1. Introduction

Brazil has a higher biodiversity and great traditional knowledge about medicinal plants, although rarely Brazilian phytomedicines achieve local or global market [

1]. In this context, “The National Policy and Program of Medicinal Plants and Herbal Medicines” (“Política Nacional de Plantas Medicinais e Medicamentos Fitoterápicos”, PNPMF) has been raised [

2,

3]. To contribute to this public health issue, our group has studied native Brazilian species in randomized and controlled clinical trials

. Achyrocline satureioides inflorescence infusions induced improvements in viral respiratory infection clinical outcomes in an open-label and placebo-controlled clinical trial [

4], validating its traditional use.

In addition, the efficacy of capsules containing

Monteverdia ilicifolia (Mart. ex Reissek) Biral (syn.

Maytenus ilicifolia Mart. ex Reissek), Celastraceae, has been conducted in a clinical trial [

5].

Monteverdia ilicifolia is a shrub native to South America, particularly Argentina, Bolivia, South Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Popularly known as “espinheira-santa”, this species has been extensively used in folk medicine as infusions for treating several gastric disturbances [

6,

7]. It is relevant to mention that although several derivative products of

M. ilicifolia are available on the pharmaceutical market, standardizing the products, formulation, and controlling the chemical markers content is still challenging. Several preclinical evidence reports gastroprotective effects of

M. ilicifolia extracts [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] Preliminary data showed that our capsules with a standardized dry extract from leaves of

M. ilicifolia at 400 or 860 mg are non-inferior to omeprazole, a proton pump inhibitor [

5].

The gastroprotective properties have been related to the presence of secondary metabolites, mainly polyphenols such as catechins and epicatechins in free form or as condensed tannins [

8,

13,

14,

15] and terpenoids [

16,

17]. Baggio and cols. (2007) [

8] reported that a flavonoid fraction from

M. ilicifolia reduced acid hypersecretion, inhibiting the proton pump. Additionally, gastroprotective effects of primary metabolites, particularly polysaccharides (e.g., type II arabinogalactan; acidic heteroxylan; polygalacturonic acid)[

9,

10,

11,

12] have been suggested.

Beyond efficacy evidence, quality and safety must be central in phytotherapy products that require technical-scientific approaches in the production chain, bringing credibility. In this context, while collaborations between industry and academia in Brazil are not straightforward, they have the potential to offer significant benefits. Laboratory data indicates the steps of the procedure to obtain a qualified product to be considered on an industrial scale, generating an intense bridge between research and productive partnerships.

Here, we describe our successful experience developing a phytotherapeutic product transferred to one pharmaceutical industry for scale-up and producing capsules for a clinical trial. This study was the first step of a broader project that aimed to evaluate the potential of an encapsulated standardized dry extract of M. ilicifolia for managing dyspepsia associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. The main goal of the present work was to develop and characterize capsules containing standardized spray-dried extract from leaves of M. ilicifolia. Production was scaled up in one pharmaceutical industry following Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) to achieve a high-quality product for human consumption in the clinical trial. The success of this experience can encourage researchers to perform more clinical trials of Brazilian herbal derivative products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Standards

This study was registered on both systems, the Biodiversity Authorization and Information System – SISBIO (“Sistema de Autorização e Informação em Biodiversidade under number 69,443) and the “National System of Genetic Resource Management and Associated Traditional Knowledge - SISGEN (in portuguese “Sistema Nacional de Gestão do Patrimônio Genético e do Conhecimento Tradicional Associado”, registration number ACE02A1).

2.2. Lab Scale

2.2.1. Materials

All used excipients and chemicals were purchased with pharmaceutical, HPLC, or analytical grades, as appropriate for their application. Êxodo Científica and Sigma-Aldrich supplied the chemical markers pyrogallol and epicatechin. For the Lab Scale, the plant raw material, leaves of Monteverdia ilicifolia, was purchased from Centro Pluridisciplinar de Pesquisas Químicas, Biológicas e Agrícolas of Universidade Estadual de Campinas, CPQBA/UNICAMP (São Paulo, Brazil, geographical coordinates 22S47’27.46”/47W6’41.90). The dried leaves were stored at room temperature and protected from light. The plant material was identified by Dr. Mara Ritter (Departamento de Botânica, UFRGS).

2.2.2. Quantitation of Total Tannins

Total tannins were determined in the

M. ilicifolia raw materials using the Folin–Dennis method described in the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia, 6 ed.[

18]. The method is based on the reaction of extracted components with phosphomolybdotungstic reagent (Folin Ciocalteu

®) and sodium carbonate (29% w/v) followed by absorbance measurement at 760 nm. Two experiments were performed; the first was to evaluate the total phenolic content, and the second was to determine the non-tannin fraction using skin powder as a complexion agent. Pyrogallol was used as a reference substance. The total tannin content was calculated according to equation (1):

where:

TT = total tannin content expressed as pyrogallol % (w/w);

A1 = absorbance measured to total phenolics;

A2 = absorbance measured to non-tannin fraction (adsorbed in skin powder);

A3 = absorbance measured to the reference solution;

m1 = weight (g) of the sample;

m2 = weight (g) of the reference solution.

2.2.3. Quantitation of Epicatechin (HPLC)

The content of the chemical marker epicatechin of

M. ilicifolia was determined by the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method using the analytical method described in the plant monography of the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia 6 ed. [

18]. In brief, the analytical conditions were: reversed phase C18 column (Shim-pack ODS, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; a gradient elution (

Table 1) using water 0,1% of trifluoroacetic acid and acetonitrile for 10 min at room temperature; flow rate 0.8 mL/min; injection volume 20 μL, and detection wavelength at 210 nm.

2.2.4. Preparation of M. ilicifolia aqueous Extract (AE) by Infusion

The dried leaves of M. ilicifolia were comminuted using a knife mill, and the particles with size < 500 mm were selected (Tamis Bertel Indústria Metalúrgica; ABNT/ASTM 35; Tyler/Mesh 32) for preparing an infusion (ratio plant:water, 2:100), for 15 minutes following the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) call (Chamada CNPq/MS/SCTIE/Decit Nº 19/2018 – Fitoterápicos) supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

The mixture was filtered, and the supernatant (aqueous extract, AE), was characterized and concentrated (3.8-fold) using a Büchi Rotaevaporator R-114. The concentrated extract (CE) was stored at -20 °C until spray-dried.

2.2.5. Determination of Dry Residue

To determine the dry residue, samples of 10 mL of the aqueous extract AE or the concentrated extract CE were accurately weighed, transferred to a pre-weighed vessel, and dried at 105 ± 2 °C until the residue showed constant weight. The difference between the empty vessel mass and this one containing the dry residue was expressed for 100 mL of AE or CE (%, m/v). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

2.2.6. Spray-Dried Powder (SDP) Preparation

The drying of the concentrated extract CE was performed by atomization in a Mini Spray-Dryer B-290 (BUCHI

®) with two component nozzle and co-current flow under the following operating conditions: 145°C inlet temperature, 95°C outlet temperature, feed rate, 3 mL/min, and spraying pressure of 2 bar. Blends of corn starch and colloidal silicon dioxide were previously tested as drying excipients at the ratio shown in

Table 2. The yield of processing was the criteria used to select the excipient to produce the M. Ilicifolia spray-dried powder.

2.2.7. Encapsulation of Spray-Dried Powder (SDP)

Encapsulation of M. ilicifolia SDP in transparent hard gelatin capsules size 00 was performed using a manual apparatus to obtain two doses of SDP for the clinical trial, 400 mg and 860 mg.

2.2.8. In Vitro Dissolution Tests

Dissolution tests were carried out in triplicate for the lab scale using USP apparatus 1 (Nova Ética, Brazil) under predetermined sink conditions. Dissolution tests were performed with 150 mL of dissolution acidic medium (0.1 N HCl, pH 2.0) or with phosphate buffer pH 6.8 media, at 37°C ± 0.2°C, and shaken at 50 rpm. Each capsule was trapped in a metal basket to avoid floating. At predetermined sampling intervals (15 min) over 120 min, samples of 1 mL of samples were withdrawn from the dissolution medium and filtered through a 0.45 μm PVDF membrane. Epicatechin was quantified in the supernatant following the HPLC method described in section 2.2.4. After 120 min, the acidic dissolution medium was replaced by pH 6.8 phosphate buffer medium, and the experiment was performed for another 120 min. A fresh medium replaced the volume withdrawn after each sampling.

2.3. Semi-Industrial Production

After the technological development on a laboratory scale, the technology was transferred to Sustentec Produtores Associados (Pato Bragado, Paraná State, Brazil) for scale up, to produce SDP powder and gelatin capsules according to good manufacturing practices. Capsules were produced to obtain omeprazole 20, positive control, and two SDP doses, 400 and 860 mg, to be used in the clinical trial.

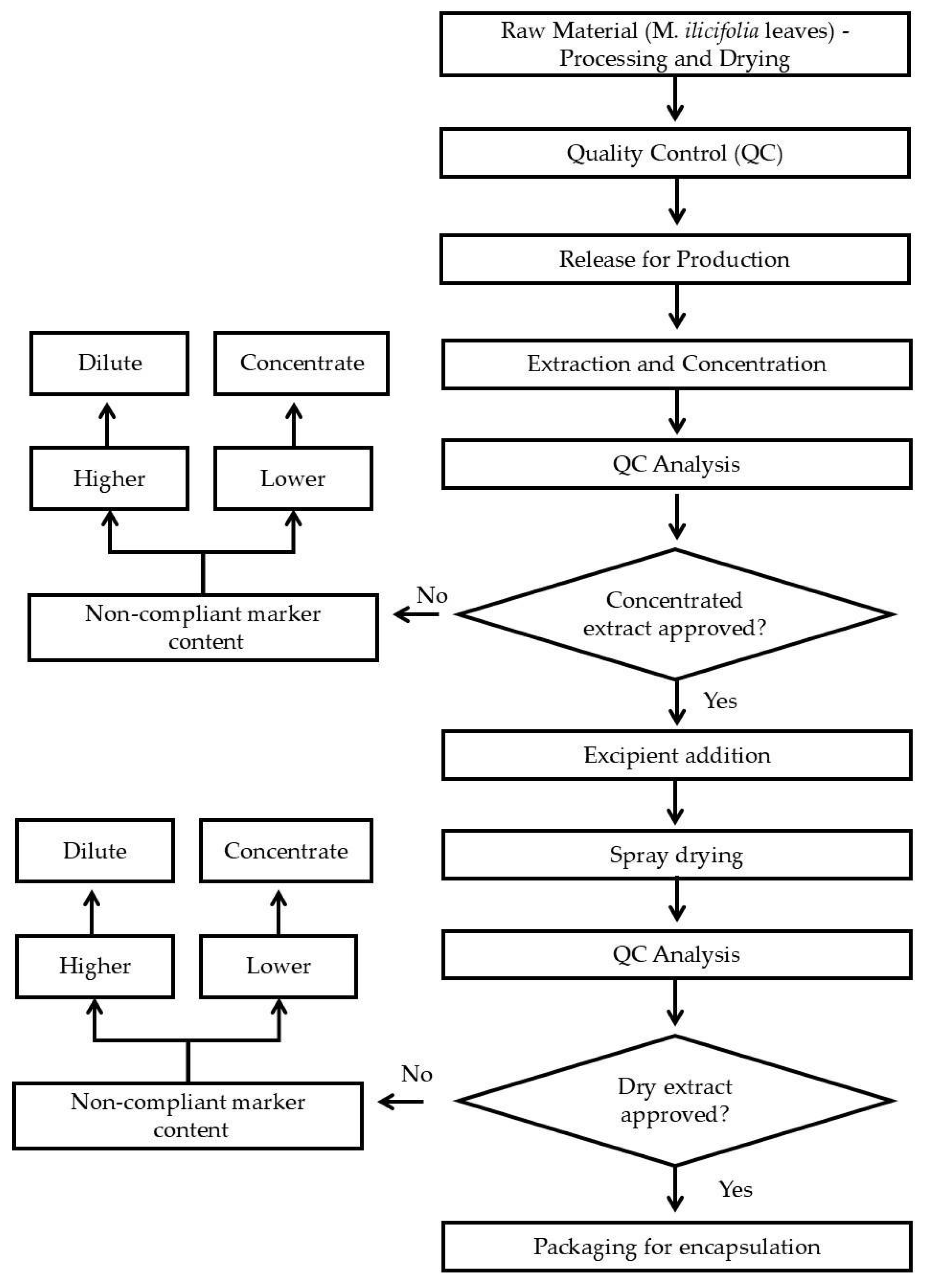

Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the dry extract production process.

2.3.1. Plant Material

The herbal raw material was provided by CHAMEL Ind. Prod. Nat. Ltd.a (CNPJ: 15.222.519/0001-91). It was characterized following the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia, 6. ed. [

19]

2.3.2. Quality Control

Microbiological quality control was performed, specifically about aerobic and mesophilic bacteria, fungal, Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. Heavy metals, lead, arsenic, cadmium and mercury, and pesticide residues were evaluated. Total tannins and epicatechin content were quantified as described for the lab scale.

2.3.3. Preparation and Concentration of Aqueous Extract (AE)

The herbal raw material was comminuted in a Hammer Mill (Mod DPC-2, Cremasco®) to obtain a fine powder. This plant powder was extracted with water by dynamic maceration – mechanical agitation at 95ºC for 4h. The aqueous extract (AE) was filtered (Vacuum filter, REMID®) and concentrated in a falling film evaporator (Mod 220 E, INCAL®) to obtain a concentrated extract (CE) with dry residue of 25-30%.

2.3.4. Spray-Dried Powder (SDP) Production on a Semi-Industrial Scale

A blend of the adjuvants starch:colloidal silicon dioxide (9:1) was added to the CE in a proportion of 30% of the dry residue mass (dry residue:adjuvant ratio 7:3). This mixture was dried in an industrial spray-dryer (Mod SPD-001, Remid®) under the same conditions described in section 2.2.6. The process steps were validated following good manufacturing practices for drugs, following international process validation guidelines recommended by current Brazilian legislation.

2.3.5. Encapsulation

Encapsulation tests of Dry Extract (Batch ESA210401 - Density = 0.625) were performed to define the dose to be used in the clinical trial. The tests were performed in a manual encapsulator, with a maximum capacity of 200 capsules in accordance with good handling practices. Gelatin capsule size 0 (zero), Capsugel®, green-white color, was used.

3. Results

Both raw materials (dried leaves) used in both the laboratory and industry scales (respectively CPQBA/UNICAMP and Chamel) were analyzed according to the plant monograph described in Brazilian Pharmacopoeia, 6 ed. [

18]. The following tests, granulometry, macroscopic and microscopic description, foreign matter, humidity, total ashes, chromatographic profile, heavy metals, pesticide residues, aerobic and mesophilic bacteria, yeast-mold,

Escherichia coli and

Salmonella spp were performed to raw material and SDP (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of Monteverdia ilicifolia raw material (Chamel) and SDP obtained on a semi-industrial scale.

Table 2.

Analysis of Monteverdia ilicifolia raw material (Chamel) and SDP obtained on a semi-industrial scale.

| Criteria |

Specification |

|

| Raw Material |

SDP |

| Aspect |

ANVISA (2019) |

Fine greenish/yellowish powder, odorless, slightly bitter, and astringent. |

Fine, hygroscopic, homogeneous powder, dark brown in color, with a characteristic odor and flavor. |

| Microscopic description |

Raw material: ANVISA (2019) |

The stomata are laterocytic, and the epidermal cells on both surfaces of the lamina are polygonal, with varying dimensions and straight anticlinal walls, being larger on the adaxial surface. In cross-section, an unstratified epidermis with thickened walls is observed, covered by a thickened cuticle layer forming a cuticular flange. Epidermal cells contain small styloids (in young leaves) or rectangular prismatic crystals (in mature leaves), both composed of calcium oxalate. |

- |

| Solubility |

Water soluble |

- |

compliant |

| Foreign matter |

2.0 % max. |

0.04% |

- |

| Humidity |

Raw material:

12.0 % max.

SDP: 6.0 % max. |

5.08 % |

1.82 % |

| Total ashes |

8.0 % max. |

3.84 % |

- |

| Granulometry |

Raw material:

80 % max < 28 mesh

SDP: 90 % min ≤ 80 mesh |

72.82 % |

99.95 % |

| Density |

0.40 – 0.800 g/mL |

- |

0.625 g/mL |

| pH (10% sol.) |

5.0 – 6.0 |

- |

5.19 |

| Chromatographic profile |

Raw material: Burgundy-colored spot with an approximate Rf of 0.82 in the sample, corresponding to the epicatechin standard, and the appearance of another burgundy band with an Rf of 0.72 just below the epicatechin |

compliant |

compliant |

| Heavy metals |

Lead: max. 5.0 ppm

Cadmium: max. 1.0 ppm

Mercury: max. 0.1 ppm

Arsenic: max. 5.0 ppm |

< 0.011

< 0.001

< 0.001

< 0.001 |

< 0.011

< 0.001

< 0.001

< 0.001 |

| Pesticide residues |

Absence |

0.00 mg/Kg |

absence in raw material |

| Total mesophilic aerobic bacteria |

Raw material:

Max. 105 UFC/g

SDP: Max. 104 UFC/g |

3.4 x 104 UFC/g |

<1,0 x 101 UFC/g |

| Yeast-mold |

Raw material:

Max. 103 UFC/g

SDP: Max. 102 UFC/g |

2.27 x 102 UFC/g |

2,0 x 101 UFC/g |

| E. coli |

Absent in 1 g |

complaint |

complaint |

|

Salmonella spp |

Absent in 10 g |

complaint |

complaint |

Total tannins content

(Folin Denis, BRASIL, 2019) |

Raw material:

min 2.0 % (w/w)

SDP: 5.52 – 7.47% (6.5 ± 15.0%) (w/w) |

3.27 % (w/w) |

ND) |

Epicatechin content

(HPLC, BRASIL, 2019) |

Raw material:

min 0.28 % (w/w)

SDP: min 2.8 % (w/w) |

0.683 % (w/w) |

2.91 % (w/w) |

The total tannin content of raw materials was determined using the Folin-Dennis method [

18]. Concentrations of 2.13 ± 0.19 % (w/w) and 3.27 ± 0.02 % (w/w) were observed in raw materials used for, respectively, CPQBA/UNICAMP (for lab scale) and Chamel Ltd.a. (for semi-industrial scale) raw materials. Therefore, both raw materials followed the official monograph requirement of a minimum of 2.0 %, w/w.

The quantitation of epicatechin in

M. ilicifolia raw material and derivative products was assessed by HPLC using the analytical conditions described in the official monograph for the species [

18]. The concentrations of epicatechin in the raw materials from CPQBA/UNICAMP and Chamel were, respectively, 1.34 ± 0.16 % (w/w) and 0.683 ± 0.03 % (w/w), both following the official monograph requirements of minimum 0.28% (w/w) [

18]. The Chamel met the quality requirements of Brazilian legislation to supply raw materials for herbal medicines, which is why it was chosen as the supplier for producing capsules on a semi-industrial scale for clinical trials.

In the Lab scale, the AE contained 0.55 % (w/v) dry residue with 0.0267 ± 0.016 % (w/v) of epicatechin. The AE was concentrated 3.85-fold, increasing the dry residue to 2.12 % (w/v) before drying. The resultant solution was named concentrated extract (CE). The content of the chemical marker epicatechin in SDP was 2.91 ± 0.72 % (w/w), quantified by HPLC. The SDP was used to prepare the hard gelatin capsules, and dissolution tests were performed.

Two doses of SDP were tested in the clinical trial, 400 and 860 mg. However, the volume of the SDP did not meet only one hard gelatin capsule. Interestingly, on a Lab scale, 860 mg of SDP (70% dry residue and 30% of excipients) fulfilled three capsules 00 while, on a semi-industrial scale, it was possible to achieve three capsules no 0. Even the dry residue:excipient ratio has been the same in both scales, the more concentration of dry residue in CE and the different configuration of the spray dryer apparatus can explain the powder differences.

Moreover, clinical trials require all patients from different groups to receive the same number of capsules, independently of the tested dose. Considering the volume of 860 mg of spray-dried powder met three capsules no 0 (semi-industrial scale), all treatments, omeprazole, 400, and 860 mg of SDP were administered as three capsules size 0. The 400 mg of SDP dose corresponded to three capsules containing 133.3 mg of SDP each. The 860 mg of SDP dose corresponded to three capsules containing 286.7 mg of SDP each. Each dose of 400 mg of SDP contained 11.6 mg of epicatechin, and each dose of 860 mg of SDP contained 25,0 mg of epicatechin.

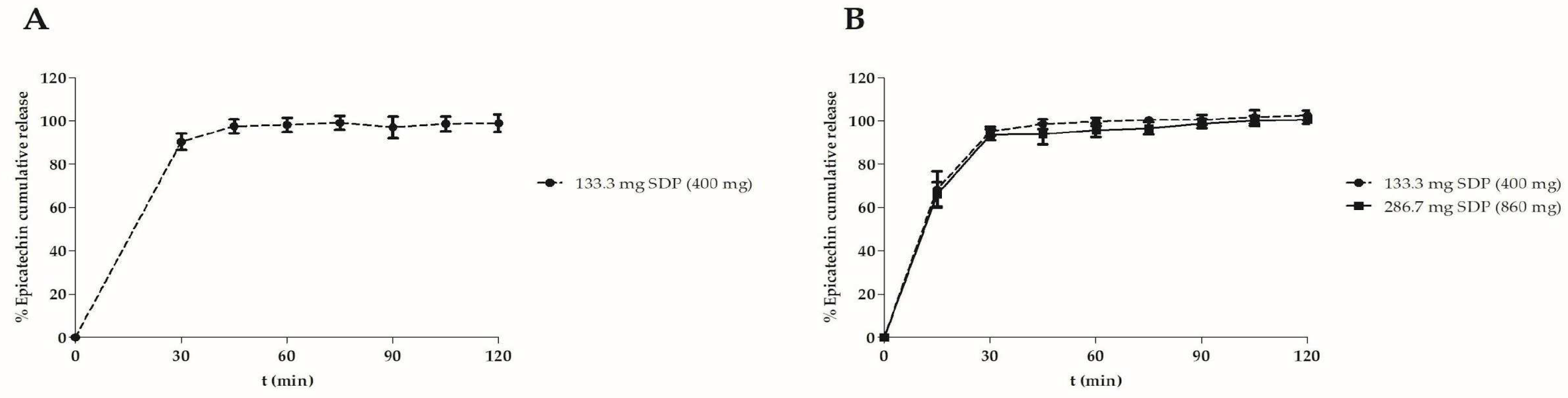

Figure 2 shows the dissolution profile of the capsules containing the

M. ilicifolia dried extract expressed in epicatechin released from capsules prepared in laboratory (A) and semi-industrial scales (B).

Figure 2 A reveals that the capsules prepared on lab and semi-industrial scales showed similar released profiles. In an acidic medium (0.1 N HCl, pH 2.0), they released about 85% of the epicatechin in 2 hours. When a pH 6.8 phosphate buffer replaced the medium, the epicatechin release reached around 100% in the subsequent two hours. This release profile, combined with the results from clinical trials can serve to design new formulations in the future.

The weight variation, epicatechin content, content uniformity, and disintegration tests of the capsules were performed for the capsules produced on an industrial scale, and the results are shown in

Table 3.

Table 3.

Characterization of the hard gelatin capsules containing spray-dried powder of M. ilicifolia produced on a semi-industrial scale.

Table 3.

Characterization of the hard gelatin capsules containing spray-dried powder of M. ilicifolia produced on a semi-industrial scale.

| Capsules |

133.3 mg SDP |

286.7 mg SDP |

| Weight variation (%) |

< ± 7.5% |

< ± 7.5% |

| Epicatechin content (mg/capsule) |

3.39 ± 0.12 |

5.56 ± 0.17 |

| Content uniformity |

96.15%,

AV= 10.23% |

93.45%,

AV= 11.99 % |

| Disintegration time |

< 30 min |

< 30 min |

4. Discussion

Our partial clinical findings showed that our capsules containing both doses, 400 and 860 mg of spray dried extract of

M. ilicifolia used twice a day, had similar effects to omeprazole regarding GERD symptoms intensity and their impacts on life quality [

5]. This study is a part of a broader project designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of

M. ilicifolia capsules.

This work can contribute to Brazilian public policies of herbal medicines, such as The National Policy and Program of Medicinal Plants and Herbal Medicines (“Política Nacional de Plantas Medicinais e Medicamentos Fitoterápicos”, PNPMF) as described above.

Even with our biodiversity and traditional/popular knowledge of medicinal plants, herbal medicines have little relevance in the context of the qualified medicinal market in our country. The Brazilian academia has focused on preclinical studies regarding efficacy and safety of medicinal plants, there are clear research gaps between preclinical and clinical studies and rarely our medicinal plants and/or their products are evaluated in clinical trials, what could bring stronger evidence of 100% Brazilian phytomedicines, enabling to achieve both local or global market [

1].

To bridge these gaps, governmental or private funding supporting effective preclinical and clinical projects and, consequently, this public health policy and a strong academic and industry partnership is essential. Following Carvalho and colleagues (2011)[

2], the whole production chain of herbal medicines must provide products with quality, safety, and efficacy. For this ambitious goal, all players, including the government, university, and industry, as well as the whole productive chain, must collaborate to create a cooperative network. This project is a successful case that culminated in clinical data on

M. ilicifolia effects, following safety and quality criteria, where the government, specifically the Minister of Health, acted as a promoter/initiator with a specific Call for this species (through our public research agency, CNPq). Academia generated relevant insights and data, for example, laboratory data for a scale-up approach guided technology development procedures in an industry environment at a bigger scale and following GMP and safety, creating exclusion criteria for our clinical trial that might be considered as contraindication after further studies to confirm the potential hepatotoxicity effect.

We have also tried to generate evidence-based phytotherapy of traditionally/popularly used native Brazilian species, such as the infusions of

Achyrocline satureioides inflorescences that were evaluated on symptoms of viral respiratory infections in a randomized, open-label, placebo-controlled clinical trial [

4], bringing evidence-based validation for the traditional use. We estimate that these approaches can bring innovative social and economic growth.

Firstly, the potential pharmacokinetic interaction with cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, specifically CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, and hepatotoxicity of aqueous extract of

M. ilicifolia were investigated. Our preliminary results indicated potential hepatotoxicity and interaction of

M. ilicifolia extract and compounds with CYP2D6, in order to avoid herbal medicine-drug interactions caused by the co-administration and increase their safety and effectiveness, patients who used chronically CYP2D6 substrates were not included. This is a relevant issue what can be realized by the fact of in 2020 the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a guideline entitled “In vitro Drug Interaction Studies-Cytochrome P450 Enzyme- and Transporter-Mediated Drug Interactions”, suggesting that in vitro data could represent in vivo predictions and to be considered to design clinical studies [

19]. However, the overall analysis suggested that CYP2D6 results were related to hepatotoxicity instead of direct interaction per se. Considering the potential M. ilicifolia-induced hepatotoxicity, the clinical trial had liver diseases as exclusion criteria and we suggested that this species must be avoided by patients with liver diseases [

20].

As previously reported in da SILVA and colleagues 2024 [

5], our randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial studied two doses of

M. ilicifolia aqueous extract (400 or 860 mg), considering the findings of a small double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted for 28 days that evaluated

M. ilicifolia 400 mg (n=23) comparing with a placebo group (sugar brown capsules, n=10) [

21,

22]. Besides, 860 mg twice a day is a recommendation of the guidelines of national regulatory agencies, specifically ANVISA, described in the Phytotherapeutic Memento - Brazilian Pharmacopoeia [

23]

In 2020, 15 records in the Brazilian pharmaceutical market contained

M. ilicifolia [

24] in different presentations, including plant powder, tinctures or fluid extracts, and capsules. It is relevant to emphasize that despite several derivative products of

M. ilicifolia being available on the pharmaceutical market, standardizing the products, formulation, and controlling the chemical markers content have remained a challenge, especially that marketed as nutraceutics.

Double blind clinical trials require particular development, since different doses, as is the case in the present study 400 and 860 mg of SDP, need similar presentations (three capsules with identical aspects, such as size and color). Moreover, capsules should fulfill the requirements for human consumption, therefore, their production should be carried out observing the GMP. All these aspects were considered in the M. ilicifolia capsules production.

Our research group successfully proposed an innovative study titled “Randomized, double-blind clinical trial of M. ilicifolia as a strategy for treating gastroesophageal reflux”. Here, the development of hard gelatin capsules containing a standardized M. ilicifolia spray-dried powder is reported. The technology was transferred to one pharmaceutical industry that produced the capsules according to the Good Manufacturing Practices, making the clinical trial feasible.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study successfully demonstrated the technological development of an M. ilicifolia spray-dried powder suitable for preparing hard gelatin capsules in the required doses, enabling a clinical trial looking for a new therapeutic application of the plant. This example can encourage researchers and industries to look for new applications for known or new plants, especially in countries with rich biodiversity.

Author Contributions

I.R.S.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, validation, visualization, writing—original draft; G.M.: data curation, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, resources, validation, writing—original draft; S.E.B.: data curation, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, resources, validation, writing—original draft; J.A.Z.: conceptualization, methodology, validation; A.L.: investigation, methodology; M.R.R.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, validation, E.L.C.J.: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft; V.B.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, resources, formal analysis, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq—grant number 405888/2018). I.R.S., J.A.S.Z. and V.L.B received the Researcher Productivity Grant from CNPq.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank ANVISA and Ministério da Saúde (Brazil), for support and comments that improved the project.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDP |

Spray-dried extract |

| CE |

Concentrated Extract aqueous extract |

| AE |

aqueous extract |

| A |

absorbance |

| PNPMF |

National Policy and Program of Medicinal Plants and Herbal Medicines |

| SISBIO |

Biodiversity Authorization and Information System |

| SISGEN |

National System of Genetic Resource Management and Associated Traditional Knowledge |

| TT |

total tannin content |

References

- Dutra, R.C.; Campos, M.M.; Santos, A.R.S.; Calixto, J.B. Medicinal Plants in Brazil: Pharmacological Studies, Drug Discovery, Challenges and Perspectives. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 112.

- Carvalho, A.C.B.; Perfeito, J.P.S.; e Silva, L.V.C.; Ramalho, L.S.; de Oliveira Marques, R.F.; Silveira, D. Regulation of Herbal Medicines in Brazil: Advances and Perspectives. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2011, 47.

- Villas Bôas, G. de K.; Santos, J.P.C. dos; Rezende, M. de A. Política Nacional de Plantas Medicinais e Fitoterápicos Revisitada. Rev. Fitos 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

- Bastos, C.I.M.; Dani, C.; Cechinel, L.R.; da Silva Neves, A.H.; Rasia, F.B.; Bianchi, S.E.; da Silveira Loss, E.; Lamers, M.L.; Meirelles, G.; Bassani, V.L.; et al. Achyrocline satureioides as an adjuvant therapy for the management of mild viral respiratory infections in the context of COVID-19: Preliminary results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, and open-label clinical trial. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.S.; Schunck, R.V.A.; Moraes, M.P.; Corssac, G.B.; Meirelles, G.; Bianchi, S.E.; Targa, L.V.; Bassani, V.; Gonçalves, M.R.; Dani, C.; et al. Pharmacological evaluation of the traditional brazilian medicinal plant Monteverdia ilicifolia in gastroesophageal reflux disease: Preliminary results of a randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Biral, L.; Simmons, M.P.; Smidt, E.C.; Tembrock, L.R.; Bolson, M.; Archer, R.H.; Lombardi, J.A. Systematics of New World Maytenus (Celastraceae) and a new delimitation of the genus. Syst. Bot. 2017, 42. [CrossRef]

- Niero, R.; Faloni de Andrade, S.; Cechinel Filho, V. A Review of the ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of plants of the Maytenus genus. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17. [CrossRef]

- Baggio, C.H.; Freitas, C.S.; Otofuji, G. de M.; Cipriani, T.R.; Souza, L.M. de; Sassaki, G.L.; Iacomini, M.; Marques, M.C.A.; Mesia-Vela, S. Flavonoid-rich fraction of Maytenus ilicifolia Mart. Ex. Reiss protects the gastric mucosa of rodents through inhibition of Both H+,K+-ATPase activity and formation of nitric oxide. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 113, 433–440. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, T.R.; Mellinger, C.G.; de Souza, L.M.; Baggio, C.H.; Freitas, C.S.; Marques, M.C.A.; Gorin, P.A.J.; Sassaki, G.L.; Iacomini, M. Polygalacturonic acid: another anti-ulcer polysaccharide from the medicinal plant Maytenus ilicifolia. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 78, 361–363. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, T.R.; Mellinger, C.G.; de Souza, L.M.; Baggio, C.H.; Freitas, C.S.; Marques, M.C.A.; Gorin, P.A.J.; Sassaki, G.L.; Iacomini, M. Acidic heteroxylans from medicinal plants and their anti-ulcer activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 74, 274–278. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, T.R.; Mellinger, C.G.; De Souza, L.M.; Baggio, C.H.; Freitas, C.S.; Marques, M.C.A.; Gorin, P.A.J.; Sassaki, G.L.; Iacomini, M. A polysaccharide from a tea (Infusion) of Maytenus ilicifolia leaves with anti-ulcer protective effects. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1018–1021. [CrossRef]

- Baggio, C.H.; Freitas C. S.; Twardowschy, A.; dos Santos, A.C.; Mayer, B.; Potrich, F.B.; Cipriani, T.R.; Sassaki, G.L.; Iacomini, M.; Marques, M.C.A.; et al. In Vivo/in vitro studies of the effects of the type ii isolated from Maytenus ilicifolia Mart. Ex Reissek on the gastrointestinal tract of rats. Z. Für Naturforschung C 2012, 67, 405–410. [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Melo, F.; Soares, S.F.; Da Costa, R.F.; Da Silva, C.R.; De Oliveira, M.B.N.; Bezerra, R.J.A.C.; Caldeira-De-Araújo, A.; Bernardo-Filho, M. Effect of the Cymbopogon Citratus, Maytenus Ilicifolia and Baccharis Genistelloides extracts against the stannous chloride oxidative damage in Escherichia coli. 2001; 496, 33-38.

- Vellosa, J.C.R.; Khalil, N.M.; Formenton, V.A.F.; Ximenes, V.F.; Fonseca, L.M.; Furlan, M.; Brunetti, I.L.; Oliveira, O.M.M.F. Antioxidant activity of Maytenus ilicifolia root bark. Fitoterapia 2006, 77, 243–244. [CrossRef]

- Rattmann, Y.D.; Cipriani, T.R.; Sassaki, G.L.; Iacomini, M.; Rieck, L.; Marques, M.C.A.; Da Silva-Santos, J.E. Nitric Oxide-dependent vasorelaxation induced by extractive solutions and fractions of Maytenus ilicifolia Mart ex Reissek (celastraceae) leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 104, 328–335. [CrossRef]

- Itokawa, H.; Shirota, O.; Ikuta, H.; Morita, H.; Takeya, K.; Iitaka, Y. Triterpenes from Maytenus ilicifolia; 1991, 30, 3713-3716.

- Andrade, S.F.; Cardoso, L.G.V.; Carvalho, J.C.T.; Bastos, J.K. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of extract, fractions and populnoic acid from bark wood of Austroplenckia populnea. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 109, 464–471. [CrossRef]

- ANVISA - Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária Farmacopeia Brasileira 2019, Volume 2: II Monografias: Plantas Medicinais, 226–233.

- Lee, J.; Beers, J.L.; Geffert, R.M.; Jackson, K.D. A Review of CYP-Mediated drug interactions: mechanisms and in vitro drug-drug interaction assessment. Biomolecules 2024, 14.

- Danilevicz, C.K.; Pizzolato, L.S.; Bianchi, S.E.; Meirelles, G.; Bassani, V.L.; Siqueira, I.R. Pharmacological evaluation of a traditional brazilian medicinal plant, Monteverdia ilicifolia. Part I - Preclinical Safety Study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 324. [CrossRef]

- Geocze, S.; Vilela, M.P.; Chaves, B.D.R.; Ferrari, A.P.; Arlini, E.A. Tratamento de pacientes portadores de dispepsia alta ou de úlcera peptica com preparaçöes de espinheira-santa (Maytenus ilicifolia) / treatment of patients of high dyspepsia or peptic ulcers with maytenus ilicifolia preparations. Cent. De Medicam. (Bras. ). Estud. De Açäo Antiúlcera Gástrica De Plantas Bras. (Maytevírus Ilicifolia “Espinheira-Santa” E Outras). 1988, 75–87.

- Santos-Oliveira, R.; Coulaud-Cunha, S.; Colaço, W. Revisão da Maytenus ilicifolia Mart. Ex Reissek, Celastraceae. Contribuição Ao Estudo Das Propriedades Farmacológicas. Rev. Bras. De Farmacogn. 2009, 19, 650–660.

- ANVISA - Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária Memento Fitoterápico Da Farmacopeia Brasileira 2016, 1, 1–115.

- ANVISA - Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária Consulta Registro de Medicamentos, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).