Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

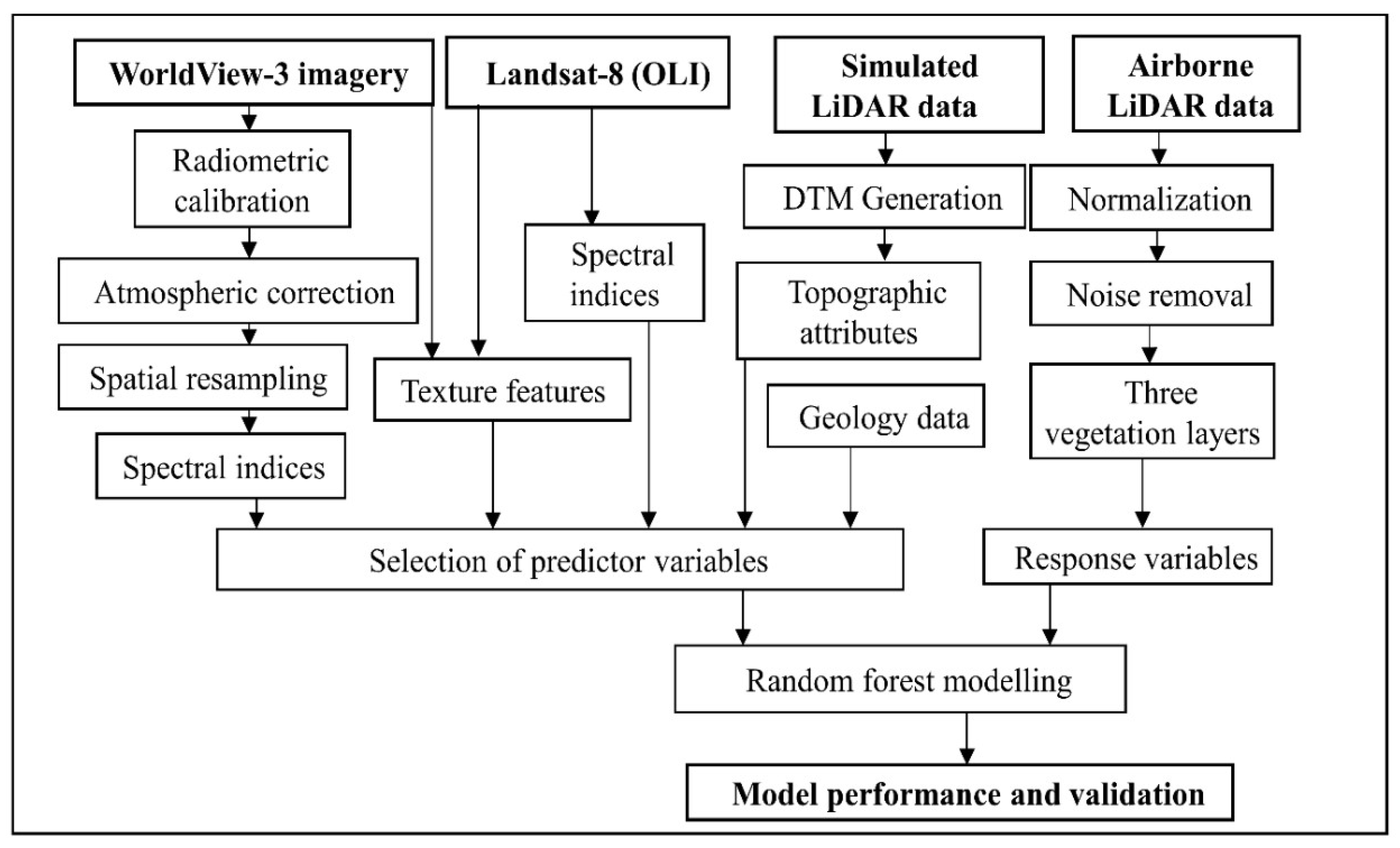

2. Materials and Methods

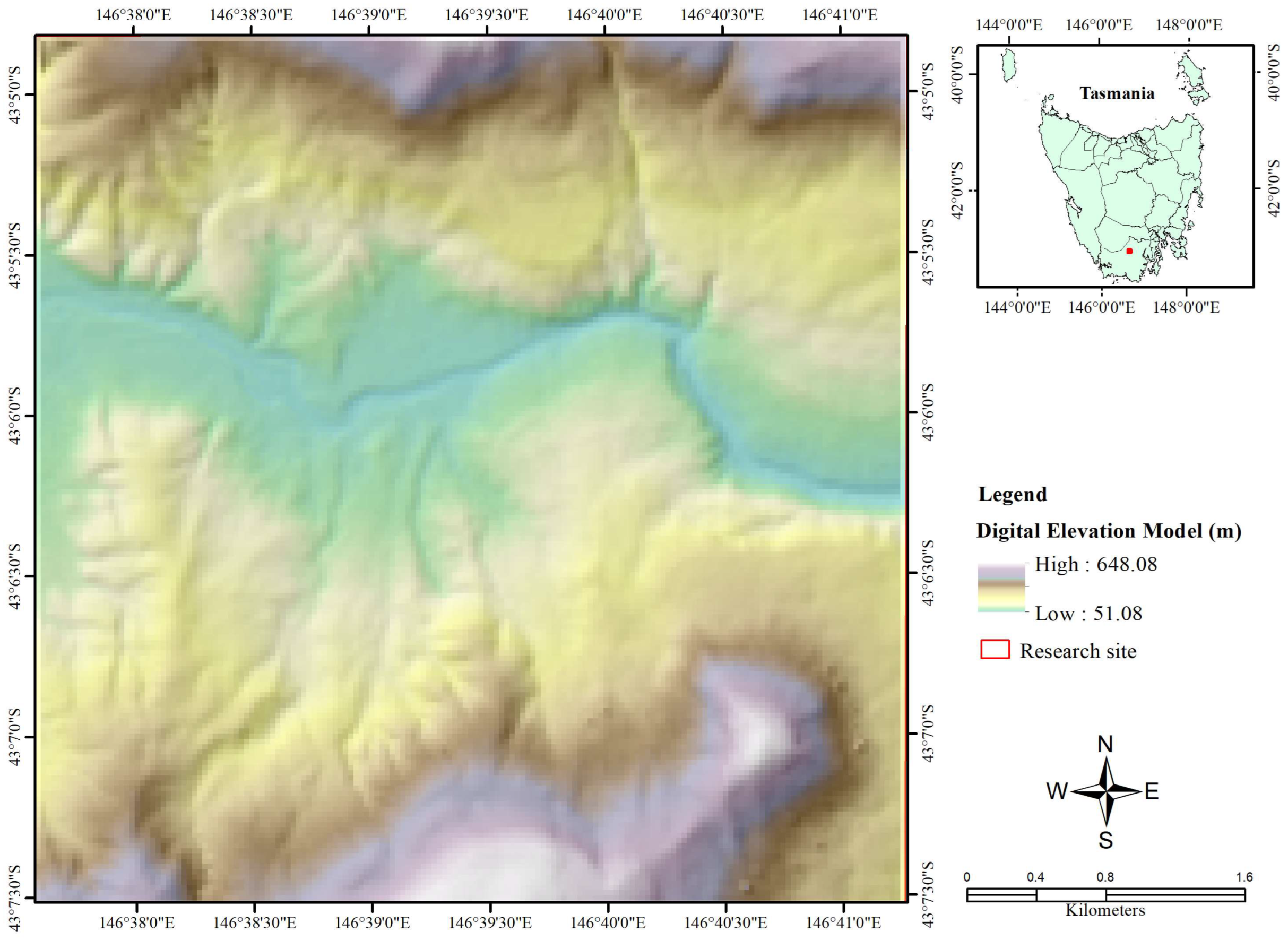

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Remote Sensing Data

2.3. Data Pre-Processing

2.4. Response and Predictor Variables

- Spectral bands (B);

- Topographic attributes and geology (A+G);

- Spectral indices (I);

- Spectral bands, topographic attributes, and geology (B+A+G);

- Spectral bands and spectral indices (B+I);

- Topographic attributes, geology, and spectral indices (A+G+I);

- Spectral bands, topographic attributes, geology, and spectral indices (B+A+G+I);

- Texture features (T);

- Spectral bands and texture features (B+T);

- Topographic attributes, geology, and texture features (A+G+T);

- Spectral indices and texture features (I+T);

- Topographic attributes, geology, spectral indices, and texture features (A+G+I+T);

- Spectral bands, topographic attributes, geology, spectral indices, and texture features (B+A+G+I+T).

2.5. Random Forest Modelling

3. Results

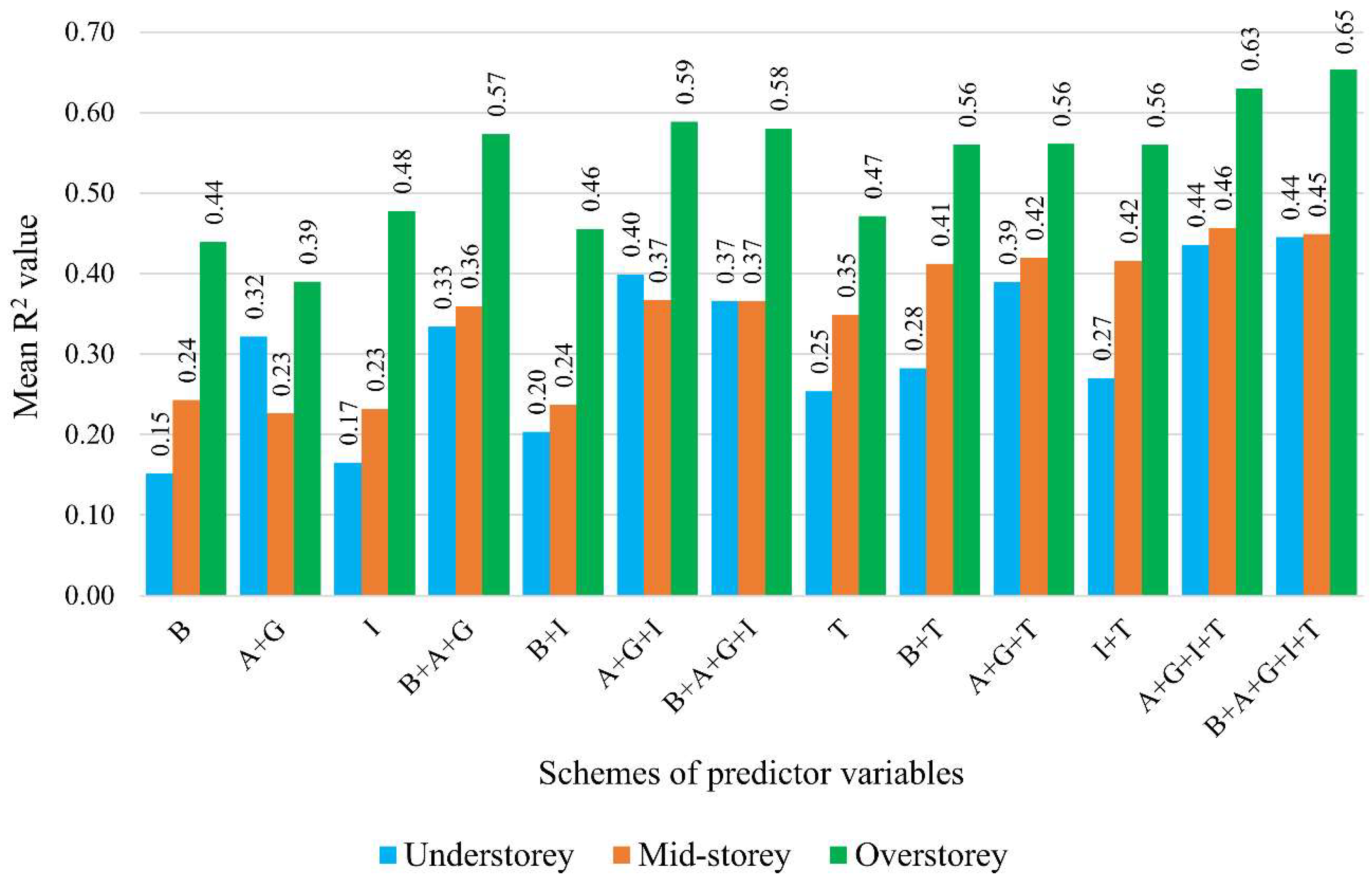

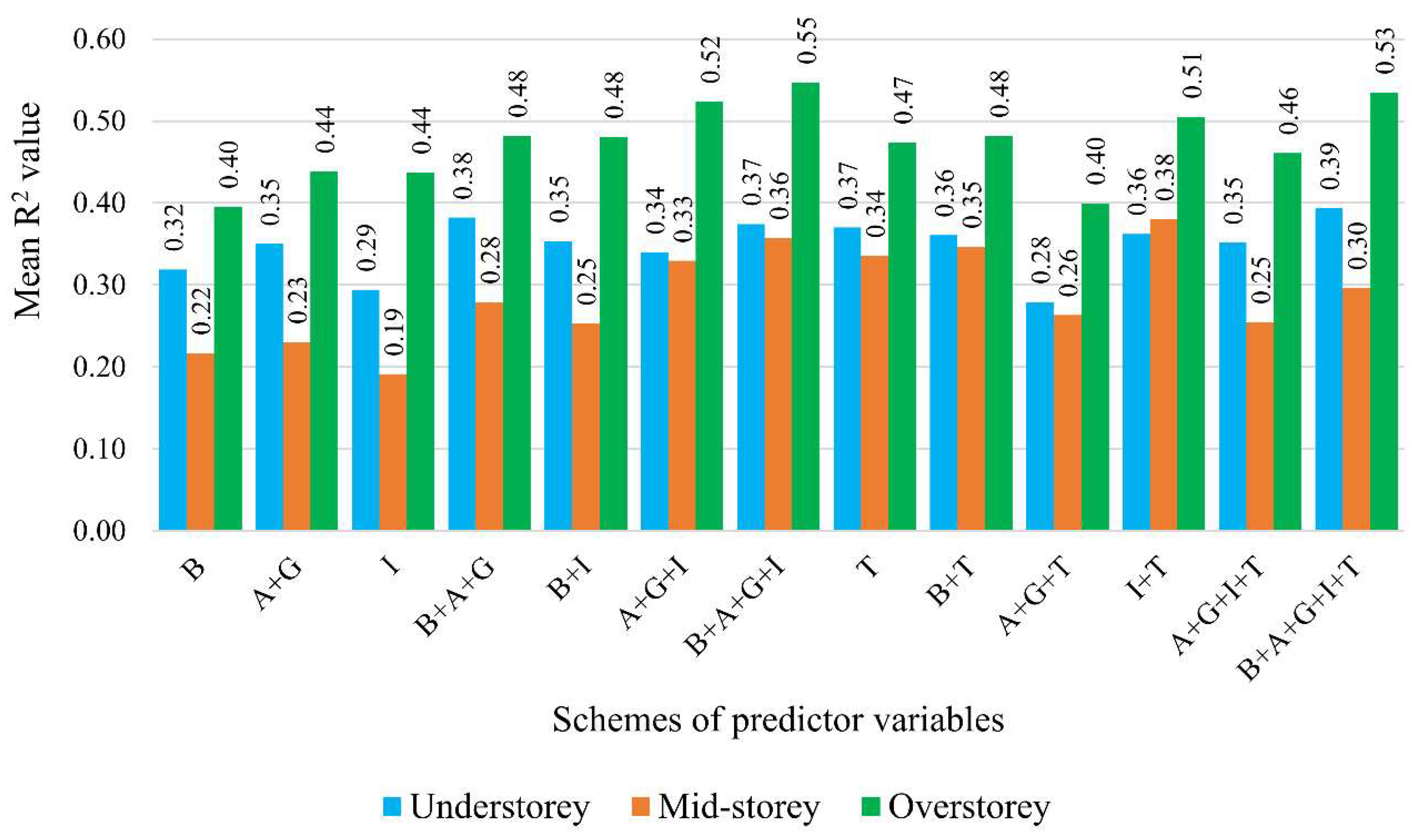

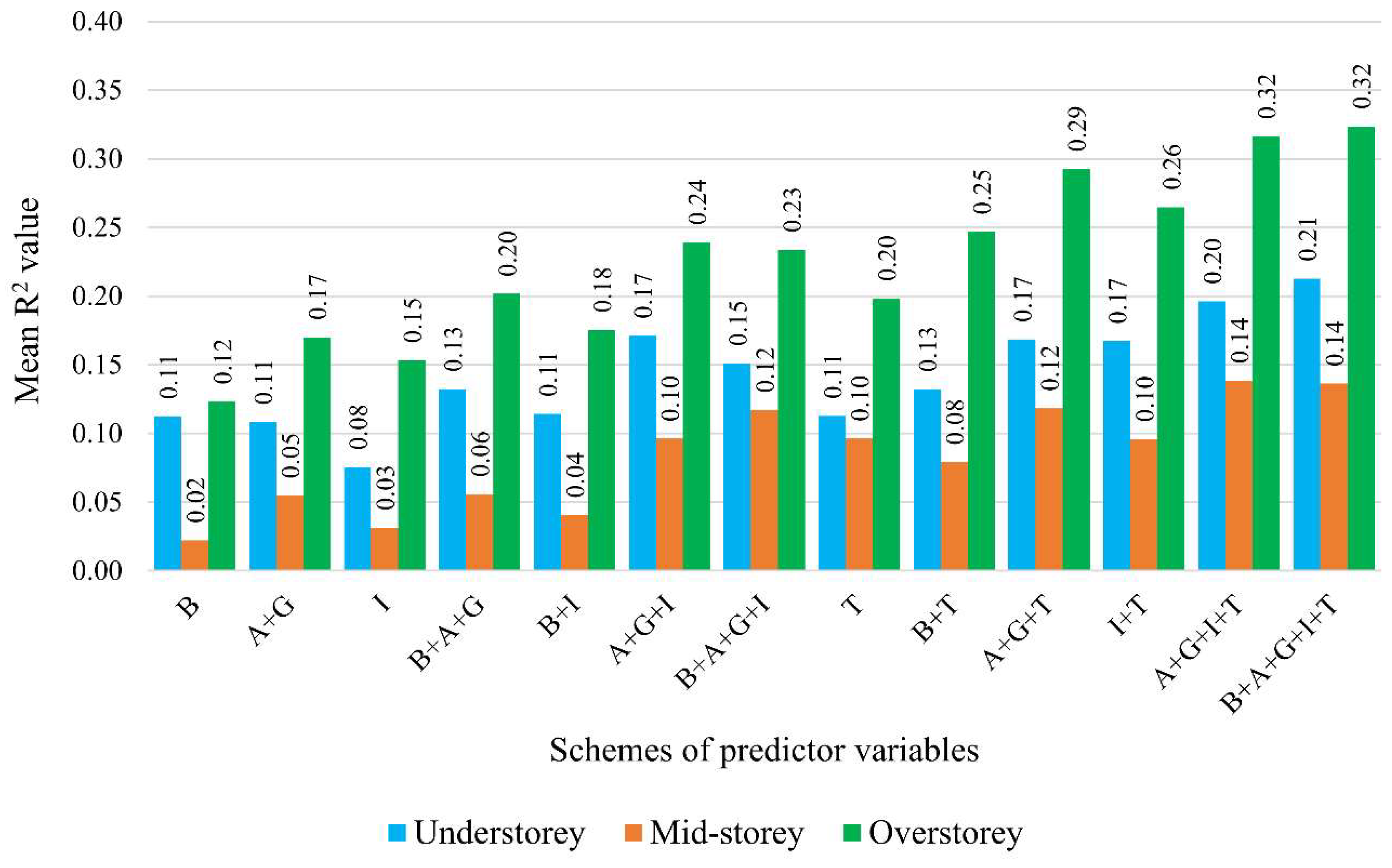

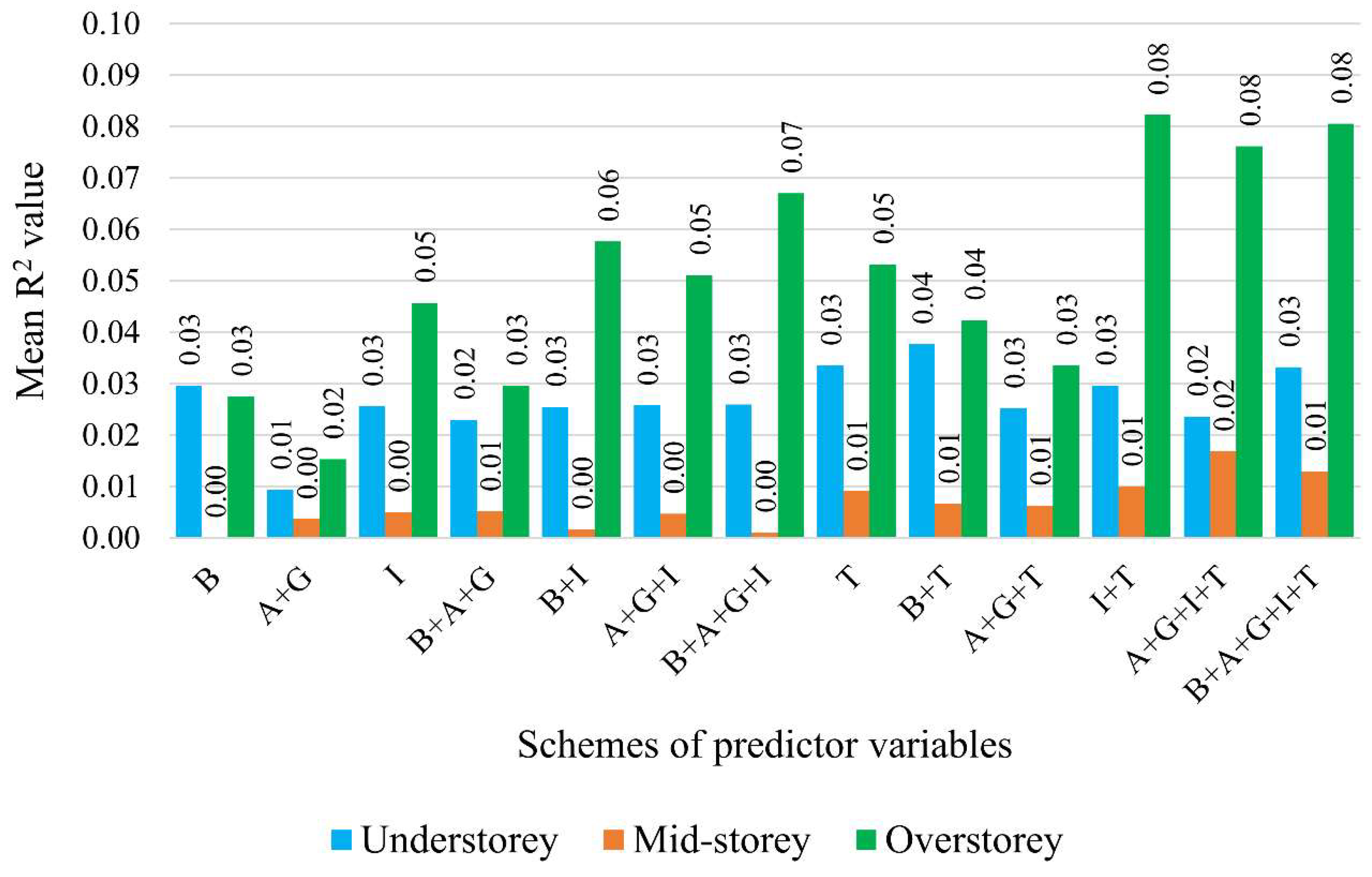

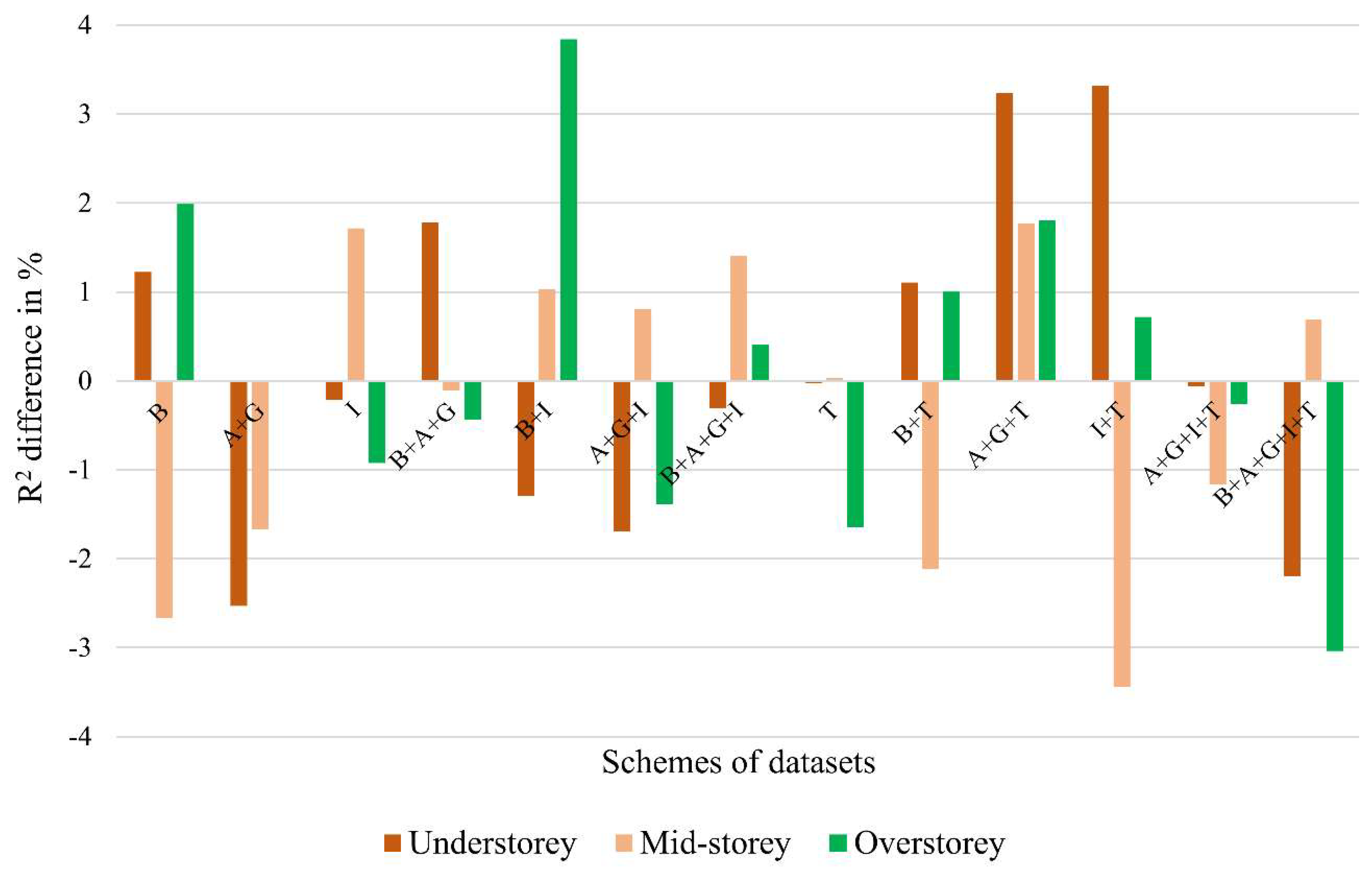

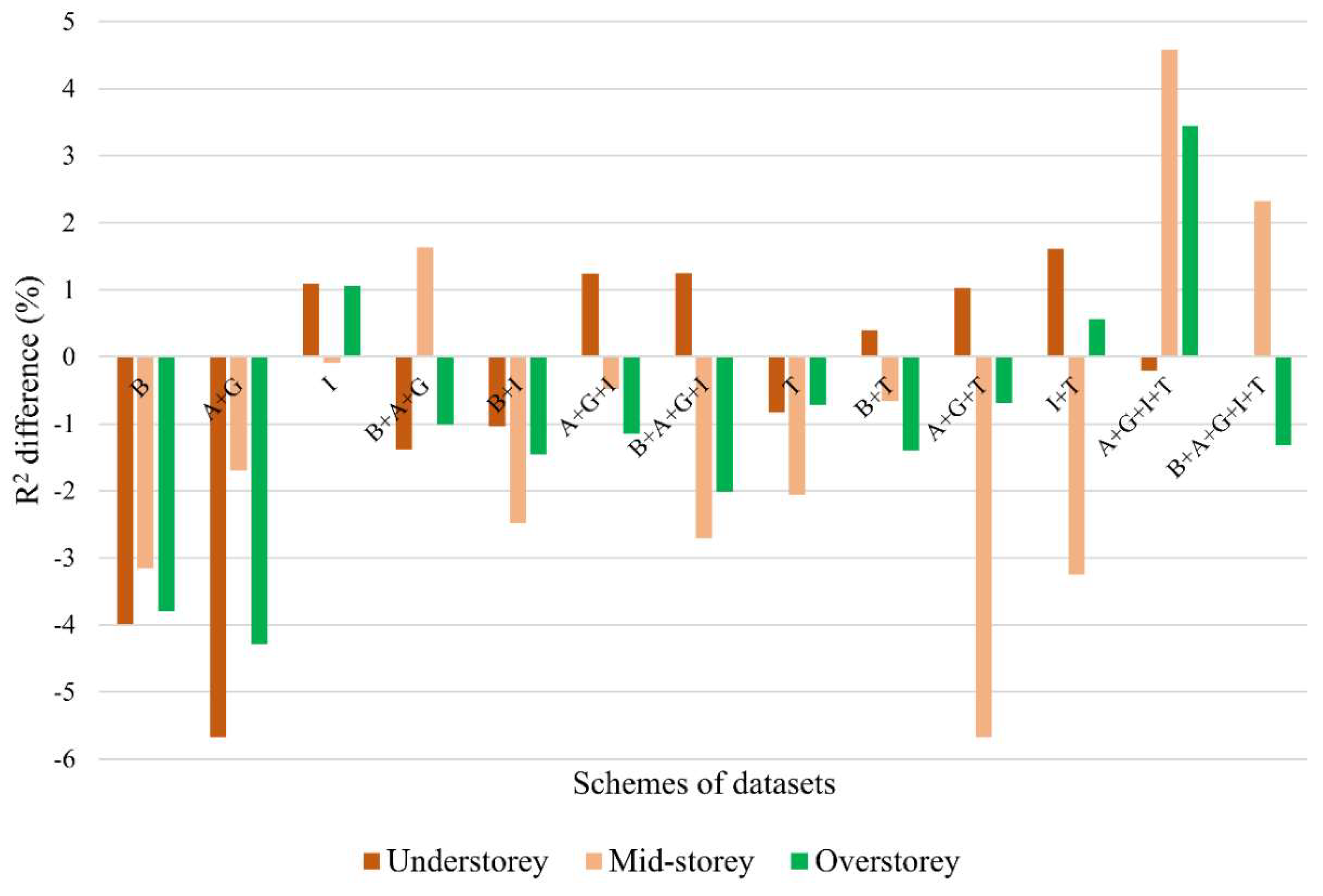

3.1. Model Accuracy Assessment

3.2. Model Validation

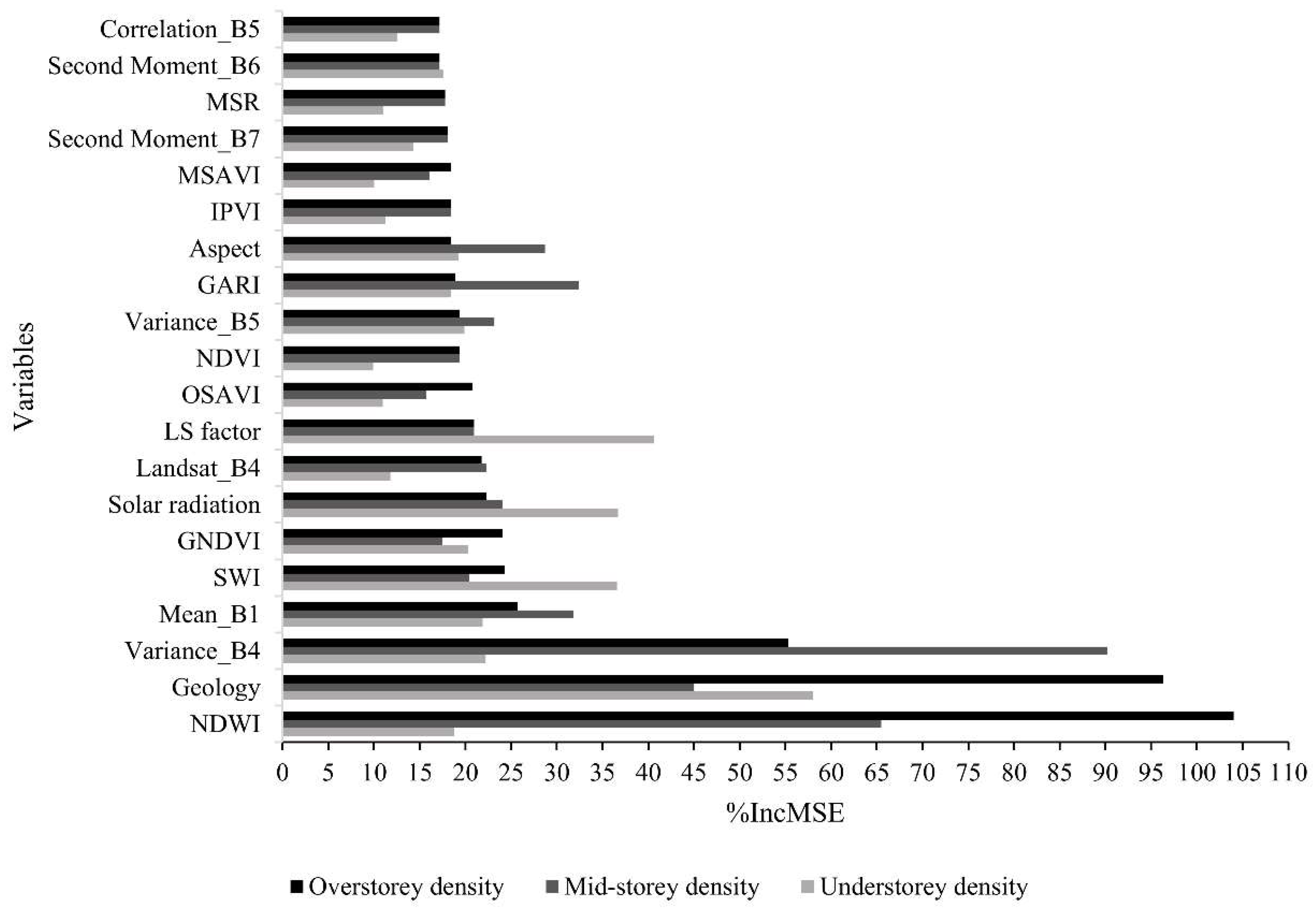

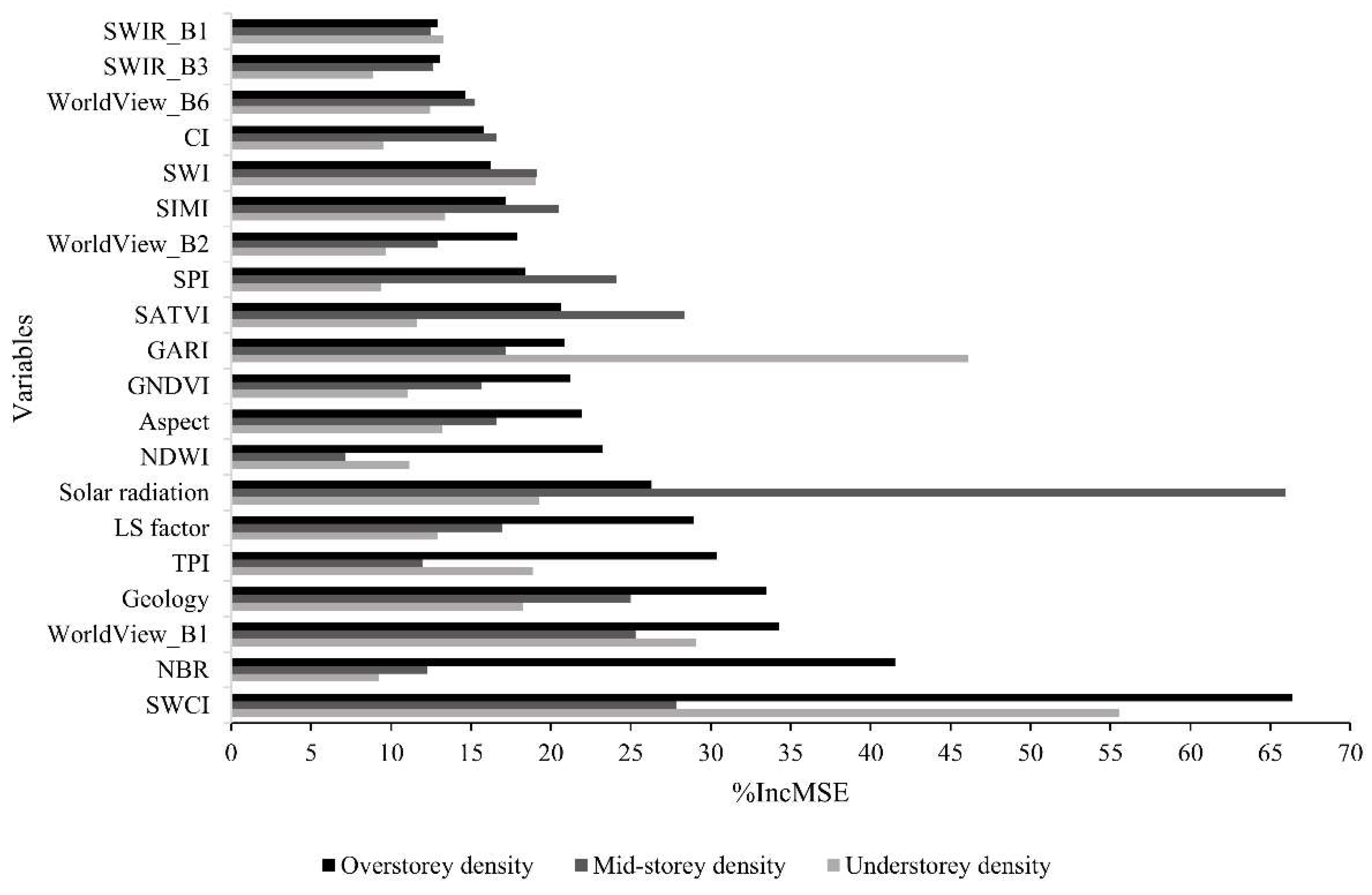

3.3. Importance of Predictor Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| VFS | Vertical forest structure |

| DTM | Digital terrain model |

| VNIR | Visible near-infrared |

| SWIR | Shortwave infrared |

| OLI | Operational Land Imager |

| RF | Random forest |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

Appendix A

| Texture Feature | Description | Equations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | The grey level of the two pixels of the same image varies | [20] | |

| Correlation | Captures how the pairs of pixels are correlated to other pixel pairs | [20] | |

| Dissimilarity | Two samples vary with the number of grey levels | [99] | |

| Entropy | Captures the amount of variation in the co-occurrence of the grey level distribution | [100] | |

| Homogeneity | measures how close the distribution of elements in the GLCM | [99] | |

| Mean | Mean value of intensities over the image | [100] | |

| Angular second moment | a measure of homogeneity of an image/measures the local uniformity of the grey levels | [100] | |

| Variance | a measure of "roughness" | [20] |

| Spectral Indices | Acronyms | Equations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Atmospherically Resistant Index | GARI | [101] | |

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | GNDVI | [102] | |

| Infrared Percentage Vegetation Index | IPVI | [103] | |

| Modified Non-Linear Index | MNLI | [104] | |

| Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | MSAVI | [105] | |

| Modified Simple Ratio | MSR | [106] | |

| Non-Linear Index | NLI | [107] | |

| Normalised Difference Vegetation Index | NDVI | [108] | |

| Renormalised Difference Vegetation Index | RDVI | [109] | |

| Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | OSAVI | [110] | |

| Soil-Adjusted Total Vegetation Index | SATVI | [111,112,113] | |

| Normalized Burn Ratio (not for Landsat (OLI) data | NBR | [114,115] | |

| Normalised Difference Water Index | NDWI | [115,116] | |

| Surface Water Capacity Index | SWCI | [117] | |

| Shortwave Infrared Soil Moisture Index | SIMI | [117] |

References

- Zhou, X.; Li, C. Mapping the vertical forest structure in a large subtropical region using airborne LiDAR data. Ecological Indicators 2023, 154, 110731. [CrossRef]

- Blondeel, H.; Landuyt, D.; Vangansbeke, P.; De Frenne, P.; Verheyen, K.; Perring, M.P. The need for an understory decision support system for temperate deciduous forest management. Forest Ecology and Management 2021, 480, 118634. [CrossRef]

- Dubayah, R.; Blair, J.B.; Goetz, S.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Hansen, M.; Healey, S.; Hofton, M.; Hurtt, G.; Kellner, J.; Luthcke, S.; et al. The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation: High-resolution laser ranging of the Earth’s forests and topography. Science of Remote Sensing 2020, 1. [CrossRef]

- Jarron, L.R.; Coops, N.C.; MacKenzie, W.H.; Tompalski, P.; Dykstra, P. Detection of sub-canopy forest structure using airborne LiDAR. Remote Sensing of Environment 2020, 244. [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhao, A.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, H. Comparison of Modeling Algorithms for Forest Canopy Structures Based on UAV-LiDAR: A Case Study in Tropical China. Forests 2020, 11, 1324. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Gosselin, F.; Rao, X.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Jian, S.; Ren, H. Overstory and niche attributes drive understory biomass production in three types of subtropical plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 2021, 482, 118894. [CrossRef]

- Rutten, G.; Ensslin, A.; Hemp, A.; Fischer, M. Vertical and horizontal vegetation structure across natural and modified habitat types at Mount Kilimanjaro. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0138822. [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.P.; Watt, M.S.; Bhandari, S.; Watt, P. Characterising forest structure using combinations of airborne laser scanning data, RapidEye satellite imagery and environmental variables. Forestry 2016, 89, 159-169. [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, P.; Jones, S.D.; Suarez, L.; Haywood, A.; Mellor, A.; Woodgate, W.; Soto-Berelov, M.; Skidmore, A.K.; McMahon, S. Using discrete-return airborne laser scanning to quantify number of canopy strata across diverse forest types. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2016, 7, 700-712. [CrossRef]

- Furlaud, J.M.; Prior, L.D.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Fire risk and severity decline with stand development in Tasmanian giant Eucalyptus forest. Forest Ecology and Management 2021, 502, 119724. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, S.; Jung, H.-S. Mapping Forest Vertical Structure in Gong-ju, Korea Using Sentinel-2 Satellite Images and Artificial Neural Networks. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 1666. [CrossRef]

- Taneja, R.; Wallace, L.; Hillman, S.; Reinke, K.; Hilton, J.; Jones, S.; Hally, B. Up-Scaling Fuel Hazard Metrics Derived from Terrestrial Laser Scanning Using a Machine Learning Model. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1273.

- Silva, I.; Rocha, R.; López-Baucells, A.; Farneda, F.Z.; Meyer, C.F.J. Effects of Forest Fragmentation on the Vertical Stratification of Neotropical Bats. Diversity 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, P.; Jones, S.; Suarez, L.; Mellor, A.; Woodgate, W.; Soto-Berelov, M.; Haywood, A.; Skidmore, A. Mapping forest canopy height across large areas by upscaling ALS estimates with freely available satellite data. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 12563.

- Terryn, L.; Calders, K.; Bartholomeus, H.; Bartolo, R.E.; Brede, B.; D'Hont, B.; Disney, M.; Herold, M.; Lau, A.; Shenkin, A.; et al. Quantifying tropical forest structure through terrestrial and UAV laser scanning fusion in Australian rainforests. Remote Sensing of Environment 2022, 271. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, C. Mapping the vertical forest structure in a large subtropical region using airborne LiDAR data. Ecological Indicators 2023, 154. [CrossRef]

- Culbert, P.; Radeloff, V.; Flather, C.; Kellndorfer, J.; Rittenhouse, C.; Pidgeon, A. The influence of vertical and horizontal habitat structure on nationwide patterns of avian biodiversity. The Auk 2013, 130, 656-665. [CrossRef]

- Masek, J.G.; Hayes, D.J.; Joseph Hughes, M.; Healey, S.P.; Turner, D.P. The role of remote sensing in process-scaling studies of managed forest ecosystems. Forest Ecology and Management 2015, 355, 109-123. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.; Karnieli, A. Predicting forest structural parameters using the image texture derived from WorldView-2 multispectral imagery in a dryland forest, Israel. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2011, 13, 701-710. [CrossRef]

- Kayitakire, F.; Hamel, C.; Defourny, P. Retrieving forest structure variables based on image texture analysis and IKONOS-2 imagery. Remote Sensing of Environment 2006, 102, 390-401. [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D.K.; White, J.C.; Wulder, M.A.; Coops, N.C.; Hermosilla, T.; Yuan, X. Updating stand-level forest inventories using airborne laser scanning and Landsat time series data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2018, 66, 174-183. [CrossRef]

- Zald, H.S.J.; Wulder, M.A.; White, J.C.; Hilker, T.; Hermosilla, T.; Hobart, G.W.; Coops, N.C. Integrating Landsat pixel composites and change metrics with LiDAR plots to predictively map forest structure and aboveground biomass in Saskatchewan, Canada. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 176, 188-201. [CrossRef]

- Zald, H.S.J.; Ohmann, J.L.; Roberts, H.M.; Gregory, M.J.; Henderson, E.B.; McGaughey, R.J.; Braaten, J. Influence of LiDAR, Landsat imagery, disturbance history, plot location accuracy, and plot size on accuracy of imputation maps of forest composition and structure. Remote Sensing of Environment 2014, 143, 26-38. [CrossRef]

- Gebreslasie, M.T.; Ahmed, F.B.; van Aardt, J.A.N. Predicting forest structural attributes using ancillary data and ASTER satellite data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2010, 12, S23-S26. [CrossRef]

- Venier, L.A.; Swystun, T.; Mazerolle, M.J.; Kreutzweiser, D.P.; Wainio-Keizer, K.L.; McIlwrick, K.A.; Woods, M.E.; Wang, X. Modelling vegetation understory cover using LiDAR metrics. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0220096. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.; Phinn, S.; Johansen, K. Characterizing the spatial structure of mangrove features for optimizing image-based mangrove mapping. Remote Sensing 2014, 6, 984.

- Kunin, W.E.; Harte, J.; He, F.; Hui, C.; Jobe, R.T.; Ostling, A.; Polce, C.; Šizling, A.; Smith, A.B.; Smith, K.; et al. Upscaling biodiversity: estimating the species–area relationship from small samples. Ecological Monographs 2018, 88, 170-187, doi:doi:10.1002/ecm.1284.

- Zhang, N. Scale issues in ecology: Upscaling. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2007, 27, 4252-4266.

- Yang, X.; Qiu, S.; Zhu, Z.; Rittenhouse, C.; Riordan, D.; Cullerton, M. Mapping understory plant communities in deciduous forests from Sentinel-2 time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2023, 293. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Qi, S.; Liao, K.; Zhang, S.; Hu, B.; Tian, Y. Mapping the Forest Height by Fusion of ICESat-2 and Multi-Source Remote Sensing Imagery and Topographic Information: A Case Study in Jiangxi Province, China. Forests 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Wu, Q.; Li, G.; Li, D. Remote Sensing Technology for Observing Tree Mortality and Its Influences on Carbon–Water Dynamics. Forests 2025, 16, 194.

- Kim, J.; Popescu, S.C.; Lopez, R.R.; Wu, X.B.; Silvy, N.J. Vegetation mapping of No Name Key, Florida using lidar and multispectral remote sensing. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2020, 41, 9469-9506. [CrossRef]

- Bigdeli, B.; Amini Amirkolaee, H.; Pahlavani, P. DTM extraction under forest canopy using LiDAR data and a modified invasive weed optimization algorithm. Remote Sensing of Environment 2018, 216, 289-300. [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D.K.; Coops, N.C.; Wulder, M.A. Characterizing residual structure and forest recovery following high-severity fire in the western boreal of Canada using Landsat time-series and airborne lidar data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2015, 163, 48-60. [CrossRef]

- Hagar, J.C.; Yost, A.; Haggerty, P.K. Incorporating LiDAR metrics into a structure-based habitat model for a canopy-dwelling species. Remote Sensing of Environment 2020, 236. [CrossRef]

- Lesak, A.A.; Radeloff, V.C.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Pidgeon, A.M.; Gobakken, T.; Contrucci, K. Modeling forest songbird species richness using LiDAR-derived measures of forest structure. Remote Sensing of Environment 2011, 115, 2823-2835. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, L.; Giam, X.; Papeş, M.; Sheldon, K.S. Metrics of Lidar-Derived 3D Vegetation Structure Reveal Contrasting Effects of Horizontal and Vertical Forest Heterogeneity on Bird Species Richness. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 743.

- Wang, D.; Wan, B.; Liu, J.; Su, Y.; Guo, Q.; Qiu, P.; Wu, X. Estimating aboveground biomass of the mangrove forests on northeast Hainan Island in China using an upscaling method from field plots, UAV-LiDAR data and Sentinel-2 imagery. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2020, 85, 101986. [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, C.; Lejeune, P.; Michez, A.; Fayolle, A. How Can Remote Sensing Help Monitor Tropical Moist Forest Degradation?—A Systematic Review. Remote Sensing 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, L.; Giam, X.; Papeş, M.; Sheldon, K. Metrics of Lidar-Derived 3D Vegetation Structure Reveal Contrasting Effects of Horizontal and Vertical Forest Heterogeneity on Bird Species Richness. Remote Sensing 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- LaRue, E.A.; Wagner, F.W.; Fei, S.; Atkins, J.W.; Fahey, R.T.; Gough, C.M.; Hardiman, B.S. Compatibility of Aerial and Terrestrial LiDAR for Quantifying Forest Structural Diversity. Remote Sensing 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hudak, A.T.; Crookston, N.L.; Evans, J.S.; Falkowski, M.J.; Smith, A.M.S.; Gessler, P.E.; Morgan, P. Regression modeling and mapping of coniferous forest basal area and tree density from discrete-return lidar and multispectral satellite data. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 2006, 32, 126-138. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, G.; Wu, Q.; Ruan, J.; Li, D.; Lu, D. Mapping Forest Carbon Stock Distribution in a Subtropical Region with the Integration of Airborne Lidar and Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 3847.

- Arroyo, L.A.; Johansen, K.; Armston, J.; Phinn, S. Integration of LiDAR and QuickBird imagery for mapping riparian biophysical parameters and land cover types in Australian tropical savannas. Forest Ecology and Management 2010, 259, 598-606. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.B.; Spies, T.A. Estimating structural attributes of Douglas-fir/western hemlock forest stands from landsat and SPOT imagery. Remote Sensing of Environment 1992, 41, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, R.; Kolyaie, S.; Morton, D.C.; Zimmerman, J.K.; Uriarte, M. Effects of topography on tropical forest structure depend on climate context. Journal of Ecology 2020, 108, 145-159. [CrossRef]

- Gracia, M.; Montané, F.; Piqué, J.; Retana, J. Overstory structure and topographic gradients determining diversity and abundance of understory shrub species in temperate forests in central Pyrenees (NE Spain). Forest Ecology and Management 2007, 242, 391-397. [CrossRef]

- Odom, R.; Henry McNab, W. Using digital terrain modeling to predict ecological types in the Balsam mountains of Western North Carolina; RN-SRS008; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station: United States of America, 2000; p. 13.

- Mikita, T.; Klimánek, M.; Miloš, C. Evaluation of airborne laser scanning data for tree parameters and terrain modelling in forest environment. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 2013, LXI, 1339-1347. [CrossRef]

- Yun, Z.; Zheng, G.; Geng, Q.; Monika Moskal, L.; Wu, B.; Gong, P. Dynamic stratification for vertical forest structure using aerial laser scanning over multiple spatial scales. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2022, 114. [CrossRef]

- TERN. Warra Tall Eucalypt SuperSite. Available online: https://www.tern.org.au/tern-ecosystem-processes/warra-tall-eucalypt-supersite/ (accessed on 15 July 2017).

- Bureau of Meteorology. Climate statistics for Australian locations (2004-2017). 2017.

- Hickey, J.E.; Su, W.; Rowe, P.; Brown, M.J.; Edwards, L. Fire history of the tall wet eucalypt forests of the Warra ecological research site, Tamania. Australian Forestry 1999, 62, 66-71. [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.C.; Garandel, M.; Deltombe, M.; Neyland, M.G. Factors influencing initial vascular plant seedling composition following either aggregated retention harvesting and regeneration burning or burning of unharvested forest. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 306, 192-201. [CrossRef]

- Neyland, M.G. Vegetation of the Warra silvicultural systems trial. Tasforests 2001, 13, 183-192.

- Mineral Resources Tasmania. Digital Geological Atlas 1:25,000 Scale Series. Available online: http://www.mrt.tas.gov.au/products/geoscience_maps/digital_geological_atlas_125_000_scale_series (accessed on January 30, 2019).

- Potapov, P.; Li, X.; Hernandez-Serna, A.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C.; Kommareddy, A.; Pickens, A.; Turubanova, S.; Tang, H.; Silva, C.E.; et al. Mapping global forest canopy height through integration of GEDI and Landsat data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2021, 253, 112165. [CrossRef]

- Mäyrä, J.; Keski-Saari, S.; Kivinen, S.; Tanhuanpää, T.; Hurskainen, P.; Kullberg, P.; Poikolainen, L.; Viinikka, A.; Tuominen, S.; Kumpula, T.; et al. Tree species classification from airborne hyperspectral and LiDAR data using 3D convolutional neural networks. Remote Sensing of Environment 2021, 256, 112322. [CrossRef]

- Ferro, J.C.; Warner, T. Scale and texture in digital image classification. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 2002, 68, 51-63.

- Neyland, M.G.; Jarman, S.J. Early impacts of harvesting and burning disturbances on vegetation communities in the Warra silvicultural systems trial, Tasmania, Australia. Australian Journal of Botany 2011, 59, 701-712. [CrossRef]

- Wardlaw, T.J.; Grove, S.J.; Hingston, A.B.; Balmer, J.M.; Forster, L.G.; Musk, R.A.; Read, S.M. Responses of flora and fauna in wet eucalypt production forest to the intensity of disturbance in the surrounding landscape. Forest Ecology and Management 2018, 409, 694-706. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, T.; Skidmore, A.K.; Holzwarth, S.; Heiden, U.; Heurich, M. Mapping individual silver fir trees using hyperspectral and LiDAR data in a Central European mixed forest. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 98, 102311. [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, S.; Saarela, S.; Lindgren, N.; Lindberg, E.; Nyström, M.; Persson, H.; Olsson, H.; Ståhl, G. Assessing Error Correlations in Remote Sensing-Based Estimates of Forest Attributes for Improved Composite Estimation. Remote Sensing 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kuester, M. Radiometric use of WorldView-3 imagery-Technical Note; DigitalGlobe: 1601 Dry Creek Drive, Suite 260, Longmont CO 80503, USA, 2016; pp. 1-12.

- Flood, N. Continuity of reflectance data between Landsat-7 ETM+ and Landsat-8 OLI, for both top-of-atmosphere and surface reflectance: A study in the Australian landscape. Remote Sensing 2014, 6, 7952.

- Thuillier, G.; Hersé, M.; Labs, D.; Foujols, T.; Peetermans, W.; Gillotay, D.; Simon, P.C.; Mandel, H. The solar spectral irradiance from 200 to 2400 nm as measured by the SOLSPEC Spectrometer from the Atlas and Eureca Missions. Solar Physics 2003, 214, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- White, R.J. Searching for rainforest understorey in wet Eucalyptus forest. University Of Tasmania, Hobart, 2017.

- Dobrowski, S.Z.; Safford, H.D.; Cheng, Y.B.; Ustin, S.L. Mapping mountain vegetation using species distribution modeling, image-based texture analysis, and object-based classification. Applied Vegetation Science 2008, 11, 499-508, doi:doi:10.3170/2008-7-18560.

- Ge, S.; Carruthers, R.; Gong, P.; Herrera, A. Texture analysis for mapping Tamarix parviflora using aerial photographs along the Cache Creek, California. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2006, 114, 65-83. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, I.A.; Musk, R.A.; Osborn, J.; Stone, C.; Lucieer, A. A comparison of area-based forest attributes derived from airborne laser scanner, small-format and medium-format digital aerial photography. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2019, 76, 231-241. [CrossRef]

- Imdadullah, M.; Aslam, M.; Altaf, S. mctest: An R package for detection of collinearity among regressors. The R Journal 2016, 8.

- Li, Y.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Liu, Z. Forest aboveground biomass estimation using Landsat 8 and Sentinel-1A data with machine learning algorithms. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 9952. [CrossRef]

- Jaskierniak, D.; Lane, P.N.J.; Robinson, A.; Lucieer, A. Extracting LiDAR indices to characterise multilayered forest structure using mixture distribution functions. Remote Sensing of Environment 2011, 115, 573-585. [CrossRef]

- Martinuzzi, S.; Vierling, L.A.; Gould, W.A.; Falkowski, M.J.; Evans, J.S.; Hudak, A.T.; Vierling, K.T. Mapping snags and understory shrubs for a LiDAR-based assessment of wildlife habitat suitability. Remote Sensing of Environment 2009, 113, 2533-2546. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.J.; Dennison, P.E.; Hudak, A.T.; Parham, L.M.; Butler, B.W. Quantifying understory vegetation density using small-footprint airborne LiDAR. Remote Sensing of Environment 2018, 215, 330-342. [CrossRef]

- Criminisi, A.; Shotton, J.; Konukoglu, E. Decision forests for classication, regression, density estimation, manifold learning and semi-supervised learning. Microsoft Research technical report TR-2011-114 2011, 151.

- Kemppinen, J.; Niittynen, P.; Riihimäki, H.; Luoto, M. Modelling soil moisture in a high-latitude landscape using LiDAR and soil data. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 2018, 43, 1019-1031. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, C.; Meng, R.; Pang, Y.; Jia, W.; Zhou, J.; Huang, Z.; Fang, L.; Zhao, F. Assessing Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 spectral-temporal features for mapping tree species of northern plantation forests in Heilongjiang Province, China. For. Ecosyst. 2022, 9, 100032. [CrossRef]

- van Galen, L.G.; Jordan, G.J.; Musk, R.A.; Beeton, N.J.; Wardlaw, T.J.; Baker, S.C. Quantifying floristic and structural forest maturity: An attribute-based method for wet eucalypt forests. Journal of Applied Ecology 2018, 55, 1668-1681, doi:doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13133.

- Astola, H.; Häme, T.; Sirro, L.; Molinier, M.; Kilpi, J. Comparison of Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 imagery for forest variable prediction in boreal region. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 223, 257-273. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5-32. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.M.; Iverson, L.R.; Liaw, A. Newer classification and regression tree techniques: Bagging and random forests for ecological prediction. Ecosystems 2006, 9, 181-199. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.A.; Moisen, G.G.; Coulston, J.W.; Wilson, B.T. Random forests and stochastic gradient boosting for predicting tree canopy cover: comparing tuning processes and model performance. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2015, 46, 323-339. [CrossRef]

- Valbuena, R.; Hernando, A.; Manzanera, J.A.; Görgens, E.B.; Almeida, D.R.A.; Silva, C.A.; García-Abril, A. Evaluating observed versus predicted forest biomass: R-squared, index of agreement or maximal information coefficient? European Journal of Remote Sensing 2019, 52, 345-358. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing, version 3.4.1, 3.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Freely available at https://www.r-project.org/, 2017.

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News 2002, pp. 18-22.

- Tuszynski, J. Tools: Moving Window Statistics, GIF, Base64, ROC AUC, etc. R package Version 1.18.0, 2020.

- Genuer, R.; Poggi, J.-M.; Tuleau-Malot, C. VSURF: An R package for variable selection using random forests. The R Journal 2015, 7, 19-33.

- Yadav, B.K.V.; Lucieer, A.; Jordan, G.J.; Baker, S.C. Using topographic attributes to predict the density of vegetation layers in a wet eucalypt forest. Australian Forestry 2022, 85, 25-37. [CrossRef]

- Dube, T.; Mutanga, O. Investigating the robustness of the new Landsat-8 Operational Land Imager derived texture metrics in estimating plantation forest aboveground biomass in resource constrained areas. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2015, 108, 12-32. [CrossRef]

- Latifi, H.; Nothdurft, A.; Straub, C.; Koch, B. Modelling stratified forest attributes using optical/LiDAR features in a central European landscape. International Journal of Digital Earth 2012, 5, 106-132. [CrossRef]

- Azaele, S.; Cornell, S.J.; Kunin, W.E. Downscaling species occupancy from coarse spatial scales. Ecological Applications 2012, 22, 1004-1014, doi:doi:10.1890/11-0536.1.

- Munsamy, R.; Gebreslasie, M.; Peerbhay, K.; Ismail, R. Modelling the effect of terrain variability in even-aged Eucalyptus species using LiDAR-derived DTM variables. South African Journal of Geomatics 2020, 9, 118-135. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.K.V.; Lucieer, A.; Baker, S.C.; Jordan, G.J. Tree crown segmentation and species classification in a wet eucalypt forest from airborne hyperspectral and LiDAR data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2021, 42, 7952-7977. [CrossRef]

- Wallner, A.; Elatawneh, A.; Knoke, T.; Schneider, T. Estimation of forest structural information using RapidEye satellite data. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 2014, 88, 96-107. [CrossRef]

- Halperin, J.; LeMay, V.; Coops, N.; Verchot, L.; Marshall, P.; Lochhead, K. Canopy cover estimation in miombo woodlands of Zambia: Comparison of Landsat 8 OLI versus RapidEye imagery using parametric, nonparametric, and semiparametric methods. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 179, 170-182. [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, V.; Darvishsefat, A.A.; Arefi, H.; Griess, V.C.; Sadeghi, S.M.M.; Borz, S.A. Modeling Forest Canopy Cover: A Synergistic Use of Sentinel-2, Aerial Photogrammetry Data, and Machine Learning. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1453. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ren, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Man, W.; Liu, J. Improved estimation of forest stand volume by the integration of GEDI LiDAR data and multi-sensor imagery in the Changbai Mountains Mixed forests Ecoregion (CMMFE), northeast China. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 100, 102326. [CrossRef]

- Soh, L.-K.; Tsatsoulis, C. Texture analysis of SAR sea ice imagery using gray level co-occurrence matrices. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 1999, 37, 780-795. [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1973, SMC-3, 610-621. [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sensing of Environment 1996, 58, 289-298. [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Remote sensing of chlorophyll concentration in higher plant leaves. Advances in Space Research 1998, 22, 689-692. [CrossRef]

- Crippen, R.E. Calculating the vegetation index faster. Remote Sensing of Environment 1990, 34, 71-73. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Willis, P.; Mueller, R. Impact of band-ratio enhanced AWIFS image on crop classification accuracy. In Proceedings of the Pecora 17 – The Future of Land Imaging…Going Operational, Denver, Colorado, November 18 – 20, 2008, 2008; p. 11.

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A modified soil adjusted vegetation index. Remote Sensing of Environment 1994, 48, 119-126. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M. Evaluation of vegetation indices and a modified simple ratio for boreal applications. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 1996, 22, 229-242. [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.S.; Qin, W. Influences of canopy architecture on relationships between various vegetation indices and LAI and Fpar: A computer simulation. Remote Sensing Reviews 1994, 10, 309-347. [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.; Haas, R.; Schell, J.; Deering, D. Monitoring vegetation systems in the great plains with ERTS. In Proceedings of the Third ERTS Symposium, NASA, United States, 1973; pp. 309-317.

- Roujean, J.-L.; Breon, F.-M. Estimating PAR absorbed by vegetation from bidirectional reflectance measurements. Remote Sensing of Environment 1995, 51, 375-384. [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of soil-adjusted vegetation indices. Remote Sensing of Environment 1996, 55, 95-107. [CrossRef]

- Marsett, R.C.; Qi, J.; Heilman, P.; Biedenbender, S.H.; Carolyn Watson, M.; Amer, S.; Weltz, M.; Goodrich, D.; Marsett, R. Remote sensing for grassland management in the arid southwest. Rangeland Ecology & Management 2006, 59, 530-540. [CrossRef]

- Hagen, S.C.; Heilman, P.; Marsett, R.; Torbick, N.; Salas, W.; van Ravensway, J.; Qi, J. Mapping total vegetation cover across western rangelands with moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer data. Rangeland Ecology & Management 2012, 65, 456-467. [CrossRef]

- Torbick, N.; Ledoux, L.; Salas, W.; Zhao, M. Regional mapping of plantation extent using multisensor imagery. Remote Sensing 2016, 8, 236.

- Key, C.H.; Benson, N.C. Landscape assessment: Ground measure of severity, the composite burn index; and remote sensing of severity, the normalized burn ratio. In FIREMON: Fire Effects Monitoring and Inventory System, RMRS-GTR-164 ed.; D.C. Lutes, R.E.K., J.F. Caratti, C.H. Key, N.C. Benson, S. Sutherland, L.J. Gangi, Ed.; USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden, UT: Ogden, UT, 2006; p. 56.

- Ji, L.; Zhang, L.; Wylie, B.; Rover, J. On the terminology of the spectral vegetation index (NIR − SWIR)/(NIR + SWIR). International Journal of Remote Sensing 2011, 32, 6901-6909. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Huang, J.; Jackson, T.J. Vegetation water content estimation for corn and soybeans using spectral indices derived from MODIS near- and short-wave infrared bands. Remote Sensing of Environment 2005, 98, 225-236. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Hong, Y.; Qin, Q.; Zhu, L. Evaluation of the visible and shortwave infrared drought index in China. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2013, 4, 68-76. [CrossRef]

| Specification item | WorldView-3 Imagery | Landsat-8 Imagery |

|---|---|---|

| Date of acquisition | 2015-10-05 | 2014-10-21 |

| Spatial resolution | 1.60 m (VNIR bands) 7.50 m (SWIR bands) |

30 m (VNIR and SWIR bands) |

| Sun azimuth | 42.400 | 48.800454560 |

| Sun Elevation | 43.700 | 48.182282610 |

| Product Type Level | "Standard" LV2A | OLI_TIRS_L1TP |

| Bands (In Nanometres) |

Coastal = 427.40 Blue = 481.90 Green = 547.10 Yellow = 604.30 Red = 660.10 Red Edge = 722.70 NIR1= 824.00 NIR2 = 913.60 SWIR1 = 1209.10 SWIR2= 1571.60 SWIR3= 1661.10 SWIR4= 1729.50 SWIR5= 2163.70 SWIR6= 2202.20 SWIR7= 2259.30 SWIR8= 2329.20 |

Coastal = 442.96 Blue = 482.04 Green = 561.41 Red = 654.59 NIR = 864.67 SWIR 1 = 1608.86 SWIR 2 = 2200.73 |

| Band | Gain value | Offset value | Solar irradiance value (W-M-2 −μm-1) [66] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal | 0.863 | -7.154 | 1757.89 |

| Blue | 0.905 | -4.189 | 2004.61 |

| Green | 0.907 | -3.287 | 1830.18 |

| Yellow | 0.938 | -1.816 | 1712.07 |

| Red | 0.945 | -1.350 | 1535.33 |

| Red-Edge | 0.980 | -2.617 | 1348.08 |

| NIR 1 | 0.982 | -3.752 | 1055.94 |

| NIR 2 | 0.954 | -1.507 | 858.77 |

| SWIR 1 | 1.160 | -4.479 | 479.019 |

| SWIR 2 | 1.184 | -2.248 | 263.797 |

| SWIR 3 | 1.173 | -1.806 | 225.283 |

| SWIR 4 | 1.187 | -1.507 | 197.552 |

| SWIR 5 | 1.286 | -0.622 | 90.4178 |

| SWIR 6 | 1.336 | -0.605 | 85.0642 |

| SWIR 7 | 1.340 | -0.423 | 76.9507 |

| SWIR 8 | 1.392 | -0.302 | 68.0988 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).