Theoretical Framework

Administrative burden is a term that is used to describe the onerous nature that citizens encounter when interacting with government (Halling & Baekgaard, 2024; Moynihan et al., 2015). Such burden can be conceptualized as occurring in three areas: learning costs, compliance costs, and psychological costs (Herd et al., 2023). Learning costs are “the challenges that people face finding out about a program’s existence and benefits, determining whether they are eligible for the program and what benefits they might receive, as well as understanding how to apply for, retain, and redeem benefits” (Herd et al., 2023 pg. 4). Compliance costs involve the time and effort spent on administrative tasks such as filling out forms, driving to government offices, waiting on hold for phone services, documenting status, and responding to bureaucratic requests (Herd et al., 2023). Psychological costs are the anxiety, stigma, and stress caused by applying for or maintain access to benefits and services (Herd et al., 2023).

Higher levels of administrative burden can hinder access to services and benefits and can reinforce existing social inequities (Chudnovsky & Peeters, 2021; Halling & Baekgaard, 2024; Herd et al., 2023). Administrative burden is experienced differently by different subpopulations, with people living in poverty, people with disabilities, and people with limited social networks experiencing higher levels of burden compared to others (Carey et al., 2021; Christensen et al., 2020; Chudnovsky & Peeters, 2021; Herd, 2023).

The quality of frontline service delivery and government communication can increase or decrease administrative burden (Halling & Baekgaard, 2024). A scoping review that examined the communication preferences of populations served by a variety of government programs including those provided by SSA identified agency communication with rural populations as an area in need of more in-depth study (Henly et al., 2023). This synthesis of prior research found that the mode of communication affects the public’s knowledge and benefits enrollment and that communication approaches that consider community-specific contexts are most effective. In addition, this research highlighted some of the unique barriers that people residing in rural areas might face, including lack of internet access, no local government offices to visit in person, or a lack of transportation. Additional research has highlighted the inverse relationship between higher rates of poverty and lower access to social services found in rural counties in the U.S. (Shapiro, 2021). This suggests that people living in rural areas have less access to formal social networks (e.g., case managers at health or social service agencies; advocates) which may further hinder their ability to learn about and apply for SSA benefits when eligible (Boswell & Smedley, 2023).

Further, although SSA has increased access to online services, SSA agency staff in rural areas have noted continued challenges with slow internet speeds and low bandwidth (Government Accountability Office, 2022). Without consistent internet services, SSA beneficiaries experience heightened levels of disadvantage. As a recent GAO report noted:

(SSA) faces challenges reaching and providing services to certain groups who may face disproportionate barriers, including lack of consistent access to technology. These vulnerable populations include older adults, those with limited English proficiency, those experiencing homelessness, those in rural areas, individuals with low incomes, individuals with disabilities, and those without legal representation in the disability appeals process. The transition to remote services disproportionately affected vulnerable groups, according to those we interviewed, because of their previous reliance on in-person services. (Government Accountability Office, 2022, p. 33).

Yet, SSA may, due to limitations in its administrative budget, need to develop methods of service delivery that rely more heavily on automated or electronic processes rather than hard copy or in-person forms of service delivery. In fact, reductions in SSA’s administrative budget have substantially reduced its staff and resources and impacted its ability to effectively serve all eligible beneficiaries (Romig, 2023b). As SSA strives to ensure it is providing equitable access to support all communities with these limited levels of resources, understanding the impact of the current service delivery environment on certain subpopulations is particularly important.

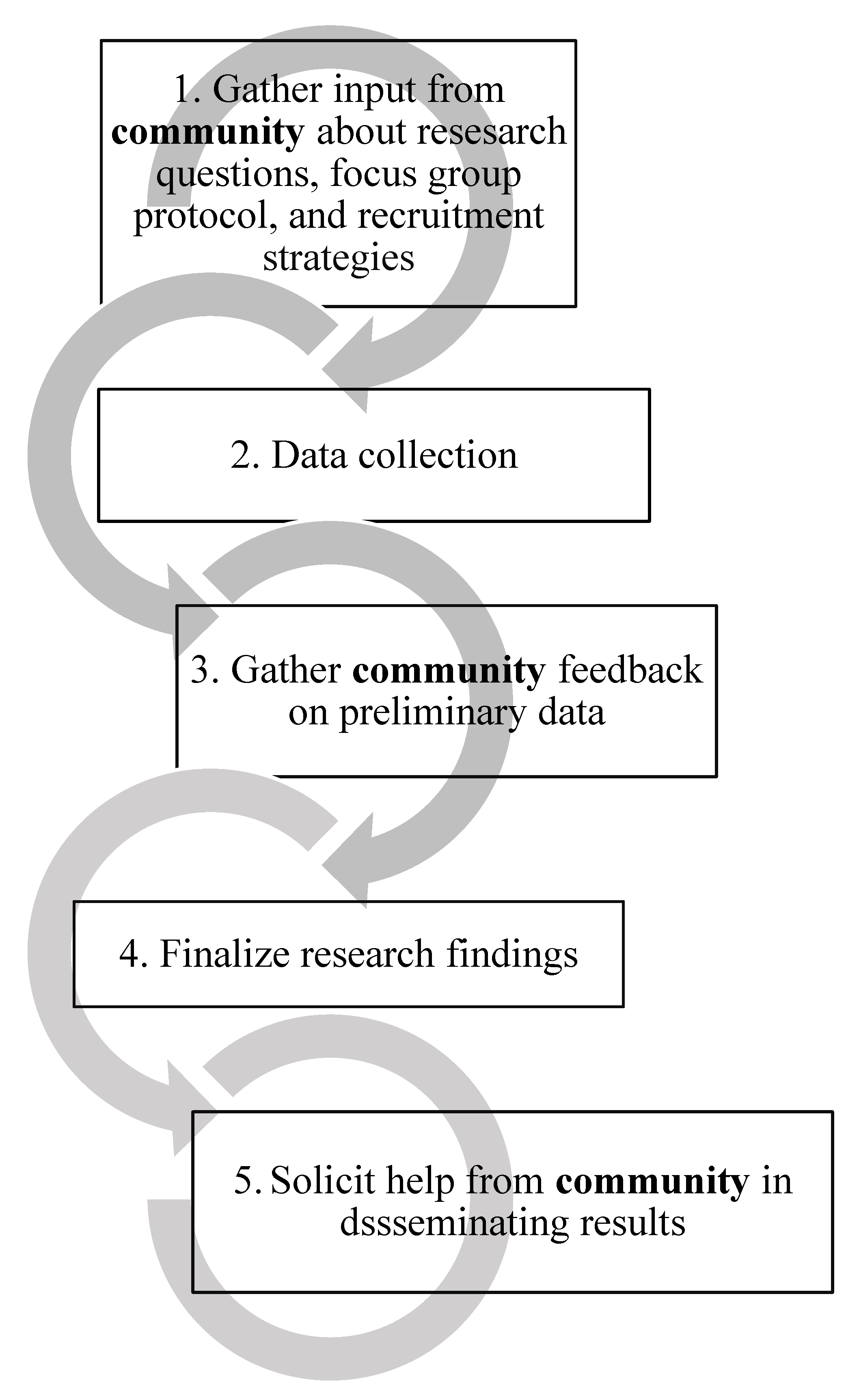

With this background in mind, we embarked on a community-engaged research project to explore how rural persons with disabilities and rural older adults are interacting with SSA, and to identify action steps at both the community and the SSA levels that can improve communication and service delivery. Our initial research questions were:

(1) What service-related barriers do individuals living in rural areas face when seeking SSA benefits and how do these individuals prefer to communicate with SSA when seeking benefits (e.g., online, by telephone, in-person)?

(2) How do these service-related barriers and communication preferences vary by sociodemographic groups (e.g., educational attainment, age) within rural populations?

(3) How do service perceptions (e.g., satisfaction) and outcomes (e.g., wait times) vary by sociodemographic characteristics?

Results

The findings from the focus groups and interviews can be conceptualized as falling within six overarching themes, as shown in

Table 4. While not all of the themes relate to administrative burden, we do denote in the narrative below where these themes overlap with the administrative burden literature.

Theme One: Initial Applications for Benefits

1a. Within this theme, participants noted that the process of applying for SSA disability benefits was much more complicated than applying for other types of benefits and usually required assistance from others to either alert them that they may be eligible for benefits and/or to manage the application and maintenance process. As one participant noted: “I did look into Social Security for disability benefits. But like (another participant) has said, the red tape and paperwork was just overwhelming, and I didn't get very far.” This alludes to the learning cost of administrative burden. People who were successful in being awarded disability benefits relied on formal and informal social networks for their knowledge. Among people who were receiving disability benefits, most had received assistance from medical personnel, lawyers, or other service providers (case workers, etc.) to notify them that disability benefits were an option and to initiate the application process. One participant noted that she was hospitalized three times for a mental health condition (over a decade ago) before a doctor mentioned that disability benefits (and its associated health insurance) could be an option for her. She stated, “I didn't know that I could get it for mental health. I thought you had to have a physical disability or [be] retired.” Yet other participants who had mental health conditions mentioned the ease of being approved for benefits the first time they applied, although they too usually had a medical or social service advocate help them with the process. Another participant, in speaking generally about disability benefits, noted:

People should not have to rely on a lawyer in order to initially apply for Social Security. I think that … if they're looking for SSI and they need SSDI … They're not applying for those benefits because they have resources. And they don't have the money to hire a lawyer and many of them feel like that's the only way they're gonna get benefits. That's not cool.

1b. Many rural residents expressed that getting copies of paperwork to apply for benefits was challenging. To address these compliance costs, many people rely on a social network (e.g., family/friends), libraries, or field office staff to make copies for them. “The library charges and they normally, Social Security, they don't charge. Yeah, usually they say ‘I'll make a copy for you’ and they'll give you back the original. Depends on who's at the desk, too. You know, [if] they're nice enough to do that for you.”

1c. The application process was much more straightforward for people seeking retirement benefits, with most retirees noting easy access. Some, including this woman below, stated that their employers helped them with the process of applying for retirement benefits. An individual shared, “Oh, I started getting Social Security. I believe when I was 62, it may have been 62 or it may have been 65. I'm not sure which. But I had a very good experience. … I retired from ________, which was a wonderful place to work, and they helped a lot in telling me what I should be doing while I was doing the application.”

1d. People on disability benefits usually saw benefits as a last resort and something they did not want to have. This can be construed as the psychological cost of administrative burden. Most would prefer to work. “I'm keeping it (disability benefits) because I need it and I know I can't get a full-time job, but if I could handle a full-time job, I'd probably just get rid of that [disability benefits],” said one participant. Another participant shared concern with: “… the whole process of not being able to work like I used to.” He continued: “I still have a problem talking about disability or me being on disability because I've been working since I was 15. All physical labor I used to do.”

1e. Nevertheless, people recognized the importance of SSA benefits for improving their economic security and worried about being able to keep benefits once they had been awarded benefits. One participant noted the psychological costs this way:

The system, because, boy, it really came into play and helped us. It helped me when I had my little children. … So, I had enough money to pay my bills when I had my little children, and if I hadn't had that I would have been in a deep pickle, which is why it's so anxiety producing. Because you're counting on it.

Another person stated: “If I didn't have it, I'd be homeless, [but it] doesn't pay enough to live decently.”

Theme Two: SSA Customer Service

2a.Participants noted high levels of satisfaction with in-person service when they could access it at a local field office. This finding suggests that high quality front line services reduce administrative burden. While 16 of our 39 participants resided in counties without field offices, those that were able to visit a field office were generally quite satisfied. In describing the local field office staff, one participant stated: “They were really kind, very helpful. Toward the end … they were sick of me. And I was sick of them. But they were so good and so kind. I wish I could remember their name.” An older adult noted, “I would say we're lucky in the town, because we have the office right here, very convenient. People that don't have an office right in their town have to travel.” Many participants noted a strong preference for visiting a field office in-person over communicating with SSA through other means: “When you try to reach them [SSA] by phone or you try to get on the computer, it's a whole different story [compared to visiting a field office] … So, I feel bad for people who don't have an office.” Field offices were also useful in helping people decipher information received from SSA through the mail, as one participant stated: “If I received something I didn't understand, I went [to the field office] either with my daughter who was a nurse … A lot of it, I didn’t understand.”

Participants who had visited field offices were generally satisfied with the location, hours, and staff. Still, for certain participants, visiting a field office incurred psychological costs. Some noted that having a guard on-site, rather than helping ensure a feeling of safety, felt intimidating:

There's usually a police officer there. And it is a little scary in there, you know, like for me, because I'm not used to being in a room for long periods of time, at least. In my experience it was long periods of time. Thank God there was a bathroom, but sort of waiting, and having being guarded with an armed person in the room, you know, so for me, that's intimidating to be there.

Another participant, although noting that the guard was “friendly and helpful” stated that “other staff seem annoyed but aren't outwardly rude. But part of the issue with going to an office is that [I] struggle to go outside some days due to disability” so visiting a field office is difficult because it raises anxiety, even though she had a vehicle and lived somewhat close to the field office.

2b. Transportation to field offices was a concern for these rural residents, even for those that had a field office in their county. This finding relates to compliance costs as it added to the time and effort required to access services. People who resided in congregate housing were sometimes able to use transportation provided by the facility to travel to a field office. Most, however, did not have access to any sort of affordable public transportation. Concerns were heightened for people living in counties that did not have field offices as they mentioned that they would need to travel an hour or more to the closest office. One person mentioned how some of the choices he needed to make while living on a limited income impacted his ability to travel:

There should be more offices …[It’s] so far … from here. About an hour and 40 minutes. I don't know about everybody else, but everybody might not have cars to get there. Transportation is a real problem. Me personally, I'm homeless living in my car. It's real hard, you know, since you’re using gas money just to heat up the car like and then that takes away going to Social Security if I need to. And it's hard.

Some participants who did not have a field office in their county discussed and dismissed using cabs as an travel option (“The cab guy, they would come get you, but I mean, it costs money a lot of money. It's like $25 one way.”). Relying on family or friends for transportation was a concern due to expense also (“Most people can't afford to bring you anywhere from here.”) and inconvenience. As one disability beneficiary noted:

You know, I have to let my wife know, who you know, works 40-hour weeks that you know I have to … be here at a certain time, so she'll have to take the day off for just me to go there, which you know she will. She understands but … it's an inconvenience a little bit.

2c. Participants continually shared that communicating by mail, phone, or on the internet was less valued and leads to misunderstanding, missed opportunities, and increased in-person visits for clients. The high levels of learning, compliance, and psychological costs that participants were experiencing were not alleviated by these modes of SSA communication. Participants expressed some concerns related to the language that SSA used to communicate information. “A lot of their [SSA] words [written or online] … sometimes I don't understand,” said one participant. Another stated: “Sometimes when they write something that doesn't make sense, we have to call and find out what's going on.” One person noted that navigating the SSA website was complicated. They shared that going to the field office is easier compared to online because “you don’t need to know the terminology [that you need to look online].”

Participants had mixed reviews about the service they received from SSA over the phone. They shared stories about long wait times (with one participant comically noting that he was sad when SSA stopped having Beethoven music while on hold). One participant shared positive views about the call-back system: “I'm pretty happy because they always call me back.”

Many participants expressed frustration in calling and getting different people each time who did not seem to know the participant record (prior calls, etc.). One older adult noted:

On the phone … you have to tell them a lot of details about your situation and everything else, over and over and over again, the same way, and then they usually say something like, ‘Gosh! You know my system's down,’ or ‘Gosh! Sorry, but you know I don't have that information,’ or ‘You're gonna get it in the mail,’ and that ‘You should get it within two weeks.’ And then you can talk to them two weeks later, saying that never came, ‘Oh, check back another month.’…. So, there's … a lot of waiting and not knowing and feeling vulnerable, feeling exposed. It's not particularly user friendly and very, I would say, uncomfortable on the whole. And so, nobody likes to ask for a handout. But when you're dealt the hand your dealt with, and you have to deal with life, it feels like it shouldn't have to be such a burden, but it is.

Similarly, a different participant noted:

Customer service is horrible... I understand the calls are recorded, but for some reason it's not getting to the Social Security Administration … They know nothing that I called, and I'm like, ‘well, I just called and tried to set up an appointment here, but you know nothing about it so…’ And they're … looking at me like I'm lying to them, and I'm like, ‘Man, I called, and they said to come in.’ So, you know, and they look at me like I'm just making something up trying to get in there, so on, you know. So, I'm not sure why the calls that you call the 1 800 number doesn't go to Concord [NH] or the main [local] offices. For some reason, I'm not sure where it goes. But there's no notes on their computer that I called or anything like [another participant] said, it's weird because you go in there [to the field office]. And then when they look at you like that, it's like I'm not trying to make something up. I was told to come in, you know.

Participants also noted frustration in receiving different answers from different SSA staff. “They're just as confused in person, usually. And then when you call on the phone, those are confused, too” said one participant. “And you can get, if you call three times about the same topic, you'll most likely get three different answers, because … I think the information on the whole system is so changeable, plus very vast, that any one person doesn't really know the answer to your question.”

2d. Participants noted some successes and some concerns with the disability accessibility within SSA processes and offices. Some people experienced higher compliance costs than others, related to the type of disability or limitations they experienced. Positively, one rural resident was pleased with how SSA accommodated his visual disability by calling him and reading aloud their letters to him. A person with a traumatic brain injury reported that even though “I sometimes have a hard time understanding things … they've always been willing to explain to (me).” Concerningly, one person with a musculoskeletal condition noted: “So, from the beginning of the process, there was a lot of paperwork. For me, it was, I found it to be overwhelming, especially [because] I couldn't use my hands, and everything is online now. So, I had to have someone do the paperwork for me. It was overwhelming, honestly, it was long and tedious, and I have major anxiety. So, it was very hard.” In terms of visual accessibility, one person mentioned a concern that “[It’s hard for] someone who can’t see very well to know that they’re supposed to rip the two sides and pop off to get [benefit information for a tax return]”. Another participant who had light sensitivity noted that the bright lighting at the field offices discouraged her from visiting the field office: “(To) go into the office can be difficult. It's way too bright.”

Theme Three: Beneficiary Concerns

3a. Participants expressed concerns related to not understanding SSA processes. These learning costs related to those who were receiving disability benefits in that many stated that they struggled to understand the processes related to working while receiving benefits. For some, this complexity served as a barrier to work: “I wanted to try going back to work. And I thought about calling them because it's hard. I looked into it on the website … It was confusing. Then I would just hold off.”

3b. Participants shared that they are worried about privacy and security concerns when dealing with SSA, particularly over the phone. This concern increases the psychological costs associated with accessing SSA benefits and services. Many residents had heard about the possibility of scams where bad actors pretended to be SSA and that SSA had been very clear with them that they would never text them. Some rural residents had been the victims of scams unrelated to Social Security, which increased their level of wariness. “I mean … I don't want to give out a lot of information on the computer”, said one resident. Another shared: “Yeah, I think they tell you straight up, we will never text you exactly, they've always said ‘we will not do this’. So, if you know, if you get a text, it's not them. They usually don't even call you unless you ask them to return a call. They don't bug you. Like right now on the internet it says, [though] if you want more money in your disability.something.something.com (click here).” One person stated: “If you get online and you're talking to somebody, how do you know you're talking to somebody at Social Security

(or) … on the other side of that phone, unless you're calling them? … That's why I'd rather go there and talk to somebody in person because then I know you're not going to rip me off. It's true.”

Theme Four: Technology Experience

4a.Most rural adults were not comfortable using technology to communicate with SSA. Some of their hesitation to use technology was related to concerns about scams but more often this hesitation occurred due to a lack of access to reliable technology and a lack of knowledge about how to use technology. “So elderly folks up here, many of them don't have computers. The only access could be at the local library. But they don't know how to use computers. So, having access at the local library is already a huge barrier,” stated one older adult. One woman described the challenges her husband faced in using technology to apply for retirement benefits: “For someone who's not super savvy [with computers] … it's not an easy process, and that was his only option as to how to apply was doing it online.”

4b.Smart phone access to SSA is not the answer. Many people had smart phones but were not savvy about using them (“But do I know how to really use my smartphone? That's a whole ‘nother story.”) or could not afford to use data on their phones (“Yeah, just because some people have smartphones doesn't mean that they have enough money for the data that can go on the internet.”). In addition, cell and internet service stability varied throughout these rural counties, with some people having stable service and others experiencing frequent (and sometimes multi-day) outages or spotty service. A few people mentioned still having land line telephones. When asked what participants would think if SSA developed an app to communicate with clients, one person stated: “I don't think I would get a straighter answer from an app. From the few apps that I do use and knowing that they're not perfect by any means, I don't know if I want to go to one more type of thing with the Social Security Administration. It's already confusing enough as it is.”

4c. Although they were in the minority among people we spoke with, rural residents who had higher levels of education and/or had work experience that involved working with computers were more willing to engage with technology to access information from or provide information to SSA. “I know there are some elderly people that don't want to be bothered with a cell phone or all of that, but I bank online and I love technology,” said one older adult who had worked for many years in the insurance industry.

4d. For people who were able to look at the SSA website, most did not find it to be user-friendly. Accessing the website did not lessen administrative burden. “To me, it hasn't worked out very well to try to get it through that way,” said one rural resident. Some found it confusing: “It's awfully confusing. I wouldn't get very far in the web,” said one older adult. Another stated: “Don't get me wrong, there's not, there's nothing wrong with how it's placed, but trying to navigate when you go on one page, and you're like, Oh, you have to go to another after you click on that and then go back because you have the wrong one. It's just all these pages are opening up.” One participant shared that she wished the website had more functionality: “I like their website, but it doesn't allow you to do everything through that.”

Theme Five: SSA Policy and Practices

5a.Efficiency. People who received either survivor or retirement benefits experienced lower levels of administrative burden. They were pleased with how efficient the application process was and particularly liked how their benefits were direct deposited each month. “I just love the fact I've never once had a problem with getting my Social Security in all those years,” said one participant who was speaking about her receipt of retirement benefits. She further stated “I just think that it’s doing the very best. I wish that all of the government services were as good as [the] Social Security Administration is.”

5b. Some disability benefit recipients expressed concerns about how the lengthy application and award process impacted their lives. One such person shared how delays in being awarded disability benefits and the requirement that he not work at all while he was waiting led to his imprisonment. He eventually had a lawyer helping him gather the necessary documentation but repeatedly got denied:

I had to wait three years, you know. Yes, you get a retro check and so on, but at that time I had to pay child support…. I was like ‘I'm not allowed to work.’ If I work … Social Security will deny you for trying to work, you know, and, you know, I was denied one time for that. Because I had no choice, I went to jail for almost six months because I couldn't pay my… child support which I was waiting for disability. So, I was in a weird situation then. But you know no one told me. No one from the community told me how it was, or so on. I had to figure it out myself by going to jail at least.

An older woman, who had work experience helping people apply for SSA disability benefits in addition to having lived experience in interacting with SSA, stated that “maybe SSA should streamline its disability determination process.” She continued:

So many people are denied and end up on appeal. I mean, I think I don't know what the percentage is anymore. I know it used to be pretty high. And then on appeal, they get it. And it doesn't make any sense to me that someone would have to go through the whole appeal process once or twice, even before they're eligible for benefits, because if they're eligible for benefits on appeal, they were eligible for benefits at application. And to me that's a waste of manpower in Social Security. And it's a waste and people who are applying for DI or SSI and doing it because they need the funds. And yes, I know it's retro, but retro doesn't help if you have to support a family. And what do you do in the meantime?

Theme Six: Recommendations to Improve the Beneficiary Experience.

6a. First, several people suggested that it would be helpful to have someone from SSA serve as a more personal advocate or come to people’s homes to help with applications and questions. As a way to reduce administrative burden, one person offered this suggestion:

Maybe Social Security ought to have an internal advocate or whatever that helps people, helps walk people through the system. So that they don't have to hire a lawyer, I mean, you know, that's not there to try and prevent benefits, but that's there to try, you know, … that person who (can) hold their hand through the process.

6b. Second, SSA should consider better ways to serve the population that is unhoused as the lack of physical address and place to receive mail is a large barrier to effective communication. Some wondered if the SSA field office could please receive and hold their mail for them. One person stated: “But it's not that easy. If Social Security says, oh, you don't have a physical address or you don't have a mailbox, we're not giving you your money. That's not right because then how am I going to be able to live.” Relying on a P.O. box was deemed too expensive:

And you need that check through the mail, then you have to rely on your family members or a P.O. box. And those P.O. boxes are not cheap because I used to do that too. It's $166 for a year. Yeah. I can't afford that just to get mail.

6c. Third, some participants suggested that benefit amounts were too low. In speaking about disability benefits, one person mentioned:

I think that every year they should increase. Right now, everything is so [expensive] right now and I only make so much a month and I can't do anything. And if you're only making, let's say 800 a month on your disability and everything is going up so high, you will never survive. And it's too bad that disability couldn't come up with a program that maybe every two years, we'll give you a $500 income [bonus]. Because the [way] that we're going right now and the way everything's going right now pretty soon we're going to be paying $5,000 a month (for rent) and there's no way on disability. Everybody on disability will end up wanting to be dead because you can't … we can't go buy groceries. You can't do anything on disability because once you pay your rent, your gas, everything else you're doing, you're broke.”

Another stated: “Yeah, I don't know how anyone with a family can live on disability.”

6d.One person suggested allowing for more time between deadlines stated in formal mail from SSA and mail receipt. While this person believed that sending information through the mail is the “traditional way that SSA communicates and is a good process,” this person stated that if SSA is requesting a “drastic change, [they] can’t send the letter and expect people to respond the same day they receive it. People work or may not get mail their mail regularly. They may need a few days or maybe up to ten days to respond.”

6e. In terms of community-level recommendations, most participants noted the general lack of social services available in their rural areas. One person who was unhoused stated:

You know, they b**** about all the homeless people here in this town, right? And all they do is just kick them out, arrest them. You got it here … Go, move, next town. That's not okay. We were here, we owned an apartment, you know, we lived here, we worked here, and somehow things get messed up and now we're homeless and you're just (shoving) us away, not helping us. That's wrong for the town to do. That's wrong for the state to do. And they all know it. So no, there's nothing here.

Another person stated that many social services agencies that serve older adults and people with disabilities are understaffed:

But you have less services here … [For example], we have home health [but] we don't have any workers. …Yes, you can get them to homes, you can get them to state independent living. But there's no one working for those people. So even though you qualify, you don't.

6f. As some rural residents are able to rely heavily on other community-based organizations or staff for assistance with SSA related tasks, many suggested expanding these options. For formal social network assistance with SSA-related tasks, some people relied on community-based case managers or social workers while others relied on staff at residential facilities. These types of supports did not seem to come from one particular type of community-based organization and access to these types of people seemed to vary greatly. One of our participants had prior experience as a town selectman and so was knowledgeable about government agencies and was able to help her friends. Overall, these ‘helpers’ provided different types of assistance, including helping people with phone calls (i.e., putting the phone on speaker so that the helper and the SSA client could jointly answer questions), taking people to the field office, navigating the internet, interpreting SSA communications, and preparing paperwork.

Stage 3 community-engagement. Upon completion of the qualitative analysis, we invited our initial set of twelve community members to help us review and verify the findings at a virtual meeting. In December 2024, we held the virtual Zoom meeting where the three primary research team members presented our preliminary themes and illustrative quotes to the subset of this group that chose to attend. We asked participants to react to the identified themes and to share policy and practice suggestions at the community and SSA levels.

These community members verified the validity of our findings, suggested further community-level and SSA-level recommendations, and provided ideas for dissemination of the study findings. In terms of community-level recommendations, these community members suggested that a ‘one stop’ way of providing services would be the most beneficial to this population as many people are involved with multiple service providers and systems who do not provide comprehensive assistance. Vocational rehabilitation was mentioned as a possible resource although these members did not view it as providing effective services in NH. New Hampshire’s ten Aging and Disability Resource Centers (e.g. Service Link) were mentioned although the community members stated that they primarily just provide referral services.

In terms of SSA-level recommendations, one community member questioned why SSA could not hold mail for people who are homeless and who do not have a physical address or mailbox, as a form of accommodation, as one of our focus group participants who had a visual limitation had noted that the field office received his SSA related mail and called and read it to him. Another community engagement member suggested that SSA staff ensure that they ask about need for all types of accommodations, not just physical or visual.

These community members thought that the findings of this study should be shared broadly including with NH field offices and regional (Boston) SSA staff, with community-based organizations in NH, and with school social workers so that parents of children with disabilities would be aware of some of complications they may face in accessing and maintaining SSA benefits.

Discussion

The results of this study extend prior research that has examined administrative burden and federal agency communication with target populations in rural areas by providing new information that is particularly relevant for agencies communicating with and serving people with disabilities and older adults who reside in rural areas of the U.S. We briefly summarize the key points from the findings from the focus group and interview participants discussed above, discuss some limitations of this study, and provide concluding remarks.

In general, this rural population is experiencing high levels of administrative burden when interacting with SSA. To alleviate this burden, older adults and people with disabilities residing in rural areas still very much prefer having access to a local field office where they can interact in-person with SSA staff. While other studies have documented the effects of field office closures on applications, backlog, and wait times (Deshpande & Li, 2019; Farid et al., 2024; Romig, 2023b), our study provides details about the first hand experiences of people who live in rural areas and who have been challenged by a lack of access to in-person services. The rural residents who participated in our study were generally very satisfied with in-person services and were glad to have this resource to help address the learning, compliance, and psychological costs associated with their interactions with government. Many residents reported using in-persons services to address questions that might arise when they receive information from SSA by other means. For example, rural residents who received information from SSA in the mail reported that they often needed to visit a field office in-person to have someone there help them to interpret the information they received from SSA or to address the administrative tasks necessary to maintain their benefits. While most (54%) of the rural residents we spoke with had only high school or less levels of education, this finding held true across educational levels.

The alternatives to in-person services were not effective in reducing administrative burden. If rural residents were not able to visit a field office, some tried to use the 800-number to contact SSA. In general, however, people were dissatisfied with SSA’s phone service given that they usually faced long wait times, didn’t know what questions to ask, didn’t have SSA staff who appeared to have electronic access to their call history, and sometimes received different answers from different staff. Others, who had access to the internet, attempted to use the SSA website but usually faced challenges in navigating the website. These findings about SSA phone and web-based services underscore the importance of having local field offices available.

High levels of administrative burden can provide negative consequences to the agencies in question. For example, in the study conducted here, high levels of administrative burden were noted as limiting whether people on disability benefits attempted to return to work. Lessening the administrative burden associated with decisions to attempt work could be expected then to increase the proportion of disability beneficiaries who are working. As another example, several participants noted issues with receiving overpayments of disability benefits from SSA, which creates more administrative work for SSA in correcting those overpayments and taking steps to collect the overpaid amounts from beneficiaries. Listening to the policy recommendations of people who have lived experience can provide some guidance about how to reduce administrative burden.

For most rural residents, travel burden was a concern and so many recommended increasing the availability of field offices in rural areas. These rural residents further advocated for increased community-based and SSA resources to assist with SSA tasks. At the state level, this may mean increasing the services available through existing disability and aging resource centers or through vocational rehabilitation, community mental health centers, area agencies on disability. At the SSA level, this may mean providing more SSA staff in rural areas to increase outreach and services, perhaps by having these staff interact more closely and on-site with senior centers, schools, or other community agencies. Rural residents also suggested that SSA improve the accessibility of its services for people with all types of disabilities.

Overall, people living in rural counties that do not have local SSA field offices voiced a distinct disadvantage in terms of knowing where to turn with questions about SSA disability, retirement, or survivors’ benefits. As these residents noted, a lack of ready and reliable access to information and advice led to endangering their own economic stability and to increased calls and visits to SSA.