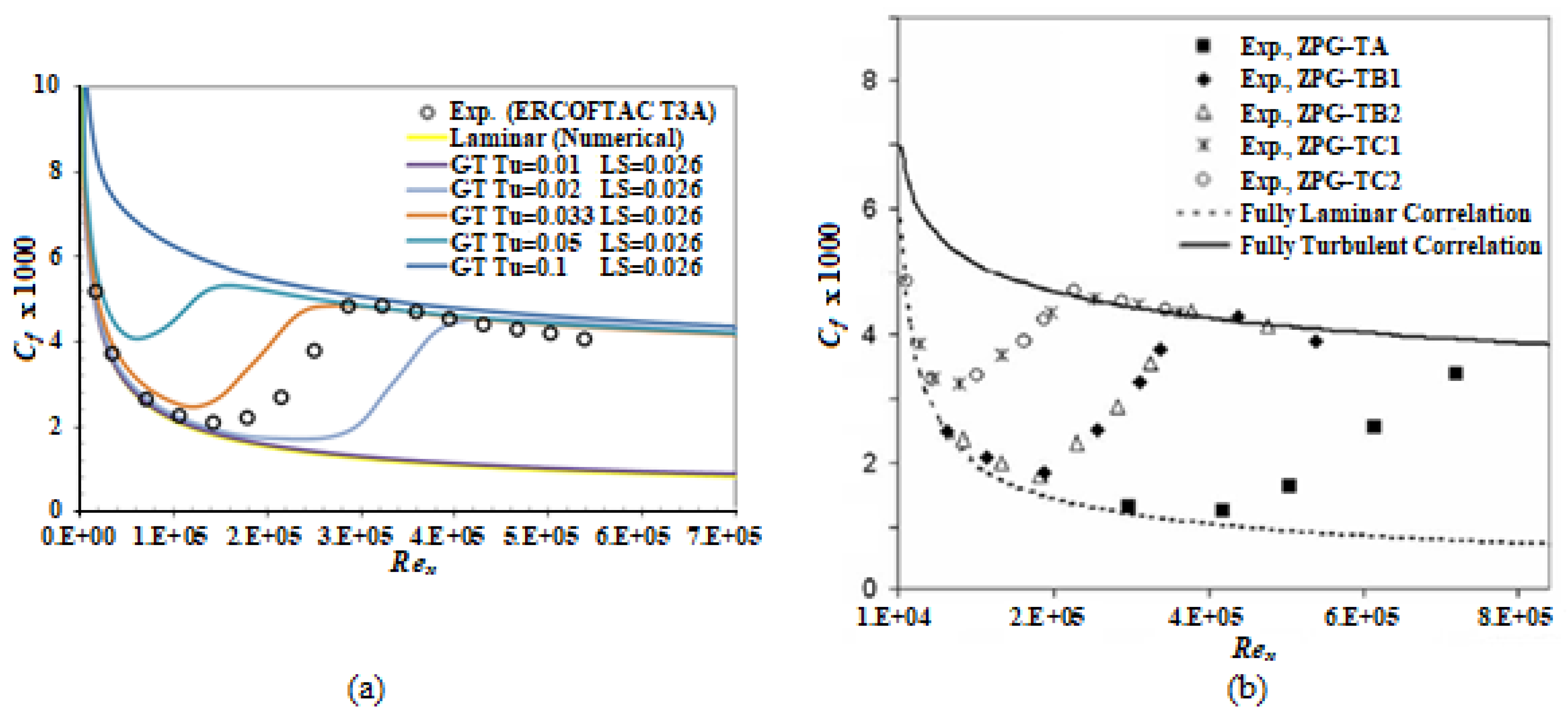

The Gamma-Theta turbulence model, which is the most suitable model to investigate the effect of inlet turbulence intensity, was selected and the effect of inlet turbulence intensity was investigated with this model. Five different calculations were made by keeping the turbulence length scale constant and changing the inlet turbulence intensity between 1% and 10%. The results are shown in

Figure 6a together with the experimental and laminar numerical solution results. The turbulent transition regions are shown in

Table 2. In addition, the results of the experimental study of Taghavi-Zenous et al. (2008) are given in

Figure 6b for comparison. The experimental conditions of this experimental study are also shown in

Table 3.

Table 2.

Transition regions of inlet turbulence intensity to turbulence on the plane plate in the Gamma-Theta turbulence model (This Study).

Table 2.

Transition regions of inlet turbulence intensity to turbulence on the plane plate in the Gamma-Theta turbulence model (This Study).

| Tu (%) |

LS (m) |

Inlet Velocity (m/s) |

Laminar

Region |

Transition Region of Turbulence |

Turbulent Region |

| 1 |

0.026 |

5.3 |

0 < Re < ∞ |

- |

- |

| 2 |

0.026 |

5.3 |

Re < 280000 |

280000 < Re < 400000 |

Re > 400000 |

| 3.3 |

0.026 |

5.3 |

Re < 115000 |

115000 < Re < 260000 |

Re > 260000 |

| 5 |

0.026 |

5.3 |

Re < 60000 |

60000 < Re < 150000 |

Re > 150000 |

| 10 |

0.026 |

5.3 |

- |

- |

0 < Re < ∞ |

Table 3.

Experimental conditions (Taghavi-Zenous vd., 2008).

Table 3.

Experimental conditions (Taghavi-Zenous vd., 2008).

| Deney Kodu |

Tu (%) |

LS (m) |

Giriş Hızı (m/s) |

| ZPG-TA |

1.5 |

0.009 |

15.5 |

| ZPG-TB1 |

3.2 |

0.0105 |

12 |

| ZPG-TB2 |

3.3 |

0.011 |

15 |

| ZPG-TC1 |

4.3 |

0.0126 |

8.35 |

| ZPG-TC2 |

4.4 |

0.0129 |

10.5 |

Since the transition to turbulence in the flow occurs when the critical Re number is exceeded, the change in the turbulence transition region according to the Re number is given in

Table 2 for different inlet turbulence intensities. As the inlet turbulence intensity increases, the transition to turbulence occurs at lower Re numbers. In the case where the inlet turbulence intensity is 1%, since the calculations are made in the range of 0 < Re < 700000 and the turbulence transition region is outside this range, the turbulence transition region could not be determined and is shown with a “-” in

Table 2. In the case where the inlet turbulence intensity is 10%, the flow occurs directly as turbulent and this time there is no laminar and turbulent transition region, so it is shown with a “-” in

Table 2.

Figure 6.

Cf results of Gamma-Theta (GT) turbulence model for different inlet turbulence intensities a) This study b) Taghavi-Zenous et al. (2008).

Figure 6.

Cf results of Gamma-Theta (GT) turbulence model for different inlet turbulence intensities a) This study b) Taghavi-Zenous et al. (2008).

As seen in

Figure 6a, with the increase in the inlet turbulence intensity, the transition to turbulence became easier and the laminar region shortened. Some results in

Figure 6a are summarized in

Table 2 and it can be seen that as the turbulence intensity increases, the transition region to turbulence narrows. This situation was also determined in the experimental study of Taghavi-Zenous et al. (2008).

When

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b are examined, it can be easily said that the numerical results in this study are consistent with the experimental results. Although the turbulence length scale was kept constant in this study, it should not be forgotten that this consistency should be evaluated qualitatively since it was not kept constant in the experimental study. Because, as stated in the studies of Hancock and Bradshaw (1983) and Iyer and Yavuzkurt (1999), where their studies were evaluated, the turbulence length scale is also effective on the boundary layer along with the turbulence intensity.