1. Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.) is widely regarded as one of the most significant food crops globally, with its yield and quality directly affecting food security and economic development [

1,

2]. However, maize is vulnerable to various diseases and pests throughout its growth, such as maize rust and leaf spot, severely affecting its yield and quality [

3]. Therefore, accurate disease identification is critical for disease control and yield assurance in maize cultivation [

4]. Since disease symptoms predominantly appear on the leaves, leaf images become a vital basis for disease identification [

5]. Traditional methods to detect pests and diseases in maize leaves rely on manual observation. This method is inefficient, burdensome, subjective, and cannot meet the demands of modern agriculture for refined and large-scale production [

6]. Therefore, there is a critical need to explore efficient and accurate methodologies for the detection of maize pests and diseases. This endeavor is vital to address the limitations associated with traditional techniques and to facilitate rapid and precise assessments of pest infestations and disease occurrences [

7].

With the recent rapid advancements in computer vision technology, machine learning and deep learning techniques have found extensive application across various domains. They are particularly effective in agricultural monitoring, especially concerning the detection of pests and diseases [

8,

9]. For example, Panigrahi et al. [

10] compared the accuracy of five standard machine learning techniques. The methodologies examined included NB, DT, KNN, SVM, and the frequently implemented RF for the detection of pests and diseases affecting maize crops. They found that the RF method achieved a high accuracy of 79.23%. Paul et al. [

11] developed a mobile application based on the pre-trained VGG16 architecture using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), facilitating the efficient identification and classification of maize leaf diseases.

The YOLO series has emerged as a pivotal method among numerous detection algorithms, attributable to its outstanding real-time performance and high level of detection accuracy [

12,

13]. From YOLOv1 to the latest YOLOv11, the YOLO family has been continuously optimized for detection accuracy, speed, and model complexity, providing robust technical support for agricultural detection, especially intelligent pest and disease detection [

14,

15,

16,

17]. For instance, Fan et al. [

18] combined YOLOv5 with dark channel enhancement for strawberry ripeness recognition and achieved a test accuracy exceeding 90%. Wang et al. [

19] introduced a detection method for wheat seedlings, which improved YOLOv5 by replacing global annotation with local annotation, adding a micro-scale detection layer, and a spatial depth convolution module. These modifications significantly enhanced the extraction capability of small features and increased detection accuracy to 90.1%. Li et al. [

20] proposed YOLO-Leaf for apple leaf disease detection that utilized DSConv to achieve robust feature extraction, BiFormer for enhanced attention mechanisms, and IF-CIoU to optimize bounding box regression. YOLO-Leaf outperformed existing models in detection accuracy. Besides, Lu et al. [

21] developed the cotton boll detection model COTTON-YOLO that improved YOLOv8n by introducing the C2F-CBAM module. The Gold-YOLO neck architecture designed for enhanced information flow and enhanced feature integration. Yang et al. [

22] identified maize leaf spots by introducing the Slim-neck and GAM attention in YOLOv8. This setup significantly improved the model’s recognition ability for maize leaf spots, demonstrating a 3.79% improvement in accuracy (P) and 4.65% in recall (R) compared to the original YOLOv8 model.

However, existing methods for detecting pests and diseases in maize leaves still face limitations when dealing with complex agricultural scenarios, with occlusion and overlapping of maize leaves leading to missed and false detections [

23]. Additionally, the detection performance of the models significantly declines under varying lighting conditions [

24]. Therefore, it is evident that the classification accuracy of existing methods for different types of pests and diseases with similar morphology must be improved [

25]. Additionally, the YOLO series algorithms have a complex multi-branch structure in the backbone that limits the disease detection speed, underperforms when processing small and dense targets in complex environments, the method heavily depends on the detection head based on predefined anchor boxes, which leads to slower inference speeds [

26]. Additionally, the rigidity of the sample allocation strategies reduces the efficient utilization of features during the training process..

Motivated by the concerns outlined above, this study proposes a high-performance and lightweight model for detecting maize leaf diseases, named YOLOv11s-RCDWD (YOLOv11s-RepLKNet-CBAM-DynamicHead-WIoU-DynamicATSS). The proposed model is built upon the latest YOLO series object detection algorithm, YOLOv11s, with the aim of accurately and efficiently locating and detecting maize leaf diseases in natural scenes with complex backgrounds. Furthermore, it provides technical support for deploying the model on agricultural mobile devices.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

In the backbone layer, we replace the C3k2 backbone network with the RepLKNet network, improving detection performance and efficiency through re-parameterization.

Introducing the CBAM (Selective Kernel Attention, CBAM) attention module to enhance the model’s ability to capture multi-scale features. CBAM allows the model to focus on key features of diseased maize leaves, thereby improving feature extraction capability.

Adopting the DynamicHead detection head to unify the scale-aware, space-aware, and task-aware aspects of object detection by integrating multiple attention mechanisms. This strategy significantly improves the representation ability of the detection head without increasing computational overhead.

Optimizing the loss function using the symmetric IoU loss function WIoU to improve the bounding box regression accuracy and enhance the model’s localization capability.

Replacing the original fixed-ratio positive and negative sample allocation strategy with DynamicATSS to adjust the selection mechanism of positive and negative samples based on statistical information during training. DynamicATSS improves the model’s generalization ability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production of Datasets

This study constructs a sample dataset covering multiple scenarios and various typical corn disease types based on an open-source dataset (released by Plant Village [

27]) and a self-built dataset (from local corn planting bases in Yangling, Shaanxi) to comprehensively evaluate the performance of YOLOv11s-RCDWD in detecting corn leaf diseases.

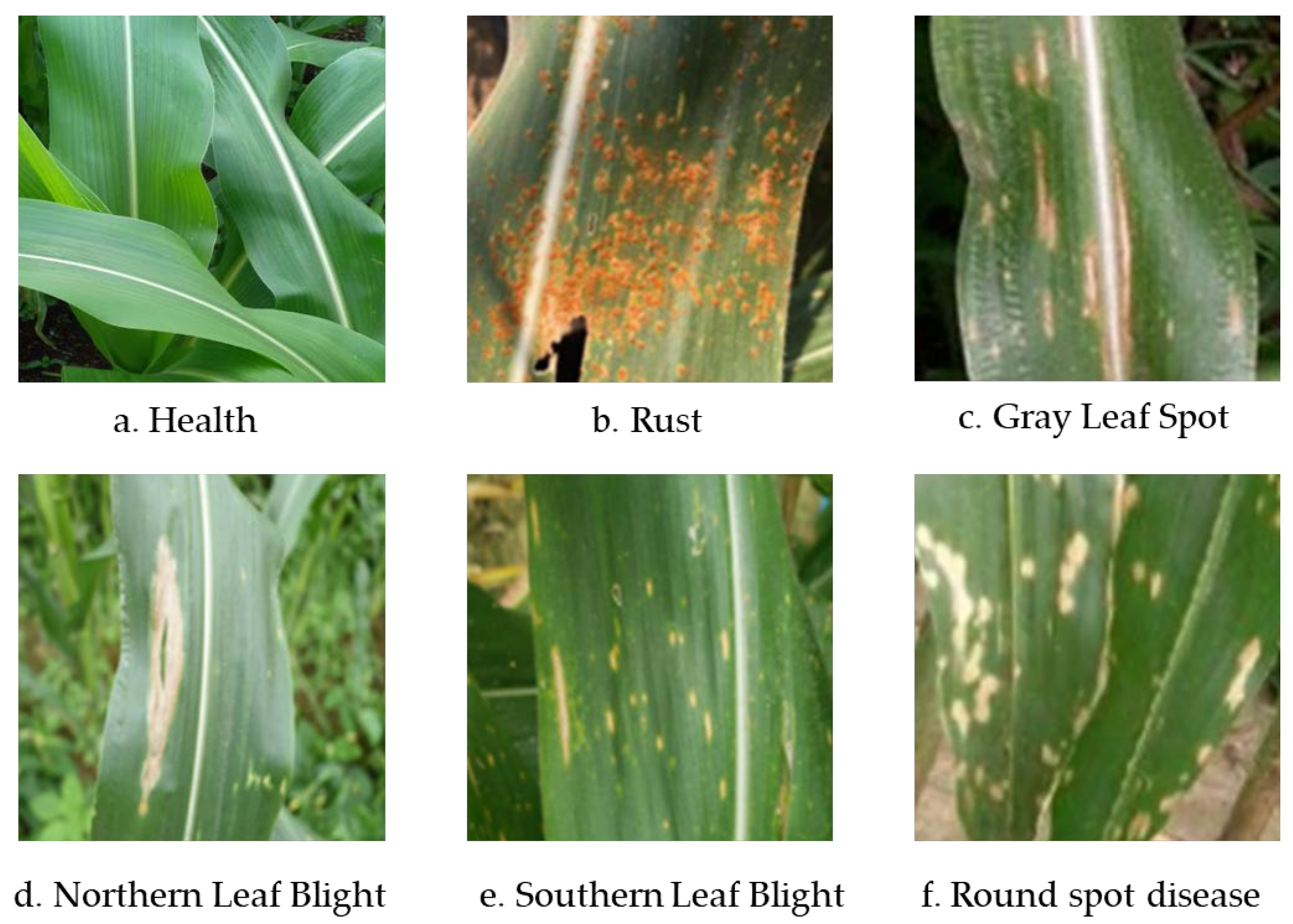

The

LabelImg annotation software is used to annotate the collected sample images accurately [

28]. Specifically, the disease-affected areas in the images are completely enclosed using the maximum horizontal rectangular bounding boxes, and the annotations are stored in VOC-format XML files. Each annotated image undergoes data augmentation, where first, the image resolution in the training set is uniformly adjusted to 640×640 pixels to generate clear and standardized image samples. Then, randomly flipping the images vertically and horizontally increases sample diversity. Finally, the images are normalized based on their mean and standard deviation to eliminate lighting and contrast differences. The VOC-format XML annotation files are then converted into YOLO-format TXT files, serving as input data for model training. These operations effectively simulate the growth posture, lighting conditions, and shooting angle variations of corn in real-world scenarios, enhancing the diversity of training samples. A total of 7,928 labeled corn disease images were successfully constructed, including 1,510 Rust images, 1,275 Gray Leaf Spot images, 1,305 Northern Leaf Blight images, 1,163 Southern Leaf Blight images, 1,260 Round Spot Disease images, and 1,415 healthy corn leaf images (

Figure 1). These images exhibit significant differences in morphology, texture, and color, providing rich feature information for disease identification. The augmented images are randomly divided into training, testing, and validation sets based on a 7:2:1 ratio (5549, 1586, and 793, respectively) for subsequent model training and testing.

2.2. Model Improvement

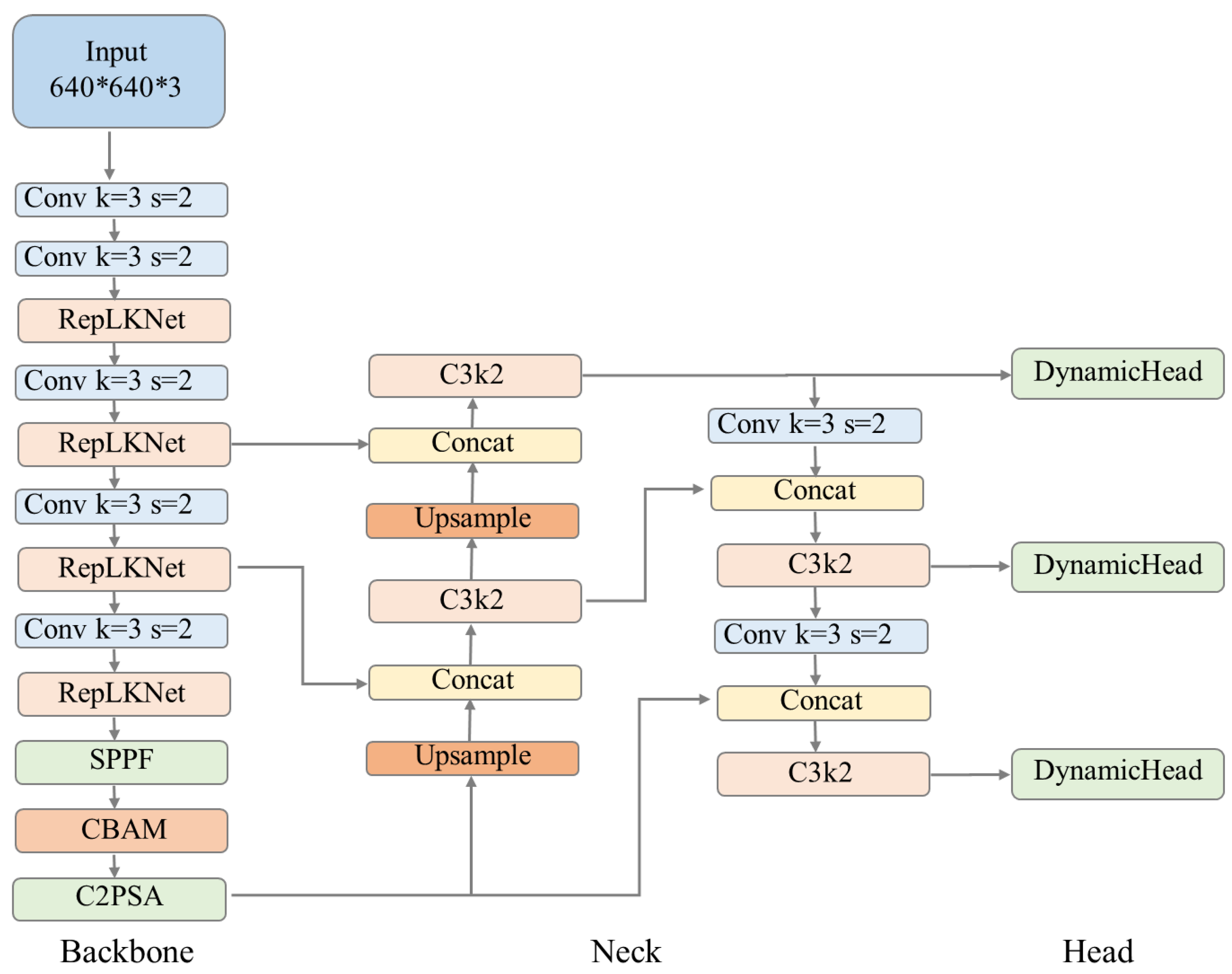

2.2.1. Improved YOLOv11 Network Model Construction

YOLOv11 is the latest YOLO version, inheriting and refining the core concepts and technical frameworks of its predecessors to enhance detection speed, accuracy, and robustness [

29]. Significant improvements have been made in its backbone network and neck layers. Addressing the challenges of large model parameters, hefty weight files, and low detection accuracy in current complex maize leaf disease detection scenarios, this study enhances the YOLOv11s model.

Specifically, the backbone network uses RepLKNet as the feature extraction network. RepLKNet utilizes advanced convolution operations and re-parameterization techniques to significantly reduce computational load while maintaining feature extraction capabilities, thereby enhancing the model’s lightweight characteristics. In addition to its foundational architecture, RepLKNet incorporates the Partial Spatial Attention (PSA) module, which directs the model’s focus toward critical feature regions. Furthermore, the neck network integrates the CBAM, an attention mechanism that enhances the model’s ability to capture multi-scale features by combining both channel and spatial attention strategies. This dual approach allows for a concentrated emphasis on key features related to pests and diseases. Moreover, the neck network aggregates features of different scales through the ELAN-W module, which employs the SPPCSPC module for spatial pyramid pooling, further improving the handling of multi-scale features. The detection head incorporates the DynamicHead module, which integrates various attention mechanisms to unify scale, spatial, and task awareness in object detection, significantly boosting the representational capacity of the detection head without additional computational overhead. The proposed Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion (ASFF) module adaptively fuses shallow and deep features to enhance feature scale invariance, accurately detecting large, medium, and small targets. The accuracy of bounding box regression is improved by optimizing the loss function through the Symmetric IoU Loss Function (WIoU). WIoU optimizes the precision of bounding box localization, thereby enhancing the model’s overall detection performance. Lastly, the dynamic adjustment mechanism (DynamicATSS) dynamically selects positive and negative samples based on statistical information during training, replacing the traditional fixed ratio allocation strategy and significantly improving the model’s generalization capabilities.

Figure 2 presents improved YOLOv11s-RCDWD model. Through the optimizations presented above, our model excels in maize leaf disease and pest detection, achieving high precision and performance in locating and identifying diseases and pests while maintaining excellent lightweight characteristics suitable for deployment on agricultural mobile devices.

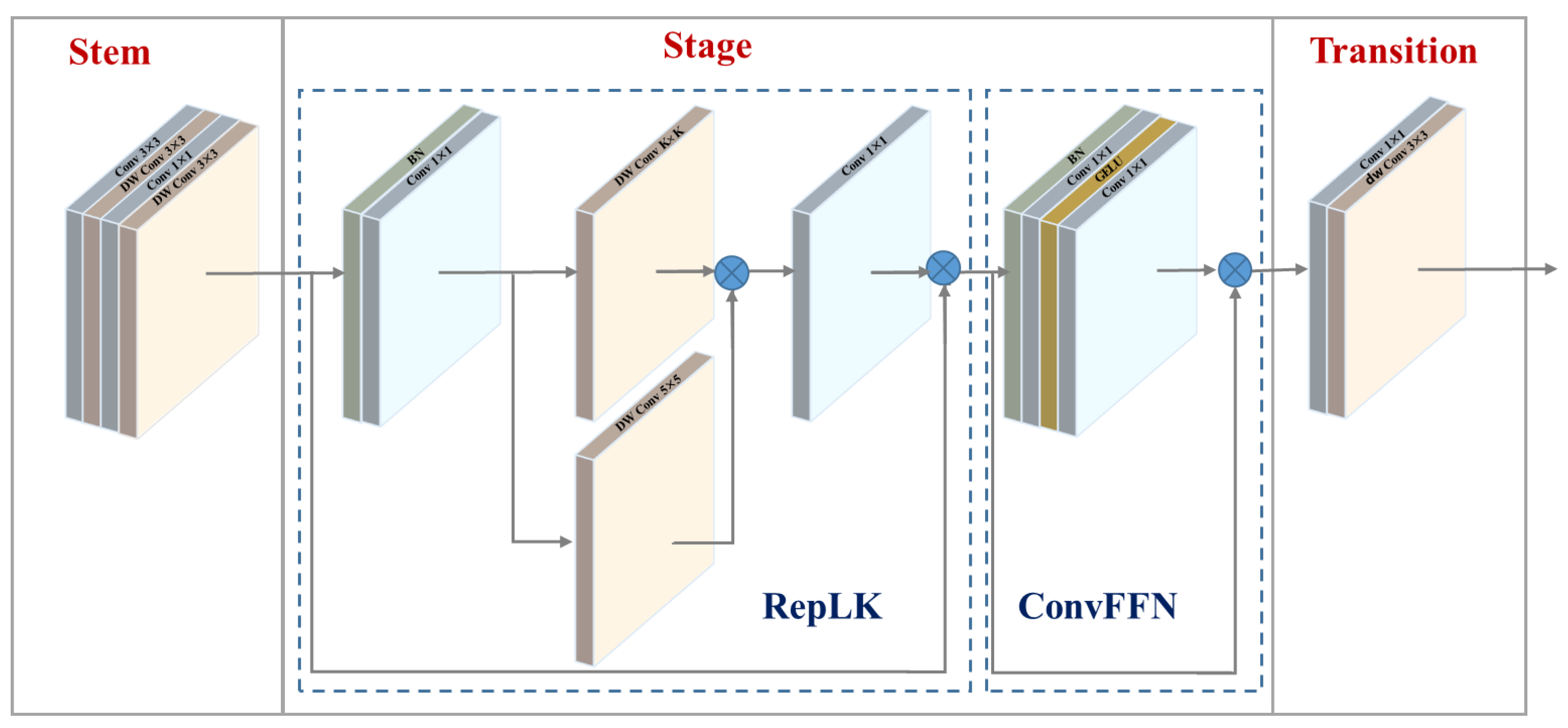

2.2.2. RepLKNet

In complex scenarios characterized by interference and overlapping foliage, the textural features of diseased areas on maize leaves exhibit a high degree of complexity, posing significant challenges to accurately detecting these diseased regions. Therefore, this study introduces RepLKNet as the backbone network to enhance the model’s precision in detecting maize diseases amidst overlapping and occluded backgrounds [

30]. RepLKNet significantly improves feature extraction performance by expanding the Effective Receptive Field (ERF) and enhancing the capability to extract shape information. The ERF, based on a quantitative metric proposed by Luo et al. [

31], characterizes the contribution of each input pixel within the receptive field to the output of the n-th layer unit in the network.

Figure 3 depicts RepLKNet, which primarily comprises three core modules: Stem, Stage, and Transition. The first is responsible for initial feature extraction, the second achieves multi-level feature learning by cascading multiple large kernel convolution sub-modules, and the third down-samples feature maps and adjusts the number of channels. Using RepLKNet with a larger effective receptive field allows the model to effectively extract global contextual information and local detail features from input images, demonstrating significant advantages, particularly in complex scenes of maize leaf diseases with shadow interference and overlapping foliage.

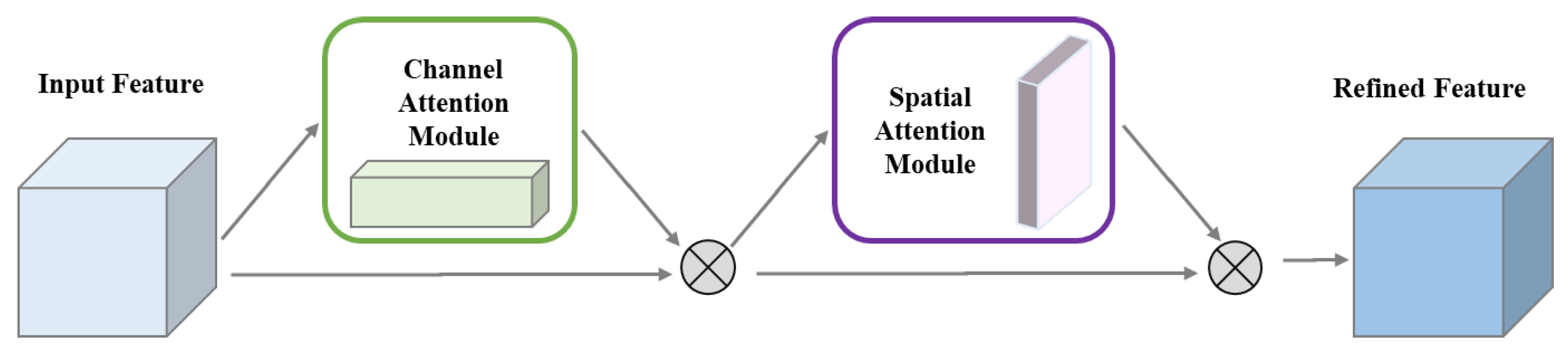

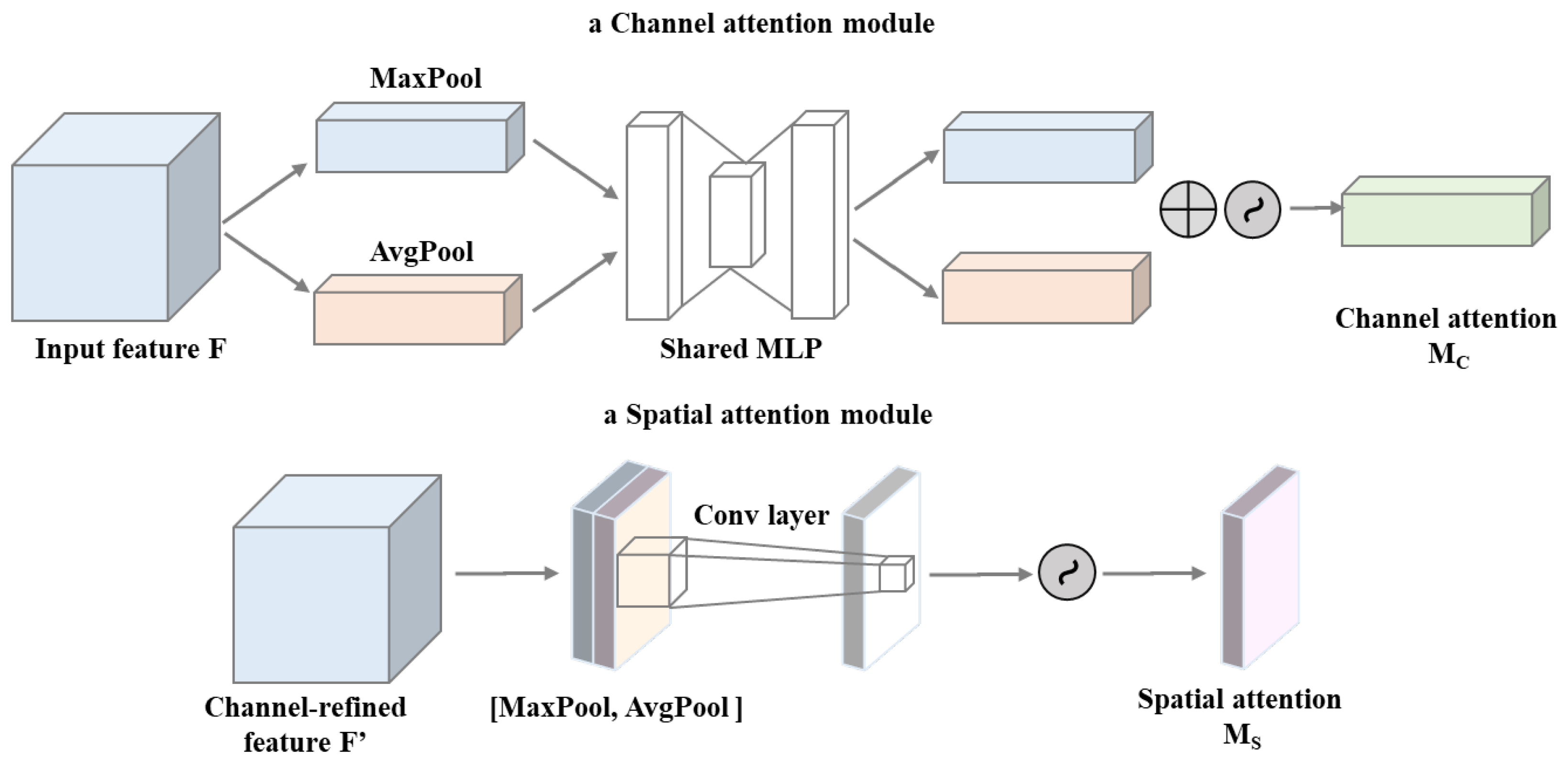

2.2.3. CBAM Attention

This study introduces CBAM to improve the model’s feature representation capability. This module integrates both channel and spatial attention mechanisms, providing the model with comprehensive and effective feature extraction capabilities [

32].

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 depict the core idea of CBAM, which aims to refine the input feature map in two stages: first, by refining the dependencies among channels using the Channel Attention Module (CAM), and then by enhancing features along the spatial dimension using the Spatial Attention Module (SAM).

CAM assesses the significance of each channel, thereby weighting the channel dimension of the feature map to highlight the contributions of key feature channels. It uses global max pooling and global average pooling to capture local details and global information from the feature map, respectively. The output of CAM is articulated as follows:

where A and M stand for the global average pooling and max pooling procedures, respectively, and

F is the input feature map. Additionally, the Multi-Layer Perceptron is represented by M, and the Sigmoid activation function is represented by

σ.

SAM further optimizes the spatial dimension of the feature map by generating a spatial attention map along the channel dimension using pooling operations. The significance of various geographical places in the feature map is reflected in this map. The model adaptively improves the feature responses of significant regions while reducing noisy or irrelevant parts by multiplying the spatial attention map by the feature map. The output of SAM is articulated as follows:

where [AvgPool(

F);MaxPool(

F)] is the concatenation of the average pooling as well as max pooling results along the channel ax-is, and

f7×7 indicates a 7×7 convolution operation. This two-stage attention mechanism allows CBAM to effectively capture essential information in the feature map’s channel and spatial dimensions, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to perceive key features.

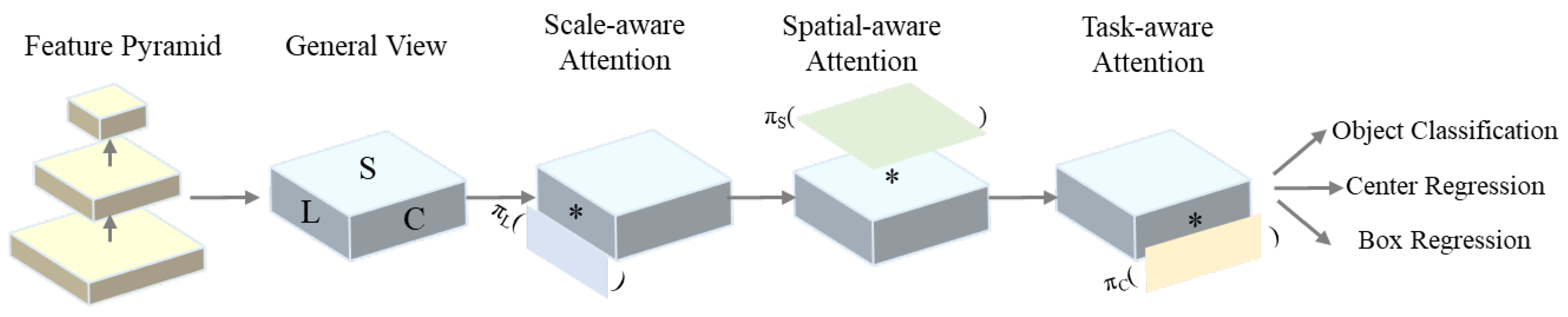

2.2.4. DynamicHead

This study introduces a dynamic detection head to integrate multi-dimensional attention into the original YOLOv11 detection head. The Dynamic Head aims to unify scale, spatial, and task awareness in object detection by incorporating various attention mechanisms, thus considerably improving the representational capacity of the detection head while maintaining computational efficiency [

33].

Figure 6 highlights that the Dynamic Head architecture comprises three attention mechanisms. A 3D tensor is created by first extracting feature pyramids using different backbone networks, scaling them to the same scale, and then feeding it into the Dynamic Head. Then, many DyHead blocks with task-aware, scale-aware, and spatial-aware attention mechanisms are placed one after the other.

Scale-aware attention, one of these processes, is used at the feature level dimension by dynamically combining information based on the semantic significance of various scales. This improves the detection head’s capacity to handle items of different sizes in the picture by increasing the sensitivity of the feature map to scale fluctuations of foreground objects. The spatial dimension (height x breadth) is where spatially aware attention is applied. In order to concentrate on discriminative areas that are consistently present across spatial locations and feature levels, it first uses deformable convolution to sparsify attention learning before aggregating cross-level data at the same spatial location. The feature map becomes sparser and more focused on the discriminative spatial locations of foreground objects as a result of this technique’ adaptive aggregation of several feature levels.

These attention mechanisms operate in different dimensions, complementing each other and collectively enhancing the representational capability of the object detection head. Integrating them into a unified framework allows the Dynamic Head to effectively address challenges related to scale and space in object detection tasks, thereby improving detection performance.

2.2.5. Wise-IoU

This approach may result in a distorted evaluation of the outcomes [

34]. On the other hand, weighted Intersection over Union (WIoU) mitigates this issue by incorporating the areas between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes into the IoU computation, thus reducing potential biases present in conventional IoU assessments [

35]. To calculate the IoU score between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, the spatial interaction between them is examined. More specifically, the distance between the centers of the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes is measured and used as a benchmark for the maximum feasible distance between the two. Based on the regions between the two boxes, a weighting coefficient is calculated, which measures the relationship between the two boxes and can be used to weight the IoU score. By introducing the regions between the boxes and the weighting coefficient, WIoU can more accurately evaluate object detection results, avoiding biases inherent in traditional IoU.

Where LCloU is an enhanced Intersection over Union (IoU) loss function that accounts for the impact of both the distance between bounding box centers and their aspect ratios. LWIoU represents a weighted IoU loss function, which modifies the traditional IoU loss by employing a weighting coefficient r alongside the region weight RWIoU. Additionally, parameters α and ν serve to balance considerations related to center distances and aspect ratios.

The RWIoU is the region weight based on the distance between the centers of the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, and β is a dynamically adjusted weighting coefficient that balances the IoU loss across different samples. By introducing region weights and a dynamic adjustment mechanism, WIoU can precisely evaluate object detection results, enhancing the model’s detection performance.

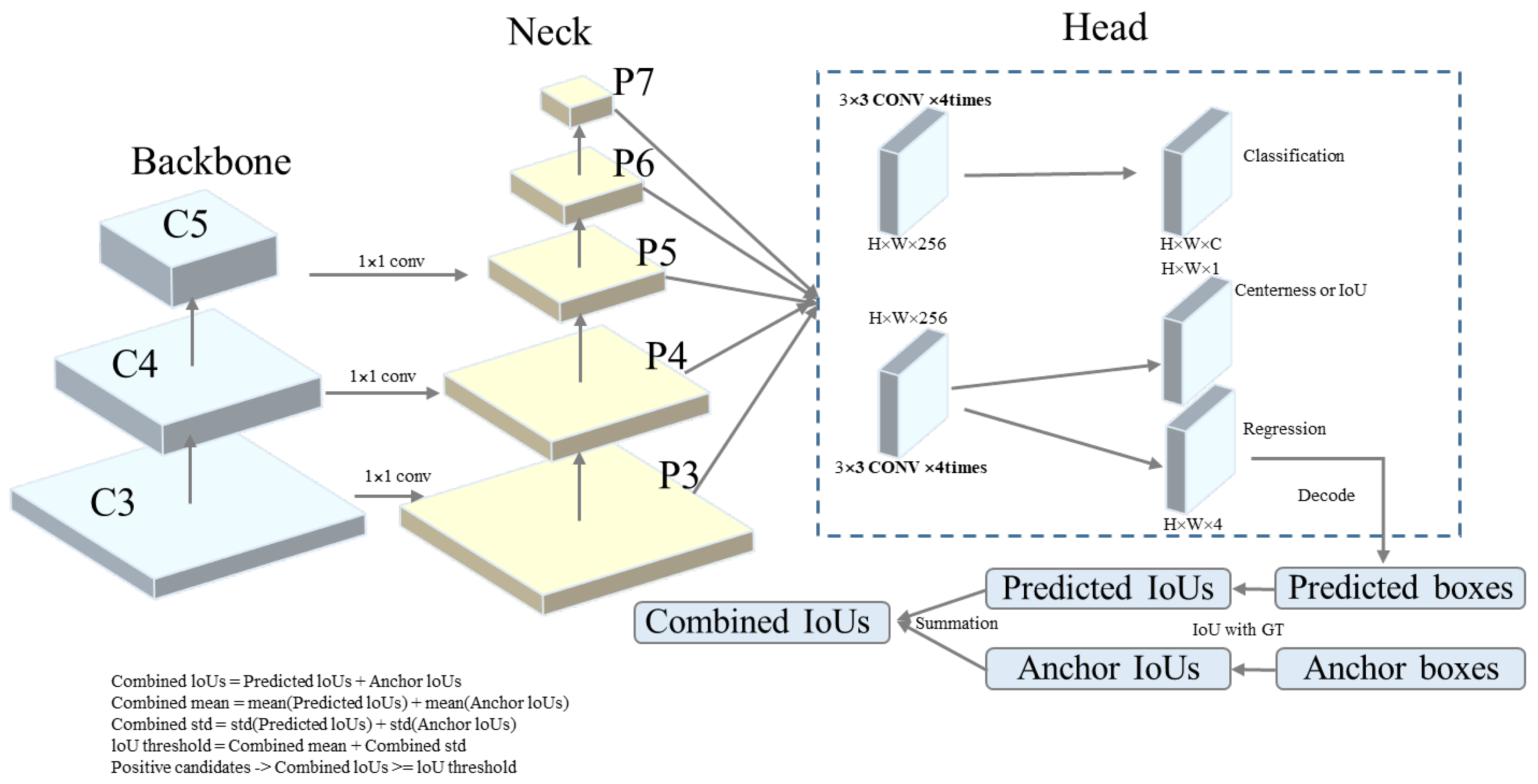

2.2.6. DynamicATSS

Label assignment is crucial in modern object detection models, as different label assignment strategies affect performance outcomes [

36].

This paper employs a straightforward yet highly effective dynamic label assignment strategy called Dynamic ATSS, which incorporates predictions into the label assignment process for anchors (

Figure 7) [

37]. In the initial stages of training, predictions tend to be inaccurate owing to random initialization. Therefore, anchors are defined by label indications as before. However, as training progresses and predictions improve, the predictions progressively take precedence over the combined Intersection over Union (IoU), leading to more refined label assignments. This strategy performs dynamic label assignment is determined by the training state and the corresponding predictions.

2.3. Model Training and Evaluation Metrics

2.3.1. Maize Leaf Algorithm Model Training Environment

The experimental setup comprises a 64-bit Ubuntu Server 22.04 LTS operating system, utilizing an NVIDIA RTX 4090D GPU with 24 GB of video memory and 80 GB of host memory. The programming language was Python 3.10, with GPU acceleration enabled using CUDA v11.8. The training was performed using the deep learning framework PyTorch 2.1.2.

Table 1 reports the training parameter settings.

2.3.2. Evaluation Metrics

We divided the maize leaf dataset into a training set, validation set, and test set in an 8:1:1 ratio to facilitate model training, optimization, and evaluation for subsequent research. The evaluation metrics employed in this study for the maize leaf disease detection model include Precision, Recall, F1 Score, mean Average Precision (mAP), Detection Speed, Model Parameters, Computational Load (GFLOPs), and Memory Cost. A higher Precision indicates more reliable positive predictions by the model. Precision, Recall, F1 Score, and mAP are formulated as follows:

The model’s real-time performance is assessed based on Detection Speed, Model Parameters, Computational Load (GFLOPs), and Memory Cost. Detection Speed refers to the time required for the model to process an image, measured in seconds (s) or milliseconds (ms). Faster detection speeds indicate better real-time performance in practical applications. Model Parameters are the model’s total number of trainable parameters, measured in millions (M). Fewer parameters generally indicate a more lightweight model that is easier to deploy on resource-constrained devices. GFLOPs refer to the number of floating-point operations required during the model’s forward propagation, measured in billions of floating-point operations (Giga FLOPs). Lower computational load indicates lower hardware resource requirements and faster runtime speeds. Memory Cost is the memory required for the model to run, measured in megabytes (MB). Lower memory cost indicates that the model is more suitable for running on memory-constrained devices.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Experiments of Different Backbone Networks

This study was designed to conduct a series of comparative experiments aimed at comprehensively examining the profound impact of diverse factors backbone networks on the performance of the YOLOv11 model in the detection tasks related to maize leaf diseases.The experiments evaluated five mainstream lightweight backbone network models, including CFNet, FasterNet, GhostNetV2, MobileViTBv3, and RepLKNet, where each was integrated into the YOLOv11 model architecture. These models were then evaluated against YOLOv11’s native backbone network, C2K3. Tale 2 reports the corresponding experimental results.

Table 2 highlights significant performance variations in maize disease detection tasks depending on the backbone network. For instance, the YOLOv11 model with RepLKNet as the backbone (YOLOv11s-RepLKNet) demonstrates notable comprehensive advantages in four key aspects: detection accuracy, detection speed, model complexity, and resource usage, particularly excelling in detection accuracy. RepLKNet achieves the highest values in both Precision and F1 Score, reaching 89.1% and 84.2%, respectively. This indicates that RepLKNet has a significant advantage in detection accuracy, effectively reducing false positives and missed detections. Additionally, its Recall reaches 79.9%, demonstrating its substantial detection completeness and robustness performance. Although its mAP@0.5~0.95 is slightly lower than some models, its average precision at different confidence thresholds (mAP@0.5) remains high (87.1%), proving its detection capability under multi-threshold conditions.

The detection speed of YOLOv11s-RepLKNet is 3.2 ms per image, comparable to YOLOv11s-CFNet and significantly better than YOLOv11s-MobileViTBv3 (4.4 ms per image). This demonstrates that RepLKNet can achieve fast detection speeds while maintaining high accuracy, rendering it appropriate for real-time detection of maize diseases in practical applications.

From the perspective of model complexity and resource usage, although YOLOv11s-RepLKNet has a slightly higher parameter count (9.4 M) and computational load (21.3 GFLOPs) compared to some lightweight models, its significant improvement in detection accuracy justifies its complexity with reasonable cost-effectiveness. In contrast, other models like YOLOv11s-C2K3, while faster in detection speed, have a slightly inferior detection accuracy. Besides, through its unique architectural design, RepLKNet balances well a lightweight design and high performance, enabling it to excel in complex disease detection tasks. The memory footprint of YOLOv11s-RepLKNet is 20.2 MB, although slightly higher than some lightweight models (e.g., YOLOv11s-CFNet and YOLOv11s-GhostNetV2), it is still within a reasonable range. Considering its advantages in detection accuracy and speed, this level of resource usage is acceptable and can meet the demands of most practical application scenarios.

In summary, the YOLOv11 model with RepLKNet as the backbone performs exceptionally well in maize disease detection tasks, particularly in detection accuracy. Its outstanding performance in key metrics such as Precision and F1 Score, combined with a reasonable balance between detection speed and resource usage, makes it a highly competitive choice for these tasks. These results fully demonstrate RepLKNet’s excellent trade-off between lightweight design and high-performance detection, delivering a reliable and efficient solution for the detection of maize diseases.

3.2. Comparative Experiments of Various Attention Mechanisms

The subsequent trial examined the influence of various attention mechanisms on the performance of the YOLOv11 model in detecting maize diseases. The trials challenged six common attention mechanisms, including CBAM, EC, EMA, GAM, SA, SimAM, and SK, where each was integrated into the YOLOv11 model for performance evaluation. The proposed YOLOv11-RCDWD model in this study incorporates the CBAM attention mechanism based on the YOLOv11 model. The corresponding experimental results are presented in

Table 3.

The CBAM attention mechanism demonstrates excellent performance across multiple metrics, particularly excelling in Precision (90.5%), F1 Score (84.1%), mAP@0.5 (86.2%), and memory consumption (17.3 MB). Although the detection speed slightly decreases from 1.3 ms to 1.6 ms, the model’s parameter count (8.49 M) is reduced by approximately 0.93 M compared to the baseline model’s 9.42 M. Additionally, its computational load (20.6 GFLOPs) is slightly lower than the baseline model’s 21.23 GFLOPs, giving it a clear advantage in overall performance. Therefore, CBAM is the most suitable attention mechanism for maize disease detection tasks.

The EMA attention mechanism performs well in Recall (81.1%) and mAP@0.5~0.95 (64.6%) but has disadvantages in detection speed (3.3 ms) and parameter count (9.08 M), making it suitable for tasks with high recall requirements. The GAM attention mechanism performs well in Precision (88.7%) and F1 Score (82.2%). Still, its parameter count (11.91 M), computational load (23.3 GFLOPs), and memory consumption (24.2 MB) are relatively high. Its detection speed is slower (4.6 ms), making it suitable for tasks less sensitive to model complexity. The SA and SimAM attention mechanisms perform moderately across multiple metrics, particularly in Precision (SA: 84.8%, SimAM: 85.5%) and F1 Score (SA: 83.1%, SimAM: 82.0%), indicating they may not be suitable for maize disease detection tasks.

In summary, the YOLOv11s-CBAM model performs the best in maize leaf disease detection tasks, maintaining high detection accuracy while effectively reducing model parameter count and memory consumption, rendering it appropriate for implementation in real-world applications.

3.3. Ablation Experiments

We also conducted ablation studies by systematically removing various modules, e.g., RepLKNet network module, CBAM attention mechanism module, DynamicHead, WIoU loss function, and DynamicATSS sample allocation strategy, to assess their impacts on the overall performance of YOLOv11-RCDWD. To maintain the validity of comparisons, all models were trained on a consistent dataset and under standardized parameter settings. The comprehensive results of the ablation studies are detailed in

Table 4.

Introducing the RepLKNet module significantly improved the model’s detection accuracy. When used alone, RepLKNet increased Precision from 87.7% to 89.1%, Recall from 78.0% to 79.9%, mAP@0.5 from 85.3% to 87.1%, and mAP@0.5~0.95 from 63.5% to 66.7%. However, the detection speed increased from 1.3 ms to 3.2 ms, and GFLOPs increased from 21.2 M to 25.2 M, indicating that while RepLKNet enhanced performance, it also significantly increased the computational burden.

In contrast, the CBAM attention mechanism module improved Precision to 90.5%, significantly reducing the number of parameters (from 10.5 M to 8.49 M) and memory overhead (from 19.2 MB to 17.3 MB). Moreover, the detection speed slightly increased to 1.6 ms, demonstrating a good balance between accuracy and efficiency.

The DynamicHead module remarkably improved Recall, which increased from 78.0% to 82.1%. However, the detection speed significantly decreased to 6.5 ms, with slight parameters and memory overhead increases. This suggests that DynamicHead is more suitable for scenarios where high Recall is required but may not be appropriate for tasks with strict real-time requirements.

The WIoU loss function and DynamicATSS sample allocation strategy had relatively limited impacts on model performance. While WIoU slightly improved mAP@0.5 to 86.7% and mAP@0.5~0.95 to 64.4% while maintaining a high detection speed of 1.2 ms, DynamicATSS significantly increased detection time to 3.8 ms with no significant performance improvement.

Ultimately, when all modules were combined, the model achieved optimal comprehensive performance. Indeed, the Precision, Recall, F1 Score, and mAP@0.5 reached 92.6%, 85.4%, 88.9%, and 90.2%, respectively, and mAP@0.5~0.95 increased to 72.5%. Meanwhile, the detection speed remained at 1.6 ms, the number of parameters was reduced to 9.41 M, GFLOPs decreased to 19.3 M, and memory overhead was reduced to 16.4 MB. This indicates that the synergistic action of these modules significantly enhanced detection accuracy and optimized computational efficiency and memory usage, offering higher practicality and deployability for real-world applications.

In summary, the RepLKNet and CBAM modules improved the model’s precision and detection accuracy. At the same time, the DynamicHead and DynamicATSS strategies enhanced the model’s comprehensive performance by optimizing Recall and sample allocation. The WIoU loss function also improved the model’s localization accuracy and generalization ability without increasing computational complexity. Integrating these modules enabled the YOLOv11-RCDWD model to perform exceptionally well in maize leaf disease detection while balancing detection speed and model complexity well.

3.4. Comparative Experiments of the Performance of Different Network Models

To validate the effectiveness of YOLOv11s-RCDWD, it was challenged against several classic object detection models, including Faster R-CNN [

38], SSD [

39], YOLOv5s [

40], YOLOv6s [

41], YOLOv7 [

42,

43], YOLOv9s [

44], YOLOv9c [

45], YOLOv10s [

46], and YOLOv11s, under the same training environment. The evaluation metrics were Precision, Recall, F1 Score, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5~0.95, Detection Speed, Parameter count, GFLOPs, and Memory Cost. The corresponding experimental results are reported in

Table 5.

The improved model, YOLOv11s-RCDWD, significantly outperforms the competitor models in all accuracy metrics. Its Precision reaches 92.6%, Recall is 85.4%, and F1 Score is 88.9%, notably higher than Faster R-CNN and SSD. Although the YOLO series models from YOLOv5s to YOLOv11s have shown continuous improvement in accuracy, they all fall short of the improved model YOLOv11s-RCDWD. Particularly in the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5~0.95 metrics, YOLOv11s-RCDWD achieves 90.2% and 72.5%, respectively, representing improvements of 4.9% and 9.0% points over YOLOv11s, indicating its stronger object detection capability in complex scenarios.

Regarding Parameter count and GFLOPs, YOLOv11s-RCDWD remains largely consistent with YOLOv11s at 9.41M and 10.52M, respectively. These values are significantly lower than those of more complex models like YOLOv9c (21.35M parameters and 84.0 GFLOPs). Additionally, its Memory Cost is 16.4 MB, 19.2 MB less than YOLOv11s. The improved model YOLOv11s-RCDWD demonstrates superior efficiency in resource utilization.

The YOLOv11s-RCDWD model demonstrates an improved equilibrium among accuracy, speed, and complexity. Notably, its high accuracy and efficiency make it particularly suitable for practical agricultural scenarios, such as maize disease detection tasks, and it offers significant advantages when deployed on resource-constrained mobile devices. The YOLOv11s-RCDWD model excels in maize disease detection tasks, with both accuracy and efficiency surpassing other comparative models. The improved model significantly enhances detection performance by introducing RepLKNet, CBAM, DynamicHead, WIoU loss function, and the DynamicATSS sample allocation strategy, providing an effective solution for intelligent detection of maize leaf diseases in complex agricultural environments.

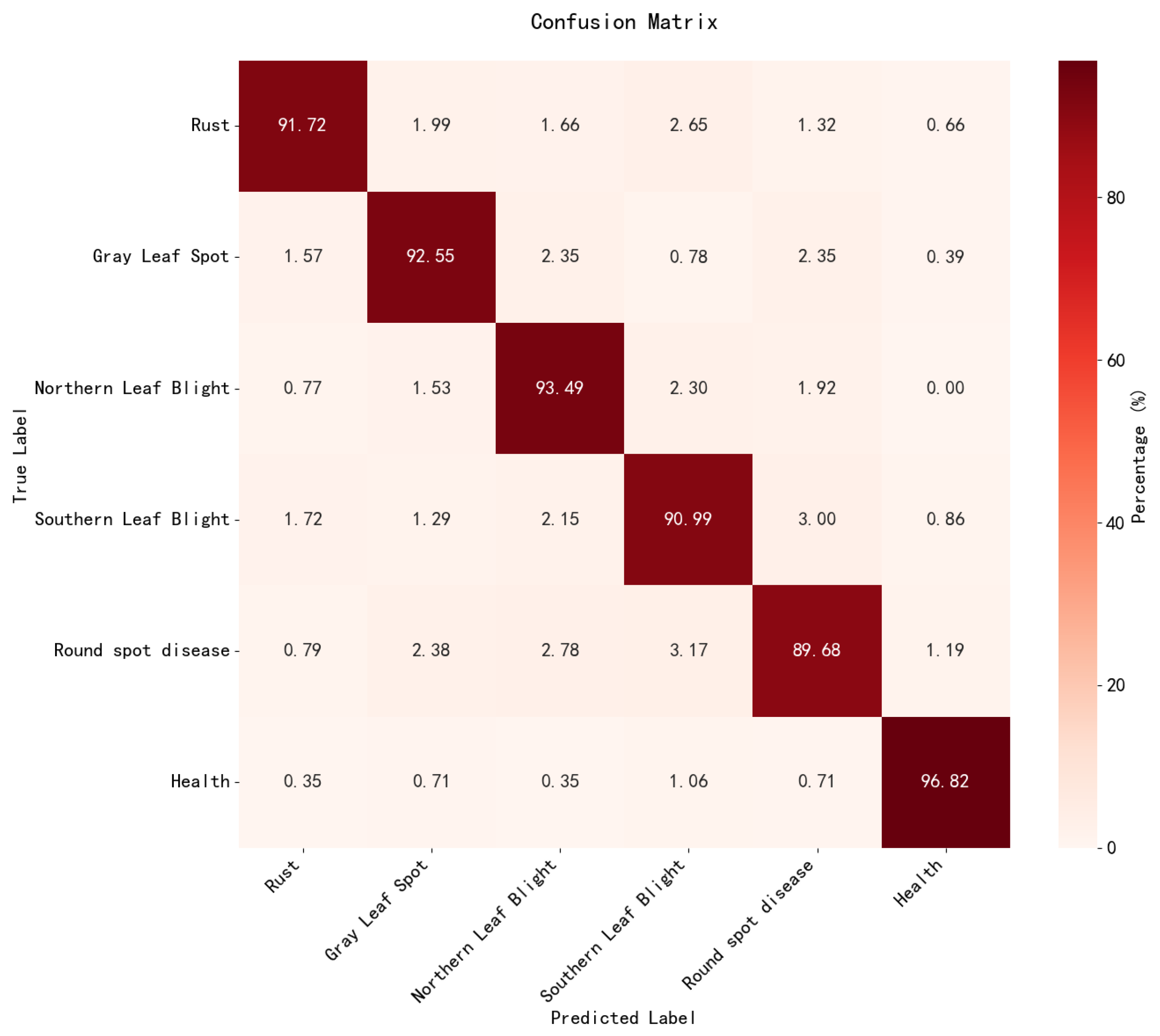

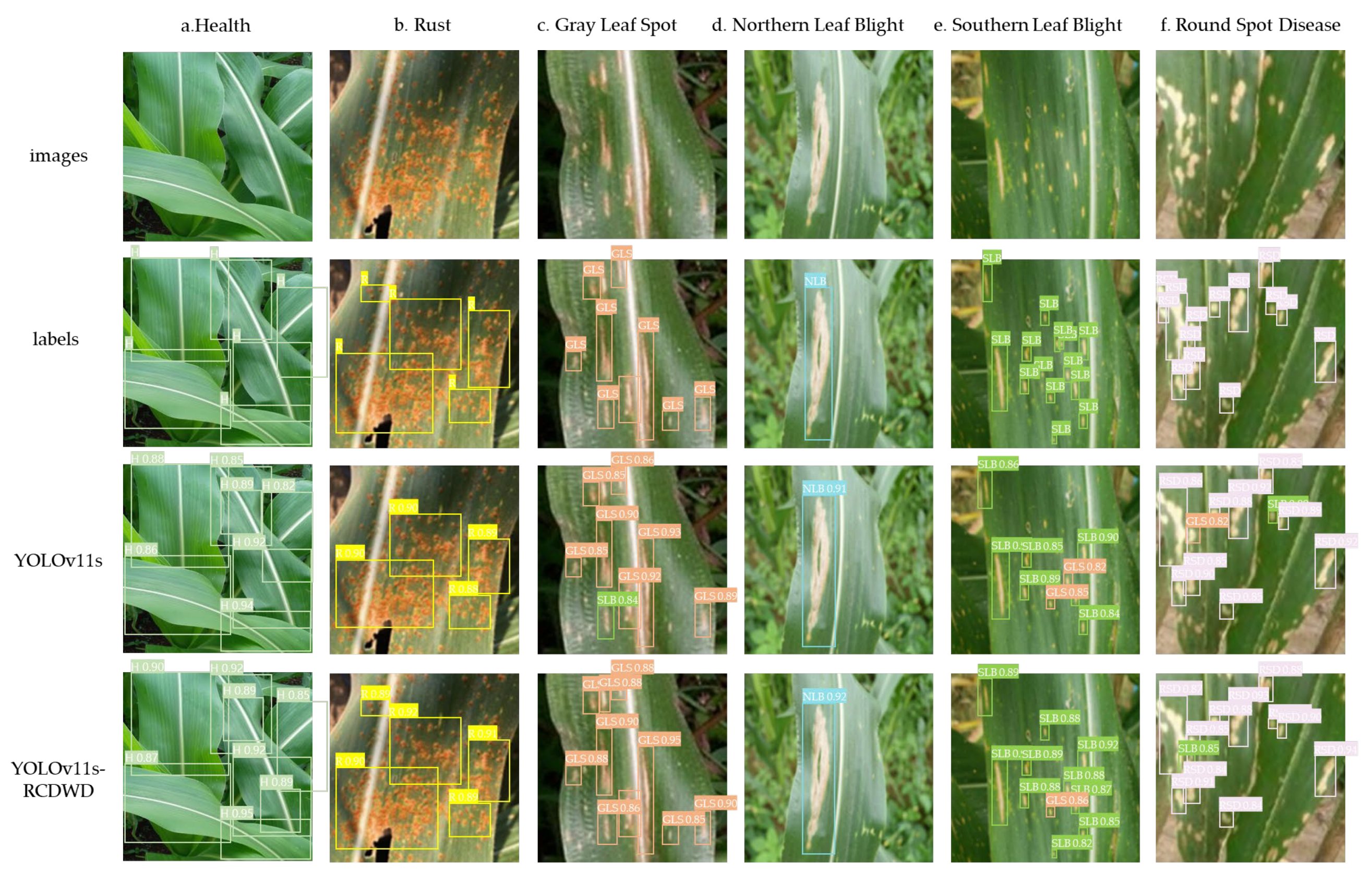

3.5. Visualization of Analysis Results

This study comprehensively evaluates and analyzes the performance of the YOLOv11s-RCDWD model in corn leaf disease identification using a confusion matrix. The confusion matrix visually presents the model’s classification performance across various categories, including correct and incorrect classifications. In

Figure 8, The diagonal elements of the confusion matrix indicate the number of samples accurately classified by the model. In contrast, the off-diagonal elements represent instances of misclassification among different categories.A detailed confusion matrix analysis allows a better understanding of the model’s recognition capabilities and shortcomings across different disease categories.

The experimental results indicate that the improved YOLOv11s-RCDWD model achieves generally high accuracy in identifying different disease categories, particularly in recognizing healthy leaves (Health), with an accuracy rate of 96.82%. The recognition accuracy for Northern Leaf Blight and Gray Leaf Spot is also relatively high, reaching 93.49% and 92.55%, respectively. However, the model exhibits some confusion in distinguishing between Round Spot Disease and Southern Leaf Blight, with accuracy rates of 89.68% and 90.99%, respectively. This may be attributed to the potential visual similarity between these two diseases, leading to misclassification by the model when differentiating between them.

Figure 9 compares the detection results of the improved YOLOv11s-RCDWD model against the original model. The mutual misclassifications observed among Gray Leaf Spot, Round Spot Disease, and Southern Leaf Blight may stem from the subtle differences present in the early stages of these diseases. Consequently, the model may not have developed sufficiently robust features to effectively distinguish between these conditions, resulting in erroneous classifications.

In summary, the YOLOv11s-RCDWD model exhibits high accuracy in the maize leaf disease identification task, particularly excelling in recognizing healthy leaves and Northern Leaf Blight. However, the model still has certain limitations in distinguishing disease categories with similar visual features, such as Rust and Gray Leaf Spot, and Southern Leaf Blight and Round Spot Disease. These limitations may stem from the similar morphological characteristics of the diseases on the leaves or insufficient sample sizes for certain categories in the training data. Thus, there is still room for improvement in the model’s performance through optimization and training.

4. Discussion

The proposed YOLOv11s-RCDWD model demonstrates outstanding performance in detecting maize leaf diseases and pests by incorporating the RepLKNet backbone network, CBAM attention mechanism, DynamicHead detection head, WIoU loss function, and DynamicATSS label assignment strategy. Its detection accuracy, speed, and resource efficiency significantly surpass existing models.

The model demonstrates an F1 Score of 88.9%, a Precision of 92.6%, and a Recall of 85.4%. These findings show improvements of 4.9% and 9.0% over the YOLOv11 baseline model. This suggests that the enhanced model is better able to locate and detect pests and diseases of maize leaves in complicated environments. Notably, the detection time for a single image is only 1.6 ms, significantly faster than traditional models (e.g., Faster R-CNN and YOLOv8), meeting the requirements for real-time detection. Furthermore, the model’s parameter count (0.81 M) and computational load (27.23 GFLOPs) are significantly lower than those of comparative models, with a memory footprint of only 6.46 MB, making it suitable for deployment on resource-constrained agricultural mobile devices.

Compared to classic models such as SSD, Faster R-CNN, and YOLOv8, YOLOv11s-RCDWD exhibits clear detection accuracy and speed advantages. For instance, while Faster R-CNN performs well in detecting small targets, its detection speed is slower, making it challenging to meet real-time detection needs. On the other hand, YOLOv8 improves speed but suffers from lower detection accuracy in complex backgrounds. Compared to recently proposed improved models, YOLOv11s-RCDWD outperforms them in detection accuracy and resource efficiency. For example, although YOLOv9c has high detection accuracy, its large parameter count and computational load make deployment on devices with limited resources difficult. In contrast, YOLOv11s-RCDWD significantly reduces model complexity through its lightweight design. Compared to common attention mechanisms (e.g., ECA, GAM, and SimAM) and loss functions (e.g., CIoU and DIoU), CBAM and WIoU enhance detection accuracy and localization precision. For instance, CBAM’s spatial attention and du-al-channel processes greatly enhance the model’s capacity to extract important characteristics. By dynamically modifying bounding box regression weights, WIoU simultaneously improves the model’s learning capacity for difficult data.

There are a number of important reasons why the YOLOv11s-RCDWD model performs better than other variants. By adding large-kernel convolutions, the RepLKNet backbone network improves the mod-el’s capacity to collect global characteristics. This architecture is particularly effective for detecting maize leaf diseases and pests in natural scenes characterized by complex backgrounds. Furthermore, the dual-channel and spatial attention processes of the CBAM attention mechanism improve the model’s ability to extract features, greatly reducing false positives and missed detections. Additionally, the DynamicHead detection head adapts to detection tasks of varied sizes and complexities by dynamically adjust-ing its settings, therefore greatly enhancing the model’s capacity to recognize mul-ti-scale objects. By dynamically modifying regression weights, the WIoU loss function increases bounding box localization accuracy and fortifies the model’s capacity to learn from difficult samples. Finally, the DynamicATSS label assignment approach op-timizes sample distribution during training by dynamically altering the selection mechanism for positive and negative samples, considerably increasing the model’s gener-alization capabilities.

Despite its excellent performance in maize leaf disease and pest detection, the YOLOv11s-RCDWD model has some limitations. The dataset used is limited in size and diversity, affecting the model’s generalization ability. Future work should focus on expanding the dataset’s scale and diversity to improve the model’s robustness in practical applications. Although YOLOv11s-RCDWD demonstrates excellent resource efficiency, there is still room for further computational load and parameter count reduction. Future research could explore more efficient model compression methods (e.g., knowledge distillation and quantization) and acceleration techniques (e.g., hardware acceleration) to reduce computational costs. Additionally, the current model is primarily designed for maize leaf disease and pest detection, and its generalization ability to other crops and scenarios has not been fully validated. Future efforts should extend this method to disease and pest detection in different crops, providing more comprehensive technical support for smart agriculture development.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes an improved YOLOv11-based model, YOLOv11-RCDWD, for detecting maize leaf diseases and pests. Incorporating the RepLKNet module, CBAM module, DynamicHead detection head, WIoU loss function, and DynamicATSS label assignment strategy significantly enhanced the model’s performance on maize leaf disease and pest detection tasks. Experimental results demonstrate that:

(1) The improved model, YOLOv11s-RCDWD, exhibits the best detection performance, with all accuracy metrics surpassing those of the comparative models. Its Precision reaches 92.6%, Recall is 85.4%, and F1 Score is 88.9%, all higher than other models.

(2) In terms of mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5~0.95, YOLOv11s-RCDWD achieves 90.2% and 72.5%, respectively, an improvement of 4.9% and 9.0% over YOLOv11s, indicating stronger detection capabilities in complex scenarios.

(3) The parameter count (Parameter) and computational load (GFLOPs) of YOLOv11s-RCDWD remain largely consistent with YOLOv11s, at 9.41M and 10.52M, respectively, which are significantly lower than those of more complex models like YOLOv9c (21.35 M parameters and 84.0 GFLOPs). Additionally, its memory footprint (Memory Cost) is 16.4 MB, a reduction from YOLOv11s’s 19.2 MB, demonstrating that the improved model is more efficient in resource utilization.

(4) Different backbone networks exhibit significant performance variations in maize disease detection tasks. The YOLOv11 model with RepLKNet as the backbone (YOLOv11s-RepLKNet) demonstrates notable comprehensive advantages in four key aspects: detection accuracy, detection speed, model complexity, and resource usage, particularly excelling in detection accuracy. RepLKNet achieves the highest values in both Precision and F1 Score, reaching 89.1% and 84.2%, respectively.

(5) Comparing seven common attention mechanisms—CBAM, EC, EMA, GAM, SA, SimAM, and SK—demonstrates that the SK attention module significantly outperforms other attention mechanisms in detection accuracy. Its Precision reaches 89.5%, and its F1 Score is 84.1%.

Furthermore, YOLOv11s-RCDWD efficiently utilizes computational resources, attaining an ideal equilibrium between detection accuracy and speed. Its streamlined architecture with the fewest parameters and FLOPs ensures minimal computational resource usage, facilitating deployment on agricultural machinery equipped with embedded systems. The findings indicate that the YOLOv11s-RCDWD model offers substantial advantages in the detection of maize leaf diseases. offering an efficient and practical solution for intelligent agricultural disease detection. Overall, YOLOv11-RCDWD performs well in maize leaf disease and pest detection tasks, providing robust technical support for intelligent agricultural disease detection. Future research could further optimize the model’s computational efficiency and extend its application to broader agricultural scenarios. Additionally, we will further enhance the scale and diversity of the dataset to improve the model’s generalization capabilities. We will also investigate more efficient model compression techniques to satisfy the deployment requirements of mobile devices. Furthermore, we aim to extend this approach to disease and pest detection in various crops, thereby providing more comprehensive technical support for the advancement of smart agriculture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.; methodology, J.H. and Y.R.; software, J.H. and W.B.L.; validation, J.H. and W.B.L.; formal analysis, J.H. and W.L.F.; investigation, Y.R.; resources, J.H.; data curation, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing J.H. and W.B.L.; visualization, W.L.F.; supervision, W.B.L.; project administration, W.B.L.; funding acquisition, W.B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Proof of Concept Fund (XJ2023230052), the Shaanxi Provincial Water Conservancy Fund Project (2024SLKJ-16), and the research project of Shaanxi Coal Geology Group Co., Ltd. (SMDZ-2023CX-14).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ranum, P.; Peña Rosas, J.P.; Garcia Casal, M.N. Global maize production, utilization, and consumption. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1312, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Li, C.; Yang, G.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, C.; Xu, B.; Feng, H.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Z.; Yang, H. The Detection of Maize Seedling Quality from UAV Images Based on Deep Learning and Voronoi Diagram Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Ficke, A.; Aubertot, J.; Hollier, C. Crop losses due to diseases and their implications for global food production losses and food security. Food Secur. 2012, 4, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.A.; Bankole, I.; Ajayi-Moses, O.; Ijila, T.; Jeje, T.; Lalit, P. Relevance of advanced plant disease detection techniques in disease and Pest Management for Ensuring Food Security and Their Implication: A review. American Journal of Plant Sciences. 2023, 14, 1260–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChant, C.; Wiesner-Hanks, T.; Chen, S.; Stewart, E.L.; Yosinski, J.; Gore, M.A.; Nelson, R.J.; Lipson, H. Automated identification of northern leaf blight-infected maize plants from field imagery using deep learning. Phytopathology. 2017, 107, 1426–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setiawan, W.; Rochman, E.; Satoto, B.D.; Rachmad, A. Machine learning and deep learning for maize leaf disease classification: A review. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol. 2406:IOP Publishing, 2022,12019.

- Jafar, A.; Bibi, N.; Naqvi, R.A.; Sadeghi-Niaraki, A.; Jeong, D. Revolutionizing agriculture with artificial intelligence: plant disease detection methods, applications, and their limitations. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1356260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, H.M.; Mohana, N.T.; Khan, B.M.; Ahmed, S.M.; Hossain, M.; Islam, K.S.; Redoy, M.H.; Ferdush, J.; Bhuiyan, M.; Hossain, M.M. Present and future scopes and challenges of plant pest and disease (P&D) monitoring: Remote sensing, image processing, and artificial intelligence perspectives. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment. 2023, 32, 100996.

- Shi, Y.; Duan, Z.; Qing, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, F.; Yuwen, X. YOLOV9S-Pear: A lightweight YOLOV9S-Based improved model for young Red Pear Small-Target recognition. Agronomy. 2024, 14, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, K.P.; Das, H.; Sahoo, A.K.; Moharana, S.C. Maize leaf disease detection and classification using machine learning algorithms. Progress in Computing, Analytics and Networking: Proceedings of ICCAN 2019:Springer, 2020,659-69.

- Paul, H.; Udayangani, H.; Umesha, K.; Lankasena, N.; Liyanage, C.; Thambugala, K. Maize leaf disease detection using convolutional neural network: a mobile application based on pre-trained VGG16 architecture. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J.; Niu, H.; Scott, J.L.L.; Bhandari, M.; Landivar, J.A.; Bednarz, C.W.; Duffield, N. Cotton Yield Prediction via UAV-Based Cotton Boll Image Segmentation Using YOLO Model and Segment Anything Model (SAM). Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Ma, C.; Huang, Y.; Hussain, A. Improved YOLOv8 Model for Phenotype Detection of Horticultural Seedling Growth Based on Digital Cousin. Agriculture. 2024, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngugi, L.C.; Abelwahab, M.; Abo-Zahhad, M. Recent advances in image processing techniques for automated leaf pest and disease recognition–A review. Information Processing in Agriculture. 2021, 8, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Longchamps, L. Comparative performance of YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11 and Faster R-CNN models for detection of multiple weed species. Smart Agricultural Technology. 2024, 9, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, L.; Yue, J.; Ding, R.; Lu, Y.; Liu, J.; Qiao, H. GVC-YOLO: A Lightweight Real-Time Detection Method for Cotton Aphid-Damaged Leaves Based on Edge Computing. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Du, X.; Sapkota, R.; Ma, Z.; Cheng, H. YOLOv10-pose and YOLOv9-pose: Real-time strawberry stalk pose detection models. Comput. Ind. 2025, 165, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Feng, K.; Qian, K.; Wang, Y.; Qin, S. Strawberry maturity recognition algorithm combining dark channel enhancement and YOLOv5. Sensors. 2022, 22, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Cai, Y.; Li, Y.; Qi, X.; Qiu, X.; Yao, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W. A method for small-sized wheat seedlings detection: from annotation mode to model construction. Plant Methods. 2024, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Lin, J. Precision agriculture with YOLO-Leaf: advanced methods for detecting apple leaf diseases. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1452502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Han, B.; Dong, L.; Zhang, J. COTTON-YOLO: Enhancing Cotton Boll Detection and Counting in Complex Environmental Conditions Using an Advanced YOLO Model. Applied Sciences. 2024, 14, 6650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yao, J.; Teng, G. Corn leaf spot disease recognition based on improved YOLOv8. Agriculture. 2024, 14, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Meng, F.; Fan, C.; Zhang, M. Identification of maize leaf diseases using improved deep convolutional neural networks. Ieee Access. 2018, 6, 30370–30377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, C.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, M.; Ye, Z.; He, M. A High-Precision Identification Method for Maize Leaf Diseases and Pests Based on LFMNet under Complex Backgrounds. Plants. 2024, 13, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, Y.; He, X.; Wu, X. Northern maize leaf blight detection under complex field environment based on deep learning. Ieee Access. 2020, 8, 33679–33688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Meng, Y.; Yu, X.; Bi, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, R.; Tian, J. Mbab-yolo: A modified lightweight architecture for real-time small target detection. Ieee Access. 2023, 11, 78384–78401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.; Salathé, M. An open access repository of images on plant health to enable the development of mobile disease diagnostics. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:1511.08060. 2015.

- Moschidis, C.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Annotation tools for computer vision tasks. Seventeenth International Conference on Machine Vision (ICMV 2024), Vol. 13517:SPIE, 2025,372-9.

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:2410.17725. 2024.

- Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Scaling up your kernels to 31x31: Revisiting large kernel design in cnns. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022,11963-75.

- Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Urtasun, R.; Zemel, R. Understanding the effective receptive field in deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2016, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018,3-19.

- Dai, X.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, B.; Chen, D.; Liu, M.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L. Dynamic head: Unifying object detection heads with attentions. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021,7373-82.

- Nowozin, S. Optimal decisions from probabilistic models: the intersection-over-union case. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2014,548-55.

- Tong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yu, R. Wise-IoU: bounding box regression loss with dynamic focusing mechanism. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:2301.10051. 2023.

- Zhang, F.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y. Label assignment matters: A gaussian assignment strategy for tiny object detection. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2024.

- Zhang, T.; Luo, B.; Sharda, A.; Wang, G. Dynamic label assignment for object detection by combining predicted ious and anchor ious. J. Imaging. 2022, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Ieee Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14:Springer, 2016,21-37.

- Ma, L.; Yu, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J. Maize leaf disease identification based on yolov5n algorithm incorporating attention mechanism. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:2209.02976. 2022.

- Wang, C.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023,7464-75.

- Zhang, C.; Hu, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhao, Y. A YOLOv7 incorporating the Adan optimizer based corn pests identification method. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1174556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yeh, I.; Mark Liao, H. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. European conference on computer vision:Springer, 2024,1-21.

- Gharat, K.; Jogi, H.; Gode, K.; Talele, K.; Kulkarni, S.; Kolekar, M.H. Enhanced Detection of Maize Leaf Blight in Dynamic Field Conditions Using Modified YOLOv9. 2024 IEEE Space, Aerospace and Defence Conference (SPACE):IEEE, 2024,140-3.

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2025, 37, 107984–8011. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).