1. Introduction

Since the dawn of civilizations, designers, engineers, and architects have significantly contributed to the evolution of the construction industry, developing resilient, functional, and aesthetically pleasing buildings. However, these fundamental requirements must transcend into approaches that include clean technologies, carbon-neutral materials, energy-efficient construction strategies, and lifestyles that respond harmoniously to nature, optimizing the use of renewable resources and strengthening environmental resilience. In recent years, sustainable construction has acquired growing importance, driven by the global urgency to mitigate the negative environmental impacts derived from both the construction process and the production of materials.

In this context, biomimicry has emerged as a revolutionary concept in the construction industry, contributing to the development of solutions based on the adaptation and extraction of ideas from nature, incorporating them into design to help reduce environmental problems. The term biomimicry was conceptualized by biologist Janine Benyus in 1997, where it refers to a new field of science that studies nature, its models, systems, processes, and elements, imitating them or taking them as a source of inspiration to design sustainable proposals [

1]. Biomimicry encourages the transfer of functions, concepts and strategies from natural organisms or systems to create a more resilient built environment and improve its capacity to develop regenerative systems [

2], seeks to minimize the negative environmental impact of buildings through greater efficiency and moderation in the use of materials, energy, development space and the ecosystem in general, through a conscious focus on energy conservation and ecology within the design of the built environment [

3].

From urban planning, architectural design, construction technologies, materials, and components, nature offers an invaluable model for industry to move toward developing a resilient and environmentally responsible economy. The study of the adaptive mechanisms of natural organisms and systems, refined over millions of years, allows architects, engineers, and technology designers to integrate biomimetic strategies into contemporary construction, optimizing thermal, structural, and energy performance [

4]. Mimicking nature has several levels, including the organismal level, which influences the aesthetic appearance of buildings; the behavioral level, which contributes to energy efficiency and sustainability; and the ecosystem level, which focuses on functional issues at the urban scale [

5]. Historically, various civilizations have implemented biomimetic principles in their constructions. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans copied natural plants as part of the beauty of their buildings. The Goths, on the other hand, combined two levels of biomimicry: the organismal level and the behavioral level. They constructed elegant buildings using elements that mimicked plants, such as the rose window, and other elements inspired by animals, such as flying buttresses and ribbed vaults [

6].

In the field of sustainable buildings, the study "Biomimicry in Malaysian Architecture: Crafting A Modular Framework for Sustainable Design" highlights the application of self-healing materials inspired by bone biology and passive ventilation systems based on the morphology of termite mounds, significantly reducing energy consumption and the carbon footprint in buildings [

7] [

8]. Similarly,[

2] analyze the integration of biomimetic strategies in structural design and material selection, demonstrating how honeycomb-inspired structures and natural ventilation systems can optimize the thermal and energy efficiency of buildings. In turn, proposals for environmentally efficient solutions are presented to improve thermal comfort and reduce energy consumption through the design of nature-inspired envelopes [

9]. Through the analysis of several case studies, they identify the application of surfaces inspired by plant stomata to regulate transpiration and dynamic shading systems that mimic the opening and closing of flower petals. They also analyze the use of coral reefs as inspiration for improving structural design, applying biomimetic principles to structural engineering and the development of new construction materials [

10] . In a systematic study of biomimicry in sustainable construction, he mentions that the most common applications include the development of intelligent envelopes inspired by organisms, the use of biomimetic materials that optimize energy efficiency and the feeding of passive ventilation systems based on natural patterns [

11].

The study of biomimicry in construction has found an inexhaustible source of inspiration in natural structures, with particular emphasis on spider webs and bird and insect nests. The geometry and structural arrangement of spider webs, characterized by a network of radial and spiral filaments, have been the subject of research to improve fiber orientation in composite materials, optimizing their strength and load distribution in structural applications [

12]. In the architectural field, studies have highlighted the importance of natural morphologies in structural resilience, taking as a model the nests of wasps and bees, whose arrangement of hexagonal cells and adherent supports provide structural stability and efficiency [

13]. Likewise, studies on the nests of swallows and ovenbirds have shown the influence of available materials in the formation of structures optimized for thermal insulation and mechanical stability [

14]. These investigations highlight the potential of integrating biomimetic principles into construction to improve the efficiency and sustainability of one of the most polluting industries.

Within this framework, this article aims to identify sources of inspiration in the design, architecture, and construction industries by analyzing the biological organisms they use as references and the imitation criteria they apply. A systematic approach is established that classifies principles extracted from nature and their application in structures, materials, and construction systems. Through this analysis, we seek to demonstrate how biomimicry contributes to optimizing the energy efficiency, structural strength, and sustainability of buildings, promoting innovative solutions in harmony with the natural environment.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employs a qualitative and descriptive approach based on a systematic review of the scientific literature and a comparative analysis of biomimetic applications in the construction industry. A methodology structured in three main phases was established:

Phase 1: Compilation and selection of bibliographic sources.

Phase 2: Classification and analysis of imitation criteria used in applications in the construction industry.

Phase 3: Systematization of applications derived from the natural models studied.

An extensive literature search was conducted in high-impact indexed databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, selecting scientific articles, bibliographic reviews, and case studies published in the last 10 years. The inclusion criteria focused on studies addressing the application of biomimicry in buildings or topics related to the design and construction industry, resulting in a total of 70 documents selected for analysis.

To organize the collected data, eight main categories of biomimetic inspiration were established: (1) insects, (2) reptiles, (3) plants, (4) marine species, (5) fungi, (6) birds, (7) arthropods, and (8) ecosystems. Within each category, three key dimensions were analyzed: type of organism or natural system, part of the organism or natural system, imitation criteria (form, function, structure, and process), and the functional principles transferred through biomimetic design strategies.

The data obtained were structured into a comparative table detailing the relationship between the analyzed organisms, the adopted biomimetic principles, and their applications in the construction sector. To ensure the robustness of the study, the results were cross-validated with previous studies and documented cases in the literature. Additionally, the frequency of application of each imitation criterion was analyzed, identifying preference patterns in bio-inspired architecture and engineering.

This methodology enables an objective assessment of biomimicry’s impact on the industry, providing a solid technical and scientific foundation for the development of future bio-inspired construction technologies

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the main organisms and natural systems that have served as a reference in the application of biomimicry in design, architecture, and construction. Eight key categories are presented, detailing the type of organism, the specific part replicated, the imitation criteria applied (form (F), function (f), structure (E), or process (P)), and their respective applications in industry. This information allows for the analysis of biomimetic-inspired patterns and trends. The table provides a comparative overview that shows how different natural elements have been used to optimize various parameters that guide the industry toward sustainability.

3.1. Category Type and Application

In each category, organisms or natural systems have been identified whose characteristics have been replicated in various architectural and construction solutions, following imitation criteria that include form, function, structure and process.

In the insect category, termite mounds have been widely studied for their passive ventilation system, which has been replicated in buildings to improve thermal efficiency and reduce energy consumption. Likewise, termite metagenomics has served as a reference in the design of buildings capable of producing hydrogen, replicating biological principles at the levels of form, function, structure, and process. The dragonfly, meanwhile, has inspired lightweight and resistant roofs due to the geometry of its wings, serving as a reference for structural patterns that improve load distribution. Another relevant case is that of the fog-harvesting beetle, whose exoskeleton features hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces, which has led to the development of atmospheric water harvesting systems in arid areas. Likewise, the Saharan silver ant has been key in the design of radiative cooling systems, through the imitation of its microscopic triangular hairs that function as reflective structures.

Within the reptile category, the structure of snake scales has served as a reference for the design of façades that optimize passive ventilation and solar reflection, with the aim of improving interior thermal comfort. In turn, the chameleon has inspired the development of materials capable of dynamic color change through the reorganization of nanocrystals, enabling the creation of adaptive windows and façades that regulate their thermal reflectivity based on the outside temperature, thereby reducing energy consumption.

In the plant category, photosynthesis has been a key process replicated in the development of energy-efficient solar panels and facades. The plant cell wall has been used as a model for optimizing materials in lightweight, strong structures. In terms of functional properties, the superhydrophobicity of the lotus leaf has been imitated in the design of self-cleaning surfaces for windows and cladding. Furthermore, the opening and closing mechanism of the Strelitzia reginae (Bird of Paradise) flower has served as a reference in the design of adaptive shading systems for facades. Meanwhile, the structural flexibility of palm leaves and tropical plants has inspired the development of flexible and resilient shading systems, dynamic canopies, and modular sunshades. Finally, pine cones, with their ability to open or close depending on ambient humidity, have been used as a model in the design of passive light regulation, ventilation, and thermal insulation systems.

In the marine species category, the coral reef has served as inspiration for the development of lightweight structures and resistant roofs, due to its porous and branched organization. Likewise, the sea urchin skeleton, composed of interconnected polygonal plates, has been replicated in the design of modular structural systems that eliminate the need for torsion elements. The sand dollar, known for its strength, lightness, and efficient use of materials, has served as a reference in the optimization of structures with high mechanical resistance. Furthermore, the translucent gelatinous structure of jellyfish and their ability to interact with light and heat have inspired the development of thermochromic materials, which adjust their light transmission according to the outside temperature.

In the fungal category, Pleurotus ostreatus has been analyzed for its biological binding capacity, its adaptation to complex surfaces, and its bioactive mineralization process. These properties have been replicated in the development of innovative biocomposites, such as biodigital bricks, which feature improved structural strength and adaptability.

In the bird category, nests have been a source of inspiration for the design of strong and lightweight buildings, based on the intertwined arrangement of branches that optimizes natural ventilation and lighting. Furthermore, penguins have been the subject of study due to their thermal regulation capacity, which has allowed for the design of architectural solutions that minimize heat loss in cold climates, improving the energy efficiency of buildings. In the arthropod category, spider webs have been replicated in the design of façades and flexible roofs, due to their high resistance and ability to absorb and distribute energy. These principles have been applied to optimize passive ventilation and improve structural performance in buildings..

Finally, in the ecosystem category, forests, wetlands, and rivers have been analyzed as models of systemic organization and functioning. The ability of these environments to capture and convert solar energy, store water, and participate in natural cycles such as carbon and nitrogen has been replicated in sustainable solutions for urban design. These strategies have enabled the implementation of green infrastructure systems that promote environmental regeneration and resource efficiency in urban environments.

3.2. Imitation Criteria by Category

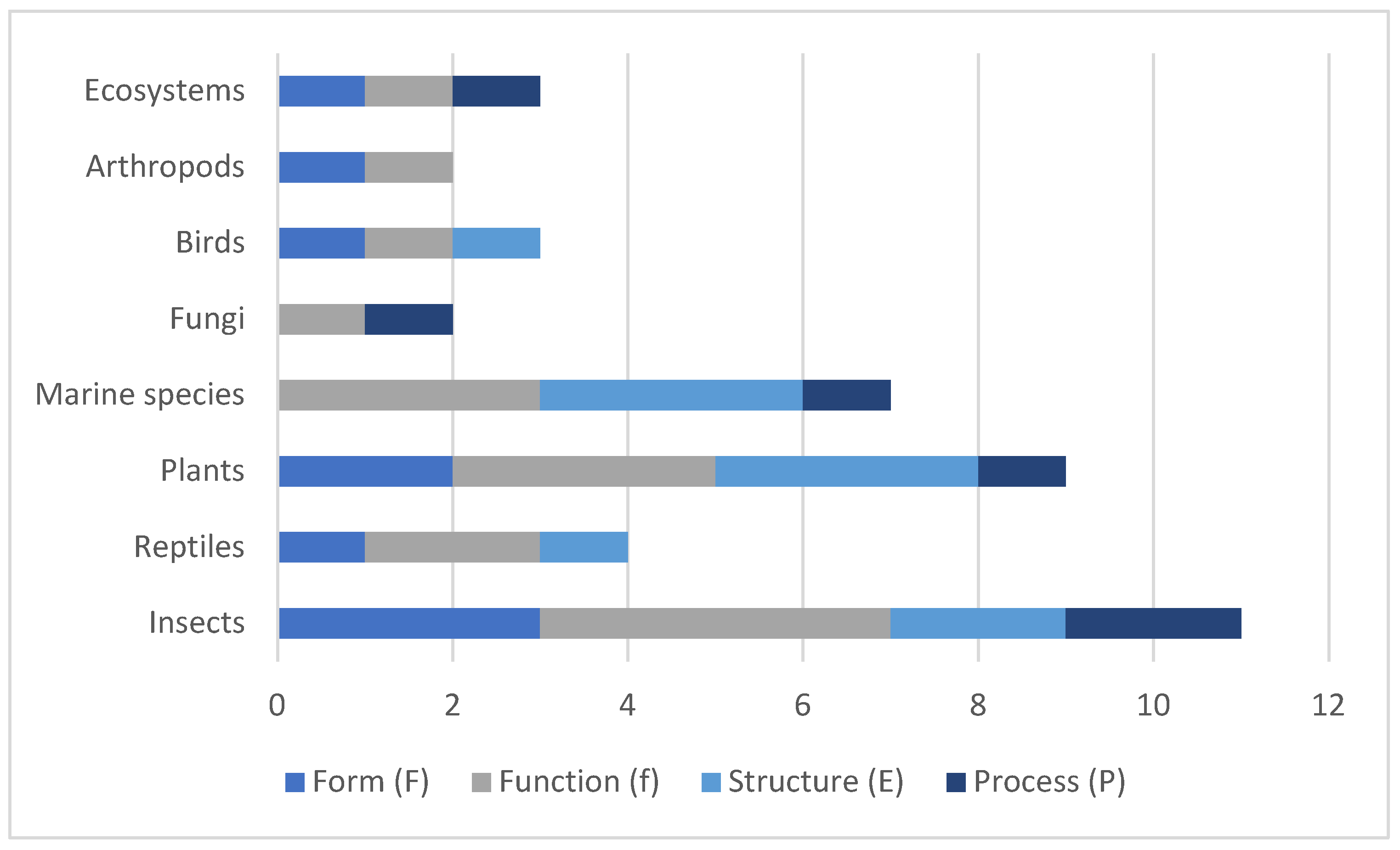

The imitation criteria established in the different categories and types of organisms or natural systems show a differential distribution in the imitation of characteristics applied in the fields of design, architecture, and construction. Comparing these criteria across the different categories reveals patterns that highlight a preference for some in bio-inspired design (see

Figure 1).

In the insects category, the imitation criterion related to function (f = 4) is most frequently present, followed by form (F = 3), structure (E = 2) and process (P = 2). In the reptiles category, the most representative imitation criteria are function (f = 2) and form (F = 1), while structure (E = 1) and process (P = 0) are less relevant. For plants, a balanced distribution of criteria is shown, with a high presence in function (f = 3), structure (E = 3) and form (F = 2), while the process is less represented (P = 1). On the other hand, in marine species, a significant preference is observed in imitating function (f = 3) and structure (E = 3), with a lower presence in the process (P = 1) and an absence of imitation in form (F = 0). Fungi present an application through the criteria function (f = 1) and process (P = 1), while form and structure (F = 0, E = 0) do not show significant records. Birds present equal distribution in the criteria Form (F = 1), function (f = 1) and structure (E = 1), while the process is not represented (P = 0). In the arthropod category, low values are identified in all criteria, with a slight predominance in form and function (F = 1, f = 1), while structure and process do not present values (E = 0, P = 0). Finally, ecosystems show a homogeneous distribution in all criteria, with low values in form, function and process (F = 1, f = 1, P = 1), and an absence of imitation in structure (E = 0).

In comparative terms, the results reflect that function is the most widely replicated imitation criterion across all categories, with a mean of f = 2.5, followed by structure (E = 1.5), form (F = 1.25), and, to a lesser extent, process (P = 0.75). This trend suggests that biomimicry, applied in design, architecture, and construction, focuses on the functional optimization of built systems, with an emphasis on energy efficiency, structural strength, and climate adaptability.

3.3. Patterns and Trends Identified

One of the most notable patterns is the preference for functional and structural imitation in most applications. The results indicate that the criteria of function (f) and structure (E) are more frequently used than those of form (F) and process (P). This suggests that in architecture and construction, designers prioritize biological strategies that offer improvements in energy efficiency, ventilation, and mechanical resistance over those related to aesthetics or specific biological processes. Notable examples include the replication of the passive ventilation system of termite mounds and the modular structure of the sea urchin in lightweight, strong buildings.

Likewise, a pattern of functional convergence is observed among organisms from different categories. That is, species from different kingdoms have served as inspiration for similar solutions in the built environment. For example, both pine cones and the plate systems of the sea urchin have been used in the design of facades and roofs that dynamically adjust to environmental conditions without requiring external energy. Similarly, atmospheric water harvesting strategies have emerged from different biological sources: the fog-harvesting beetle, with its hydrophobic and hydrophilic exoskeleton, and the porous structures of coral reefs, used for moisture retention in building systems adapted to arid climates.

In terms of thermal efficiency and energy regulation, the results indicate that terrestrial organisms have been more influential than marine or ecosystem-based ones. Most of the solutions applied in passive air conditioning derive from insects and reptiles, such as the thermal dissipation strategies of snake scales or the chameleon's ability to modify its thermal reflectivity in response to external stimuli. This indicates a tendency to study systems adapted to terrestrial environments with large thermal fluctuations, rather than aquatic organisms or ecosystems with less temperature variability. Another observed trend is the imitation of modular and self-assembling principles in the development of materials and construction systems. Organisms such as fungi (Pleurotus ostreatus) have served as models for the creation of biocomposites with self-assembly and regeneration properties, suggesting a growing interest in materials inspired by biological processes of aggregation and growth. This same principle has been observed in structures such as coral reefs and the calcareous skeletons of echinoderms, which have inspired architectural designs that combine lightness and strength.

From an ecosystem integration perspective, the results indicate that urban systems have begun to adopt organizational principles observed in forests and wetlands. This pattern is evident in the development of green infrastructures that seek to replicate natural cycles of water capture and filtration, temperature regulation, and pollutant absorption. Biomimicry applied to ecosystems has enabled the implementation of regenerative solutions that improve the environmental resilience of cities, promoting urban models that resemble the organization and functioning of natural systems.

4. Discussion

The results show that biomimicry has been widely explored and applied in the design, architecture, and construction industries, with a predominant focus on the functional and structural optimization of materials and structural systems. The identification of natural organisms and systems as references has allowed for the establishment of a comparative framework where the imitation criteria (form, function, structure, and process) show a clear tendency toward the replication of adaptive solutions with high energy and structural performance. A key finding of this research is the functional convergence between different organisms and its impact on the development of architectural solutions. For example, both the morphology of fog-harvesting beetles and the porous structure of coral reefs have been used to design water harvesting systems in arid areas, optimizing the efficient use of water resources in urban and desert environments. This result suggests that, beyond the taxonomic categorization of the source organisms of inspiration, biomimicry is oriented towards the identification of transferable functional principles with a high degree of applicability in various construction contexts. Furthermore, the literature analysis reflects that bio-inspired strategies have enabled disruptive innovations in design, architecture and construction, such as the development of superhydrophobic surfaces based on the lotus leaf [

48] or the use of bioaggregate materials inspired by fungi of the genus Pleurotus for the manufacture of biodegradable bricks with improved thermal insulation properties and structural resistance [

74].

Another relevant aspect is the integration of modular and self-assembling principles into construction materials and systems, following biological organization patterns present in the calcareous skeletons of echinoderms or plant cellular structures. The trend toward nature-inspired modular systems responds to the growing need for adaptive and sustainable architectural solutions that optimize material efficiency and reduce the environmental footprint of the construction sector. However, while significant progress has been made in the implementation of biomimicry at the material and structural levels, this study reveals a lesser application of strategies inspired by dynamic biological processes, such as self-healing and real-time functional adaptation. This represents an opportunity for future research for the development of smart materials and architectural systems capable of actively responding to environmental changes without the need for external energy inputs.

Learning from ecosystem integration suggests that biomimetic strategies applied in urban environments have evolved towards holistic approaches that replicate self-regulation processes observed in natural environments, indicating the prioritization of nature's teachings to mitigate the environmental impact of cities, promoting regenerative urban planning models that prioritize climate resilience and energy efficiency [

23]. However, the widespread adoption of biomimicry in architecture and construction still faces significant challenges, such as the lack of standardization in bio-inspired design methodologies, the economic viability of biomimetic materials compared to conventional solutions, and the need for regulatory frameworks that encourage their implementation in large-scale projects.

5. Conclusions

The patterns observed in the application of biomimicry in the fields of design, architecture, and construction reflect a predominant focus on the optimization of function and structure, with a marked functional convergence between different organisms and natural systems. The sector's prioritization is evident in a trend toward bio-inspired strategies that improve the energy efficiency, mechanical resistance, and climatic adaptability of buildings, rather than focusing solely on formal principles. The trend toward the adoption of modular principles, thermal regulation inspired by terrestrial organisms, and the integration of ecosystem models into urban planning suggests an evolutionary path toward more adaptive, efficient, and sustainable architectures.

The distribution of imitation criteria shows that certain organisms and natural systems have been emulated primarily in function and structure, while imitation of processes and forms is less common. These findings highlight the relevance of biomimicry as an innovation strategy in architecture and construction, enabling the development of resilient solutions based on biological principles optimized throughout natural evolution. However, there are still opportunities for exploration in the replication of dynamic self-regulation mechanisms and the refinement of adaptive design approaches. The implementation of bio-inspired materials with regenerative properties, the integration of ventilation and air conditioning systems based on natural models, and the exploration of self-assembling patterns in architectural structures emerge as lines of research with high potential for impact on the sustainability of the built environment.

Ultimately, biomimicry represents not only a key tool for optimizing the energy and structural performance of buildings, but also a design paradigm that promotes a more harmonious relationship between the natural and built environments. Its effective integration will depend on the convergence of technological innovation, interdisciplinary scientific research, and the formulation of public policies that encourage its adoption in a global context of transition toward more efficient, resilient, and regenerative buildings. The future of sustainable construction demands a holistic approach where biomimicry, supported by advances in materials science, computational modeling, and digital manufacturing, plays a leading role in the evolution of architectural design toward smarter and more environmentally responsible solutions.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Dirección de Investigación y Desarrollo of the Universidad Técnica de Ambato, which supported this work, as well as the Facultad de Diseño y Arquitectura, to the public and private institutions, people related, researchers, and to the entire university team that collaborated and monitored the work.

References

- Røstvik, H.N. Sustainable Architecture—What’s Next? Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 293–313. [CrossRef]

- Pugalenthi, A.M.; Khlie, K.; Ahmed, F.H. Harnessing the Power of Biomimicry for Sustainable Innovation in Construction Industry. J. Infrastructure, Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Abeywardhana, A.S. Green Building and Energy Efficient Design. 2024, 23, 1621–1629.

- Rahubadda, A.; Kulatunga, U. Harnessing Nature’s Blueprint: Biomimicry in Urban Building Design for Sustainable and Resilient Cities. In Proceedings of the 12th World Construction Symposium; 2024; pp. 532–543.

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X. Bioinspired Adaptive Landscape Design: Environmental Responsiveness Strategy Based on Biomimetic Principles—Driven Molecular and Cellular Biomechanics. MCB Mol. Cell. Biomech. 2025, 22, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Al-Masri, A.; Abdulsalam, M.; Hashaykeh, N.; Salameh, W. Bio-Mimicry in Architecture: An Explorative Review of Innovative Solution toward Sustainable Buildings. An-Najah Univ. J. Res. - A (Natural Sci. 2025, 39, 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.; Noor, M.Z.M.; Azeqa, A. Biomimicry in Malaysian Architecture : Crafting A Modular Framework for Sustainable Design. 2024, 14, 609–618. [CrossRef]

- Claggett, N.; Surovek, A.; Capehart, W.; Shahbazi, K. Termite Mounds: Bioinspired Examination of the Role of Material and Environment in Multifunctional Structural Forms. J. Struct. Eng. 2018, 144, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Elsakksa, A.; Marouf, O.; Madkour, M. Biomimetic Approach for Thermal Performance Optimization in Sustainable Architecture. Case Study: Office Buildings in Hot Climate Countries. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1113. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.A.; Klotz, L.E.; Ross, B.E. Mathematically Characterizing Natural Systems for Adaptable, Biomimetic Design. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Design, Engineering and Construction Mathematically; Elsevier B.V., 2016; Vol. 145, pp. 497–503.

- Ergün, R.; Aykal, F.D. The Use of Biomimicry in Architecture for Sustainable Building Design: A Systematic Review. Alam Cipta 2022, 15, 24–37. [CrossRef]

- Regassa, Y.; Lemu, H.G.; Sirabizuh, B.; Rahimeto, S. Studies on the Geometrical Design of Spider Webs for Reinforced Composite Structures. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Sedira, N.; Pinto, J.; Ginja, M.; Gomes, A.P.; Nepomuceno, M.C.S.; Pereira, S. Investigating the Architecture and Characteristics of Asian Hornet Nests: A Biomimetics Examination of Structure and Materials. Materials (Basel). 2023, 16. [CrossRef]

- Bulit, F.; Massoni, V. Arquitectura de Los Nidos de La Golondrina Ceja Blanca (Tachycineta Leucorrhoa) Construidos En Cajas Nido. El Hornero 2004, 19, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Gertik, A.; Karaman, A. The Fractal Approach in the Biomimetic Urban Design: Le Corbusier and Patrick Schumacher. Sustain. 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E.; Cruz, E.; Lequette, C.; Raskin, K.; Clergeau, P. Biomimicry in French Urban Projects: Trends and Perspectives from the Practice. Biomimetics 2021, 6, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Othmani, N.I.; Mohd Yunos, M.Y.; Ramlee, N.; Abdul Hamid, N.H.; Mohamed, S.A.; Yeo, L.B. Biomimicry Levels as Design Inspiration in Design. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 1094–1107. [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, Y.; Blanco, E.; Kohsaka, R. Application of Biomimetics to Architectural and Urban Design: A Review across Scales. Sustain. 2020, 12, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Othmani, N.I.; Mohamed, S.A.; Abdul Hamid, N.H.; Ramlee, N.; Yeo, L.B.; Mohd Yunos, M.Y. Reviewing Biomimicry Design Case Studies as a Solution to Sustainable Design. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 69327–69340. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Stefańska, A. Bio-Logic, a Review on the Biomimetic Application in Architectural and Structural Design. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, A.; Babafemi, A.J.; Paul, S.C.; Panda, B.; Tran, J.P.; Broeckhoven, C. Biomimicry for 3D Concrete Printing: A Review and Perspective. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101823. [CrossRef]

- Samra, M.A.; Gendy, N.G.A. Mapping Biomimicry Design Strategies to Achieving Thermal Regulation Efficiency in Egyptian Hot Environments. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Urban Res. 2021, 4, 261–279. [CrossRef]

- Shashwat, S.; Zingre, K.T.; Thurairajah, N.; Kumar, D.K.; Panicker, K.; Anand, P.; Wan, M.P. A Review on Bioinspired Strategies for an Energy-Efficient Built Environment. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113382. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yao, L.; Liu, H.; Ding, Y. Dragonfly-Inspired 3D Bionic Folding Grid Structure Design. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Lietz, C.; Schaber, C.F.; Gorb, S.N.; Rajabi, H. The Damping and Structural Properties of Dragonfly and Damselfly Wings during Dynamic Movement. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Teng, T.; Chang, H.; Chen, P. Desert Beetle-Inspired Hybrid Wettability Surfaces for Fog Collection Fabricated by 3D Printing and Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Treatment. 2025, 1–14.

- Zhu, H.; Guo, Z. Hybrid Engineered Materials with High Water-Collecting Efficiency Inspired by Namib Desert Beetles. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 6809–6812. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yun, F.F.; Wang, Y.; Yao, L.; Dou, S.; Liu, K.; Jiang, L.; Wang, X. Desert Beetle-Inspired Superwettable Patterned Surfaces for Water Harvesting. Small 2017, 13, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Wang, L.; Ju, J.; Sun, R.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, L. Efficient Water Collection on Integrative Bioinspired Surfaces with Star-Shaped Wettability Patterns. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 5025–5030. [CrossRef]

- Gurera, D.; Bhushan, B. Optimization of Bioinspired Conical Surfaces for Water Collection from Fog. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 551, 26–38. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerl, M.; van Nieuwenhoven, R.W.; Whitmore, K.; Vetter, W.; Gebeshuber, I.C. Biomimetic Cooling: Functionalizing Biodegradable Chitosan Films with Saharan Silver Ant Microstructures. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Lin, S.; Wei, M.; Huang, J.; Xu, H.; Lu, Y.; Song, W. Flexible Passive Radiative Cooling Inspired by Saharan Silver Ants. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 210, 110512. [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.N.; Tsai, C.C.; Camino, F.; Bernard, G.D.; Yu, N.; Wehner, R. Keeping Cool: Enhanced Optical Reflection and Radiative Heat Dissipation in Saharan Silver Ants. Science (80-. ). 2015, 349, 298–301. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerl, M.; Kaltenböck, P.; Gebeshuber, I.C. Utilizing Passive Radiative Properties of Silver Ants †. 2024, 10–11. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.H.F.; Ali, K.A.Y.; Ahmed, S.A.M. Biomimicry as an Approach to Improve Daylighting Performance in Office Buildings in Assiut City, Egypt. J. Daylighting 2023, 10, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.K.; Nguyen, T.N.; Ghazlan, A.; Ngo, T.D. Biomimetic Adaptive Electrochromic Windows for Enhancing Building Energy Efficiency. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117341. [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Rubio, R.; Martín, S.; Ben Croxford How Plants Inspire Façades. From Plants to Architecture: Biomimetic Principles for the Development of Adaptive Architectural Envelopes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 692–703. [CrossRef]

- Sandak, A.; Sandak, J.; Brzezicki, M.; Kutnar, A. State of the Art in Building Façades, in: Bio-Based Building Skin. Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes.; 2019; ISBN 9789811337468.

- De Luca, F.; Sepúlveda, A.; Varjas, T. Static Shading Optimization for Glare Control and Daylight. Proc. Int. Conf. Educ. Res. Comput. Aided Archit. Des. Eur. 2021, 2, 419–428. [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, R.; Spear, M.; Curling, S.; Wooten-Beard, P.; Jones, P.; Donnison, I.; Ormondroyd, G. Plants and Architecture: The Role of Biology and Biomimetics in Materials Development for Buildings. Intell. Build. Int. 2019, 30, 1145–1154, . [CrossRef]

- Yeler, G.M. Mimari Strüktürlerde Canlı Dünyanın Etkilerine Analitik Bir Bakış. Uludağ Univ. J. Fac. Eng. 2015, 20, 23. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Cai, C.; Kuai, L.; Li, T.; Huttula, M.; Cao, W. Leaf-Structure Patterning for Antireflective and Self-Cleaning Surfaces on Si-Based Solar Cells. Sol. Energy 2018, 159, 733–741. [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Luo, G.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z. Bioinspired Superwettability Micro/Nanoarchitectures: Fabrications and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Nanaa, Y. The Lotus Flower: Biomimicry Solutions in the Built Environment. Sustain. Dev. Plan. VII 2015, 1, 1085–1093. [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.M.; Safiuddin, M. Lotus-Leaf-Inspired Biomimetic Coatings: Different Types, Key Properties, and Applications in Infrastructures. Infrastructures 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, L.; Qian, H.; Li, X. Superhydrophobic Surfaces for Corrosion Protection: A Review of Recent Progresses and Future Directions. J. Coatings Technol. Res. 2016, 13, 11–29. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Dong, C. Biomimetic Self-Cleaning Surfaces : Synthesis , Mechanism and Applications. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Mou, J.; Zheng, S.; Jiang, L.; Sun, Z.; Wang, E. Research Progress of Biomimetic Superhydrophobic Surface Characteristics, Fabrication, and Application. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Nishikawa, N.; Mayama, H.; Nonomura, Y.; Yokojima, S.; Nakamura, S.; Uchida, K. Theoretical Explanation of the Lotus Effect: Superhydrophobic Property Changes by Removal of Nanostructures from the Surface of a Lotus Leaf. Langmuir 2015, 31, 7355–7363. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Zhu, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Superhydrophobic Surface Based on Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2019, 33, 1870–1881. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liang, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qu, X.; Yang, Z. Lotus Leaf Inspired Robust Superhydrophobic Coating from Strawberry-like Janus Particles. NPG Asia Mater. 2015, 7. [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, V.; Hannequart, P.; Adriaenssens, S.; Baverel, O.; Viglino, E.; Eisenman, S. Kinematic Amplification Strategies in Plants and Engineering. Smart Mater. Struct. 2017, 26, 0–30. [CrossRef]

- Avinç, G.M. Biomimetic Approach for Adaptive, Responsive and Kinetic Building Facades: A Bibliometric Review of Emerging Trends. New Des. Ideas 2024, 8, 567–580. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Tahouni, Y.; Sahin, E.S.; Ulrich, K.; Lajewski, S.; Bonten, C.; Wood, D.; Rühe, J.; Speck, T.; Menges, A. Weather-Responsive Adaptive Shading through Biobased and Bioinspired Hygromorphic 4D- Printing (under Review). Nat. Commun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X. Adaptive Façades: Review of Designs, Performance Evaluation, and Control Systems. Buildings 2022, 12, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Guzmán, C.C. Diseño y Construcción de Un Paraguas Plegable Para Espacios Arquitectónicos. Rev. Arquit. 2019, 21. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Fadli, F.; Mohammadi, M. Biomimetic Kinetic Shading Facade Inspired by Tree Morphology for Improving Occupant’s Daylight Performance. J. Daylighting 2021, 8, 65–82. [CrossRef]

- El-Rahman, S.M.A.; Esmail, S.I.; Khalil, H.B.; El-Razaz, Z. Biomimicry Inspired Adaptive Building Envelope in Hot Climate. J. Eng. Res. 2020, 166, A1–A17. [CrossRef]

- KAHRAMANOĞLU, B.; ÇAKICI ALP, N. Kinetik Sistemli Bina Cephelerinin Modelleme Yöntemlerinin İncelenmesi. AURUM J. Eng. Syst. Archit. 2021, 5, 119–138. [CrossRef]

- Kuru, A. Biomimetic Adaptive Building Skins : An Approach towards Multifunctionality. (Doctoral Dissertation. University of New South Wale), 2022.

- Bijari, M.; Aflaki, A.; Esfandiari, M. Plants Inspired Biomimetics Architecture in Modern Buildings: A Review of Form, Function and Energy. Biomimetics 2025, 10. [CrossRef]

- Webb, M. Biomimetic Building Facades Demonstrate Potential to Reduce Energy Consumption for Different Building Typologies in Different Climate Zones. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 24, 493–518. [CrossRef]

- Faragalla, A.M.A.; Asadi, S. Biomimetic Design for Adaptive Building Façades: A Paradigm Shift towards Environmentally Conscious Architecture. Energies 2022, 15, 0–21. [CrossRef]

- Maslov, D.; Cruz, F.; Pinheiro, M.; Miranda, T.; Valente, I.B.; Ferreira, V.; Pereira, E. Functional Conception of Biomimetic Artificial Reefs Using Parametric Design and Modular Construction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024.

- Vivier, B.; Dauvin, J.C.; Navon, M.; Rusig, A.M.; Mussio, I.; Orvain, F.; Boutouil, M.; Claquin, P. Marine Artificial Reefs, a Meta-Analysis of Their Design, Objectives and Effectiveness. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 27, e01538. [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.T.; Huang, J.Y. 3D Printed Artificial Coral Reefs : Design and Manufacture. Low-carbon Mater. Green Constr. 2024, 4. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.A.; Ross, B.E.; Klotz, L.E. Lessons from a Coral Reef: Biomimicry for Structural Engineers. J. Struct. Eng. 2015, 141. [CrossRef]

- La Magna, R.; Gabler, M.; Reichert, S.; Schwinn, T.; Waimer, F.; Menges, A.; Knippers, J. From Nature to Fabrication: Biomimetic Design Principles for the Production of Complex Spatial Structures. Adv. Archit. Geom. 2012 2013, 107–122. [CrossRef]

- Grun, T.B.; Scheven, M. von; Geiger, F.; Schwinn, T.; Sonntag, D.; Bischoff, M.; Knippers, J.; Menges, A.; Nebelsick, J.H. Building Principles and Structural Design of Sea Urchins: Examples of Bio-Inspired Constructions. Biomimetics Archit. 2019, 104–115. [CrossRef]

- Shapkin, N.P.; Papynov, E.K.; Panasenko, A.E.; Khalchenko, I.G.; Mayorov, V.Y.; Drozdov, A.L.; Maslova, N. V.; Buravlev, I.Y. Synthesis of Porous Biomimetic Composites: A Sea Urchin Skeleton Used as a Template. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Perricone, V.; Grun, T.B.; Marmo, F.; Langella, C.; Candia Carnevali, M.D. Constructional Design of Echinoid Endoskeleton: Main Structural Components and Their Potential for Biomimetic Applications. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 2021, 16. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, B.; Mutlu-Avinç, G.; Arslan-Selçuk, S. Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Glass Facades Through Biomimetic Design Strategies. Habitat Sustentable 2024, 14, 34–43. [CrossRef]

- Paar, M.J.; Petutschnigg, A. Biomimetic Inspired, Natural Ventilated Facade A Conceptual Study. J. Facade Des. Eng. 2017, 4, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, Y.K.; Estévez, A.T. Biowelding 3D-Printed Biodigital Brick of Seashell-Based Biocomposite by Pleurotus Ostreatus Mycelium. Biomimetics 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Castriotto, C.; Giantini, G.; Celani, G. Biomimetic Reciprocal Frames A Design Investigation on Bird’s Nests and Spatial Structures. Proc. Int. Conf. Educ. Res. Comput. Aided Archit. Des. Eur. 2019, 1, 613–620. [CrossRef]

- Vitalis, L.; Chayaamor-Heil, N. Forcing Biological Sciences into Architectural Design: On Conceptual Confusions in the Field of Biomimetic Architecture. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 179–190. [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.J.; Brock, G.; Kietzig, A.M. The Penguin Feather as Inspiration for Anti-Icing Surfaces. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 213, 4–9. [CrossRef]

- Kreder, M.J.; Alvarenga, J.; Kim, P.; Aizenberg, J. Design of Anti-Icing Surfaces: Smooth, Textured or Slippery? Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1. [CrossRef]

- Naderinejad, M.; Junge, K.; Hughes, J. Exploration of the Design of Spiderweb-Inspired Structures for Vibration-Driven Sensing. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Choi, G.S.; Kim, H. Climate-Adaptive Building Envelope Controls: Assessing the Impact on Building Performance. Sustain. 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).