1. Introduction

Lung cancer ranks first as the main cause of cancer morbidity in males and has a strong association with previous history of smoking [

1,

2]. Approximately 85% of patients have a group of histological subtypes collectively known as non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts for 50-60% of all cases [

3,

4]. Lung cancer has an overall five-year survival rate of 16.8% due to the limited therapeutic options and high levels tumour metastasis [

5]. Hence, it is important to explore new treatment strategies for lung cancer.

Lithium is an FDA-approved and preferred therapy for treatment of bipolar disorders, manic depression and numerous psychiatric episodes. Patients on lithium experience modulated immune profiles that include increase in white blood cells count which was an observation that could explain these immunoprotective effects that warranted further investigation on its use beyond treatment of bipolar disorders [

6,

7,

8]. Lithium was demonstrated to be selectively cytotoxic against several cancer cell lines such as leukaemia [

9], ovarian [

10] and colorectal [

11] cancers while being safe to normal non-cancerous cells. When compared with traditional anticancer therapies, metal ion treatment can kill tumour cells with elicitation of fewer side effects and less drug resistance [

12]. Lithium also regulates major biological processes such as receptor-mediated signalling, ion transport, inflammatory signalling pathways, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in various immune cell types [

13,

14].

The ROS family are a cluster of highly unstable bioactive molecules that are generated during inflammation and normal cellular metabolism via incomplete reduction of molecular oxygen [

15,

16]. Their overproduction deregulates the antioxidative defence system and is closely associated with various diseases such as cancer [

17]. Likewise, reactive nitrogen species (RNS), the by-products of nitric oxide (NO) metabolism, play an important role in maintaining various physiological functions and contribute to several pathological processes at several levels [

18]. Various chemotherapeutic drugs cause cells to release NO radical, which then induce cytotoxic death of breast, liver, and skin tumours [

19].

The induction of cell death is a critical mechanism for a potent anticancer compound. Apoptosis is a type of cell death that can be triggered by mild cellular injury, intracellular and extracellular signals. As a result of apoptosis induction, the damaged cells are then disposed of in an orderly manner without rupturing the cells and exposing the cellular contents to the extracellular environment [

20,

21]. Apoptosis is regulated by tumour suppressor proteins that includes p53 and the Bcl-2 family of proteins which can be either pro-apoptotic or anti-apoptotic [

22,

23]. Anticancer therapies, such as chemotherapy, mainly induce cell death by causing either G

0/G

1 or G

2/M cell cycle arrest. Regulation over cell cycle entry and exit is critical because cancerous cells do not appropriately respond to cues that trigger the quiescence phase [

24]. Hence there is a need for treatment alternatives that can disrupt and halt the cell cycle of cancerous cells.

In this study, the safety of lithium chloride was tested against the Raw 264.7 cells. Cytotoxicity, reactive oxygen species production, nitric acid production, mode of cell death, cell cycle arrest potential of lithium chloride was evaluated in lung adenocarcinoma (A549) cells treated with A549.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Line and Culture

The lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells (ATCC® CCL-185TM) and Raw 264.7 cells (ATCC® TIB-71™) were maintained in cell culture flasks at 37°C, in a humidified 95% air and 5% CO2 incubator. The A549 cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI-1640) medium (HyClone™, United States) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin/neomycin (PSN) [Gibco, Auckland, New Zealand] and 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Auckland, New Zealand). The Raw 264.7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) [HyClone™, United States], supplemented with 1% PSN (Gibco, Auckland, New Zealand) and 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco, Auckland, New Zealand).

After reaching 80-90% confluency, the cells were washed to remove FBS and trypsinized using 1 mL of 1% trypsin. Trypsin was deactivated by adding culture medium containing FBS. The cells were plated to set up for a specific experimental treatment plan. For an experimental set up, the cells were seeded in a 6 well plate at a concentration of 2×105 cells/mL and incubated overnight in a CO2 incubator. Thereafter, the cells were treated with various concentrations (10, 20, 40, 80, 100 mM) of lithium chloride (LiCl). Non-treated control cells and a positive control treated with 20 μM Curcumin (Sigma, USA) and 10 μg/ml LPS (Sigma, USA) were included in respective experiments.

2.2. Cell Viability Assay

The cytotoxicity of lithium chloride was assessed using the MTT [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay, which evaluates cell viability by measuring the oxidative reduction potential of cells, whose outcomes can be quantified spectrophotometrically as the metabolically active cells reduce the yellow MTT into purple formazan and the intensity of the purple colour is directly proportional to the number of viable cells [

25]. After 24- and 48-hours incubations, the medium was aspirated and 5 mg/ml of MTT (Fluka BioChemika, Switzeriland) for 4 hr incubation. After incubation, 100 μL of DMSO (Saarchem, RSA) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for an hour. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using GloMax Multi microplate reader (Promega, USA).

2.3. Oxidative Stress Assay

The Muse Oxidative Stress reagent is based on dihydroethidium is used to distinguish live ROS negative cells from cells exhibiting ROS. To quench out any residual activity, cells were treated with 0.01% sodium borohydride (in PBS) for 5 min before treatment with lithium chloride. The cells were then harvested and stained with the oxidative stress reagent according to manufacturer’s instructions. The results were then analysed using the Muse® Cell Analyzer (Merck Millipore, Germany).

2.4. DAF2-DA Nitric Oxide Measurement Assay

DAF2-DA (4,5 diaminofluorescein diacetate) is a fluorescein derivative that reacts with an oxidation product of NO to the highly fluorescent triazolofluorescein DAF-2T (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) [

26]. To quench out any residual activity, cells were treated with 0.01% sodium borohydride (in PBS) for 5 min before treatment with lithium chloride. The cells were harvested as mentioned (

2.1.1 above) after 24 hours treatment. The cells were stained with 10 μM/ml DAF2-DA and 10 μg/mL PI (propidium iodide, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The results were viewed using the Muse

® Cell Analyzer (Merck Millipore, Germany).

2.5. Annexin-V and (PI) Apoptosis Detection Assay

Mode of death induced by lithium chloride was determined using the Muse® Annexin V and Dead Cell Kit. As per manufactures manual, the kit is used to differentiate live, apoptotic and dead cells. Muse® Annexin V and Dead Cell Reagent. The samples were harvested and stained for 20 minutes at room temperature in the dark. The results were viewed using the Muse® Cell Analyzer (Merck Millipore, Germany).

2.6. Cell Cycle Arrest Assay

The ability of lithium chloride to induce cell cycle arrest was determined using the Muse® Cell Cycle Kit, which allows for fast quantitative measurements of the percentage of cells in the G0/G1, S and G2/M phases of cell cycle. The A549 cells were treated and harvested as mentioned above. Then stained with the Muse® Cell Cycle Reagent, followed by incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. The results were viewed using the Muse® Cell Analyzer (Merck Millipore, Germany).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All the experiments were done in triplicates in three independent experiments and the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD. The experimental data was analysed using GraphPad Prism Version 6.0 Statistical Software. Statistical significance was determined by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test. The p values less than 0.01 were considered significant (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001).

3. Results

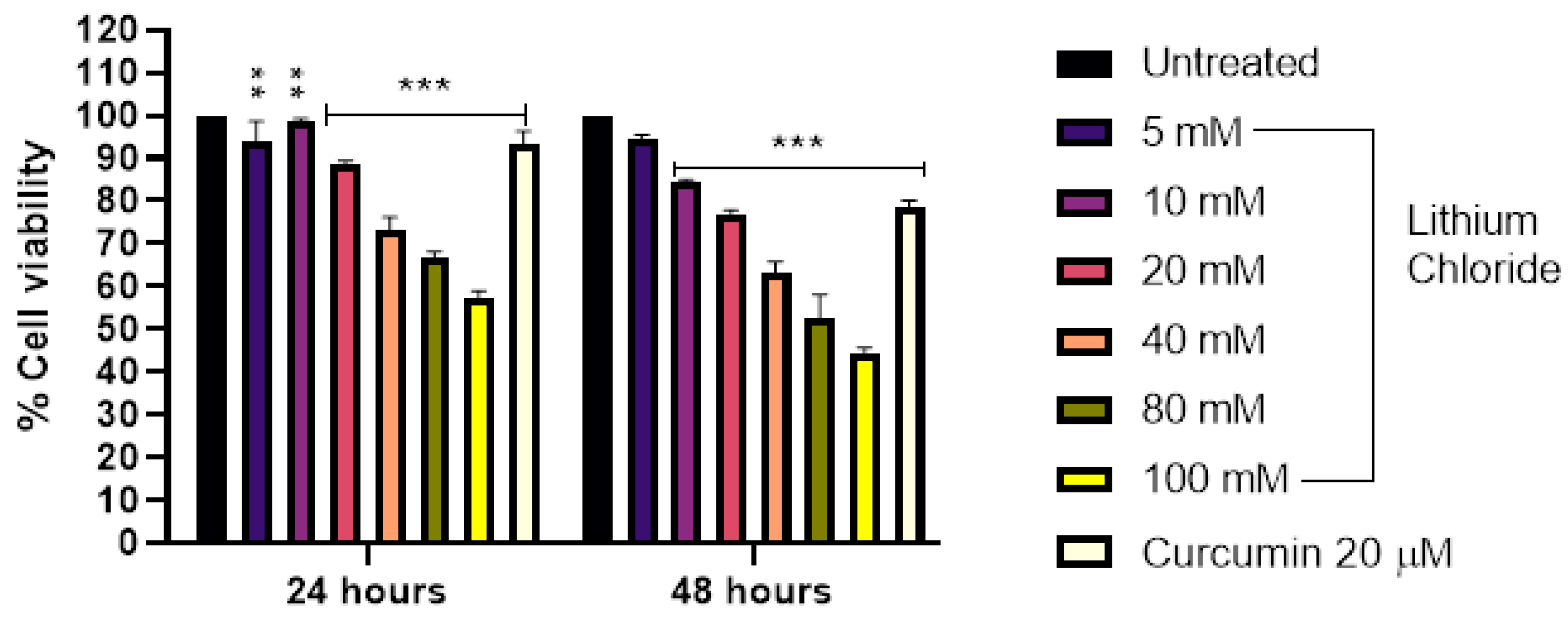

3.1. Cytotoxicity of LiCl in Raw 264.7 Cells

Figure 1 shows that increasing concentrations of lithium chloride result in a gradual decrease in cell viability of Raw 264.7 cells over 24 and 48 hours. At 24 hours, the highest concentration 100 mM reduced cell viability to 57.0%, while the lowest concentration 5 mM had a minimal effect (93.667%). A similar trend was observed at 48 hours, with 100 mM reducing viability further to 44.0%, compared to 94.333% at 5 mM. Curcumin (20 µM) served as a positive control and it maintained higher cell viability compared to most concentrations, showing 93.333% and 78.667% at 24 and 48 hours, respectively. The results demonstrate a dose- and time-dependent cytotoxic effect of LiCl in Raw 264 macrophage cells, with greater reductions in cell viability observed at higher concentrations and longer exposure times.

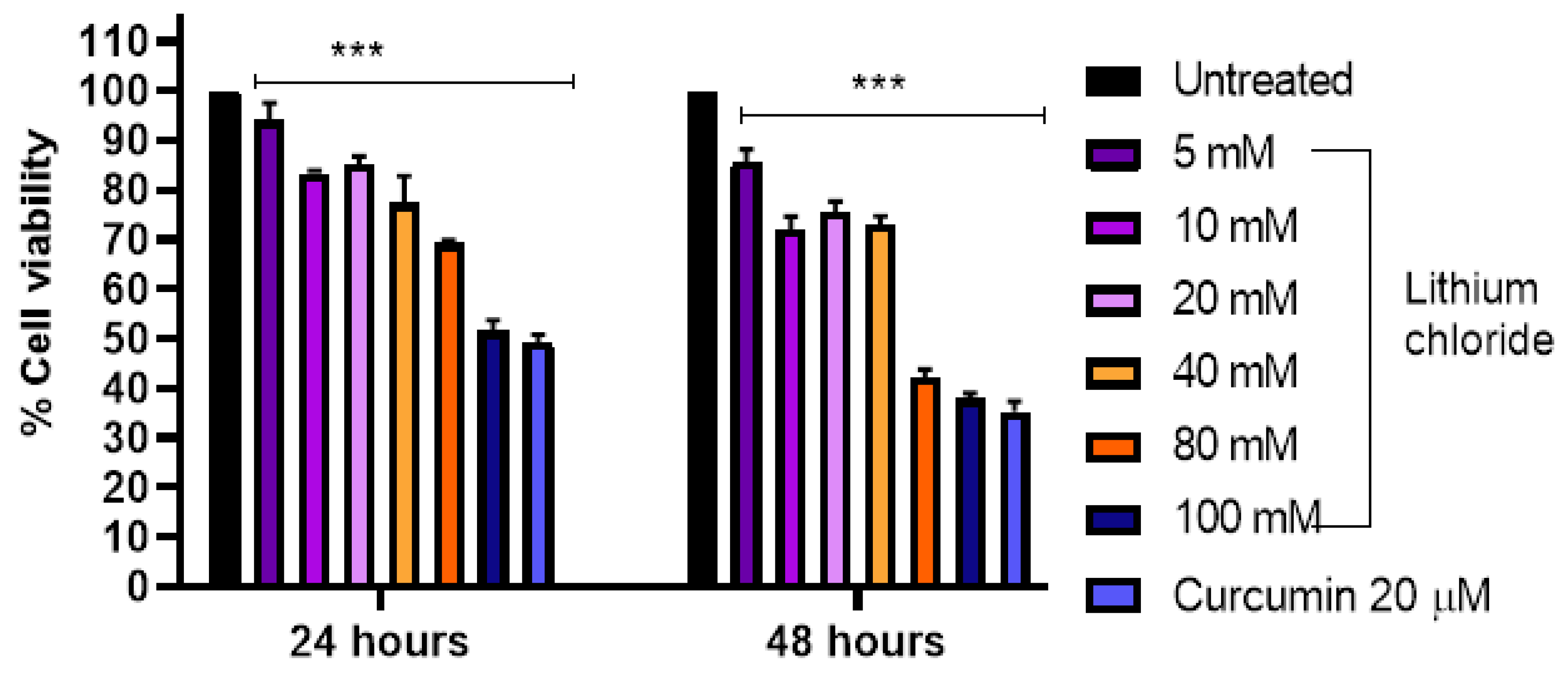

3.3. Effect of LiCl on the Cell Viability of A549 Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells

Figure 2 illustrates a dose- and time-dependent reduction in cell viability following treatment with LiCl in A549 cells. At 24 hours, cell viability declined gradually with increasing concentrations from 94.0% at 5 mM to 51.667% at 100 mM. A similar trend was observed at 48 hours, but with more pronounced effects, as viability dropped to 85.667% at 5 mM and as low as 38.0% at 100 mM. Notably, curcumin (20 µM) exhibited significant cytotoxic effects, with cell viability of 49.333% at 24 hours and 35.333% at 48 hours. Overall, the results demonstrate that both LiCl and curcumin reduce cell viability in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, with higher doses and longer exposure times leading to greater cytotoxicity in A549 cells.

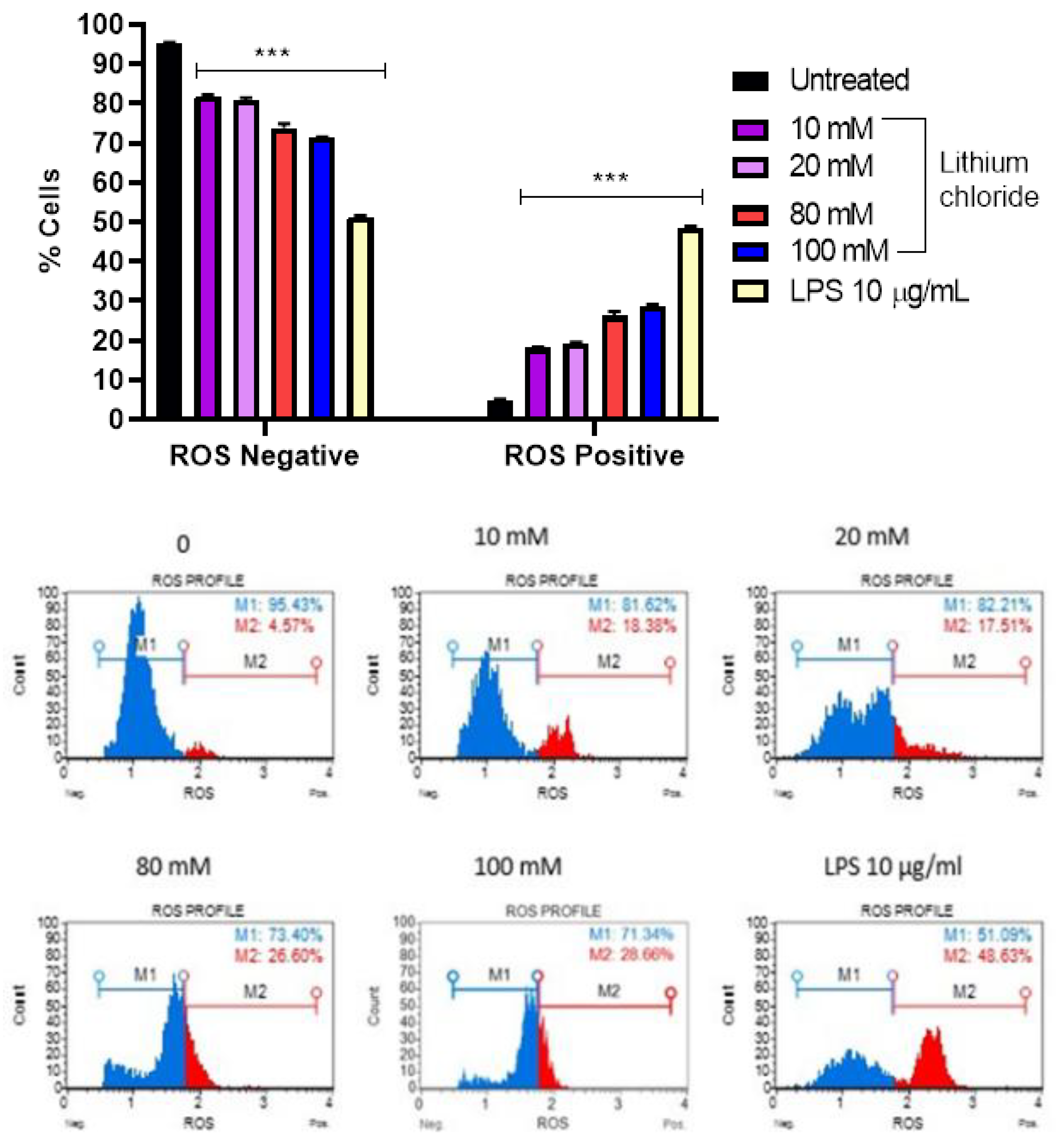

3.3. Effect of Lithium on the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in A549 Cells

Figure 3 reveals a concentration-dependent increase in ROS-positive cells with increasing concentrations of LiCl. In the untreated control, the majority of cells were ROS-negative (95.170%), with only 4.830% being ROS-positive. Treatment with 10 mM and 20 mM LiCl increased the ROS-positive population to 18.067% and 19.043%, respectively. Higher concentrations of 80 mM and 100 mM further elevated ROS-positive cells to 26.200% and 28.727%, respectively, indicating a clear trend of elevated oxidative stress in A549 cells. LPS (10 µg/mL), used as a positive control, caused the most significant increase in ROS-positive cells (48.470%), demonstrating its strong pro-oxidative effect. These results suggest that LiCl induces oxidative stress in a dose-dependent manner, as evidenced by the increase in ROS-positive cells, although its effect is less pronounced than that of LPS. This shows that LiCl contributes to cellular ROS generation at higher concentrations.

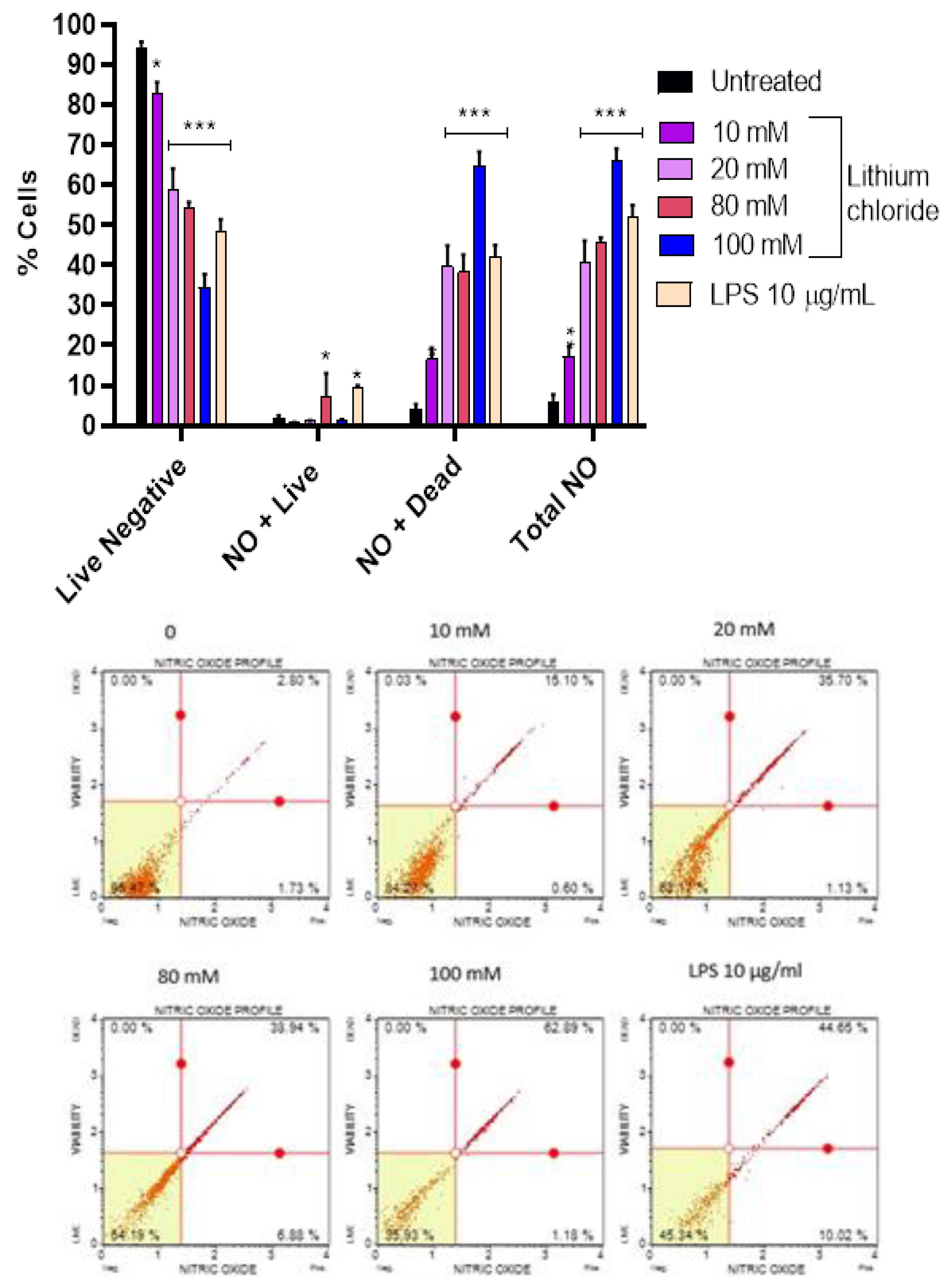

3.4. Effect of Lithium on Production of Nitric Oxide in A549 Cells

Figure 4 shows that LiCl induces a dose-dependent increase in nitric oxide (NO) production and NO-associated cell death in A549 cells. In the untreated control, the majority of cells were live and NO-negative (93.977%), with only 6.023% total NO-positive cells. Treatment with 10 mM and 20 mM LiCl resulted in a substantial reduction in live NO-negative cells (82.840% and 58.980%, respectively) and an increase in dead NO-positive cells (16.540% and 39.680%). At higher concentrations (80 mM and 100 mM), the percentage of live NO-negative cells continued to decline (54.353% and 34.367%, respectively), while dead NO-positive cells rose dramatically, peaking at 64.563% at 100 mM. The total NO-positive population reached 65.970% at 100 mM, indicating robust NO production and associated cytotoxicity. LPS (10 µg/mL), used as a positive control, also increased NO-positive cells (51.753% total NO-positive), with a higher proportion of dead NO-positive cells (42.257%), supporting its role as a potent inducer of NO production and cell death. These findings suggest that LiCl stimulates NO production in a dose-dependent manner, leading to increased cell death, primarily through NO-mediated cytotoxicity. The effects of LiCl are comparable to LPS at higher concentrations, indicating its significant role in inducing oxidative stress and cell death as seen in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

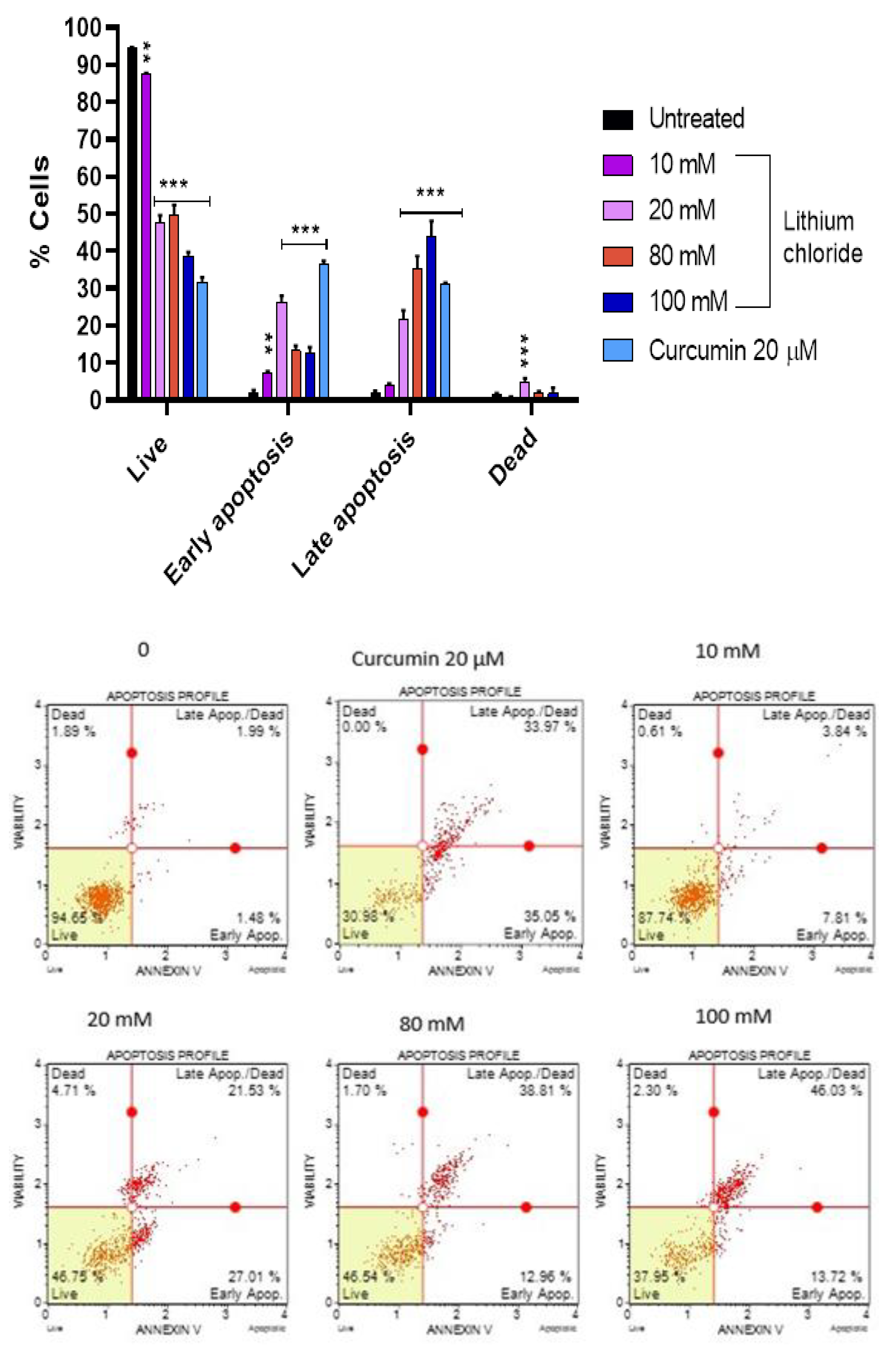

3.5. Mode of Cell Death Induced by LiCl in A549 Cells

Figure 5 shows that the majority of the A549 cells were live (94.490%), with minimal early apoptotic (2.067%), late apoptotic (2.073%), and dead cells (1.370%) in the untreated control. As the concentration of LiCl increased, the percentage of live cells decreased dramatically, reaching 38.733% at 100 mM. At 20 mM, there was a marked increase in early apoptotic cells (26.433%) and late apoptotic cells (21.677%). Whereas at the higher concentrations (80 mM and 100 mM), the majority were late apoptotic cells, peaking at 44.130% at 100 mM, while early apoptosis decreased slightly. Curcumin (20 µM) caused a significant increase in early apoptosis (36.527%) and a relatively high percentage of late apoptotic cells (31.027%), while dead cells remained low (0.727%). These results suggest that LiCl induces cell death predominantly through apoptosis, with higher concentrations shifting cells toward late apoptotic stages.

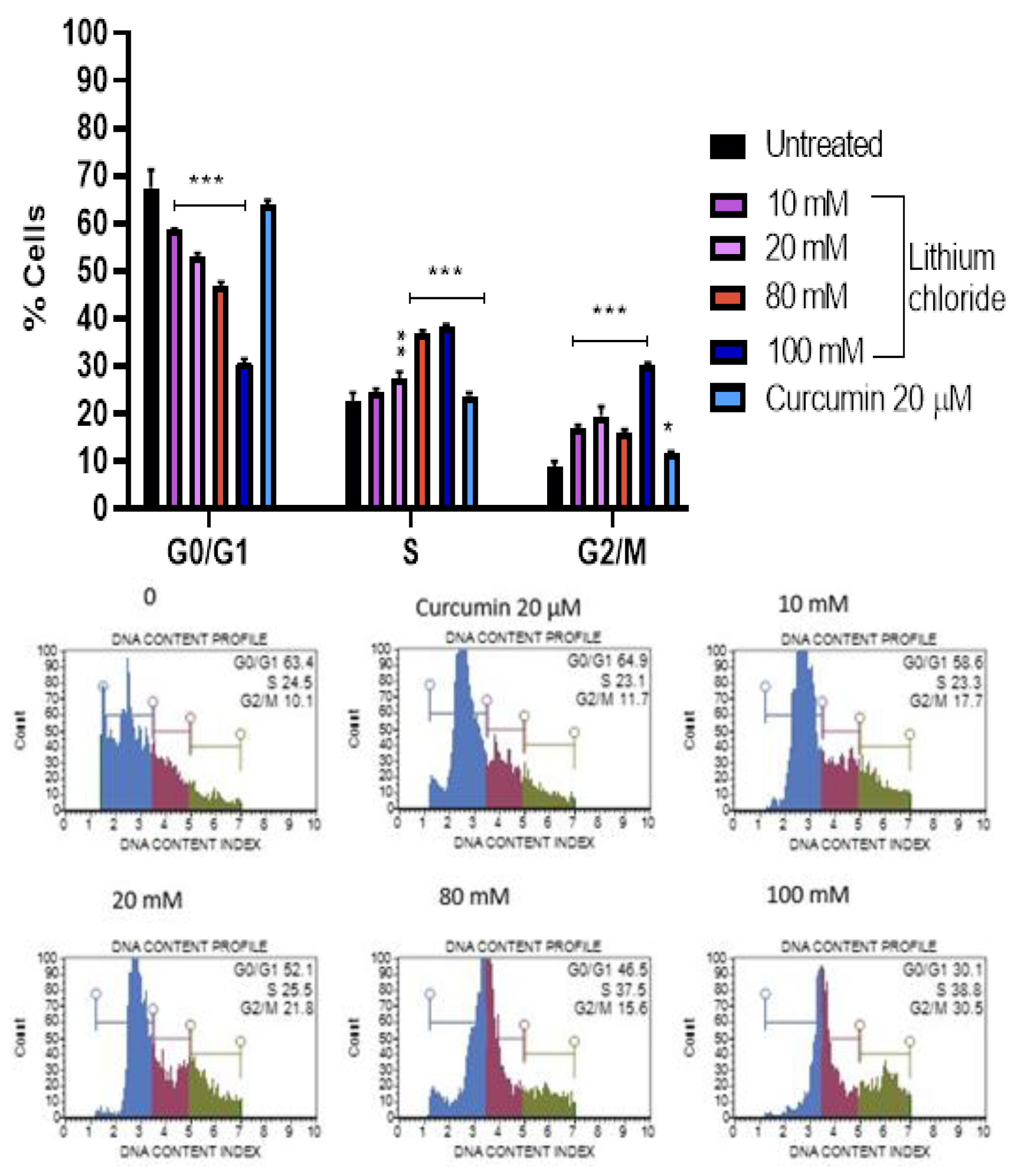

3.6. Cell Cycle Arrest Potential of Lithium Chloride

Figure 6 shows that lithium chloride induces a concentration-dependent shift in the cell cycle distribution of A549 cells. In the untreated control, the majority of cells were in the G0/G1 phase (67.467%), with fewer in the S (22.400%) and G2/M (8.900%) phases. As the concentration of LiCl increased, the percentage of cells in G0/G1 decreased significantly, reaching 30.767% at 100 mM. Simultaneously, cells accumulated in the S and G2/M phases, with the S phase peaking at 38.367% and G2/M at 30.167% at 100 mM. Curcumin (20 µM) had a milder effect on the cell cycle, maintaining a higher percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase (64.033%) compared to high concentrations of LiCl. These results suggest that LiCl disrupts the normal cell cycle progression of A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner, leading to cell cycle arrest in the S and G2/M phases. This disruption is indicative of a mechanism of cytotoxicity or growth inhibition caused by lithium chloride.

4. Discussion

Macrophages play crucial roles as a primary line of defense against infectious pathogens or foreign agents also by cleaning up apoptotic debris [

11,

13]. As such Raw 264.7 cells were used as a model of macrophages.

Figure 1 shows that concentrations of 20 mM and below are significantly less toxic to Raw 264.7 cells. Makola

et al., 2020 showed that 50-100 mM lithium chloride concentrations were cytotoxic to Raw 264.7 cells [

14]. Lithium treatment is known to inhibit the growth of most cancerous cells at concentrations more than 10 mM [

15]. Our results proved the cell viability of A549 significantly reduced to 69- and 51% for 80- and 100 mM respectively after 24 hours of treatment (

Figure 2). Lan

et al., 2013 showed that the proliferation of A549 cells was significantly inhibited by LiCl at concentrations of above 40 mM [

36]. Redox metabolism causes an abnormal accumulation of reactive oxygen species in cancer cells, hence their involvement in A549 cells molecular pathways was investigated. ROS can either help prevent cancer by killing abnormal cells or they can promote cancer by causing mutations [

10]. Treatment with LiCl without any stimuli induced ROS production of 19-, 26- and 28% for 20-, 80- and 100 mM respectively (

Figure 3). This suggests that LiCl-induced ROS contributes to cell death by forming nuclear DNA damage. Other studies showed that LiCl exerted prooxidant effects in colon cancer cells and Raw 264.7 cells [

11,

14].

Another free radical that affects cancer-related processes is nitric oxide was also investigated. Nitric oxide synthase produces relatively large amounts of NO in response to inflammatory or mitogenic stimuli and acts in a host-defensive role through its oxidative toxicity [

27]. The NO production assay (

Figure 4) showed as the concentration of lithium chloride increases, the percentage of live NO-negative cells significantly decreases, with a corresponding rise in NO-positive populations. At 10 mM, the percentage of dead NO-positive cells was relatively low, but at 20 mM and higher concentrations (80 mM and 100 mM), there is a substantial increase in dead NO-positive cells, particularly at 100 mM. These findings align with the known cytotoxic effects of excessive NO in inducing cell damage and apoptosis.

Figure 5 shows that high concentrations of lithium chloride induce late apoptosis in A549 cells. Late apoptotic cells that have lost membrane integrity), as such, they release inflammatory intracellular contents. However, at a concentration of 20 mM, there was a marked increase in early apoptotic cells. Figures 3 and -4 showed that lithium chloride promotes oxidative stress and NO production in A549 cells which then leads to cell death as observed. Other studies have shown that LiCl induces apoptosis with DNA fragmentation and in various types of cancer cells, including glioblastoma [

29], breast [

30] and leukemia [

31].

One of the ways to screen for potentially therapeutic drugs is to measure changes in cell cycle kinetics under varying conditions. Cell cycle describes a process that leads to replication and cell division, including G0/G1, G1/S (Synthesis) DNA damage checkpoint, and the G2/M (Mitosis) surveillance checkpoints [

32]. Based on the results

Figure 6), LiCl promotes cells to re-entry into the cell cycle and simultaneously inhibits DNA replication by blocking them in the S phase [

33]. The G2/M checkpoint prevents cells from entering mitosis if there’s DNA is damaged, allowing the repair or death of damaged cells. Other studies showed that lithium arrest cells in the S and G2/M phases in both leukaemia [

11] and glioblastoma [

34] cells but only the G2/M phase in oesophageal cells [

35].

5. Conclusion

Our results suggest that increased ROS generation and oxidative stress have a crucial role in lithium cytotoxic mechanism in A549 cells. While the concentration of 100 mM of lithium chloride showed best results in all assays, we advise for the use of 20 mM to avoid any toxicities as observed in the 264.7 macrophage cells at higher concentrations. Further studies are required to investigate cytokine production and gene expression of cell cycle and apoptosis-related genes.

Funding Information

This study was funded by the National Research Foundation (Postgraduate fund).

Ethical Statement

No animals were used in this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors of the present work declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank National Research Foundation for funding.

References

- Pikin, O.V., Ryabov, A.B., Glushko, V.A., Kolbanov, K.I., Amiraliev, A.M., Vursol, D.A., Bagrov, V.A., and Barmin, V.(2016) 'Surgery for non-small cell lung carcinoma after previous chemoradiotherapy alone', Khirurgiia, 11, pp. 28–31. [CrossRef]

- Zappa, C. and Mousa, S.A. (2016) 'Non-small cell lung cancer: current treatment and future advances', Translational Lung Cancer Research, 5(3), pp. 288–300. [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S., Morgensztern, D. and Boshoff, C. (2018) 'The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer', Nature, 553(7689), pp. 446–454. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Herbst, R.S. and Boshoff, C. (2021) 'Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer', Nature Medicine, 27(8), pp. 1345–1356. [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E., Kazerooni, E., Baum, S.L., Dransfield, M.T., Eapen, G.A., Ettinger, D.S., Hou, L., Jackman, D.M., Klippenstein, D., Kumar, R., Lackner, R.P, Leard, L.E, Leung, A.N., Makani, S.S., Massion, P.P., Meyers, B.F., Otterson, G.A., Peairs, K., Pipavath, S., Pratt-Pozo, C., Reddy, C., Reid, M.E., Rotter, A.J., Sachs, P.B., Schabath, M.B., Sequist, L.V., Tong, B.C., Travis, W.D., Yang, S.C., Gregory, K.M., and Hughes, M. (2015) 'Lung cancer screening, version 1.2015: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines', Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 13(1), pp. 23–34. [CrossRef]

- D'Souza, R., Rajji, T.K., Mulsant, B.H. and Pollock, B.G. (2011) 'Use of lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder in late-life', Current Psychiatry Reports, 13(6), pp. 488–492. [CrossRef]

- Kovacsics, C.E., Gottesman, T.D. and Gould, T.D. (2009) 'Lithium's antisuicidal efficacy: elucidation of neurobiological targets using endophenotype strategies', Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 49, pp. 175–198. [CrossRef]

- Post, R.M. (2016) 'Treatment of bipolar depression: evolving recommendations', Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 39(1), pp. 11–33. [CrossRef]

- Matsebatlela, T.M., Gallicchio, V. and Becker, R.P. (2012) 'Lithium modulates cancer cell growth, apoptosis, gene expression and cytokine production in HL-60 promyelocytic leukaemia cells and their drug-resistant sub-clones', Biological Trace Element Research, 149(3), pp. 323–330. [CrossRef]

- Novetsky, A.P., Thompson, D.M., Zighelboim, I., Thaker, P.H., Powell, M.A., Mutch, D.G., and Goodfellow, P.J. (2012). Lithium Chloride and Inhibition of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3&bgr; as a Potential Therapy for Serous Ovarian Cancer. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer, 23, 361–366. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Huang, K., Liu, X., Liu, J., Lu, X., Tao, K., Wang, G. and Wang, J . (2014) 'Lithium chloride suppresses colorectal cancer cell survival and proliferation through ROS/GSK-3β/NF-κB signalling pathway', Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2014, p. 241864. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Song, S. and Zhang, H. (2021) 'Cancer therapeutic strategies based on metal ions', Chemical Science, 12, pp. 12234–12247.

- Strunecká, J., Patočka, J. and Sárek, M. (2005) 'How does lithium mediate its therapeutic effects?', Journal of Applied Biomedicine, 3, pp. 25–35.

- Makola, R.T., Mbazima, V.G., Mokgotho, M.P., Gallicchio, V.S. and Matsebatlela, T.M. (2020) 'The effect of lithium on inflammation-associated genes in lipopolysaccharide-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages', International Journal of Inflammation, 2020, p. 8340195. [CrossRef]

- Liou, G.Y. and Storz, P. (2010) 'Reactive oxygen species in cancer', Free Radical Research, 44, pp. 479–496. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H. and Takada, K. (2021) 'Reactive oxygen species in cancer: Current findings and future directions', Cancer Science, 112, pp. 3945–3952. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Qi, H., Liu, Y., Duan, C., Liu, X., Xia, T., Chen, D., Piao, H.L. and Liu, H.X. (2021) 'The double-edged roles of ROS in cancer prevention and therapy', Theranostics, 11, pp. 4839–4857. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W., Liu, L.Z., Loizidou, M., Ahmed, M. and Charles, I.G. (2002) 'The role of nitric oxide in cancer', Cell Research, 12, pp. 311–320. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H., Wang, L., Mollica, M., Re, A.T., Wu, S. and Zuo, L. (2014) 'Nitric oxide in cancer metastasis', Cancer Letters, 353, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. (2007) 'Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death', Toxicologic Pathology, 35, pp. 495–516. [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, C.M. and Singh, A.T.K. (2018) 'Apoptosis: A target for anticancer therapy', International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19, p. 448. [CrossRef]

- Jan, R. and Chaudhry, G.E. (2019) 'Understanding apoptosis and apoptotic pathways targeted cancer therapeutics', Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 9, pp. 205–218. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, B.A. and El-Deiry, W.S. (2020) 'Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy', Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 17, pp. 395–417. [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.P. and Cook, J.G. (2017) 'Cell cycle proliferation decisions: the impact of single-cell analyses', FEBS Journal, 284, pp. 362–375. [CrossRef]

- Lendeckel, U., Venz, S. and Wolke, C. (2022) 'Macrophages: shapes and functions', ChemTexts, 8(2), p. 12. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y., Liu, X., Zhang, R., Wang, K., Wang, Y. and Hua, Z.C. (2013) 'Lithium enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human lung carcinoma A549 cells', Biometals, 26, pp. 241–254. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H. and Takada, K. (2021) 'Reactive oxygen species in cancer: current findings and future directions', Cancer Science, 112(10), pp. 3945–3952. [CrossRef]

- Xing, F., Hu, Q., Qin, Y., Xu, J., Zhang, B., Yu, X. and Wang, W. (2022) 'The relationship of redox with hallmarks of cancer: the importance of homeostasis and context', Frontiers in Oncology, 12, p. 862743. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhang, Q., Wang, B., Li, P. and Liu, P. (2017) 'LiCl treatment induces programmed cell death of Schwannoma cells through AKT- and MTOR-mediated necroptosis', Neurochemical Research, 42, pp. 2363–2371. [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, C. (2001) 'Nitric oxide and the immune response', Nature Immunology, 2, pp. 907–915. [CrossRef]

- Sabancı, P.A., Ergüven, M., Yazıhan, N., Aktaş, E., Aras, Y., Civelek, E., Aydoseli, A., Imer, M., Gürtekin, M., and Bilir, A. (2014) 'Sorafenib and lithium chloride combination treatment shows promising synergistic effects in human glioblastoma multiforme cells in vitro but midkine is not implicated', Neurological Research, 36, pp. 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Razmi, M., Rabbani-Chadegani, A., Hashemi-Niasari, F. and Ghadam, P. (2018) 'Lithium chloride attenuates mitomycin C-induced necrotic cell death in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells via HMGB1 and Bax signaling', Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, 48, pp. 87–96. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Song, H., Zhong, L., Yang, R., Yang, X.Q., Jiang, K.I. and Liu, B.Z. (2015) 'Lithium chloride promotes apoptosis in human leukemia NB4 cells by inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta', International Journal of Medical Sciences, 12, pp. 805–810. [CrossRef]

- Barnum, K.J. and O’Connell, M.J. (2014) 'Cell cycle regulation by checkpoints', Methods in Molecular Biology, 1170, pp. 29–40. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., Zhu, B., Zhan, M. and Hua, Z.C. (2023) 'Lithium in cancer therapy: Friend or foe?', Cancers, 15, p. 1095. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.S., Wang, C.L., Wen, J.F., Wang, Y.J., Hu, Y.B. and Ren, H.Z. (2008) 'Lithium inhibits proliferation of human esophageal cancer cell line Eca-109 by inducing a G2/M cell cycle arrest', World Journal of Gastroenterology, 14, pp. 3982–3989. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y., Liu, X., Zhang, R., Wang, K., Wang, Y. and Hua, Z.C. (2013) 'Lithium enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human lung carcinoma A549 cells', Biometals, 26, pp. 241–254. [CrossRef]

- Han, S., Meng, L., Jiang, Y., Cheng, W., Tie, X., Xia, J. and Wu, A. (2017) 'Lithium enhances the antitumor effect of temozolomide against TP53 wild-type glioblastoma cells via NFAT1/FasL signalling', British Journal of Cancer, 116, pp. 1302–1311. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Cell viability (%) after treatment with varying concentrations of LiCl (0, 5 mM, 10 mM, 20 mM, 40 mM, 80 mM, 100 mM) and curcumin (20 µM) Raw 264.7 macrophage cells over 24 and 48 hours. Cell viability was assessed using MTT assay and the results show that increasing LiCl concentrations decrease cell viability of Raw 264.7 cells. At 24 hours, cell viability significantly dropped at 40 mM and higher concentrations, with the most pronounced reduction at 100 mM. At 48 hours, the dose-dependent reduction in cell viability became even more apparent, with significant decreases observed at 20 mM and higher concentrations. Statistical significance is indicated: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control group. Error bars represent mean + standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Cell viability (%) after treatment with varying concentrations of LiCl (0, 5 mM, 10 mM, 20 mM, 40 mM, 80 mM, 100 mM) and curcumin (20 µM) Raw 264.7 macrophage cells over 24 and 48 hours. Cell viability was assessed using MTT assay and the results show that increasing LiCl concentrations decrease cell viability of Raw 264.7 cells. At 24 hours, cell viability significantly dropped at 40 mM and higher concentrations, with the most pronounced reduction at 100 mM. At 48 hours, the dose-dependent reduction in cell viability became even more apparent, with significant decreases observed at 20 mM and higher concentrations. Statistical significance is indicated: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control group. Error bars represent mean + standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Effect of varying concentrations of lithium chloride (0, 5 mM, 10 mM, 20 mM, 40 mM, 80 mM, 100 mM) and curcumin (20 µM) on cell viability (%) after 24 and 48 hours of treatment. Cell viability was measured using MTT assay and data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from 3 repeats. Treatment with increasing concentrations of LiCl demonstrated a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability. At 24 hours, significant reductions in viability were observed at concentrations ≥40 mM, with the lowest viability recorded at 100 mM. After 48 hours, the cytotoxic effect of LiCl was more noticeable, with significant decreases beginning at 20 mM. Curcumin (20 µM) exhibited a protective effect (used as positive control). Statistical significance is indicated: ***p < 0.001. Error bars represent mean + standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Effect of varying concentrations of lithium chloride (0, 5 mM, 10 mM, 20 mM, 40 mM, 80 mM, 100 mM) and curcumin (20 µM) on cell viability (%) after 24 and 48 hours of treatment. Cell viability was measured using MTT assay and data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from 3 repeats. Treatment with increasing concentrations of LiCl demonstrated a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability. At 24 hours, significant reductions in viability were observed at concentrations ≥40 mM, with the lowest viability recorded at 100 mM. After 48 hours, the cytotoxic effect of LiCl was more noticeable, with significant decreases beginning at 20 mM. Curcumin (20 µM) exhibited a protective effect (used as positive control). Statistical significance is indicated: ***p < 0.001. Error bars represent mean + standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Percentage of ROS-negative and ROS-positive A549 cells following treatment with lithium chloride at various concentrations (0, 10 mM, 20 mM, 80 mM, 100 mM) and LPS (10 µg/mL). These results suggest that LiCl induces oxidative stress in a dose-dependent manner. ROS levels were measured using Oxidative stress flow cytometry Muse® assay, and data are expressed as mean ± standard error of 3 repeats. Statistical significance is indicated as ***p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control.

Figure 3.

Percentage of ROS-negative and ROS-positive A549 cells following treatment with lithium chloride at various concentrations (0, 10 mM, 20 mM, 80 mM, 100 mM) and LPS (10 µg/mL). These results suggest that LiCl induces oxidative stress in a dose-dependent manner. ROS levels were measured using Oxidative stress flow cytometry Muse® assay, and data are expressed as mean ± standard error of 3 repeats. Statistical significance is indicated as ***p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control.

Figure 4.

Effects of lithium chloride on nitric oxide production and cell viability of A549 cells. The bar graph represents the percentage of live NO-negative cells, live NO-positive cells, dead NO-positive cells, and total NO-positive cells after treatment with various concentrations of LiCl. The graph demonstrates that lithium chloride induces nitric oxide (NO) production and affects cell viability of A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Data were determined using DAF2-DA/PI staining for NO detection and flow cytometry. Data is presented as mean ± standard error of 3 repeats. Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control.

Figure 4.

Effects of lithium chloride on nitric oxide production and cell viability of A549 cells. The bar graph represents the percentage of live NO-negative cells, live NO-positive cells, dead NO-positive cells, and total NO-positive cells after treatment with various concentrations of LiCl. The graph demonstrates that lithium chloride induces nitric oxide (NO) production and affects cell viability of A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Data were determined using DAF2-DA/PI staining for NO detection and flow cytometry. Data is presented as mean ± standard error of 3 repeats. Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control.

Figure 5.

Distribution of live, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and dead cells following treatment with Lithium chloride. A549 cells were treated with various concentrations of LiCl (10 mM, 20 mM, 80 mM, 100 mM) and curcumin (20 µM) was used as a positive control. The data shows that LiCl induces dose-dependent effects on cell viability and apoptosis The results were obtained using the Muse® Annexin V and Dead Cell Kit and data are expressed as mean ± standard error of 3 repeats. Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control.

Figure 5.

Distribution of live, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and dead cells following treatment with Lithium chloride. A549 cells were treated with various concentrations of LiCl (10 mM, 20 mM, 80 mM, 100 mM) and curcumin (20 µM) was used as a positive control. The data shows that LiCl induces dose-dependent effects on cell viability and apoptosis The results were obtained using the Muse® Annexin V and Dead Cell Kit and data are expressed as mean ± standard error of 3 repeats. Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control.

Figure 6.

Effects of lithium chloride on cell cycle distribution (% of cells in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases) of A549 cells. Cells were treated with LiCl at concentrations of 0, 10 mM, 20 mM, 80 mM, and 100 mM, or curcumin, and analysed using the Muse® Cell Analyzer. As the concentration of LiCl increased, the percentage of A549 cells in G0/G1 decreased significantly, while simultaneously, accumulating in the S and G2/M phases. Statistical significance is indicated: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control group. Error bars represent mean ± standard error of 3 repeats.

Figure 6.

Effects of lithium chloride on cell cycle distribution (% of cells in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases) of A549 cells. Cells were treated with LiCl at concentrations of 0, 10 mM, 20 mM, 80 mM, and 100 mM, or curcumin, and analysed using the Muse® Cell Analyzer. As the concentration of LiCl increased, the percentage of A549 cells in G0/G1 decreased significantly, while simultaneously, accumulating in the S and G2/M phases. Statistical significance is indicated: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control group. Error bars represent mean ± standard error of 3 repeats.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).