1. Introduction

The emotional and psychological well-being of healthcare workers, especially those involved in high-stress sectors such as substance abuse treatment, has garnered significant attention over recent years. In particular, burnout and emotional dysregulation, including anger, have been identified as critical factors that may compromise the effectiveness and well-being of professionals in these environments. Healthcare workers who assist individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs) often face multifaceted challenges, including emotionally taxing patient interactions, exposure to traumatic stories, and systemic resource limitations. These factors contribute to a particularly vulnerable group for psychological distress, where the intersection of burnout and anger becomes a crucial area of investigation.

Burnout is broadly defined as a psychological syndrome that arises in response to prolonged exposure to interpersonal stressors at work. It is conceptualized along three primary dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment (Maslach et al., 2001). Emotional exhaustion refers to feelings of being emotionally overextended and depleted of one’s emotional resources, whereas depersonalization involves a cynical and detached response to various aspects of the job. The third dimension, reduced personal accomplishment, captures the tendency of individuals to evaluate themselves negatively in terms of job performance. These components have been shown to interact, leading to a progressive loss of motivation and engagement with work, which can severely impact both personal well-being and job performance (Demerouti et al., 2001).

In the context of substance abuse rehabilitation services, workers are particularly susceptible to burnout. Numerous studies indicate that addiction professionals experience high levels of emotional exhaustion due to the challenging nature of their work, including frequent relapses in patients, limited therapeutic successes, and systemic inefficiencies (Gallon et al., 2003). These stressors are compounded by societal stigma toward addiction, which can further alienate workers and reduce their sense of professional accomplishment (Morse et al., 2012). Moreover, the exposure to traumatic events and chronic distress among clients suffering from addiction significantly increases the risk of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in workers (Bride et al., 2007). This burnout may not only affect their mental health but also compromise the quality of care provided, as emotionally exhausted staff may struggle to maintain empathy and effective therapeutic relationships (Leiter, Bakker, & Maslach, 2014).

In parallel with burnout, emotional dysregulation, particularly anger, has emerged as an important factor influencing the mental health of healthcare workers. Anger, a complex emotion that can manifest in response to perceived threats or frustration, plays a significant role in both professional and personal domains (Averill, 1983). The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2), developed by Spielberger (1999), is a widely used instrument for assessing anger. It differentiates between state anger (the emotional reaction to a specific situation), trait anger (a stable tendency to experience anger across a variety of situations), and the various ways in which individuals express or suppress anger.

In high-stress work environments, such as substance abuse services, workers may experience recurrent frustration and powerlessness due to the chronic nature of addiction, frequent patient relapses, and structural constraints like insufficient resources or lack of support (Lasalvia et al., 2009). Over time, these stressors can culminate in heightened levels of trait anger, where individuals may develop a chronic predisposition to experience and express anger. Studies have shown that anger can exacerbate the emotional exhaustion component of burnout, as workers who struggle to manage their frustration are more likely to feel overwhelmed by the demands of their job (Piper et al., 1989).

Moreover, the manner in which anger is expressed or suppressed plays a crucial role in the psychological well-being of healthcare workers. Anger-in (the tendency to suppress anger) has been associated with a range of negative mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety, while anger-out (the external expression of anger) can lead to interpersonal conflicts and reduced job satisfaction (Kokkinos, 2007). For SERD operators, who must maintain therapeutic relationships with highly vulnerable patients, poorly managed anger can disrupt the care process and exacerbate their own emotional exhaustion. Additionally, research has demonstrated that anger control (the ability to regulate the intensity and expression of anger) is a protective factor against burnout, as individuals who can effectively manage their emotions are better equipped to cope with the demands of stressful work environments (Brondolo et al., 1999).

The relationship between burnout and anger in healthcare settings, particularly in addiction services, is underexplored despite the well-documented emotional challenges faced by these workers. The emotional toll of addiction treatment, combined with the high levels of burnout and anger observed in similar high-stress occupations, suggests that SERD operators may be at heightened risk for psychological distress. Burnout and anger not only affect individual well-being but may also influence the quality of care provided to patients, potentially creating a cycle of negative outcomes for both healthcare providers and their clients.

Several studies have addressed the broader emotional impacts on healthcare workers, identifying common emotional responses, including frustration and anger, as reactions to the stressors inherent in their work (Salyers et al., 2017). These emotional responses can contribute to the gradual buildup of burnout. Healthcare workers may initially experience frustration due to organizational inefficiencies, role ambiguity, or the lack of perceived progress in patient care (Lloyd et al., 2002). Over time, if these frustrations remain unaddressed, they can develop into chronic anger, further compounding feelings of exhaustion and detachment (Faragher et al., 2005).

Moreover, studies have demonstrated the physiological impact of anger and burnout. Chronic stress, combined with the emotional strain of continuous anger suppression or expression, has been linked to adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and impaired immune function (Suls & Bunde, 2005). This highlights the importance of addressing both burnout and emotional dysregulation, such as anger, in healthcare settings to promote not only psychological but also physical health.

Another important aspect to consider is the role of workplace interventions and organizational culture in mitigating burnout and anger. Research suggests that healthcare organizations that foster a supportive environment, provide access to mental health resources, and promote work-life balance can significantly reduce burnout and improve employee well-being. Implementing resilience training, mindfulness-based interventions, and anger management programs may be particularly effective in helping workers manage the emotional challenges associated with addiction treatment (West et al., 2018).

In summary, the current study aims to bridge the gap in understanding the interplay between burnout and anger among SERD operators in Calabria and Sicily. By using the STAXI-2 and MBI, this research seeks to provide a comprehensive assessment of the emotional and psychological well-being of workers in addiction services, identifying potential areas for intervention and support. Given the high levels of emotional exhaustion and anger reported in similar populations, it is crucial to investigate how these two constructs interact in this specific context and what implications they may have for both individual workers and the broader healthcare system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The current study employs a cross-sectional design to assess the levels of burnout and anger among operators of public addiction services (SERD) in Calabria and Sicily. Cross-sectional studies are frequently used in psychological research to provide a snapshot of the population at a specific point in time, which allows for the identification of correlations and potential risk factors within the sample (Levin, 2006). Given the objective of this research—to explore the relationship between burnout and anger in a highly specialized healthcare setting—this methodology was considered appropriate for capturing the relevant psychological constructs.

The decision to focus on workers in SERD services was motivated by previous literature, which has demonstrated that healthcare professionals involved in addiction services are exposed to unique stressors compared to other medical and psychological fields. Substance use disorder (SUD) treatment is associated with high levels of emotional labor, the need for constant empathy, and frequent exposure to traumatic or challenging patient narratives, all of which contribute to burnout and emotional dysregulation (Gallon et al., 2003; Morse et al., 2012). Furthermore, the regions of Calabria and Sicily were chosen because of their specific socioeconomic and healthcare challenges, which can exacerbate the stress experienced by addiction professionals (Lasalvia et al., 2009).

2.2. Participants

A total of 124 operators from various SERD centers across Calabria and Sicily were recruited for the study. The inclusion criteria specified that participants must be employed in a SERD for a minimum of one year and be directly involved in patient care or service management. Participants included nurses, social workers, psychologists, and administrative staff, as these roles are all integral to the multidisciplinary nature of addiction treatment (Shoptaw et al., 2005). Exclusion criteria were established to omit participants who had been in their role for less than a year or who were not directly engaged with patients, to ensure that the sample was representative of those most likely to experience burnout and emotional dysregulation due to direct patient interaction (Stewart et al., 2003).

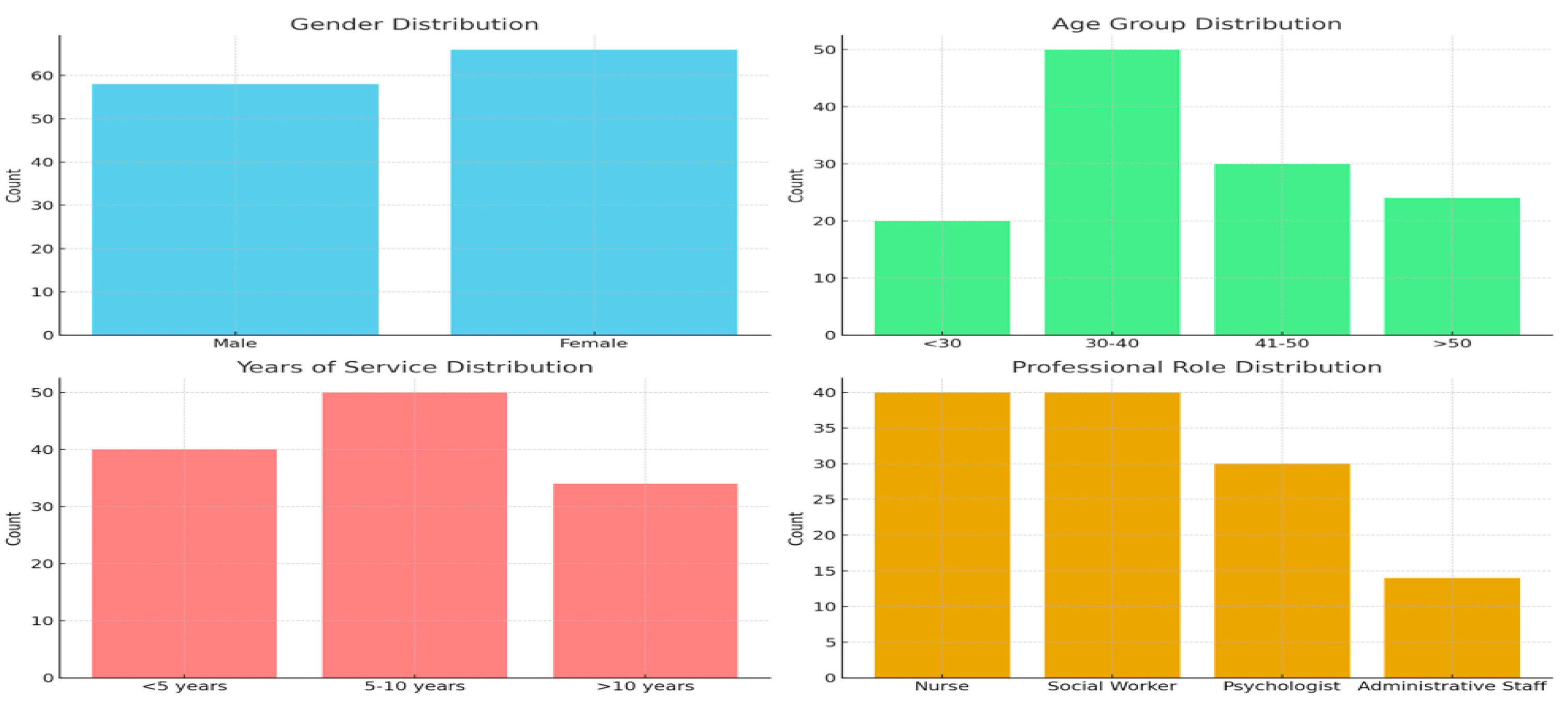

The sample was composed of 58 males and 66 females, with a mean age of 39.2 years (SD = 9.8). The participants’ average length of service in the addiction field was 7.6 years (SD = 3.4), reflecting a broad range of professional experience (

Figure 1). Gender, age, professional role, and length of service were recorded to explore whether these variables moderated the relationships between anger and burnout, as demographic factors have been shown to influence burnout levels in previous research (Maslach et al., 2001; Acker, 2004). For example, studies have demonstrated that females in healthcare are more likely to experience emotional exhaustion than males, which could lead to differences in burnout profiles between genders (Purvanova & Muros, 2010).

2.3. Instruments

Two primary instruments were used in this study to measure the psychological constructs of interest: the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2).

2.4. Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)

The MBI is widely regarded as the gold standard for measuring burnout and has been extensively validated across a variety of professional groups, including healthcare workers (Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter, 1996). The MBI assesses three distinct dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.

1. Emotional Exhaustion (EE) refers to feelings of being emotionally drained and overwhelmed by work demands. This dimension is considered the core component of burnout and has been linked to both mental and physical health issues in healthcare workers (Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

2. Depersonalization (DP) reflects a detached or impersonal response to patients or clients, often manifesting as cynicism or negative attitudes towards others. This dimension is particularly relevant in the context of addiction services, where patients may present with challenging behaviors, potentially exacerbating feelings of depersonalization among staff (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998).

3. Personal Accomplishment (PA) is the sense of competence and successful achievement in one’s work. A low sense of personal accomplishment has been associated with feelings of inadequacy and dissatisfaction in professional roles (Cordes & Dougherty, 1993).

In this study, the Italian version of the MBI was used, which has been validated for use in the Italian healthcare context. The MBI consists of 22 items, rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“every day”). Higher scores on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales indicate higher levels of burnout, while lower scores on the personal accomplishment subscale are indicative of burnout.

2.5. State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2)

The STAXI-2 is a well-established tool for measuring both the intensity of anger as an emotional state (state anger) and the frequency with which anger is experienced as a personality trait (trait anger) (Spielberger, 1999). The inventory also assesses how anger is expressed or controlled, providing a comprehensive evaluation of anger-related processes.

1. State Anger measures the intensity of angry feelings at a particular moment. This subscale is important for understanding how situational factors in the workplace may elicit immediate emotional responses.

2. Trait Anger evaluates how often individuals feel anger over time, making it a useful measure of chronic emotional tendencies.

3. Anger Expression and Control scales assess how individuals express their anger (either outwardly or inwardly) and their ability to control angry feelings. High levels of anger expression (either anger-out or anger-in) have been linked to negative health outcomes, whereas effective anger control is considered a protective factor against psychological distress (Brondolo et al., 1999).

The STAXI-2 has been widely used in healthcare settings to assess emotional regulation, including its application in addiction services (Evans et al., 2013). For the purposes of this study, the Italian version of the STAXI-2, validated for use in clinical and occupational settings, was employed. The questionnaire consists of 57 items, rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (“almost never”) to 4 (“almost always”), with higher scores indicating greater difficulties with anger regulation.

2.6. Procedure

The study followed a structured and ethical approach to data collection, adhering to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects (World Medical Association, 2013). Prior to data collection, ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committees of both the Calabria and Sicily regional healthcare authorities.

2.7. Recruitment and Data Collection

Participants were recruited through a combination of email invitations and face-to-face meetings with SERD center directors. The study was introduced as an opportunity to contribute to the understanding of stress and emotional well-being among addiction service professionals. Participation was voluntary, and all participants provided informed consent prior to enrollment.

Data collection took place over a period of three months, with participants completing the MBI and STAXI-2 questionnaires during scheduled breaks or after their work shifts to minimize interference with their professional duties. On average, completion of both instruments took approximately 30–40 minutes. To ensure the confidentiality of responses, participants completed the questionnaires anonymously, and no identifying information was collected.

2.8. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26, employing a combination of descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and multivariate techniques to assess the relationships between the variables of interest.

2.9. Descriptive Statistics

First, descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies) were computed for all demographic variables, as well as for scores on the MBI and STAXI-2 subscales. Descriptive analysis allowed for an initial understanding of the sample’s burnout and anger profiles and served as the basis for subsequent inferential analyses.

2.10. Reliability Analysis

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for each subscale of the MBI and STAXI-2 to assess internal consistency reliability. A Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.70 or higher is generally considered acceptable, indicating that the items within each subscale are measuring the same underlying construct (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

2.11. Correlation Analysis

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to explore the relationships between the three dimensions of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment) and the various subscales of anger measured by the STAXI-2 (trait anger, state anger, anger expression, and anger control). Correlation analysis is a commonly employed method for assessing linear relationships between variables in psychological research.

2.12. Multivariate Analysis

To assess the predictive relationships between anger and burnout, multiple regression analyses were performed. In the first model, emotional exhaustion was the dependent variable, and trait anger, state anger, anger expression, and anger control were entered as independent variables. Subsequent models were used to explore predictors of depersonalization and personal accomplishment. Demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, length of service) were included as covariates to control for their potential confounding effects.

2.13. ANOVA and Group Comparisons

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine whether there were significant differences in burnout and anger levels based on demographic variables such as gender, professional role, and length of service. Post hoc analyses with Bonferroni corrections were conducted to explore significant main effects and interactions.

3. Results

The results of this study provide an in-depth analysis of the levels of burnout and anger experienced by SERD operators in Calabria and Sicily, as measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2). The data revealed significant findings in terms of both the prevalence of burnout and anger, as well as the interrelationships between these constructs. The results are presented in four primary sections: descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, regression analyses, and group comparisons.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Burnout Levels

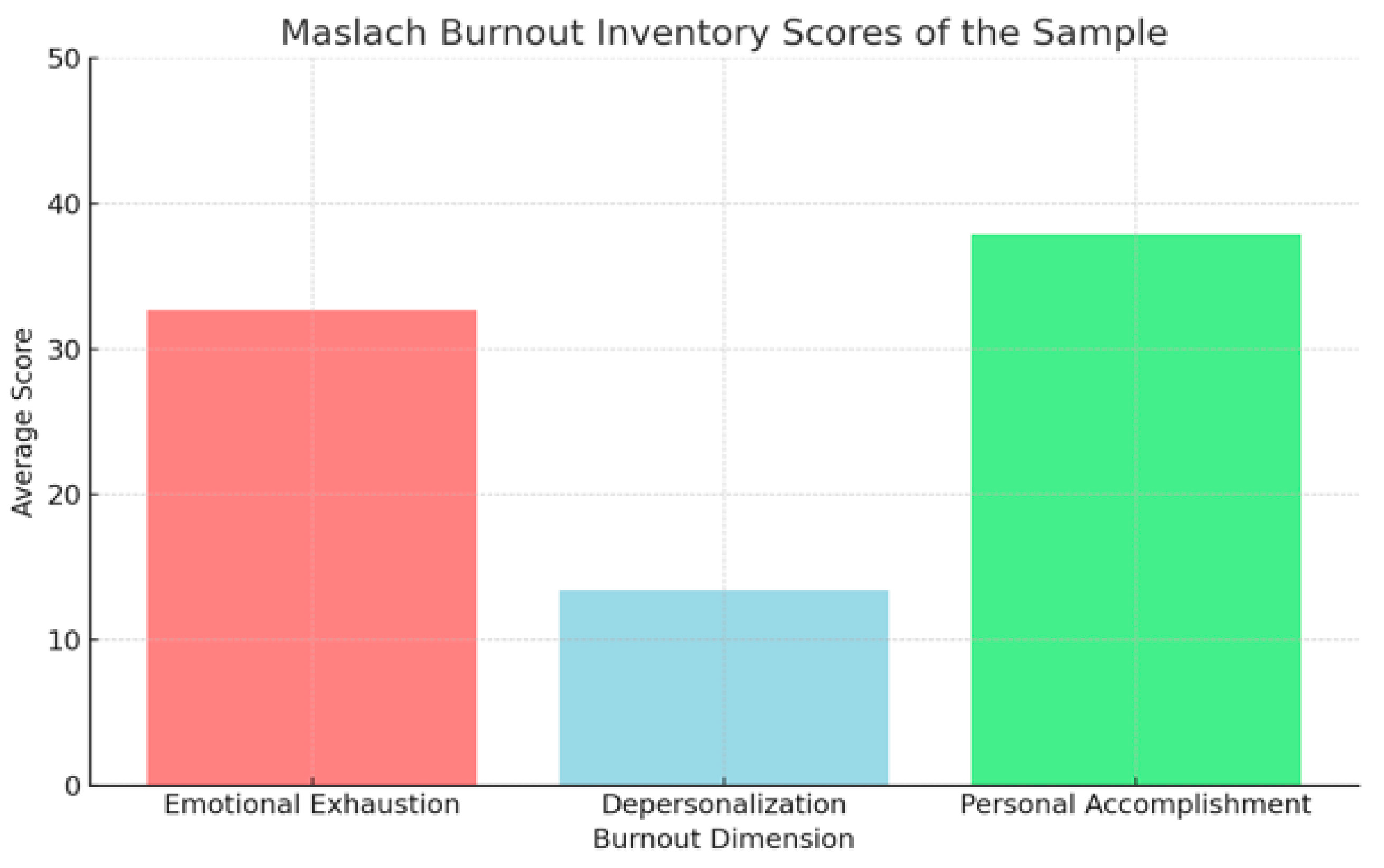

Overall, the sample of SERD operators displayed moderate to high levels of burnout, particularly in the domain of emotional exhaustion. The mean score for emotional exhaustion was 32.7 (SD = 8.9), which is consistent with findings from other studies of healthcare professionals in high-stress environments (Maslach & Leiter, 2016; Hillhouse et al., 2010). Emotional exhaustion was notably higher in female participants, with an average score of 34.2 (SD = 8.6), compared to 30.9 (SD = 8.9) in males (

Figure 2). These findings align with previous research indicating that women in caregiving roles are more prone to emotional exhaustion due to factors such as role conflict, higher expectations for empathy, and societal pressures (Mayor, 2015; Purvanova & Muros, 2010).

In terms of depersonalization, the mean score was 13.4 (SD = 5.7) (

Figure 2), reflecting moderate levels of cynicism and detachment among the participants. Depersonalization was particularly pronounced in operators who had been working in the addiction field for more than 10 years, with a mean score of 15.1 (SD = 5.9) (

Figure 2), suggesting that prolonged exposure to patient suffering and relapse may contribute to emotional detachment (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). Interestingly, no significant differences in depersonalization were observed between genders.

Regarding personal accomplishment, participants reported relatively high levels of perceived efficacy, with a mean score of 37.9 (SD = 6.2). However, those with less than five years of service in addiction treatment reported higher personal accomplishment (M = 39.6, SD = 5.8), compared to those with more than 10 years of service (M = 35.7, SD = 6.4) (

Figure 2). This trend suggests that as the length of service increases, workers may experience a decline in their sense of personal accomplishment, which could be attributed to the challenges of treating chronic addiction (Hillhouse et al., 2010; Gallon et al., 2003).

3.2. Anger Levels

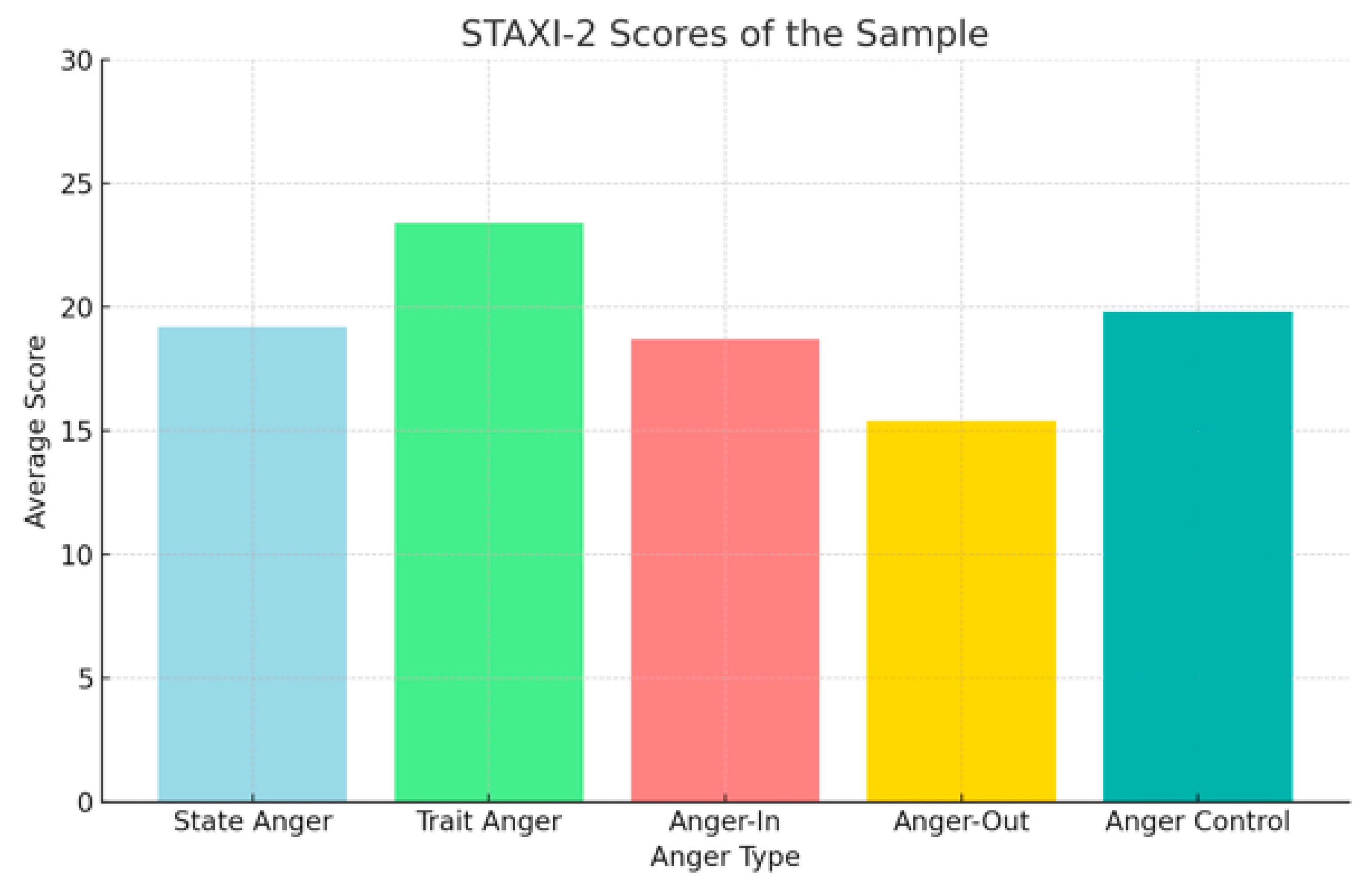

The analysis of anger using the STAXI-2 revealed that trait anger was moderately elevated among SERD operators, with a mean score of 23.4 (SD = 6.5), similar to levels reported in other high-stress healthcare settings (Brondolo et al., 1999; Del Vecchio & O’Leary, 2004). Participants who scored high on trait anger were found to report frequent feelings of frustration and helplessness in their work, particularly when dealing with patients who exhibited resistance to treatment or frequent relapse episodes.

State anger, or anger experienced in response to specific situations, was also moderately elevated, with a mean score of 19.2 (SD = 4.9). Participants described situations in which they felt anger due to systemic inefficiencies, such as understaffing, lack of resources, and bureaucratic constraints, which align with the broader literature on stress in addiction services (Lasalvia et al., 2009; Poghosyan et al., 2010).

With regard to anger expression, participants tended to exhibit a preference for anger-in, or the suppression of anger, with a mean score of 18.7 (SD = 5.4). This finding suggests that many SERD operators may internalize their frustration, potentially exacerbating emotional exhaustion and other negative psychological outcomes. Conversely, anger-out, or the outward expression of anger, had a lower mean score of 15.4 (SD = 4.2), indicating that most participants refrained from overt expressions of anger in the workplace. However, those who scored high on anger-out reported experiencing interpersonal conflicts with colleagues, which could further contribute to burnout (Lloyd et al., 2002; Forbes et al., 2008).

3.3. Correlational Analysis

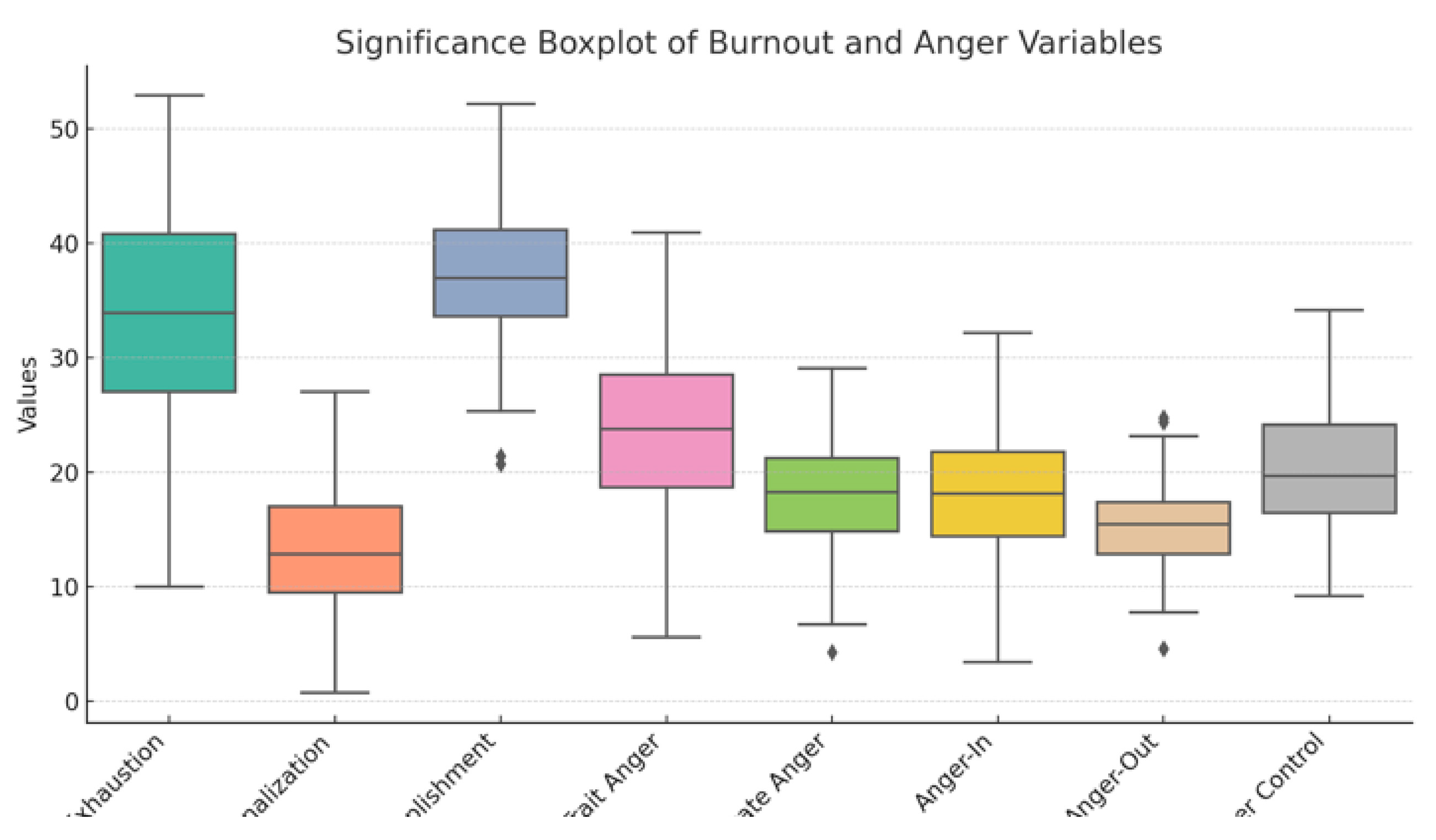

Correlation analyses were performed to explore the relationships between the dimensions of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment) and the anger variables (trait anger, state anger, anger expression, and anger control). The results demonstrated several significant correlations:

- Emotional exhaustion was positively correlated with trait anger (r = .45, p < .01), indicating that individuals who frequently experience anger across situations are more likely to feel emotionally drained by their work. This supports previous research showing that chronic emotional arousal, such as anger, can exacerbate feelings of fatigue and overwhelm (Del Vecchio et al., 2004; Faragheret al, 2005).

- Depersonalization was significantly correlated with both state anger (r = .33, p < .05) (

Figure 3) and anger-in (r = .41, p < .01), suggesting that operators who suppress their anger may become more detached from their patients over time. This finding is consistent with the emotional suppression literature, which posits that suppressing negative emotions can lead to emotional numbness and a reduced capacity for empathy (Gross & John, 2003).

- Personal accomplishment was negatively correlated with trait anger (r = -.29, p < .05) (

Figure 3), indicating that individuals with a chronic tendency toward anger are less likely to feel effective in their professional roles. This is in line with studies that have shown how emotional dysregulation undermines self-efficacy and contributes to feelings of inadequacy (Bandura, 1997).

These findings suggest a robust relationship between anger, particularly trait anger and anger-in, and the emotional components of burnout, highlighting the need for interventions that target emotional regulation in this population.

3.4. Regression Analysis

Multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the predictive value of anger variables on burnout dimensions, controlling for demographic variables such as age, gender, and years of service. The results revealed that:

1. Trait anger was a significant predictor of emotional exhaustion (β = .36, p < .01), accounting for 19% of the variance in emotional exhaustion scores. This finding is consistent with prior research that identifies trait anger as a chronic stressor that heightens vulnerability to emotional fatigue (Alarcon et al., 2009; Gross & John, 2003).

2. Anger-in was a significant predictor of depersonalization (β = .28, p < .05), explaining 13% of the variance in depersonalization. This supports the notion that internalizing anger may lead to emotional disengagement and cynicism towards patients, a common feature of depersonalization (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998; Williams et al., 2010).

3. Anger control was a significant negative predictor of personal accomplishment (β = -.22, p < .05), suggesting that individuals who are better able to regulate their anger may maintain a stronger sense of efficacy in their work. This finding aligns with studies that have shown the protective role of emotional regulation in maintaining professional competence (Brondolo et al., 1999; Grossman, 2014).

These results (

Figure 3) indicate that while anger and burnout are closely linked, different aspects of anger (trait, state, expression) may have differential effects on the various dimensions of burnout. Specifically, trait anger and anger suppression appear to play a central role in exacerbating emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while anger control is protective against feelings of inefficacy.

3.5. Group Differences

ANOVA analyses were conducted to investigate potential group differences in burnout and anger based on gender, professional role, and length of service. The results showed that:

- Gender differences were significant for emotional exhaustion, with females reporting higher levels of exhaustion compared to males (F(1, 122) = 4.67, p < .05). This finding is consistent with existing literature suggesting that female healthcare workers are more vulnerable to emotional exhaustion due to gendered expectations around caregiving and emotional labor (Innstrand et al., 2009; Purvanova & Muros, 2010).

- Professional role also played a significant role in burnout levels. Nurses and social workers reported higher levels of depersonalization compared to psychologists and administrative staff (F(3, 120) = 5.12, p < .01), which may be attributed to the direct and often intense nature of patient interactions in these roles (Greenglass et al., 1990; Acker, 2004).

- Length of service was associated with differences in personal accomplishment, with operators who had been in the field for more than 10 years reporting lower levels of accomplishment compared to those with less experience (F(2, 121) = 6.15, p < .01). This is in line with previous research suggesting that burnout tends to increase over time in high-stress professions (Halbesleben & Demerouti, 2005; Demerouti et al., 2001).

4. Discussion

The present study offers important insights into the complex relationship between burnout and anger among healthcare professionals working in substance use disorder (SUD) services in Calabria and Sicily. The findings revealed that both burnout and anger are prevalent among SERD operators, and their interplay has significant implications for the mental health and professional efficacy of these workers. In this discussion, we will analyze these findings in light of existing literature, explore potential underlying mechanisms, and consider practical implications for interventions and policy.

4.1. Burnout Among SERD Operators

The data from this study confirm that SERD operators are at a heightened risk for burnout, particularly in the dimension of emotional exhaustion. The mean emotional exhaustion score of 32.7 is consistent with burnout levels reported in other high-stress healthcare settings, such as emergency departments, oncology units, and mental health services (Embriaco et al., 2007; Portoghese et al., 2014). Emotional exhaustion, which reflects feelings of being emotionally depleted and overwhelmed by the demands of the job, was especially pronounced among female participants. This gender difference is not unique to addiction services and has been well-documented in the burnout literature. Research suggests that women in healthcare may experience greater emotional exhaustion due to gendered expectations around caregiving, higher levels of empathy, and the emotional labor associated with their roles (Purvanova & Muros, 2010; McTernan, Dollard, & LaMontagne, 2013).

The relatively high levels of depersonalization reported by participants, particularly among those with more than ten years of service, highlight the potential for long-term exposure to emotionally taxing patient interactions to result in detachment or cynicism. This is consistent with Maslach’s burnout theory, which posits that depersonalization is a defense mechanism that individuals develop in response to chronic emotional exhaustion, allowing them to cope with the emotional demands of their work by distancing themselves from their clients (Maslach & Jackson, 1981; Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). However, while this detachment may temporarily protect workers from emotional distress, it can also undermine the therapeutic relationship and the quality of care provided to patients (Kliszcz et al., 2006).

Interestingly, despite the high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, participants in this study reported relatively high levels of personal accomplishment. This finding may reflect the intrinsic rewards associated with helping individuals overcome addiction, a deeply challenging but potentially highly satisfying field of work. Workers in addiction services often report that witnessing patient recovery, even if rare, provides a strong sense of personal efficacy and professional fulfillment. However, it is also possible that the high personal accomplishment scores in this study may reflect a form of cognitive dissonance reduction, where workers compensate for feelings of exhaustion and detachment by emphasizing their professional achievements (Furnham & Walsh, 1991).

4.2. The Role of Anger in Burnout

One of the most significant contributions of this study is the demonstration of the role that anger, particularly trait anger and anger suppression (anger-in), plays in exacerbating burnout. The positive correlation between trait anger and emotional exhaustion aligns with existing research that identifies anger as a maladaptive emotional response that can intensify stress and fatigue (Saini, 2009). Trait anger reflects a stable disposition to experience anger across a variety of situations, and in high-stress environments such as addiction services, this predisposition may lead to chronic emotional arousal, which in turn depletes emotional resources and contributes to exhaustion (Memedovic et al., 2010).

Moreover, the finding that anger-in was a significant predictor of depersonalization provides new insights into the emotional dynamics of burnout in addiction services. Anger suppression has been linked to a range of negative psychological outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and burnout (Kitamura & Hasui, 2006; Koutsimani et al., 2019). When anger is suppressed rather than expressed or processed, it may accumulate over time, leading to emotional disengagement from patients as a means of coping with unresolved frustration and irritation (Harburg et al., 1973). In the context of addiction services, where patients may exhibit challenging behaviors such as relapse or resistance to treatment, the chronic suppression of anger could lead to feelings of helplessness and cynicism, further fueling depersonalization (Bianchi et al., 2015)

The role of anger control, on the other hand, emerged as a protective factor in this study. Participants who reported higher levels of anger control were less likely to experience burnout, particularly in terms of personal accomplishment. This finding supports the broader literature on emotional regulation, which posits that individuals who are able to manage their emotional responses to stress are better equipped to maintain psychological well-being and professional efficacy (John & Gross, 2004). Anger control, in this context, may involve recognizing and addressing sources of frustration in a constructive manner, thereby preventing the accumulation of negative emotions that can contribute to burnout (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009).

4.3. Underlying Mechanisms: Emotional Labor and Coping Strategies

To understand the mechanisms through which anger contributes to burnout, it is important to consider the concept of emotional labor, which refers to the process of managing one’s emotions to meet the demands of a job (Hochschild, 1983). Healthcare professionals, particularly those working in addiction services, are often required to display empathy, patience, and understanding, even in the face of challenging or emotionally charged interactions. This emotional regulation can be particularly taxing when workers are simultaneously experiencing high levels of anger, which they may feel compelled to suppress in order to maintain a professional demeanor (Zapf, 2002).

The emotional labor involved in addiction treatment is further complicated by the chronic nature of substance use disorders and the frequent relapses that characterize recovery (Morse et al., 2012). When patients relapse, healthcare workers may experience feelings of frustration or helplessness, which, if not adequately addressed, can contribute to the development of burnout (Leiter, Bakker, & Maslach, 2014). The suppression of anger in these situations, as indicated by the high anger-in scores in this study, may reflect a coping strategy aimed at maintaining professional composure, but over time, it can lead to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Brotheridge & Lee, 2003).

Previous research has identified several coping strategies that may mitigate the impact of emotional labor and anger on burnout. For example, problem-focused coping, which involves taking action to address the sources of stress, has been shown to reduce burnout by enabling individuals to feel more in control of their work environment (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). In contrast, emotion-focused coping, such as the suppression of anger, is associated with higher levels of burnout, as it does not address the underlying sources of emotional distress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). These findings suggest that interventions aimed at improving emotional regulation and promoting adaptive coping strategies may be effective in reducing burnout among SERD operators.

4.4. Implications for Interventions and Workplace Policies

The results of this study have several important implications for the development of interventions and policies aimed at reducing burnout and promoting emotional well-being among addiction service workers. Given the strong relationship between anger and burnout, particularly in the dimensions of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, interventions that focus on emotional regulation and anger management are likely to be beneficial. Programs such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), which have been shown to improve emotional regulation and reduce burnout in healthcare workers, could be particularly effective in helping SERD operators manage the emotional demands of their work (Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Irving et al., 2009).

In addition, workplace policies that promote organizational support and reduce the systemic stressors that contribute to burnout should be prioritized. For example, reducing caseloads, providing opportunities for professional development, and fostering a supportive organizational culture have all been identified as key factors in preventing burnout (Shanafelt et al., 2017). Providing access to mental health services for staff, including counseling and stress management programs, could also help to alleviate the emotional burden of working in addiction services (West et al., 2018).

Another important consideration is the role of supervision and peer support in mitigating the effects of burnout and anger. Research has shown that healthcare workers who receive regular supervision and have access to peer support are less likely to experience burnout, as these resources provide opportunities for emotional processing and professional reflection (Salyers et al., 2017). Creating spaces where SERD operators can discuss their emotional experiences, including feelings of frustration and anger, without fear of judgment or professional repercussions, may help to reduce the tendency to suppress negative emotions and promote healthier emotional regulation (Maslach et al., 2001).

Finally, preventive measures should be implemented at the organizational level to reduce the risk of burnout before it becomes entrenched. This may involve regular assessments of staff well-being, early identification of burnout symptoms, and the development of tailored interventions for at-risk employees (Leiter & Maslach, 2009). By taking a proactive approach to burnout prevention, organizations can not only improve the mental health of their staff but also enhance the quality of care provided to patients.

5. Conclusions

The present study contributes valuable insights into the prevalence and impact of burnout and anger among addiction service workers (SERD operators) in Calabria and Sicily. By exploring the relationship between these two psychological constructs, the study provides evidence that trait anger, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization are deeply intertwined. The findings emphasize the urgent need for interventions that not only address burnout but also target emotional regulation, particularly the management of anger. This conclusion aims to synthesize the main findings of the research, discuss its broader implications for practice and policy, and suggest future directions for research.

5.1. Key Findings and Their Implications

One of the most significant findings of the study is the high level of emotional exhaustion reported by SERD operators, which reflects a broader trend observed in healthcare professionals who work in high-stress environments (Innstrand et al., 2009; Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Emotional exhaustion, as the core dimension of burnout, reflects the depletion of emotional resources necessary to perform work effectively and maintain well-being. This finding is particularly concerning given the vital role that SERD operators play in helping individuals struggling with substance use disorders (SUDs), a population that requires consistent, compassionate care.

The high levels of emotional exhaustion observed in this study are likely exacerbated by the emotional labor required in addiction services. Emotional labor, which involves managing one’s emotions to align with professional expectations, can lead to chronic emotional fatigue when sustained over long periods (Hochschild, 1983; Zapf, 2002). The emotional toll of dealing with relapses, patient resistance, and the stigma associated with addiction may make SERD operators particularly vulnerable to burnout (Lasalvia et al., 2009; Portoghese et al., 2014). Emotional exhaustion not only affects the well-being of the operators themselves but may also compromise the quality of care they are able to provide to their clients (Greenglass et al., 1990; Acker, 2004).

Another key finding is the relationship between anger and burnout. The study demonstrates that trait anger—a personality characteristic reflecting the tendency to experience anger across different situations—is strongly correlated with emotional exhaustion. This is consistent with existing literature that identifies chronic anger as a risk factor for stress-related health issues, including burnout (Suls & Bunde, 2005; Alarcon et al., 2009). In the context of addiction services, where workers are often confronted with emotionally charged situations, trait anger may exacerbate feelings of frustration and helplessness, leading to increased emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Brondolo et al., 1999; Bianchi et al., 2015).

Importantly, the study also highlights the role of anger suppression (anger-in) in contributing to depersonalization, a key dimension of burnout characterized by emotional detachment and cynicism toward clients. Suppressed anger can accumulate over time, leading to emotional disengagement from patients as a way of coping with unresolved frustration. This finding aligns with the emotional suppression literature, which posits that the suppression of negative emotions can lead to emotional numbness and a reduced capacity for empathy (Harburg et al., 1973; Gross & John, 2003). In a field like addiction services, where empathy and emotional connection are crucial for effective treatment, depersonalization can severely undermine the therapeutic relationship (Kliszcz et al., 2006).

Conversely, anger control—the ability to regulate and manage anger—was found to be a protective factor against burnout, particularly in maintaining a sense of personal accomplishment. This supports previous research that underscores the importance of emotional regulation in mitigating the negative effects of stress and burnout (John & Gross, 2004). By developing better anger management strategies, SERD operators can reduce the emotional toll of their work and sustain their sense of efficacy and achievement in their roles.

5.2. Practical Implications for Interventions

The findings of this study have important implications for the development of targeted interventions aimed at reducing burnout and improving emotional regulation among addiction service workers. Based on the study’s results, several recommendations can be made for both individual-level interventions and organizational policies.

5.2.1. Emotional Regulation Training

Given the significant role of anger in the development of burnout, one of the most effective interventions could be the implementation of emotional regulation training programs. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) are two approaches that have been shown to improve emotional regulation and reduce burnout in healthcare professionals (Shapiro et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2011). These programs can help SERD operators develop greater awareness of their emotional responses, including anger, and provide them with tools to manage these emotions more effectively. By learning how to regulate their anger and other negative emotions, operators may be better equipped to cope with the emotional demands of their work without experiencing the harmful effects of burnout.

5.2.2. Anger Management Programs

In addition to broader emotional regulation training, specific anger management programs could be implemented as part of continuing professional development for SERD operators. These programs could focus on helping workers identify the sources of their anger, develop healthy strategies for expressing anger, and improve their ability to control anger in high-stress situations. Research suggests that anger management interventions can lead to significant reductions in anger expression and improvements in emotional well-being (Deffenbacher et al., 2002). By addressing the role of anger in burnout, such interventions could reduce the emotional toll of addiction work and improve the long-term sustainability of professionals in this field.

5.2.3. Organizational Support and Resources

Beyond individual interventions, organizations must also play a key role in preventing burnout and supporting emotional regulation among their staff. Organizational culture and the availability of resources can significantly influence the well-being of healthcare workers (Shanafelt et al., 2017). By fostering a supportive work environment, providing access to mental health services, and ensuring manageable workloads, organizations can reduce the systemic stressors that contribute to emotional exhaustion and burnout. For example, regular supervision and peer support groups could provide SERD operators with opportunities to process their emotions in a safe and supportive space, reducing the likelihood of anger suppression and emotional disengagement (Salyers et al., 2017).

Moreover, workplace interventions that promote work-life balance, such as flexible scheduling and opportunities for professional growth, have been shown to reduce burnout and improve job satisfaction (West et al., 2018). By investing in the well-being of their staff, organizations can improve both the mental health of their employees and the quality of care provided to clients.

5.3. Policy Implications

The results of this study also have important implications for public health policy, particularly in the context of addiction treatment services. Addressing burnout among addiction professionals is critical for ensuring the sustainability and effectiveness of SUD treatment programs. Policymakers should consider implementing national guidelines for burnout prevention and emotional regulation training in addiction services. This could include funding for mental health support programs, mandatory emotional regulation training for healthcare workers, and organizational audits to assess burnout risk factors in addiction services (Ahola et al., 2005; SAMHSA, 2021).

In addition, the development of evidence-based interventions to address burnout in addiction services should be a priority for healthcare policy. By supporting research on the most effective strategies for reducing burnout and promoting emotional regulation, policymakers can help ensure that addiction services are staffed by professionals who are emotionally resilient and capable of providing high-quality care (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

5.4. Limitations of the Study

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between burnout and anger among SERD operators, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to draw causal conclusions about the relationships between variables. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether anger directly contributes to burnout over time or whether other factors, such as organizational support or personal coping strategies, moderate this relationship (Zapf et al., 1996). Future research could also explore how interventions targeting anger and emotional regulation influence burnout levels over time.

Second, the study’s sample was limited to SERD operators in two regions of Italy, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other settings. Although the challenges faced by addiction service workers in Calabria and Sicily are likely to be shared by similar professionals in other regions, further research is needed to confirm these findings in different cultural and organizational contexts (Schaufeli, Leiter, & Maslach, 2009). Expanding the research to other regions or countries would provide a broader understanding of how anger and burnout manifest in addiction services across different healthcare systems.

Finally, the study focused primarily on anger as a key emotional factor in burnout. However, other emotions, such as anxiety, guilt, and sadness, may also play important roles in the development of burnout among healthcare professionals (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015). Future studies should adopt a more comprehensive approach to emotional regulation by examining the interplay between different emotions and burnout outcomes.

5.5. Future Research Directions

The findings of this study open up several avenues for future research. Longitudinal studies that track the development of burnout and emotional regulation over time could provide more definitive insights into the causal relationships between these variables. Additionally, research exploring the effectiveness of different interventions, such as anger management programs and mindfulness-based stress reduction, would be valuable in identifying the most effective strategies for reducing burnout in addiction services.

Moreover, future research should investigate the role of organizational factors in burnout and emotional regulation. For example, studies could explore how different types of supervision, workplace culture, and job demands influence burnout levels and emotional regulation among addiction service workers (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). By identifying the specific organizational factors that contribute to burnout, researchers can help inform the development of workplace interventions that address these challenges.

Finally, research exploring the impact of burnout and emotional regulation on patient outcomes would provide valuable insights into the broader implications of these issues for healthcare quality. Understanding how the emotional well-being of addiction service workers affects the recovery and

well-being of their clients could help policymakers and organizations prioritize the mental health of healthcare professionals as part of a comprehensive strategy for improving addiction treatment outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F. and R.V.M.; methodology, R.V.M.; software, P.F.; validation, R.V.M.; formal analysis, R.V.M.; investigation, P.F.; resources, P.F.; data curation, P.F.; writing—original draft preparation, P.F..; writing—review and editing, R.V.M.; visualization, R.V.M.; supervision, R.V.M.; project administration, R.V.M.; funding acquisition, P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the type of study it was not necessary to ask for an ethical opinion from any committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. Due to ethical restrictions, individual-level data cannot be publicly shared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the SERD operators who participated in the study and the addiction service centers in Calabria and Sicily for their collaboration. Special thanks to [Institution/Colleague’s Name] for providing administrative and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acker, G. M. (2004). Role conflict and ambiguity: Do they predict burnout among mental health service providers? Social Work in Mental Health, 2(1), 63-78. [CrossRef]

- Ahola, K. , Toppinen-Tanner, S., Hakanen, J., Koskinen, A., & Väänänen, A. (2005). Occupational burnout and depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 88(1), 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G. , Eschleman, K. J., & Bowling, N. A. (2009). Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 23(3), 244–263. [CrossRef]

- Averill, J. R. (1983). Studies on anger and aggression: Implications for theories of emotion. American Psychologist, 38(11), 1145–1160. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B. , & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: state of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

- Bianchi, R. , Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2015). Burnout-depression overlap: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 36, 28-41. [CrossRef]

- Brondolo, E., Rieppi, R., Erickson, S. A., & Shapiro, P. A. (1999). Hostility, interpersonal interactions, and ambulatory blood pressure. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(2), 191–204. [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C. M., & Lee, R. T. (2003). Development and validation of the Emotional Labour Scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(3), 365-379. [CrossRef]

- Bride, B. E. , Jones, J. L., & MacMaster, S. A. (2007). Correlates of secondary traumatic stress in child protective services workers. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 4(3-4), 69–80. [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S. , Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S. , & Harmon-Jones, E. (2009). Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 183–204. [CrossRef]

- Cordes, C. L., & Dougherty, T. W. (1993). A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 621-656. [CrossRef]

- Deffenbacher, J. L., Oetting, E. R., & DiGiuseppe, R. A. (2002). Principles of empirically supported interventions applied to anger management. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 9(1), 50-63. [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, T. , & O’Leary, K. D. (2004). Effectiveness of anger treatments for specific anger problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(1), 15-34. [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. , Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [CrossRef]

- Embriaco, N. , Papazian, L., Kentish-Barnes, N., Pochard, F., & Azoulay, E. (2007). Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Current Opinion in Critical Care, 13(5), 482-488. [CrossRef]

- Evans, S. , Pistrang, N., & Billings, J. (2013). Therapist responses to client trauma narratives: Implications for vicarious traumatization, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(1), 23-32. [CrossRef]

- Faragher, E. B. , Cass, M., & Cooper, C. L. (2005). The relationship between job satisfaction and health: A meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(2), 105–112. [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D., Parslow, R., Creamer, M., Allen, N., McHugh, T., & Hopwood, M. (2008). Mechanisms of anger and treatment outcome in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Trauma Stress, 21, 142-149. [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A., & Walsh, J. (1991). Personality and job satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 12(5), 493-512. [CrossRef]

- Gallon, S. , Gabriel, R. M., & Knudsen, J. R. W. (2003). The toughest job you’ll ever love: A Pacific Northwest treatment workforce survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 24(3), 183–196. [CrossRef]

- Greenglass, E. R. , Burke, R. J., & Ondrack, M. (1990). A gender-role perspective of coping and burnout. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 39, 5-27. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. , & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348-362. [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P. (2014). Mindfulness: Awareness informed by an embodied ethic. Mindfulness, 5(2), 212-223. [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. , & Demerouti, E. (2005). The construct validity of an alternative measure of burnout: Investigating the English translation of the Oldenburg burnout inventory. Work & Stress, 19(3), 208-220. [CrossRef]

- Harburg, E. , Erfurt, J. C., Hauenstein, L. S., Chape, C., Schull, W. J., & Schork, M. A. (1973). Socio-ecological stress, suppressed hostility, skin color, and black-white male blood pressure: Detroit. Psychosomatic Medicine, 35(4), 276-296. [CrossRef]

- Hillhouse, J. , Adler, C., & Walters, D. (2010). A simple model of stress, burnout and symptomatology in medical residents: a longitudinal study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 5(1), 63-73. [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press. [CrossRef]

- Innstrand, S. T. , Langballe, E. M., Espnes, G. A., Falkum, E., & Aasland, O. G. (2009). Gender specific perceptions of four dimensions of the work/family interaction. Journal of Career Assessment, 17(4), 402-416. [CrossRef]

- Irving, J. A. , Dobkin, P. L., & Park, J. (2009). Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: A review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 15(2), 61–66. [CrossRef]

- John, O. P. , & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1301–1333. [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, T., & Hasui, C. (2006). Anger feelings and anger expression as a mediator of the effects of witnessing family violence on anxiety and depression in Japanese adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(7), 843-855. [CrossRef]

- Kliszcz, J., Nowicka-Sauer, K., Trzeciak, B., Nowak, P., & Sadowska, A. (2006). Emotional intelligence in physicians. Polish Archives of Internal Medicine, 116(12), 805-810.

- Kokkinos, C. M. (2007). Job stressors, personality, and burnout in primary school teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(1), 229–243. [CrossRef]

- Koutsimani, P. , Montgomery, A., & Georganta, K. (2019). The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 284. [CrossRef]

- Lasalvia, A. , Bonetto, C., Bertani, M., Bissoli, S., Cristofalo, D., Marrella, G., & Ruggeri, M. (2009). Influence of perceived organisational factors on job burnout: Survey of community mental health staff. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(6), 537–544. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. , & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M. P. , & Maslach, C. (2009). Nurse turnover: The mediating role of burnout. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(3), 331-339. [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M. P. , Bakker, A. B., & Maslach, C. (2014). Burnout at work: A psychological perspective. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-84872-228-1.

- Levin, K. A. (2006). Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evidence-Based Dentistry, 7, 24-26. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, C. , King, R., & Chenoweth, L. (2002). Social work, stress and burnout: A review. Journal of Mental Health, 11(3), 255–265. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior 1981, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. , Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Maslach, C. , & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103-111. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. , & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103-111. [CrossRef]

- Mayor, E. (2015). Gender roles and traits in stress and health. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 779. [CrossRef]

- McTernan, W. P. , Dollard, M. F., & LaMontagne, A. D. (2013). Depression in the workplace: An economic cost analysis of depression-related productivity loss attributable to job strain and bullying. Work & Stress, 27(4), 321-338. [CrossRef]

- Memedovic, S., Grisham, J. R., Denson, T. F., & Moulds, M. L. (2010). The effects of trait reappraisal and suppression on anger and blood pressure. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(4), 540-543. [CrossRef]

- Morse, G. , Salyers, M. P., Rollins, A. L., Monroe-DeVita, M., & Pfahler, C. (2012). Burnout in mental health services: A review of the problem and its remediation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(5), 341–352. [CrossRef]

- Piper, W. E. , Joyce, A. S., Rosie, J. S., & Azim, H. F. (1989). Patient anger, trait aggression, and response to short-term group therapy. Psychotherapy, 26(4), 529–535. [CrossRef]

- Poghosyan, L. , Clarke, S. P., Finlayson, M., & Aiken, L. H. (2010). Nurse burnout and quality of care: Cross-national investigation in six countries. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(4), 288-298. [CrossRef]

- Portoghese, I. , Galletta, M., Coppola, R. C., Finco, G., & Campagna, M. (2014). Burnout and workload among health care workers: The moderating role of job control. Safety and Health at Work, 5(3), 152-157. [CrossRef]

- Purvanova, R. K. , & Muros, J. P. (2010). Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 168-185. [CrossRef]

- Saini, M. (2009). A meta-analysis of the psychological treatment of anger: Developing guidelines for evidence-based practice. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 37, 473-488.

- Salyers, M. P., Rollins, A. L., Kelly, A., Lysaker, P. H., & Williams, J. R. (2017). Job satisfaction and burnout among VA and community mental health workers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 255–262. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to study and practice: A critical analysis. Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2009). Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Development International, 14(3), 204-220. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the Job Demands-Resources model: Implications for improving work and health. Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health, 43-68. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S. , Grossman, P., Schwarzer, B., Jena, S., Naumann, J., & Walach, H. (2011). Treating fibromyalgia with mindfulness-based stress reduction: Results from a 3-armed randomized controlled trial. Pain, 152(2), 361-369. [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T. D. , Goh, J., & Sinsky, C. (2017). The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(12), 1826-1832. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S. L. , Astin, J. A., Bishop, S. R., & Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management, 12(2), 164-176. [CrossRef]

- Shoptaw, S. , Stein, J. A., & Rawson, R. A. (2005). Burnout in substance abuse counselors: Impact of environment, attitudes, and clients with HIV. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 29(3), 231-240. [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. , & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S72-S103. [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C. D. (1999). STAXI-2: State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Stewart, W. F., Ricci, J. A., Chee, E., Hahn, S. R., & Morganstein, D. (2003). Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA, 289(23), 3135-3144. [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2021). Addressing Burnout in the Behavioral Health Workforce Through Organizational Strategies. SAMHSA Report. https://www.store.samhsa.

- Suls, J. , & Bunde, J. (2005). Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: The problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychological Bulletin, 131(2), 260–300. [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M. , & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53-55. [CrossRef]

- West, C. P. , Dyrbye, L. N., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2018). Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. Journal of Internal Medicine, 283(6), 516–529. [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. J. , Dunning, D., & Kruger, J. (2010). Being ignorant of one’s ignorance: Trait anger and perception of personal competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(2), 145-162. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D. , Dormann, C., & Frese, M. (1996). Longitudinal studies in organizational stress research: A review of the literature with reference to methodological issues. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(2), 145–169. [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D. (2002). Emotion work and psychological well-being: A review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 237–268. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).