Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

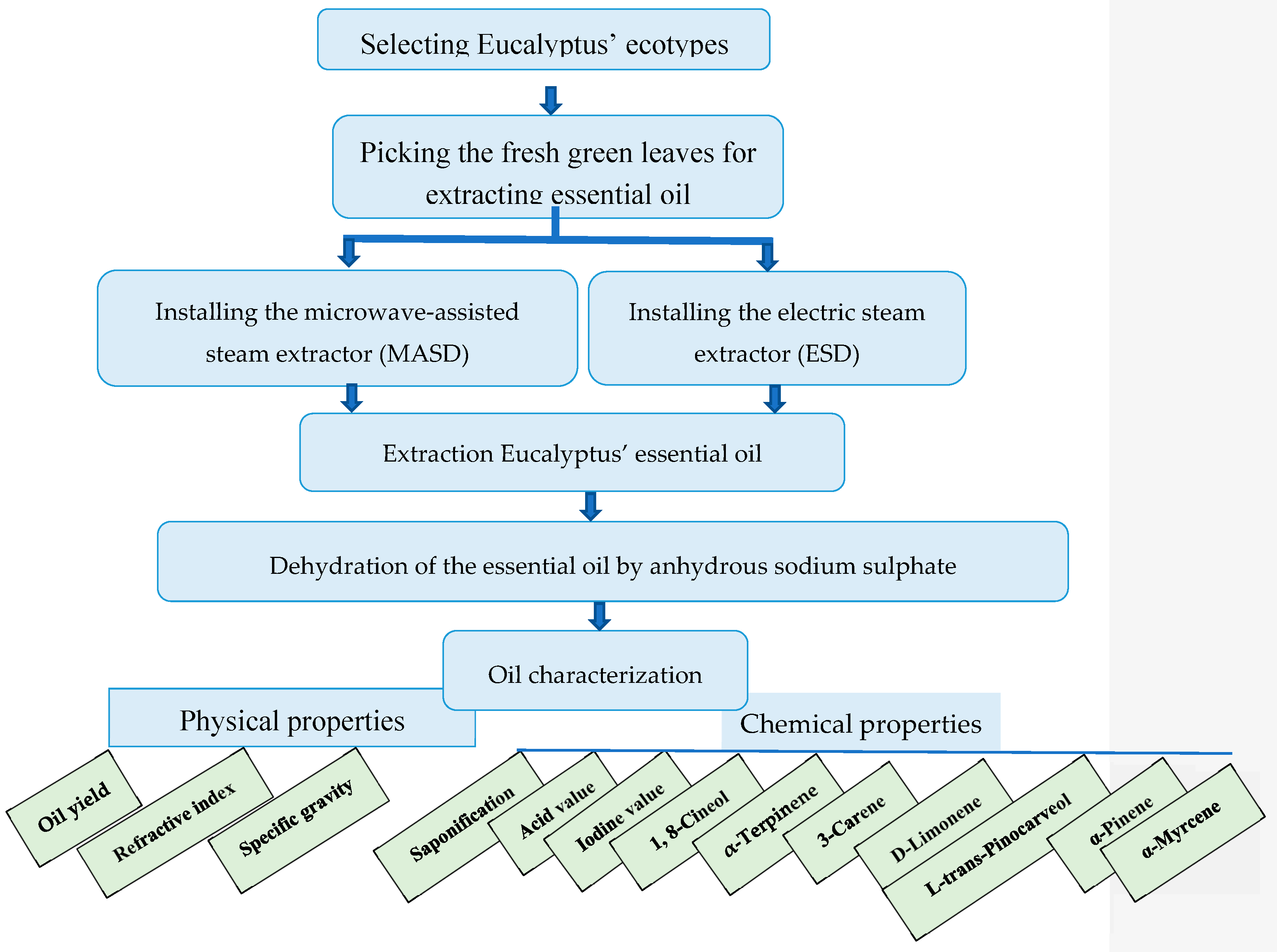

2.1. The Management Plan

2.2. Tree Species

2.2.1. Sprouts of the Selected Trees

2.2.2. Leaves’ Raw Materials

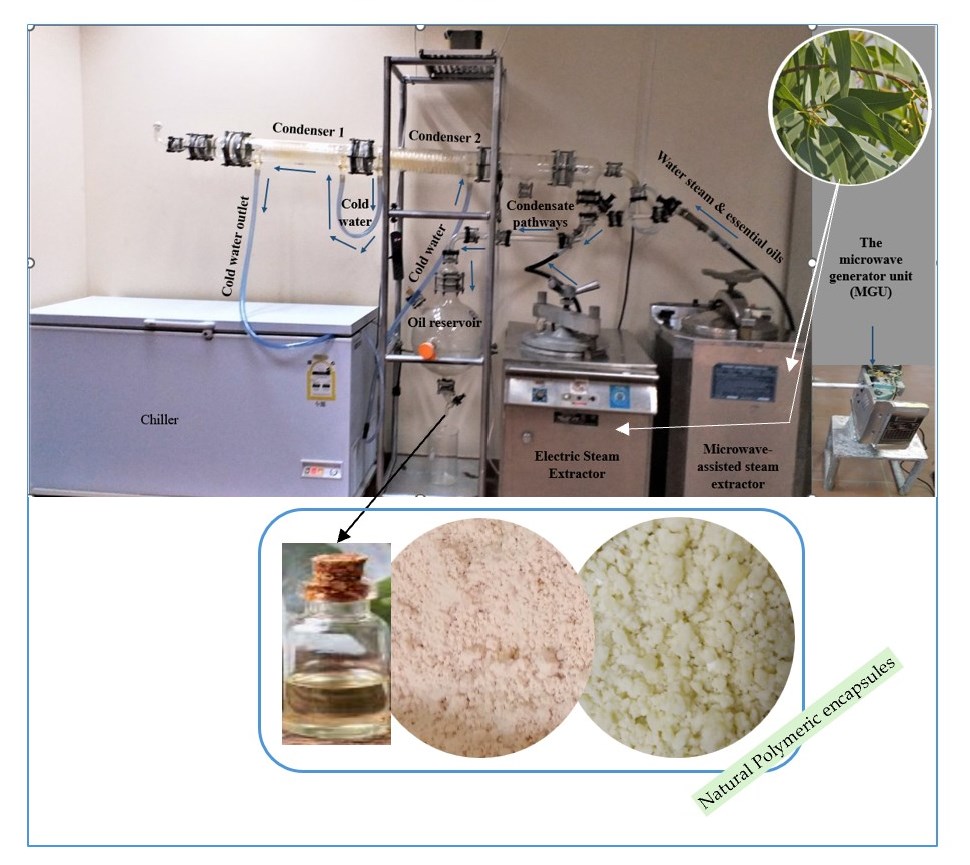

2.2.3. The Microwave-Assisted Steam Distillation (MASD)

2.2.4. Electric Steam Distillation (ESD) Apparatus

2.3. Essential Oil Extraction Process

2.4. Characterizations Essential Oils

2.4.1. Physical Characterization of the Essential Oil

2.4.2. Chemical Analysis

- I.

- Chemi.cal Behaviour of the EEO

- II.

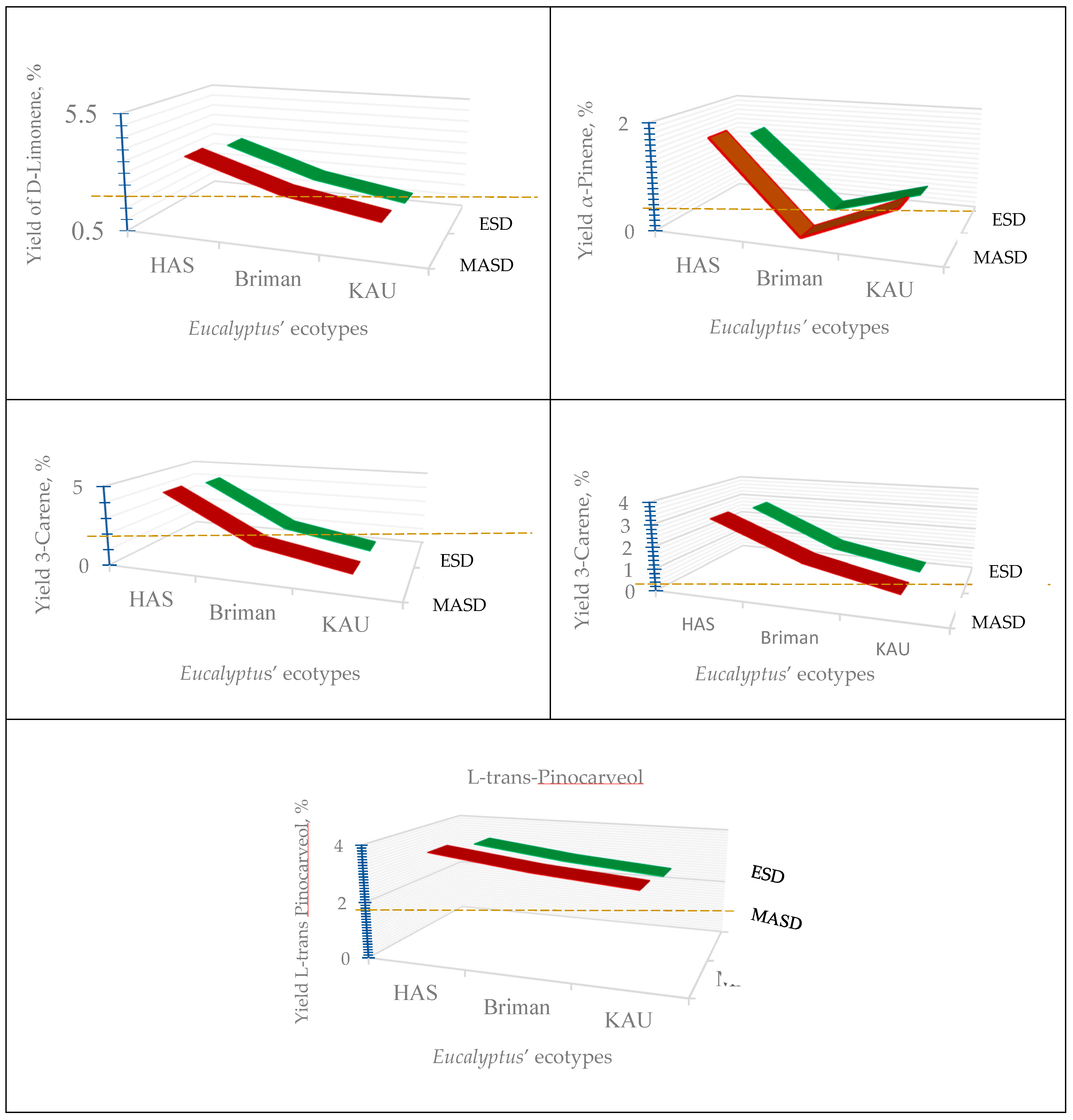

- Fractionated Compounds by GC-MS Analysis

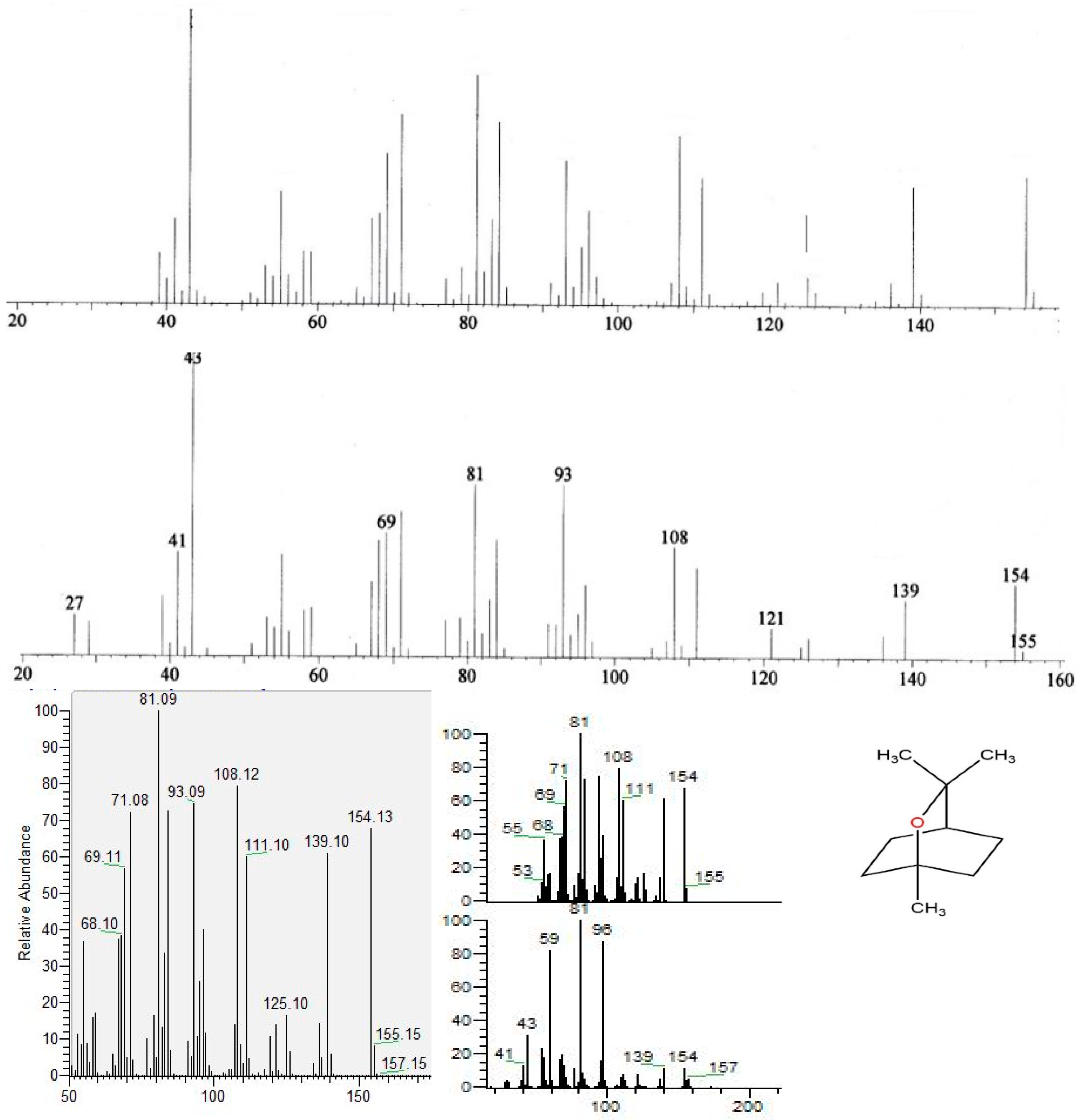

2.4.3. Anatomical Features of the Leave-Tissues Bearing the Essential Oil

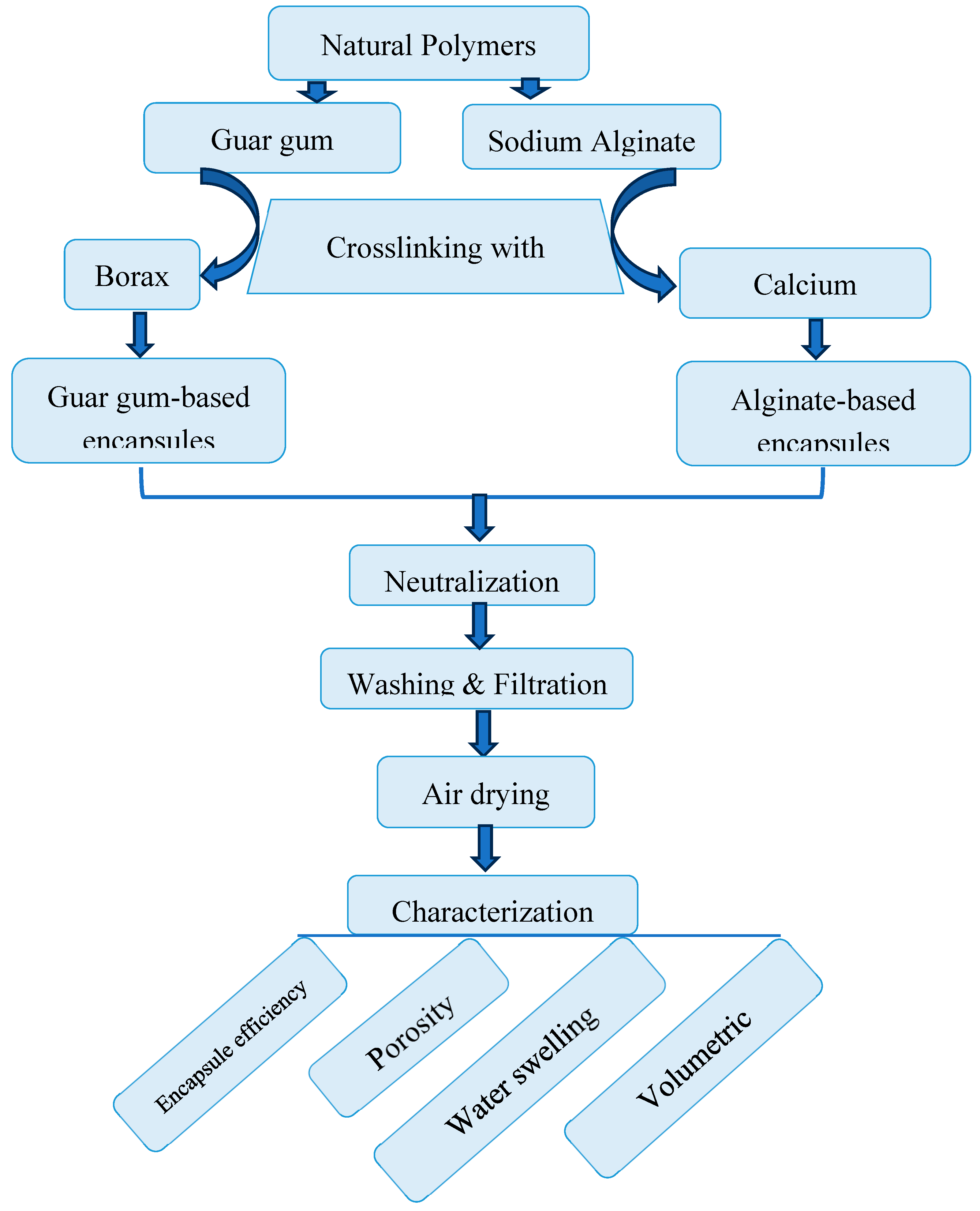

2.5. Microencapsulation

2.5.1. Preparation of Microcapsules

2.5.2. Uploading the Essential Oil’ s Solution Within the Microcapsules

2.5.3. Characterization of the Microcapsules

2.5.4. Bioassay Screening of the Encapsules Against Termite Control [52,53,54]

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical Properties of the Essential Oils

3.1.1. Essential Oil Yield (EOY)

3.1.2. Refractive Index (RI)

3.1.3. Specific Gravity (SG)

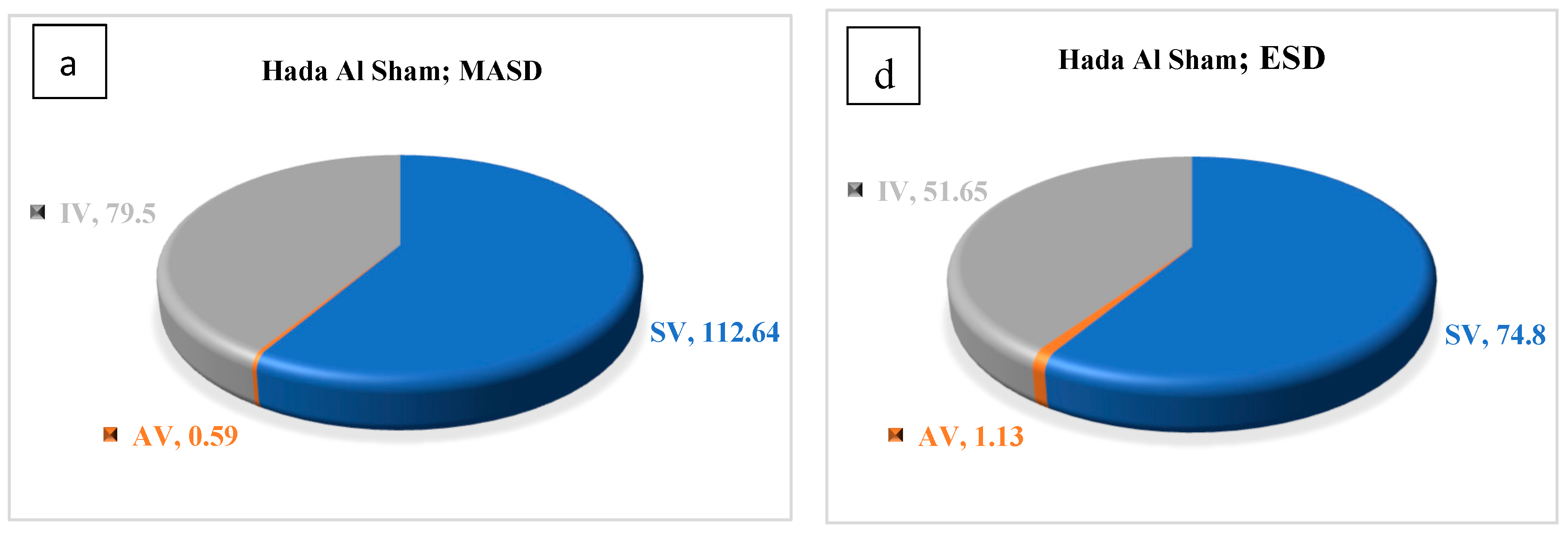

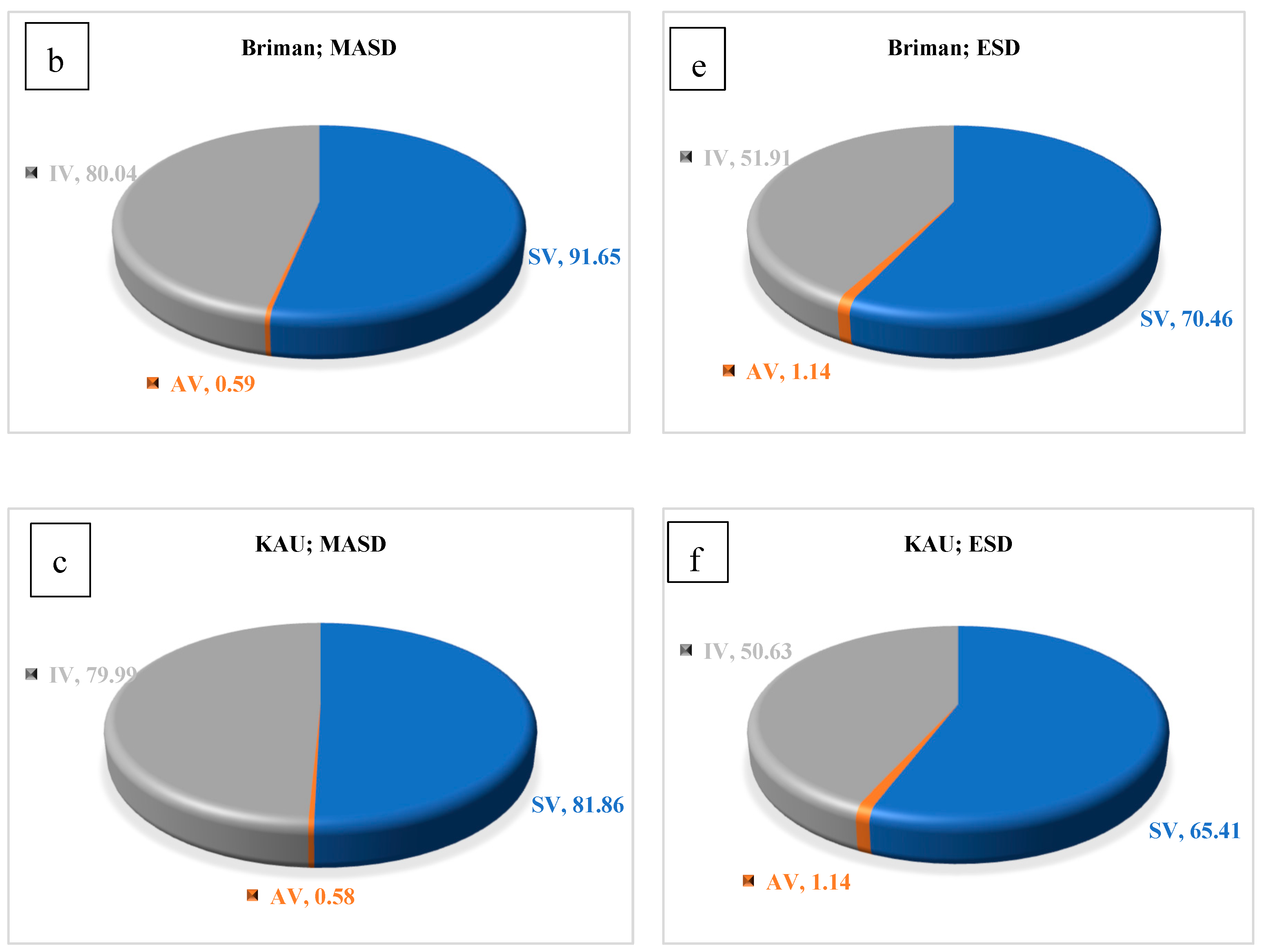

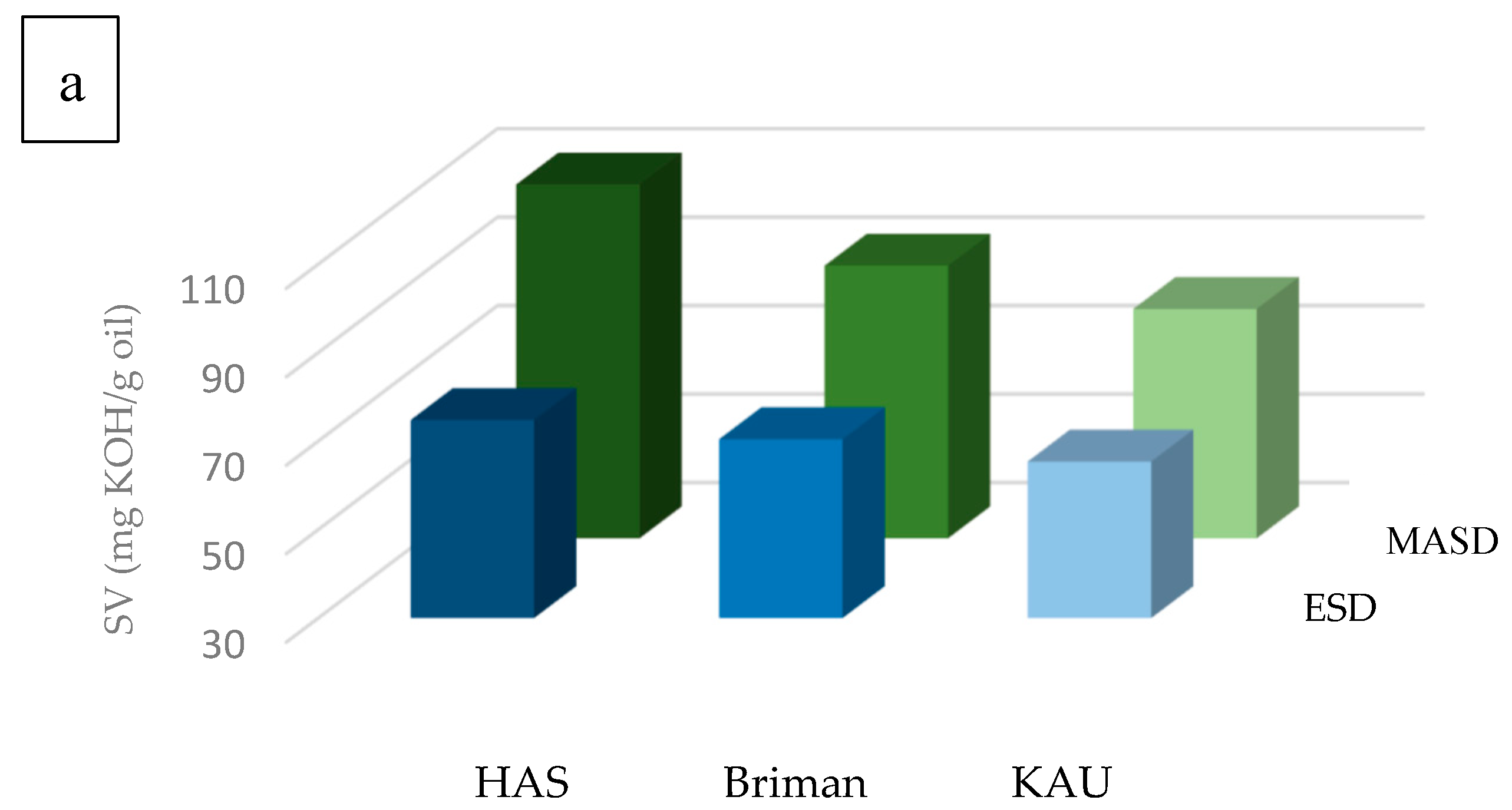

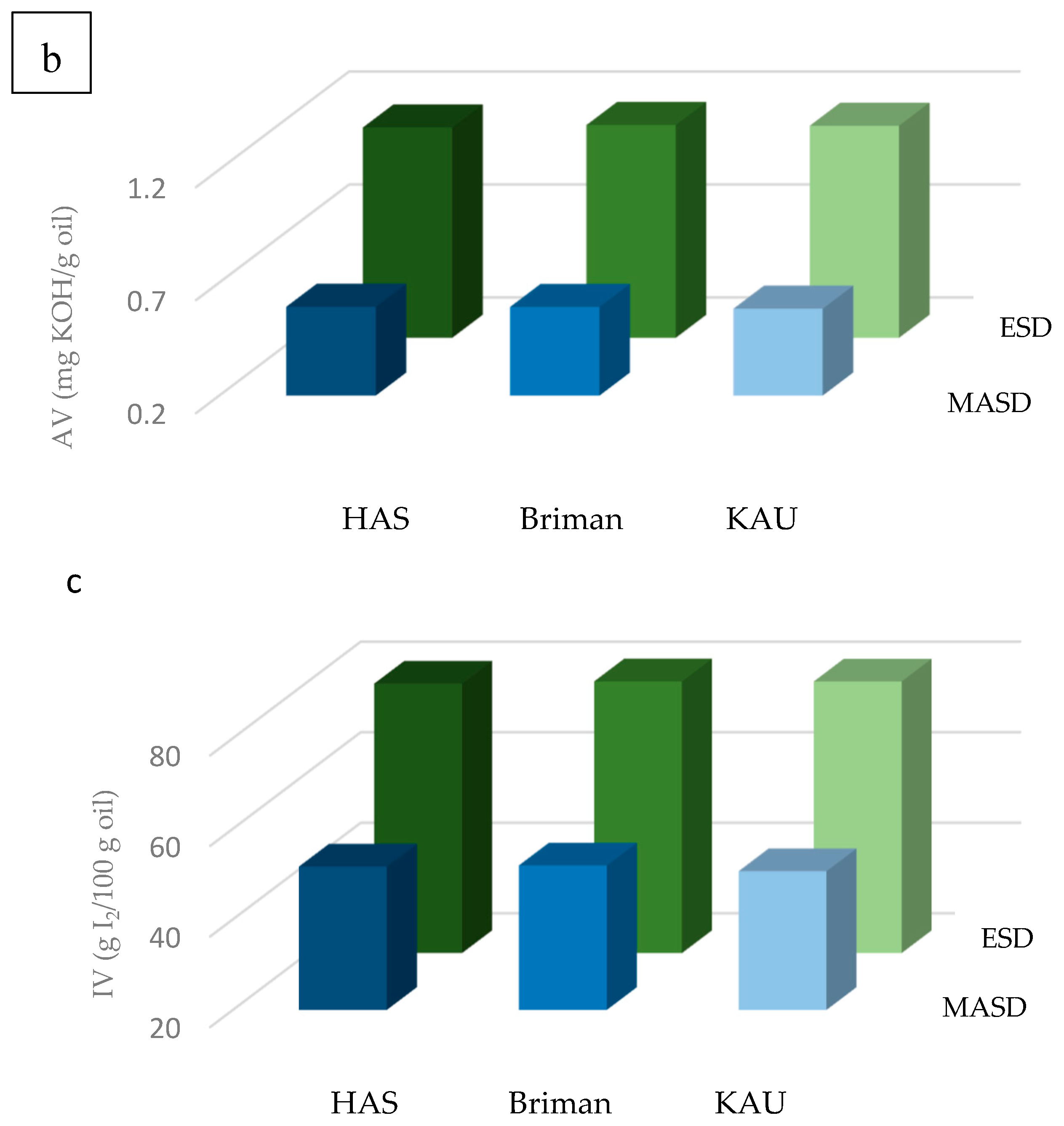

3.2. Chemical Properties of the Essential Oils

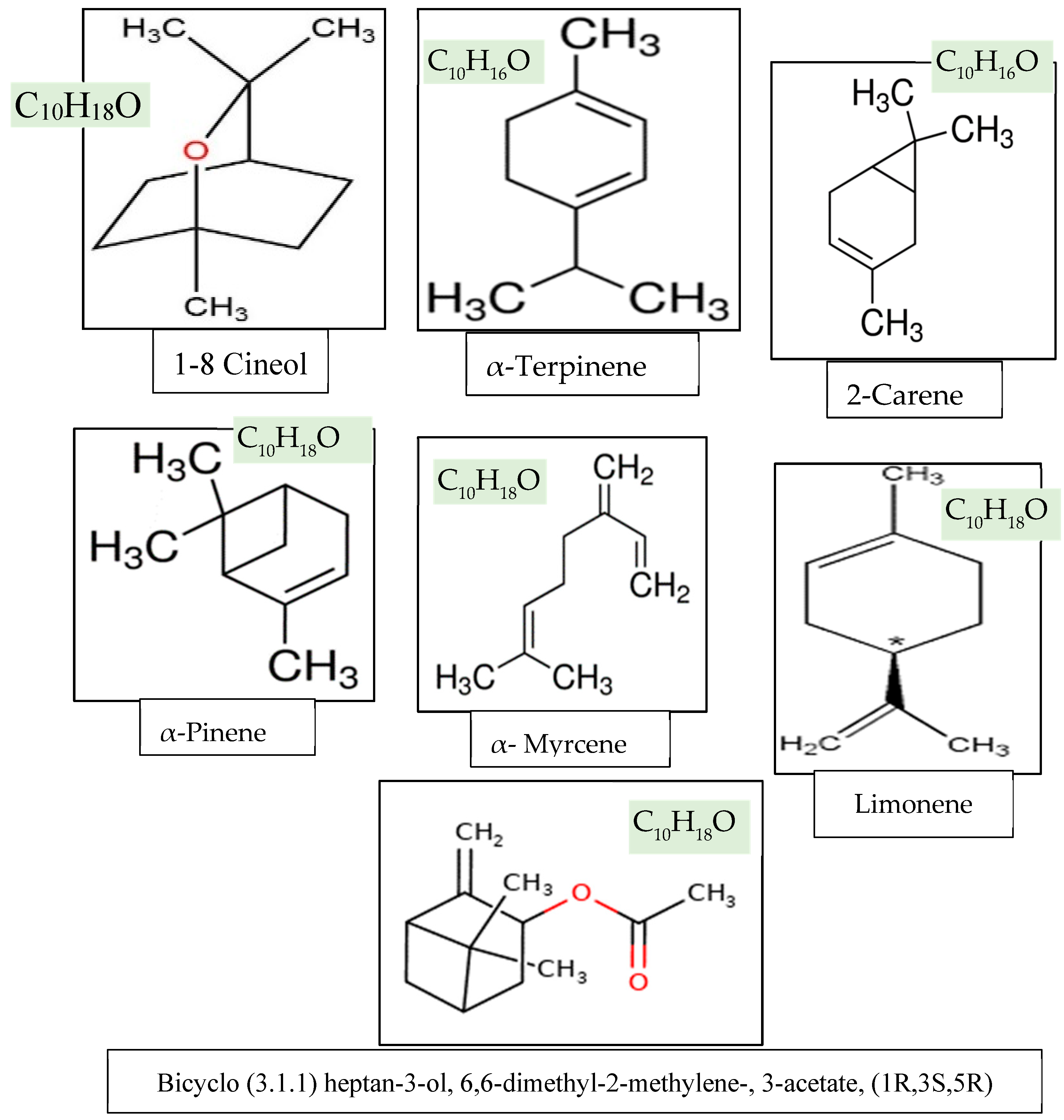

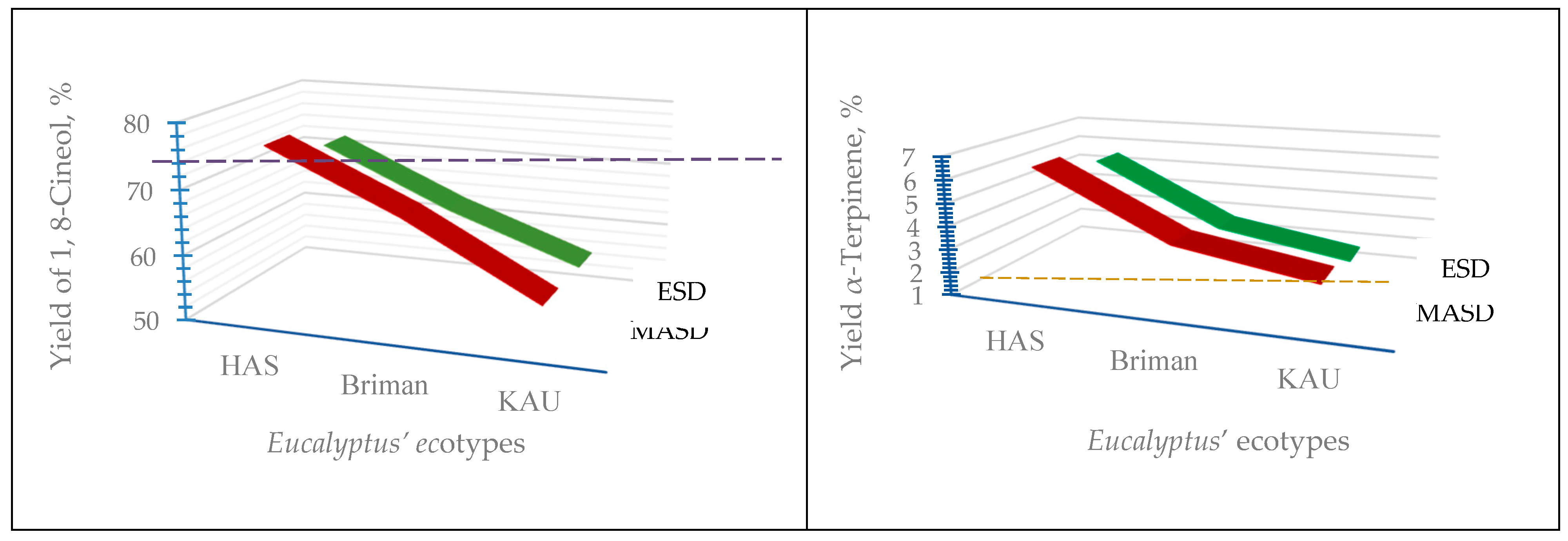

3.3. Chemical Constituents of the Essential oil

3.4. Microwave Theory Operation

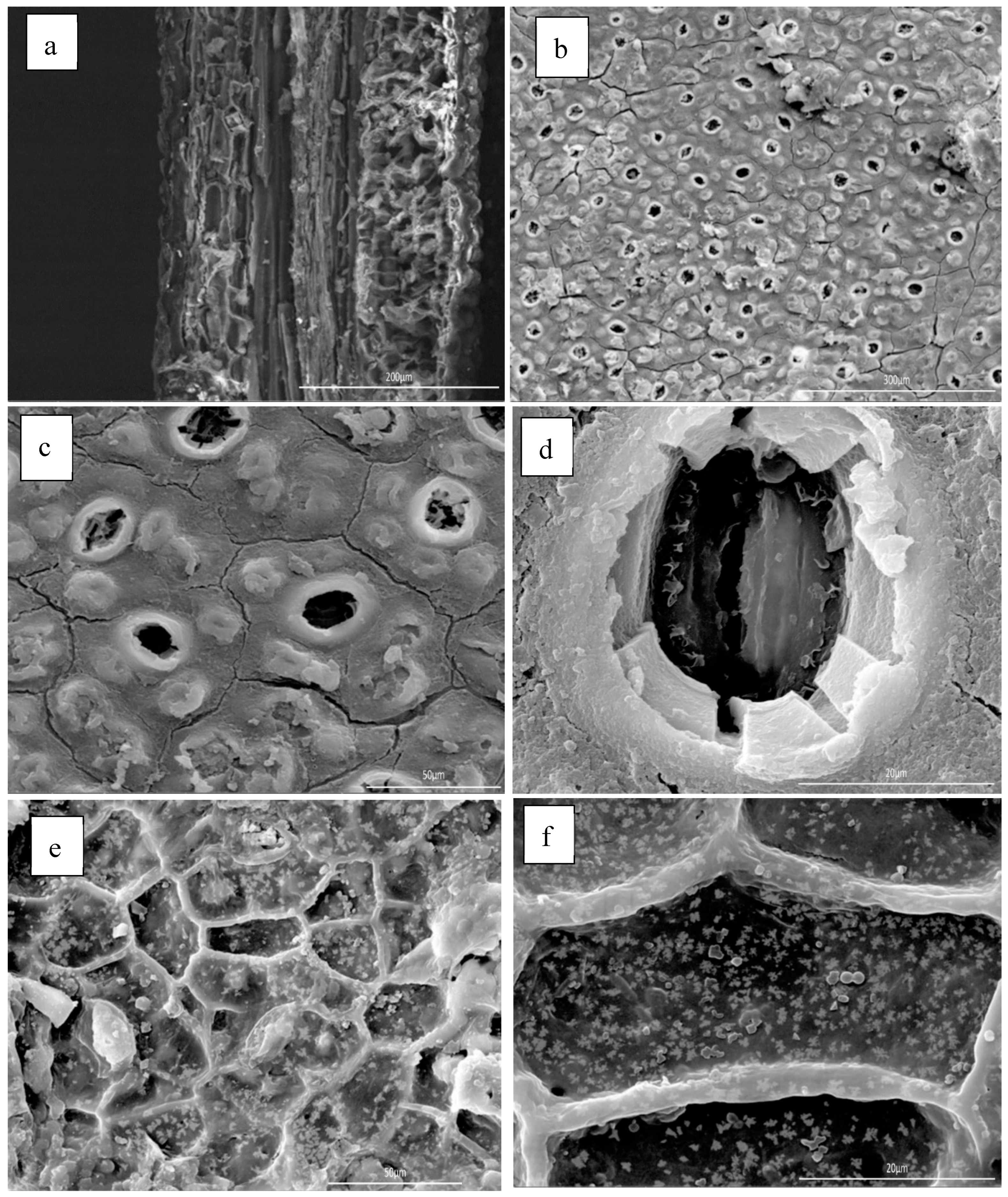

3.5. Effect of Microwave Irradiation on the Leaves’ Tissues Bearing the Essential Oil

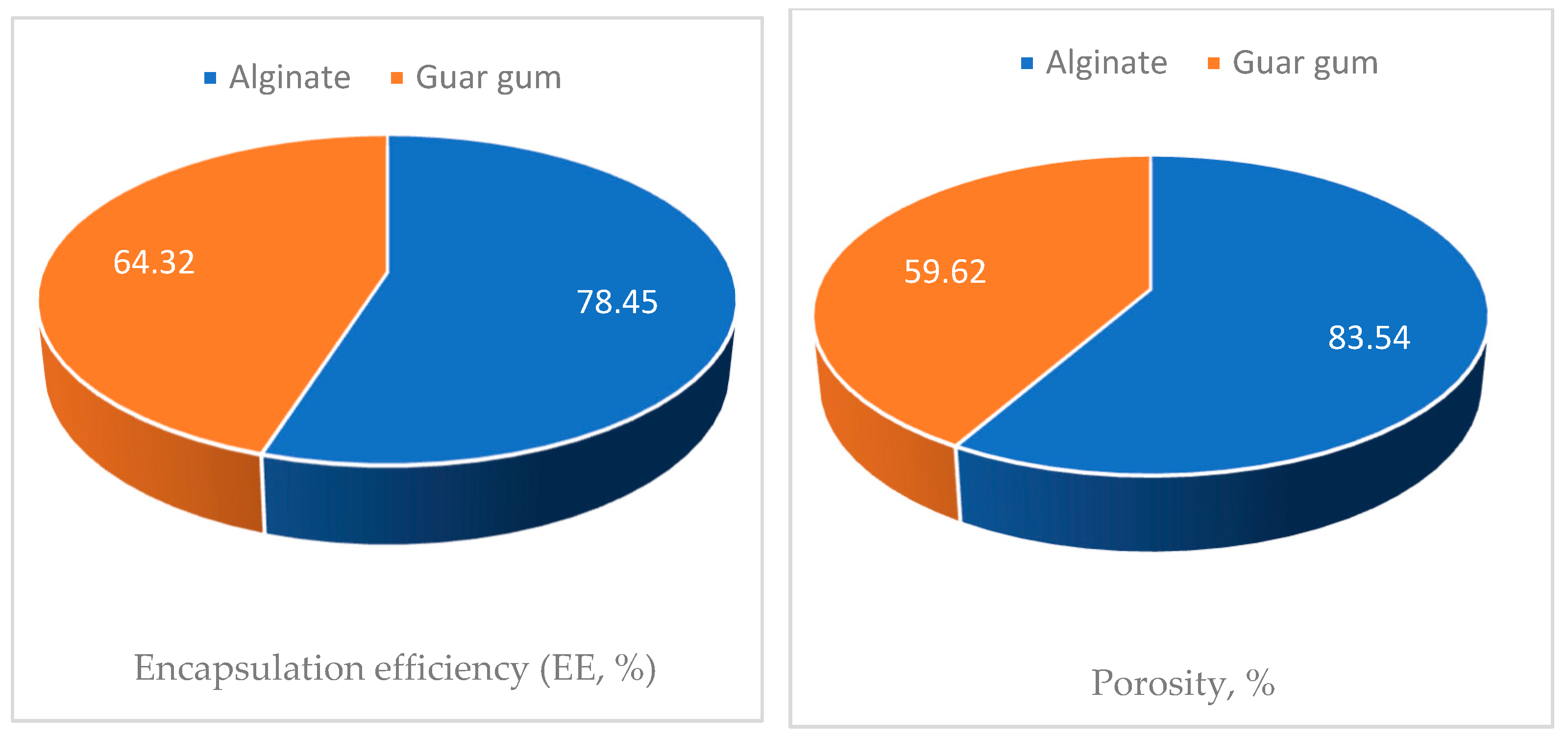

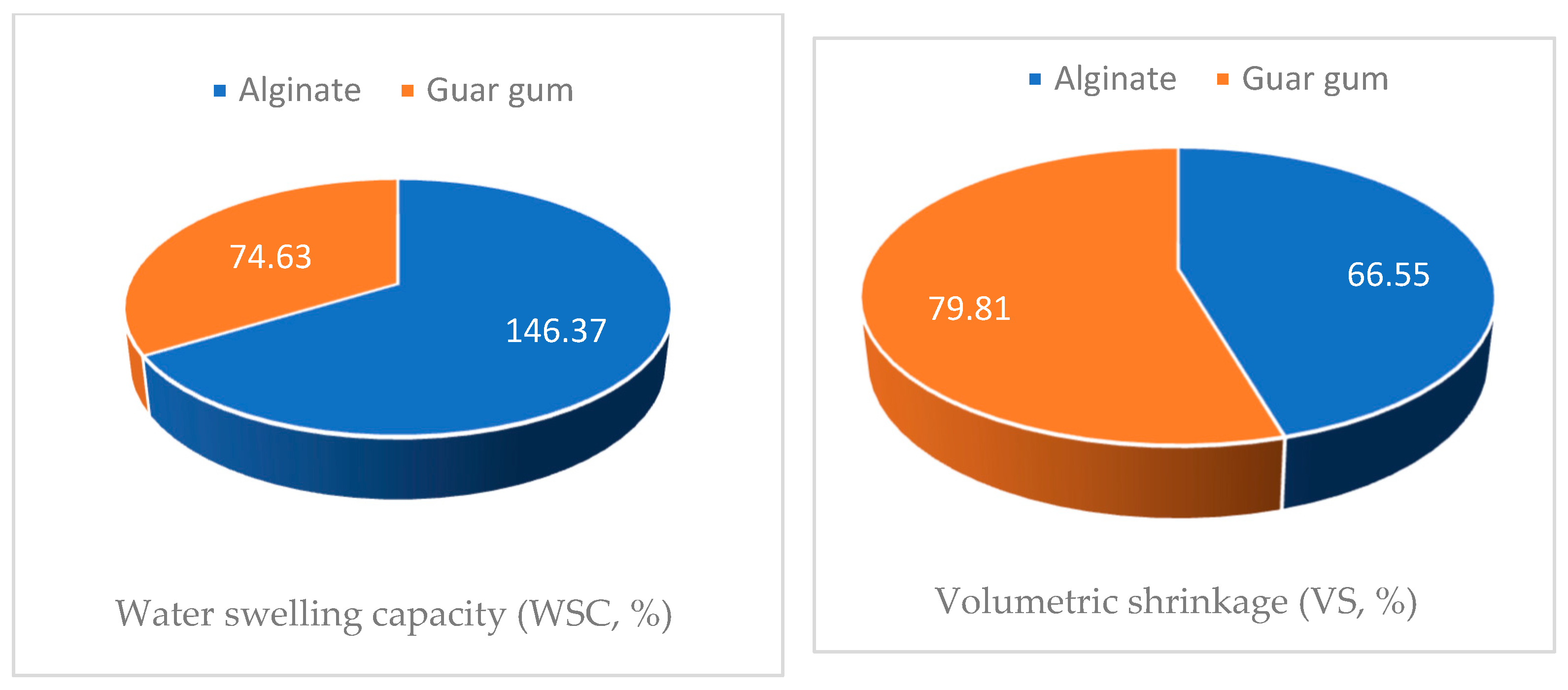

3.6. Characterization of the Microcapsules

3.7. Bioassay Screening of the Encapsules Against Termite Control

4. Conclusions

5. Future Perspectives

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Definition | Symbol | Definition |

| AC | Alternate current | MAEO | Microwave-assisted extracted oil |

| ACS | The American Chemical Society | MFT | Maximum final temperature |

| ADB | Air-dried membranes | MGU | Microwave generator unit |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy | MHPM | Microwave hot pressing machine |

| ANOVA | The analysis of variance | ||

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials | NDB | Nanodehydrated-bioplastic membrane |

| AV | Acid value | NIST | The National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| BST | Biopolymeric Structured-Tissues | NPS | Nanometric particle Size |

| OY | Oil yield | ||

| CI | Crystallinity index | PD | Pore diameter |

| CLB | Compound lipid bodies | pH | The acidity or basicity number |

| CW | Cell walls | PS | Particle size |

| CY | Cytoplasm | PubChem | An open chemistry database managed by the National Institutes of Health (NHI) |

| DC | Direct current | PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry | ||

| DTA | Differential thermal analysis | RI | Refractive index |

| EC | Endosperm cells | RT | Residence time |

| EHPO | Electric hot pressed oil | ||

| EHPM | Electric-hot pressing machine | SD | Standard deviation |

| ES | Essential oil | SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| ESD | Electric steam distillation | ||

| FEG | Field Emission Gun in the SEM | SEP | Self-electrostatic peeling |

| FEI | Field Electron and Ion US-Company | SG | Specific gravity |

| FOY | Fixed Oil Yield | SLB | Singular lipid bodies |

| SOV | Source of variation | ||

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy | SP | Statistical parameters |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass spectrometer | SR | Surface roughness |

| GHz | Frequency | SV | Saponification value |

| HC | Heat change in µVs/mg | SWC | Sinusoidal wave curve |

| HPM | Hot pressing machine | TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| HVT | High voltage transformer | TR | Temperature range |

| IN | Iodine number | VFHF | Vibrated-free horizontal flow |

| LSD | Least significant differencce | VV | Void volume |

| XRD | X-Ray diffraction |

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Equation | Definitions |

|---|---|

| 1 EOY, % = (W1/W2) ×100 | W1: The essential oil weight, g., W2: The fresh leaves weight, g. |

| 2 SGEO, % = (V1 / V2)× 100 | |

| 3 IN = 12.69×C ×(V1-V2)/W | C, V1, V2: Parameters of sodium thiosulphate. C: Concentration. V1: The volume used for the blank test. V2: The volume used for the fixed oil. W: The fixed oil weight. |

| 4 SV = 56.1N × (V1-V2)/W | V1: The solution volume used for the blank test. V2: The solution volume used for fixed oil. N: The actual normality of the HCl used. W: The fixed oil weight. |

| 5 AV=5.61(V×N)/W | V: Volume of KOH IN mL. N: normality of KOH. W: the fixed oil weight. |

| 6 EE, % = [(W1-W2)/W2] × 100 | W1: Volume of the essential oil in the encapsule after a known period, cm3. W2: Volume of the initial volume of essential oil within the same encapsule, cm3. |

| 7 VVE, % = (1- Vod) × 100 | Vod: Oven-dried volume of the encapsules. |

| 8 WSC, %= [(Ws-Wᴼ)/ Wᴼ] × 100 | Ws: the weight of microcapsule in swollen state. Wᴼ : the initial weight of microcapsules. |

| 9 VSE, % = [(Vad -Vod)/ Vod] × 100 | Vad: Air-dried certain volume of encapsules. Vod: Oven-dried volume of the encapsules. |

Appendix D

Appendix E

| Property | Chemical compound | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer | Crosslinker | ||||

| Guar gum | Alginate | Borax | Calcium chloride | ||

| Chemical structure |  |

|

|

|

|

| Chemical formula | C10H14N5Na2O12P3 | (C6 H7 O6Na)n | Na₂B₄O₇. 10 H₂O | CaCl₂ | |

| Molar mass, g/mol | 50,000 to 8,000,000 | 10000 - 600000 | 381.37 | 111 | |

| Density, g/cm3 | 0.8-1.0 | 1-1.03 | 1.73 | 2.15 | |

| Melting Point | at 1.013 hPa, °C | > 100 | 99 | 75 | 775 ° |

| Boiling Point | 220 | 495.2 °C | 1575 | 1935 | |

| pH (in aqueous solution: 100 g/l, 20 °C) | 5.5-6.2 | 5.5-7.5 | 9-9.5 | 8 – 10 | |

| Solubility, g/l | Soluble in hot water (95 °C) | Slowly soluble in water forming a viscous, colloidal solution, practically insoluble in ethanol (96 per cent) | 49.74 | 745 | |

| Color | Yellow White | Dark yellow | White | White | |

| Odor | Odorless | Odorless | Odorless | Odorless | |

| IUPAC Name | Sodium 3,4,5,6-tetrahydroxyoxane-2-carboxylate | disodium;3,7-dioxido-2,4,6,8,9-pentaoxa-1,3,5,7-tetraborabicyclo [3.3.1]nonane | Calcium dichloride | ||

References

- Ribeiro, B.S.; Ferreira, M. de F.; Moreira, J.L.; Santos, L. Simultaneous distillation–extraction of essential oils from Rosmarinus officinalis L. Cosmetics. 2021, 8, 117. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.S.; Imran, M.; Ahmad, M.H.; et al. Eucalyptus essential oils. Essent. Oils Extr. Charact. Appl. 2023, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassem, H.H.A; Nour, A.H.; Yunus, R.M. Australian Journal of basic and applied sciences techniques for extraction of essential oils from plants: A Review. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2016, 10, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, G. D. K.; Singh, B. Simulation of Eucalyptus cinerea oil distillation: A study on optimization of 1,8-cineole production. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2009, 44, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manguro, L.O.A.; Opiyo, S.A.; Asefa, A.; et al. Chemical constituents of essential oils from three Eucalyptus species acclimatized in Ethiopia and Kenya. J. Essent. Oil Bear Plants. 2010, 13:561–567. 5: 13. [CrossRef]

- Manika, N.; Chanotiya, C.S.; Negi, M.P.S.; Bagchi, G.D. Copious shoots as a potential source for the production of essential oil in Eucalyptus globulus. Indust. Crops Prod. 2013, 46, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodger. J.Q.D.; Senaratne, S.L.; Nicolle, D.; Woodrow, I.E. Correction: Foliar eessential oil glands of Eucalyptus Subgenus Eucalyptus (Myrtaceae) are a rich source of flavonoids and related non-volatile constituents. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0155568. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Miyamoto, A.; Nguyen, H.T.; et al. Short communication: Antibacterial effects of essential oils from Cinnamomum cassia bark and Eucalyptus globulus leaves–The involvements of major constituents. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0288787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, M.V.; Morais, S.M.; Bevilaqua, C.M.L.; et al. Chemical composition of Eucalyptus spp. essential oils and their insecticidal effects on Lutzomyia longipalpis. Vet Parasitol. 2010, 167, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbenou, J.D.; Ahounou, J.F.; Akakpo, H.B.; et al. Phytochemical composition of Cymbopogon citratus and Eucalyptus citriodora essential oils and their anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties on Wistar rats. Mol Biol Rep. 2013, 40, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, D.J.; Brooker, M.I.H.; Chippendale, G.M.; Hall, N.; Hyland, B.P.M.; Johnston, R.D.; Kleinig, D.A.; Turner, J.D. Forest trees of Australia, Nelson and CSIRO, Melbourne (1984). J.C. Shieh, i. Taiwan J. For. Sc 1996, 11, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Ayinde, B. A. Essential oils in food preservation, flavor and safety. In Chapter 46: Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus citriodora Hook., Myrtaceae) Oils. Academic Press, 2016, 413-419.

- Silva, X.; Asiegbu, F.O. Eucalyptus fungal diseases. Forest microbiology, tree diseases and pests. 2023, 3, 313-337.

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils – A review. Food Chem Toxicol 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnke, P.H.; Becker, S.T.; Podschun, R.; et al. The battle against multi-resistant strains: Renaissance of antimicrobial essential oils as a promising force to fight hospital-acquired infections. J Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surg. 2009, 37,392–397. [CrossRef]

- Fokou, J.B.H.; Dongmo, P.M.J.; Boyom, F.F.; et al. Essential oil’s chemical composition and pharmacological properties. Essent Oils - Oils Nat. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Karimi Karemu C; Ndung’U MW; Githua M. Repellent effects of essential oils from selected eucalyptus species and their major constituents against Sitophilus zeamais (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect. Sci. 2013, 33, 188–194. [CrossRef]

- Sandner, G.; Heckmann, M.; Weghuber, J. Immunomodulatory activities of selected essential oils. Biomolec. 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, C.; Stintzing, F.C. Stability of Essential Oils: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiew, C.W.; Lee, L.J.; Junus, S.; et al. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction and the effect of microencapsulation on mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) rind extract. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, e35521. [CrossRef]

- Saoud, A.A.; Yunus, R.M.; Aziz, R.A.; Rahmat, A.R. Study of eucalyptus essential oil acquired by microwave extraction. Acta. Hortic. 2005, 679, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.I.; Parente, J.F.; Marques, J.F.; et al. Microencapsulation of Essential Oils: A Review. Polym. 2022, 14, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbahani, A. El; Miladi, K.; Badri, W.; et al. Essential oils: From extraction to encapsulation. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 483, 220–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osaili, T.M.; Dhanasekaran, D.K.; Zeb, F.; et al. A Status Review on Health-Promoting Properties and Global Regulation of Essential Oils. Molecules. 2023, 28, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi ME; Chemat, F.; Smadja, J. Solvent-free microwave extraction of essential oil from aromatic herbs: comparison with conventional hydro-distillation. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004, 1043, 323–327. [CrossRef]

- Ferhat. M.A.; Meklati, B.Y.; Smadja, J.; Chemat, F. An improved microwave Clevenger apparatus for distillation of essential oils from orange peel. J Chromatogr A. 2006, 1112, 121–126. [CrossRef]

- Golmakani, M.T.; Rezaei, K. Comparison of microwave-assisted hydrodistillation with the traditional hydrodistillation method in the extractionof essential oils from Thymus vulgaris L. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meireles, M.A.A.; Braga, M.; Leal, P.; et al. Low-Pressure Solvent Extraction (Solid‚ÄìLiquid Extraction, Microwave Assisted, and Ultrasound Assisted) from Condimentary Plants. 2008, 137–218.

- Chan, C.H.; Yusoff, R.; Ngoh, G.C.; Kung, F.W.L. Microwave-assisted extractions of active ingredients from plants. J. Chromatogr 2011, 1218, 6213–6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, M. Study on new extraction technology and chemical composition of litsea cubeba essential oil. Open Mater Sci J. 2011, 5, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filly, A.; Fernandez, X.; Minuti, M.; et al. Solvent-free microwave extraction of essential oil from aromatic herbs: From laboratory to pilot and industrial scale. Food Chem. 2014, 150, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Gaber, A.S.; El Gendy, A.N.G.; Elkhateeb, A.; et al. Microwave extraction of essential oil from Anastatica hierochuntica (L): Comparison with conventional hydro-distillation and steam distillation. J Essent Oil Bear Plants. 2018, 21, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Vega, A.; Ramírez-Corona, N.; López-Malo, A.; Palou, E. Studying microwave assisted extraction of Laurus nobilis essential oil: Static and dynamic modeling. J. Food Eng. 2019, 247, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.; Ngo, T.C.Q.; Dao, T.P.; et al. Optimizatoin of microwave-assisted extraction and compositional determination of essential oil from leaves of Eucalyptus globulus. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, G.; et al. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of anthocyanins in red raspberries and identification of anthocyanins in extract using high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007, 14, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.C.; Macdonell, P.F.; Brophy, J.J.; Davis, R. Eucalyptus bakeri: a potential source species for eucalyptus oil production in the subtropics. Aust. For. 2021, 84, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.N.; Hemant, K.S.Y.; Ram, M.; Shivakumar, H.G. Microencapsulation: A promising technique for controlled drug delivery. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dima, C.; Dima, S. Essential oils in foods: extraction, stabilization, and toxicity. Curr. Opin. Food. Sci. 2015, 5, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. Microencapsulation of vitamin A: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, F.; Santos, L. Encapsulation of cosmetic active ingredients for topical application – a review. J. Microencapsul. 2016, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, I.T.; Estevinho, B.N.; Santos, L. Application of microencapsulated essential oils in cosmetic and personal healthcare products - a review. Int J Cosmet. Sci. 2016, 38, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi-Riseh, R.; Moradi-Pour, M.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Thakur, V.K. Biopolymers for biological control of plant pathogens: Advances in microencapsulation of beneficial microorganisms. Polym. 2021, 13, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, N.; Kumar, P.; Verma, A.K.; et al. Microencapsulation as a noble technique for the application of bioactive compounds in the Food Industry: A Comprehensive Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterenko A, Alric I, Silvestre F, Durrieu V (2013) Vegetable proteins in microencapsulation: A review of recent interventions and their effectiveness. Ind Crops Prod. 2022, 42, 469–479. [CrossRef]

- Paulo, F.; Santos, L. Design of experiments for microencapsulation applications: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2017, 77, 77,1327–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyos-Leyva, J.D.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J.; Garcia, H.S. Microencapsulation using starch as wall material: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2018, 34, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamekhorshid, A.; Sadrameli, S.M.; Farid, M. A review of microencapsulation methods of phase change materials (PCMs) as a thermal energy storage (TES) medium. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2014, 31, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry AM; Abbas S; Ali B; et al. Microencapsulation of Oils: A Comprehensive Review of Benefits, Techniques, and Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15:143–182. [CrossRef]

- Aguiar MCS; das Graças Fernandes da Silva MF; Fernandes JB; Forim M.R. Evaluation of the microencapsulation of orange essential oil in biopolymers by using a spray-drying process. Sci Reports 2020, 101 10:1–11. 1: 10. [CrossRef]

- Pardini FM; Faccia PA; Amalvy JI; et al Microencapsulation of essential oils by single and coaxial electrospraying in poly ε-caprolactone microcapsules: characterization and oil release behavior. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Anjari, H.M.; Sarjono, I.J.; Danarto, Y.C. Studies of encapsulation efficiency and swelling behavior of briboflavin encapsulated by alginate and chitosan. J. Phys. Conference Series Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing. 2344. 2022, 012009. [CrossRef]

- Alavijeh, E.S.; Habibpour, B.; Moharramipour, S.; Arash Rasekh, A. Bioactivity of Eucalyptus camaldulensis essential oil against Microcerotermes diversus (Isoptera: Termitidae). J. Crop Protection. 2014, 3, 1-11.

- Amri, I.; Khammassi, M.; Ben Ayed, R.; Khedhri, S.; Mansour, M.B.; Kochti, O.; Pieracci, Y.; Flamini, G.; Mabrouk, Y.; Gargouri, S.; et al. Essential Oils and Biological Activities of Eucalyptus falcata, E. sideroxylon and E. citriodora Growing in Tunisia. Plants 2023, 12, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danna, C.; Malaspina, P.; Cornara, L.; Smeriglio, L.; Trombetta, D.; De Feo, V.; Stefano Vanin, S. Eucalyptus essential oils in pest control: a review of chemical composition and applications against insects and mites. Crop Protec. J. 2024, 176, 106319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, O.B. da; Del Menezzi, C.H.S.; Benedito, L.E.C.; et al. Essential oil constituents and yields from leaves of Blepharocalyx salicifolius (Kunt) O. Berg and Myracrodruon urundeuva (Allemão) collected during daytime. Int. J. For. Res. 2014, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Alenyorege, E.A.; Hussein, Y.A.; Adongo, T.A. Extraction yield, efficiency and loss of the traditional hot water floatation (HWF) method of oil extraction from the seeds of Allanblackia floribunda. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2015, 4, 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Keneni, Y.G.; Bahiru, L.A.; Marchetti, J.M. Effects of different extraction solvents on oil extracted from jatropha seeds and the potential of seed residues as a heat provider. Bioenergy Res. 2021, 14, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abitogun, A.; Alademeyin, O.J.; Oloye, D. Extraction and characterization of castor seed oil. Internet. J. Nutr. Wellness. 2008, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindi, S.S.; Dawoud, U.M.; Asiry, K.A. Bioplastic floss of a novel microwave-thermospun shellac: Synthesis and bleaching for some dental applications. Polym. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindi, S.S.; Dawoud, U.M.; Ismail, I.M.; et al. A novel microwave hot pressing machine for production of fixed oils from different biopolymeric structured tissues. Polym. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, A. Polymer Technology Dictionary. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, 555 pp.

- Guenther, E. The essential oils (Vol III). Toronto, New York and London: D. Van Nostrand Comp., INC., Toronto, New York and London. 1960.

- Ashraf, M.; Ali, Q.; Anwar, F.; Hussain, A. I. Composition of leaf essential oil of Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Asian J. Chem. 2010, 22, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Paudyal, M.P.; Rajbhandari, M.; Basnet, P.; et al. Quality assessment of the essential oils from Nardostachys jatamansi (d. Don) dc and Nardostachys chinensis batal obtained from Kathmandu valley market. Sci. World 2012, 10:13–16. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D 2395 − 83; Specific gravity of wood and wood–base materials. ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. ASTM D5355-95(2021) - ASTM D5355-95(2021) (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- ASTM D 5768 – 02; Determination of iodine value of tall oil fatty acids. ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022. ASTM D5768-02(2022) - ASTM D5768-02(2022) (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- ASTM D 5558 – 95; Standard test method for determination of the saponification value of fats and oils. ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM D1980 – 87; Standard test method for acid value of fatty acids and polymerized fatty acids. ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998. https://www.scribd.com/document/519054029/ASTM-D1980-acid-value (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Hindi S.S; Dawoud, U. Characterization of hot pressed-fixed oil extracted from Ricinus communis L. Seeds. 2019, 1015680/IJIRSET20190810044 8:10172–10191.

- Thomas, A.; Matthäus, B.; Fiebig H.-J. Fats and fatty oils. Ullmann’s Encycl. Ind. Chem. 2015,1–84. [CrossRef]

- Omari, A.; Mgani, Q.A.; Mubofu, E.B.; et al. Fatty acid profile and physico-chemical parameters of castor oils in Tanzania. Green Sustain. Chem. 2015, 5, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Madden, J.L. Analysis of leaves oils from a Eucalyptus species Trial. Biochem Syst Ecol, 1995, 23, 167-77.

- Silvestre, A. J. D.; Cavaleiro, J. A. S.; Delmond, B.; Filliatre, C. , Bourgeois, G. Analysis of the variation of the essential oil composition of Eucalyptus globulus Labill from Portugal using multivariate statistical analysis. Ind. Crop Prod. 1997, 6, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Study on the chemical constituents of the essential oil of the leaves of Eucalyptus globulus Labill from China. Asian J. Trad. Medicines. 2009, 4, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A.; Sharma, A.; Bachheti, R.; Pandey, D.P. A Comparative study of the chemical composition of the essential oil from Eucalyptus globulus growing in Dehradun (India) and around the world. Oriental J. Chem. 2016, 32, 331-340. [CrossRef]

- Silva RAC da, Lemos TLG de, Ferreira DA, Monte FJQ (2018) Chemical Study of the Seeds of Ximenia americana: Analysis of Methyl Esters by Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Pharm. Res. 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.A.; Suryandari, A.S.; Naryono, E.; Pratiwi, V.M.; Suharto, M.; Adiba, N. Encapsulation of clove oil within ca-alginate-gelatine complex: Effect of process variables on encapsulation efficiency. J. Teknik Kimia dan Lingkungan. 2021, 5, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindi, S.S.; Bakhashwain, A.A.; El-Feel, A. (2010) Physico-chemical characterization of some Saudi lignocellulosic natural resources and their suitability for fiber production. JKAU Met., Env. Arid L. Agric. Sci. 2010, 21, 45–55. [CrossRef]

- Immaroh NZ; Kuliahsari DE; Nugraheni SD. Review: Eucalyptus globulus essential oil extraction method. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021, 733; 12103. [CrossRef]

- Emara, K.S.; Shalaby, A.E. Seasonal variation of fixed and volatile oil percentage of four Eucalyptus spp. related to lamina anatomy. African J Plant Sci 2011, 5, 353–359. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, S.M.; Abe, S.Y.; Murakami, F.S.; et al. Essential oils from different plant parts of Eucalyptus cinerea F. Muell. ex Benth. (Myrtaceae) as a source of 1,8-cineole and their bioactivities. Pharm 2011, 4, 1535-1550. [CrossRef]

- Naafi Achmad H; Rana HE; Fadilla I, et al. Determination of yield, productivity and chemical composition of Eucalyptus oil from different species and locations in Indonesia. Chem. Nat. Resour. Eng. J. 2018, 1, 36–49.

- Abed, K.M.; Naife, T.M. Extraction of essential oil from Iraqi Eucalyptus camadulensis leaves by water distillation methods. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainez-Cerón, E.; López-Malo, A.; Palou, E.; Ramírez-Corona, N. Dynamic performance of optimized microwave assisted extraction to obtain Eucalyptus essential oil: Energy requirements and environmental impact. Int J Food Eng. 2022, 18, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfud, M.; Masum, Z.; Bhuana, D.S.; et al. A comparison of essential oil extraction from the leaves of lemongrass (Cymbopogon nardus L.) using two microwave-assisted methods. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2022, 20, 881–888. [CrossRef]

- Iswahyono; Saleh, A.S.; Djamila, S.; et al. The design and build of ohmic heated hydro distillation for the essential oil extraction of eucalyptus leaves. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 672, 012017. [CrossRef]

- Javed S; Bibi A; Shoaib A; et al. Essential oil of Eucalyptus citriodora: Physio-chemical analysis, formulation with hand sanitizer gel and antibacterial activity. Adv. Life Sci. 2022, 9, 510–515.

- Abdul-Majeed, B.A.; Hassan, A.A.; Kurji, B.M. Extraction of oil from Eucalyptus camaldulensis using water distillation method. Iraqi J. Chem. Pet. Eng. 2013, 14, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus O, Özcanlı S 1-M, Serin -Hasan, et al. Biodiesel production from Ricinus communis oil and its blends with soybean biodiesel. Strojniški vestnik-J. Mech. Eng. 2010, 56, 811–816.

- Uzoh, C.F.; Nwabanne, J.T.; Uzoh, C.F.; Nwabanne, J.T. Investigating the effect of catalyst type and concentration on the functional group conversion in castor seed oil alkyd resin production. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2016, 6, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzenda E, Kabuba J, Mdletye P, Belaid M Optimization of process parameters for castor oil production. In: In Lecture Notes in Engineering and Computer Science. Newswood Limited. 2012, 1586–1589.

- Odoom W, Edusei VO Evaluation of saponification value, Iodine value and insoluble impurities in coconut oils from Jomoro District of the Western Region of Ghana. Asian J. Agric. Food Sci. 2015, 3, 2321–1571.

- Goldbeck, J.C.; do Nascimento, J.E.; Jacob, R.G.; et al. Bioactivity of essential oils from Eucalyptus globulus and Eucalyptus urograndis against planktonic cells and biofilms of Streptococcus mutans. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 60, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viturro, C.I.; Molina, A.C.; Heit CI. Volatile components of Eucalyptus globulus Labill from Jujuy, Argentina. J Essent Oil Res 2003, 15:206–208. [CrossRef]

- Sebei K, Sakouhi F, Herchi W, et al (2015) Chemical composition and antibacterial activities of seven Eucalyptus species essential oils leaves. Biol Res 2015, 48, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Boukhatem, M.N.; Ferhat, M.A.; Kameli, A.; et al. Quality Assessment of the Essential Oil from Eucalyptus globulus Labill of Blida (Algeria) Origin. Int. Lett. Chem. Phys. Astron. 2014, 36, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainez-Cerón, E.; Jiménez-Munguía, M.T.; López-Malo, A.; Ramírez-Corona, N. Effect of process variables on heating profiles and extraction mechanisms during hydrodistillation of eucalyptus essential oil. Heliyon. 2021, 7, e08234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiri, D.; Kretsi, O.; Chinou, I.B.; Spyropoulos, C.G. Composition of fruit volatiles and annual changes in the volatiles of leaves of Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehn. growing in Greece. Flavour Fragr. J. 2003, 18:244–24. [CrossRef]

- Cimanga, K.; Kambu, K.; Tona L.; et al. Correlation between chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oils of some aromatic medicinal plants growing in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 79:213–22. [CrossRef]

- Batista-Pereira, L.G.; Fernandes, J.B.; Corrêa, A.G.; et al. Electrophysiological responses of Eucalyptus Brown Looper Thyrinteina arnobia to essential oils of seven Eucalyptus species. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2006, 17, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppen, J.J.W. Eucalyptus: The genus Eucalyptus, 1st ed. CRC Press, London. 2002.

- Elaissi A; Rouis Z; Mabrouk S; et al. Correlation between chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oils from fifteen Eucalyptus species growing in the Korbous and Jbel Abderrahman arboreta (Northeast Tunisia). Molecules, 3044. [CrossRef]

- Sahi NM (2016) Evaluation of insecticidal activity of bioactive compounds from eucalyptus citriodora against Tribolium castaneum. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res 2016, 8, 8,1256–1270.

- Darshan, S.; Doreswamy, R. Patented antiinflammatory plant drug development from traditional medicine. Phytother Res 2004, 18:343–357. [CrossRef]

- Vaičiulytė, V.; Ložienė, K.; Švedienė, J.; et al. α-Terpinyl acetate: Occurrence in essential oils bearing thymus pulegioides, phytotoxicity, and Antimicrobial Effects. Molecules 2021, 26, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, R.S.; Hewedi, F.M.; Abu-Raiia, S.H.; El-Baroty, G.S. Comparative study on the deterioration of oils by microwave and conventional heating. J Food Prot 1992, 55:722–727. [CrossRef]

- Takagi, S.; Ienaga H; Tsuchiya C. Yoshida H. Microwave roasting effects on the composition of tocopherols and acyl lipids within each structural part and section of a soya bean. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1999, 79, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, S.; Yoshida, H. Microwave heating influences on fatty acid distributions of triacylglycerols and phospholipids in hypocotyl of soybeans (glycine max L.). Food Chem, 1999, 66, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uquiche, E.; Jeréz, M.; Ortíz, J. Effect of pretreatment with microwaves on mechanical extraction yield and quality of vegetable oil from Chilean hazelnuts (Gevuina avellana Mol). Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 2008, 9, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh V, Seo Y, Datta AK, et al (2010) Heat transfer during microwave combination heating: Computational modeling and MRI experiments. AIChE J. 2010, 56, 2468–2478. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Karakawa, M.; Hashimoto, O. Temperature of a heated material in a microwave oven considering change of complex relative permittivity. The 39th Eur Microw Conf EuMC. 2009, 798–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Flores MJ; Chanona-Pérez JJ; Garibay-Febles V; et al. Microscopy techniques and image analysis for evaluation of some chemical and physical properties and morphological features for seeds of the castor oil plant (Ricinus communis). Ind. Crops Prod, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Azadmard-Damirchi S; Alirezalu K; Achachlouei BF. Microwave pretreatment of seeds to extract high quality vegetable oil. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Biol. Biomol. Agric. Food Biotechnol. Eng. 2011.

- Anonymous. PubChem, National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem (nih.gov). 2021. Available online: a) https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Guar-Gum, b) https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/substance/135336954, c) https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Sodium-Borate, and d) https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Calcium-Chloride. (accessed on 22 February 2025).

| Parameter | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GC | Column dimension | Length | 30 m |

| Internal diameters | 0.25 mm | ||

| Solvent’s thickness film | 0.25 μm | ||

| Column temperature | Initial temperature (IT) | 40 oC | |

| Residence time (RT) of the IT | 4 min | ||

| Maximum final temperature (MFT) | 220 oC | ||

| RT of the MFT | 15 min | ||

| Heating rate | 4 oC/min | ||

| Injector temperature | 250oC | ||

| Injection volume | 1 μl | ||

| Flow rate of the carrier gas (helium) | 20 ml/min | ||

| Transfer temperature | 280 oC | ||

| MS | Electron ionization (EI) mode | Negative chemical ionization | |

| Ionization voltage | 70 eV | ||

| Ion source temperature | 180oC | ||

| Scanning range | 50-600 Da | ||

| Chemical compound |

Extraction Methods | Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MASD | MASD | ||||||

| Hada Al-Sham |

Briman | KAU | Hada Al-Sham |

Briman | KAU | ||

| 1-8 Cineol | 76.15 ±0.885 |

67.12 ±0.834 |

56.19 ±1.700 |

72.15 ±0.885 |

63.12 ±0.834 |

55.85 ±1.032 |

72.26 ±1.88 |

| α-Terpinene | 6.42 ±0.431 |

3.61 ±0.291 |

2.63 ±0.200 |

5.59 ±0.431 |

2.78 ±0.291 |

1.80 ±0.200 |

2.61 ±0.114 |

| 3-Carene | 4.51 ±0.118 |

1.61 ±0.073 |

0.59 ±0.050 |

4.14 ±0.118 |

1.24 ±0.073 |

0.22 ±0.050 |

3.28 ±0.024 |

| D-Limonene | 3.60 ±0.176 |

2.34 ±0.097 |

1.65 ±0.093 |

3.18 ±0.176 |

1.92 ±0.097 |

1.23 ±0.093 |

1.78 ±0.019 |

| L-trans-Pinocarveol | 3.66 ±0.031 |

3.23 ±0.068 |

2.94 ±0.042 |

3.32 ±0.031 |

2.89 ±0.068 |

2.60 ±0.042 |

2.69 ±0.865 |

| α-Pinene | 1.69 ±0.043 |

1.18 ±0.040 |

0.73 ±0.026 |

1.45 ±0.043 |

0.94 ±0.040 |

0.49 ±0.026 |

9.89 ±0.172 |

| α-Myrcene | 3.18 ±0.057 |

1.41 ±0.132 |

0.65 ±0.051 |

2.91 ±0.057 |

1.14 ±0.132 |

0.38 ±0.051 |

0.36 ±0.035 |

| LSD0.05 | 1.155 | 0.417 | 1.097 | 2.356 | 0.947 | 1.249 | 1.291 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).