Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Collection

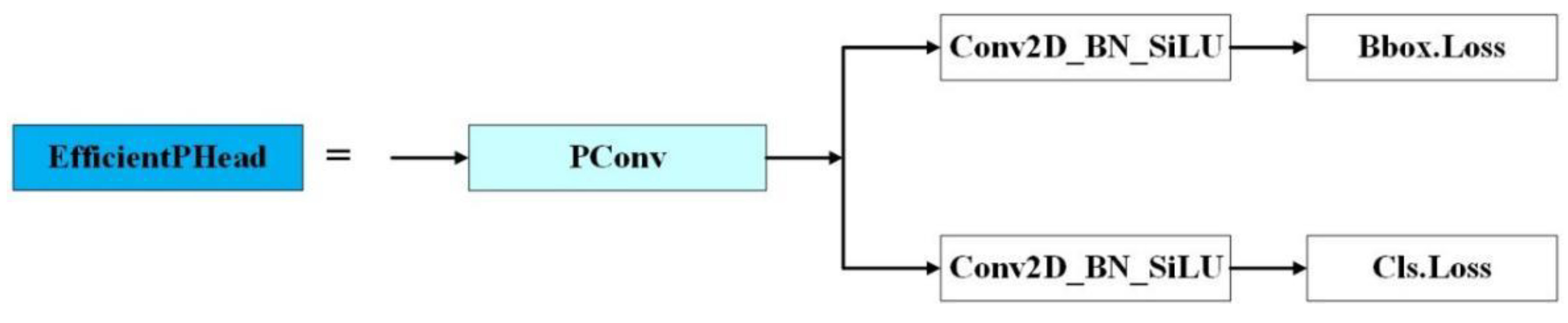

2.2. TLDDM Model

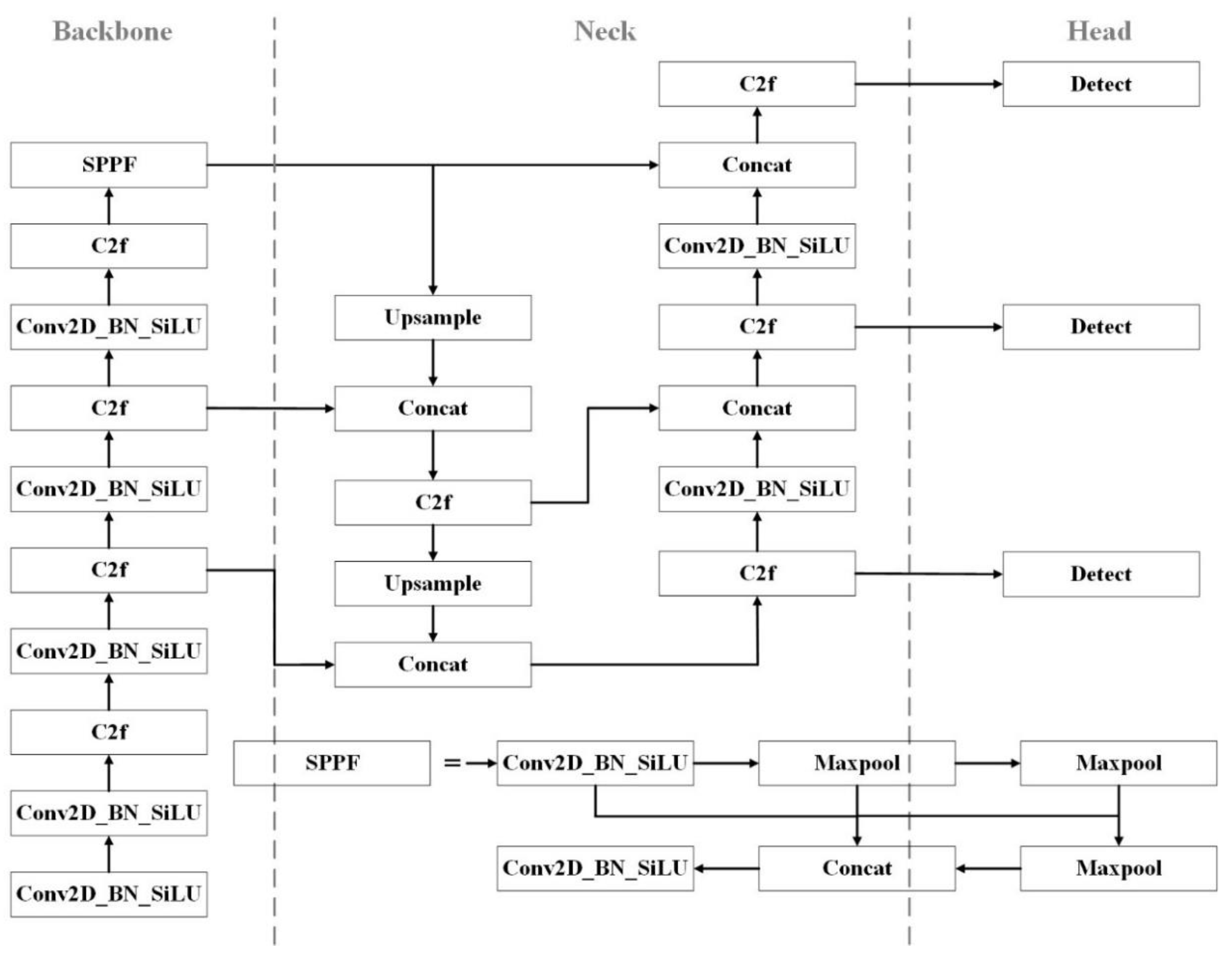

2.2.1. YOLOv8 Model

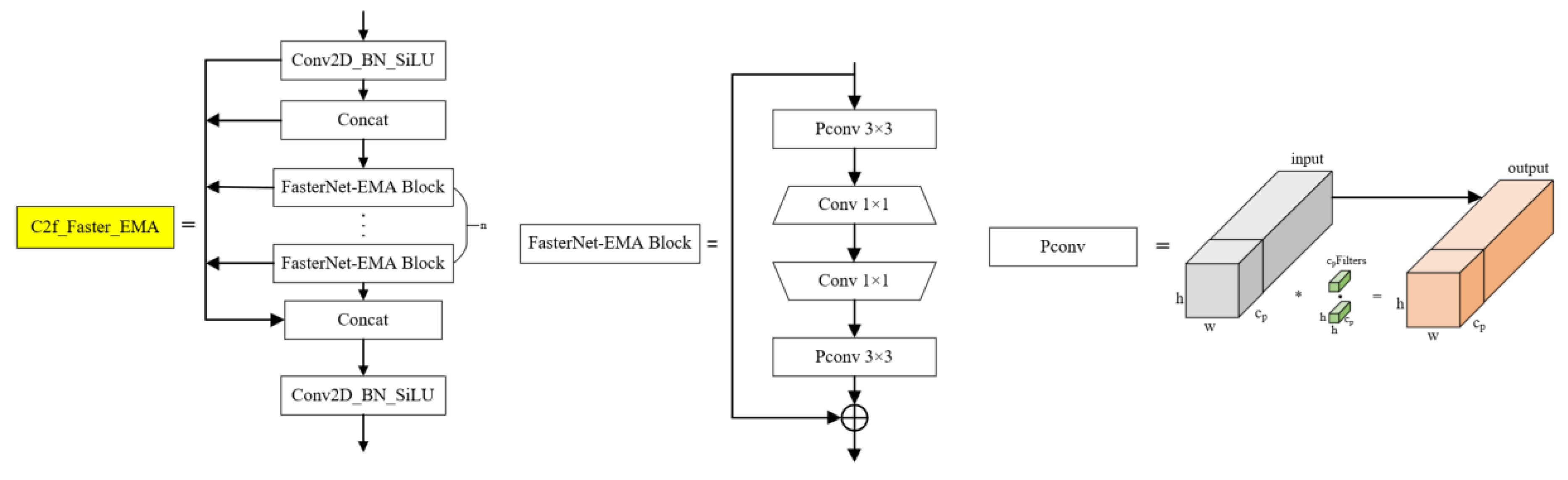

2.2.2. C2f-faster-EMA

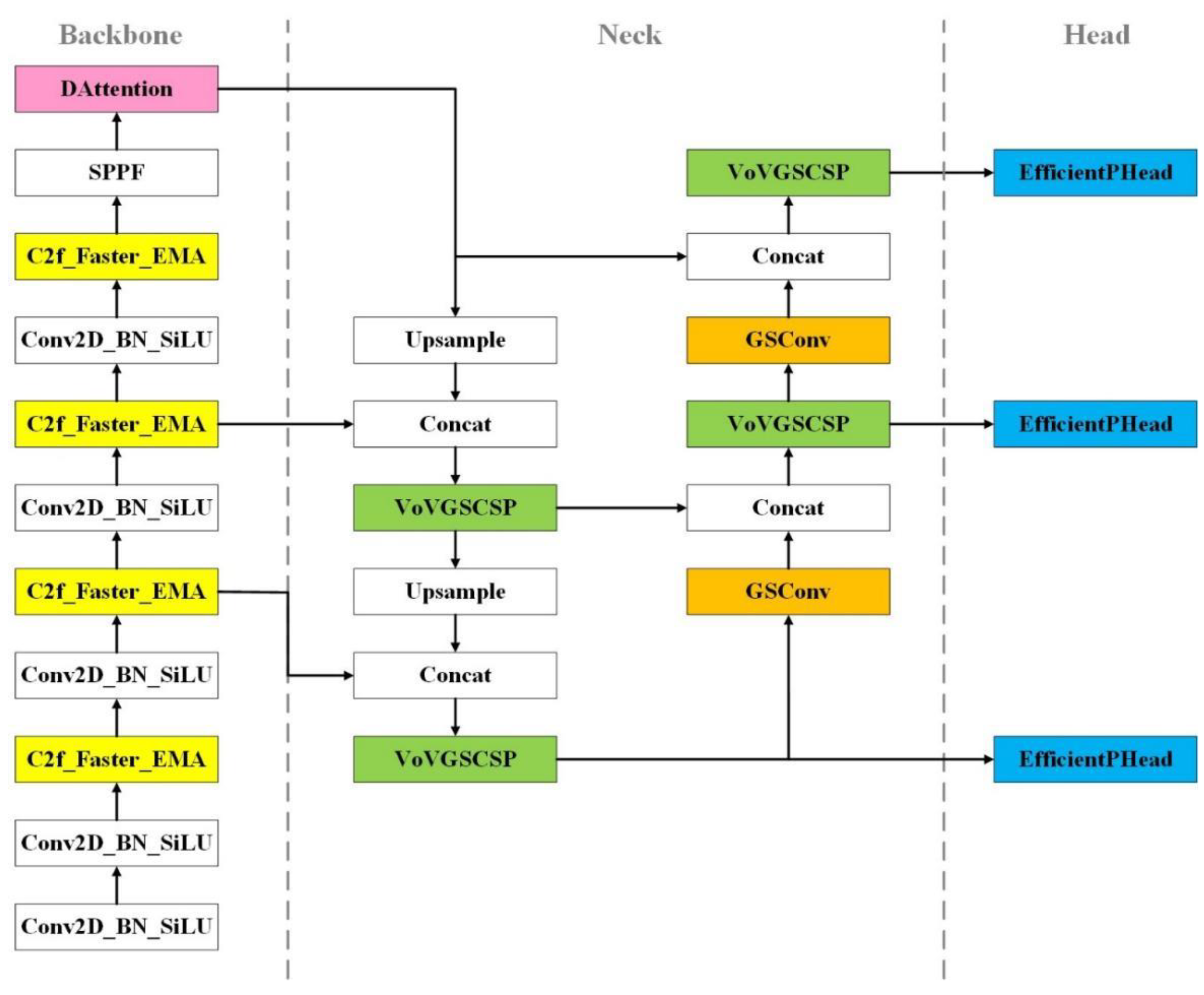

where h and w represent the width and height of the feature map, respectively; k is the kernel size; and cp denotes the number of channels involved in the convolution operation. Typically, cp equals one-fourth of the channels used in standard convolution. Consequently, the FLOPS of PConv are merely 1/16 of those in standard convolution.

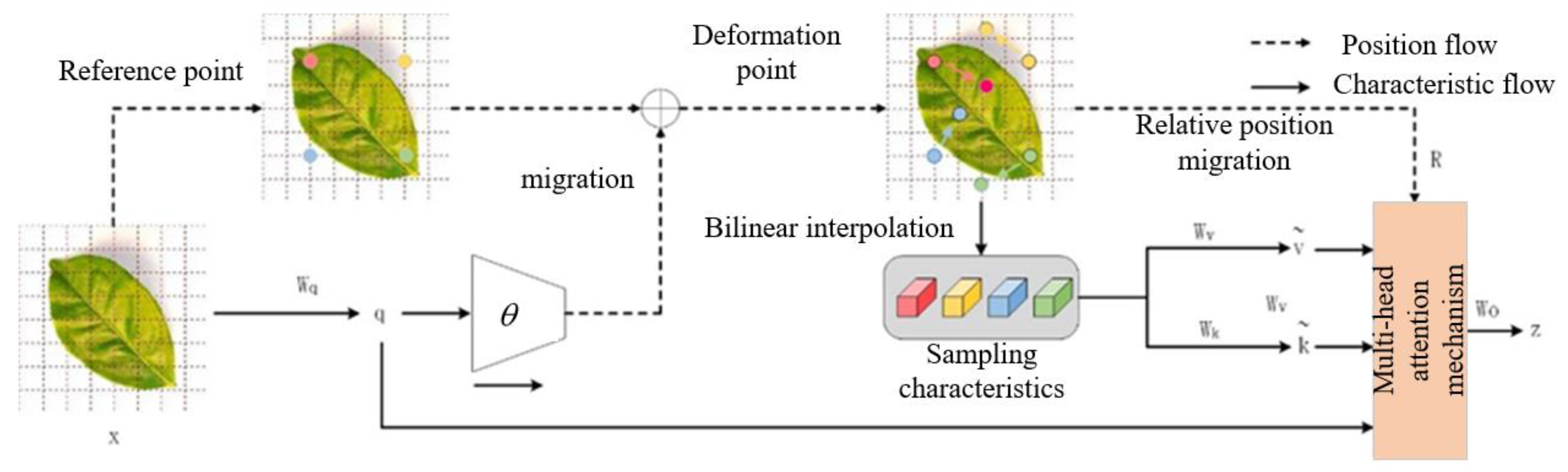

where h and w represent the width and height of the feature map, respectively; k is the kernel size; and cp denotes the number of channels involved in the convolution operation. Typically, cp equals one-fourth of the channels used in standard convolution. Consequently, the FLOPS of PConv are merely 1/16 of those in standard convolution.2.2.3. Deformable Attention

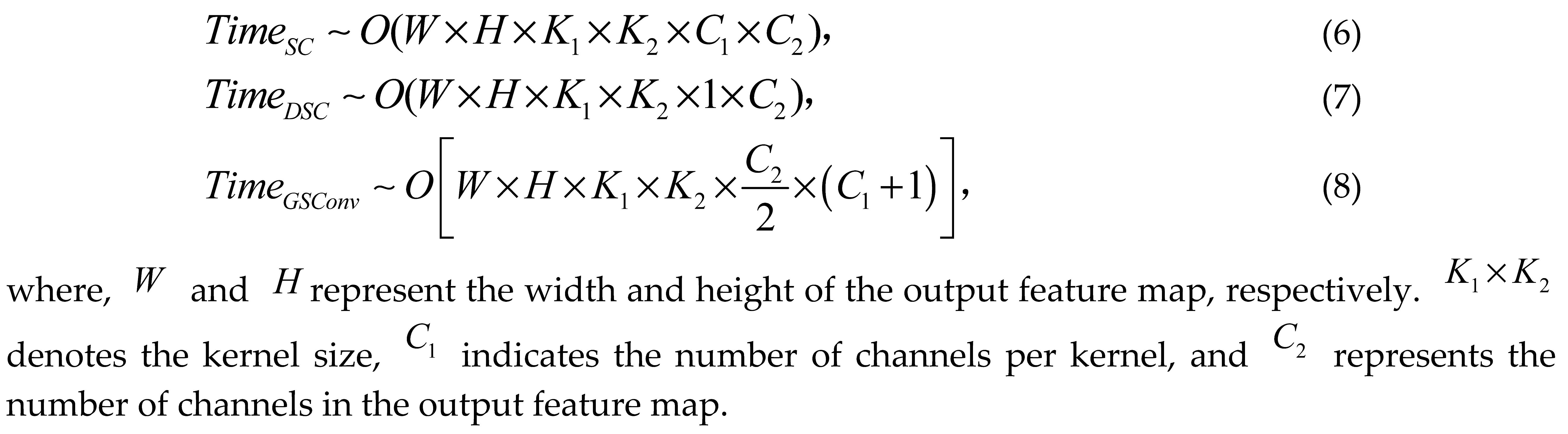

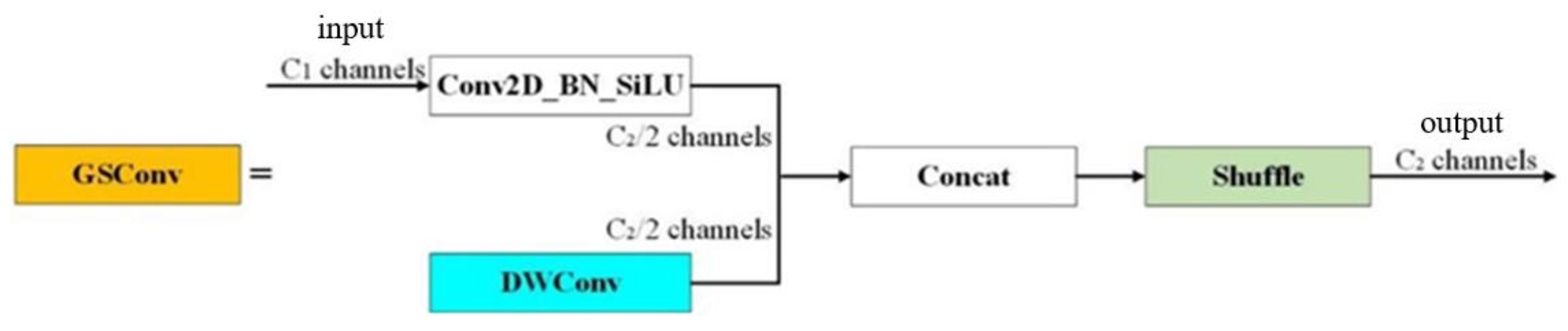

2.2.4. Slimneck

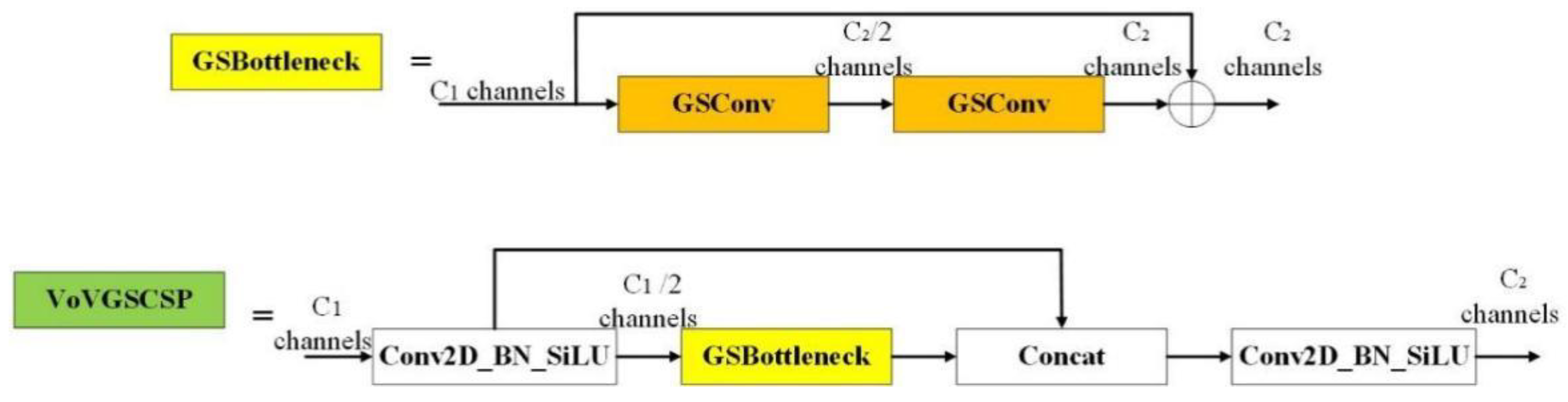

2.2.5. EfficientPHead: A Lightweight Detection Head

2.2.6. TLDDM Model

2.3. Model Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Configuration

3.2. Ablation Experiment

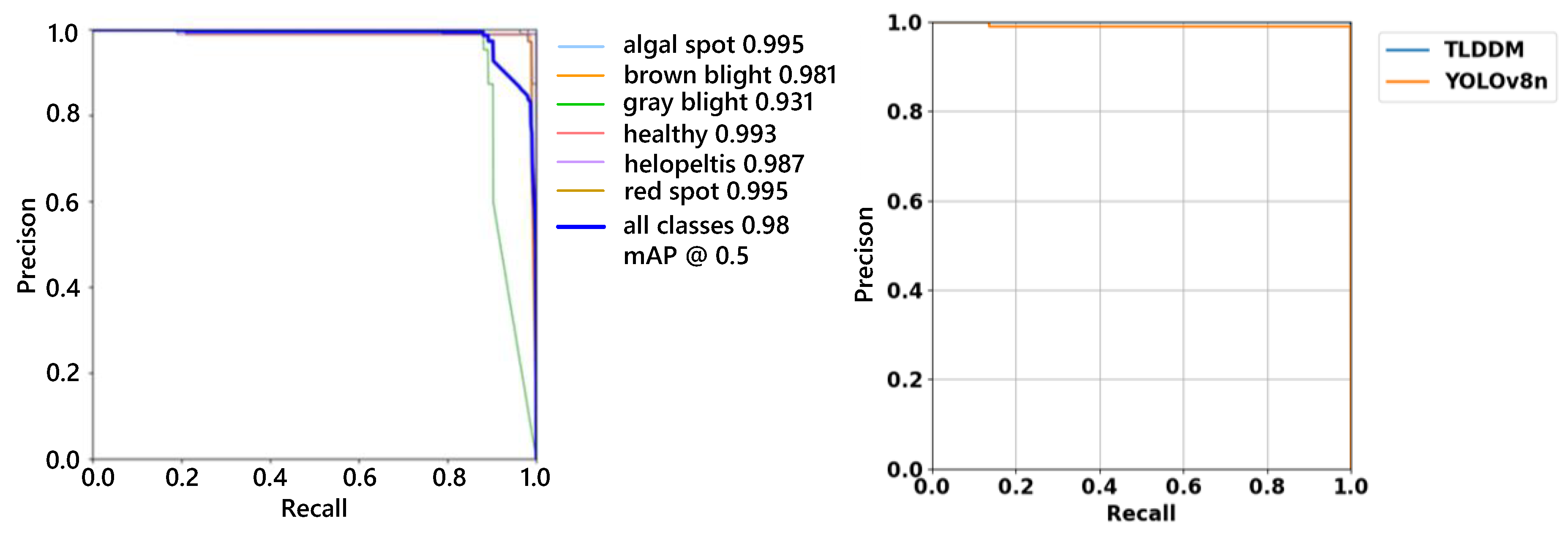

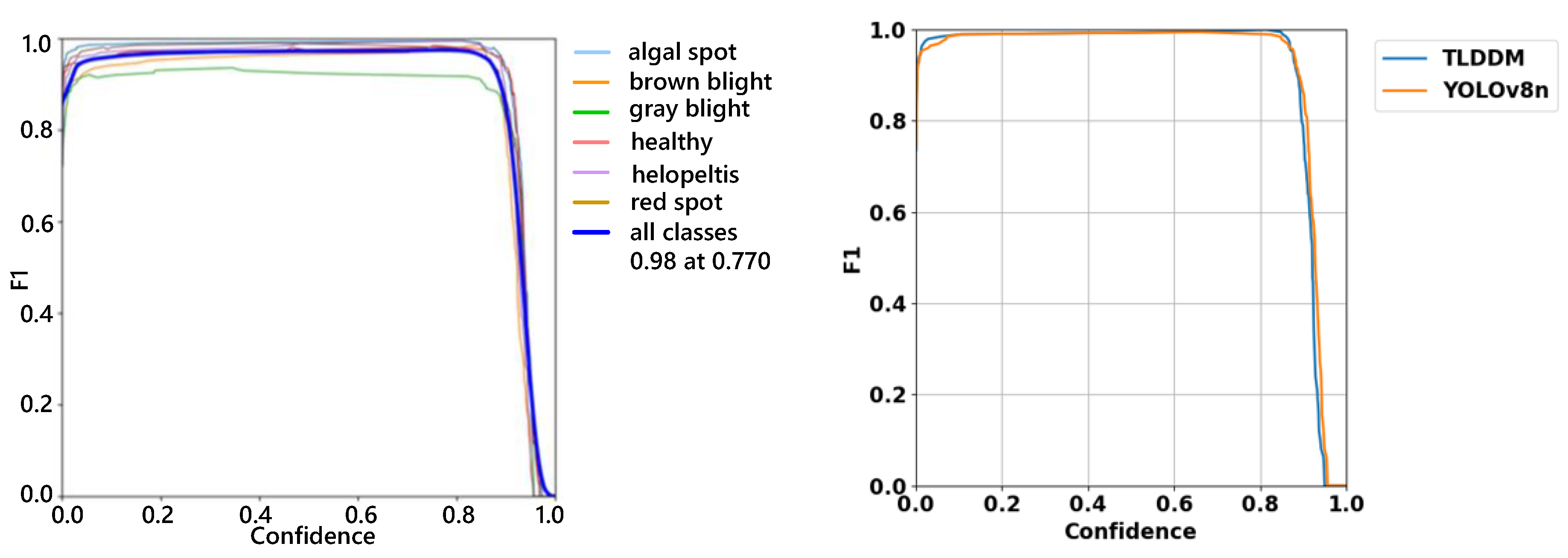

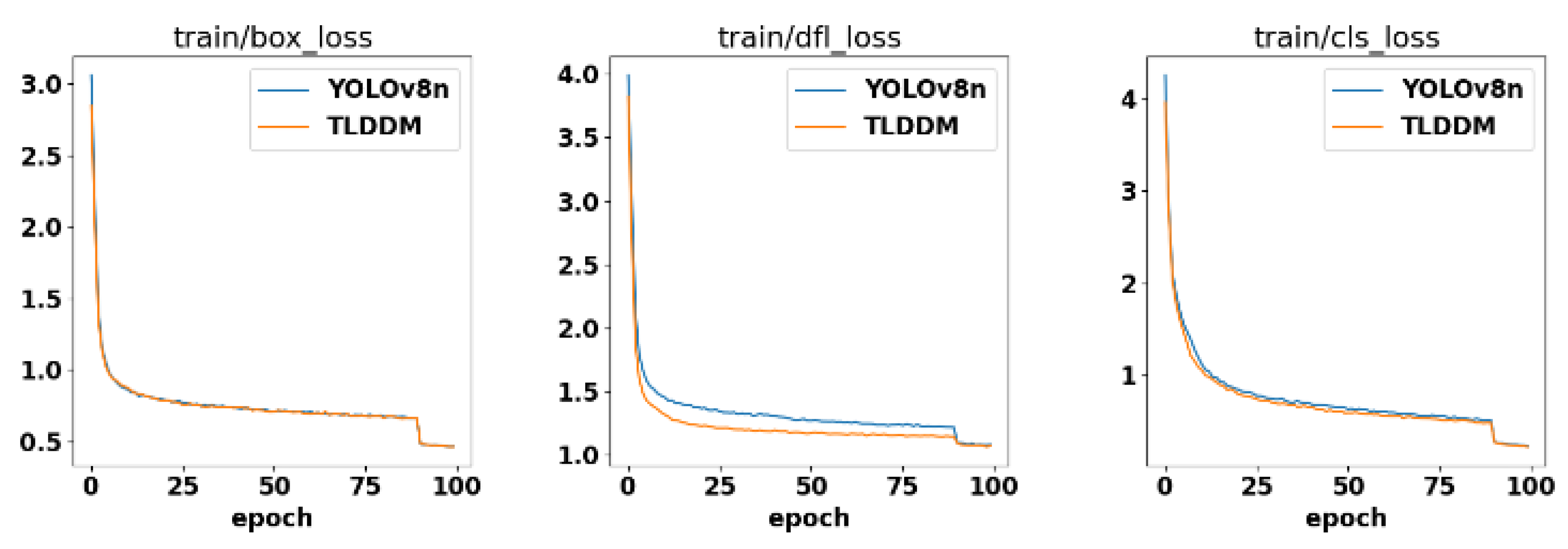

3.3. Comparative Experiments

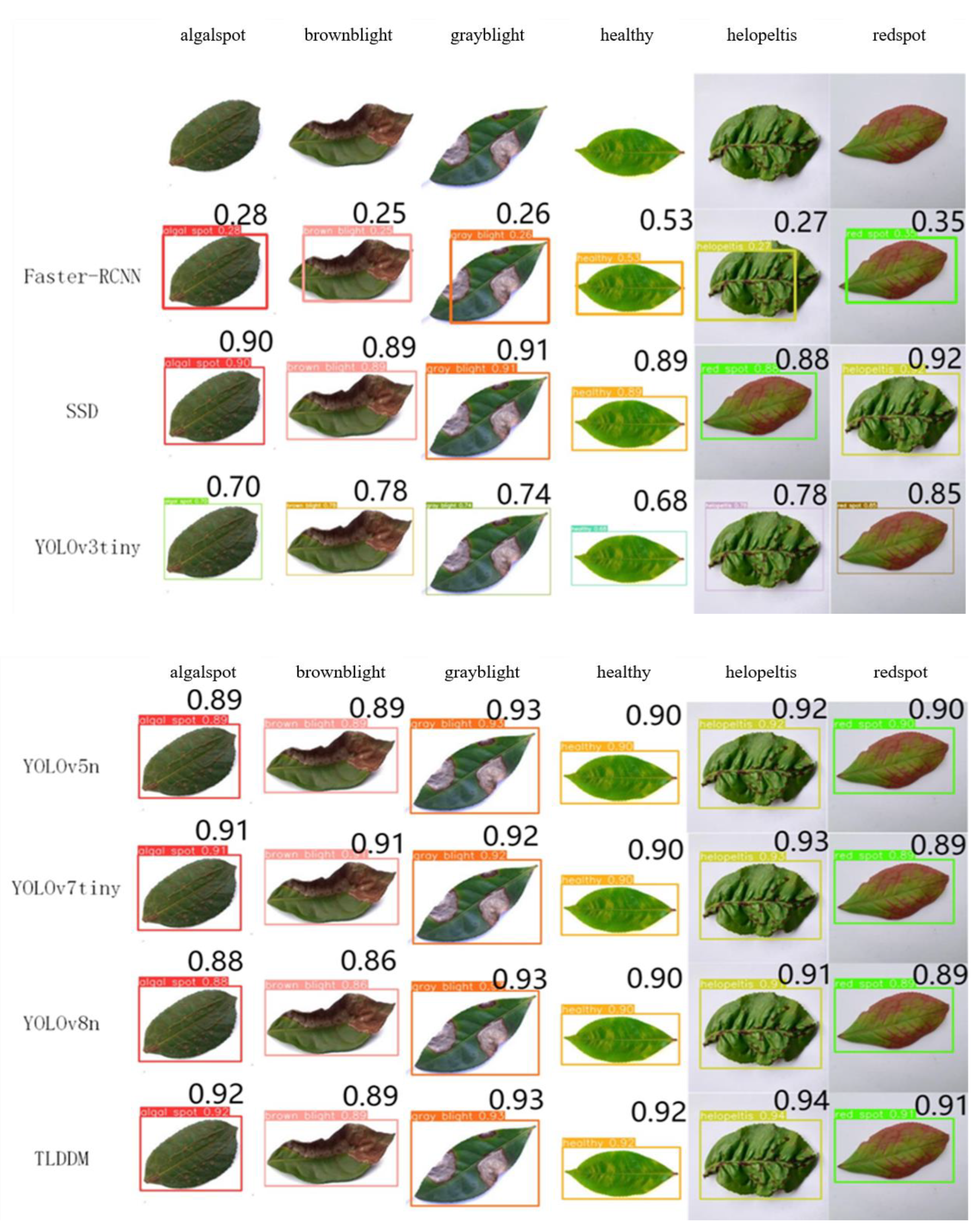

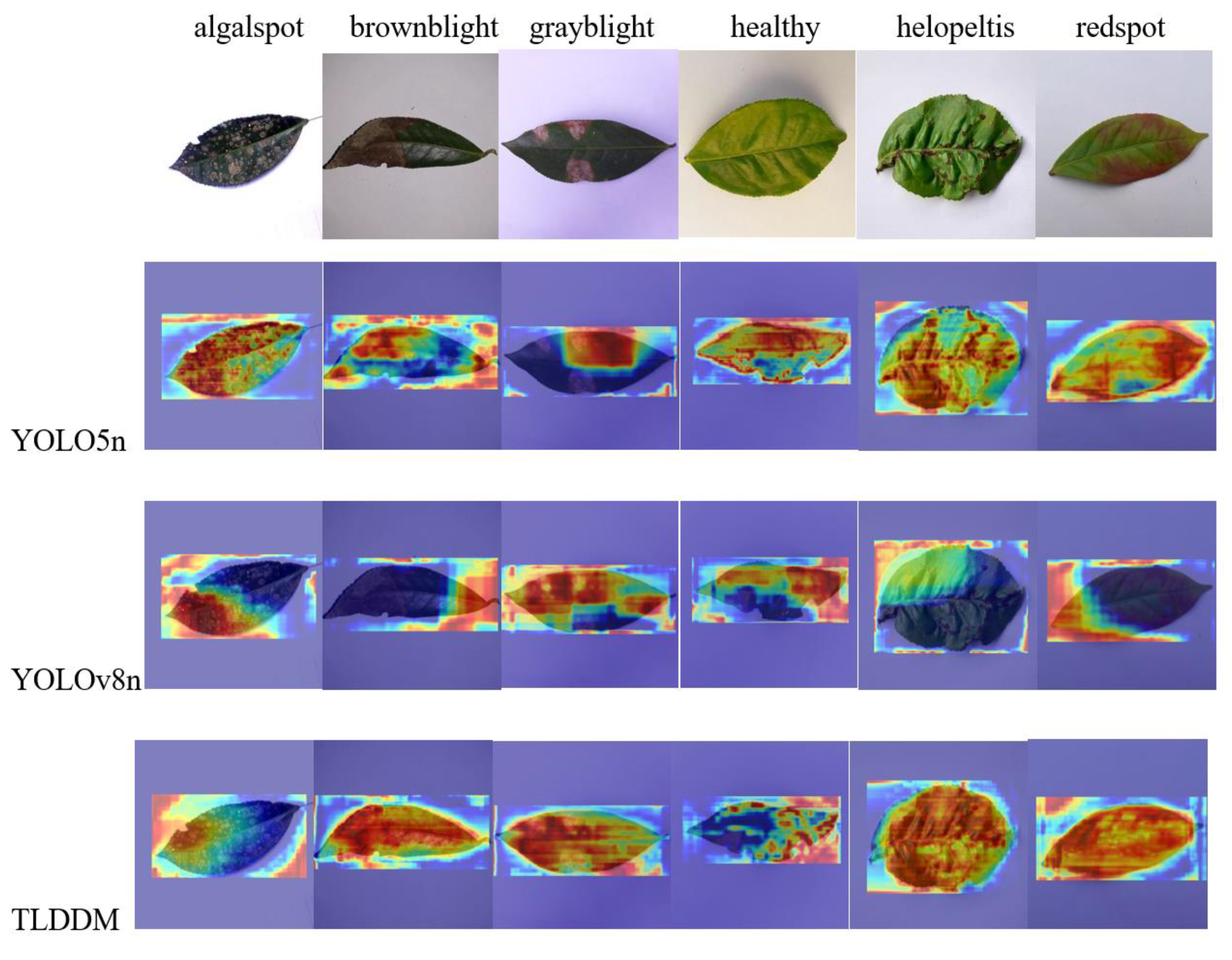

3.4. Comparison of Test Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y. Investigation on the types of pests and diseases in Shangluo tea trees and the distribution of major pests and diseases. Journal of Shanxi Agricultural University (Natural Science Edition) 2018, 38, 33–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, W.; Fan, T.; Hu, G.; Liang, D.; Li, H. Detection and identification of tea leaf diseases based on AX-RetinaNet. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauriegel, E.; Giebel, A.; Geyer, M.; Schmidt, U.; Herppich, W. Early detection of Fusarium infection in wheat using hyper-spectral imaging. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2011, 75, 304–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabira, K.; Nalini, K.; Amiya, K.; Santi, K. Deep feature based rice leaf disease identification using support vector machine. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 175, 105527. [Google Scholar]

- Behmann, J.; Steinrücken, J.; Plümer, L. Detection of early plant stress responses in hyperspectral images. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2014, 93, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Yang, C.; He, Y. Hyperspectral imaging for classification of healthy and gray mold diseased tomato leaves with different infection severities. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2017, 135, 154–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, X.; You, Z.; et al. Leaf image based cucumber disease recognition using sparse representation classification. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2017, 134, 135–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Mou, R.; Hasan, M.; Chakraborty, S.; Razzak, M. Recognition and detection of tea leaf's diseases using support vector machine. proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 14th International Colloquium on Signal Processing & Its Applications (CSPA), F, 2018. IEEE.

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, L. ; Dong, Wei; Rao Y. SLIC_SVM based leaf diseases saliency map extraction of tea plant. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2019, 157, 102–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Lan, L.; Xu, J.; Sun, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Hu, J.; Wang, B. Smart Agricultural Pest Detection Using I-YOLOv10-SC: An Improved Object Detection Framework. Agronomy 2025, 15, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, M. A low shot learning method for tea leaf's disease identification - sciencedirect. Computers & Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 163, 104852–104852. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y. Identification of tea leaf diseases by using an improved deep convolutional neural network. Sustain Computation Information System 2019, 24, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cai, D.; Li, G. Image recognition of four rice leaf diseases based on deep learning and support vector machine. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2020, 179, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, F.; Yang, S.; Li, L.; Feng, Z. A survey of deep learning-based object detection. IEEE access 2019, 7, 128837–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Zhang, W.; Chen, A.; He, M.; Ma, X. Rapid detection of rice disease based on FCM-KM and faster R-CNN fusion. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 7, 143190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.; Berg, A. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In 2016: 14th European Conference on Computer Vision–ECCV, The Netherlands, 2016, Springer, Part I 14: 21-37).

- Lin, T.; Goyal, P. , Girshick, R.; Focal loss for dense object detection. proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, F, 2017.

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition(CVPR), F, 2016.

- Wu, D.; Lv, S.; Jiang, M.; Song, H. Using channel pruning-based YOLO v4 deep learning algorithm for the real-time and accurate detection of apple flowers in natural environments. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 178, 105742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Nouaze, J. Touko Mbouembe. YOLO-tomato: A robust algorithm for tomato detection based on YOLOv3. Sensors 2020, 20.7, 2145. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, F.; Chen, D.; Lu, Y.; Li, Z. YOLOWeeds: A novel benchmark of YOLO object detectors for multi-class weed detection in cotton production systems. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 205, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, E.; Liang, Z. Apple detection during different growth stages in orchards using the improved YOLO-V3 model. Computers and electronics in agriculture, 2019, 157, 417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon J, Farhadi A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv arXiv:1804.02767, 2018.

- Roy A M, Bose R, Bhaduri J. A fast accurate fine-grain object detection model based on YOLOv4 deep neural network. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 3895–921.

- Bochkovskiy A, Wang C., Liao H. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv arXiv:2004.10934, 2020.

- Sun C, Huang C, Zhang H. Individual tree crown segmentation and crown width extraction from a heightmap derived from aerial laser scanning data using a deep learning framework. Frontiers in plant science 2022, 13, 914974.

- Dai, G.; Fan, J. An industrial-grade solution for crop disease image detection tasks. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 921057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.; Nguyen, H.; Tran, H.; Quach, L. Combining autoencoder and YOLOv6 model for classification and disease detection in chickens. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Intelligent Information Technology 2023, 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, H. Study on lightweight model of maize seedling object detection based on YOLOv7. Applied sciences 2023, 13, 7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.; Chan, S. Run, don't walk: chasing higher FLOPS for faster neural networks. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2023, IEEE, 12021-12031.

- Chen, J.; Ma, A.; Huang, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, T. Efficient and lightweight grape and picking point synchronous detection model based on key point detection. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, E.; Han, G.; Zhao, S.; Ma, Y.; Lv, Y.; Bai, Z. Regulation of Meat Duck Activeness through Photo period Based on Deep Learning. Animals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Kweon, I. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 2018, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2018, IEEE, 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, D.; He, S.; Zhang, G.; Luo, M.; Guo, H.; Zhan, J.; Huang, Z. Efficient multi-scale attention module with cross-spatial learning. In ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 1-5.

- Xia, Z.; Pan, X.; Song, S.; Li, L.; Huang, G. Vision transformer with deformable attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2022; 4794-4803. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, F.; Matteucci, I. Partial Model Checking for the Verification and Synthesis of Secure Service Compositions. In Public Key Infrastructures, Services and Applications. EuroPKI 2013. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 8341. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Q. Slim-neck by GSConv: A better design paradigm of detector architectures for autonomous vehicles. ArXiv abs/2206.02424 (2022): n. pag.

- Sozzi, M.; Cantalamessa, S.; Cogato, A.; Kayad, A.; Marinello, F. Automatic Bunch Detection in White Grape Varieties Using YOLOv3, YOLOv4, and YOLOv5 Deep Learning Algorithms. Agronomy 2022, 12, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Train | Val | Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| algal spot | 681 | 109 | 210 |

| brown blight | 612 | 81 | 174 |

| gray blight | 714 | 92 | 194 |

| healthy | 693 | 104 | 203 |

| helopeltis | 718 | 95 | 187 |

| redspot | 688 | 106 | 206 |

| Training parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Momentu | 0.937 |

| Weight_decay | 0.0005 |

| Batch_size | 16 |

| Learning_rate | 0.01 |

| Epochs | 101 |

| Model | C2f-Faster-EMA | DAttention | Slimneck | Efficient PHead |

AP(%) | Fps | F1 | Size(MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8n | 97.9 | 82.0 | 0.87 | 6.3 | ||||

| Model1 | ✔ | 98.0 | 64.1 | 0.97 | 5.5 | |||

| Model2 | ✔ | ✔ | 98.1 | 69.5 | 0.98 | 6.0 | ||

| Model3 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 97.8 | 77.5 | 0.98 | 5.6 | |

| TLDDM | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 98.0 | 98.2 | 0.98 | 4.3 |

| Model | Weight/MB | AP/% | fps | Precision/% | Recall/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster R-CNN | 111.5 | 77.68 | 20 | 75.34 | 79.21 |

| SSD | 102.7 | 73.96 | 44 | 73.45 | 76.17 |

| YOLOv3tiny | 17.0 | 80.6 | 20.9 | 68.6 | 78.4 |

| YOLOv5n | 5.0 | 98.0 | 69.4 | 98.82 | 96.89 |

| YOLOv7tiny | 11.7 | 97.1 | 88.3 | 90.69 | 94.16 |

| YOLOv8n | 6.0 | 97.9 | 82 | 98.3 | 96.8 |

| TLDDM | 4.3 | 98.0 | 98.2 | 98.34 | 96.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).