Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Climate Hazards for Dam & Reservoir Systems

2.3. Components of Dam & Reservoir Systems and their Typologization

2.4. Potential Climate Change Impacts of Dam & Reservoir Systems and their Typologization

2.4.1. Potential impacts Due to Mean Air Temperature Increase and Extreme Heat

2.4.2. Potential Impacts Due to mean Precipitation Decrease, Aridity and Droughts

2.4.3. Potential Impacts Due to Extreme Precipitation and Flooding

2.4.4. Potential Impacts Due to Strong Winds

2.5. Climate Indicators for Dam & Reservoir Systems

- average (TMm), maximum (TXm) and minimum (TNm) values of temperature (oC) for years, seasons (summer and winter) and months,

- longest heat wave in days, e.g. heatwave duration (HWD) and tropical days per year, e.g. the number of summer days (SU) with TX>25oC,

- year-on-year cooling and heating degree days, e.g. heating degree days (HDD) and cooling degree days (CD),

- beginning, end and duration of the growing season and vegetation growth rates, e.g. growing season length (GSL) and growing degree days (GDD),

- diurnal and seasonal amplitudes, e.g. daily temperature range (DTR) that is the monthly mean difference between TX and TN,

- number of days with frost, cold, zero pass-through, high summer heat and tropical heat, e.g. number of icing days (ID) that is the annual count of days when TX (daily maximum temperature) <0°C, the number of frost days (FD) that is the annual count of days when TN (daily minimum temperature) <0°C, the hot days that is the number of days with TX > 35oC, and the tropical nights (TR) that is the number of days with TN>20oC,

- evaporation and effective precipitation,

- if precipitation falls as rain or snow,

- extent, duration, strength and water content of snow cover,

- the start of the spring flood, the length and depth of the frost period,

- the start of icing, ice thickness and duration of ice cover, and

- the water temperature in streams and reservoirs (WTLS).

- standard precipitation index in 3, 6 and 12 months (SPI-3, SPI-6 and SPI-12),

- standardized streamflow index (SSI),

- longest dry spell in days, e.g. consecutive dry days (CDD),

- average, maximum and minimum values for years, seasons, 14 days, and weeks, e.g. annual total precipitation on wet days (PRCPTOT),

- annual and seasonal precipitation change relative to the baseline period,

- average, minimum and maximum values of river flows for years, seasons, months, 14 days and weeks e.g. river discharge index (RID) that is defined as the annual mean daily river discharge, and

- drought with return period T=100 y.

- number of days with heavy and extreme precipitation, e.g. number of days with precipitation >10 mm (R10mm) and with precipitation > 20 mm (R20mm),

- extreme precipitation, e.g. extreme precipitation total index (R95pTOT), which is the total sum in a year of daily precipitation values exceeding the 95th percentile of the reference period (mm),

- maximum daily rainfall, e.g. maximum 1 day precipitation (Rx1day),

- number of 24-hour extreme precipitation events that occur once in 20 or 50 years, e.g. one in 20year return value of maximum one day precipitation (20Rx1day),

- number of days with one-hour total rainfall greater than 10 mm, with 24-hour total rainfall greater than 25 mm (e.g. R25mm), or with 48-hour total rainfall greater than 50 mm,

- frequency Haldo-rain, e.g. 1 day precipitation>120 mm,

- mean winter wettest day precipitation,

- downpours and extreme rainfall volumes,

- rainfall – storm return period,

- average effective rainfall, e.g. effective precipitation (EP),

- average, minimum and maximum values of river flows for years, seasons, months, 14 days and weeks e.g. river discharge index (RID) that is defined as the annual mean daily river discharge,

- frequency 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 30 days of discharge for T = 50 - 10000 years recurrence interval,

- high water events today and in the future,

- average and annual high snow water content (measured or calculated),

- percentage of filling of reservoirs,

- soil moisture, surface runoff,

- start of spring flood,

- river runoff, e.g. river flood index is the 50-year flood recurrence value based on maximum river discharge,

- probable maximum flow (PMF) and regionalized change factors (including upper and lower end estimates) for the 1 in 50-year return period flow,

- change of periods of recurrence of Inflow Design Flood (IDF) from T=100 years to PMF, and

- flood with return period T=100 years e.g. river flood index using runoff accounts for extreme water discharge as it reports the value of daily river flow corresponding to a return period of 100 years.

- mean wind speed, and

- extreme wind speed

2.6. Typologization of Climate Change Impacts on Dam & Reservoir Systems

2.7. The Case Study

3. Application of the Methodology

3.1. Description of the Almopeos Dam & Reservoir System

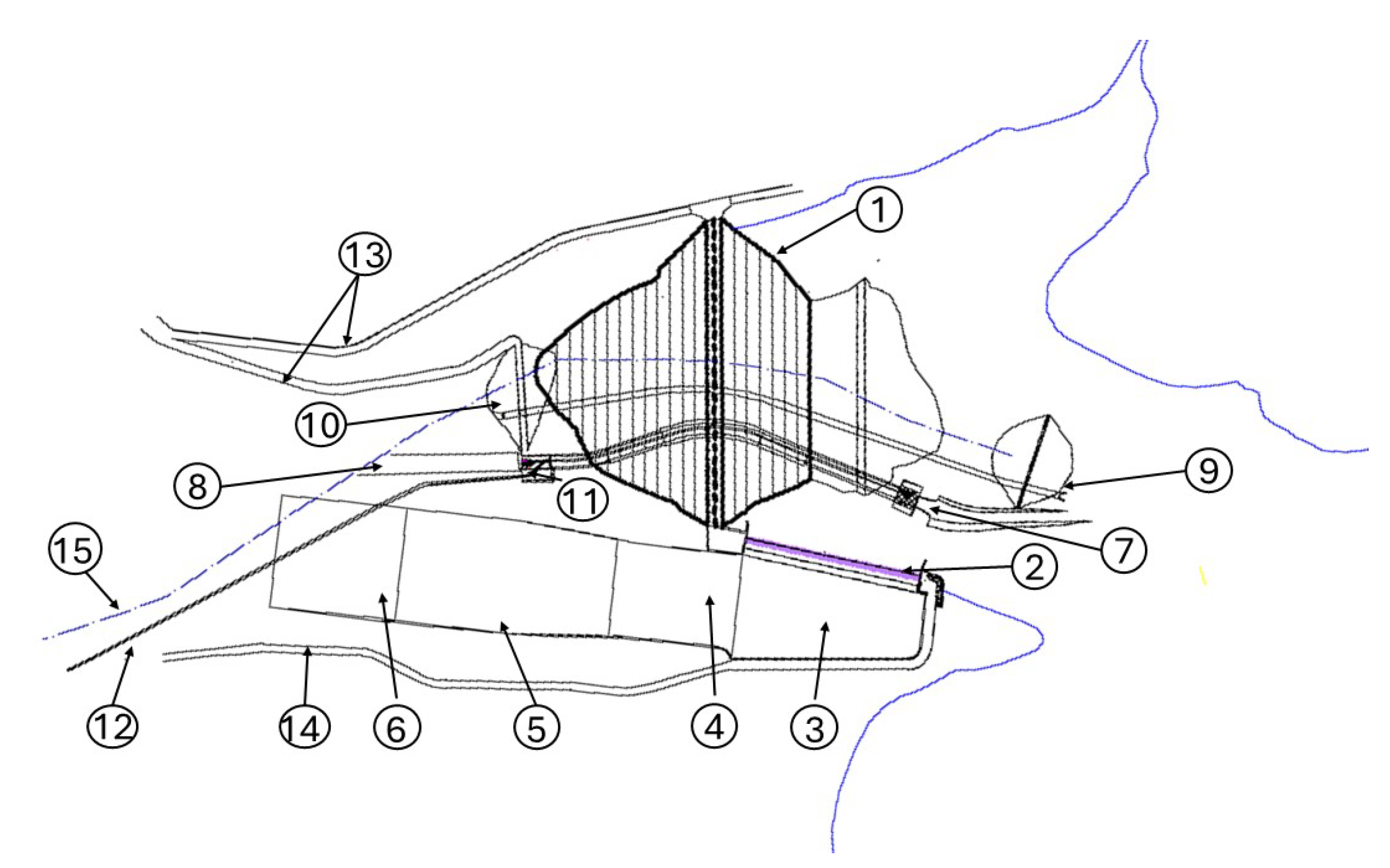

3.1.1. Components of the Almopeos Dam & Reservoir System

- Inflow (I). The inflow to the system is the water from Almopeos River; according to the River Basin Management Plan of Western Macedonia [61], its ecological status immediately upstream of the dam is good, but its chemical status is lower than good.

- Processes (P). The water of the reservoir will be used for irrigation (P1). For safety reasons and to reduce the pollution of the water of the reservoir, deforestation and clearing, cutting of bushes and trees and their removal will be performed prior to the construction of the reservoir.

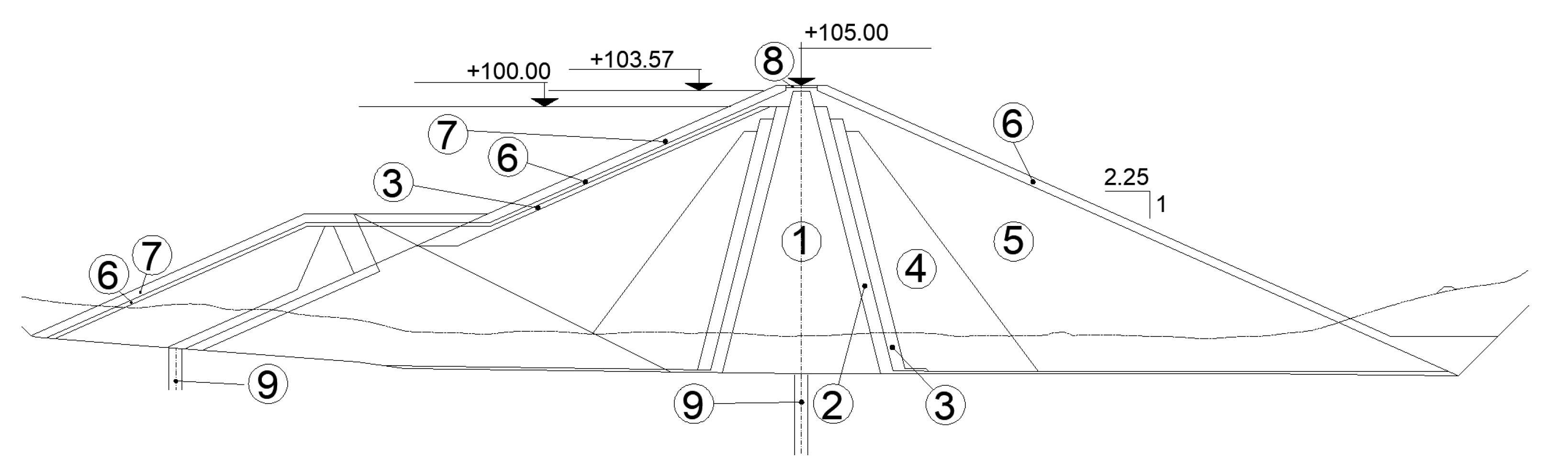

- Earthfill dam (A1). The dam will be constructed with an impervious clay core and nearby soil will be used for its layers. Rockfall (riprap) is employed on dam’s faces for its protection against wave action and erosion. Therefore, there is no vegetation on dam faces and only unwanted vegetation can grow between the riprap voids. Moreover, there are no liners and joint materials on the dam.

- Spillway (A2). The components of the spillway system are the following: (1) the inflow channel, (2) the spillway with 21 fusegates to increase reservoir storage capacity and/or to increase spillway discharge capacity, (3) the collector channel, (4) the drop channel, (5) the stilling basin, and (6) the escape channel that ends in the downstream river. All channels are made by reinforced concrete except for the escape channel that is made by excavated natural soil partly protected with stones. The fusegates are made of steel and are sealed with EDPM; each fusegate is 6.75 m long and 2.0 m high.

- Auxiliary structures (A3). The main auxiliary structures of the Almopeos D&R system are the following: (1) vertical concrete well for discharge and irrigation supply, (2) pipelines for (i) discharge (steel pipe Ø1500, contraction to Ø1200, 2 butterfly control valves Ø1200, and Howell – Bunger valve Ø800 for flow regulation), (ii) irrigation (steel pipe Ø1500, Ø1200 control valve and a flow meter), (iii) environmental flow (steel pipe Ø500, Ø500 control valve and a flow meter), and (iv) sediment flushing (metal pipe Ø2500 encased in concrete, high-pressure gate for downstream control). Sediment flushing is performed after the end of the irrigation season and in the first rain of the winter.

- Buildings (A4). The administration building is an underground structure by reinforced concrete with internal dimensions 19.0m X 8.40 m. In this building the automation and remote-control system will be installed together with (1) the majority of the control devices and parts of the pipelines (see A3), (2) the required supporting infrastructure (see S) for the permanent work of the personnel, such as water supply, drainage, HVAC, telephone, data, internet, other electrical installations, and (3) a bridge crane.

- Outflow (O). The environmental flow ranges from 0.04 to 1.1 m3/s (O3).

- Supporting infrastructure (S). Power supply is used for the operation of the bridge crane, the lights, and the auxiliary equipment in the administration building and the monitoring (S1). Flow is controlled by four control valves, a Howell – Bunger valve, two electromagnetic flow meters and a high-pressure gate. Monitoring is performed (i) for leakage, seepage and pore water pressure via hydraulic, electrical and pneumatic piezometers, (ii) settlement and deformation in the interior of the dam via vertical tube extensometers and inclinometers, and (iii) force feedback digital accelerometers. The project site is assessed via two existing rural roads. The first road starts from the settlement of Kali and runs along the left (eastern) bank of Almopeos River, along which the water supply pipe to the irrigation networks, while the second road starts from the settlement of Profitis Ilias and runs along the right (west) bank of the river (see Fig.1). There are no permanent staff on the site of the project, but there will be regular visits from personnel for operation and maintenance purposes.

3.1.2. Potential Climate Hazards and Impacts on the Components of the Almopeos Dam & Reservoir System

- Impacts due to mean air temperature increase and extreme heat - heat waves.

- 2.

- Impacts due to mean precipitation decrease, aridity and droughts.

- 3.

- Impacts due to extreme precipitation and river flooding.

| Groups of components | Temperature increase and extreme heat (HC1 &HC2) |

Precipitation decrease, aridity and droughts (WD1, WD4 & WD5) |

Extreme precipitation and flooding (WD2 & WD3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I Inflows |

Increased river water temperature; degraded water quality (Τ-Ι). |

Reduced flow rates; degraded water quality (D-Ι). | Increased flow rates, sediment loads and debris; mobilized vegetation; degraded water quality (F-I). |

| P Storage |

Increased water temperature; increased stratification; degraded water quality; impacts on fish (T-P1). | Reduced reservoir volumes; reduced water levels; exposure of parts of the dam; degraded water quality; reduced irrigation water potential (D-P1). | Increased water levels; increased sediments, debris, mobilized vegetation and turbidity; degraded water quality; reduced water storage volume due to increased volumes of sediments (F-P1). Increased risk of flooding, overtopping and downstream flooding (F-P2). |

| A Assets |

Desiccation and shrinking of clay core (T-A1); expansion cracking of concrete spillway (T-A2); cracking of concrete spillway channels (T-A3); increased power demand for cooling and reduced lifespan of building components (T-A4). |

Desiccation and shrinking of clay core (D-A1). | Increased pore pressure; increased risks for piping, overtopping, seepage and erosion (F-A1); increased risk of spillway failure due to increased flow rates, flow velocities and water levels (F-A2); damage of dam components due to debris (F-A3); damp and mold, inundation and electricity supply outage in the administration building (F-A4). |

| Outflows (O) | Increased water irrigation demand during hotter summers (T-O1); degraded water quality downstream of the reservoir and impacts on fish; conflicts in water withdrawals for environmental flow (T-O3). | Increased demand for irrigation water during hotter summers (D-O1); demand for increased environmental flow, reduced availability for flushing during summer, and management conflicts (D-O3). | Impacts to downstream watercourses due to flooding, overtopping, piping and pollution (F-O3). |

| Supporting infrastructure (S) | Increased risk of damage of access roads (T-S3); increased maintenance difficulty and requirements (T-S4). |

More difficult working conditions and maintenance (D-S4). | Increased risk of electrical failure (F-S1); increased damaged access roads (F-S3); more hampered communications (F-S2); more difficult working conditions and maintenance (F-S4). |

3.1.3. Climate Indicators for the Almopeos Dam & Reservoir System

| Climate hazard | Indicator | Symbol | Medium Exposure Thresholds (Δ from 1981-2000 Baseline) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HC1 & HC2 | Annual mean daily minimum temperature (oC) | TNm | 1≤Δ<2 [63] |

| Annual mean daily maximum temperature (oC) | TXm | 1≤Δ<2 [63] | |

| Hot days: annual count of days with daily maximum temperature >30oC |

HD | 10≤Δ<20 [63] | |

| Annual count of days with daily maximum temperature >35oC | TX35 | 10≤Δ<20 [63] | |

| Tropical nights: annual count of days with daily minimum temperature >20oC | TR | 20≤Δ<30 [63] | |

| WD1, WD4 & WD5 | Annual total precipitation on wet days (mm) | PRCPTOT | -10≤Δ<-5 [63] -25%≤P<-10% [44,46] 566-835 [64] |

| Consecutive Dry Days: maximum number of consecutive days with daily precipitation less than 1 mm in a year | CDD | 10≤Δ<20 [63] 11-20 [65]; 31-50 [66]; 40-60 [44,46] |

|

| WD2 & WD3 | Annual count of days when precipitation is ≥ 20 mm | R20mm | 1≤Δ<3 [63] |

| Annual maximum one-day precipitation (mm) | Rx1day | 5≤Δ<10 [63] 10.1-25.0 [66]; 7.6-35.5[67]; 10-35.5[68]; 20-50 [69] |

3.2. Climate Change Impact Assessment

3.3. Vulnerability Assessment

3.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis

- The components that show the highest sensitivity, ranging from medium to high, are the input (i.e. the river water, I1), the storage (P2), the assets, i.e. the dam (A1) and the spillway (A2), and the outflow (i.e. water for irrigation, O1). These components show medium to high sensitivity to WD2 & WD3 and WD1, WD4 & WD5 and medium sensitivity to HC1 & HC2.

- The components that show low to medium sensitivity are the building (A4) and the water release (O3), while all components of the group of supporting infrastructure (S1 to S4) are practically insensitive to WD1, WD4 & WD5.

- The highest score of all groups of components for each group of hazards are medium for HC1 & HC2, and high for WD2 & WD3 and WD1, WD4 & WD5.

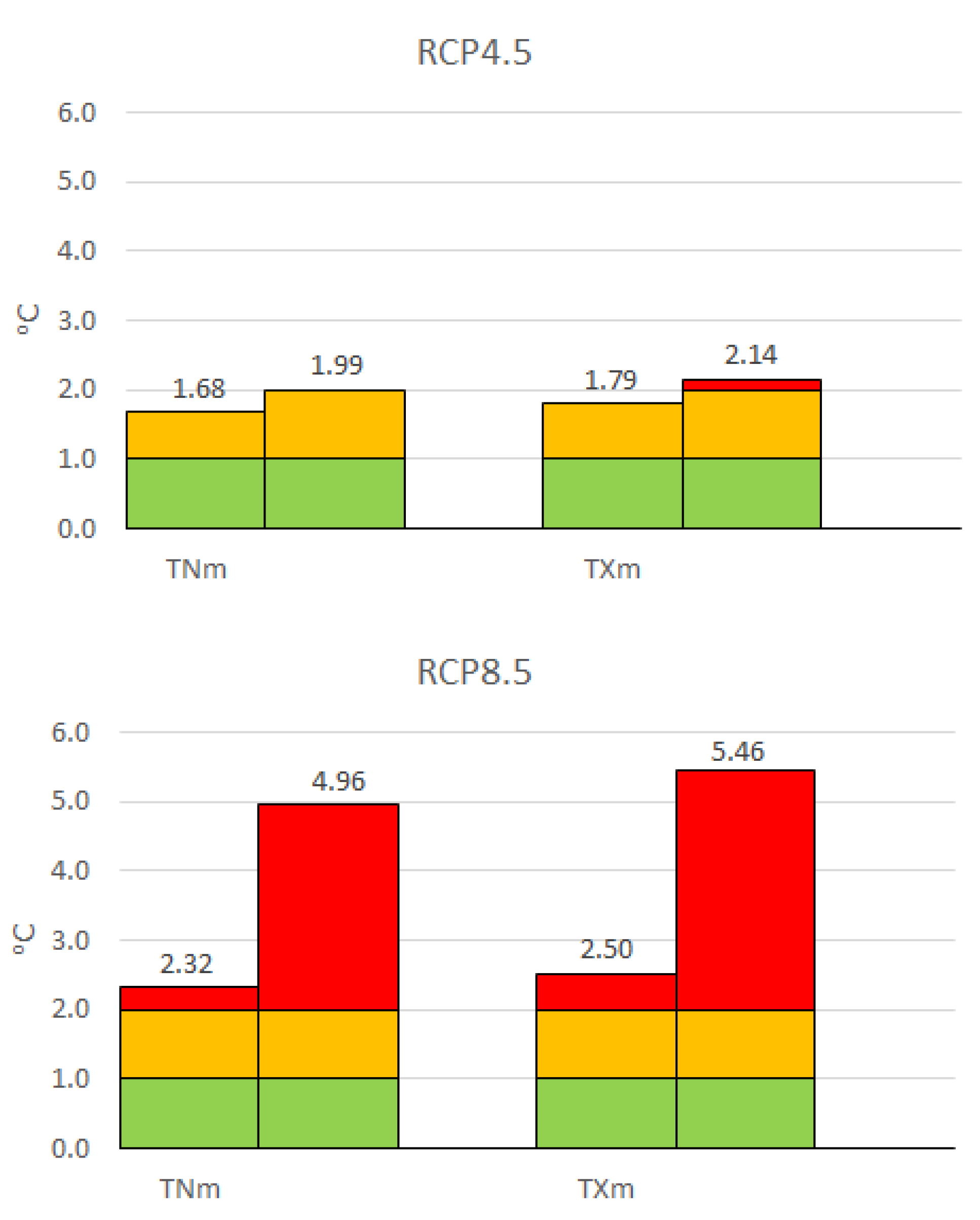

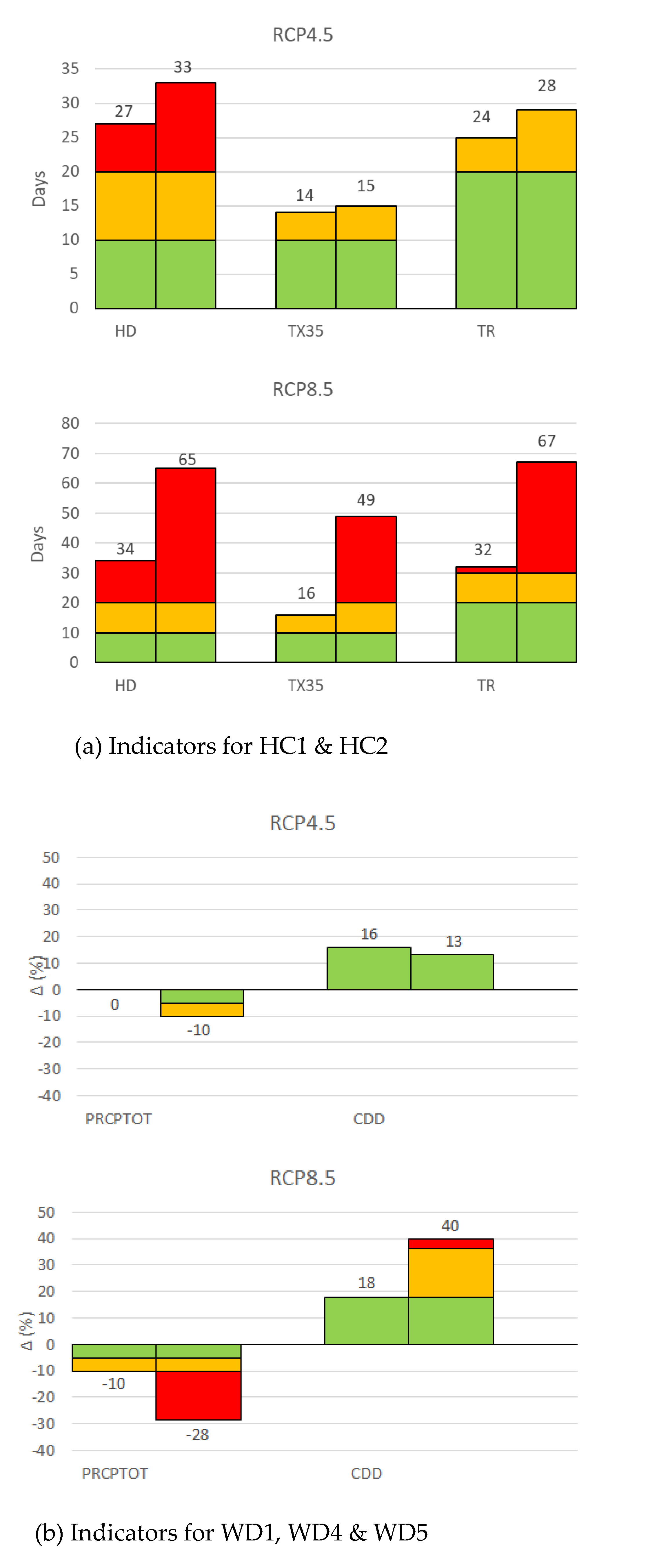

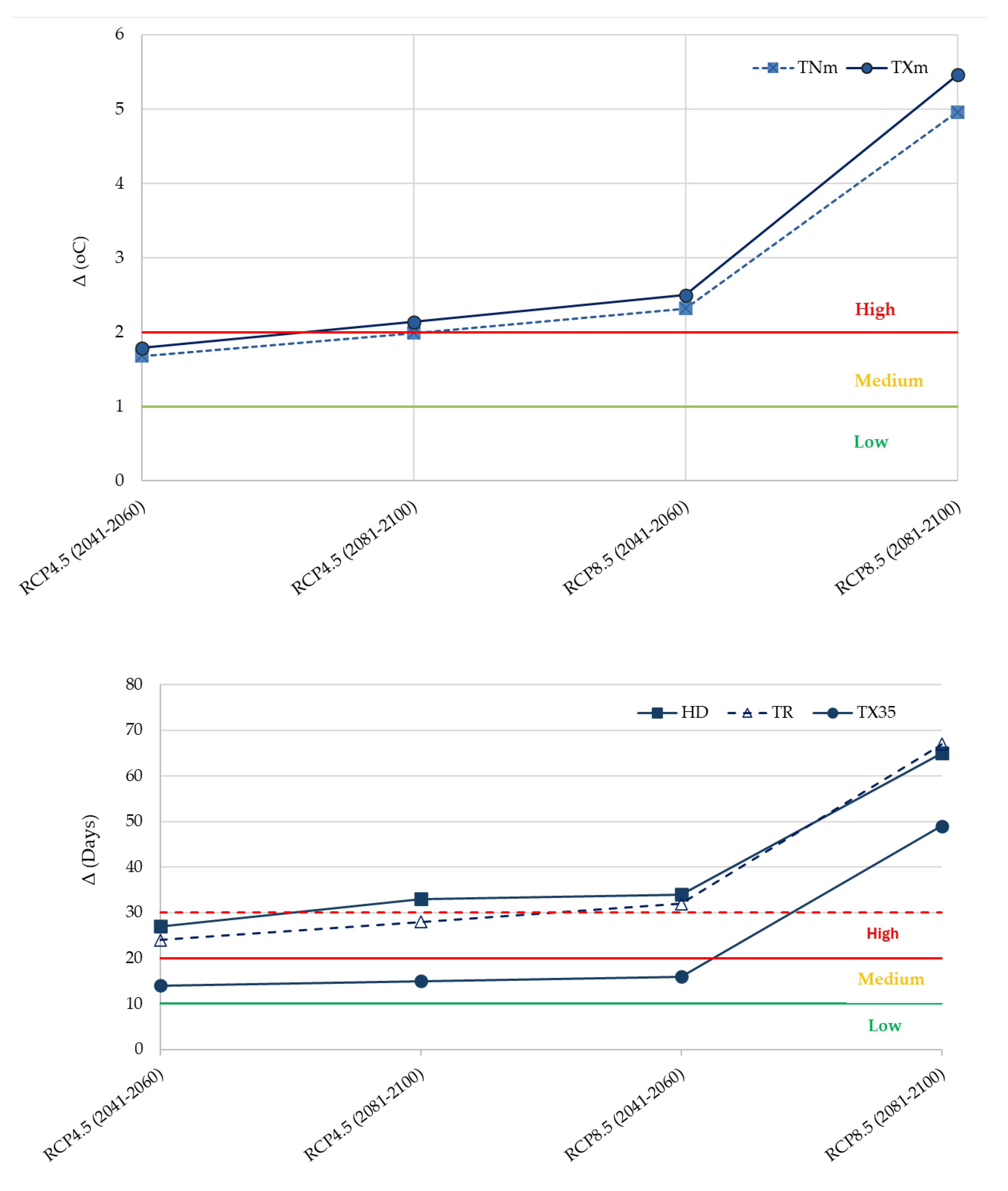

3.3.2. Exposure Analysis

- For group hazards HC1 & HC2 the scenario RCP8.5 shows high exposure in both periods, while the scenario RCP4.5 shows a medium exposure in the first period (2041-2060) that becomes high in the second period (2081-2100).

- For group hazards WD1, WD4 & WD5 the exposure for the scenario RCP8.5 is medium in the first period and high in the second period, while the exposure is low in both periods of scenario RCP4.5.

- For group hazards WD2 & WD3 both scenarios RCP8.5 and RCP4.5 show high exposure in the first period, while in the second period exposure is reduced to medium.

3.3.3. Vulnerability Analysis

- For group hazards HC1 & HC2 the scenario RCP8.5 shows the same scores in both periods; all groups are highly vulnerable to HC1 & HC2. However, in the scenario RCP4.5 all groups show a medium vulnerability in the first period (2041-2060) that becomes high in the second period (2081-2100).

- For group hazards WD1, WD4 & WD5, the vulnerability of the scenario RCP8.5 ranges from medium to low in the first period (2041-2060); however, these scores increase in the second period (2081-2100) and range from medium to high. In both periods of RCP4.5 all groups show low to medium vulnerability. The components that show the minimum vulnerability are auxiliaries (A3) and buildings (A4) from the group of assets and practically all the components of the group supplementary infrastructure (S).

- For group hazards WD2 & WD3 both scenarios RCP8.5 and RCP4.5 show high vulnerability in both periods for all groups, except for the group of the supplementary infrastructure (S), whose vulnerability is reduced to medium in the second period (2081-2100).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Sensitivity Analysis as a Preliminary Impact Analysis

4.2. Effect of the Use of Other Climate Indicators

4.3. Research Needs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A State-of-the-Art Global Reanalysis Dataset for Land Applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of state - Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) Dams 101 Available online:. Available online: https://damsafety.org/dams101 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Association of state - Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) Dam Failures and Incidents Available online:. Available online: https://damsafety.org/dam-failures (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Brunner, G.W. HEC-RAS, River Analysis System Hydraulic Reference Manual,Causes and Types of Dam Failures; Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC), 2016;

- Association of state - Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) Earth Dam Failures Available online:. Available online: https://damsafety.org/dam-owners/earth-dam-failures (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services (NHDES) Environmental Fact Sheet - Typical Failure Modes of Embankment Dams; NHDES Dam Bureau, 2020;

- Association of state - Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) Concrete Gravity Dam Failures Available online:. Available online: https://damsafety.org/dam-owners/concrete-gravity-dam-failures (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Almog, E.; Kelham, P.; King, R. Modes of Dam Failure and Monitoring and Measuring Techniques; UK, 2011;

- Atkins Impact of Climate Change on Dams & Reservoirs; Atkins: London, UK, 2013.

- Fluixá-Sanmartín, J.; Morales-Torres, A.; Escuder-Bueno, I.; Paredes-Arquiola, J. Quantification of Climate Change Impact on Dam Failure Risk under Hydrological Scenarios: A Case Study from a Spanish Dam. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 2117–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margottini, C.; Canuti, P.; Sassa, K. Landslide Science and Practice: Volume 4: Global Environmental Change; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; ISBN 978-3-642-31336-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A.K.; Hunt, D. A Guide to the Effects of Climate Change in Dams; The British Dam Society, 2012.

- Menk, L.; Terzi, S.; Zebisch, M.; Rome, E.; Lückerath, D.; Milde, K.; Kienberger, S. Climate Change Impact Chains: A Review of Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities for Climate Risk and Vulnerability Assessments. Weather, Climate, and Society 2022, 14, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.; Wei, Y.-M.; De La Vega Navarro, A.; Garg, A.; Hahmann, A.N.; Khennas, S.; Azevedo, I.M.L.; Löschel, A.; Singh, A.K.; Steg, L.; et al. Energy Systems. In Climate Change 2022 - Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Al Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al.,; Cambridge University Press: UK, 2023; pp. 613–746.

- Stamou, A. Hydro-Environment Research on Climate Change Adaptation of Water Infrastructure (WI). In Proceedings of the 8th IAHR Europe Congress; IAHR: Lisbon, Portugal, June 4 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stamou, A.I. The Typologization of Water Research as a Possible Means to Improve the Technical Guidelines on the Adaptation of Water Infrastructure to Climate Change. Hydrolink 2024, 3, 04–08. [Google Scholar]

- Stamou, A.I.; Mitsopoulos, G.; Sfetsos, A.; Stamou, A.T.; Varotsos, K.V.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Koutroulis, A. Typologizing the Hydro-Environmental Research on Climate Change Adaptation of Water Infrastructure in the Mediterranean Region. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, W.; Guiot, J.; Marini, K.; Azzopardi, B.; Balzan, M.V.; Semia Cherif; Doblas-Miranda, E.; Santos, M.D.; Drobinski, P.; Fader, M.; et al. MedECC 2020 Summary for Policymakers. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin – Current Situation and Risks for the Future. First Mediterranean Assessment Report; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020;

- Ali, E.; Cramer, j.; Georgopoulou, E.; Hilmi, N.J.M.; Le Cozannet, G.; Lionello, P. Cross-Chapter Paper 4: Mediterranean Region. In In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ; Pörtner, H.O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK and New York, New York, USA; pp. 2233–2272.

- Douvis, K.; Kapsomenakis, J.; Solomos, S.; Poupkou, A.; Stavraka, T.; Nastos, P.; Zerefos, C. Change in Aridity Index in the Mediterranean Region under Different Emission Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Meteorology, Climatology and Atmospheric Physics—COMECAP 2023; MDPI, September 5 2023; p. 171.

- Ruffault, J.; Curt, T.; Moron, V.; Trigo, R.M.; Mouillot, F.; Koutsias, N.; Pimont, F.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Barbero, R.; Dupuy, J.-L.; et al. Increased Likelihood of Heat-Induced Large Wildfires in the Mediterranean Basin. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 13790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolongo, D.; Diodato, N.; Mannaerts, C.M.; Piccarreta, M.; Strobl, R.O. Analyzing Temporal Changes in Climate Erosivity Using a Simplified Rainfall Erosivity Model in Basilicata (Southern Italy). Journal of Hydrology 2008, 356, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Large Dams - ICOLD Global Climate Change, Dams, Reservoirs and Related Water Resources”; 2016;

- Mallakpour, I.; AghaKouchak, A.; Sadegh, M. Climate-Induced Changes in the Risk of Hydrological Failure of Major Dams in California. Geophysical Research Letters 2019, 46, 2130–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Carvalho-Santos, C.; Diogo, P.; Beça, P.; Keizer, J.J.; Nunes, J.P. Impacts of Climate Change on Reservoir Water Availability, Quality and Irrigation Needs in a Water Scarce Mediterranean Region (Southern Portugal). Science of The Total Environment 2020, 736, 139477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.N.; Schulenberg, J.W.; Neilsen, M.L. Sensitivity Analysis of the Auxiliary Spillway Erosion Based on the Material and Structural Properties. In Geo-Extreme 2021; pp. 111–126.

- Ghimire, S.N.; Schulenberg, J.W. Impacts of Climate Change on the Environment, Increase in Reservoir Levels, and Safety Threats to Earthen Dams: Post Failure Case Study of Two Cascading Dams in Michigan. Civil and Environmental Engineering 2022, 18, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juško, V.; Sedmák, R.; Kúdela, P. Siltation of Small Water Reservoir under Climate Change: A Case Study from Forested Mountain Landscape of Western Carpathians, Slovakia. Water 2022, 14, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, P.; Szlapa, M.; Hachaj, P.S.; Orlińska-Woźniak, P.; Jakusik, E.; Szalińska, E. From the Source to the Reservoir and beyond—Tracking Sediment Particles with Modeling Tools under Climate Change Predictions (Carpathian Mts.). J Soils Sediments 2022, 22, 2929–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, C.; Tilmant, A.; Pulido-Velazquez, M. A Hydrologically-Driven Approach to Climate Change Adaptation for Multipurpose Multireservoir Systems. Climate Risk Management 2022, 36, 100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacTavish, L.; Bourgeois, G.; Lafleur, C.; Ristic, E. Climate Change Adaptation for Dams. A Review of Climate Vulnerabilities, Adaptation Measures, and Opportunities for Growth in the Canadian Dams Context; Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, 2022; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, I.; Kadhom, B.; Roshani, E.; Shirkhani, H.; Hiedra-Cobo, J.; Cusson, D.; Nkinamubanzi, P.-C. Adaptation of Dams to Climate Change: Gap Analysis; National Research Council of Canada. Construction Research Centre, 2023; Vol. A1-020144-R01;

- Krztoń, W.; Walusiak, E.; Wilk-Woźniak, E. Possible Consequences of Climate Change on Global Water Resources Stored in Dam Reservoirs. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 830, 154646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandesten, C.-O. Impact of Climate Change on Dam Safety; Energiforsk AB: Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Shang, Y. Nexus of Dams, Reservoirs, Climate, and the Environment: A Systematic Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 12707–12716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lompi, M.; Mediero, L.; Soriano, E.; Caporali, E. Climate Change and Hydrological Dam Safety: A Stochastic Methodology Based on Climate Projections. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2023, 68, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, M.; Todaro, V.; Maranzoni, A.; D’Oria, M. Combining Hydrological Modeling and Regional Climate Projections to Assess the Climate Change Impact on the Water Resources of Dam Reservoirs. Water 2023, 15, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC) Commission Notice — Technical Guidance on the Climate Proofing of Infrastructure in the Period 2021-2027 2021.

- Stamou, A.; Mitsopoulos, G.; Koutroulis, A. Proposed Methodology for Climate Change Adaptation of Water Infrastructures in the Mediterranean Region. Environ. Process. 2024, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The world bank Trust Fund for Environmentally & Socially Sustainable Development, Water & Climate Adaptation Plan for the Sava River Basin, ANNEX 3 - Guidance Note on Adaptation to Climate Change for– Hydropower; 2015;

- Helman, J.M. It’s Hot and Getting Hotter: Implications of Extreme Heat on Water Utility Staff and Infrastructure, and Ideas for Adapting; WUCA & AMWA, 2020.

- European Commission. Directorate General for Climate Action. EU-Level Technical Guidance on Adapting Buildings to Climate Change.; Publications Office: LU, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Shi, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Woolway, R.I. The Impact of Extreme Heat on Lake Warming in China. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Investment Bank, JASPERS Publications Office Approach to Climate Proofing for Water and Wastewater Projects Available online:. Available online: https://jaspers.eib.org/knowledge/publications/climate-proofing-of-water-and-wastewater-projects (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- European Investment Bank, JASPERS Publications Office Case Study:Climate Proofing of Water and Wastewater Projects Available online:. Available online: https://jaspers.eib.org/knowledge/publications/climate-proofing-of-water-and-wastewater-projects (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- European Investment Bank, JASPERS Publications Office Approach to Climate Proofing for Flood and Disaster Risk Management Projects Available online:. Available online: https://jaspers.eib.org/knowledge/publications/climate-proofing-of-flood-and-disaster-risk -management-projects (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- European Investment Bank, JASPERS Publications Office Case Study: Climate Proofing of a Flood Protection Project Available online:. Available online: https://jaspers.eib.org/knowledge/publications/climate-proofing-of-flood-and-disaster-risk -management-projects (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- BS EN 1990:2002 EN 1990 Eurocode - Basis of Structural Design; British Standards Institution: London, UK, 1990.

- Haseeb, J. Components of Dams | Functions of Components of Dams Available online:. Available online: https://www.aboutcivil.org/components-of-dams-and-their-functions.html (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Gopinath, V. Components of Dam – 12 Dam Components Explained Available online:. Available online: https://vincivilworld.com/2022/10/17/components-of-dam-functions/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- FEMA Dam Safety Federal Guidelines Available online:. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/dam-safety/federal-guidelines (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Johnson, M.F.; Albertson, L.K.; Algar, A.C.; Dugdale, S.J.; Edwards, P.; England, J.; Gibbins, C.; Kazama, S.; Komori, D.; MacColl, A.D.C.; et al. Rising Water Temperature in Rivers: Ecological Impacts and Future Resilience. WIREs Water 2024, 11, e1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, R.; Hellgren, R.; Enzell, J. Lessons Learned Regarding Cracking of a Concrete Arch Dam Due to Seasonal Temperature Variations. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Comi, C. Hydro-Thermo-Mechanical Analysis of an Existing Gravity Dam Undergoing Alkali–Silica Reaction. Infrastructures 2019, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhena, R.M.; Mascarenha, M.M.D.A.; Sales, M.M.; Romão, P.D.A.; Luz, M.P.D. Estimating the Wind-Generated Wave Erosivity Potential: The Case of the Itumbiara Dam Reservoir. Water 2019, 11, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices (ETCCDI) Indices of CLIMPACT and CLIMDEX Available online: https://www.climdex.org/learn/indices/.

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (Ipcc) Annex VI: Climatic Impact-Driver and Extreme Indices [Gutiérrez J.M., R. Ranasinghe, A.C. Ruane, R. Vautard (Eds.)]. In Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)].; Cambridge University Press, 2021 ISBN 978-1-00-915789-6.

- Svoboda, M.D.; Fuchs, B.A. Handbook of Drought Indicators and Indices; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, 2016; ISBN 978-92-63-11173-9. [Google Scholar]

- Climate -Adapt Overview List of All Indices Available online:. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/knowledge/european-climate-data-explorer/overview-list (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Crespi, A.; Terzi, S.; Cocuccioni, S.; Zebisch, M.; Berckmans, J.; Füssel, H.-M. Climate-Related Hazard Indices for Europe. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kougianos and Partners; LDK Consultants; Geosynolo LTD; Afrateos I. River Basin Management Plan of Western Macedonia River Basin District - 2nd revision; Ministry of the Environment and Energy, 2024.

- Morrill, J.C.; Bales, R.C.; Conklin, M.H. Estimating Stream Temperature from Air Temperature: Implications for Future Water Quality. J. Environ. Eng. 2005, 131, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environplan, S.A. ; Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Prefecture Plan for Climate Change Adaptation (PESPKA) - Prefecture of Central Macedonia; Prefecture of Central Macedonia: Thessaloniki, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Berhanu, B.; Melesse, A.M.; Seleshi, Y. GIS-Based Hydrological Zones and Soil Geo-Database of Ethiopia. CATENA 2013, 104, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwi Purwanti, S.; Putu Okta Veanti, D.; Sucahyono Sosaidi, D.; Adhitiansyah, D.; Abil Nurjani, M.; Yuwan Purnama, F.; Fatahilah Raymon, M. Probability of Hotspots Emergence Using Consecutive Dry Days (CDD) in West Kalimantan. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 464, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yan, Z.; Sha, J.; Li, S. Drought Evolution Due to Climate Change and Links to Precipitation Intensity in the Haihe River Basin. Water 2017, 9, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, R.B. Observed Trends and Variations in Rainfall Events over Ratnagiri (Maharashtra) during Southwest Monsoon seasonSonar. MAUSAM 2014, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Ballav, S.; Soni, S.; Kumar, K.; Kumar De, U. Investigation of Dominant Modes of Monsoon ISO in the Northwest and Eastern Himalayan Region. Theor Appl Climatol 2016, 125, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faradiba Analysis of Intensity, Duration, and Frequency Rain Daily of Java Island Using Mononobe MethodFaradiba_2021_J._Phys.__Conf._Ser._1783_012107(1).Pdf. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 012107. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.; Petersen, J.; Eggert, B.; Alias, A.; Christensen, O.B.; Bouwer, L.M.; Braun, A.; Colette, A.; Déqué, M.; Georgievski, G.; et al. EURO-CORDEX: New High-Resolution Climate Change Projections for European Impact Research. Reg Environ Change 2014, 14, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellström, E.; Nikulin, G.; Strandberg, G.; Christensen, O.B.; Jacob, D.; Keuler, K.; Lenderink, G.; Van Meijgaard, E.; Schär, C.; Somot, S.; et al. European Climate Change at Global Mean Temperature Increases of 1.5 and 2 °C above Pre-Industrial Conditions as Simulated by the EURO-CORDEX Regional Climate Models. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2018, 9, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, D.P.; Edmonds, J.; Kainuma, M.; Riahi, K.; Thomson, A.; Hibbard, K.; Hurtt, G.C.; Kram, T.; Krey, V.; Lamarque, J.-F.; et al. The Representative Concentration Pathways: An Overview. Climatic Change 2011, 109, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (Ipcc) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability 2022.

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC) Summary for Policymakers. In In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR, White LL (eds); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York NY USA, 2014; pp. 1–32.

- European Commission (EC) Directive (EU) 2022/2557 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on the Resilience of Critical Entities and Repealing Council Directive 2008/114/EC 2022.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2023.

| Category of Hazard Based on IPCC [14] | Symbol | Type of Hazard |

|---|---|---|

| Heat and Cold (HC) | HC1 | Mean air temperature (increase) |

| HC2 | Extreme heat—Heat waves | |

| HC3 | Cold spells and frost | |

| Wet and Dry (WD) | WD1 | Mean precipitation (decrease) |

| WD2 | Extreme precipitation | |

| WD3 | Flooding (fluvial and pluvial) | |

| WD4 | Aridity | |

| WD5 | Drought | |

| WD6 | Wildfires | |

| WD7 | Soil erosion | |

| WD8 | Landslide (incl. mudflows) | |

| WD9 | Land subsidence | |

| WD10 | Water temperature | |

| Wind and Air (WA) | WA1 | Mean wind speed (increase) |

| WA2 | Extreme winds | |

| WA3 | Air quality (change) | |

| Coastal (C) | C1 | Relative (mean) sea level (rise) |

| C2 | Coastal flooding | |

| C3 | Coastal erosion | |

| C4 | Saline intrusion | |

| C5 | Sea water temperature (and marine heat waves) | |

| C6 | Sea water quality (incl. salinity and acidity) | |

| Snow and Ice (SI) | SI1 | Snow and land ice |

| SI2 | Avalanche |

| Groups of components | Symbol | Component |

|---|---|---|

| Input (I) | I | Inflows |

| Functions (P) | P1 P2 P3 P4 |

Storage Flood control Hydropower Recreation |

| Assets (A) | A1 A2 A3 A4 |

Embankment Spillway Auxiliaries Buildings |

| Outflow (O) | O1 O2 O3 |

Water supply Hydropower production Water releases |

| Supporting infrastructure (S) |

S1 S2 S3 S4 |

Power supply. Communications. Transportation. Personnel. |

| Component | Potential impacts | TNm | TMm | TXm | WTLS | GSL | GDD | HD | TX35 | TR | HWD | DTR | CD | ID | FD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-I Inflows | Increased river water temperature and degraded water quality (Τ-Ι). | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| T-P1 Storage | Increased water temperature; increased vegetation growth; increased evapotranspiration; reduced water storage volume; increased stratification; degraded water quality; increased adverse impacts on fish. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| T-P2 Flood control |

Improved flood control. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| T-P3 Hydropower | Reduced potential for hydropower production. | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| T-P4 Recreation | Reduced recreation, aesthetic value and biodiversity; navigation problems. | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| T-A1 Earthfill dams |

Increased growth of shrubs, trees and vegetation; grass kill; tree fall and uprooting during storm events; desiccation and shrinking of clay; erosion of crest and faces of the dam; damages to exposed parts of the dam, such as liners, joint materials and binding mixes (especially during prolonged low/fluctuating reservoir water levels; see D-P1). | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| T-A1 Concrete dams |

Expansion, cracking and spalling of concrete; damage to concrete and masonry/jointing materials; drying and shrinking of concrete (when combined with persistent drought). | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| T-A2 Spillway | Blockage due to vegetation; thermal expansion and cracking. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| T-A3 Auxiliaries | Cracking of concrete structures; expansion of metal elements. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| T-A4 Buildings | Increased power demand for cooling; reduced lifespan of building components. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| T-O1 Water supply |

Water may not be suitable for use due to its degraded quality; increased demand for drinking and irrigation water during hotter summers increases. | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| T-O2 Hydropower | Increased power demand during summers and heat waves. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| T-O3 Water releases | Pollution of downstream watercourses with adverse impacts on fish populations; management conflicts for multi-purpose reservoirs. | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| T-S1 Power supply | Increased risk of outages; damage of electrical and electronic components. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| T-S2 Communications | Obscuring monitoring sites and gauge boards; damage of monitoring devices. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| T-S3 Transportation | Damage of parking lot asphalt binders and access roads; poor accessibility. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| T-S4 Personnel | Reduced thermal comfort, occupational health and safety; increased maintenance requirements. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Component | Potential impacts | PRCPTOT | CDD | CWD | NPD | RDI | SSI | HD | TX35 | TR | HWD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-I Inflows | Reduced flowrates and degraded water quality; this impact is more pronounced when it coincides with temperature increase and heat waves. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| D-P1 Storage | Reduced reservoir volumes and water levels; prolonged low/fluctuating reservoir water levels resulting in the exposure of parts of the dam; degraded water quality; reduced water supply potential. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| D-P2 flood control | Improved flood control. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| D-P3 Hydropower | Reduced potential for hydropower production. | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| D-P4 Recreation | Reduced recreation, aesthetic value and biodiversity; prevention of certain types of recreation; health issues. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| D-A1 Earthfill Dams | Desiccation and shrinkage of clay core and dam shoulders; seepage and piping; loss of vegetation cover; soil erosion; subsidence; slumping; dam erosion (when draught is combined with intense rainfall (D-A1); erosion or damage of the exposed parts of the dam due to waves (caused by strong winds on the water surface of reservoirs; see S-A1), and due to high air temperature (see T-A1) and UV sunlight. | ||||||||||

| D-A1 Concrete Dams | Drying and shrinking of concrete (when combined with high temperatures). | ||||||||||

| D-A2 Spillway | - | ||||||||||

| D-A3 Auxiliaries | Increased exposure and wave/sun damage to joint materials. | ||||||||||

| D-A4 Buildings | - | ||||||||||

| D-O1 Water supply | Treatment of water may be required prior to use; increased demand for drinking and irrigation water supply during hotter summers (D-O1). | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| D-O2 Hydropower | Reduced potential for hydropower production. | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| D-O3 Water releases | Demand for increased environmental flow; reduced availability for flushing during summer; management conflicts for multi-purpose reservoirs (D-O3). | √ | √ |

√ |

|||||||

| D-S1 Power supply | - | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| D-S2 Communications | - | ||||||||||

| D-S3 Transportation | - | ||||||||||

| D-S4 Personnel | More difficult working conditions for personnel. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Component | Potential impacts | PRCPTOT | HR | R20mm | R95pTOT | Rx1day | EP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-I Inflows | Increased flow rates, sediment loads and debris; mobilized vegetation; degraded water quality. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| F-P1 Storage | Increased water levels: increased sediments, debris, mobilized vegetation and turbidity; rapid fluctuations in operating water levels; degraded water quality; reduced water storage volume due to sediments. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| F-P2 Flood control | Increased risk for flooding, overtopping and downstream flooding; reduced operating levels to face flood risk. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| F-P3 Hydropower | Reduced operating levels; reduced availability or flexibility for hydropower generation; increased potential for hydropower production during winter. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| F-P4 Recreation | Reduced recreational safety; reduced aesthetic value; negative impacts on navigation and sports. | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| F-A1 Earthfill dams | Increased pore pressure; increased risks for piping, overtopping, seepage and erosion. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| F-A1 Concrete dams | Increased risks of overtopping, sliding and overturning; increased risk of dam cracking and failure (when sudden heavy rainfall follows persistent drought); increased drainage and erosion of joint materials due to fluctuating water levels or heavy rainfall. | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| F-A2 Spillway | Blockage due to mobilized vegetation; failure due to increased flow rates, flow velocities and water levels; rapid deterioration of flaws. | √ | √ | √ | |||

| F-A3 Auxiliaries | Damage of dam components due to debris; failure of pipes; erosion and sediment build-up around structures; landslides; silt buildup and blocking of inlets; rusting of dam components; rapid deterioration of flaws. | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| F-A4 Buildings | Damp and mold due to high precipitation; inundation; electricity supply outage. | √ | √ | ||||

| F-O1 Water supply | Treatment of water may be required prior to use. | ||||||

| F-O2 Hydropower | Reduced availability or flexibility for hydropower generation during high precipitation; increased water availability during winter. | ||||||

| F-O3 Water releases | Impacts to downstream watercourses due to flooding, overtopping, piping and pollution. | √ | |||||

| F-S1 Power supply | Outages of power systems. | √ | √ | ||||

| F-S2 Communications | Hampered communications. | ||||||

| F-S3 Transportation | Damaged access roads. | √ | √ | ||||

| F-S4 Personnel | Hampered outdoor working conditions and maintenance. | √ | √ |

| Hazard | Indicator | 1981-2000 | 2041- 2060 RCP8.5 |

2081- 2100 RCP8.5 |

2041- 2060 RCP4.5 |

2081- 2100 RCP4.5 |

2041- 2060 RCP8.5 |

2081- 2100 RCP8.5 |

2041- 2060 RCP4.5 |

2081- 2100 RCP4.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC1 & HC2 | TNm | 8 | 10.32 | 12.96 | 9.68 | 9.99 | 2.32 | 4.96 | 1.68 | 1.99 |

| TXm | 17.97 | 20.47 | 23.43 | 19.76 | 20.11 | 2.5 | 5.46 | 1.79 | 2.14 | |

| HD | 41 | 75 | 106 | 68 | 74 | 34 | 65 | 27 | 33 | |

| TX35 | 5 | 21 | 54 | 19 | 20 | 16 | 49 | 14 | 15 | |

| TR | 21 | 53 | 88 | 45 | 49 | 32 | 67 | 24 | 28 | |

| WD1, WD4 & WD5 | PRCPTOT | 613 | 549 | 439 | 615 | 550 | -64 | -174 | 2 | -63 |

| CDD | 55 | 65 | 77 | 64 | 62 | 10 | 22 | 9 | 7 | |

| WD2 & WD3 | R20mm | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rx1day | 38.85 | 43.12 | 41.31 | 51.06 | 41.58 | 4.27 | 2.46 | 12.21 | 2.73 |

| Groups of components |

Components | Temperature increase and extreme heat (HC1 &HC2) |

Precipitation decrease, aridity and droughts (WD1, WD4 & WD5) |

Extreme precipitation and flooding (WD2 & WD3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input (I) | I1 River water | M | H | H |

| Functions (P) | P2 Storage | M | H | H |

| Assets (A) |

A1 Dam | M | M | H |

| A2 Spillway | M | M | H | |

| A3 Auxiliary | L | L | L | |

| A4 Buildings | L | L | M | |

| Outflow (O) |

O1 Water for irrigation | M | H | H |

| O3 Water release | L | M | L | |

| Supporting Infrastructure (S) |

S1 Electric power | M | L | M |

| S2 Communications | L | L | M | |

| S3 Transportation | L | L | M | |

| S4 Personnel | M | L | M | |

| Group I | Highest score of each group |

M | H | H |

| Group P | M | H | H | |

| Group A | M | M | H | |

| Group O | M | H | H | |

| Group S | M | L | M | |

| Almopeos D&R system | Highest score of all groups |

M | H | H |

| Hazard | Indicator | Scenario | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | ||||

| 2041- 2060 | 2081- 2100 | 2041- 2060 | 2081- 2100 | ||

| HC1 & HC2 | TXm | H | H | M | H |

| WD1, WD4 & WD5 | CDD | M | H | L | L |

| WD2 & WD3 | Rx1day | H | M | H | M |

| Exposure | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Scenario | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | ||||||||

| Period | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | |||

| 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | ||||

| Groups of climate risks (indicator) | HC1 & HC2 (TXm) | WD1, WD4 & WD5 (CDD) | WD2 & WD3 (Rx1day) | ||||||||||||

| Components | I | Ι1 River water | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | M(H/L) | M(H/L) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | |

| P | P2 Storage | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | M(H/L) | M(H/L) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | ||

| A | A1 Dam | H(Μ/H) | H(Μ/H) | M(Μ/M) | H(Μ/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | L(M/L) | L(M/L) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | ||

| A2 Spillway | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | L(M/L) | L(M/L) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | |||

| A3 Auxiliary | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/L) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | |||

| A4 Buildings | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/L) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | |||

| O | O1 Water for irrigation | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | M(H/L) | M(H/L) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | H(H/M) | ||

| O3 Water release | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | L(M/L) | L(M/L) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | |||

| S | S1 Electric Power | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/L) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | ||

| S2 Communications | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/L) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | |||

| S3 Transportation | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/L) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | |||

| S4 Personnel | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/L) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | |||

| Groups | Group I | H | H | M | H | H | H | M | M | H | H | H | H | ||

| Group P | H | H | M | H | H | H | M | M | H | H | H | H | |||

| Group A | H | H | M | H | M | H | L | L | H | H | H | H | |||

| Group O | H | H | M | H | H | H | M | M | H | H | H | H | |||

| Group S | H | H | M | H | L | M | L | L | H | M | H | M | |||

| D&R Almopeos system | H | H | M | H | H | H | M | M | H | H | H | H | |||

| Exposure | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Scenario | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | ||||||||

| Period | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | |||

| 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | ||||

| Groups of climate risks | TNm and TR | HD | TX35 | ||||||||||||

| Components | I | Ι1 River water | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | H↑(M/H↑) | H(M/H) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | |

| P | P2 Storage | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | H↑(M/H↑) | H(M/H) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | ||

| A | A1 Dam | H(Μ/H) | H(Μ/H) | M(Μ/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(Μ/H) | H(Μ/H) | H↑(M/H↑) | H(Μ/H) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(Μ/H) | M(Μ/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | ||

| A2 Spillway | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | H↑(M/H↑) | H(M/H) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | |||

| A3 Auxiliary | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | M↑(L/H↑) | M(L/H) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | |||

| A4 Buildings | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | M↑(L/H↑) | M(L/H) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | |||

| O | O1 Water for irrigation | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | H↑(M/H↑) | H(M/H) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | ||

| O3 Water release | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | M↑(L/H↑) | M(L/H) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | |||

| S | S1 Electric Power | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | H↑(M/H↑) | H(M/H) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | ||

| S2 Communications | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | M↑(L/H↑) | M(L/H) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | |||

| S3 Transportation | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | M(L/H) | M↑(L/H↑) | M(L/H) | L↓ (L/M↓) | M(L/H) | L(L/M) | L↓ (L/M↓) | |||

| S4 Personnel | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | H(M/H) | H↑(M/H↑) | H(M/H) | M↓(M/M↓) | H(M/H) | M(M/M) | M↓(M/M↓) | |||

| Groups | Group I | H | H | M | M↓ | H | H | H↑ | H | M↓ | H | M | M↓ | ||

| Group P | H | H | M | M↓ | H | H | H↑ | H | M↓ | H | M | M↓ | |||

| Group A | H | H | M | M↓ | H | H | H↑ | H | M↓ | H | M | M↓ | |||

| Group O | H | H | M | M↓ | H | H | H↑ | H | M↓ | H | M | M↓ | |||

| Group S | H | H | M | M↓ | H | H | H↑ | H | M↓ | H | M | M↓ | |||

| D&R Almopeos system | H | H | M | M↓ | H | H | H↑ | H | M↓ | H | M | M↓ | |||

| Exposure | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Scenario | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | ||||||

| Period | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | 2041- | 2081- | |||

| 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | 2060 | 2100 | ||||

| Groups of climate risks | PRCTOT | R20 | |||||||||

| Components | I | Ι1 River water | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | M(H/L) | H↑(H/M↑) | H(H/M↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | |

| P | P2 Storage | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | M(H/L) | H↑(H/M↑) | H(H/M↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | ||

| A | A1 Dam | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | L(M/L) | M↑(M/M↑) | H(H/M↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | ||

| A2 Spillway | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | L(M/L) | M↑(M/M↑) | H(H/M↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | |||

| A3 Auxiliary | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/M↑) | L↓(L/M↓) | L(L/L↓) | L(L/L↓) | L(L/L↓) | |||

| A4 Buildings | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/M↑) | M↓(M/M↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | |||

| O | O1 Water for irrigation | H(H/M) | H(H/H) | M(H/L) | H↑(H/M↑) | H(H/M↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | M↓(H/L↓) | ||

| O3 Water release | M(M/M) | H(M/H) | L(M/L) | M↑(M/M↑) | L↓(L/M↓) | L(L/L↓) | L(L/L↓) | L(L/L↓) | |||

| S | S1 Electric Power | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/M↑) | M↓(M/M↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | ||

| S2 Communications | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/M↑) | M↓(M/M↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | |||

| S3 Transportation | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/M↑) | M↓(M/M↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | |||

| S4 Personnel | L(L/M) | M(L/H) | L(L/L) | L(L/M↑) | M↓(M/M↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | L↓(M/L↓) | |||

| Groups | Group I | H | H | M | H↑ | H | M↓ | M↓ | M↓ | ||

| Group P | H | H | M | H↑ | H | M↓ | M↓ | M↓ | |||

| Group A | M | H | L | M↑ | H | M↓ | M↓ | M↓ | |||

| Group O | H | H | M | H↑ | H | M↓ | M↓ | M↓ | |||

| Group S | L | M | L | L | M↓ | L↓ | L↓ | L↓ | |||

| D&R Almopeos system | H | H | M | H↑ | H | M↓ | M↓ | M↓ | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).