Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

19 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of This Study

1.2. Brief Review of the Existing Solutions for Mobility Anomaly Detection

- Economical Feasibility – The system should be affordable for at-risk individuals (e.g., seniors and their families) or covered by the healthcare financing system to ensure accessibility.

- Scalability – It should be cost-effective and capable of being deployed widely to benefit large populations.

- Unobtrusiveness – The monitoring should be as transparent as possible to the individual. Ideally, no wearable or carried devices should be required, relying instead on passive sensors or cameras.

- Continuity of Sensing – The system should collect data frequently or continuously to track patient-specific trends and enable just-in-time interventions.

- Usability – The system should be easy to install, operate, and maintain, requiring minimal effort. It should have features like portability, long battery life, and self-calibration.

- Adaptability – The system must adjust to individual users, various locations, and changing environmental conditions.

- Self-Checking – It should have the capability to monitor and assess its own performance for reliability.

- High Sensitivity and Specificity (Low False Alarms) – Accuracy is critical to avoid excessive false alarms while maintaining effective monitoring and event detection.

- Privacy and Security – The system must ensure the security and privacy of both individuals and care teams. This includes authentication, data sharing policies, and protection against unauthorized access.

- Workflow Integration – The system must seamlessly integrate into provider and caregiver workflows without creating additional burdens.

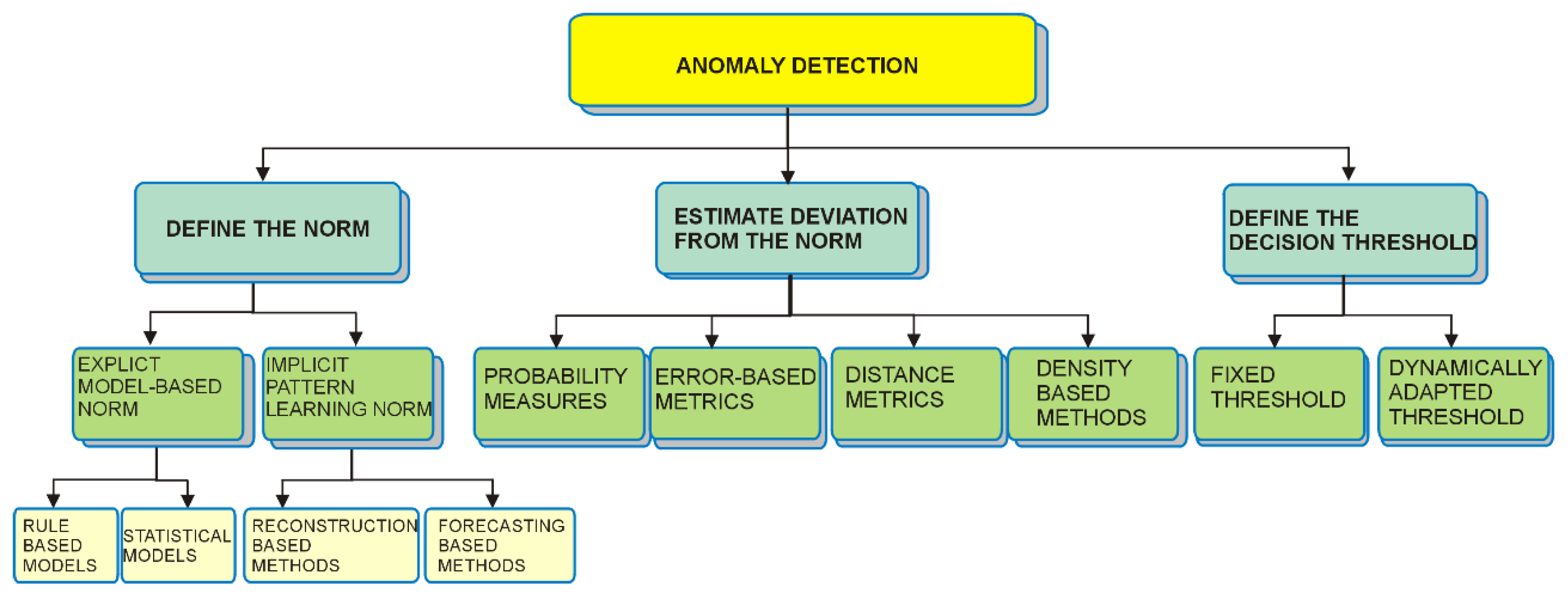

- Defining the norm (i.e., characterizing what “normal” mobility looks like),

- Estimating deviations from that norm (using measures such as distances, probabilities, or reconstruction errors),

- Determining a decision threshold (fixed or dynamically adapted) that marks the boundary between normal and abnormal behavior.

1.3. Objective of This Study

2. Method and Datasets

2.1. Assumptions

2.2. Datasets and Preprocessing

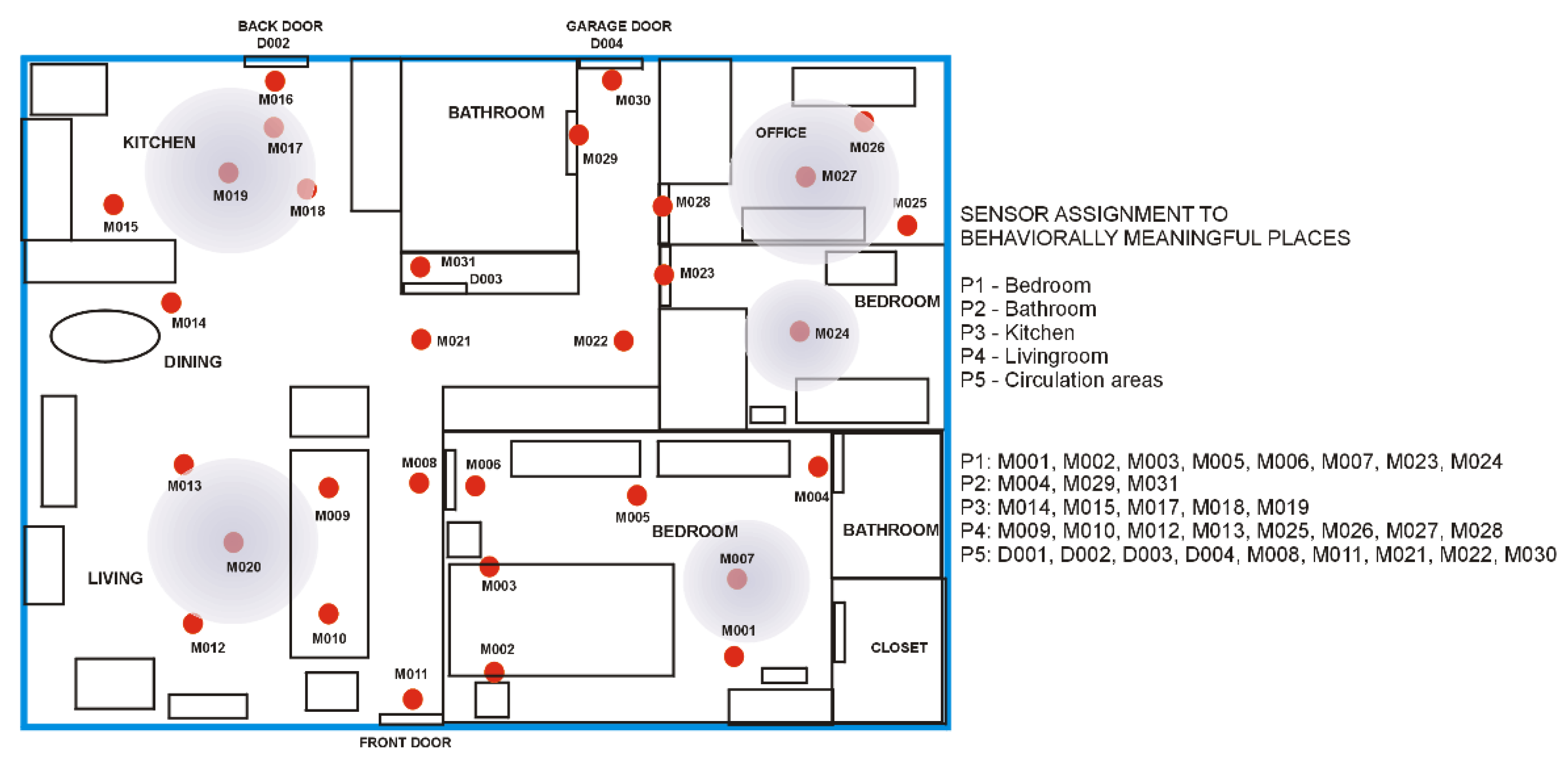

2.3. An Abstraction of the Residential Space

| {P1} = {M001} ∪ {M002} ∪ {M003} ∪ {M005} ∪ {M006 ∪ {M007} ∪ {M023} ∪ {M024} | (1) |

| {P2} = {M004} ∪ {M029} ∪ {M031} | |

| {P3} = {M014} ∪ {M015} ∪ {M017} ∪ {M018} ∪ {M019} | |

| {P4} = {M009} ∪ {M010} ∪ {M012} ∪ {M013} ∪ {M025} ∪ {M026} ∪ {M027} ∪ {M028} | |

| {P5} = {D001} ∪ {D002} ∪ {D003} ∪ {D004} ∪ {M008} ∪ {M011} ∪ {M021} ∪ {M022} ∪ {M030} |

| {P1} = {M009} ∪ {M010} ∪ {M011} ∪ {MA016} | (2) |

| {P2} = {M008} ∪ {M018} | |

| {P3} = {MA017} | |

| {P4} = {M003} ∪ {M004} ∪ {M005} ∪ {M006} ∪ {M007} ∪ {M026} ∪ {MA015} | |

| {P5} = {D002} ∪ {D004} ∪ {M001} ∪ {M002} ∪ {M011} |

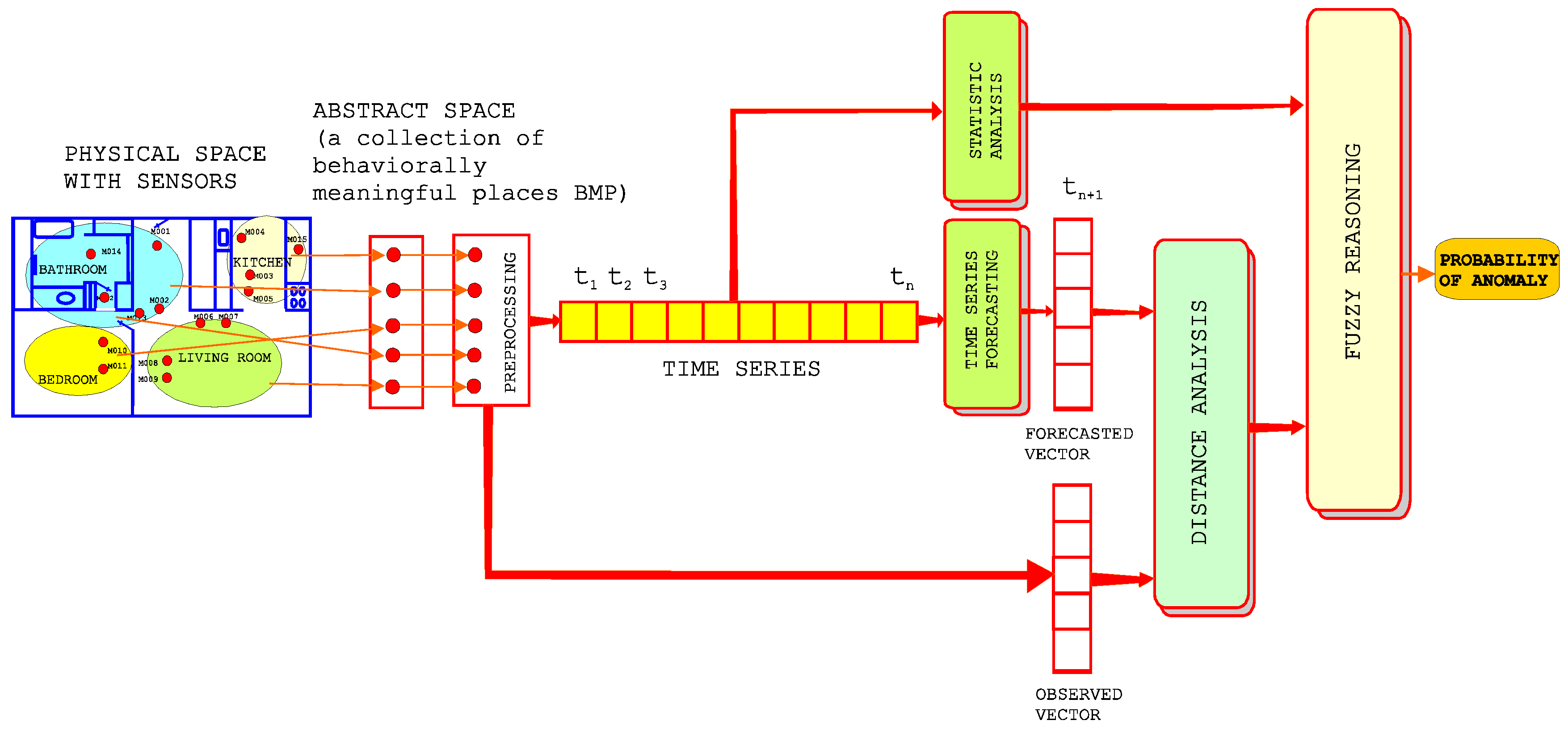

2.4. Encoding the Activity Starting from Sensor Data

2.5. Detecting Mobility Loss

| Algorithm 1. Data processing workflow for detecting point mobility anomalies |

| BEGIN |

| // === Step 1: Data Preprocessing === |

| // Load raw sensor data (each record: Timestamp, Sensor_ID, Sensor_Event, etc.) |

| raw_data ← LOAD_SENSOR_DATA("raw_sensor_file.txt") |

| // Filter out sensors not related to mobility (e.g., temperature, light) |

| filtered_data ← FILTER(raw_data, sensor_type NOT IN {"temperature", "light"}) |

| // Remove unwanted events: |

| // - Exclude OFF events for motion sensors. |

| // - Exclude CLOSE events for door sensors. |

| filtered_data ← FILTER(filtered_data, |

| (sensor_category = "motion" AND event_type ≠ "OFF") AND |

| (sensor_category = "door" AND event_type ≠ "CLOSE")) |

| // Mitigate sensor noise: |

| // For each sensor, if two successive events occur within 60 seconds, remove the second. |

| debounced_data ← DEBOUNCE(filtered_data, time_threshold = 60 seconds) |

| // Aggregate events: |

| // Count the number of events per sensor in one-hour intervals. |

| hourly_counts ← AGGREGATE(debounced_data, interval = "1 hour") |

| // === Step 2: Abstract Residential Space into Behaviorally Meaningful Places (BMPs) === |

| // Define sensor-to-BMP mappings: |

| BMP1_sensors ← {M001, M002, M003, M005, M006, M007, M023, M024} |

| BMP2_sensors ← {M004, M029, M031} |

| BMP3_sensors ← {M014, M015, M017, M018, M019} |

| BMP4_sensors ← {M009, M010, M012, M013, M025, M026, M027, M028} |

| BMP5_sensors ← {D001, D002, D003, D004, M008, M011, M021, M022, M030} |

| // For each time interval, sum events per BMP. |

| FOR each time_interval IN hourly_counts DO |

| P1 ← SUM_EVENTS(hourly_counts[time_interval], sensors IN BMP1_sensors) |

| P2 ← SUM_EVENTS(hourly_counts[time_interval], sensors IN BMP2_sensors) |

| P3 ← SUM_EVENTS(hourly_counts[time_interval], sensors IN BMP3_sensors) |

| P4 ← SUM_EVENTS(hourly_counts[time_interval], sensors IN BMP4_sensors) |

| P5 ← SUM_EVENTS(hourly_counts[time_interval], sensors IN BMP5_sensors) |

| // Construct the activity vector A(tk) for this interval |

| activity_vector[time_interval] ← [P1, P2, P3, P4, P5] |

| END FOR |

| // === Step 3: Encode Activity Level === |

| // Compute the overall activity level (AL) as the L2 norm of the activity vector. |

| FOR each time_interval IN activity_vector DO |

| AL[time_interval] ← SQRT( (P1)^2 + (P2)^2 + (P3)^2 + (P4)^2 + (P5)^2 ) |

| END FOR |

| // === Step 4: Predict and Compare Activity for Mobility Loss Detection === |

| // Assume a predictive model is available, trained on historical activity data. |

| FOR each new time interval t DO |

| // Predict the activity vector for the next interval |

| predicted_vector ← PREDICT_ACTIVITY(activity_vector, current_time = t) |

| // Retrieve the observed activity vector for the next interval |

| observed_vector ← activity_vector[t + 1] |

| // Compute Euclidean distance (Dist) between predicted and observed vectors |

| Dist ← SQRT( SUM( (observed_vector[i] - predicted_vector[i])^2 for i = 1 to 5 ) ) |

| // Compute Observed Activity Level ratio (OAL) |

| // HAL is the historical average AL for the corresponding hour (from training data) |

| HAL ← HISTORICAL_AVERAGE_AL(hour = t + 1) |

| OAL ← AL[t + 1] / HAL |

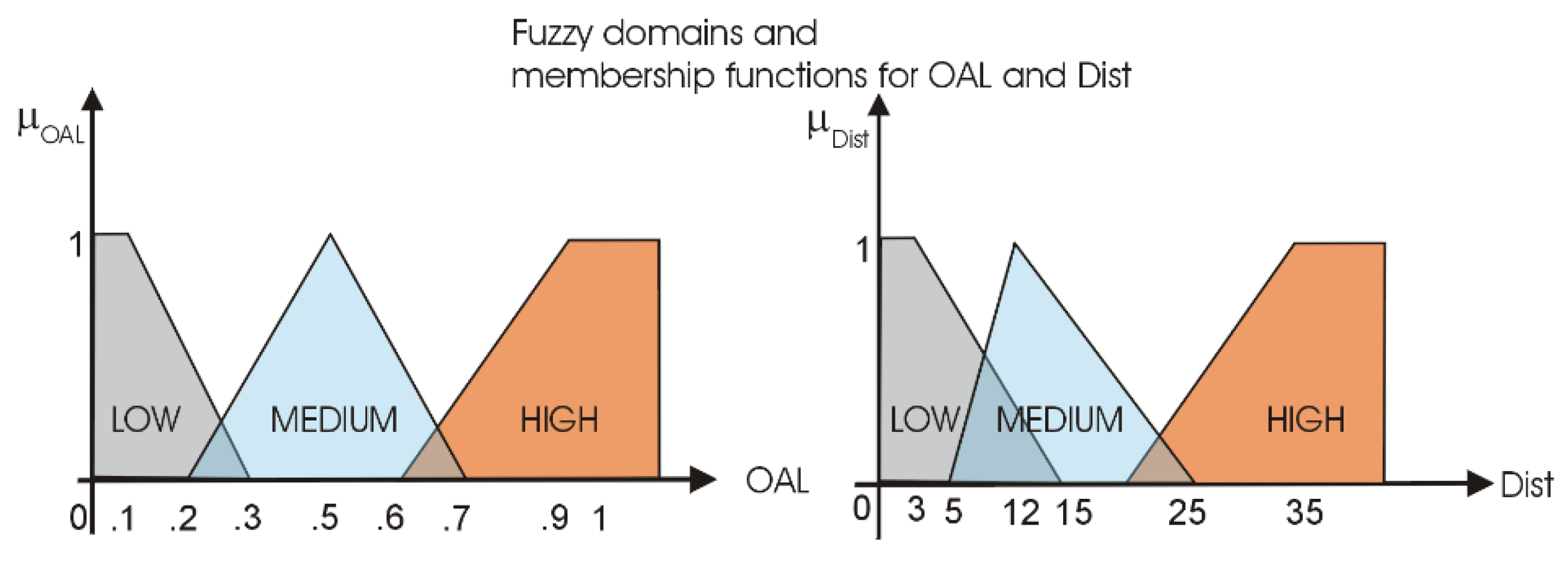

| // === Step 5: Fuzzy Inference for Mobility Anomaly === |

| // Use OAL and Dist as input to a fuzzy reasoning module. |

| // The module applies linear membership functions (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH) and a rule base. |

| PA ← FUZZY_INFERENCE_MODULE(OAL, Dist) |

| // Output the estimated probability of mobility anomaly for this interval |

| OUTPUT(time = t + 1, anomaly_probability = PA) |

| IF (PA>ALERT_THRESHOLD) THEN ALERT_FLAG=TRUE |

| END FOR |

| END |

3. Results

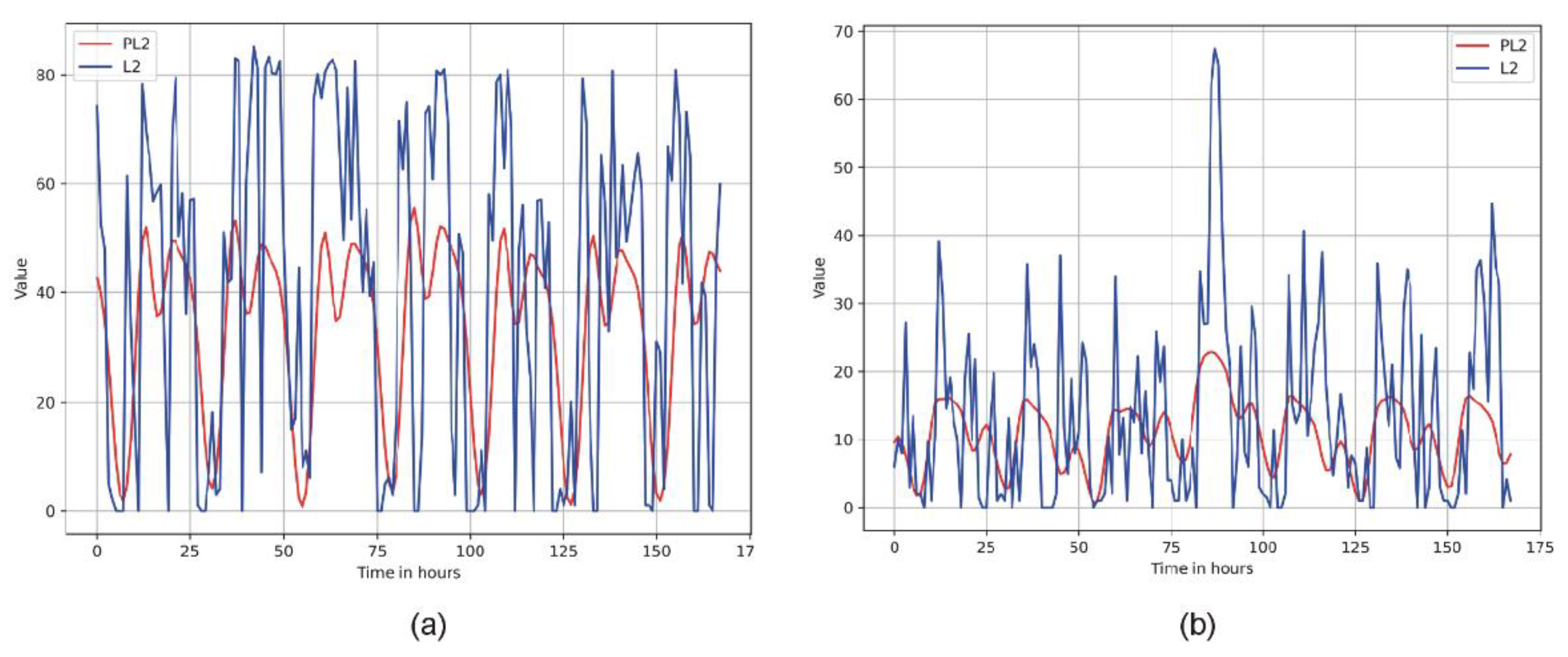

3.1. Selecting the Forecasting Model

3.2. Detecting Point Mobility Anomalies

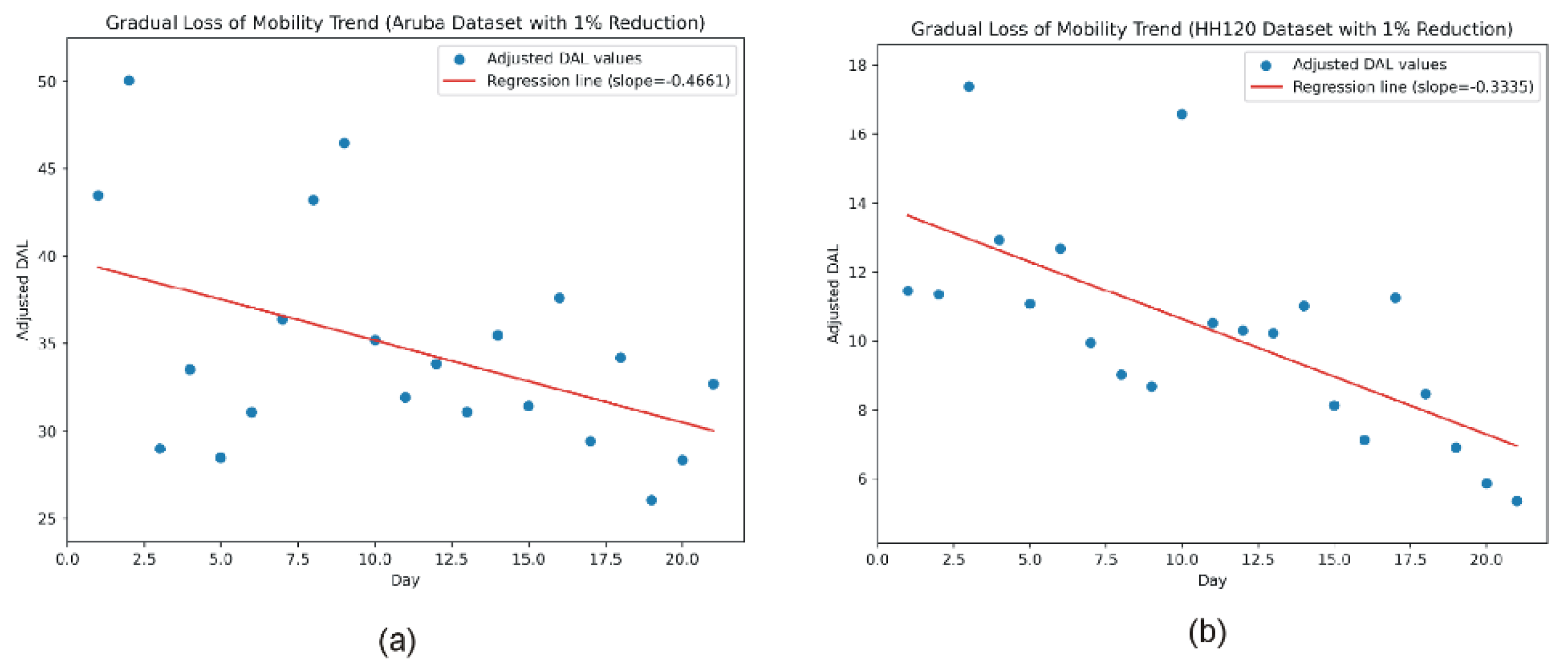

3.3. Detecting Gradual Decline in Mobility

4. Discussion

- The number and placement of sensors have a major influence on system performance. Interestingly, the presence of additional sensors in the Aruba testbed did not necessarily lead to better detection outcomes. In fact, when sensors within a single BMP reported a high number of events per hour, challenging spikes were created that proved difficult to predict, thereby reducing the overall predictive accuracy as measured by RMSE. Additional filtering methods during the preprocessing phase could mitigate these spikes, reduce sensor noise, and consequently improve predictive accuracy. Nevertheless, a minimal redundancy in sensor count is beneficial, as it ensures remarkable robustness against sensor faults. During testing, we removed one sensor from each BMP without noticeably affecting anomaly detection accuracy.

- Prediction accuracy is critical for overall system performance, thus the selection of the Prophet model not definitive. The Prophet model does demonstrate strong performance in capturing daily and weekly seasonality and robustness in handling outliers. However, alternative predictive models capable of managing multivariate inputs might yield even better results.

- Although the observed detection rate for point mobility anomalies (prolonged inactivity) was modest (approximately 77–81%), it is important to note that the system outputs a probability of anomaly (PA) rather than a simple binary flag. The tunable threshold for PA significantly influences detection performance. For example, lowering the anomaly probability threshold from 0.7 to 0.65 increased the detection rate to approximately 92% for the Aruba dataset, albeit with a concurrent rise in the false positive rate to about 20%. Proper tuning, tailored to the specific routine of the monitored individual and the sensor distribution, ensures an optimal trade-off between detection sensitivity and false positive rate.

- Another area with considerable potential for improvement is the fuzzy inference system employed in this study. The current configuration is the simplest possible, comprising only three fuzzy domains with linear membership functions and minimal tuning. Introducing additional fuzzy domains and personalized tuning for specific individuals is likely to yield enhanced anomaly detection outcomes.

- The selection of a one-hour time interval for constructing time series from sensor events is arbitrary and directly influences the system's latency. Future research should examine the impact of opting for shorter time intervals. Alternatively, the possibility of defining variable-length “behaviorally significant time intervals” (e.g., sleep time, morning routine, peak activity period, daytime rest, etc.) could be investigated.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitchell, J.A.; Johnson-Lawrence, V.; Williams, E.-D.G.; Thorpe, R. Characterizing Mobility Limitations Among Older African American Men. Journal of the National Medical Association 2018, 110, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, C.S.W.; Lim, W.M.; Teh, P.-L. An Aging and Values-Driven Theory of Mobility. Activities, Adaptation & Aging 2023, 47, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.E.; Kang, Y.; Studenski, S.A.; Degenholtz, H.B. Ability to Walk 1/4 Mile Predicts Subsequent Disability, Mortality, and Health Care Costs. J GEN INTERN MED 2011, 26, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiberger, E.; Sieber, C.C.; Kob, R. Mobility in Older Community-Dwelling Persons: A Narrative Review. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demnitz, N.; Hogan, D.B.; Dawes, H.; Johansen-Berg, H.; Ebmeier, K.P.; Poulin, M.J.; Sexton, C.E. Cognition and Mobility Show a Global Association in Middle- and Late-Adulthood: Analyses from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Gait & Posture 2018, 64, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Demiris, G.; Thompson, H.J. Instruments to Assess Mobility Limitation in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity 2015, 23, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, T.; Thiel, C.; Peter, R.S.; Bahns, C.; Büchele, G.; Rapp, K.; Becker, C.; Grüneberg, C. Association of Clinical Outcome Assessments of Mobility Capacity and Incident Disability in Community-Dwelling Older Adults - a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Preprint 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulos, T.G.; Papastergiou, A.; Mpaltadoros, L.; Nikolopoulos, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. IoT Wearable Sensors and Devices in Elderly Care: A Literature Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Rab, S.; Pratap Singh, R.; Suman, R. Sensors for Daily Life: A Review. Sensors International 2021, 2, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kong, J.; Qu, M.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, C. Progress in Data Acquisition of Wearable Sensors. Biosensors 2022, 12, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, E. Computer Vision-Based Gait Recognition on the Edge: A Survey on Feature Representations, Models, and Architectures. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, C.; Hu, J.; Sayeed, Z.; Qi, J.; Darwiche, H.F.; Little, B.E.; Lou, S.; Darwish, M.; Foote, C.; et al. Computer Vision and Machine Learning-Based Gait Pattern Recognition for Flat Fall Prediction. Sensors 2022, 22, 7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantone, A.A.; Esposito, M.; Perillo, F.P.; Romano, M.; Sebillo, M.; Vitiello, G. Enhancing Elderly Health Monitoring: Achieving Autonomous and Secure Living through the Integration of Artificial Intelligence, Autonomous Robots, and Sensors. Electronics 2023, 12, 3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, G.; Petrucci, G.; Albanesi, B.; De Marinis, M.G.; Piredda, M. Can Smart Home Technologies Help Older Adults Manage Their Chronic Condition? A Systematic Literature Review. IJERPH 2023, 20, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaiyapuri, T.; Lydia, E.L.; Sikkandar, M.Y.; Díaz, V.G.; Pustokhina, I.V.; Pustokhin, D.A. Internet of Things and Deep Learning Enabled Elderly Fall Detection Model for Smart Homecare. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 113879–113888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharghan, S.K.; Hashim, H.A. A Comprehensive Review of Elderly Fall Detection Using Wireless Communication and Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Measurement 2024, 226, 114186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, J.; Carvalho, S.P.; Goncalve, D.; Moreno, J.C.; Santos, C.P. Daily Locomotion Recognition and Prediction: A Kinematic Data-Based Machine Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 33250–33262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennella, C.; Maniscalco, U.; Pietro, G.D.; Esposito, M. A Deep Learning System to Monitor and Assess Rehabilitation Exercises in Home-Based Remote and Unsupervised Conditions. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2023, 166, 107485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.; Lopes, J.M.; Moccia, S.; Berardini, D.; Migliorelli, L.; Santos, C.P. Deep Learning-Based Approaches for Human Motion Decoding in Smart Walkers for Rehabilitation. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 228, 120288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Anomaly Detection: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2009, 41, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momin, M.S.; Sufian, A.; Barman, D.; Dutta, P.; Dong, M.; Leo, M. In-Home Older Adults’ Activity Pattern Monitoring Using Depth Sensors: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayad, M.; Hachani, M.-Y.; Ghoumid, K.; Mostefaoui, A.; Chouali, S.; Picaud, F.; Herlem, G.; Lajoie, I.; Yahiaoui, R. Fall Detection Approaches for Monitoring Elderly HealthCare Using Kinect Technology: A Survey. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casilari, E.; Álvarez-Marco, M.; García-Lagos, F. A Study of the Use of Gyroscope Measurements in Wearable Fall Detection Systems. Symmetry 2020, 12, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Detecting Falls Through Convolutional Neural Networks Using Infrared Sensor and Accelerometer. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Conference on Smart Communities: Improving Quality of Life using AI, Robotics and IoT (HONET), Boca Raton, FL, USA, 4 December 4 2023; IEEE: Boca Raton, FL, USA; pp. 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, S.; Kudo, M.; Nonaka, H. Privacy-Preserved Behavior Analysis and Fall Detection by an Infrared Ceiling Sensor Network. Sensors 2012, 12, 16920–16936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Cui, Z.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M. Robust Fall Detection in Video Surveillance Based on Weakly Supervised Learning. Neural Networks 2023, 163, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, K.; Sugiura, Y.; Hasegawa, K.; Saito, H. Gait Measurement at Home Using a Single RGB Camera. Gait & Posture 2020, 76, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, G.; Dendou, T. Analysis of Foot-Pressure Data to Classify Mobility Pattern. International Journal on Smart Sensing and Intelligent Systems 2014, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherf, L.; Kirchbuchner, F.; Von Wilmsdorff, J.; Fu, B.; Braun, A.; Kuijper, A. Step by Step: Early Detection of Diseases Using an Intelligent Floor. In Ambient Intelligence; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Kameas, A., Stathis, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; Volume 11249, pp. 131–146. ISBN 978-3-030-03061-2. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Zheng, J.; Yu, L.; Zhang, R.; He, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Adjustable Method for Real-Time Gait Pattern Detection Based on Ground Reaction Forces Using Force Sensitive Resistors and Statistical Analysis of Constant False Alarm Rate. Sensors 2018, 18, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhao, W.; Wang, W. Detecting Dementia-Related Wandering Locomotion of Elders by Leveraging Active Infrared Sensors. JCC 2018, 06, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Yang, H. Multi-Scale Graph Modeling and Analysis of Locomotion Dynamics towards Sensor-Based Dementia Assessment. IISE Transactions on Healthcare Systems Engineering 2019, 9, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, E.; Borras, F.; Casino, F.; Solanas, A. A Study on the Detection of Wandering Patterns in Human Trajectories. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications (IISA), Corfu, Greece, July 2015; IEEE, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q.; Zhang, D.; Huang, X.; Ni, H.; Zhou, X. Detecting Wandering Behavior Based on GPS Traces for Elders with Dementia. In Proceedings of the 2012 12th International Conference on Control Automation Robotics & Vision (ICARCV), Guangzhou, China, December 2012; IEEE, 2012; pp. 672–677. [Google Scholar]

- Dentamaro, V.; Gattulli, V.; Impedovo, D.; Manca, F. Human Activity Recognition with Smartphone-Integrated Sensors: A Survey. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 246, 123143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, A. Mining Changes in Mobility Patterns from Smartphone Data. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communication Workshops (PerCom Workshops), Sydney, Australia, March 2016; IEEE, 2016; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bieber, G.; Luthardt, A.; Peter, C.; Urban, B. The Hearing Trousers Pocket: Activity Recognition by Alternative Sensors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Pervasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, Heraklion Crete Greece, 25 May 2011; ACM, 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, M.; Binas, M.; Jakab, F. Unobtrusive Anomaly Detection in Presence of Elderly in a Smart-Home Environment. In Proceedings of the 2012 ELEKTRO, Rajeck Teplice, Slovakia, May 2012; IEEE, 2012; pp. 341–344. [Google Scholar]

- Eisa, S.; Moreira, A. A Behaviour Monitoring System (BMS) for Ambient Assisted Living. Sensors 2017, 17, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshtaghi, M.; Zukerman, I.; Russell, R.A. Statistical Models for Unobtrusively Detecting Abnormal Periods of Inactivity in Older Adults. User Model User-Adap Inter 2015, 25, 231–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Wahl, F. Emergency Detection in Smart Homes Using Inactivity Score for Handling Uncertain Sensor Data. Sensors 2024, 24, 6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susnea, I.; Pecheanu, E.; Sandu, C.; Cocu, A. A Scalable Solution to Detect Behavior Changes of Elderly People Living Alone. Applied Sciences 2021, 12, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muurling, M.; Au-Yeung, W.-T.M.; Beattie, Z.; Wu, C.-Y.; Dodge, H.; Rodrigues, N.K.; Gothard, S.; Silbert, L.C.; Barnes, L.L.; Steele, J.S.; et al. Differences in Life Space Activity Patterns Between Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment Living Alone or as a Couple: Cohort Study Using Passive Activity Sensing. JMIR Aging 2023, 6, e45876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, J.; Ureña, J.; Hernández, Á.; Gualda, D. Assessing Human Activity in Elderly People Using Non-Intrusive Load Monitoring. Sensors 2017, 17, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turimov Mustapoevich, D.; Kim, W. Machine Learning Applications in Sarcopenia Detection and Management: A Comprehensive Survey. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.; Jimison, H.B.; Wactlar, H.D.; Hayes, T.L.; Barkis, W.; Skapik, J.; Kaye, J. The Role of Technology and Engineering Models in Transforming Healthcare. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 6, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fährmann, D.; Martín, L.; Sánchez, L.; Damer, N. Anomaly Detection in Smart Environments: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 64006–64049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Qu, Z.; Blumm, N.; Barabási, A.-L. Limits of Predictability in Human Mobility. Science 2010, 327, 1018–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Cook, D.J.; Fischer, T.R. The Indoor Predictability of Human Mobility: Estimating Mobility With Smart Home Sensors. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Topics Comput. 2023, 11, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberdi Aramendi, A.; Weakley, A.; Aztiria Goenaga, A.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M.; Cook, D.J. Automatic Assessment of Functional Health Decline in Older Adults Based on Smart Home Data. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2018, 81, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASAS - Center for Advanced Studies in Adaptive Systems, Washington State University Activity Recognition Datasets. Available online: https://data.casas.wsu.edu/download/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).Susnea, I.; Dumitriu, L.; Talmaciu, M.; Pecheanu, E.; Munteanu, D. Unobtrusive Monitoring the Daily Activity Routine of Elderly People Living Alone, with Low-Cost Binary Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 2264. [CrossRef]

- Susnea, I.; Dumitriu, L.; Talmaciu, M.; Pecheanu, E.; Munteanu, D. Unobtrusive Monitoring the Daily Activity Routine of Elderly People Living Alone, with Low-Cost Binary Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidl, S.; Wenig, P.; Papenbrock, T. Anomaly Detection in Time Series: A Comprehensive Evaluation. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2022, 15, 1779–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-García, A.; Conde, A.; Mori, U.; Lozano, J.A. A Review on Outlier/Anomaly Detection in Time Series Data. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mobility anomaly | Sensors used | References |

|---|---|---|

| Falls | Depth sensors | [21,22] |

| Accelerometers, gyroscopes | [23] | |

| Passive Infrared (PIR) and accelerometer | [24,25] | |

| Video | [26] | |

| Gait anomalies | RGB camera | [27] |

| Pressure sensors in smart insoles | [28] | |

| Pressure/force sensors in smart floors | [29,30] | |

| Wandering and erratic walking in dementia | Active infrared sensors | [31] |

| Ambient beacons and wearable transponder | [32] | |

| GPS | [33,34] | |

| Prolonged inactivity | Smartphone sensors | [35,36] |

| Microphone+accelerometer | [37] | |

| Passive infrared (PIR) sensors | [38,39,40,41] | |

| Slow loss of mobility due to chronic conditions | Passive infrared (PIR) sensors | [42,43] |

| Electric power load | [44] | |

| Sarcopenia related mobility anomalies | Smartwatch sensors | [45] |

| Observed activity level (OAL) | Euclidean distance between the observed and predicted vectors (Dist) | Probability of mobility anomaly (PA) |

|---|---|---|

| LOW | LOW | MEDIUM |

| LOW | MEDIUM | MEDIUM |

| LOW | HIGH | HIGH |

| MEDIUM | LOW | LOW |

| MEDIUM | MEDIUM | MEDIUM |

| MEDIUM | HIGH | MEDIUM |

| HIGH | LOW | LOW |

| HIGH | MEDIUM | LOW |

| HIGH | HIGH | LOW |

| Testbed | Model | Short length train dataset (28 days) | Full length train dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aruba | Prophet | 23.67 | 19.47 |

| RF | 19.03 | 19.83 | |

| SVR | 20.78 | 20.16 | |

| SARIMA | 21.36 | 18.39 | |

| VAR | 21.28 | 21.46 | |

| HH120 | Prophet | 7.95 | 7.13 |

| RF | 7.44 | 7.33 | |

| SVR | 8.03 | 7.5 | |

| SARIMA | 8.9 | 7.73 | |

| VAR | 8.53 | 8.14 |

| Dataset | TP | FN | FP | TN | Detection Rate | False Positive Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aruba | 49 | 11 | 56 | 281 | 0.81 | 0.16 |

| HH120 | 28 | 8 | 42 | 295 | 0.77 | 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).