Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Broader Optimization Objectives: Future work should go beyond conventional objectives, including new considerations like temperature profiles linked to defect formation for comprehensive optimization.

- Practical Applications: Practical case studies are needed to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

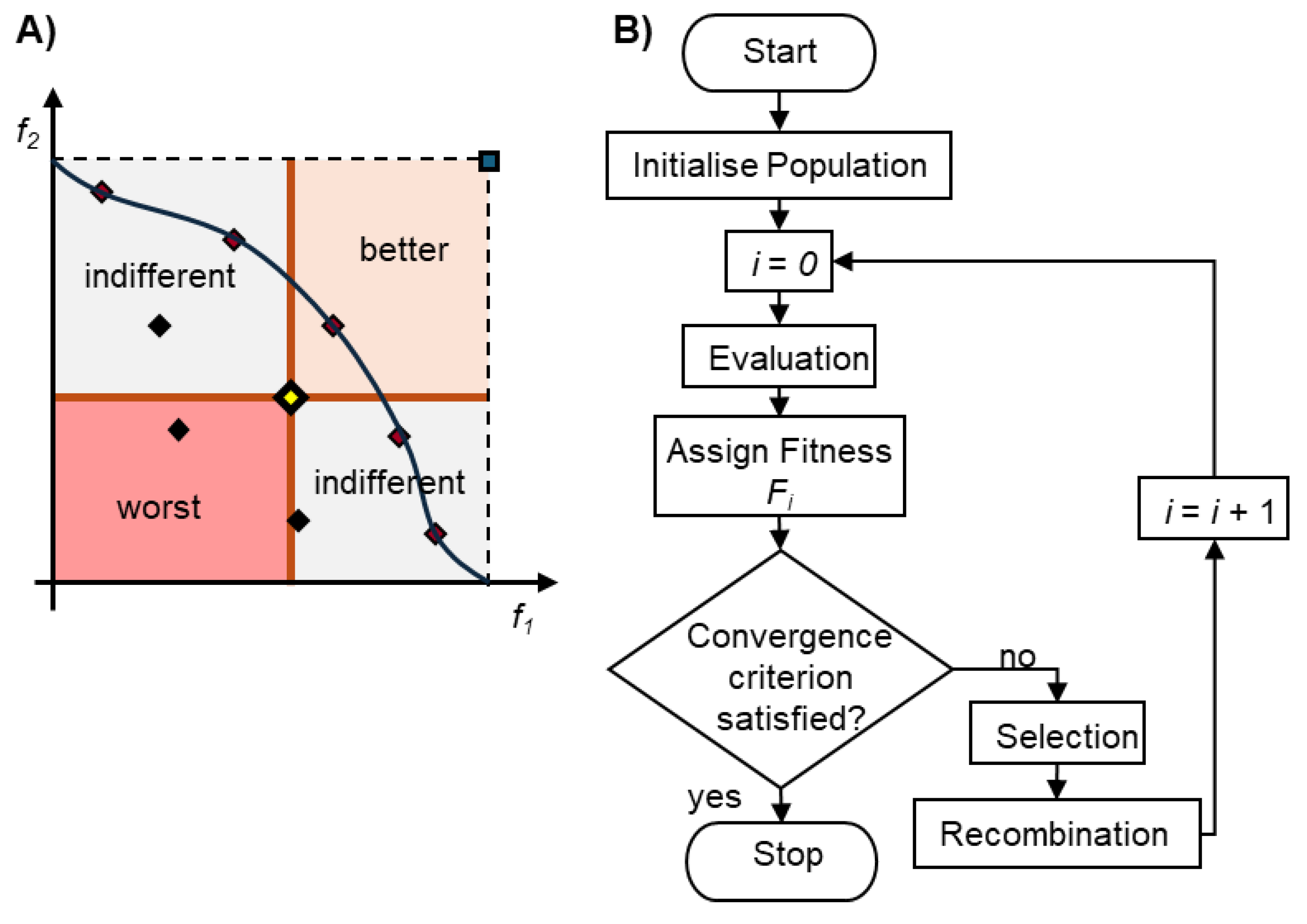

- Multi-Objective Optimization: New approaches should balance conflicting objectives, such as cooling efficiency, mechanical integrity, and defect prevention.

- Data Mining: Using data mining tools is fundamental to understanding the link between the data involved (decision variables and objectives) and building surrogate models.

- Simplified Guidelines: Developing accessible guidelines for adopting advanced optimization techniques is crucial for broader adoption by practitioners.

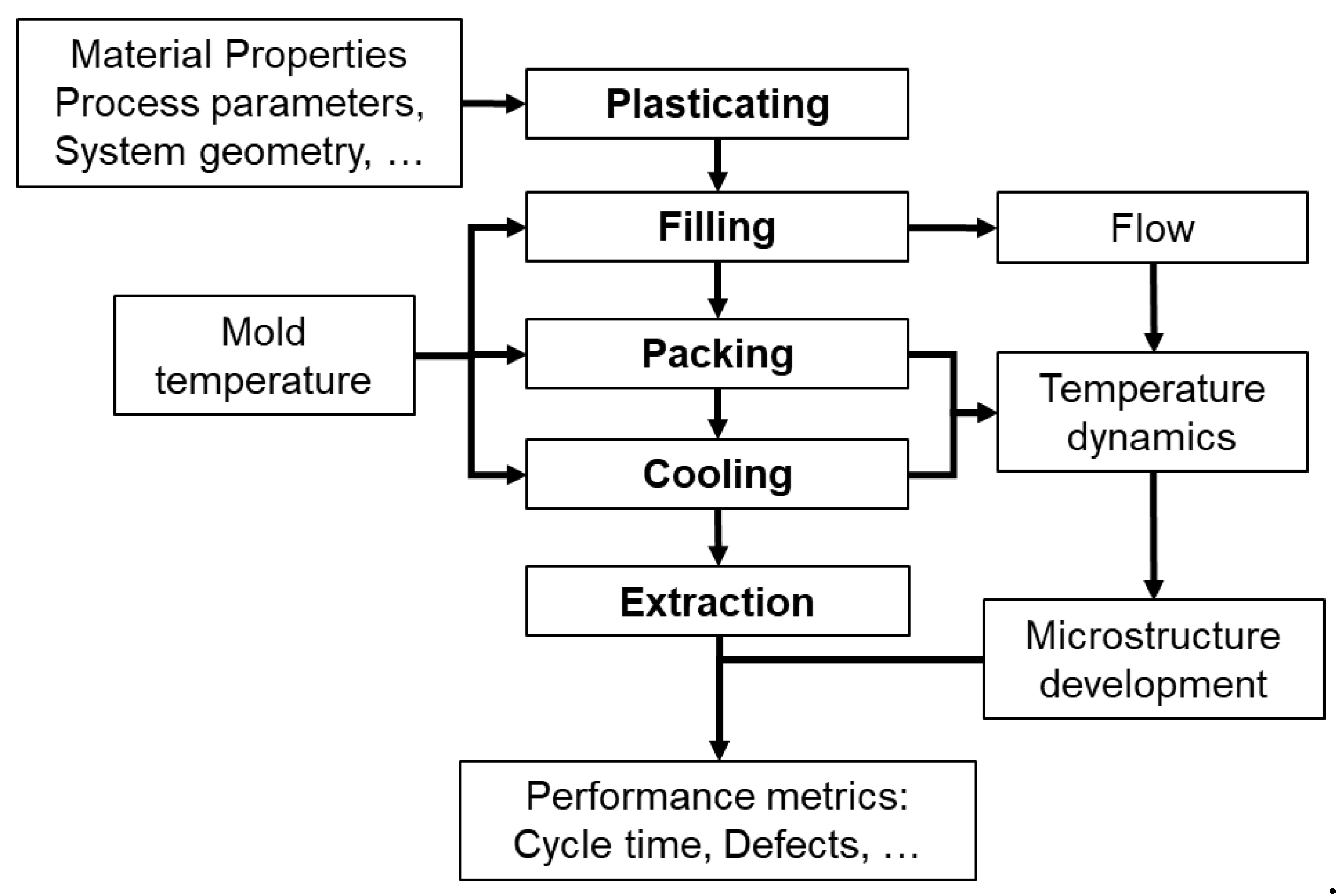

2. Optimization of the Injection Molding Process

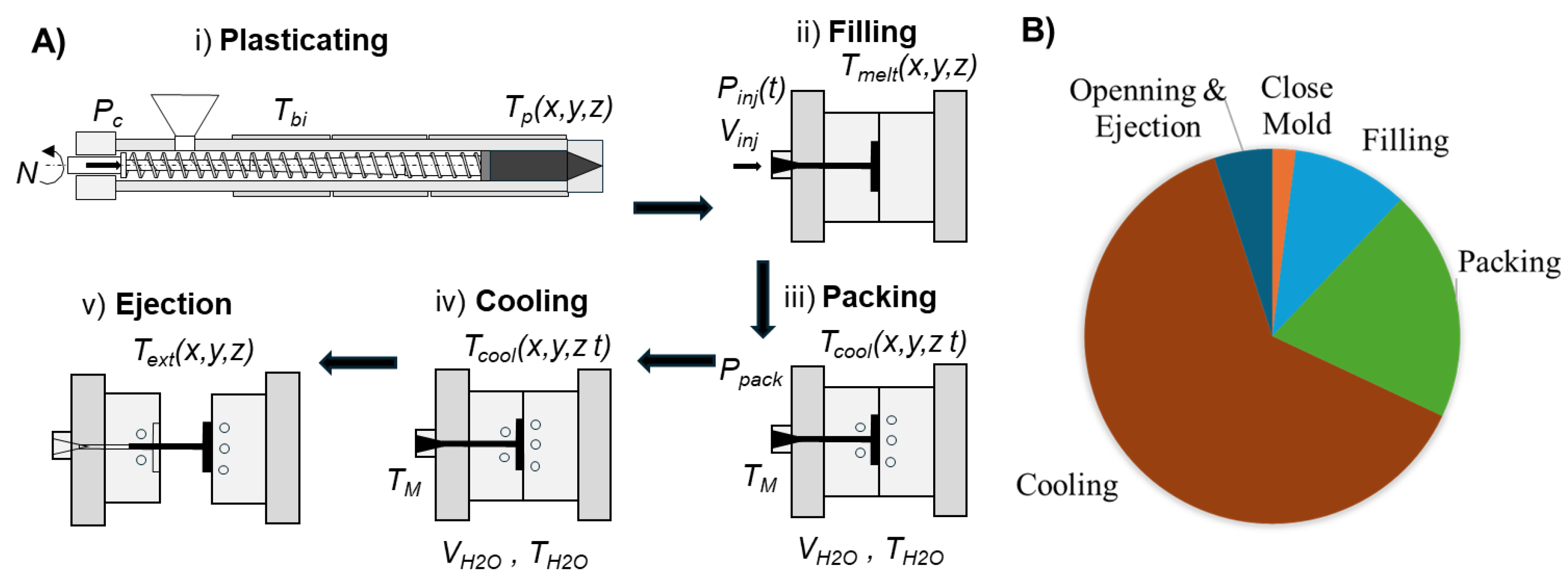

2.1. Injection Molding Cycle

2.2. Optimization Characteristics

- Material Temperature: The initial temperature during the plasticating phase affects polymer viscosity and flow behavior, influencing the subsequent process phases.

- Process Parameters: The injection speed, pressure, packing pressure, and cooling time must be carefully optimized for specific materials and part geometries to ensure consistent quality.

- Feed System and Cooling Channel Design: The geometry of runners, gates, and cooling channels governs flow patterns and cooling rates, directly impacting the final part’s microstructure, mechanical properties, and dimensional stability.

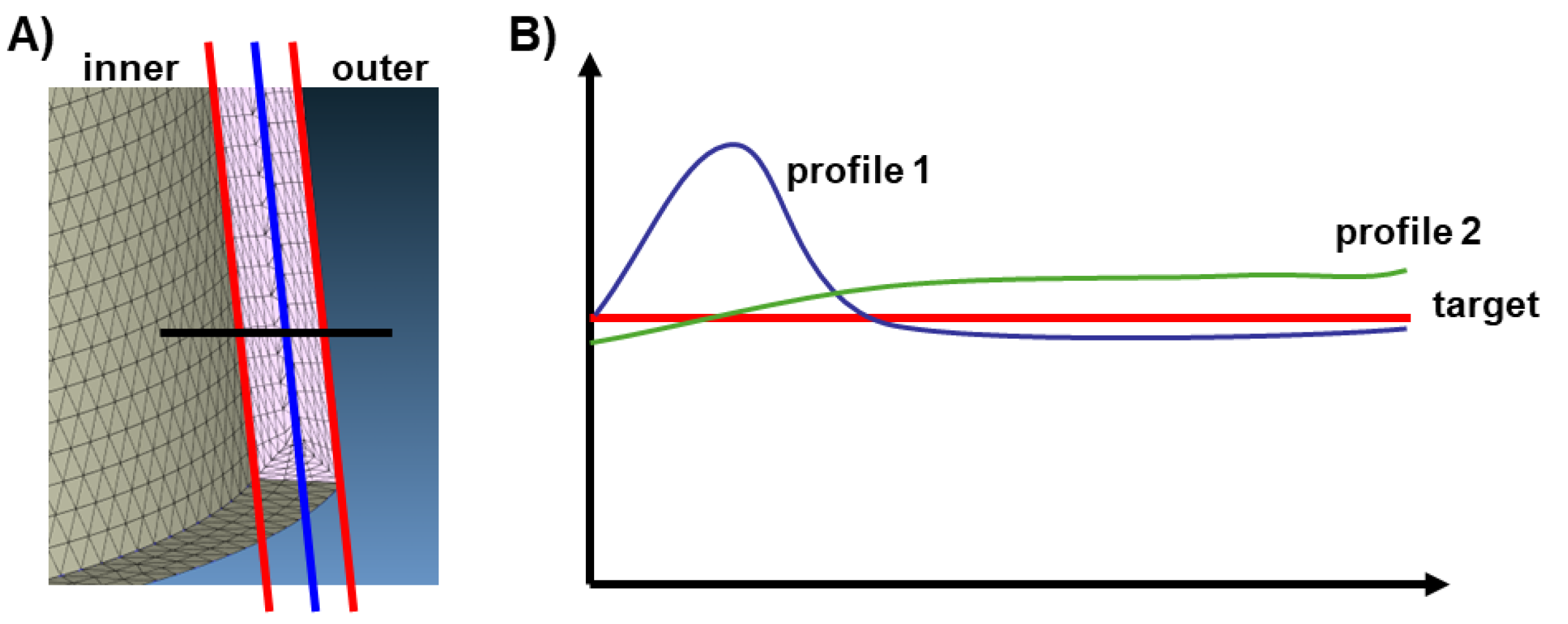

- Mold Temperature: Uniform and appropriately controlled mold temperatures are critical to consistent cooling, solidification, and dimensional accuracy.

2.3. Design Variables

- Melt Temperature (Tmelt): The temperature of the molten polymer affects viscosity, flow behavior, and material properties. Precise control ensures proper mold filling and reduces degradation risks.

- Mold Temperature (Tmold): Mold temperature critically influences cooling rates, cycle times, and product quality. Elevated mold temperatures enhance the surface finish and reduce residual stresses but may extend cycle durations. Conversely, lower temperatures expedite cooling but can lead to defects such as warpage and shrinkage.

- Ejection Temperature (Teje): The temperature at which the part is ejected from the mold impacts dimensional stability and surface integrity.

- Coolant Temperature (Tcoolant) and Air Temperature (Tair): These temperatures directly affect the cooling system's efficiency, and the coolant temperature must be optimized for consistent thermal management.

- Injection Time (tinj): This parameter determines the duration for which material is injected into the mold. Proper timing ensures uniform filling and mitigates air entrapment.

- Packing Time (tpack): Essential for compensating material shrinkage during cooling, optimized packing time prevents voids and sink marks.

- Cooling Time (tcooling): This significantly impacts cycle time and productivity. Reducing cooling time while maintaining part integrity is key to efficient operation.

- Injection Speed (Vinj): The velocity of polymer flow during injection must be optimized to ensure consistent filling and avoid air traps or material shear.

- Injection Pressure (Pinj) and Packing Pressure (Ppack): These pressures ensure mold filling and compensate for shrinkage. Excessive pressure, however, can result in defects like warpage and material stress.

- Diameter (D1, D2, and D3): The diameter of the cooling channels determines the flow rate and cooling efficiency. Larger diameters enhance cooling but may reduce mold strength.

- Pitch Distance (d1, d2, and d3): The spacing between adjacent channels, also known as the pitch distance, affects the cooling uniformity. Too large a pitch may lead to uneven cooling and warpage, while too small a pitch can weaken the mold structure.

- Distance Between Channel Centers and Part Surface (d´1, d´2, and d’3): The distance from the center of the cooling channel to the part surface must be optimized for effective thermal transfer without compromising the part’s structural integrity.

- Length: The overall length of the cooling channels influences the temperature gradient and pressure drop across the system.

2.4. Optimization Objectives

2.5. Optimization Methodologies

- Empirical Methods: These rely on trial and error, using prior experience to refine settings for injection molding. They are straightforward but can be time-consuming.

- Design of Experiments (DOE): DOE systematically examines the influence of input variables on outputs, optimizing conditions by statistically analyzing multiple factors simultaneously [29].

- Taguchi Method: This approach optimizes parameter settings to minimize variability and improve quality, emphasizing robust design [30].

- Taguchi with Grey Relational Analysis (GRA): This method addresses problems with multiple performance metrics by combining Taguchi's robustness with GRA, ensuring comprehensive optimization [31].

- Simplex Method: Designed for linear problems, this mathematical technique efficiently navigates through feasible solutions to find the optimal one.

- Complex Method: Suitable for non-linear and multimodal functions, this approach identifies global or near-global optima in complex scenarios.

- Gradient Methods: Gradient-based techniques, such as gradient descent, use derivative information to optimize smooth, differentiable problems efficiently.

- Direct Search Methods: These are ideal for non-smooth or discontinuous problems, as they do not rely on derivative information.

- Advanced Computational Methods:

- Sequential Approximate Optimization (SAO): SAO creates surrogate models to approximate objectives, enabling faster optimization of complex problems [33].

- Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP): This method solves a series of quadratic subproblems, excelling in optimization scenarios with non-linear constraints [34].

- Stochastic and Evolutionary Approaches:

- Evolutionary Algorithms (EA): Inspired by natural selection, EAs can solve complex, multi-variable, and global optimization problems [35].

- Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Multi-Objective PSO (MOPSO): These algorithms simulate social behavior to solve non-linear, multi-dimensional problems efficiently [36].

- Simulated Annealing (SA) is a probabilistic method for exploring the solution space to approximate the global optimum in complex problems [37].

- Multi-Objective Optimization Techniques:

- Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEA): Adaptation of EA to deal with multi-objective optimization problems based on non-dominance. For example, the NSGA-II (Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II) is a popular MOEA that handles trade-offs between conflicting objectives [38].

- Multi-Objective Firefly Algorithm (MOFA): Inspired by firefly behavior, MOFA effectively solves multi-objective problems with strong convergence properties [39].

- Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MBO): MBO balances exploration and exploitation using Bayesian inference, reducing computational effort [40].

- Topology Optimization

- Topology Optimization (TO): A computational method used to design structures or materials by optimizing their layout within a given design space to achieve the best performance while satisfying constraints [41].

- Data-Driven, AI-Driven, and Fuzzy Logic Approaches

- Data and AI-Driven Optimization: This methodology uses data, such as ANN, to drive the optimization method [42].

- Fuzzy Optimization: This method incorporates fuzzy logic to address uncertainties and imprecise inputs, ensuring robust outcomes [43].

2.6. Numerical Modelling and Surrogates

- Moldflow is best for general injection molding simulations, particularly for optimizing process parameters and defect minimization.

- Moldex3D is ideal for detailed melt flow analysis and handling complex part geometries with high precision.

- ANSYS is more suitable for engineers who require in-depth structural and thermal analysis beyond just the molding process.

- Polynomial Regression (PR): Models variable relationships using polynomial equations [51].

- Response Surface Methodology (RSM): Utilizes statistical approaches to model interactions between variables [52].

- Kriging: A spatial interpolation method that creates surrogate models for high-dimensional data [53].

- Support Vector Machines (SVM) + Linear Regression: Combines SVM with linear regression to enhance prediction accuracy [54].

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANN): Leverage input data to predict outcomes and are often paired with Genetic Algorithms (GA) for enhanced optimization [55].

- Bayesian Methods: Incorporates probability distributions to quantify model uncertainty and enhance predictions [56].

- Radial Basis Function (RBF): Uses neural network methods to approximate multivariable functions [57].

- Quadratic Response Surface (QRS): Applies quadratic polynomial models for response surface analysis [58].

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINN): Integrates physical laws into neural networks for more accurate modeling [59].

- Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) + ANN: Combines GPR and ANN for improved prediction reliability [60].

- Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) + Polynomial Chaos Expansion (PCE): POD reduces dimensionality, while PCE approximates uncertainty propagation [61].

3. Literature on Optimization of Injection Molding

3.1. Organization of This Review

3.2. Global Process Optimization

3.2.1. Single-Objective Optimization

Optimization Method

Step in Injection Molding

Type of Decision Variables (DVs)

Optimization Objectives

-

Warpage: This is the most commonly optimized objective, appearing in numerous studies across various methods. For example:

- Weight Optimization: Studies like [70] have shown that optimizing part weight is crucial for applications requiring lightweight yet durable components.

Modeling Approach

Surrogate Models

References

- Common Objectives: Warpage emerges as the most frequently optimized objective, with studies spanning diverse methodologies, such as empirical approaches [63], Taguchi methods [64], and advanced evolutionary algorithms [65]. This prevalence underscores warpage as a persistent challenge in injection molding.

- Evolving Trends: The recent inclusion of ML-based approaches, particularly for objectives like weld line optimization [76] illustrates a shift toward integrating machine learning into traditional optimization workflows. Integration of Hybrid Methods: The combination of EA and PSO [67] for reducing blush defects showcases the potential of hybrid methodologies in addressing complex optimization objectives.

3.2.2. Multi-Objective Optimization Using Aggregation Methods

Optimization Method

- Empirical Methods dominate optimization studies, frequently using OC as decision variables to simulate and refine process conditions.

- Gradient-based methods and Taguchi Designs are versatile and effectively capture the interactions of OCs with other decision variables, such as cooling channels or gate locations.

- Nature-inspired algorithms, such as PSO and EA, excel in handling multiple objectives, often incorporating OCs with other design variables.

Step in Injection Molding

Type of Decision Variables (DVs)

-

OC (Operating Conditions): Operating conditions are the most frequently studied decision variable, underscoring their critical role in injection molding optimization. These variables typically include process parameters such as temperature, pressure, injection speed, and cooling time. Optimizing OC is fundamental to improving product quality, reducing defects, and enhancing process efficiency. For instance:

- Fu & Ma optimized operating conditions during the ejection stage to reduce defects like warpage [88].

- Nasir et al. employed RSM to refine operating conditions during the cooling and packing phases, achieving improved dimensional accuracy [89]. The widespread focus on OC directly influences the material behavior during molding and the resulting part quality.

- CC (Cooling Channel): Decision variables related to cooling channels are vital for optimizing the cooling stage of injection molding. Studies such as Cervantes-Vallejo et al. focus on designing efficient cooling systems to achieve uniform temperature distribution and minimize cycle time [90].

- GL (Gate Location): Gate location decision variables are crucial for optimizing the filling phase. Proper gate placement helps enhance material flow, reduce stress concentrations, and minimize defects like weld lines. Li & Wang demonstrated the importance of gate location optimization for achieving better mechanical properties and filling efficiency [91].

- RG (Runner Geometry): Runner geometry decision variables aim to optimize the distribution of molten material across the mold cavities. Efficient runner designs minimize material wastage and pressure loss, creating a balanced filling process.

- PG (Part Geometry): Decision variables related to part geometry are fundamental for optimizing manufacturability and product performance. Park et al. considered part geometry in their optimization, highlighting its role in reducing material usage while maintaining structural integrity [92].

Number of Objectives

Modeling Approach

Surrogate Models

- ANOVA: Fonseca et al. utilized ANOVA to analyze the variance in aggregated objectives, showcasing its effectiveness in determining the impact of key parameters [96].

- GRA (Grey Relational Analysis): Li et al. employed GRA for multi-objective optimization, demonstrating its ability to rank and compare alternatives in complex decision-making scenarios [97].

- Other Aggregation Methods: Fuzzy systems, PCA-GRA combinations, and ANN-based approaches highlight the increasing use of computational intelligence to tackle complex, aggregated multi-objective problems.

3.2.3. Multi-Objective Optimization

Optimization Method

Step in Injection Molding

Type of Decision Variables (DVs)

Number of Objectives

Modelling

Surrogate Methods

References

- Expanding the range of design variables, including unconventional combinations.

- Addressing computational challenges in many-objective optimization.

- Incorporating experimental validation to complement simulation studies.

3.3. Optimization of CCC

- Wang et al. [193] utilized Kriging-based surrogate modeling to optimize CCC and gate geometry, demonstrating how surrogate models can reduce computational costs while maintaining accuracy.

- Silva and Rodrigues [194] and Kanbur et al. [195] leveraged advanced surrogate and machine learning methods like ANN, showing the potential of AI-driven optimization for complex geometries. These studies underscore the importance of combining AI techniques with traditional simulation tools for improved performance.

- Empirical methods as employed by Hsu et al. [196] and Saifullah et al. [197] remain popular but highlight the limitations of relying on trial-and-error approaches to achieve globally optimal designs. Expanding on these methods with advanced computational tools could yield more robust and adaptable solutions.

- Expanded Multi-Objective Frameworks: Future research should adopt more robust multi-objective optimization techniques, such as NSGA-II, NSGA-III, or MOEA/D, to capture and address cooling performance, cost, and sustainability trade-offs. Objectives should be carefully selected to reflect real-world constraints and priorities. Multi-objective studies should also incorporate advanced visualization techniques to enable better decision-making.

- Integration of Advanced Modeling Tools: Combining simulation tools like Moldflow, ANSYS, and COMSOL with experimental validation will improve the reliability of optimization results. Hybrid frameworks, as demonstrated by Jahan et al. [198] and Shen et al. [199] are particularly promising. Integrating cloud computing and parallel processing could further enhance the scalability of these hybrid frameworks.

- Sustainability and Cost Optimization: The increasing focus on green manufacturing necessitates incorporating life cycle analysis (LCA) into CCC design. Future studies should optimize for material efficiency and energy savings alongside thermal performance. Incorporating sustainability metrics into optimization frameworks could drive innovation in eco-friendly mold designs.

- AI-Driven Optimization: Machine learning (ML) techniques, as explored by Gao et al. [42], should be further developed for predictive modeling, real-time optimization, and adaptive cooling strategies. Integrating AI with topology optimization could open new possibilities for intelligent and autonomous CCC designs. AI-driven methods could also be used to develop predictive maintenance schedules for molds, enhancing their operational lifespan.

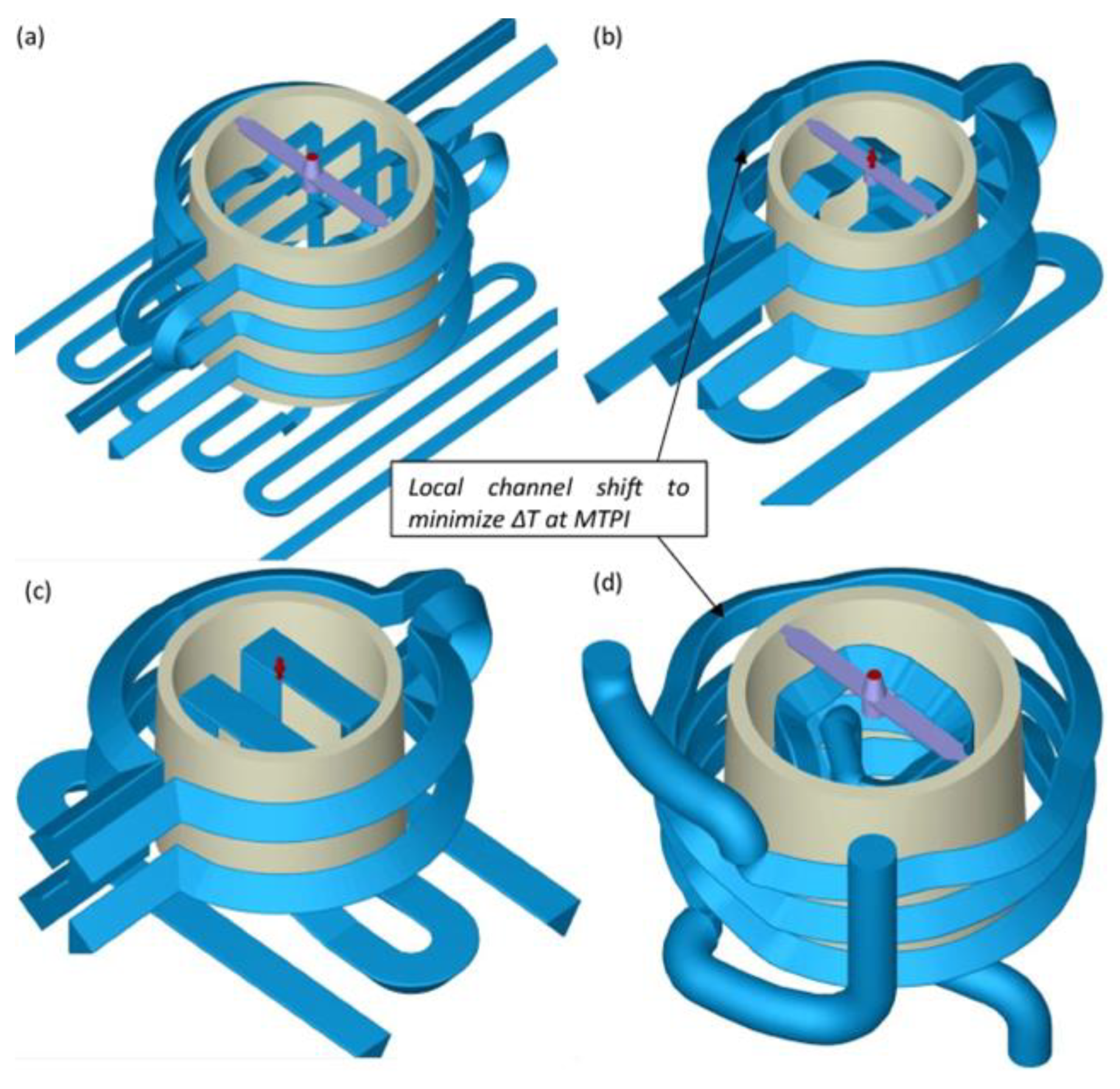

- Generative Design and Dynamic CCC: GD and DCCC, as discussed by Wilson et al. [13] and Kirchheim et al. [12], have the potential to revolutionize CCC design. Research should focus on scaling these approaches for industrial applications while addressing computational challenges. Cloud-based generative design platforms could democratize access to these advanced technologies, enabling broader adoption.

- Real-World Applications and Validation: Despite the progress in modeling and simulation, empirical studies like those by Eiamsa-Ard and Wannissorn [200] highlight the importance of real-world testing. Future work should emphasize validation in industrial settings to bridge the gap between theory and practice. Collaborations with industry stakeholders could facilitate the development of CCC designs tailored to specific manufacturing scenarios.

- Exploration of Novel Materials: Advancements in materials science could play a pivotal role in optimizing CCC designs. Future studies should explore using advanced composites and metal alloys to enhance molds' thermal and mechanical properties. The integration of material-specific optimization methods could lead to breakthroughs in CCC performance.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Conflicts of interest

Open Access

References

- Rosato D V, Rosato D V, Rosato MG (2000) Injection Molding Handbook. Springer, Boston, MA.

- Menges G, Rosato D V., Rosato D V. (2001) Injection Molding Handbook. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Osswald TA, Hernández-Ortiz JP (2006) Polymer Processing. Munich.

- Kazmer DO (2022) Injection Mold Design Engineering, 3rd ed. Hanser Publishers.

- Deb K (2001) Multi-objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms. Wiley, Chichester.

- Coello CAC, Lamont GB, Van Veldhuizen DA (2007) Evolutionary Algorithms for Solving Multi-Objective Problems. Springer, Boston, MA.

- Chen PHA, Villarreal-Marroquín MG, Dean AM, Santner TJ, Mulyana R, Castro JM (2018) Sequential design of an injection molding process using a calibrated predictor. Journal of Quality Technology 50:309–326. [CrossRef]

- Kanbur BB, Suping S, Duan F (2020) Design and optimization of conformal cooling channels for injection molding: a review. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 106:3253–3271. [CrossRef]

- Feng Q, Wang C, Li S (2021) A review of conformal cooling for injection molding. Polymers (Basel) 13:945. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar-Cunha A, Covas JA, Sikora J (2022) Optimization of Polymer Processing: A Review (Part II-Molding Technologies). Materials 15:1–20. [CrossRef]

- Huang CT, Lin TW, Jong WR, Chen SC (2021) A methodology to predict and optimize ease of assembly for injected parts in a family-mold system. Polymers (Basel) 13:. [CrossRef]

- Kirchheim A, Katrodiya Y, Zumofen L, Ehrig F, Wick C (2021) Dynamic conformal cooling improves injection molding: Hybrid molds manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 114:107–116. [CrossRef]

- Wilson N, Gupta M, Patel M, Mazur M, Nguyen V, Gulizia S, Cole I (2024) Generative design of conformal cooling channels for hybrid-manufactured injection moulding tools. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 133:861–888. [CrossRef]

- Shayfull Z, Sharif S, Zain AM, Ghazali MF, Saad RM (2014) Potential of conformal cooling channels in rapid heat cycle molding: A review. Advances in Polymer Technology 33:. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes C, Pontes AJ, Viana JC, Gaspar-Cunha A (2018) Modeling and Optimization of the Injection-Molding Process: A Review. Advances in Polymer Technology 37:429–449. [CrossRef]

- Wei Z, Wu J, Shi N, Li L (2020) Review of conformal cooling system design and additive manufacturing for injection molds. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 17:5414–5431. [CrossRef]

- Feng S, Kamat AM, Pei Y (2021) Design and fabrication of conformal cooling channels in molds: Review and progress updates. Int J Heat Mass Transf 171:121082. [CrossRef]

- Silva HM, Noversa JT, Fernandes L, Rodrigues HL, Pontes AJ (2022) Design, simulation and optimization of conformal cooling channels in injection molds: a review. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 120:4291–4305. [CrossRef]

- Osswald T, Turng L-S, Gramann PJ (2007) Injection Molding Handbook. Hanser, Munich.

- Michaeli W, Müller J, Schmachtenberg E (2020) Understanding Injection Molding Technology, 2nd ed. Carl Hanser Verlag.

- Liu F, Pang J, Xu Z (2024) Multi-Objective Optimization of Injection Molding Process Parameters for Moderately Thick Plane Lens Based on PSO-BPNN, OMOPSO, and TOPSIS. Processes 12:. [CrossRef]

- Sherbelis G, Garvey E, Kazmer D (1997) Methods and benefits of establishing a Process Window. Annual Technical Conference - ANTEC, Conference Proceedings 1:545–550.

- Beaumont JP, Nagel R, Sherman R (2002) Successful Injection Molding: Process, Design, and Simulation. Hanser.

- Osswald TA, Hernández-Ortiz JP (2006) Polymer Processing: Modeling and Simulation. Hanser, Munich.

- Goodship V (2017) Injection Molding: A Practical Guide. Smithers Rapra.

- Menges G, Michaeli W, Mohren P (2008) How to Make Injection Molds. Hanser, Munich.

- Huntington-Klein N (2022) The Effect: An Introduction to Research Design and Causality. CRC Press.

- Huang CH, Chen MS, Li YR (2021) Application of Moldex3D in Injection Molding Simulation for Enhancing Product Quality. Polym Eng Sci 61:2100–2108.

- Montgomery DC (2019) Design and Analysis of Experiments, 10th ed. John Wiley & Sons.

- Taguchi G (1986) Introduction to Quality Engineering. Asian Productivity Organization.

- Deng JL (1989) Introduction to grey system theory. The Journal of Grey System 1:1–24.

- Kolda G, Lewis RM, Torczon V (2003) Optimization by Direct Search: New Perspectives on Some Classical and Modern Methods. SIAM Review 45:385–482. [CrossRef]

- Jones DR, Schonlau M, Welch WJ (1998) Efficient global optimization of expensive black-box functions. Journal of Global Optimization 13:455–492.

- Gill PE, Murray W, Wright MH (1981) Practical Optimization. Academic Press.

- Goldberg DE (1989) Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization, and Machine Learning. Addison-Wesley.

- Kennedy J, Eberhart R (1995) Particle swarm optimization. In: Proceedings of ICNN’95 - International Conference on Neural Networks. pp 1942–1948.

- Kirkpatrick S, Gelatt CD, Vecchi MP (1983) Optimization by simulated annealing. Science (1979) 220:671–680.

- Deb K, Pratap A, Agarwal S, Meyarivan T (2002) A fast and elitist multi-objective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 6:182–197. [CrossRef]

- Yang XS (2009) Firefly algorithms for multimodal optimization. In: Stochastic Algorithms: Foundations and Applications. Springer, pp 169–178.

- Shahriari B, Swersky K, Wang Z, Adams RP, de Freitas N (2016) Taking the human out of the loop: A review of Bayesian optimization. Proceedings of the IEEE 104:148–175. [CrossRef]

- Wu T, Tovar A (2018) Design for additive manufacturing of conformal cooling channels using thermal-fluid topology optimization and application in injection molds. Proceedings of the ASME Design Engineering Technical Conference 2B-2018:. [CrossRef]

- Gao Z, Dong G, Tang Y, Zhao YF (2023) Machine learning aided design of conformal cooling channels for injection molding. J Intell Manuf 34:1183–1201. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann HJ (1996) Fuzzy Set Theory—And Its Applications. Springer.

- Mukras SMS (2020) Experimental-based optimization of injection molding process parameters for short product cycle time. Advances in Polymer Technology 2020. [CrossRef]

- Moldflow Web Page. https://www.code-ps.com/moldflow-toolbox. Accessed 18 Feb 2025.

- Moldex3D Web page. https://www.moldex3d.com/. Accessed 18 Feb 2025.

- Ansys Web Page. https://www.ansys.com/. Accessed 18 Feb 2025.

- Zhao P, Zhou H, Li Y, Li D (2010) Process parameters optimization of injection molding using a fast strip analysis as a surrogate model. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 49:949–959. [CrossRef]

- Trinh V (2024) Application of Digital Simulation Tool in Designing of Injection Mold for Sustainable Manufacturing. EUREKA: Physics and Engineering 100–106. [CrossRef]

- Forrester A, Sobester A, Keane AJ (2008) Engineering Design via Surrogate Modelling: A Practical Guide. Wiley.

- Draper NR, Smith H (1998) Applied Regression Analysis. Wiley.

- Myers RH, Montgomery DC, Anderson-Cook CM (2016) Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product Optimization Using Designed Experiments, 4th ed. Wiley.

- Sacks J, Welch WJ, Mitchell TJ, Wynn HP (1989) Design and analysis of computer experiments. Statistical Science 4:409–435. [CrossRef]

- Smola AJ, Schölkopf B (2004) A tutorial on support vector regression. Stat Comput 14:199–222. [CrossRef]

- Bishop CM (1995) Neural Networks for Pattern Recognition. Oxford University Press.

- Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB (2013) Bayesian Data Analysis, 3rd ed. Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Broomhead DS, Lowe D (1988) Multivariable functional interpolation and adaptive networks. Complex Systems 2:321–355.

- Box GEP, Draper NR (2007) Response Surfaces, Mixtures, and Ridge Analyses, 2nd ed. Wiley.

- Son S, Jeong J, Jeong D, Sun K, Oh K-Y (2024) Physics-informed neural network: principles and applications. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen CE, Williams CKI (2006) Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning. MIT Press.

- Ghanem RG, Spanos PD (1991) Stochastic Finite Elements: A Spectral Approach. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Feng Q, Liu L, Zhou X (2020) Automated multi-objective optimization for thin-walled plastic products using Taguchi, ANOVA, and hybrid ANN-MOGA. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 106:559–575. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa M, Aoyama H, Sano N (2018) Basic study on automatic determination of injection conditions based on automatic recognition of forming states. Journal of Advanced Mechanical Design, Systems and Manufacturing 12:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TK, Hwang CJ, Lee BK (2017) Numerical investigation of warpage in insert injection-molded lightweight hybrid products. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 18:187–195. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Fan XY, Guo YH, Liu X, Huang HY, Cao YL, Li LL (2021) Optimization of Injection Molding Process of Transparent Complex Multi-Cavity Parts Based on Kriging Model and Various Optimization Techniques. Arab J Sci Eng 46:11835–11845. [CrossRef]

- Ma Z, Li Z, Huang M, Liu C, Shen C, Wang X (2022) Geometry Optimization of the Runner Insert for Improving the Appearance Quality of the Injection Molded Auto Part. Polymers (Basel) 14:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Mollaei Ardestani A, Azamirad G, Shokrollahi Y, Calaon M, Hattel JH, Kulahci M, Soltani R, Tosello G (2023) Application of Machine Learning for Prediction and Process Optimization—Case Study of Blush Defect in Plastic Injection Molding. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 13:. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Zhang QW, Zhang W, Zhang P (2015) Optimization of injection molding process parameters to improve the mechanical performance of polymer product against impact. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 76:2199–2208. [CrossRef]

- Kurkin E, Kishov E, Barcenas OUE, Chertykovtseva V (2021) Gate Location Optimization of Injection Molded Aerospace Brackets Using Metaheuristic Algorithms. 2021 International Scientific and Technical Engine Conference, EC 2021 1–6. [CrossRef]

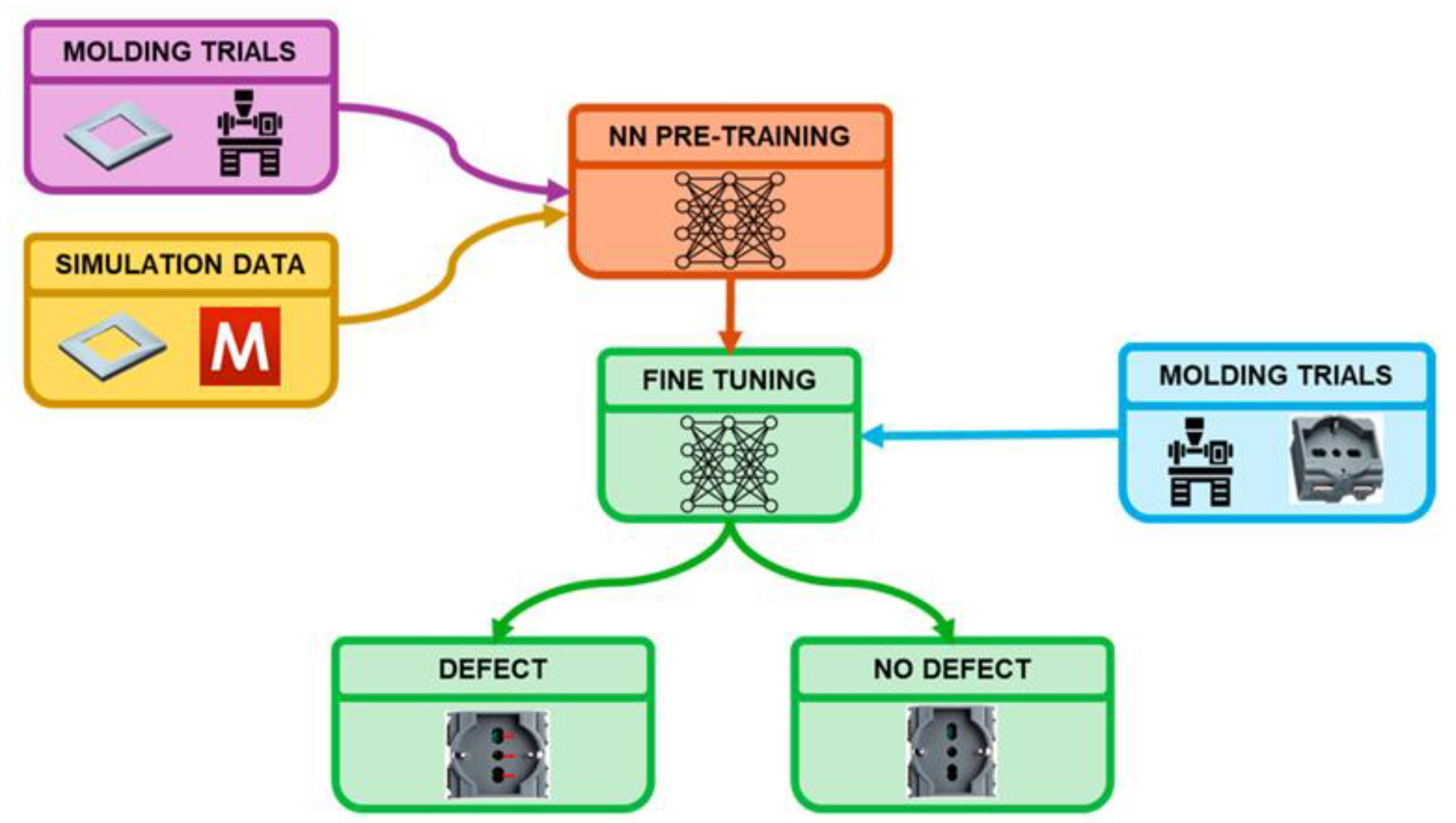

- Lockner Y, Hopmann C (2021) Induced network-based transfer learning in injection molding for process modelling and optimization with artificial neural networks. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 112:3501–3513. [CrossRef]

- Dejene ND, Wolla DW (2023) Comparative analysis of artificial neural network model and analysis of variance for predicting defect formation in plastic injection moulding processes. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 1294:12050. [CrossRef]

- Gao Y, Wang X (2009) Surrogate-based process optimization for reducing warpage in injection molding. J Mater Process Technol 209:1302–1309. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Dang K, Wang X, Zhou Y, Yang W, Xie P (2023) Intelligent recommendation system of injection molding process parameters based on CAE simulation, process window and machine learning. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 128:4703–4716. [CrossRef]

- Saad S, Sinha A, Cruz C, Régnier G, Ammar A (2022) Towards an accurate pressure estimation in injection molding simulation using surrogate modeling. International Journal of Material Forming 15:. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Wang X, Li Z, Gu J, Ruan S, Shen C, Wang X (2016) Integration optimization of molding and service for injection-molded product. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 84:2019–2028. [CrossRef]

- Baruffa G, Pieressa A, Sorgato M, Lucchetta G (2024) Transfer Learning-Based Artificial Neural Network for Predicting Weld Line Occurrence through Process Simulations and Molding Trials. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 8:. [CrossRef]

- Kastelic T, Starman B, Cafuta G, Halilovic̆ M, Mole N (2022) Correction of mould cavity geometry for warpage compensation. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 123:1957–1971. [CrossRef]

- Lee BH, Kim BH (1995) Optimization of Part Wall Thicknesses to Reduce Warpage of Injection-Molded Parts based on the Modified Complex Method. Polym Plast Technol Eng 34:793–811. [CrossRef]

- Rhee BO, Park CS, Chang HK, Jung HW, Lee YJ (2010) Automatic generation of optimum cooling circuit for large injection molded parts. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 11:439–444. [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Marroquin MG, Castro JM, Chacon-Mondragon OL, Cabrera-Rios M (2010) Simulation optimization applications in injection molding. Annual Technical Conference - ANTEC, Conference Proceedings 1:250–254. [CrossRef]

- Lin WC, Fan FY, Huang CF, Shen YK, Wang H (2022) Analysis of the Warpage Phenomenon of Micro-Sized Parts with Precision Injection Molding by Experiment, Numerical Simulation, and Grey Theory. Polymers (Basel) 14:. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Deng YM, Sun BS (2009) Injection molding warpage optimization based on a mode-pursuing sampling method. Polymer - Plastics Technology and Engineering 48:767–774. [CrossRef]

- Xia W, Luo B, Liao X (2010) An enhanced global optimization method based on gaussian process and its application of warpage control in injection molding. 2010 IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation, ICIA 2010 970–975. [CrossRef]

- Hsu YM, Jia X, Li W, Manganaris P, Lee J (2022) Sequential optimization of the injection molding gate locations using parallel efficient global optimization. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 120:3805–3819. [CrossRef]

- Shen C, Wang L, Cao W, Wu J (2007) Optimization for injection molding process conditions of the refrigeratory top cover using combination method of artificial neural network and genetic algorithms. Polymer - Plastics Technology and Engineering 46:105–112. [CrossRef]

- Lockner Y, Hopmann C, Zhao W (2022) Transfer learning with artificial neural networks between injection molding processes and different polymer materials. J Manuf Process 73:395–408. [CrossRef]

- Pieressa A, Baruffa G, Sorgato M, Lucchetta G (2024) Enhancing weld line visibility prediction in injection molding using physics-informed neural networks. J Intell Manuf. [CrossRef]

- Fu J, Ma Y (2018) Computer-aided engineering analysis for early-ejected plastic part dimension prediction and quality assurance. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 98:2389–2399. [CrossRef]

- Nasir SM, Shayfull Z, Sharif S, hadj Abdellah A El, Fathullah M, Noriman NZ (2021) Evaluation of shrinkage and weld line strength of thick flat part in injection moulding process. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 43:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Vallejo FJ, Hernández-Navarro C, Camarillo-Gómez KA, Louvier-Hernández JF, Navarrete-Damián J (2024) Thermal-Structural optimization of a rapid thermal response mold: Comprehensive simulation of a heating rod system and a fluid cooling system implemented MSR-PSO-FEM. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 47:. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Wang X (2012) A Black Box Method for Gate Location Optimization in Plastic Injection Molding. Advances in Polymer Technology 32:474–485. [CrossRef]

- Park SW, Choi JH, Lee BC (2018) Multi-objective optimization of an automotive body component with fiber-reinforced composites. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 58:2203–2217. [CrossRef]

- Heidari BS, Davachi SM, Moghaddam AH, Seyfi J, Hejazi I, Sahraeian R, Rashedi H (2018) Optimization simulated injection molding process for ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene nanocomposite hip liner using response surface methodology and simulation of mechanical behavior. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 81:95–105. [CrossRef]

- Heidari BS, Moghaddam AH, Davachi SM, Khamani S, Alihosseini A (2019) Optimization of process parameters in plastic injection molding for minimizing the volumetric shrinkage and warpage using radial basis function (RBF) coupled with the k-fold cross validation technique. Journal of Polymer Engineering 39:481–492. [CrossRef]

- Sreedharan J, Jeevanantham AK, Rajeshkannan A (2020) Multi-objective optimization for multi-stage sequential plastic injection molding with plating process using RSM and PCA-based weighted-GRA. Proc Inst Mech Eng C J Mech Eng Sci 234:1014–1030. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca JH, Lee J, Jang W, Han D, Kim N, Lee H (2023) Manufacturability-constrained optimization for enhancing quality and suitability of injection-molded short fiber-reinforced plastic/metal hybrid automotive structures. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 66:1–19. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Zhao C, Jia F, Li S, Ma S, Liang J (2023) Optimization of injection molding process parameters for the lining of IV hydrogen storage cylinder. Sci Rep 13:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Natsume S (2014) Multi-objective optimization of volume shrinkage and clamping force for plastic injection molding via sequential approximate optimization. Simul Model Pract Theory 48:35–44. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Zhou XH, Wang HF, Wang W (2010) Multi-objective optimal approach for injection molding based on surrogate model and particle swarm optimization algorithm. J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ Sci 15:88–93. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Fan X, Guo Y, Lu X, Wang D, Ding W (2022) Multi-objective Optimization and Quality Monitoring of Two-piece Injection Molding Products. SAE International Journal of Materials and Manufacturing 16:. [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Iniesta A, Cuate O, Schütze O (2019) Multi-objective and many objective design of plastic injection molding process. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 102:3165–3180. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Wang J, Lin J, Guo Q, Chen K, Ma L (2016) Multiobjective optimization of injection molding process parameters based on Opt LHD, EBFNN, and MOPSO. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 85:2857–2872. [CrossRef]

- Tian M, Gong X, Yin L, Li H, Ming W, Zhang Z, Chen J (2017) Multi-objective optimization of injection molding process parameters in two stages for multiple quality characteristics and energy efficiency using Taguchi method and NSGA-II. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 89:241–254. [CrossRef]

- Jung J, Park K, Cho B, Park J, Ryu S (2023) Optimization of injection molding process using multi-objective bayesian optimization and constrained generative inverse design networks. J Intell Manuf 34:3623–3636. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Li J, Sun Z, Bo C, Gao F (2023) Multiobjective optimization of injection molding parameters based on the GEK-MPDE method. Journal of Polymer Engineering 43:820–831. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes C, Pontes AJ, Viana JC, Gaspar-Cunha A (2010) Using multiobjective evolutionary algorithms in the optimization of operating conditions of polymer injection molding. Polym Eng Sci 50:1667–1678. [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Fan X, Guo Y, Lu X, Wang C, Ding W (2022) Quality prediction and control of thin-walled shell injection molding based on GWO-PSO, ACO-BP, and NSGA-II. Journal of Polymer Engineering 42:876–884. [CrossRef]

- Zeng W, Yi G, Zhang S, Wang Z (2024) Multi-objective optimization method of injection molding process parameters based on hierarchical sampling and comprehensive entropy weights. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 133:1481–1499. [CrossRef]

- Guo W, Lu T, Zeng F, Zhou X, Li W, Yuan H, Meng Z (2024) Multi-Objective Optimization of Microcellular Injection Molding Process Parameters to reduce energy consumption and improve product quality. Res Sq. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Yan Z, Shan X (2018) Optimization of Process Parameters for Vertical-Faced Polypropylene Bottle Injection Molding. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2018. [CrossRef]

- Mubarak Abdullah Ali Mohsen Al-Hadad, Wang Q (2019) CAE Analysis and Structure Optimization Design of Injection Mold for Charge Upper Cover. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology 8:33–36. [CrossRef]

- Meiabadi MS, Moradi M, Kazerooni A, Demers V (2022) Multi-objective optimisation of plastic injection moulding process using mould flow analysis and response surface methodology. International Journal of Materials and Product Technology 64:140–155. [CrossRef]

- Hiyane-Nashiro G, Hernández-Hernández M, Rojas-García J, Rodriguez-Resendiz J, Álvarez-Alvarado JM (2022) Optimization of the Reduction of Shrinkage and Warpage for Plastic Parts in the Injection Molding Process by Extended Adaptive Weighted Summation Method. Polymers (Basel) 14:. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Yáñez AB, Méndez-Vázquez YM, Cabrera-Ríos M (2014) Simulation-based process windows simultaneously considering two and three conflicting criteria in injection molding. Prod Manuf Res 2:603–623. [CrossRef]

- Lan X, Li C, Yang C, Xue C (2019) Optimization of injection molding process parameters and axial surface compensation for producing an aspheric plastic lens with large diameter and center thickness. Appl Opt 58:927. [CrossRef]

- Ryu Y, Sohn JS, Yun CS, Cha SW (2020) Shrinkage and warpage minimization of glass-fiber-reinforced polyamide 6 parts by microcellular foam injection molding. Polymers (Basel) 12:. [CrossRef]

- Idayu N, Md Ali MA, Kasim MS, Abdul Aziz MS, Raja Abdullah RI, Sulaiman MA (2020) Flow analysis of three plate family injection mould using moldflow software analysis. Springer Singapore.

- Ashaari FF, Amin YM (2022) Optimization of Thermoplastic Material for Plastic Injection Molding Process by Using Taguchi Method. Research Progress in Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering 3:831–838.

- Vasiliki I, George-christopher V (2024) Injection molding control parameter assessment by nested Taguchi design of simulation experiments : a case study. Materials Research Proceedings 41:2757–2766. [CrossRef]

- Md Ali MA, Idayu N, Salleh MS, Ali Mokhtar MN, Abdullah Z, Sivaraos (2020) Optimization process parameters of flat plastic part having side gate system using flow analysis software. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering 399–409. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Wang Y, Fang M (2021) Study on Injection Molding Process Simulation and Process Parameter Optimization of Automobile Instrument Light Guiding Support. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2021. [CrossRef]

- Huang WT, Tasi ZY, Ho WH, Chou JH (2022) Integrating Taguchi Method and Gray Relational Analysis for Auto Locks by Using Multiobjective Design in Computer-Aided Engineering. Polymers (Basel) 14:. [CrossRef]

- Ravikiran B, Pradhan DK, Jeet S, Bagal DK, Barua A, Nayak S (2022) Parametric optimization of plastic injection moulding for FMCG polymer moulding (PMMA) using hybrid Taguchi-WASPAS-Ant Lion optimization algorithm. Mater Today Proc 56:2411–2420. [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Marroquín MG, Svenson JD, Sun F, Santner TJ, Dean A, Castro JM (2013) A comparison of two metamodel-based methodologies for multiple criteria simulation optimization using an injection molding case study. Journal of Polymer Engineering 33:193–209. [CrossRef]

- Chang H, Zhang G, Sun Y, Lu S (2022) Using Sequence-Approximation Optimization and Radial-Basis-Function Network for Brake-Pedal Multi-Target Warping and Cooling. Polymers (Basel) 14:. [CrossRef]

- Tan KH, Yuen MMF (2000) A Fuzzy multiobjective approach for minimization of injection molding defects. Polym Eng Sci 40:956–971. [CrossRef]

- Bensingh RJ, Machavaram R, Boopathy SR, Jebaraj C (2019) Injection molding process optimization of a bi-aspheric lens using hybrid artificial neural networks (ANNs) and particle swarm optimization (PSO). Measurement (Lond) 134:359–374. [CrossRef]

- Roslan N, Rahim SZA, Abdellah AEH, Abdullah MMAB, Błoch K, Pietrusiewicz P, Nabiałek M, Szmidla J, Kwiatkowski D, Vasco JOC, Saad MNM, Ghazali MF (2021) Optimisation of shrinkage and strength on thick plate part using recycled ldpe materials. Materials 14:. [CrossRef]

- Lin F, Duan J, Lu Q, Li X (2022) Optimization of Injection Molding Quality Based on Bp Neural Network and Pso. Materiali in Tehnologije 56:491–497. [CrossRef]

- Deng YM, Lam YC, Britton GA (2004) Optimization of injection moulding conditions with user-definable objective functions based on a genetic algorithm. Int J Prod Res 42:1365–1390. [CrossRef]

- Chen CC, Su PL, Chiou CB, Chiang KT (2011) Experimental investigation of designed parameters on dimension shrinkage of injection molded thin-wall part by integrated response surface methodology and genetic algorithm: A case study. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 26:534–540. [CrossRef]

- Natalini M, Sasso M, Amodio D (2013) Comparison of numerical and experimental data in multi-objective optimization of a thermoplastic molded part. International Polymer Processing 28:84–106. [CrossRef]

- Mukras SMS, Omar HM, Al-Mufadi FA (2019) Experimental-Based Multi-objective Optimization of Injection Molding Process Parameters. Arab J Sci Eng 44:7653–7665. [CrossRef]

- Song Z, Liu S, Wang X, Hu Z (2020) Optimization and prediction of volume shrinkage and warpage of injection-molded thin-walled parts based on neural network. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 755–769. [CrossRef]

- Yang K, Tang L, Wu P (2022) Research on Optimization of Injection Molding Process Parameters of Automobile Plastic Front-End Frame. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen VT, Uyen TMT, Minh PS, Do TT, Huynh TH, Nguyen T, Nguyen VT, Nguyen VTT (2023) Weld Line Strength of Polyamide Fiberglass Composite at Different Processing Parameters in Injection Molding Technique. Polymers (Basel) 15:. [CrossRef]

- Chen WC, Nguyen MH, Chiu WH, Chen TN, Tai PH (2016) Optimization of the plastic injection molding process using the Taguchi method, RSM, and hybrid GA-PSO. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 83:1873–1886. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Cheng G (2016) An Innovative Surrogate-Based Searching Method for Reducing Warpage and Cycle Time in Injection Molding. Advances in Polymer Technology 35:288–297. [CrossRef]

- Lu Y, Huang H (2020) Multi-objective Optimization of Injection Process Parameters Based on EBFNN and NSGA-II. J Phys Conf Ser 1637. [CrossRef]

- Deb D, Jain A, Singh RK (2014) An Evolutionary Many-Objective Optimization Algorithm Using Reference-Point-Based Nondominated Sorting Approach, Part I: Solving Problems With Box Constraints. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 18:577–601. [CrossRef]

- Tanabe R, Ishibuchi H (2019) A niching indicator-based multi-modal many-objective optimizer. Swarm Evol Comput 49:134–146. [CrossRef]

- Dutta S, Mallipeddi R, Das KN (2022) Hybrid selection based multi/many-objective evolutionary algorithm. Sci Rep 12:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Cheng J, Liu Z, Tan J (2013) Multiobjective optimization of injection molding parameters based on soft computing and variable complexity method. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 66:907–916. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Hashimoto S, Takano M, Kubo Y, Aiba S (2020) Multi-objective optimization for minimizing weldline and cycle time using variable injection velocity and variable pressure profile in plastic injection molding. Journal of Advanced Mechanical Design, Systems and Manufacturing 14:3351–3361. [CrossRef]

- Chang H, Sun Y, Wang R, Lu S (2023) Application of the NSGA-II Algorithm and Kriging Model to Optimise the Process Parameters for the Improvement of the Quality of Fresnel Lenses. Polymers (Basel) 15:. [CrossRef]

- Park HS, Nguyen TT (2014) Optimization of injection molding process for car fender in consideration of energy efficiency and product quality. J Comput Des Eng 1:256–265. [CrossRef]

- Kariminejad M, Tormey D, Ryan C, O’Hara C, Weinert A, McAfee M (2024) Single and Multi-Objective Real-Time Optimisation of an Industrial Injection Moulding Process via a Bayesian Adaptive Design of Experiment Approach. Sci Rep 14:1. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Fan X, Guo Y, Liu Z, Ding W (2022) Quality Monitoring and Multi-Objective Optimization of the Glass Fiber-Reinforced Plastic Injection Molded Products. SAE International Journal of Materials and Manufacturing 16:. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Zhang S, Wang Z (2021) Multi-objective optimization of process parameters in plastic injection molding using a differential sensitivity fusion method. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 114:423–449. [CrossRef]

- Zhao G, Li K (2022) Undeterministic analysis and process optimization for short-fiber composite injection molding. Mater Chem Phys 289:126470. [CrossRef]

- Alam K, Kamal MR (2004) Runner balancing by a direct genetic optimization of shrinkage. Polym Eng Sci 44:1949–1959. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes C, Viana JC, Pontes AJ, Gaspar-Cunha A (2008) Setting of the Operative Processing Window in Injection Moulding Using a Multi-Optimization Approach: Experimental Assessment. In: 11th Esaform Conference on Material Forming. Lyon, France.

- Mehta ES, Padhi SN (2023) Performance Analysis of Plastic Injection Molding Using Particle Swarm Based Modified Sequential Quadratic Programming Algorithm Multi Objective Optimization Model. J Theor Appl Inf Technol 101:1053–1066.

- Kitayama S, Tsurita S, Takano M, Yamazaki Y, Kubo Y, Aiba S (2022) Multi-objective process parameters optimization in rapid heat cycle molding incorporating variable packing pressure profile for improving weldline, clamping force, and cycle time. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 120:3669–3681. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Tsurita S, Takano M, Yamazaki Y, Kubo Y, Aiba S (2023) Multi-objective process parameter optimization for minimizing weldline and cycle time using heater-assisted rapid heat cycle molding. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 128:5635–5646. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Matsubayashi A, Takano M, Yamazaki Y, Kubo Y, Aiba S (2022) Numerical optimization of multistage packing pressure profile in plastic injection molding and experimental validation. Polym Adv Technol 33:3002–3012. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Hashimoto S, Takano M, Kubo Y, Aiba S (2020) Simultaneous optimization of variable injection velocity profile and process parameters in plastic injection molding for minimizing weldline and cycle time. Journal of Advanced Mechanical Design, Systems and Manufacturing 14:3351–3361. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Ishizuki R, Takano M, Kubo Y, Aiba S (2019) Optimization of mold temperature profile and process parameters for weld line reduction and short cycle time in rapid heat cycle molding. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 103:1735–1744. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Yokoyama M, Takano M, Aiba S (2017) Multi-objective optimization of variable packing pressure profile and process parameters in plastic injection molding for minimizing warpage and cycle time. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 92:3991–3999. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Yamazaki Y, Takano M, Aiba S (2018) Numerical and experimental investigation of process parameters optimization in plastic injection molding using multi-criteria decision making. Simul Model Pract Theory 85:95–105. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Tamada K, Takano M, Aiba S (2018) Numerical and experimental investigation on process parameters optimization in plastic injection molding for weldlines reduction and clamping force minimization. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 97:2087–2098. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Tamada K, Takano M, Aiba S (2018) Numerical optimization of process parameters in plastic injection molding for minimizing weldlines and clamping force using conformal cooling channel. J Manuf Process 32:782–790. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama S, Miyakawa H, Takano M, Aiba S (2017) Multi-objective optimization of injection molding process parameters for short cycle time and warpage reduction using conformal cooling channel. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 88:1735–1744. [CrossRef]

- Zhai H, Li X, Xiong X, Zhu W, Li C, Wang Y, Chang Y (2023) A method combining optimization algorithm and inverse-deformation design for improving the injection quality of box-shaped parts. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes C, Pontes AJ, Viana JC, Gaspar-Cunha A (2009) Using Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithms in the Optimization of Polymer Injection Molding. Applications of Soft Computing 357–365. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes C, Pontes AJ, Viana JC, Gaspar-cunha A (2015) Multi-Objective Optimization of Gate Location and Processing Conditions in Injection Molding Using MOEAs : Experimental Assessment. EMO 2015 - 8th International Conference on Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization (LNCS 9019) 373–387. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes C, Pontes AJ, Viana JC, Gaspar-Cunha A (2012) Using Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithms for Optimization of the Cooling System in Polymer Injection Molding. Int Polym Proc 27:213–223. [CrossRef]

- Brooks H, Brigden K (2016) Design of conformal cooling layers with self-supporting lattices for additively manufactured tooling. Addit Manuf 11:16–22. [CrossRef]

- Mazur M, Brincat P, Leary M, Brandt M (2017) Numerical and experimental evaluation of a conformally cooled H13 steel injection mould manufactured with selective laser melting. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 93:881–900. [CrossRef]

- van As B, Combrinck J, Booysen GJ, de Beer DJ (2017) Direct metal laser sintering, using conformal cooling, for high volume production tooling. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering 28:170–182. [CrossRef]

- Tuteski O, Kočov A (2018) Conformal cooling channels in injection molding tools – design considerations. Int Sci Congr Mach Technol Mater 12:445–448.

- Konuskan Y, Yılmaz AH, Tosun B, Lazoglu I (2023) Machine learning-aided cooling profile prediction in plastic injection molding. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2957–2968. [CrossRef]

- Zacharski A, Samborski T, Zbrowski A, Kozioł S, Poszwa P (2023) Modular injection mould with a conformal cooling channel for the production of hydraulic filter housings. Technologia i Automatyzacja Montażu 122:48–55. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto S, Kitayama S, Takano M, Kubo Y, Aiba S (2020) Simultaneous optimization of variable injection velocity profile and process parameters in plastic injection molding for minimizing weldline and cycle time. Journal of Advanced Mechanical Design, Systems and Manufacturing 14:3351–3361. [CrossRef]

- Feng QQ, Zhou X (2019) Automated and robust multi-objective optimal design of thin-walled product injection process based on hybrid RBF-MOGA. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 101:2217–2231. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca JH, Jang W, Han D, Kim N, Lee H (2024) Strength and manufacturability enhancement of a composite automotive component via an integrated finite element/artificial neural network multi-objective optimization approach. Compos Struct 327:. [CrossRef]

- Zhai M, Lam YC, Au CK (2009) Runner sizing in multiple cavity injection mould by non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm. Eng Comput 25:237–245. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira I, Weck O De, Saraiva P, Cabral J (2010) Multidisciplinary optimization of injection molding systems. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 621–635. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira I, Cabral JA, Saraiva P, Oliveira MC (2014) A multidisciplinary framework to support the design of injection mold tools. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 49:501–521. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Yan S, Zhong Y, Pan W, Zhao G (2019) Multi-objective optimization of the fiber-reinforced composite injection molding process using Taguchi method, RSM, and NSGA-II. Simul Model Pract Theory 91:69–82. [CrossRef]

- Zhijun Y, Wang H, Wei X, Yan K, Gao C (2019) Multiobjective optimization method for polymer injection molding based on a genetic algorithm. Advances in Polymer Technology 2019. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Qiu Z, Huang Y, Huang W (2021) Overview of injection molding process optimization technology. J Phys Conf Ser 1798. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Hanid MH, Abd Rahim SZ, Gondro J, Sharif S, Al Bakri Abdullah MM, Mohd Zain A, El-Hadj Abdellah A, Mat Saad MN, Wysłocki JJ, Nabiałek M (2021) Warpage optimisation on the moulded part with straight drilled and conformal cooling channels using response surface methodology (RSM), glowworm swarm optimisation (GSO) and genetic algorithm (GA) optimisation approaches. Materials 14:. [CrossRef]

- Shayfull Z, Sharif S, Zain AM, Saad RM, Fairuz MA (2013) Milled groove square shape conformal cooling channels in injection molding process. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 28:884–891. [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Colmenero JM, Rubio-Paramio MA, Marquez-Sevillano J de J, Martin-Doñate C (2018) A new method for the automated design of cooling systems in injection molds. CAD Computer Aided Design 104:60–86. [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Colmenero JM, Martin-Doñate C, Rodriguez-Santiago M, Moral-Pulido F, Rubio-Paramio MA (2019) A new conformal cooling lattice design procedure for injection molding applications based on expert algorithms. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 102:1719–1746. [CrossRef]

- Dimla DE, Camilotto M, Miani F (2005) Design and optimisation of conformal cooling channels in injection moulding tools. J Mater Process Technol 164–165:1294–1300. [CrossRef]

- Chaabene A, Chatti S, Ben Slama M (2021) Optimization of the Cooling of a Thermoplastic Injection Mold. Annals of “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati, Fascicle XII, Welding Equipment and Technology 32:61–70. [CrossRef]

- Kanbur BB, Zhou Y, Shen S, Wong KH, Chen C, Shocket A, Duan F (2022) Metal additive manufacturing of conformal cooling channels in plastic injection molds with high number of design variables. Mater Today Proc 70:541–547. [CrossRef]

- Le Goff R, Garcia D (2011) Multi-objective optimization strategy for the design of injection mold cooling system. Society of Plastics Engineers - EUROTEC 2011 Conference Proceedings.

- Jahan SA, Wu T, Zhang Y, El-Mounayri H, Tovar A, Zhang J, Acheson D, Nalim R, Guo X, Lee WH (2016) Implementation of Conformal Cooling & Topology Optimization in 3D Printed Stainless Steel Porous Structure Injection Molds. Procedia Manuf 5:901–915. [CrossRef]

- Jahan S, Wu T, Shin Y, Tovar A, El-Mounayri H (2019) Thermo-fluid topology optimization and experimental study of conformal cooling channels for 3D printed plastic injection molds. Procedia Manuf 34:631–639. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Li Z, Gu J, Ruan S, Shen C, Wang X (2016) Reducing service stress of the injection-molded polycarbonate window by optimizing mold construction and product structure. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 86:1691–1704. [CrossRef]

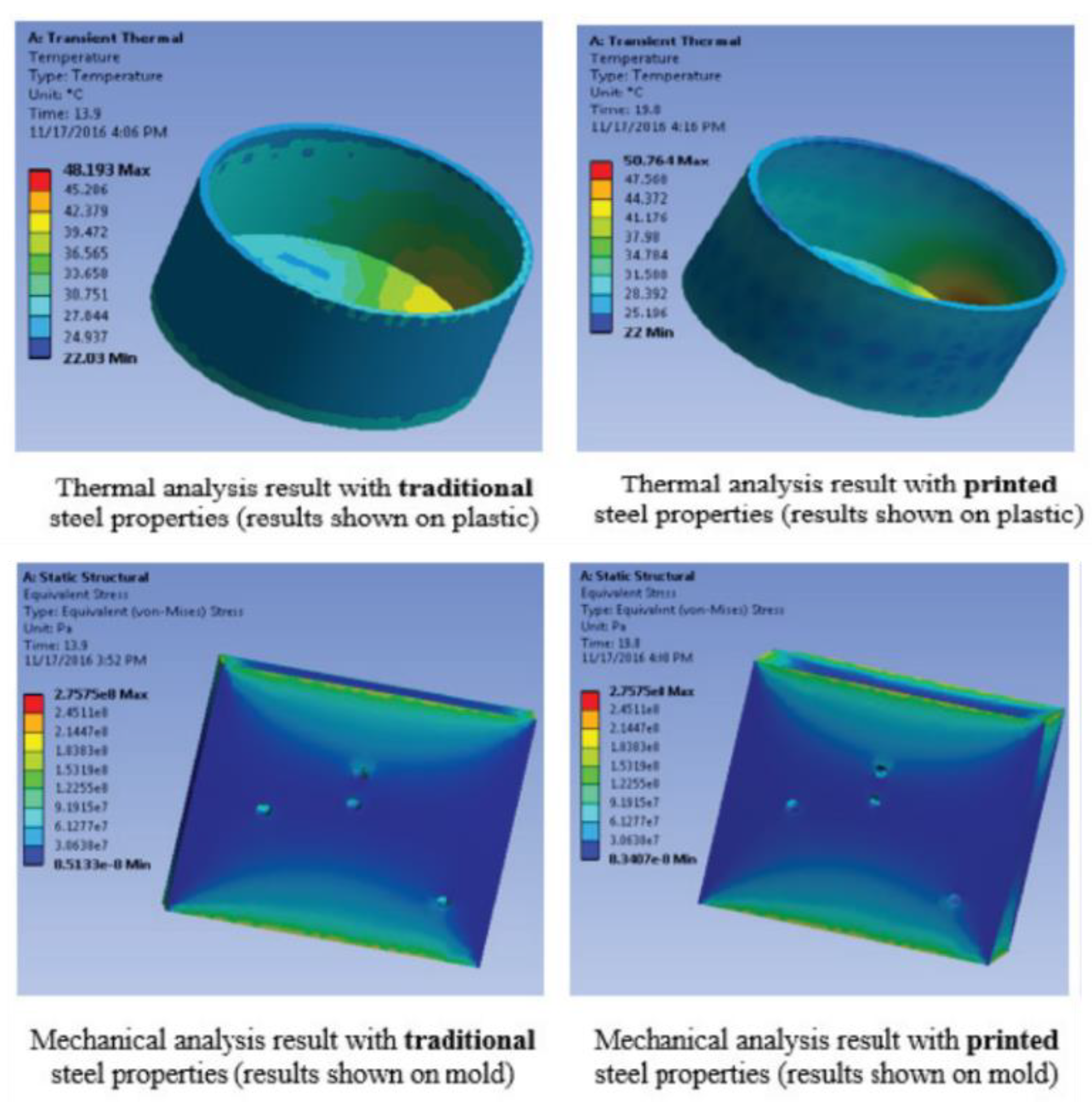

- Silva HM, Rodrigues H (2023) Structural Analysis of Molds with Conformal Cooling Channels: A Numerical Study. Engineering Proceedings 56:295. [CrossRef]

- Kanbur BB, Zhou Y, Shen S, Duan F (2020) Neural network-integrated multiobjective optimization of 3D-printed conformal cooling channels. IEEE Xplore. [CrossRef]

- Hsu FH, Wang K, Huang CT, Chang RY (2013) Investigation on conformal cooling system design in injection molding. Advances in Production Engineering & Management 8:107–115. [CrossRef]

- Saifullah ABM, Masood SH, Sbarski I (2012) Thermal-structural analysis of bi-metallic conformal cooling for injection moulds. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 62:123–133. [CrossRef]

- Jahan SA, Wu T, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Tovar A, Elmounayri H (2017) Thermo-mechanical Design Optimization of Conformal Cooling Channels using Design of Experiments Approach. Procedia Manuf 10:898–911. [CrossRef]

- Shen S, Kanbur BB, Zhou Y, Duan F (2019) Thermal and mechanical analysis for conformal cooling channel in plastic injection molding. Mater Today Proc 28:396–401. [CrossRef]

- Eiamsa-Ard K, Wannissorn K (2015) Conformal bubbler cooling for molds by metal deposition process. CAD Computer Aided Design 69:126–133. [CrossRef]

- Vojnová E (2016) The benefits of a conforming cooling systems the molds in injection moulding process. Procedia Eng 149:535–543. [CrossRef]

- Yadegari M, Masoumi H, Gheisari M (2016) Optimization of cooling channels in plastic injection molding. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research 11:5777–5780.

- Venkatesh G, Ravi Kumar Y, Raghavendra G (2017) Comparison of Straight Line to Conformal Cooling Channel in Injection Molding. Mater Today Proc 4:1167–1173. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Ong YC, Wan Muhamad WM (2024) Optimization Design of Injection Mold Conformal Cooling Channel for Improving Cooling Rate. Processes 12:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Lee C (2023) Design and Optimization of Conformal Cooling Channels for Increasing Cooling Efficiency in Injection Molding. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 13:3253–3271. [CrossRef]

- Kanbur BB, Shen S, Zhou Y, Duan F (2019) Thermal and mechanical simulations of the lattice structures in the conformal cooling cavities for 3D printed injection molds. Mater Today Proc 28:379–383. [CrossRef]

- Godec D, Brnadić V, Breški T (2021) Optimisation of Mould Design for Injection Moulding – Numerical Approach. Tehnicki Glasnik 15:258–266. [CrossRef]

- Silva HM, Noversa T, Rodrigues H, Fernandes L, Pontes A (2021) Sensitivity Analysis of Conformal CCs for Injection Molds : 3D Transient Heat Transfer Analysis. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square]. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Wang X, Gu J, Ruan S, Shen C, Lyu Y, Zhao Y (2018) Topology Optimization for the Design of Conformal Cooling System in Thin-wall Injection Molding Based on BEM. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 94:1041–1059. [CrossRef]

- Marques S, De Souza AF, Miranda J, Yadroitsau I (2015) Design of conformal cooling for plastic injection moulding by heat transfer simulation. Polimeros 25:564–574. [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin K, Wahab MS, Batcha MFM, Shayfull Z, Raus AA, Ahmed A (2017) Cycle time improvement for plastic injection moulding process by sub groove modification in conformal cooling channel. AIP Conf Proc 1885. [CrossRef]

- Simiyu LW, Muiruri PI, Ikua BW, Gacharu SN (2023) Simultaneous Optimization of Product Quality and Productivity for Multi-Factor designs of Circular Cross-Section Conformal Cooling Channels in Injection Molds. Res Sq 0–16. [CrossRef]

- Kanbur BB, Zhou Y, Shen S, Wong KH, Chen C, Shocket A, Duan F (2022) Metal Additive Manufacturing of Plastic Injection Molds with Conformal Cooling Channels. Polymers (Basel) 14:424. [CrossRef]

| Feature/Software | Moldflow | Moldex3D | ANSYS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Injection molding process simulation | Detailed melt flow and cooling analysis | Structural and thermal analysis |

| Filling, Packing, and Cooling | Excellent | Superior | Limited |

| Warpage and Defect Prediction | High accuracy | Very detailed | Moderate |

| Complex Geometry Handling | Moderate | Excellent | Limited |

| Structural and Stress Analysis | Basic | Moderate | Excellent |

| Material Behavior Simulation | Extensive database | Very precise | Advanced mechanical properties |

| Integration with CAD/CAE | Strong | Strong | Extensive (especially with the ANSYS ecosystem) |

| Best Use Case | Process optimization and defect minimization | Complex geometries and cycle time improvement | Structural and thermal performance evaluation |

| Optimization | Step | Type DVs | Objectives | Modelling | Surrogates | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical | Entire | OC | Defects | Experimental | ANN | Ogawa et al. [63] |

| Empirical | Post-Ejec | OC+MCG | Warpage | Moldex3D | -- | Kastelic et al. [77] |

| Complex | Entire | PG | Warpage | Experimental | -- | Lee & Kim [78] |

| DOE | Cooling | CC | Temperature | Moldflow | QRS | Rhee et al. [79] |

| DOE | Fill+Pack. | OC | Shrinkage | Moldflow | Metamodeling | Villarreal-Marroquin et al. [80] |

| Taguchi | Entire | OC | Warpage | Moldex3D | RSM | Nguyen et al. [64] |

| Taguchi | Entire | OC | Overflow | Experimental | ANN | Dejene & Wolla [71] |

| Tag.+GRA | Entire | OC | Warpage | Moldflow | -- | Lin et al. [81] |

| SQP | Filling | RG | Surface def. | Moldflow | Kriging | Ma et al. [66] |

| Other | Entire | OC | Warpage | Moldflow | Kriging | Gao & Wang [72] |

| Other | Entire | OC | Warpage | Moldflow | QRS | Zhang et al. [82] |

| Other | Entire | OC | Warpage | Moldflow | GPR | Xia et al. [83] |

| Other | Entire | OC | Von Mises | M+A | Kriging | Liu et al. [75] |

| Other | Filling | GL | Pressure | Moldex3D | Kriging | Hsu et al. [84] |

| Other | Fill+Pack. | OC | Pressure | Moldflow | Various | Saad et al. [74] |

| PSO | Entire | OC | Von Mises | Moldflow | ANN | Xu et al. [68] |

| PSO | Entire | OC | Warpage | Moldflow | Kriging | Li et al. [65] |

| EA | Entire | OC | Sink marks | Not specified | ANN | Shen et al. [85] |

| EA | Cooling | GL | Von Mises | Moldflow | -- | Kurkin et al. [69] |

| EA | Entire | OC | Weight | Moldex3D | XGBoost | Ma et al. [73] |

| EA+PSO | Entire | RG+OC | Blush defect | Moldflow | ANN | Ardestani et al. [67] |

| ML | Entire | OC | Part weight | Cadmould | ANN | Lockner & Hopmann [70], Lockner et al. [86] |

| ML | Entire | OC | Weld line | Moldex3D | ANN | Baruffa et al. [76],Pieressa et al. [87] |

| Optimization | Step | Type DVs | N. Objs | Modelling | Surrogates | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | -- | Wang et al. [110] |

| Empirical | Ejection | OC | 3 | Moldflow (5) | -- | Fu & Ma [88] |

| Empirical | Cooling | GL+OC+CC | 3 | Moldflow | -- | Al-Hadad & Wang [111] |

| Empirical | Cool.+Pack. | OC | 2 | Moldflow | RSM | Nasir et al. [89] |

| Empirical | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | RSM | Meiabadi et al. [112] |

| Empirical | Entire | OC+GL | 4 | Custom | -- | Trinh [49] |

| Simplex | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | -- | Sherbelis at al. [22] |

| Gradient | Entire | OC+GL | 3 | Moldflow | Kriging | Li & Wang [91] |

| Gradient | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | RSM, RBF | Heidari et al. [93,94] |

| Gradient | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | -- | Hiyane-Nashiro et al. [113] |

| DOE | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | Regression | Rodríguez-Yáñez et al. [114] |

| DOE | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldex3D | -- | Huang et al. [11] |

| Taguchi | Entire | OC | 2 | Experimental | RSM | Lan et al. [115] |

| Taguchi | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | RSM | Ryu et al. [116] |

| Taguchi | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | -- | Idayu et al. [117] |

| Taguchi | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | -- | Ashaari & Amin [118] |

| Taguchi | Fill.+Pack. | OC | 3 | Moldex3D | -- | Vasiliki et al. [119] |

| Taguchi | Fill.+ Cool. | OC | 3 | Moldflow | ANOVA, GRA | Md Ali et al. [120] |

| Taguchi | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | GRA | Wu et al. [121] |

| Taguchi | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldex3D | GRA | Huang et al. [122] |

| Taguchi | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | GRA | Li et al. [97] |

| Taguchi (1) | Entire | OC | 2 | Experimental | -- | Ravikiran et al. [123] |

| RSM | Entire | OC + GG | 5 | Experimental | PCA - GRA | Sreedharan et al. [95] |

| SQP | Entire | PG | 3 | Moldex3D | PR | Park et al. [92] |

| Other | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | GPR | Villarreal-Marroquín et al. [124] |

| Other | Cooling | OC | 2 | Moldex3D | RBF | Chang et al. [125] |

| Other | Entire | OC + PG | 4 | Moldlow (4) | ANOVA | Fonseca et al. [96] |

| Fuzzy | Entire | OC | 5 | Experimental | SQP | Tan & Yuen [126] |

| PSO | Fill.+ Cool. | OC | 3 | Custom | FSA | Zhao et al. [48] |

| PSO | Entire | OC | 3 | Experimental | ANN | Bensingh et al. [127] |

| PSO | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | RSM | Roslan et al. [128] |

| PSO | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | ANN | Lin et al. [129] |

| PSO | Cooling | CC | 6 | Moldex3D (5) | RSM | Cervantes-Vallejo et al. [90] |

| EA | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | -- | Deng et al. [130] |

| EA | Cooling | OC | 2 | Moldflow | -- | Chen et al. [131] |

| EA | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | -- | Natalini et al. [132] |

| EA, SQP | Entire | OC | 2, 3 | Experimental | Kriging | Mukras et al. [133], Mukras [44] |

| EA | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | ANN+SVM | Song et al. [134] |

| EA | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | ANN | Yang et al. [135] |

| EA, EA-PSO | Entire | OC | 2 | Experimental | ANN, RSM | Nguyen et al. [136], Chen et al. [137] |

| Optimization | Step | Type DVs | N.Objs | Modelling | Surrogates | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAO | Pack.+Cool. Cooling, Entire, Fill.+Pack. |

OC | 2, 3 | Moldex3D | RBF | Kitayama et al. [98,144,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163] |

| SAO | Fill.+Pack. | OC | 2 | Moldex3D | RBF | Hashimoto et al. [174] |

| SD | Cooling | OC | 3 | Moldex3D | GPR | Chen et al. [7] |

| MBO | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | GPR + ANN | Jung et al. [104] |

| MOFA | Entire | OC (1) | 2 | Moldflow | ANN | Liu et al. [148] |

| MOPSO | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | ANN | Zhang et al. [102] |

| MOPSO | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | Liu et al. [21] | |

| PSO | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | Kriging | Chen et al. [99] |

| PSO+SQP | Entire | OC | 2 | CATIA | Mehta & Padhi [153] | |

| MPDE | Entire | OC + GG | 3 | Moldflow | Kriging | Wang et al. [105] |

| MOEA | Fill.+Pack. | OC/ OC+GL |

3, 5 | Moldflow | Fernandes et al. [106,152,165,166,167] | |

| MOEA | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | ANN | Feng et al. [62,175] |

| MOEA | Entire | OC | 3 | M+Ab | ANN | Fonseca et al. [176] |

| MOEA/D | Entire | OC + GG | 2 | Moldflow | ANN | C. Wang et al. [100] |

| NSGA-II | Filling | RG+ OC | 3 | Moldflow | Alam & Kamal [151] | |

| NSGA-II | Filling | RG + OC | 5 | Moldflow | Zhai et al. [177] | |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC + RG Geometry |

3 | Moldflow | Ferreira et al. [178,179] | |

| NSGA-II | Entire | RG + OC | 3 | Moldflow | ANN | Cheng at al. [143] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | RSM | Park & Nguyen [146] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | Kriging | Zhao & G. Cheng [138] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 4 | Moldflow | RSM | Tian et al. [103] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | RSM | Li et al. [180] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | PG + OC | 2 | Moldflow | RSM | Zhijun et al. [181] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 2 | Moldflow | ANN | Lu & Huang [139] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 2 | Experimental | ANN | Wang et al. [107] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC (1) | 2 | Moldflow | RSM | Zhao & K. Li [150] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldex3D | ANN | Zhai et al. [164] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 2 | Experimental | Kriging | Chang et al. [145] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | ANN | Guo et al. [109] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC + Gas | 3 | Moldflow | ANN | Guo et al.[109] |

| NSGA-II | Entire | OC | 3 | Moldflow | Bayesian | Zeng et al. [108] |

| NSGA-II | Entire (2) | OC | 2 | Moldflow | GPR | Kariminejad et al. [147] |

| NSGA-III | Entire | OC | 7 | Moldex3D | ANN | Alvarado-Iniesta et al. [101] |

| NSGA-III | Entire | OC | 4 | Moldflow | RSM | Zhou et al. [149] |

| NSGA-III | Entire | OC | 4 | Moldflow | RSM | Zhu et al. [182] |

| Opt. | Type DVs | N. Objs | Modelling | Surrog. | Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA + PSO | OC | 1 | Moldflow | RSM | SO | Mohd Hanid et al. [183] |

| EI | CCC+GG | 1 | M+A | Kriging | SO | Wang et al. [193] |

| Empirical | CCC | 3 | M+A | SO | Saifullah et al. [197] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 3 | Moldex3D | SO | Hsu et al. [196] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 3 | Exp. | SO | Vojnová [201] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 2 | Moldflow | SO | Yadegari et al. [202] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 3 | Moldflow | SO | Venkatesh et al. [203] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 2 | Moldflow | SO | Li et al. [204] | |

| Empirical | DCCC | 3 | Moldex3D | SO | Kirchheim et al. [12] | |

| DOE + TM | CCC | 2 | ANSYS | SO–Ag. | Jahan et al. [198] | |

| EA | CCC | 3 | M+A | SO–Ag. | Mercado-Colmenero et al. [185,186] | |

| EA | CCC | 3 | Moldex3D | RSM | SO–Ag. | Wang & Lee. [205] |

| Empirical | CCC | 3 | Moldflow | SO–Ag. | Dimla et al. [187] | |

| Empirical | CCC+OC | 2 | Moldflow | SO–Ag. | Shayfull et al. [184] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 3 | Exp. | SO–Ag. | Eiamsa-Ard & Wannissorn [200] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 4 | ANSYS | SO–Ag. | Kanbur et al. [206] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 3 | Moldex3D | SO–Ag. | Godec et al. [207] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 2 | ANSYS | SO–Ag. | Silva et al. [208] | |

| SA | CCC | 3 | ANSYS | SO–Ag. | Silva & Rodrigues [194] | |

| ML | CCC | 2 | Moldflow | ANN | SO–Ag. | Gao et al. [42] |

| TM + TO | CCC+Mec | 3 | ANSYS | SO–Ag. | Jahan et al. [191] | |

| TM + TO | CCC | 3 | A+CL | SO–Ag. | Jahan et al. [192] | |

| TO + SLP | CCC | 2 | Custom | SO–Ag. | Li et al. [209] | |

| EA | CCC | 3 | ANSYS | ANN | SO–Ag. | Kanbur et al. [195] |

| Empirical | CCC | 2 | Moldflow | SO–Ag. | Marques et al. [210] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 2 | Moldflow | SO–Ag. | Kamarudin et al [211] | |

| Empirical | CCC+OC | 2 | ANSYS | SO–Ag. | Shen et al. [199] | |

| Empirical | CCC | 3 | Moldflow | SO–Ag. | Chaabene et al. [188] | |

| Grad(TO) | CCC+OC | 3 | COMSOL | SO–Ag. | Wu & Tovar [41] | |

| Taguchi | CCC | 4 | SolidWorks | GRA | SO–Ag. | Simiyu et al. [212] |

| GD | GDCCC | 3 | Moldex3D | SO-Ag. | Wilson et al. [13] | |

| MOEA | CCC | 3 | COMSOL | MO | Kanbur et al. [213] | |

| NSGA-II | CCC+Tc | 2 | M+mF | MO | le Goff et al. [190] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).