1. Introduction

Due to the good function and practicability of special-shaped column structures, the mechanical properties and design methods of special-shaped column structures have been extensively investigated over the past few years, and many scholars have conducted in-depth research on the seismic performance of special-shaped column structures(Shetty et al. 2019; Patel 2020; Wu 2013; Zheng et al. 2024; Salah et al. 2022; Liu et al. 2021) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, for special-shaped columns with cross-shaped, T-shaped and L-shaped asymmetric sections, the column will bend while twisting when the horizontal load acts on the centroid axis of the asymmetric axis. When the structure is subjected to eccentric torsion, the special-shaped columns bear the torque distributed by the floor, as well as the torque generated by their own torsion. Experimental studies have demonstrated that the torsional phenomenon of special-shaped column structures is more pronounced under multidimensional earthquake conditions, with even axially symmetric special-shaped column structures experiencing torque (Zhang and Far 2021; Li et al. 2023; Sunagar et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2021; Ismail 2020) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. This underscores that the torsional challenges of special-shaped column structures cannot be overlooked under specific dynamic conditions, such as earthquakes, where ground rotational components significantly amplify structural torsion. For the spatial frame structure with specially shaped columns, the factors affecting its seismic response are the same as those of general frame structures, including seismic components and intensity, structural vibration characteristics, eccentricity, strong column-weak beam failure mechanism, etc. Due to the limitations of the architectural form, uncertainties in construction, and the influence of irregular cross-sections, the spatial frame structure with specially shaped columns inevitably exhibits eccentric characteristics. Under the multidimensional seismic action including ground rotation components and planar vibration components, the structure will obviously experience multidimensional seismic responses with coupled translational and torsional motions (Kuang and Liu 2022; Hao 1997; Lai and He 2022; Wen et al. 2024) [

12,

13,

14,

15]. As structural engineers, we are obviously more concerned about the performance of this new structural system under such complex stress conditions, the response patterns at different stages, especially the torsional response patterns, and how to conduct seismic design.

Consequently, it is imperative to investigate the torsional response behavior of special-shaped column structures influenced by both structural eccentricity and ground rotational components, providing theoretical guidance for the anti-torsion design of columns and structures. The torsional behavior of structures during seismic activity is primarily attributed to their inherent eccentricity and ground rotational components. The current approach to anti-torsion design accounts for rotational components stemming from seismic activity, construction, support disturbances, and accidental eccentricities during structure use, incorporating additional eccentricities due to the absence of precise measurements of ground rotational components. Torsional behaviors induced by structural eccentricity are determined through elastic analysis (Mao et al. 2022; Alam et al. 2023) [

16,

17]. Nevertheless, this analytical method neglects the coupled effect of ground rotational and translational components and the dynamic impacts on the structure, making it inadequate for predicting torsional outcomes and response patterns of structures under seismic action in practical scenarios.

Therefore, this study emphasizes and considers ground rotational components, applying vibration theory to develop an earthquake response analysis model amenable to analytical calculations. It establishes a methodology for analyzing combined translational and torsional vibrations and investigates the response patterns of structures under such combined vibrations. By simulating seismic response patterns on steel-concrete composite special-shaped column structures, theoretical analysis results are contrasted to validate the response patterns and dynamic amplification effects of combined lateral-torsional vibrations. Ultimately, this research provides theoretical references for analyzing combined lateral-torsional vibrations in special-shaped column structures.

2. Seismic Response Analysis Model Considering Ground Rotational Components

2.1. Dynamics Model Considering Ground Rotational Components

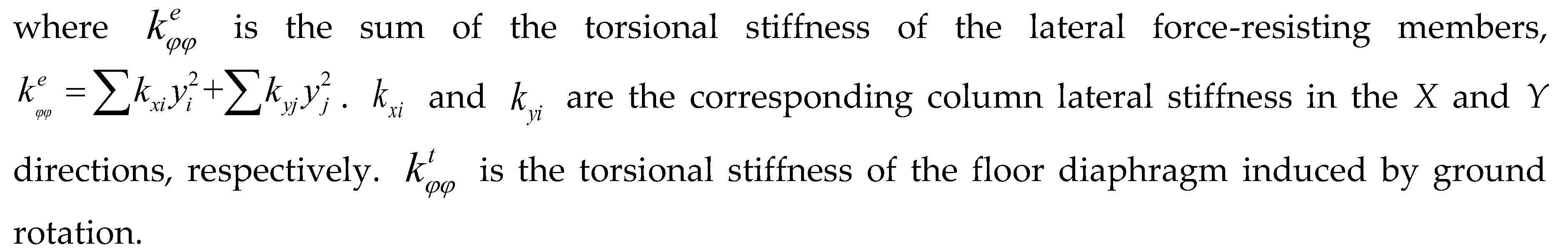

When establishing a dynamic model for a single-story eccentric structure that considers ground rotational components (

Figure 1), the following assumptions are made: (1) The ground rotational components are presumed to encompass horizontal components in both the

X and

Y directions, as well as within the

XY plane. (2) It is assumed that the horizontal ground rotational components solely induce pure torsion in the structure, whereas the horizontal displacement component triggers both structural displacement and eccentric torsion. The torsional response of the structure is bifurcated into eccentric torsion and pure torsion, both of which are induced by ground rotation. The displacement response of the structure is a composite of horizontal displacements triggered by ground vibration, along with both eccentric torsion and ground rotation. Furthermore, the seismic response pattern of the structure exhibits both translational and torsional characteristics. (3) For each floor, the torsional rotation angle remains consistent for both the inter-story torsional angle and the floor rotation angle, which are caused by eccentric torsion and pure torsion, respectively, as induced by ground rotation. (4) The rotation of each floor is constrained by equivalent springs and dampers. The seismic torsional moment revolves around the floor’s centroid, and the resultant force stemming from the restoring and damping forces caused by seismic torsion acts through the floor’s centroid. The floor’s mass moment of inertia is simplified and is considered to act at the floor’s center of mass.

According to the aforementioned assumptions, the horizontal twist angle of the building floor is determined as follows:

where

φe represents the horizontal torsional angle induced by structural eccentricity, and

φt denotes the pure torsional angle generated by the horizontal ground rotational components of the structure.

The total torsional angle of the building floor is given by:

where

φ’ represents the relative torsional angle of the building floor, and

φg denotes the ground torsional component.

The total displacement of the building floor is expressed as follows:

where

ux and

uy represent the relative horizontal displacements of the building floor in the

X and

Y directions with respect to the ground, and

ugx and

ugy denote the horizontal displacement components of the ground in the

X and

Y directions, respectively.

The lateral force-resisting displacement components in the

X and

Y directions are expressed as follows:

where

yiφ and

xiφ represent the displacements caused by the building floor rotation in the

X and

Y directions, respectively.

Considering the effects of ground rotation on a single-story structure, as illustrated in

Figure 1, the dynamic model can be transformed into a motion equation for the structure under horizontal earthquake action, expressed as follows:

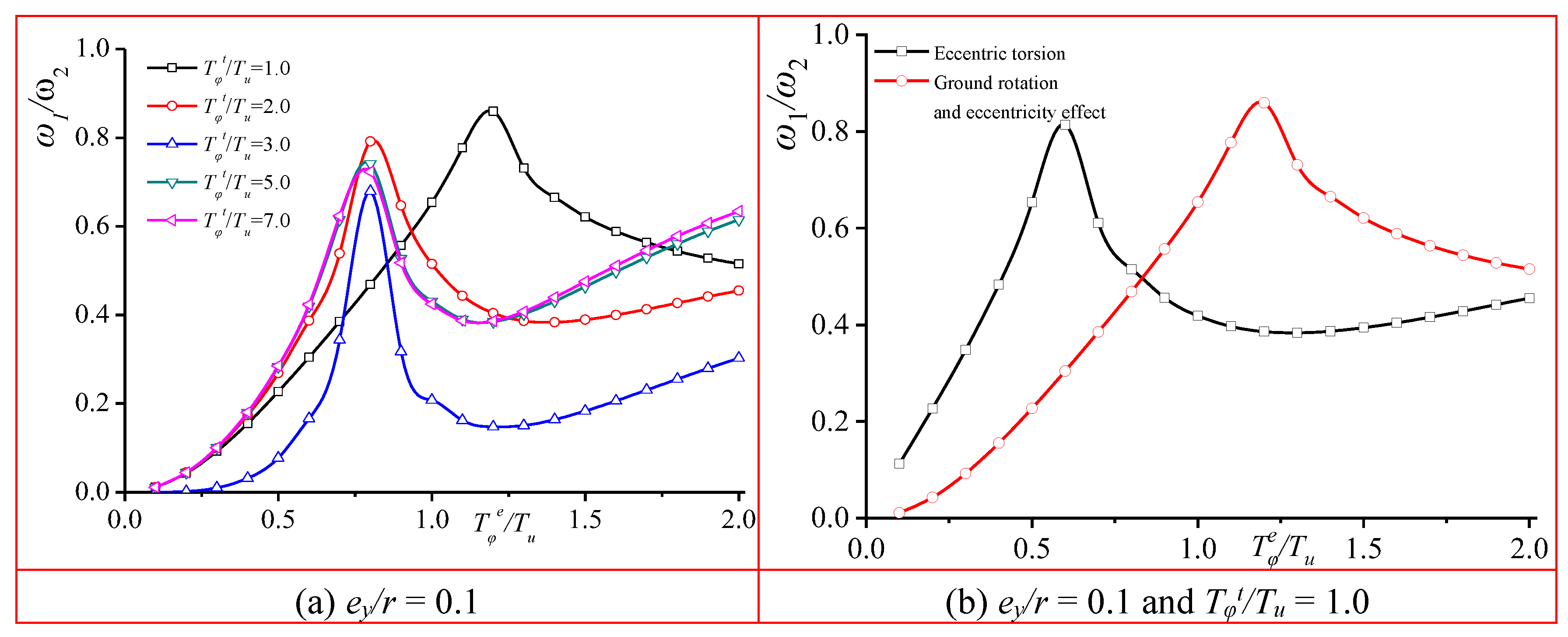

where

m represents the total mass concentrated on the building floor;

J denotes the building floor's moment of inertia around the

Z-axis;

and

are the translational stiffnesses of the building floor in the

X and

Y directions, respectively;

represents the torsional stiffness of the building floor;

denotes the total torsional stiffness of the anti-lateral force members; and

represents the torsional stiffness of the building floor caused by ground rotation.

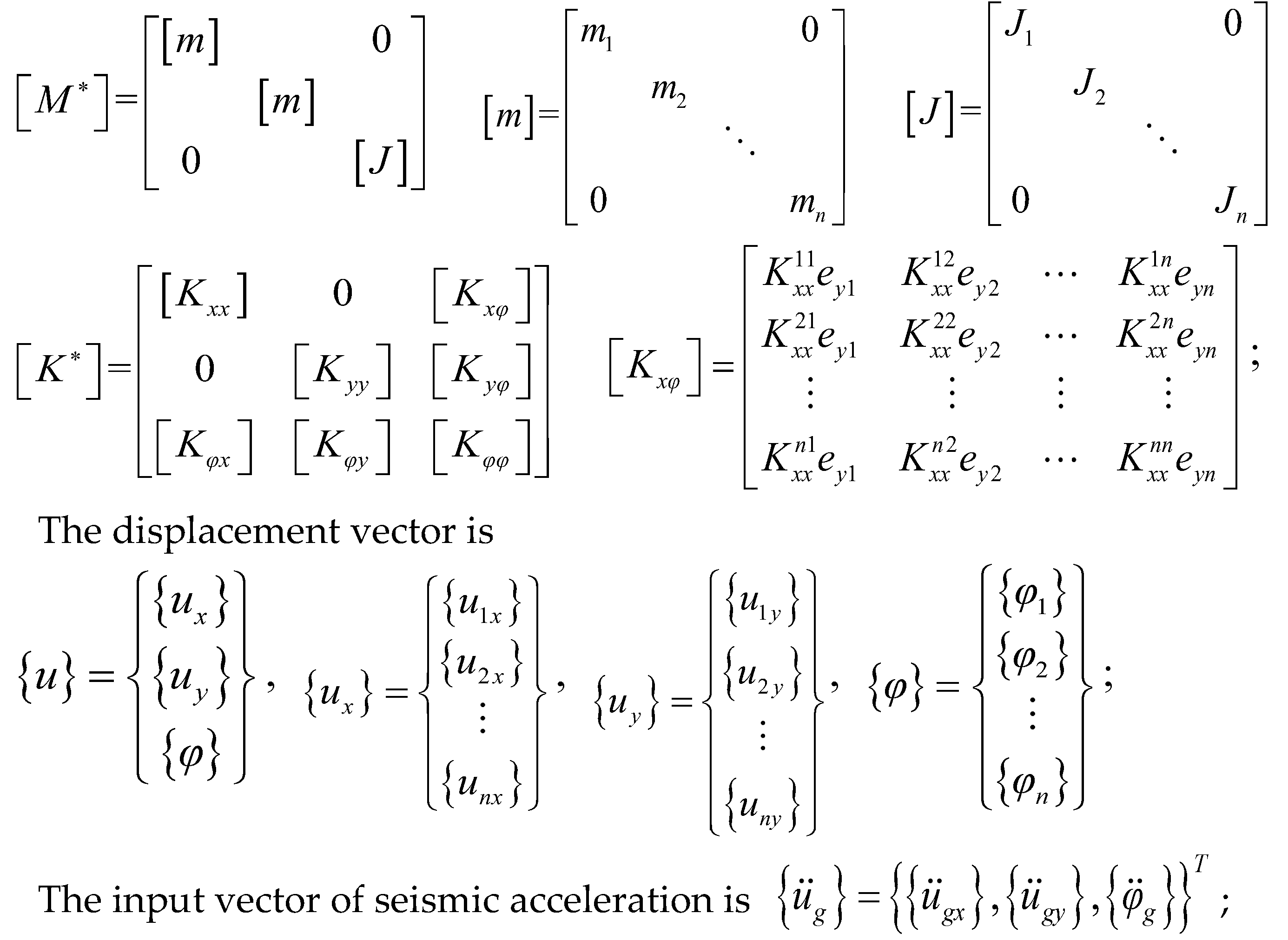

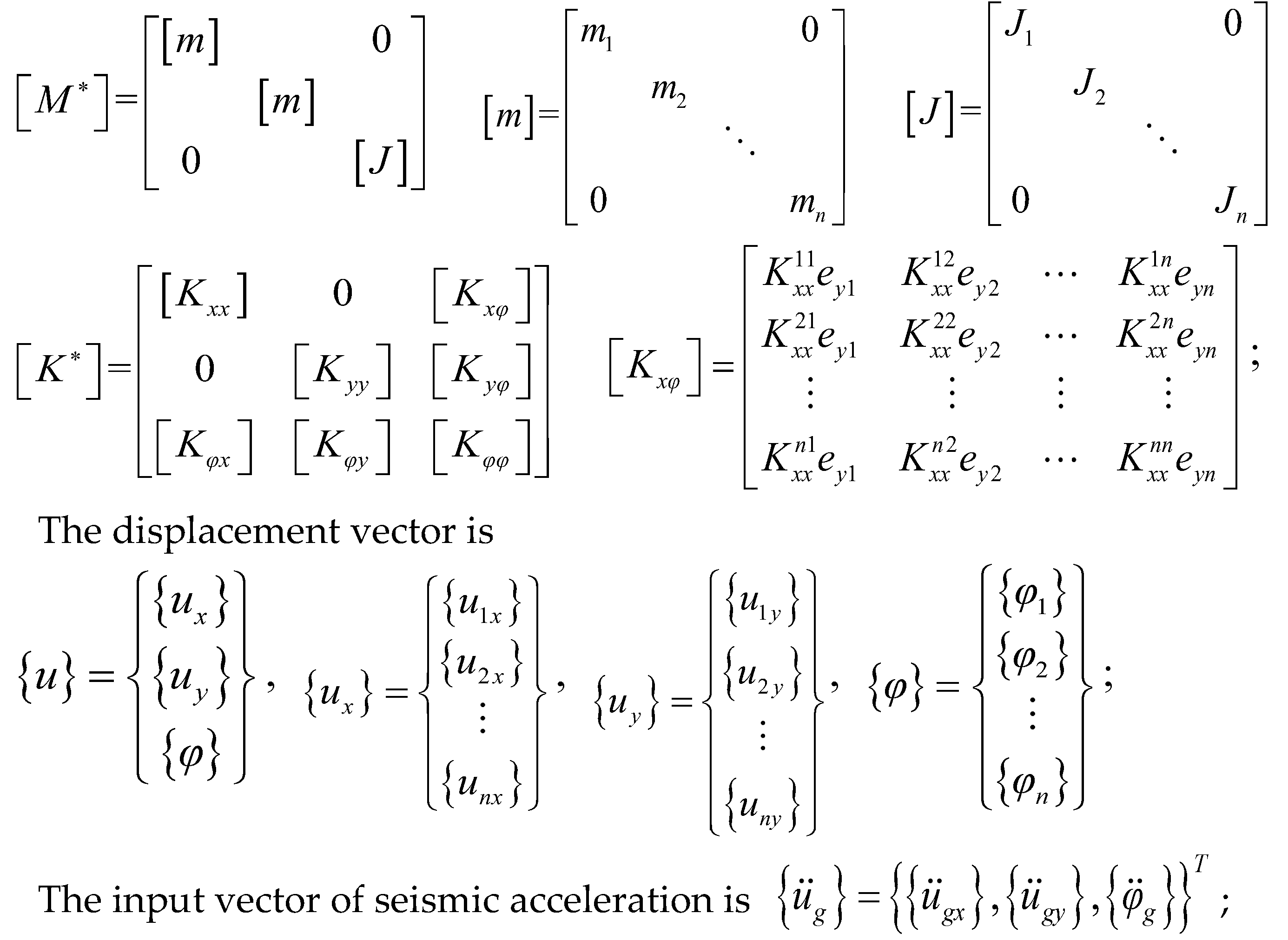

The dynamic model for multi-story eccentric structures, when considering ground rotation, is assumed to be the same as that for single-story structures. The motion equation for multi-story eccentric structures, taking into account ground rotation, can be derived by referencing the motion equation for multi-story eccentric structures under horizontal earthquake action and the motion equation for single-story eccentric structures considering ground rotation. This equation is expressed as follows:

where the characteristic matrix is

The calculation of characteristic parameters within the feature matrix remains the same for single-story structures subjected to multidimensional seismic conditions.

2.2. Determination of Floor Torsional Stiffness

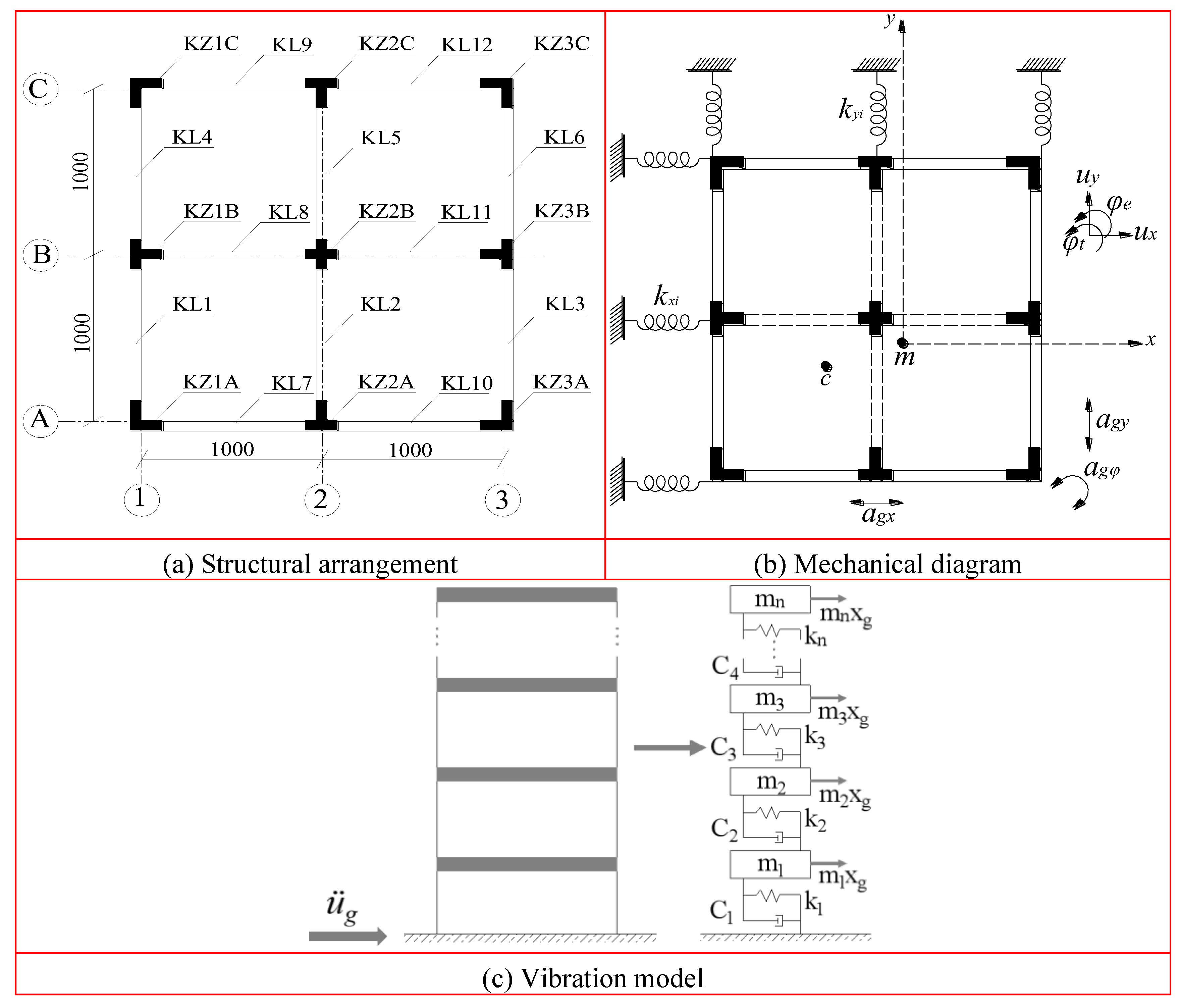

The floor torsion of the model presented in

Figure 2 illustrates torsion induced by the eccentricity of horizontal seismic forces, as well as pure floor torsion resulting from ground rotation. The floor torsion can be calculated as follows:

where the total torsion of the rth floor, denoted as

, is equal to the floor moment caused by the eccentric horizontal seismic force,

Vr, plus the pure torsion caused by inertial effects, represented by

;

φt is the inter-story torsional rotation angle,

φe is the eccentric torsional rotation angle, and

φ is the total inter-story rotation angle, with positive values indicating counterclockwise rotation. Therefore, the total torsion equation for this floor is expressed as:

The shear force generated by the floor rotation can be expressed as:

By considering moments around the floor centroid, Equation (6) is expressed based on torque equilibrium,

, as follows:

where

G represents the concrete shear modulus,

denotes the elastic torsional stiffness of the component, and

It signifies the torsional moment of inertia of the component's cross-section.

According to Equations (5) and (6), the torsional stiffness of the floor can be expressed as follows:

Equation (7) comprehensively considers inter-story torsion caused by ground rotation and eccentricity, as well as the lateral stiffness of structural elements. Moreso, it reflects the influence of the lateral force-resisting elements’ arrangement and floor height.

3. Lateral–Torsional Vibration Mathematical Mode

3.1. Establishment of Lateral–Torsion Coupled Motion Equations

When considering only seismic action in the main vibration direction along the X-axis and eccentricity along the Y-axis, simplifying Equation (1) yields the plan-torsion coupled motion equation in the Y direction for a single-story eccentric structure, while also accounting for the influence of ground rotational components.(2)

By utilizing the orthogonality of vibration modes, the motion equations can be decoupled to obtain the participation coefficients of each vibration mode. Specifically, when a seismic force acts along the

X direction and the structure is eccentric in the

Y direction, the following applies:

The maximum degree of freedom displacement

i at mode

j can be obtained by applying the principle of superposition, which is expressed as follows:

3.2. Response Patterns of Lateral–Torsional Coupled Vibration

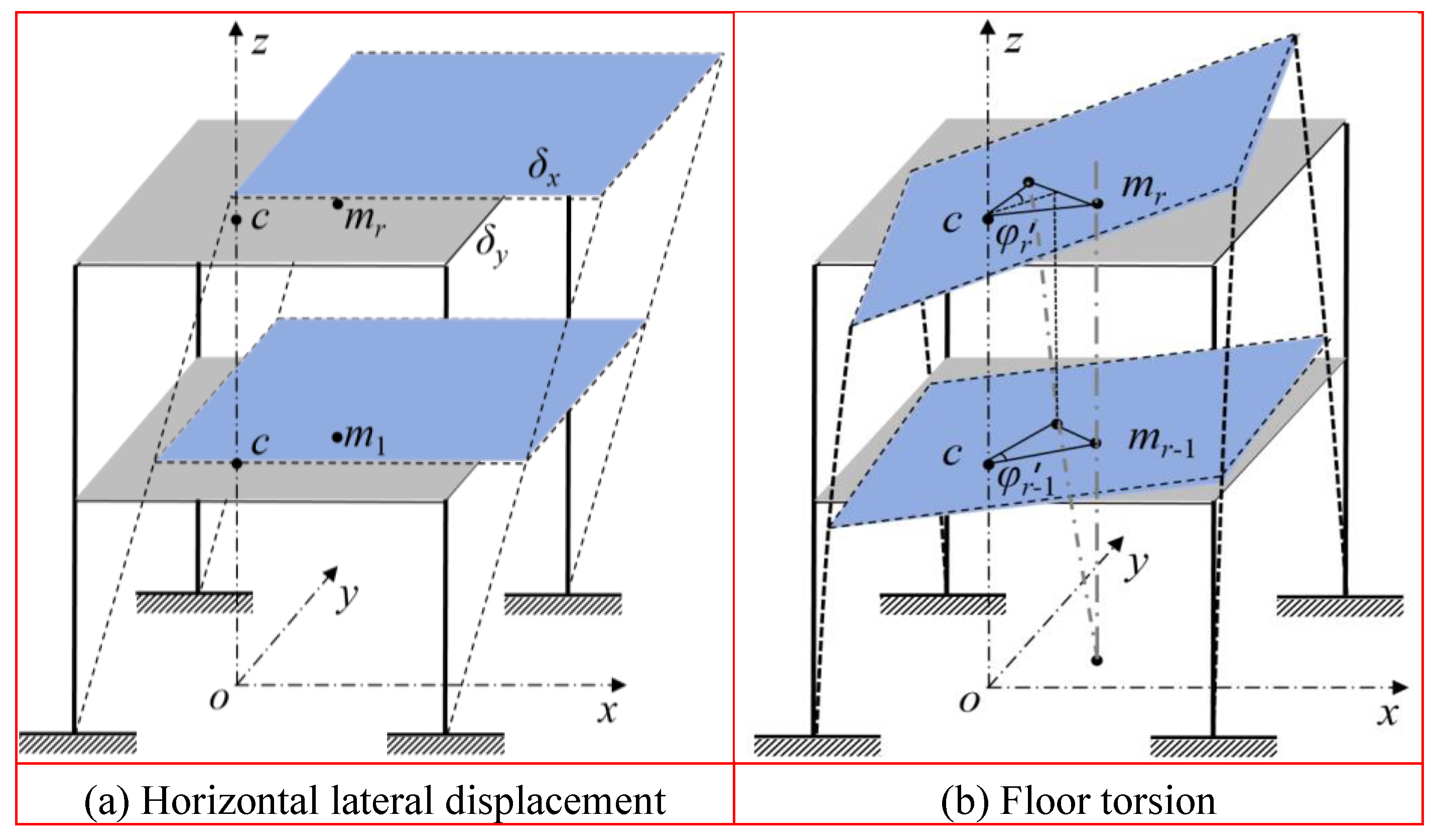

3.2.1. Natural Vibration Frequency Variation

Considering the ground rotation effect, Equation (9) presents the variation of the natural vibration frequency of a structure as a function of the relative eccentricity

ey/

r, the torsional to axial period ratio induced by ground rotation

Tφt/

Tu, and the torsional period ratio due to eccentric torsion

Tφe/

Tu.

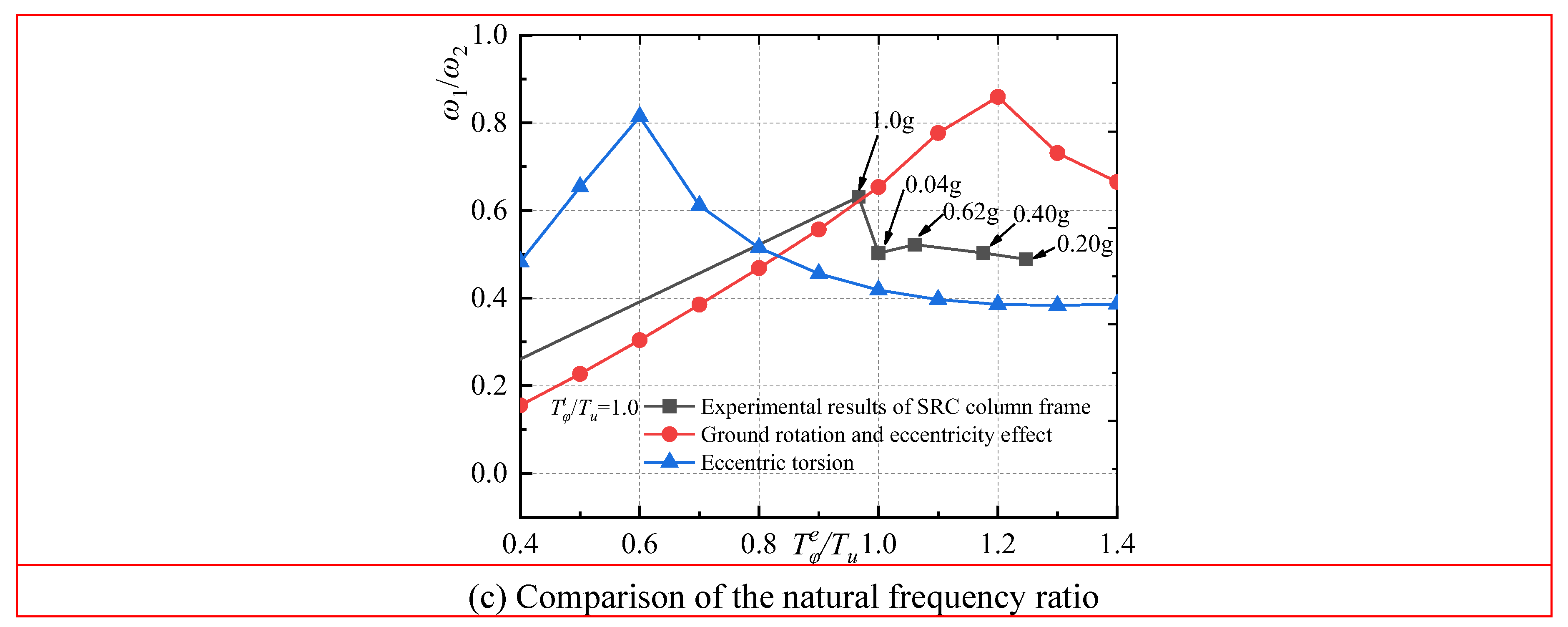

Figure 3 illustrates the natural vibration frequency variation ratio

ω1/

ω2 between the first and second order modes of the structure. The figure reveals that, when solely considering the torsional period ratio with

Tφe/

Tu < 0.75, the ratio

ω1/

ω2 increases as the torsional period ratio

Tφe/

Tu increases. When

Tφt/

Tu ≥ 2.0 and

Tφe/

Tu is approximately 0.8, the ratio

ω1/

ω2 reaches a peak value. Following this, the ratio

ω1/

ω2 gradually decreases, and the rate of decrease diminishes as the torsional period ratio increases. Additionally, when

Tφt/

Tu ≤ 1.0 and

Tφe/

Tu = 1.25, the ratio

ω1/

ω2 also displays a distinct peak. This indicates that as

Tφt/

Tu continues to increase, the peak value of

ω1/

ω2 occurs earlier, and it tends to stabilize when

Tφt/

Tu ≥ 2.0.

3.2.2. Torsional Amplitude

Considering the ground rotation effect, the ratio of the torsional component amplitude to the translational component amplitude can be derived from Equation (12) as follows:

where

ωx represents the natural vibration frequency of the structure without considering torsional coupling, and

ωφ denotes the torsional natural vibration frequency, taking into account the ground rotation effect.

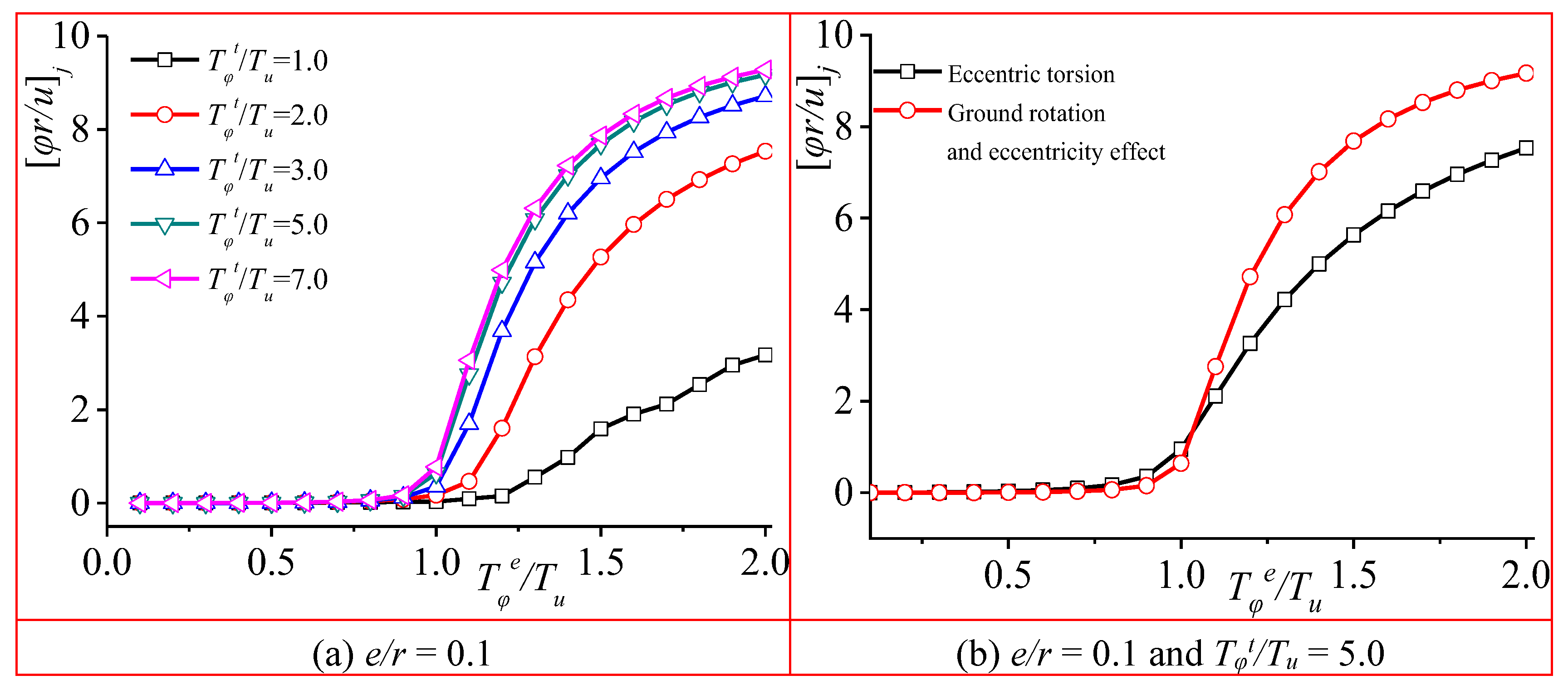

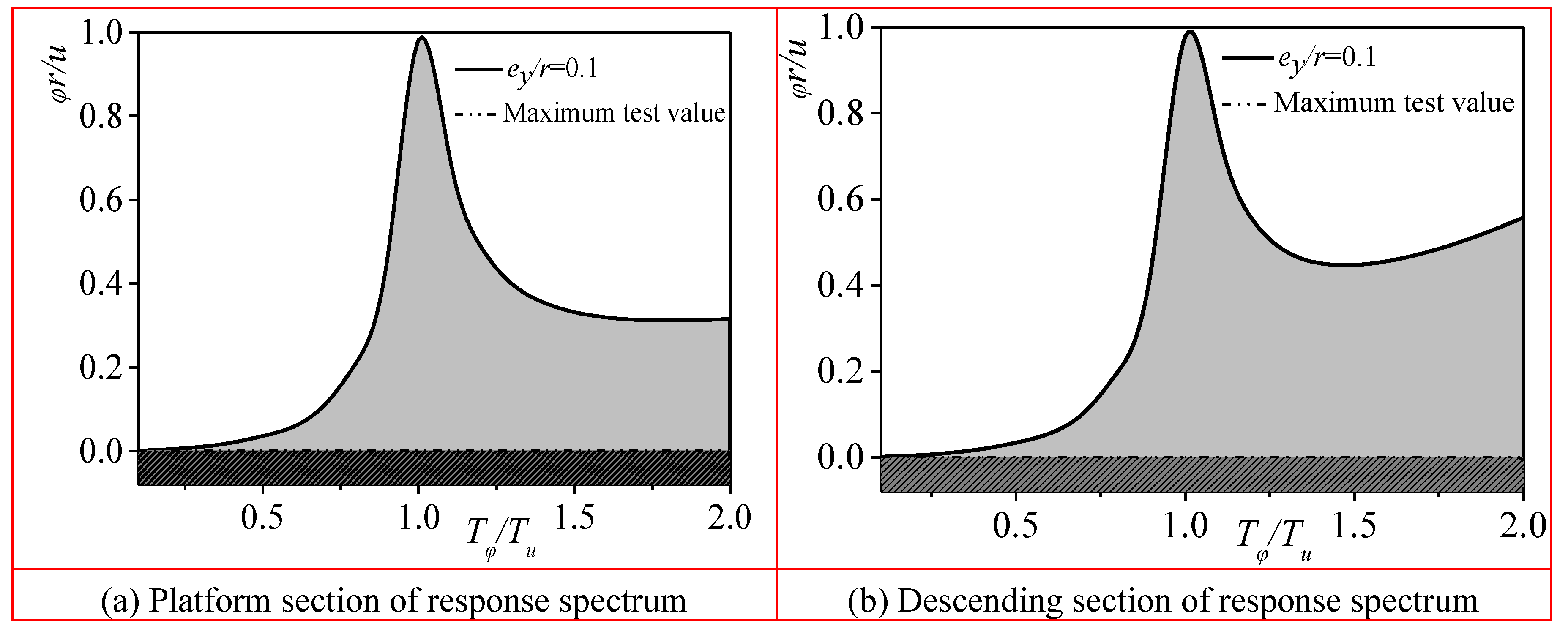

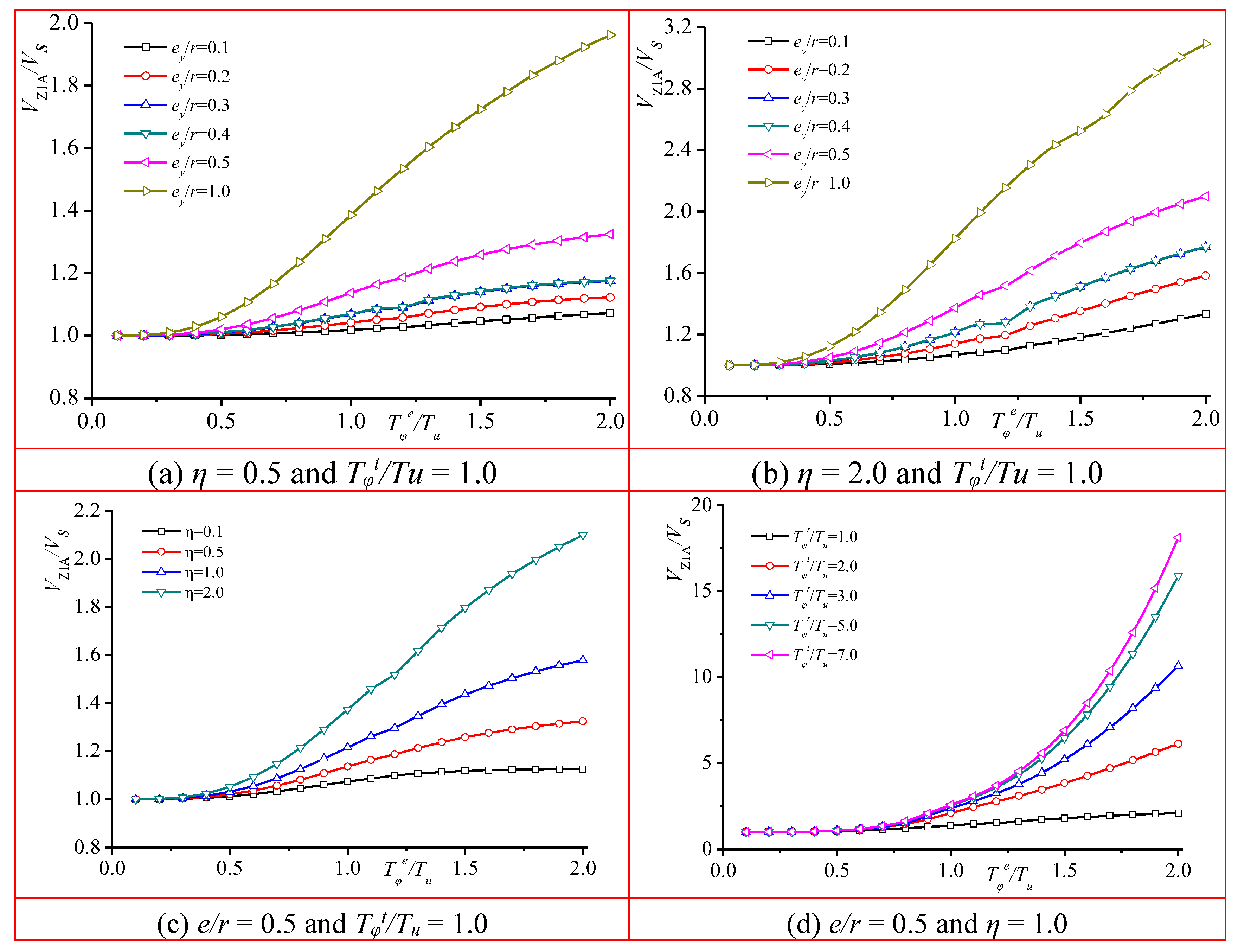

Figure 4 illustrates the variation pattern of the ratio of the torsional component to the translational component amplitude in the structure, taking into account ground rotation. The graph showcases the torsional amplitude variation pattern under the consideration of ground rotation and highlights its consistency patterns when eccentricity is also considered. When the relative eccentricity

ey/

r remains constant, and the ratio of the torsional period caused by ground rotation to the uncoupled period

Tφt/

Tu is held constant, the torsional amplitude experiences a significant increase after

Tφe/

Tu exceeds 1.0.

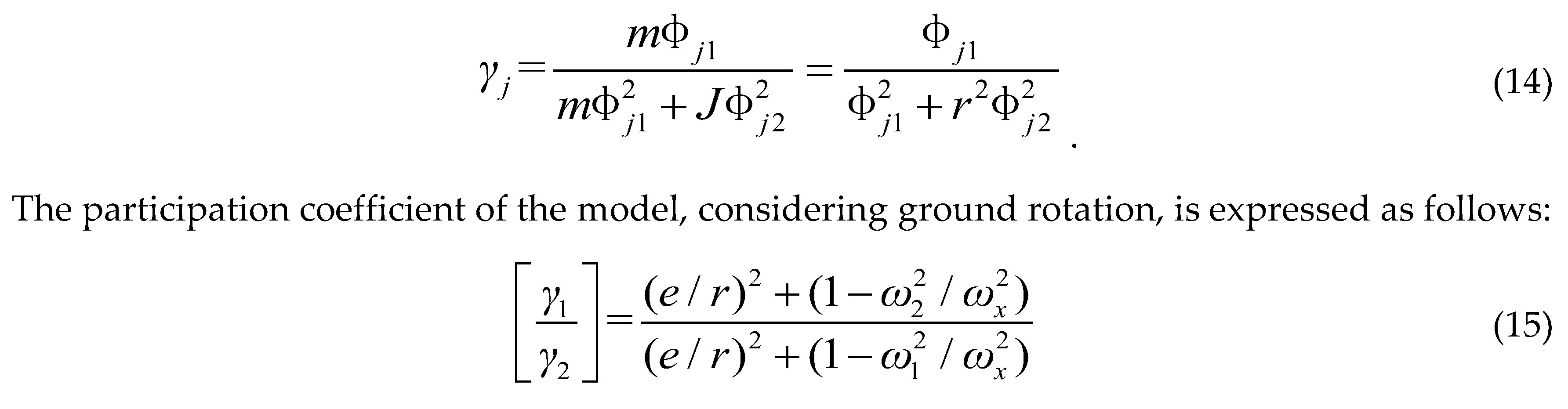

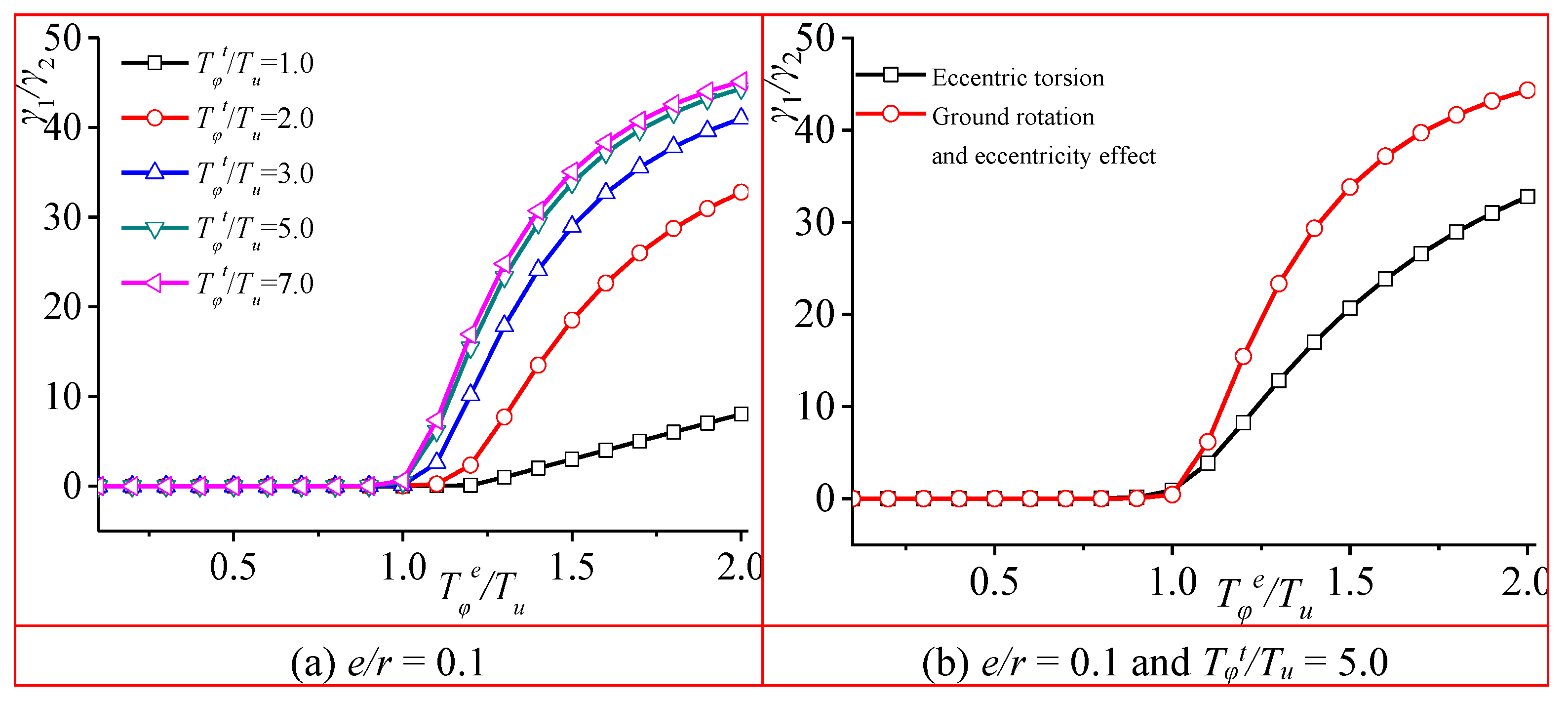

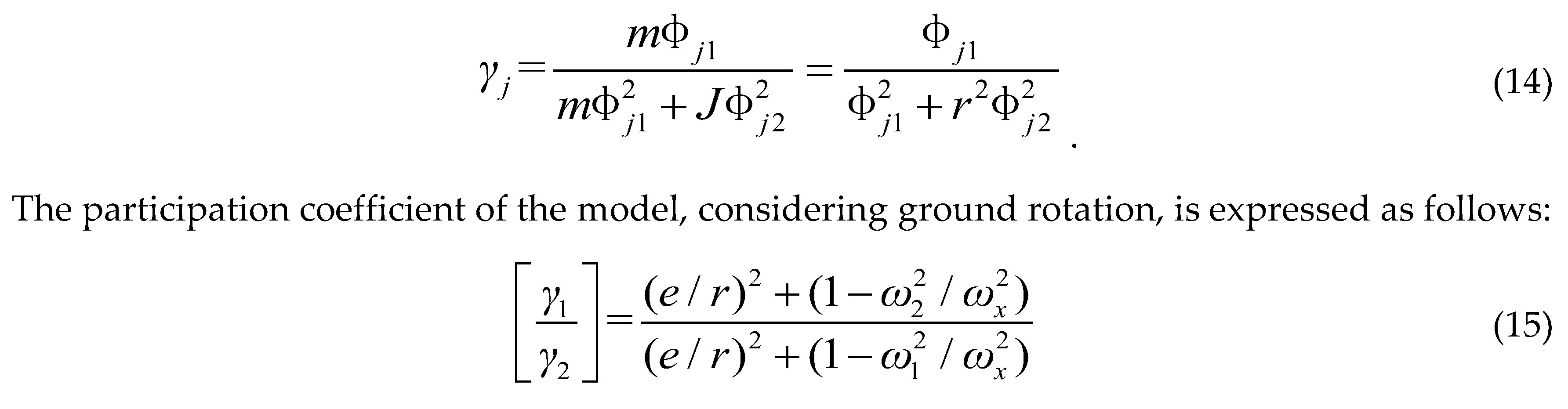

3.2.3. Participation Coefficient

The participation coefficient of the model during lateral-torsional vibration in the

Y direction can be derived from Equation (11) as follows (Kuang and Liu 2022) [

12]:

where ωx represents the natural vibration frequency in the X direction, disregarding any torsional coupling effects; whereas ω1 and ω2 denote the natural vibration frequencies of the structure, accounting for ground rotation.

Figure 5 illustrates the participation level of the model when the ground rotation effect is taken into account. The figure reveals that the pattern of variation in the participation coefficient, when considering ground rotation, is consistent with the pattern observed when considering eccentricity. Specifically, when the relative eccentricity

ey/

r and the ratio of the ground rotation-induced torsional period to the fundamental period

Tφt/

Tu, remain constant after

Tφe/

Tu > 1.0, the participation level of the first mode is notably higher compared to the case where only eccentricity is considered.

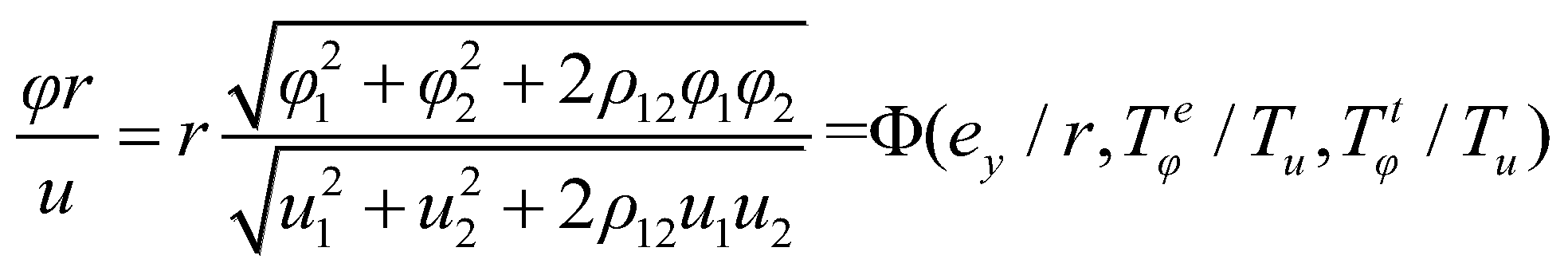

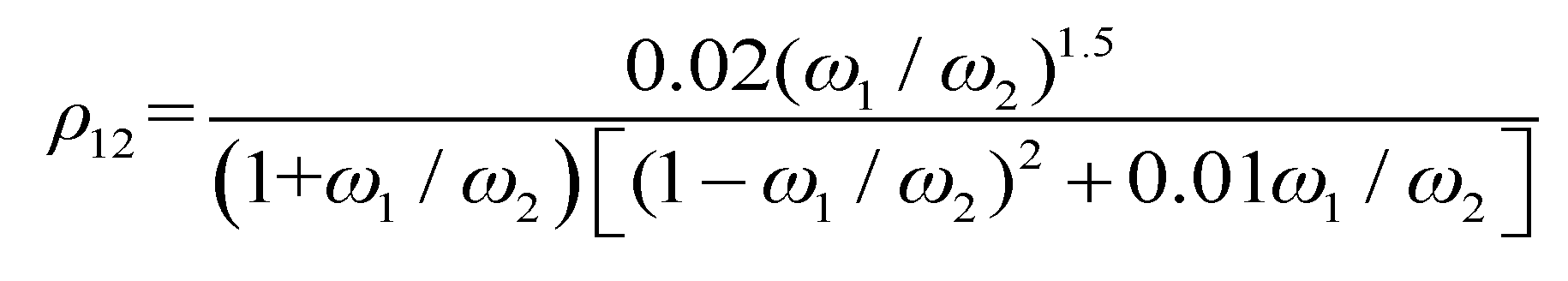

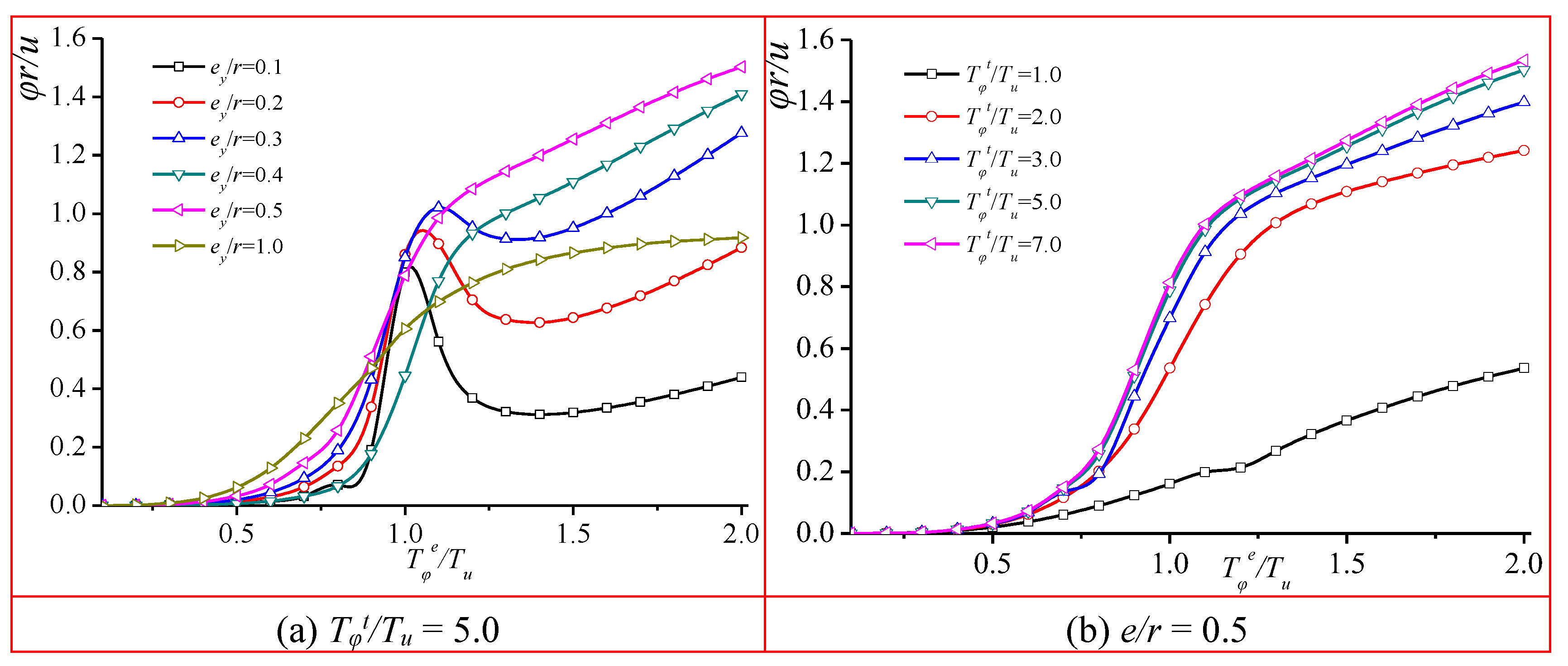

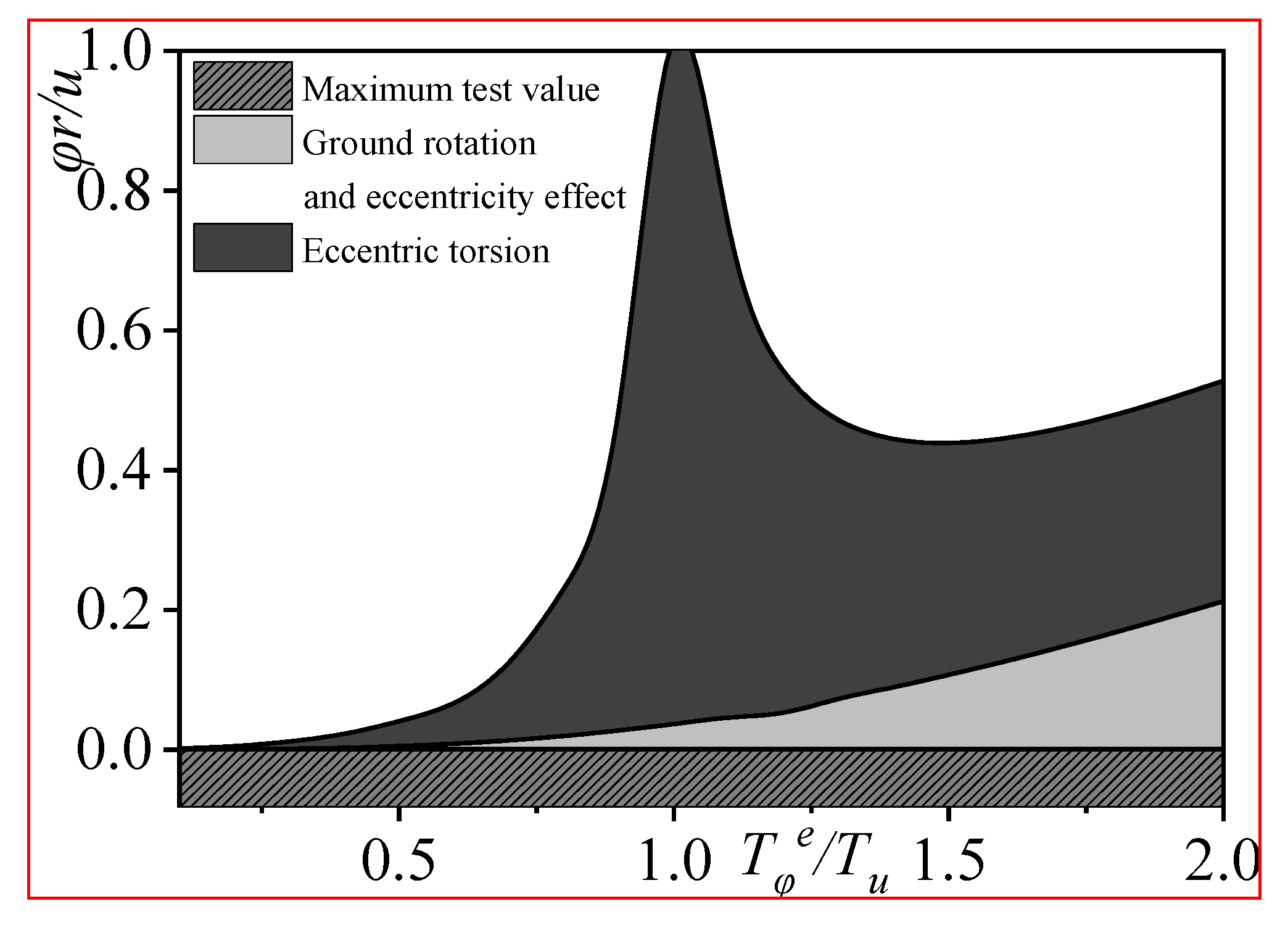

3.2.4. Relative Torsion Effect

By incorporating the amplitude ratio and participation coefficients into Equation (12), the translational and torsional displacements in the

X direction for each mode can be determined. The modal analysis is conducted using the modal decomposition response spectrum method, and the seismic response is calculated employing the Complete Quadratic Combination (CQC) method. The resultant relative torsion effect indicator

φr/

u takes into account the influence of ground rotation.

where

φ and

r represent the torsional angles and rotational radius of the floor, respectively;

u denotes the center of mass displacement;

φr is the rotational radius displacement induced by torsion;

Tφe/

Tu is the non-coupled lateral–torsional period ratio accounting for eccentricity; and

Tφt/

Tu is the lateral–torsional period ratio resulting from ground rotation. The coupling coefficients for the first and second modes, denoted as

ρ12, are calculated as follows (Mao et al. 2022) [

16]:

Figure 6 demonstrates that when

Tφt/

Tu ≥ 2.0 and

Tφe/

Tu ≤ 0.75, the relative torsion effect

φr/

u increases as the relative eccentricity

ey/

r increases. Conversely, when

Tφt/

Tu ≥ 1.4, the relative torsion effect

φr/

u decreases as the relative eccentricity

ey/

r increases. When the relative eccentricity

ey/

r is held constant, the relative torsion effect

φr/

u gradually increases alongside

Tφt/

Tu. For

Tφt/

Tu ≤ 1.0, the relative torsion effect

φr/

u exhibits a linear increase. However, when

Tφt/

Tu ≥ 2.0, a notable increase in the torsion effect is observed at the "knee point" when

Tφe/

Tu = 0.75.

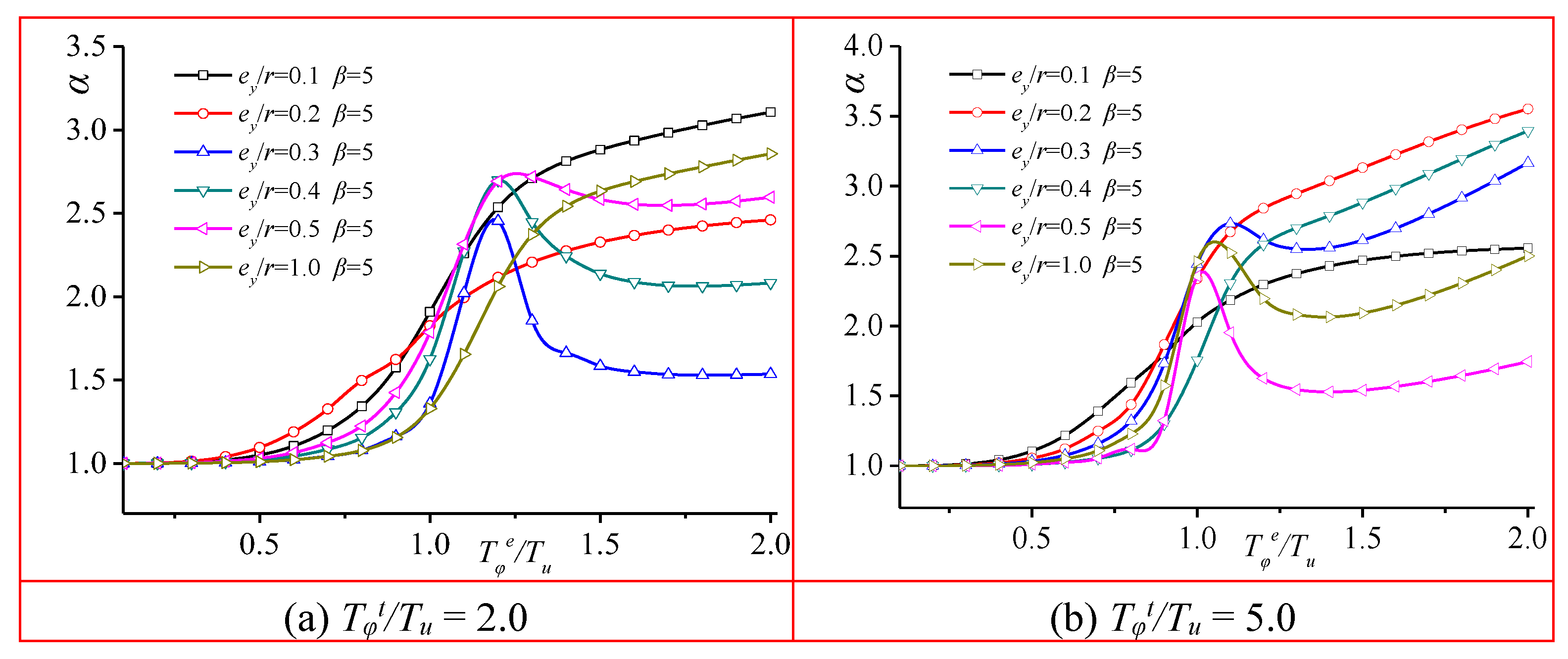

3.2.5. Torsional Control Indicator

The primary torsional control indicators for the structure encompass the torsional displacement ratio, relative eccentricity, and torsional period ratio. In accordance with the "Code for Seismic Design of Buildings" (GB50011-2010), this paper utilizes the torsional displacement ratio, which takes into account ground rotation effects, as the torsional control indicator for special-shaped column frame structures. The torsional displacement ratio signifies the ratio of the maximum displacement to the average displacement of a vertical structure; it is mathematically expressed as (Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. 2016) [

19]:

where

δmax and

δmin represent the floor or inter-story displacements at both ends of the structure under seismic action, and

δave denotes the average floor or inter-story displacement under seismic action.

By introducing the geometric relationship among relative

eccentricity, the centroid of the structural plane, and the shape's center, and

by substituting the relative torsional effect indicator

φr/u into the

aforementioned equation while accounting for ground rotation effects, the

relationship between the torsional displacement ratio

α and the

fundamental torsional periods ratio caused by eccentricity and ground rotation

can be expressed as:

where

β represents the aspect ratio of the structural plane, defined as

β =

a/

b (where

a is the length, and

b is the width).

Figure 7 illustrates

the relationship between the torsional displacement ratio

α and the

lateral-torsional periods ratio caused by eccentricity and ground rotation. The

figure indicates that the torsional displacement ratio

α increases as

the lateral-torsional periods ratio caused by eccentricity and ground rotation

increases. As the lateral-torsional period ratio increases, the "knee

point" of the relationship curve continues to rise. Under constant aspect

ratio conditions, eccentricity, and structural dimensions, and when ≥ 3.0, the

increasing trend of the torsional displacement ratio

α and the

lateral-torsional periods ratio caused by eccentricity and ground rotation

diminishes; especially when ≥5.0, the variation

curve of the torsional displacement ratio

α almost overlaps.

4. Shaking Table Test of Special-Shaped Column Frame Structure

4.1. Test Survey

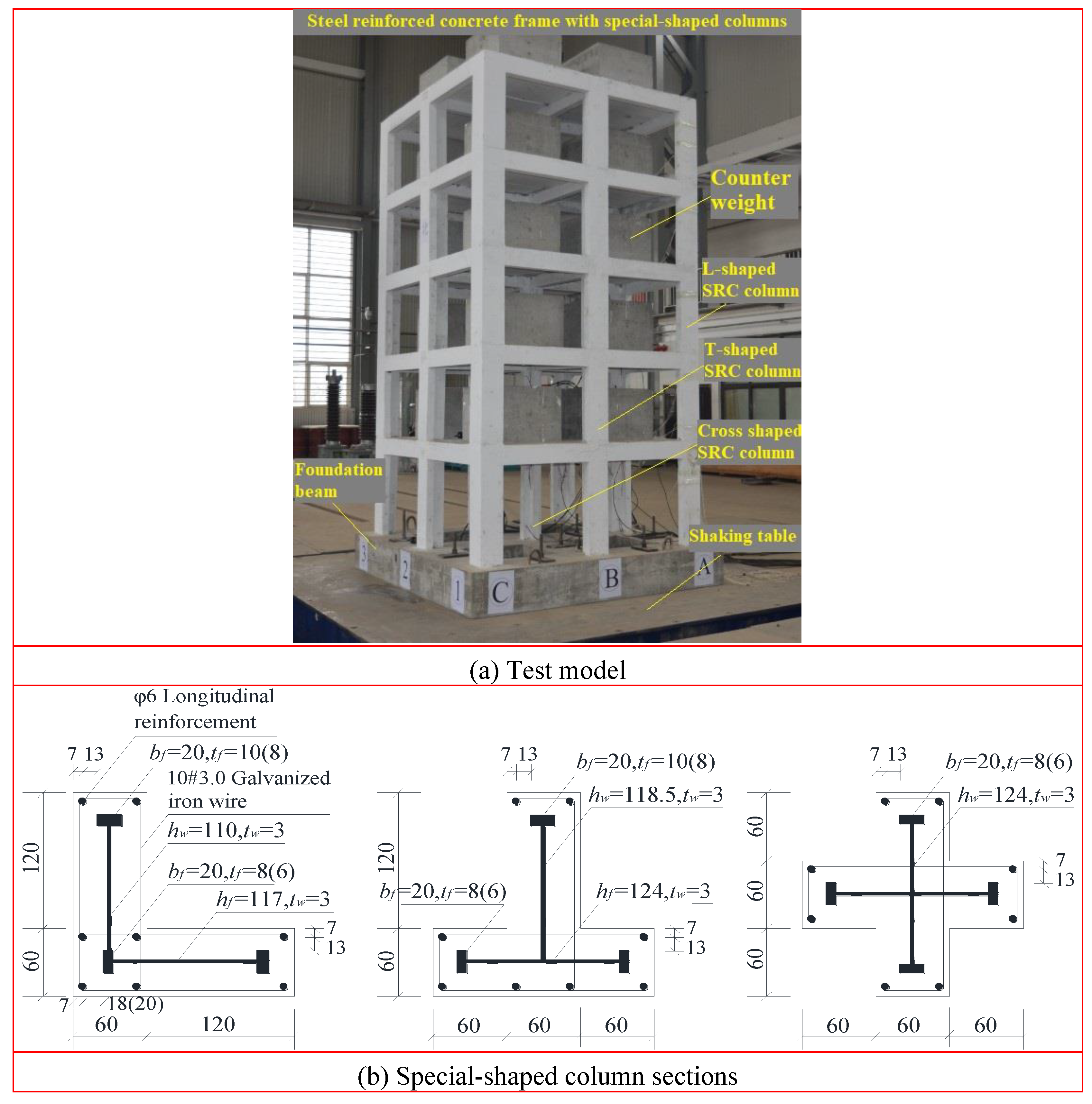

A structure model of 5-storey solid web steel reinforced concrete spatial frame with special-shaped column at the similarity ratio of 1:4 based on the dynamic similarity relationship is designed to obtain the displacement response, acceleration response and strain response of the steel reinforced concrete frame with special-shaped column under 3D earthquake. The model structure is symmetrically arranged in the plane. To be specific, the frame has a span length of 1000 mm, the ground floor has a height of 900 mm, and the height of the second to fifth floors is 750 mm, as presented in

Figure 8(a). The lateral force resisting members of the structure comprise L-shaped, T-shaped, and cross-shaped steel reinforced concrete special-shaped columns. As depicted in

Figure 8(b), Q235 steel serves as the column steel, HPB300 grade reinforcement is the stressed reinforcement, 10#3.0 galvanized iron wire serves as the stirrup, and C30 particulate concrete is employed as the concrete. The frame beam is a reinforced concrete rectangular beam with a section size of 60 mm×140 mm. Moreover, the slab is a reinforced concrete cast-in-situ slab with a thickness of 40mm. The model is fully weighted, and the weight of the respective floor is 1.6 t. The axial compression ratio of the middle column on the bottom floor under vertical load is 0.11.

In the test, El Centro wave, Taft wave and Lanzhou artificial wave are selected as the excitation waveform of the mesa, and the peak acceleration input of the mesa is adjusted at the 1:0.67 similarity ratio. There are 60 working conditions (e.g., white noise) after adjustment, and the peak acceleration is set as follows: 0.07 g, 0.14 g, 0.20 g, 0.40 g, 0.62 g, 0.80 g, 0.90 g, 1.0g and 1.1g. In the test of the same earthquake grade, the time interval is adjusted at the 1:2 similarity ratio. The seismic waves in the respective region are input in one direction, two directions, and three directions, respectively. The X, Y, Z three-way acceleration ratio is 1:0.85:0.65. During the test, the dynamic response of the model structure is examined using the accelerometer, the displacement pickup and the strain sensor.

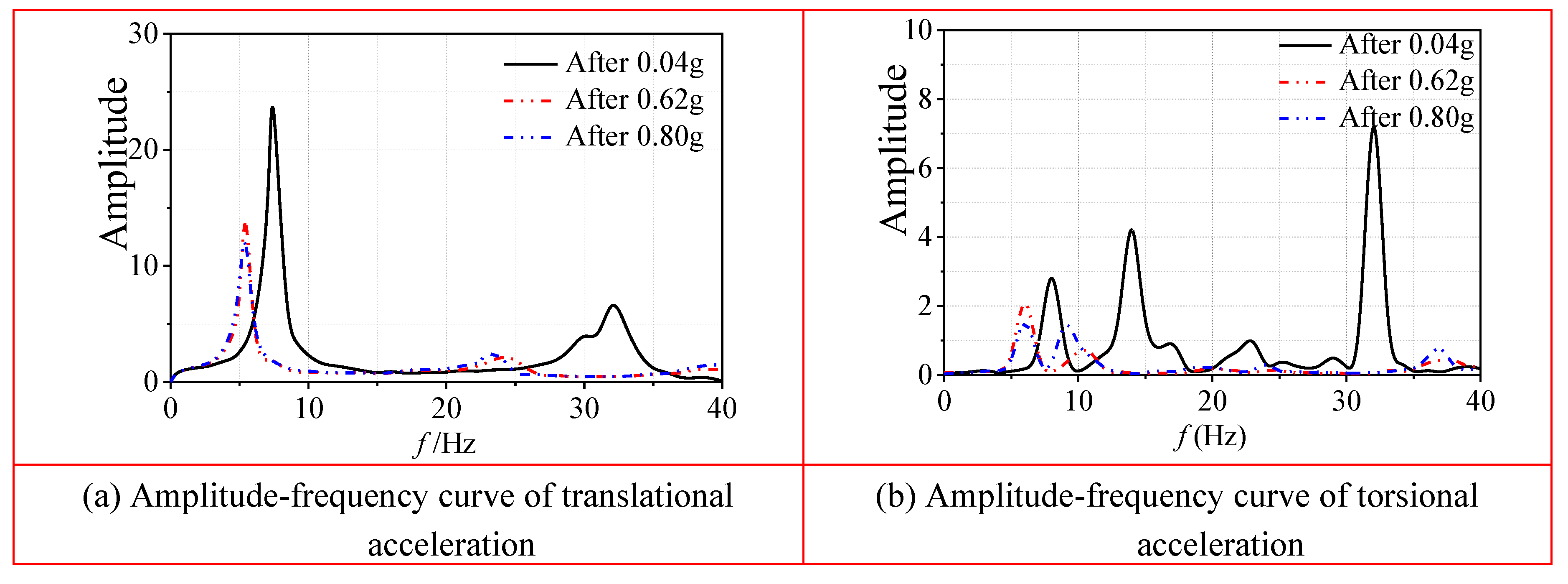

The frequency response function (transfer function) for each floor is determined by conducting a frequency domain analysis of the excitation and output signals. Using the transfer function, the amplitude-frequency and phase-frequency curves of the model are generated. The damping ratio of the model structure, which reflects its energy dissipation characteristics, is determined using the half-power approach of the transfer function curve (Ismai 2020)[

11]. The transfer function curve is also used to determine the vibration pattern of the model; the amplitude-frequency and phase-frequency curves of each floor relative to the ground floor are obtained using the transfer function (Ismai 2020)[

11]. After normalizing the amplitude ratio, the vibration pattern corresponding to the natural vibration frequency is obtained.

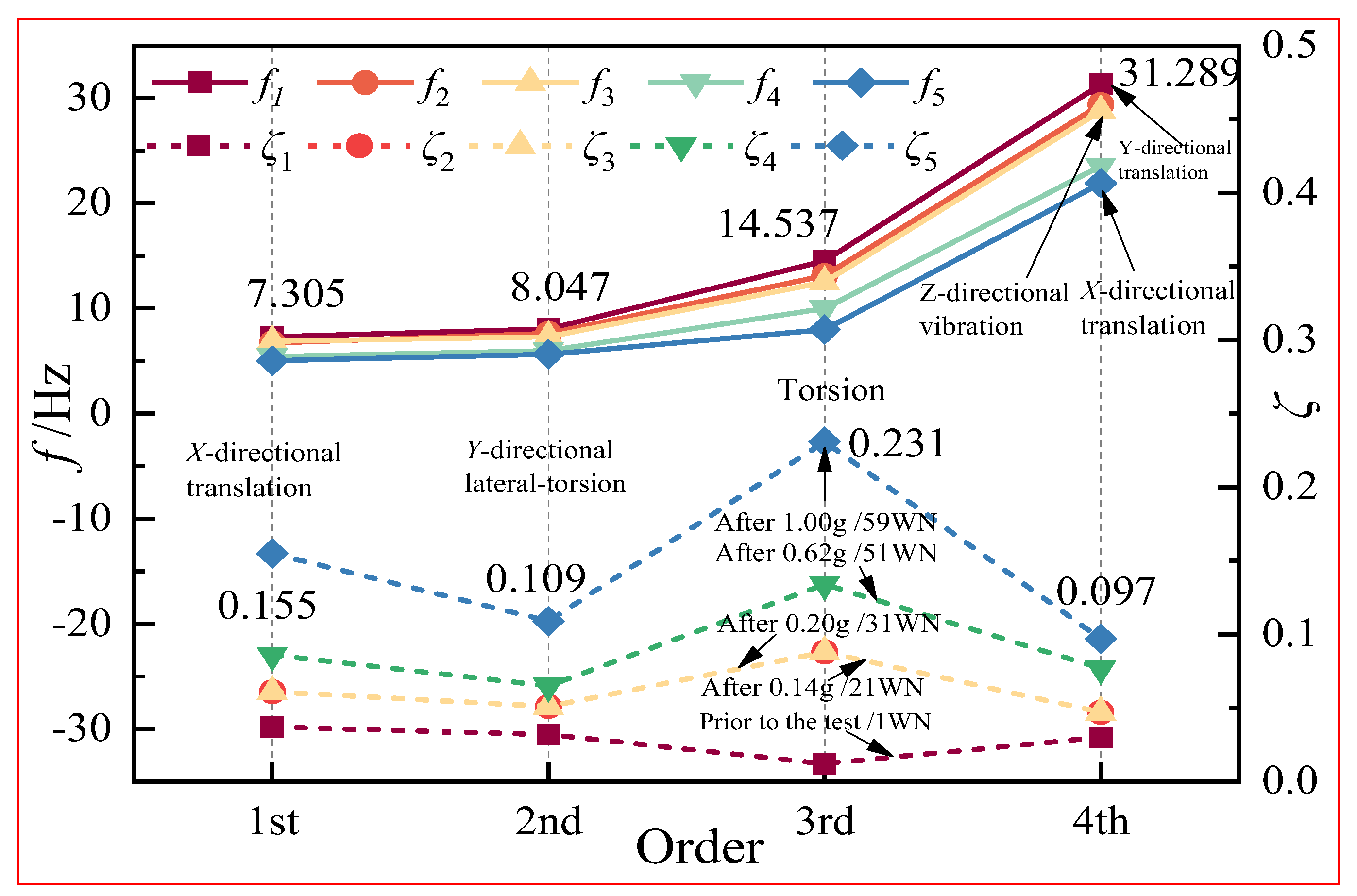

Figure 9 presents the entire natural vibration frequency distribution, damping ratio, and vibration pattern of the SRC special-shaped column structure subjected to 3D seismic action, where

f is the natural vibration frequency of the model,

ζ is the damping ratio, and

Φ(

i) is the vibration pattern.

4.2. Lateral Vibration

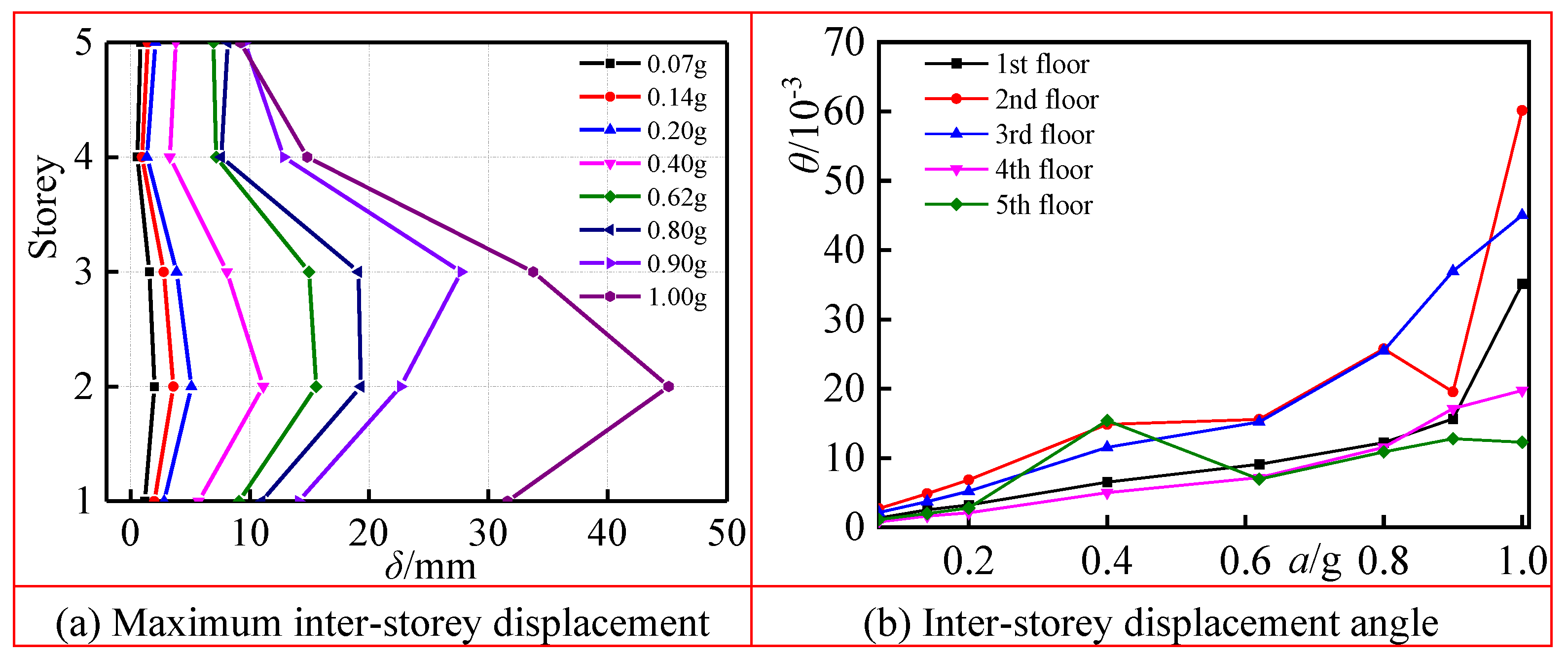

Figure 10 is the inter-story displacement envelope diagram of the model. As depicted in the figure, with the increase of the peak acceleration, the inter-story displacement response of each layer increases, and the inter-story displacement in descending order are 2nd floor, 3rd floor, 1st floor, 4th floor, and 5th floor. Before 0.14 g PHGA seismic wave input, the lateral displacement curve of each layer is basically a straight line, and the structure is at the elastic stage. After 0.40 g PHGA seismic wave input, the 1st and 2nd floor of the model enters the elastic-plastic stage, and the inter-story displacement increases more than that of the 3rd to 5th floor, the overall lateral displacement curve of the structure is S-shaped. After 0.80 g PHGA seismic wave input, the structure enters the elastic-plastic stage. The maximum value of the inter-story displacement angle in the 2nd floor reaches 1/39. Plastic hinges appear at the beam ends of the 3rd floor, and the inter-story stiffness of the model degrades rapidly.

The response of the model to conditioned seismic action indicates that before the peak acceleration reaches 0.14 g, the structure is in an elastic state. When the peak acceleration reaches 0.20 g, the structure experiences its maximum inter-story displacement angle on the 2nd floor, which is 1/146, and various inter-story displacement angles are distributed as θ2 > θ3 > θ1 > θ4 > θ5. Between peak accelerations of 0.40 g and 0.62 g, the maximum inter-story displacement angle of the 2nd floor is 1/65, which is lower than the specified requirement of 1/60. When the peak acceleration exceeds 0.80 g, the maximum inter-story displacement angle of the 2nd floor is 1/39, and plastic hinges appear at the beam ends of the 3rd floor with rapid degradation of inter-story stiffness. This inter-story displacement angle exceeds 1/60 as specified in the code, but the structure does not collapse. When the peak acceleration exceeds 0.90 g, the maximum inter-story displacement angle of the 3rd floor reaches 1/17, and as the peak ground acceleration increases, deformation at the beam ends of the 1st to 3rd floors continuously increases, and the steel reinforcement at the beam ends gradually experiences stress failure. Plastic hinges appear at the beam ends of the 1st and 2nd floors.

4.3. Torsional Vibration

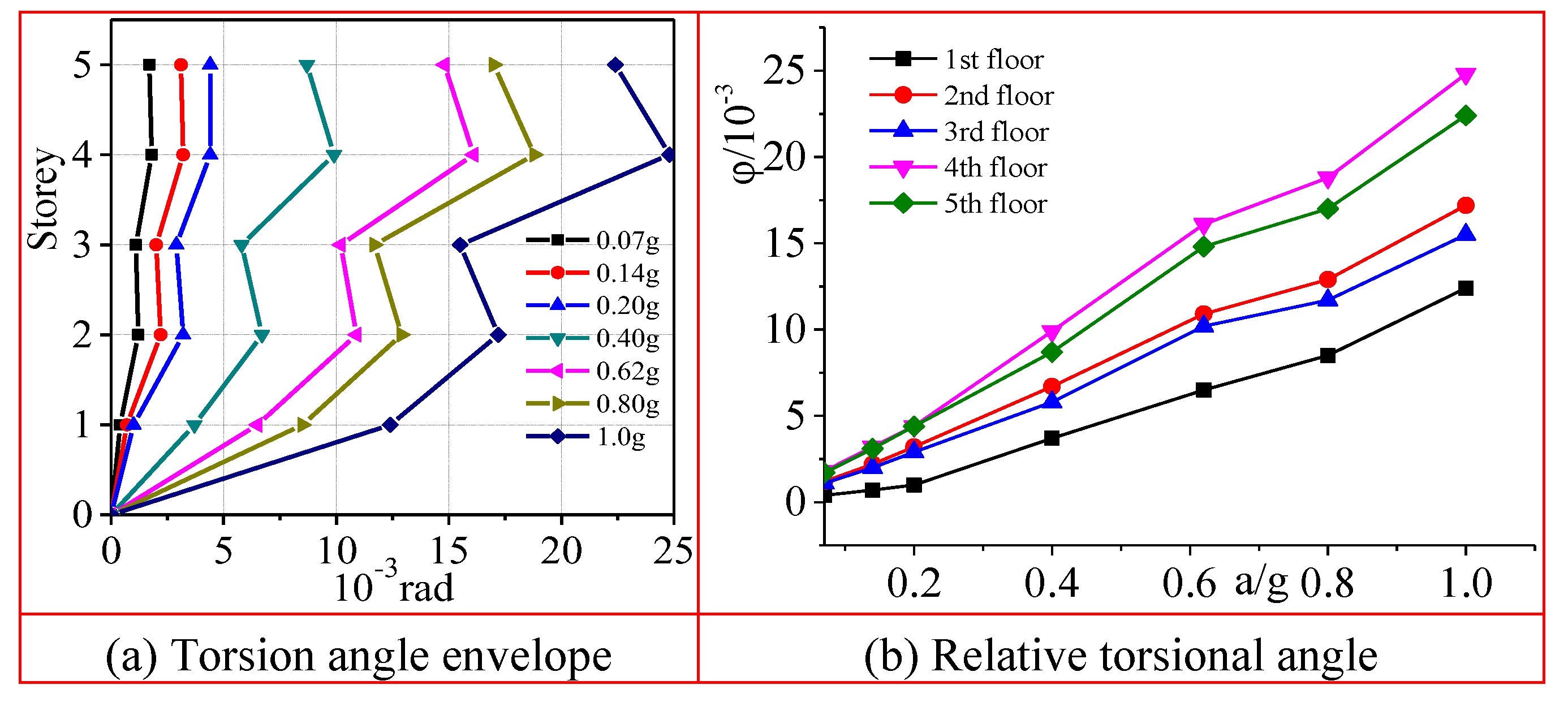

Figure 11 presents the torsion angle envelope diagram of the respective floor relative to the base. The measured seismic response of the shaking table test indicates that under the action of 0.14 g PHGA seismic, the maximum torsional angle is obtained as 3.1×10

-7 rad. The maximum value of inter-story displacement angle caused by lateral-torsional coupling is 1/502 rad, which basically meets the requirements of elastic inter-story displacement angle limit 1/550 rad in Code for Seismic Design of Buildings (GB50011-2010). Under the action of 0.40 g PHGA seismic, the maximum torsional angle is 8.7×10

-7 rad. The maximum value of inter-story displacement angle caused by lateral-torsional coupling is 1/67 rad, thus satisfying the requirements of the elastic plastic inter-story displacement angle limit 1/60 rad in the Technical Specification for Concrete Special Shaped Column Structures (JGJ149-2006). Under the action of 0.80 g PHGA seismic, the maximum torsional angle is determined as 17.0×10

-7 rad. The maximum value of inter-story displacement angle caused by lateral-torsional coupling is 1/39 rad, exceeding the limit value of elastic-plastic inter-story displacement angle, and the model structure enters the fully plastic stage. The analysis of the model structure stiffness and seismic force suggests that when the structure enters the plastic stage, the degradation of the floor torsional stiffness is not significant with the increase of horizontal lateral displacement.

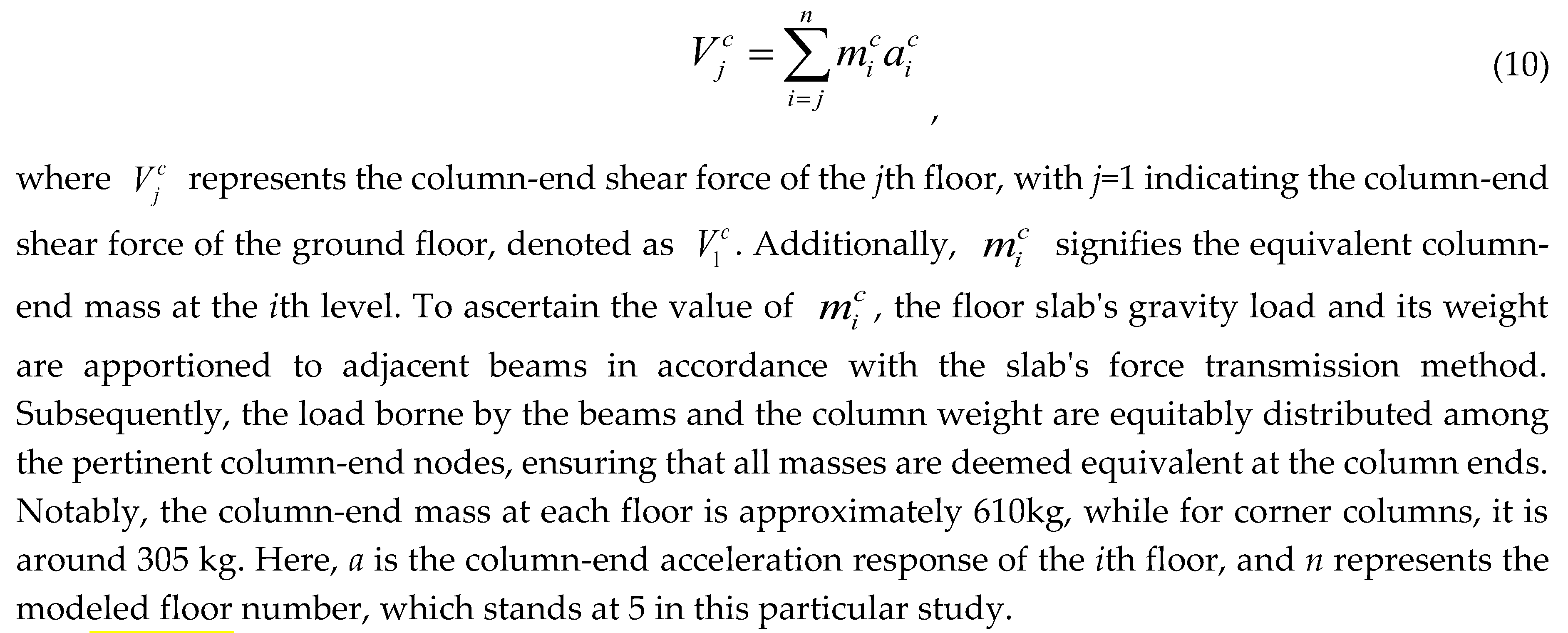

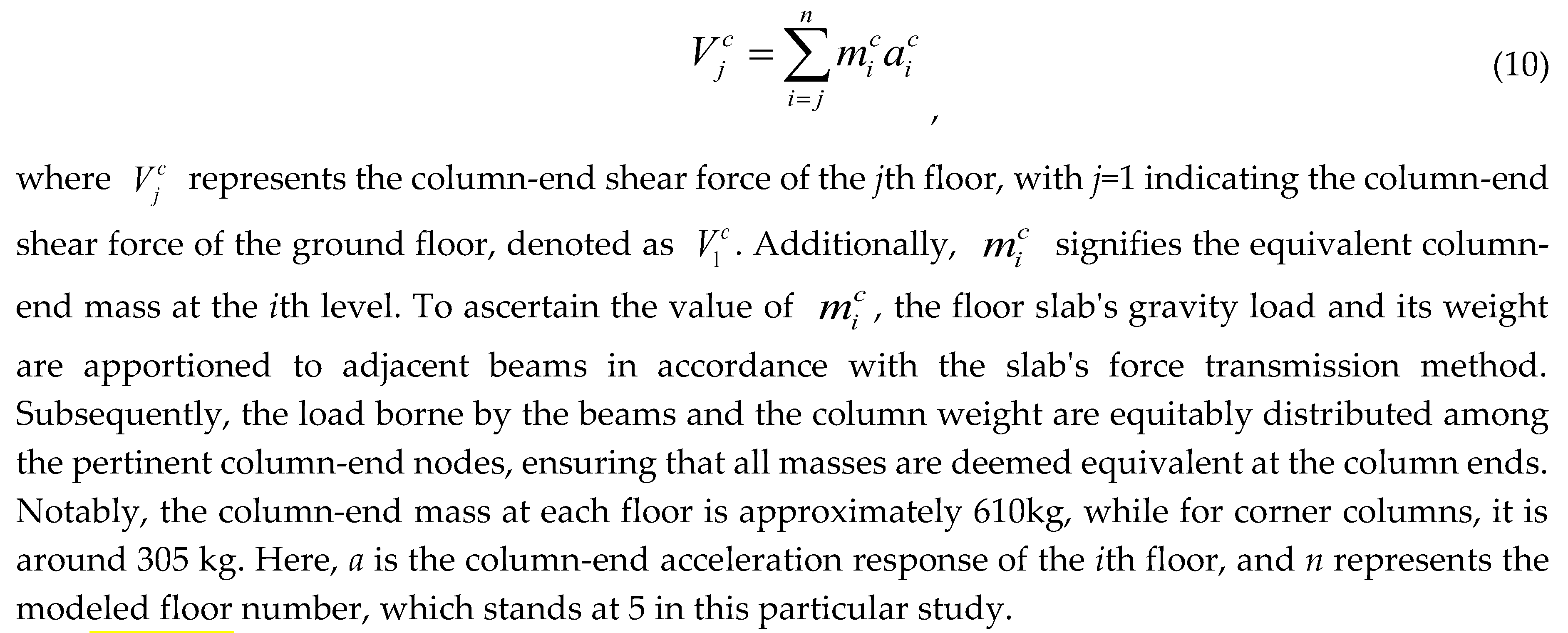

4.4. Seismic Shear

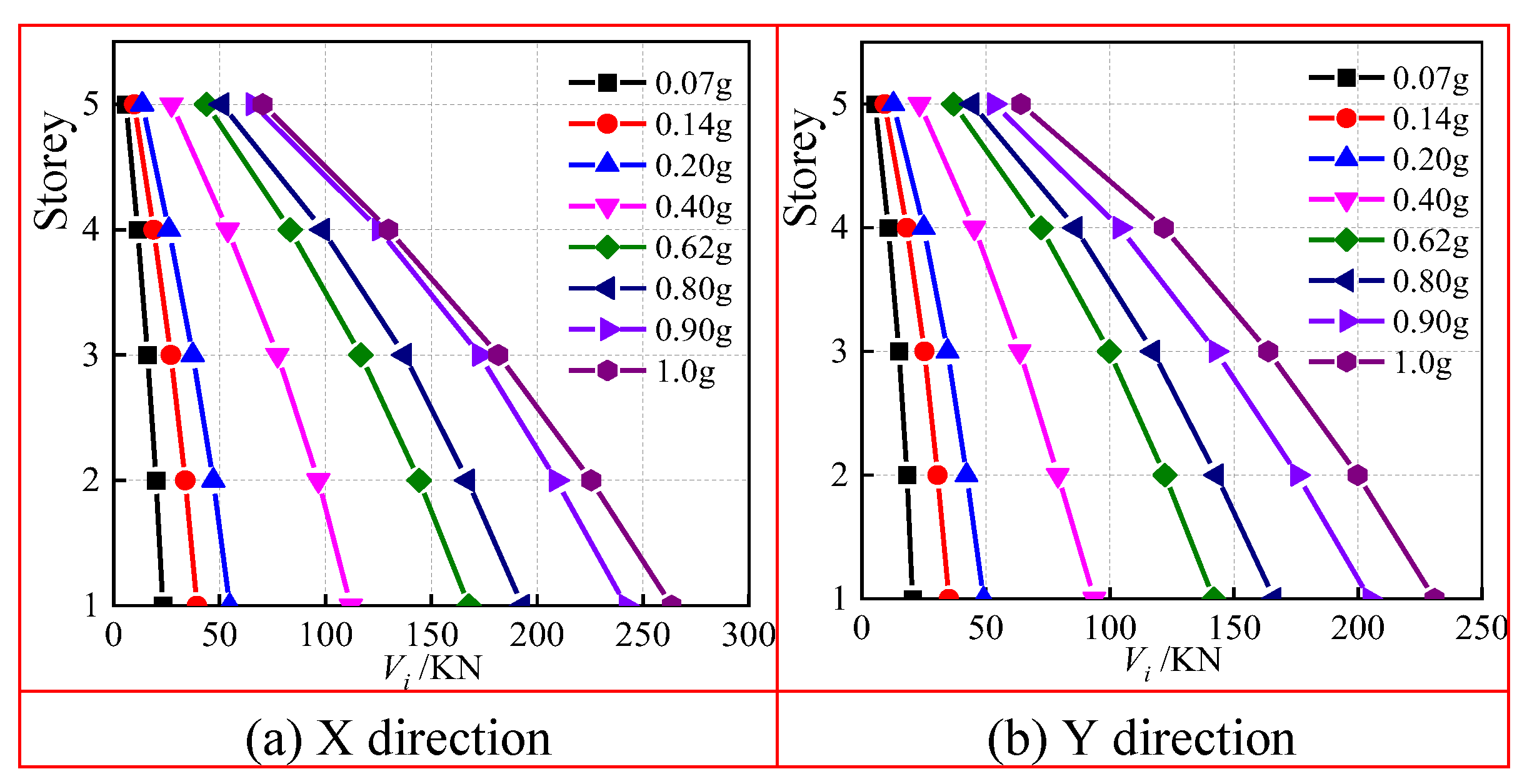

The shear envelope diagram of the floor is shown in

Figure 12. As depicted in the figure, the maximum shear force of the respective floor tends to decrease along the direction of the floor height under the same seismic wave and the same peak acceleration input on the model structure, and the shear force of the floor in Y direction is nearly 75% of the shear force in X direction. Between 0.07 g and 0.20 g PHGA seismic, the maximum shear force of the 1st floor is nearly 50kN, and the structure is at the elastic stage. After 0.62 g PHGA seismic input, the model enters the elastic-plastic stage. The increase of the floor shear force decreases significantly with the increase of the peak acceleration. After 0.80 g PHGA seismic input, with the increase of floor shear force, the plastic deformation of the model structure rapidly deepens, and the cumulative damage increases continuously.

4.5. Column Shear

The column shear force at a specific level is determined by multiplying the measured acceleration values at the column ends of each level by their corresponding equivalent column mass. The aggregate of the inertia forces at the column ends, originating from all the floors above that level and located at the same position, signifies the column shear force at that level. The equation for this calculation is expressed as follows:

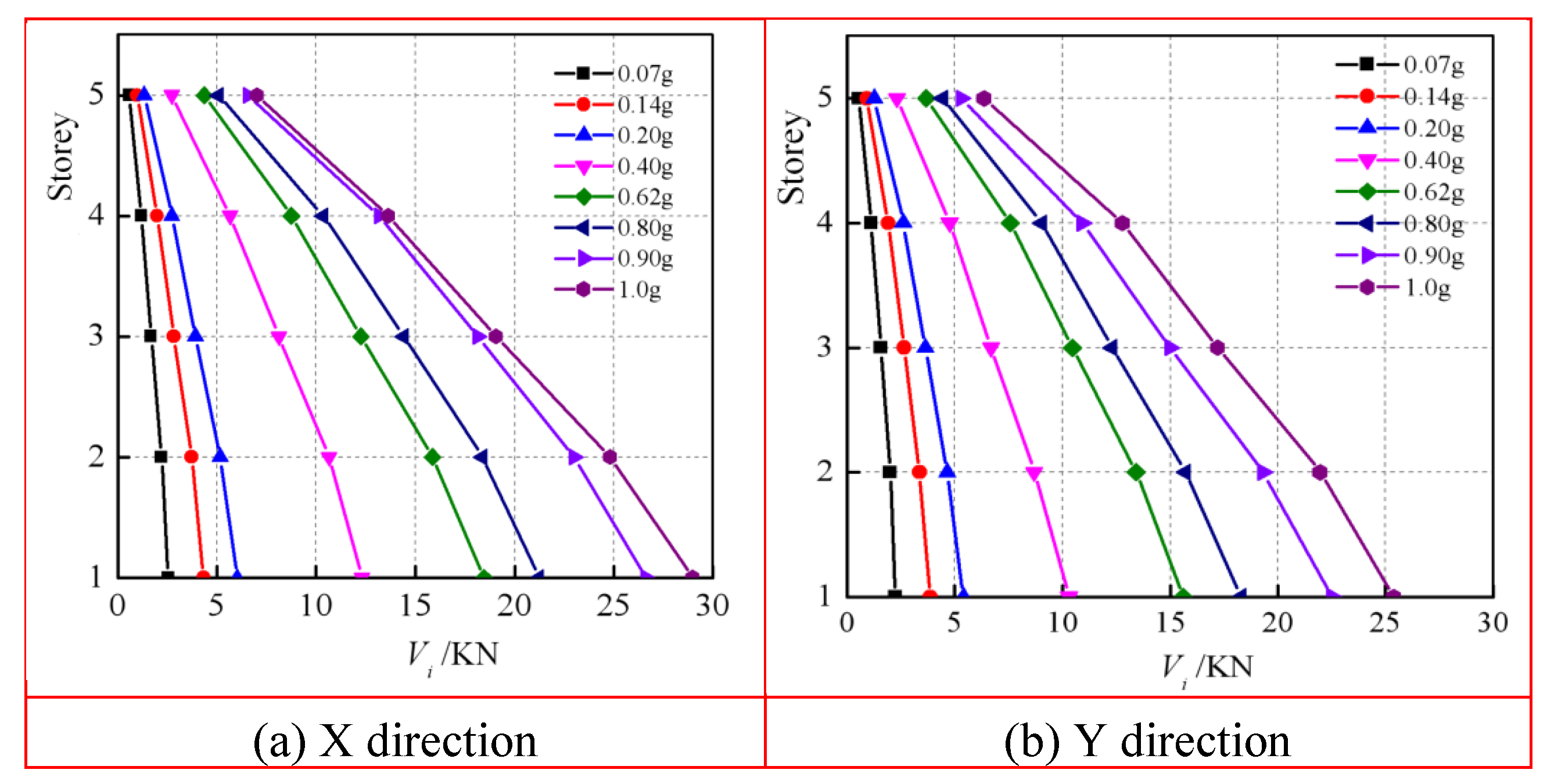

Figure 13 exclusively illustrates the variations in column-end shear force for the ZA2 T-shaped corner column. The graph reveals that the fluctuations in column-end shear force align with the variations in floor shear force observed in the model. Notably, the maximum column-end shear force constitutes approximately 10% of the floor shear force, indicating that the SRC special-shaped column serves as the primary lateral load-resisting component within the model structure. The distribution of column-end shear force is deemed reasonable, adhering to the lateral stiffness of the column.

4.6. Column Torsional Stiffness

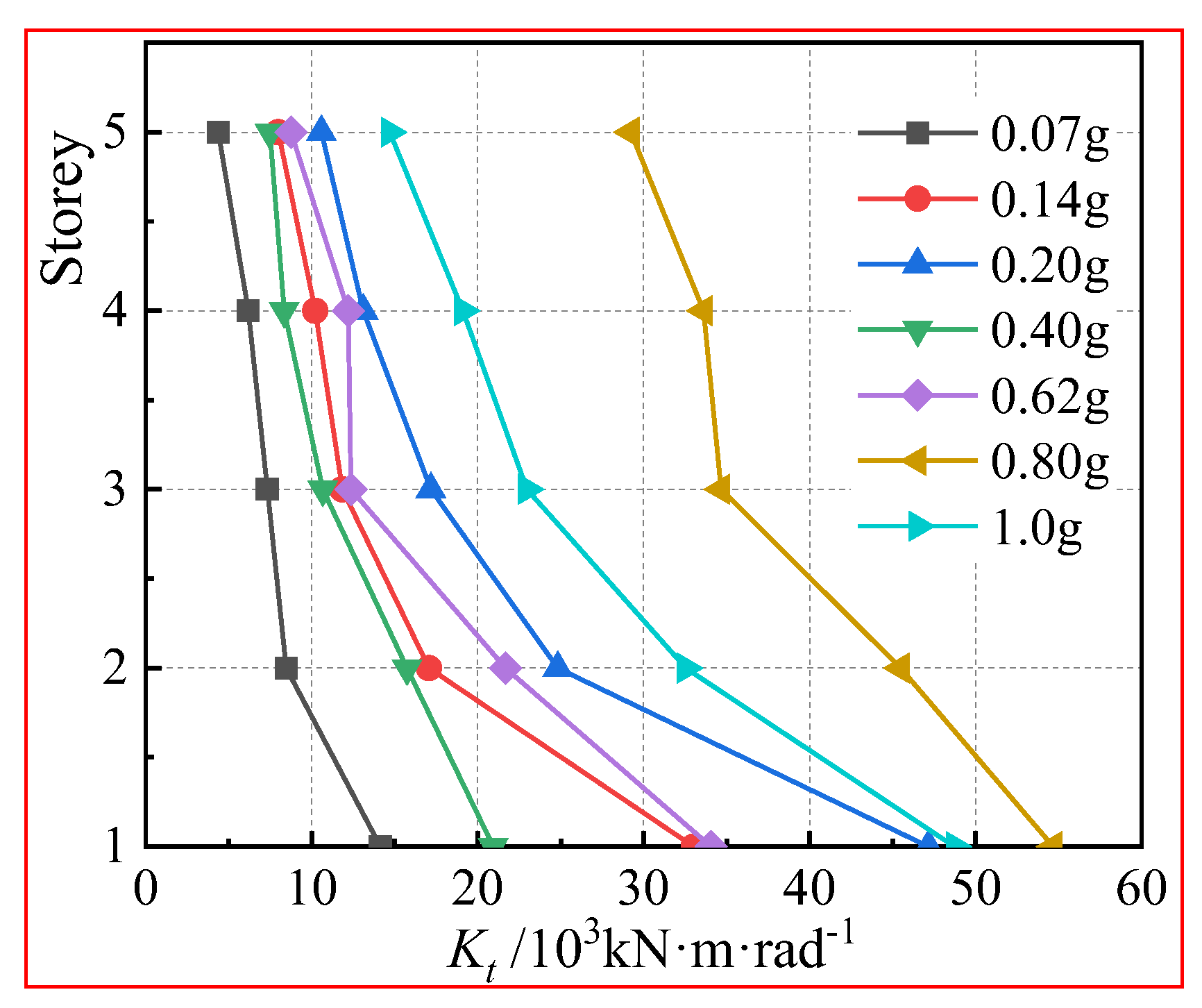

Similarly, the ratio of column torsion to inter-story torsional rotation demonstrates corresponding column torsional stiffness at the same level.

Figure 14 presents the maximum torsional stiffness variations for the ZA2 T-shaped column under the influence of three different seismic waves. The table reveals that the torsional stiffness of the SRC column on each floor increases as the peak ground acceleration increases. Generally, variations in column-end torsional rotation result in minimal torsional deformation of the columns under accidental torsion. Although an increase in torsional deformation is observed during later loading stages, it remains within the elastic torsion range. Therefore, the torsional stiffness of the special-shaped columns corresponds well with their initial torsional stiffness.

5. Comparison Between Experimental Results and Theoretical Calculations

5.1. Comparison of Natural Frequency Ratio

As shown in

Figure 15a,b, the acceleration response signals of the respective layer of the model structure are obtained by scanning the frequency of the model structure with white noise. Subsequently, the acceleration signal on the base serves as the excitation signal, and the acceleration signal on the respective floor is employed as the output signal. The frequency response function (transfer function) of each floor is determined through frequency domain analysis of the excitation signal and the output signal. The amplitude frequency curve and phase frequency curve of the model can be generated using the transfer function. The frequency value corresponding to the peak value of the amplitude frequency curve represents the order natural frequency of the model structure in turn. As shown in

Figure 15(c), the measured structural lateral–torsional natural frequency ratio considering ground rotation is close to the calculated results from the mathematical model. The peak point appears near the lateral–torsional period ratio of 0.89.

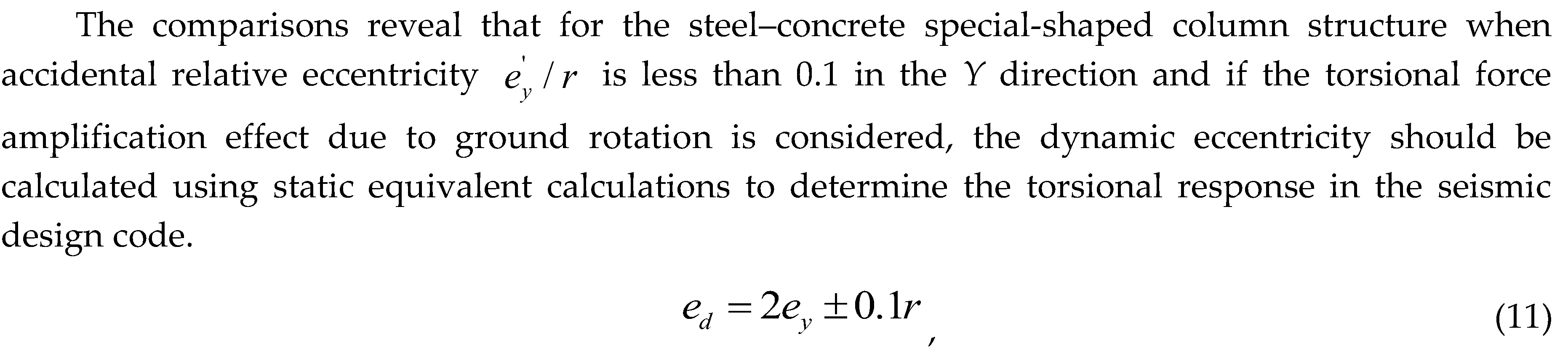

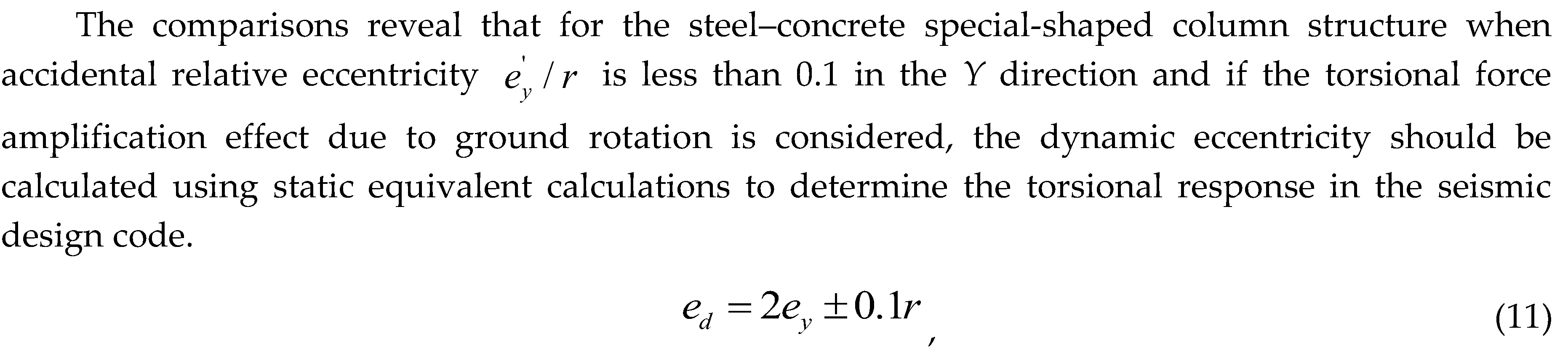

5.2. Comparison of Torsional Effect

The experimental results indicate that the maximum ratio of torsional to horizontal displacements in the

X direction is 0.0007 for the ground floor of the steel-concrete special-shaped column frame structure subjected to tri-directional seismic action.

Figure 16 illustrates the comparison between the theoretical torsional effect and experimental values, taking into account

Y-axis torsion coupling.

Figure 17 shows the comparison between the theoretical torsional effect and experimental values, considering ground rotational components.

where ed is the dynamic eccentricity, ey is the static equivalent eccentricity, and r is the rotational radius of the floor. This equation fully considers the dynamic effect of torsion, the amplification effect of ground rotation on torsion, and the influence of accidental eccentricity.

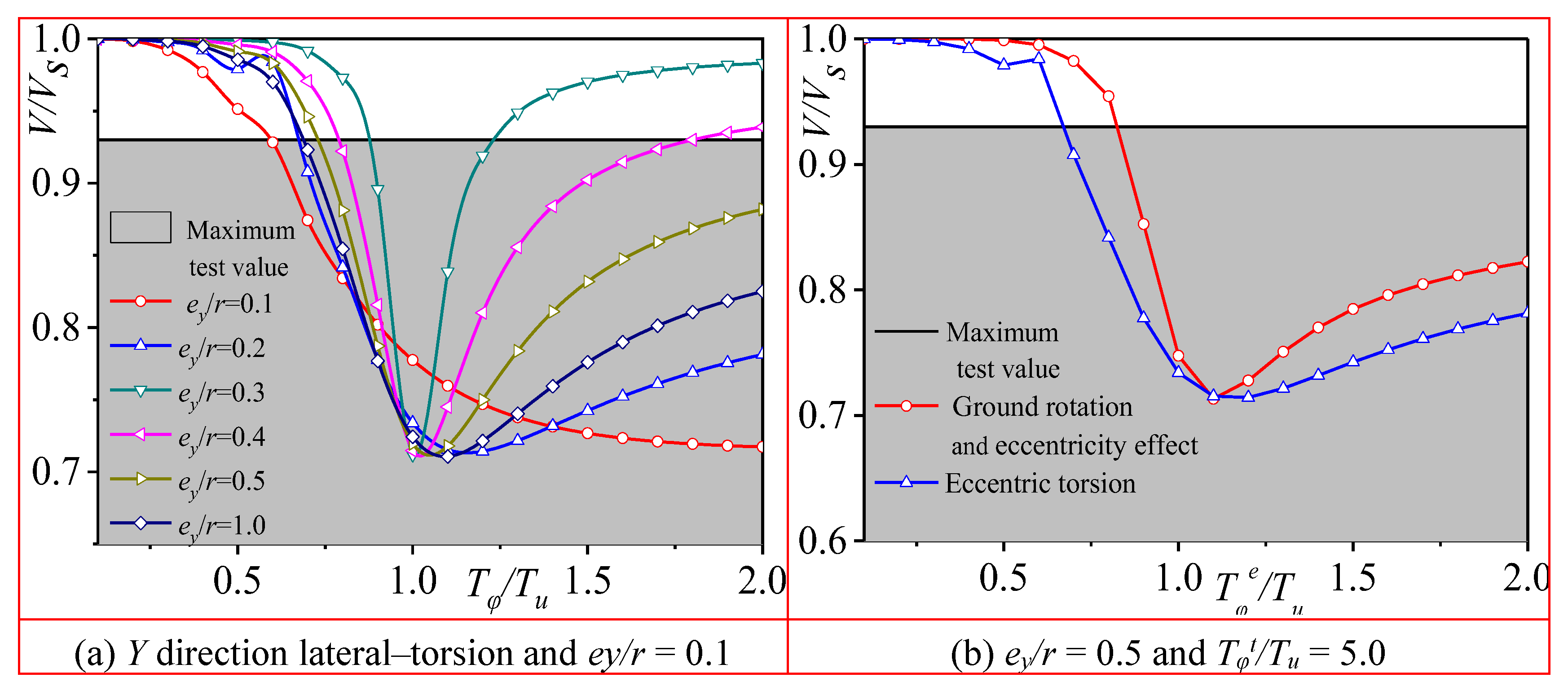

5.3. Comparison of Base Shear

Using the CQC method, the base shear ratio for the structure was obtained, considering both cases with and without coupling, as follows:

The measured base shear ratio of the SRC structure under seismic action, compared to the theoretical base shear value without coupling, is calculated as follows:

where

V1 and

V2 represent the base shear forces generated by horizontal and torsional seismic forces, respectively;

Vm denotes the maximum measured inter-story base shear of the SRC structure;

αG is the corresponding seismic shear without considering coupling; and

α represents the seismic amplification factor, which is taken as the design level of 8 degrees.

Figure 18a illustrates the base shear ratio considering coupling effects on the base shear but without considering coupling within the structure, and it is compared with the measured base shear of the steel-reinforced concrete (SRC) structure.

Figure 18b shows the comparison between the theoretical value of base shear considering ground rotational components and the maximum measured base shear of the SRC structure. The result analysis indicates that the maximum ratio of the measured base shear to the theoretical base shear without considering coupling in the SRC special-shaped column structure under seismic action is 0.93. When

Tφe/

Tu < 0.75, the maximum measured base shear is less than the total base shear of the eccentric structure. However, when

Tφe/

Tu ≥ 0.75, the total base shear of the eccentric structure decreases, and the maximum measured base shear of the structure increases beyond that of structures with the same lateral stiffness.

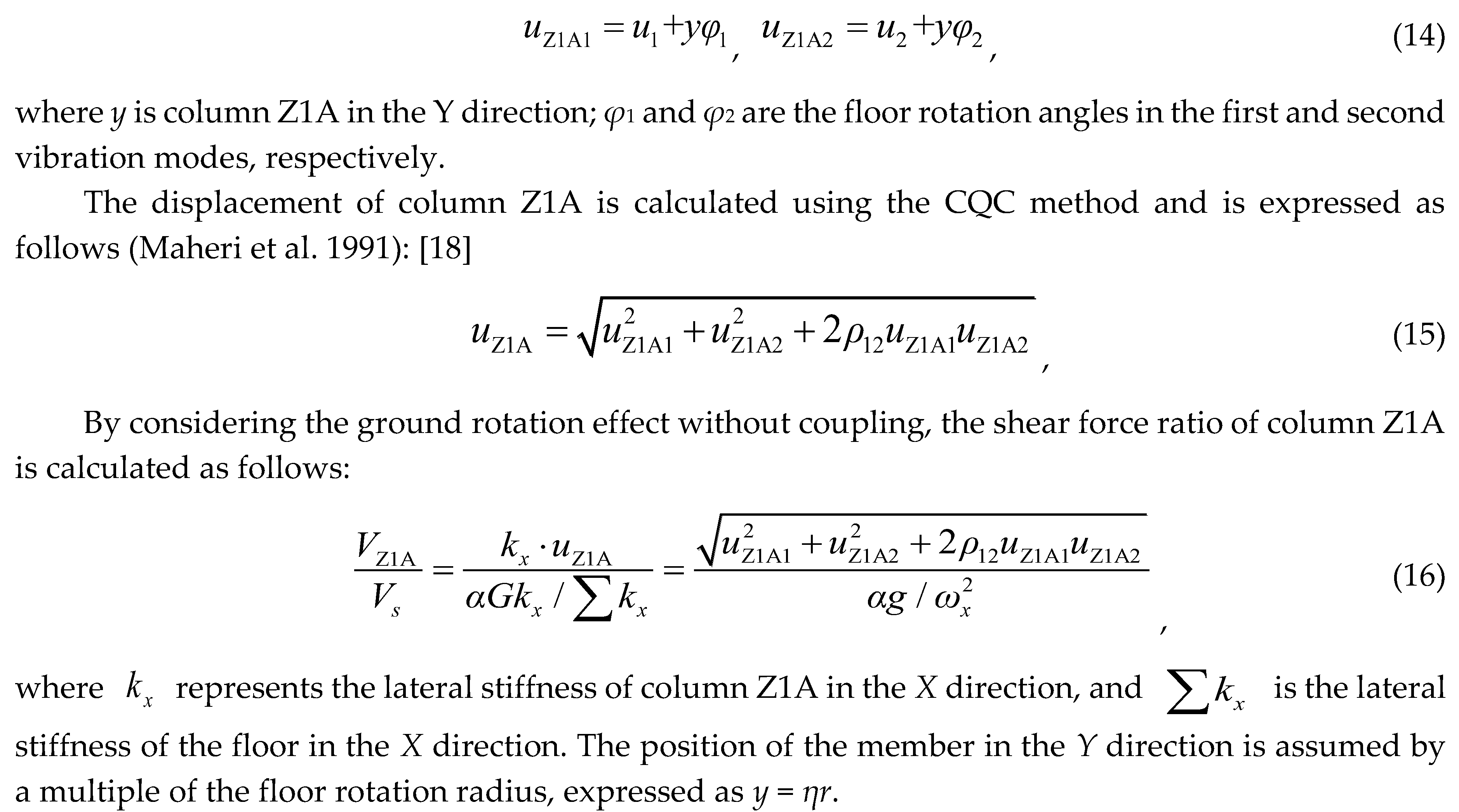

5.4. Comparison of Special-Shaped Column Shear Force

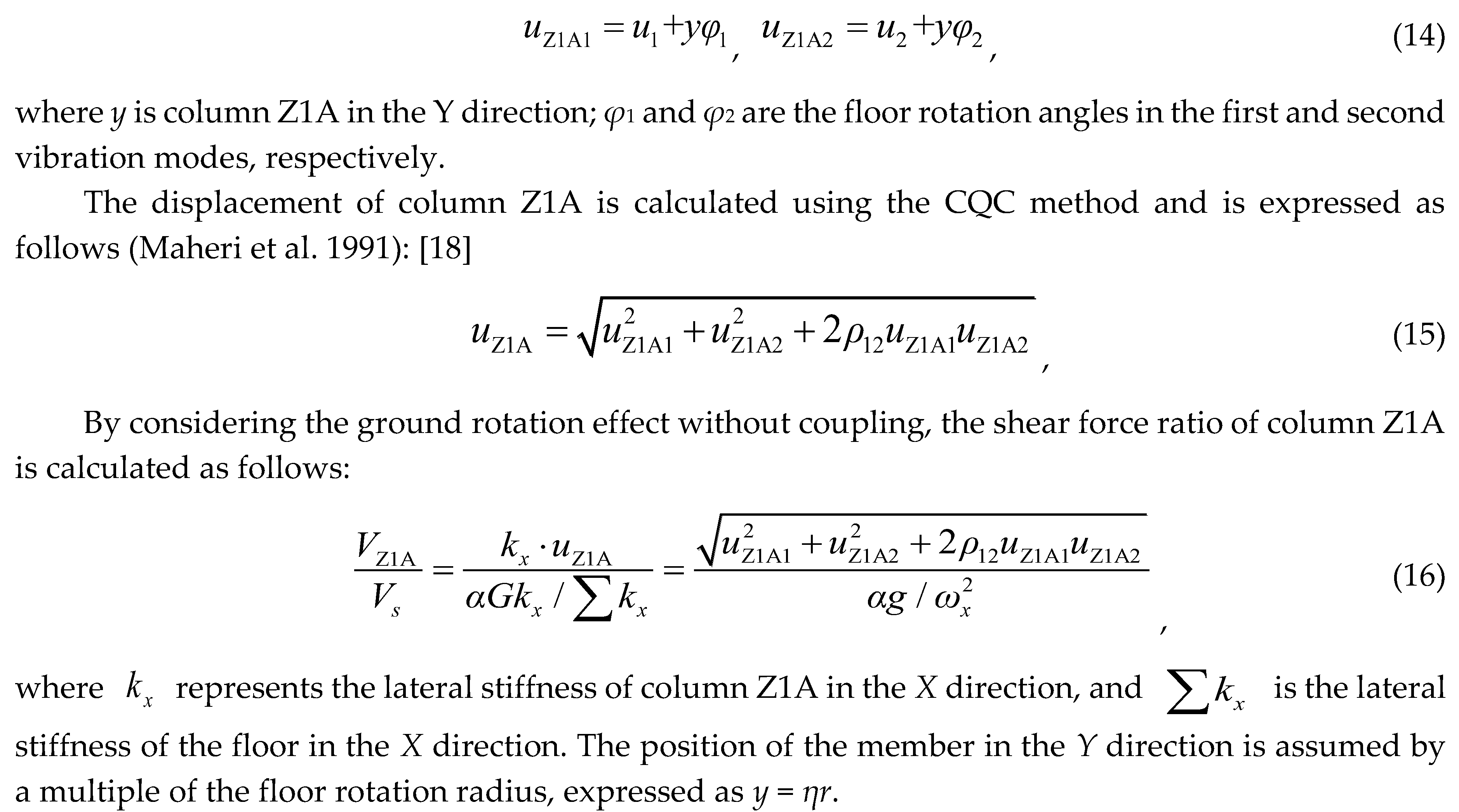

The displacements of column Z1A at the locations highlighted in

Figure 1 for the first and second vibration modes are expressed as follows:

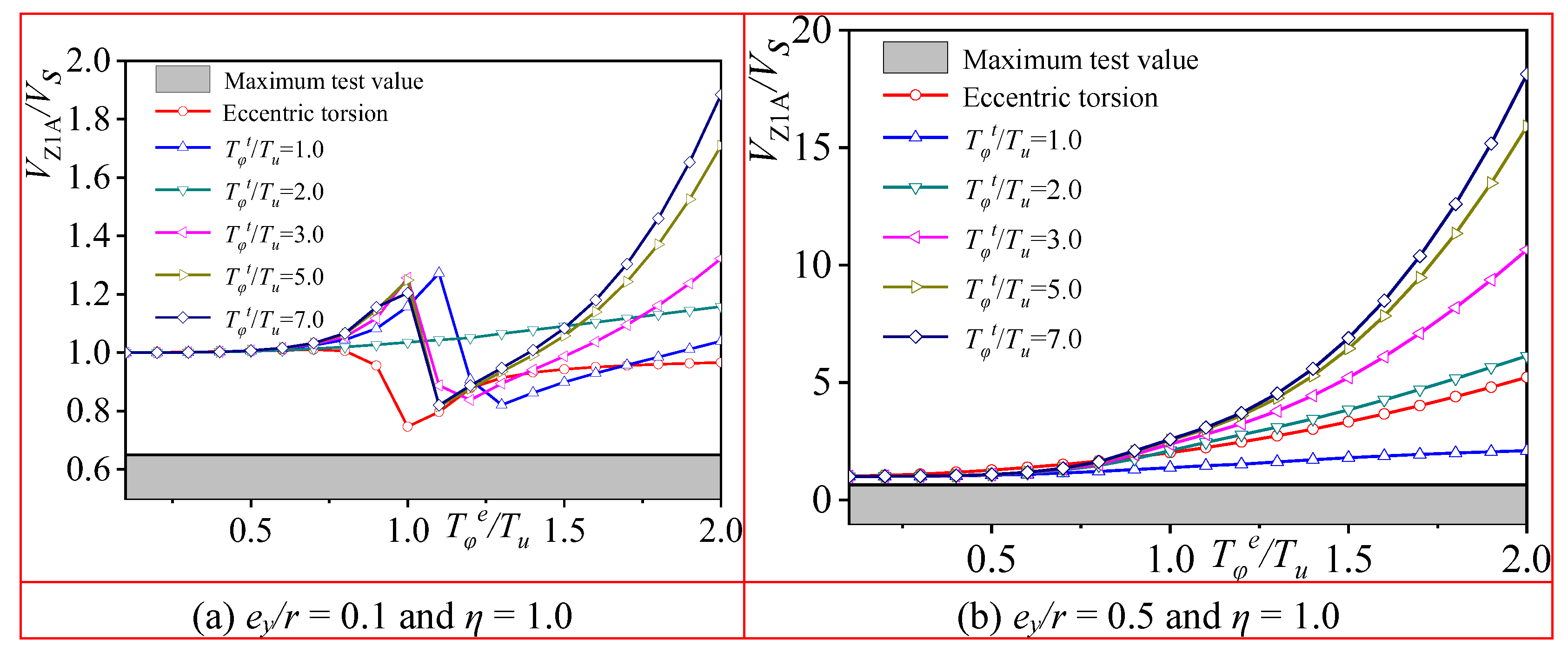

Figure 19 illustrates that the shear force ratio, considering ground rotation and without coupling, remains consistent when accounting for the influence of eccentricity. When the relative eccentricity

ey/

r is constant and the relative position of the column remains unchanged, a significant increase in the shear force of column Z1A is observed as

Tφt/

Tu increases to a value equal to or greater than 2.0, compared to the shear force when only considering the influence of eccentricity.

The shear force of the Z1A T-shaped columns during an earthquake is calculated as the ratio of the shear force to the theoretical shear force value of the corresponding position component, without considering coupling. This is expressed as follows (Kuang and Liu 2022) [

12]:

where

um is the maximum measured displacement at the top of the Z1A T-shaped column,

kx is the lateral stiffness of the Z1A T-shaped column in the

X direction, and Σ

kx is the lateral stiffness of the floor in the

X direction.

Figure 20 presents a comparison between the theoretical shear force and the maximum measured shear force of the Z1A column, while accounting for ground rotational components. The results indicate that the ratio of the maximum measured shear force of the Z1A T-shaped column under seismic action to the theoretical shear force, without considering coupling, is 0.65. It is observed that the maximum measured shear force value of the Z1A T-shaped column is lower than the shear force value when considering ground rotational components. This suggests that ground rotation has a significant amplification effect on the internal forces of the column components.

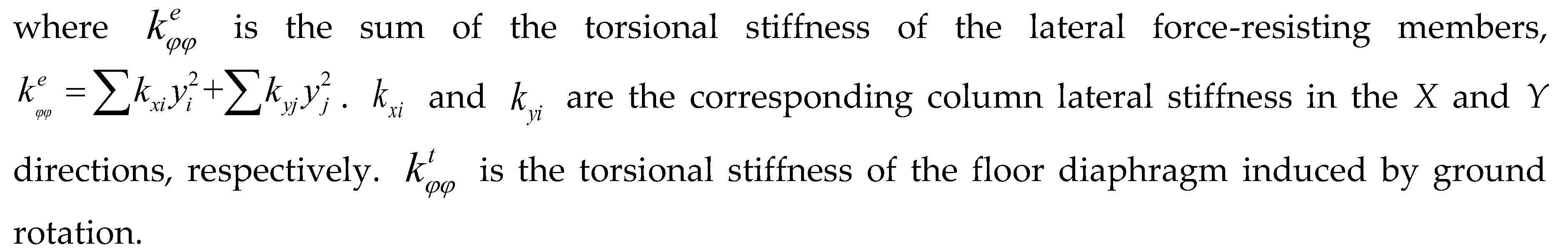

5.5. Comparison of Torsional Stiffness

The torsional stiffness equation is expressed as follows:

where

It is the polar moment of inertia of the column cross-section, and

G is the shear modulus of the material. The torque of each column under pure torsion is calculated as follows:

where

GIt is the torsional stiffness of the column,

φj is the twist angle of the column, and

hj is the column height.

Considering ground rotation, the torsional stiffness of each floor is expressed as follows:

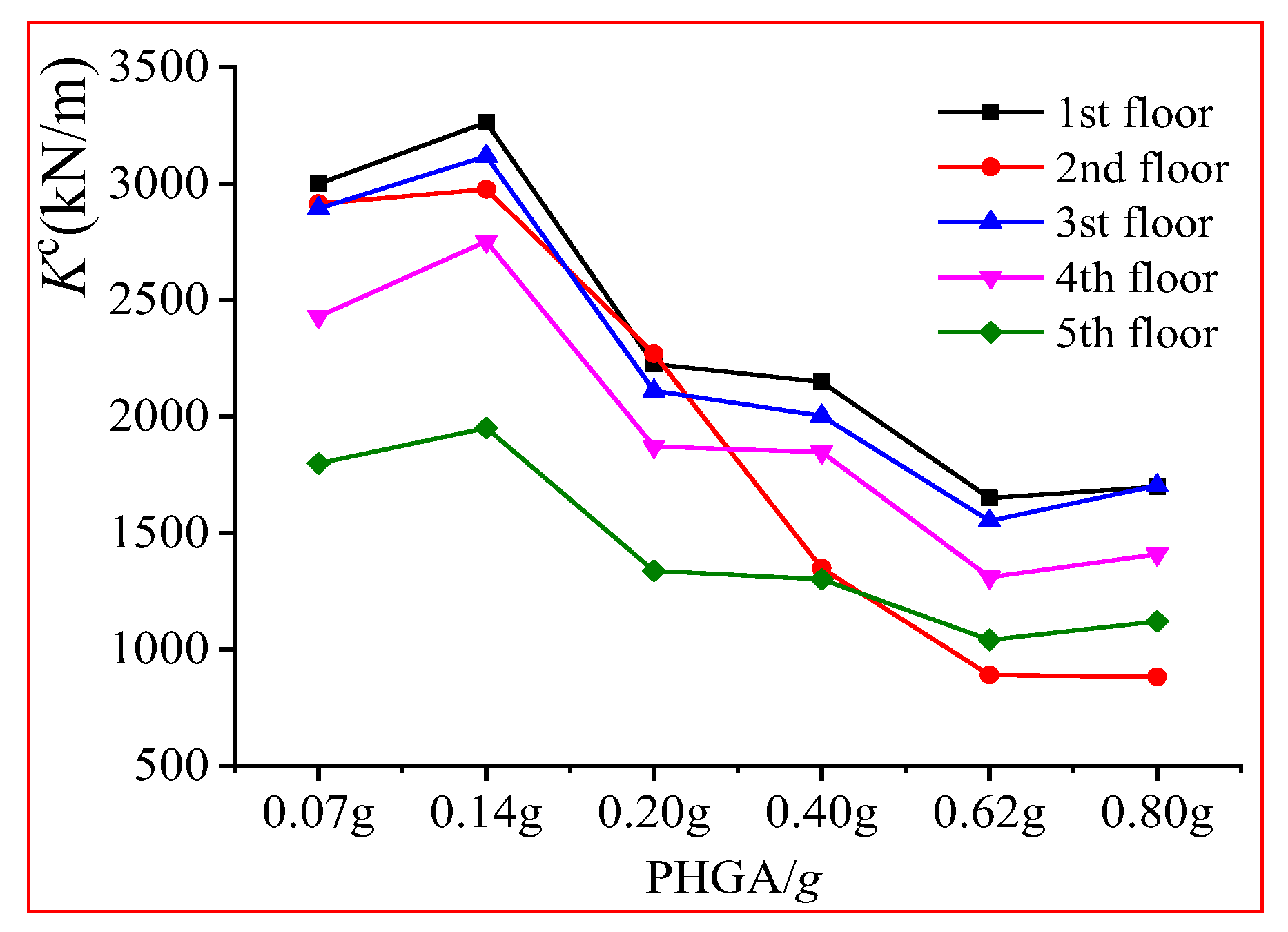

The ratio of the column shear force to the inter-story lateral displacement corresponds to the column lateral stiffness at the same level.

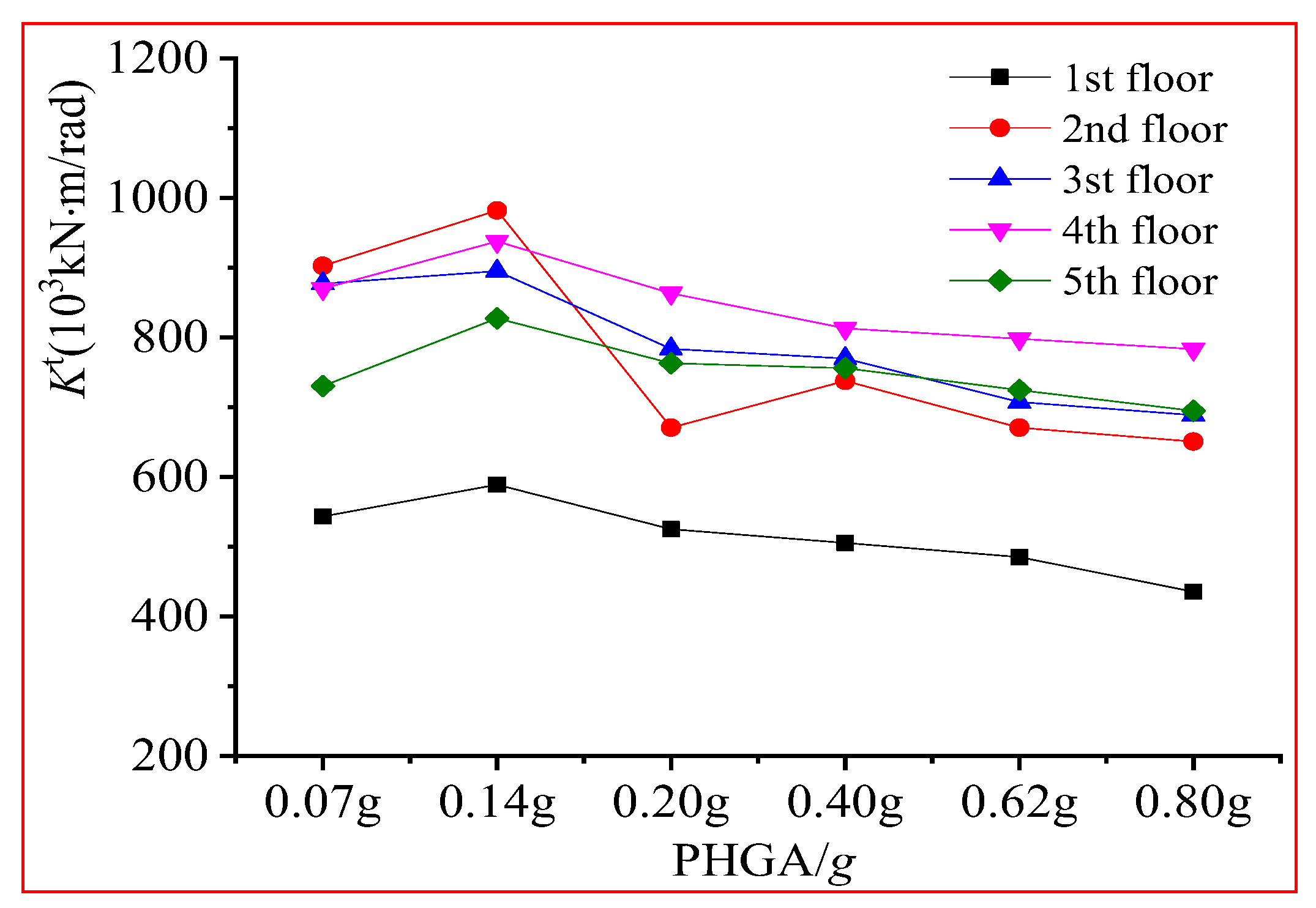

Figure 21 illustrates the maximum lateral stiffness variations for the ZA2 T-shaped columns under three seismic waves. The figure indicates that as peak acceleration increases, the inter-story displacement of the model continuously increases, while the column lateral stiffness gradually decreases. Specifically, the column lateral stiffness of the 2nd floor decreases rapidly, indicating significant stiffness degradation. The equivalent torsional stiffness of the model floors is determined according to Equation (30), and the analysis results are shown in

Figure 22. The figure reveals that under accidental torsion, the torsional deformation of the floor is relatively small, and the inter-story torsional displacement increases slowly. The degradation in each floor’s torsional stiffness is insignificant.

6. Conclusions

The establishment of a linear seismic response analysis model that considers ground rotation effects and eccentric torsion informed the investigation of the linear response characteristics of coupled lateral–torsional vibration, considering eccentricity and ground rotation. A comparative study of the coupled lateral–torsional vibration response pattern of SRC special-shaped column structures was conducted. The main conclusions obtained are as follows:

- (1)

Considering the influence of ground rotation and eccentric torsion on the model, the lateral displacement of the structure and floor torsion are primarily induced by horizontal seismic components and floor eccentricity. The seismic torsion of the model is attributed to ground rotational components. The floor torsional angle is equivalent to the sum of the inter-story and pure torsional angles caused by eccentric torsion and ground rotation, respectively.

- (2)

The natural vibration frequency of a structure, considering the influence of ground rotation, is a function of relative eccentricity ey/r, the lateral–torsional period ratio Tφt/Tu caused by ground rotation, and the lateral–torsional period ratio Tφe/Tu considering only eccentric torsion. The following conclusions are drawn from the variation analysis of the natural vibration frequency ratio, torsional amplitude ratio, mode participation factor ratio, and relative torsional index of the structure, considering the influence of ground rotation: when eccentricity ey/r is constant and Tφt/Tu remains unchanged, the peak points of the natural vibration frequency ratio and the lateral–torsional coupling coefficient, considering ground rotation, shift significantly compared to when considering only eccentricity under the same conditions. Once Tφe/Tu surpasses 1.0, the torsional amplitude increases remarkably, and the first vibration mode participation indicates elevated values compared to the scenario where only eccentricity is taken into account. When considering torsional dynamic effects, the accidental relative eccentricity of the SRC special-shaped structure in the Y-axis is less than 0.1.

- (3)

The shaking table test results facilitate the acquisition of the natural characteristics, translational response, torsional response, and internal force distribution of the SRC special-shaped column frame structure. Under intense earthquake conditions, the inter-story stiffness of the structure degrades rapidly. The maximum displacement angle of the structure is observed to be 1/14, the maximum accidental eccentric torsional angle is measured at 18.8×10-7, and the maximum inter-story displacement angle resulting from lateral-torsional coupling is recorded as 1/48. Throughout the experimentation, the torsional response of the SRC special-shaped column remains within the elastic stage. For the special-shaped column structure that meets the height limitation requirement specified in the code, the influence of accidental eccentricity and lateral-torsional coupling on its seismic performance is relatively minimal.

- (4)

By comparing experimental and theoretical values, the measured structural lateral–torsional natural frequency ratio considering ground rotation is close to the calculated results from the mathematical model. the maximum ratio of torsional displacement at the ground floor to the horizontal displacement in the X direction of the SRC special-shaped column frame structure under three-directional seismic action is 0.0007. The torsional effect, torsional stiffness, and internal force theoretical calculations of the special-shaped column correspond well to the experimental results, indicating that they can be used for analyzing lateral–torsional vibration response patterns of structures.

Author Contributions

All the authors listed have approved the manuscript that is enclosed.

Funding

The financial assistance was provided by the Shaanxi Province Natural Science Basic Research Project under Grant 2023-JC-YB-419, the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China under Grant 2020M683432, and the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 51308444.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included in this manuscript and its supporting information files.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance provided by the Shaanxi Province Natural Science Basic Research Project under Grant No. 2023-JC-YB-419, the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 2020M683432, and the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 51308444.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclosure: This work described was original research that has not been published previously, and not under consideration for publication else where, in whole or in part.

References

- Shetty, S. , Subrahmanya R.M., Bhandary S., et al. (2019), “Comparative study on seismic performance of specially shaped RC columns with that of rectangular columns in high-rise structures”, International Journal of Structural Integrity, 1 (2), 202-215.

- Patel, D.S. (2020), “Comparative Seismic Behaviour Study of Special Shaped Column Framed Reinforced Structure”, International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology, 8 (5), 714-719.

- Wu, H. (2013). “Seismic Capacity based on Special-shaped Columns Structure”, International Journal of Advancements in Computing Technology, 5 (9), 206-213.

- Zheng, Z. , Zhang, J., Miao, Y., Zhou, B., Huang, W., He, Y., Lu, Q., & Wang, Y. (2024), “Performance of T-shaped CFST columns with embedded T-shaped steel skeleton under axial compression”, Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 215, 108554-108554.

- Salah, A. , Elsanadedy, H., Abbas, H., Almusallam, T., & Al-Salloum, Y. (2022), “Behavior of axially loaded L-shaped RC columns strengthened using steel jacketing”, Journal of Building Engineering, 47, 103870-103870.

- Liu, Z. , Wang X., Zhou Z., et al. (2021), “Experimental and numerical study on seismic performance of steel reinforced concrete spatial frame with irregular section columns”, Engineering Structures, 242, 112507-112507.

- Zhang, X. , & Far, H. (2021). “Effects of dynamic soil-structure interaction on seismic behaviour of high-rise buildings”, Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 20 (7), 3443-3467.

- Li, X. , Liu, J., Wang, X., & Chen, Y. F. (2023). “Test and design of eccentrically-loaded slender circular tubed columns filled with high-strength concrete and reinforcement,” Structures, 51, 1461-1473.

- Sunagar, P. , gowda, R., Nayak, S., & Sumalatha, J. (2021), “Seismic vulnerability and resilience of steel-reinforced concrete (SRC) and composite Structures”, Design Engineering, 11455-11469.

- Wang, L. , Zhou, Y., Nagarajaiah, S., & Shi, W. (2023), “Bi-directional semi-active tuned mass damper for torsional asymmetric structural seismic response control”, Engineering Structures, 294, 116744-116744.

- Ismail, M. (2020), “New approach to seismic-resistant design and structural torsion mitigation”, Engineering Structures, 207, 110092-110092.

- Kuang, Y. , & Liu, Y. (2022). “Parametric analysis of the whole loading process of translation-torsion coupled vibration characteristics of the multi-layer bi-directional eccentric frame structure”, Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, 479-494.

- Hao, H. (1997), “Torsional response of building structures to spatial random ground excitations”, Engineering Structures, 19 (2), 105-112.

- Lai, X. , & He, Z. (2022), “A generalized hybrid model considering earthquake-induced internal force distribution rules for super high-rise frame-core tube structures”, Engineering Structures, 268, 114745-114745.

- Wen, J. , Xiong, H., Bu, G., Xu, C., Chen, K., & Wen, J. (2024), “Seismic fragility of vertically irregular gravity column-core tube structure subjected to pulse-like ground motions”, Structures, 62, 106217-106217.

- Mao, H. , Yan X., Wei X., et al. (2022), “Seismic analysis of a frame structure equipped with displacement-amplified torsional dampers”, Structures, 41, 190-202.

- Alam, Z. , Sun, L., Zhang, C., & Noroozinejad Farsangi, E. (2023), “Global performance of multi-story stiffness-eccentric RC structures subjected to progressive seismic excitations: Shaking table investigations”, Journal of Building Engineering, 64, 105582-105582.

- Maheri, M. R. , Chandler, A. M., & Bassett, R. H. (1991), “Coupled lateral-torsional behaviour of frame structures under earthquake loading”, Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics, 20 (1), 61-85.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. (2016), “Code for seismic design of buildings (GB 50011-2010)” [S]. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, 2016.

Figure 1.

Dynamic model of single-story eccentric structure.

Figure 1.

Dynamic model of single-story eccentric structure.

Figure 2.

Sketch of inter-story torsion.

Figure 2.

Sketch of inter-story torsion.

Figure 3.

Natural vibration frequency ratio of structure.

Figure 3.

Natural vibration frequency ratio of structure.

Figure 4.

Variation pattern of torsional amplitude.

Figure 4.

Variation pattern of torsional amplitude.

Figure 5.

Participation degree of vibration mode.

Figure 5.

Participation degree of vibration mode.

Figure 6.

Relationship among φr/u, ey, Tφe/Tu, and Tφt/Tu.

Figure 6.

Relationship among φr/u, ey, Tφe/Tu, and Tφt/Tu.

Figure 7.

Torsional displacement ratio α.

Figure 7.

Torsional displacement ratio α.

Figure 9.

Vibration characteristics.

Figure 9.

Vibration characteristics.

Figure 10.

Distribution of inter-storey displacement.

Figure 10.

Distribution of inter-storey displacement.

Figure 11.

Torsion angle.

Figure 11.

Torsion angle.

Figure 12.

Distribution of maximum inter-storey shear force.

Figure 12.

Distribution of maximum inter-storey shear force.

Figure 13.

Shear force of ZA2 T-shaped column.

Figure 13.

Shear force of ZA2 T-shaped column.

Figure 14.

Torsional stiffness of the ZA2 T-shaped column.

Figure 14.

Torsional stiffness of the ZA2 T-shaped column.

Figure 15.

Natural frequency ratio considering ground rotation.

Figure 15.

Natural frequency ratio considering ground rotation.

Figure 16.

Comparison between theoretical torsional effect and experimental value of lateral–torsional coupling in Y direction.

Figure 16.

Comparison between theoretical torsional effect and experimental value of lateral–torsional coupling in Y direction.

Figure 17.

Comparison between theoretical torsional effect and experimental value considering ground rotation.

Figure 17.

Comparison between theoretical torsional effect and experimental value considering ground rotation.

Figure 18.

Comparison between base shear theoretical and test values considering ground rotational components.

Figure 18.

Comparison between base shear theoretical and test values considering ground rotational components.

Figure 19.

Z1A column shear force.

Figure 19.

Z1A column shear force.

Figure 20.

Comparison between theoretical and test values of Z1A column shear force.

Figure 20.

Comparison between theoretical and test values of Z1A column shear force.

Figure 21.

Lateral stiffness of T-shaped column.

Figure 21.

Lateral stiffness of T-shaped column.

Figure 22.

Torsional stiffness of the model.

Figure 22.

Torsional stiffness of the model.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).