1. Introduction

Bioimplants, which are designed to treat, repair, support or replace part of biological structure or function, are revolutionizing healthcare.[

1] By mimicking native state of biological systems, these implants exhibit seamless human integration and mechanical excellence.[

2]

Despite the success of load-bearing bioimplants made from metals and ceramics, which possess mechanical strength, they often require complicated and advanced manufacturing, such as 3D printing scaffold.[

3] The hard implants may necessitate invasive surgical procedure, increasing the risk of infection and patient discomfort.[

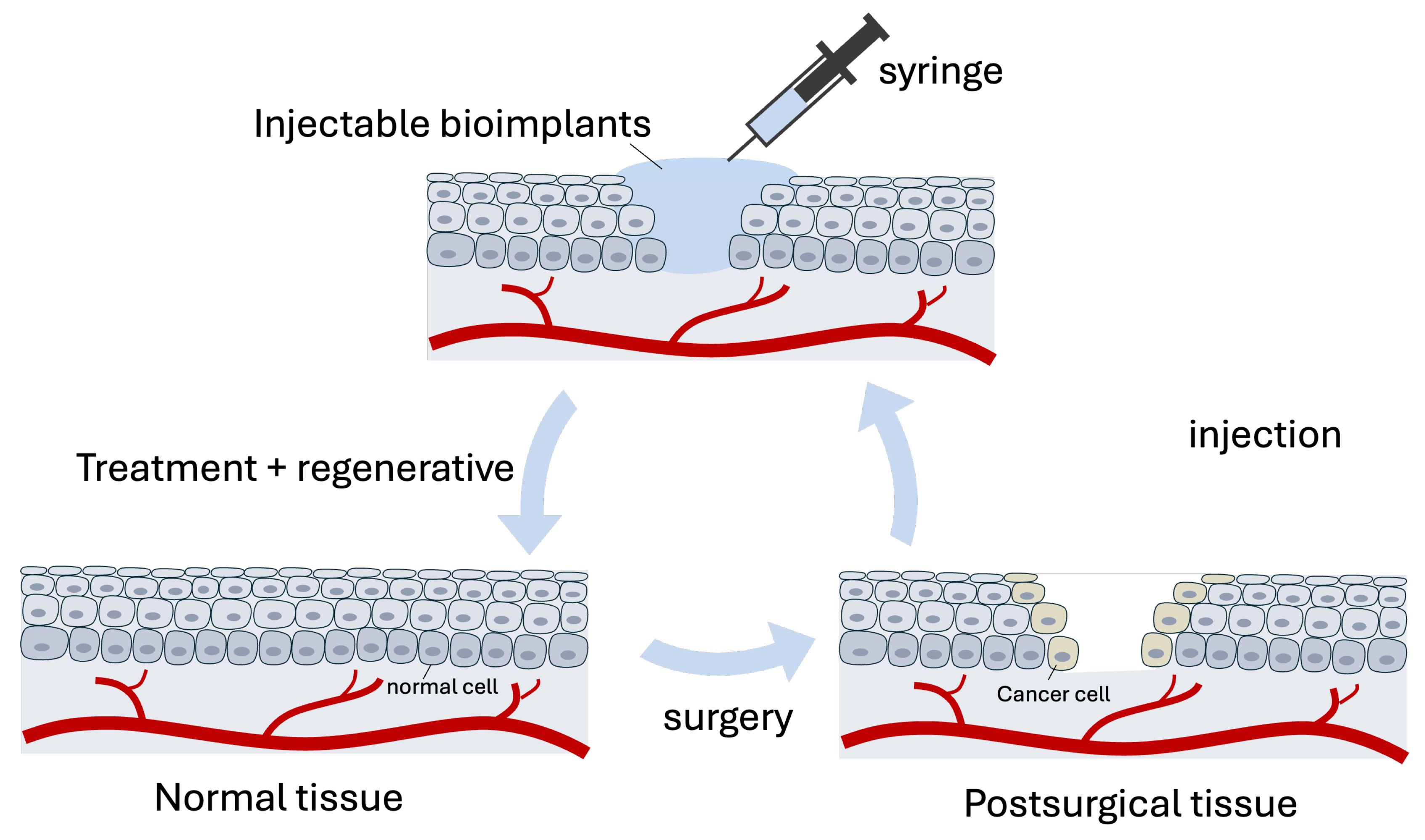

4] These limitations have led to the emergence of injectable bioimplants, a material that can be managed to add room temperature and solidify your response to body temperature injection. Prepared just before application, they are extruded through a syringe and injected at the target site, where they form a scaffold to support tissue regeneration.[

5] The approach is considered as an ideal delivery system of drug, cells or bioactive factors in minimally invasive manner, conforming to the shape of the local tissue. The injectable bioimplants designed to be biodegradable would be degraded into non-toxic smaller units, which are then eliminated from the body via metabolism, eliminating the need for invasive surgery after therapy completion.[

6]

Surgical removal of tumors, such as osteosarcomas or glioblastomas, often results in large tissue defects due to the invasive nature of these malignancies, making self-repair challenging. Injectable bioimplants have been successfully utilized for post-surgical cavity regeneration, including applications in orthopedic and soft tissue repair. [

7][

8][

9] However, this approach alone is insufficient due to the high risk of tumor recurrence. Surgical resection often fails to completely eliminate tumor cells, leaving behind residual cells that pose a risk of local recurrence and distant metastasis. [

10] To address this, post-surgical adjuvant therapies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are commonly employed. However, these treatments come with severe side effects, including nausea, hair loss, immunosuppression, and nephrotoxicity, which can further hinder tissue repair and regeneration. Therefore, simultaneously eliminating residual tumor cells and promoting post-surgical tissue repair is crucial. Injectable bioimplants offer a promising dual approach solution to achieve both objectives.

This review explores the application of injectable bioimplants as dual-purpose materials in both tissue engineering and cancer treatment. By examining various materials utilized in these fields, we seek to highlight the potential of combining therapeutic interventions with regenerative strategies. (

Figure 1) This dual approach not only impose cancer treatment but also promotes the restoration of normal tissue function, offering a comprehensive solution to complex medical conditions.

2. Injectable Bioimplants for Tissue Engineering

Tissue engineering (TE) aims to restore defective tissues or organs by modifying damaged cells or tissues. Since the first concept of TE was proposed for organ replacement, a variety of materials have been developed to meet the requirement of TE. These materials are broadly categorized into natural and synthetic types. Natural materials, such as chitosan, gelatin, collagen, cellulose, and alginates, offer high biocompatibility and biodegradability. Their structural similarity to native extracellular matrices facilitates cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, making them widely used in TE. On the other hand, synthetic materials, prepared by chemical processes, include polylactide-co-glycolide (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), polylactic acid (PLA), fibronectin, and polyurethane. The tunable nature allows customization of mechanical properties and degradation rates to meet specific TE requirement.[

11]

In the realm of hard tissue repair, injectable bone cements have become a cornerstone. These materials, typically comprising a mixture of powder and liquid components, solidify upon administration to fill fracture sites, thereby providing essential mechanical support.[

12] Common types include acrylic bone cements (ABCs), calcium phosphate cements (CPCs), and calcium sulfate cements (CSCs).[

13][

14] [

15] Recent advancements have focused on enhancing the mechanical strength and biological performance of these cements by incorporating bioactive agents, nanoparticles, and growth factors, thereby improving their clinical efficacy.[

16][

17]

For soft tissue engineering, injectable hydrogels have gained significant attention due to their unique biomimetic properties. Composed of crosslinked hydrophilic polymers, these hydrogels retain substantial amounts of water, mimicking the natural extracellular matrix.[

18] The porous network facilitates the encapsulation and sustained release of therapeutic agents, including drugs, proteins, and cells, thereby promoting tissue repair and regeneration.[

19] A notable advancement in this field is the development of self-healing injectable hydrogels.[

20] These hydrogels have the capacity to restore their original structure and mechanical properties after damage. This feature allows the broken hydrogels to regenerate the integral network and ensures functionality in dynamic physiological environments.[

21] For instance, Zhang et al. proposed a chitosan based dynamic hydrogel composed of chitosan and benzaldehydes functionalized poly(ethylene glycol) (DF-PEG). The aldehyde groups of DF-PEG and the amino groups in chitosan form Schiff base linkages, which endowed the self-healing ability. Upon mixing DF-PEG and chitosan, hydrogels were generated within one minute.[

22]

Hydrogels loaded with biological factors is exploited for local drug delivery, resulting in increased retention, more sustained effective dosage, and reduction of off target side effect. The integration of functional nanoparticles into hydrogel networks has expanded their utility. Magnetic nanoparticles, when embedded within hydrogels, confer responsiveness to external magnetic fields.[

23] These magnetic hydrogels are prepared by mixing Fe3O4 nanoparticles into chitosan solution, followed by adding DF-PEG into the ferrofluid. The gelation process takes less than 2 minutes, resulting in a hydrogel capable of recovering its structure after mechanical disruption. The presence of uniformly distributed magnetic nanoparticles allows the hydrogel to be manipulated under an external magnetic field. Moreover, when subjected to an alternating magnetic field (AMF), the embedded Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles generate localized heat, which can be utilized to induce hyperthermia for cancer therapy or to stimulate cellular activities. Studies have demonstrated that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) encapsulated within such magnetic hydrogels enhanced osteogenic differentiation when exposed to nanoparticle-generated heat, compared to conventional direct heating methods by metal bath.[

24]

Overall, injectable bioimplants have been extensively studied for tissue engineering, offering solution for both hard and soft tissue.Their capacity to incorporate biological factors and nanocomposites endows them with additional functional properties, such as responsiveness to external stimuli. Collectively, recent advancements have led to the development of multifunctional composite bioimplants, paving the way for more effective tissue engineering therapies.

3. Injectable Bioimplants for Cancer Therapy

Injectable bioimplants have emerged as a promising approach in cancer therapy, enabling localized and sustained treatment modalities. These systems utilize various materials to deliver therapies such as chemotherapy, thermotherapy, immunotherapy, and combination treatments directly to tumor sites. Microparticles, typically ranging from 1 to 1,000 micrometers in size, have been applied for cancer therapy. For example, researchers have engineered microhydrogels that serve as microwave-sensitive agents, incorporating anti-cancer drugs and magnetic nanoparticles (Fe

3O

4@DOX/CAM) for multimodal treatment and imaging.[

25] In this system, calcium alginate microhydrogels act as microwave susceptible agent. Upon microwave irradiation, the embedded Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles generate localized heating, enhancing drug release and therapeutic efficacy. In vivo studies demonstrated that intratumoral injection of this composite combined with microwave thermotherapy and sustained chemotherapy, resulting in suppressed tumor growth. Additionally, the magnetic nanoparticles facilitated T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during treatment, allowing for real-time monitoring of therapeutic progress.

Nanoparticles (NPs) offer unique advantages in multifunctional cancer treatment due to their ability to deliver therapeutic agents directly to tumor sites. However, studies have demonstrated that the clinical application of nanoparticles (NPs) in cancer therapy faces significant challenges, primarily due to low bioavailability. A meta-analysis revealed that less than 0.7% of administered NPs reach solid tumors, leading to suboptimal therapeutic effects and potential side effects.[

26] To address this limitation, incorporating NPs into scaffolds has become a prevalent strategy. Hydrogels, in particular, are widely used as scaffolds in cancer treatment. These hydrogels can be engineered with various components and mechanical properties. For example, by loading hydrogels with anti-cancer drugs, the resulting hybrid systems can achieve localized chemotherapy, enhancing drug concentration at the tumor site while minimizing systemic exposure.[

27] Additionally, hydrogels can be integrated with photothermal agents or photosensitizers, enabling photothermal therapy (PTT) or photodynamic therapy (PDT). In PTT, the hydrogel-embedded photothermal agents convert light energy into heat upon irradiation, inducing localized hyperthermia that selectively kills cancer cells.[

28] In PDT, photosensitizers within the hydrogel generate reactive oxygen species upon light exposure, leading to targeted cancer cell destruction.[

29] Therefore, by combining NPs with hydrogels, these hybrid systems can enhance the retention and controlled release of therapeutic agents, improve targeting efficiency, and reduce off-target effects, thereby offering a multifaceted approach to cancer therapy.

In recent years, hydrogels have been extensively studied for their potential in cancer immunotherapy. These injectable bioimplants can be engineered to provide controlled release of immunotherapeutic agents—including checkpoint inhibitors, stimulatory adjuvants, cancer antigens, and adoptive T cells—thereby enhancing treatment outcomes when applied to solid tumors or resection sites. This approach addresses traditional limitations by improving delivery kinetics, enhancing patient response profiles, and reducing side effects. The self-assembling nature of DNA has facilitated the development of injectable DNA hydrogels.[

30] For instance, DNA hydrogels containing cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) motifs can stimulate innate immunity through Toll-like receptors. In one study, ethylenediamine-conjugated cationized ovalbumin (ED-OVA) was complexed within a DNA hydrogel, allowing for sustained release. Following intratumoral injection, this hydrogel formulation effectively delayed the growth of OVA-expressing EG7 tumors in mice.[

31]

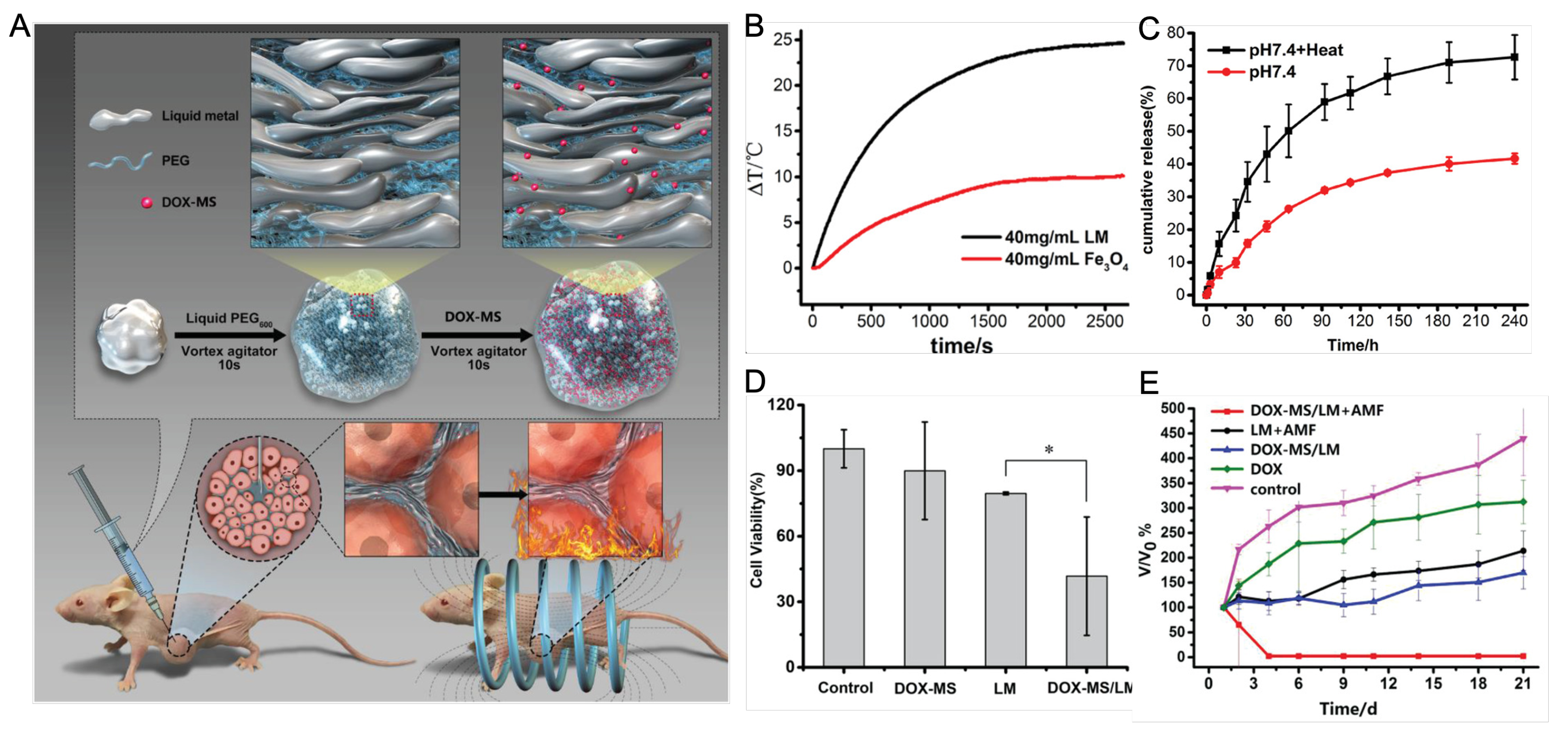

Advancements in cancer therapy have introduced innovative bioimplants designed to enhance treatment efficacy.[

32] Researchers have developed bioimplants utilizing liquid metals, specifically gallium–indium eutectic alloys, which remain fluid at room temperature. These materials possess self-healing properties, water-like fluidity, and biocompatibility.[

33] By incorporating doxorubicin-loaded mesoporous silica into PEGylated liquid metal, a hybrid platform has been created. (

Figure 2) This platform combines the chemotherapeutic effects of doxorubicin with magnetic hyperthermia of the liquid metal, eliminating tumors in MCF-7 bearing mice.[

34]

Recent research has focused on developing multifunctional bioimplants that offer combinational therapeutic effects. Studies have shown that integrating immunotherapy with other treatments—such as chemotherapy, phototherapy, and radiotherapy—can provide synergistic effects, leading to improved therapeutic outcomes for various malignancies. For instance, combining phototherapy with immunotherapy has been found to prevent tumor metastasis and recurrence.[

35] In summary, the development of injectable bioimplants, particularly those that are multifunctional, represents a promising advancement in cancer therapy. These bioimplants, through combinational therapeutic approaches, have the potential to significantly improve treatment efficacy and patient outcomes.

Figure 2.

Figure 2 (A) Schematic of liquid metal based injectable bioimplants. PEGylated liquid metal was loaded with doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded mesoporous silica (DOX-MS). After injection into tumor bearing mice, this hybrid bioimplant platform achieved pH/AFM dual stimuli-responsive drug release and magnetic thermochemotherapy. (B) Comparison of heat generation of liquid metal (LM) and iron oxide nanoparticle (Fe3O4) under alternating magnetic field (AMF. (C) cumulative drug release with or without exposure to AMF. (D) Cytotoxicity of cells treated with DOX-MS alone, LM alone or DOX-MS/LM. (E) relative tumor volume change after treating with different conditions in the nude mice xenografted model of breast cancer cells (MCF-7). Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2019, John Wiley and Sons.[

36]

Figure 2.

Figure 2 (A) Schematic of liquid metal based injectable bioimplants. PEGylated liquid metal was loaded with doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded mesoporous silica (DOX-MS). After injection into tumor bearing mice, this hybrid bioimplant platform achieved pH/AFM dual stimuli-responsive drug release and magnetic thermochemotherapy. (B) Comparison of heat generation of liquid metal (LM) and iron oxide nanoparticle (Fe3O4) under alternating magnetic field (AMF. (C) cumulative drug release with or without exposure to AMF. (D) Cytotoxicity of cells treated with DOX-MS alone, LM alone or DOX-MS/LM. (E) relative tumor volume change after treating with different conditions in the nude mice xenografted model of breast cancer cells (MCF-7). Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2019, John Wiley and Sons.[

36]

4. Dual Functions of Injectable Bioimplants for Regeneration and Treatment

Innovative therapies now aim to address both tumor eradication and tissue regeneration simultaneously. This approach is particularly relevant for conditions like osteosarcoma, which is often not sensitive to standard treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Traditional approaches to managing bone tumors involve a two-step process. First, residual tumors are restrained. Second, bone defects are reconstructed. Surgical resection often failed to completely remove tumors, leading to a high risk of postoperative recurrence. Moreover, bone defects resulting from surgery do not naturally heal, necessitating interventions that concurrently support tissue regeneration and eliminate remaining cancer cells.[

36] In addition, the tumor microenvironment is a crucial factor to consider. Surgical resection can alter the tumor microenvironment, suppressing anti-tumor immunity and increasing the likelihood of cancer cells entering circulation. Furthermore, the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) following radiotherapy and chemotherapy induces damage to normal cells, triggering apoptosis, inflammatory responses, and fibrosis. This, in turn, leads to chronic inflammation, which can further promote tumorigenesis. Multifunctional injectable bioimplants have been developed to tackle tumor-associated bone defects following surgical resection. By incorporating both growth factors and anticancer drugs, these bioimplants serve dual purposes: they facilitate soft tissue regeneration and target residual cancer cells. In this regard, the “two birds, one stone” strategy is designed to prevent tumor recurrence while promoting new tissue formation.

Various bioimplants have been developed. For example, Cai et al. proposed a closed loop hydrogel composed of methotrexate (MTX) loaded mesoporous nanoparticle (MBGN), gelatin and chondroitin sulfate (OCS). After injection, the hydrogel filled into the irregular shape of postoperative region. In the early stage, the hydrogel served as therapeutic platform to deliver nanoparticles to tumor cells, which subsequently released MTX in tumor cells. In the late stage, the hydrogel transitioned into regenerative scaffolds for long term osteogenesis, while nanoparticles gradually released bioactive ions to promote bone formation. In the orthotopic osteosarcoma postoperative mice model, the hydrogel demonstrated tumor suppression, reduced metastasis, and enhanced bone integrity. Additionally, the long term osteogenesis and biosafety were validated in a non-tumor calvarial bone defects rat model.[

37] Beyond drug release, hydrogel platform integrate other therapeutic strategies to achieve tumor ablation and tissue regeneration. For example, an injectable bifunctional hydrogel (denoted “OSA-CS-PHA-DDP”) was synthesized from sodium alginate (OSA) and chitosan (CS), which was then loaded with cisplatin (DDP) and polydopamine (PDA). In tumor bearing mice model, this hydrogel effectively inhibited tumor growth through the combined photothermal effect of PDA and the chemotherapeutic action of DDP. Meanwhile, in a bone defect rabbit model, PDA nanoparticles enhanced osteogenesis, leading to superior bone tissue formation compared to a blank hydrogel lacking PDA particles.[

38]

Nano-implants have led to the development of nanoparticle-infused scaffolds that integrate therapeutic and regenerative functions. have led to the development of nanoparticle-infused scaffolds that integrate therapeutic and regenerative functions.[

39] Upon injection into tumor-bearing rabbits, the PMMA-Fe

3O

4 transitions to a solid state, conforming to the irregular contours of the bone defect and providing essential mechanical support for recovery. When subjected to an alternating magnetic field (AMF), the embedded Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles generate localized heat, effectively ablating bone tumors without causing significant side effects. This dual-function approach not only ensures structural integrity but also offers a minimally invasive method for targeted tumor treatment and bone regeneration. In another example, nanoformulations enable bioimplants to promote wound healing.[

40] These injectable nano-implants consist of a polymer matrix loaded with allantoin and copper oxide (CuO) nanosheets. Allantoin facilitates wound healing by reducing skin irritation and exerting anti-inflammatory effects, while CuO nanosheets serve as photothermal agents. Additionally, the released Cu ions contribute to tissue regeneration by enhancing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, activating copper-dependent enzymes, and promoting integrin expression. When these CuO-loaded polymeric hydrogels were injected into B16–F10 tumor-bearing female BALB/c mice, they effectively suppressed tumor growth compared to unloaded hydrogels. Furthermore, in a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)-infected subcutaneous abscess murine model, these hydrogels, under laser irradiation, significantly reduced bacterial growth and minimized inflammatory exudates.

In summary, injectable bioimplants represent a versatile and effective approach for applications requiring both cancer treatment and tissue regeneration. Ongoing research and clinical trials are expected to further refine these materials, expanding their therapeutic potential across various medical disciplines.

5. Future Perspective

The primary advantage of injectable bioimplants is less invasive, which comfort patients. This is particularly advantageous especially when the target sites are difficult to access, as it avoids surgery, minimizes scar formation and reduces the risk of infection.[

41] Despite these advantages, the necessity for these biomaterials to be in a liquid or gel state to pass through a needle limits the choice of materials. Suitable materials must not only balance low viscosity for injectability with appropriate rheological properties, but also provide desired biological functions.[

42] Moreover, the potential risk associated with these bioimplants warrant careful consideration. One notable concern is the possibility of material migration from the target site, especially when the injectable components are too soft or lack sufficient structural integrity. Such migration can lead to unintended consequences. If the material moves near critical structures like blood vessels, it may increase the risk of complications such as stroke. Ensuring the mechanical stability and appropriate viscosity of injectable materials is essential to prevent displacement and maintain therapeutic efficacy.[

43]

The future of injectable bioimplants lies in personalized treatment, tailoring materials to meet the specific requirement of each disease conditions. For example, bone repair need materials that provide prolonged mechanical support due to the extended healing period, while breast tissue reconstruction require modulus of scaffolds that closely mimic the native tissue. While significant progress has been made in bone-related applications, similar strategies can also be extended to other areas, including breast and oral/facial engineering. However, special attention must be taken when selecting materials, as certain materials, like hyaluronic acid, widely used for their biocompatibility and regenerative properties, may inadvertently promote tumor growth. Due to the aforementioned challenges, research on injectable bioimplants remains limited, as injectable hydrogels often lack sufficient mechanical properties. While bone cement offers structural support, its ability to incorporate tumor therapy is constrained by its limited drug-loading capacity. Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a powerful tool in the design and optimization of bioimplants, enabling rapid prediction and refinement of material properties while expanding the available material space. By leveraging existing data, materials with specific chemical and physical properties can be systematically developed and tested. The resulting data is then integrated into machine learning pipelines to assist in designing or optimizing materials with targeted functions. [

44]

In one study, AI was employed to learn structure–property relationships, enhancing the understanding of hydrogel-forming capabilities and guiding the identification of potential gelators. By analyzing 71 nucleoside derivative structures obtained from published literature—using 4,175 molecular descriptors—the optimal machine learning model selected 24 nucleotide derivatives, two of which were experimentally validated as hydrogel-forming agents.[

45] This AI-driven approach significantly accelerates the development of bioimplants with tailored properties and novel functionalities.

Beyond material design, AI has also been useful in unraveling complex biological interactions by identifying patterns that conventional methods often overlook. [

46] Biocompatibility and biosafety are critical considerations, as some bioimplants—despite being designed for safety—may elicit unintended immune responses or have unforeseen long-term effects. AI holds the potential to address these challenges by guiding the development of bioimplants that seamlessly integrate with host tissues.[

47] Machine learning algorithms can analyze vast datasets to predict how specific materials will behave in various biological environments, facilitating the design of bioimplants optimized for individual patient needs. For example, AI-driven analysis of genomic and proteomic data can help identify potential allergies to specific bioimplant materials, enabling the selection of suitable alternatives.[

48] This personalized approach not only enhances therapeutic outcomes but also reduces the risk of adverse reactions. Moreover, AI contributes to the development of bioimplants that align with patient-specific anatomical and physiological requirements, paving the way for highly effective and customized medical solutions.

From clinical perspective, the injectability of these bioimplants offers numerous advantages. Firstly, they minimize patient discomfort and the risk of infection by avoiding incisions and wound exposure associated with traditional procedure. Secondly, they shorten the duration of intervention and accelerates postoperative recovery. Thirdly, they reduce treatment costs by excluding utilization of instrument associated with invasive procedure.[

13] Despite these advantages, several challenges persist in translating injectable bioimplants from the laboratory to clinical practice. Biocompatibility and Biosafety are most important consideration. While designed for safety, some bioimplants may trigger undesired reactions or have unforeseen effects over time. Moreover, animal models often fail to accurately predict human responses, especially when addressing rare or new cases. To overcome these challenges, a deeper understanding of their interactions with biological systems is crucial. The knowledge will guide the development of bioimplants that integrate with host tissues.[

47]

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the integration of injectable bioimplants into cancer therapy and tissue regeneration has shown significant promise. Among them, injectable hydrogel have gained interest as versatile platform for localized and sustained drug delivery, effectively incorporating various therapeutic agents such as growth factors and nanoparticles to enhance cell proliferation and tissue repair. Their injectability facilitates minimally invasive administration and in situ gelation, ensuring precise delivery and spatial confinement of therapeutics. Notably, the development of bifunctional biomaterials that simultaneously inhibit tumor growth and promote tissue regeneration offers a dual therapeutic approach, potentially improving clinical outcomes and patient quality of life. However, further research is necessary to optimize these systems for widespread clinical application, addressing challenges such as biocompatibility, biosafety, mechanical properties, and controlled release kinetics and biodegradability. AI is poised to transform the field of bioimplants by providing sophisticated tools for design, optimization, and personalization. As AI technologies continue to evolve, their integration into bioimplant development is expected to lead to more effective and tailored therapeutic solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing, D.W.; review and editing, L.S.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sumayli, A. Recent trends on bioimplant materials: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 46, 2726–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.; Zahedi, A.; Ismail, S.; Fernando, W.; Ikumapayi, O. 3D-printed biomimetic bone implant polymeric composite scaffolds. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2023, 126, 4259–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.M.B.; Ng, S.H.; Yoon, Y.J. A review on 3D printed bioimplants. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 2015, 16, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijer, R.; Jansen, E.J.; Emans, P.J.; Bulstra, S.K.; Riesle, J.; Pieper, J.; Grainger, D.W.; Busscher, H.J. Assessing infection risk in implanted tissue-engineered devices. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 5148–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretlow, J.D.; Young, S.; Klouda, L.; Wong, M.; Mikos, A.G. Injectable biomaterials for regenerating complex craniofacial tissues. Advanced Materials 2009, 21, 3368–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Kaur, J.; Lahooti, B.; Varahachalam, S.P.; Jayant, R.D.; Joshi, A., Drug-releasing nano-bioimplants: from basics to current progress. In Engineered Nanostructures for Therapeutics and Biomedical Applications; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 273–295.

- Al-Shalawi, F.D.; Mohamed Ariff, A.H.; Jung, D.W.; Mohd Ariffin, M.K.A.; Seng Kim, C.L.; Brabazon, D.; Al-Osaimi, M.O. Biomaterials as implants in the orthopedic field for regenerative medicine: metal versus synthetic polymers. Polymers 2023, 15, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, E.J.; Takata, T.; Abiko, Y.; Okano, T.; Green, D.W.; Shimono, M.; Jung, H.S. Bio-implant as a novel restoration for tooth loss. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Botija, C.; Bagó, J.R.; Llucià-Valldeperas, A.; Vallés-Lluch, A.; Castells-Sala, C.; Martínez-Ramos, C.; Fernández-Muiños, T.; Chachques, J.C.; Pradas, M.M.; Semino, C.E. Engineered 3D bioimplants using elastomeric scaffold, self-assembling peptide hydrogel, and adipose tissue-derived progenitor cells for cardiac regeneration. American journal of translational research 2014, 6, 291. [Google Scholar]

- Ceyhan, Y.; Garcia, N.M.G.; Alvarez, J.V. Immune cells in residual disease and recurrence. Trends in Cancer 2023, 9, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeeb, A.E.; Salah, S.; Elkasabgy, N.A. Biomaterials for tissue engineering applications and current updates in the field: a comprehensive review. Aaps Pharmscitech 2022, 23, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir-Oğuz, Ö.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Loca, D. Injectable bone cements: What benefits the combination of calcium phosphates and bioactive glasses could bring? Bioactive materials 2023, 19, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mîrț, A.L.; Ficai, D.; Oprea, O.C.; Vasilievici, G.; Ficai, A. Current and future perspectives of bioactive glasses as injectable material. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnan, B.; Bondi, M.; Maluta, T.; Samaila, E.; Schirru, L.; Dall’Oca, C. Acrylic bone cement: current concept review. Musculoskeletal surgery 2013, 97, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.H.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.; Bao, C.; Chen, Q.; Weir, M.D.; Chow, L.C.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X.; Reynolds, M.A. Calcium phosphate cements for bone engineering and their biological properties. Bone research 2017, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Cai, P.; Bian, M.; Yu, J.; Xiao, L.; Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Han, G.; Xiang, X. Injectable and high-strength PLGA/CPC loaded ALN/MgO bone cement for bone regeneration by facilitating osteogenesis and inhibiting osteoclastogenesis in osteoporotic bone defects. Materials Today Bio 2024, p. 101092.

- Vorndran, E.; Geffers, M.; Ewald, A.; Lemm, M.; Nies, B.; Gbureck, U. Ready-to-use injectable calcium phosphate bone cement paste as drug carrier. Acta biomaterialia 2013, 9, 9558–9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertici, V.; Pin-Barre, C.; Rivera, C.; Pellegrino, C.; Laurin, J.; Gigmes, D.; Trimaille, T. Degradable and injectable hydrogel for drug delivery in soft tissues. Biomacromolecules 2018, 20, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Nan, D.; Jin, H.; Qu, X. Recent advances of injectable hydrogels for drug delivery and tissue engineering applications. Polymer Testing 2020, 81, 106283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, P.; Diba, M.; Mooney, D.J.; Leeuwenburgh, S.C. Self-healing injectable hydrogels for tissue regeneration. Chemical Reviews 2022, 123, 834–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumon, M.M.H.; Akib, A.A.; Sultana, F.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Niloy, M.S.; Shakil, M.S.; Roy, C.K. Self-healing hydrogels: Development, biomedical applications, and challenges. Polymers 2022, 14, 4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tao, L.; Li, S.; Wei, Y. Synthesis of multiresponsive and dynamic chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled release of bioactive molecules. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 2894–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.; Tao, L.; Li, S.; Wei, Y. A magnetic self-healing hydrogel. Chemical Communications 2012, 48, 9305–9307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Wang, X.; Tao, L.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Effect of nanoheat stimulation mediated by magnetic nanocomposite hydrogel on the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Science China Life Sciences 2018, 61, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Xie, W.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhao, L. Drug-loaded magnetic microhydrogel as microwave susceptible agents for cancer multimodality treatment and MR imaging. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 2018, 14, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.C. Principles of nanoparticle delivery to solid tumors. BME frontiers 2023, 4, 0016. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.M.; Jung, Y.L.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, D.S.; Thambi, T. Injectable hydrogel imbibed with camptothecin-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles as an implantable sustained delivery depot for cancer therapy. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2023, 636, 328–340. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.S.; Chen, Z.; Lu, Z.M.; Dong, J.H.; Wu, J.H.; Gao, J.; Deng, D.; Li, M. Multifunctional hydrogels based on photothermal therapy: A prospective platform for the postoperative management of melanoma. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 371, 406–428. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, C.; Tian, R.; Sun, T.; Zhang, W.; Chang, J.; Wang, H. An injectable hydrogel co-loading with cyanobacteria and upconversion nanoparticles for enhanced photodynamic tumor therapy. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2021, 201, 111640. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa, M.; Ogawa, K.; Umeki, Y.; Mohri, K.; Kawasaki, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Takahashi, N.; Kusuki, E.; Takahashi, R.; Takahashi, Y. Injectable, self-gelling, biodegradable, and immunomodulatory DNA hydrogel for antigen delivery. Journal of controlled release 2014, 180, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Umeki, Y.; Mohri, K.; Kawasaki, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Takahashi, R.; Takahashi, Y.; Takakura, Y.; Nishikawa, M. Induction of potent antitumor immunity by sustained release of cationic antigen from a DNA-based hydrogel with adjuvant activity. Advanced Functional Materials 2015, 25, 5758–5767. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, D.G.; Young, S.; Hartgerink, J.D. Advances in immunotherapy delivery from implantable and injectable biomaterials. Acta biomaterialia 2019, 88, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Fan, S.; Chan, H.; Qiao, Z.; Qi, J.; Wu, Z.; Yeo, J.C.; Lim, C.T. Liquid metal functionalization innovations in wearables and soft robotics for smart healthcare applications. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34, 2309989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xie, W.; Gao, Q.; Yan, H.; Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Liaw, B.; Guo, Z.; Gao, F.; Yin, L. Non-magnetic injectable implant for magnetic field-driven thermochemotherapy and dual stimuli-responsive drug delivery: transformable liquid metal hybrid platform for cancer theranostics. Small 2019, 15, 1900511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima-Sousa, R.; Alves, C.G.; Melo, B.L.; Costa, F.J.; Nave, M.; Moreira, A.F.; Mendonça, A.G.; Correia, I.J.; de Melo-Diogo, D. Injectable hydrogels for the delivery of nanomaterials for cancer combinatorial photothermal therapy. Biomaterials Science 2023, 11, 6082–6108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.; Han, R.; Wu, Y.; Qian, Z. Review of a new bone tumor therapy strategy based on bifunctional biomaterials. Bone research 2021, 9, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, M.; Li, X.; Xu, M.; Zhou, S.; Fan, L.; Huang, J.; Xiao, C.; Lee, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, L. Injectable Tumor Microenvironment-modulated hydrogels with enhanced Chemosensitivity and Osteogenesis for Tumor-Associated bone defects closed-Loop Management. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 450, 138086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wu, J.; Jia, Z.; Tang, P.; Sheng, J.; Xie, C.; Liu, C.; Gan, D.; Hu, D.; Zheng, W. An injectable, bifunctional hydrogel with photothermal effects for tumor therapy and bone regeneration. Macromolecular bioscience 2019, 19, 1900047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Liang, B.; Zheng, Y.; Exner, A.; Kolios, M.; Xu, T.; Guo, D.; Cai, X.; Wang, Z.; Ran, H. PMMA-Fe3O4 for internal mechanical support and magnetic thermal ablation of bone tumors. Theranostics 2019, 9, 4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati-Siahmazgi, V.; Abbaszadeh, S.; Musaie, K.; Eskandari, M.R.; Rezaei, S.; Xiao, B.; Ghorbani-Bidkorpeh, F.; Shahbazi, M.A. NIR-Responsive injectable hydrogel cross-linked by homobifunctional PEG for photo-hyperthermia of melanoma, antibacterial wound healing, and preventing post-operative adhesion. Materials Today Bio 2024, 26, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Karkanitsa, M.; Christman, K.L. Design and translation of injectable biomaterials. Nature Reviews Bioengineering 2024, 2, 810–828. [Google Scholar]

- Omidian, H.; Wilson, R.L.; Dey Chowdhury, S. Injectable Biomimetic Gels for Biomedical Applications. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béduer, A.; Bonini, F.; Verheyen, C.A.; Genta, M.; Martins, M.; Brefie-Guth, J.; Tratwal, J.; Filippova, A.; Burch, P.; Naveiras, O. An injectable meta-biomaterial: from design and simulation to in vivo shaping and tissue induction. Advanced Materials 2021, 33, 2102350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meyer, T.A.; Ramirez, C.; Tamasi, M.J.; Gormley, A.J. A user’s guide to machine learning for polymeric biomaterials. ACS Polymers Au 2022, 3, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wen, Y.; Wang, K.; Ding, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Xie, L.; Xu, H.; Zhao, H. Developing a machine learning model for accurate nucleoside hydrogels prediction based on descriptors. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mozafari, M. How artificial intelligence shapes the future of biomaterials? Next Materials 2025, 7, 100381. [Google Scholar]

- Westwood, L.; Nixon, I.J.; Emmerson, E.; Callanan, A. The road after cancer: biomaterials and tissue engineering approaches to mediate the tumor microenvironment post-cancer treatment. Frontiers in Biomaterials Science 2024, 3, 1347324. [Google Scholar]

- van Breugel, M.; Fehrmann, R.S.; Bügel, M.; Rezwan, F.I.; Holloway, J.W.; Nawijn, M.C.; Fontanella, S.; Custovic, A.; Koppelman, G.H. Current state and prospects of artificial intelligence in allergy. Allergy 2023, 78, 2623–2643. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).