Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

19 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wildfires

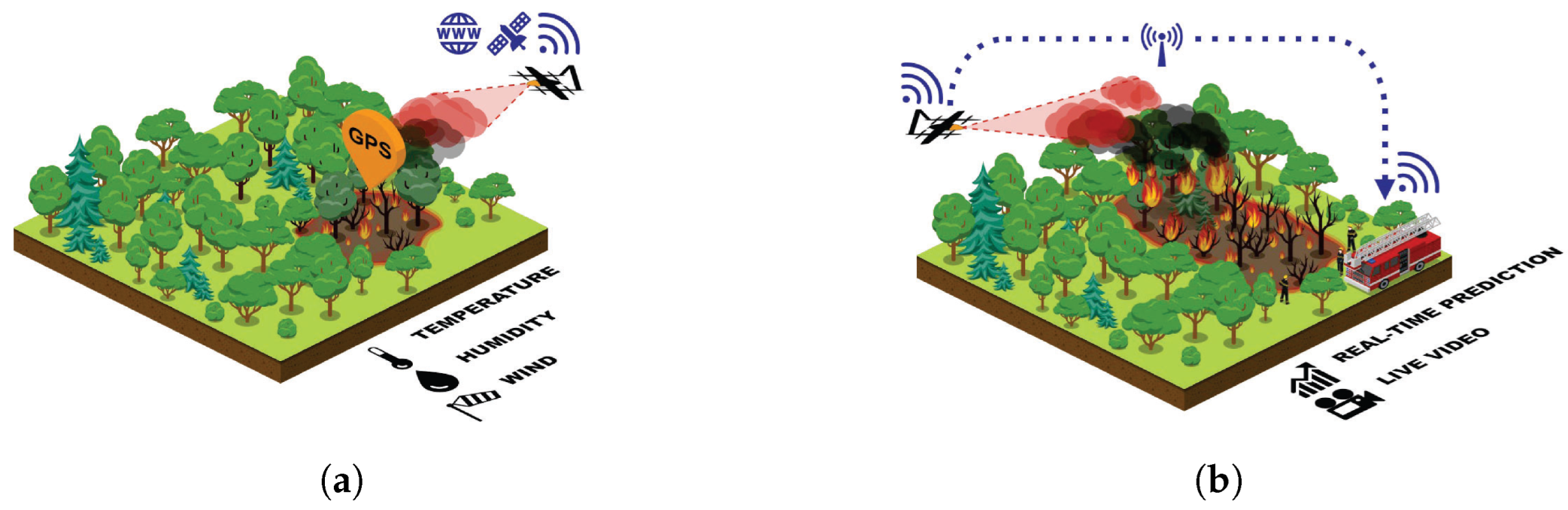

2.1.1. Wildfire Detection Methods

2.1.2. Wildfire Description

2.2. Evolonic

2.2.1. NF4 UAV

2.2.2. Automatic operations

2.2.3. Software Architecture

2.2.4. Test Flights

2.3. VLMs

2.3.1. Architectures

2.3.2. State of the Art Models

2.3.3. Prompting and Structured Outputs

2.3.4. Datasets

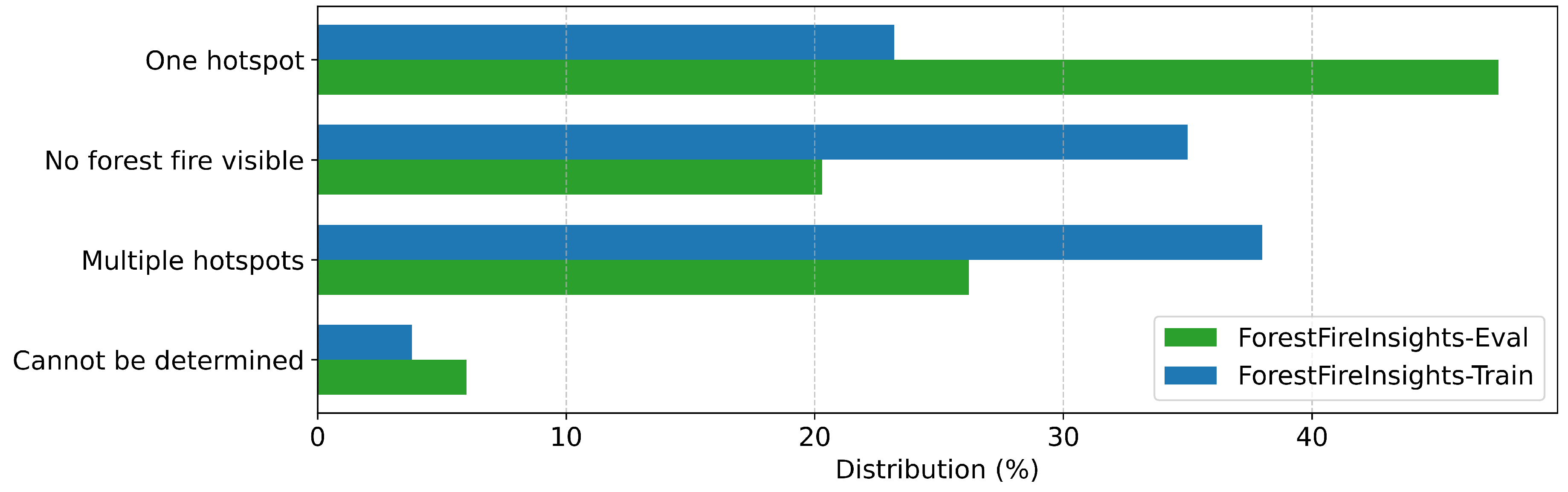

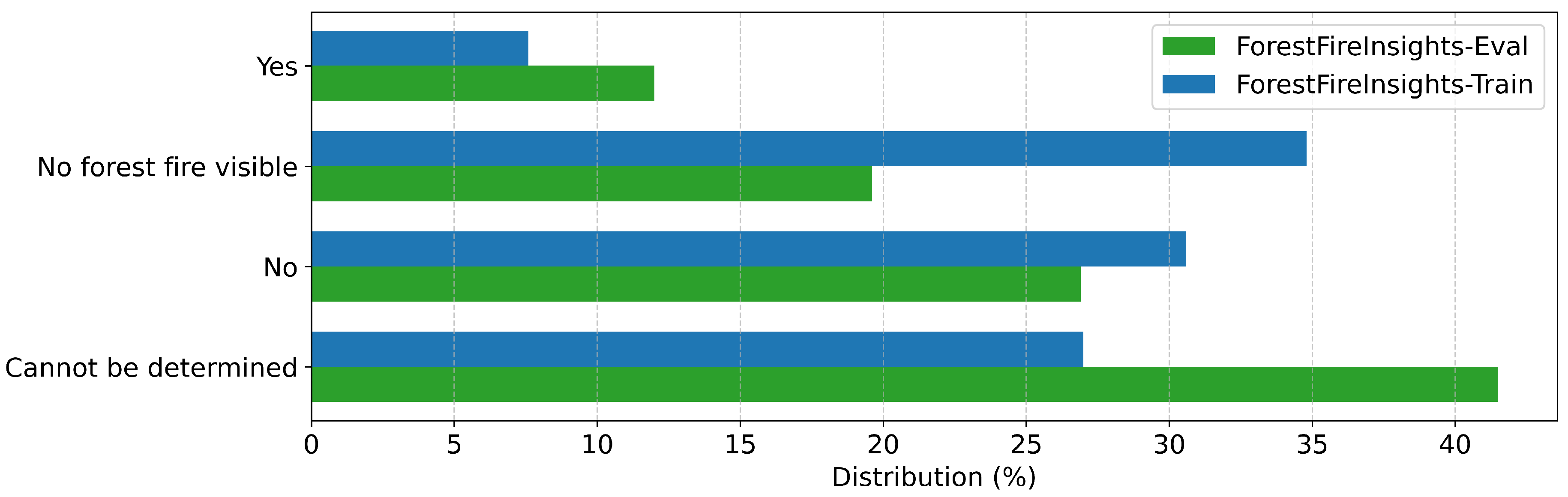

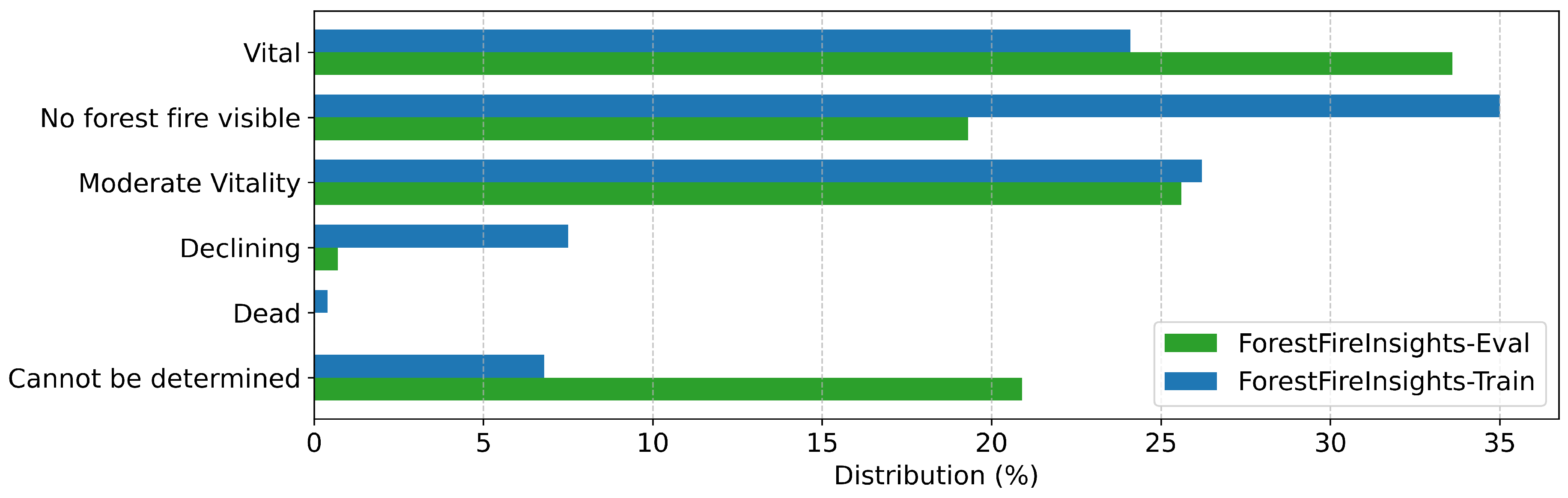

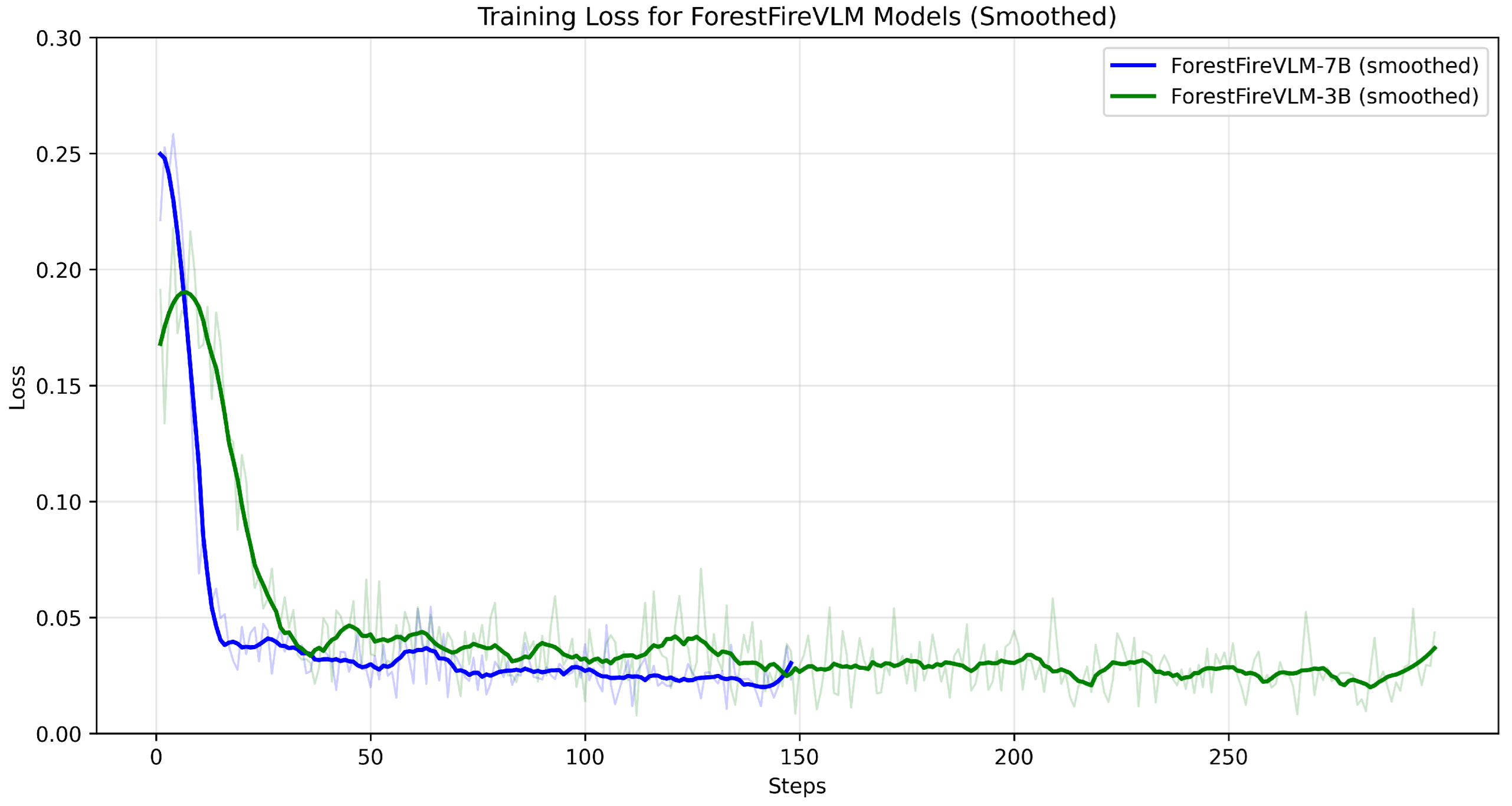

2.3.5. Training

2.3.6. Evaluation

2.3.7. Computing and API checkpoints

3. Results

3.1. ForestFireInsights-Eval

3.2. Examples

3.3. FIgLib Test Dataset

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Takeaways

4.2. Implications and Limitations

4.3. Future Work

5. Conclusion

- ForestFireVLM-7B and ForestFireVLM-3B, fine-tuned versions of their Qwen2.5-VL counterparts, publicly available for research and practical applications.

- A framework for detailed descriptions of forest fires in a structured format.

- Improving the VLM-based detection performance on the FIgLib dataset.

- A dedicated evaluation dataset for structured forest fire descriptions and accompanying code for future research in this domain.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LoRA | Low-Rank Adaption |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| VLM | Vision Language Model |

| VTOL | Vertical Takeoff And Landing |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

Appendix A

References

- Jones, M.W.; Kelley, D.I.; Burton, C.A.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Barbosa, M.L.F.; Brambleby, E.; Hartley, A.J.; Lombardi, A.; Mataveli, G.; McNorton, J.R.; et al. State of Wildfires 2023–2024. Earth System Science Data 2024, 16, 3601–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabokidis, K.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Moore, P.; Caballero, D.; Kallos, G.; Llorens, J.; Roussou, O.; Vasilakos, C. Decision support system for forest fire protection in the Euro-Mediterranean region. European Journal of Forest Research 2012, 131, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguettaya, A.; Zarzour, H.; Taberkit, A.M.; Kechida, A. A review on early wildfire detection from unmanned aerial vehicles using deep learning-based computer vision algorithms. Signal Processing 2022, 190, 108309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, A.; Pande, Y.; Braun, H.W.; Vernon, F.; Perez, I.; Altintas, I.; Cottrell, G.W.; Nguyen, M.H. FIgLib & SmokeyNet: Dataset and Deep Learning Model for Real-Time Wildland Fire Smoke Detection. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI.; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; et al. GPT-4 Technical Report.

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-VL Technical Report.

- Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Du Hongyang.; Nghiem, H.; Shi, G. Benchmark Evaluations, Applications, and Challenges of Large Vision Language Models: A Survey.

- Tao, L.; Zhang, H.; Jing, H.; Liu, Y.; Yan, D.; Wei, G.; Xue, X. Advancements in Vision–Language Models for Remote Sensing: Datasets, Capabilities, and Enhancement Techniques. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wen, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zhu, X.X. Vision-Language Models in Remote Sensing: Current progress and future trends. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2024, 12, 32–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Kulkarni, P. Enhancing the Binary Classification of Wildfire Smoke Through Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on AI, Science, Engineering, and Technology (AIxSET). IEEE, 2024, pp. 115–118. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D. Waldbrandfrüherkennung; W. Kohlhammer GmbH: Stuttgart, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, R. Alberta Wildfire Detection Challenge: Operational Demonstration of Six Wildfire Detection Systems; Vol. Technical Report; TR 2023 n.1, 2023.

- Alkhatib, A.A.A. A Review on Forest Fire Detection Techniques. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks 2014, 10, 597368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A.; Trinh, T. Early Wildfire Detection Technologies in Practice—A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göttlein, A.; Laniewski, R.; Brinkschulte, C.; Schwichtenberg, H. Praxistest eines Waldbrand-Frühwarnsystems. AFZ der Wald 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Blais, M.A.; Akhloufi, M.A. Drone Swarm Coordination Using Reinforcement Learning for Efficient Wildfires Fighting. SN Computer Science 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronto, L.; Held, A. Einführung in das Feuerverhalten, 2021.

- Saxena, S.; Dubey, R.; Yaghoobian, N. A Model for Predicting Ignition Potential of Complex Fuel in. PhD thesis, Florida State University, Florida, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cimolino, U. Analyse der Einsatzerfahrungen und Entwicklung von Optimierungsmöglichkeiten bei der Bekämpfung von Vegetationsbränden in Deutschland. Dissertation, Universität Wuppertal, Wuppertal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patzelt, S.T. Waldbrandprognose und Waldbrandbekämpfung in Deutschland - zukunftsorientierte Strategien und Konzepte unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Brandbekämpfung aus der Luft. Dissertation, Johannes Gutenberg Universität, Mainz, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher Feuerwehrverband. Anzahl der Feuerwehren, 2023.

- Tielin, M.; Chuanguang, Y.; Wenbiao, G.; Zihan, X.; Qinling, Z.; Xiaoou, Z., Eds. Proceedings of 2017 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS): Oct. 27-29, 2017, Beijing, China; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, 2017.

- Laurençon, H.; Tronchon, L.; Cord, M.; Sanh, V. What matters when building vision-language models?

- Duan, H.; Fang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhao, X.; Qiao, Y.; Li, M.; Agarwal, A.; Chen, Z.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. VLMEvalKit: An Open-Source Toolkit for Evaluating Large Multi-Modality Models.

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.; Luo, Z.; Feng, Z.; Ma, Y. LlamaFactory: Unified Efficient Fine-Tuning of 100+ Language Models.

- Daniel Han, M.H.; Unsloth team. Unsloth, 2023.

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Cui, E.; Zhu, J.; Ye, S.; Tian, H.; Liu, Z.; et al. Expanding Performance Boundaries of Open-Source Multimodal Models with Model, Data, and Test-Time Scaling.

- Yue, X.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, T.; Liu, R.; Zhang, G.; Stevens, S.; Jiang, D.; Ren, W.; Sun, Y.; et al. MMMU: A Massive Multi-discipline Multimodal Understanding and Reasoning Benchmark for Expert AGI.

- Zhang, Y.F.; Zhang, H.; Tian, H.; Fu, C.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Li, F.; Wang, K.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; et al. MME-RealWorld: Could Your Multimodal LLM Challenge High-Resolution Real-World Scenarios that are Difficult for Humans?

- Center for Wildfire Research, University of Split. FESB MLID dataset, 3/13/2025.

- Krstinić, D.; Stipaničev, D.; Jakovčević, T. Histogram-based smoke segmentation in forest fire detection system; 2009.

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models.

- Dettmers, T.; Pagnoni, A.; Holtzman, A.; Zettlemoyer, L. QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs.

- Kwon, W.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, S.; Sheng, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yu, C.H.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Zhang, H.; Stoica, I. Efficient Memory Management for Large Language Model Serving with PagedAttention.

- Wang, P.; Bai, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, S.; Fan, Z.; Bai, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; et al. Qwen2-VL: Enhancing Vision-Language Model’s Perception of the World at Any Resolution.

| Field | Question | Options |

|---|---|---|

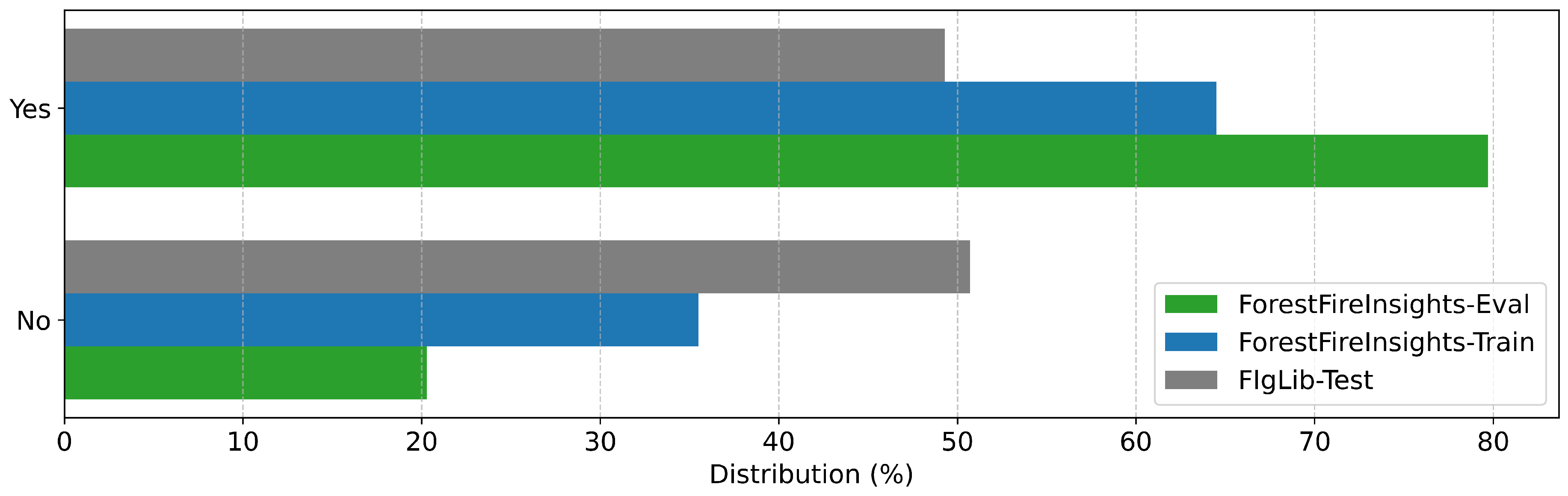

| Smoke | Is smoke from a forest fire visible in the image? | Yes, No |

| Flames | Are flames from a forest fire visible in the image? | Yes, No |

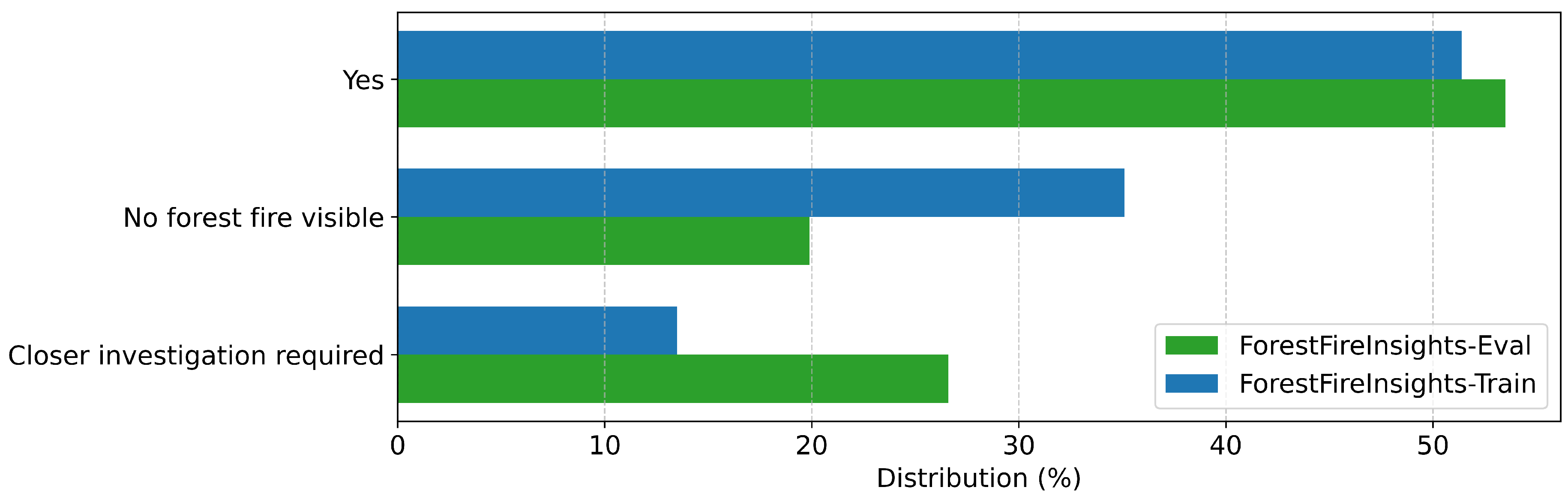

| Uncontrolled | Can you confirm that this is an uncontrolled forest fire? | Yes, Closer investigation required, No forest fire visible |

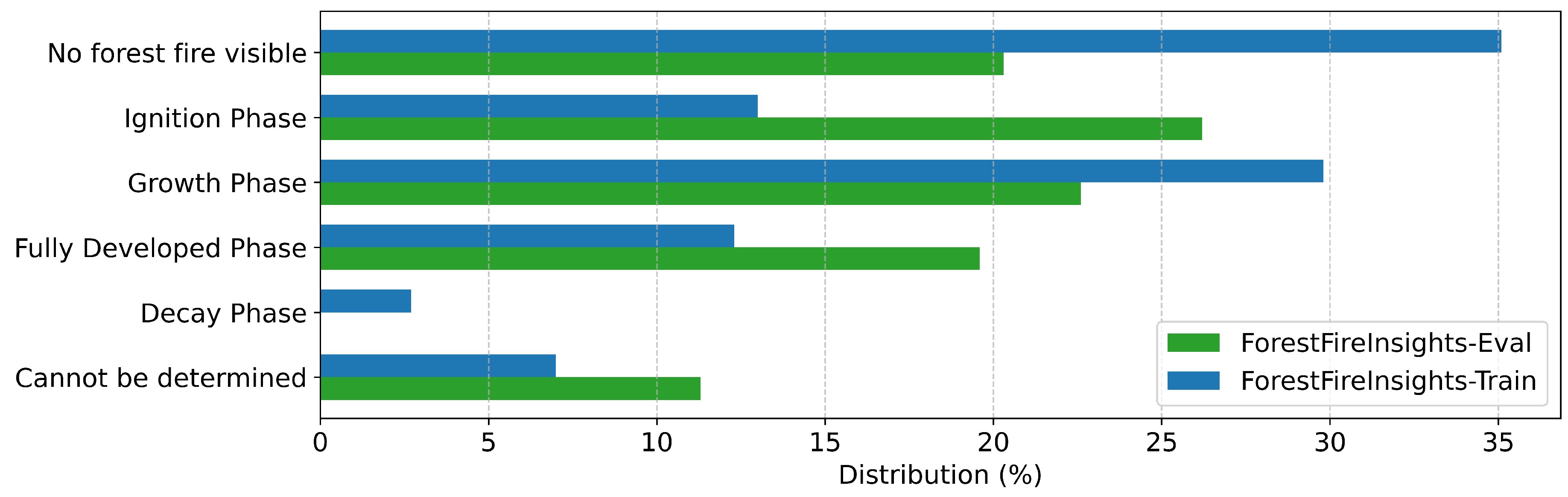

| Fire State | What is the current state of the forest fire? | Ignition Phase, Growth Phase, Fully Developed Phase, Decay Phase, Cannot be determined, No forest fire visible |

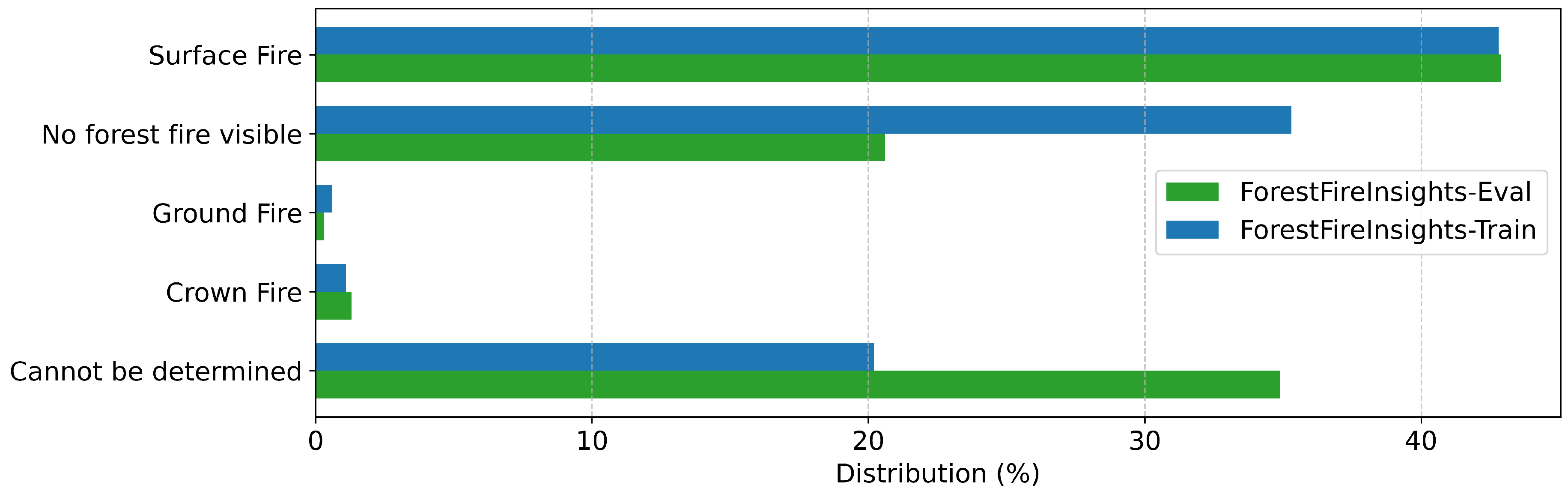

| Fire Type | What type of fire is it? | Ground Fire, Surface Fire, Crown Fire, Cannot be determined, No forest fire visible |

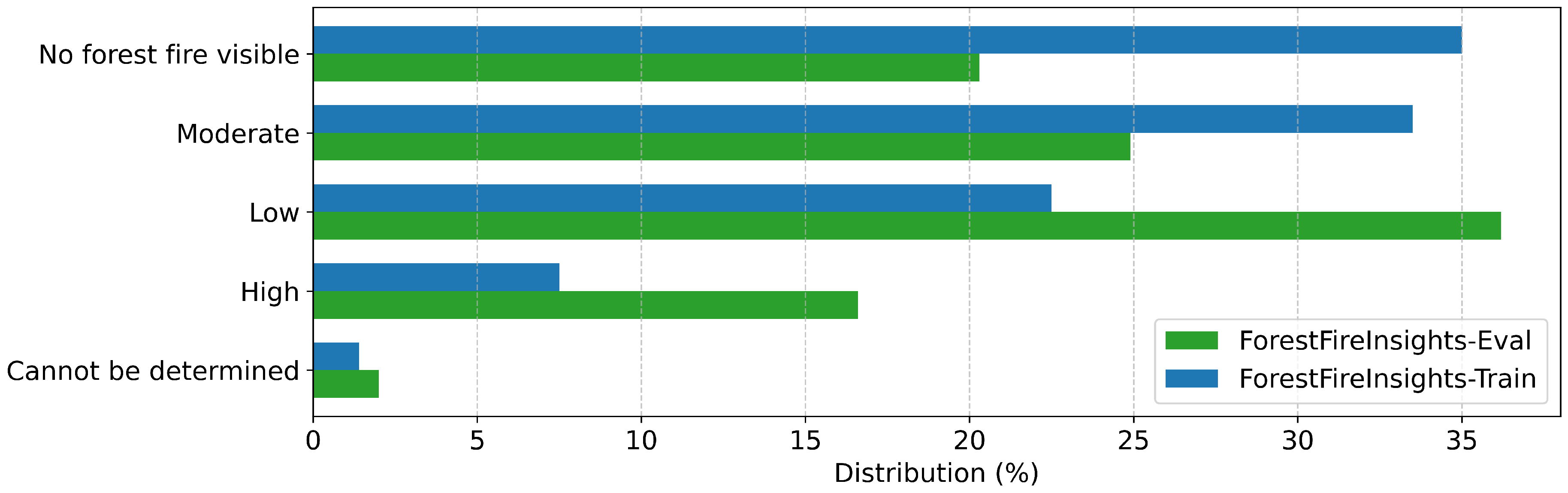

| Fire Intensity | What is the intensity of the fire? | Low, Moderate, High, Cannot be determined, No forest fire visible |

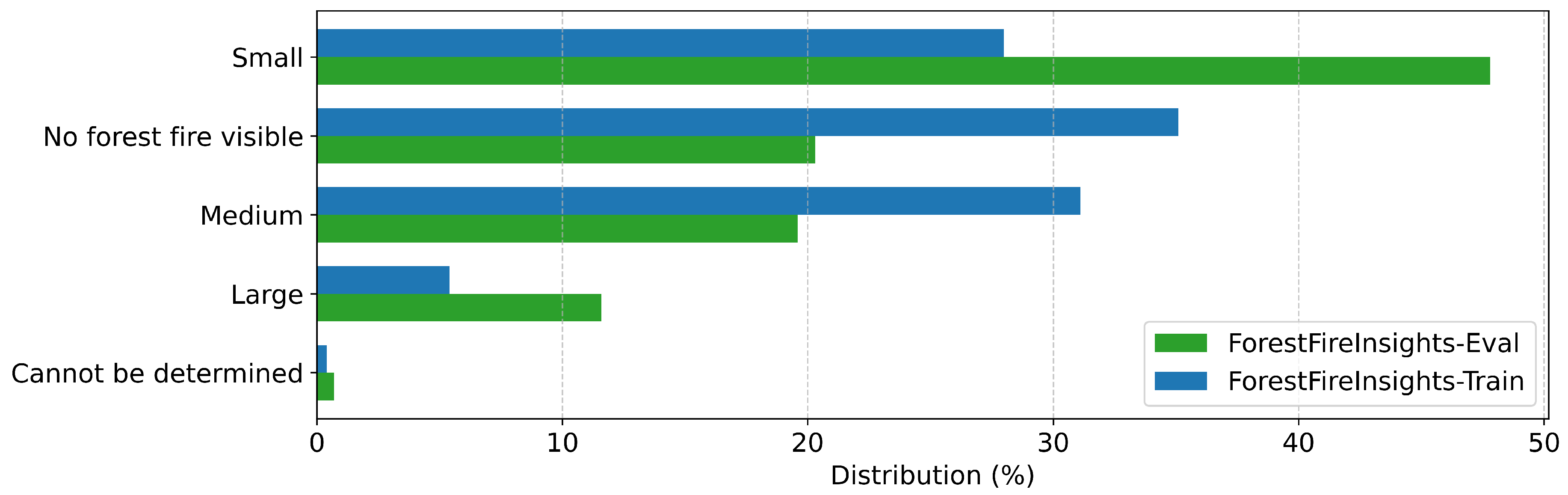

| Fire Size | What is the size of the fire? | Small, Medium, Large, Cannot be determined, No forest fire visible |

| Fire Hotspots | Does the forest fire have multiple hotspots? | Multiple hotspots, One hotspot, Cannot be determined, No forest fire visible |

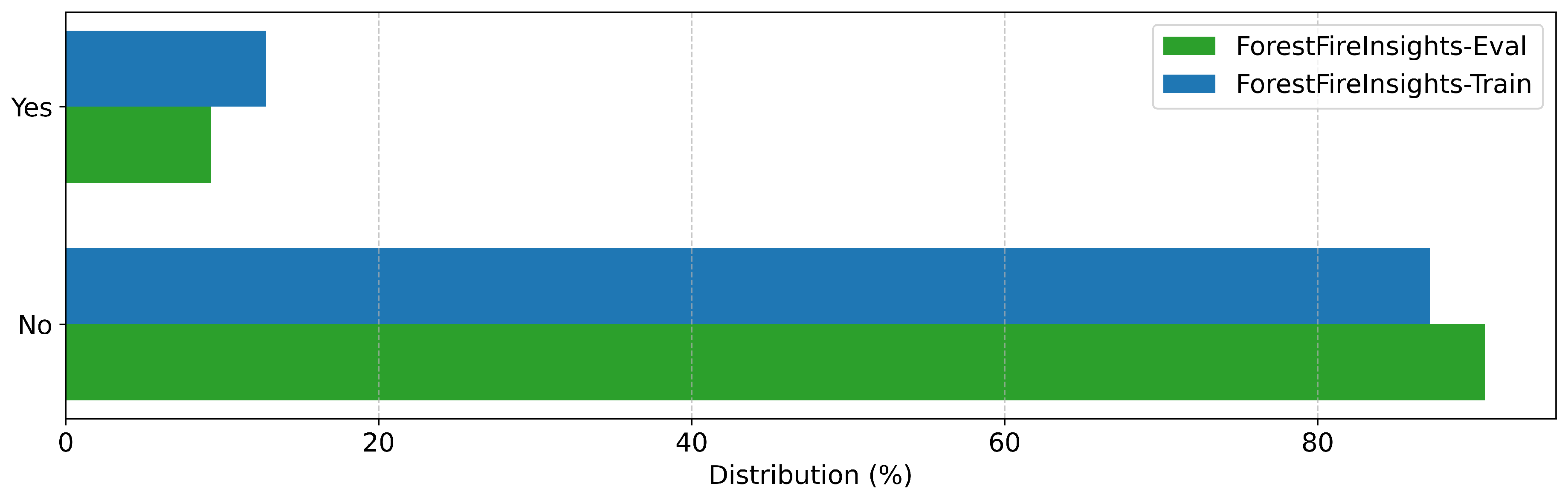

| Infrastructure Nearby | Is there infrastructure visible near the forest fire? | Yes, No, Cannot be determined, No forest fire visible |

| People Nearby | Are there people visible near the forest fire? | Yes, No, Cannot be determined, No forest fire visible |

| Tree Vitality | Describe the vitality of the trees around the fire. | Vital, Moderate Vitality, Declining, Dead, Cannot be determined, No forest fire visible |

| Setting | ForestFireVLM-3B | ForestFireVLM-7B |

|---|---|---|

| Learning rate | 0.00005 | 0.0002 |

| Epochs | 2 | 2 |

| Batch Size | 1 | 1 |

| Gradient Accumulation | 8 Steps | 16 Steps |

| GPU | NVIDIA RTX 3090 | NVIDIA A100 80GB |

| Model | Version or checkpoint |

|---|---|

| Gemini Pro 1.5 | Version 002 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 | Version 001 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 Lite | Version 001 |

| Gemini Pro 2.0 | Experimental 2025-02-05 |

| GPT-4o | 2024-08-06 |

| GPT-4o mini | 2024-07-18 |

| Model | Flames (%) | Smoke (%) | Uncontrolled (%) | Average (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ForestFireVLM-7B | 98.0 | 95.0 | 77.1 | 90.0 |

| ForestFireVLM-3B | 96.0 | 95.4 | 75.8 | 89.0 |

| Gemini Pro 1.5 | 94.7 | 91.4 | 65.1 | 83.7 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 | 96.4 | 95.0 | 75.4 | 88.9 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 Lite | 96.7 | 93.7 | 58.8 | 83.1 |

| Gemini Pro 2.0 | 90.4 | 95.7 | 53.2 | 79.7 |

| GPT-4o | 95.7 | 94.7 | 47.5 | 79.3 |

| GPT-4o mini | 95.0 | 94.7 | 43.9 | 77.9 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-3B | 93.4 | 92.0 | 39.2 | 74.9 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-7B | 92.7 | 79.7 | 32.2 | 68.2 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-72B | 93.7 | 83.4 | 34.6 | 70.5 |

| Model | Fire Hotspots (%) | Fire Intensity (%) | Fire Size (%) | Average (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ForestFireVLM-7B | 78.1 | 74.1 | 81.1 | 77.7 |

| ForestFireVLM-3B | 82.1 | 69.8 | 80.4 | 77.4 |

| Gemini Pro 1.5 | 69.1 | 48.5 | 51.5 | 56.4 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 | 58.8 | 34.2 | 51.2 | 48.1 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 Lite | 79.4 | 47.2 | 67.4 | 64.7 |

| Gemini Pro 2.0 | 76.7 | 63.1 | 74.1 | 71.3 |

| GPT-4o | 26.3 | 21.9 | 21.6 | 23.3 |

| GPT-4o mini | 35.6 | 26.6 | 27.9 | 30.0 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-3B | 55.8 | 37.9 | 38.2 | 44.0 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-7B | 9.0 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 5.6 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-72B | 28.6 | 21.9 | 21.6 | 24.0 |

| Model | Fire State (%) | Fire Type (%) | Average (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ForestFireVLM-7B | 64.1 | 71.8 | 67.9 |

| ForestFireVLM-3B | 61.5 | 68.1 | 64.8 |

| Gemini Pro 1.5 | 41.5 | 63.5 | 52.5 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 | 44.5 | 62.1 | 53.3 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 Lite | 46.5 | 63.8 | 55.2 |

| Gemini Pro 2.0 | 53.5 | 66.5 | 60.0 |

| GPT-4o | 29.9 | 52.2 | 41.0 |

| GPT-4o mini | 31.9 | 55.8 | 43.9 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-3B | 36.9 | 38.2 | 37.5 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-7B | 12.0 | 34.6 | 23.3 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-72B | 28.9 | 47.8 | 38.4 |

| Model | Infrastructure Nearby (%) | People Nearby (%) | Tree Vitality (%) | Average (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ForestFireVLM-7B | 74.1 | 66.1 | 62.8 | 67.7 |

| ForestFireVLM-3B | 74.4 | 58.5 | 61.5 | 64.8 |

| Gemini Pro 1.5 | 66.5 | 57.5 | 44.9 | 56.3 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 | 70.1 | 56.5 | 60.8 | 62.5 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 Lite | 51.2 | 37.5 | 30.6 | 39.8 |

| Gemini Pro 2.0 | 60.1 | 43.2 | 43.5 | 48.9 |

| GPT-4o | 31.9 | 52.8 | 39.9 | 41.5 |

| GPT-4o mini | 33.2 | 47.5 | 41.9 | 40.9 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-3B | 56.2 | 32.6 | 32.2 | 40.3 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-7B | 51.2 | 44.9 | 20.9 | 39.0 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-72B | 62.5 | 44.2 | 49.2 | 51.9 |

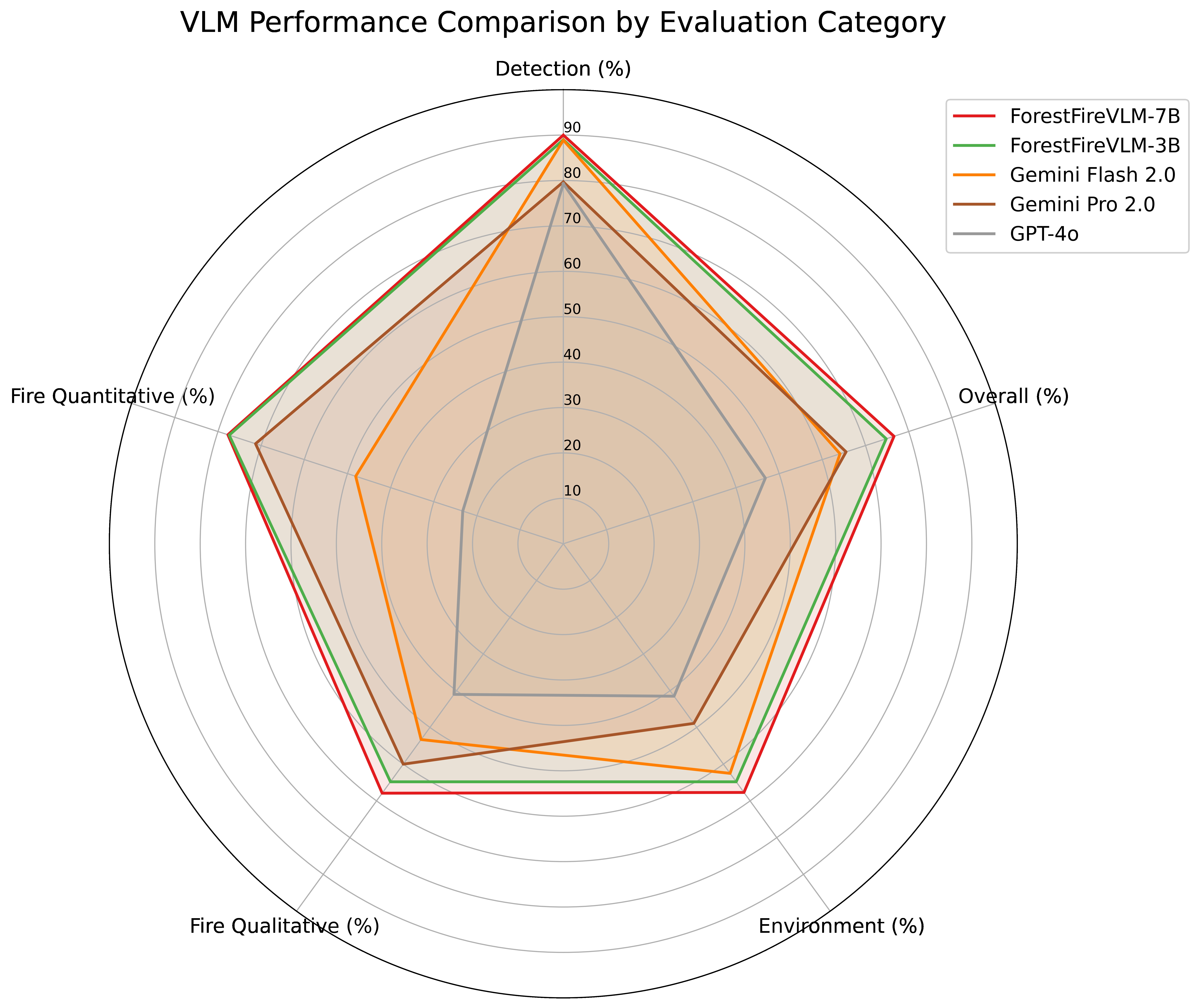

| Model | Detection (%) | Fire Quantitative (%) | Fire Qualitative (%) | Environ-mental (%) | Overall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ForestFireVLM-7B | 90.0 | 77.7 | 67.9 | 67.7 | 76.6 |

| ForestFireVLM-3B | 89.0 | 77.4 | 64.8 | 64.8 | 74.8 |

| Gemini Pro 1.5 | 83.7 | 56.4 | 52.5 | 56.3 | 63.1 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 | 88.9 | 48.1 | 53.3 | 62.5 | 64.1 |

| Gemini Flash 2.0 Lite | 83.1 | 64.7 | 55.2 | 39.8 | 61.2 |

| Gemini Pro 2.0 | 79.7 | 71.3 | 60.0 | 48.9 | 65.5 |

| GPT-4o | 79.3 | 23.3 | 41.0 | 41.5 | 46.8 |

| GPT-4o mini | 77.9 | 30.0 | 43.9 | 40.9 | 48.5 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-3B | 74.9 | 44.0 | 37.5 | 40.3 | 50.2 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-7B | 68.2 | 5.6 | 23.3 | 39.0 | 35.0 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-72B | 70.5 | 24.0 | 38.4 | 51.9 | 46.9 |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ForestFireVLM-7B | 78.5 | 98.6 | 57.2 | 72.4 |

| ForestFireVLM-3B | 76.3 | 98.8 | 52.6 | 68.6 |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro | 70.0 | 100.0 | 39.2 | 56.3 |

| Gemini 2.0 Flash | 74.1 | 96.9 | 49.1 | 65.2 |

| Gemini 2.0 Flash Lite | 71.5 | 95.6 | 44.2 | 60.5 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-3B | 70.4 | 91.3 | 44.1 | 59.5 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-7B | 60.3 | 100.0 | 19.5 | 32.7 |

| PaliGemma [10] | 52.1 | 100.0 | 3.0 | 5.7 |

| Phi3 [10] | 52.6 | 100.0 | 4.0 | 7.6 |

| GPT-4o [10] | 74.5 | 95.2 | 50.6 | 66.1 |

| LLaVA 7B [10] | 67.5 | 87.6 | 39.2 | 54.1 |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ForestFireVLM-7B | 78.5 | 98.6 | 57.2 | 72.4 |

| ForestFireVLM-3B | 76.3 | 98.8 | 52.6 | 68.6 |

| Human (average of 3) [4] | 78.5 | 93.5 | 74.4 | 82.8 |

| SmokeyNet (1 frame) [4] | 82.5 | 88.6 | 75.2 | 81.3 |

| SmokeyNet (3 frames) [4] | 83.6 | 90.9 | 76.1 | 82.8 |

| LLaVA (Horizon Tiling) [10] | 81.4 | 86.5 | 73.7 | 79.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).