Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

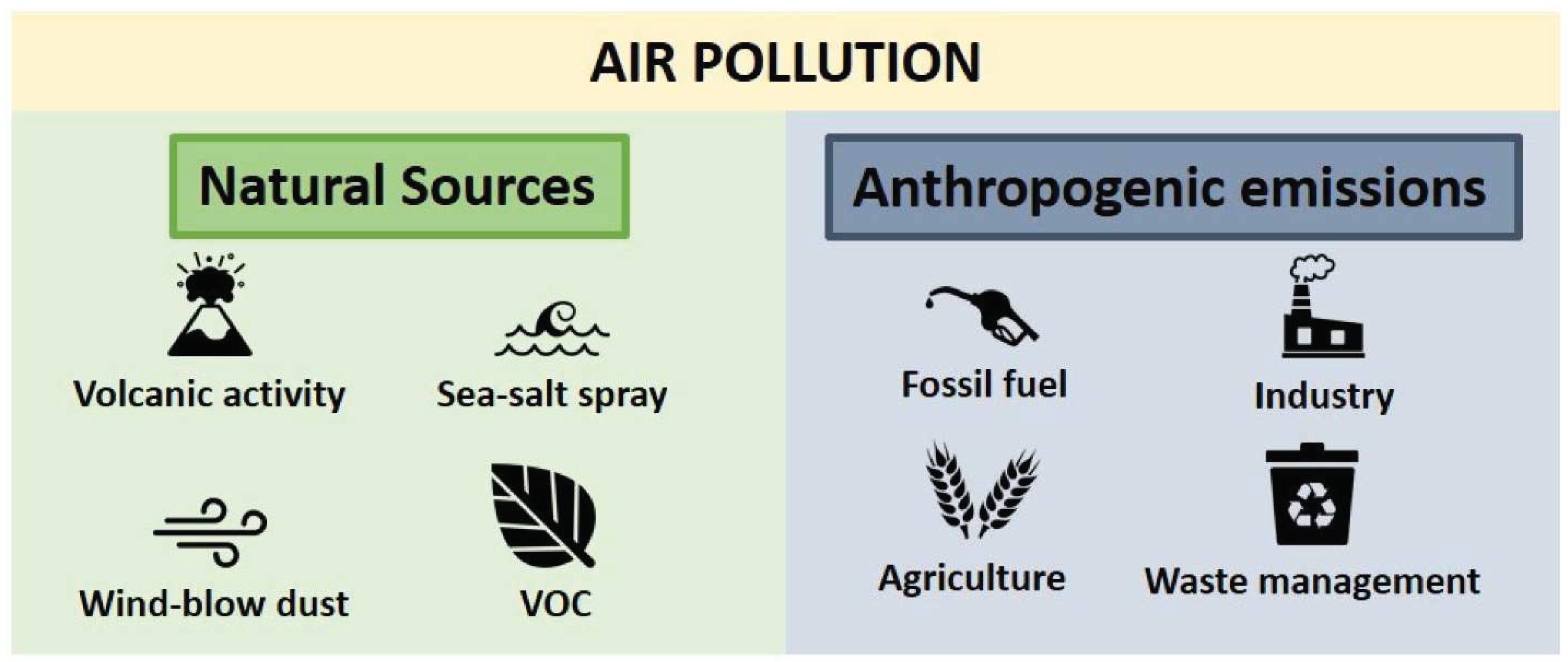

1. Introduction to Toxic Gases

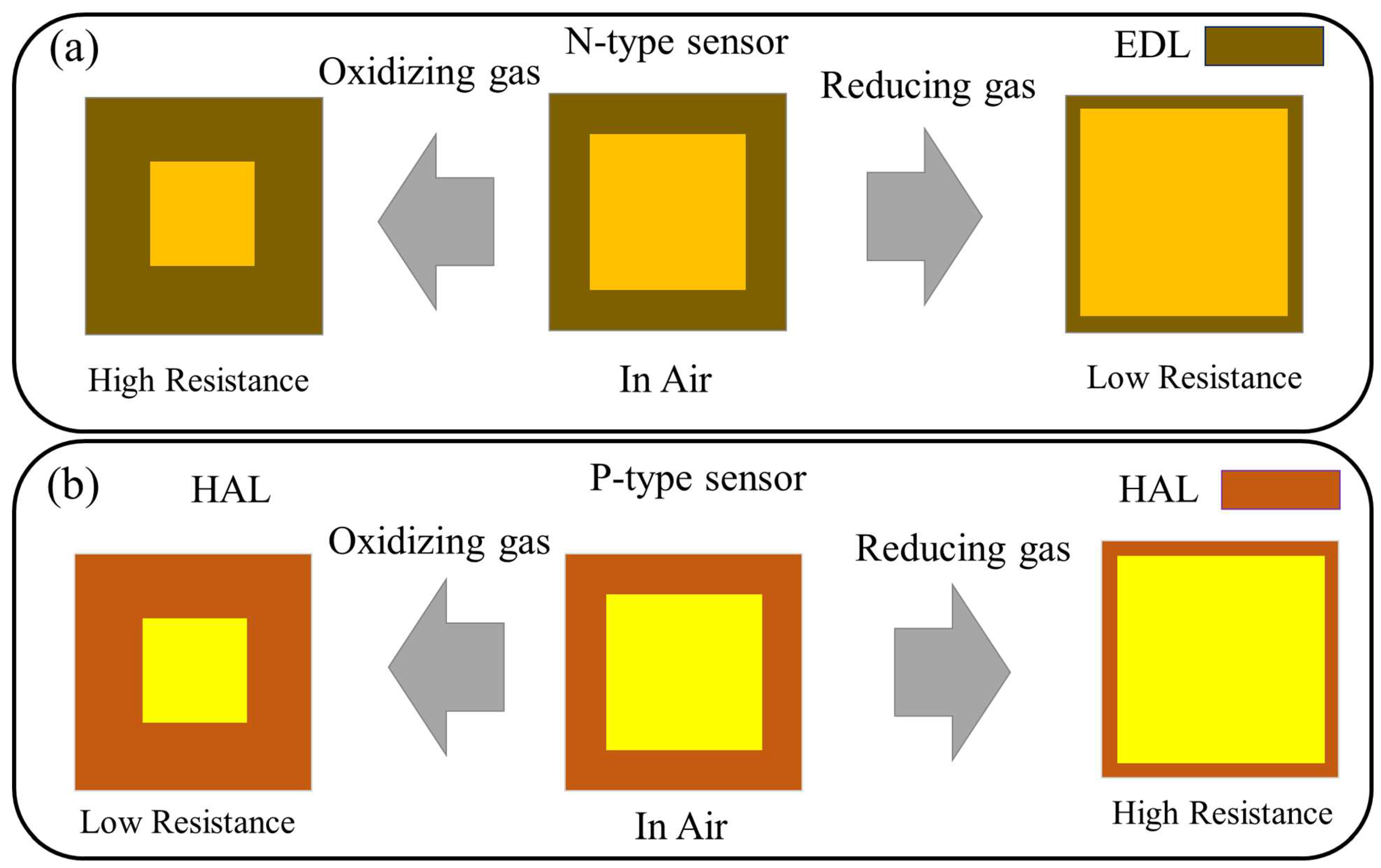

2. Resistive Gas Sensors: An Introduction

3. The Plasma Concept

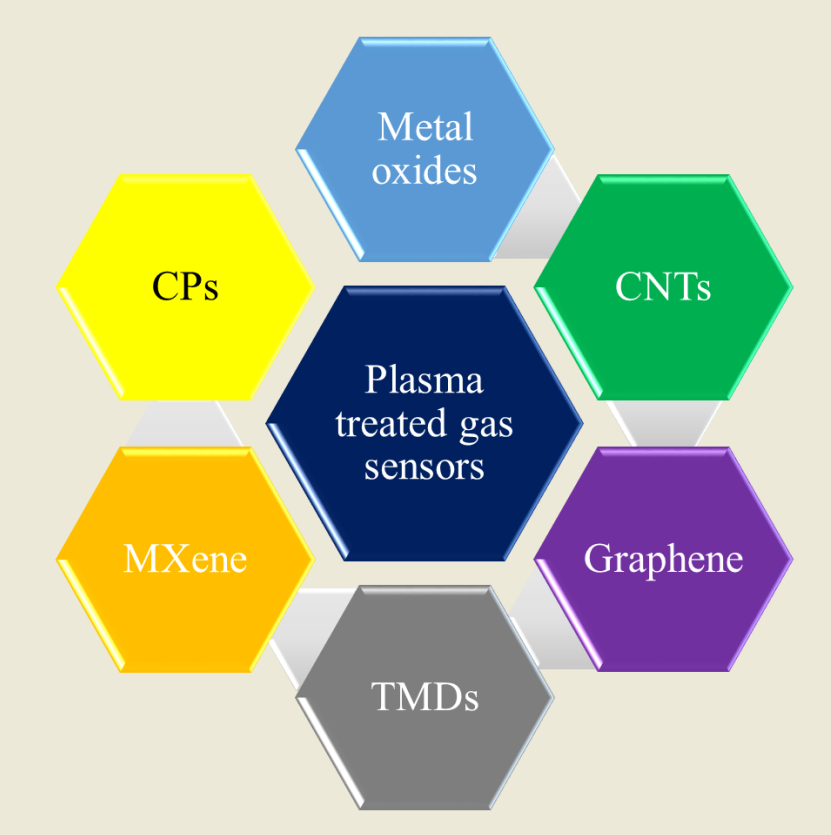

4. Plasma-Treated Gas Sensors

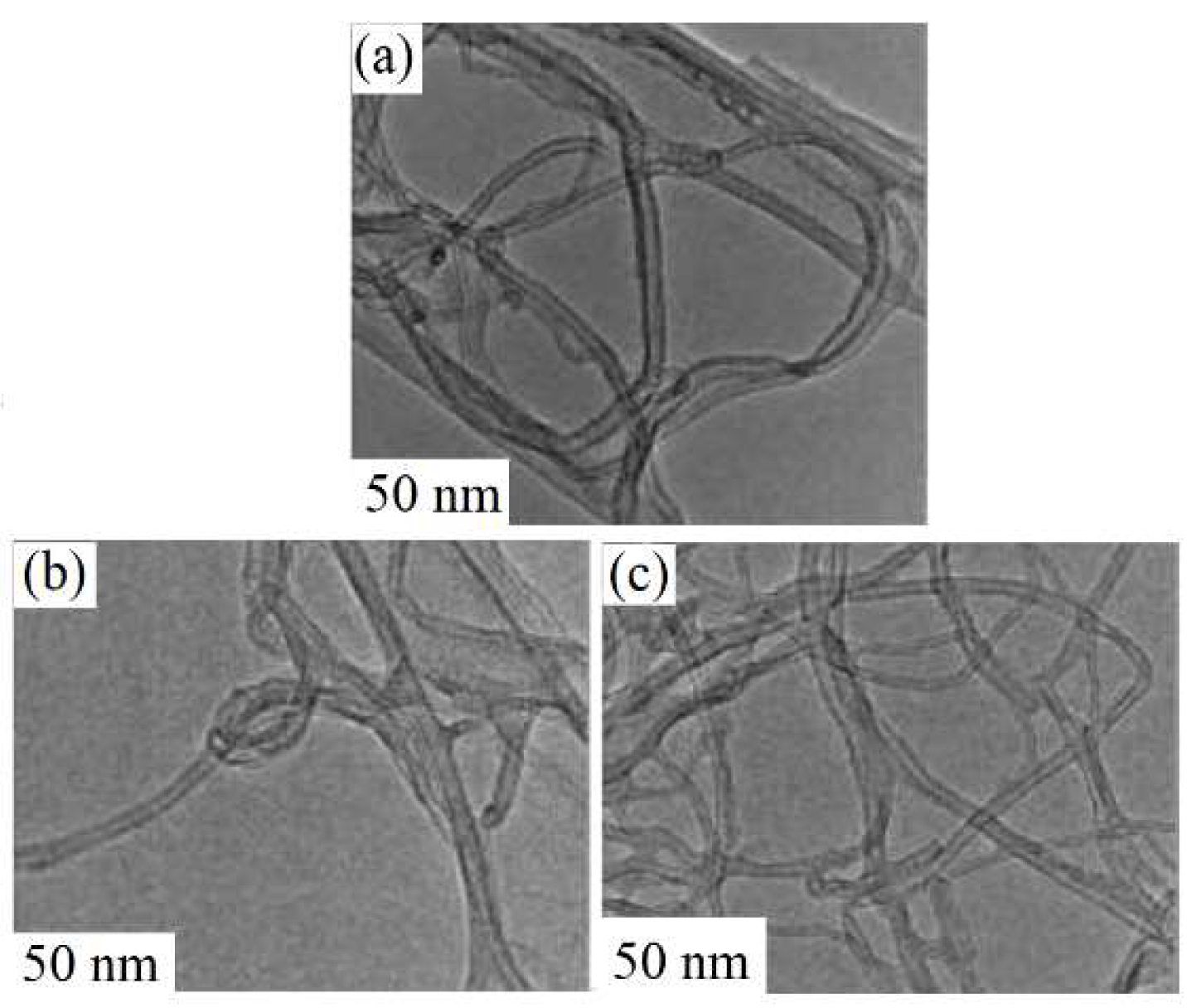

4.1. Plasma-Treated Carbon Nanotube Gas Sensors

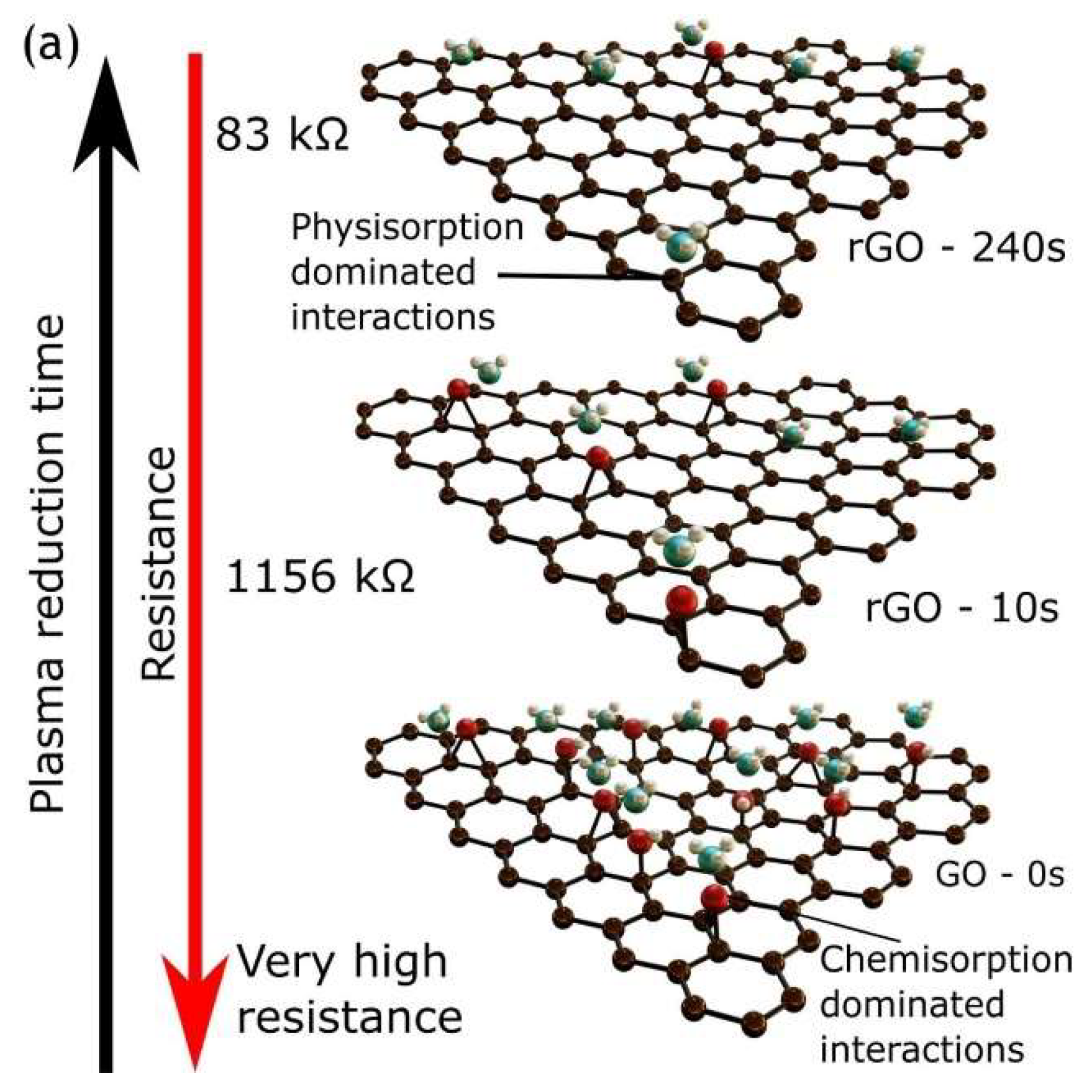

4.2. Plasma-Treated Graphene and Graphene Oxide Gas Sensors

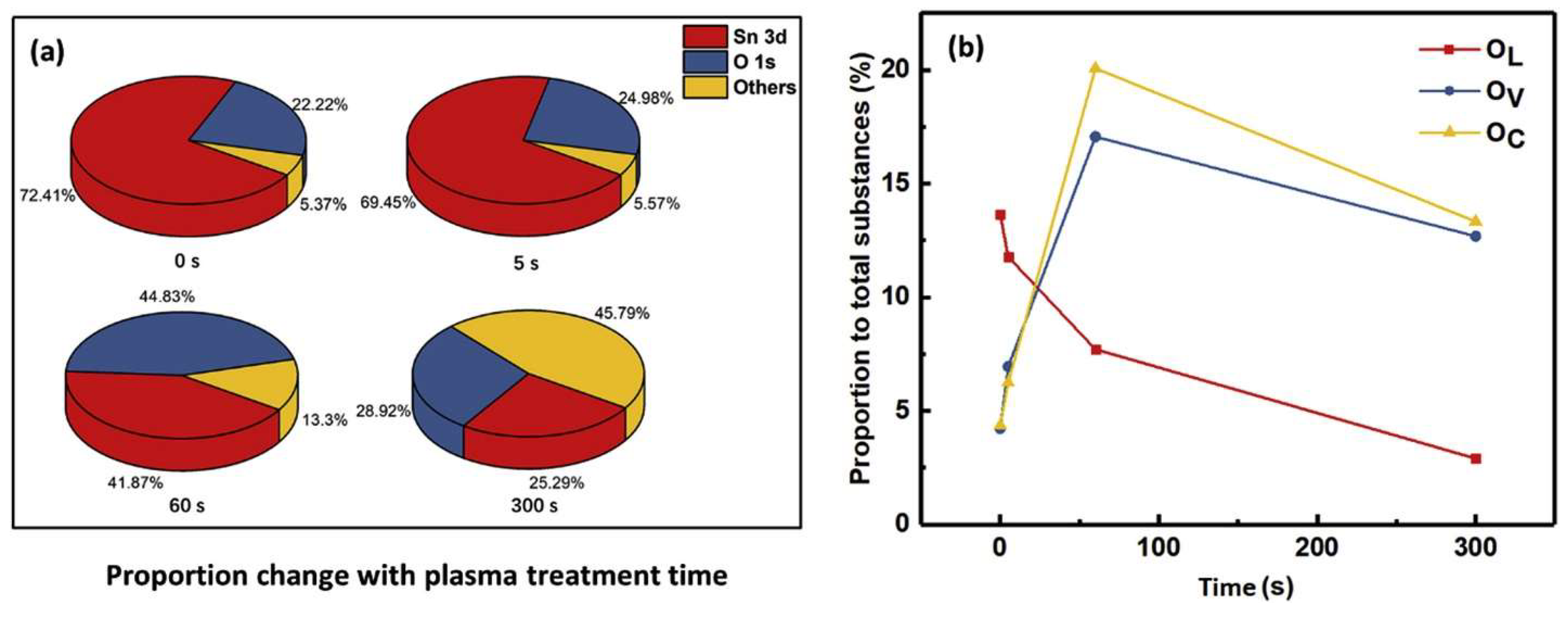

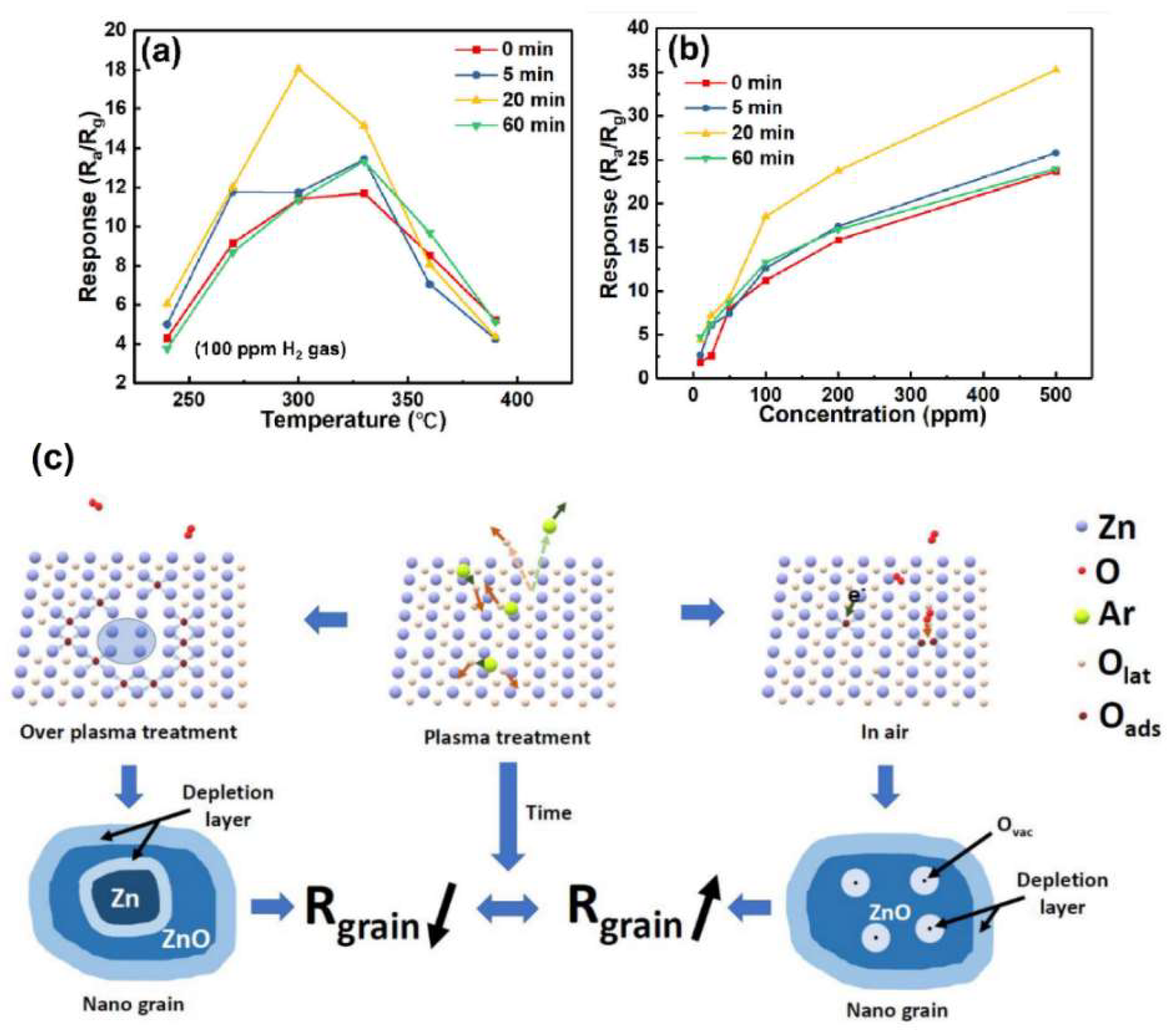

4.3. Plasma-Treated ZnO Gas Sensors

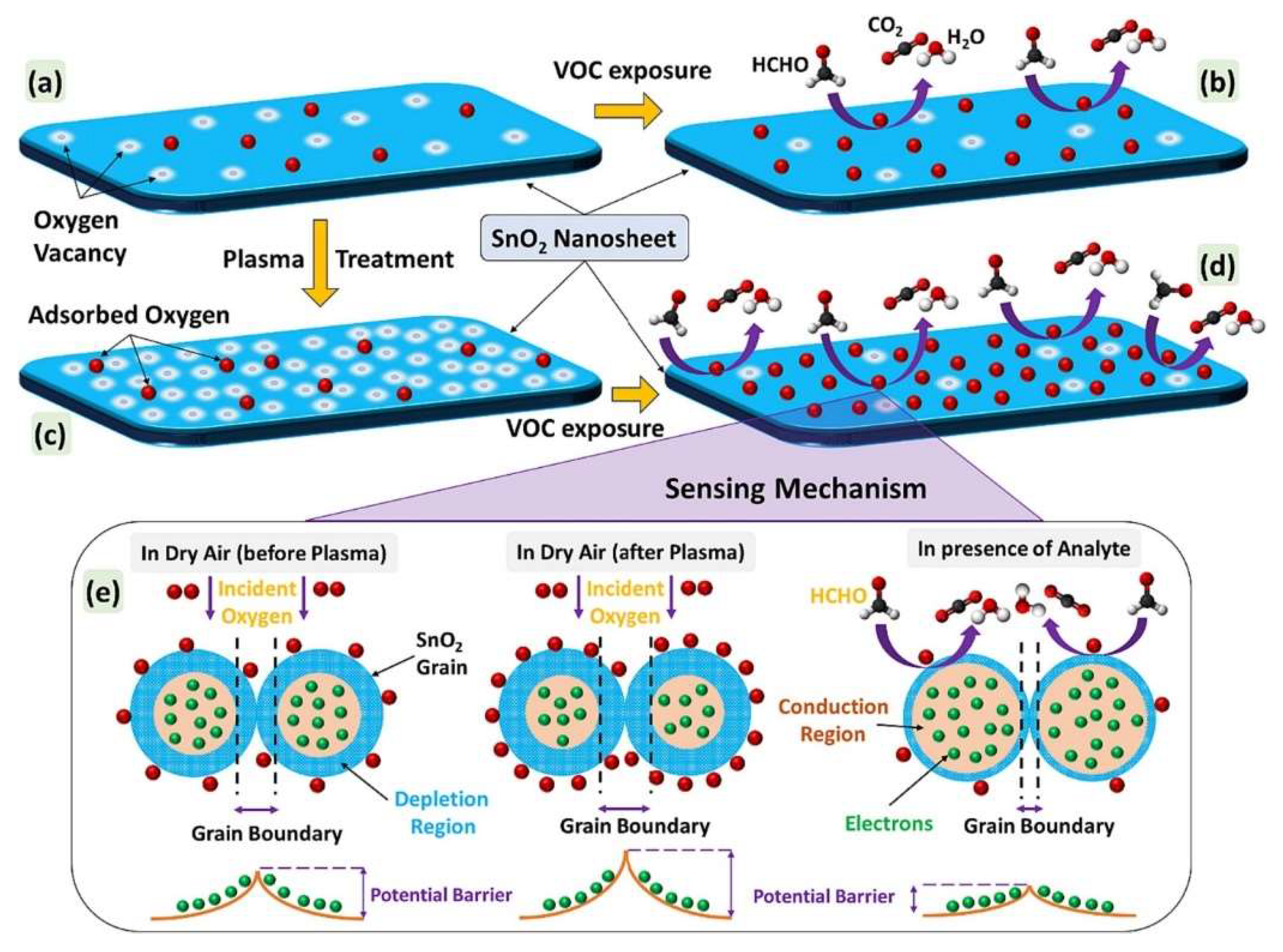

4.4. Plasma-Treated SnO2 Gas Sensors

4.5. Plasma Treated In2O3 Gas Sensors

4.6. Other Plasma Treated Gas Sensors

5. Conclusion and Outlooks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global Burden of 369 Diseases and Injuries in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quilliec, E.; Fundere, A.; Al-U’datt, D.G.F.; Hiram, R. Pollutants, Including Organophosphorus and Organochloride Pesticides, May Increase the Risk of Cardiac Remodeling and Atrial Fibrillation: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gal, O.; Eitan, O.; Rachum, A.; Weinberg, M.; Zigdon, D.; Assa, R.; Price, C.; Yovel, Y. Air Pollution Likely Reduces Hemoglobin Levels in Urban Fruit Bats. iScience 2025, 28, 111997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E.; Stavropoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and Health Impacts of Air Pollution: A Review. Frontiers in Public Health 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Zhong, R.; Xu, M.; He, P.; Mo, H.; Qin, Y.; Shi, D.; Chen, X.; He, K.; Zhang, Q. Interactions Among Food Systems, Climate Change, and Air Pollution: A Review. Engineering 2025, 44, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.N.B.; Honour, S.L.; Power, S.A. Effects of Vehicle Exhaust Emissions on Urban Wild Plant Species. Environmental Pollution 2011, 159, 1984–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Jiang, B.; Tong, M.; Zuo, H.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Song, S.; Lu, L.; Li, X. Effects and Interaction of Humidex and Air Pollution on Influenza: A National Analysis of 319 Cities in Mainland China. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 490, 137865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semczuk-Kaczmarek, K.; Rys-Czaporowska, A.; Sierdzinski, J.; Kaczmarek, L.D.; Szymanski, F.M.; Platek, A.E. Association between Air Pollution and COVID-19 Mortality and Morbidity. Internal and Emergency Medicine 2022, 17, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aithal, S.S.; Sachdeva, I.; Kurmi, O.P. Air Quality and Respiratory Health in Children. Breathe 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meerbeke, S.W.; McCarty, M.; Petrov, A.A.; Schonffeldt-Guerrero, P. The Impact of Climate, Aeroallergens, Pollution, and Altitude on Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction. Immunology and Allergy Clinics 2025, 45, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiotiu, A.I.; Novakova, P.; Nedeva, D.; Chong-Neto, H.J.; Novakova, S.; Steiropoulos, P.; Kowal, K. Impact of Air Pollution on Asthma Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.-C.; Tsai, S.-W.; Shie, R.-H.; Zeng, C.; Yang, H.-Y. Indoor Air Pollution Increases the Risk of Lung Cancer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syama, K.P.; Blais, E.; Kumarathasan, P. Maternal Mechanisms in Air Pollution Exposure-Related Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 970, 178999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayart, N.-E.; Pereira, G.; Reid, C.M.; Nyadanu, S.D.; Badamdorj, O.; Lkhagvasuren, B.; Rumchev, K. Effects of Outdoor Air Pollution on Hospital Admissions from Cardiovascular Diseases in the Capital City of Mongolia. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2024, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, A.; Harmon, A.C.; Dugas, T.R. Particulate Matter Air Pollutants and Cardiovascular Disease: Strategies for Intervention. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2021, 223, 107890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glencross, D.A.; Ho, T.-R.; Camiña, N.; Hawrylowicz, C.M.; Pfeffer, P.E. Air Pollution and Its Effects on the Immune System. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2020, 151, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; Agathokleous, E.; Anenberg, S.C.; Marco, A.D.; Paoletti, E.; Calatayud, V. Trends in Urban Air Pollution over the Last Two Decades: A Global Perspective. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858, 160064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, J.; Song, S.; Chen, J.; Zhong, N.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wan, B.; He, Y.; Karimi-Maleh, H. Recent Advances in Optical Gas Sensors for Carbon Dioxide Detection. Measurement 2025, 239, 115445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundamentals and Principles of Solid-State Electrochemical Sensors for High Temperature Gas Detection. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4344/12/1/1 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Kumar, A.; Prajesh, R. The Potential of Acoustic Wave Devices for Gas Sensing Applications. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2022, 339, 113498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Muraikhi, M.D.; Ayesh, A.I.; Mirzaei, A. Resistive Gas Sensors Based on Inorganic Nanotubes: A Review. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2025, 1020, 179585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Neri, G. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Metal Oxide Nanostructures for Gas Sensing Application: A Review. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2016, 237, 749–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.-Y.; Hou, P.-X.; Zhang, F.; Liu, C.; Cheng, H.-M. Gas Sensors Based on Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, A.; Bharath, S.P.; Kim, J.-Y.; Pawar, K.K.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. N-Doped Graphene and Its Derivatives as Resistive Gas Sensors: An Overview. Chemosensors 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiranakumar, H. V.; Thejas, R.; Naveen, C.S.; Khan, M.I.; Prasanna G, D; Reddy, S.; Oreijah, M.; Guedri, K.; Bafakeeh, O.T.; Jameel, M. A Review on Electrical and Gas-Sensing Properties of Reduced Graphene Oxide-Metal Oxide Nanocomposites. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024, 14, 12625–12635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matindoust, S.; Farzi, G.; Nejad, M.B.; Shahrokhabadi, M.H. Polymer-Based Gas Sensors to Detect Meat Spoilage: A Review. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2021, 165, 104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Fan, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X. Noble-Transition-Metal Dichalcogenides-Emerging Two-Dimensional Materials for Sensor Applications. Applied Physics Reviews 2023, 10, 031306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, V.; Roshan, H.; Mirzaei, A.; Neri, G.; Ayesh, A.I. Nanostructured Metal Oxide-Based Acetone Gas Sensors: A Review. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonyani, M.; Zebarjad, S.M.; Mirzaei, A.; Kim, T.-U.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Electrospun ZnO Hollow Nanofibers Gas Sensors: An Overview. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2024, 1001, 175201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Muraikhi, M.D.; Ayesh, A.I.; Mirzaei, A. Review of Nanostructured Bi2O3, Bi2WO6, and BiVO4 as Resistive Gas Sensors. Surfaces and Interfaces 2025, 60, 106003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Muraikhi, M.D.; Mirzaei, A.; Ayesh, A.I. Nanostructured Nb2O5 as Chemiresistive Gas Sensors. Ceramics International 2024, 50, 54897–54911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappa, D.; Galstyan, V.; Kaur, N.; Arachchige, H.M.M.M.; Sisman, O.; Comini, E. “Metal Oxide -Based Heterostructures for Gas Sensors”- A Review. Analytica Chimica Acta 2018, 1039, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degler, D.; Weimar, U.; Barsan, N. Current Understanding of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Doped and Loaded Semiconducting Metal-Oxide-Based Gas Sensing Materials. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 2228–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.-Y.; Ou, L.-X.; Mao, L.-W.; Wu, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.-P.; Lu, H.-L. Advances in Noble Metal-Decorated Metal Oxide Nanomaterials for Chemiresistive Gas Sensors: Overview. Nano-Micro Letters 2023, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, A.; Ansari, H.R.; Shahbaz, M.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Metal Oxide Semiconductor Nanostructure Gas Sensors with Different Morphologies. Chemosensors 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhi, S.M.; Mirzaei, A.; Navale, S.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Boosting the Sensing Properties of Resistive-Based Gas Sensors by Irradiation Techniques: A Review. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 4728–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H.; Lee, M. A.; Han, G. J.; Cho, B. H. Plasma in Dentistry: A Review of Basic Concepts and Applications in Dentistry. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 2013, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, M.; Lund, M.N.; Tiwari, B.K.; Poojary, M.M. Chemical and Physical Changes Induced by Cold Plasma Treatment of Foods: A Critical Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2024, 23, e13376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, J. de A.; Lamarão, C.V.; Sanches, E.A.; Rodrigues, S.; Fernandes, F.A.N.; Ramos, G.L.P.A.; Esmerino, E.A.; Cruz, A.G.; Campelo, P.H. Cold Plasma as a Pre-Treatment for Processing Improvement in Food: A Review. Food Research International 2023, 167, 112663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbekar, A.A.; Deshmukh, R.R. Plasma Surface Modification of Flexible Substrates to Improve Grafting for Various Gas Sensing Applications: A Review. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2022, 50, 1382–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán, C.; Fabregat, G.; Armelin, E.; Buendía, J.J.; Llorca, J. Plasma Surface Modification of Polymers for Sensor Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 6515–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, C. Overview on the Surface Functionalization Mechanism and Determination of Surface Functional Groups of Plasma Treated Carbon Nanotubes. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2017, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leghrib, R.; Felten, A.; Demoisson, F.; Reniers, F.; Pireaux, J.-J.; Llobet, E. Room-Temperature, Selective Detection of Benzene at Trace Levels Using Plasma-Treated Metal-Decorated Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon 2010, 48, 3477–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambardekar, V.; Sahoo, S.; Srivastava, D.K.; Majumder, S.B.; Bandyopadhyay, P.P. Plasma Sprayed CuO Coatings for Gas Sensing and Catalytic Conversion Applications. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2021, 331, 129404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambardekar, V.; Bandyopadhyay, P.P.; Majumder, S.B. Plasma Sprayed Copper Oxide Sensor for Selective Sensing of Carbon Monoxide. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2021, 258, 123966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.S.; Bang, J.H.; Mirzaei, A.; Na, H.G.; Kwon, Y.J.; Kang, S.Y.; Choi, S.-W.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, H.W. Dual Sensitization of MWCNTs by Co-Decoration with p- and n-Type Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2018, 264, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.J.; Mirzaei, A.; Kang, S.Y.; Choi, M.S.; Bang, J.H.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, H.W. Synthesis, Characterization and Gas Sensing Properties of ZnO-Decorated MWCNTs. Applied Surface Science 2017, 413, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagna, L.; Nisticò, R.; Musso, S.; Pavese, M. Functionalization as a Way to Enhance Dispersion of Carbon Nanotubes in Matrices: A Review. Materials Today Chemistry 2021, 20, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Guo, X.; Lin, L.; Cai, Q.; Cheng, J.; Li, J. Gas-Sensing Characteristics of Dielectrophoretically Assembled Composite Film of Oxygen Plasma-Treated SWCNTs and PEDOT/PSS Polymer. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2013, 178, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leghrib, R.; Pavelko, R.; Felten, A.; Vasiliev, A.; Cané, C.; Gràcia, I.; Pireaux, J.-J.; Llobet, E. Gas Sensors Based on Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes Decorated with Tin Oxide Nanoclusters. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2010, 145, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Kim, J.; Park, C.; Jin, J.-H.; Min, N.K. Long-Term Stability of Superhydrophilic Oxygen Plasma-Modified Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Network Surfaces and the Influence on Ammonia Gas Detection. Applied Surface Science 2017, 410, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.; Choi, C.; Woong Jang, C.; Lee, S.; Min Jhon, Y. Sensitivity Enhancement of Carbon Nanotube Based Ammonium Ion Sensors through Surface Modification by Using Oxygen Plasma Treatment. Applied Physics Letters 2013, 102, 073108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Yang, B.; Xiao, H. Enhancement of Gas Sensing Characteristics of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes by CF4 Plasma Treatment for SF6 Decomposition Component Detection. Journal of Nanomaterials 2015, 2015, 171545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, P.; Ramos, A.; Lazaro, A.; Molina-Luna, L.; Bittencourt, C.; Girbau, D.; Llobet, E. Oxygen Plasma Treated Carbon Nanotubes for the Wireless Monitoring of Nitrogen Dioxide Levels. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2015, 208, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, B.; Wang, X.; Luo, C. Effect of Plasma Treatment on Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for the Detection of H2S and SO2. Sensors 2012, 12, 9375–9385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannov, A.G.; Jašek, O.; Manakhov, A.; Márik, M.; Nečas, D.; Zajíčková, L. High-Performance Ammonia Gas Sensors Based on Plasma Treated Carbon Nanostructures. IEEE Sensors Journal 2017, 17, 1964–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannov, A.G.; Manakhov, A.M.; Shtansky, D.V. Plasma Functionalization of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Ammonia Gas Sensors. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.-Y.; Ham, D.-J.; Kang, B.H.; Lee, K.; Choi, J.; Lee, J.-W.; Choi, H.H.; Ju, B.-K. Effect of Plasma Treatment on the Gas Sensor with Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Paste. Talanta 2012, 89, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhosh, N.M.; Vasudevan, A.; Jurov, A.; Korent, A.; Slobodian, P.; Zavašnik, J.; Cvelbar, U. Improving Sensing Properties of Entangled Carbon Nanotube-Based Gas Sensors by Atmospheric Plasma Surface Treatment. Microelectronic Engineering 2020, 232, 111403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.W.; Hong, H.P.; Kim, J.H.; Min, S.J.; Min, N.K. Effect of Oxygen Plasma Treatment on Carbon Nanotube-Based Sensors. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2014, 14, 8476–8481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamansky, K.K.; Osipova, A.A.; Fedorov, F.S.; Kopylova, D.S.; Shunaev, V.; Alekseeva, A.; Glukhova, O.E.; Nasibulin, A.G. Sensitivity Enhancement of SWCNT Gas Sensors by Nitrogen Plasma Treatment. Applied Surface Science 2023, 640, 158334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.W.; Hong, H.P.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, K.B.; Park, C.W.; Min, N.K. Comparison of Gas Sensors Based on Oxygen Plasma-Treated Carbon Nanotube Network Films with Different Semiconducting Contents. Journal of Electronic Materials 2015, 44, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farea, M.A.; Mohammed, H.Y.; Shirsat, S.M.; Sayyad, P.W.; Ingle, N.N.; Al-Gahouari, T.; Mahadik, M.M.; Bodkhe, G.A.; Shirsat, M.D. Hazardous Gases Sensors Based on Conducting Polymer Composites: Review. Chemical Physics Letters 2021, 776, 138703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, W.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, M.; Zhang, J. Conducting Polymer-Based Nanostructures for Gas Sensors. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2022, 462, 214517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Jian, J.; Lin, L.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, S. O2 Plasma-Functionalized SWCNTs and PEDOT/PSS Composite Film Assembled by Dielectrophoresis for Ultrasensitive Trimethylamine Gas Sensor. Analyst 2013, 138, 5265–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.-P.; Kwon, K.-H.; Min, N.-K.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, C.J. Effects of O2 Plasma Treatment on NH3 Sensing Characteristics of Multiwall Carbon Nanotube/Polyaniline Composite Films. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2009, 143, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Song, M.-J.; Kim, K.B.; Jin, J.-H.; Min, N.K. Evaluation of Surface Cleaning Procedures in Terms of Gas Sensing Properties of Spray-Deposited CNT Film: Thermal- and O2 Plasma Treatments. Sensors 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Fam, D.W.H.; Yin, Z.; Sun, T.; Tan, H.T.; Liu, W.; Tok, A.I.Y.; Boey, Y.C.F.; Zhang, H.; Hng, H.H.; et al. A Carbon Monoxide Gas Sensor Using Oxygen Plasma Modified Carbon Nanotubes. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 425502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedin, F.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Hill, E.W.; Blake, P.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Novoselov, K.S. Detection of Individual Gas Molecules Adsorbed on Graphene. Nature Materials 2007, 6, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Bu, X.; Deng, M.; Chen, G.; Zhang, G.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, W. A Gas Sensing Channel Composited with Pristine and Oxygen Plasma-Treated Graphene. Sensors 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capote Mastrapa, G.; Freire Jr., F. L. Plasma-Treated CVD Graphene Gas Sensor Performance in Environmental Condition: The Role of Defects on Sensitivity. Journal of Sensors 2019, 2019, 5492583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fan, L.; Dong, H.; Zhang, P.; Nie, K.; Zhong, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Sun, X. Spectroscopic Investigation of Plasma-Fluorinated Monolayer Graphene and Application for Gas Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 8652–8661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.G.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, H.M.; Kim, T.; Choi, J.H.; Seo, D. kyun; Yoo, J.-B.; Hong, S.-H.; Kang, T.J.; Kim, Y.H. Highly Sensitive NO2 Gas Sensor Based on Ozone Treated Graphene. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2012, 166–167, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, K.; Liu, K.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Z. Metal Oxide Resistive Sensors for Carbon Dioxide Detection. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2022, 472, 214758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Chafer, J.; Garcia-Aboal, R.; Llobet, E.; Atienzar, P. Enhanced CO2 Sensing by Oxygen Plasma-Treated Perovskite–Graphene Nanocomposites. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, I.; Duch, M.C.; Mansukhani, N.D.; Hersam, M.C.; Bouchard, D. Colloidal Properties and Stability of Graphene Oxide Nanomaterials in the Aquatic Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 6288–6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimiev, A.M.; Tour, J.M. Mechanism of Graphene Oxide Formation. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 3060–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangamani, G.J.; Deshmukh, K.; Kovářík, T.; Nambiraj, N.A.; Ponnamma, D.; Sadasivuni, K.K.; Khalil, H.P.S.A.; Pasha, S.K.K. Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites Based Room Temperature Gas Sensors: A Review. Chemosphere 2021, 280, 130641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafiz, S.M.; Ritikos, R.; Whitcher, T.J.; Razib, N.M.; Bien, D.C.S.; Chanlek, N.; Nakajima, H.; Saisopa, T.; Songsiriritthigul, P.; Huang, N.M.; et al. A Practical Carbon Dioxide Gas Sensor Using Room-Temperature Hydrogen Plasma Reduced Graphene Oxide. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2014, 193, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaj, A.K.; Donà, E.; Santhosh, N.M.; Shvalya, V.; Košiček, M.; Cvelbar, U. Plasma-Modification of Graphene Oxide for Advanced Ammonia Sensing. Applied Surface Science 2024, 660, 160006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, D.; Kraus, F.; Müller, J. A Novel Gas Sensor Design Based on CH4/H2/H2O Plasma Etched ZnO Thin Films. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2003, 92, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.B.K.; Thong, J.T.L. Improving the NH3 Gas Sensitivity of ZnO Nanowire Sensors by Reducing the Carrier Concentration. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 205502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, T.; Guo, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. Highly Response Gas Sensor Based the Au-ZnO Films Processed by Combining Magnetron Sputtering and Ar Plasma Treatment. Physica Scripta 2023, 98, 075609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Jayatissa, A.H. Enhancement of Gas Sensor Response of Nanocrystalline Zinc Oxide for Ammonia by Plasma Treatment. Applied Surface Science 2014, 309, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Zhao, S.; Tian, K.; Wu, J.; Guo, H.; Qin, X.; Qin, X.; Guo, D.; Zheng, G.; Guo, Y. Oxygen Plasma Treatment to Enhance the Gas-Sensing Performance of ZnO to N-Methyl Pyrrolidone: Experimental and Computational Study. Ceramics International 2024, 50, 47418–47427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.M. Atomic Layer Deposition: An Overview. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, L.; Yang, C.; Pinna, N.; Zhang, J. Platinum Single Atoms on Tin Oxide Ultrathin Films for Extremely Sensitive Gas Detection. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, S.; Cao, S.; Lei, G.; Lou, C.; Zhang, J. Plasma-Induced Oxygen Vacancies Enabled Ultrathin ZnO Films for Highly Sensitive Detection of Triethylamine. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 415, 125757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Jayaraman, V. SnO2: A Comprehensive Review on Structures and Gas Sensors. Progress in Materials Science 2014, 66, 112–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, Y. Recent Advances in SnO2 Nanostructure Based Gas Sensors. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 364, 131876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiyoto, K.A.M.; Fisher, E.R. Utilizing Plasma Modified SnO2 Paper Gas Sensors to Better Understand Gas-Surface Interactions at Low Temperatures. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A 2020, 38, 043202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckert, E.P.; Miller, C.J.; Fisher, E.R. The Effect of Ar/O2 and H2O Plasma Treatment of SnO2 Nanoparticles and Nanowires on Carbon Monoxide and Benzene Detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 15733–15743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, R.; Dwivedi, R.; Srivastava, S.K. Effect of Oxygen and Hydrogen Plasma Treatment on the Room Temperature Sensitivity of SnO2 Gas Sensors. Microelectronics Journal 1998, 29, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, A.; Mishra, V.N.; Dwivedi, R.; Srivastava, S.K. Response of Oxygen Plasma-Treated Thick Film Tin Oxide Sensor Array for LPG, CCl4, CO and C3H7OH. Microelectronics Journal 1999, 30, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyya, S.; Guha, P.K. Enhanced Formaldehyde Sensing Performance Employing Plasma-Treated Hierarchical SnO2 Nanosheets through Oxygen Vacancy Modulation. Applied Surface Science 2024, 655, 159640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Yousefi, H.R.; Falsafi, F.; Bonyani, M.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. An Overview on How Pd on Resistive-Based Nanomaterial Gas Sensors Can Enhance Response toward Hydrogen Gas. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 20552–20571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Yao, H.; Shi, X.; Xu, S. Chemoresistive Gas Sensors Based on Noble-Metal-Decorated Metal Oxide Semiconductors for H2 Detection. Materials 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Zeng, W. Enhanced Hydrogen Gas Sensing Properties of Pd-Doped SnO2 Nanofibres by Ar Plasma Treatment. Ceramics International 2020, 46, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, A.; Mishra, V.N.; Dwivedi, R.; Srivastava, S.K. Selectivity and Sensitivity Studies on Plasma Treated Thick Film Tin Oxide Gas Sensors. Microelectronics Journal 2000, 31, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Ganesan, R.; Shen, H.; Mathur, S. Plasma-Modified SnO2 Nanowires for Enhanced Gas Sensing. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 8245–8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Tan, O.K.; Lee, Y.C.; Tran, T.D.; Tse, M.S.; Yao, X. Semiconductor Gas Sensor Based on Tin Oxide Nanorods Prepared by Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition with Postplasma Treatment. Applied Physics Letters 2005, 87, 163123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lee, Y.C.; Chow, C.L.; Tan, O.K.; Tse, M.S.; Guo, J.; White, T. Plasma Treatment of SnO2 Nanocolumn Arrays Deposited by Liquid Injection Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition for Gas Sensors. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2009, 138, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Wang, F.; Shen, Z.; Liu, H.; Zeng, W.; Wang, Y. Ar Plasma Treatment on ZnO–SnO2 Heterojunction Nanofibers and Its Enhancement Mechanism of Hydrogen Gas Sensing. Ceramics International 2020, 46, 21439–21447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Yao, P.; Li, X.; Yu, N. Investigation of Gas Sensing Properties of SnO2/In2O3 Composite Hetero-Nanofibers Treated by Oxygen Plasma. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2015, 206, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.-Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, P.; Yu, N.-S.; Sun, Y.-H.; Tian, J.-L. Investigation of Gas Sensing Materials Tin Oxide Nanofibers Treated by Oxygen Plasma. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2014, 16, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothilal, H.; Shukla, G.; Walia, S.; Kundu, S.; Angappane, S. Humidity Sensing and Breath Analyzing Applications of TiO2 Slanted Nanorod Arrays. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2020, 301, 111758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Qi, T.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Yang, X. Improving Anti-Humidity Property of In2O3 Based NO2 Sensor by Fluorocarbon Plasma Treatment. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2021, 344, 130268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wang, H.; Yao, P.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y. In2O3 Nanofibers Surface Modified by Low-Temperature RF Plasma and Their Gas Sensing Properties. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2018, 215, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

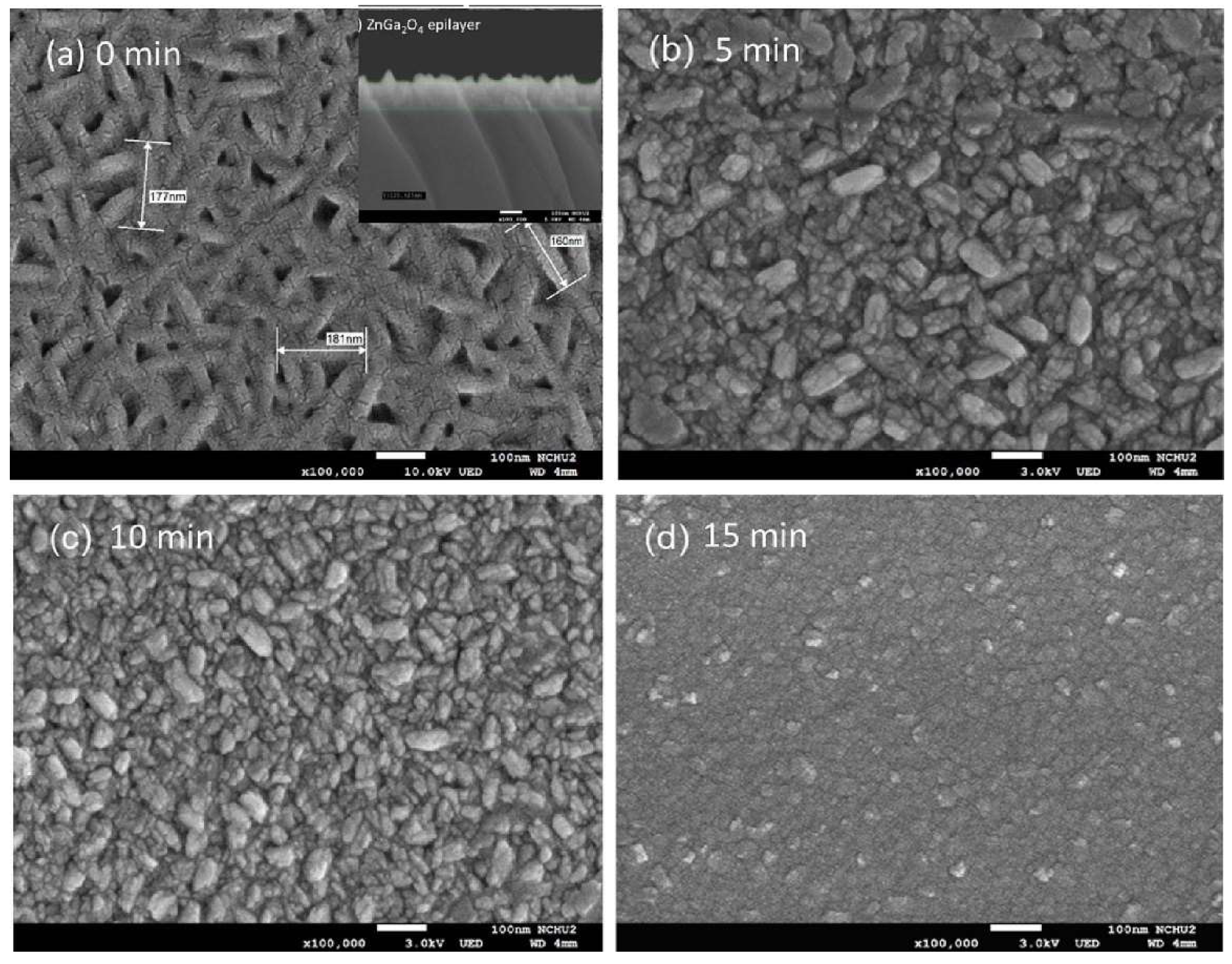

- Wu, M.-R.; Li, W.-Z.; Tung, C.-Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chiang, Y.-H.; Liu, P.-L.; Horng, R.-H. NO Gas Sensor Based on ZnGa2O4 Epilayer Grown by Metalorganic Chemical Vapor Deposition. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-Y.; Singh, A.K.; Shao, J.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Shieh, J.-M.; Wuu, D.-S.; Liu, P.-L.; Horng, R.-H. Performance Improvement of MOCVD Grown ZnGa2O4 Based NO Gas Sensors Using Plasma Surface Treatment. Applied Surface Science 2023, 637, 157929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Roy, S. Polypyrrole and Associated Hybrid Nanocomposites as Chemiresistive Gas Sensors: A Comprehensive Review. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2021, 121, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Tanner, P.; Thiel, D.V. O2 Plasma Treated Polyimide-Based Humidity Sensors. Analyst 2002, 127, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Du, H.; Chu, J. Improved NO2 Gas-Sensing Performance of PPy by Hydrogen Plasma Treatment: Experimental Study and DFT Verification. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2023, 364, 114848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzo, P.; Lobotka, P.; Micusik, M.; Kovacova, E. Palladium-Free Hydrogen Sensor Based on Oxygen-Plasma-Treated Polyaniline Thin Film. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2012, 171–172, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Nie, J.; Cao, Y.; Gao, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Lu, X.; Ma, X.; Zhong, P. A Review of How to Improve Ti3C2Tx MXene Stability. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 496, 154097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Resistive Gas Sensors Based on 2D TMDs and MXenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 2395–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, J.H.; Nam, M.-S.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Accordion-like Ti3C2Tx MXene with High Flexibility for NH3 Sensing in Self-Heating Mode. Ceramics International 2025, 51, 2930–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, J.; Xu, J.; Hu, H.; Ho, D. Atomic Plasma Grafting: Precise Control of Functional Groups on Ti3C2Tx MXene for Room Temperature Gas Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 12232–12239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, H.R.; Mirzaei, A.; Shokrollahi, H.; Kumar, R.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, H.W.; Kumar, M.; Kim, S.S. Flexible/Wearable Resistive Gas Sensors Based on 2D Materials. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 6528–6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Laishram, R.; Gupta, B.K.; Srivastva, R.; Sinha, O.P. A Review on MX2 (M = Mo, W and X = S, Se) Layered Material for Opto-Electronic Devices. Advances in Natural Sciences: Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2022, 13, 023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, W.S.; Kim, D.K.; Han, J.-H.; Park, K.-B.; Ryu, S.C.; Min, N.K.; Kim, J.H. Functionalization of Molybdenum Disulfide via Plasma Treatment and 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid for Gas Sensors. Nanomaterials 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).