1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection remains one of the most prevalent bacterial infections globally, affecting approximately 43.9% of the adult population as of 2015–2022, marking a decline from 52.6% before 1990 [

1]. This Gram-negative, spiral-shaped bacterium has evolved to survive in the harsh acidic environment of the stomach, challenging the prior assumption that the stomach was a sterile organ. Its discovery in the early 1980s revolutionized the medical understanding of gastrointestinal diseases and their underlying causes [

2].

H. pylori infection is chronic, often persisting lifelong if left untreated, and universally leads to chronic gastritis, characterized by persistent inflammation of the gastric mucosa. While frequently asymptomatic, chronic gastritis associated with

H. pylori can escalate into severe pathological conditions, including peptic ulcers, gastric adenocarcinomas, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. Globally,

H. pylori is responsible for approximately 90–95% of duodenal ulcers and 70–85% of gastric ulcers, signifying its pivotal role in peptic ulcer disease [

3,

4].

The worldwide burden of

H. pylori-associated diseases remains substantial, with nearly half of the adult population infected, equating to about 4.4 billion people. Epidemiological estimates indicate that approximately 48.6% of the global adult population harbors

H. pylori, with prevalence significantly higher in developing countries compared to industrialized nations [

1]. Notably, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region demonstrates substantial variability in

H. pylori infection rates, with prevalence among adults ranging widely from 36.8% to 94% across different countries and localities. In Saudi Arabia specifically, regional differences are particularly pronounced, with estimates ranging dramatically from 10.2% to 96%, reflecting substantial variations in socioeconomic factors, hygiene practices, and public health awareness [

5,

6,

7]

Aside from its established connection with gastrointestinal pathology,

H. pylori infection is associated with increased risks for extra gastroduodenal diseases, including hematological, autoimmune, metabolic, cardiovascular, neurological, and allergic disorders [

8]. Notably,

H. pylori-related chronic gastritis is recognized as a precursor lesion in Correa’s cascade, progressing through atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and ultimately gastric adenocarcinoma—a malignancy responsible for significant global morbidity and mortality [

9]. Indeed, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified

H. pylori as a class I carcinogen, highlighting its critical significance in gastric oncogenesis [

10,

11]. The mechanisms underlying these associations often involve systemic inflammation and immune dysregulation triggered by

H. pylori. Autoimmune diseases, in particular, are increasingly linked to this bacterium due to mechanisms like molecular mimicry and the induction of autoantibody production. Notably, approximately 43% of autoimmune patients reportedly have concurrent

H. pylori infection.

Given the extensive health burden associated with

H. pylori, accurate and timely diagnosis remains critical. Diagnostic methodologies span non-invasive approaches, such as urea breath tests, stool antigen tests, and serology, as well as invasive techniques involving histological examination, culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of biopsy specimens. Innovations in diagnostic imaging, including Blue Laser Imaging (BLI), Linked Color Imaging (LCI), and the application of artificial intelligence (AI), have significantly enhanced diagnostic accuracy, enabling early detection and targeted therapeutic interventions [

12,

13]. Treatment strategies typically involve combination therapies consisting of antibiotics and proton-pump inhibitors to enhance efficacy. However, growing resistance to commonly used antibiotics has complicated treatment regimens, necessitating tailored therapeutic strategies based on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Considering the high prevalence and significant clinical impact of

H. pylori infection globally and particularly within the MENA region, there remains a substantial gap in public awareness and understanding of this bacterium and its associated health risks.

The current study aims to investigate the epidemiology, clinical presentations, and histopathological features associated with H. pylori infection in a regional context, elucidating factors influencing the infection's prevalence and severity. By thoroughly exploring the relationship between H. pylori infection, gastrointestinal and extragastric diseases, and assessing diagnostic efficacy, this research contributes valuable insights toward refining clinical management strategies, mitigating disease progression, and ultimately reducing associated morbidity and mortality. The findings from this research could provide crucial guidance for public health policy-makers and healthcare practitioners, particularly in regions with high infection prevalence, enabling more effective interventions and resource allocation to combat H. pylori-related diseases globally.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was retrospective cross-sectional conducted between Dec 2023 and March 2025 at the King Salman Specialist Hospital, Ha’il, Saudi Arabia. The King Salman Specialist hospital (KSSH) is certified and accredited by the Saudi Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutions (CBAHI)-Ref.no. HAL/MOH/HO5/34213 and along with the Ha’il Health Regional Laboratory (HHRL) which is also certified and accredited by the CBAHI)-Code 2739 constitutes a major cluster for healthcare diagnostic centers that receive samples for testing. We have enrolled records of 805 patients (329 males and 476 females) who presented with symptoms suggestive of upper gastrointestinal (GI) disorders. The age range extended from 20 to 80 years, and participants were recruited consecutively from the outpatient endoscopy unit or who have stayed for a day or less to avoid hospital associated infections. Each patient provided written informed consent (blank attached), and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Approval No. Log 2024-120, Dec 2024, and University of Ha’il REC -H-2024-941), dated REC 4112024). Ethical procedures followed the guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring the protection of participant rights and confidentiality.

Upon enrollment, patients underwent a standardized clinical evaluation, including demographic data collection and a physical examination. Endoscopic investigations were performed by experienced gastroenterologists, who obtained gastric biopsy samples from the antrum and body regions to assess H. pylori infection and to evaluate histopathological changes. All biopsy specimens were promptly fixed in a 37–40% commercial formaldehyde solution (formalin), processed using conventional histological protocols, and embedded in paraffin. Tissue blocks were sectioned at 3–5 µm thickness on a rotary microtome, mounted on glass slides, deparaffinized with an organic solvent, and rehydrated in a graded series of alcohol baths.

For routine histopathological examination, Harris’ hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) was employed. The H&E staining procedure involved applying hematoxylin (combined with a metallic mordant), differentiation in a weak acid solution, and subsequent bluing in an alkaline medium, followed by counterstaining with eosin. To detect H. pylori, Giemsa staining was utilized, preparing a working solution by mixing 40 ml of Giemsa stock (4 g Giemsa powder dissolved in 250 ml glycerol and 250 ml methanol) with 60 ml of distilled water. Stained slides were independently reviewed by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist, who confirmed H. pylori only when distinctive comma- or S-shaped bacilli (approximately 2–4 μm in length and 0.5–1 μm in thickness) were identified on the mucosal surface or round pleomorphic cells within the mucus layer, typically forming small colonies. Cases with isolated or morphologically ambiguous organisms were classified as negative. Histological inflammation was graded based on the number and distribution of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) in the lamina propria. Moderate or severe inflammatory activity was defined by widespread PMN infiltration—often invading the glandular epithelium or forming microabscesses—whereas mild activity indicated a focal or limited presence of PMNs.

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS (version 23, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Continuous variables were summarized as means (± standard deviation) or medians (with interquartile ranges), while categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages. The association between H. pylori infection, demographic factors, and histopathological findings was examined using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated where appropriate. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was deemed statistically significant. This approach enabled a comprehensive evaluation of H. pylori prevalence, its relationship to patient characteristics, and its impact on gastric histopathology.

3. Results

Prevalence of H. pylori Infection

A total of 805 patients were included in this study, comprising 329 males (40.9%) and 476 females (59.1%). The prevalence of

Helicobacter pylori infection was significantly high across all age groups. Among males aged 20–39 years, 209 (87.1%) tested positive for

H. pylori, increasing to 81 (94.2%) in the 40–59 age group and reaching 3 (100.0%) in the 60–80 age group. Similarly, among females aged 20–39 years, 329 (91.9%) were infected, while in the 40–59 age group, 105 (89.0%) tested positive. No cases of

H. pylori infection were recorded in females aged 60–80 years (

Table 1).

Chronic Gastrointestinal Conditions

Regarding chronic gastrointestinal conditions, nearly all patients exhibited some form of complication, with 726 (99.9%) diagnosed with at least one chronic gastrointestinal condition, leaving only 1 (0.1%) patient without any recorded complications. Lymphoma was observed in a single case (0.1%), while metaplasia was identified in 6 (0.8%) patients. Chronic gastritis, a common condition associated with

H. pylori infection, was detected in 140 (19.3%) cases (

Table 1).

Other pathological findings included gastric atrophy in 2 (0.3%) cases, gastric lipomas in 6 (0.8%) cases, and gastric polyps in 5 (0.7%) cases (

Table 1). These findings indicate that while

H. pylori infection is prevalent, progression to more severe conditions such as lymphoma and metaplasia remains relatively rare.

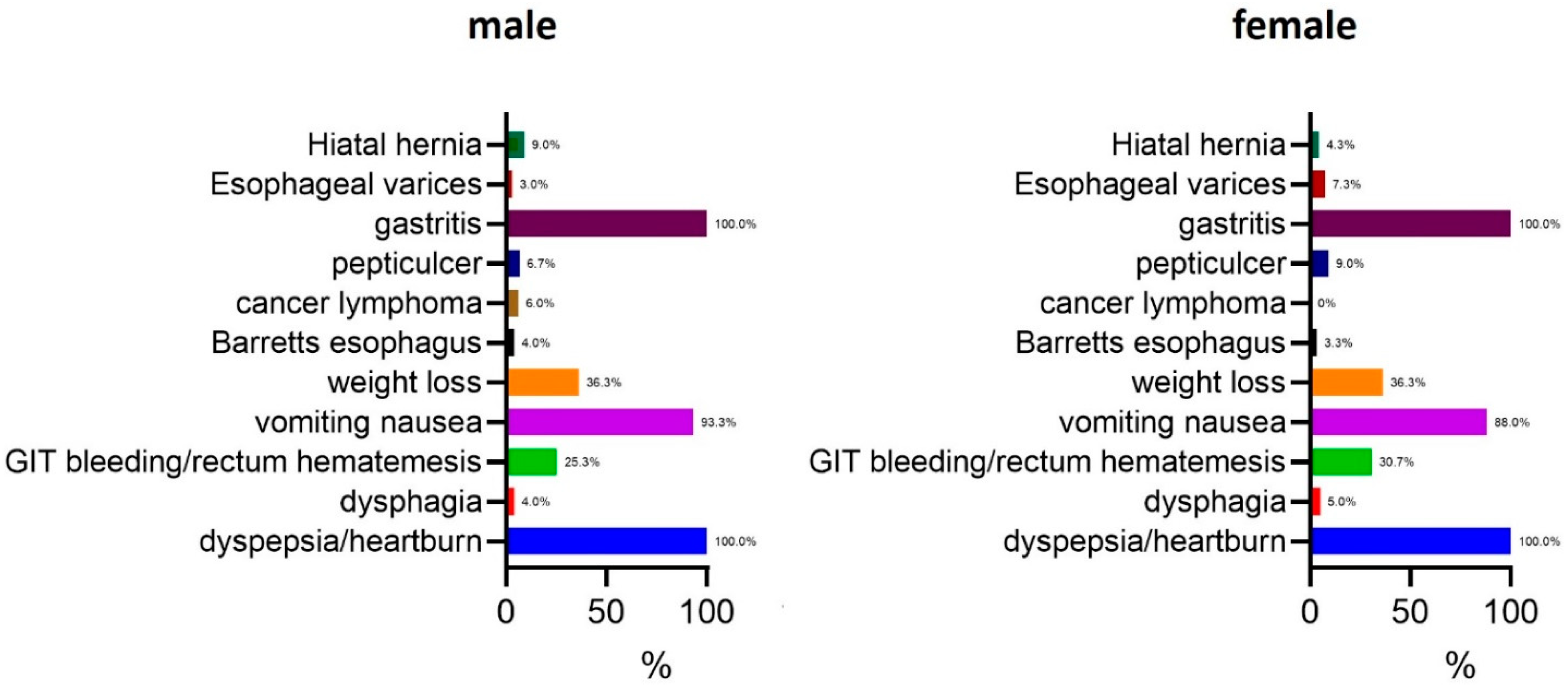

Symptoms Associated with H. pylori Infection

The most prevalent symptom in both genders was gastritis, affecting 100.0% of the participants. Dyspepsia and heartburn were also universally reported in both males and females (100.0%). Other common symptoms included vomiting and nausea, which were present in 93.3% of males and 88.0% of females. Weight loss was equally prevalent in both genders, reported in 36.3% of cases. Gastrointestinal (GIT) bleeding or rectum hematemesis was more frequently observed in females (30.7%) compared to males (25.3%). Peptic ulcers were identified in 6.7% of males and 9.0% of females, while esophageal varices were slightly more common in females (7.3%) than in males (3.0%). Cancer lymphoma was observed in 6.0% of males and 9.0% of females, whereas Barrett’s esophagus was detected in 4.0% of males and 3.3% of females. Hiatal hernia was the least frequently reported symptom, occurring in 9.0% of males and 4.3% of females. Dysphagia was present in 4.0% of males and 5.0% of females (

Figure 1).

Overall, these findings suggest that while gastritis and dyspepsia are universally present in H. pylori-infected individuals, gender-based differences exist in the prevalence of certain gastrointestinal complications.

Histopathological Findings

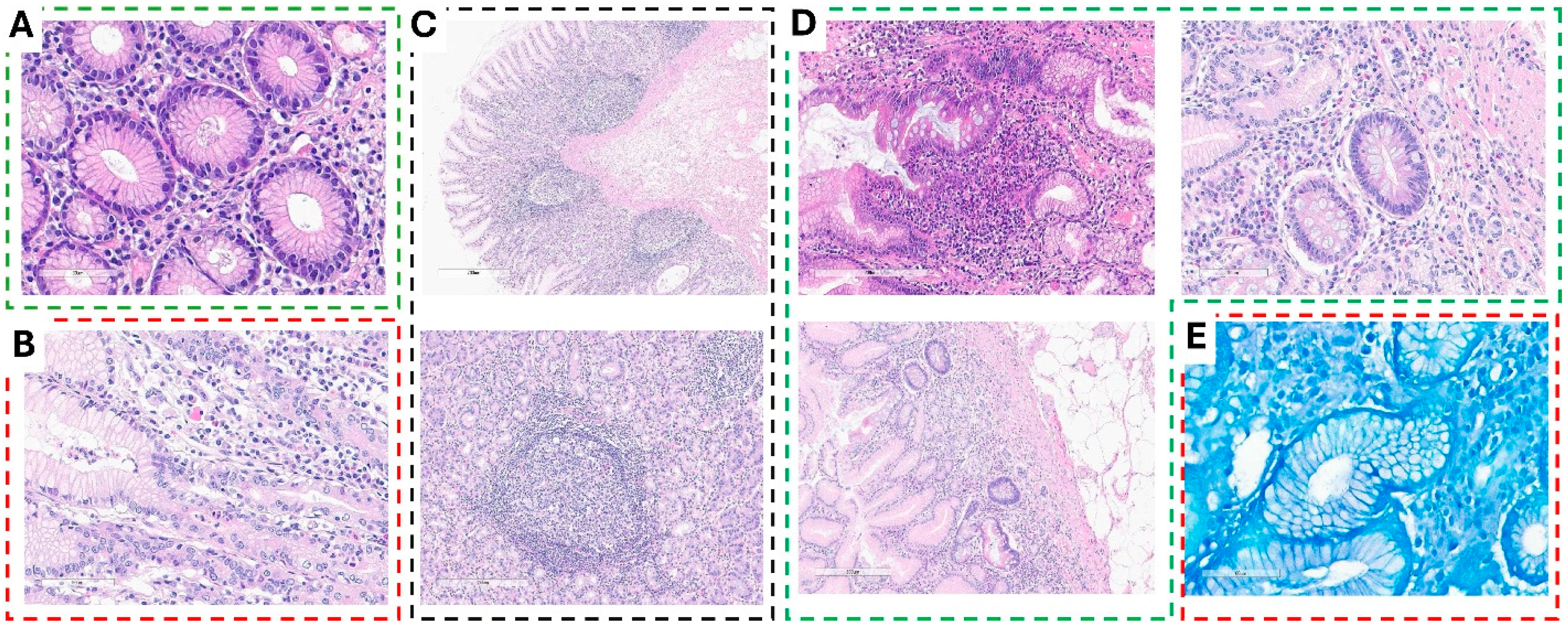

Histopathological analysis of gastric biopsies revealed varying degrees of inflammation and structural changes associated with Helicobacter pylori infection.

Chronic inflammation with moderate to marked inflammatory infiltrate was evident in multiple biopsy specimens. H&E staining of the gastric mucosa demonstrated normal glandular architecture lined with intact epithelium. However, the lamina propria exhibited moderate to marked infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells, predominantly lymphocytes and plasma cells, indicative of chronic inflammation (

Figure 2A). In cases of chronic active gastritis with potential

H. pylori infection, biopsies showed glandular distortion along with foveolar epithelial irregularities. The lamina propria was densely infiltrated with a mixed inflammatory cell population, primarily lymphocytes and plasma cells, accompanied by scattered neutrophils, confirming active inflammation. Notably, small, curved, or spiral-shaped organisms were observed on the mucosal surface, suggesting the presence of

H. pylori (

Figure 2B).

Sections of chronic active gastritis with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, frequently associated with

H. pylori infection, demonstrated an intact foveolar epithelium with no significant erosion or ulceration. Mild architectural distortion of the gastric glands was observed, along with a dense inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria. Additionally, neutrophilic infiltration signified active inflammation. Prominent lymphoid aggregates with well-formed germinal centers were present within the lamina propria and submucosa, confirming reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (

Figure 2C). In more severe cases, chronic active gastritis with glandular distortion and surface erosion, suggestive of

H. pylori-associated gastritis, was identified. These biopsies exhibited significant glandular architectural distortion, along with signs of glandular atrophy. The surface epithelium displayed erosion and damage, accompanied by features of intestinal metaplasia and reactive epithelial alterations such as nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia. A dense inflammatory infiltrate populated the lamina propria, reinforcing the diagnosis of chronic active gastritis with surface damage (

Figure 2D). Confirming the presence of

H. pylori, Giemsa-stained gastric biopsies revealed numerous pleomorphic, curved, spiral-shaped microorganisms adhering to the surface epithelium and within the mucosal layer, further supporting the diagnosis of

H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis with abundant bacterial colonization (

Figure 2E).

These findings highlight the spectrum of histopathological alterations observed in H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa, ranging from chronic inflammation to architectural distortion and bacterial colonization.

Statistical Analysis of Gastrointestinal Complications

Gastrointestinal complications were highly prevalent among

H. pylori-infected individuals, with 770 (95.7%) of cases reporting at least one complication. No significant correlation was observed between gender and the likelihood of developing gastrointestinal complications (OR = 0.963; 95% CI: 0.482–1.922) (

Supplementary Table S1).

Lymphoid aggregates, a key histopathological feature of

H. pylori-induced gastritis, were present in 749 (93.0%) of cases, but their occurrence did not significantly differ between males and females (OR = 1.276; 95% CI: 0.740–2.200) (Supplementary ). Similarly, lymphoma was detected in only one patient (0.1%), making statistical comparisons unreliable (

Supplementary Table S3).

Metaplasia, a potential precursor to gastric malignancy, was observed in 6 (0.8%) of cases, with no significant gender-based risk difference (OR = 0.343; 95% CI: 0.062–1.883) (

Supplementary Table S4). Chronic gastritis was diagnosed in 140 (19.3%) of participants, but no significant gender correlation was found (OR = 0.888; 95% CI: 0.615–1.282) (

Table 2).

Acute gastritis was diagnosed in 19 (2.4%) of cases, again without any notable gender difference (OR = 0.949; 95% CI: 0.378–2.386) (

Supplementary Table S5). Atrophy, a histological marker of gastric mucosal damage, was found in only 2 (0.3%) of participants, with no statistically significant correlation to gender (OR = 0.691; 95% CI: 0.043–11.079) (

Supplementary Table S6).

The overall prevalence of

H. pylori infection in the study population was 727 (90.3%), with a slightly higher infection rate in females (91.2%) compared to males (89.0%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (OR = 1.270; 95% CI: 0.794–2.030) (

Table 3).

Gastric lipomas were identified in 6 (0.8%) of cases, with no significant gender association (OR = 1.386; 95% CI: 0.252–7.609) (

Supplementary Table S7). Similarly, gastric polyps were detected in 5 (0.7%) of patients, with no significant gender correlation (OR = 2.780; 95% CI: 0.309–24.982) (

Supplementary Table S8).

Overall, while H. pylori infection was widespread and associated with a high prevalence of chronic gastritis, most advanced gastrointestinal pathologies, including metaplasia, atrophy, lymphoma, and gastric tumors, remained rare with no significant gender-based differences.

4. Discussion

This study provides meaningful perspectives on the multifaceted epidemiology, clinical features, and histopathological effects of H. pylori. By interpreting our findings through the lens of established literature, we can better appreciate how these results inform both clinical care and broader public health efforts. Our observations, which align with numerous PubMed-indexed investigations, underscore H. pylori’s global importance and the considerable burden it imposes in terms of disease severity and mortality.

One of the most prominent observations is the considerable prevalence of

H. pylori across various age categories in our cohort. Among men aged 20–39 years, 87.1% tested positive, rising to 94.2% in the 40–59 bracket, and reaching 100.0% for those aged 60–80—although the older group had relatively few participants. Women aged 20–59 showed infection rates between 89.0% and 91.9%, whereas none tested positive beyond 60 years in our study population. This level and increase with age are typical of

H.pylori prevalence in developing countries [

14]. Saudi Arabia has become an economic hub attracting jobseekers from diverse countries and becoming one of the most desired destinations globally and in the region. It is consistent with known factors for contracting the organism including consumption of restaurant food, meat, nonfiltered water, and smoking habit mostly among youth in the region. However, its positivity in youth through old age is a trend largely consistent with past epidemiological reports indicating that

H. pylori is often acquired during childhood and can persist remaining dormant intracellular into later stages of life [

15]. Nevertheless, the lack of cases in older women may point to localized demographic patterns, health-seeking habits in this subgroup, or the most reasonable possibility of smaller sample sizes in that age range.

On the clinical front, we noted that nearly every individual in our study experienced gastritis, dyspepsia, and heartburn. This widespread occurrence highlights the central role of

H. pylori in upper gastrointestinal disorders [

16]. Chronic inflammation triggered by

H. pylori may also explain the frequency of coexisting symptoms such as vomiting, nausea, and, in some cases, gastrointestinal bleeding or hematemesis. Previous investigations have demonstrated how enduring inflammation can encourage disease progression if left unchecked [

17]. We also detected autoimmune-like complications, aligning with existing literature that points to immunomodulatory processes driven by

H. pylori in certain extragastric diseases.

Histologically, 19.3% of our patients showed evidence of chronic gastritis, while 2.4% had acute gastritis, reinforcing H. pylori as a primary source of sustained gastric mucosal inflammation. Nearly all examined cases (93.0%) displayed lymphoid aggregates, which are recognized as a hallmark of H. pylori-associated gastritis. Although MALT lymphoma is rare, we found one individual (0.1%) with this condition, illustrating the possibility that malignant transformations can arise in a small fraction of cases.

Interestingly, our results indicated that advanced pathologies, such as metaplasia (0.8%), atrophy (0.3%), and malignancy, were not widespread. Even so, identifying these changes in any subset of patients underscores the organism’s carcinogenic capability, consistent with

H. pylori’s designation by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a class I carcinogen. It is essential to emphasize that chronic infection can move through Correa’s sequence, transitioning from chronic gastritis to atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and eventually gastric adenocarcinoma [

18]. Early detection and prompt treatment thus remain pivotal to curbing the risk of more advanced disease.

Overall, 90.3% of our study population tested positive for

H. pylori, a figure comparable to findings from other developing regions where prevalence may approach or exceed 80%. However, the organism’s prevalence was linked more to the impact of diet [

19], where mostly food, dairy, and veterinary products are prone to transmit [

20]. Nonetheless, differences between age brackets in our data might stem from regional economic conditions, healthcare availability, hygiene standards, socioeconomic status, and cultural norms involving antibiotic practices, particularly in the widely practiced traditional dairy and veterinary farm products. Earlier research has indicated that crowding and poor sanitation in low-income settings can facilitate both family and community-level spread [

21]. Meanwhile, countries with improved public health infrastructure have documented decreasing

H. pylori infection rates over the past few decades, reflecting the positive impact of better living conditions and broader antibiotic use. Nonetheless, the high rates of food and labor imports in markets are likely to have significant impact in foodborne zoonotic pathogen transmission dynamics.

Our finding of considerable chronic gastritis cases underscores the pressing need for effective

H. pylori eradication strategies. As documented in previous research, embracing a test-and-treat model can substantially lower the incidence of peptic ulcers and related complications [

22]. Achieving this outcome, however, requires patient compliance, clinicians following best-practice guidelines, and continual assessment of local resistance dynamics. In places where antibiotic resistance is escalating, quadruple regimens with bismuth, or second-line agents like tetracycline, levofloxacin, or rifabutin, may be justified if susceptibility data support their use. Regardless of the specific medication combination, proton pump inhibitors are an essential component because they elevate gastric pH, thereby boosting the effectiveness of antimicrobial agents.

We noted no statistically significant sex-based differences regarding major

H. pylori complications such as metaplasia, atrophy, or lymphoma, although women had a slightly higher infection rate (91.2% vs. 89.0%) and a modestly greater incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding and esophageal varices. These findings contrast with some epidemiological datasets suggesting that men might be more prone to duodenal ulcers and gastric cancer [

23,

24]. Geographic elements, population attributes, or genetic factors may account for these inconsistencies. Our results indicate that, irrespective of gender, early identification and timely intervention are crucial to managing

H. pylori-related disease effectively.

Histopathologic evaluation of infected gastric mucosa revealed an active inflammatory profile with infiltration by neutrophils and mononuclear cells. Lymphoid aggregates, indicative of

H. pylori’s immunostimulatory activity, were abundant. MALT lymphoma was present in only one patient—while uncommon, it is recognized to regress after

H. pylori eradication. Although we encountered minimal advanced precancerous transformations, any trace of atrophy or metaplasia in these samples underscores the need to track patients who may be at heightened risk over time. According to Correa’s model, further histopathological changes, such as incomplete intestinal metaplasia, significantly increase the likelihood of developing gastric adenocarcinoma [

25].

A number of investigations spanning Asia, Africa, and Latin America have demonstrated

H. pylori’s pivotal influence on chronic gastric inflammation and the risk of peptic ulcers [

26,

27]. Notably, stronger public health infrastructure in some countries has been linked with falling

H. pylori prevalence. Our findings—featuring widespread infection rates across key demographic segments—mirror similar data from the Middle East and North Africa, where hygiene factors, local customs, and transmission within households are crucial in shaping infection patterns.

Also noteworthy is that the comparatively slightly lower incidence of advanced lesions in our sample parallels observations from other areas of the developing world. High

H. pylori prevalence does not always equate to a proportional escalation in malignancies. Variables such as genetic predisposition [

28], bacterial virulence genes (for instance, cagA and vacA), and local dietary habits [

21,

29] modulate the trajectory from infection to severe disease. Comparative studies in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe highlight differences in clinical outcomes, even among populations with similar infection levels, alerting the multifactorial nature of disease progression by

H. pylori [

30]. Furthermore, role of

H. pylori in many chronic disorders is not yet well studied; for instance, it has been found as an independent risk for thyroid nodules in adults. These findings highlight the critically important aspect of this organism’s eradication, not only for internal disorders but also for its role in other debilitating diseases such as Grave's and Hashimoto's thyroiditis [

31]. For the low iodine in drinking waters and the well-known genetic predispositions in the region, it is plausible to suggest

H. pylori as a risk for multi-syndromic sequalae of disorders.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study reaffirms H. pylori’s widespread prevalence in our region and reveals the spectrum of clinical and histopathological outcomes. Although most patients did not progress to advanced conditions, the presence of even a small fraction of malignant or near-malignant cases emphasizes the importance of monitoring. These findings resonate with global data while offering specific insights into local risk profiles, including gender distribution and symptom patterns. They also underscore how lymphoid aggregates might point to possible lymphoproliferative processes. When integrated with the wealth of PubMed-indexed studies, these insights are poised to refine clinical guidelines, optimize patient care, and move us closer to significantly reducing the worldwide impact of H. pylori.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. The supplementary tables (1-8) indicated in the text (Results) are enclosed uploaded herewith this manuscript.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used Conceptualization, Kamaleldin B Said; Data curation, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Safia Moussa, Ruba Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Najd Albalawi, Layan Al-Hujaili , Ruaa Alharbi, Arwa Alotaibi, Fahad Alshammary, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Bader Alkharisi, Ghadah. Alsdairi and Shumukh Alshubrami ; Formal analysis, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Safia Moussa, Ruba Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Najd Albalawi, Layan Al-Hujaili , Ruaa Alharbi, Arwa Alotaibi, Fahad Alshammary, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Bader Alkharisi, Ghadah. Alsdairi and Shumukh Alshubrami ; Funding acquisition, Kamaleldin B Said; Investigation, Kamaleldin B Said; Methodology, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Safia Moussa, Ruba Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Najd Albalawi, Layan Al-Hujaili , Ruaa Alharbi, Arwa Alotaibi, Fahad Alshammary, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Bader Alkharisi, Ghadah. Alsdairi and Shumukh Alshubrami ; Project administration, Kamaleldin B Said; Resources, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Safia Moussa, Ruba Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Najd Albalawi, Layan Al-Hujaili , Ruaa Alharbi, Arwa Alotaibi, Fahad Alshammary, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Bader Alkharisi, Ghadah. Alsdairi and Shumukh Alshubrami ; Software, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Safia Moussa, Ruba Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Najd Albalawi, Layan Al-Hujaili , Ruaa Alharbi, Arwa Alotaibi, Fahad Alshammary, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Bader Alkharisi, Ghadah. Alsdairi and Shumukh Alshubrami ; Supervision, Kamaleldin B Said; Validation, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Safia Moussa, Ruba Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Najd Albalawi, Layan Al-Hujaili , Ruaa Alharbi, Arwa Alotaibi, Fahad Alshammary, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Bader Alkharisi, Ghadah. Alsdairi and Shumukh Alshubrami ; Visualization, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Safia Moussa, Ruba Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Najd Albalawi, Layan Al-Hujaili , Ruaa Alharbi, Arwa Alotaibi, Fahad Alshammary, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Bader Alkharisi, Ghadah. Alsdairi and Shumukh Alshubrami ; Writing – original draft, Kamaleldin B Said; Writing – review & editing, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Safia Moussa, Ruba Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Najd Albalawi, Layan Al-Hujaili , Ruaa Alharbi, Arwa Alotaibi, Fahad Alshammary, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Bader Alkharisi, Ghadah. Alsdairi and Shumukh Alshubrami.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Ethical Committee (REC) of University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia, has Approved this research by the number (H-2024-941), dated REC 4112024. In addition, IRB Approval (Log 2024-120, Dec 2024) was obtained from Ha’il Health Cluster, Ha’il to perform this work.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. A blank copy attached herewith this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the University of Ha’il’s Deanship for research, REC, and clinics for their support throughout this work. As native English speakers, some of authors have thoroughly proofread this manuscript for clarity and accuracy. No AI-generated content was used in drafting or revising, All scientific content, data interpretation, and conclusions are solely the authors’ work.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Chen YC, Malfertheiner P, Yu HT, Kuo CL, Chang YY, Meng FT, et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection and Incidence of Gastric Cancer Between 1980 and 2022. Gastroenterology. 2024;166(4):605-19. [CrossRef]

- Malfertheiner P, Camargo MC, El-Omar E, Liou JM, Peek R, Schulz C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):19.

- Carrasco G, Corvalan AH. Helicobacter pylori-Induced Chronic Gastritis and Assessing Risks for Gastric Cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:393015. [CrossRef]

- Schöttker B, Adamu MA, Weck MN, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori infection is strongly associated with gastric and duodenal ulcers in a large prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(5):487-93.e1. [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel BN, Peter DA, Peter MO, Adedayo IS, Olaifa K. Helicobacter pylori infection in Africa: comprehensive insight into its pathogenesis, management, and future perspectives. Journal of UmmAl-Qura University for Applied Sciences. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim ME. Epidemiology, pathogenicity, risk factors, and management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Saudi Arabia. Biomol Biomed. 2024;24(3):440-53. [CrossRef]

- Alsulaimany FAS, Awan ZA, Almohamady AM, Koumu MI, Yaghmoor BE, Elhady SS, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection and Diagnostic Methods in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(4). [CrossRef]

- Gravina AG, Priadko K, Ciamarra P, Granata L, Facchiano A, Miranda A, et al. Extra-Gastric Manifestations of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Journal of Clinical Medicine [Internet]. 2020; 9(12). [CrossRef]

- Pellicano R, Ianiro G, Fagoonee S, Settanni CR, Gasbarrini A. Review: Extragastric diseases and Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2020;25 Suppl 1:e12741. [CrossRef]

- Schistosomes I. liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC working group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1-241.

- Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ. Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease E-book: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management: Elsevier health sciences; 2020.

- Costa LCMC, das Graças Carvalho M, La Guárdia Custódio Pereira AC, Teixeira Neto RG, Andrade Figueiredo LC, Barros-Pinheiro M. Diagnostic Methods for Helicobacter pylori. Medical Principles and Practice. 2024;33(3):173-84. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima H, Kawahira H, Kawachi H, Sakaki N. Artificial intelligence diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection using blue laser imaging-bright and linked color imaging: a single-center prospective study. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31(4):462-8.

- Woodward M, Morrison C, McColl K. An investigation into factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000 Feb;53(2):175-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang Y-J, Yang H-B, Wu J-J, Sheu B-S. Persistent H. pylori colonization in early acquisition age of mice related with higher gastric sialylated Lewis x, IL-10, but lower interferon-γ expressions. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2008;16(1):34.

- Moayyedi P, Forman D, Braunholtz D, Feltbower R, Crocombe W, Liptrott M, et al. The proportion of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the community associated with Helicobacter pylori, lifestyle factors, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Leeds HELP Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(6):1448-55.

- Loosen SH, Mertens A, Klein I, Leyh C, Krieg S, Kandler J, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori and its eradication and the development of cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2024;11(1).

- Toh JWT, Wilson RB. Pathways of Gastric Carcinogenesis, Helicobacter pylori Virulence and Interactions with Antioxidant Systems, Vitamin C and Phytochemicals. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(17).

- He, S., He, X., Duan, Y. et al. The impact of diet, exercise, and sleep on Helicobacter pylori infection with different occupations: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 24, 692 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Elhariri, M., Hamza, D., Elhelw, R. et al. Occurrence of cagA+ vacA s1a m1 i1 Helicobacter pylori in farm animals in Egypt and ability to survive in experimentally contaminated UHT milk. Sci Rep 8, 14260 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Amaral O, Fernandes I, Veiga N, Pereira C, Chaves C, Nelas P, et al. Living Conditions and Helicobacter pylori in Adults. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:9082716. [CrossRef]

- Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Helicobacter Pylori "Test-and-Treat" Strategy for Management of Dyspepsia: A Comprehensive Review. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2013;4(3):e32. [CrossRef]

- Luan X, Niu P, Wang W, Zhao L, Zhang X, Zhao D, et al. Sex Disparity in Patients with Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Oncol. 2022;2022:1269435. [CrossRef]

- Arakawa H, Komatsu S, Kamiya H, Nishibeppu K, Ohashi T, Konishi H, et al. Differences of clinical features and outcomes between male and female elderly patients in gastric cancer. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):17192. [CrossRef]

- Jencks DS, Adam JD, Borum ML, Koh JM, Stephen S, Doman DB. Overview of Current Concepts in Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia and Gastric Cancer. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2018;14(2):92-101.

- Graham DY, Lu H, Yamaoka Y. African, Asian or Indian enigma, the East Asian Helicobacter pylori: facts or medical myths. J Dig Dis. 2009;10(2):77-84.

- Bustos-Fraga S, Salinas-Pinta M, Vicuña-Almeida Y, de Oliveira RB, Baldeón-Rojas L. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori genotypes: cagA, vacA (m1), vacA (s1), babA2, dupA, iceA1, oipA and their association with gastrointestinal diseases. A cross-sectional study in Quito-Ecuador. BMC Gastroenterology. 2023;23(1):197. [CrossRef]

- Datta De D, Roychoudhury S. To be or not to be: The host genetic factor and beyond in Helicobacter pylori mediated gastro-duodenal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(10):2883-95.

- Roesler BM, Rabelo-Gonçalves EM, Zeitune JM. Virulence Factors of Helicobacter pylori: A Review. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol. 2014;7:9-17. [CrossRef]

- Cavadas B, Leite M, Pedro N, Magalhães AC, Melo J, Correia M, et al. Shedding Light on the African Enigma: In Vitro Testing of Homo sapiens-Helicobacter pylori Coevolution. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2021; 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Di J, Ge Z, Xie Q, Kong D, Liu S, Wang P, Li J, Ning N, Qu W, Guo R, Chang D, Zhang J, Zheng XH. Helicobacter pylori infection increases the risk of thyroid nodules in adults of Northwest China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023 Mar 31;13:1134520. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).