1. Introduction

Reforestation is increasingly recognized as a key nature-based solution for mitigating climate change, as it sequesters carbon, restores ecosystems, and enhances biodiversity [

1]. Global efforts to scale up reforestation initiatives are accelerating, particularly in tropical regions such as Brazil, where vast carbon sequestration potential exists [

2]. These projects are often integrated into voluntary carbon markets, where companies and governments invest in afforestation and reforestation as a means to offset their emissions. However, while reforestation contributes to climate change mitigation, it may also trigger unintended consequences, notably deforestation leakage, i.e. the displacement of agricultural activities to other areas, leading to new deforestation elsewhere [

3]. Thus, the efforts to increase carbon sequestration in one place may cause increased carbon emissions in another place. This phenomenon challenges the net climate benefits of reforestation and raises fundamental questions about the effectiveness of carbon market-based reforestation strategies.

Deforestation leakage has been widely studied in the context of REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) programs, where conservation initiatives may push land-use pressures into unprotected areas [

4]. However, there is limited empirical evidence on whether reforestation projects - aimed at expanding forest cover for commercial forestry or ecological restoration - lead to similar displacement effects. Unlike REDD+, which primarily targets standing forests, reforestation projects repurpose land previously used for agriculture, thereby introducing direct land-use competition with farming and livestock activities [

5]. This fundamental difference suggests that distinct mechanisms may drive leakage effects from reforestation and require further studies.

The land spillovers caused by large-scale reforestation, e.g. deforestation leakage, remains an open debate. One hypothesis suggests that livestock intensification, i.e. a process of increasing productivity per hectare, could mitigate leakage by reducing the total land required for agricultural production [

6]. Proponents argue that if farmers increase stocking rates and improve pasture management, they can maintain or even enhance output without expanding into new forested areas. However, others contend that intensification can induce a rebound effect, whereby higher productivity and profitability incentivize further agricultural expansion, exacerbating deforestation elsewhere [

7,

8]. Understanding whether intensification serves as a leakage mitigation strategy or an unintended accelerator of land displacement is critical for designing effective reforestation policies. Similarly, strategies to reduce competition with agriculture and livestock activities include land use planning, by prioritizing reforestation in degraded and low-productivity areas [

9].

In this study, we provide the empirical quantification of reforestation-induced deforestation leakage in Brazilian Amazon, where large-scale reforestation efforts are underway as part of global carbon offset initiatives. We specifically examine: (i) the magnitude of leakage, estimating how much deforestation is displaced due to reforestation projects; (ii) the spatial extent of leakage, i.e. does agricultural displacement occur locally, or does it propagate across distant regions? And (iii) if livestock intensification can offset the land-use pressure created by reforestation. Since the fundamental mechanism driving leakage is agricultural displacement, we use forest plantation land cover as a proxy to estimate reforestation-induced spillovers. Therefore, in this study, we use the terms "reforestation" and "forest plantation" interchangeably to refer to the conversion of agricultural land into tree-based cover, whether for ecological restoration or commercial forestry. Our analysis disregard natural regeneration processes and focuses on the displacement effects of reducing agricultural land to planted forests. Using a spatial Durbin panel model (SDM), we analyze land spillovers caused by forest plantation across multiple years and municipalities. By providing a robust, data-driven assessment of deforestation leakage caused by forest plantation, this study bridges a critical knowledge gap and offers actionable insights for policymakers, land managers, and carbon market stakeholders. In doing so, it contributes to the broader discussion on how to design reforestation projects that maximize carbon sequestration without inadvertently shifting environmental burdens elsewhere.

Our results indicate that deforestation leakage effects are nontrivial and extend in the immediate vicinity of reforested areas, raising concerns about the net climate benefits of reforestation projects under carbon market schemes. Still, the leakage seems to be effective in the short term, up to two years. Moreover, we find that livestock intensification exhibits mixed effects, suggesting that while productivity gains can mitigate land expansion pressure, they do not fully neutralize leakage. These findings hold direct implications for carbon credit standards, such as Verra and ART-TREES, which currently employ simplified or incomplete methodologies for leakage assessment [

10]. We argue that carbon markets must incorporate more rigorous spatial analysis into their verification processes to avoid overestimating the net sequestration potential of reforestation projects.

2. Background

2.1. Agricultural Displacement and Deforestation Leakage

Reforestation and afforestation are widely promoted as nature-based solutions for mitigating climate change, with global initiatives increasingly integrating them into carbon offset markets. Reforestation refers to the restoration of tree cover on land that was previously forested but has been cleared or degraded, whereas afforestation involves establishing tree cover on land that was not historically forested. While both processes contribute to increasing forest area, they differ in ecological and policy implications, particularly in carbon markets where additionality and land-use history play critical roles. This study focuses on both types under the common mechanism of reducing agricultural land for tree-based land uses – whether commercial or ecological purposed.

Reforestation strategies aim to enhance carbon sequestration, restore ecosystems, and contribute to biodiversity conservation [

11]. However, while these interventions yield environmental benefits, they can also trigger unintended land-use changes, particularly through deforestation leakage, which displaces agricultural expansion and land clearing elsewhere [

12]. Understanding the drivers and mechanisms of this process is critical to assessing the net environmental impact of reforestation programs and ensuring that climate mitigation efforts do not exacerbate land scarcity, food insecurity, or global deforestation. Structured reforestation efforts, whether for commercial forestry or ecological restoration, alter land availability and create economic incentives that may displace agricultural activities. Unlike passive regeneration or land abandonment, which may occur without direct investment, forest plantations require capital inputs, infrastructure, and land conversion decisions, all of which can amplify leakage risks.

The concept of deforestation leakage has been extensively studied in the context of REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) and agricultural land-use change. The core concern is that restricting deforestation or expanding forest cover in one location does not eliminate the underlying pressures driving land conversion. Instead, these pressures often shift spatially as land users adapt to new constraints, leading to agricultural displacement and continued deforestation elsewhere [

3,

5]. Leakage can occur through multiple mechanisms, each driven by distinct economic and ecological forces. First, the direct displacement, when reforestation projects are established on previously agricultural land, farmers and ranchers may relocate their activities, clearing new forested areas to maintain production. This is particularly relevant in regions where land-use competition is high, such as the Brazilian Amazon, where pastureland often serves as the primary expansion frontier for both crops and livestock [

13,

14]. However, the Amazon also contains vast areas of degraded, low-productivity lands that are no longer suitable for commercial agriculture or extensive cattle ranching. Estimates suggest that over 15-20 million hectares of degraded land exist in the region, with low economic returns making them unlikely candidates for future agricultural expansion [

15].

Second, market forces can mediate the agricultural displacement. For instance, large-scale reforestation may reduce available agricultural land, then increase land scarcity and raise local commodity prices (e.g. beef or calves supply), incentivizing expansion into other forested regions. This effect is often amplified in globalized markets where demand for agricultural commodities, such as soy, beef, and palm oil, drives extensive land-use change [

16,

17]. Economic modeling studies on indirect land-use change (ILUC) demonstrate that even marginal shifts in land supply can trigger widespread deforestation across different regions or countries [

18].

Third, displacement at international level ("Telecoupling" Effects). In a globalized economy, land-use changes are not confined to national borders. Reforestation policies in one country may reduce domestic agricultural production, increasing reliance on food or commodity imports. This, in turn, can drive deforestation in exporting countries that seek to meet the external demand [

19]. This phenomenon has been observed in global trade analyses, where conservation policies in one region shift land-use pressures to distant locations through international commodity markets [

20].

While these leakage pathways pose challenges to the effectiveness of reforestation policies, the extent and intensity of displacement vary depending on land-use governance, economic incentives, and agricultural productivity trends. Some studies argue that intensification strategies, such as improved livestock management or higher crop yields, can mitigate leakage effects by maintaining production on smaller land footprints [

7,

8]. However, others caution that intensification can create rebound effects, where higher productivity fuels further expansion rather than reducing total land demand [

14,

21]. This underscores the importance of integrating spatially explicit leakage assessments into reforestation initiatives, rather than relying solely on economic or sectoral averages.

2.1.1. Implications for Carbon Markets and Policy Design

The presence of leakage has significant implications for carbon market integrity. Many voluntary carbon crediting standards, such as Verra and ART-TREES, rely on simplified methodologies that may not fully account for spatial spillovers and land-use feedback loops [

22]. As a result, the net sequestration potential of reforestation projects may be overestimated, leading to inflated carbon offset claims. Several studies call for more rigorous spatial econometric approaches to better quantify leakage effects and improve the credibility of carbon finance mechanisms [

23,

24,

25].

Policy solutions to mitigate leakage include integrated land-use planning, financial incentives for sustainable intensification, and jurisdictional approaches to conservation and reforestation [

26]. Implementing land zoning regulations that strategically allocate reforestation efforts away from high-risk displacement areas could help minimize unintended expansion into sensitive biomes. Additionally, improving monitoring frameworks with high-resolution remote sensing data can enhance leakage detection and accountability in carbon offset programs [

27].

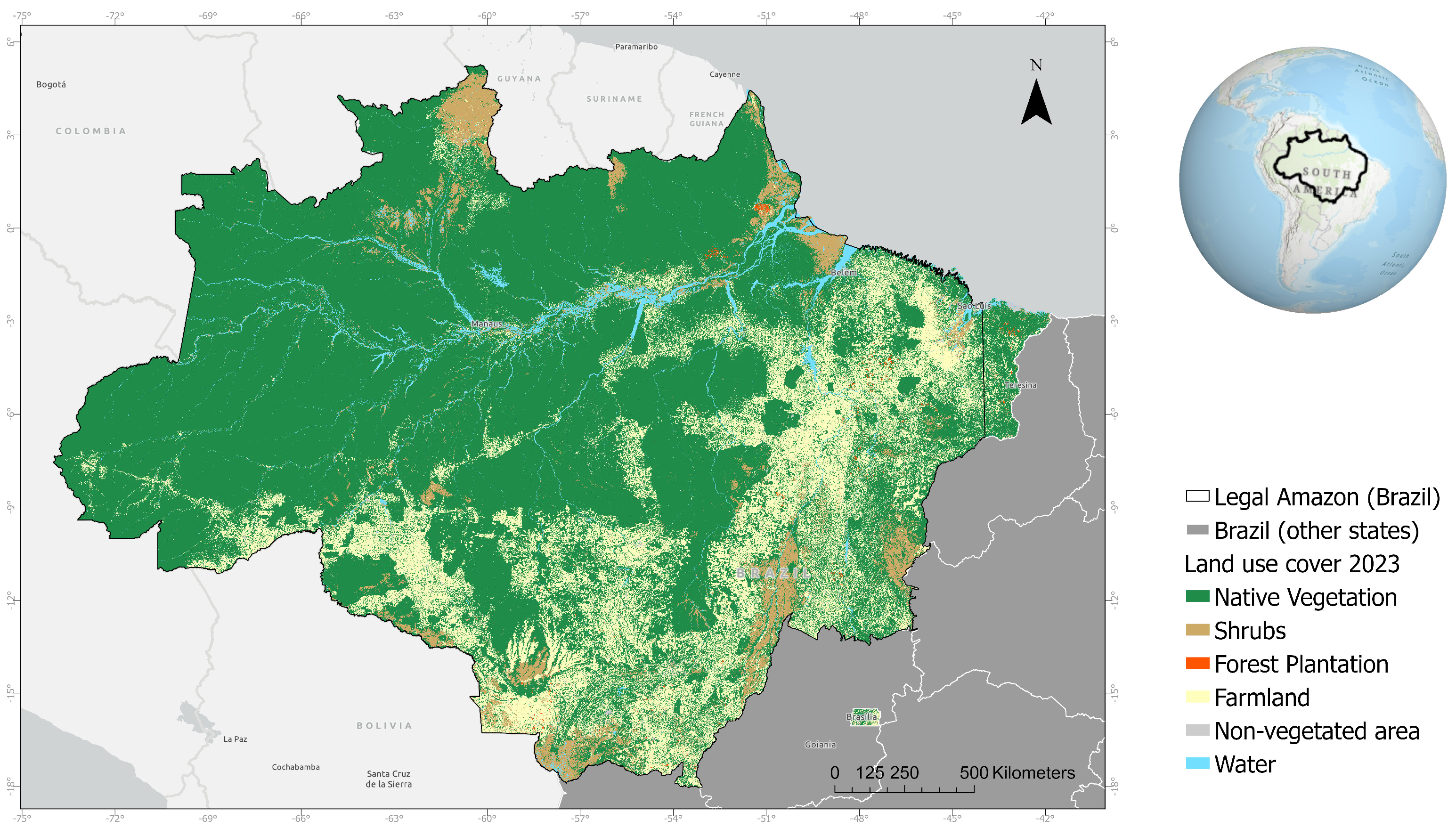

2.2. Area of study: Brazilian Amazon

The Brazilian Amazon, home to the world’s largest tropical rainforest, is a key region for both carbon sequestration and agricultural expansion. While conservation efforts have sought to curb deforestation, land-use pressures persist, particularly due to cattle ranching, which accounts for nearly 80% of deforested land [

28]. With over 60 million hectares of pastureland in the region (MapBiomas Project [

29]), any reduction in available land due to reforestation projects risks displacing ranching activities elsewhere, potentially causing deforestation leakage. Forest plantations are 630 thousand hectares within the states of the Brazilian Amazon (Fig.

Figure 1), and 8 million hectares in the other Brazilian states.

Pastureland is the dominant land-use category affected by reforestation because cattle ranching is highly mobile and responsive to land competition. Unlike mechanized agriculture, which requires specific soil and infrastructure, ranching can shift rapidly into newly cleared forested areas, making it a major driver of indirect land-use change (ILUC) [

30]. This pattern is evident in Pará, Mato Grosso, and Rondônia, which together accounted for over 70% of new deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon in 2021 [

28]. Focusing on pastureland displacement provides critical insights into the economic and spatial spillovers of reforestation policies. Given that voluntary carbon markets often overlook cattle displacement effects, understanding where and how ranching activities relocate when land is reforested is essential for ensuring the integrity of carbon offset projects and preventing unintended deforestation elsewhere [

22].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

We employed a municipality-level panel data analysis for the period of 2000-2023 to assess deforestation leakage caused by forest plantation, its geographic sensitivity, and the role of livestock intensification in mitigating spillovers. The panel data approach allowed for the estimation of both temporal persistence in deforestation and spatial spillover effects. The dataset integrates land-use, economic, climatic, and spatial data, enabling a rigorous econometric analysis of deforestation leakage and the role of livestock intensification. We included multiple independent variables to capture the drivers of vegetation loss, from proximate direct causes to underlying contextual controlling variables. This control for confounding factors, include infrastructure expansion (proxy: population density), commodity price shocks (agricultural GDP and beef price deflated), and environmental enforcement (embargoed area due to illegal deforestation). By incorporating these controls, we isolate the specific contribution of reforestation to land-use displacement while accounting for broader economic and policy influences. See summary of variables in the

Table 1.

To facilitate the interpretation of model estimators and address skewness in the data, Inverse Hyperbolic Sine (IHS) transformations are applied to the variables in the modeling, including land use (e.g., forest loss, forest plantation, pasture area), agricultural and economic indicators (e.g., livestock, GDP), population density, law enforcement, and environmental factors (e.g., temperature, rainfall). This approach ensures interpretability akin to a logarithmic transformation while accommodating zero and negative values [

31,

32,

33]. The IHS is calculated as:

3.2. Empirical Modeling Approaches

To deforestation leakage caused by forest plantation (our proxy for reforestation) and land-use change dynamics, we implement panel data regressions with spatial weights to capture the land spillovers. The variations in the dependent variable (vegetation loss) across municipalities and time are modeled using pooled OLS as a baseline, then fixed effects (FE) and first differences (FD) models. The panel structure of the dataset allows for controlling time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity at the municipal level, for instance, persistent regional characteristics such as soil quality, and institutional factors that may influence deforestation. This approach ensures that the estimated effect of reforestation on deforestation leakage is not confounded by historical land-use patterns or persistent regional characteristics. We specify the Spatial Durbin Model with panel data:

where,

is the vegetation loss rate in municipality

i at time

t, calculated as the ratio of annual vegetation loss relative to the 2000 baseline. We used the total area of native vegetation as alternative specification to first-differences panel model, which account for annual variations in native vegetation area. The

represents the municipality fixed effects, and

control for time-invariant characteristics such as topography and soil quality. Lagged

captures the persistence of deforestation over time, while

is the spatial lag of

capturing the influence of vegetation loss in neighboring municipalities on local.

is the forest plantation (proxy of reforestation).

represents a vector with the controlling variables, such as GDP per capita, population density, law enforcement, rainfall and temperature.

is a vector of coefficients for

,

is the coefficient of spatial lagged

Y, and

is the error term. In this study, we are particularly interested in

that estimate deforestation leakage effects of forestry expansion on the municipality neighboring. We are also interested in the

accounting for possible livestock intensification mitigation effects.

W is a spatial weight matrix based on distance between municipalities, explicitly accounting for spatial interactions between municipalities, then measuring both neighboring) effects. The construction of

W and sensitivity tests are described in the following sections.

The preferred model to present the results is the FE , selected by several statistical tests and because it control for these unobserved characteristics, ensuring that the estimated relationships reflect within-municipality variations over time rather than cross-sectional differences. The Hausman test was conducted to determine whether fixed effects or random effects provide more consistent estimates. The Breusch-Pagan Lagrange Multiplier test assessed whether a random effects model is preferable over a pooled OLS model.

3.2.1. Spatial Weights Matrix Construction and Sensitiveness Tests

A key component of this study involves modeling spatial dependencies using a spatial weight matrix (

W). We constructed

W as a distance-based weight matrix using the inverse distance metric between the centroids of municipalities’ agricultural land. The final matrix had 648,025 elements in 805x805 municipalities within Brazilian Amazon states (Fig.

Figure 1). The spatial influence between municipalities

i and

j is defined as:

, if

km, else 0. The

is a circle distance between municipalities

i and

j, with a threshold of 300 km. Self-links are set to zero (i.e.

), and row-standardization ensures comparability across observations. We defined 300 km as the threshold because this distance aligns with the average supply radius of slaughterhouses seeking cattle for processing, as reported by studies on beef supply chains in the Amazon [

34,

35]. This assumption reflects the spatial scale at which livestock markets operate, reinforcing the economic rationale behind land-use spillovers in response to reforestation initiatives.

Given the importance of spatial dependence assumptions, sensitivity tests are conducted by varying the distance decay parameter in the inverse-distance weight matrix. Instead of uniform decay, we introduce a distance-decay function weighted by municipality-level land rent:

where

is the distance sensitiveness factor, with values ranging from 50 km to 300 km and

is the annual average gains with agricultural activities (productivity (kg/ha) multiplied by commodity price, according to the IBGE dataset). This approach assumes that deforestation spillovers follows economic returns rather than just physical proximity, and incorporate the economic theory that dictates land use will be (re)allocated where land generates higher returns [

30]. The annual land rent by municipality expanded the spatial weight matrix to over 40 million elements. The impact of these modifications on spatial dependence estimates (

) was evaluated and reported.

The estimated coefficients from our spatial panel model are interpreted as semi-elasticities due to the IHS transformation applied to the variables. Unlike standard linear regressions, where coefficients directly represent absolute changes, the IHS transformation means that the effect of reforestation on deforestation leakage varies depending on the existing level of forestry in a municipality. Therefore, to estimate the impact of a new reforestation project, we must compute the marginal effects based on the estimated coefficients. These effects account for both direct impacts within the municipality and indirect spillovers to neighboring areas. The marginal effects (ME) of the spillover are derived as:

where

represents the reforestation area. Similarly, the direct marginal effect of forest plantation (Within-Municipality Impact) is calculated without including

W in the equation above. This ensures that the estimated impact reflects realistic changes in deforestation leakage considering the nonlinear nature of the IHS transformation. By computing these marginal effects, we provide a policy-relevant measure of how much deforestation leakage could result from reforestation expansion under carbon market mechanisms.

4. Results

Our empirical findings reveal strong path dependency in vegetation loss, with reforestation projects contributing to deforestation leakage through spatial spillovers. These effects depend on economic factors, regional land-use dynamics, and the extent of livestock intensification. The results indicate strong persistence, with an auto-regressive coefficient of 0.56 in the fixed effects model (

Table 2). This suggests that once deforestation occurs, it is likely to continue rather than reversing back to forest cover. The implications are critical: reforestation efforts must account for historical land-use patterns, as degraded areas rarely transition back to natural vegetation without active restoration measures [

36].

4.1. The Extension of Leakage Caused by FOREST plantation

Reforestation projects induce spillovers, increasing deforestation in adjacent areas. In the fixed effects model, local forestry area is negatively associated with vegetation loss (

Table 2), indicating that reforestation reduces vegetation loss within the reforested municipality. However, the spatially weighted forestry variable has a significant positive coefficient, meaning that reforestation in the Amazon indirectly drives forest loss elsewhere (See FE and FD in the

Table 2). The estimated marginal effect is 2% both for FE and FD models, i.e. deforestation leakage for a new area of reforestation. These findings confirm that leakage is a fundamental challenge for carbon crediting schemes. While localized reforestation may appear beneficial, the failure to account for spatial spillovers can lead to an overestimation of net carbon sequestration.

To evaluate how far leakage extends, we conducted sensitivity analysis by varying the spatial weight matrix from 50 km to 300 km. The results show that forestry-related deforestation displacement remains significant up to 150 km (

Table 3). This highlights the need for broader landscape planning strategies to mitigate unintended land-use displacement. We also tested for the temporal extent of reforestation-induced leakage, incorporating lagged proximity effects in panel models. The results indicate that deforestation displacement does not occur instantaneously but unfolds over approximately two years. The second-lag proximity term exhibits the strongest positive coefficient (

Table 4), suggesting that land-use displacement effects intensify after two years. However, this does not necessarily indicate that leakage is limited to short-term dynamics. Instead, it reflects the time required for agricultural expansion decisions to materialize after reforestation reduces available land.

4.2. Livestock Intensification Fails to Offset Displacement Effects

If increasing cattle stocking rates reduces land-use expansion pressure, we would expect it to be negatively associated with deforestation. However, our models reveal no significant mitigation effect: the coefficient on cattle stocking rate is small and statistically insignificant across all specifications (

Table 2). Furthermore, the spatially weighted cattle variable for stocking rate does not show meaningful spillover effects, contradicting claims that livestock intensification can offset reforestation-induced displacement. Instead, extensive cattle production persists despite productivity gains, suggesting that incentives for intensification alone are insufficient to curb deforestation.

4.3. Economic Drivers of Deforestation Leakage

The economic context plays a crucial role in mediating the extent of deforestation leakage. Higher agricultural GDP per capita is correlated with increased deforestation (

Table 2), suggesting that economic expansion amplifies land-use pressures. While local cattle densities do not directly influence deforestation, the indirect effect of agricultural profitability is significant. This aligns with theories of land-market feedback loops, where higher land rents in productive regions push deforestation into less profitable areas. Addressing leakage will require policies that integrate economic incentives with land-use zoning rather than relying solely on reforestation as a mitigation strategy.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Extension of Leakage Caused by Reforestation

Our findings reveal that reforestation-induced deforestation leakage in the Brazilian Amazon is a real but localized phenomenon, with spillover effects occurring primarily within a 150 km radius of reforestation sites. The magnitude of displacement, estimated at 2% of the total reforested area, raises important considerations for the integrity of carbon offset programs. While some level of land-use displacement is inevitable, our results suggest that leakage effects remain relatively contained both spatially and temporally, with their strongest influence occurring within the first two years following reforestation. Since our first differences approach accounts for time-invariant regional factors, the observed leakage effects reflect changes specifically attributable to reforestation rather than pre-existing deforestation trends. Additionally, our inclusion of economic and policy variables ensures that leakage is not misattributed to unrelated land-use drivers, such as commodity price cycles or infrastructure development.

5.2. Drivers of Deforestation Leakage

The presence of leakage highlights a critical distinction between reforestation projects and REDD+ conservation efforts. Much of the existing literature on leakage has focused on forest conservation programs, where restrictions on deforestation shift land-use pressures into unprotected areas [

3,

4]. However, reforestation follows a different dynamic, as it repurposes previously cleared land rather than imposing new conservation restrictions on standing forests. This distinction is essential when considering the extent of displacement and the appropriate policy responses. While some studies argue that reforestation systematically triggers widespread displacement [

30], our findings align more closely with research indicating that leakage is highly context-dependent and influenced by regional economic conditions rather than being an intrinsic consequence of reforestation [

13]. The relatively small-scale displacement effects we observe challenge overly conservative assumptions about the risks associated with reforestation in carbon markets and suggest that a more nuanced approach to leakage assessment is needed.

A key insight from our analysis is the role of scale in determining the extent of leakage. Our results indicate that displacement effects are far more pronounced in large-scale reforestation projects, particularly those that involve corporate-driven reforestation initiatives or extensive commercial forestry plantations. In contrast, we do not detect significant leakage at smaller scales, particularly in regions dominated by smallholder agriculture. Unlike large-scale operations that often rely on economies of scale and land expansion, smallholders may adopt diversified land-use strategies that limit leakage effects, such as agroforestry systems [

37]. Although, increasing capital availability with profitable forestry could incentivize agricultural expansion through the purchase of new land parcels.

The implications of these findings for carbon crediting mechanisms are significant. Existing methodologies for leakage accounting, such as those employed by Verra and ART-TREES, often assume a one-size-fits-all approach to displacement risks, failing to account for variations in land-use scale and economic incentives [

22]. The observed discrepancy between large-scale and smallholder-driven reforestation suggests that leakage estimates should incorporate project-specific characteristics rather than relying on uniform discounting factors. Current carbon credit methodologies, such as those used by Verra and ART-TREES, apply standardized leakage deductions that may not fully account for spatial spillovers. Moreover, the current approaches risk over-penalizing smallholder reforestation efforts, despite the fact that these projects demonstrate lower displacement risks. This misalignment could inadvertently discourage the participation of small-scale landholders in reforestation programs, undermining both social and environmental objectives.

5.3. Livestock Intensification Displacement Effects

One of the most debated solutions for mitigating leakage is livestock intensification, which, in theory, should reduce land expansion pressure by increasing productivity per hectare. However, our findings reveal that increasing stocking rates alone does not significantly offset displacement effects, contradicting the common assumption that productivity gains in the cattle sector will naturally contain deforestation pressures. This aligns with the rebound effect hypothesis, which suggests that improved productivity can, paradoxically, drive further expansion rather than curbing total land demand [

7]. This dynamic is particularly relevant in Brazil, where cattle ranching remains highly responsive to market conditions, with rising profitability incentivizing continued territorial expansion despite technological gains [

14]. These results suggest that intensification must be accompanied by clear land-use governance mechanisms to prevent further encroachment into forested regions. Without regulatory safeguards, intensification alone is unlikely to serve as an effective leakage mitigation strategy.

5.4. Recommendations to Mitigate Leakage from Reforestation in Carbon Markets

Given the relatively small magnitude of detected leakage, the question arises as to whether carbon markets should penalize reforestation projects through financial discounting mechanisms or pursue alternative approaches. A rigid application of leakage discounting could undermine the economic viability of reforestation initiatives, reducing incentives for landholders to engage in reforestation efforts. Rather than penalizing projects financially, a more effective strategy would be to reinvest a portion of carbon credit revenues into local economies, strengthening social safeguards that mitigate displacement risks. Targeted reinvestments could include support for sustainable livelihoods, land tenure security, agroforestry programs, and smallholder-friendly credit mechanisms, all of which would provide long-term incentives for stable land use while preventing further deforestation. By channeling leakage costs into proactive land-use policies rather than reducing carbon credit revenues, reforestation projects could enhance both their climate and socio-economic benefits.

Another key takeaway from our findings is the importance of jurisdictional land-use planning in shaping the extent of leakage. The spatial analysis confirms that leakage effects are highly dependent on regional governance structures, reinforcing the need for a shift away from project-by-project leakage assessments towards broader jurisdictional approaches. Carbon markets must move beyond isolated leakage calculations and integrate more spatially explicit land-use planning measures, ensuring that reforestation efforts align with regional conservation goals. Improved zoning regulations, targeted financial incentives for sustainable land use, and stricter monitoring frameworks could substantially reduce displacement risks while maximizing the carbon sequestration potential of reforestation.

An alternative approach to minimizing deforestation leakage is prioritizing reforestation efforts in areas classified as degraded or abandoned pastures. These lands, which have already lost their agricultural viability, present an opportunity for restoration without increasing land-use competition. Targeting these areas could reduce leakage risks while enhancing carbon sequestration and ecosystem recovery. However, abandoned pastures might be classified as without additionality to carbon sequestration. Thus, reforestation projects need specific policy mechanisms to encourage their restoration, for instance, the argument of incremental connectivity of accelerating growth that otherwise would be stranded.

5.5. Further Studies

While this study provides a robust empirical basis for understanding deforestation leakage caused by forest plantation, further research is needed to assess longer-term dynamics. Since leakage effects appear to be most significant within the first two years after reforestation, future studies should examine whether land-use displacement stabilizes over time or whether secondary waves of deforestation emerge. Additionally, incorporating commodity price fluctuations into land-use models could provide further insights into the economic drivers of displacement [

17]. Given the complexity of land-use dynamics, it is also essential to explore heterogeneous effects across different governance contexts, as leakage risks may vary significantly between regions with strong land tenure institutions and those with weaker regulatory frameworks [

21].

Finally, one limitation of our approach is that it does not assess the impacts on secondary vegetation regrowth. While secondary forests play a key role in carbon sequestration and land-use transitions, their lower economic value compared to forest plantations may result in different displacement dynamics. A key question for future research is whether deforestation leakage disproportionately affects secondary vegetation rather than primary forests. Deforestation in secondary vegetation may outpaced that in primary forest cover, indicating that land-use displacement may increasingly target regenerating forests rather than intact ecosystems. Understanding this shift is crucial for designing reforestation policies that do not inadvertently accelerate the loss of regrowth forests, which play a vital role in carbon sequestration and ecosystem recovery.

6. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence that reforestation efforts in the Brazilian Amazon induce deforestation leakage, displacing agricultural activities into surrounding areas. Our spatial panel analysis indicates that while reforestation reduces vegetation loss within targeted sites, it triggers spillover effects within a 150 km radius, with an estimated 12% leakage rate. These findings highlight the limitations of carbon offset methodologies that fail to account for indirect land-use change, leading to an overestimation of the net sequestration benefits of reforestation projects. The short-term nature of leakage, predominantly occurring within two years, suggests that immediate displacement effects are most critical in evaluating policy effectiveness.

A key insight from our results is that livestock intensification, often proposed as a solution to mitigate land displacement, does not significantly offset leakage. This challenges the assumption that higher productivity automatically translates into reduced deforestation, reinforcing concerns over potential rebound effects that drive further agricultural expansion. Instead of relying on intensification alone, policymakers and carbon market designers must incorporate spatial planning measures, targeted incentives for smallholders, and governance frameworks that prevent reforestation from exacerbating deforestation elsewhere.

These findings carry significant implications for carbon markets, particularly for voluntary standards such as Verra and ART-TREES. Current methodologies apply generic leakage deductions that may either underestimate or over-penalize reforestation projects, failing to differentiate between project scales, economic conditions, and governance contexts. A shift towards jurisdictional approaches—integrating reforestation into broader land-use planning and prioritizing degraded lands—could enhance the credibility of carbon offset schemes while minimizing displacement risks.

Future research should extend this analysis to longer timeframes to assess whether leakage effects stabilize or trigger secondary deforestation waves. Additionally, integrating commodity price fluctuations and land tenure security into spatial models could refine our understanding of economic drivers behind leakage. A key open question is whether reforestation-induced displacement disproportionately targets secondary vegetation rather than primary forests, with significant implications for long-term ecosystem recovery and carbon sequestration.

In sum, while reforestation remains a crucial climate mitigation strategy, its effectiveness hinges on robust spatial assessments and integrated policy frameworks that prevent unintended environmental trade-offs. Carbon markets must evolve to incorporate spatially explicit leakage accounting, ensuring that forest restoration efforts truly contribute to global climate goals without shifting environmental burdens elsewhere.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, and original draft preparation, D.S.; formal analysis, D.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S and S.N.; visualization, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Harvard Dataverse at

https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/A05ACN . These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain of IBGE, INPE, Mapbiomas e other - as described in the methods section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Shoch, D.; Siikamäki, J.V.; Smith, P.; et al. Natural climate solutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, F.d.V.; Lewis, K.; Robertson, A.D.; Pennington, R.T.; Hill, T.C.; Matthews, C.; Lira-Martins, D.; Mazzochini, G.G.; Oliveira, R.S.; Rowland, L. Cost-effective restoration for carbon sequestration across Brazil’s biomes. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 876, 162600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Tu, S. Land use transitions: Progress, challenges and prospects. Land 2021, 10, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aguiar, A.P.D.; Câmara, G.; Ribeiro, D.F.M.P.; Sampaio, G.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Brondizio, M.; Nobre, C.A.; Rosa, N.S.; Oliveira, M.G.P.; Alencar, R.C.C. Land use change emission scenarios: anticipating a forest transition process in the Brazilian Amazon. Global Change Biology 2016, 22, 1821–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P. Global land use change, economic globalization, and the looming land scarcity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 3465–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, A.S.; Bowman, M.; Zilberman, D.M.; O’Neill, K. The viability of cattle ranching intensification in Brazil as a strategy to spare land and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Climatic Change 2014, 126, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, N.; zu Ermgassen, E.K.; Wehkamp, J.; Oliveira Filho, F.J.; Schwerhoff, G. Agricultural productivity and forest conservation: evidence from the Brazilian Amazon. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2019, 101, 919–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, V.R.; Gaspart, F.; Kastner, T.; Meyfroidt, P. Agricultural intensification and land use change: assessing country-level induced intensification, land sparing and rebound effect. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15, 085007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, A.; Andrade, A.; Nelson, C.R.; Cortés, J.; Saavedra, K. Assessing restoration priorities for high-risk ecosystems: An application of the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems. Land use policy 2020, 99, 104874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, T.A.; Grogan, K.A.; Swisher, M.E.; Caviglia-Harris, J.L.; Sills, E.; Harris, D.; Roberts, D.; Putz, F.E. A hybrid optimization-agent-based model of REDD+ payments to households on an old deforestation frontier in the Brazilian Amazon. Environmental modelling & software 2018, 100, 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sacco, A.; Hardwick, K.A.; Blakesley, D.; Brancalion, P.H.; Breman, E.; Cecilio Rebola, L.; Chomba, S.; Dixon, K.; Elliott, S.; Ruyonga, G.; et al. Ten golden rules for reforestation to optimize carbon sequestration, biodiversity recovery and livelihood benefits. Global Change Biology 2021, 27, 1328–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, J.; Ferretti-Gallon, K. What drives and stops deforestation, reforestation, and forest degradation? An updated meta-analysis. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 2023, 17, 217–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, A.; Walker, R. Regional interdependence and forest "transitions": Substitute deforestation limits the relevance of local reversals. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arima, E.Y.; Richards, P.; Walker, R.; Caldas, M.M. Statistical confirmation of indirect land use change in the Brazilian Amazon. Environmental Research Letters 2011, 6, 024010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão Jr, A.; Rausch, L.; Paz Durán, A.; Costa Jr, C.; Spawn, S.A.; Gibbs, H.K. Estimating the potential for conservation and farming in the Amazon and Cerrado under four policy scenarios. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, T.; Chaudhary, A.; Gingrich, S.; Marques, A.; Persson, U.M.; Bidoglio, G.; Le Provost, G.; Schwarzmüller, F. Global agricultural trade and land system sustainability: Implications for ecosystem carbon storage, biodiversity, and human nutrition. One Earth 2021, 4, 1425–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searchinger, T.D.; Wirsenius, S.; Beringer, T.; Dumas, P. Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature 2018, 564, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, N.; Valin, H.; Frank, S.; Galperin, D.; Wade, C.M.; Ringwald, L.; Tanner, D.; Hinkel, N.; Havlík, P.; Baker, J.S.; et al. Understanding Uncertainty in Market-Mediated Responses to US Oilseed Biodiesel Demand: Sensitivity of ILUC Emission Estimates to GLOBIOM Parametric Uncertainty. Environmental Science & Technology 2024, 59, 302–314. [Google Scholar]

- Meyfroidt, P.; De Bremond, A.; Ryan, C.M.; Archer, E.; Aspinall, R.; Chhabra, A.; Camara, G.; Corbera, E.; DeFries, R.; Díaz, S.; et al. Ten facts about land systems for sustainability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2109217118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblois, A.; Damette, O.; Wolfersberger, J. What has driven deforestation in developing countries since the 2000s? Evidence from new remote-sensing data. World Development 2017, 92, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, F.; Soares-Filho, B. Will intensification of beef production deliver conservation outcomes in the Brazilian Amazon? Elem Sci Anth 2017, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, T.; Galt, H.; Lee, D.; Neeff, T.; Streck, C. A close look at the quality of REDD+ carbon credits 2020.

- Moffette, F.; Gibbs, H.K. Agricultural Displacement and Deforestation Leakage in the Brazilian Legal Amazon. Land Economics 2021, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haya, B.K.; Evans, S.; Brown, L.; Bukoski, J.; Butsic, V.; Cabiyo, B.; Jacobson, R.; Kerr, A.; Potts, M.; Sanchez, D.L. Comprehensive review of carbon quantification by improved forest management offset protocols. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2023, 6, 958879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filewod, B.; McCarney, G. Avoiding carbon leakage from nature-based offsets by design. One Earth 2023, 6, 790–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streck, C. REDD+ and leakage: debunking myths and promoting integrated solutions. Climate Policy 2021, 21, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, D.; Yao, X.; Wang, S.; Chi, T.; Meng, Y. Forest emissions reduction assessment using optical satellite imagery and space LiDAR fusion for carbon stock estimation. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE). Projeto PRODES: Monitoramento da Floresta Amazônica Brasileira por Satélite, 2024. Accessed: 14 March 2025.

- Souza Jr, C.M.; Z. Shimbo, J.; Rosa, M.R.; Parente, L.L.; A. Alencar, A.; Rudorff, B.F.; Hasenack, H.; Matsumoto, M.; G. Ferreira, L.; Souza-Filho, P.W.; et al. Reconstructing three decades of land use and land cover changes in brazilian biomes with landsat archive and earth engine. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P.D.; Walker, R.T.; Arima, E.Y. Spatially complex land change: The Indirect effect of Brazil’s agricultural sector on land use in Amazonia. Global Environmental Change 2014, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihounton, G.B.; Henningsen, A. Units of measurement and the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. The Econometrics Journal 2021, 24, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F.; Wichman, C.J. Elasticities and the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 2020, 82, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, E.C. The inverse hyperbolic sine transformation and retransformed marginal effects. The Stata Journal 2022, 22, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, P.; Gibbs, H.; Vale, R.; Munger, J.; Brandão Jr, A.; Christie, M.; Florence, E. Mapping the cattle industry in Brazil’s most dynamic cattle-ranching state: Slaughterhouses in Mato Grosso, 1967-2016. Plos one 2019, 14, e0215286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, P.; Pereira, R.; Brandão Jr, A.; Baima, S. Os frigoríficos vão ajudar a zerar o desmatamento da Amazônia. Imazon & ICV 2017.

- Sloan, S. Reforestation reversals and forest transitions. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zonneveld, M.; Turmel, M.; Hellin, J. Decision-Making to Diversify Farm Systems for Climate Change Adaptation. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).