1. Introduction

1.1. Preliminaries

Although there is an extensive literature on studying methods of filtering of random signals, the problem we consider seems to be different from the known ones. The objective of this paper is to formulate and solve this problem under scenarios which relate to a reduction of computation complexity, for the case of large covariance matrices, and an increase in the filtering accuracy.

Let be a set of outcomes in probability space for which is a –algebra of measurable subsets of and is an associated probability measure. Let be a signal of interest and be an observable signal.. Here is the space of square-integrable functions defined on with values in , i.e., such that

Further, let us write

where

, for

. We assume without loss of generality that all random vectors are of the zero mean. Let us denote

where

is the covariance matrix formed from

and

.

Let filter F be represented by where . Note that each matrix defines a bounded linear transformation . It is customary to write M rather then since , for each .

The known problem of finding optimal filter

F is formulated as follows. Given large covariance matrices

and

, find

M that solves

The minimal Frobenius norm solution to (

2) is given by (see, for example, [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5])

where

is the Moor-Penrose pseudo-inverse of

.

1.2. Motivations

In

3,

M contains

entries. In other words, the filter defined by

3 contains

parameters to optimize the associated accuracy.

Motivation 1: Increase in accuracy. Since

M in

3 is optimal there is no other linear filter that can provide a better associated accuracy. At the same time, it may happen that the accuracy is not satisfactory. Then a logical way to increase the accuracy is an increase in the number of parameters to optimize. Since

m is fixed then only

n can be varied;

n can be increased to, say,

q where

, if

is replaced with another vector

which is unknown. In this case, we need to determine both

M and

. In particular,

can be represented as

where, for

and

. Then the associated filter

is represented by the equation

where, for

. We call

p the degree of filter .

Therefore, the

preliminary statement of the problem considered here and in [

6] is as follows. Given

and

, find

and

that solve

Note, since

and

are given then, for

,

and

are known as blocks of

and

.

Motivation 2: Decrease in computational load. In

2 and

3, dimensions of

and

,

m and

n, respectively, can be very large. In a number of important applied problems, such as those in biology, ecology, finance, sociology and medicine (see e.g., [

7,

8]),

and greater. For example, measurements of gene expression can contain tens of hundreds of samples. Each sample can contain tens of thousands of genes. As a result, in such cases, associated covariance matrices matrices in

3 are very large. Further, in (

4) and (

5), dimension

of

might be of the same order as that of observable signal

. For instance, one of

can be equal to

. Based on

2–(

5), it is natural to predict that a solution of problem (

5) contains

pseudo-inverse

and

pseudo-inverse

. It is indeed so, as shown in

Section 4.1.6 and [

6]. Matrices

and

are usually larger than

. Then computation of a large pseudo-inverse matrix leads to a quite slow computing procedure up to the cases when the computer runs out of computer memory. In particular, the associated well-known phenomenon of the “curse of dimensionality” [

9] states that many problems become exponentially difficult in high dimensions.

Of course, in the case of high dimensional signals, some well known dimensionality reduction techniques can be used (as those, for example, in [

2,

3,

5]) as an intermediate step for the filtering. At the same time, those techniques also involve large pseudo-inverse covariance matrices of the same size as that in

3. Additionally, in applying the dimensionality reduction procedure, intrinsic associated errors appear. The errors may involve, in particular, an undesirable distortion of the data. Thus, an application of the dimensionality reduction techniques to the problem under consideration does not allow us to avoid a computation of large pseudo-inverse covariance matrices. Therefore, we wish to develop techniques that reduce computation of large pseudo-inverses

and

without involving any additional associated error.

The following example illustrates Motivation 2. Simulations in this example and also in 2 of

Section 4.1.7 were run on a Dell Latitude 7400 Business Laptop (manufactured in 2020).

Example 1.

Let be a matrix whose entries are normally distributed with mean 0 and variance 1. In Table 1, we provide the time (in seconds) needed forMatlabto compute matrix for different values of q.

We observe that computation of, e.g., pseudo-inverse matrix requires 63 seconds while computation of the five pseudo-inverse matrices of sizes requires about seconds. Thus, a procedure that would allow us to reduce the computation of to a computation of, say, five pseudo-inverse matrices of sizes would be faster. At the same time, such a procedure would additionally contain associated matrix multiplications which are time consuming as well. This observation is further elaborated in Section 4.1.2 and 2 of Section 4.1.7.

2. Statement of the Problem

The solution of the problem in (

5) is divided into two parts. In this paper, we consider the first part of the solution. It mainly concerns a technique for the decrease in a computational load associated with computation of

. The second part of the solution of problem (

5) is considered in [

6]. It represents an extension of the technique considered here to the solution of the original problem in (

5). More precisely, here, we consider

In terms of notation (

4), the known minimal Frobenius norm solution of (

6) is given by (see, e.g., [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5])

As mentioned in

Section 1.2, in (

7) (and in (

8) below),

matrix

might be very large. Then the pseudo-inverse

may be difficult to compute. In this case, formula in (

7) is not useful in practice.

Therefore, the problem is as follows. Given

large and

, find a computational procedure for solving (

6) which significantly decreases the computational complexity for the

evaluation compared to that needed by the filter represented by (

7).

While problem (

6) arises in the solution provided in [

6] it is also important in its own right. In particular, if

where, for

,

and

, then (

6) represents the problem of finding the optimal multi-input multi-output (MIMO) filter. In this case,

and

, for

, are an input signal and output signal, respectively.

The problem in (

6) can also be interpreted as the system identification problem [

10,

11,

12,

13]. In this case,

are the inputs of the system,

is the input-output map of the system, and

is the system output. For example, in environmental monitoring,

may represent random data coming from nodes measuring temperature, light or pressure variations, and

may represent a random signal obtained after a merging of the received data in order to estimate required data parameters within a prescribed accuracy. Similar scenarios occur, e.g., in target localization and tracking [

14].

As mentioned above, in all problems considered in this paper, covariance matrices are assumed to be known. This assumption is a well-known and significant limitation in problems dealing with the optimal filtering of random signals. See [

15,

16,

17,

18] in this regard. The covariances can be estimated in various ways and particular techniques are given in many papers. We cite [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] as the examples. Estimation of covariance matrices is an important problem which is not considered in this paper.

3. Contribution and Novelty

The main conceptual novelty of the approach developed in this paper is in the technique that allows us to decrease the computational load needed for the numerical realization of the proposed filter. The procedure is based on the reduction of a large

matrix to a collection of smaller matrices. It is done so that the filter equation with large matrices is equivalently represented by the set of equations with smaller matrices. As a result, as shown in

Section 4.1.7, the proposed

p-th degree filter requires computation of

p pseudo-inverse matrices with sizes smaller that the size of the large matrix

. In this regard, see

Section 4.1.2, and 1 and 2, for more details. The associated

Matlab code is given in

Section 4.1.7.

In 2, 3 and 4, we also show that the accuracy of the proposed filter increases with increases in the degree of the filter. Details are provided in

Section 4.1 and more specifically, in

Section 4.1.2. In particular, the algorithm for the optimal determination of

is given in

Section 4.1.7. Note that the algorithm is easy to implement numerically. The error analysis associated with the filter under consideration is provided in

Section 4.1.3,

Section 4.1.5 and

Section 4.1.8.

Remark 1. Note that for every outcome , realizations and of signals and , respectively, occur with certain probabilities. Thus, random signals , for and are associated with infinite sets of realizations and , respectively. For different ω, the values , for and are, in general, different, and in many cases will span the entire spaces and , respectively. Therefore, for each and , for , filter given by (4) can be interpreted as map where probabilities are assigned to each column of and . Importantly, the filter is invariant with respect to outcome , and therefore, is the same for all and with different outcomes .

4. Solution of the Problem

We wish that in (

5) and (

6),

would never been the zero vector. To this end, we need to extend the known definition of the linear independence of vectors as follows.

Let be some matrices. For , let be a null space of matrix .

A linear combination in the generalized sense of vectors

is a vector

We say that the linear combination in generalized sense is non-trivial if , for at least one of Note that if where is the zero matrix, then it is still, of course, possible that . Therefore, condition is more general than condition .

Definition 1.

Random vectors are called linearly independent in the generalized sense

if there is no non-trivial linear combination in the generalized sense of these vectors equal to the zero vector; in other words, if

for almost all , implies that , for each , and almost all .

All random vectors considered below are assumed to be linearly independent in the generalized sense.

4.1. Solution of Problem in (6)

In (

7), matrix

M is the minimum Frobenius norm solution of the equation

Here, we exploit the specific structure of the original system (

8) to develop a special block elimination procedure that allows us to reduce the original system of equations (

8) to a collection of independent smaller subsystems. Their solution implies less computational load than that needed for (

7).

To this end, let us represent

and

in blocked forms as follows:

where

and

, for

. Then (

8) implies

Thus, the solution of the problem in (

8) is equivalent to the solution of equation (

10).

We provide a specific solution of equation (

10) in the following way. First, in

Section 4.1.1, a generic basis for the solution is given. In

Section 4.1.4, the solution of equation (

10) is considered for

. This is a preliminary step for the solution of equation (

10) for an arbitrary

p which is provided in

Section 4.1.6.

4.1.1. Generic Basis for the Solution of Problem (8): Case in (10). Second Degree Filter

To provide a generic basis for the solution of equation (

10), let us consider the case

in (

4) and (

6), i.e., the second degree filter. Then (

10) becomes

Recall, it has been shown in [

4] that for any random vectors

g and

h,

Lemma 1.

Let and satisfy equation (11). Then (11) decomposes into equations

Proof. Let us denote

. Then

and

where by (

13),

Thus, (

11) is represented as

which implies

On the basis of (

17), we see that (

8), for

, reduces to the equation

Remark 2.

The above proof is based on equation (15) which implies the equivalence of equations (11) and 14. In turn, (1) allows us to equivalently obtain 14 as follows. Let us multiply (11) from the right by . Then

Then 14 follows from (20).

Theorem 1.

For the minimal Frobenius norm solution of problem (8) is represented by

Proof. By (1), matrices

and

that solve (

11) satisfy the equations in

14. By [

2,

3,

17,

18], their minimal Frobenius norm solutions are given by (

21).

▪

It follows from (

21) that the second degree filter requires computation of two pseudo-inverse matrices,

and

, of sizes that are smaller than the size of

(if, of course,

and

).

4.1.2. Decrease in Computational Load

Here, we wish to compare the computational load needed for a numerical realization of the second degree filter given, for

, by (

4) and (

21), and that of the filter represented by (

7).

By [

25] (p. 254), the product of

and

matrices requires, for large

and

q,

flops. For large

q, the Golub-Reinsch SVD used for computation of the

matrix pseudo-inverse requires

flops (see [

25], p. 254).

In (

12), for

, the evaluation of

implies the evaluation of

, matrix multiplications in

and matrix subtraction. These operations require

flops,

flops and

flops, respectively. Similarly, computation of

requires

flops. In (

21), computation of

and

imply

flops and

flops, respectively.

Let us denote by

a number of flops required to compute an operation

A. In total, the second degree filter requires

flops where

Thus, the number of flops needed for the numerical realization of the second degree filter is equal to .

The computational load required by the filter given by (

7) is

flops. It is customary to choose

. In this case, clearly,

. In particular, if

then the latter inequality becomes

That is, for sufficiently large

m and

q, the proposed second degree filter requires, roughly, up to

times less flops than that by the filter given by (

7). In simulations by

Matlab provided in 2 below, the second degree filter takes about two times less seconds than the filter given by (

7). A command that would allow us to compute a number of flops is not available in

Matlab.

In the following

Section 4.1.4 and

Section 4.1.6, the procedure described in

Section 4.1.1 is extended to the case of the filter of higher degrees. For given

q, this will imply, obviously, smaller sizes of blocks of matrices

and

than those for the second degree filter, and as a result, a further decrease in the associated computational load.

4.1.3. Error Associated with the Second Degree Filter Determined by (4)

Now, we wish to show that the error associated with the second degree filter determined, for

, by (

4) and (

21) is less than the error associated with the filter determined by

3.

The Frobenius norm of matrix M is denoted by .

Theorem 2.

Let and be such that

where and . Then

Proof. It is known (see, for example, [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]) that, for

M determined by

3, and for

and

determined by (

21),

where

and, bearing in mind (2),

. Therefore, by (

21),

As a result, (

24) follows from (

23), (

27) and (

28).

▪

Remark 3. The condition in (23) can practically be satisfied by, in particular, a suitable choice of and , and/or their dimensions. The following 1 demonstrates such a particular choice of .

Corollary 1. Let and be a nonzero signal. Then (24) is always true.

Proof. The proof follows directly from (

23), (

27) and (

28).

▪

In general, the proposed solution of equation ((

10)) is based on a combination of (1) and (2) with the extension of the idea of Gaussian elimination [

25] to the case of matrices with specific blocks

and

. This allows us to build the special procedure considered below in

Section 4.1.4 and

Section 4.1.6.

4.1.4. Solution of Equation (10) for

To clarify the solution device of equation (

10) for an arbitrary

p, let us now consider a particular case with

. The solution is based on the development of the procedure represented by (

19) and (

20).

For

, equation (

10) is as follows:

First, consider a reduction of (

29) to the equation with

the block-lower triangular matrix.

Step 1. By (

13), for

,

. Define

Now, in (

29), for

and

, update block-matrices

and

to

and

, respectively, so that

and

where

, for

and

, and

, for

. Note that

by (

13).

Step 2. Set

By (

13),

. Taking the latter into account, update block-matrices

and

in the LHS of (

31) and

31, for

and

, so that

and

where

and

.

As a result, we finally obtain the updated matrix equation with the block-lower triangular matrix

Solution of equation (34). Using a back substitution, equation (

34) is represented by the three equations as follows:

where

and

are the original blocks in (

29).

It follows from (

35)–(

37) that the solution of equation (

10), for

, is represented by the minimal Frobenius norm solutions to the problems

where

and

are solutions to the problems in (

38) and (

39), respectively. Matrices

, for

, that solve (

38)-(

40) are as follows:

Thus, the third degree filter requires computation of three pseudo-inverse matrices, , and .

4.1.5. Error Associated with the Third Degree Filter Determined by (41)–(43)

We wish to show that the error associated with the filter determined by (

41)–(

43), is less than that associated with the filter determined by

3,

.

To this end, let us denote

where

. As before,

and

.

Theorem 3.

Let , and be such that

Proof. We have

and, bearing in mind an obvious extension of Remark (2), for

,

. Therefore, by ((

41))–((

43)),

Thus, (

45)–(

46) follows from

in (

22), (

47) and (

48).

▪

Corollary 2. If , and at least one of or is a nonzero vector then (46) is always true.

Proof. The proof follows from (

45), (

48) and (

28).

▪

4.1.6. Solution of Equation (10) for Arbitrary p

Here, we extend the procedure considered in (

Section 4.1.4) to the case of an arbitrary

p. First, we reduce the equation in (

10) to an equation with

the block-lower triangular matrix. We do it by the following steps where each step is justified by an obvious extension of (1).

Step 1. First, in (

10), for

and

, we wish to update blocks

and

to

and

, respectively. To this end, define

Bearing in mind that by (

13),

, for

, we obtain

and

where, for

and

,

and

Step 2. Now we wish to update blocks

and

, for

and

, of the matrices in the LHS of (

49) and (

50), respectively.

Set

Because by (

13),

, for

, we have

and

where, for

and

,

and

We continue this updating procedure up to the final Step

. In Step

, the following matrices are obtained:

and

Step . By (

13),

In

57 and

58, we now update only two blocks

and

, and the single block

. To this end, define

and obtain

and

where

and

As a result, on the basis of (

59)–(

62), equation (

10) is reduced to the equation with the the block-lower triangular matrix as follows

where

and

4.1.7. Solution of Equation (10)

Using a back substitution, (

63) is represented by

p equations as follows:

Therefore, the solution of equation (

10) is represented by solutions to the problems

In (

65)–(

67),

are solutions to the problems in (

64)–(

66), respectively. On the basis of [

26], the minimal Frobenius norm solutions

to (

64)–(

67) are given by

Thus, the p-th degree filter requires computation of p pseudo-inverse matrices, , , .

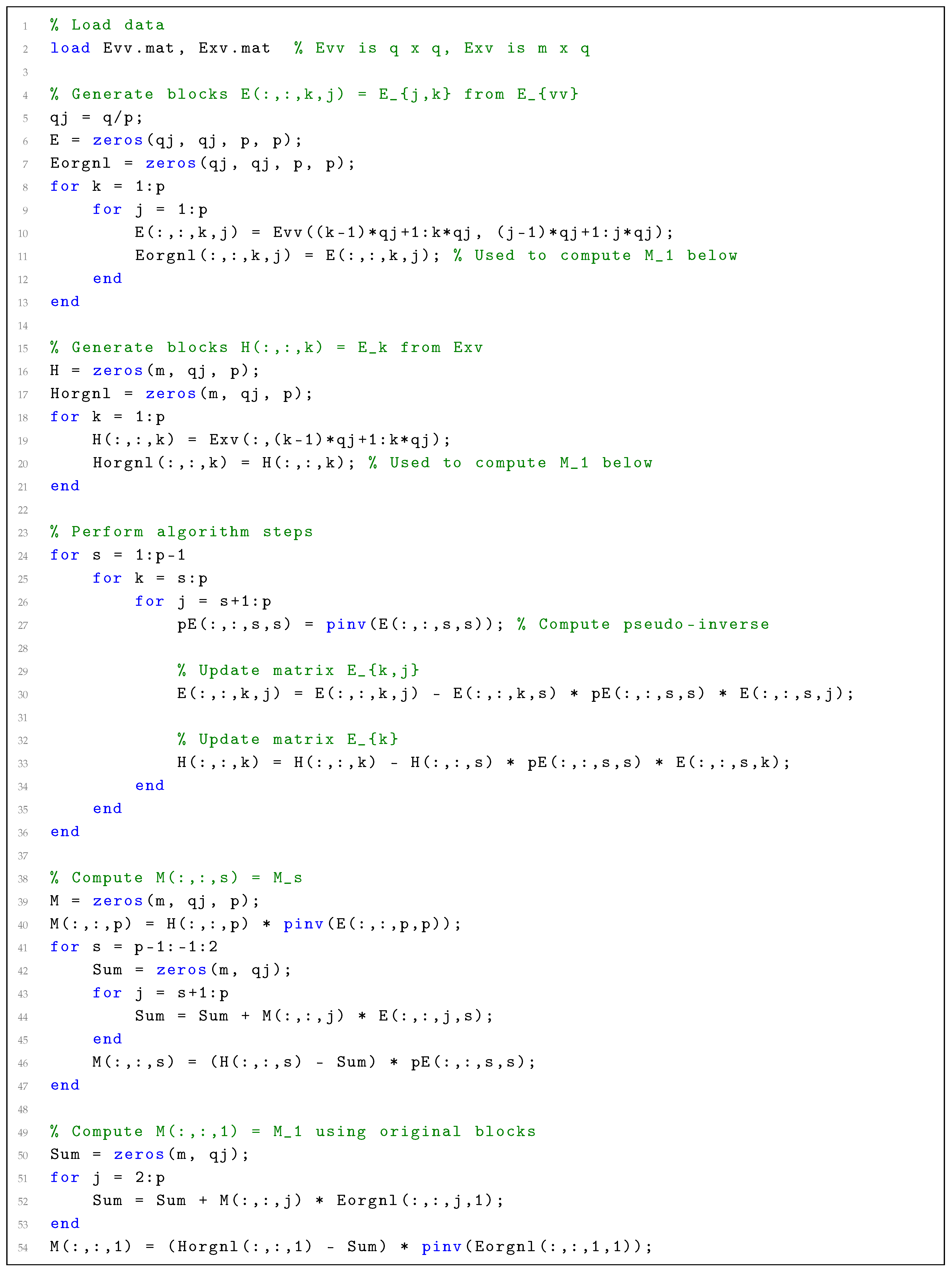

The algorithm that follows is based on formulas (

51), (

52), (

55), (

56), (

61), (

62) and (

68)–(

71).

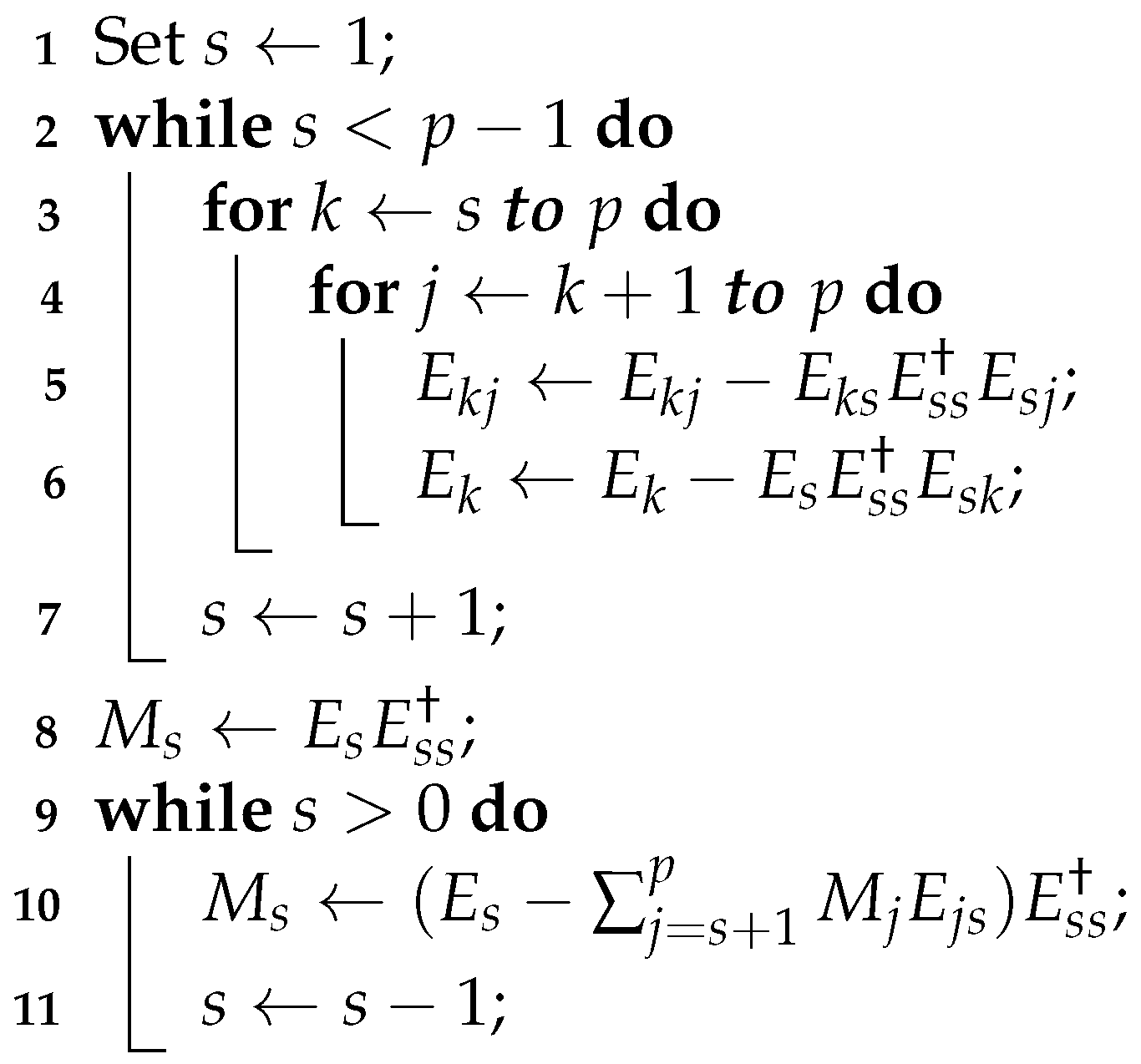

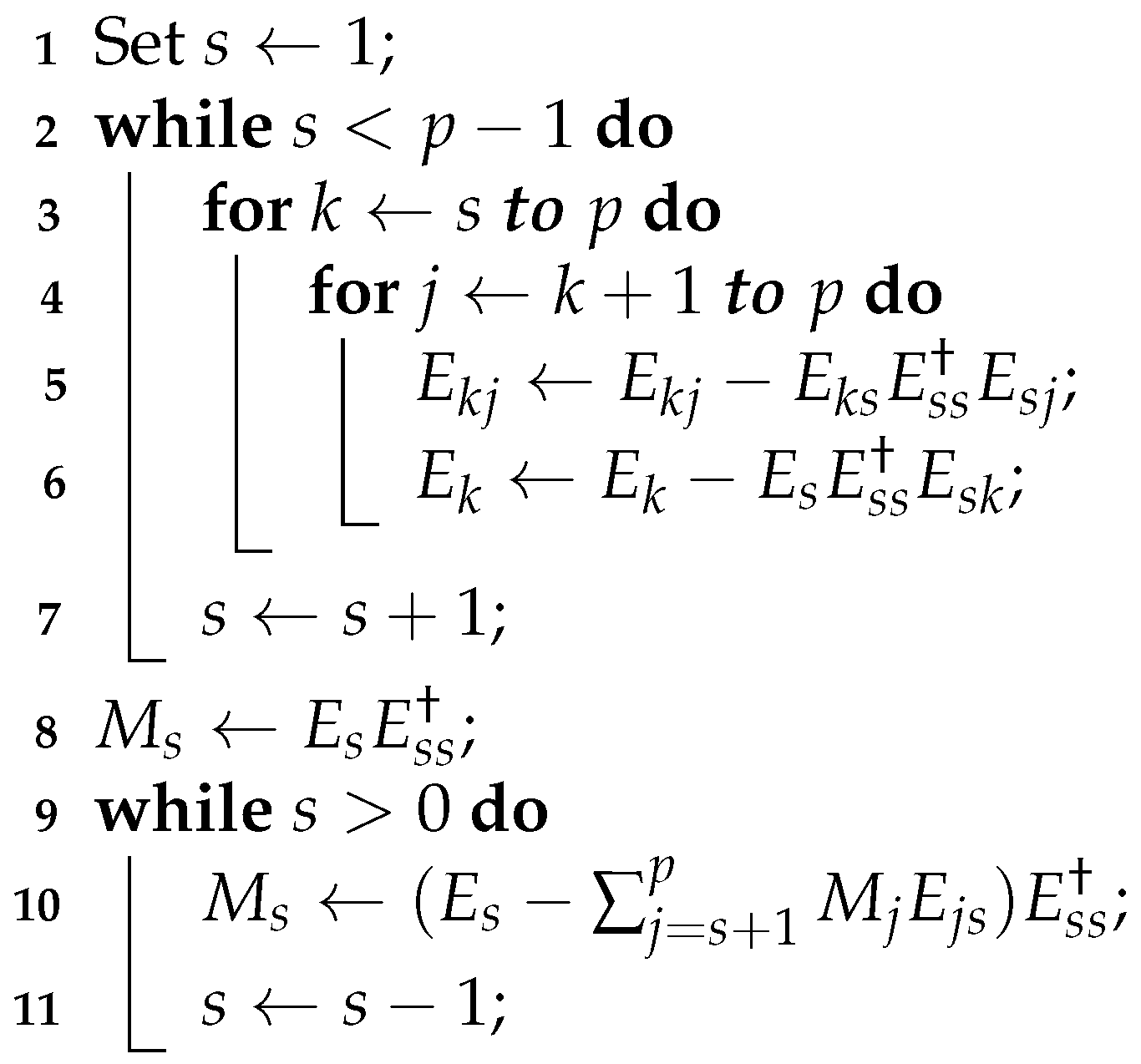

|

Algorithm 1: Solution of equation (10) |

|

Input: p, for , and for .

Output: for .

|

Note that the algorithm is quite simple. Its output is constructed from the successive computation of matrices and .

In line 2, the algorithm updates matrices

and

similar to those for the particular cases given by (

51), (

52), (

55), (

56), (

61), (

62).

In line 5, matrix

is calculated as in (

68).

In line 7, matrices

are calculated as in (

69)–(

71).

Importantly,

is the

matrix with

, therefore, it requires less computation than

pseudo-inverse

in (

7).

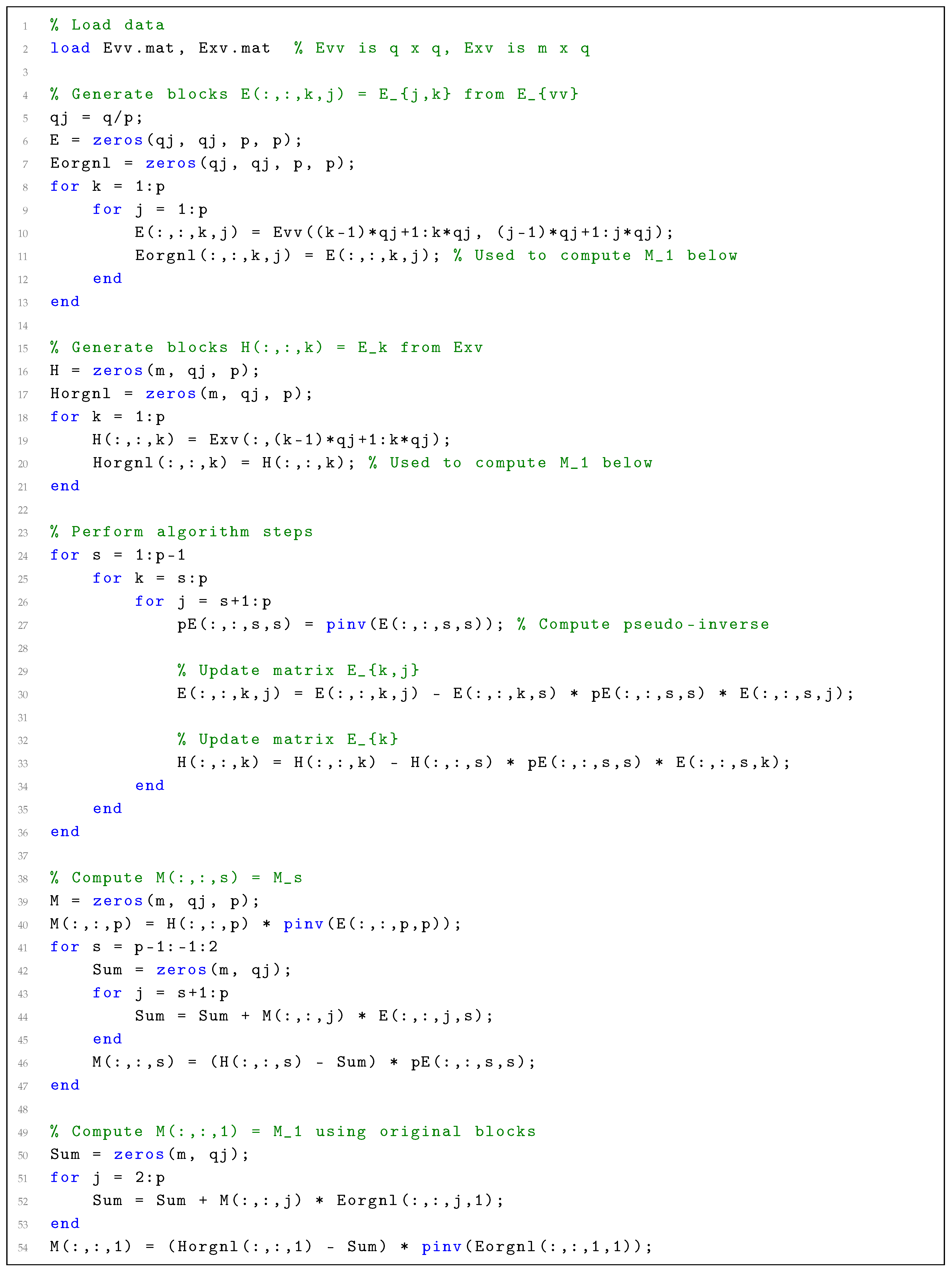

In the Matlab code below, are as above and Evv.mat, Exv.mat are files containing matrices and , respectively.

Listing 1. MATLAB Code for Solving Equation (10). |

|

Example 2.

Here, we wish to numerically illustrate the above algorithm andMatlabcode. To this end, in equation (10), we consider matrices and whose entries are normally distributed with mean 0 and variance 1. We choose , , and , for .

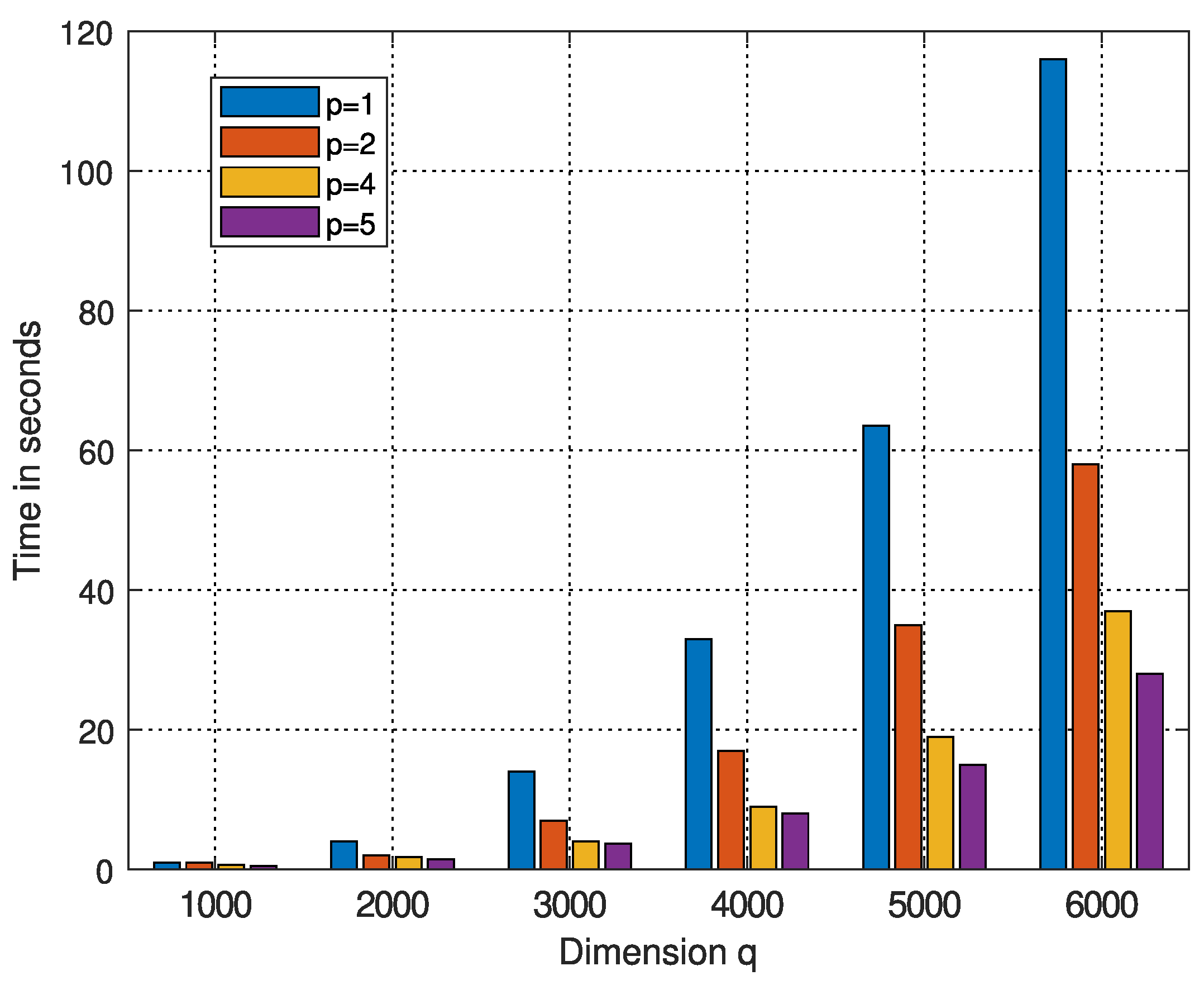

In Table 2 and Figure 1, for , diagrams of the time needed by the above algorithm versus different values of dimension q are presented. Recall, the simulations carry out by the Dell Latitude 7400 Business Laptop (manufactured in 2020). The time decreases with the increase in p. In other words, the computational load needed for the numerical realization of the proposed p-th degree filer decreases with the increase in degree p. Note that the proposed p-th degree filter requires computation of p pseudo-inverse matrices and also matrix multiplications determined by the above algorithm. In particular, for and the proposed filter is around four times faster than the filter defined by (7).

4.1.8. The Error Associated with the Filter Represented by (4) and (68)–(71)

Let us denote by

the error associated with the filter determined by (

4) and (

68)–(

71). We wish to analyze the error.

Theorem 4.

The error associated with the filter determined by (4) and (68)–(71) is given by

Let be a nonzero vector. Then the error decreases if the degree of the proposed filter p increases, i.e.,

In particular, if are such that

then is less than ϵ, the error associated with the filter given by (3),

Proof. We have

where similar to the proofs of (2) and (3),

. Note that, as before,

and

. Therefore, by (

68)–(

71),

As a result, (

77) and (

78) imply (

73). In turn, (

73) implies (

74). Inequalities (

23) and (

76) follow from (

28), (

77) and (

78).

▪

Remark 4. Of course, in practice, the condition in (23) can easily be satisfied by a variation of the dimensions of vectors and/or by their choice. The following (3) illustrates this observation.

Corollary 3. If and at least one of is not the zero vector then (76) is always true.

Proof. The proof follows directly from (

28) and (

73).

▪

5. Conclusion

In a number of important applications, such as those in biology and medicine, associated random signals are high-dimensional. Therefore, covariance matrices formed from those signals are high-dimensional as well. Large matrices also appear because of the filter structure. As a result, the numerical realization of the filter that processes high-dimensional signals might be very time consuming, and in some cases run out of computer memory. In this paper, we have presented a method of optimal filter determination which targets the case of high-dimensional random signals. In particular, we have developed a procedure that significantly decreases the computational load needed to numerically realize the filter (see (

Section 4.1.7) and (2)). The procedure is based on the reduction of the filter equation with large matrices to its equivalent representation by the set of equations with smaller matrices. The associated algorithm has been provided. The algorithm is easy to implement numerically. We have also shown that the filter accuracy is improved with an increase in filter degree, i.e. in the number of filter parameters (see (4)).

The provided results demonstrate that in high-dimensional random signal settings, a number of existing applications may benefit from using the proposed technique. The

Matlab code is given in (

Section 4.1.7). In [

6], the technique provided here is extended to the case of filtering which is optimal with respect to minimization of both matrices

and random vectors

.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H, A.T. and P.S.Q.; methodology, P.H. and A.T.; software, A.T. and P.S.Q; validation, P.H. and A.T.; writing – original draft, A.T.; visualization, P.S.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Extensión from Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica (Research #1440054).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fomin, V.N.; Ruzhansky, M.V. Abstract Optimal Linear Filtering. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization 2000, 38, 1334–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Nikpour, M.; Stoica, P. Optimal reduced-rank estimation and filtering. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2001, 49, 457–469. [Google Scholar]

- Brillinger, D.R. Time Series: Data Analysis and Theory; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Torokhti, A.; Howlett, P. An Optimal Filter of the Second Order. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2001, 49, 1044–048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, L. The SVD and reduced rank signal processing. Signal Processing 1991, 25, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, P.; Torokhti, A.; Soto-Quiros, P. Decrease in computational load and increase in accuracy for filtering of random signals. Part II: Increase in accuracy. Signal Processing (submitted).

- Leclercq, M.; Vittrant, B.; Martin-Magniette, M.L.; Boyer, M.P.S.; Perin, O.; Bergeron, A.; Fradet, Y.; Droit, A. Large-Scale Automatic Feature Selection for Biomarker Discovery in High-Dimensional OMICs Data. Frontiers in Genetics 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artoni, F.; Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. Applying dimension reduction to EEG data by Principal Component Analysis reduces the quality of its subsequent Independent Component decomposition. Neuroimage 2018, 175, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellman, R.E. Dynamic Programming, 2 ed.; Courier Corporation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stoica, P.; Jansson, M. MIMO system identification: State-space and subspace approximation versus transfer function and instrumental variables. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2000, 48, 3087–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, S.A. Nonlinear System Identification - Narmax Methods in the Time, Frequency, and Spatio-temporal Domains; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schoukens, M.; Tiels, K. Identification of Block-oriented Nonlinear Systems Starting from Linear Approximations: A Survey. Automatica 2017, 85, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, P.G.; Torokhti, A.P.; Pearce, C.E.M. A Philosophy for the Modelling of Realistic Non-linear Systems. Processing of Amer. Math. Soc. 2003, 131, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wong, K.D.; Hu, Y.H.; Sayeed, A.M. Detection, classification, and tracking of targets. IEEE Signal Processing Mag. 2002, 19, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, V.J.; Sicuranza, G.L. Polynomial Signal Processing; John Willey & Sons, Inc.: New York, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marelli, D.E.; Fu, M. Distributed weighted least-squares estimation with fast convergence for large-scale systems. Automatica 2015, 51, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torokhti, A.P.; Howlett, P.G. Best Operator Approximation in Modelling of Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. CAS. Part I, Fundamental theory and applications 2002, 49, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar]

- Torokhti, A.; Howlett, P. Best approximation of identity mapping: the case of variable memory. Journal of Approximation Theory 2006, 143, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlovsky, L.; Marzetta, T. Estimating a covariance matrix from incomplete realizations of a random vector. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 1992, 40, 2097–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledoit, O.; Wolf, M. A well-conditioned estimator for large-dimensional covariance matrices. Journal of Multivariate Analysis 2004, 88, 365–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledoit, O.; Wolf, M. Nonlinear shrinkage estimation of large-dimensional covariance matrices. The Annals of Statistics 2012, 40, 1024–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vershynin, R. How Close is the Sample Covariance Matrix to the Actual Covariance Matrix? J. Th. Prob. 2012, 25, 655–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joong-Ho Won, Johan Lim, S.J.K.; Rajaratnam, B. Condition-number-regularized covariance estimation. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B) 2013, 75, 427–450. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.K.; Willsky, A.S. A Krylov Subspace Method for Covariance Approximation and Simulation of Random Processes and Fields. Multidimensional Systems and Signal Processing 2003, 14, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, G.; Van Loan, C. Matrix Computations, 4 ed.; Johns Hopkins Studies in the Mathematical Sciences, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Friedland, S.; Torokhti, A. Generalized Rank-Constrained Matrix Approximations. SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications 2007, 29, 656–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).