Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

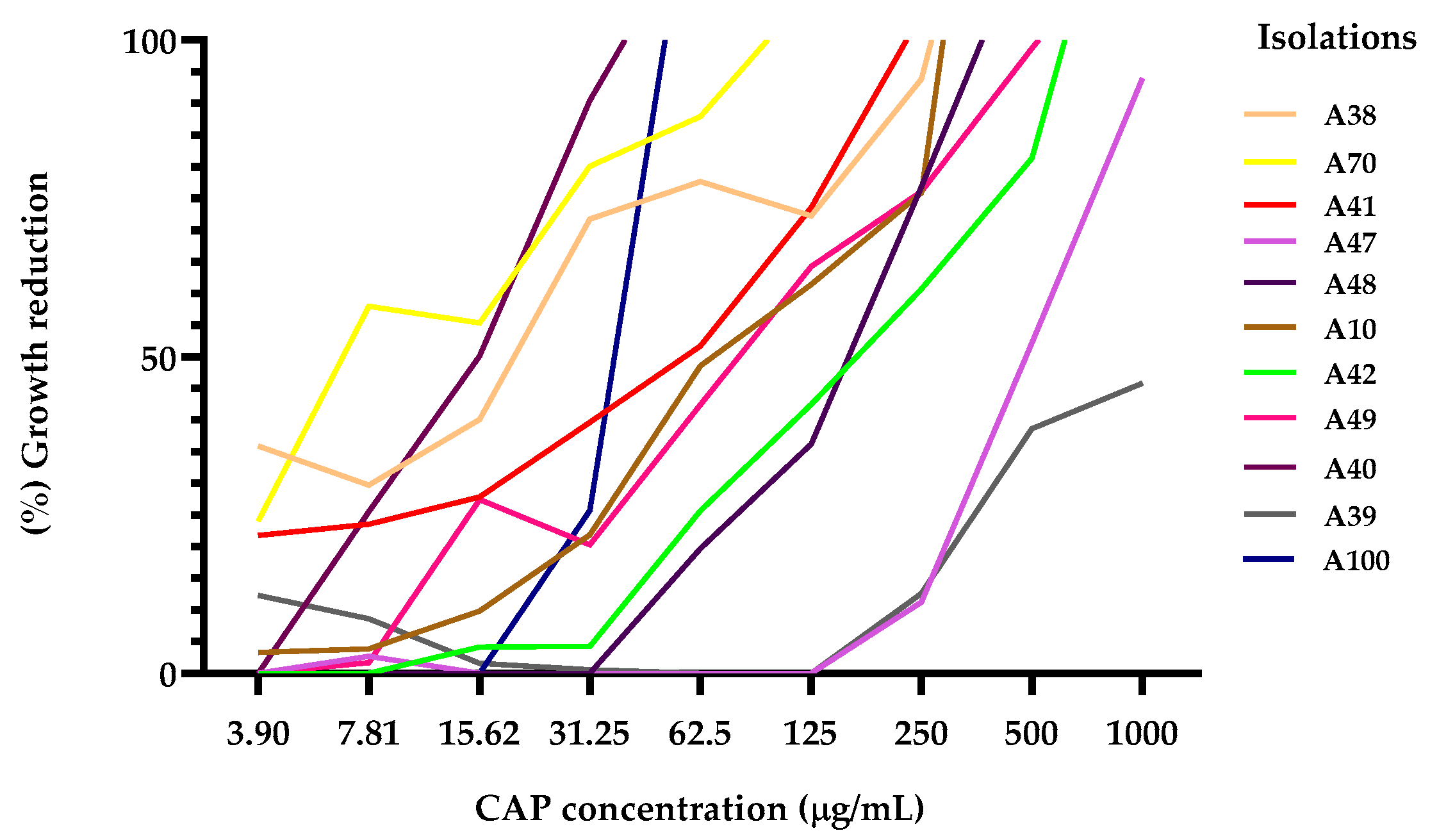

2.1. Susceptibility Testing

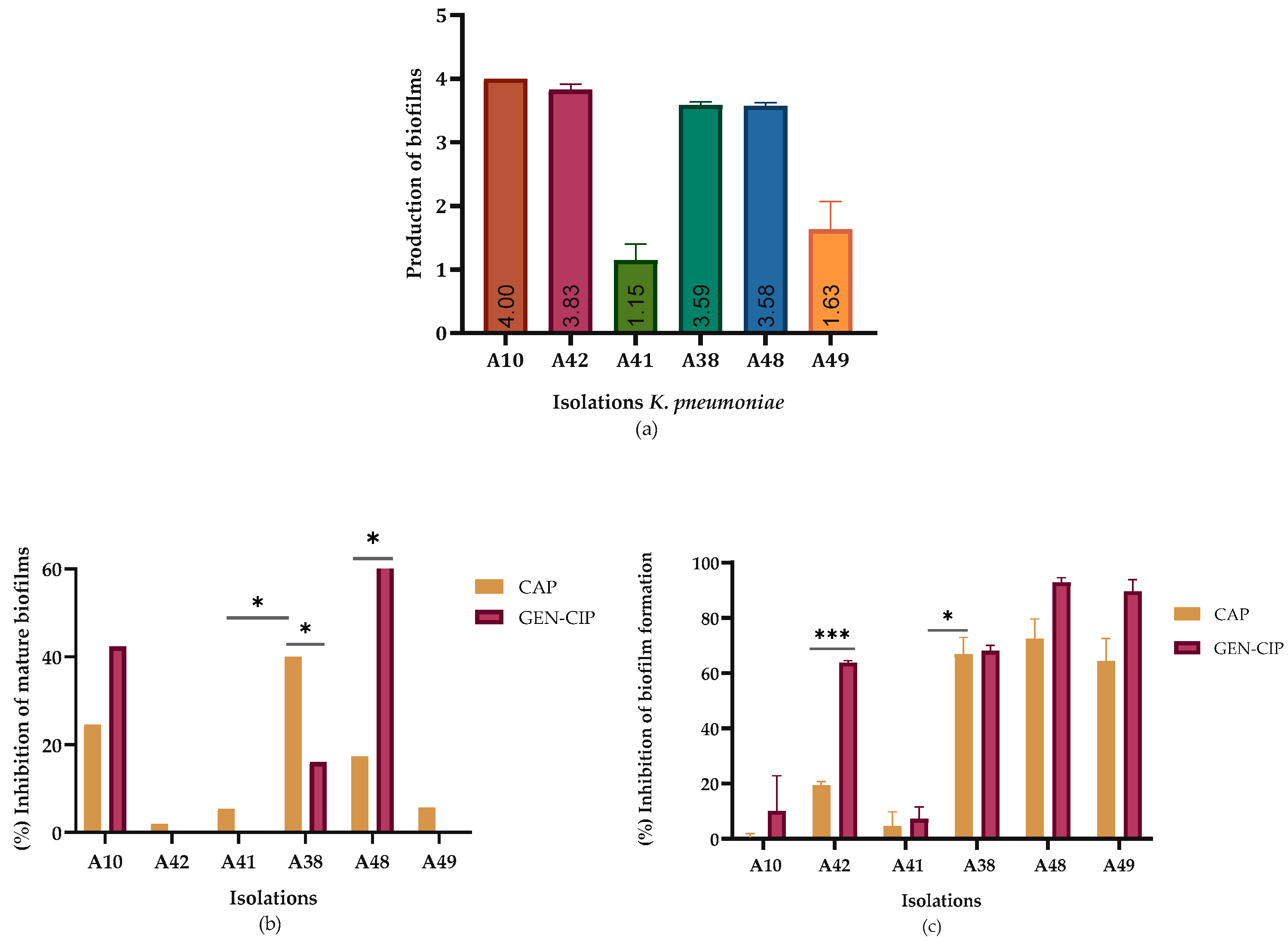

2.2. Biofilm Reduction

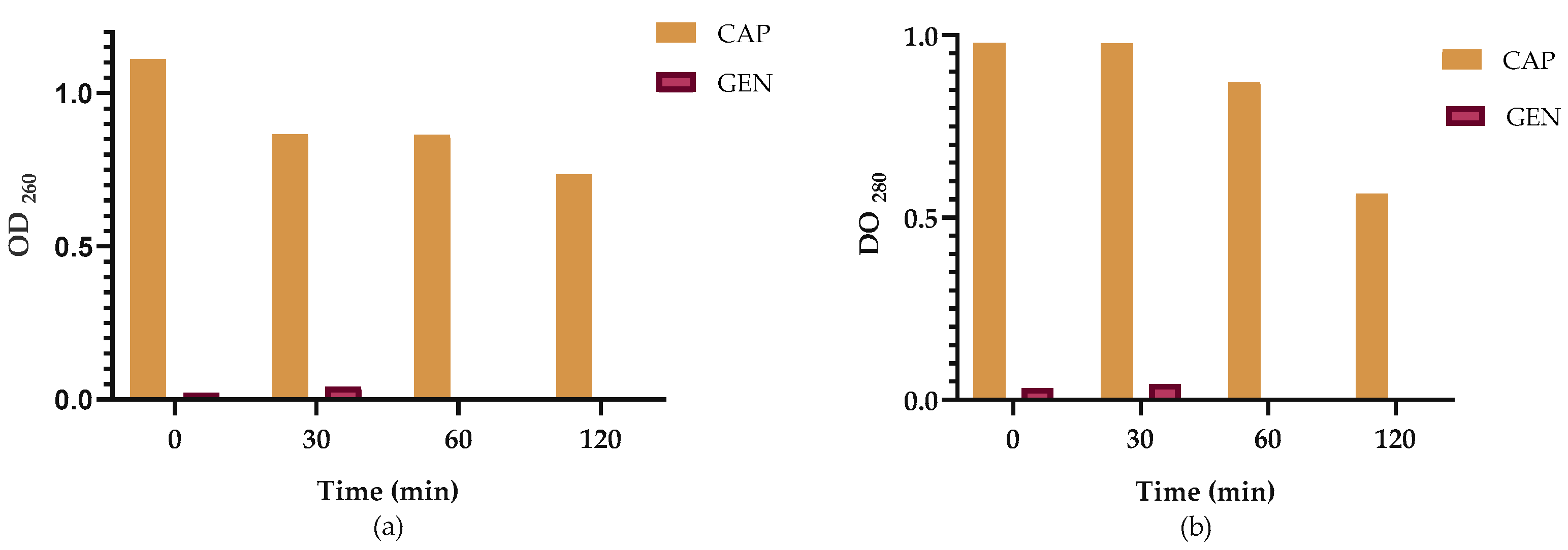

2.3. Leakage of Nucleic Acids and Proteins Through the Klebsiella pneumoniae Membrane

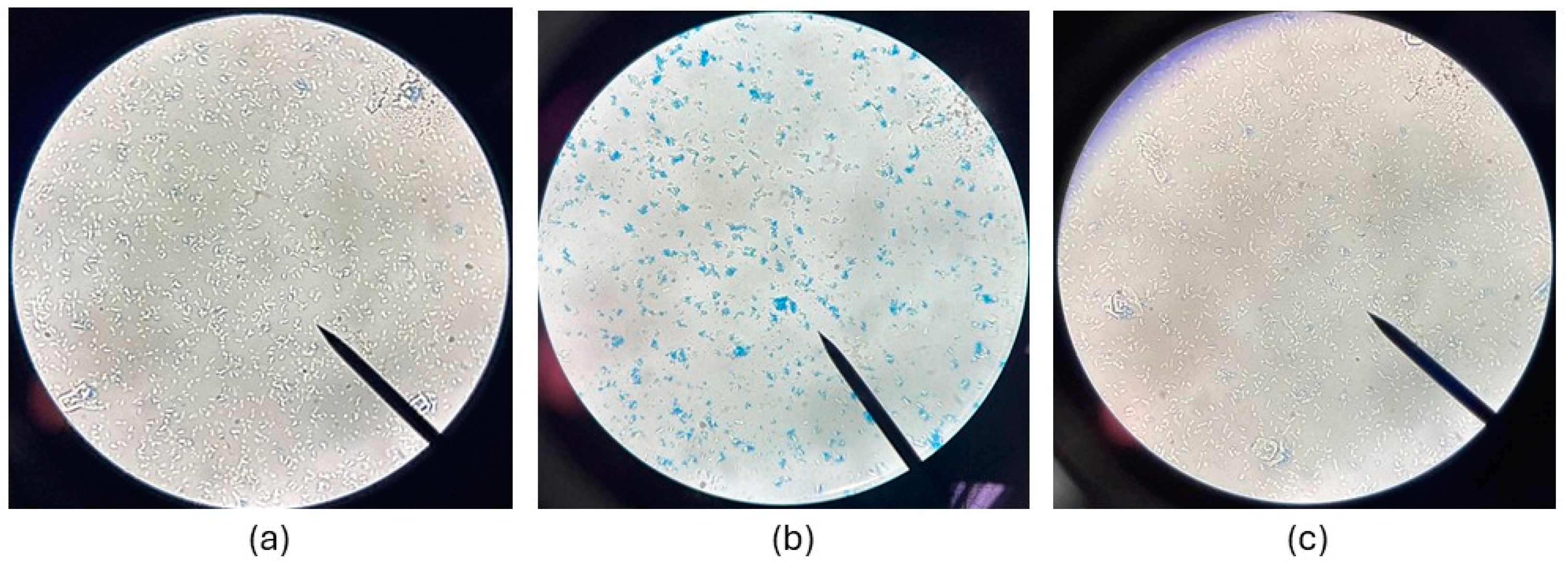

2.4. Effect of CAP on Membrane Integrity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

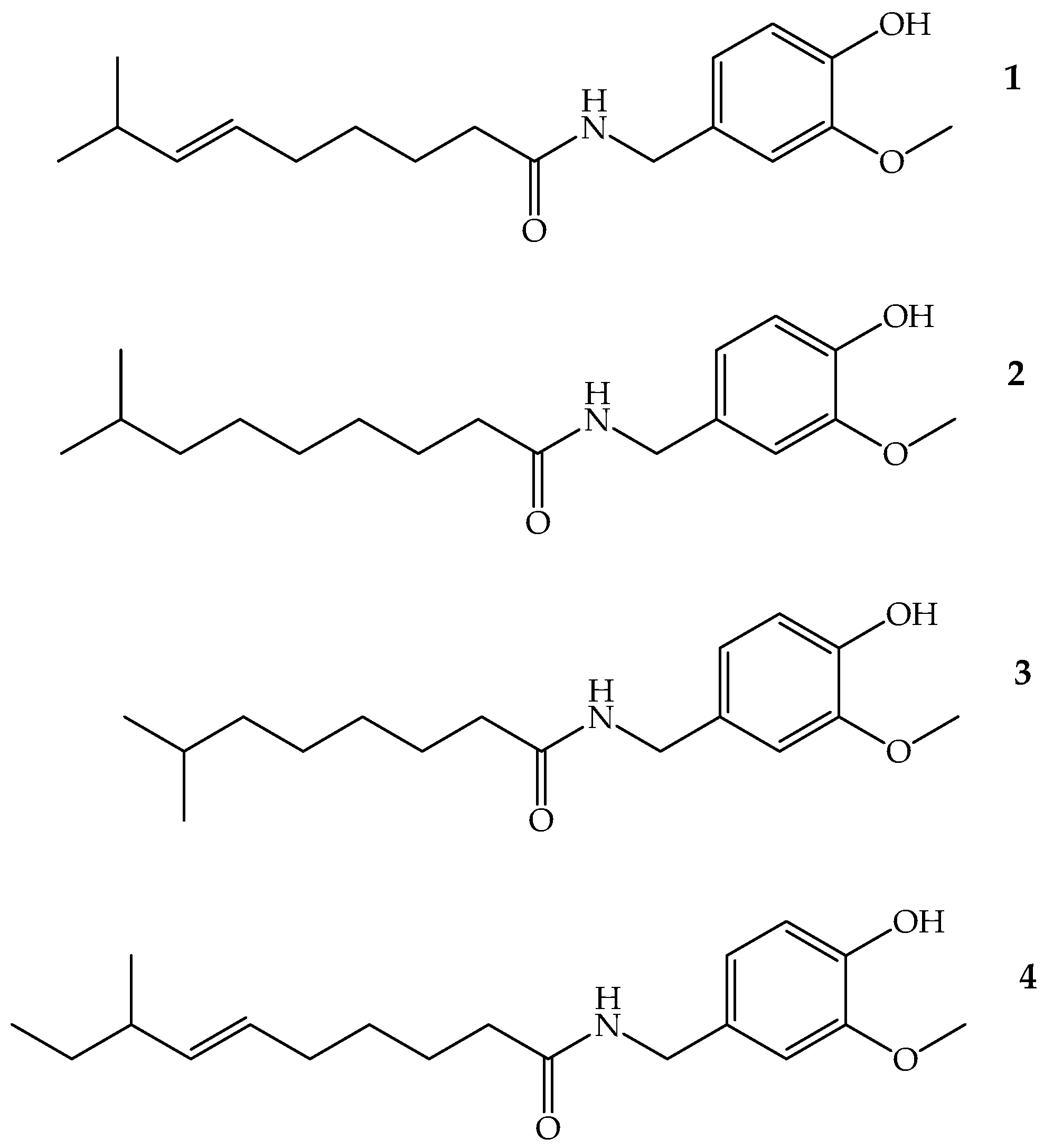

4.2. Capsaicin

4.3. Strains

4.3. Susceptibility Testing

4.4. Quantitative Evaluation of Biofilm Inhibition

4.5. Leakage of Nucleic Acids and Proteins Through the Cell Membrane

4.6. Effect of Extracts on Membrane Integrity

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| hvKP | Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| CAP | Capsaicin |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| TCS | Two Component Regulatory System |

| CRKP | Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| CHINET | China Antimicrobial Surveillance Network |

| ATBs | Antibiotics |

| CIP | Ciprofloxacin |

| GEN | Gentamicin |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| MHB | Mueller–Hinton Broth |

| TSA | Tryptic Soy Agar |

| TSB | Tryptic Soy Broth |

| MHA | Mueller– Hinton Agar |

| BHI | Brain Heart Infusion |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| CV | Crystal violet |

| CFU/mL | Colony forming units/ milliliter |

| OD | Optical density |

References

- García-Cobos, S.; Oteo-Iglesias, J.; Pérez-Vázquez, M. Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Epidemiology outside Asian countries, antibiotic resistance association, methods of detection and clinical management. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhao, G.; Chao, X.; Xie, L.; Wang, H. The characteristic of virulence, biofilm and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella Pneumoniae. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020, pp 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K. L.; Lam, M. M. C.; Holt, K. E. Population genomics of Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2020, pp 344–359. [CrossRef]

- Candan, E. D.; Aksöz, N. Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Characteristics of carbapenem resistance and virulence factors. Acta Biochim Pol 2015, 62 (4), 867–874. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Dong, N.; Chan, E. W. C.; Zhang, R.; Chen, S. Carbapenem resistance-encoding and virulence-encoding conjugative plasmids in Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Trends in Microbiology. 2021, pp 65–83. [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K. L.; Holt, K. E. Klebsiella Pneumoniae as a key trafficker of drug resistance genes from environmental to clinically important bacteria. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2018, pp 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Van Giang, T.; Anh, N. K.; Phuong, N. Q.; Dat, L. T.; Van Duyet, L. Clinical, antibiotic resistance features, and treatment outcomes of Vietnamese patients with community-acquired sepsis caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae. IJID Regions 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Russo, T. A.; Carlino-MacDonald, U.; Drayer, Z. J.; Davies, C. J.; Alvarado, C. L.; Hutson, A.; Luo, T. L.; Martin, M. J.; McGann, P. T.; Lebreton, F. Deciphering the relative importance of genetic elements in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae to guide countermeasure development. EBioMedicine 2024, 107. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, J.; Cheng, P.; Li, M.; Yu, Z.; Song, X.; Yu, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z. Roles of two-component regulatory systems in Klebsiella pneumoniae: regulation of virulence, antibiotic resistance, and stress responses. Microbiological Research. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Tang, J.; Qu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Kuang, L.; Su, M.; Mu, D. nosocomial infection by Klebsiella pneumoniae among neonates: a molecular epidemiological study. Journal of Hospital Infection 2021, 108, 174–180. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M. E. S.; Destro, G.; Vieira, B.; Lima, A. S.; Ferraz, L. F. C.; Hakansson, A. P.; Darrieux, M.; Converso, T. R. Klebsiella Pneumoniae biofilms and their role in disease pathogenesis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vuotto, C.; Longo, F.; Pascolini, C.; Donelli, G.; Balice, M. P.; Libori, M. F.; Tiracchia, V.; Salvia, A.; Varaldo, P. E. Biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae urinary strains. J Appl Microbiol 2017, 123 (4), 1003–1018. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gao, X.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, W.; Sun, H.; Song, X.; Wang, Z. Relationship between biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae and updates on antibiofilm therapeutic strategies. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cholley, A. C.; Traoré, O.; Hennequin, C.; Aumeran, C. Klebsiella Pneumoniae survival and regrowth in endoscope channel biofilm exposed to glutaraldehyde and desiccation. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2020, 39 (6), 1129–1136. [CrossRef]

- Araldi, R. P.; dos Santos, M. O.; Barbon, F. F.; Manjerona, B. A.; Meirelles, B. R.; de Oliva Neto, P.; da Silva, P. I.; dos Santos, L.; Camargo, I. C. C.; de Souza, E. B. Analysis of antioxidant, cytotoxic and mutagenic potential of Agave sisalana Perrine extracts using Vero cells, human lymphocytes and mice polychromatic erythrocytes. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2018, 98, 873–885. [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen Bayisa, Y.; Aga Bullo, T. Optimization and characterization of oil extracted from Croton macrostachyus seed for antimicrobial activity using experimental analysis of variance. Heliyon 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Aylate, A.; Agize, M.; Ekero, D.; Kiros, A.; Ayledo, G.; Gendiche, K. In-vitro and in-vivo antibacterial activities of Croton macrostachyus methanol extract against E. coli and S. aureus. Adv Anim Vet Sci 2017, 5, 107–114. [CrossRef]

- Naman, C. B.; Benatrehina, P. A.; Kinghorn, A. D. Pharmaceuticals, Plant Drugs. 2016; Vol. 2. [CrossRef]

- Avato, P. Editorial to the Special Issue – “Natural products and drug discovery". Molecules 2020, 25, 1128. [CrossRef]

- Chapa-Oliver, A. M.; Mejía-Teniente, L. Capsaicin: from plants to a cancer-suppressing agent. Molecules. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Marini, E.; Magi, G.; Mingoia, M.; Pugnaloni, A.; Facinelli, B. Antimicrobial and anti-virulence activity of capsaicin against erythromycin-resistant, cell-invasive group A Streptococci. Front Microbiol 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Morrine, A. O.; Zen-Zi, W.; Weih, G. B.; Grant, A. H.; Kamal, D.; David, J. B. Comparative analysis of capsaicin in twenty-nine varieties of unexplored capsicum and its antimicrobial activity against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 2018, 12 (29), 544–556. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Asakura, M.; Chowdhury, N.; Neogi, S. B.; Sugimoto, N.; Haldar, S.; Awasthi, S. P.; Hinenoya, A.; Aoki, S.; Yamasaki, S. Capsaicin, a potential inhibitor of cholera toxin production in Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2010, 306 (1), 54–60. [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Li, M.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Jiao, H.; Li, G. Synergistic activity of capsaicin and colistin against colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: in vitro/vivo efficacy and mode of action. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jones, N. L.; Shabib, S.; Sherman, P. M. Capsaicin as an inhibitor of the growth of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1997, 146 (2), 223–227. [CrossRef]

- Periferakis, A. T.; Periferakis, A.; Periferakis, K.; Caruntu, A.; Badarau, I. A.; Savulescu-Fiedler, I.; Scheau, C.; Caruntu, C. Antimicrobial properties of capsaicin: available data and future research perspectives. Nutrients. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Duelund, L.; Mouritsen, O. Contents of capsaicinoids in chillies grown in Denmark. Food Chemistry 2017, 221, 913–918. [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. M.; Bachman, M. A. Colonization, infection, and the accessory genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ballén, V.; Gabasa, Y.; Ratia, C.; Ortega, R.; Tejero, M.; Soto, S. Antibiotic resistance and virulence profiles of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from different clinical sources. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Aminul, P.; Anwar, S.; Molla, M. M. A.; Miah, M. R. A. Evaluation of antibiotic resistance patterns in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Bangladesh. Biosaf Health 2021, 3 (6), 301–306. [CrossRef]

- Beig, M.; Aghamohammad, S.; Majidzadeh, N.; Asforooshani, M. K.; Rezaie, N.; Abed, S.; Khiavi, E. H. G.; Sholeh, M. Antibiotic resistance rates in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae strains: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2024, pp 376–388. [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.; Jannat, K.; Nissapatorn, V.; Rahmatullah, M.; Paul, A. K.; de Lourdes Pereira, M.; Rajagopal, M.; Suleiman, M.; Butler, M. S.; Break, M. K. Bin; Weber, J. F.; Wilairatana, P.; Wiart, C. Antibacterial and antifungal alkaloids from asian angiosperms: distribution, mechanisms of action, structure-activity, and clinical potentials. Antibiotics. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cushnie, T. P. T.; Cushnie, B.; Lamb, A. J. Alkaloids: an overview of their antibacterial, antibiotic-enhancing and antivirulence activities. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2014, 44 (5), 377–386. [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Sun, Z.; Wang, T.; Yang, M.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Antimicrobial activity of eugenol against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and its effect on biofilms. Microb Pathog 2020, 139. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S. H.; Mohamed, M. S. M.; Khalil, M. S.; Azmy, M.; Mabrouk, M. I. Combination of essential oil and ciprofloxacin to inhibit/eradicate biofilms in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Appl Microbiol 2018, 125 (1), 84–95. [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard—Ninth Edition; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2012; Volume 32.

- Contreras-Martínez, O.I.; Sierra-Quiroz, D.; Angulo-Ortíz, A. Antibacterial and antibiofilm potential of ethanolic extracts of Duguetia vallicola (Annonaceae) against in-hospital isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Plants 2024, 13, 1412. [CrossRef]

| Isolation of K. pneumoniae | CAP MIC90 | CIP MIC90 | GEN MIC90 |

| A70 | 121.8 | 4.44 | |

| A10* | 276.5 | 0.16 | |

| A48 | 504.1 | 4.55 | |

| A42 | 578.5 | 6.70 | |

| A41 | 191.5 | 1.19 | |

| A38 | 247.8 | 1.49 | |

| A47 | 920.1 | 0.12 | |

| A39 | 1696 | 4.55 | |

| A49 | 385 | 7.19 | |

| A100 | 56.37 | 2.63 | |

| A40 | 28.44 | 2.14 |

| K. pneumoniae isolates | CAP | CIP | GEN |

| A10* | 0.0 | 2.09 | |

| A42 | 19.49 | 63.77 | |

| A41 | 4.26 | 7.40 | |

| A38 | 67.77 | 68.27 | |

| A48 | 72.48 | 92.76 | |

| A49 | 65.26 | 89.96 |

| K. pneumoniae isolates | CAP | CIP | GEN |

| A10* | 24.57 | 42.31 | |

| A42 | 1.97 | 0.0 | |

| A41 | 8.45 | 0.00 | |

| A38 | 40.04 | 16.00 | |

| A48 | 16.90 | 63.47 | |

| A49 | 5.69 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).