Introduction

The frequency and intensity of wildfires have seen an alarming increase in recent years, leading to catastrophic consequences for both the environment and human society. The devastating wildfires that have swept across regions like Australia, California, and the Amazon rainforest have caused significant loss of life, destroyed vast areas of forest, and resulted in billions of dollars in economic damage. These events have underscored the pressing need for effective wildfire detection and response systems. Climate change, with its associated increase in temperatures and prolonged dry seasons, is expected to exacerbate these conditions, making wildfires more severe and frequent in the coming years [

1,

2,

3].

The traditional methods of wildfire detection have relied heavily on ground-based observations, human patrols, and remote sensing technologies like satellite imagery and thermal sensors. While these methods have been somewhat effective, they are often limited by their inability to provide timely and accurate information over vast areas. Satellite images, for instance, can offer a broader view but often lack the spatial resolution and timeliness required for early detection and rapid response [

4,

5,

6].

In recent years, Machine Learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool for automating the detection of wildfires. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been at the forefront of these efforts, demonstrating their ability to analyze complex spatial patterns in satellite and aerial imagery. However, despite their promise, CNNs are often constrained by their limited capacity to capture long-range dependencies and intricate spatial relationships in high-resolution images [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

In response to these challenges, we propose FlameViT, an innovative wildfire detection architecture based on Vision Transformers (ViT). This approach leverages the strengths of transformer models, which have revolutionized natural language processing (NLP) tasks through their self-attention mechanisms, to address the specific needs of wildfire detection. By applying these principles to visual data, FlameViT can effectively capture the complex spatial dependencies present in satellite images, making it a powerful tool for early wildfire detection.

Literature Work

The task of wildfire detection has been addressed through various machine learning approaches over the years. Machine learning approaches have emerged as powerful tools for wildfire detection, offering improved accuracy and efficiency. Random forests and support vector machines (SVMs) have been applied to classify satellite images and predict fire-prone areas [

11,

12]. These methods can handle large datasets and complex patterns, but they often require manual feature extraction and may struggle with highly dynamic and non-linear data typical of wildfire scenarios.

Deep learning methods, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have further enhanced the ability to analyze complex spatial patterns in large datasets [

13]. CNNs excel at automatic feature extraction and have been extensively used for image classification tasks, including wildfire detection. Notable architectures such as AlexNet [

14], VGGNet [

15], and ResNet [

16] have demonstrated significant success in various computer vision applications.

Recent advancements have seen the development of hybrid models combining CNNs with other machine learning techniques to improve wildfire detection accuracy. For instance, the integration of CNNs with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks has been explored to capture temporal dependencies in wildfire data [

17,

18]. These hybrid models leverage the strengths of both CNNs and RNNs, providing a more holistic approach to wildfire prediction by considering both spatial and temporal aspects.

Attention mechanisms have been incorporated into deep learning models to enhance their focus on relevant parts of the input data. The use of spatial attention in CNNs has shown promise in improving the detection of small and complex fire patterns in satellite images [

19]. This aligns with the broader trend of integrating attention-based methods in computer vision tasks. For example, Zhang et al. [

19] demonstrated that incorporating spatial attention mechanisms into CNNs significantly improved wildfire detection accuracy by enabling the model to focus on critical regions in the imagery.

The application of Vision Transformers to wildfire detection represents a novel approach that leverages the strengths of transformers in capturing long-range dependencies. Vision Transformers, with their ability to process image patches as sequences, offer a distinct advantage over traditional CNNs in handling high-resolution satellite imagery. Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Vision Transformers in various image classification tasks, indicating their potential for wildfire detection [

20,

21]. Unlike CNNs, which may struggle with capturing global context, transformers excel in modeling global interactions due to their self-attention mechanism [

22].

The advancement of deep learning methods, particularly the development of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has significantly improved the ability to analyze and interpret large volumes of satellite and aerial imagery for wildfire detection [

23]. CNNs, such as GoogleNet [

23] and DenseNet [

24], have achieved state-of-the-art performance in image classification tasks and have been adapted for wildfire detection [

23,

24].

Despite the success of CNNs, they have inherent limitations in capturing long-range dependencies and global context in high-resolution images [

13]. Transformers, with their self-attention mechanism, offer a promising alternative by modeling global interactions and capturing intricate spatial relationships [

25]. The Vision Transformer (ViT) and its variants have shown that transformers can achieve competitive performance in image classification tasks, even surpassing CNNs in certain scenarios [

21,

22].

Vision Transformers, such as the Vision Transformer (ViT), process images by dividing them into patches and treating each patch as a token in a sequence [

22]. This approach allows the model to capture long-range dependencies and global context more effectively than traditional CNNs. Studies have shown that Vision Transformers can achieve state-of-the-art performance in various image analysis tasks, including object detection, segmentation, and classification [

21,

22].

The use of Vision Transformers in wildfire detection represents a significant advancement over traditional methods. By leveraging the strengths of transformers in capturing complex spatial dependencies and global context, Vision Transformers can provide more accurate and efficient wildfire detection and prediction [

22]. The proposed model, FlameViT, builds on these advancements, demonstrating the potential of Vision Transformers to enhance wildfire detection accuracy and efficiency.

The reviewed literature underscores the evolution of wildfire detection methods from traditional remote sensing techniques to advanced machine learning approaches. Vision Transformers, with their superior ability to capture complex spatial dependencies, represent a significant leap forward in this domain. Our proposed model, FlameViT, builds on these advancements, demonstrating the potential of Vision Transformers to enhance wildfire detection accuracy and efficiency.

Proposed Model

The proposed model, FlameViT, leverages the Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture for the specific task of detecting wildfire smoke in high-resolution satellite images. This task is crucial as early detection of wildfire smoke can significantly enhance firefighting efforts and mitigate the destructive impact of wildfires. The model is designed to process satellite imagery, extracting patches and embedding them into a feature space, followed by multiple transformer encoder layers to capture complex spatial dependencies inherent in such data.

Data Preparation

The dataset comprises 40,000+ satellite images, each 350 x 350 pixels in size, labeled as either ’wildfire’ (indicating presence of wildfire smoke) or ’no wildfire’ (indicating absence of smoke). The data is preprocessed and augmented to improve model robustness, ensuring that the model generalizes well to new, unseen data.

Patch Extraction and Embedding

We divide each input image into non-overlapping patches of size P X P. This step transforms the 2D spatial information into a sequence of flattened patches suitable for transformer processing.

Where H and W are the height and width of the image, respectively. The patches are then embedded into a higher-dimensional space:

where W

e is the embedding matrix and e

pos(i) is the positional encoding. The positional encoding e

pos(i) is added to retain spatial information and is defined as:

Where i is the position, j is the dimension, and d is the embedding dimension.

FlameViT Model Architecture

The overall architecture of FlameViT integrates the components described above to form a cohesive model for wildfire smoke detection.

Where x is the input image,

is the initial patch embedding, and

is the output of the l-th transformer layer. The final representation is obtained by taking the mean of the encoded patches:

The final classification is obtained through a softmax layer:

Where and are the weights and biases of the classification layer, respectively.

Hyperparameter Tuning

Hyperparameter tuning is a critical step in optimizing the performance of the FlameViT model. We specifically tuned the following hyperparameters to achieve the best possible accuracy in detecting wildfire smoke:

Patch Size (P): The size of each image patch is crucial as it determines the granularity of the input data. Smaller patches provide finer details, while larger patches reduce the computational complexity. We experimented with patch sizes P Ꜫ{8, 16, 32} as per equation 1.

Projection Dimension (d): The dimension to which each patch is projected before being fed into the transformer encoder. This affects the capacity of the model to learn representations. We tested projection dimensions d Ꜫ {32, 64, 128} as per equation 2.

Number of Attention Heads (h): The number of parallel attention mechanisms in the multi-head attention layer. More heads allow the model to focus on different parts of the input. We considered h Ꜫ {4, 8} as per equation 6.

MLP Dimension (): The number of neurons in the hidden layer of the feed-forward network within the transformer encoder. This impacts the model’s capacity to learn complex transformations. We experimented with Ꜫ {128, 256} as per equation 8.

Number of Layers (L): The depth of the transformer, i.e., the number of stacked transformer encoder layers. More layers typically enhance the model’s ability to capture hierarchical features. We tested L Ꜫ {1, 2, 4} as per equation 11.

Dropout Rate (p): The dropout rate used to prevent overfitting by randomly setting a fraction of input units to zero during training. We considered p Ꜫ {0.0, 0.1, 0.2}.

The hyperparameter tuning process involved conducting a grid search over the specified ranges. The objective function for the tuning was to maximize the validation accuracy:

Where represents the set of hyperparameters being optimized. The hyperparameter search was performed using Bayesian optimization, which balances exploration and exploitation to efficiently search the hyperparameter space.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter values tested for tuning process.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter values tested for tuning process.

| Hyperparameter |

Values Tested |

| Patch Size (P) |

{8, 16, 32} |

| Projection Dimension (d) |

{32, 64, 128} |

| Number of Attention Heads (h) |

{4, 8} |

| MLP Dimension () |

{128, 256} |

| Number of Layers (L) |

{1, 2, 4} |

| Dropout Rate (p) |

{0.0, 0.1, 0.2} |

These hyperparameters were tuned to achieve the highest possible validation accuracy, ensuring the FlameViT model is well-optimized for wildfire smoke detection tasks.

Training Procedure

The model is trained using the Adam optimizer with a cross-entropy loss function, which is suitable for binary classification tasks like wildfire smoke detection.

The optimization algorithm is defined as:

where

is the learning rate, and

and

are the first and second moment estimates.

Model Evaluation

Model performance is evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

Experiments and Results

Experimental Setup

The dataset is sourced from Canada’s Open Government Portal and includes images captured during wildfire events and non-fire conditions.

To improve the generalization of our model, we applied various data augmentation techniques using the ImageDataGenerator class in TensorFlow. The augmentation techniques used include:

Rescaling: Pixel values are rescaled by a factor of 1/255 to normalize the input images.

Rotation: Images are randomly rotated by up to 20 degrees.

Width and Height Shifts: Images are randomly shifted horizontally and vertically by up to 20% of the total width and height, respectively.

Shear: Shear transformations are applied to the images by up to 20 degrees.

Zoom: Images are randomly zoomed in by up to 20%.

Horizontal Flip: Images are randomly flipped horizontally.

The dataset is split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets to ensure that the model is evaluated on unseen data.

Model was trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001. The loss function used was sparse categorical cross-entropy. The model was trained for 20 epochs with a batch size of 32. Early stopping and model checkpoint callbacks were employed to prevent overfitting and save the best model based on validation loss.

Results

The hyperparameter tuning process identified the following optimal values, as shown in

Table 2:

The final FlameViT model achieved a validation accuracy of 95%, significantly outperforming a benchmark CNN model which had an accuracy of 86%.

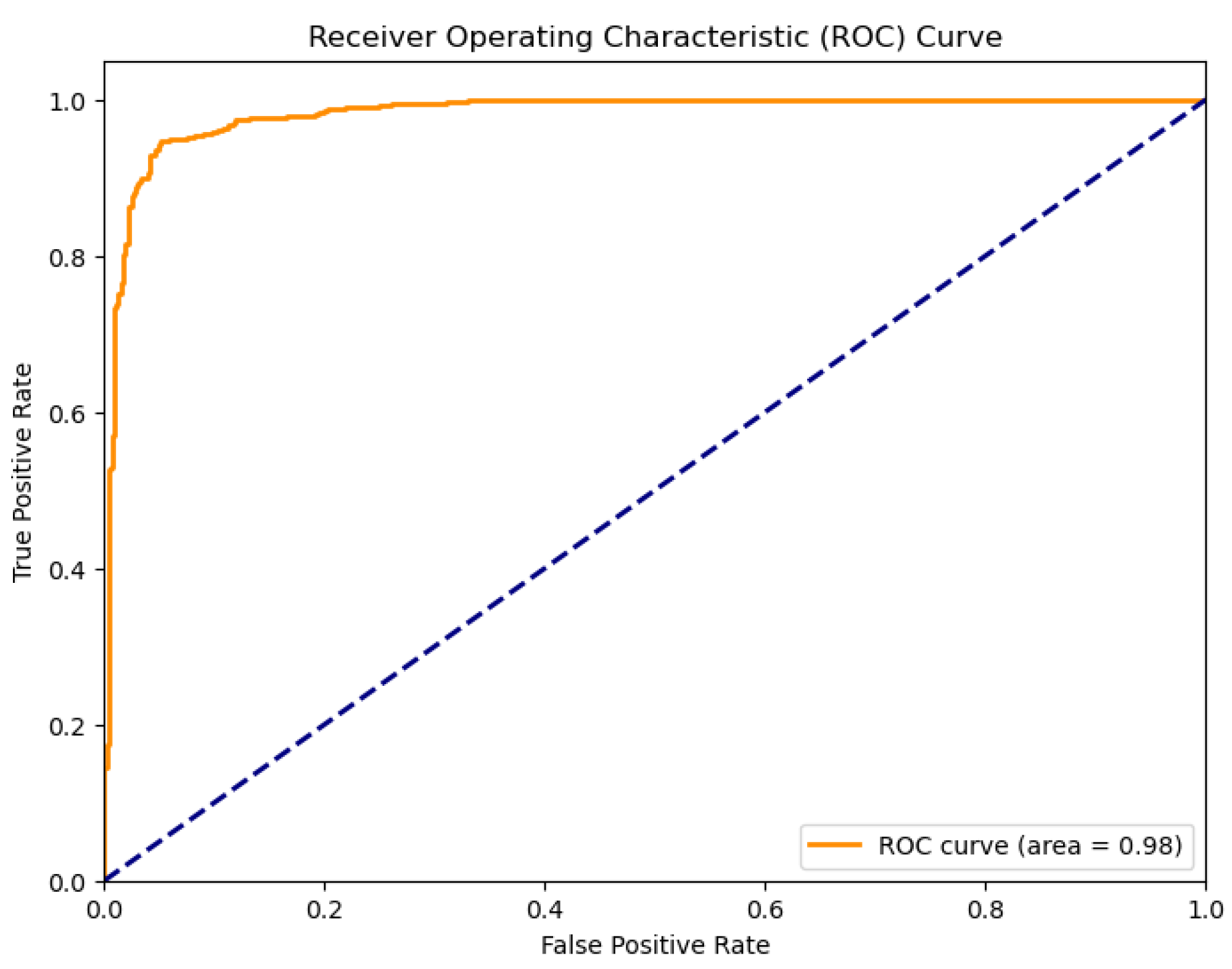

Table 3 presents the detailed classification report, and

Figure 3 shows the ROC curve for the model.

The performance of the FlameViT model was thoroughly evaluated through its training and validation phases. The training process was monitored using accuracy and loss metrics, which provide insights into how well the model is learning and generalizing to unseen data.

Figure 1 shows the training and validation accuracy over 20 epochs. The accuracy metrics indicate that the model quickly learns to differentiate between wildfire and no wildfire images. The training accuracy consistently increases, while the validation accuracy also shows a steady improvement, peaking at around 95\%. This high validation accuracy reflects the model’s ability to generalize well to new data, an essential characteristic for effective wildfire detection.

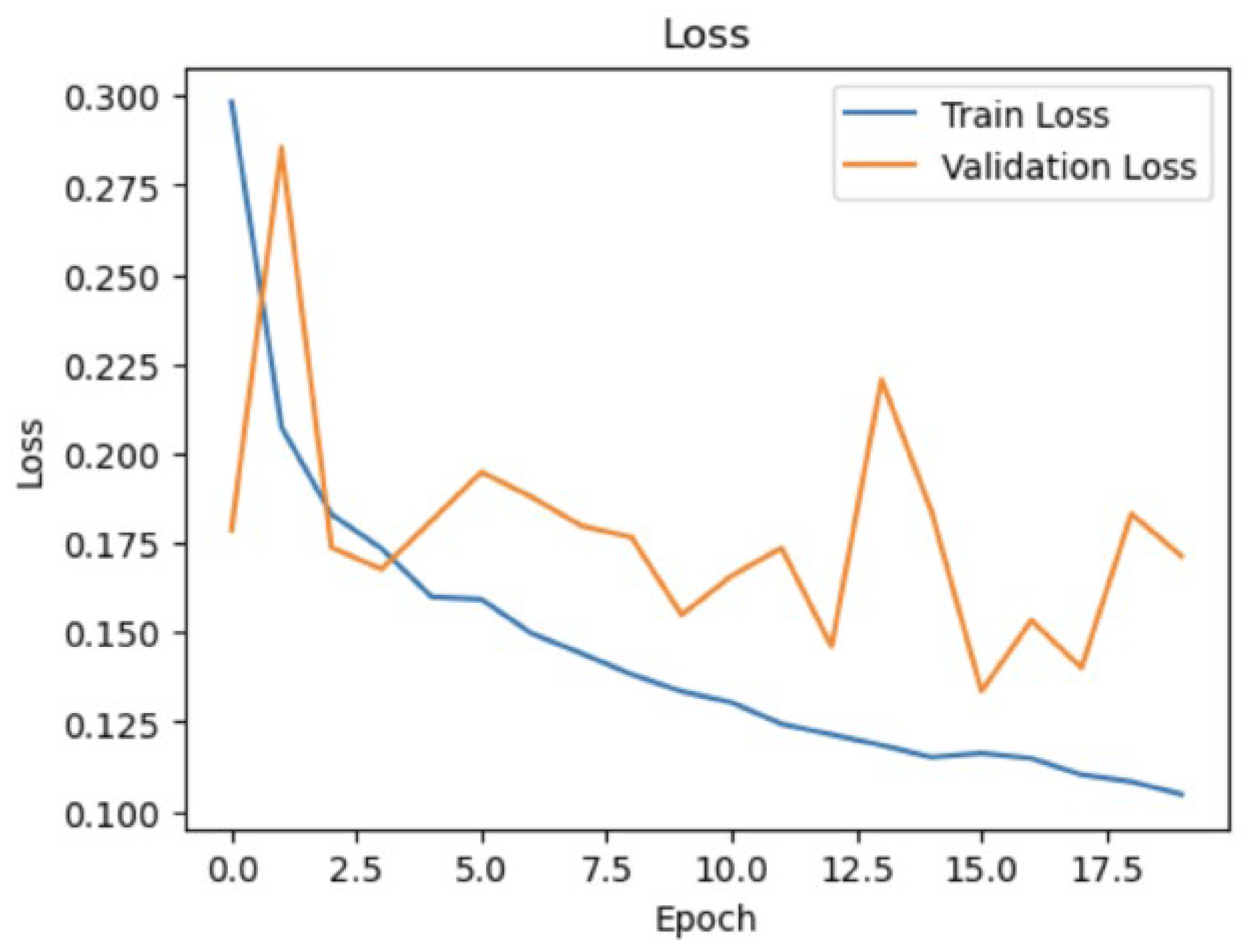

Similarly,

Figure 2 presents the training and validation loss over the same number of epochs. The loss values for both training and validation steadily decrease, which is a positive indication that the model is optimizing correctly. The early stopping mechanism, employed during training, ensures that the model does not overfit by halting the training process when the validation loss ceases to improve for several epochs. This technique is crucial for maintaining the model’s ability to perform well on unseen data, thereby enhancing its reliability and robustness.

The consistent trends observed in both the accuracy and loss graphs underscore the effectiveness of the FlameViT architecture and the chosen hyperparameters. The model not only achieves high performance during training but also maintains this performance during validation, which is indicative of its potential for real-world applications in wildfire detection.

The high validation accuracy and low validation loss suggest that FlameViT is well-suited for the task of wildfire smoke detection, offering a reliable tool for early wildfire detection and mitigation efforts.

Discussion

The FlameViT model’s predictions were evaluated on a test set. Four random sample predictions are illustrated in

Figure 3, showing the model’s prediction, actual label, and confidence score.

Figure 3.

ROC curve for FlameViT model.

Figure 3.

ROC curve for FlameViT model.

The model’s ability to accurately predict the presence of wildfire smoke with confidence demonstrates its effectiveness for this task. The high validation accuracy and consistent performance across various metrics indicate that FlameViT is a robust model for wildfire smoke detection in satellite imagery.

The FlameViT model significantly outperforms traditional CNN-based approaches, which achieved an accuracy of 86\%. This improvement can be attributed to the inherent advantages of Vision Transformers, which are particularly well-suited for the task of wildfire smoke detection.

Vision Transformers excel in capturing long-range dependencies and intricate spatial relationships in high-resolution images. This capability is crucial for detecting wildfire smoke, which can be dispersed across large areas in satellite imagery. The self-attention mechanism in transformers allows the model to focus on different parts of the image, enabling it to identify subtle patterns of smoke that might be missed by CNNs.

A key aspect of FlameViT is its ability to use smoke as a proxy for wildfire detection. Detecting smoke is often a more reliable and early indicator of wildfires compared to detecting the fire itself, especially in satellite imagery where the fire may be obscured by vegetation or other elements. The model leverages the distinct visual features of smoke, such as its texture, spread, and translucency, which are effectively captured by the patch-based processing and attention mechanisms of the transformer architecture.

During the learning process, FlameViT learns to differentiate between smoke and other visually similar phenomena, such as fog, clouds, or mist. This differentiation is achieved through extensive training on a diverse dataset that includes various environmental conditions. The multi-head self-attention mechanism allows the model to focus on the context and finer details within each patch of the image, learning the unique characteristics of smoke in the presence of other elements. For instance, smoke from wildfires typically has a more dynamic and irregular pattern compared to the more uniform and stationary appearance of fog. The positional encoding also helps the model maintain spatial relationships, further aiding in distinguishing smoke patterns from other artifacts.

The success of FlameViT in wildfire smoke detection has significant implications for fire detection and mitigation. Early detection of wildfire smoke allows for quicker response times, enabling firefighting teams to contain and extinguish fires before they spread uncontrollably. This can potentially save lives, protect property, and reduce economic losses.

Furthermore, the high accuracy and reliability of FlameViT make it a valuable tool for automated fire-fighting procedures. The model can be integrated into satellite monitoring systems, providing real-time alerts and detailed information about potential wildfire outbreaks. This can enhance the efficiency of firefighting efforts and improve overall disaster management strategies.

The relevance of these results extends beyond wildfire detection. The demonstrated effectiveness of Vision Transformers for high-resolution image analysis suggests that similar models could be applied to other remote sensing tasks, such as deforestation monitoring, agricultural assessment, and environmental protection.

Conclusion & Future Work

In this study, we developed and evaluated FlameViT, a Vision Transformer-based model for detecting wildfire smoke in satellite images. The model demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional CNN methods, achieving a validation accuracy of 95%. This represents a significant improvement over the benchmark CNN model, which had an accuracy of 86%.

The FlameViT model’s success can be attributed to its ability to capture long-range dependencies and intricate spatial relationships in high-resolution images, thanks to the self-attention mechanisms inherent in the transformer architecture. This capability is particularly important for detecting dispersed patterns of wildfire smoke, which are often challenging to identify with CNNs.

The implications of this research are profound. Early detection of wildfire smoke is crucial for timely and effective firefighting responses. By providing accurate and reliable predictions, FlameViT can help mitigate the devastating effects of wildfires, which have become increasingly severe due to climate change.

The integration of FlameViT into existing satellite monitoring systems could revolutionize wildfire detection and response strategies. Automated detection systems powered by FlameViT can provide real-time alerts, enabling rapid deployment of firefighting resources to contain fires before they spread. This can significantly reduce the loss of life, property damage, and economic impact caused by wildfires.

Beyond wildfire detection, the principles demonstrated in this research can be applied to a wide range of remote sensing tasks. The ability of Vision Transformers to handle high-resolution images with complex spatial dependencies makes them suitable for applications such as deforestation monitoring, crop health assessment, and environmental protection.

The success of FlameViT highlights the potential of Vision Transformers to advance the field of remote sensing and environmental monitoring. Future research can build on these findings by exploring the integration of additional data sources, such as weather data and topographical information, to further enhance the model’s predictive capabilities.

Future work in the field of wildfire detection can explore several promising directions to further enhance the capabilities and applicability of models like FlameViT. One area of focus could be the integration of multimodal data sources, such as weather conditions, topographical maps, and historical fire data, to provide a more comprehensive context for wildfire prediction. By combining visual information from satellite images with these additional data streams, models could achieve higher accuracy and reliability, particularly in complex and diverse environmental conditions. Moreover, advancements in transfer learning and domain adaptation could enable the fine-tuning of pre-trained models on specific regions or seasons, improving their performance in varying geographic and temporal contexts.

Another significant area for future research is the development of real-time, deployable systems for automated wildfire detection and monitoring. This involves creating lightweight, efficient models that can run on edge devices or integrate seamlessly with satellite communication systems. Such systems could provide continuous surveillance and instant alerts, dramatically reducing the response time to emerging wildfires. Additionally, the use of explainable AI techniques could help in understanding and interpreting model predictions, making it easier for human operators and decision-makers to trust and act upon the system’s outputs. Overall, the combination of enhanced data integration, real-time processing, and explainable AI promises to make wildfire detection systems not only more accurate but also more actionable and trustworthy in the fight against this growing environmental threat.

Furthermore, ongoing advancements in transformer architectures and training techniques can be leveraged to improve the performance and efficiency of models like FlameViT. As the field of machine learning continues to evolve, we can expect even more powerful tools for addressing the complex challenges posed by wildfires and other environmental threats.

In conclusion, FlameViT represents a significant advancement in the field of wildfire detection. By harnessing the power of Vision Transformers, we have developed a model that not only outperforms traditional methods but also offers a scalable and reliable solution for real-time wildfire monitoring. This research paves the way for more effective fire-fighting strategies and contributes to the broader goal of protecting our environment from the increasing threat of wildfires.

References

- David MJS Bowman, Jennifer K Balch, Paulo Artaxo,William J Bond, MarkACochrane, CarlaMD’Antonio, Ruth S DeFries, Fay H Johnston, Jon E Keeley, Meg A Krawchuk, et al. Fire in the earth system. Science 2009, 324, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilo Mora, Todd McKenzie, Ivan L Gaw, Justin M Dean, Heike von Hammerstein, Travis A Knudson,Ryan O Setter, Cameron Z Smith, KristopherMWebster, Jonathan A Patz, et al. Broad threat to humanity from cumulative climate hazards intensified by greenhouse gas emissions. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander Veraverbeke, Brendan M Rogers, Michael L Goulden, Randi R Jandt, Charles E Miller, E Brady Wiggins, and James T Randerson. Direct and indirect climate effects on spatial patterns of wildfires in boreal forest ecosystems. Science advances 2020, 6, eaay1121. [Google Scholar]

- Preeti Jain, Praveen Kumar Jain, and Preeti Chauhan. Review of forest fire detection techniques using wireless sensor network. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2020.

- X Xu, Q Guo, and Y Su. Gis-based wildfire risk mapping and modeling for mediterranean forests using logistic regression and multi-criteria decision analysis. Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 368, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- J D Radke and James Radke. Application of gis technology in forest fire prevention and management. International Journal of Geo-Information 2019, 8, 394. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Yuan, Hongjun Fang, Zhidong Deng, and Songyan Li. Fire detection in uav images using deep learning approach. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2015, 20, 2893–2904. [Google Scholar]

- Hongyu Zhao, Zhixin Wang, Bing Xu, Qun Liu, and Yong Zhang. Uav-based remote sensing for forest fire monitoring and assessment. Journal of Remote Sensing 2018, 22, 578–589. [Google Scholar]

- Carl Hartung, Richard Han, and Carl Seielstad. Fire risk assessment using wireless sensor networks. 2006 Fourth Annual IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and CommunicationsWorkshops (PerCom Workshops), pages 13–17, 2006.

- Xinjian Mao, Qingxin Xie, and Shilin Tang. Wireless sensor networks for fire risk prediction and forest fire detection. Sensors 2019, 19, 1441. [Google Scholar]

- Zhiyuan Liu, Jian Yang, Youbao Chang, and Licheng Jiao. Assessment of forest fire risk based on fuzzy ahpand fuzzy comprehensive evaluation. Ecological Modelling 2015, 297, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wenming Xi and Jianqing, Li. Integrating multi-source data to improve forest fire detection based on random forests. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 297. [Google Scholar]

- Prashant Kumar Srivastava, Dawei Han, Miguel Angel Rico-Ramirez, Michael Bray, Tanvir Islam, and Qiang Dai. Deep learning for precipitation prediction: Towards better accuracy. Meteorological Applications 2020, 27, e1874. [Google Scholar]

- Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey E Hinton. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556.

- Kaiming He, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 770–778, 2016.

- Igor Farasin, Mario Anedda, Andrea Fanni, and Luigi Martis. Deep learning techniques for wildland fires analysis through aerial images. 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), pages 1068–1071, 2017.

- Sujith Raj, K Suriyalakshmi, and K Srinivasan. Detection of wildfires using recurrent neural networks. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2020, 49, 101745. [Google Scholar]

- Jian Zhang, Zhiwei Zhang, Junwei Ma, and Lei Wang. Enhancing spatial attention using dual attention mechanism for wildfire detection in satellite images. Remote Sensing Letters 2019, 10, 903–912. [Google Scholar]

- Jieneng Chen, Yongyi Lu, Qihang Yu, Xiangde Luo, Ehsan Adeli, YanWang, Le Lu, Alan L Yuille, and Yuyin Zhou. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306.

- Hugo Touvron, Matthieu Cord, Alexandre Sablayrolles, Gabriel Synnaeve, and Herv’e J’egou. Training dataefficient image transformers and distillation through attention. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2012.12877. [Google Scholar]

- Alexey Dosovitskiy, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, Matthias Minderer, Georg Heigold, Sylvain Gelly, et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929.

- Christian Szegedy, Wei Liu, Yangqing Jia, Pierre Sermanet, Scott Reed, Dragomir Anguelov, and Andrew Rabinovich. Going deeper with convolutions. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 1–9, 2015.

- Gao Huang, Zhuang Liu, Laurens Van Der Maaten, and Kilian Q Weinberger. Densely connected convolutional networks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 4700–4708, 2017.

- Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, AidanNGomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).