Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

19 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Related Work

1.3. Contribution of This Work

2. Materials and Methods

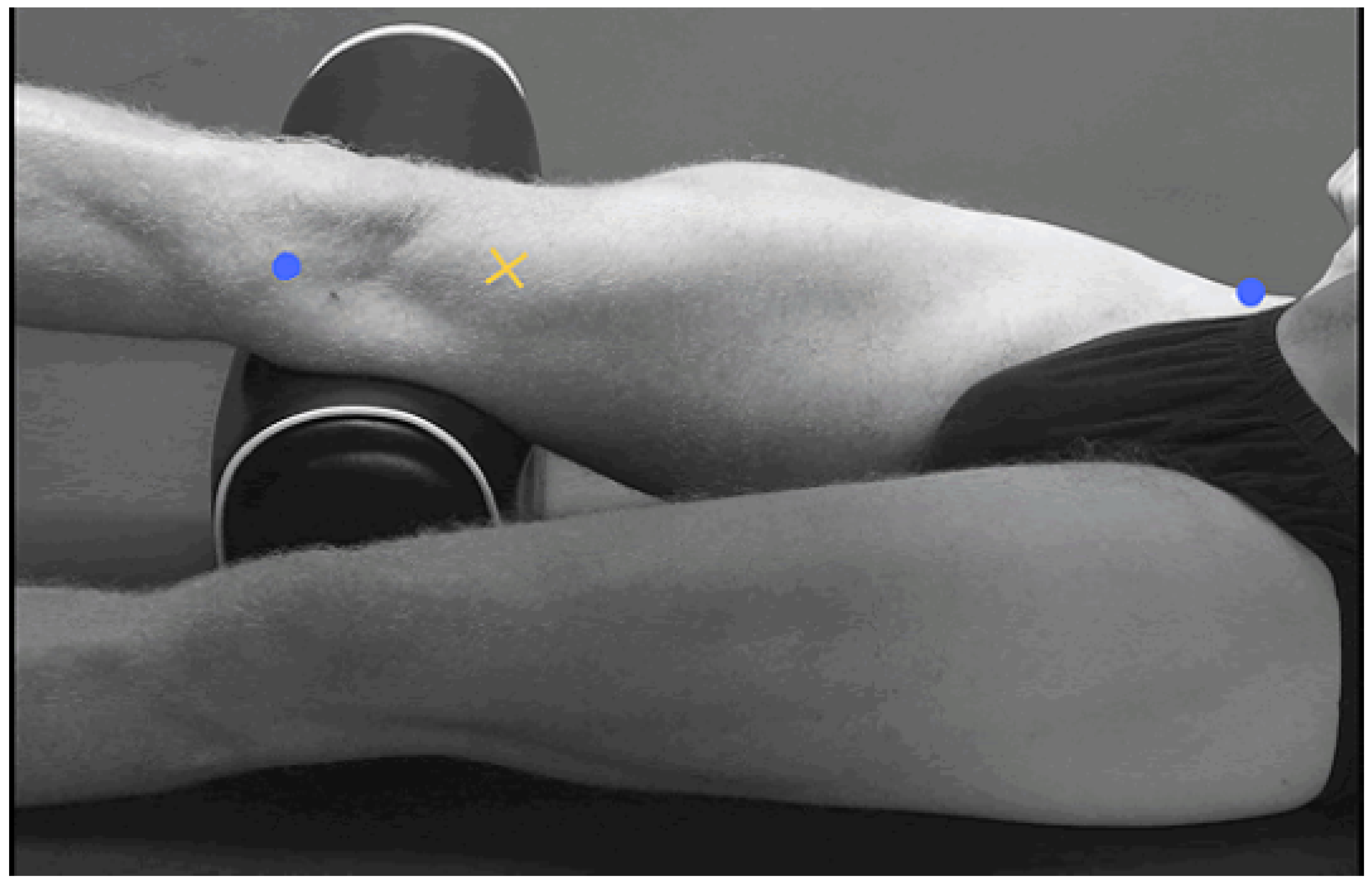

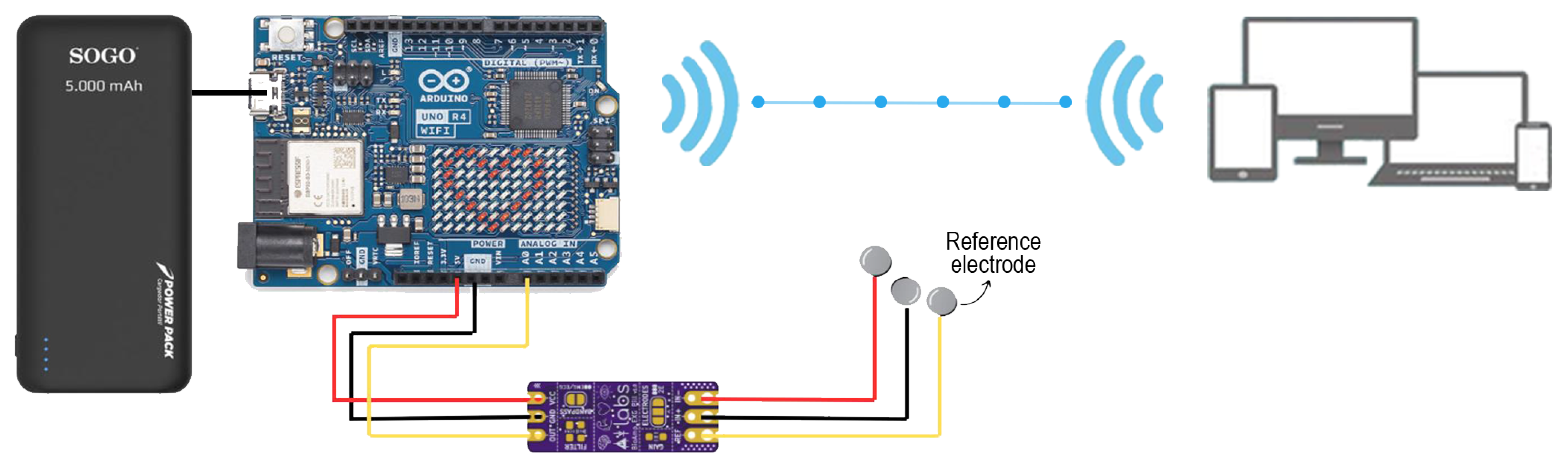

2.1. System Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Signal Processing and Feature Extraction

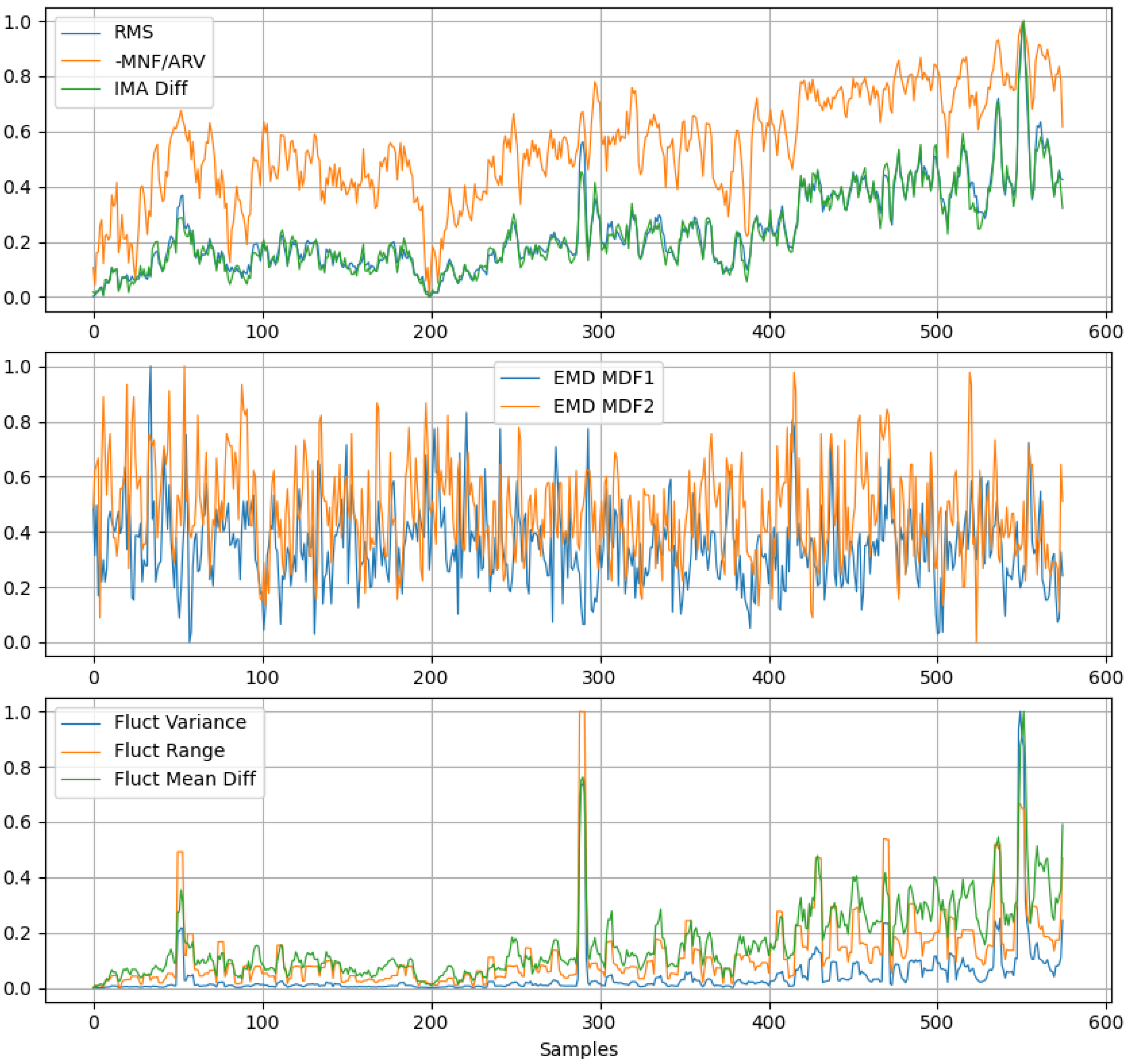

2.3.1. Feature Evaluation

- RMS

- MNF/ARV ratio

- Instantaneous Mean Amplitude Difference (IMA Difference)

- EMD-based Median Frequencies (MDF1 and MDF2)

- Fluctuation Variance

- Fluctuation Range Values

- Fluctuation Mean Difference.

2.3.2. Window Size Analysis

3. Metric Standardization and Fatigue Modeling

3.1. Baseline Establishment

- Metric( Active / RMS(Rest))

- Metric(Active) / Metric( RMS(Rest))

- Metric( Active / RMS(1st Active))

- Metric(Active) / Metric(RMS(1st Active))

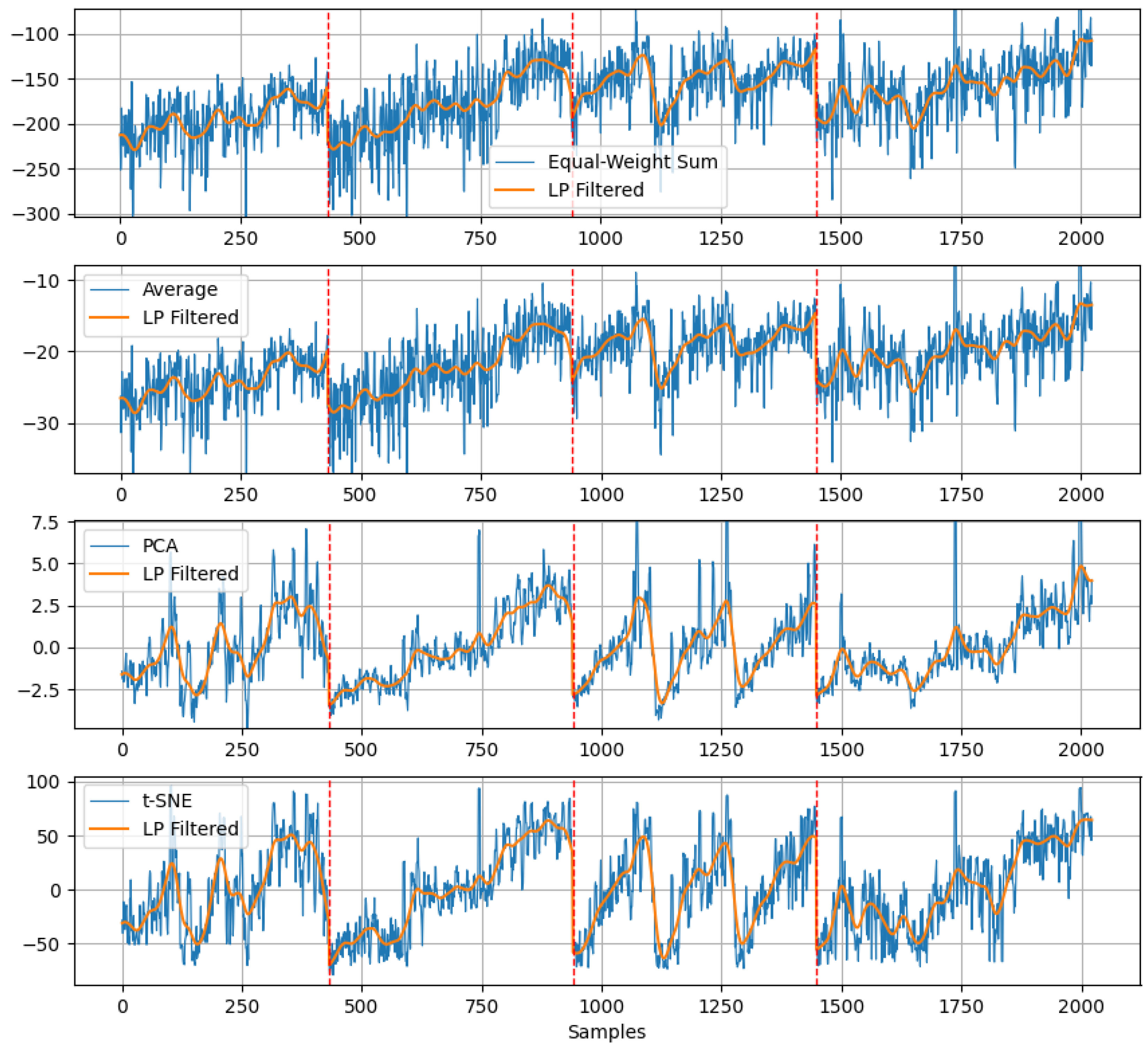

3.2. Fatigue Estimation Approaches

- Equal-weighted Sum

- Average

- PCA

- t-SNA

3.3. Machine Learning Model Training & Evaluation

- Simple Linear Regression

- Support Vector Regression

- Random Forest Regression

- Gradient Boosting Machines Regression

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Neural Networks Regression

- Convolutional Neural Networks Regression

- k-Nearest Neighbors Regression

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Baseline and Metric Analysis

4.2. Fatigue Estimation Performance

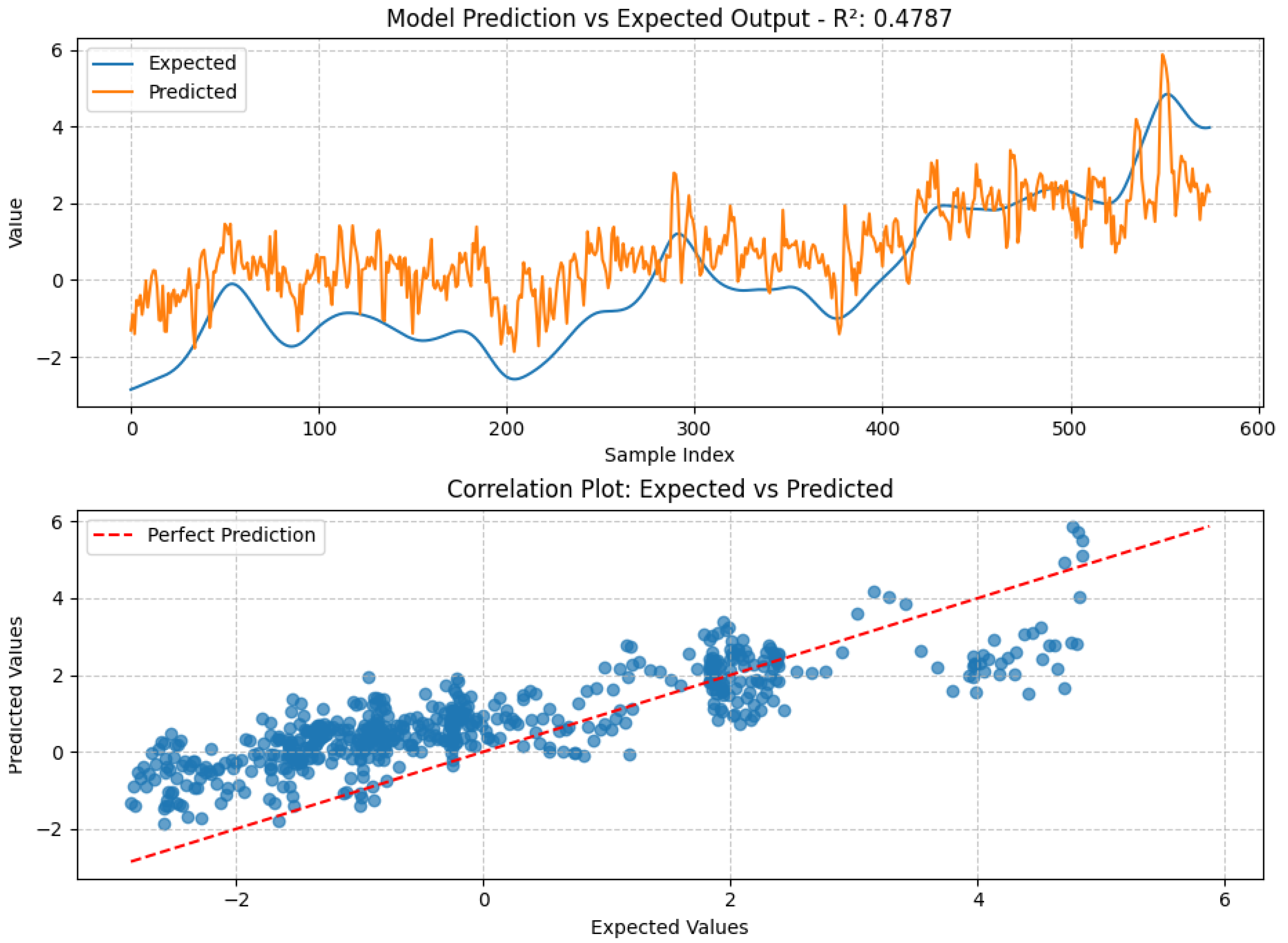

4.3. Machine Learning Model Performance

4.4. Comparative Discussion

5. Conclusion and Future Work

5.1. Key Findings

5.2. Contributions of This Work

5.3. Limitations

5.4. Future Work

References

- Al-Ayyad, M.; Owida, H.A.; De Fazio, R.; Al-Naami, B.; Visconti, P. Electromyography Monitoring Systems in Rehabilitation: A Review of Clinical Applications, Wearable Devices and Signal Acquisition Methodologies. Electronics 2023, 12, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Lin, C.B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Huang, T.S.; Hsu, C.Y. An EMG Patch for the Real-Time Monitoring of Muscle-Fatigue Conditions During Exercise. Sensors 2019, 19, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wencong, X. A Surface EMG System: Local Muscle Fatigue Detection. Master’s thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.D.; Ruan, S.J.; Lee, Y.H. An Ultra-Low Power Surface EMG Sensor for Wearable Biometric and Medical Applications. Biosensors 2021, 11, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Liu, G.; Sun, Y.; Lin, K.; Zhou, Z.; Cai, J. Application of Surface Electromyography in Exercise Fatigue: A Review. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 893275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousif, H.; Zakaria, A.; Abdul Rahim, N.; Salleh, A.; Sabry, M.; Alfarhan, K.; Kamarudin, L.; Syed Zakaria, S.M.M.; Hasan, A.; K Hussain, M. Assessment of Muscles Fatigue Based on Surface EMG Signals Using Machine Learning and Statistical Approaches: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 705, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qassim, H.; Hasan, W.; Ramli, H.; Harith, H.; Mat, L.; Ismail, L. Proposed Fatigue Index for the Objective Detection of Muscle Fatigue Using Surface Electromyography and a Double-Step Binary Classifier. Sensors 2022, 22, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzu, A.; Neacşu, A.; Georgian, N. Automatic Muscle Fatigue and Movement Recognition Based on sEMG Signals; International Symposium ELMAR: Zadar, Croatia, 2024; pp. 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinugasa, R.; Kubo, S. Development of Consumer-Friendly Surface Electromyography System for Muscle Fatigue Detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 6394–6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, A.; Vizza, P.; Calabrese, B.; Ielpo, N. Biopotential Signal Monitoring Systems in Rehabilitation: A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, J.B.; Yoshioka, M.; Ozawa, J. Estimation of muscle fatigue by ratio of mean frequency to average rectified value from surface electromyography. In Proceedings of the 2016 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2016; pp. 5303–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Chang, K.M.; Cheng, D.C. The Progression of Muscle Fatigue During Exercise Estimation With the Aid of High-Frequency Component Parameters Derived From Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2014, 18, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C. Analyzing the influencing factors of sports fatigue based on algorithm. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia Zhang, Z.G. High accuracy recognition of muscle fatigue based on sEMG multifractal and LSTM. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2024, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metric Category | Window Size 200 samples (0.250 s) | Window Size 400 samples (0.500 s) | Window Size 800 samples (1.000 s) | Window Size 1600 samples (2.000 s) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step Size (samples) | Step Size (samples) | Step Size (samples) | Step Size (samples) | ||||||||||||||

| 150 | 100 | 50 | 25 | 300 | 200 | 100 | 50 | 600 | 400 | 200 | 100 | 1200 | 800 | 400 | 200 | ||

| Variance | MNF/ARV | 8.00 | 8.05 | 8.08 | 8.08 | 7.23 | 7.15 | 7.15 | 7.15 | 6.67 | 6.66 | 6.67 | 6.68 | 6.45 | 6.39 | 6.36 | 6.38 |

| IMA | 28.77 | 28.99 | 29.01 | 28.99 | 13.61 | 13.61 | 13.62 | 13.62 | 6.50 | 6.54 | 6.54 | 6.54 | 3.17 | 3.16 | 3.17 | 3.17 | |

| EMD | 767.65 | 755.85 | 755.00 | 758.81 | 506.94 | 520.80 | 519.62 | 517.02 | 391.65 | 388.95 | 384.56 | 386.74 | 315.48 | 298.99 | 298.54 | 297.91 | |

| Fluct () | 4.48 | 5.21 | 4.88 | 4.70 | 4.28 | 4.19 | 4.36 | 4.10 | 3.35 | 3.44 | 3.46 | 3.56 | 2.81 | 2.98 | 2.97 | 2.95 | |

| Max-Min | MNF/ARV | 25.13 | 25.27 | 33.10 | 36.39 | 19.01 | 19.04 | 19.09 | 19.41 | 16.35 | 16.56 | 18.65 | 18.65 | 16.06 | 16.44 | 16.45 | 16.57 |

| IMA | 30.57 | 30.57 | 34.86 | 34.86 | 19.56 | 18.81 | 19.56 | 19.61 | 12.28 | 12.29 | 12.30 | 12.33 | 7.94 | 7.79 | 7.94 | 7.96 | |

| EMD | 260.00 | 280.00 | 280.00 | 280.00 | 244.00 | 246.00 | 246.00 | 246.00 | 175.00 | 167.00 | 179.00 | 187.00 | 201.56 | 182.81 | 201.56 | 201.56 | |

| Fluct () | 62.57 | 70.08 | 70.08 | 71.25 | 47.05 | 37.76 | 47.51 | 47.51 | 22.26 | 23.20 | 23.31 | 28.36 | 19.14 | 19.93 | 19.93 | 19.93 | |

| Max Differential | MNF/ARV | 10.67 | 13.82 | 12.79 | 11.10 | 7.70 | 7.34 | 5.89 | 4.73 | 9.48 | 8.94 | 6.85 | 4.11 | 8.64 | 9.02 | 6.62 | 5.60 |

| IMA | 17.02 | 14.97 | 13.01 | 11.97 | 8.18 | 7.30 | 6.48 | 6.22 | 5.19 | 4.56 | 2.97 | 2.25 | 2.96 | 2.39 | 1.91 | 1.24 | |

| EMD | 216.00 | 196.00 | 236.00 | 240.00 | 202.00 | 204.00 | 204.00 | 188.00 | 118.00 | 129.00 | 118.00 | 150.00 | 134.38 | 139.06 | 101.56 | 113.28 | |

| Fluct () | 60.85 | 61.71 | 60.77 | 55.37 | 43.09 | 33.80 | 39.23 | 39.30 | 19.51 | 19.26 | 17.73 | 22.35 | 15.04 | 11.16 | 11.01 | 9.60 | |

| Computation time (s) | 0.057 | 0.057 | 0.036 | 0.035 | 0.053 | 0.061 | 0.051 | 0.094 | 0.147 | 0.153 | 0.132 | 0.153 | 0.306 | 0.282 | 0.16209 | 0.159 | |

| Participant | MNF/ARV Ratio | IMA Difference | EMD | Fluctuation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject 1 | 20 - 70 | 0.1 - 0.35 | 30 - 120 | 0 - 17 |

| Subject 2 | 30 - 80 | 0.1 - 0.3 | 30 - 125 | 0 - 12 |

| Subject 3 | 30 - 80 | 0.12 - 0.325 | 30 - 110 | 0 - 13 |

| Subject 4 | 40 - 100 | 0.1 - 0.22 | 35 - 120 | 0 - 7 |

| Subject 5 | 30 - 70 | 0.125 - 0.3 | 35 - 110 | 0 - 10 |

| Subject 6 | 50 - 95 | 0.1 - 0.19 | 35 - 140 | 0 - 7 |

| Subject 7 | 35 - 90 | 0.1 - 0.25 | 35 - 140 | 0 - 6 |

| Subject 8 | 50 - 110 | 0.08 - 0.16 | 25 - 100 | 0 - 5 |

| Subject 9 | 35 - 85 | 0.1 - 0.22 | 35 - 125 | 0 - 6 |

| Subject 10 | 30 - 80 | 0.1 - 0.275 | 30 - 95 | 0 - 12 |

| Subject 11 | 40 - 90 | 0.1 - 0.27 | 30 - 115 | 0 - 9 |

| Model | R² | MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.5209 | 1.4059 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.5198 | 1.4090 |

| LSTM | 0.4876 | 1.5037 |

| Simple Linear | 0.4718 | 1.5499 |

| SVR | 0.4704 | 1.5542 |

| KNN | 0.4598 | 1.5853 |

| CNN | 0.4303 | 1.6717 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).