Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mechanisms of Resistance to ET

2.1. ESR1 Genetic Alterations

2.2. Regulators of the ERα Pathway

2.3. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Other Signaling Pathways

2.4. Metabolic Reprogramming

2.5. Further Mechanisms

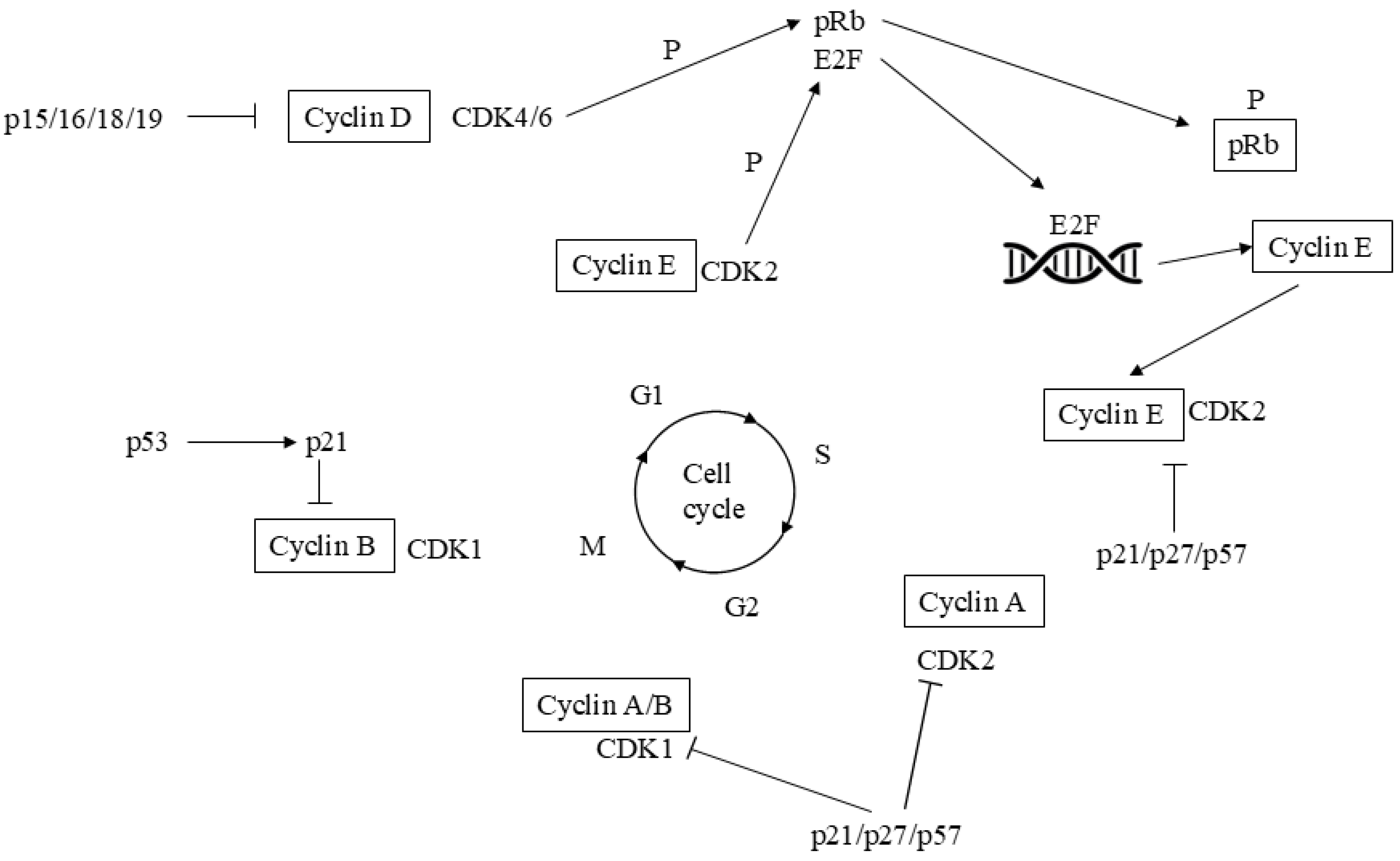

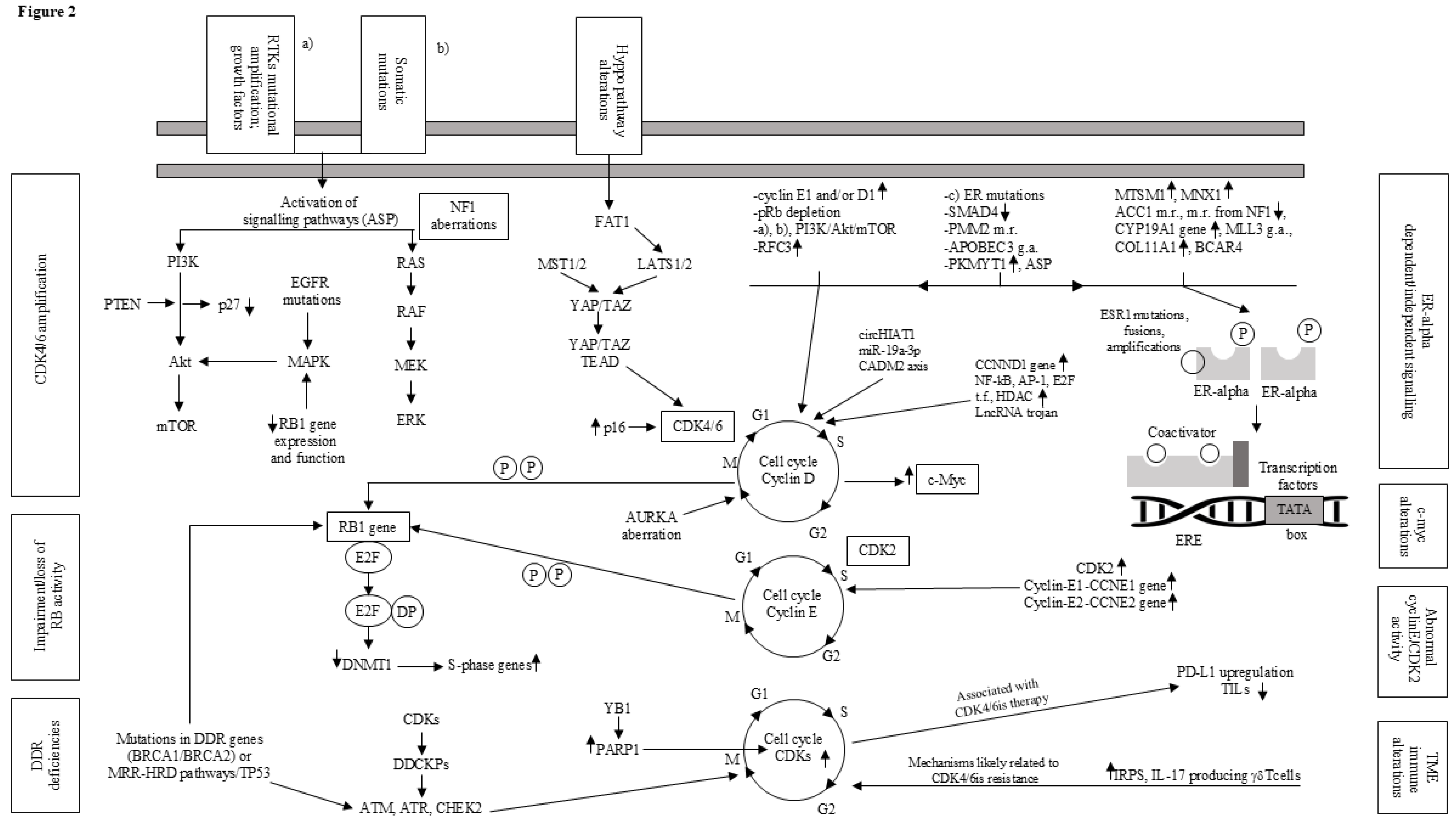

3. CDK4/6is in Association with Endocrine-Therapy

4. Resistance to ET and/or CDK4/6is

4.1. Genetic Alterations Involving Cell Cycle Regulation

4.2. Activation of Alternative Signaling Pathways

4.3. Modifications in Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulators

4.4. Acquired CDK6 Amplification

4.5. Oncogene c-Myc Alteration

4.6. Immunological Alterations in Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

4.7. Proliferation Mechanisms Despite CDK Suppression

5. Common Therapeutic Strategies to Overcome Resistance to ET and/or CDK4/6is

5.1. Fulvestrant, a SERD and Novel Oral SERDs

5.2. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway Inhibitors

5.3. Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

6. Other Therapeutic Strategies

6.1. Continuing CDK4/6is

6.2. Next-Generation Endocrine Agents

6.2.1. CERANs

6.2.2. SSHs

6.2.3. SERCAs

6.2.4. ShERPAs

6.2.5. PROTACs

6.2.6. SARMs

6.3. Agents Targeting CDK7 and CDK2

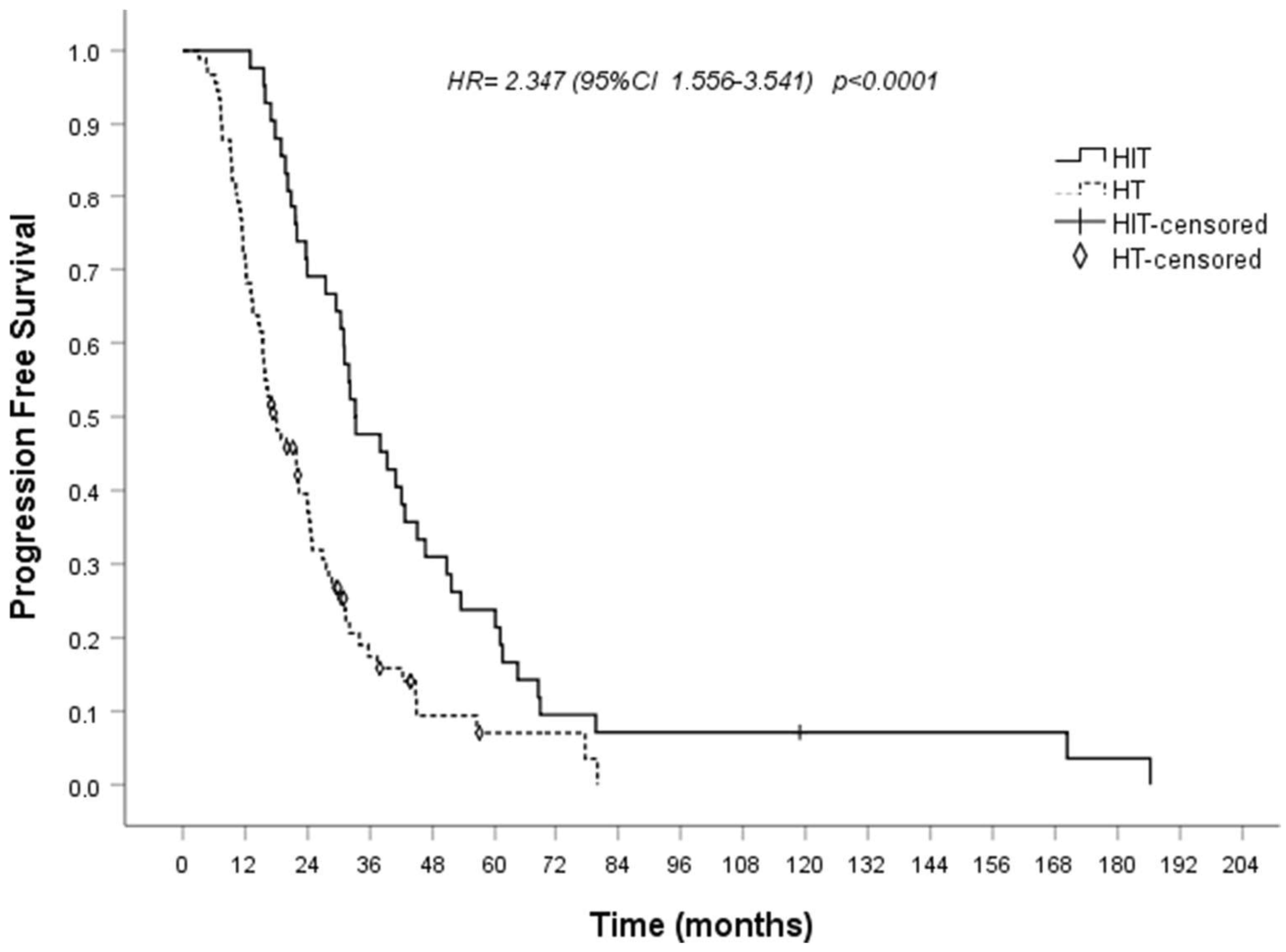

6.4. Immune Therapy (IT)

6.5. Further Drugs and Targets

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allison, K.H.; Hammond, M.E.H.; Dowsett, M.; McKernin, S.E.; Carey, L.A.; Fitzgibbons, P.L.; Hayes, D.F.; Lakhani, S.R.; Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Perlmutter, J.; Perou, C.M.; Regan, M.M.; Rimm, D.L.; Symmans, W.F.; Torlakovic, E.E.; Varella, L.; Viale, G.; Weisberg, T.F.; McShane, L.M.; Wolff, A.C. Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Testing in Breast Cancer: ASCO/CAP Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2020, 38, 1346–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumachi, F.; Santeufemia, D.A.; Basso, S.M. Current medical treatment of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. World J Biol Chem. 2015, 6, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN guidelines. Breast cancer, accessed March15. 2025.

- ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines: Breast Cancer; accessed March 15; 15 March 2025.

- Ferro, A.; Campora, M.; Caldara, A.; De Lisi, D.; Lorenzi, M.; Monteverdi, S.; Mihai, R.; Bisio, A.; Dipasquale, M.; Caffo, O.; Ciribilli, Y. Novel Treatment Strategies for Hormone Receptor (HR)-Positive, HER2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, F.; Costa, A.; Norton, L.; Senkus, E.; Aapro, M.; André, F.; Barrios, C.H.; Bergh, J.; Biganzoli, L.; Blackwell, K.L.; Cardoso, M.J.; Cufer, T.; El Saghir, N.; Fallowfield, L.; Fenech, D.; Francis, P.; Gelmon, K.; Giordano, S.H.; Gligorov, J.; Goldhirsch, A.; Harbeck, N.; Houssami, N.; Hudis, C.; Kaufman, B.; Krop, I.; Kyriakides, S.; Lin, U.N.; Mayer, M.; Merjaver, S.D.; Nordström, E.B.; Pagani, O.; Partridge, A.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Piccart, M.J.; Rugo, H.; Sledge, G.; Thomssen, C.; Van't Veer, L.; Vorobiof, D.; Vrieling, C.; West, N.; Xu, B.; European School of Oncology; European Society of Medical Oncology. ESO-ESMO 2nd international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC2). Breast. 2014, 23, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, S.; DeCristo, M.J.; McAllister, S.S.; Zhao, J.J. CDK4/6 Inhibition in Cancer: Beyond Cell Cycle Arrest. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanker, A.B.; Sudhan, D.R.; Arteaga, C.L. Overcoming Endocrine Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020, 37, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, P.; Chang, M.T.; Xu, G.; Bandlamudi, C.; Ross, D.S.; Vasan, N.; Cai, Y.; Bielski, C.M.; Donoghue, M.T.A.; Jonsson, P.; Penson, A.; Shen, R.; Pareja, F.; Kundra, R.; Middha, S.; Cheng, M.L.; Zehir, A.; Kandoth, C.; Patel, R.; Huberman, K.; Smyth, L.M.; Jhaveri, K.; Modi, S.; Traina, T.A.; Dang, C.; Zhang, W.; Weigelt, B.; Li, B.T.; Ladanyi, M.; Hyman, D.M.; Schultz, N.; Robson, M.E.; Hudis, C.; Brogi, E.; Viale, A.; Norton, L.; Dickler, M.N.; Berger, M.F.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C.A.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Scaltriti, M.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Solit, D.B.; Taylor, B.S.; Baselga, J. The Genomic Landscape of Endocrine-Resistant Advanced Breast Cancers. Cancer Cell. 2018, 34, 427–438.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolletti, M.; Acconcia, F. PMM2 controls ERα levels and cell proliferation in ESR1 Y537S variant expressing breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2024, 584, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, T.; Lai, C.F.; Simmons, G.M.; Goldsbrough, I.; Harrod, A.; Lam, T.; Buluwela, L.; Kjellström, S.; Brueffer, C.; Saal, L.H.; Malmström, J.; Ali, S.; Niméus, E. Proteomic profiling reveals that ESR1 mutations enhance cyclin-dependent kinase signaling. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan, J.; Tan, Y.; Cao, X.X.; Kim, J.A.; Wang, X.; Chamness, G.C.; Maiti, S.N.; Cooper, L.J.; Edwards, D.P.; Contreras, A.; Hilsenbeck, S.G.; Chang, E.C.; Schiff, R.; Wang, X.S. Recurrent ESR1-CCDC170 rearrangements in an aggressive subset of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Nat Commun. 2014 5, 4577. [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.T.; Shao, J.; Zhang, J.; Iglesia, M.; Chan, D.W.; Cao, J.; Anurag, M.; Singh, P.; He, X.; Kosaka, Y.; Matsunuma, R.; Crowder, R.; Hoog, J.; Phommaly, C.; Goncalves, R.; Ramalho, S.; Peres, R.M.R.; Punturi, N.; Schmidt, C.; Bartram, A.; Jou, E.; Devarakonda, V.; Holloway, K.R.; Lai, W.V.; Hampton, O.; Rogers, A.; Tobias, E.; Parikh, P.A.; Davies, S.R.; Li, S.; Ma, C.X.; Suman, V.J.; Hunt, K.K.; Watson, M.A.; Hoadley, K.A.; Thompson, E.A.; Chen, X.; Kavuri, S.M.; Creighton, C.J.; Maher, C.A.; Perou, C.M.; Haricharan, S.; Ellis, M.J. Functional Annotation of ESR1 Gene Fusions in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 1434–1444.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.A.; Hoog, J.; Chin, S.F.; Tao, Y.; Zayed, A.A.; Chin, K.; Teschendorff, A.E.; Quackenbush, J.F.; Marioni, J.C.; Leung, S.; Perou, C.M.; Neilsen, T.O.; Ellis, M.; Gray, J.W.; Bernard, P.S.; Huntsman, D.G.; Caldas, C. ESR1 gene amplification in breast cancer: a common phenomenon? Nat Genet. 2008, 40, 806–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, F.; Moelans, C.B.; Filipits, M.; Singer, C.F.; Simon, R.; van Diest, P.J. On the evidence for ESR1 amplification in breast cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012, 12, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moelans, C.B.; Holst, F.; Hellwinkel, O.; Simon, R.; van Diest, P.J. ESR1 amplification in breast cancer by optimized RNase FISH: frequent but low-level and heterogeneous. PLoS One 2013, 8, e84189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertson, D.G. Conflicting evidence on the frequency of ESR1 amplification in breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2008, 40, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.V.; Ejlertsen, B.; Müller, S.; Møller, S.; Rasmussen, B.B.; Balslev, E.; Lænkholm, A.V.; Christiansen, P.; Mouridsen, H.T. Amplification of ESR1 may predict resistance to adjuvant tamoxifen in postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011, 127, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, S.; Zhang, Z.; Nakano, M.; Ibusuki, M.; Kawazoe, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Iwase, H. Estrogen receptor alpha gene ESR1 amplification may predict endocrine therapy responsiveness in breast cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.E.; Pantaleo, J.; Bolivar, P.; Bocci, M.; Sjölund, J.; Morsing, M.; Cordero, E.; Larsson, S.; Malmberg, M.; Seashore-Ludlow, B.; Pietras, K. Cancer-associated fibroblasts rewire the estrogen receptor response in luminal breast cancer, enabling estrogen independence. Oncogene. 2024, 43, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, R.; He, M.; Li, H.; Bai, Y.; Wang, A.; Sun, G.; Zhou, B.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Zeng, K.; Feng, J.; Lin, L.; Wei, Y.; Kato, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y. MYSM1 acts as a novel co-activator of ERα to confer antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer. EMBO Mol Med. 2024, 16, 10–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, F.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Xia, G.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Qi, W.; Gao, G.; Yang, X. Macrophages Promote Subtype Conversion and Endocrine Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Shu, D.; Li, H.; Lan, A.; Zhang, W.; Tan, Z.; Huang, M.; Tomasi, M.L.; Jin, A.; Yu, H.; Shen, M.; Liu, S. SMAD4 depletion contributes to endocrine resistance by integrating ER and ERBB signaling in HR + HER2- breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolini, A.; Ferrari, P.; Duffy, M.J. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in breast cancer: Past, present and future. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018, 2018 52(Pt 1) Pt 1, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millis, S.Z.; Ikeda, S.; Reddy, S.; Gatalica, Z.; Kurzrock, R. Landscape of Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase Pathway Alterations Across 19 784 Diverse Solid Tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurokawa, H.; Lenferink, A.E.; Simpson, J.F.; Pisacane, P.I.; Sliwkowski, M.X.; Forbes, J.T.; Arteaga, C.L. Inhibition of HER2/neu (erbB-2) and mitogen-activated protein kinases enhances tamoxifen action against HER2-overexpressing, tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 5887–5894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fribbens, C.; Garcia Murillas, I.; Beaney, M.; Hrebien, S.; O'Leary, B.; Kilburn, L.; Howarth, K.; Epstein, M.; Green, E.; Rosenfeld, N.; Ring, A.; Johnston, S.; Turner, N. Tracking evolution of aromatase inhibitor resistance with circulating tumour DNA analysis in metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018, 29, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, F.; Ciruelos, E.; Rubovszky, G.; Campone, M.; Loibl, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Iwata, H.; Conte, P.; Mayer, I.A.; Kaufman, B.; Yamashita, T.; Lu, Y.S.; Inoue, K.; Takahashi, M.; Pápai, Z.; Longin, A.S.; Mills, D.; Wilke, C.; Hirawat, S.; Juric, D.; SOLAR-1 Study Group. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-Mutated, Hormone Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 1929–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012, 490, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, M.D.; Hopkins, B.D.; Cantley, L.C. Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase, Growth Disorders, and Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 2052–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, L.; Smid, M.; Wilting, S.M.; van Riet, J.; Van Hoeck, A.; Nguyen, L.; Nik-Zainal, S.; Steenbruggen, T.G.; Tjan-Heijnen, V.C.G.; Labots, M.; van Riel, J.M.G.H.; Bloemendal, H.J.; Steeghs, N.; Lolkema, M.P.; Voest, E.E.; van de Werken, H.J.G.; Jager, A.; Cuppen, E.; Sleijfer, S.; Martens, J.W.M. The genomic landscape of metastatic breast cancer highlights changes in mutation and signature frequencies. Nat Genet. 2019, 51, 1450–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, G.E.; Franke, T.F.; Moroni, M.; Mueller, S.; Morgan, E.; Iann, M.C.; Winder, A.D.; Reiter, R.; Wellstein, A.; Martin, M.B.; Stoica, A. Effect of estradiol on estrogen receptor-alpha gene expression and activity can be modulated by the ErbB2/PI 3-K/Akt pathway. Oncogene. 2003, 22, 7998–8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, C.G.; Ma, C.X.; Crowder, R.J.; Guintoli, T.; Phommaly, C.; Gao, F.; Lin, L.; Ellis, M.J. Preclinical modeling of combined phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase inhibition with endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.W.; Hennessy, B.T.; González-Angulo, A.M.; Fox, E.M.; Mills, G.B.; Chen, H.; Higham, C.; García-Echeverría, C.; Shyr, Y.; Arteaga, C.L. Hyperactivation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase promotes escape from hormone dependence in estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2010, 120, 2406–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselga, J.; Campone, M.; Piccart, M.; Burris HA3rd Rugo, H.S.; Sahmoud, T.; Noguchi, S.; Gnant, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Lebrun, F.; Beck, J.T.; Ito, Y.; Yardley, D.; Deleu, I.; Perez, A.; Bachelot, T.; Vittori, L.; Xu, Z.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Lebwohl, D.; Hortobagyi, G.N. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012, 366, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamnik, R.L.; Holz, M.K. mTOR/S6K1 and MAPK/RSK signaling pathways coordinately regulate estrogen receptor alpha serine 167 phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamnik, R.L.; Digilova, A.; Davis, D.C.; Brodt, Z.N.; Murphy, C.J.; Holz, M.K. S6 kinase 1 regulates estrogen receptor alpha in control of breast cancer cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2009, 284, 6361–6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efeyan, A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR and cancer: many loops in one pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010, 22, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brufsky, A.M.; Dickler, M.N. Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Exploiting Signaling Pathways Implicated in Endocrine Resistance. Oncologist. 2018, 23, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.M.; Zhao, D.C.; Li, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.N.; Du, T.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.H.; Yu, Q.C.; Chen, Q.S.; Cai, R.Z.; Zhao, Z.X.; Shan, J.L.; Hu, B.X.; Zhang, H.L.; Feng, G.K.; Zhu, X.F.; Tang, J.; Deng, R. Inactivated cGAS-STING Signaling Facilitates Endocrine Resistance by Forming a Positive Feedback Loop with AKT Kinase in ER+HER2- Breast Cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2403592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, A.; Morales, F.; Walbaum, B. Fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: mechanisms and role in endocrine resistance. Front Oncol. 2024, 2024 14, 1406951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.Y.; Anurag, M.; Lei, J.T.; Cao, J.; Singh, P.; Peng, J.; Kennedy, H.; Nguyen, N.C.; Chen, Y.; Lavere, P.; Li, J.; Du, X.H.; Cakar, B.; Song, W.; Kim, B.J.; Shi, J.; Seker, S.; Chan, D.W.; Zhao, G.Q.; Chen, X.; Banks, K.C.; Lanman, R.B.; Shafaee, M.N.; Zhang, X.H.; Vasaikar, S.; Zhang, B.; Hilsenbeck, S.G.; Li, W.; Foulds, C.E.; Ellis, M.J.; Chang, E.C. Neurofibromin Is an Estrogen Receptor-α Transcriptional Co-repressor in Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020, 37, 387–402.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.; Proszek, P.; Pascual, J.; Fribbens, C.; Shamsher, M.K.; Kingston, B.; O'Leary, B.; Herrera-Abreu, M.T.; Cutts, R.J.; Garcia-Murillas, I.; Bye, H.; Walker, B.A.; Gonzalez De Castro, D.; Yuan, L.; Jamal, S.; Hubank, M.; Lopez-Knowles, E.; Schuster, E.F.; Dowsett, M.; Osin, P.; Nerurkar, A.; Parton, M.; Okines, A.F.C.; Johnston, S.R.D.; Ring, A.; Turner, N.C. Inactivating NF1 Mutations Are Enriched in Advanced Breast Cancer and Contribute to Endocrine Therapy Resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Martinez, L.; Zhang, Y.; Nakata, Y.; Chan, H.L.; Morey, L. Epigenetic mechanisms in breast cancer therapy and resistance. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, J. NF-κB signaling in therapy resistance of breast cancer: Mechanisms, approaches, and challenges. Life Sci 2024, 348, 122684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, M.; Lorito, N.; Smiriglia, A.; Subbiani, A.; Bonechi, F.; Comito, G.; Morriset, L.; El Botty, R.; Benelli, M.; López-Velazco, J.I.; Caffarel, M.M.; Urruticoechea, A.; Sflomos, G.; Malorni, L.; Corsini, M.; Ippolito, L.; Giannoni, E.; Meattini, I.; Matafora, V.; Havas, K.; Bachi, A.; Chiarugi, P.; Marangoni, E.; Morandi, A. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 controls a lipid droplet-peroxisome axis and is a vulnerability of endocrine-resistant ER+ breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2024, 16, eadf9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, R.R.J.; Tovar, E.A.; Redlon, L.N.; Essenburg, C.J.; Dischinger, P.S.; Ellis, A.E.; Beddows, I.; Sheldon, R.D.; Lien, E.C.; Graveel, C.R.; Steensma, M. NF1 deficiency drives metabolic reprogramming in ER+ breast cancer. Mol Metab. 2024, 80, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Barozzi, I.; Faronato, M.; Lombardo, Y.; Steel, J.H.; Patel, N.; Darbre, P.; Castellano, L.; Győrffy, B.; Woodley, L.; Meira, A.; Patten, D.K.; Vircillo, V.; Periyasamy, M.; Ali, S.; Frige, G.; Minucci, S.; Coombes, R.C.; Magnani, L. Differential epigenetic reprogramming in response to specific endocrine therapies promotes cholesterol biosynthesis and cellular invasion. Nat Commun. 2015 6, 10044.

- Gala, K.; Li, Q.; Sinha, A.; Razavi, P.; Dorso, M.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Chung, Y.R.; Hendrickson, R.; Hsieh, J.J.; Berger, M.; Schultz, N.; Pastore, A.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Chandarlapaty, S. KMT2C mediates the estrogen dependence of breast cancer through regulation of ERα enhancer function. Oncogene. 2018, 37, 4692–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatci, O.; Alam, R.; Huynh-Dam, K.T.; Isik, A.; Uner, M.; Belder, N.; Ersan, P.G.; Tokat, U.M.; Ulukan, B.; Cetin, M.; Calisir, K.; Gedik, M.E.; Bal, H.; Sener Sahin, O.; Riazalhosseini, Y.; Thieffry, D.; Gautheret, D.; Ogretmen, B.; Aksoy, S.; Uner, A.; Akyol, A.; Sahin, O. Targeting LINC00152 activates cAMP/Ca2+/ferroptosis axis and overcomes tamoxifen resistance in ER+ breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Duan, S.; Zhou, X.; Meng, Y.; Chen, X. Overexpression of COL11A1 confers tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2024, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Webster, J.; Coonrod, E.M.; Weilbaecher, K.N.; Maher, C.A.; White, N.M. BCAR4 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker for Endocrine Therapy Resistance in Breast Cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2024, 24, 368–375.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Miyashita, M.; Maeda, I.; Goda, A.; Tada, H.; Amari, M.; Kojima, Y.; Tsugawa, K.; Ohi, Y.; Sagara, Y.; Sato, M.; Ebata, A.; Harada-Shoji, N.; Suzuki, T.; Nakanishi, M.; Ohta, T.; Ishida, T. Potential role of Fbxo22 in resistance to endocrine therapy in breast cancer with invasive lobular carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2024, 204, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Ye, L.; Sun, S.; Yuan, J.; Huang, J.; Zeng, Z. Involvement of RFC3 in tamoxifen resistance in ER-positive breast cancer through the cell cycle. Aging (Albany NY). 2023, 15, 13738–13752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muise-Helmericks, R.C.; Grimes, H.L.; Bellacosa, A.; Malstrom, S.E.; Tsichlis, P.N.; Rosen, N. Cyclin D expression is controlled post-transcriptionally via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273, 29864–29872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, F.S.; Hui, R.; Musgrove, E.A.; Gee, J.M.; Blamey, R.W.; Nicholson, R.I.; Sutherland, R.L.; Robertson, J.F. Overexpression of cyclin D1 messenger RNA predicts for poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 2069–2076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kilker, R.L.; Planas-Silva, M.D. Cyclin D1 is necessary for tamoxifen-induced cell cycle progression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 11478–11484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcken, N.R.; Prall, O.W.; Musgrove, E.A.; Sutherland, R.L. Inducible overexpression of cyclin D1 in breast cancer cells reverses the growth-inhibitory effects of antiestrogens. Clin Cancer Res. 1997, 3, 849–854. [Google Scholar]

- Vora, S.R.; Juric, D.; Kim, N.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Huynh, T.; Costa, C.; Lockerman, E.L.; Pollack, S.F.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; Lehar, J.; Wiesmann, M.; Wartmann, M.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Z.A.; Pinzon-Ortiz, M.; Kim, S.; Schlegel, R.; Huang, A.; Engelman, J.A. CDK 4/6 inhibitors sensitize PIK3CA mutant breast cancer to PI3K inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2014, 26, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Aleshin, A.; Slamon, D.J. Targeting the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) 4/6 in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2016, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortobagyi, G.N.; Stemmer, S.M.; Burris, H.A.; Yap, Y.S.; Sonke, G.S.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Campone, M.; Petrakova, K.; Blackwell, K.L.; Winer, E.P.; Janni, W.; Verma, S.; Conte, P.; Arteaga, C.L.; Cameron, D.A.; Mondal, S.; Su, F.; Miller, M.; Elmeliegy, M.; Germa, C.; O'Shaughnessy, J. Updated results from MONALEESA-2, a phase III trial of first-line ribociclib plus letrozole versus placebo plus letrozole in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018, 29, 1541–1547, Erratum in: Ann Oncol. 2019, 30, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.A.; Lu, Y.S.; Bardia, A.; Harbeck, N.; Colleoni, M.; Franke, F.; Chow, L.; Sohn, J.; Lee, K.S.; Campos-Gomez, S.; Villanueva-Vazquez, R.; Jung, K.H.; Chakravartty, A.; Hughes, G.; Gounaris, I.; Rodriguez-Lorenc, K.; Taran, T.; Hurvitz, S.; Tripathy, D. Overall Survival with Ribociclib plus Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019, 381, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.; Martin, M.; Di Leo, A.; Im, S.A.; Awada, A.; Forrester, T.; Frenzel, M.; Hardebeck, M.C.; Cox, J.; Barriga, S.; Toi, M.; Iwata, H.; Goetz, M.P. MONARCH 3 final PFS: a randomized study of abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2019, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugo, H.S.; Finn, R.S.; Diéras, V.; Ettl, J.; Lipatov, O.; Joy, A.A.; Harbeck, N.; Castrellon, A.; Iyer, S.; Lu, D.R.; Mori, A.; Gauthier, E.R.; Bartlett, C.H.; Gelmon, K.A.; Slamon, D.J. Palbociclib plus letrozole as first-line therapy in estrogen receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer with extended follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019, 174, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortobagyi, G.N.; Stemmer, S.M.; Burris, H.A.; Yap, Y.S.; Sonke, G.S.; Hart, L.; Campone, M.; Petrakova, K.; Winer, E.P.; Janni, W.; Conte, P.; Cameron, D.A.; André, F.; Arteaga, C.L.; Zarate, J.P.; Chakravartty, A.; Taran, T.; Le Gac, F.; Serra, P.; O'Shaughnessy, J. Overall Survival with Ribociclib plus Letrozole in Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022, 386, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.S.; Im, S.A.; Colleoni, M.; Franke, F.; Bardia, A.; Cardoso, F.; Harbeck, N.; Hurvitz, S.; Chow, L.; Sohn, J.; Lee, K.S.; Campos-Gomez, S.; Villanueva Vazquez, R.; Jung, K.H.; Babu, K.G.; Wheatley-Price, P.; De Laurentiis, M.; Im, Y.H.; Kuemmel, S.; El-Saghir, N.; O'Regan, R.; Gasch, C.; Solovieff, N.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Chakravartty, A.; Ji, Y.; Tripathy, D. Updated Overall Survival of Ribociclib plus Endocrine Therapy versus Endocrine Therapy Alone in Pre- and Perimenopausal Patients with HR+/HER2- Advanced Breast Cancer in MONALEESA-7: A Phase III Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masurkar, P.P.; Prajapati, P.; Canedo, J.; Goswami, S.; Earl, S.; Bhattacharya, K. Cost-effectiveness of CDK4/6 inhibitors in HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024, 40, 1753–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, N.C.; Slamon, D.J.; Ro, J.; Bondarenko, I.; Im, S.A.; Masuda, N.; Colleoni, M.; DeMichele, A.; Loi, S.; Verma, S.; Iwata, H.; Harbeck, N.; Loibl, S.; André, F.; Puyana Theall, K.; Huang, X.; Giorgetti, C.; Huang Bartlett, C.; Cristofanilli, M. Overall Survival with Palbociclib and Fulvestrant in Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 1926–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamon, D.J.; Neven, P.; Chia, S.; Fasching, P.A.; De Laurentiis, M.; Im, S.A.; Petrakova, K.; Bianchi, G.V.; Esteva, F.J.; Martín, M.; Nusch, A.; Sonke, G.S.; De la Cruz-Merino, L.; Beck, J.T.; Pivot, X.; Sondhi, M.; Wang, Y.; Chakravartty, A.; Rodriguez-Lorenc, K.; Taran, T.; Jerusalem, G. Overall Survival with Ribociclib plus Fulvestrant in Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neven, P.; Fasching, P.A.; Chia, S.; Jerusalem, G.; De Laurentiis, M.; Im, S.A.; Petrakova, K.; Bianchi, G.V.; Martín, M.; Nusch, A.; Sonke, G.S.; De la Cruz-Merino, L.; Beck, J.T.; Zarate, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Chakravartty, A.; Wang, C.; Slamon, D.J. Updated overall survival from the MONALEESA-3 trial in postmenopausal women with HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer receiving first-line ribociclib plus fulvestrant. Breast Cancer Res. 2023, 25, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledge GWJr Toi, M.; Neven, P.; Sohn, J.; Inoue, K.; Pivot, X.; Burdaeva, O.; Okera, M.; Masuda, N.; Kaufman, P.A.; Koh, H.; Grischke, E.M.; Conte, P.; Lu, Y.; Barriga, S.; Hurt, K.; Frenzel, M.; Johnston, S.; Llombart-Cussac, A. The Effect of Abemaciclib Plus Fulvestrant on Overall Survival in Hormone Receptor-Positive, ERBB2-Negative Breast Cancer That Progressed on Endocrine Therapy-MONARCH 2: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Fernández, M.; Malumbres, M. Mechanisms of Sensitivity and Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2020, 37, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Hackbart, H.; Cui, X.; Yuan, Y. CDK4/6 Inhibitor Resistance in Hormone Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer: Translational Research, Clinical Trials, and Future Directions. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 11791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Gazzo, A.; Selenica, P.; Safonov, A.; Pareja, F.; da Silva, E.M.; Brown, D.N.; Zhu, Y.; Patel, J.; Blanco-Heredia, J.; Stefanovska, B.; Carpenter, M.A.; Pei, X.; Frosina, D.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Ladanyi, M.; Curigliano, G.; Weigelt, B.; Riaz, N.; Powell, S.N.; Razavi, P.; Harris, R.S.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Marra, A.; Chandarlapaty, S. APOBEC3 mutagenesis drives therapy resistance in breast cancer. bioRxiv 2024, 591453. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, M.R.; Brett, J.O.; Carmeli, A.; Weipert, C.M.; Zhang, N.; Yu, J.; Bucheit, L.; Medford, A.J.; Wagle, N.; Bardia, A.; Wander, S.A. CDK4/6 Inhibitor Efficacy in ESR1-Mutant Metastatic Breast Cancer. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Litchfield, L.M.; Webster, Y.; Chio, L.C.; Wong, S.S.; Stewart, T.R.; Dowless, M.; Dempsey, J.; Zeng, Y.; Torres, R.; Boehnke, K.; Mur, C.; Marugán, C.; Baquero, C.; Yu, C.; Bray, S.M.; Wulur, I.H.; Bi, C.; Chu, S.; Qian, H.R.; Iversen, P.W.; Merzoug, F.F.; Ye, X.S.; Reinhard, C.; De Dios, A.; Du, J.; Caldwell, C.W.; Lallena, M.J.; Beckmann, R.P.; Buchanan, S.G. Genomic Aberrations that Activate D-type Cyclins Are Associated with Enhanced Sensitivity to the CDK4 and CDK6 Inhibitor Abemaciclib. Cancer Cell. 2017, 32, 761–776.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, N.C.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Loi, S.; Colleoni, M.; Loibl, S.; DeMichele, A.; Harbeck, N.; André, F.; Bayar, M.A.; Michiels, S.; Zhang, Z.; Giorgetti, C.; Arnedos, M.; Huang Bartlett, C.; Cristofanilli, M. Cyclin E1 Expression and Palbociclib Efficacy in Previously Treated Hormone Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019, 37, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wander, S.A.; Cohen, O.; Gong, X.; Johnson, G.N.; Buendia-Buendia, J.E.; Lloyd, M.R.; Kim, D.; Luo, F.; Mao, P.; Helvie, K.; Kowalski, K.J.; Nayar, U.; Waks, A.G.; Parsons, S.H.; Martinez, R.; Litchfield, L.M.; Ye, X.S.; Yu, C.; Jansen, V.M.; Stille, J.R.; Smith, P.S.; Oakley, G.J.; Chu, Q.S.; Batist, G.; Hughes, M.E.; Kremer, J.D.; Garraway, L.A.; Winer, E.P.; Tolaney, S.M.; Lin, N.U.; Buchanan, S.G.; Wagle, N. The Genomic Landscape of Intrinsic and Acquired Resistance to Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitors in Patients with Hormone Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1174–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palafox, M.; Monserrat, L.; Bellet, M.; Villacampa, G.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Oliveira, M.; Brasó-Maristany, F.; Ibrahimi, N.; Kannan, S.; Mina, L.; Herrera-Abreu, M.T.; Òdena, A.; Sánchez-Guixé, M.; Capelán, M.; Azaro, A.; Bruna, A.; Rodríguez, O.; Guzmán, M.; Grueso, J.; Viaplana, C.; Hernández, J.; Su, F.; Lin, K.; Clarke, R.B.; Caldas, C.; Arribas, J.; Michiels, S.; García-Sanz, A.; Turner, N.C.; Prat, A.; Nuciforo, P.; Dienstmann, R.; Verma, C.S.; Lopez-Bigas, N.; Scaltriti, M.; Arnedos, M.; Saura, C.; Serra, V. High p16 expression and heterozygous RB1 loss are biomarkers for CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance in ER+ breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safonov, A.; Marra, A.; Bandlamudi, C.; O'Leary, B.; Wubbenhorst, B.; Ferraro, E.; Moiso, E.; Lee, M.; An, J.; Donoghue, M.T.A.; Will, M.; Pareja, F.; Nizialek, E.; Lukashchuk, N.; Sofianopoulou, E.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Ahmed, M.; Mehine, M.M.; Ross, D.; Mandelker, D.; Ladanyi, M.; Schultz, N.; Berger, M.F.; Scaltriti, M.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Li, B.T.; Offit, K.; Norton, L.; Shen, R.; Shah, S.; Maxwell, K.N.; Couch, F.; Domchek, S.M.; Solit, D.B.; Nathanson, K.L.; Robson, M.E.; Turner, N.C.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Razavi, P. Tumor suppressor heterozygosity and homologous recombination deficiency mediate resistance to front-line therapy in breast cancer. bioRxiv 2024 02.05.57 8934.

- Sablin, M.P.; Gestraud, P.; Jonas, S.F.; Lamy, C.; Lacroix-Triki, M.; Bachelot, T.; Filleron, T.; Lacroix, L.; Tran-Dien, A.; Jézéquel, P.; Mauduit, M.; Barros Monteiro, J.; Jimenez, M.; Michiels, S.; Attignon, V.; Soubeyran, I.; Driouch, K.; Servant, N.; Le Tourneau, C.; Kamal, M.; André, F.; Bièche, I. Copy number alterations in metastatic and early breast tumours: prognostic and acquired biomarkers of resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2024, 131, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouery, B.L.; Baker, E.M.; Mei, L.; Wolff, S.C.; Mills, C.A.; Fleifel, D.; Mulugeta, N.; Herring, L.E.; Cook, J.G. APC/C prevents a noncanonical order of cyclin/CDK activity to maintain CDK4/6 inhibitor-induced arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024, 121, e2319574121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, R.; Vaira, V.; Giordano, L.; Fernandes, B.; Saltalamacchia, G.; Palumbo, R.; Carnaghi, C.; Basilico, V.; Gentile, F.; Masci, G.; De Sanctis, R.; Santoro, A. Identification of a Panel of miRNAs Associated with Resistance to Palbociclib and Endocrine Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formisano, L.; Lu, Y.; Servetto, A.; Hanker, A.B.; Jansen, V.M.; Bauer, J.A.; Sudhan, D.R.; Guerrero-Zotano, A.L.; Croessmann, S.; Guo, Y.; Ericsson, P.G.; Lee, K.M.; Nixon, M.J.; Schwarz, L.J.; Sanders, M.E.; Dugger, T.C.; Cruz, M.R.; Behdad, A.; Cristofanilli, M.; Bardia, A.; O'Shaughnessy, J.; Nagy, R.J.; Lanman, R.B.; Solovieff, N.; He, W.; Miller, M.; Su, F.; Shyr, Y.; Mayer, I.A.; Balko, J.M.; Arteaga, C.L. Aberrant FGFR signaling mediates resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors in ER+ breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Razavi, P.; Li, Q.; Toy, W.; Liu, B.; Ping, C.; Hsieh, W.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Brown, D.N.; Da Cruz Paula, A.F.; Morris, L.; Selenica, P.; Eichenberger, E.; Shen, R.; Schultz, N.; Rosen, N.; Scaltriti, M.; Brogi, E.; Baselga, J.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Chandarlapaty, S. Loss of the FAT1 Tumor Suppressor Promotes Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibitors via the Hippo Pathway. Cancer Cell. 2018, 34, 893–905.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talia, M.; Cirillo, F.; Scordamaglia, D.; Di Dio, M.; Zicarelli, A.; De Rosis, S.; Miglietta, A.M.; Capalbo, C.; De Francesco, E.M.; Belfiore, A.; Grande, F.; Rizzuti, B.; Occhiuzzi, M.A.; Fortino, G.; Guzzo, A.; Greco, G.; Maggiolini, M.; Lappano, R. The G Protein Estrogen Receptor (GPER) is involved in the resistance to the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belli, S.; Esposito, D.; Ascione, C.M.; Messina, F.; Napolitano, F.; Servetto, A.; De Angelis, C.; Bianco, R.; Formisano, L. EGFR and HER2 hyper-activation mediates resistance to endocrine therapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors in ER+ breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2024, 593, 216968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Kim, B.J.; Mitra, A.; Vollert, C.T.; Lei, J.T.; Fandino, D.; Anurag, M.; Holt, M.V.; Gou, X.; Pilcher, J.B.; Goetz, M.P.; Northfelt, D.W.; Hilsenbeck, S.G.; Marshall, C.G.; Hyer, M.L.; Papp, R.; Yin, S.Y.; De Angelis, C.; Schiff, R.; Fuqua, S.A.W.; Ma, C.X.; Foulds, C.E.; Ellis, M.J. PKMYT1 Is a Marker of Treatment Response and a Therapeutic Target for CDK4/6 Inhibitor-Resistance in ER+ Breast Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 1494–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindt, C.K.; Alves, C.L.; Ehmsen, S.; Kragh, A.; Reinert, T.; Vogsen, M.; Kodahl, A.R.; Rønlev, J.D.; Ardik, D.; Sørensen, A.L.; Evald, K.; Clemmensen, M.L.; Staaf, J.; Ditzel, H.J. Genomic alterations associated with resistance and circulating tumor DNA dynamics for early detection of progression on CDK4/6 inhibitor in advanced breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2024, 155, 2211–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Niu, C.; Yi, G.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, B. Quercetin inhibits the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and reverses CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance in breast cancer by regulating circHIAT1/miR-19a-3p/CADM2 axis. PLoS One. 2024, 19, e0305612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Kang, X.; Zhu, J.; Long, S.; Han, Y.; Xue, C.; Sun, Z.; Du, Y.; Hu, J.; Pan, L.; Zhou, F.; Xu, X.; Li, X. SLC7A11 protects luminal A breast cancer cells against ferroptosis induced by CDK4/6 inhibitors. Redox Biol. 2024, 76, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Kai, Y.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Peng, C.; Li, Z.; Mughal, M.J.; Julie, B.; Zheng, X.; Ma, J.; Ma, C.X.; Shen, M.; Hall, M.D.; Li, S.; Zhu, W. O-GlcNAcylation of MITF regulates its activity and CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance in breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lim, B.; Pearson, T.; Tripathy, D.; Ordentlich, P.; Ueno, N.T. The synergistic antitumor activity of entinostat (MS-275) in combination with palbociclib (PD 0332991) in estrogen receptor-positive and triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res 2018, 78 (4_Supplement), P5-21-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, M.C.; Pazaiti, A.; Iliakopoulos, K.; Markouli, M.; Michalaki, V.; Papadimitriou, C.A. Resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition: Mechanisms and strategies to overcome a therapeutic problem in the treatment of hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2022, 1869, 119346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, L.; Wander, S.A.; Visal, T.; Wagle, N.; Shapiro, G.I. MicroRNA-Mediated Suppression of the TGF-β Pathway Confers Transmissible and Reversible CDK4/6 Inhibitor Resistance. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 2667–2680.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Ge, L.P.; Li, D.Q.; Shao, Z.M.; Di, G.H.; Xu, X.E.; Jiang, Y.Z. LncRNA TROJAN promotes proliferation and resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitor via CDK2 transcriptional activation in ER+ breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020, 19, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, Z.; Bhatt, T.; Dickler, M.; Giri, D.; Scaltriti, M.; Baselga, J.; Rosen, N.; Chandarlapaty, S. Acquired CDK6 amplification promotes breast cancer resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors and loss of ER signaling and dependence. Oncogene. 2017, 36, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, X.; Xiong, Y.; Li, R.; Ito, T.; Ahmed, T.A.; Karoulia, Z.; Adamopoulos, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Xie, L.; Liu, J.; Ueberheide, B.; Aaronson, S.A.; Chen, X.; Buchanan, S.G.; Sellers, W.R.; Jin, J.; Poulikakos, P.I. Distinct CDK6 complexes determine tumor cell response to CDK4/6 inhibitors and degraders. Nat Cancer. 2021, 2, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qasem, A.J.; Alves, C.L.; Ehmsen, S.; Tuttolomondo, M.; Terp, M.G.; Johansen, L.E.; Vever, H.; Hoeg, L.V.A.; Elias, D.; Bak, M.; Ditzel, H.J. Co-targeting CDK2 and CDK4/6 overcomes resistance to aromatase and CDK4/6 inhibitors in ER+ breast cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2022, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.G.; Saba, N.F.; Teng, Y. The diverse functions of FAT1 in cancer progression: good, bad, or ugly? J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Degese, M.S.; Vitale-Cross, L.; Iglesias-Bartolome, R.; Valera, J.L.C.; Wang, Z.; Feng, X.; Yeerna, H.; Vadmal, V.; Moroishi, T.; Thorne, R.F.; Zaida, M.; Siegele, B.; Cheong, S.C.; Molinolo, A.A.; Samuels, Y.; Tamayo, P.; Guan, K.L.; Lippman, S.M.; Lyons, J.G.; Gutkind, J.S. Assembly and activation of the Hippo signalome by FAT1 tumor suppressor. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, A.A.; Gayyed, M.F.; Klein, A.P.; Dong, J.; Maitra, A.; Pan, D.; Montgomery, E.A.; Anders, R.A. Expression of Yes-associated protein in common solid tumors. Hum Pathol. 2008, 39, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, Y.; Brundage, J.; Allegakoen, P.; Shajahan-Haq, A.N. MYC-Driven Pathways in Breast Cancer Subtypes. Biomolecules. 2017, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.Y.; Li, X.T.; Xu, K.; Wang, R.T.; Guan, X.X. c-MYC mediates the crosstalk between breast cancer cells and tumor microenvironment. Cell Commun Signal. 2023, 21, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Park, N.; Park, K.S.; Hur, J.; Cho, Y.B.; Kang, M.; An, H.J.; Kim, S.; Hwang, S.; Moon, Y.W. Combined CDK2 and CDK4/6 Inhibition Overcomes Palbociclib Resistance in Breast Cancer by Enhancing Senescence. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, M.P.; Hamilton, E.P.; Campone, M.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Cortes, J.; Johnston, S.R.D.; Jerusalem, G.H.M.; Graham, H.; Wang, H.; Litchfield, L.; Jansen, V.M.; Martin, M. Acquired genomic alterations in circulating tumor DNA from patients receiving abemaciclib alone or in combination with endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38 (suppl), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.; Liu, X.; Xue, Y.; Chen, H.; Guo, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Han, J.; Fu, M.; Song, Y.; Li, D.; Ma, F. S6K1 amplification confers innate resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors through activating c-Myc pathway in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2022, 21, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroni, G.; Buqué, A.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Immunomodulation by targeted anticancer agents. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 310–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petroni, G.; Formenti, S.C.; Chen-Kiang, S.; Galluzzi, L. Immunomodulation by anticancer cell cycle inhibitors. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bu, X. Cyclin D-CDK4 kinase destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3-SPOP to control cancer immune surveillance. Nature 2018, 2018 553, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, J.L.F. Arrested developments: CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance and alterations in the tumor immune microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res 2019, 25(3), 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, C. Activation of the IFN signaling pathway is associated with resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors and immune checkpoint activation in ER-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27(17), 4870–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroni, G. IL17-Producing γδ T Cells Promote Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibitors in HR+HER2-Breast cancer. BMJ Specialist Journals, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaría, D.; Barrière, C.; Cerqueira, A.; Hunt, S.; Tardy, C.; Newton, K.; Cáceres, J.F.; Dubus, P.; Malumbres, M.; Barbacid, M. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature. 2007, 448, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman-Cook, K.D.; Hoffman, R.L.; Behenna, D.C.; Boras, B.; Carelli, J.; Diehl, W.; Ferre, R.A.; He, Y.A.; Hui, A.; Huang, B.; Huser, N.; Jones, R.; Kephart, S.E.; Lapek, J.; McTigue, M.; Miller, N.; Murray, B.W.; Nagata, A.; Nguyen, L.; Niessen, S.; Ninkovic, S.; O'Doherty, I.; Ornelas, M.A.; Solowiej, J.; Sutton, S.C.; Tran, K.; Tseng, E.; Visswanathan, R.; Xu, M.; Zehnder, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Dann, S. Discovery of PF-06873600, a CDK2/4/6 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Cancer. J Med Chem. 2021, 64, 9056–9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, M.; Moser, J.; Hoffman, T.E.; Watts, L.P.; Min, M.; Musteanu, M.; Rong, Y.; Ill, C.R.; Nangia, V.; Schneider, J.; Sanclemente, M.; Lapek, J.; Nguyen, L.; Niessen, S.; Dann, S.; VanArsdale, T.; Barbacid, M.; Miller, N.; Spencer, S.L. Rapid adaptation to CDK2 inhibition exposes intrinsic cell-cycle plasticity. Cell. 2023, 186, 2628–2643.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover-Cutter, K.; Larochelle, S.; Erickson, B.; Zhang, C.; Shokat, K.; Fisher, R.P.; Bentley, D.L. TFIIH-associated Cdk7 kinase functions in phosphorylation of C-terminal domain Ser7 residues, promoter-proximal pausing, and termination by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2009, 29, 5455–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombes, R.C.; Howell, S.; Lord, S.R.; Kenny, L.; Mansi, J.; Mitri, Z.; Palmieri, C.; Chap, L.I.; Richards, P.; Gradishar, W.; Sardesai, S.; Melear, J.; O'Shaughnessy, J.; Ward, P.; Chalasani, P.; Arkenau, T.; Baird, R.D.; Jeselsohn, R.; Ali, S.; Clack, G.; Bahl, A.; McIntosh, S.; Krebs, M.G. Dose escalation and expansion cohorts in patients with advanced breast cancer in a Phase I study of the CDK7-inhibitor samuraciclib. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 4444, Erratum in: Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A.; Vuina, K.; Sava, G.; Huard, C.; Meneguello, L.; Coulombe-Huntington, J.; Bertomeu, T.; Maizels, R.J.; Lauring, J.; Kriston-Vizi, J.; Tyers, M.; Ali, S.; Bertoli, C.; de Bruin, R.A.M. Active growth signaling promotes senescence and cancer cell sensitivity to CDK7 inhibition. Mol Cell. 2023, 83, 4078–4092.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzone, E.; Pagan, E.; Bagnardi, V.; Montagna, E.; Cancello, G.; Dellapasqua, S.; Iorfida, M.; Mazza, M.; Colleoni, M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of post-progression outcomes in ER+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer after CDK4/6 inhibitors within randomized clinical trials. ESMO Open. 2021, 6, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari A, ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 2021 32, 1475–1495.

- Di Leo, A.; Jerusalem, G.; Petruzelka, L.; Torres, R.; Bondarenko, I.N.; Khasanov, R.; Verhoeven, D.; Pedrini, J.L.; Smirnova, I.; Lichinitser, M.R.; Pendergrass, K.; Malorni, L.; Garnett, S.; Rukazenkov, Y.; Martin, M. Final overall survival: fulvestrant 500 mg vs 250 mg in the randomized CONFIRM trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, djt337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblum, N.; Zhao, F.; Manola, J.; Klein, P.; Ramaswamy, B.; Brufsky, A.; Stella, P.J.; Burnette, B.; Telli, M.; Makower, D.F.; Cheema, P.; Truica, C.I.; Wolff, A.C.; Soori, G.S.; Haley, B.; Wassenaar, T.R.; Goldstein, L.J.; Miller, K.D.; Sparano, J.A. Randomized Phase II Trial of Fulvestrant Plus Everolimus or Placebo in Postmenopausal Women With Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer Resistant to Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy: Results of PrE0102. J Clin Oncol. 2018, 36, 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Zaiss, M.; Harper-Wynne, C.; Ferreira, M.; Dubey, S.; Chan, S.; Makris, A.; Nemsadze, G.; Brunt, A.M.; Kuemmel, S.; Ruiz, I.; Perelló, A.; Kendall, A.; Brown, J.; Kristeleit, H.; Conibear, J.; Saura, C.; Grenier, J.; Máhr, K.; Schenker, M.; Sohn, J.; Lee, K.S.; Shepherd, C.J.; Oelmann, E.; Sarker, S.J.; Prendergast, A.; Marosics, P.; Moosa, A.; Lawrence, C.; Coetzee, C.; Mousa, K.; Cortés, J. Fulvestrant Plus Vistusertib vs Fulvestrant Plus Everolimus vs Fulvestrant Alone for Women With Hormone Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer: The MANTA Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1556–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinsky, K.; Accordino, M.K.; Chiuzan, C.; Mundi, P.S.; Sakach, E.; Sathe, C.; Ahn, H.; Trivedi, M.S.; Novik, Y.; Tiersten, A.; Raptis, G.; Baer, L.N.; Oh, S.Y.; Zelnak, A.B.; Wisinski, K.B.; Andreopoulou, E.; Gradishar, W.J.; Stringer-Reasor, E.; Reid, S.A.; O'Dea, A.; O'Regan, R.; Crew, K.D.; Hershman, D.L. Randomized Phase II Trial of Endocrine Therapy With or Without Ribociclib After Progression on Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibition in Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer: MAINTAIN Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41, 4004–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeman, G.J.; Fernando, T.M.; Bowen, R.; Jerzak, K.J.; Song, X.; Decker, T.; Boyle, F.; McCune, S.; Armstrong, A.; Shannon, C.; Bertelli, G.; Chang, C.W.; Desai, R.; Gupta, K.; Wilson, T.R.; Flechais, A.; Bardia, A. VERONICA: Randomized Phase II Study of Fulvestrant and Venetoclax in ER-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Post-CDK4/6 Inhibitors - Efficacy, Safety, and Biomarker Results. Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 3256–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidard, F.C.; Hardy-Bessard, A.C.; Dalenc, F.; Bachelot, T.; Pierga, J.Y.; de la Motte Rouge, T.; Sabatier, R.; Dubot, C.; Frenel, J.S.; Ferrero, J.M.; Ladoire, S.; Levy, C.; Mouret-Reynier, M.A.; Lortholary, A.; Grenier, J.; Chakiba, C.; Stefani, L.; Plaza, J.E.; Clatot, F.; Teixeira, L.; D'Hondt, V.; Vegas, H.; Derbel, O.; Garnier-Tixidre, C.; Canon, J.L.; Pistilli, B.; André, F.; Arnould, L.; Pradines, A.; Bièche, I.; Callens, C.; Lemonnier, J.; Berger, F.; Delaloge, S.; PADA-1 investigators. Switch to fulvestrant and palbociclib versus no switch in advanced breast cancer with rising ESR1 mutation during aromatase inhibitor and palbociclib therapy (PADA-1): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidard, F.C.; Kaklamani, V.G.; Neven, P.; Streich, G.; Montero, A.J.; Forget, F.; Mouret-Reynier, M.A.; Sohn, J.H.; Taylor, D.; Harnden, K.K.; Khong, H.; Kocsis, J.; Dalenc, F.; Dillon, P.M.; Babu, S.; Waters, S.; Deleu, I.; García Sáenz, J.A.; Bria, E.; Cazzaniga, M.; Lu, J.; Aftimos, P.; Cortés, J.; Liu, S.; Tonini, G.; Laurent, D.; Habboubi, N.; Conlan, M.G.; Bardia, A. Elacestrant (oral selective estrogen receptor degrader) Versus Standard Endocrine Therapy for Estrogen Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Results From the Randomized Phase III EMERALD Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022, 40, 3246–3256, Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardia, A.; Cortés, J.; Bidard, F.C.; Neven, P.; Garcia-Sáenz, J.; Aftimos, P.; O'Shaughnessy, J.; Lu, J.; Tonini, G.; Scartoni, S.; Paoli, A.; Binaschi, M.; Wasserman, T.; Kaklamani, V. Elacestrant in ER+, HER2- Metastatic Breast Cancer with ESR1-Mutated Tumors: Subgroup Analyses from the Phase III EMERALD Trial by Prior Duration of Endocrine Therapy plus CDK4/6 Inhibitor and in Clinical Subgroups. Clin Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 4299–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; O'Shaughnessy, J.; Cortes, J.; et al. Elacestrant in various combinations in patients (pts) with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+), HER2-negative (HER2-) locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (adv/mBC): Preliminary data from ELEVATE, a phase 1b/2, open-label, umbrella study. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl 16), 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Pominchuk, D.; Nowecki, Z.; Hamilton, E.; Kulyaba, Y.; Andabekov, T.; Hotko, Y.; Melkadze, T.; Nemsadze, G.; Neven, P.; Vladimirov, V.; Zamagni, C.; Denys, H.; Forget, F.; Horvath, Z.; Nesterova, A.; Ajimi, M.; Kirova, B.; Klinowska, T.; Lindemann, J.P.O.; Lissa, D.; Mathewson, A.; Morrow, C.J.; Traugottova, Z.; van Zyl, R.; Arkania, E. Camizestrant, a next-generation oral SERD, versus fulvestrant in post-menopausal women with oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer (SERENA-2): a multi-dose, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 1424–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Huang-Bartlett, C.; Kalinsky, K.; Cristofanilli, M.; Bianchini, G.; Chia, S.; Iwata, H.; Janni, W.; Ma, C.X.; Mayer, E.L.; Park, Y.H.; Fox, S.; Liu, X.; McClain, S.; Bidard, F.C. Design of SERENA-6, a phase III switching trial of camizestrant in ESR1-mutant breast cancer during first-line treatment. Future Oncol. 2023, 19, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, K.L.; Neven, P.; Casalnuovo, M.L.; Kim, S.B.; Tokunaga, E.; Aftimos, P.; Saura, C.; O'Shaughnessy, J.; Harbeck, N.; Carey, L.A.; Curigliano, G.; Llombart-Cussac, A.; Lim, E.; García Tinoco, M.L.; Sohn, J.; Mattar, A.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, C.S.; Hung, C.C.; Martinez Rodriguez, J.L.; Ruíz Borrego, M.; Nakamura, R.; Pradhan, K.R.; Cramer von Laue, C.; Barrett, E.; Cao, S.; Wang, X.A.; Smyth, L.M.; Bidard, F.C.; EMBER-3 Study Group. Imlunestrant with or without Abemaciclib in Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Zbieg, J.R.; Blake, R.A.; Chang, J.H.; Daly, S.; DiPasquale, A.G.; Friedman, L.S.; Gelzleichter, T.; Gill, M.; Giltnane, J.M.; Goodacre, S.; Guan, J.; Hartman, S.J.; Ingalla, E.R.; Kategaya, L.; Kiefer, J.R.; Kleinheinz, T.; Labadie, S.S.; Lai, T.; Li, J.; Liao, J.; Liu, Z.; Mody, V.; McLean, N.; Metcalfe, C.; Nannini, M.A.; Oeh, J.; O'Rourke, M.G.; Ortwine, D.F.; Ran, Y.; Ray, N.C.; Roussel, F.; Sambrone, A.; Sampath, D.; Schutt, L.K.; Vinogradova, M.; Wai, J.; Wang, T.; Wertz, I.E.; White, J.R.; Yeap, S.K.; Young, A.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, X. GDC-9545 (Giredestrant): A Potent and Orally Bioavailable Selective Estrogen Receptor Antagonist and Degrader with an Exceptional Preclinical Profile for ER+ Breast Cancer. J Med Chem. 2021, 64, 11841–11856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; Lim, E.; Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Bardia, A.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Nowecki, Z.; Cruz, F.M.; Safin, R.; Kim, S.B.; Schem, C.; Montero, A.J.; Khan, S.; Bandyopadhyay, R.; Moore, H.M.; Shivhare, M.; Patre, M.; Martinalbo, J.; Roncoroni, L.; Pérez-Moreno, P.D.; Sohn, J.; acelERA Breast Cancer Study Investigators. Giredestrant for Estrogen Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative, Previously Treated Advanced Breast Cancer: Results From the Randomized, Phase II acelERA Breast Cancer Study. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42, 2149–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, A.; Varadi, M.; Carrasco, D.; Li, H.; Luongo, L.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Cho, E.Y.; Lewis, G.; Kehoe, S.; Iglehart, J.D.; Dillon, D.; Allred, D.C.; Macconaill, L.; Gelman, R.; Polyak, K. PIK3CA mutations in in situ and invasive breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 5674–5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, F.; Ciruelos, E.M.; Juric, D.; Loibl, S.; Campone, M.; Mayer, I.A.; Rubovszky, G.; Yamashita, T.; Kaufman, B.; Lu, Y.S.; Inoue, K.; Pápai, Z.; Takahashi, M.; Ghaznawi, F.; Mills, D.; Kaper, M.; Miller, M.; Conte, P.F.; Iwata, H.; Rugo, H.S. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-negative advanced breast cancer: final overall survival results from SOLAR-1. Ann Oncol. 2021, 32, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Lerebours, F.; Ciruelos, E.; Drullinsky, P.; Ruiz-Borrego, M.; Neven, P.; Park, Y.H.; Prat, A.; Bachelot, T.; Juric, D.; Turner, N.; Sophos, N.; Zarate, J.P.; Arce, C.; Shen, Y.M.; Turner, S.; Kanakamedala, H.; Hsu, W.C.; Chia, S. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant in PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer after a CDK4/6 inhibitor (BYLieve): one cohort of a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-comparative study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 489–498, Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugo, H.S.; et al. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant in PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer after a CDK4/6 inhibitor (BYLieve): one cohort of a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-comparative study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, E.; Kataoka, A.; Kimura, Y.; Oki, E.; Mashino, K.; Nishida, K.; Koga, T.; Morita, M.; Kakeji, Y.; Baba, H.; Ohno, S.; Maehara, Y. The association between Akt activation and resistance to hormone therapy in metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2006, 42, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, S.J.; Casbard, A.; Carucci, M.; Ingarfield, K.; Butler, R.; Morgan, S.; Meissner, M.; Bale, C.; Bezecny, P.; Moon, S.; Twelves, C.; Venkitaraman, R.; Waters, S.; de Bruin, E.C.; Schiavon, G.; Foxley, A.; Jones, R.H. Fulvestrant plus capivasertib versus placebo after relapse or progression on an aromatase inhibitor in metastatic, oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer (FAKTION): overall survival, updated progression-free survival, and expanded biomarker analysis from a randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 851–864. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.C.; Oliveira, M.; Howell, S.J.; Dalenc, F.; Cortes, J.; Gomez Moreno, H.L.; Hu, X.; Jhaveri, K.; Krivorotko, P.; Loibl, S.; Morales Murillo, S.; Okera, M.; Park, Y.H.; Sohn, J.; Toi, M.; Tokunaga, E.; Yousef, S.; Zhukova, L.; de Bruin, E.C.; Grinsted, L.; Schiavon, G.; Foxley, A.; Rugo, H.S.; CAPItello-291 Study Group. Capivasertib in Hormone Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 2058–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.C.; Im, S.A.; Saura, C.; Juric, D.; Loibl, S.; Kalinsky, K.; Schmid, P.; Loi, S.; Sunpaweravong, P.; Musolino, A.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Nowecki, Z.; Leung, R.; Thanopoulou, E.; Shankar, N.; Lei, G.; Stout, T.J.; Hutchinson, K.E.; Schutzman, J.L.; Song, C.; Jhaveri, K.L. Inavolisib-Based Therapy in PIK3CA-Mutated Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024, 391, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.; Bardia, A.; Kim, S.B.N.; et al. Ipatasertib in combination with palbociclib (palbo) and fulvestrant (fulv) in patients with hormone receptor-positive HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. Cancer Res 2022, 82 (4 Suppl), P5-16-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccart, M.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Campone, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Lebrun, F.; Ito, Y.; Noguchi, S.; Perez, A.; Rugo, H.S.; Deleu, I.; Burris HA3rd Provencher, L.; Neven, P.; Gnant, M.; Shtivelband, M.; Wu, C.; Fan, J.; Feng, W.; Taran, T.; Baselga, J. Everolimus plus exemestane for hormone-receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-negative advanced breast cancer: overall survival results from BOLERO-2. Ann Oncol. 2014, 25, 2357–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, A.; Antony Thomas, R.; Levine, E.G.; Brufsky, A.; Takabe, K.; Hanna, M.G.; Attwood, K.; Miller, A.; Khoury, T.; Early, A.P.; Soniwala, S.; O'Connor, T.; Opyrchal, M. Outcome of Everolimus-Based Therapy in Hormone-Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients After Progression on Palbociclib. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2020, 2020 14, 1178223420944864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.M.; Al Rabadi, L.; Kaempf, A.J.; Saraceni, M.M.; Savin, M.A.; Mitri, Z.I. Everolimus Plus Exemestane Treatment in Patients with Metastatic Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Previously Treated with CDK4/6 Inhibitor Therapy. Oncologist. 2021, 26, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, R.M.; Han, H.S.; Rugo, H.S.; Stringer-Reasor, E.M.; Specht, J.M.; Dees, E.C.; Kabos, P.; Suzuki, S.; Mutka, S.C.; Sullivan, B.F.; Gorbatchevsky, I.; Wesolowski, R. Gedatolisib in combination with palbociclib and endocrine therapy in women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer: results from the dose expansion groups of an open-label, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumontet, C.; Reichert, J.M.; Senter, P.D.; Lambert, J.M.; Beck, A. Antibody-drug conjugates come of age in oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinda, T.; Rassy, E.; Pistilli, B. Antibody-Drug Conjugate Revolution in Breast Cancer: The Road Ahead. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2023, 24, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudacher, A.H.; Brown, M.P. Antibody drug conjugates and bystander killing: is antigen-dependent internalisation required? Br J Cancer. 2017, 117, 1736–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Jacot, W.; Yamashita, T.; Sohn, J.; Vidal, M.; Tokunaga, E.; Tsurutani, J.; Ueno, N.T.; Prat, A.; Chae, Y.S.; Lee, K.S.; Niikura, N.; Park, Y.H.; Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Gil-Gil, M.; Li, W.; Pierga, J.Y.; Im, S.A.; Moore, H.C.F.; Rugo, H.S.; Yerushalmi, R.; Zagouri, F.; Gombos, A.; Kim, S.B.; Liu, Q.; Luo, T.; Saura, C.; Schmid, P.; Sun, T.; Gambhire, D.; Yung, L.; Wang, Y.; Singh, J.; Vitazka, P.; Meinhardt, G.; Harbeck, N.; Cameron, D.A.; DESTINY-Breast04 Trial Investigators. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Low Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022, 387, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardia, A.; Hu, X.; Dent, R.; Yonemori, K.; Barrios, C.H.; O'Shaughnessy, J.A.; Wildiers, H.; Pierga, J.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Saura, C.; Biganzoli, L.; Sohn, J.; Im, S.A.; Lévy, C.; Jacot, W.; Begbie, N.; Ke, J.; Patel, G.; Curigliano, G.; DESTINY-Breast06 Trial Investigators. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan after Endocrine Therapy in Metastatic Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024, 391, 2110–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curigliano, G.; Hu, T.X.; Dent, R.A.; Yonemori, K.; Barrios CHSr O'Shaughnessy, J.; et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) vs physician’s choice of chemotherapy (TPC) in patients (pts) with hormone receptor-positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-low or HER2-ultralow metastatic breast cancer (mBC) with prior endocrine therapy (ET): Primary results from DESTINY-Breast06 (DB-06). J Clin Oncol 2024, 42 (suppl 17), abstr LBA1000. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, Y.Y. Sacituzumab Govitecan: First Approval. Drugs. 2020, 80, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidula, N.; Yau, C.; Rugo, H. Trophoblast Cell Surface Antigen 2 gene (TACSTD2) expression in primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022, 194, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Bardia, A.; Marmé, F.; Cortes, J.; Schmid, P.; Loirat, D.; Trédan, O.; Ciruelos, E.; Dalenc, F.; Pardo, P.G.; Jhaveri, K.L.; Delaney, R.; Fu, O.; Lin, L.; Verret, W.; Tolaney, S.M. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Hormone Receptor-Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022, 40, 3365–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugo, H.; Bardia, A.; Marmé, F.; Cortés, J.; Schmid, P.; Loirat, D.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan (SG) vs Treatment of Physician’s Choice (TPC): Efficacy by Trop-2 Expression in the TROPiCS-02 Study of Patients (Pts) With HR+/HER2– Metastatic Breast Cancer (mBC). Cancer Res 2023, 83 (5_Supplement), GS1-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Krop, I.; Juric, D.; Kogawa, T.; Hamilton, E.; Spira, A.I.; et al. Phase 1 TROPION-PanTumor01 Study Evaluating Datopotamab Deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) in Unresectable or Metastatic Hormone Receptor–Positive/HER2–Negative Breast Cancer (BC). Cancer Res 2023, 83 (5_Supplement), PD13-08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardia, A.; Jhaveri, K.; Im, S.A.; De Laurentiis, M.; Xu, B.; Pernas, S.; et al. Randomized phase 3 study of datopotamab deruxtecan vs chemotherapy for patients with previously-treated inoperable or metastatic hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer: Results from TROPION-Breast01. Cancer Res 2024, 84 (9_Supplement), GS02-01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardia, A.; Jhaveri, K.; Im, S.A.; Pernas, S.; De Laurentiis, M.; Wang, S.; Martínez Jañez, N.; Borges, G.; Cescon, D.W.; Hattori, M.; Lu, Y.S.; Hamilton, E.; Zhang, Q.; Tsurutani, J.; Kalinsky, K.; Rubini Liedke, P.E.; Xu, L.; Fairhurst, R.M.; Khan, S.; Denduluri, N.; Rugo, H.S.; Xu, B.; Pistilli, B.; TROPION-Breast01 Investigators. Datopotamab Deruxtecan Versus Chemotherapy in Previously Treated Inoperable/Metastatic Hormone Receptor-Positive Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Breast Cancer: Primary Results From TROPION-Breast01. J Clin Oncol. 2024, JCO2400920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.L.; Ren, Y.; Wagle, N.; Mahtani, R.; Ma, C.; DeMichele, A.; Cristofanilli, M.; Meisel, J.; Miller, K.D.; Abdou, Y.; Riley, E.C.; Qamar, R.; Sharma, P.; Reid, S.; Sinclair, N.; Faggen, M.; Block, C.C.; Ko, N.; Partridge, A.H.; Chen, W.Y.; DeMeo, M.; Attaya, V.; Okpoebo, A.; Alberti, J.; Liu, Y.; Gauthier, E.; Burstein, H.J.; Regan, M.M.; Tolaney, S.M. PACE: A Randomized Phase II Study of Fulvestrant, Palbociclib, and Avelumab After Progression on Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitor and Aromatase Inhibitor for Hormone Receptor-Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42, 2050–2060. [Google Scholar]

- Llombart Cussac, A.; Harper-Wynne, C.; Perello, A.; Hennequin, A.; Fernandez, A.; Colleoni, M. Second-line endocrine therapy (ET) with or without palbociclib (P) maintenance in patients (pts) with hormone receptor-positive (HR[+])/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2[-]) advanced breast cancer (ABC): PALMIRA trial. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41 (suppl 16), abstr 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinski, K.; Bianchini, G.; Hamilton, E.P.; Graff, S.L.; Park, K.H.; Jeselsohn, R.; Demirci, U.; Martin, M.; Layman, R.M.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Sammons, S.L.; Kaufman, P.A.; Muñoz, M.; Tseng, L.M.; Knoderer, H.; Nguyen, B.; Zhou, Y.; Ravenberg, E.; Litchfield, L.M.; Wander, S.A. Abemaciclib plus fulvestrant vs fulvestrant alone for HR+, HER2- advanced breast cancer following progression on a prior CDK4/6 inhibitor plus endocrine therapy: Primary outcome of the phase 3 postMONARCH trial. J Clin Oncol 1001, 42 (suppl 17), abstr LBA1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, F.; Karikalan, S.A.; Batalini, F.; El Masry, A.; Mina, L. Metastatic ER+ Breast Cancer: Mechanisms of Resistance and Future Therapeutic Approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 16198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.; Klein, P.; Tiersten, A.; Sparano, J.A. An emerging generation of endocrine therapies in breast cancer: a clinical perspective. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2023, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisian, A.D.; Barratt, S.A.; Hodges-Gallagher, L.; Ortega, F.E.; Peña, G.; Sapugay, J.; Robello, B.; Sun, R.; Kulp, D.; Palanisamy, G.S.; Myles, D.C.; Kushner, P.J.; Harmon, C.L. Palazestrant (OP-1250), A Complete Estrogen Receptor Antagonist, Inhibits Wild-type and Mutant ER-positive Breast Cancer Models as Monotherapy and in Combination. Mol Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainé, M.; Greene, M.E.; Kurleto, J.D.; Bozek, G.; Leng, T.; Huggins, R.J.; Komm, B.S.; Greene, G.L. Lasofoxifene as a potential treatment for aromatase inhibitor-resistant ER-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, M.P.; Bagegni, N.A.; Batist, G.; Brufsky, A.; Cristofanilli, M.A.; Damodaran, S.; Daniel, B.R.; Fleming, G.F.; Gradishar, W.J.; Graff, S.L.; Grosse Perdekamp, M.T.; Hamilton, E.; Lavasani, S.; Moreno-Aspitia, A.; O'Connor, T.; Pluard, T.J.; Rugo, H.S.; Sammons, S.L.; Schwartzberg, L.S.; Stover, D.G.; Vidal, G.A.; Wang, G.; Warner, E.; Yerushalmi, R.; Plourde, P.V.; Portman, D.J.; Gal-Yam, E.N. Lasofoxifene versus fulvestrant for ER+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer with an ESR1 mutation: results from the randomized, phase II ELAINE 1 trial. Ann Oncol. 2023, 34, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, S.; O'Sullivan, C.C.; Elkhanany, A.; Anderson, I.C.; Barve, M.; Blau, S.; Cherian, M.A.; Peguero, J.A.; Goetz, M.P.; Plourde, P.V.; Portman, D.J.; Moore, H.C.F. Open-label, phase II, multicenter study of lasofoxifene plus abemaciclib for treating women with metastatic ER+/HER2- breast cancer and an ESR1 mutation after disease progression on prior therapies: ELAINE 2. Ann Oncol. 2023, 34, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, M.P.; Wander, S.A.; Bachelot, T.; et al. Open-label, randomized, multicenter, phase 3, ELAINE 3 study of the efficacy and safety of lasofoxifene plus abemaciclib for treating ER+/HER2-, locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer with an ESR1 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42 S16, TPS1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, S.W.; Jeselsohn, R.; Dharmarajan, V.; Mayne, C.G.; Karimi, M.; Buchwalter, G.; Houtman, R.; Toy, W.; Fowler, C.E.; Han, R.; Lainé, M.; Carlson, K.E.; Martin, T.A.; Nowak, J.; Nwachukwu, J.C.; Hosfield, D.J.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Nettles, K.W.; Griffin, P.R.; Shen, Y.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Brown, M.; Greene, G.L. The SERM/SERD bazedoxifene disrupts ESR1 helix 12 to overcome acquired hormone resistance in breast cancer cells. Elife. 2018, 2018 7, e37161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, J.; Li, T.; Grinshpun, A.; Coorens, T.; Russo, D.; Anderson, L.; Rees, R.; Nardone, A.; Patterson, C.; Lennon, N.J.; Cibulskis, C.; Leshchiner, I.; Tayob, N.; Tolaney, S.M.; Tung, N.; McDonnell, D.P.; Krop, I.E.; Winer, E.P.; Stewart, C.; Getz, G.; Jeselsohn, R. Clinical Efficacy and Whole-Exome Sequencing of Liquid Biopsies in a Phase IB/II Study of Bazedoxifene and Palbociclib in Advanced Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 5066–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, C.; Puyang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.J.; Banka, D.; Aithal, K.B.; Albacker, L.A.; Hao, M.H.; Irwin, S.; Kim, A.; Montesion, M.; Moriarty, A.D.; Murugesan, K.; Nguyen, T.V.; Rimkunas, V.; Sahmoud, T.; Wick, M.J.; Yao, S.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, H.; Vaillancourt, F.H.; Bolduc, D.M.; Larsen, N.; Zheng, G.Z.; Prajapati, S.; Zhu, P.; Korpal, M. Covalent ERα Antagonist H3B-6545 Demonstrates Encouraging Preclinical Activity in Therapy-Resistant Breast Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.P.; Wang, J.S.; Pluard, T.; et al. H3B-6545, a novel selective estrogen receptor covalent antagonist (SERCA), in estrogen receptor positive (ER+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative (HER2-) advanced breast cancer—A phase II study. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, P1-17-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Patel, H.K.; Gutgesell, L.M.; Zhao, J.; Delgado-Rivera, L.; Pham, T.N.D.; Zhao, H.; Carlson, K.; Martin, T.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Moore, T.W.; Tonetti, D.A.; Thatcher, G.R.J. Selective Human Estrogen Receptor Partial Agonists (ShERPAs) for Tamoxifen-Resistant Breast Cancer. J Med Chem. 2016, 59, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, A.Z.; Liu, L.C.; Fischer, J.H.; et al. , Phase 1 study of TTC-352 in patients with metastatic breast cancer progressing on endocrine and CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020, 183, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondeson, D.P.; Mares, A.; Smith, I.E.; Ko, E.; Campos, S.; Miah, A.H.; Mulholland, K.E.; Routly, N.; Buckley, D.L.; Gustafson, J.L.; Zinn, N.; Grandi, P.; Shimamura, S.; Bergamini, G.; Faelth-Savitski, M.; Bantscheff, M.; Cox, C.; Gordon, D.A.; Willard, R.R.; Flanagan, J.J.; Casillas, L.N.; Votta, B.J.; den Besten, W.; Famm, K.; Kruidenier, L.; Carter, P.S.; Harling, J.D.; Churcher, I.; Crews, C.M. Catalytic in vivo protein knockdown by small-molecule PROTACs. Nat Chem Biol. 2015, 11, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, L.B.; Flanagan, J.J.; Qian, Y.; et al. The discovery of ARV-471, an orally bioavailable estrogen receptor degrading PROTAC for the treatment of patients with breast cancer. AACR Meeting 2021. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.; Vahdat, L.; Han, H.; et al. First-in-human safety and activity of ARV-471, a novel PROTAC® estrogen receptor degrader, in ER+/HER2- locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, PD13-08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, A.F.; Hurvitz, S.; Ma, C.; et al. GS3-03 ARV-471, a PROTAC® estrogen receptor (ER) degrader in advanced ER-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative breast cancer: phase 2 expansion (VERITAC) of a phase 1/2 study. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, GS3-03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.; Jeselsohn, R.; Hurvitz, S.; et al. Hamilton E, Jeselsohn R, Hurvitz S, et al. Vepdegestrant, a PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera (PROTAC) estrogen receptor (ER) degrader, plus palbociclib in ER–positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative advanced breast cancer: phase 1b cohort. Cancer Res. 2024, 84 (Suppl. S9), PS15-03. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, S.M.; Flanagan, J.J.; Teh, J.; Andreoli, M.; Rousseau, E.; Pannone, M.; Bookbinder, M.; Willard, R.; Davenport, K.; Bortolon, E.; Cadelina, G.; Gordon, D.; Pizzano, J.; Macaluso, J.; Soto, L.; Corradi, J.; Digianantonio, K.; Drulyte, I.; Morgan, A.; Quinn, C.; Békés, M.; Ferraro, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, G.; Dong, H.; Wang, J.; Langley, D.R.; Houston, J.; Gedrich, R.; Taylor, I.C. Oral Estrogen Receptor PROTAC Vepdegestrant (ARV-471) Is Highly Efficacious as Monotherapy and in Combination with CDK4/6 or PI3K/mTOR Pathway Inhibitors in Preclinical ER+ Breast Cancer Models. Clin Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 3549–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardelli, C.; Bianco-Miotto, T.; Jindal, S.; Butler, L.M.; Leung, S.; McNeil, C.M.; O'Toole, S.A.; Ebrahimie, E.; Millar, E.K.A.; Sakko, A.J.; Ruiz, A.I.; Vowler, S.L.; Huntsman, D.G.; Birrell, S.N.; Sutherland, R.L.; Palmieri, C.; Hickey, T.E.; Tilley, W.D. The Magnitude of Androgen Receptor Positivity in Breast Cancer Is Critical for Reliable Prediction of Disease Outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 2328–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, T.E.; Selth, L.A.; Chia, K.M.; Laven-Law, G.; Milioli, H.H.; Roden, D.; Jindal, S.; Hui, M.; Finlay-Schultz, J.; Ebrahimie, E.; Birrell, S.N.; Stelloo, S.; Iggo, R.; Alexandrou, S.; Caldon, C.E.; Abdel-Fatah, T.M.; Ellis, I.O.; Zwart, W.; Palmieri, C.; Sartorius, C.A.; Swarbrick, A.; Lim, E.; Carroll, J.S.; Tilley, W.D. The androgen receptor is a tumor suppressor in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Med. 2021, 27, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.F.; Karami, S.; Peidl, A.S.; Waiters, K.D.; Babajide, M.F.; Bawa-Khalfe, T. Androgen Receptor in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 25, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krop, I.; Abramson, V.; Colleoni, M.; Traina, T.; Holmes, F.; Garcia-Estevez, L.; Hart, L.; Awada, A.; Zamagni, C.; Morris, P.G.; Schwartzberg, L.; Chan, S.; Gucalp, A.; Biganzoli, L.; Steinberg, J.; Sica, L.; Trudeau, M.; Markova, D.; Tarazi, J.; Zhu, Z.; O'Brien, T.; Kelly, C.M.; Winer, E.; Yardley, D.A. A Randomized Placebo Controlled Phase II Trial Evaluating Exemestane with or without Enzalutamide in Patients with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 6149–6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Gao, H.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Nguyen, T.T.L.; Gu, Y.; Passow, M.R.; Carter, J.M.; Qin, B.; Boughey, J.C.; Goetz, M.P.; Weinshilboum, R.M.; Ingle, J.N.; Wang, L. Pharmacological Targeting of Androgen Receptor Elicits Context-Specific Effects in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, C.; Linden, H.M.; Birrell, S.; et al. Palmieri C, Linden HM, Birrell S, et al. Efficacy of enobosarm, a selective androgen receptor (AR) targeting agent, correlates with the degree of AR positivity in advanced AR+/estrogen receptor (ER)+ breast cancer in an international phase 2 clinical study. J Clin Oncol 2021, 39, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn, K.; Linden, H.; Schwartzberg, L.; et al. Design of Active Phase 3 ENABLAR-2 Study Evaluating Enobosarm +/- Abemaciclib in Patients with AR+ER+HER2- 2nd-Line Metastatic Breast Cancer Following Tumor Progression on an Estrogen Blocking Agent Plus Palbociclib or Ribociclib. Cancer Res 2024, 84 (9_Supplement, PO4-27-06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Fang, C.; Dai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, C.; Lin, X.; Xu, R. Cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (CDK7) inhibitors as a novel therapeutic strategy for different molecular types of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2024, 130, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarducci, C.; Nardone, A.; Russo, D.; Nagy, Z.; Heraud, C.; Grinshpun, A.; Zhang, Q.; Freelander, A.; Leventhal, M.J.; Feit, A.; Cohen Feit, G.; Feiglin, A.; Liu, W.; Hermida-Prado, F.; Kesten, N.; Ma, W.; De Angelis, C.; Morlando, A.; O'Donnell, M.; Naumenko, S.; Huang, S.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Huang, Y.; Malorni, L.; Bergholz, J.S.; Zhao, J.J.; Fraenkel, E.; Lim, E.; Schiff, R.; Shapiro, G.I.; Jeselsohn, R. Selective CDK7 Inhibition Suppresses Cell Cycle Progression and MYC Signaling While Enhancing Apoptosis in Therapy-resistant Estrogen Receptor-positive Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 1889–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Kwiatkowski, N.; Abraham, B.J.; Lee, T.I.; Xie, S.; Yuzugullu, H.; Von, T.; Li, H.; Lin, Z.; Stover, D.G.; Lim, E.; Wang, Z.C.; Iglehart, J.D.; Young, R.A.; Gray, N.S.; Zhao, J.J. CDK7-dependent transcriptional addiction in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell. 2015, 163, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, H.; Periyasamy, M.; Sava, G.P.; Bondke, A.; Slafer, B.W.; Kroll, S.H.B.; Barbazanges, M.; Starkey, R.; Ottaviani, S.; Harrod, A.; Aboagye, E.O.; Buluwela, L.; Fuchter, M.J.; Barrett, A.G.M.; Coombes, R.C.; Ali, S. ICEC0942, an Orally Bioavailable Selective Inhibitor of CDK7 for Cancer Treatment. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.R.; Juric, D.; Henick, B.S.; et al. BLU-222, an oral, potent, and selective CDK2 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors: Phase 1 monotherapy dose escalation. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41 (suppl 16), abstr 3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Elhaddad, A.M.; Grisham, R.N.; et al. First-in-human phase 1/2a study of a potent and novel CDK2-selective inhibitor PF-07104091 in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors, enriched for CDK4/6 inhibitor resistant HR+/HER2- breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41 16s, abstr 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.; Qiao, N.; Guerriero, J.L.; Gross, B.; Meneksedag, Y.; Lu, Y.F.; Philips, A.V.; Rahman, T.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Roszik, J.; Chen, K.; Jeselsohn, R.; Tolaney, S.M.; Peoples, G.E.; Alatrash, G.; Mittendorf, E.A. Estrogen Receptor Mutations as Novel Targets for Immunotherapy in Metastatic Estrogen Receptor-positive Breast Cancer. Cancer Res Commun. 2024, 4, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dailey, G.P.; Rabiola, C.A.; Lei, G.; Wei, J.; Yang, X.Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, C.X.; Gajda, M.; Hobeika, A.C.; Summers, A.; Marek, R.D.; Morse, M.A.; Lyerly, H.K.; Crosby, E.J.; Hartman, Z.C. Vaccines targeting ESR1 activating mutations elicit anti-tumor immune responses and suppress estrogen signaling in therapy resistant ER+ breast cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2024, 20, 2309693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, A.; Carpi, A. Beta-interferon and interleukin-2 prolong more than three times the survival of 26 consecutive endocrine dependent breast cancer patients with distant metastases: an exploratory trial. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005, 59, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, A.; Carpi, A.; Ferrari, P.; Biava, P.M.; Rossi, G. Immunotherapy and Hormone-therapy in Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Review and an Update. Curr Drug Targets. 2016, 17, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, A.; Rossi, G.; Ferrari, P.; Morganti, R.; Carpi, A. A new immunotherapy schedule in addition to first-line hormone therapy for metastatic breast cancer patients in a state of clinical benefit during hormone therapy. J Mol Med (Berl). 2020, 98, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, A.; Rossi, G.; Ferrari, P.; Morganti, R.; Carpi, A. Final results of a 2:1 control–case observational study using interferon beta and interleukin-2, in addition to first-line hormone therapy, in estrogen receptor-positive, endocrine-responsive metastatic breast cancer patients. J Cancer Metastasis Treat 2022, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, R.; Ahmed, A.; Wei, L.; Saeed, H.; Islam, M.; Ishaq, M. The anticancer potential of chemical constituents of Moringa oleifera targeting CDK-2 inhibition in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer using in-silico and in vitro approches. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023, 23, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandithar, S.; Galke, D.; Akume, A.; Belyakov, A.; Lomonaco, D.; Guerra, A.A.; Park, J.; Reff, O.; Jin, K. The role of CXCL1 in crosstalk between endocrine resistant breast cancer and fibroblast. Mol Biol Rep. 2024, 51, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastò, B.; Vida, R.; Dri, A.; Foffano, L.; Della Rossa, S.; Gerratana, L.; Puglisi, F. Beyond Hormone Receptors: liquid biopsy tools to unveil new clinical meanings and empower therapeutic decision-making in Luminal-like metastatic breast cancer. Breast. 2024, 79, 103859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foffano, L.; Cucciniello, L.; Nicolò, E.; Migliaccio, I.; Noto, C.; Reduzzi, C.; Malorni, L.; Cristofanilli, M.; Gerratana, L.; Puglisi, F. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i): Mechanisms of resistance and where to find them. Breast. 2024 79, 103863. [CrossRef]

- Fusco, N.; Malapelle, U. Next-generation sequencing for PTEN testing in HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2025, 207, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| A) continues | ||||||

| Study (phase) | Therapy | Setting | Main endpoints | Reference | ||

| CONFIRM (III) | Fulvestrant 500 mg vs 250 mg | Postmenopausal MBC women progressing on ET | mPFS 6.5 months mOS 26.4 months |

122 | ||

| MAINTAIN (Control arm) | Fulvestrant 500 mg | ABC patients, progressed on ET plus a CDK4/6i | mPFS 2.76 months | 125 | ||

| VERONICA (Control arm) |

Fulvestrant 500 mg | MBC patients, post CDK4/6i progression | m PFS 1.94 months | 126 | ||

| EMERALD (III) | Elacestrant vs standard ET | ABC patients after 1-2 lines of ET including a CDK4/6i, and ≤ 1 chemotherapy | 6-month PFS rate: 34.3% vs 20.4% in all patients; 40.8% vs 19.1%, in patients with ESR1 mutation. 12-month PFS rate: 22.3% vs 9.4% in all patients; 26.8% and 8.2% in patients with ESR1 mutation |

128 | ||

| ELEVATE (Ib/II) | Elacestrant in combination with alpelisib, or capivasertib, or everolimus, or palbociclib, or abemaciclib, or ribociclib | ABC/MBC, progressing on one or up to two prior lines of ET (inclusion criteria differ in every study arm) | Primary: PFS, safety Secondary: ORR, DOR, CBR, OS |

130 | ||

| ADELA (III) | Elacestrant plus everolimus vs elacestrant alone | ABC patients with ESR1-mutated tumors progressing on ET plus CDK4/6i | Primary: PFS Secondary: OS, ORR, CBR, DOR, safety and quality of life |

NCT06382948 | ||