Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Development of Typical Rotating Motion Mechanisms

2.1. Gear Mechanism

2.1.1. Spur Gear Mechanism

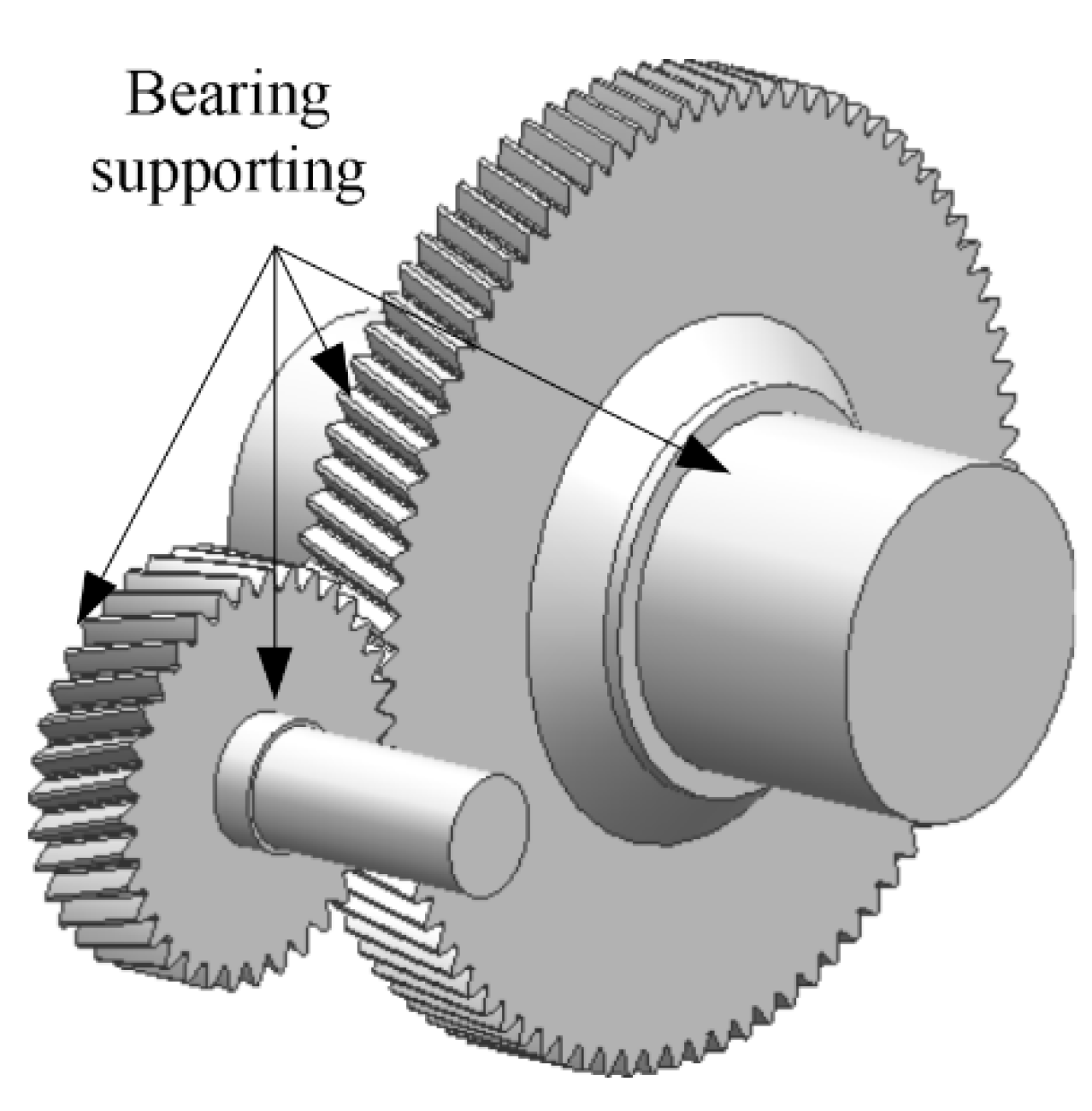

2.1.2. Helical Gear Mechanism

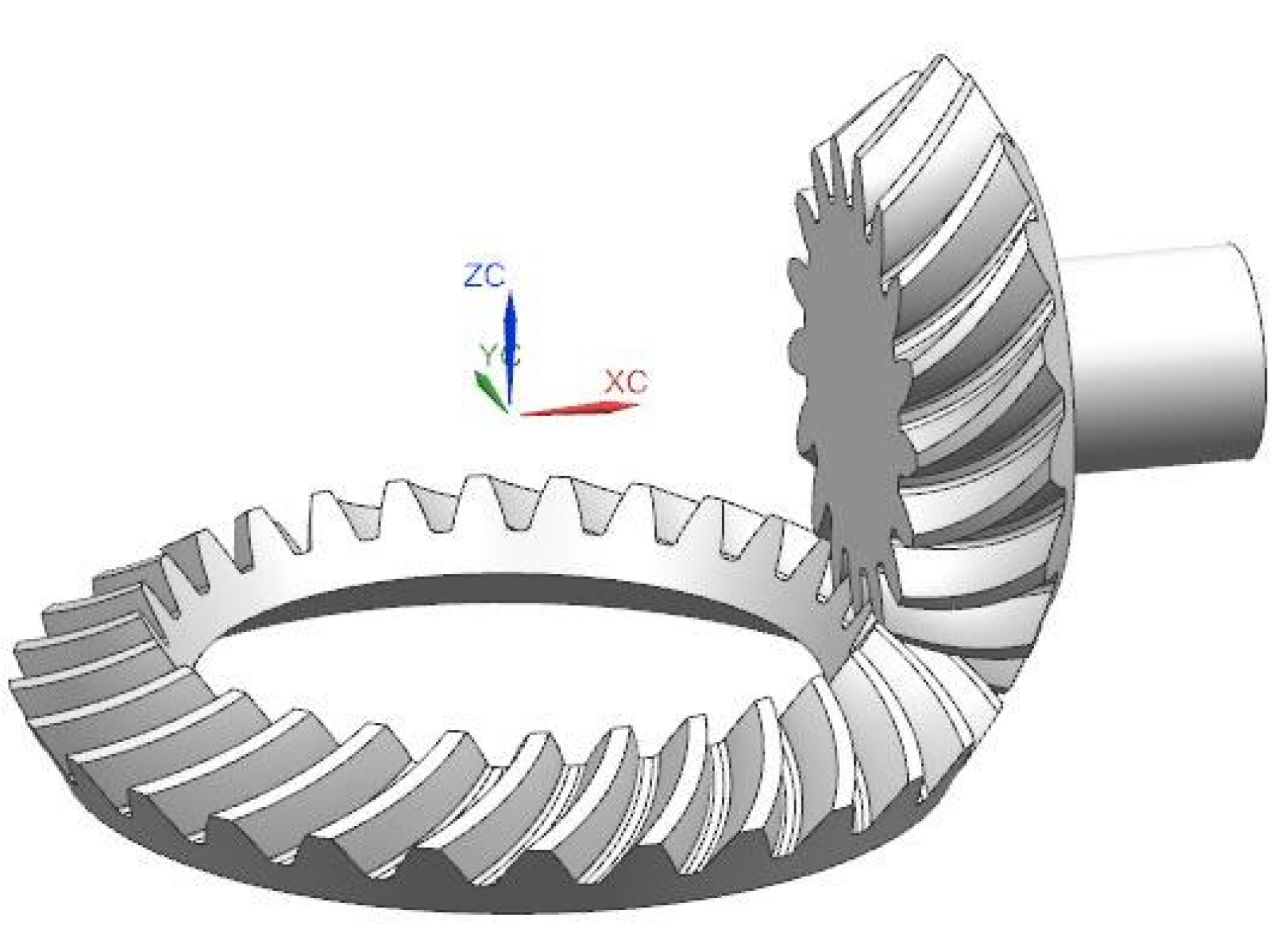

2.1.3. Conical Gear Mechanism

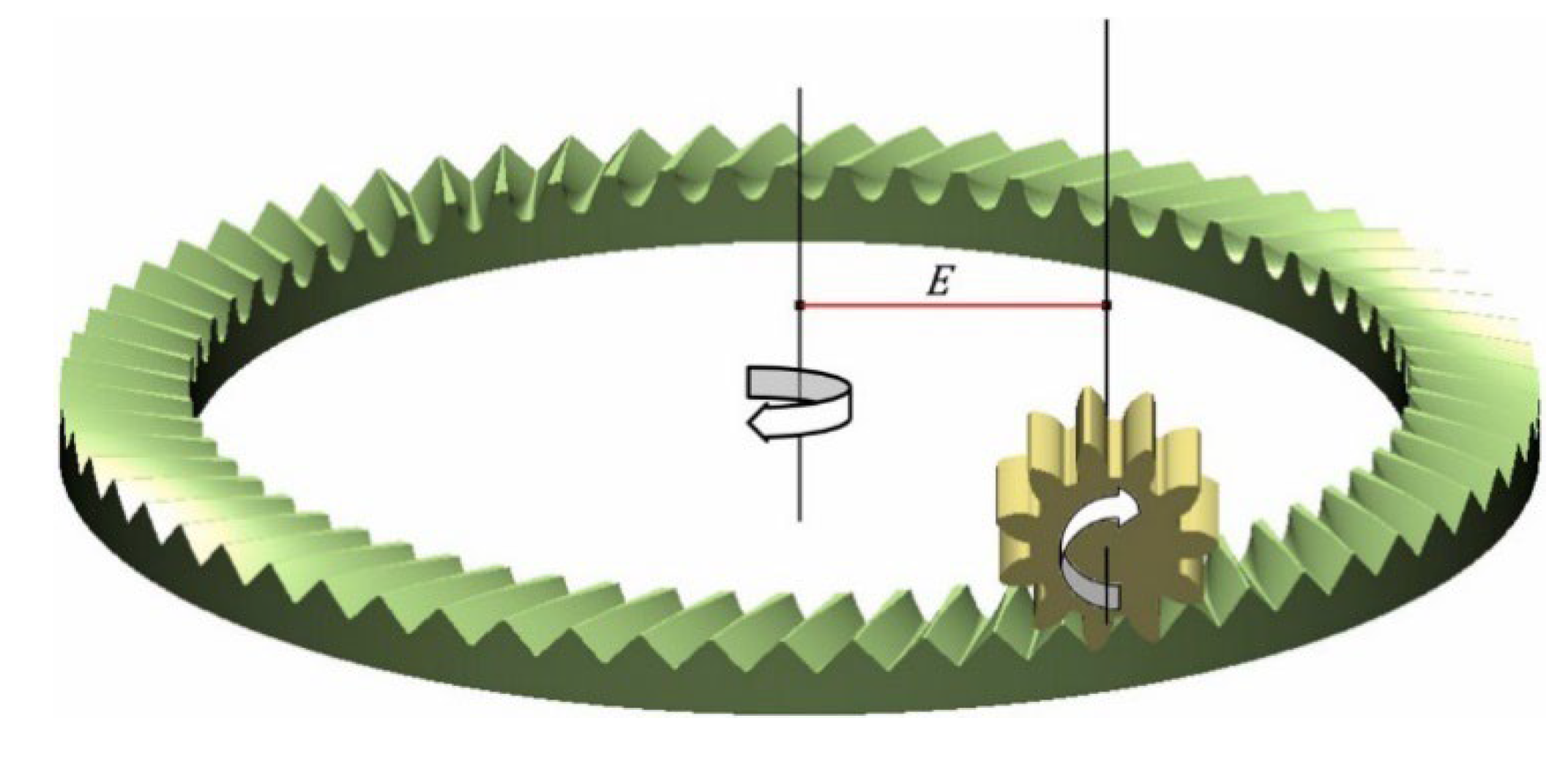

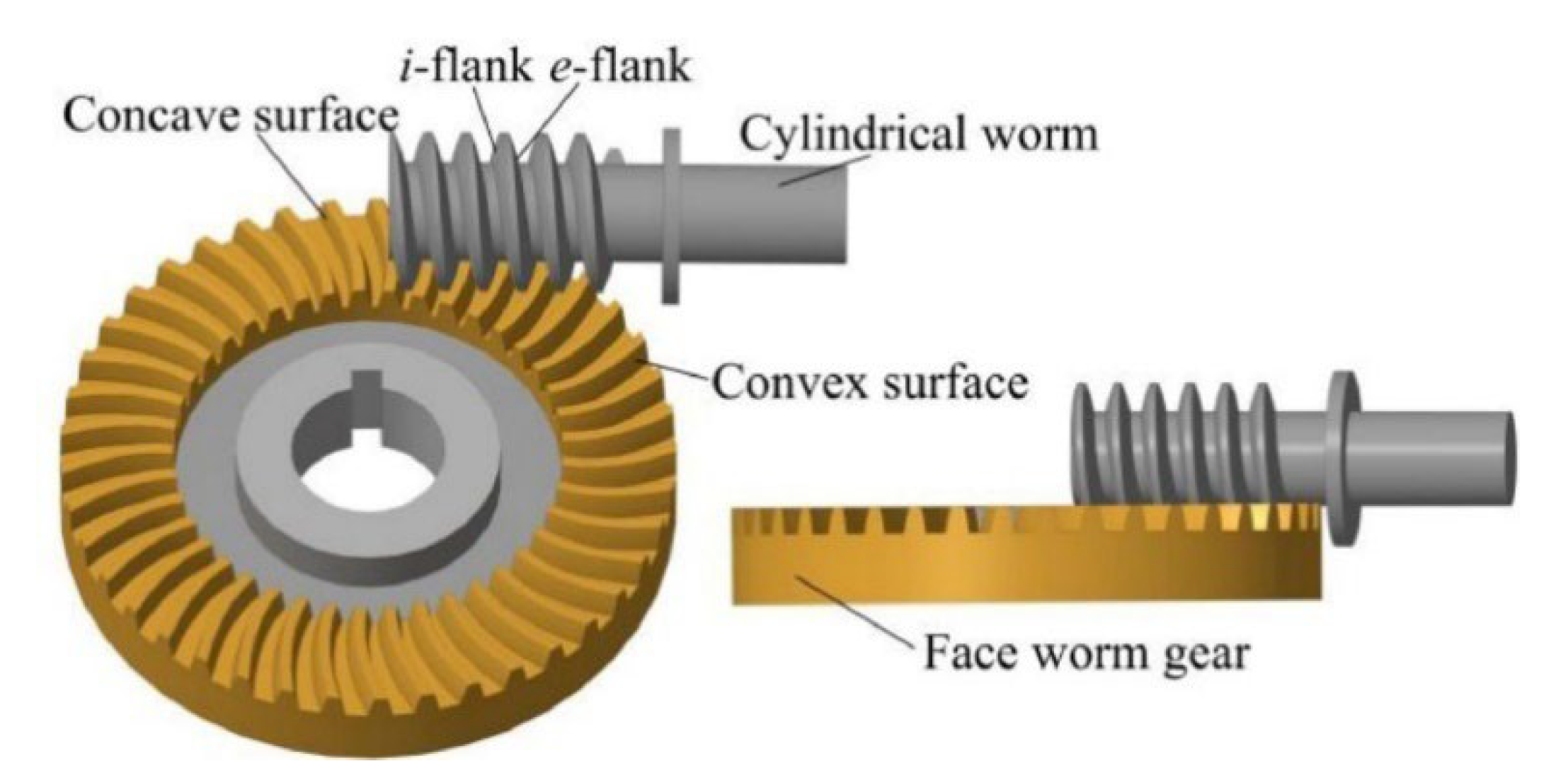

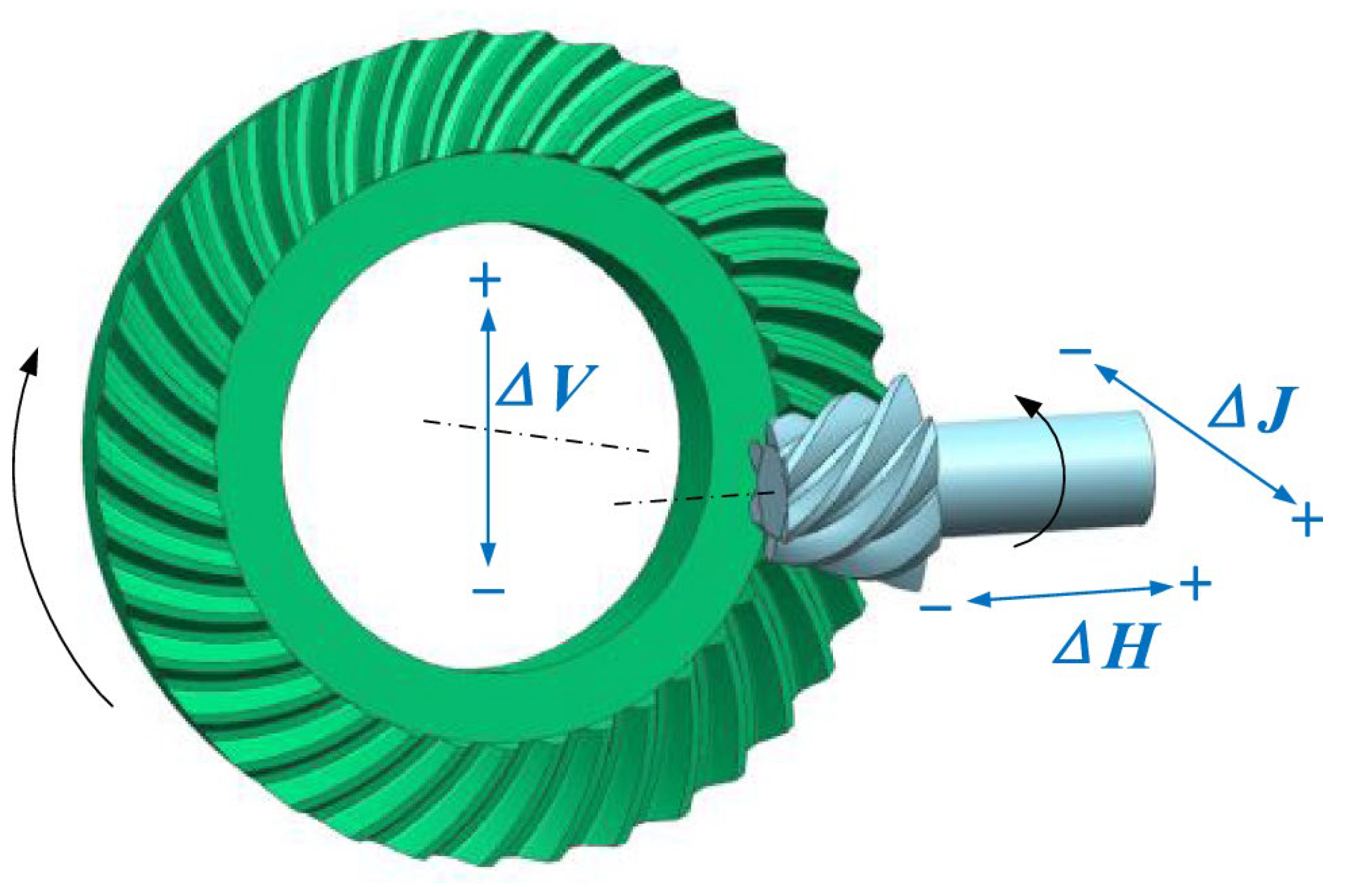

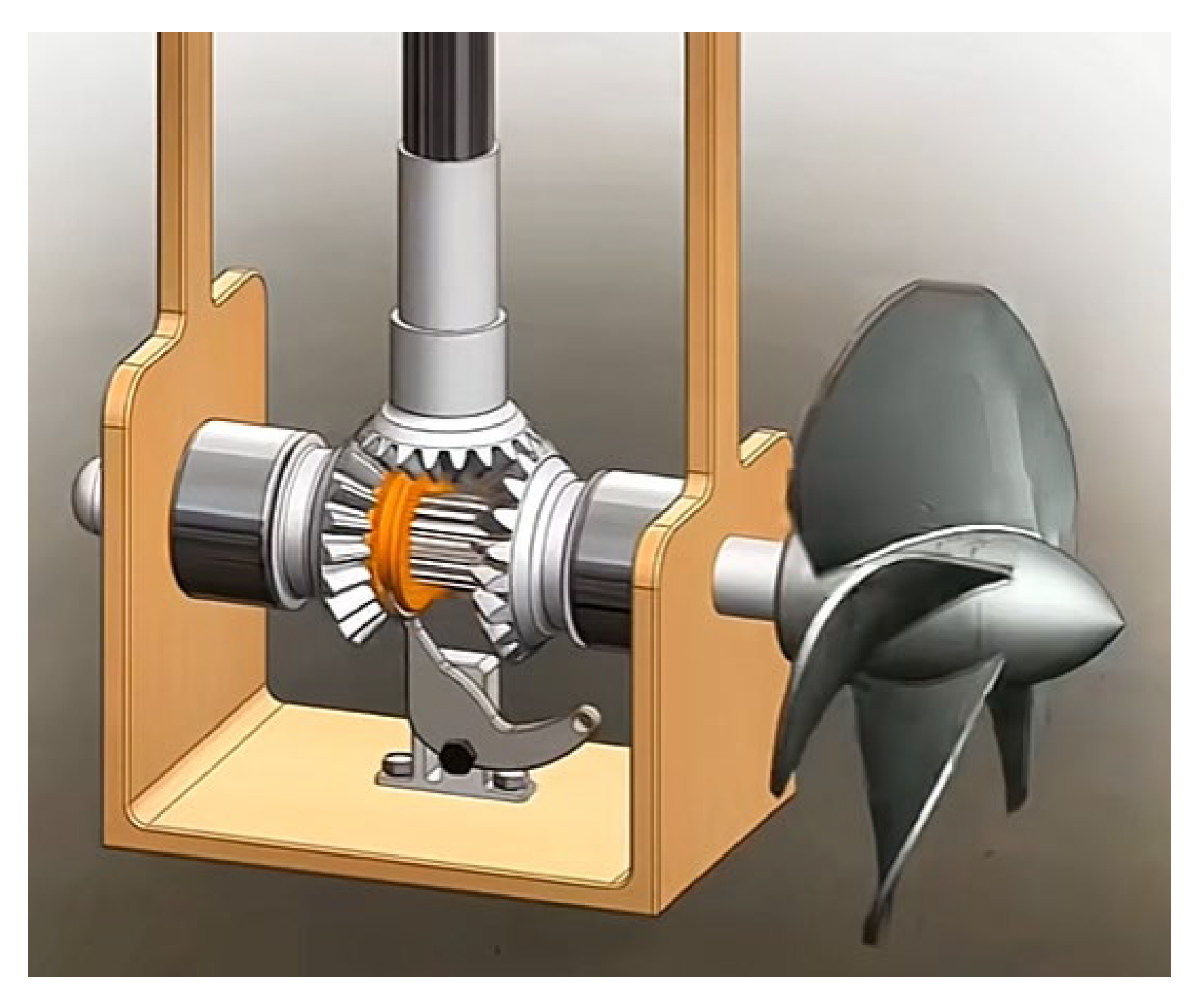

2.1.4. Hyperbolic Gear Mechanism

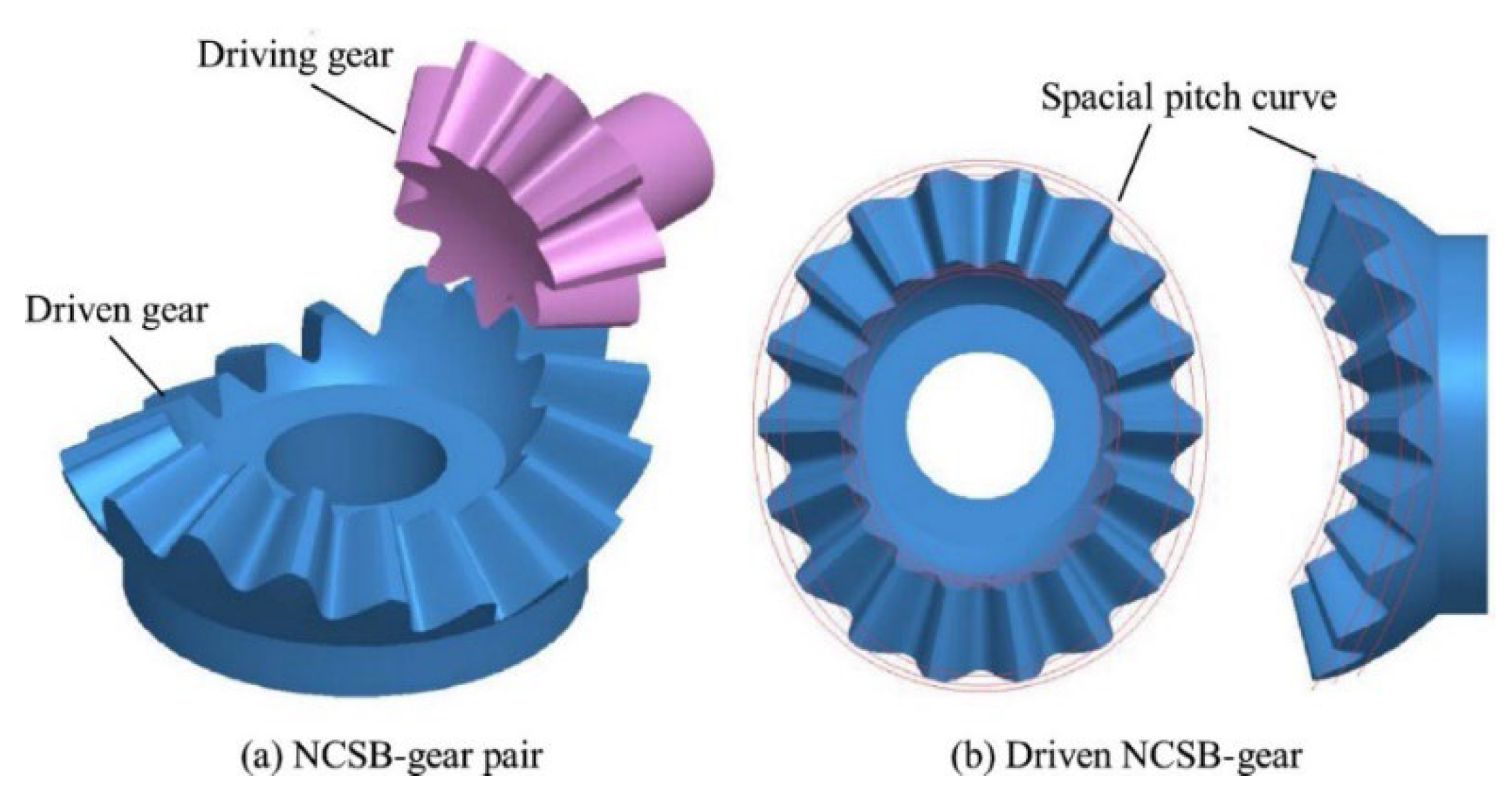

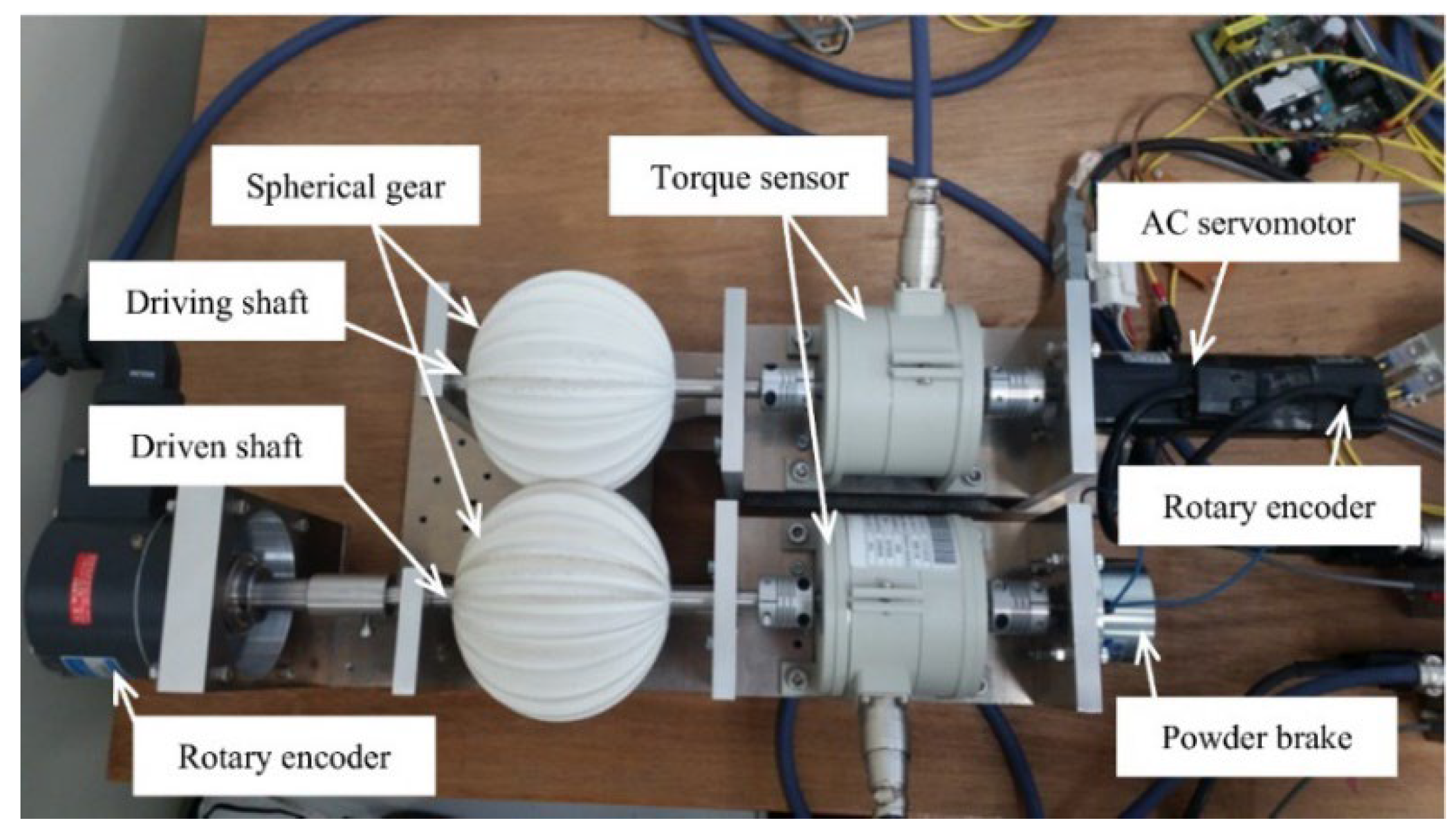

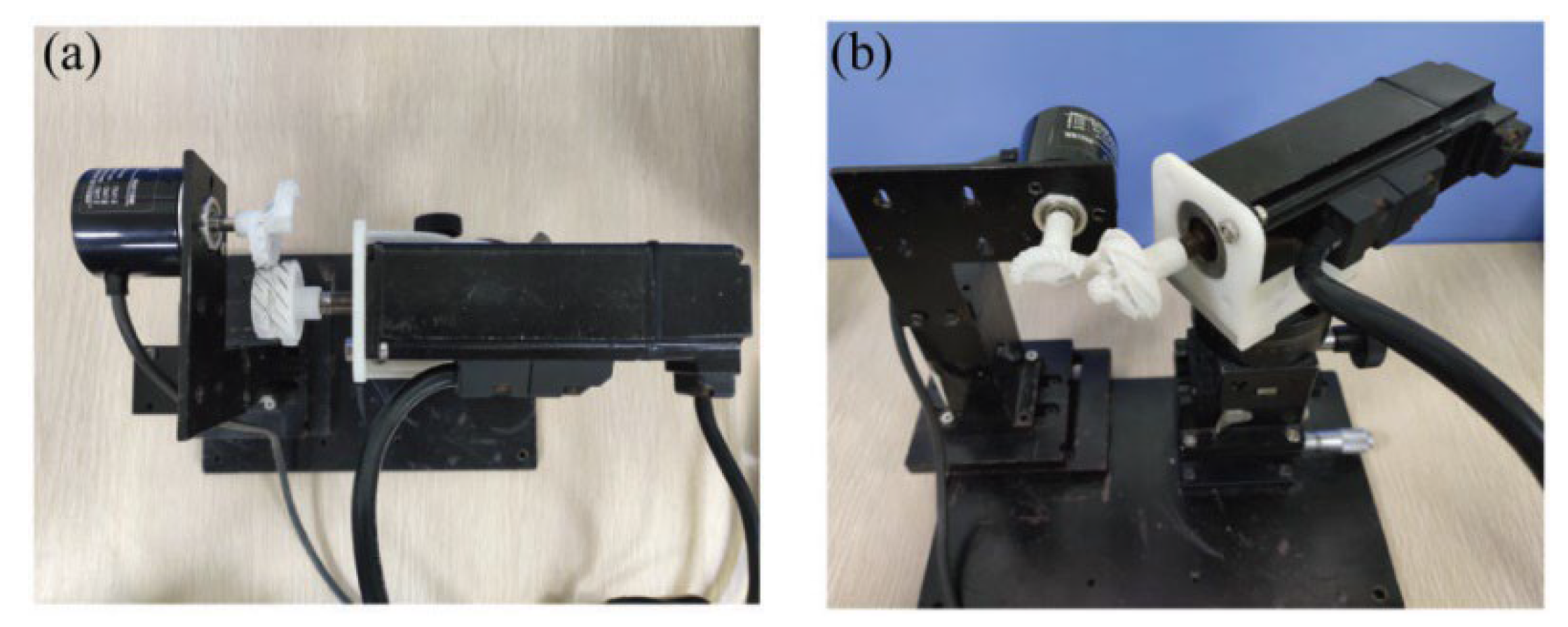

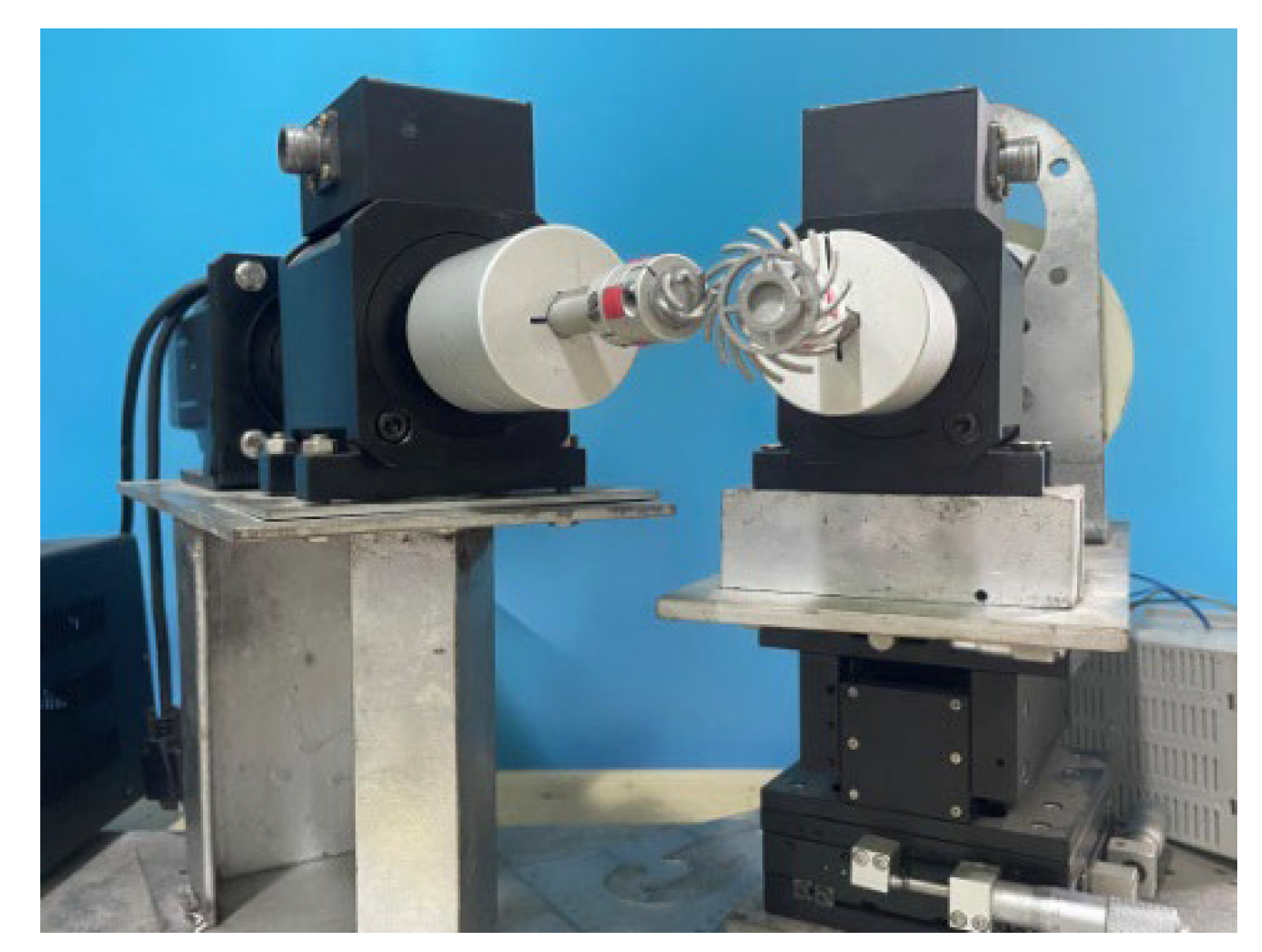

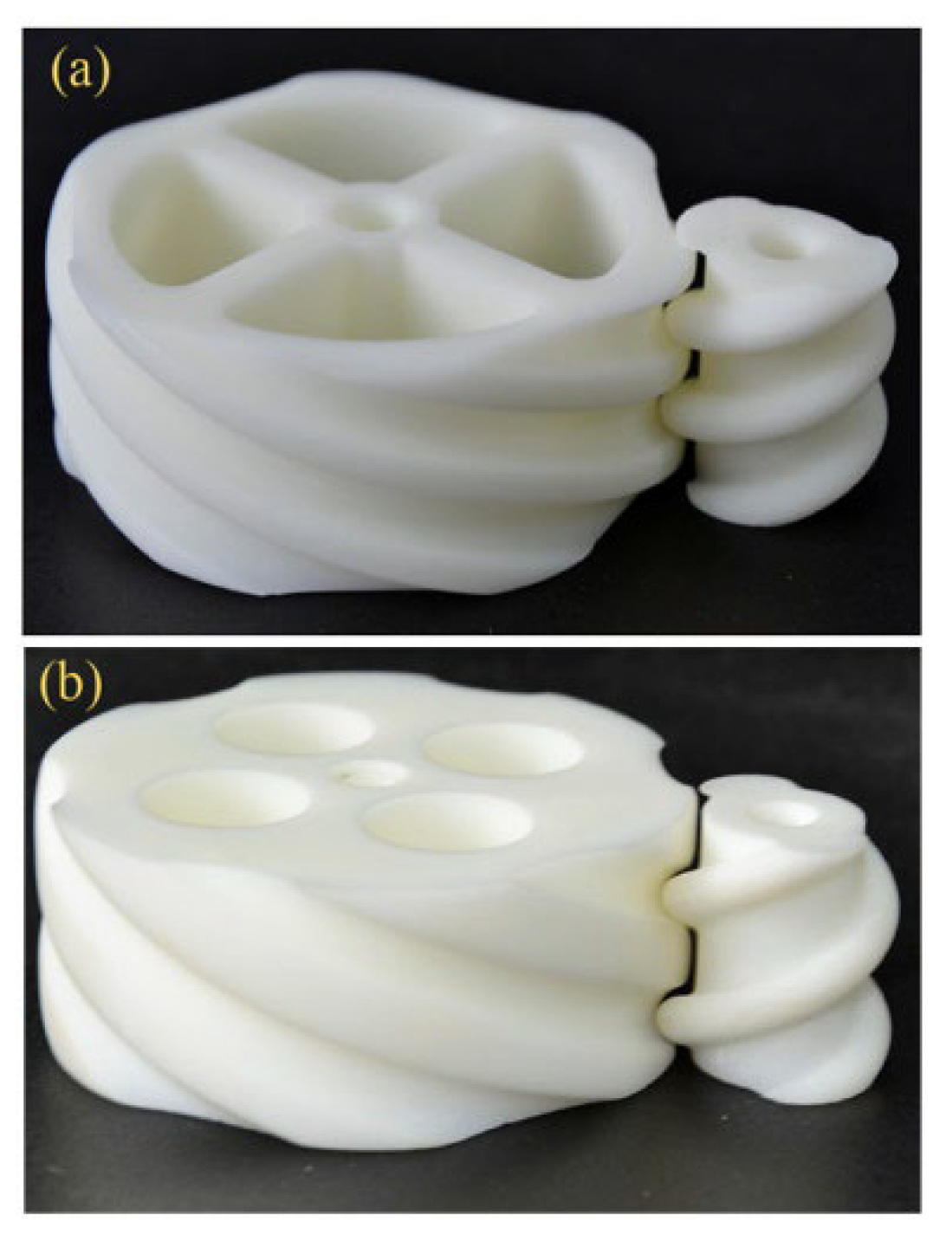

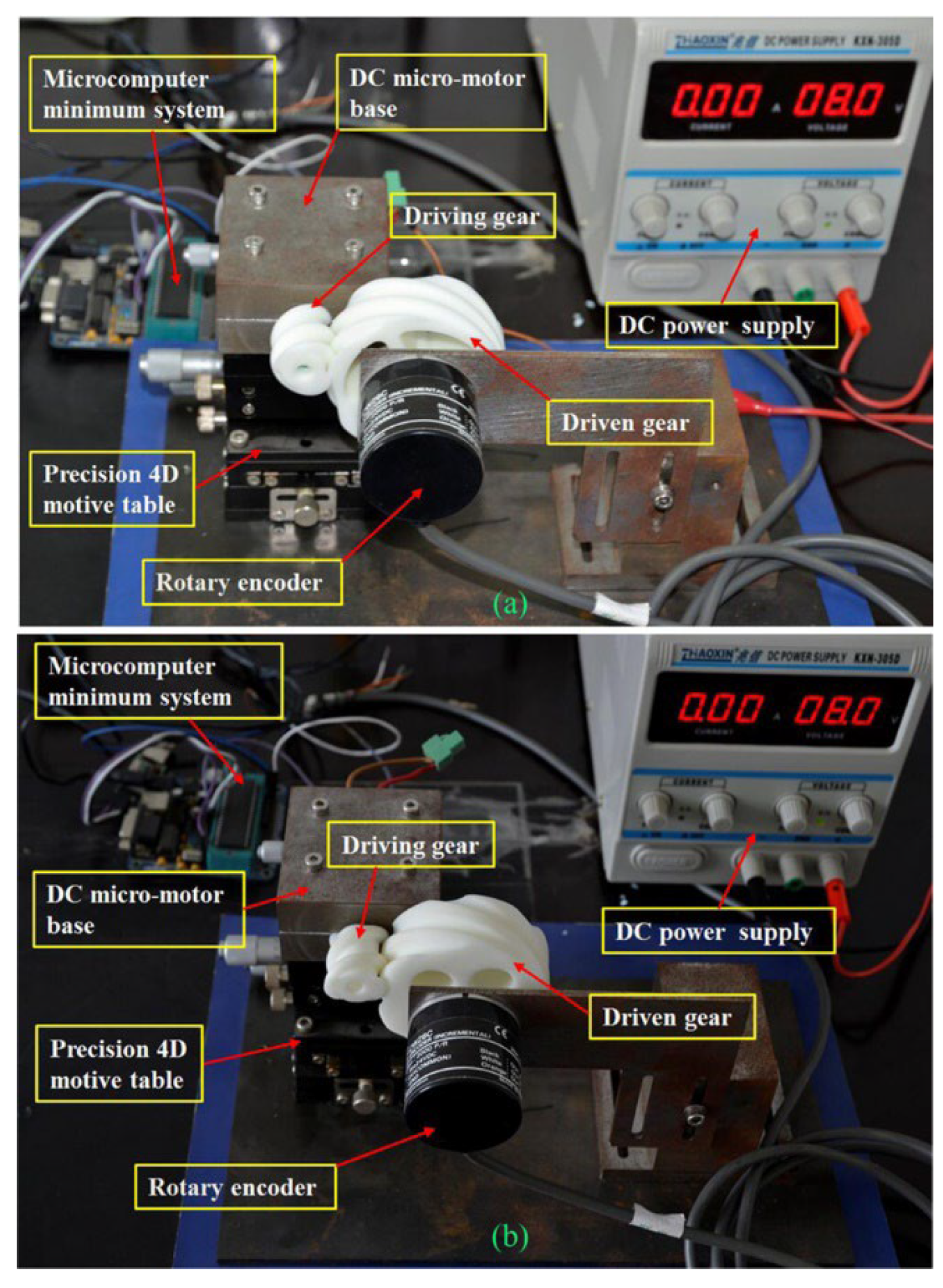

2.1.5. Spherical Gear Mechanism

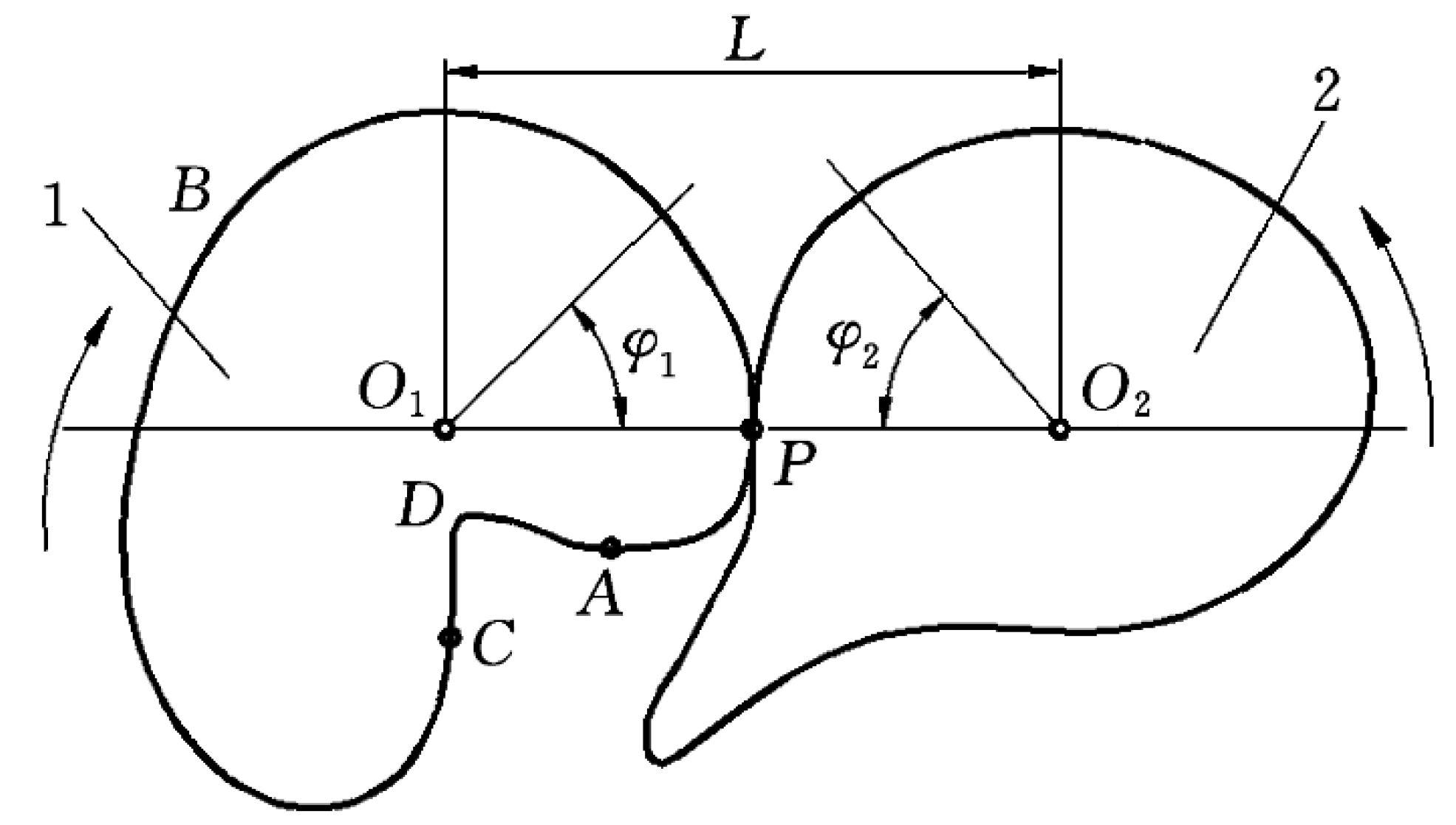

2.1.6. Non Circular Gear Mechanism

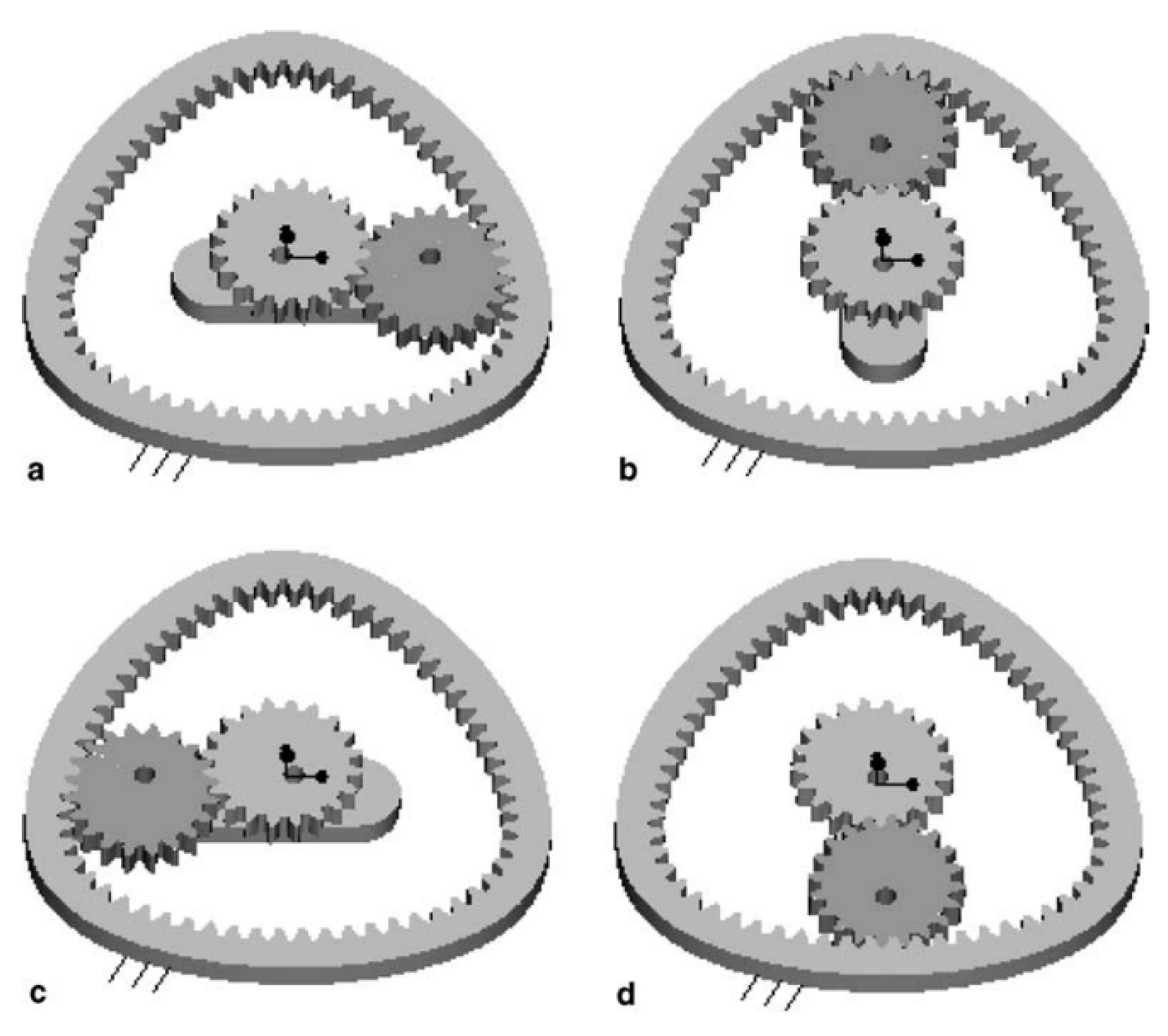

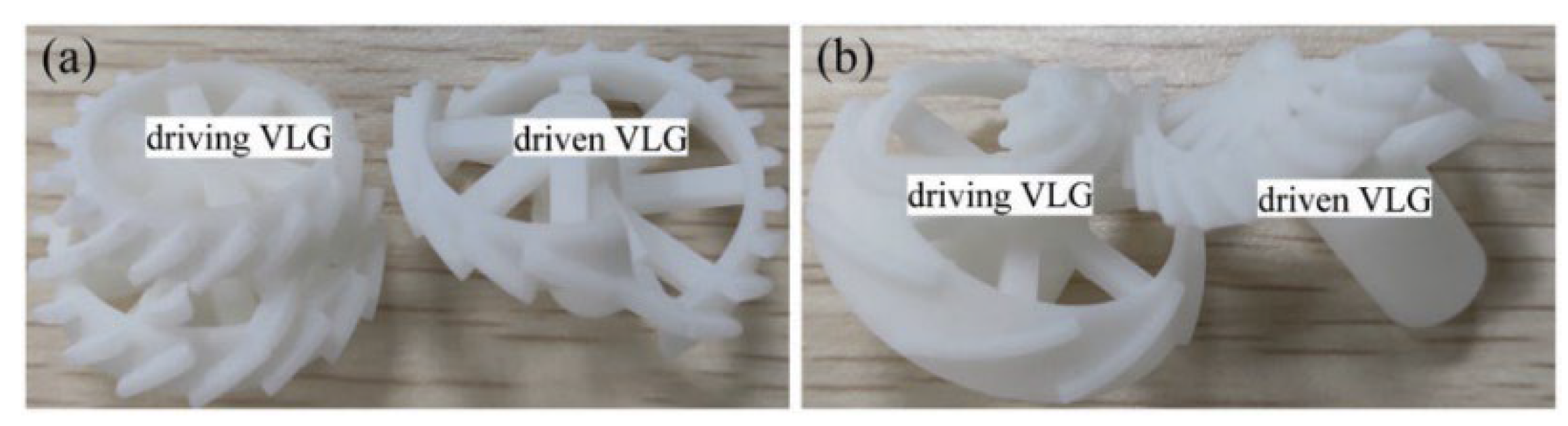

2.1.7. Linear Gear Mechanism

2.1.8. Non Relative Sliding Gear Mechanism

2.1.9. Double Cycloidal Gear Mechanism

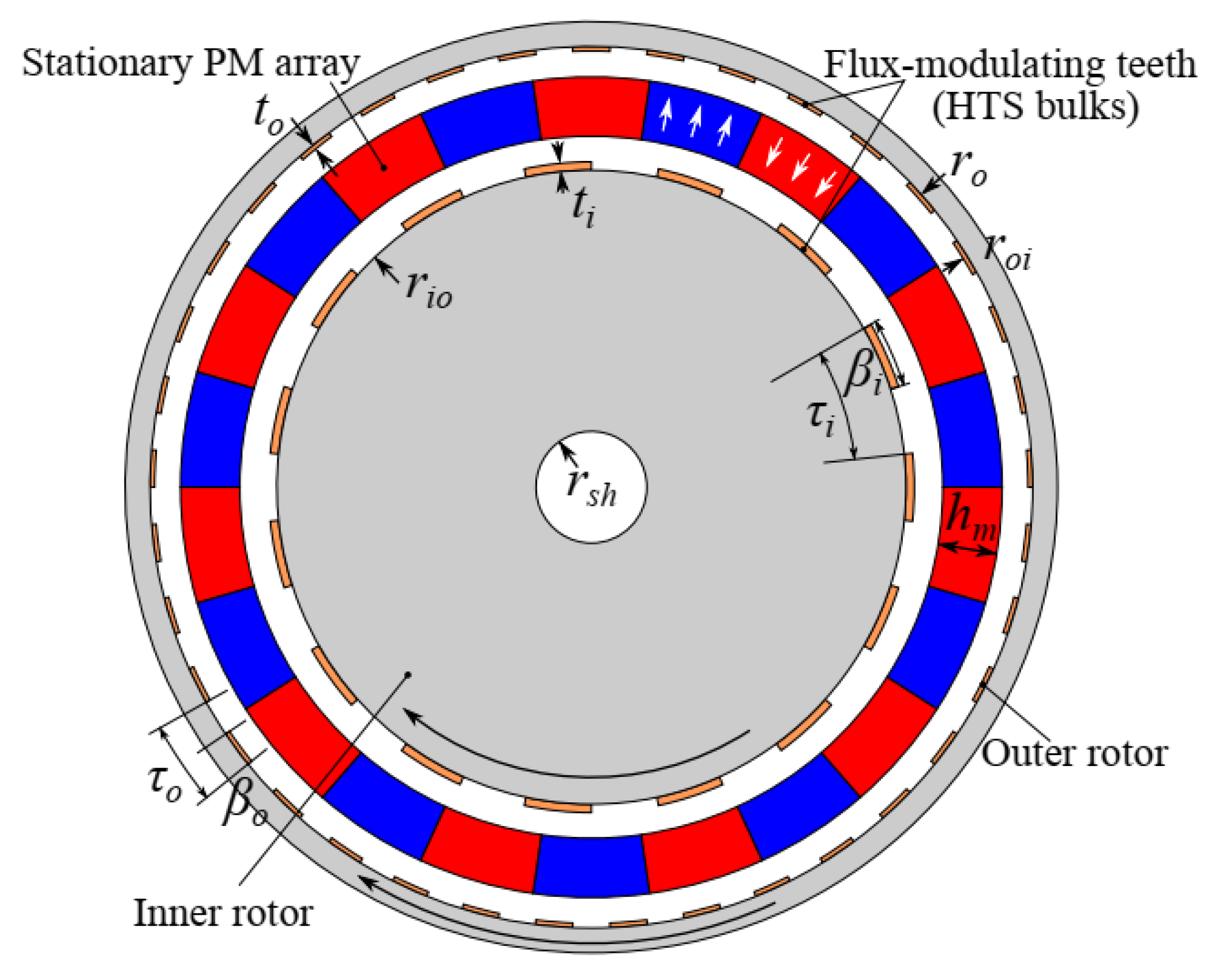

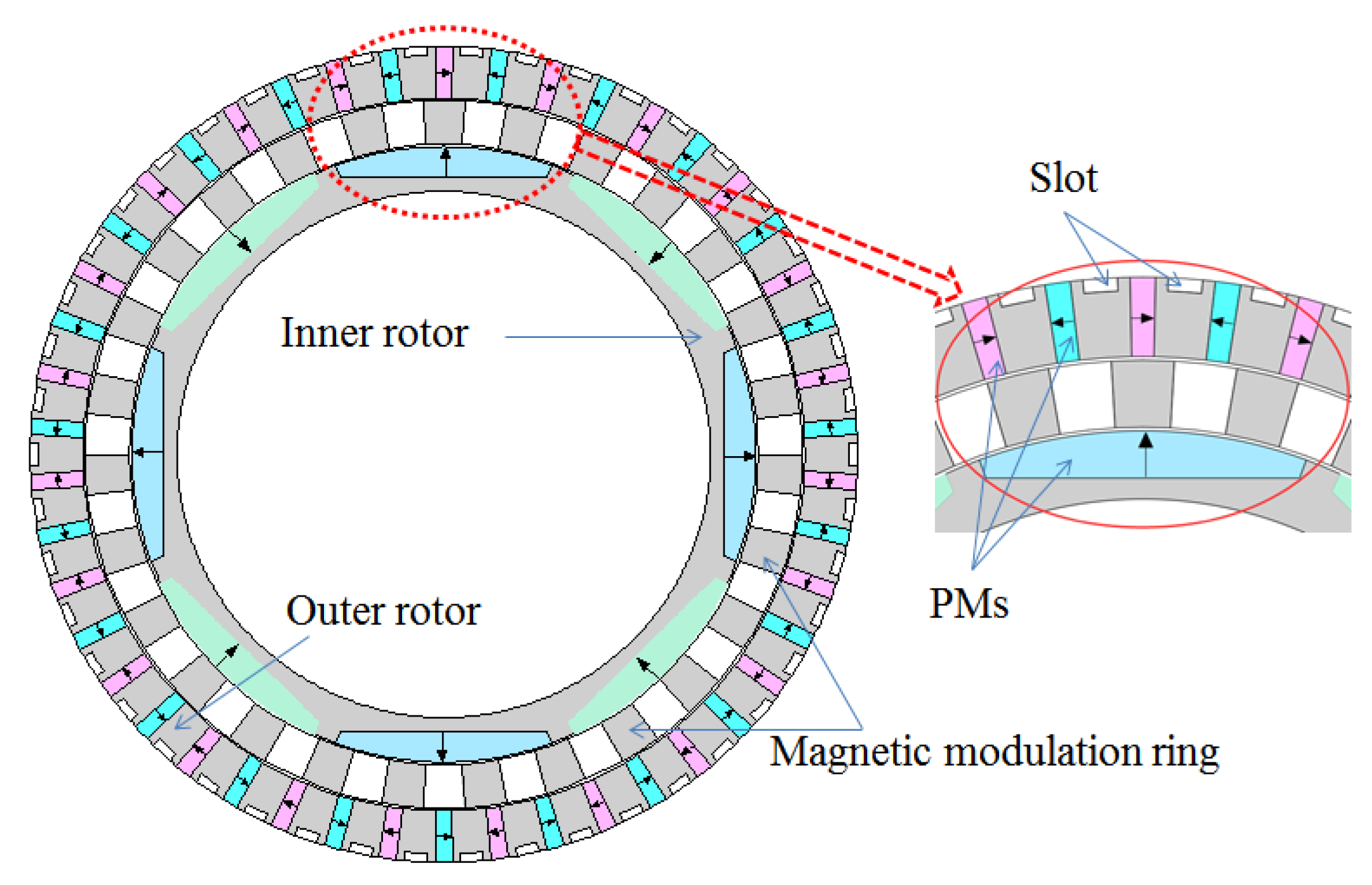

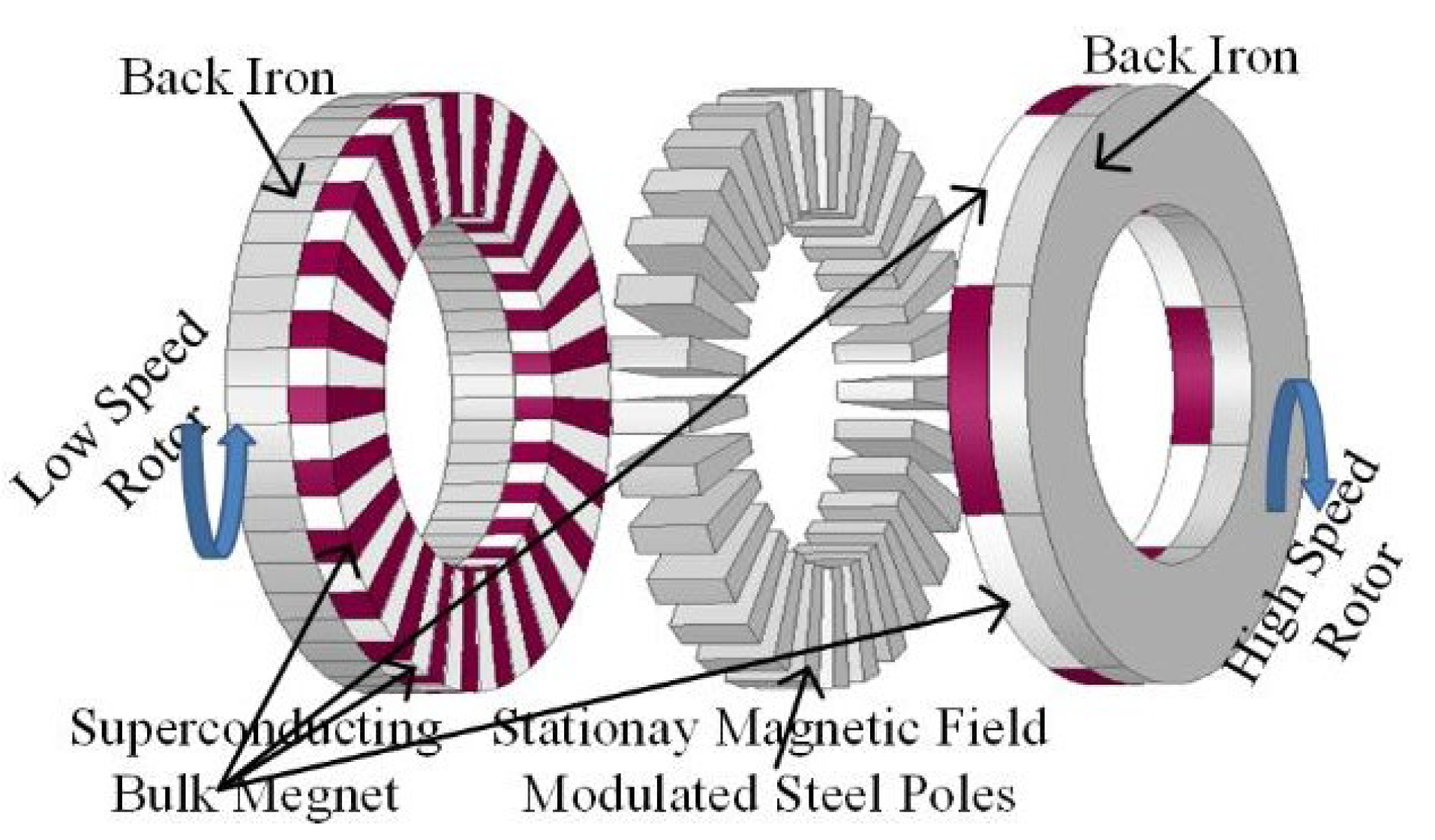

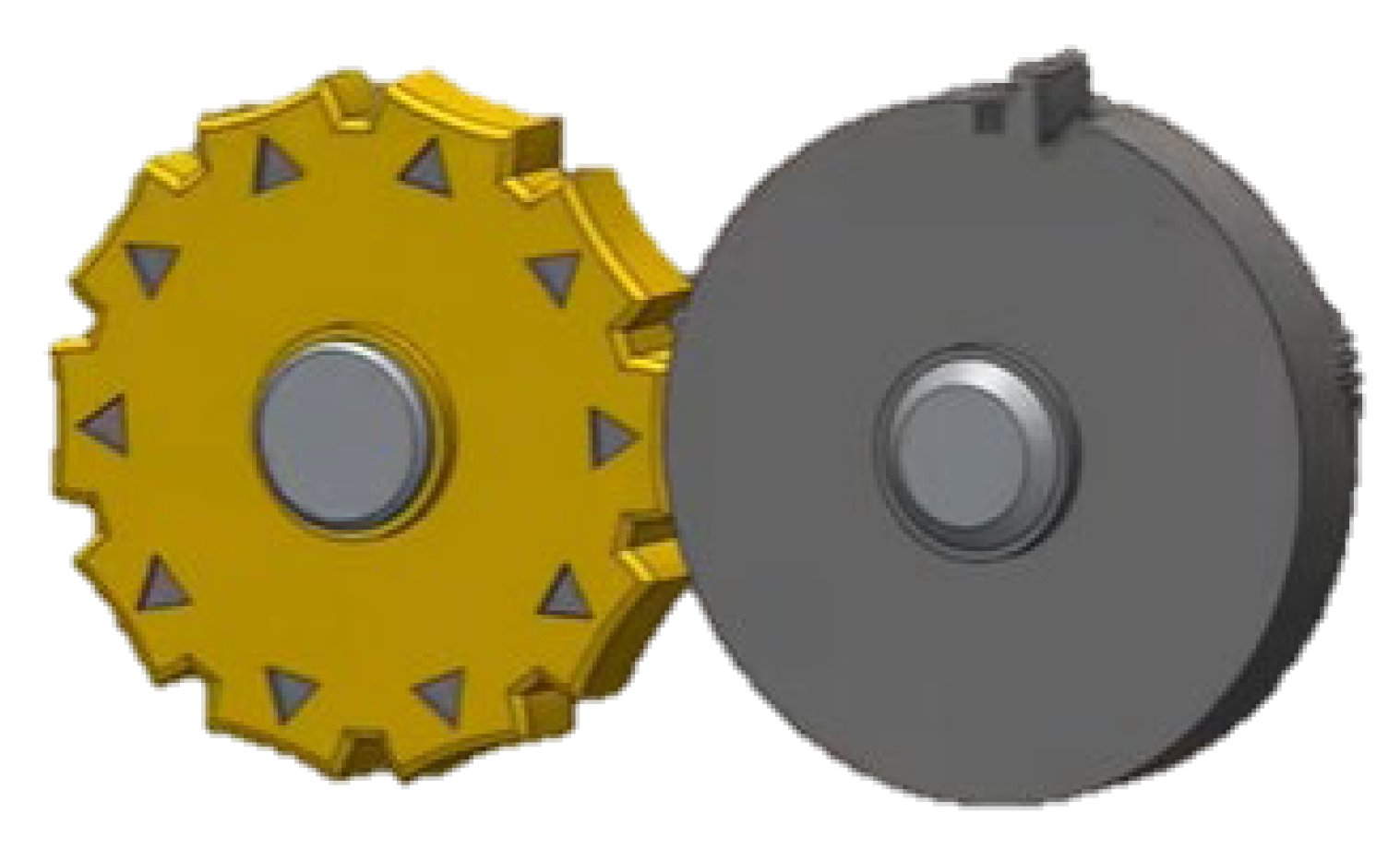

2.1.10. Magnetic gear mechanism

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spur gear [28,29,30] |

High transmission efficiency, simple structure, low tooth surface sliding | High noise level, significant vibration under high load | Machine tool power system, multi-stage transmission device |

| HCR spur gear [32] | High load-bearing capacity, low vibration, and noise | Need to adjust gear parameters (displacement coefficient) | Industrial machinery, heavy-duty transmission systems |

| Helical gear [33,34,35] |

Uniform load distribution, long lifespan, smooth transmission | Generate axial force, requiring additional bearing support | Reducer, General Industrial Equipment |

| Face gear [36,37,38] |

No/low axial force, variable transmission ratio | Asymmetric tooth surface may cause vibration | Robot joints, non-orthogonal axis transmission system |

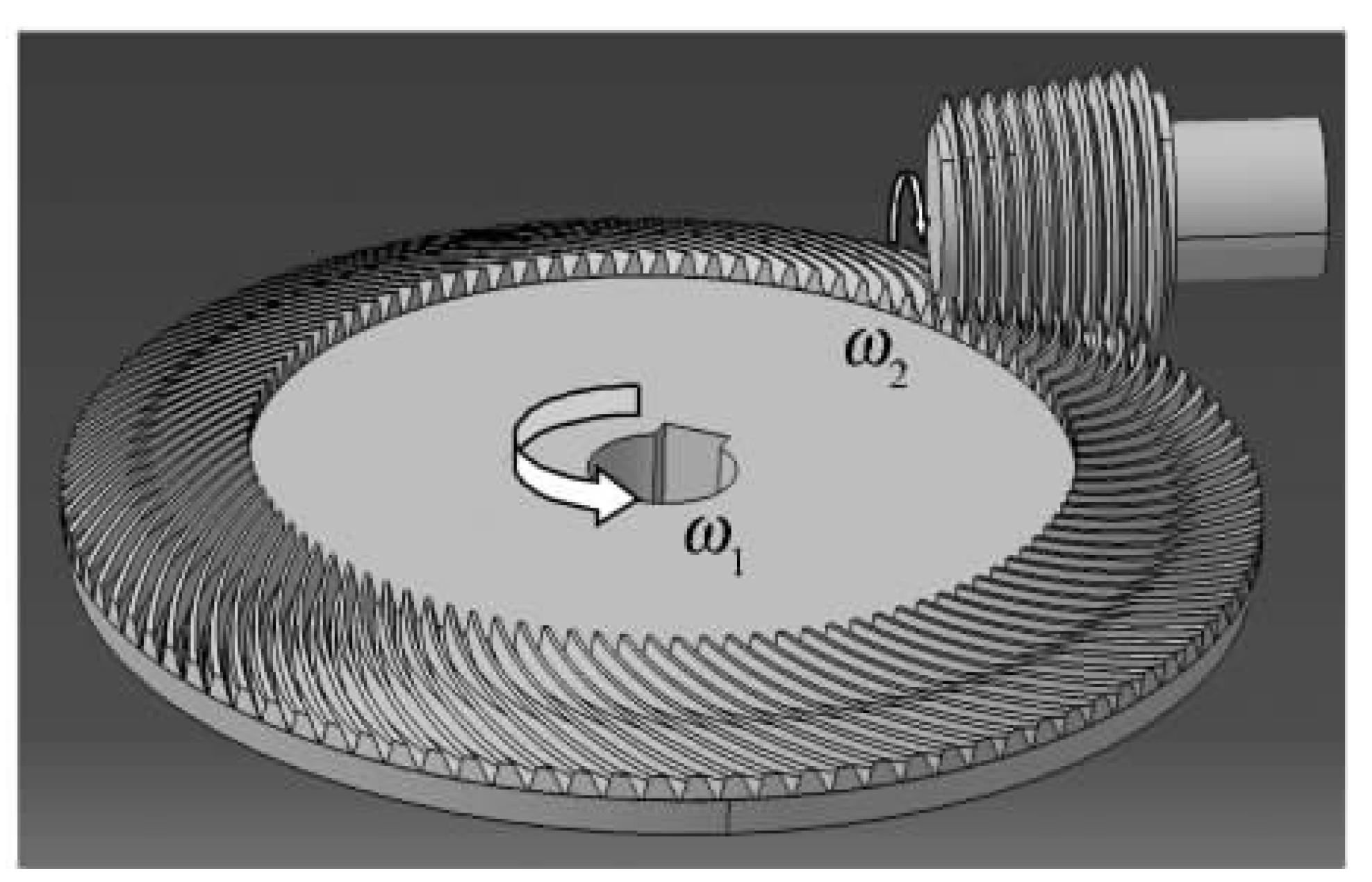

| Worm gear [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] |

High deceleration ratio, low noise, high stability, auto-lock | High sliding friction, low efficiency, lubrication required | Elevators, car steering systems, heavy machinery |

| Straight bevel gear [48] | Simple and Reliable, non-circular spur bevel gears can achieve special functions | High-speed noise is loud and requires axial fixation | Low-speed light load transmission |

| Spiral bevel gear [49] |

High load-bearing capacity, high compatibility, and low noise, smooth transmission | High cost, accurate alignment, and installation are required | Automotive drive axles and reducers |

| Hypoid gear [50,51] |

The chassis height can be flexibly adjusted, high contact rate | Large sliding ratio, easy to wear, requires lubrication | Automotive drive systems, high offset transmission |

| Spherical gear [52,53] |

Multi degree of freedom, lightweight structure | Low output torque, efficiency decreases with increasing shaft angle | Robot flexible joints, drone gimbal, medical minimally invasive surgical equipment |

| Non- circular gear [54,55,56] |

Non-uniform variable speed, high transmission accuracy, compact structure, fast dynamic response | Complex processing and high cost, uneven stress on the tooth surface, prone to local wear | Printing machines, textile machinery, variable transmission bicycles |

| Linear gear [57,58] |

Small size, suitable for micro machinery, wide speed ratio range, zero slip design | High load performance to be verified | High temperature/vacuum environment transmission, micro-robots, lightweight equipment |

| No relative sliding gear [59] | Pure rolling engagement, low friction, low contact stress, and long lifespan | The manufacturing accuracy requirements are extremely high, and installation error sensitivity | High-load precision transmission |

| Double cycloidal gear [60] | Strong impact resistance and minimal tooth surface deformation, smooth transmission, and low noise | The dynamic response needs to be optimized, there may be a delay in the initial meshing | Car seat belt tensioner, high dynamic load machinery |

| Magnetic gear [61,62,63,64,65] |

Contactless transmission, zero wear, low noise, Maintenance free | Dependent on superconducting materials, high manufacturing costs, and complex systems | Precision instruments, renewable energy systems, non-contact transmission |

2.2. Drive Belt Mechanism

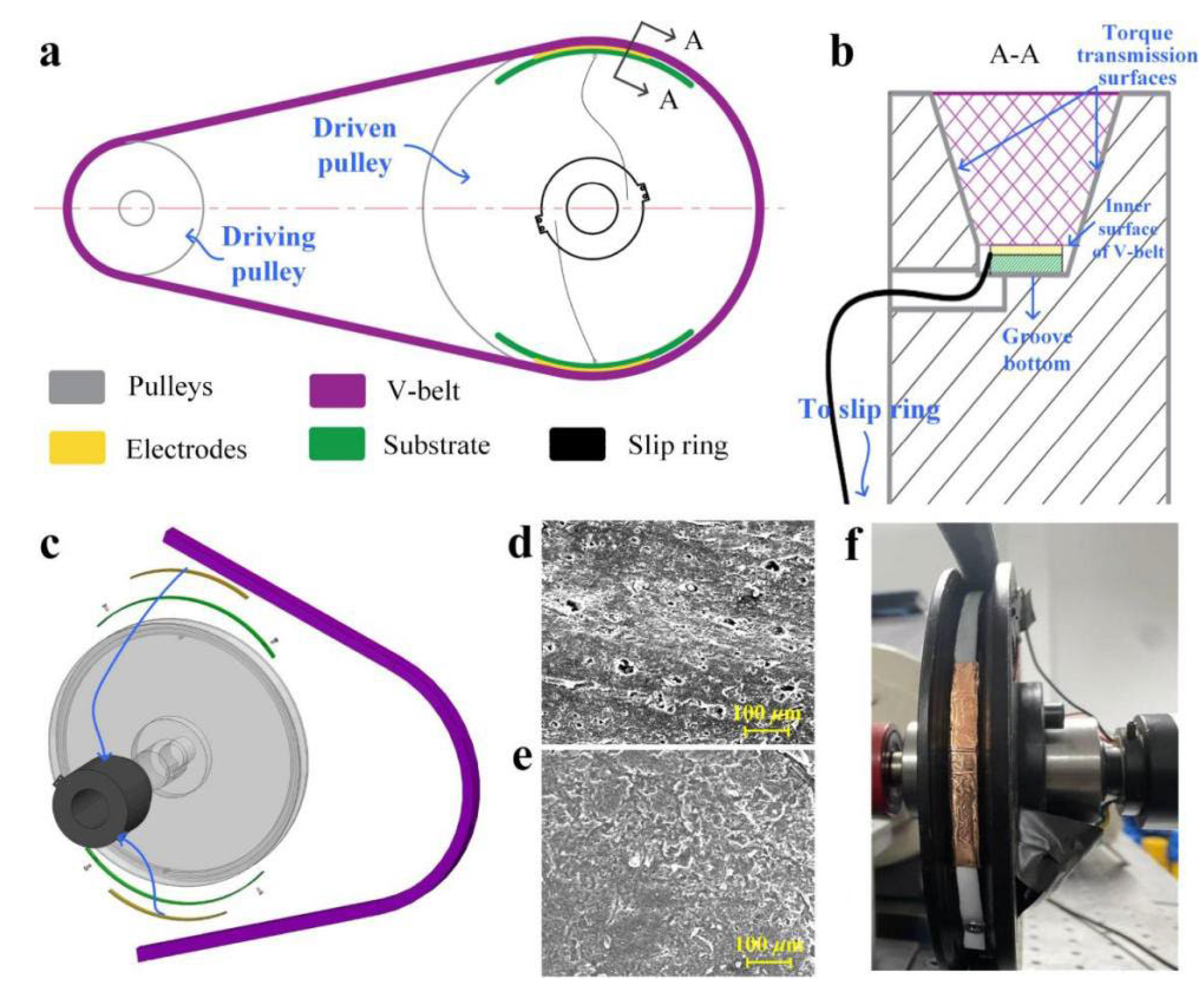

2.2.1. V-Belt

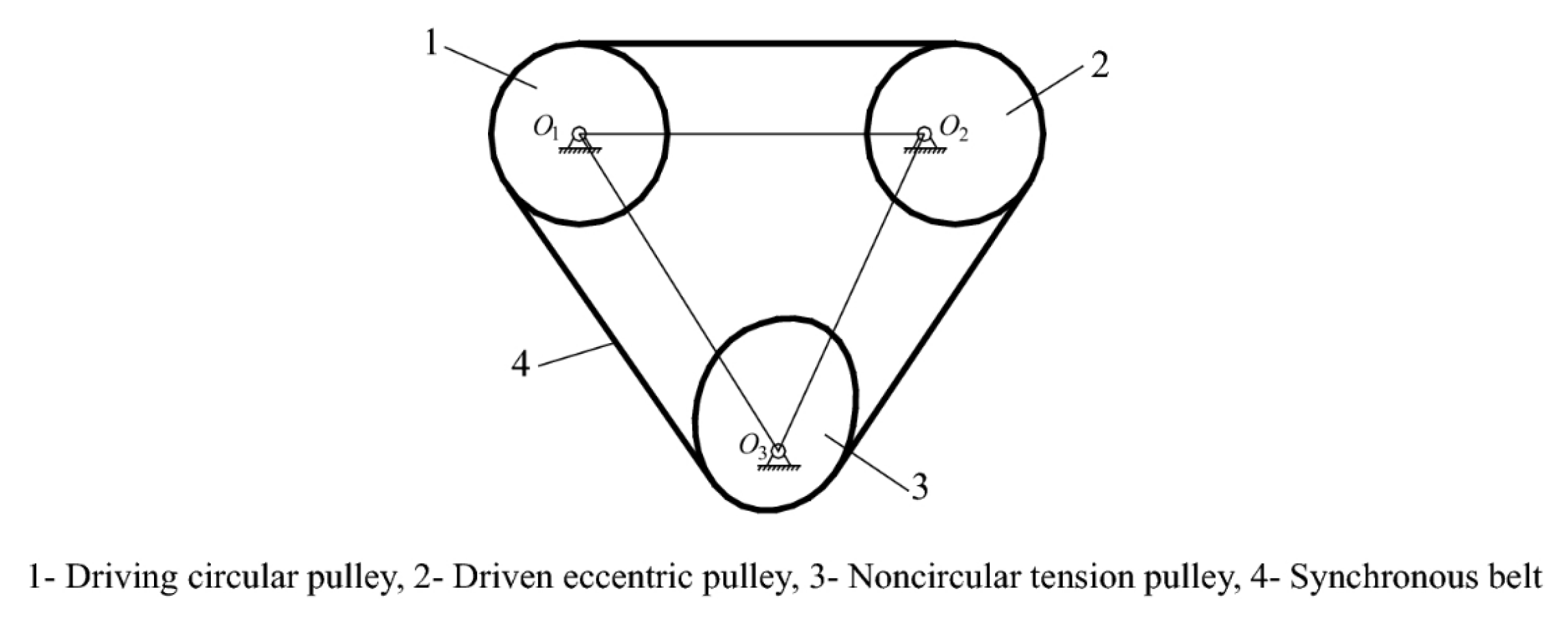

2.2.2. Synchronous Belt

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional V-belt drive [66,67,68,69] | Vibration absorption, high transmission ratio, overload protection | Low reliability, short lifespan | Automobiles, ship engines, industrial robots, etc. |

| V-belt drive (TVB system) [70] | Real-time monitoring and fault diagnosis, high reliability, and long lifespan | Affected by high humidity or high-temperature environment | Conveyor belts and small mechanical transmissions that require long-term monitoring |

| Synchronous belt drive (traditional non-circular) [71] | Specific non-uniform motion or velocity variation | The belt is loose and the transmission stability is poor | Machinery requiring non-uniform transmission |

| Synchronous belt drive (new nonlinear) [71] | Maintain tension on the belt; High stability, suitable for environments with poor lubrication | Extra non-circular tensioning wheels are required, with a complex structure | Machinery with precise speed changes for long-distance transmission |

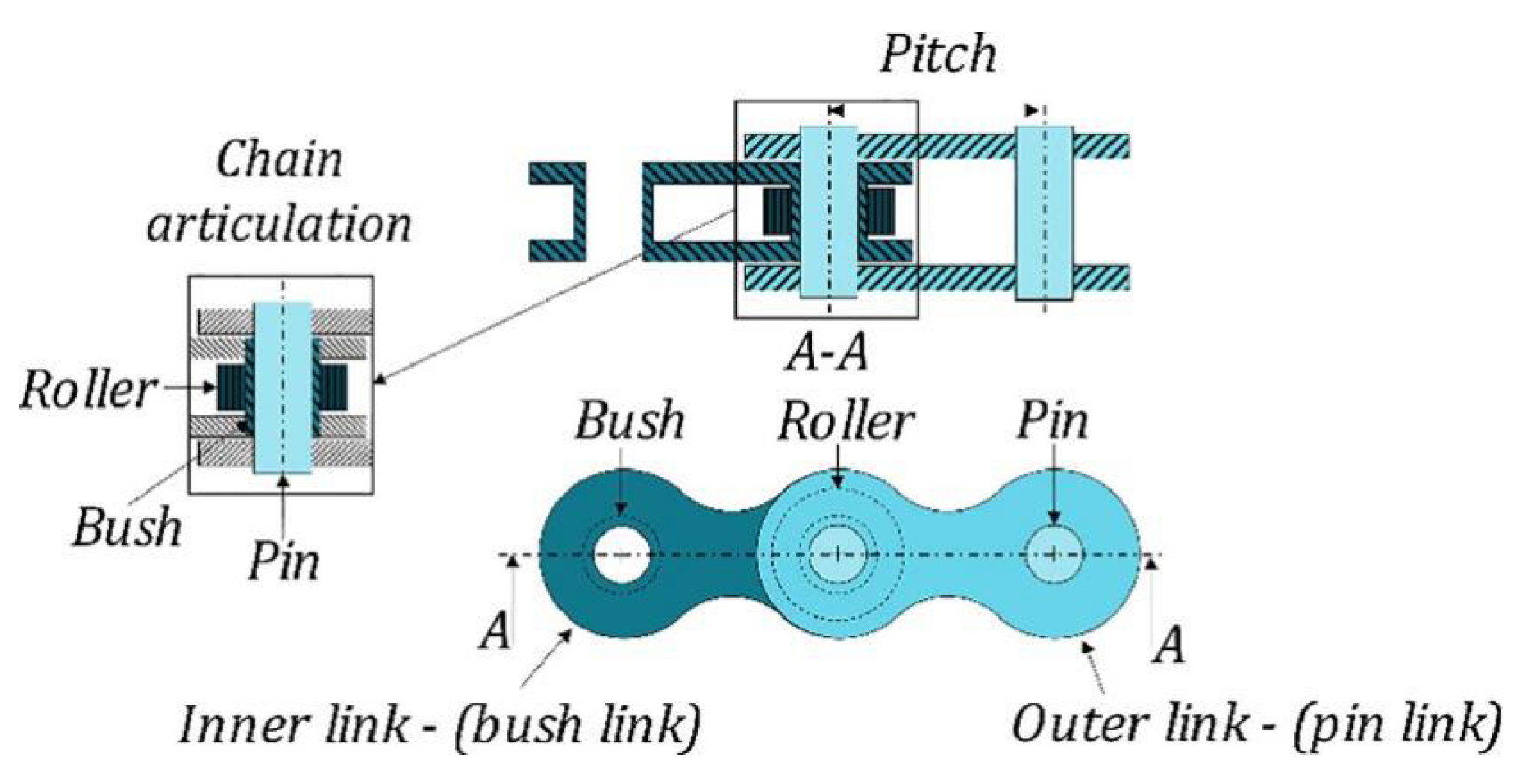

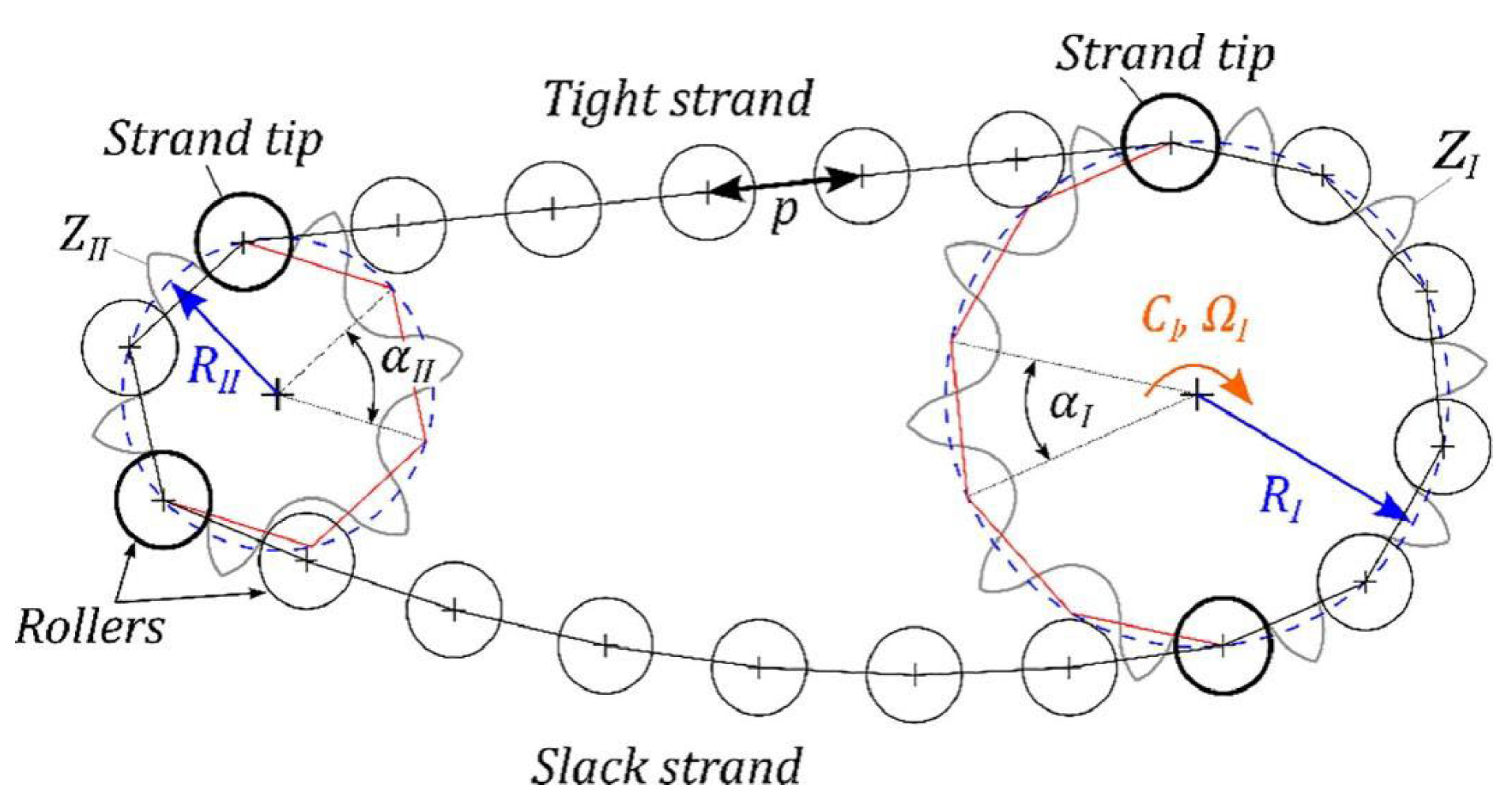

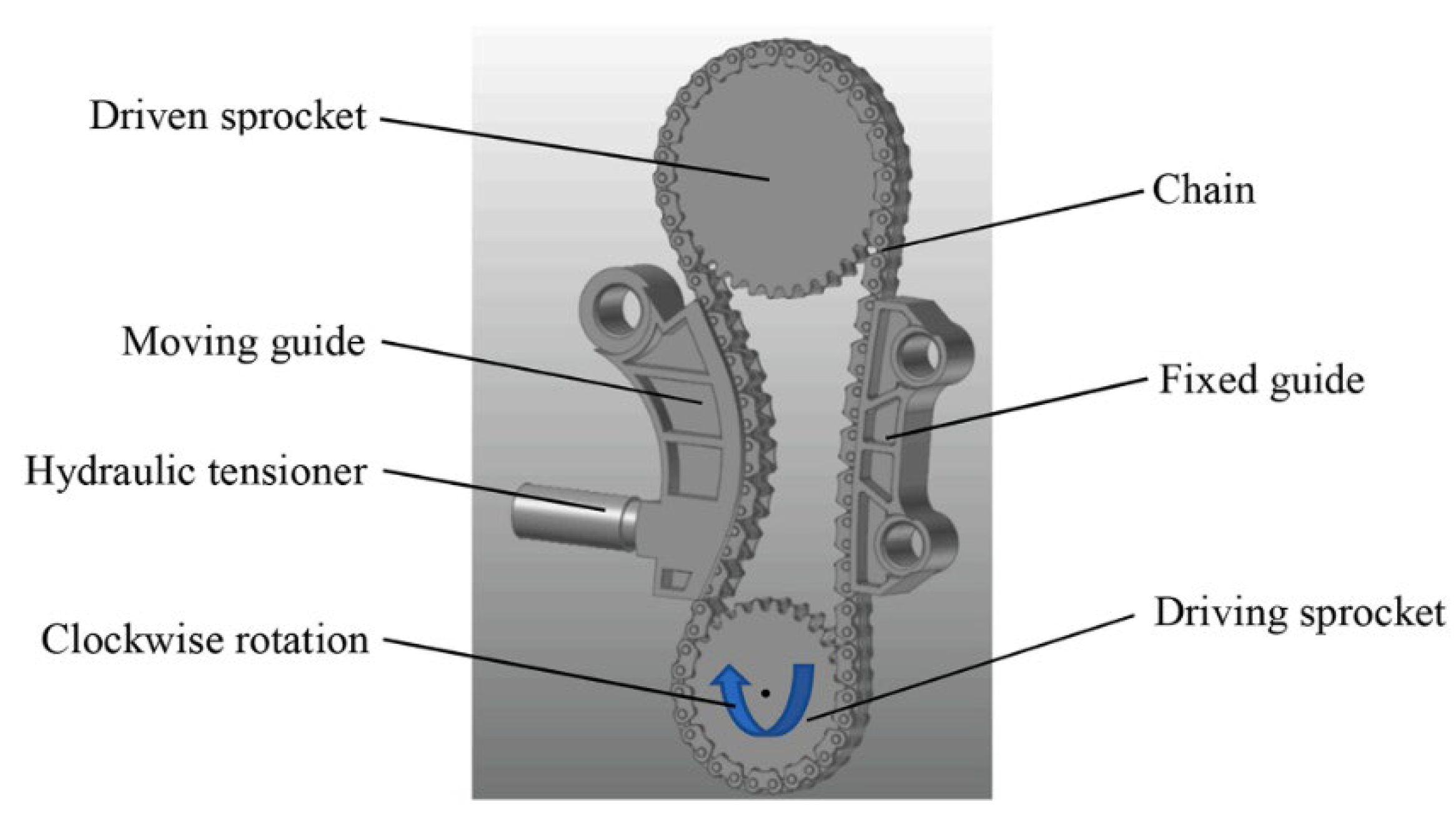

2.3. Chain Wheel Mechanism

2.3.1. Single-Row Chain Drive

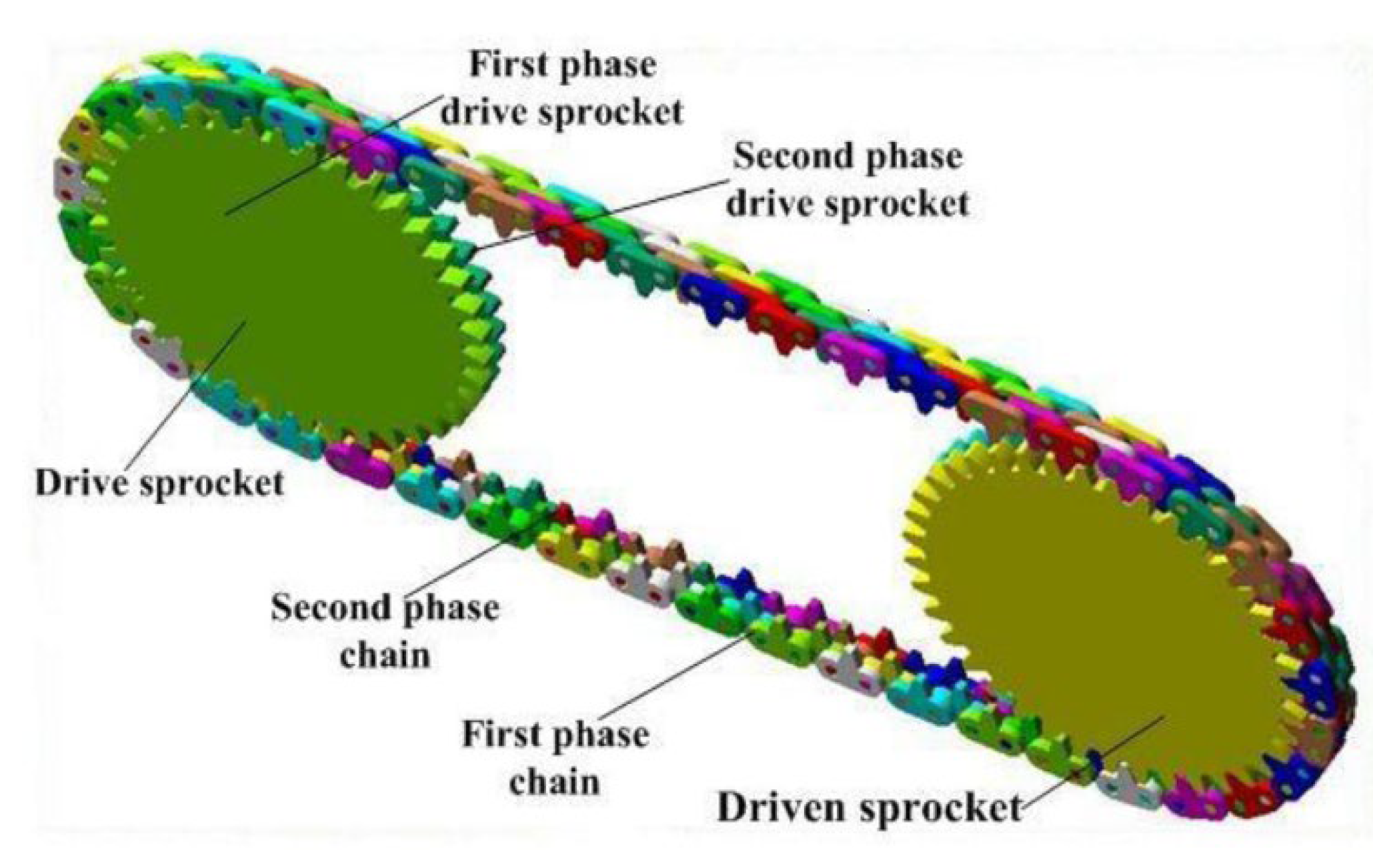

2.3.2. Multi Row Chain Drive

2.3.3. Silent Chain Drive

2.3.4. Composite material chain drive

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single row chain drive [72,73] | Simple structure, easy maintenance, long lifespan, and low cost | High noise, lubrication required, low precision, and easy to vibrate at high speeds. | Bicycles, motorcycles, and other low-load scenarios |

| Multi row chain transmission [74] | Strong load-bearing capacity, high material utilization rate, and reduced stress concentration in molds. | High requirements for processing equipment and precise control of parameters. | Industrial machinery, long-distance or high-load scenarios. |

| Silent chain drive [75] | Low noise | Torque and speed are limited | Engines, machine tools, and other high-speed transmission devices |

| Bidirectional chain drive [76] | High transmission accuracy and efficiency, good durability | High installation accuracy, heavy-weight, and complex structure | High-speed, high-precision, and lightweight transmission system |

| Composite material chain drive [77] | Lightweight, energy-saving, corrosion-resistant, noise-reducing, and vibration-reducing | The anti-fatigue ability is affected by the proportion of PU, resulting in high-cost | Corrosion-resistant, lightweight, and low-load scenarios |

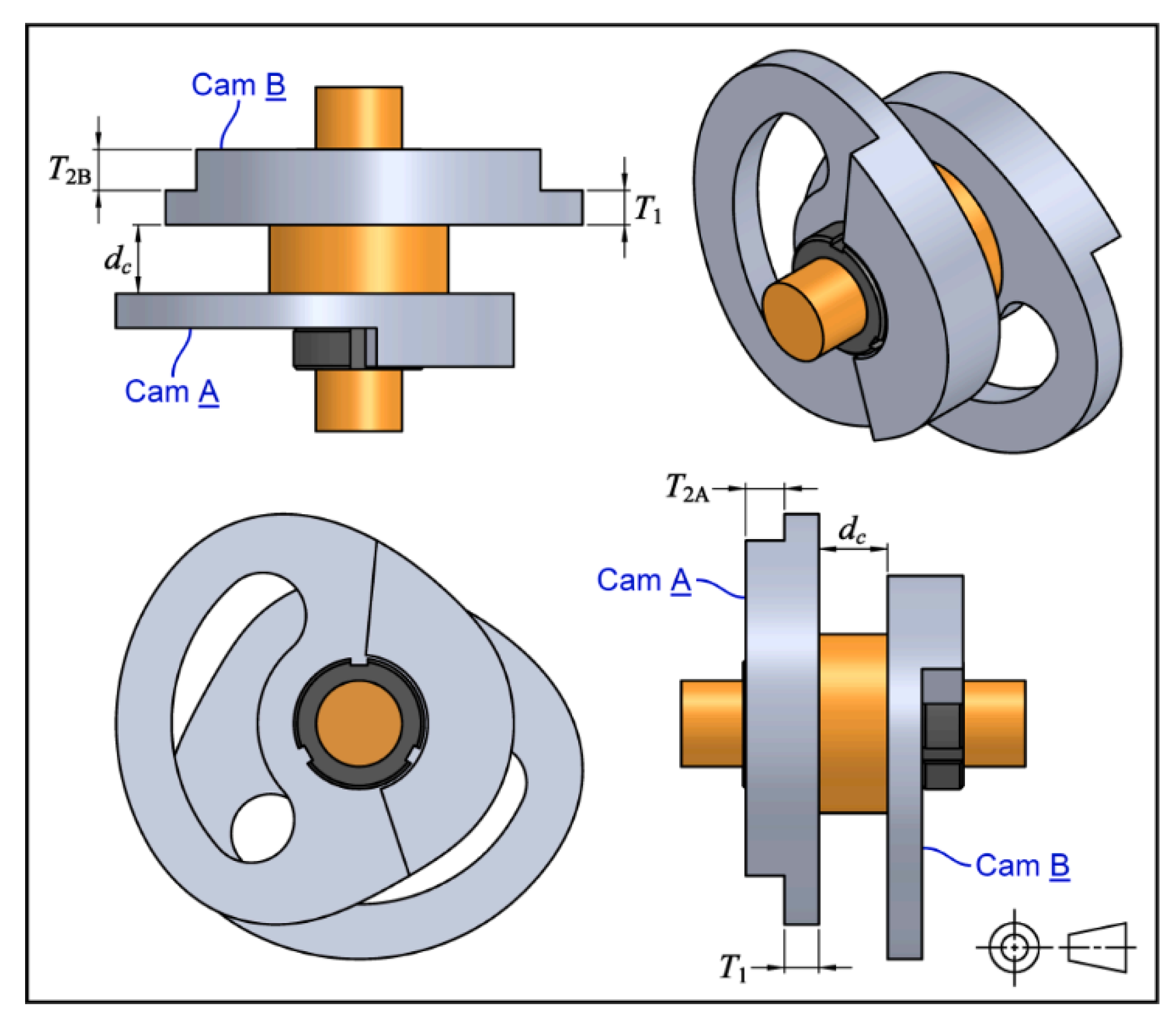

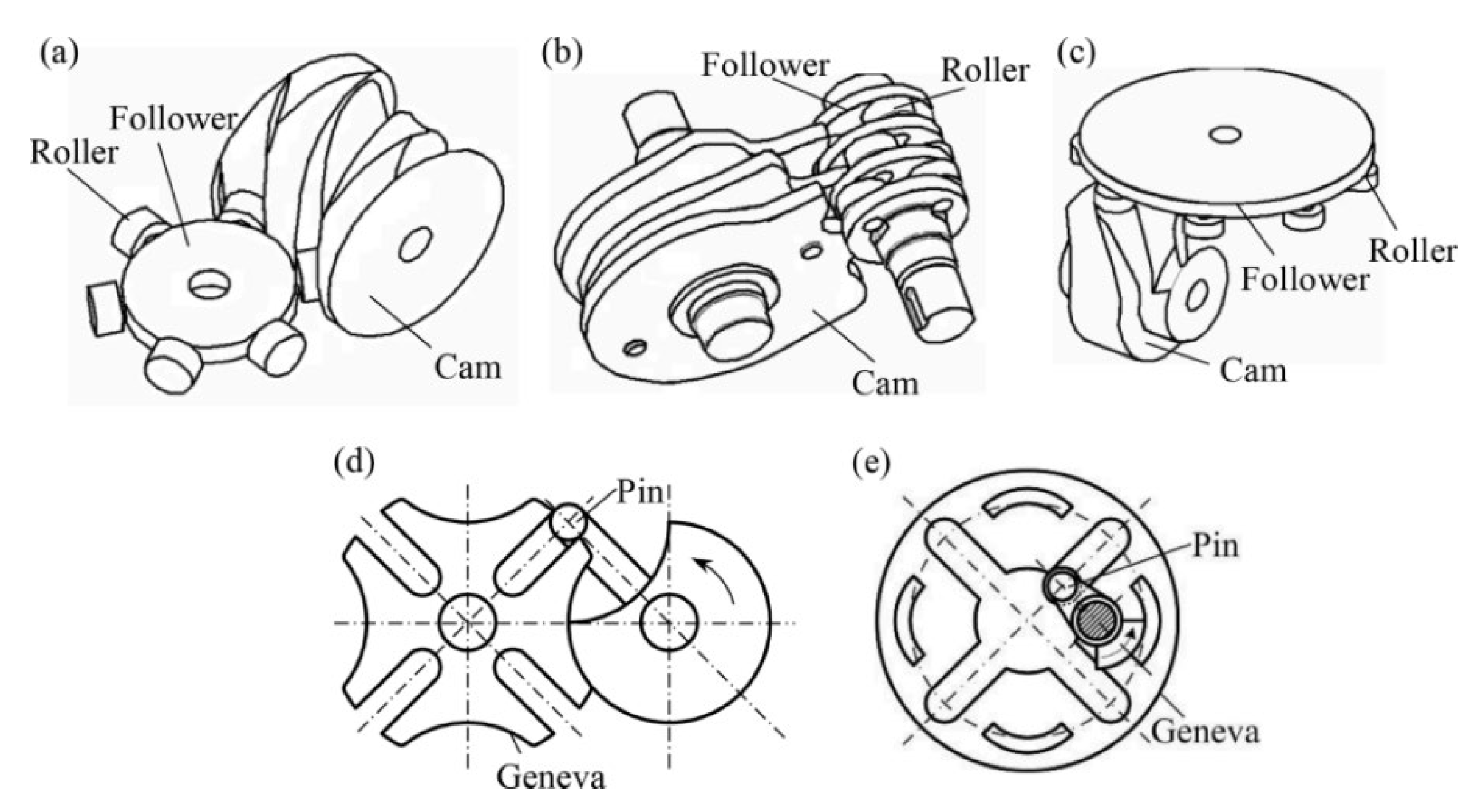

2.4. Cam Mechanism

2.4.1. Cam Roller

2.4.2. Conjugate Cam

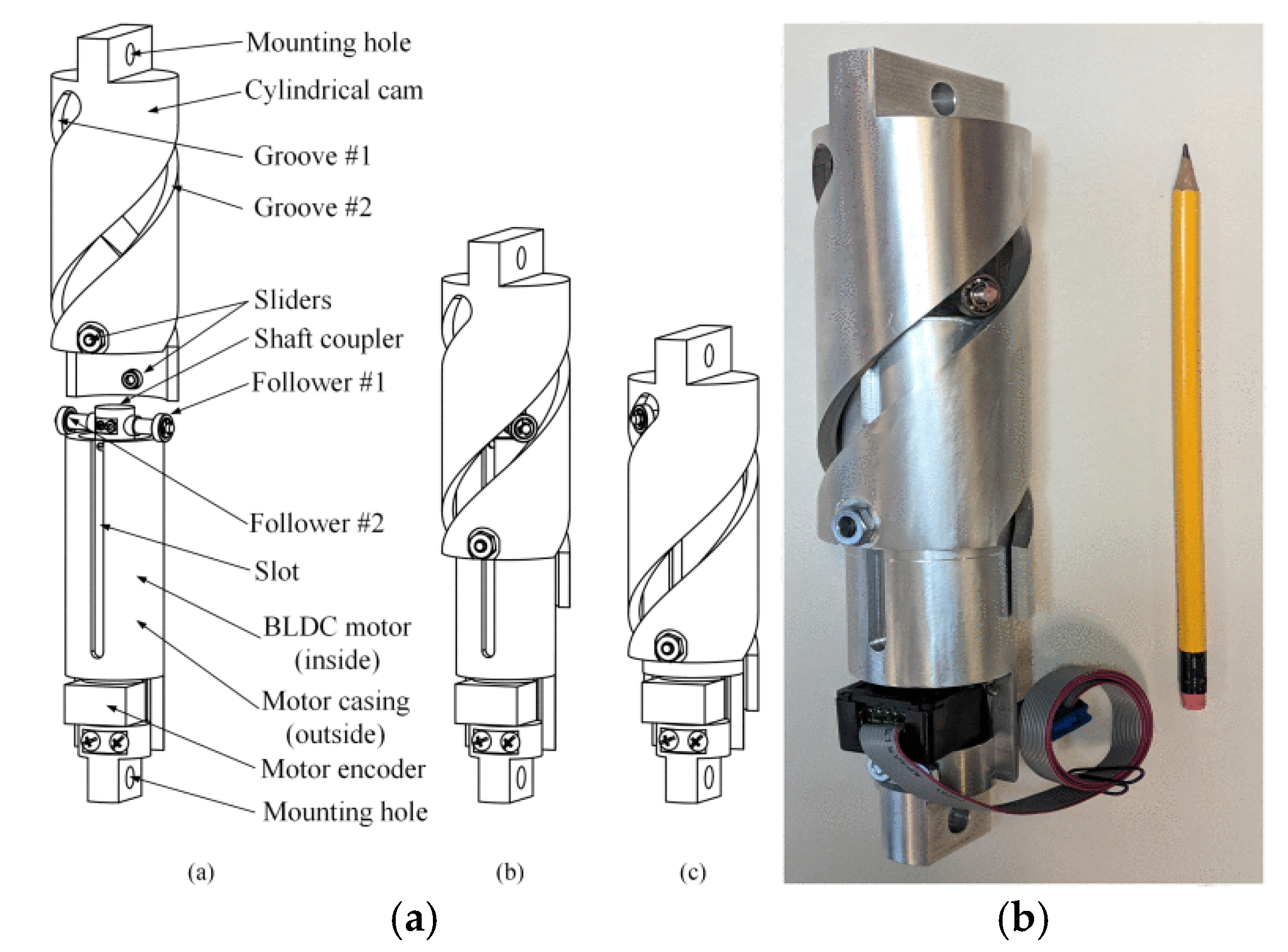

2.4.3. Cylindrical Cam

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cam roller [80,81] |

High efficiency and low energy consumption, low edge stress, low maintenance cost | Under high load, the lifespan may be shortened due to friction | Conveyor system, low energy consumption demand |

| Conjugate cam [82,83,84] | Smooth movement, minimal vibration, high-speed operation, compact structure | High cost, requiring precision machining and weight design | High-speed weaving machine, high-speed sorting, precision instruments |

| Cylindrical cam [85,86] | Small space occupation, long-distance movement, adjustable damping | Easy to wear and tear, high cost, poor stability | Equipment vibration suppression, long stroke, and compact requirements |

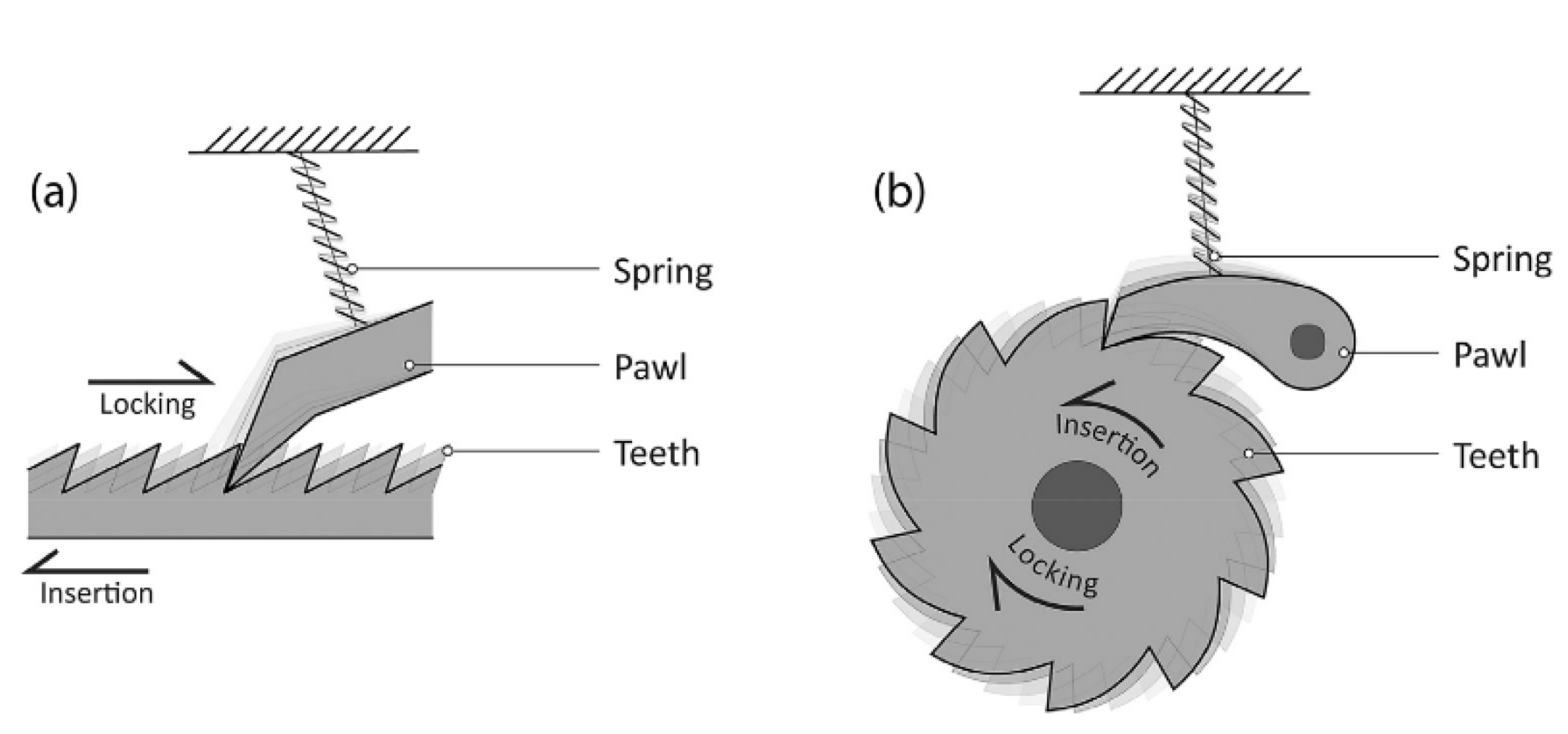

2.5. Ratchet and Pawl Mechanism

2.5.1. Flexible ratchet and pawl mechanism

| Types | Core Innovation | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bending loading | The cantilever beam replaces the spring hinge | Low cost, few parts | Low torque, prone to fatigue | Light machinery, low-cost equipment |

| Tension loading | Small-length flexible pivots enhance stiffness | High torque ratio | High material strength requirements | Electric tools, industrial transmission |

| Compressive loading | Rigid tooth and flexible segment separation design | Ultra-high torque ratio, low friction | Manufacturing complexity | Heavy machinery, automotive components |

| MEMS applications | Silicon-based integrated microstructure | Miniaturization, no wear and tear | Extremely small output, prone to failure | Micromechanical systems, sensors |

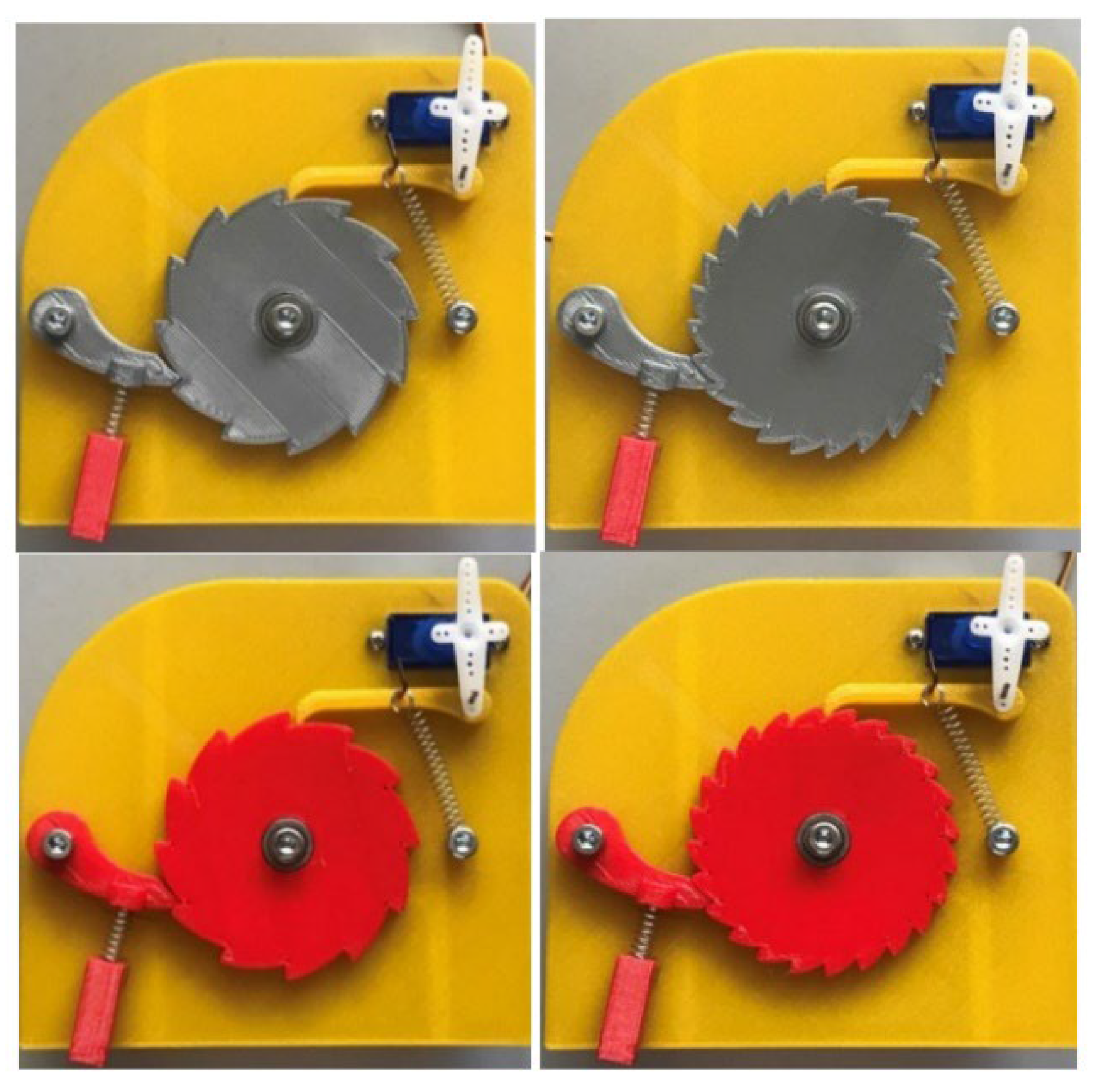

2.5.2. Ratchet and Pawl Mechanism for High-Speed Transmission

| Types | Core Innovation | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ratchet mechanism | Single pawl, fixed tooth pitch | Simple structure and low cost | High noise and poor high-speed performance | Low-speed and low-load scenarios |

| Modular ratchet mechanism | Multi-disc, multi-pawl, and elastic tooth design | High load capacity, low noise | Manufacturing is complex and costly | High-speed pulse transmission, heavy machinery |

| Micro ratchet mechanism | Miniaturization and elastic rod design | Miniaturization and low friction | Low load capacity and easy failure | Micromechanical system |

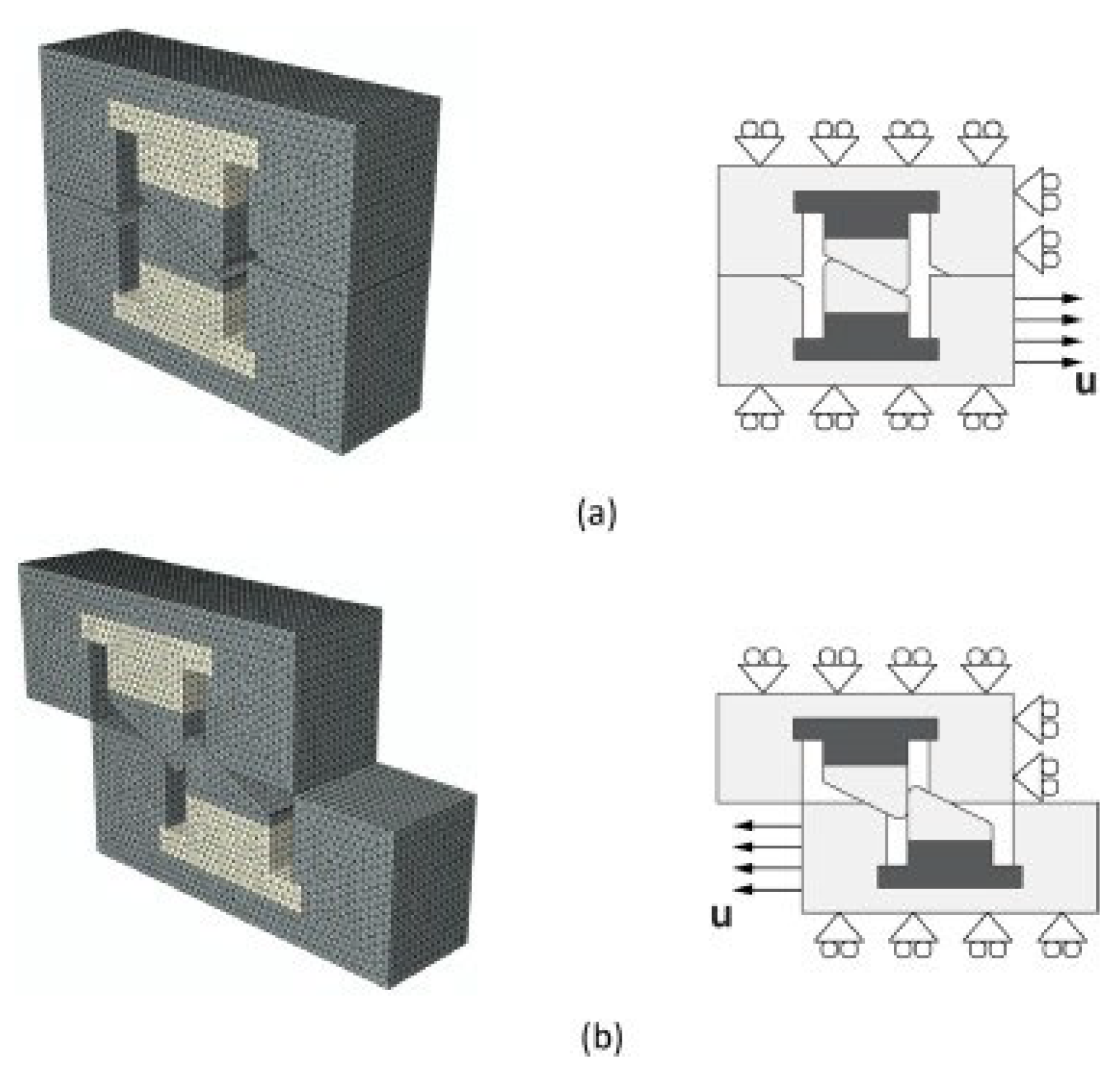

2.5.3. New Ratchet Mechanism for Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing Technology

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic deformation [87] | 3D printing multi-material integrated molding, no spring, compact space | Easy to fatigue, limited load capacity | Small load scenario |

| Gear optimization [92] | Adjustable number of teeth, low noise, lightweight, low development cost | PLA/ABS materials have low strength and poor durability | Engineering concept validation |

2.6. Linkage Mechanism

2.6.1. Four-Bar Linkage

2.6.2. Double spherical linkage mechanism

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crank-rocker mechanism [93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100] | Simple structure, high reliability, strong load capacity | High speed is prone to vibration and occupies a large space | Internal combustion engine, stamping press, biomimetic machinery |

| Hyperbolic handle mechanism [101,102] | Full rotation, uniform input, variable output | The speed of the driven crankshaft is unstable | Scenarios of bidirectional rotation or variable speed transmission |

| Elastic inside link [103] | High stiffness, wide range of motion, low driving force | Dependency on preloading design of snail shell | Precision instruments, flexible joints |

| Double spherical 6R linkage [104] | Deformable,[93–100 with multiple degrees of freedom | High design complexity and manufacturing cost | Expandable structure, biomimetic structure, robotic arm |

2.7. Typical Components of Rotating Mechanism—Bearings

2.7.1. Aerostatic Bearing

2.7.2. Magnetic Levitation Bearing

2.7.3. Hybrid ceramic ball bearing

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerostatic bearing [105,106] | High damping, low noise, low vibration, self-lubricating, controllable wear | Low stiffness, significantly reduced load capacity under high-impact momentum | Large flexible rotors, low friction high-speed rotating machinery |

| Magnetic levitation bearing [107] | Noncontact, no mechanical wear, compact space | Dependent on complex control systems, high-cost | Turbine, motor spindle, high-precision instrument |

| Hybrid ceramic ball bearing [108,109,110,111] | Long lifespan, high rotational speed, good stability, corrosion resistance, self-lubricating | High cost, limited overload performance | Low power consumption/low vibration/insulation and extreme scenarios |

3. Novel Rotating Motion Mechanism

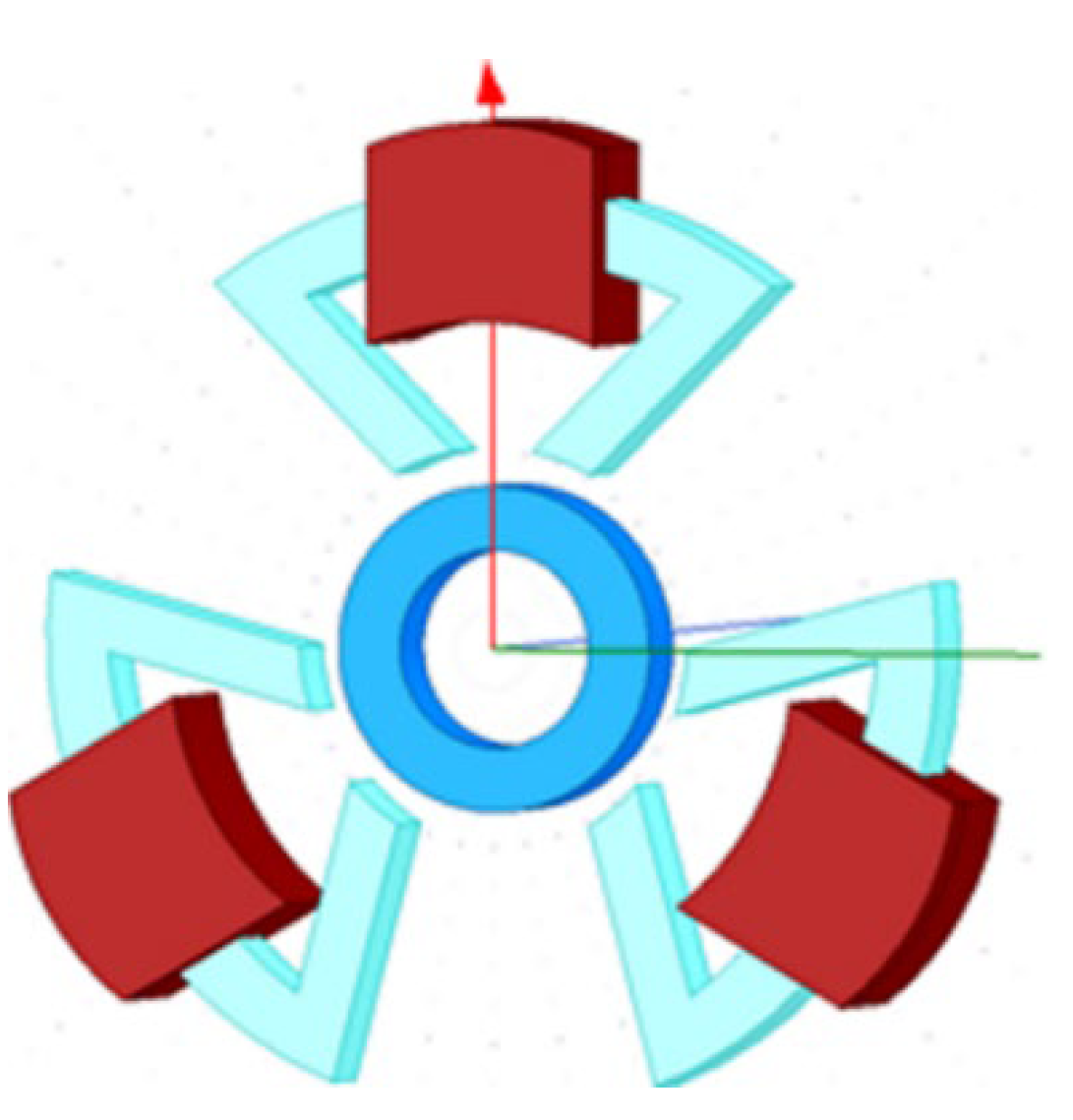

3.1. Intermittent Indexing Mechanism

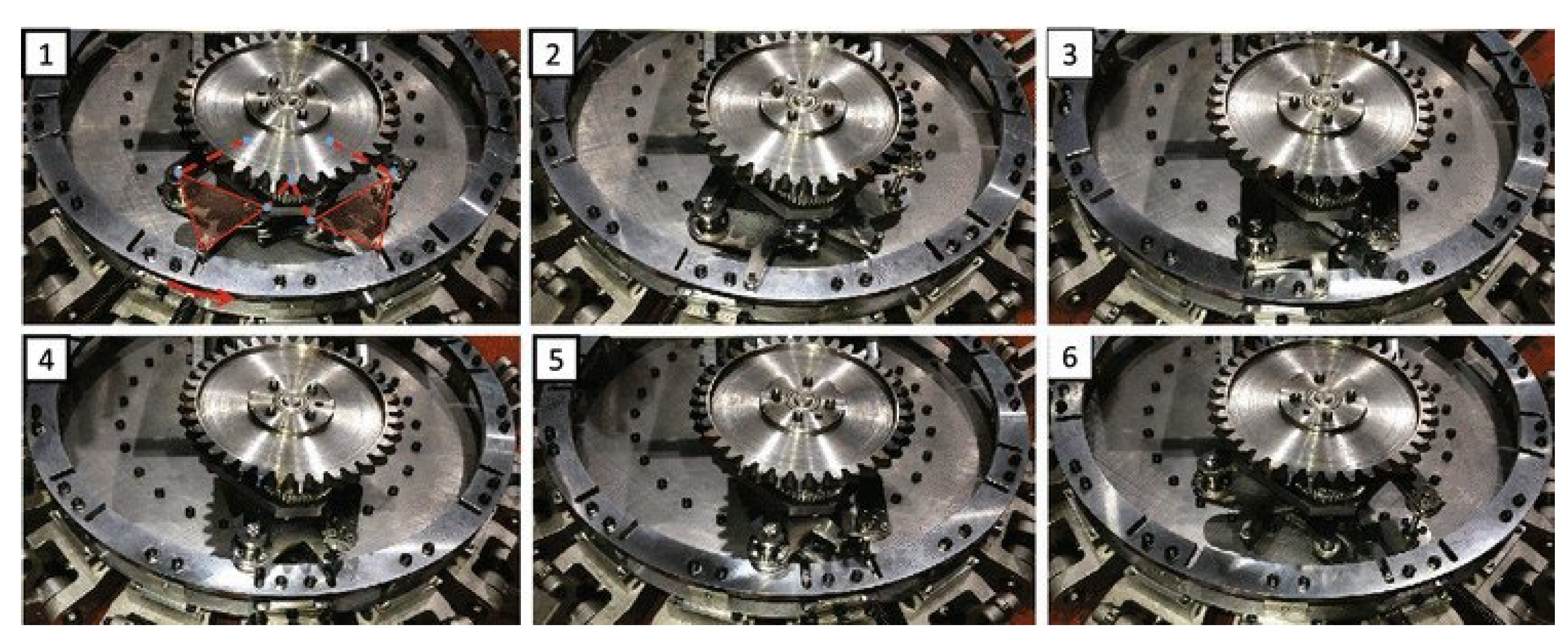

3.1.1. Coaxial Indexing Mechanism

3.1.2. New Geneva Mechanisms

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coaxial indexing mechanism [114] | Compact structure, high precision, and good stability | Complex structure, low load | Packaging, printing machinery, machine tool changing system |

| Circular groove wheel drive mechanism [115] | Simple structure, high reliability, and stable movement | High instantaneous impact upon contact, low speed | Low precision, light load, low-speed scenarios |

| Eccentric spiral intermittent mechanism [116] | Compact structure, adjustable intermittent motion | The eccentric wheel is prone to wear when in contact with the turntable | Intermittent drive for lightweight rotary table |

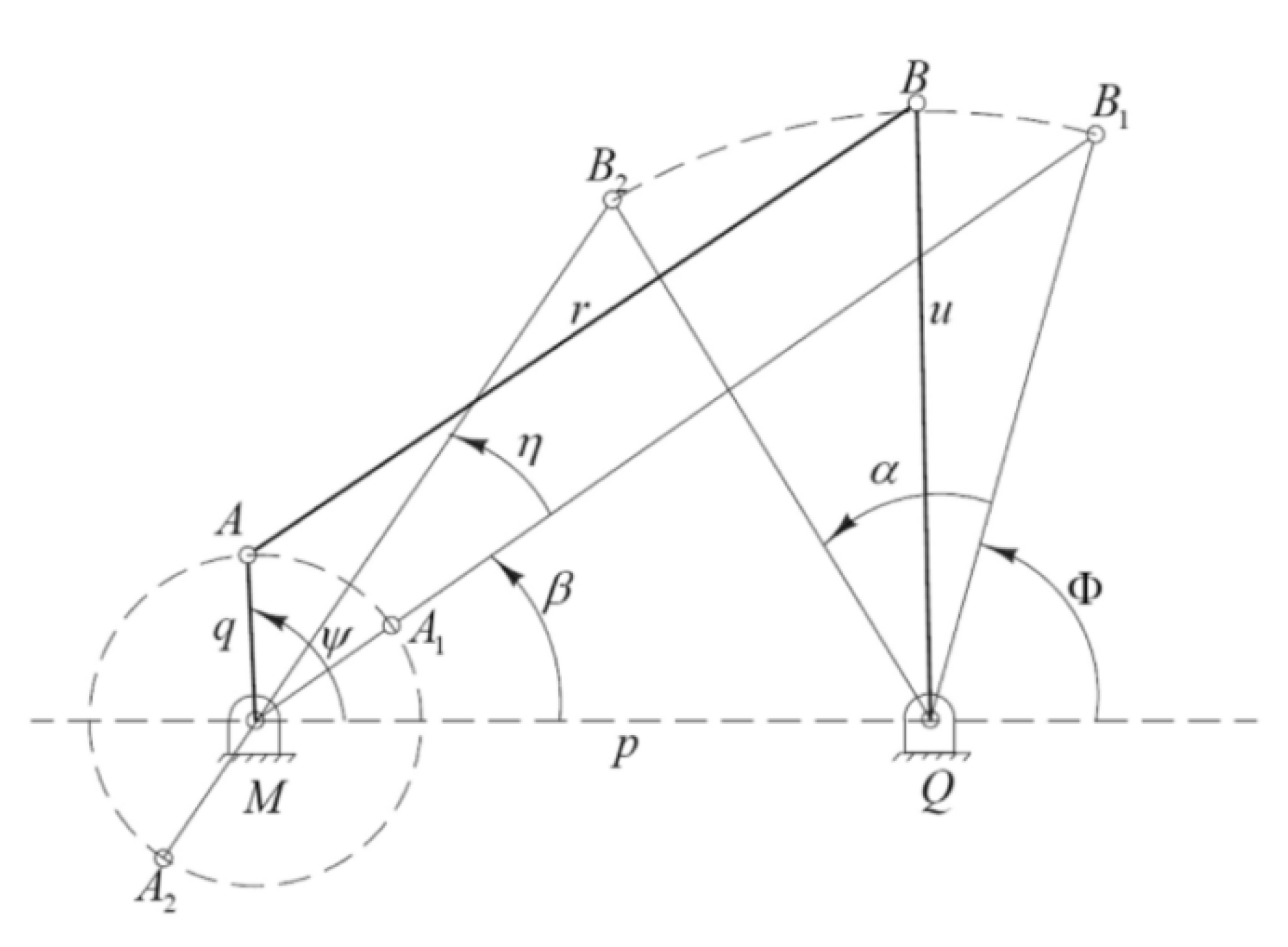

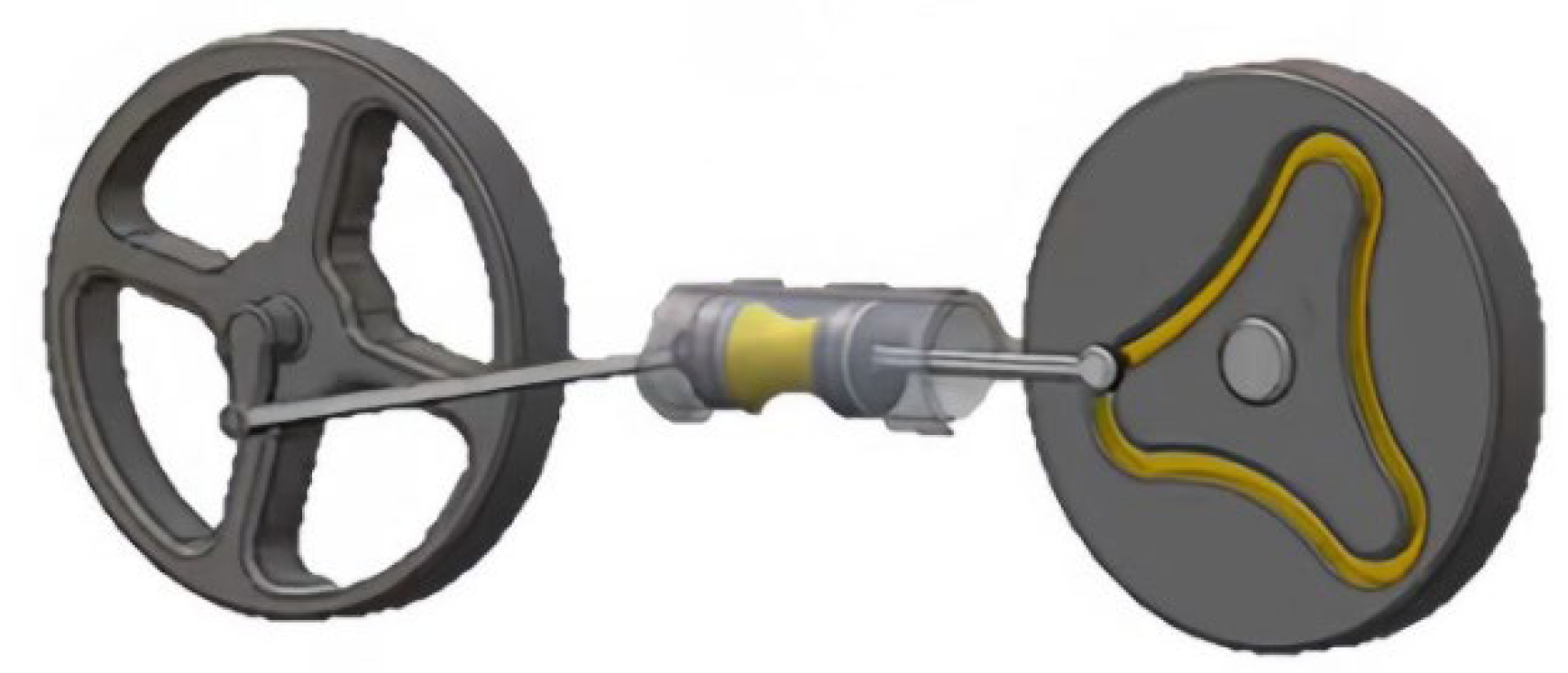

3.2. Linear Motion to a Rotational Motion Mechanism

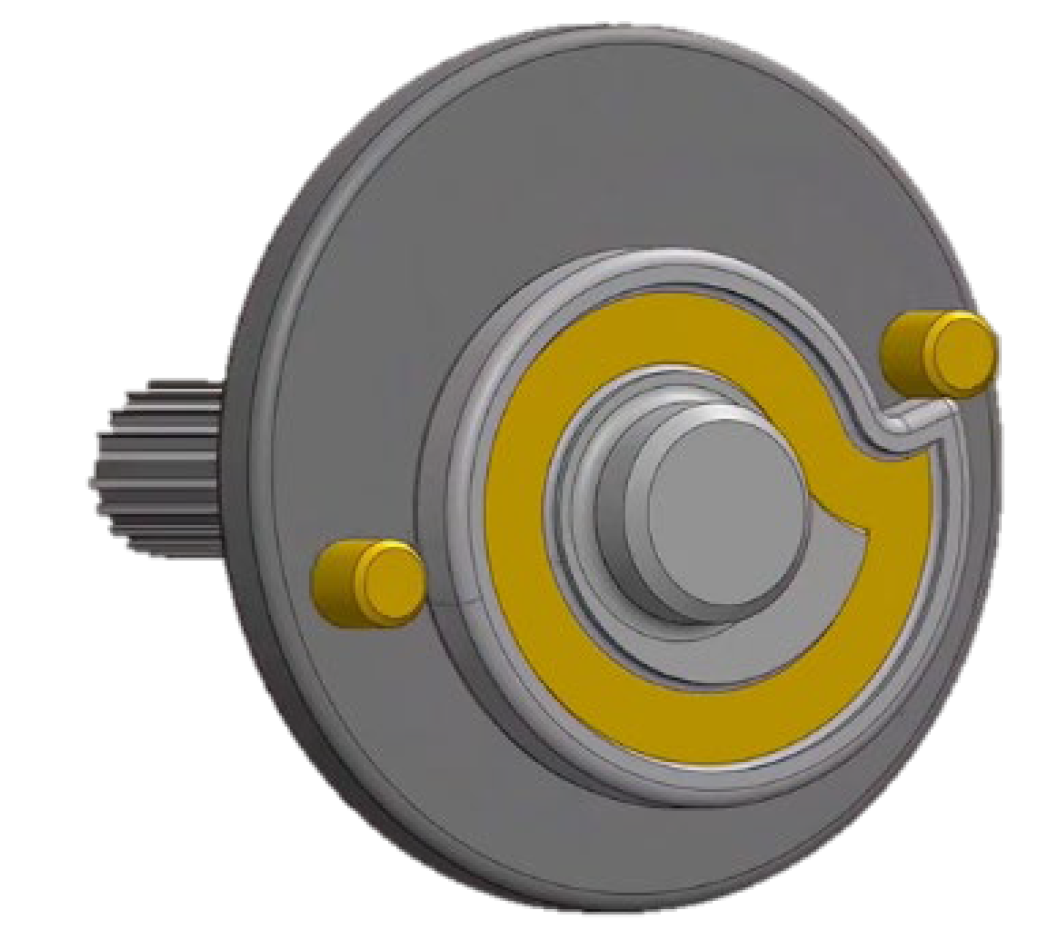

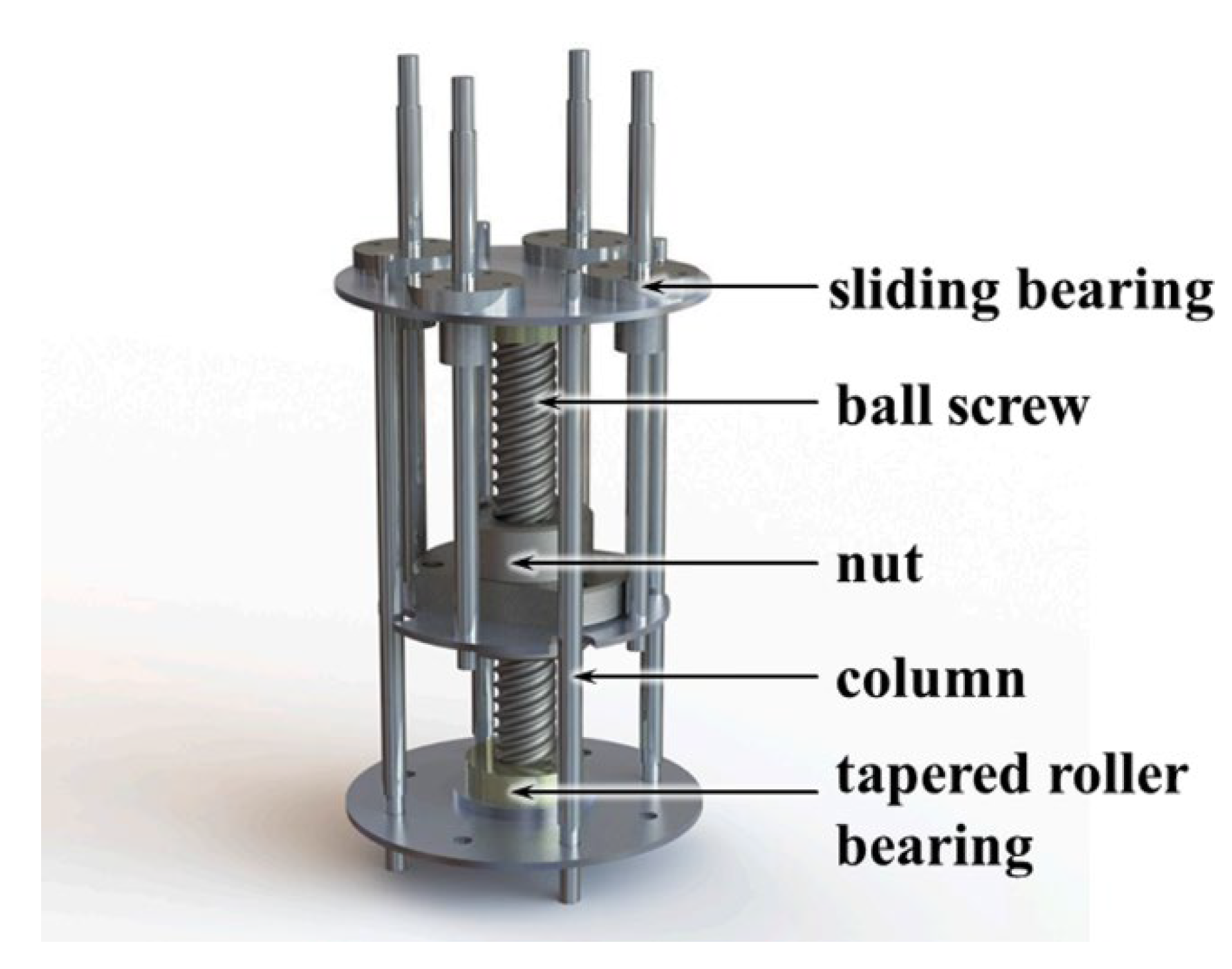

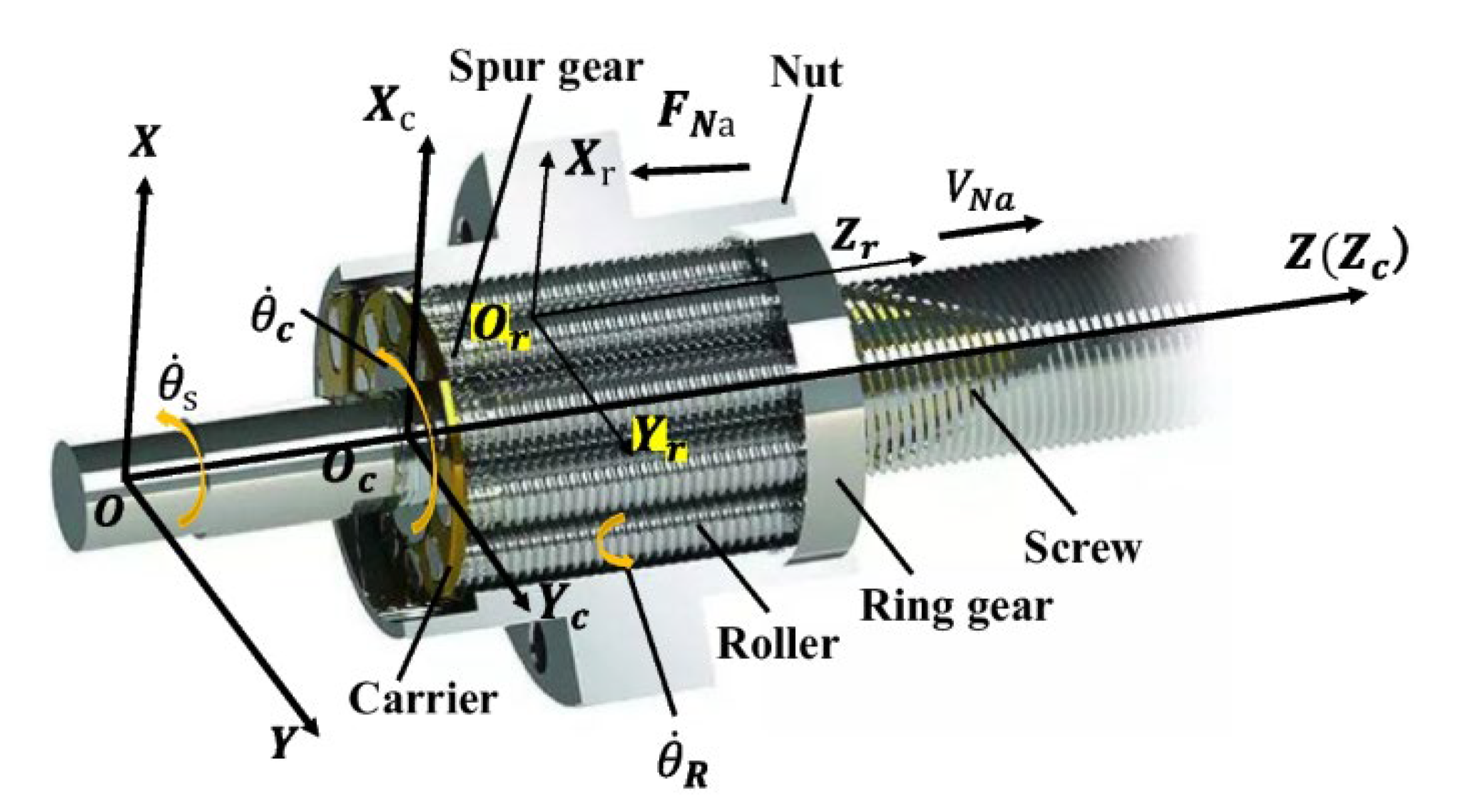

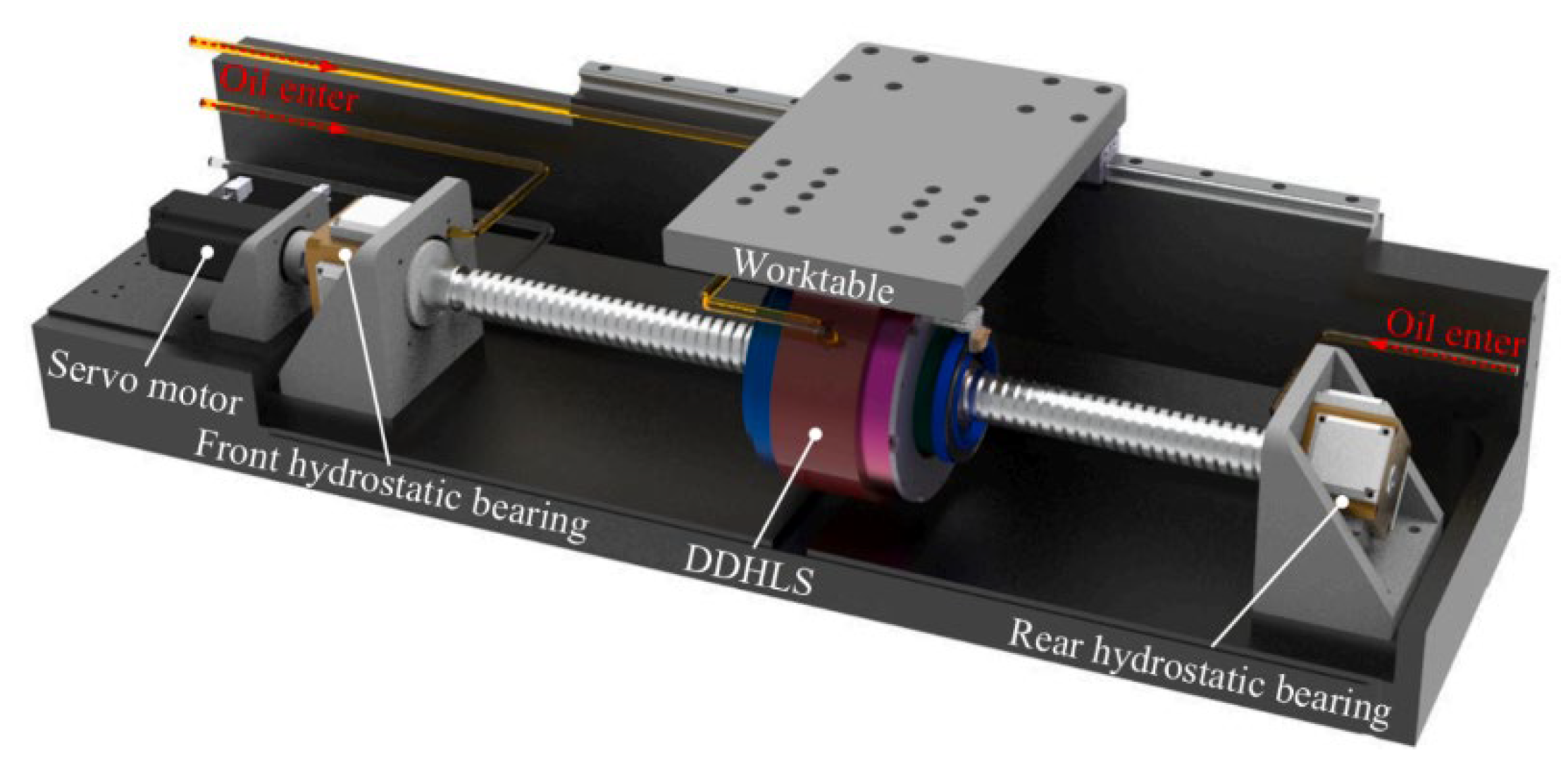

3.2.1. Ball Screw Mechanism

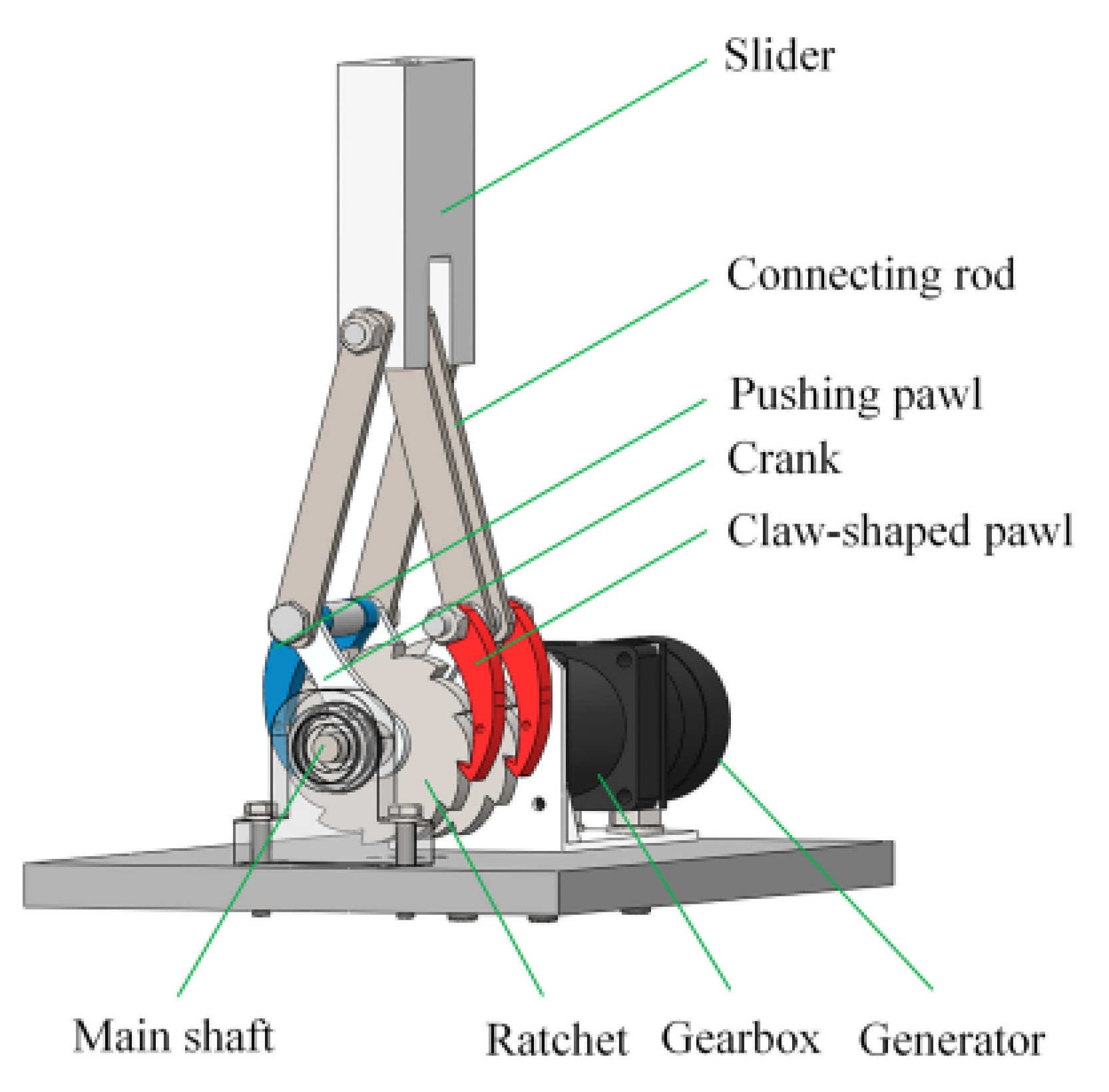

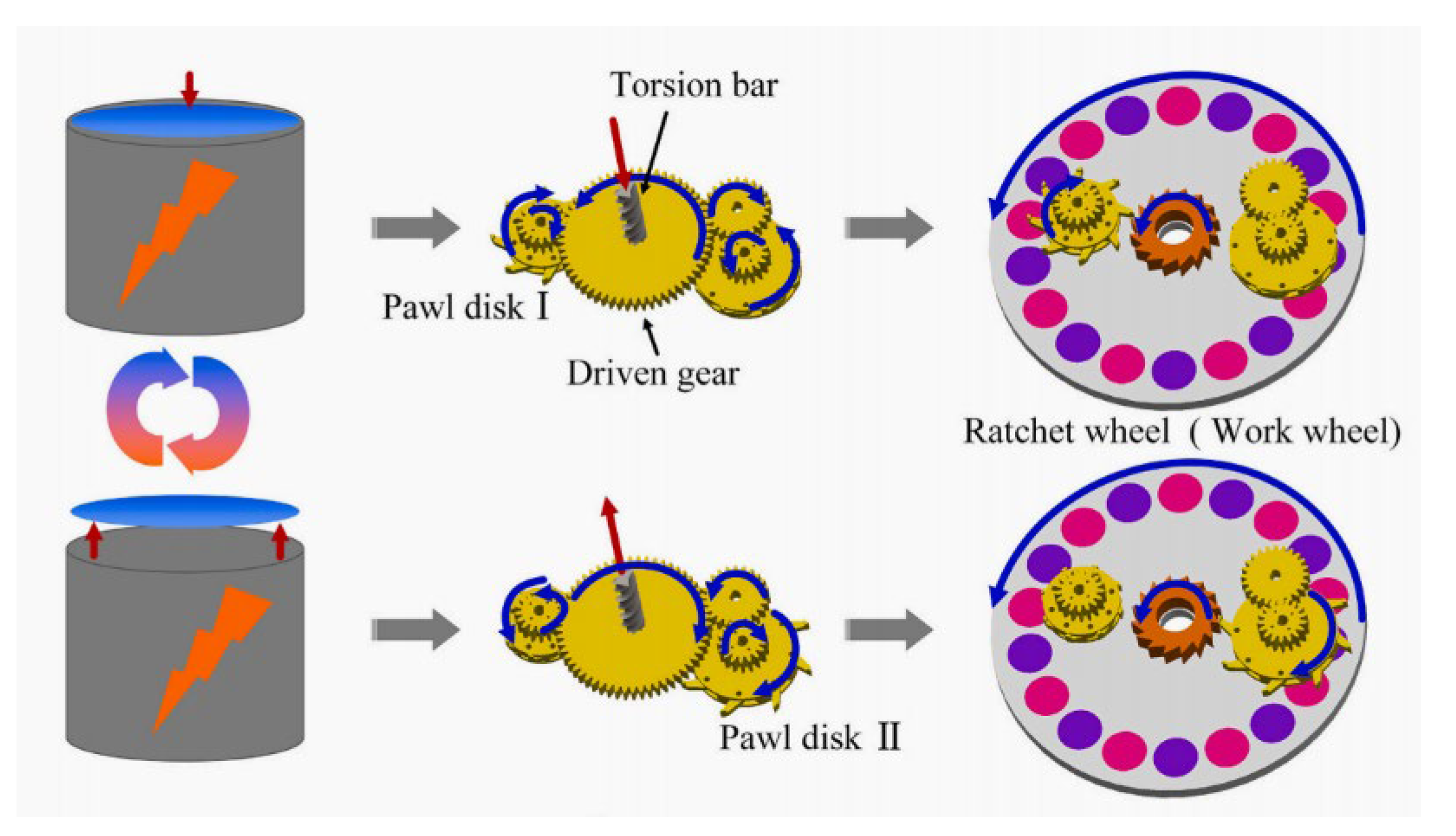

3.2.2. EHSA Based on Slider Crank Mechanism and Ratchet Pawl Mechanism

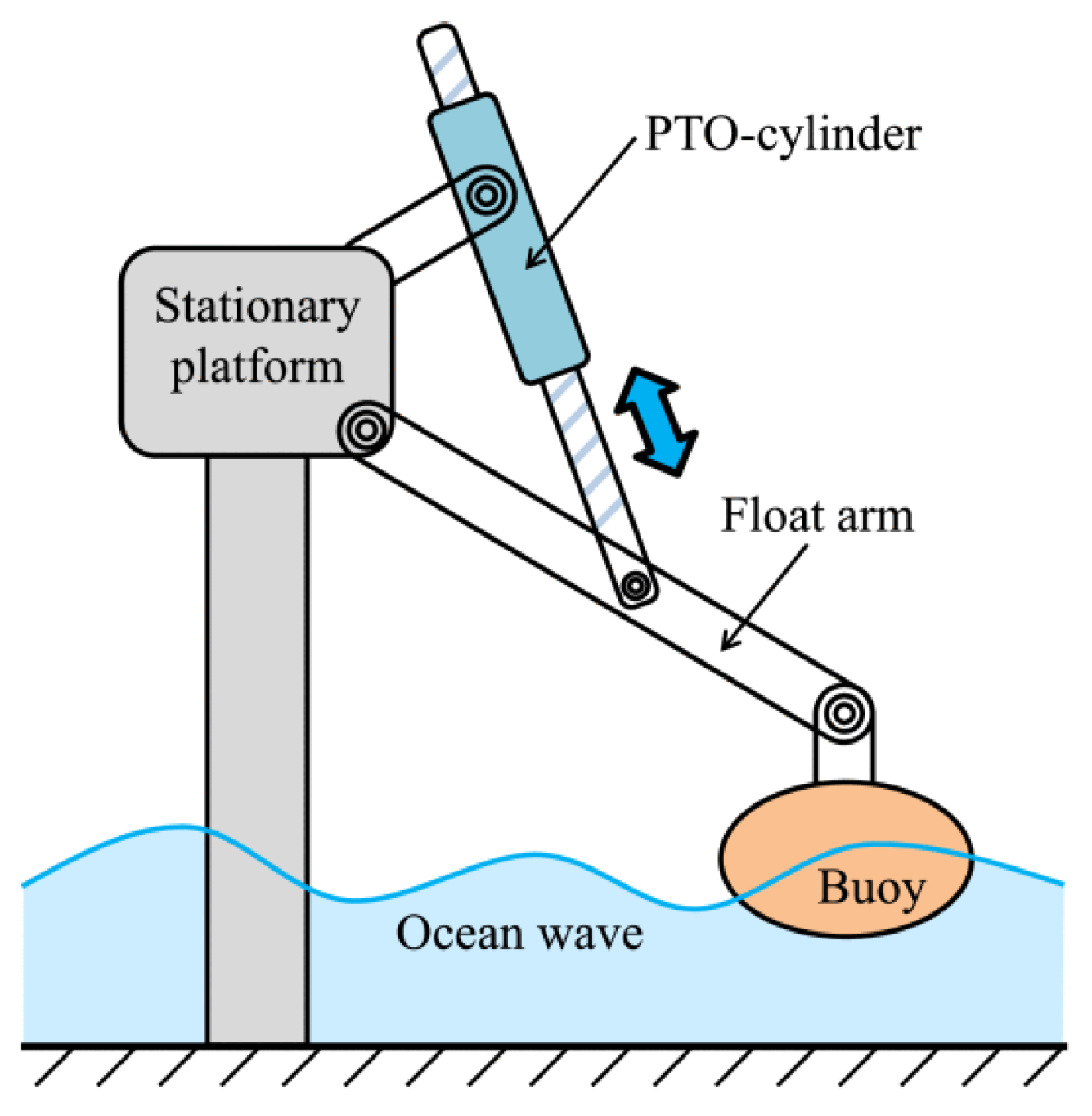

3.2.3. A New Type of Reverse Pole Magnetic Suspension System

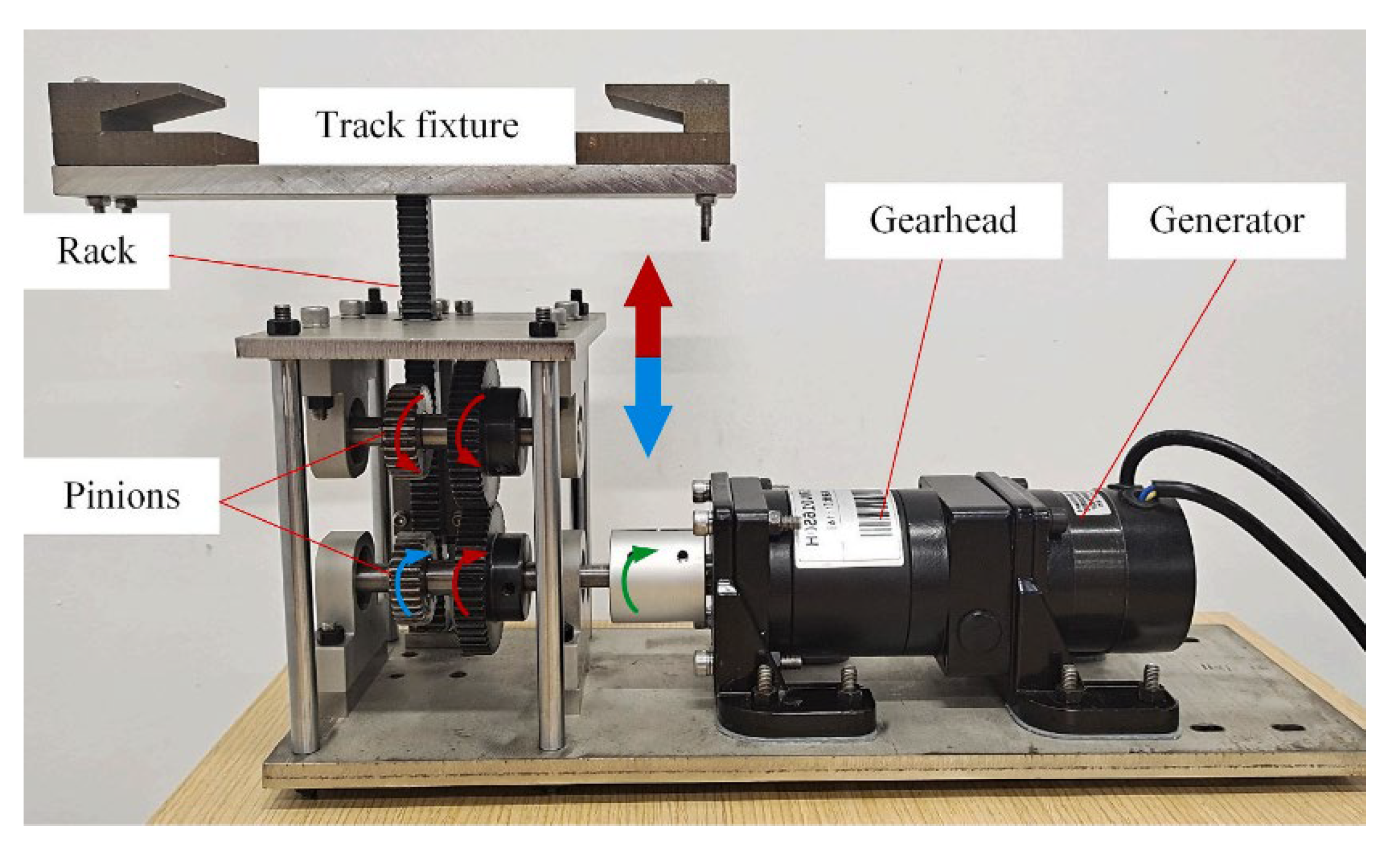

3.2.4. Series coupling rack mechanism

3.2.5. Screw Gear Ratchet Combination Mechanism

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planetary ball screw [119] | 3 times the load | High-cost | Stamping equipment |

| Static pressure screw [120] | High precision, up to sub-micron level | Low load High cost | Heavy-duty precision machinery |

| Slider crank ratchet mechanism [121] | The conversion efficiency of vibration recycling machinery can reach 67.75% | There is a material fatigue issue | Train shock absorption |

| Magnetic guide screw [122] | zero friction | Difficult to Maintain | Wave power Generation |

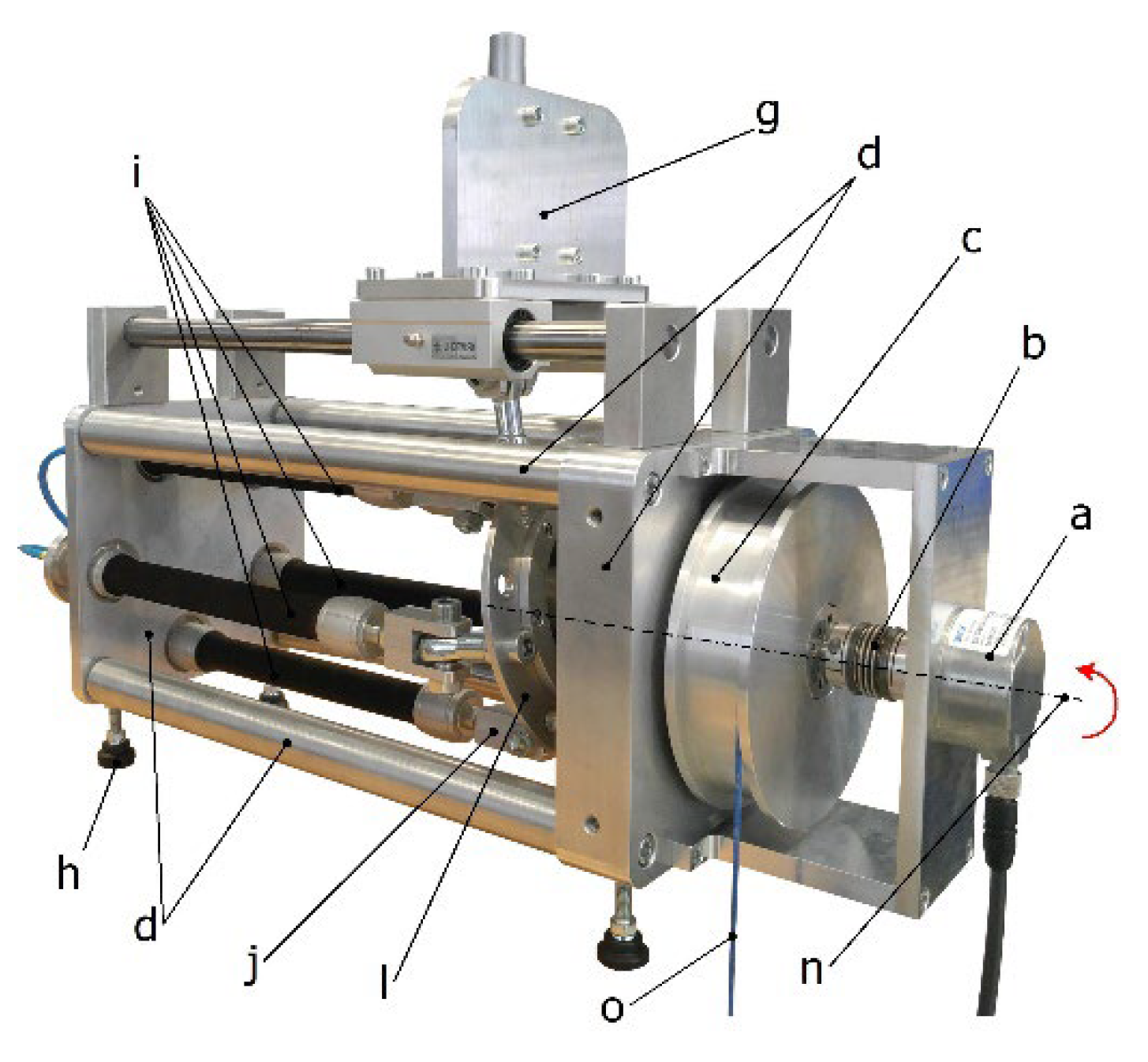

| Coupling rack mechanism [123] | Flywheel stabilization, the mechanical conversion efficiency can reach 64.31% | Difficulty in maintenance and limited power | Track vibration |

| Screw gear ratchet combination mechanism [124] | High-frequency conversion, high energy harvesting efficiency | Easy to wear and tear | Energy recovery in densely populated areas |

3.3. Joint Rotation Mechanism

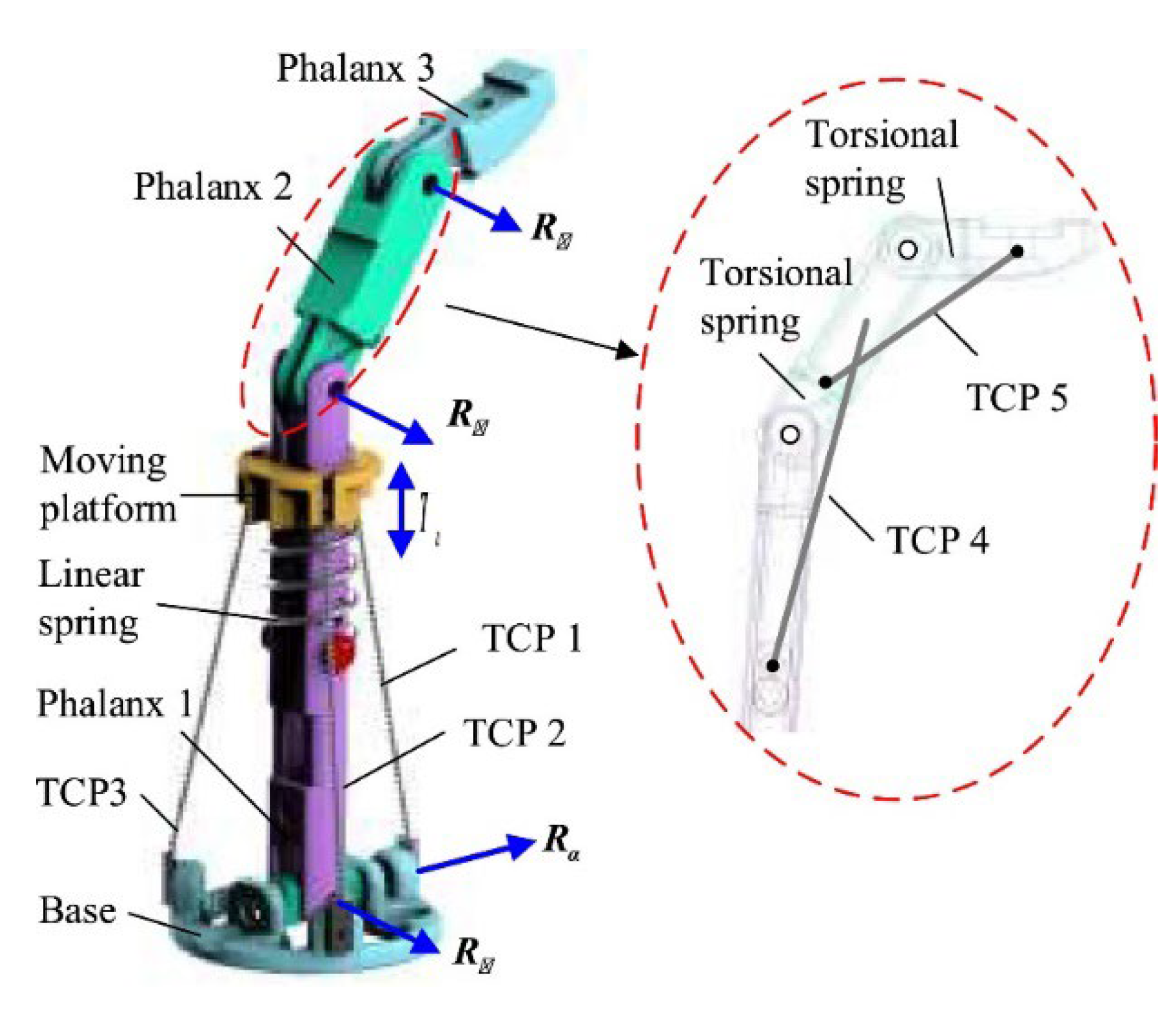

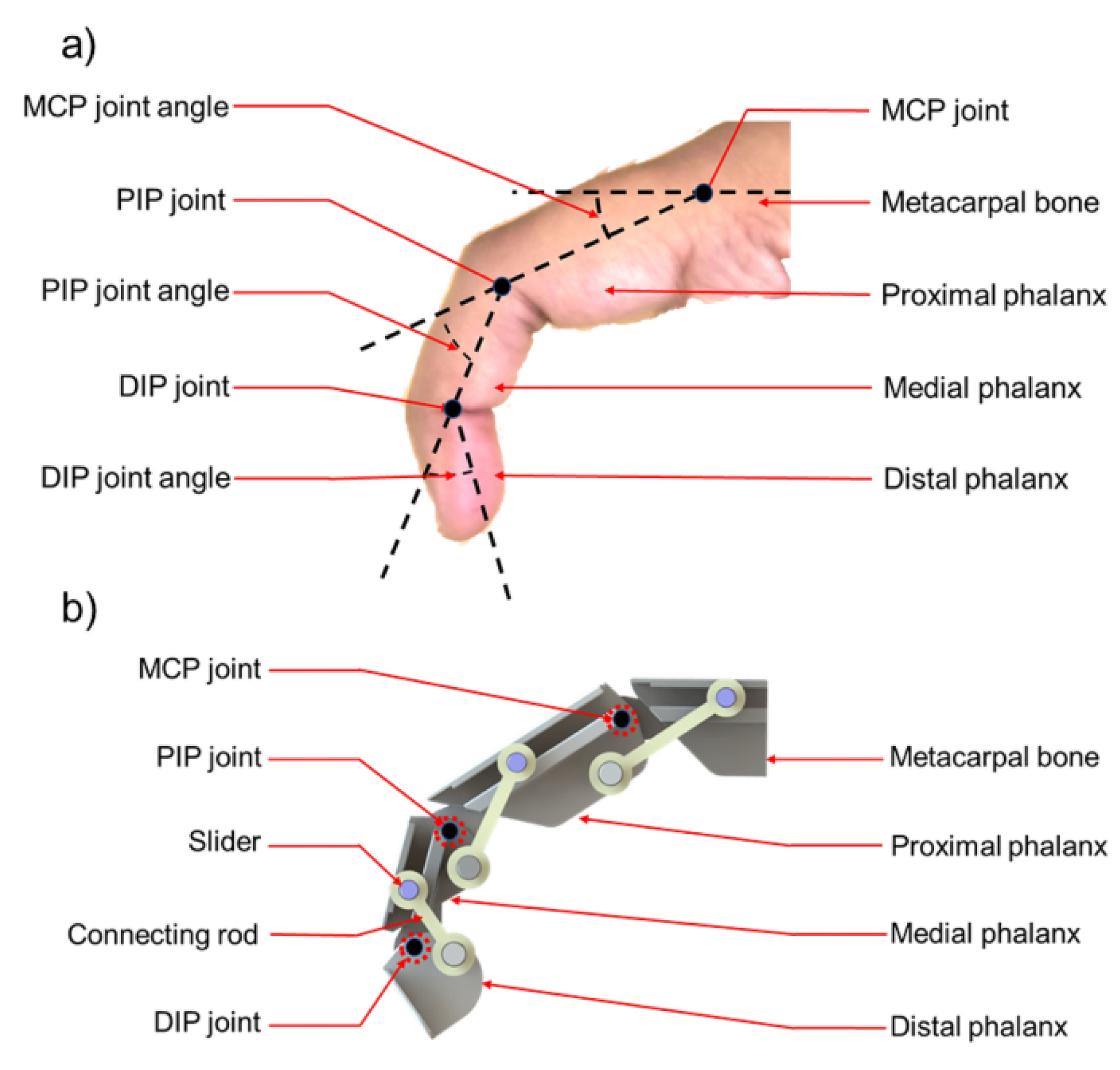

3.3.1. Twisted Polymer Driven Series-Parallel Hybrid Finger Mechanism

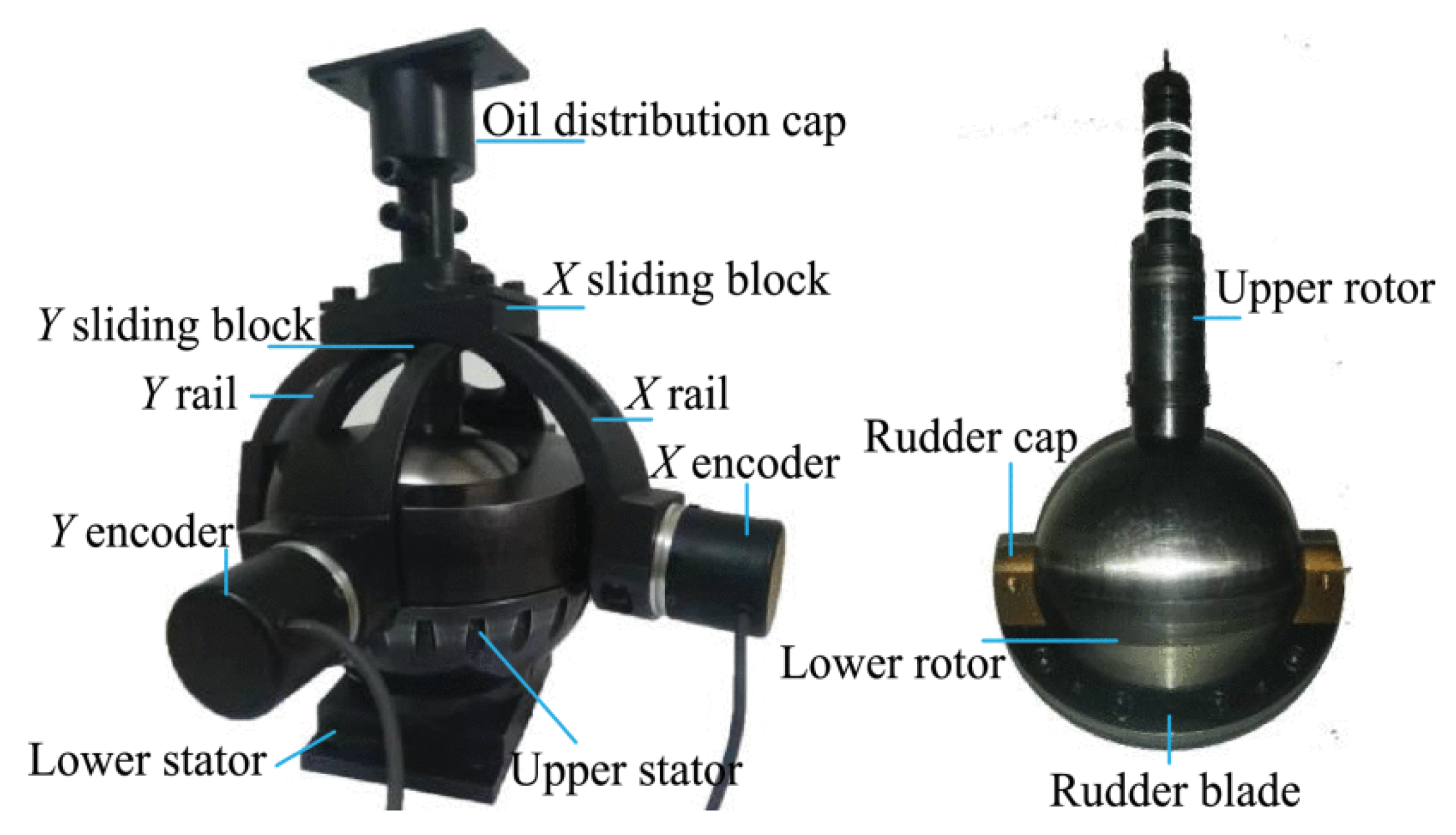

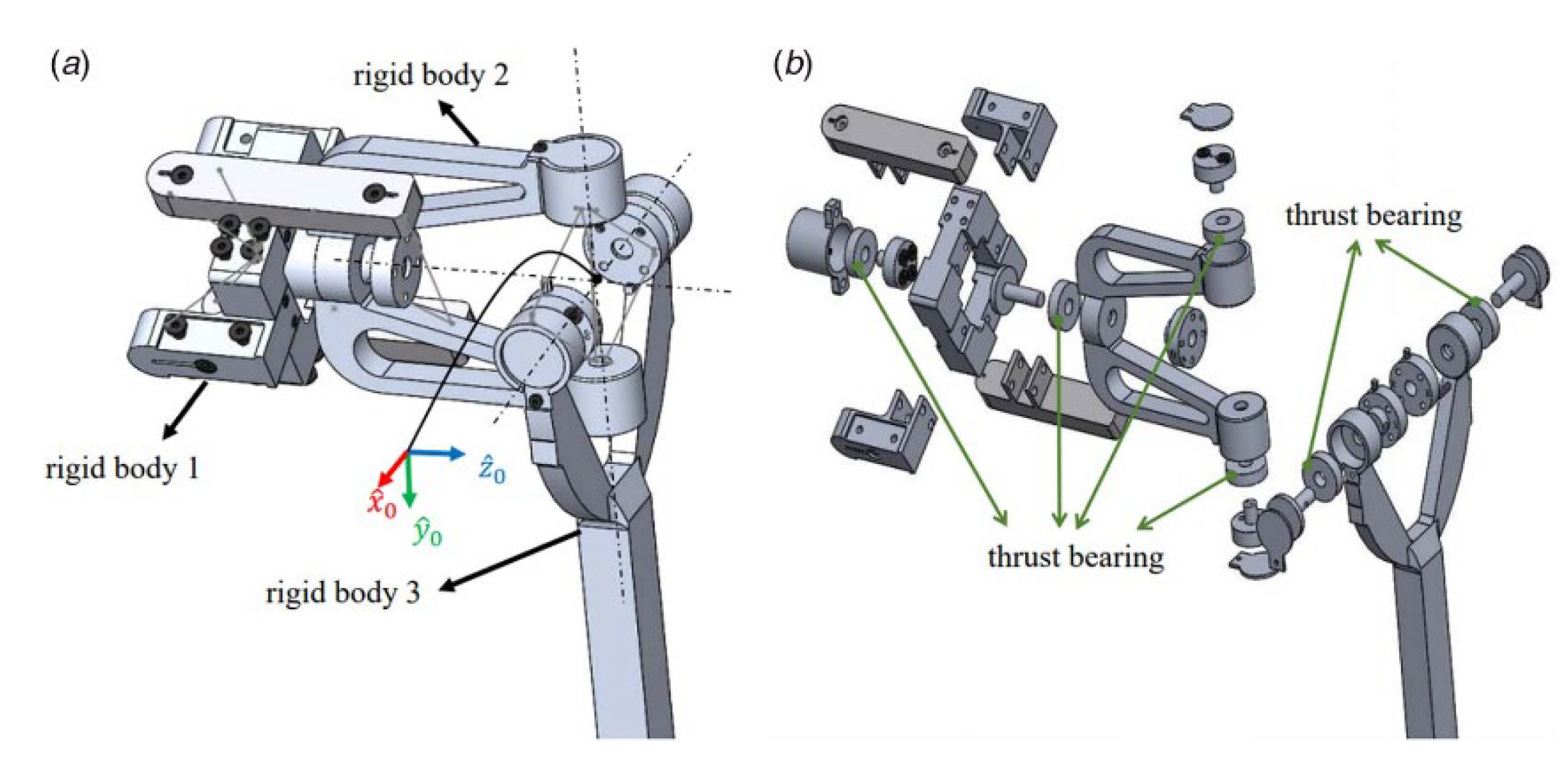

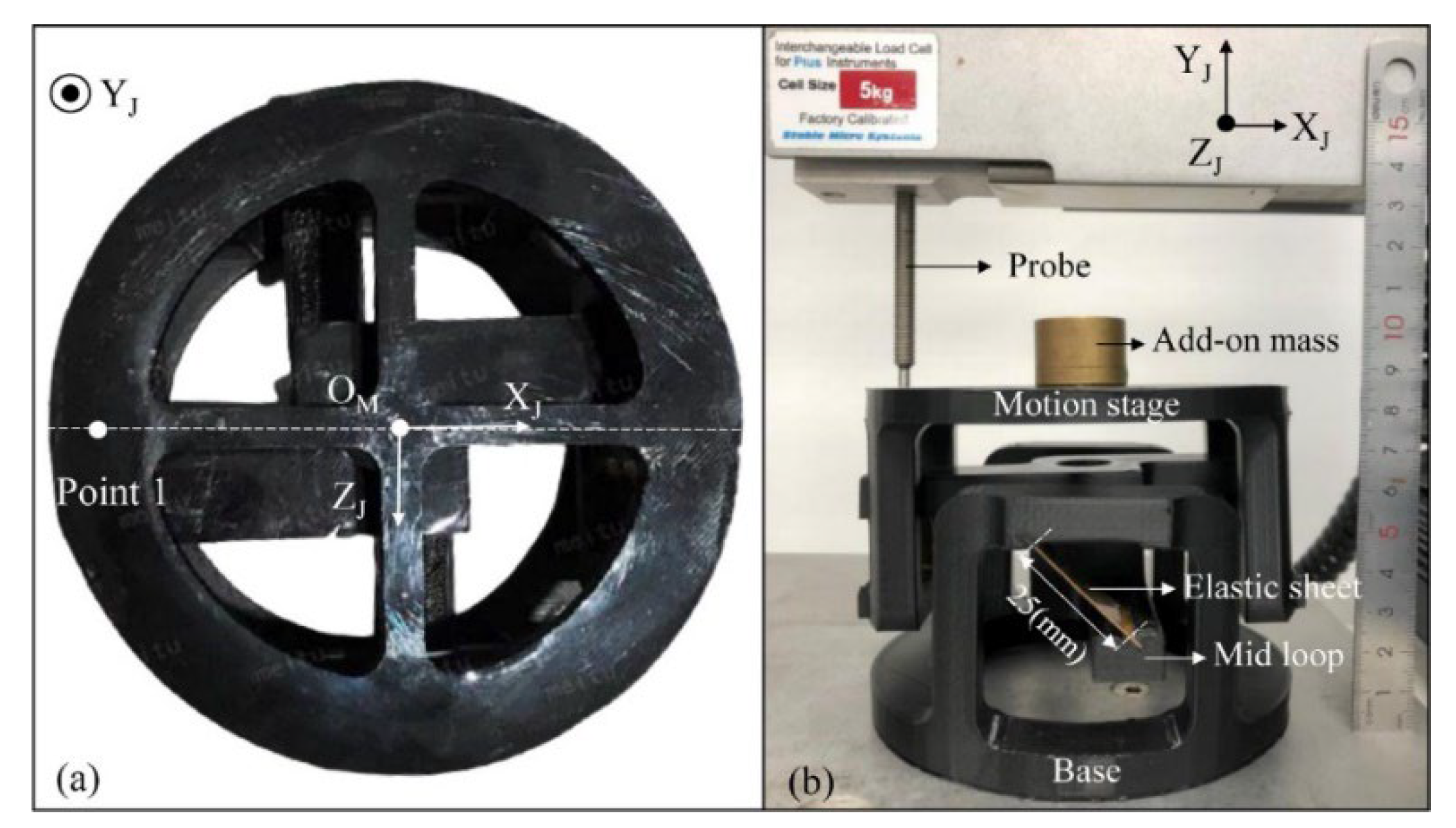

3.3.2. New Type of 2-DOF Ball Joint Hydraulic Spherical Motion Mechanism

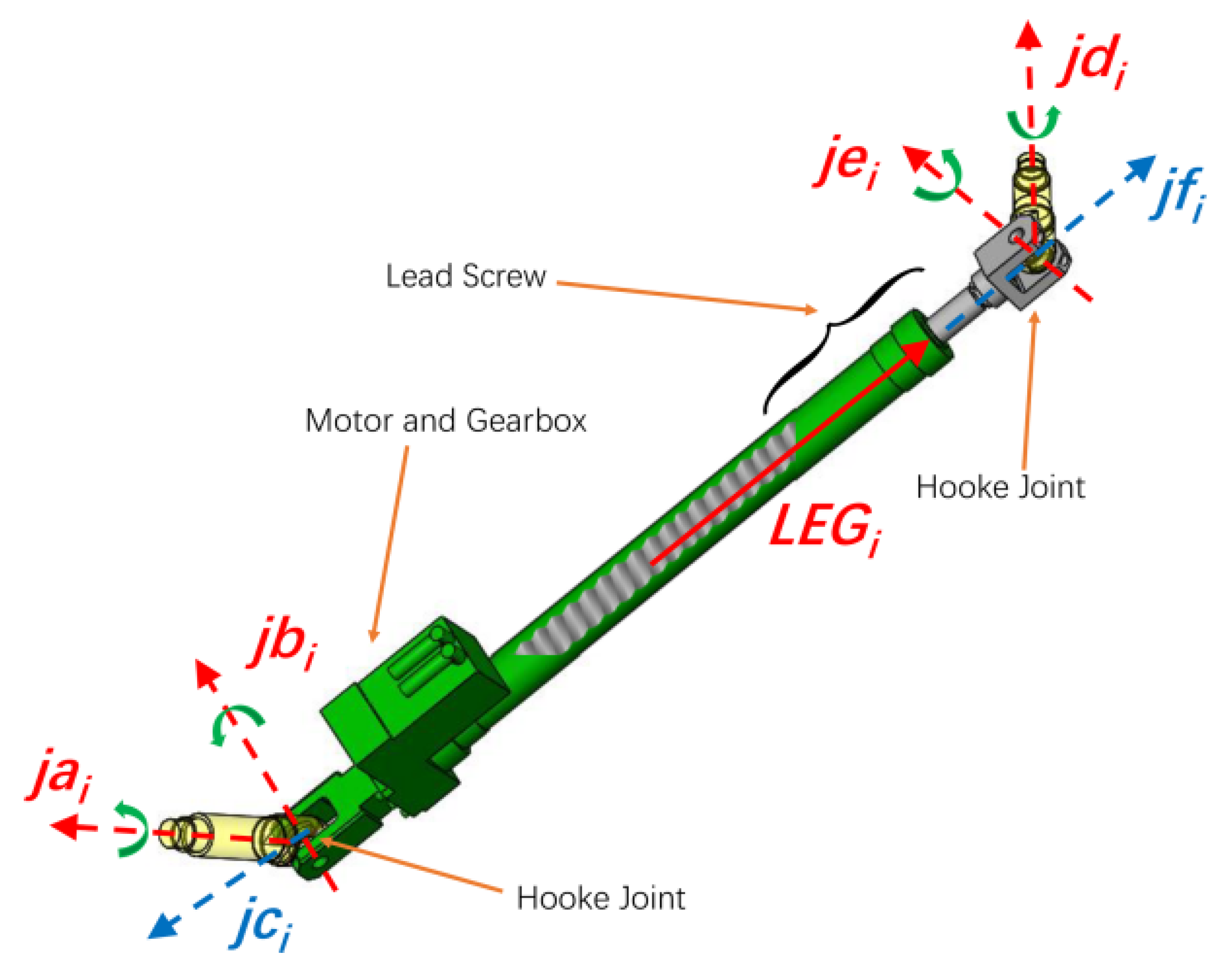

3.3.3. Hook Joint in Stewart Platform

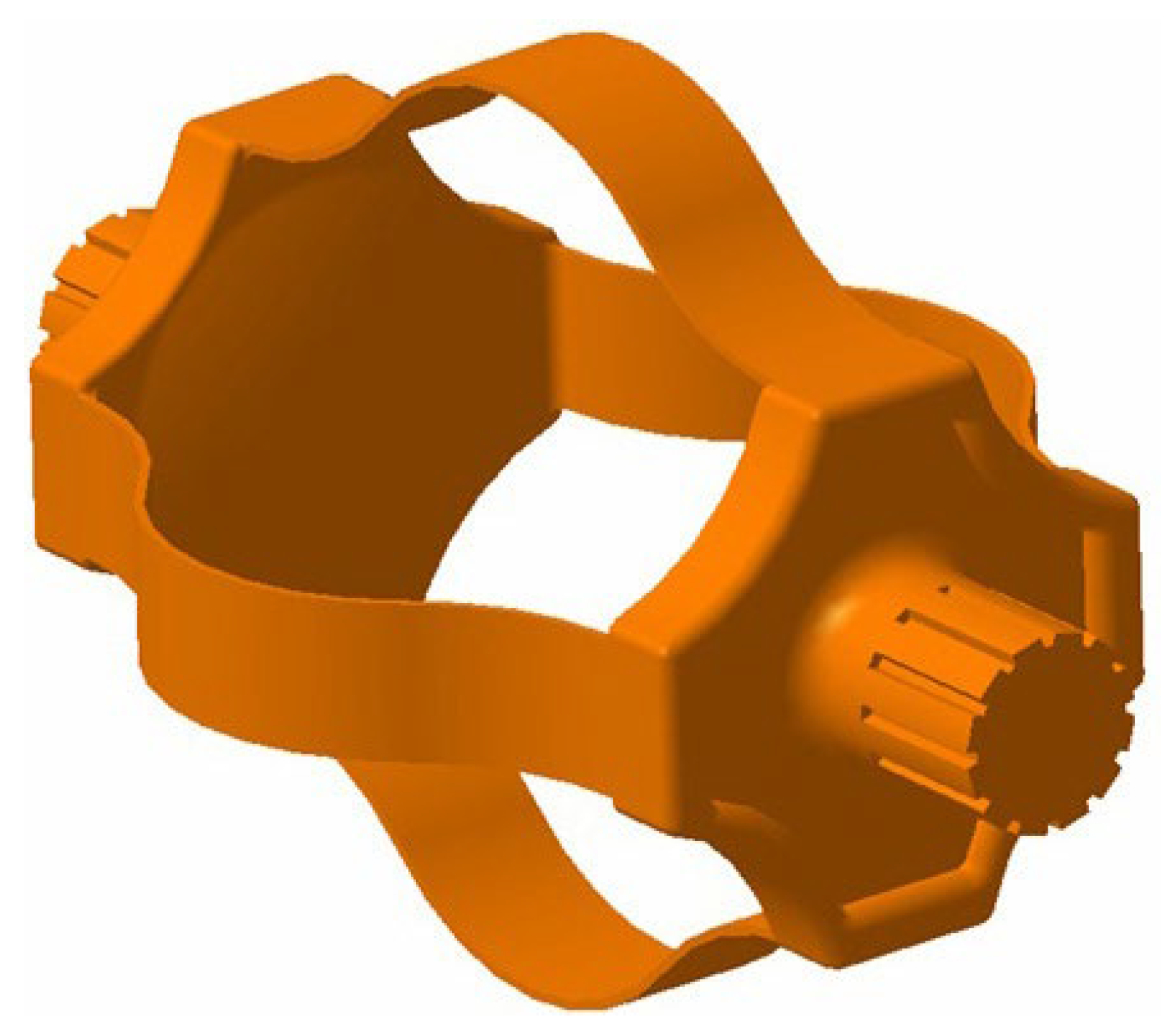

3.3.4. Three Degrees of Freedom Tensioned Integral Structure

3.3.5. New Offset Slider Crank Crank and Connecting Rod Combination Hybrid Mechanism

3.3.6. A New RCM Mechanism

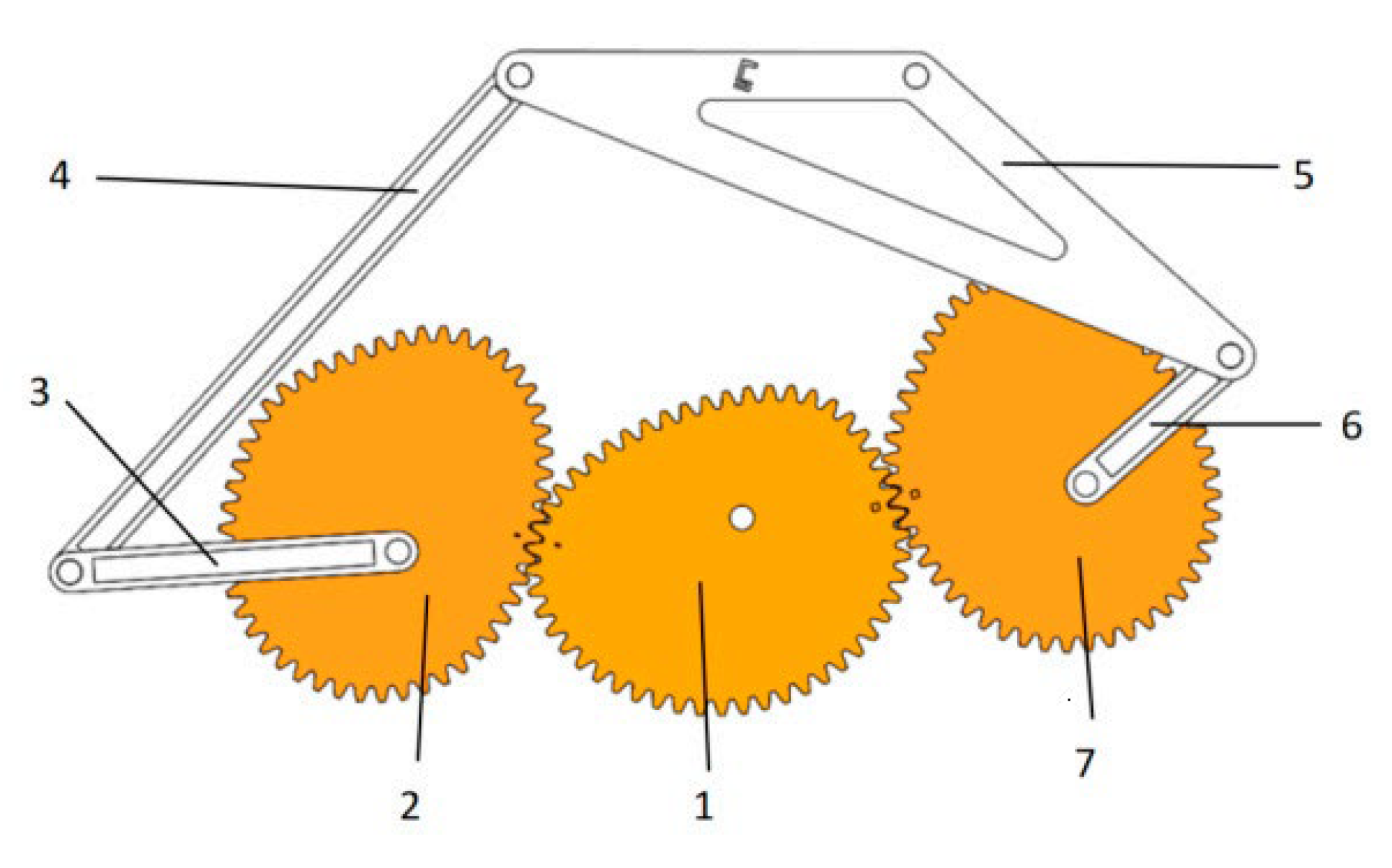

3.3.7. Non Circular Gear Five-Bar Mechanism

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Series parallel hybrid finger mechanism [125] | High response speed, balanced stiffness, and flexibility, adaptable to various grasping modes | Complex structure, limited material properties | Robot hands that require quick response and flexible grasping |

| Hydraulic spherical motion mechanism [126] | Compact structure, high stiffness, 2-degree-of-freedom spherical motion | High energy consumption | In robot joint and spherical motion scenes |

| Stewart Platform Hook Joint [127] | Adapt to complex movements, have a simple structure, and are easy to integrate | Limited carrying capacity, long-term wear and tear | High-precision positioning platforms |

| Three degrees of freedom tensioned integral structure [128] | Combining rigidity and flexibility, with strong impact resistance | Control complexity, Cable tension balance requires precise adjustment | Lightweight robotic arms |

| Offset slider crank connecting rod mechanism [129] | Multi-joint single drive synchronous drive, lightweight structure | Low load capacity, Dependent on linear actuators, limited travel | Functional pseudo bionic robot fingers |

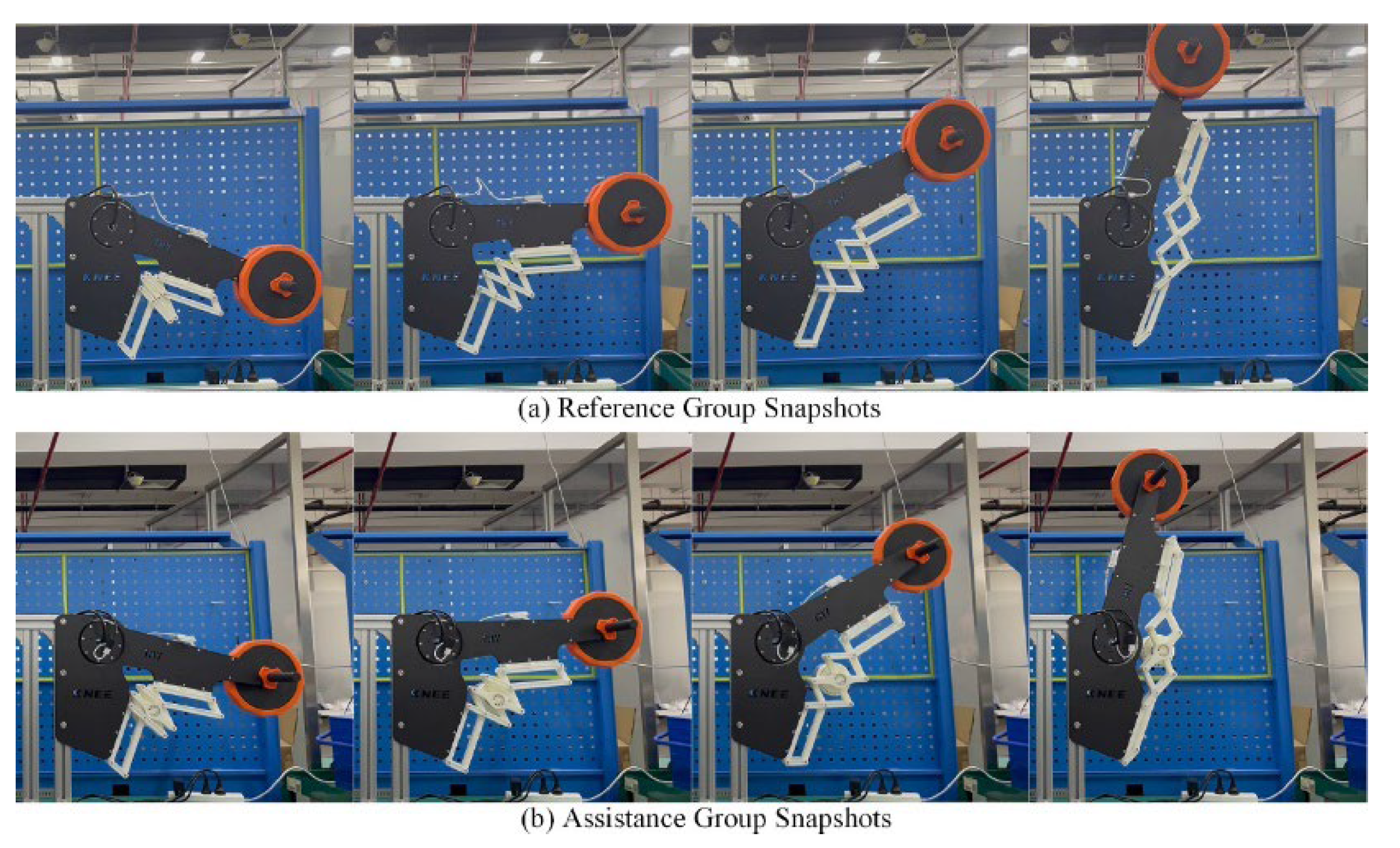

| New RCM mechanism [130] | Lightweight, shock-absorbing, and highly coordinated in motion | Restricted range of motion | Knee exoskeleton, human-machine motion axis alignment scene |

| Non-circular gear five-bar Mechanism [131] |

Simplify the structure; High degree of freedom constraint, strong motion controllability | Complex processing, and gear meshing accuracy affect transmission efficiency | Biomimetic joint with variable transmission ratio characteristics |

3.4. Multi Link Rotating Mechanism

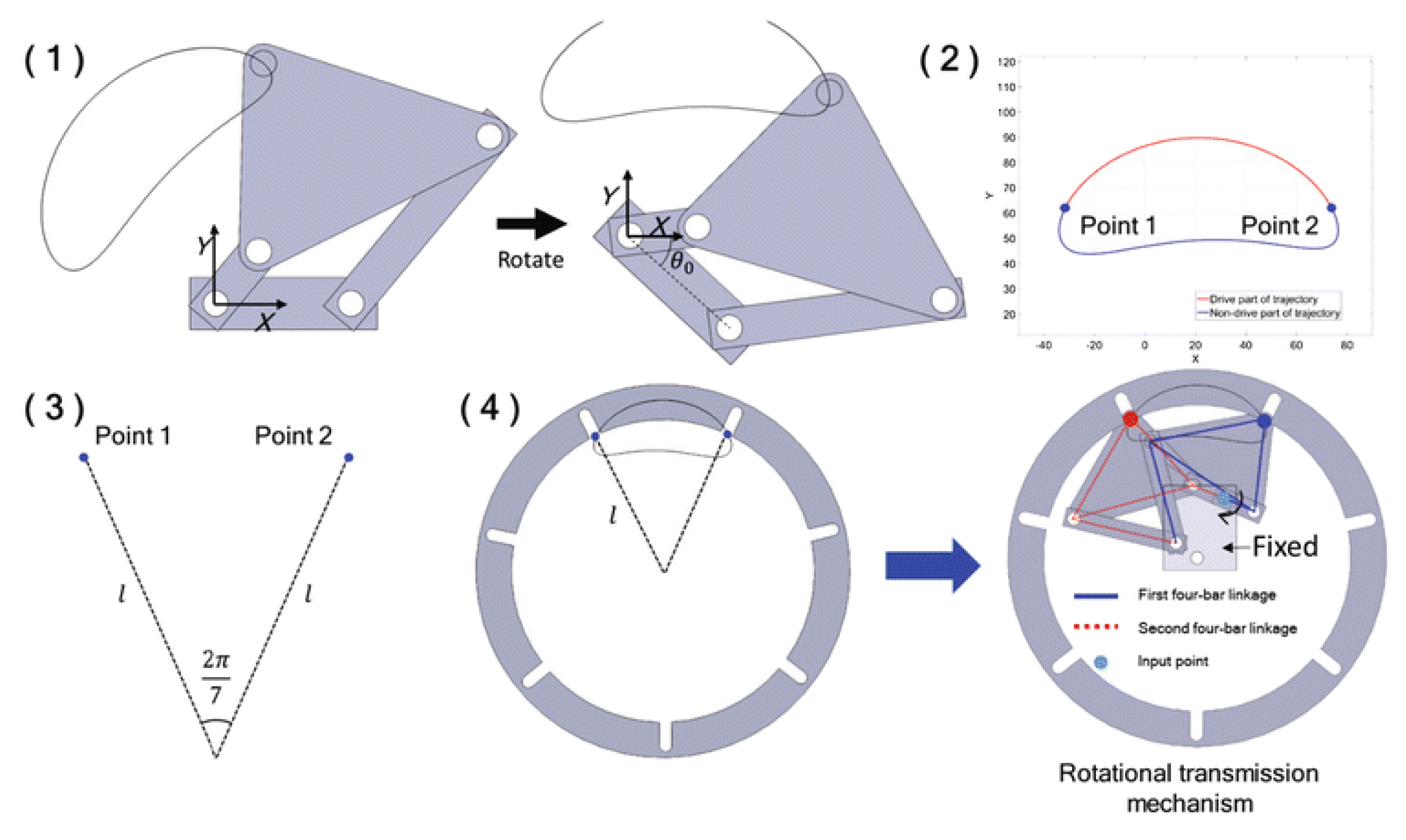

3.4.1. Double Four-Bar Rotary Transmission Mechanism

3.4.2. Cam Five-Link Mechanism

3.4.3. Multi Link Crank Slider Rotating Mechanism

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double four-bar rotary transmission mechanism [132] | The structure is simple, the space is compact, the cost is low, and the output disk rotates continuously | Limited motion accuracy, speed, and rotation angle | Automatic tool-changing systems for machining centers and tapping machines |

| Cam five link mechanism [133] | High reliability, compact structure, high precision, and stability | The design is complex, the cost is high, and the ability to dynamically adjust is limited | High-dynamic industrial scenarios such as packaging machinery and medical production lines |

| Multi-link crank slider rotating mechanism [134] | High carrying capacity, high precision, and flexibility | Complex structure, low speed, and accumulated errors | Gyroscope, low-speed high-precision, redundant degree of freedom scene |

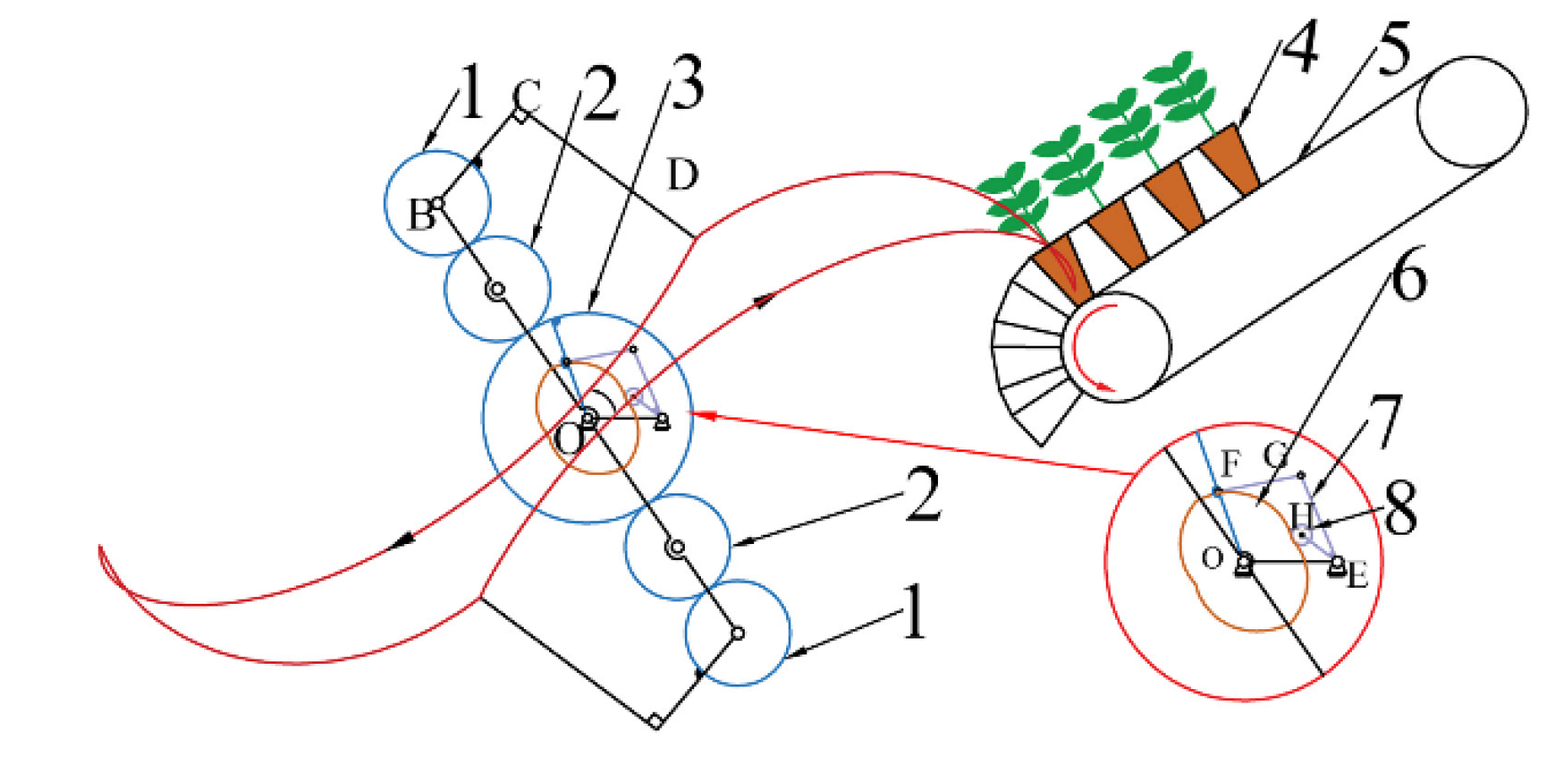

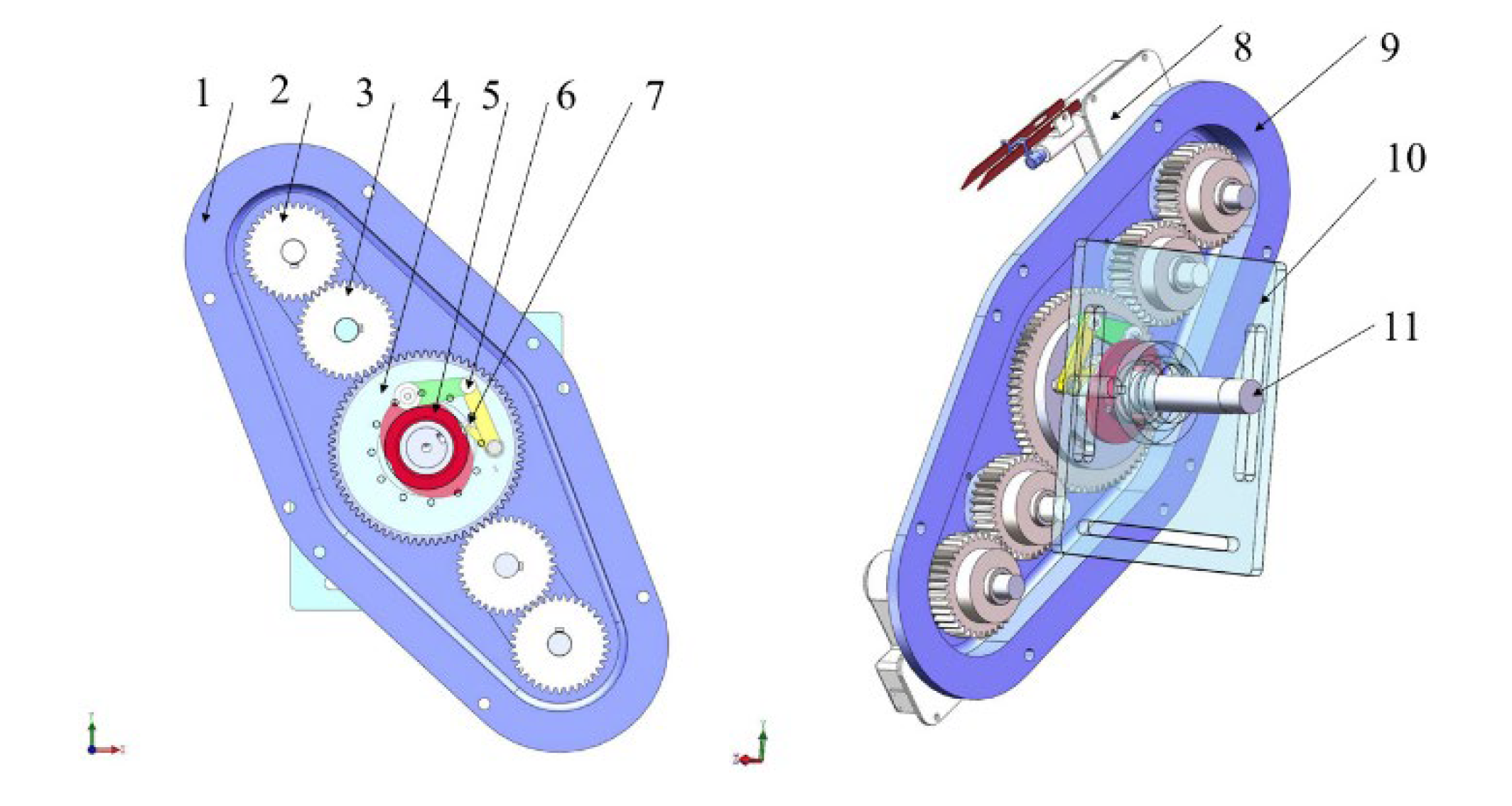

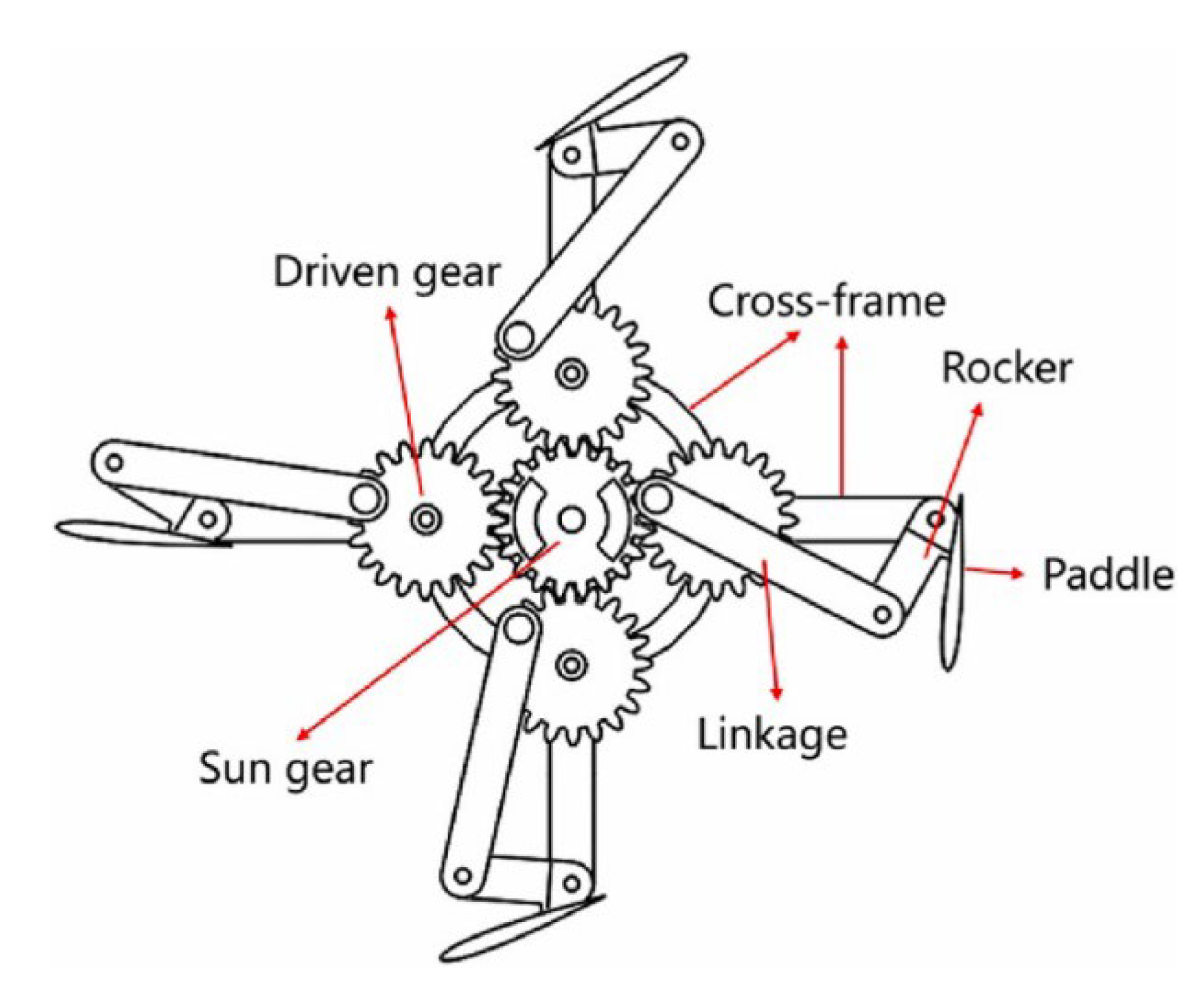

3.5. Planetary Rotary Transmission Mechanism

3.5.1. Cam Connecting Rod and Planetary Gear Combination Mechanism

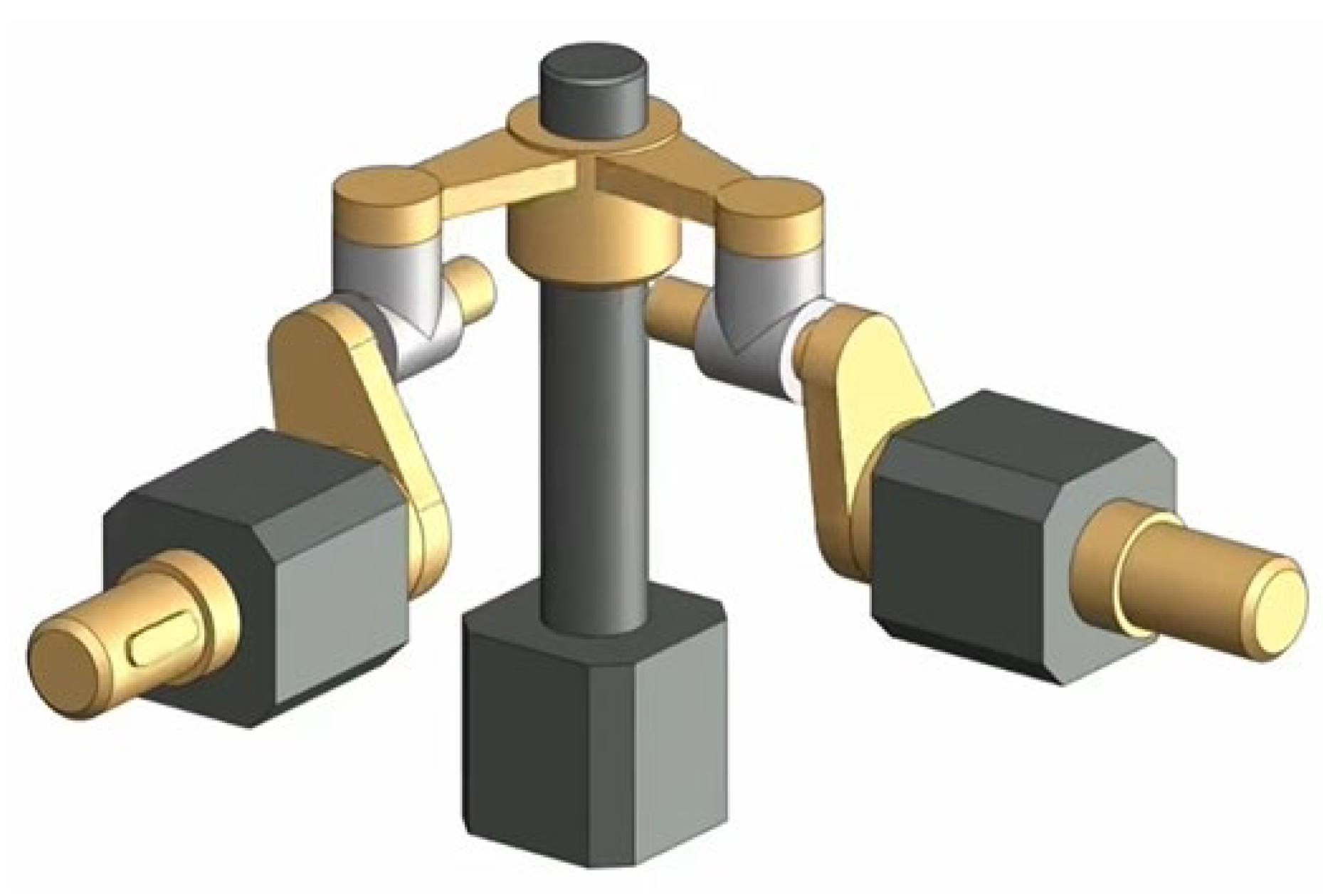

3.5.2. A New Propeller System Based on Planetary Gears and Crank Rocker Mechanism

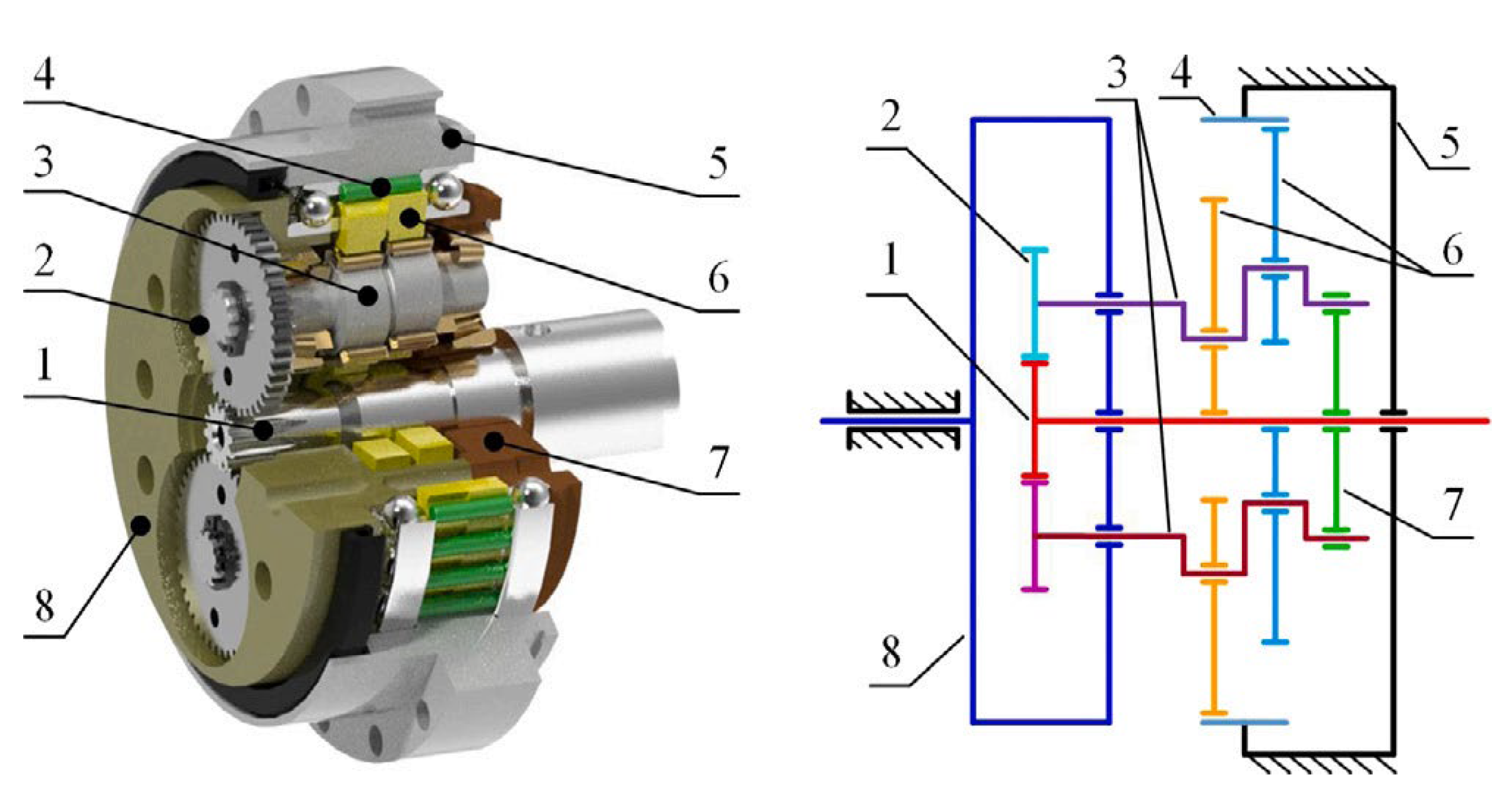

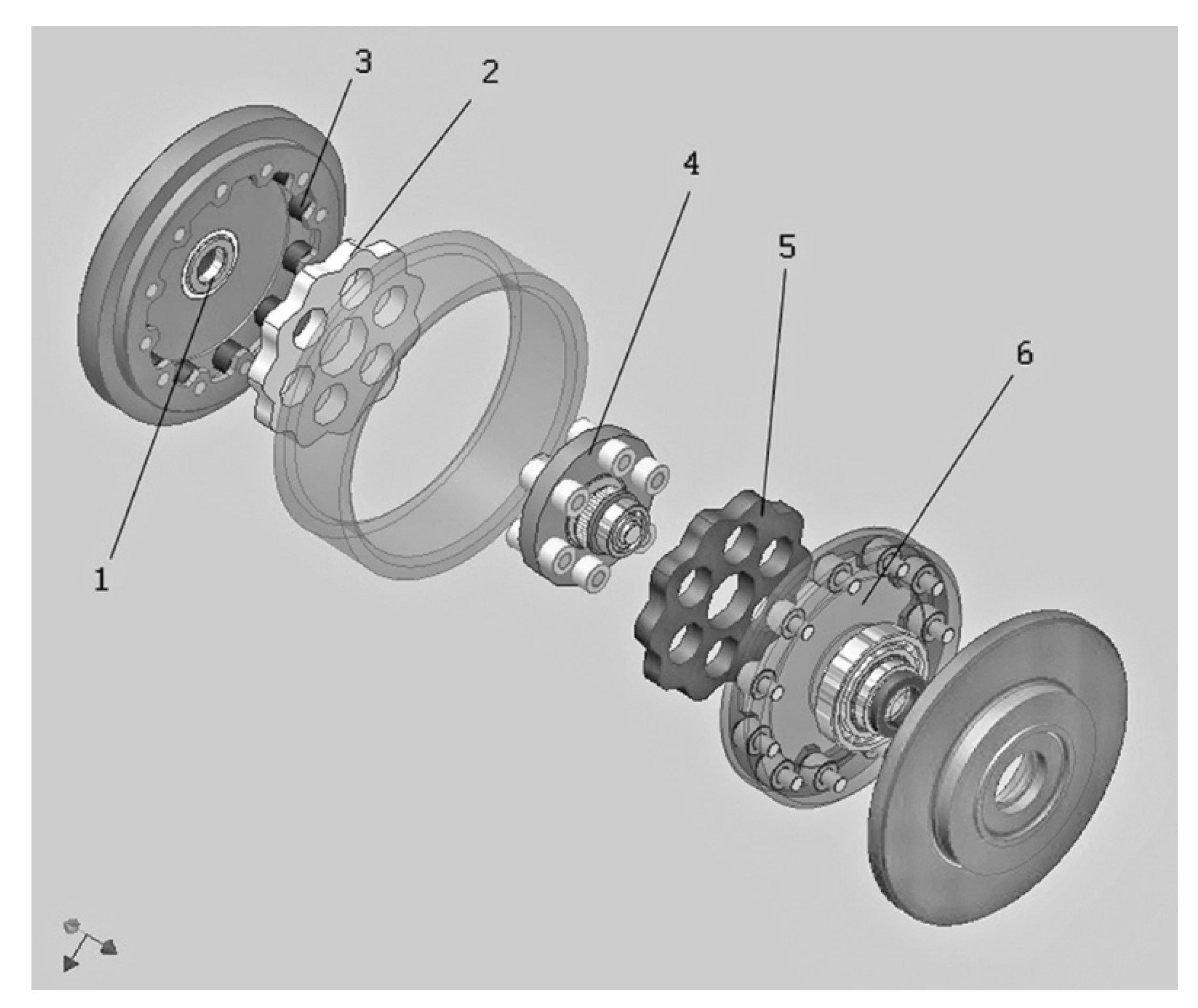

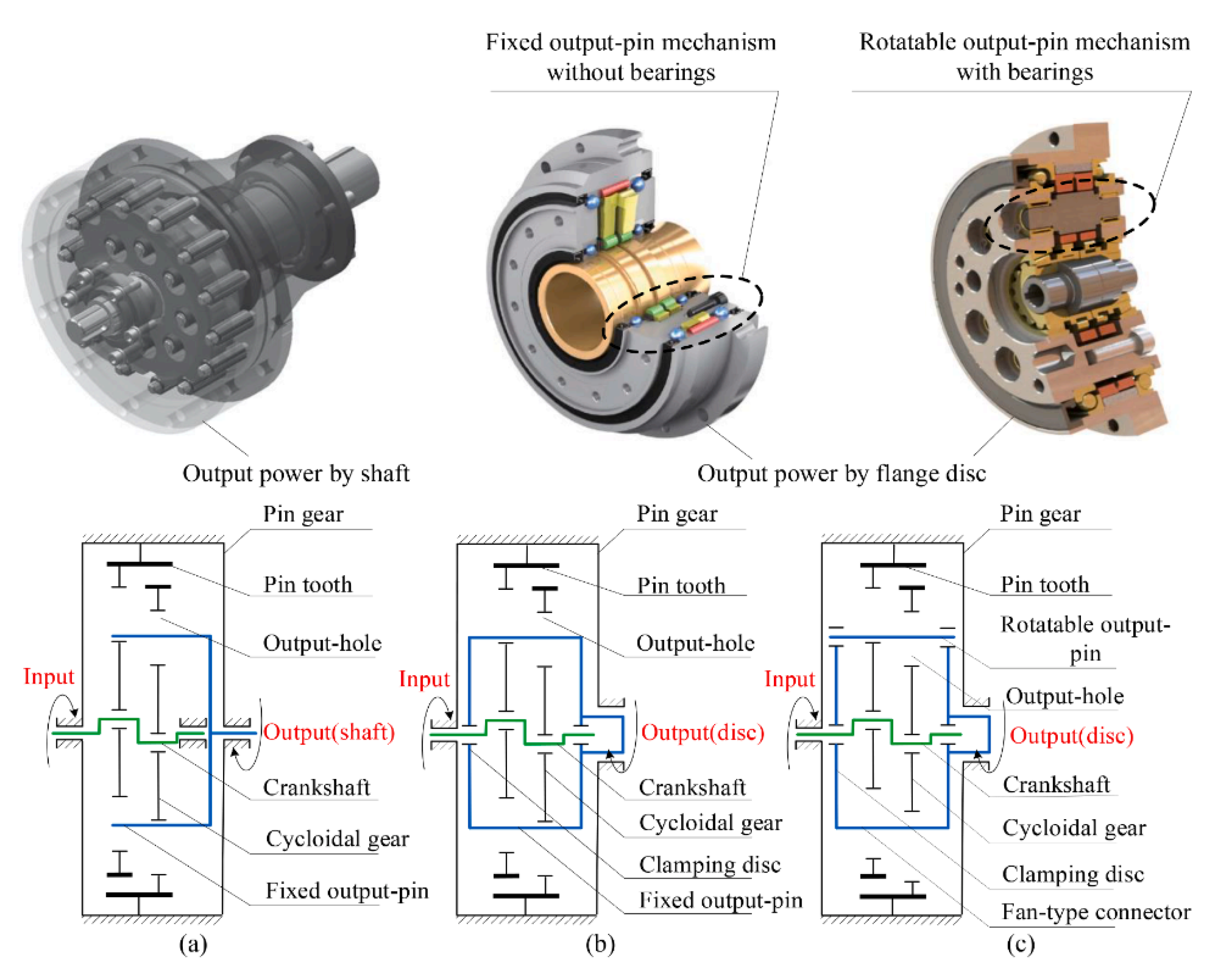

3.5.3. Cycloid Reducer

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cam connecting rod and planetary gear combination mechanism [135,136,137] | High stability, compact structure, high-speed operation, reliability | The cost is high, and the connecting rod requires high manufacturing accuracy | High-speed, low-damage vegetable transplanter and automated agricultural equipment for seedling extraction |

| Planetary gear and crank rocker propeller mechanism [138] | Real-time pitch control simplifies the transmission control of the system | Easy to wear and tear, poor vibration reduction | Ship propulsion, unmanned aerial vehicles |

| Universal RV reducer [139] | High transmission ratio and strong ability to withstand torque, high precision, and low recoil | High cost and difficult maintenance | Industrial robot joints and other high transmission ratio, high-precision demand scenarios |

| New two-stage cycloidal reducer [140] | Small size, Phase difference offsets centrifugal vibration, single tooth stress safety | Complex design and assembly, low efficiency | Compact and high transmission ratio scenarios such as robot joints |

| New single-stage precision cycloidal reducer [141] | High transmission efficiency, strong torsional stiffness, and simplified structure | High cost, the manufacturing process requires high standards | High efficiency and low friction loss scenarios such as precision instruments |

3.6. Rotary Actuator

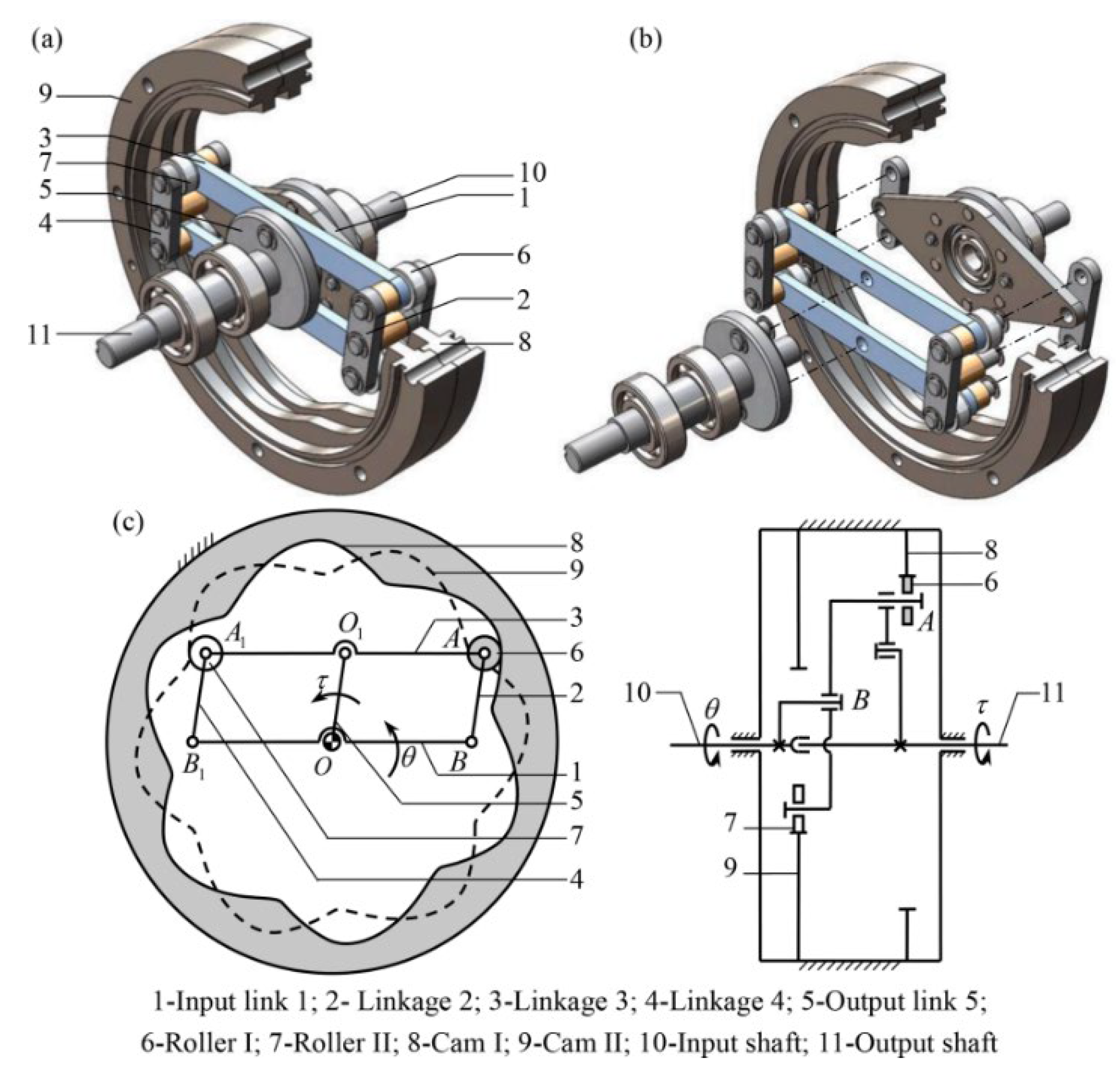

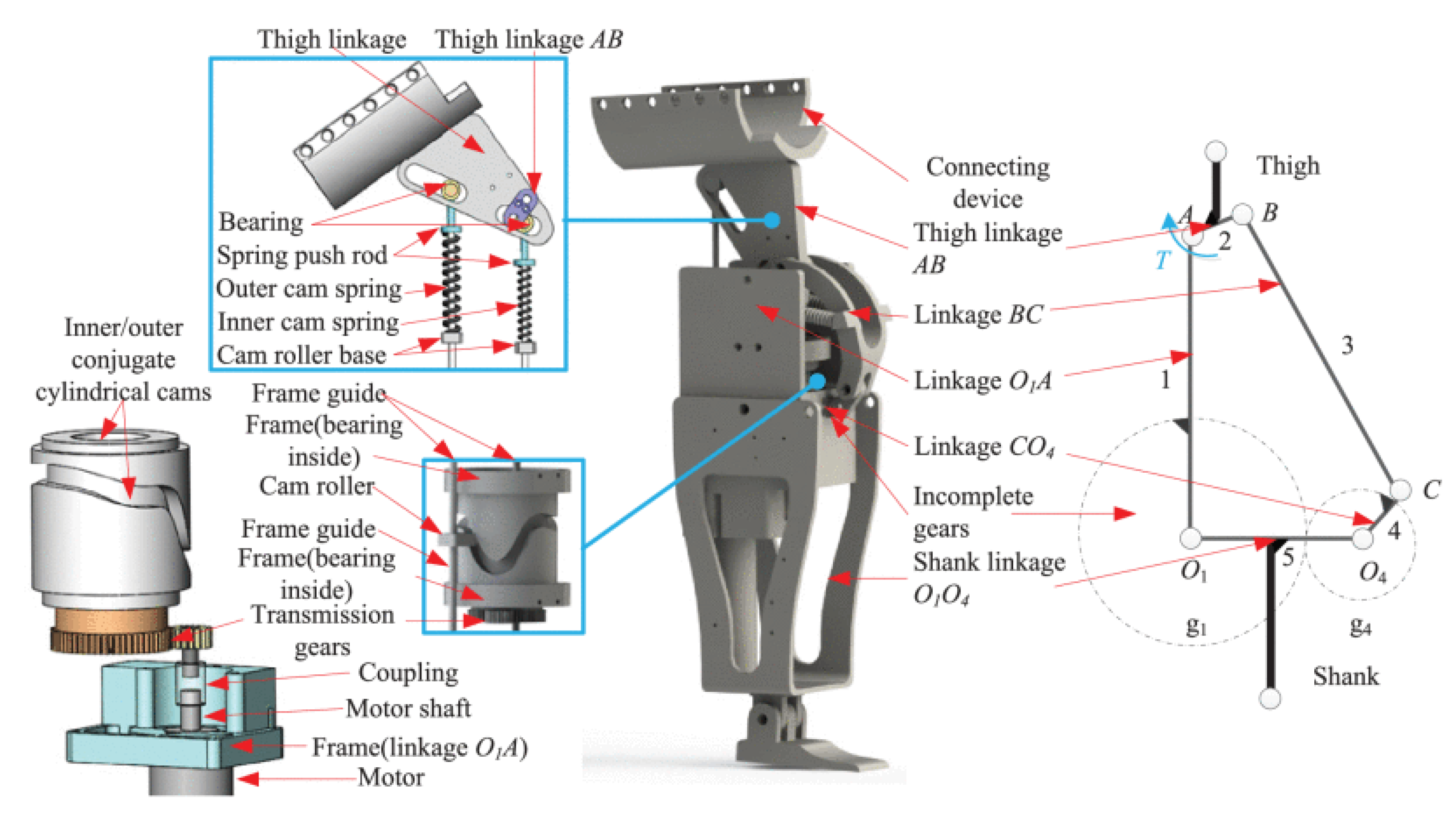

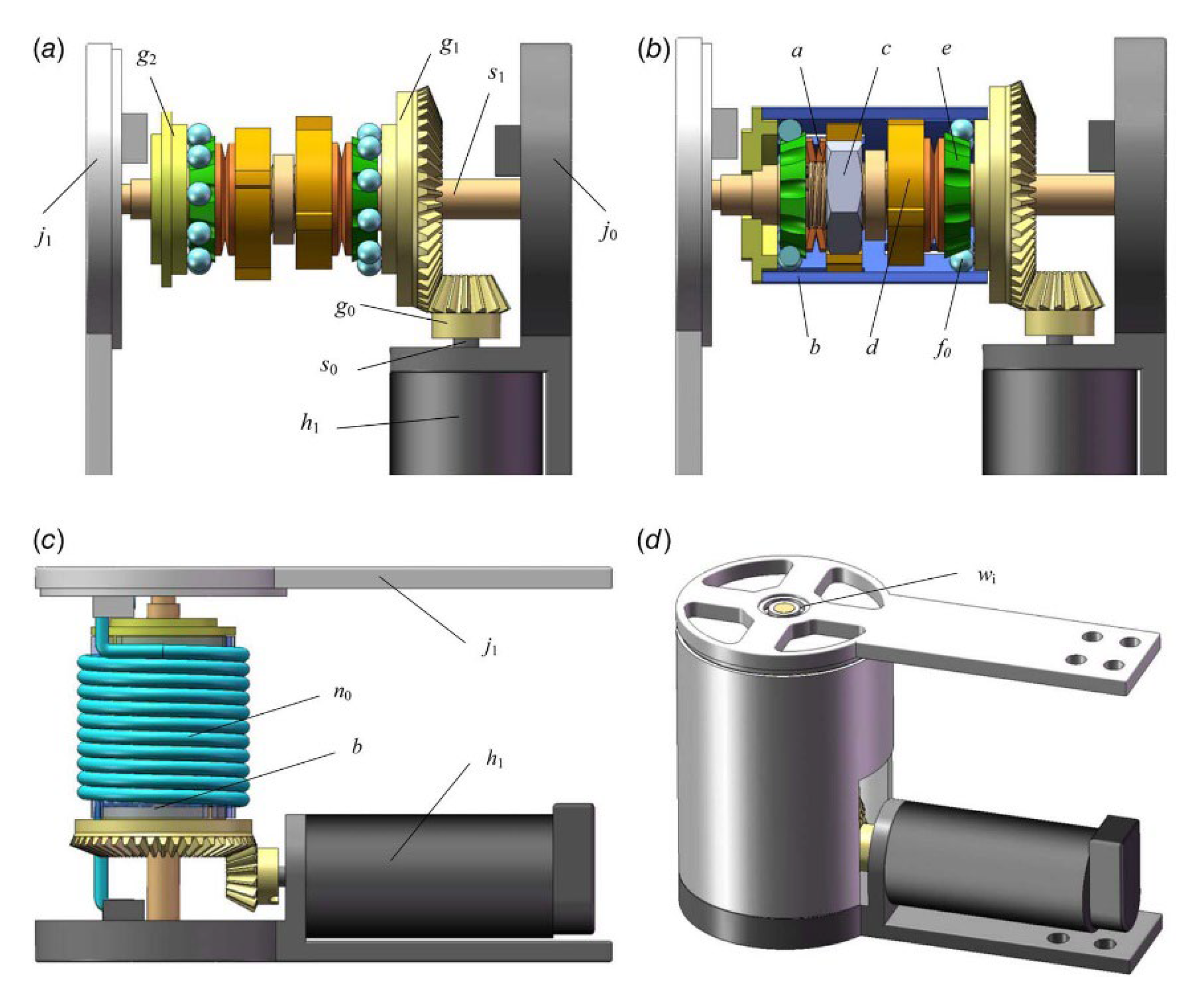

3.6.1. A Novel Nonlinear Series Elastic Actuator Based on Conjugate Cylindrical Cam (N3CSEA)

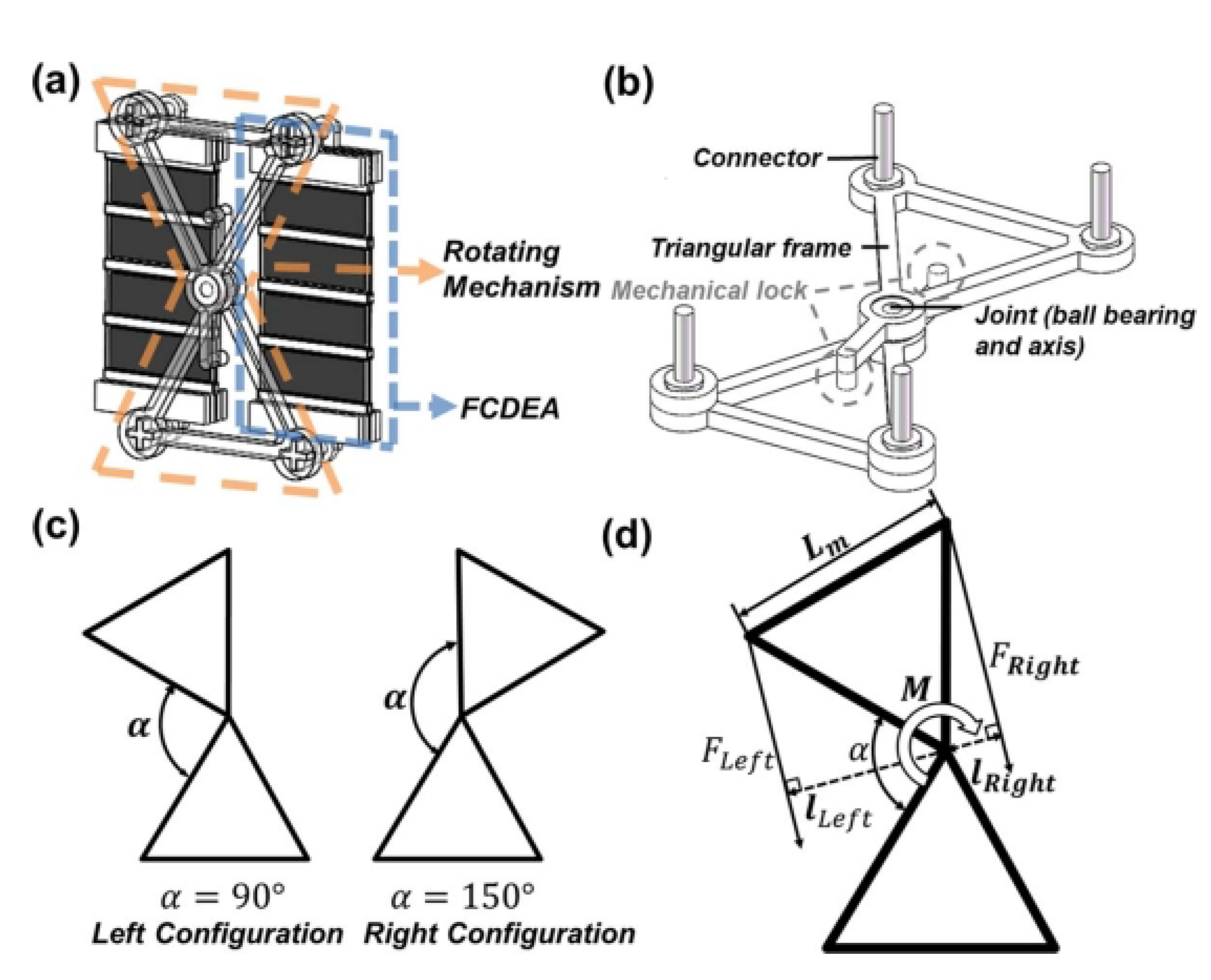

3.6.2. Bistable Rotating Mechanism

3.6.3. Twisted-Spring Connected Nonlinear Stiffness Actuator

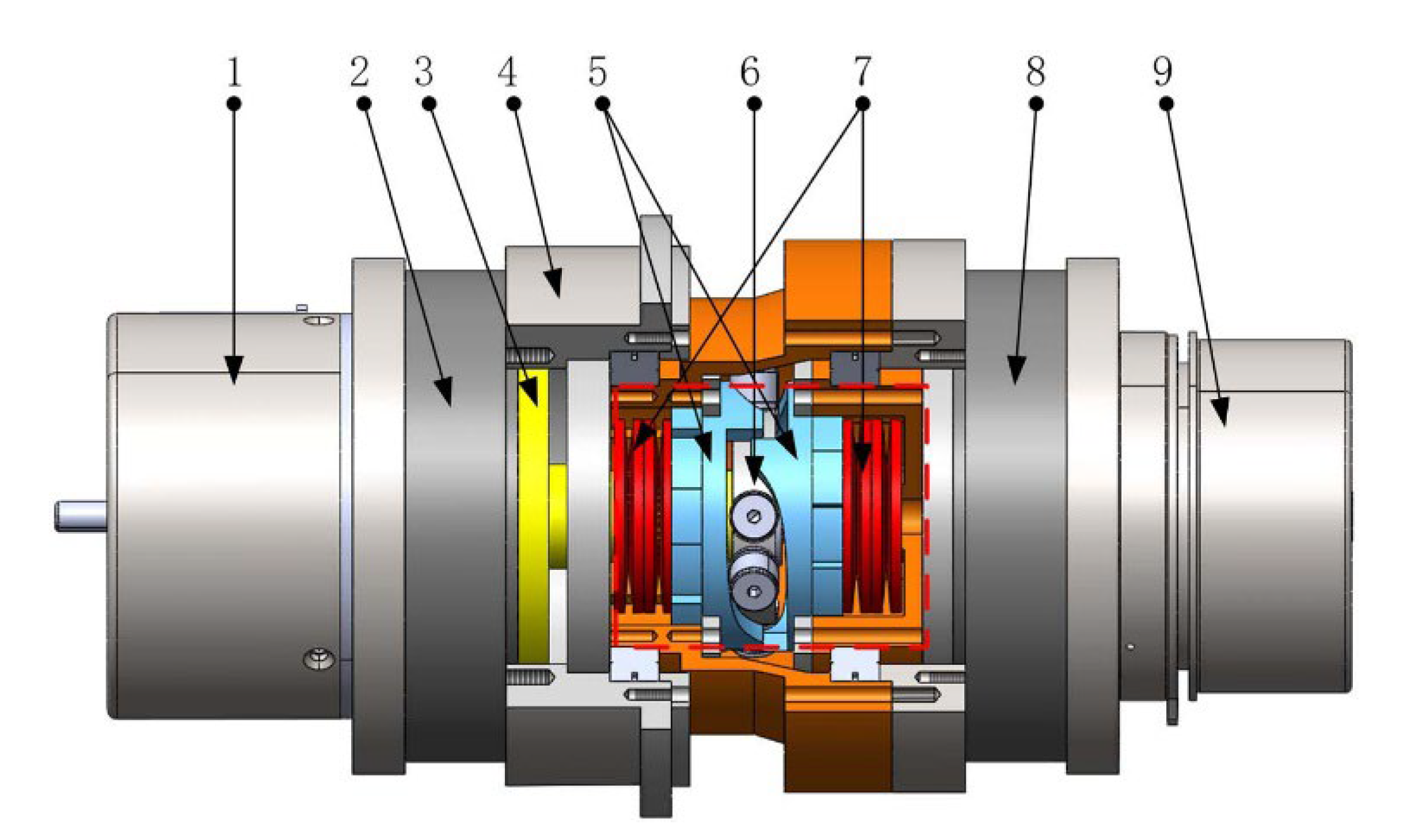

3.6.4. Compact and reconfigurable disc spring variable stiffness actuator

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Based on conjugate cylindrical cam [142] | Reduce motor inertia energy loss, compact structure | Dependent on cam design, high cost, limited adaptability | Artificial knee joint, low-power wearable assistive device |

| Bistable rotating mechanism [143] | Low energy consumption, repeatability, high precision, large load capacity | Relying on mechanical locks, the range of action is limited | Biomimetic robots or soft robots, medical surgical instruments |

| Twisted spring connected nonlinear stiffness actuator [144] | Wide adaptability, lightweight, and improved safety through biomechanical properties, low-cost | Complex structure, relying on cam profile optimization, limited real-time performance | Human-robot collaborative robots, highly dynamic environment walking robots |

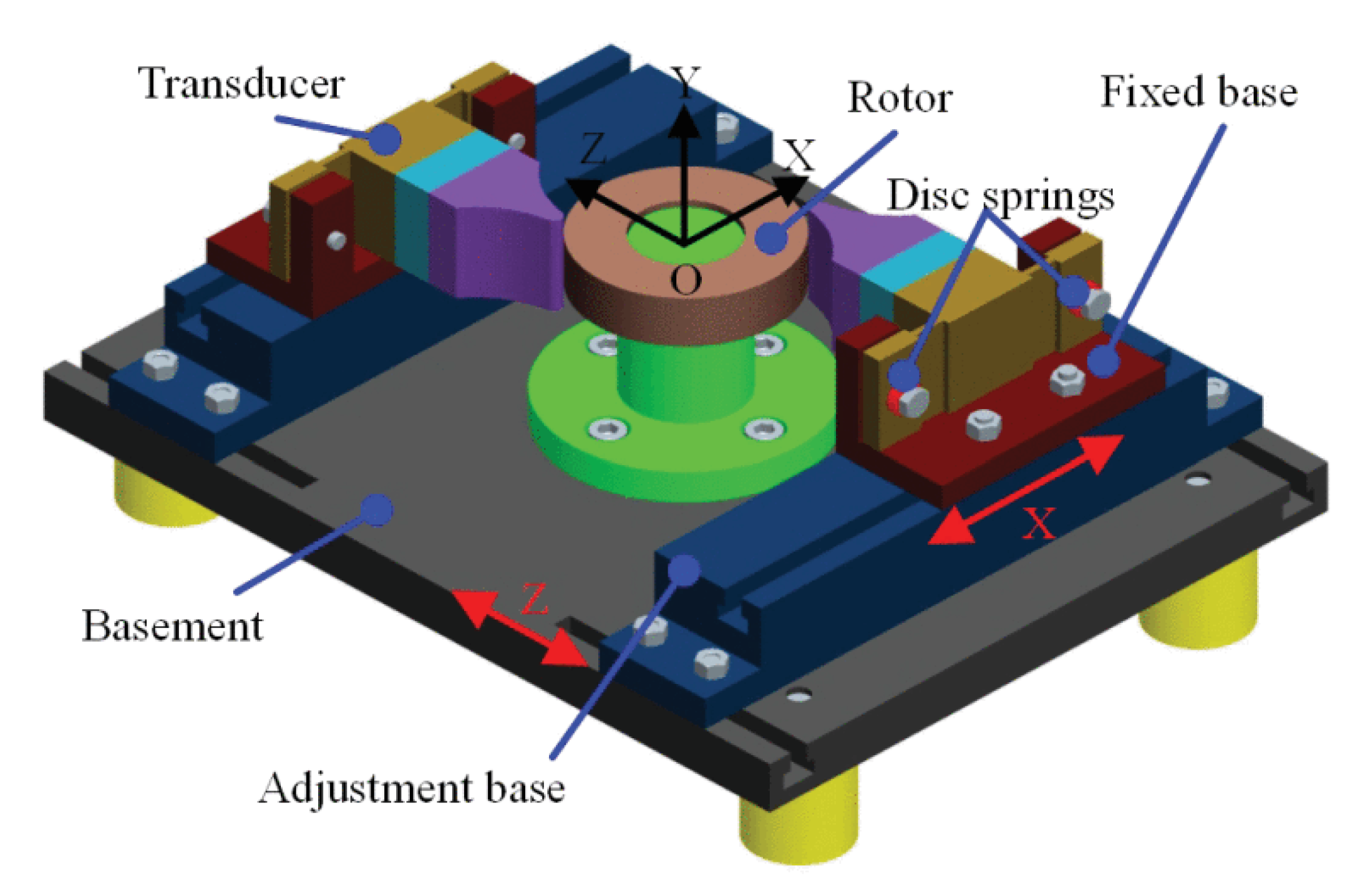

| Disc spring variable stiffness actuator [145] | Flexible configuration of equivalent stiffness, high torque density, fast and wide range stiffness adjustment | Multiple motors need to be coordinated for control, and fatigue of the disc spring may affect long-term reliability | Humanoid/quadruped robots, exoskeleton/rehabilitation robots, robot arm joint |

3.7. Cardan Drive

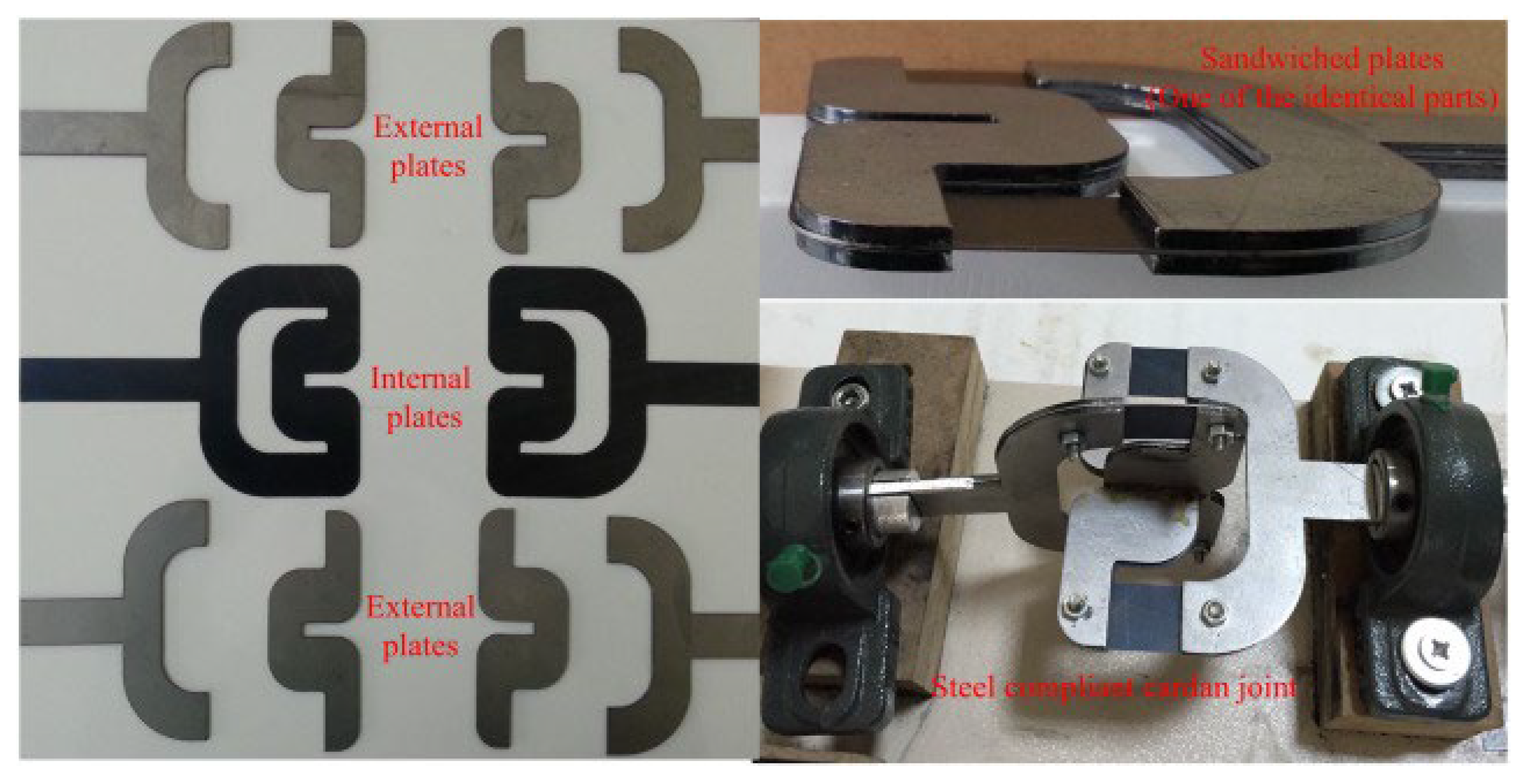

3.7.1. Steel Flexible Universal Joint

3.7.2. New Type of Anti-Buckling Flexible Universal Joint

3.7.3. New Type of Fully Compliant Universal Joint

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steel flexible universal joint [146] | Balancing elasticity and strength, no need for lubrication, lightweight and compact, long lifespan | Elastic deformation may lead to a decrease in transmission accuracy | Compact transmission, high-reliability joint without lubrication |

| Anti-buckling flexible universal joint [147] | High stability, high precision of dual axis rotation, no need for lubrication | Complex structure, high cost, and limited load-bearing capacity by tension plates | Optical positioning platform/surgical robot joint, continuum robot flexible arm segment |

| Fully compliant universal joint [148] | Single-piece structure does not require assembly, approximate constant speed transmission, flexible | High torque/large angle can easily cause stress concentration, and polypropylene material has low strength | Small robot/drone joints, lightweight transmission of medical equipment, noise-sensitive scenes |

3.8. Other Rotary Transmission Mechanisms

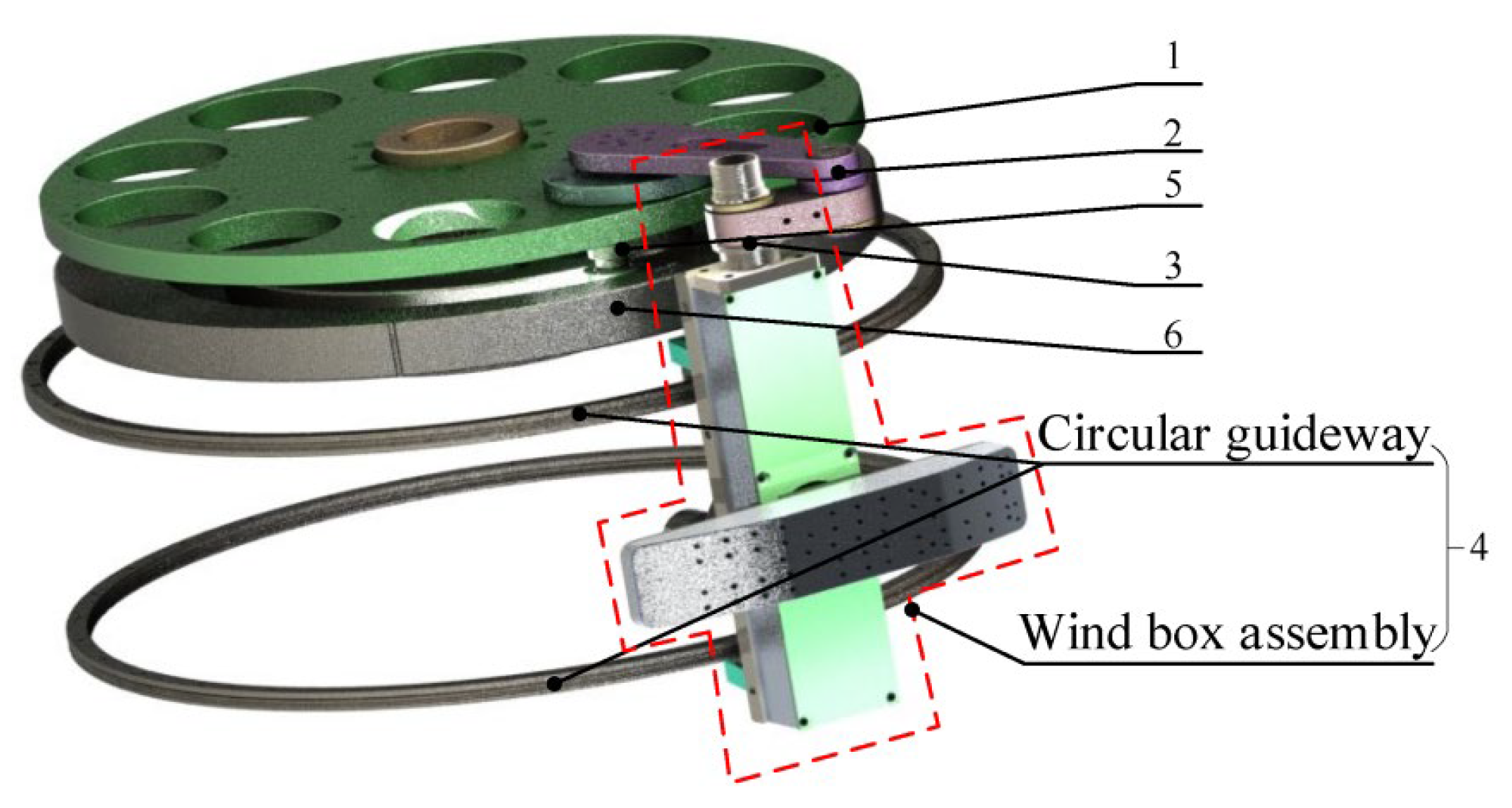

3.8.1. Right Angle Transmission Mechanism

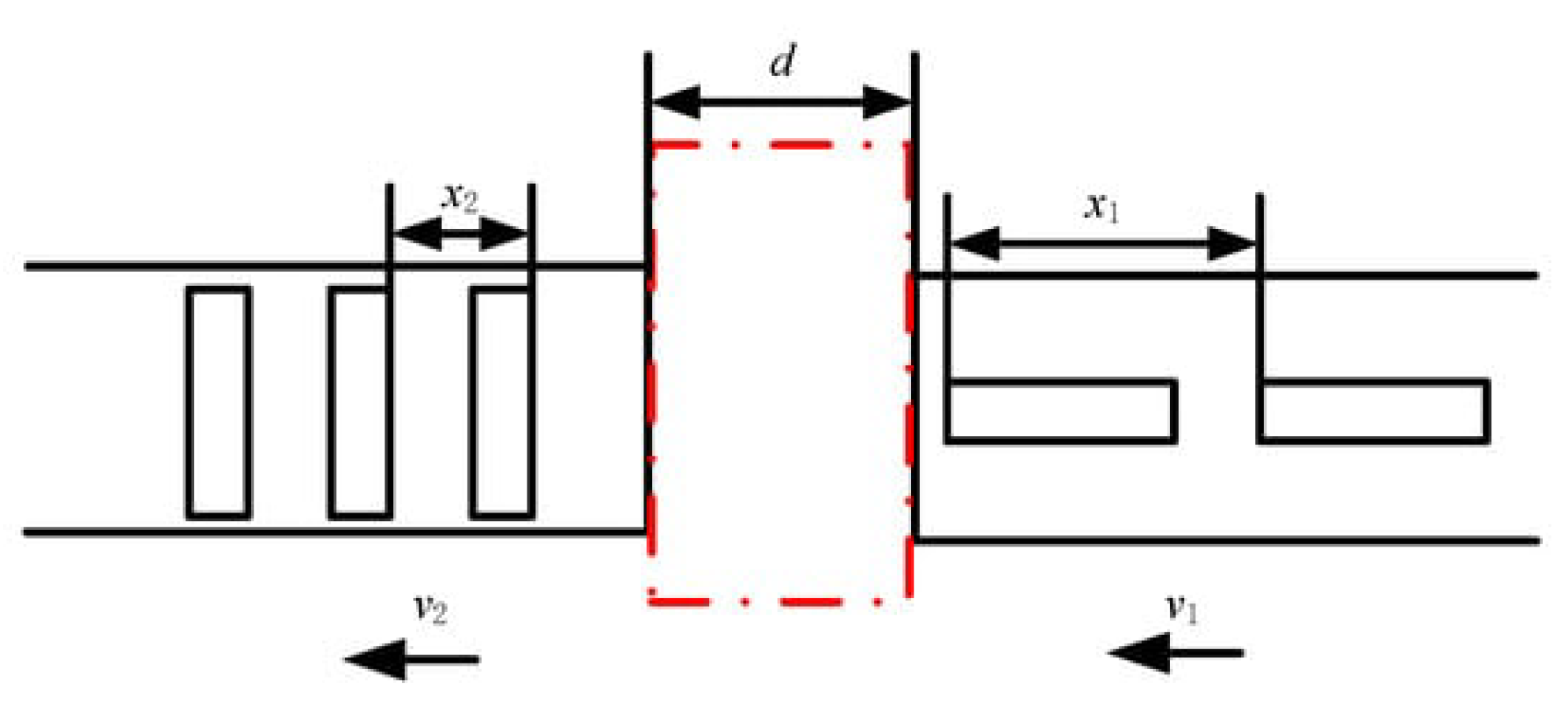

3.8.2. Forward and Reverse Conversion Mechanism

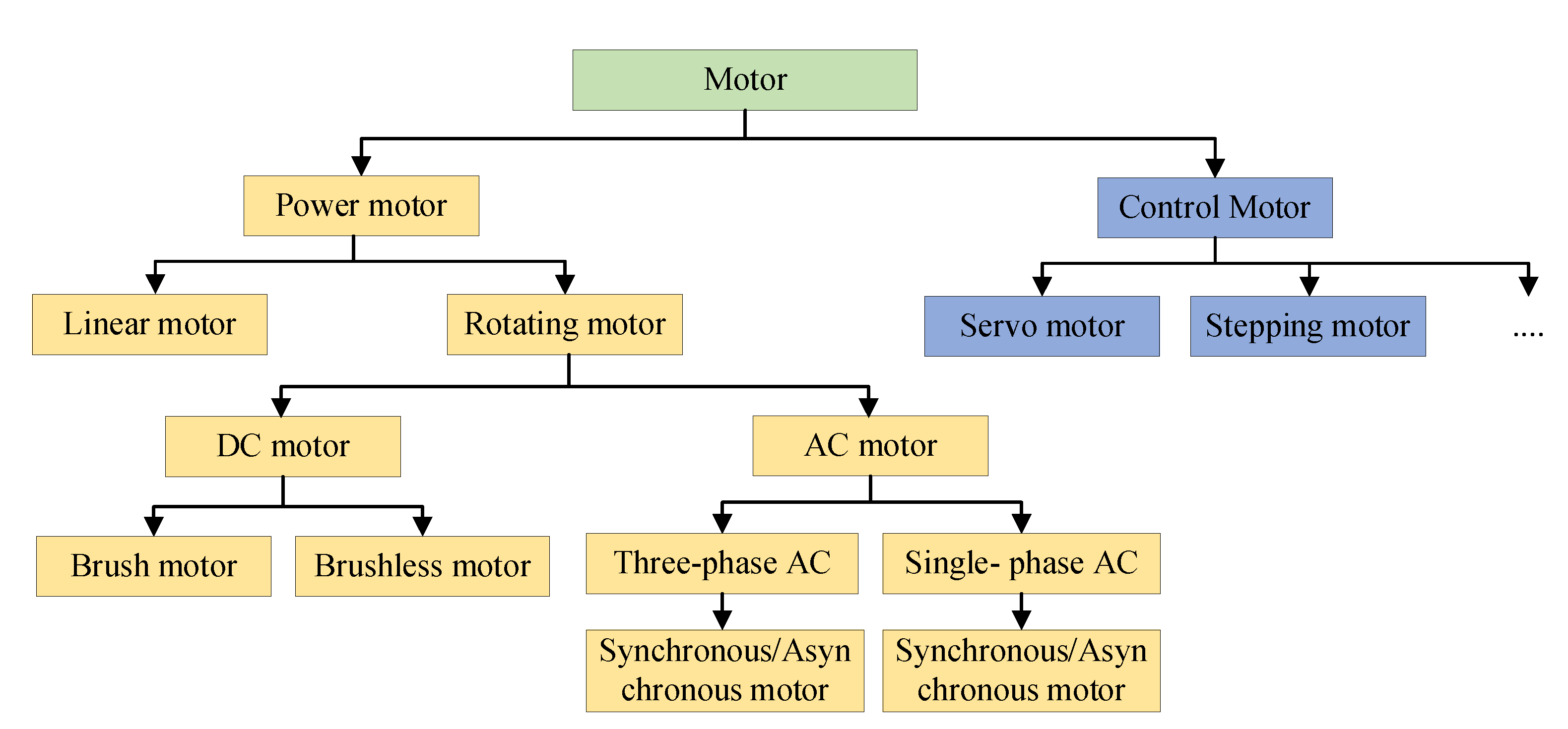

4. Common Driving Methods for Rotating Motion Mechanisms

4.1. Electric Drive

4.1.1. Motor Drive

| Types | Working principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

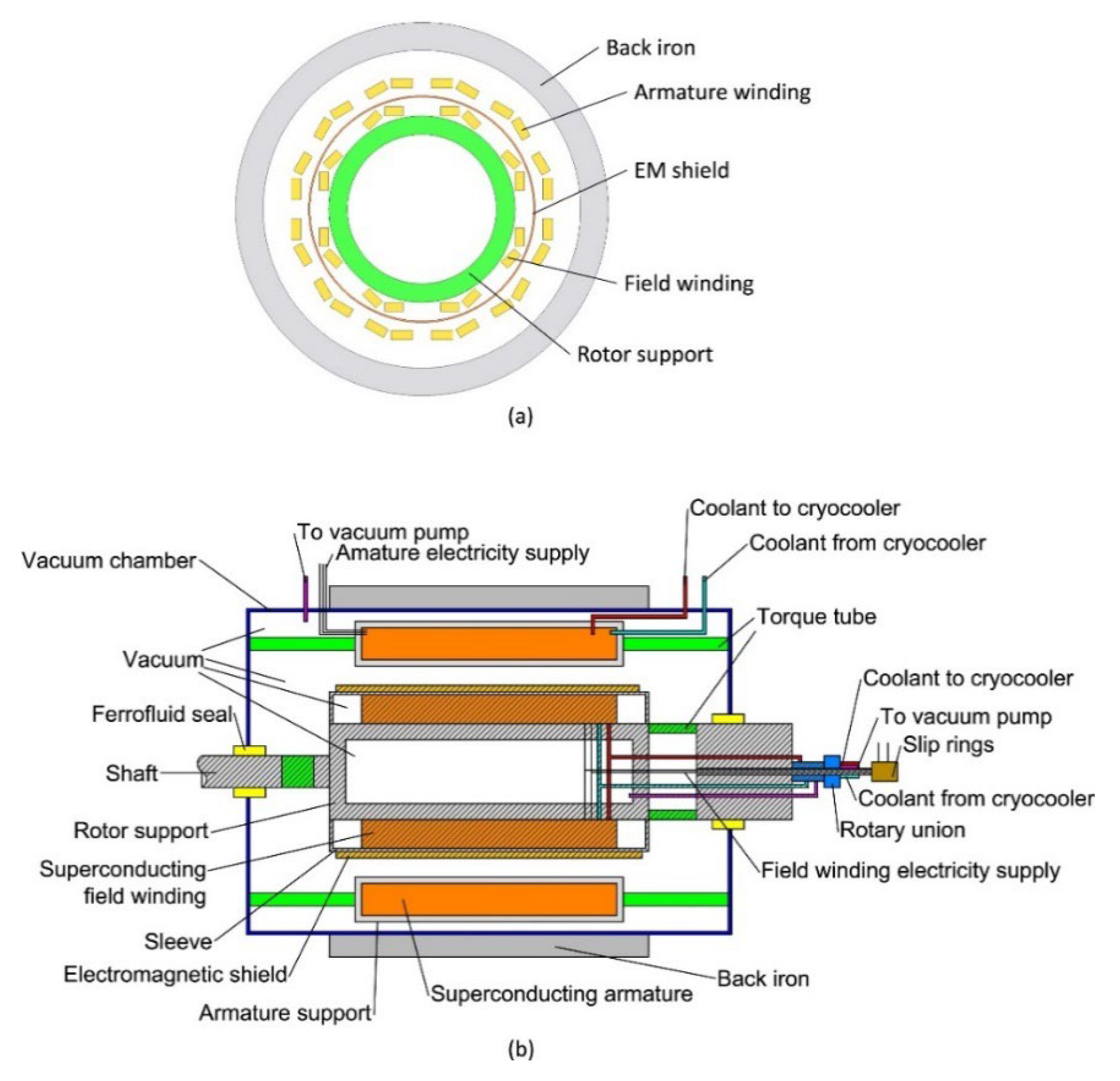

| Synchronous motor [156,157,158] | The rotor uses superconducting coils or blocks to generate a direct current magnetic field, while the stator is made of conventional conductors or superconducting materials. | High efficiency, lightweight, high magnetic field, low synchronous reactance | The cooling system is complex, with communication losses, requiring rotational cooling coupling | Wind turbines, ship propulsion, aerospace, industrial motors |

| Induction motor [159,160] | The rotor adopts superconducting squirrel cage bars, and the stator is a conventional conductor; The superconducting material loses its superconducting state during startup and returns to its superconducting state during operation. | High starting torque, low slip operation, high efficiency | In synchronous mode, the rotor magnetic field is limited and precise cooling control is required | Electric vehicles, industrial motors, low-temperature fluid pumps |

| Claw pole motor [161,162,163] | The stator superconducting coil guides the magnetic field through a claw pole structure, and the rotor is made of conventional materials. | Compact structure, non-rotating superconducting components, suitable for high-speed applications | The magnetic field distribution is uneven, and high mechanical strength is required for the claw pole | Aircraft generators, high-power density motors |

| Unipolar motor [164,165,166] | The DC magnetic field is generated by superconducting coils, and the rotor is a conductive disk or offset magnetic pole structure. | High torque, no gear requirements, suitable for low-speed and high-torque scenarios | Sliding contact is prone to wear and requires a liquid metal current collector | Ship propulsion, flywheel energy storage, aerospace high-power generators |

| Magnetic flux modulation motor [167,168,169] | Superconducting blocks or stacked tapes shield or concentrate magnetic fields, and the stator is a conventional conductor. | High power density, low magnetic leakage, and adaptability to complex shapes | Pulse magnetic field pre-magnetization is required, and demagnetization may occur during dynamic operation | Aerospace and high-power-density propulsion systems |

| Hysteresis motor [170,171] | Superconducting bulk rotors generate hysteresis effects in alternating magnetic fields to drive rotation. | Simple structure, no friction loss, suitable for high-speed applications | Hysteresis loss cannot be ignored, resulting in low output power | Micro-motors, specialized equipment for low-temperature environments |

| Fully superconducting motor [172,173,174] | Both the stator and rotor are made of superconducting materials (wires or blocks). | Theoretical efficiency is close to 100%, with a small size and extremely light-weight | High communication loss, complex cooling system, and extremely high cost | Future aviation propulsion and ultra-efficient power generation system |

4.1.2. Piezoelectric Drive

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal vibration mode rotating ultrasonic motor [182] | Simple control, adjustable output characteristics, stable torque, and no magnetic interference | High voltage drive, high power consumption, low output torque, and speed | Optical instrument focusing system, micro robot joint drive, low temperature/vacuum environment |

| Non-contact ultrasonic motor [183] | No contact friction, long lifespan, no wear and heat accumulation, fast operating speed | Low torque may cause failure under high pressure/high load | Medical devices that require silent operation in high-precision cleaning scenarios such as semiconductor manufacturing |

| Gear mesh resonant piezoelectric motor [184] | High efficiency, high power output, flexible speed regulation, and resonance design improve energy efficiency | The adjustment of resonant frequency is complex, and high-frequency vibration may generate noise | Scanning probe microscope for nano-positioning, joint drive for surgical robots, high torque velocimeter in precision manufacturing |

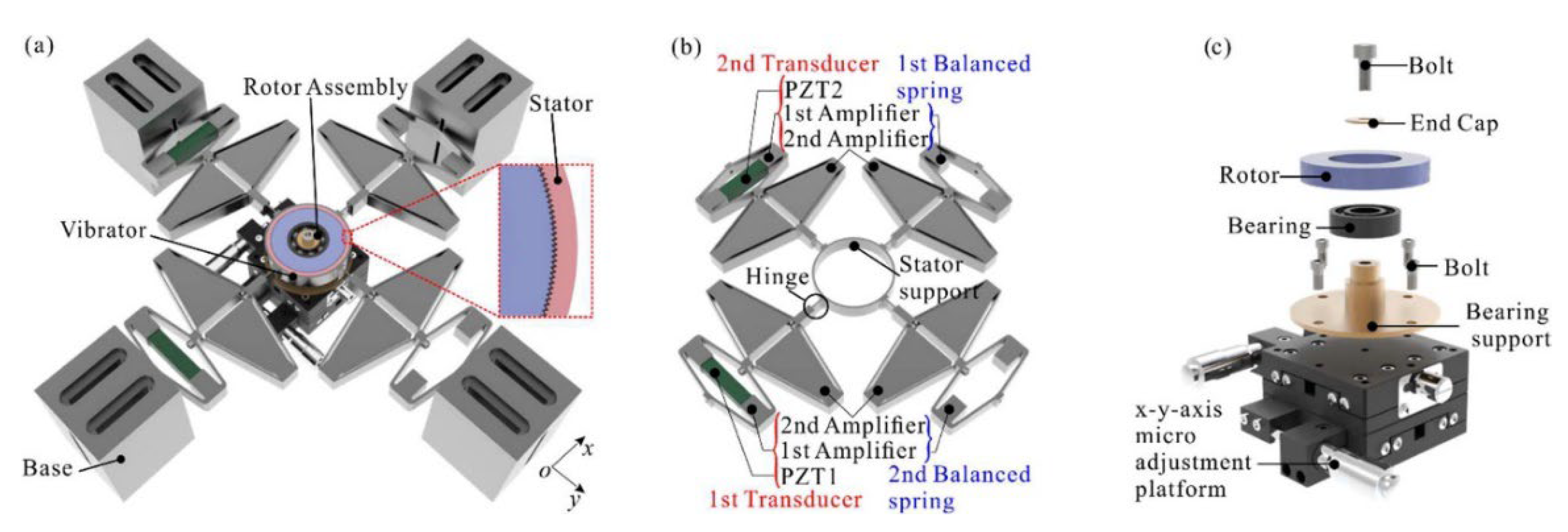

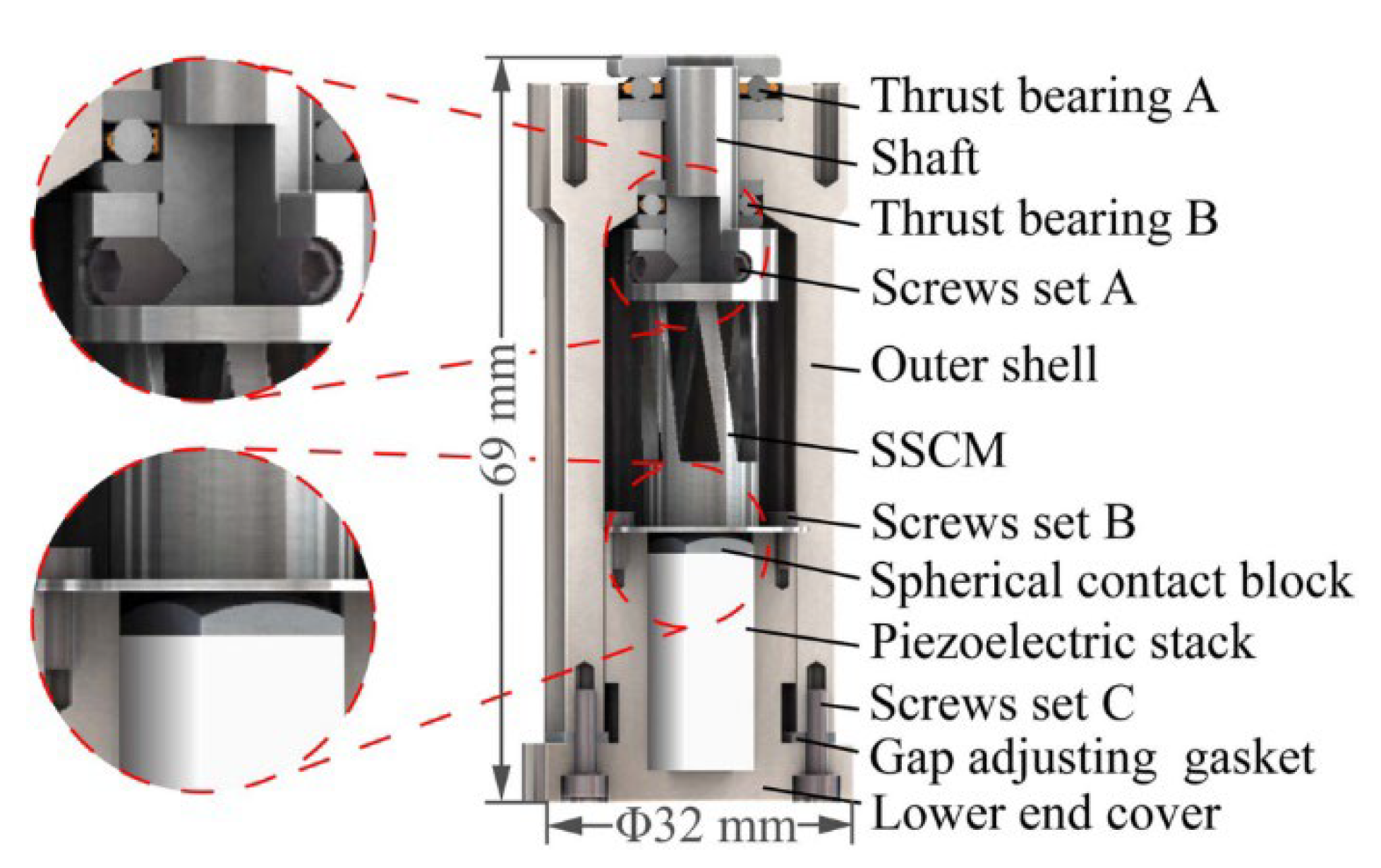

| Space Spiral Flexible Mechanism (SSCM) RPA [185] | High precision and fast response, high motion stability, low cost, no axis offset | Limited output torque, susceptible to material fatigue, sensitive to installation accuracy | Biological microscope, nano-positioning platform and other micro-nano operation scenarios, dynamic vibration compensation system |

4.2. Hydraulic Drive

4.2.1. Electro-Hydraulic Servo Drive

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional hydraulic drive [186] | High load, precise movement, smooth operation, seamless transmission, and rapid response | Potential leakage risk, high maintenance cost, and loud noise | Scenarios that require high load and precise control |

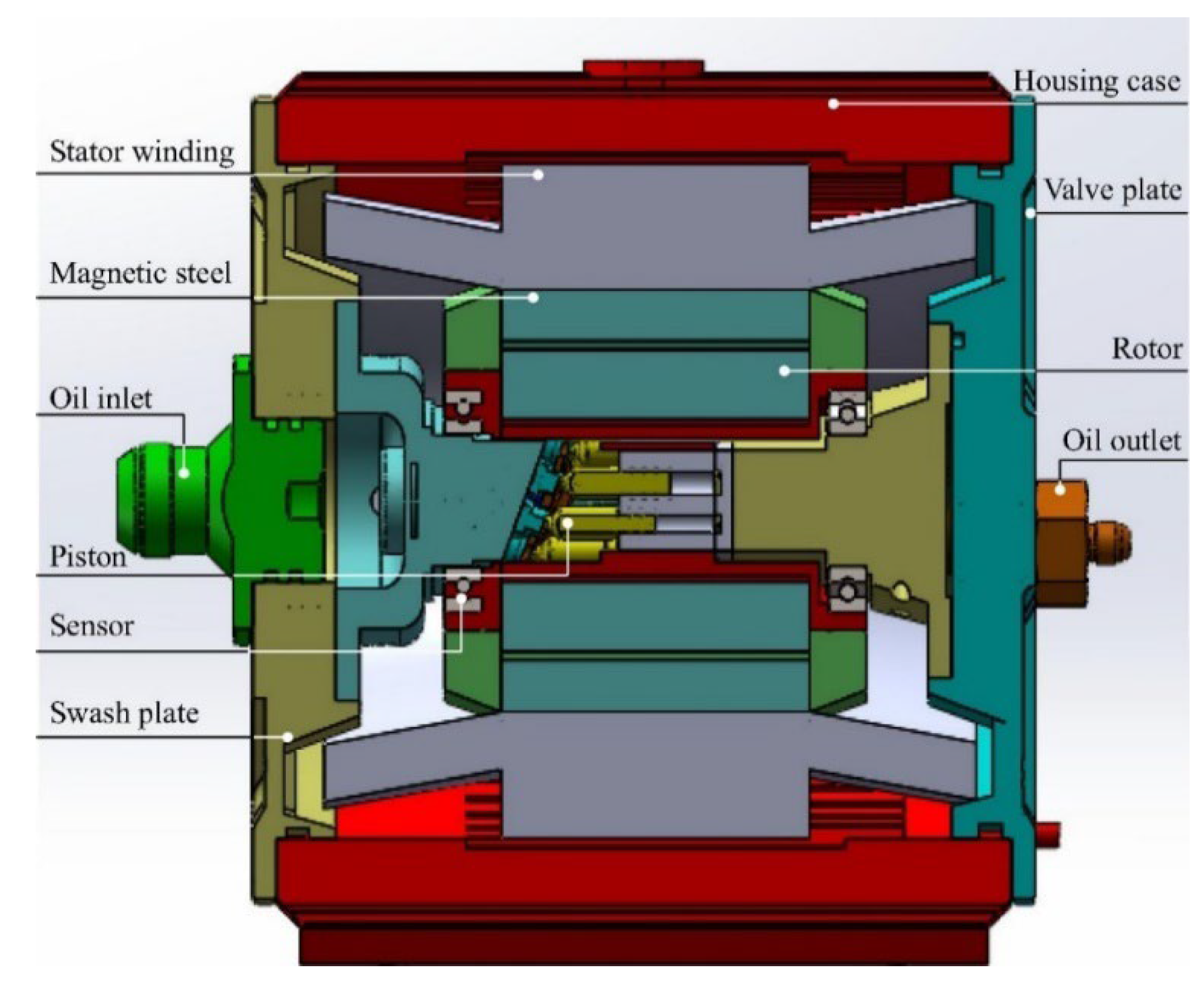

| Electrohydraulic servo drive [187] | Small size, lightweight, high-power density, low noise, good dispersion performance, high reliability | Insufficient oil absorption during high-speed operation leads to reduced efficiency and vibration | Aircraft hydraulic systems require equipment in environments with sustained high-pressure or low-noise levels |

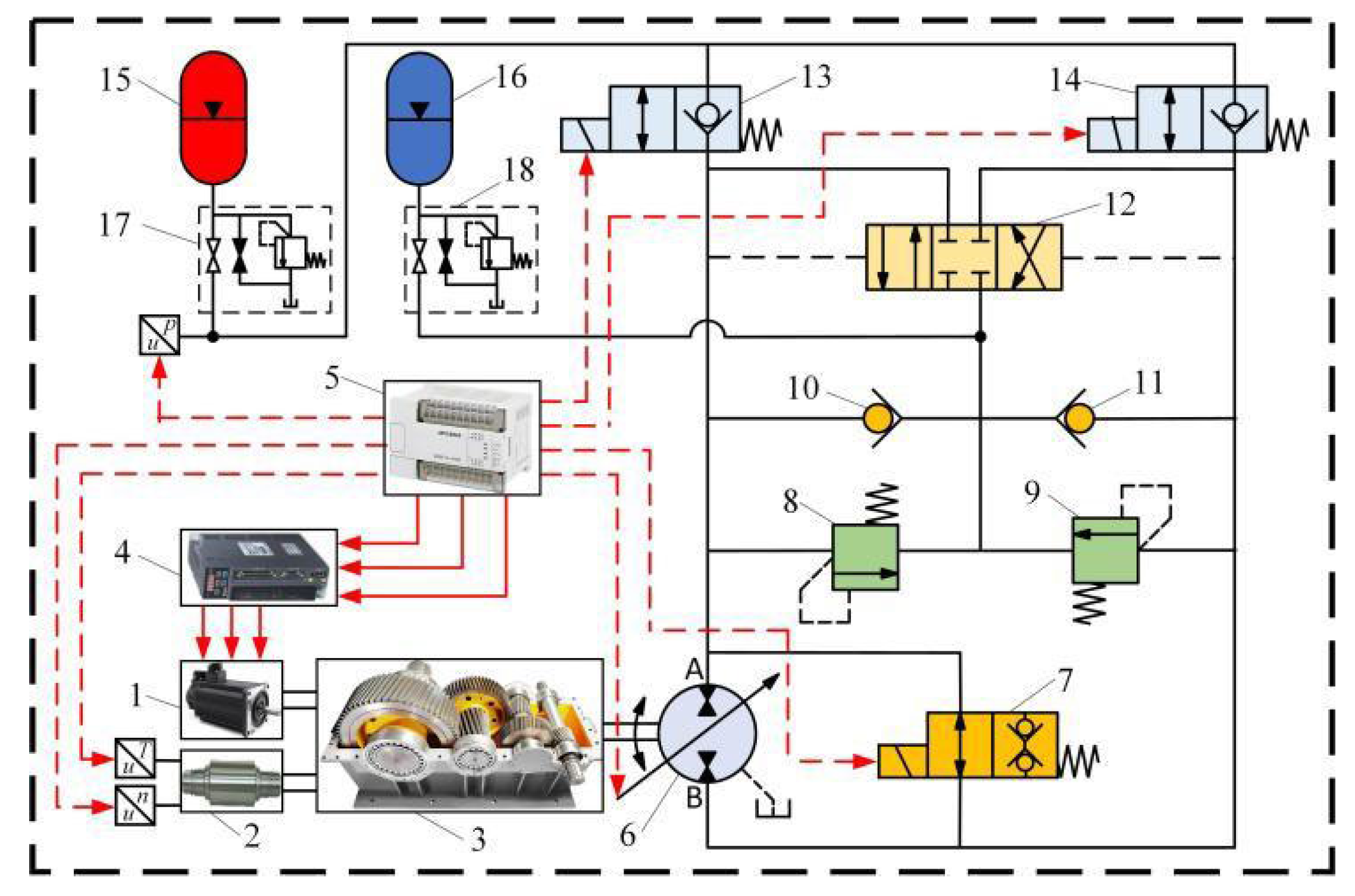

| Electrohydraulic servo drive [188] | Energy regeneration, reducing the peak power and energy consumption of the motor, and cooling down | The system requires precise control, additional energy storage devices, and pipelines | High inertia frequent start stop scenarios, green and low-carbon industrial applications |

4.3. Pneumatic Drive

4.3.1. Multi Mode Pneumatic Motor

4.3.2. Pneumatic Artificial Muscles

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional pneumatic drive [189,190,191,192] | Environmental protection, strong adaptability, fast response, easy to automatically control | Low torque, accuracy affected by pressure fluctuations and elastic components, high noise | Industrial robots and automation scenarios in harsh environments |

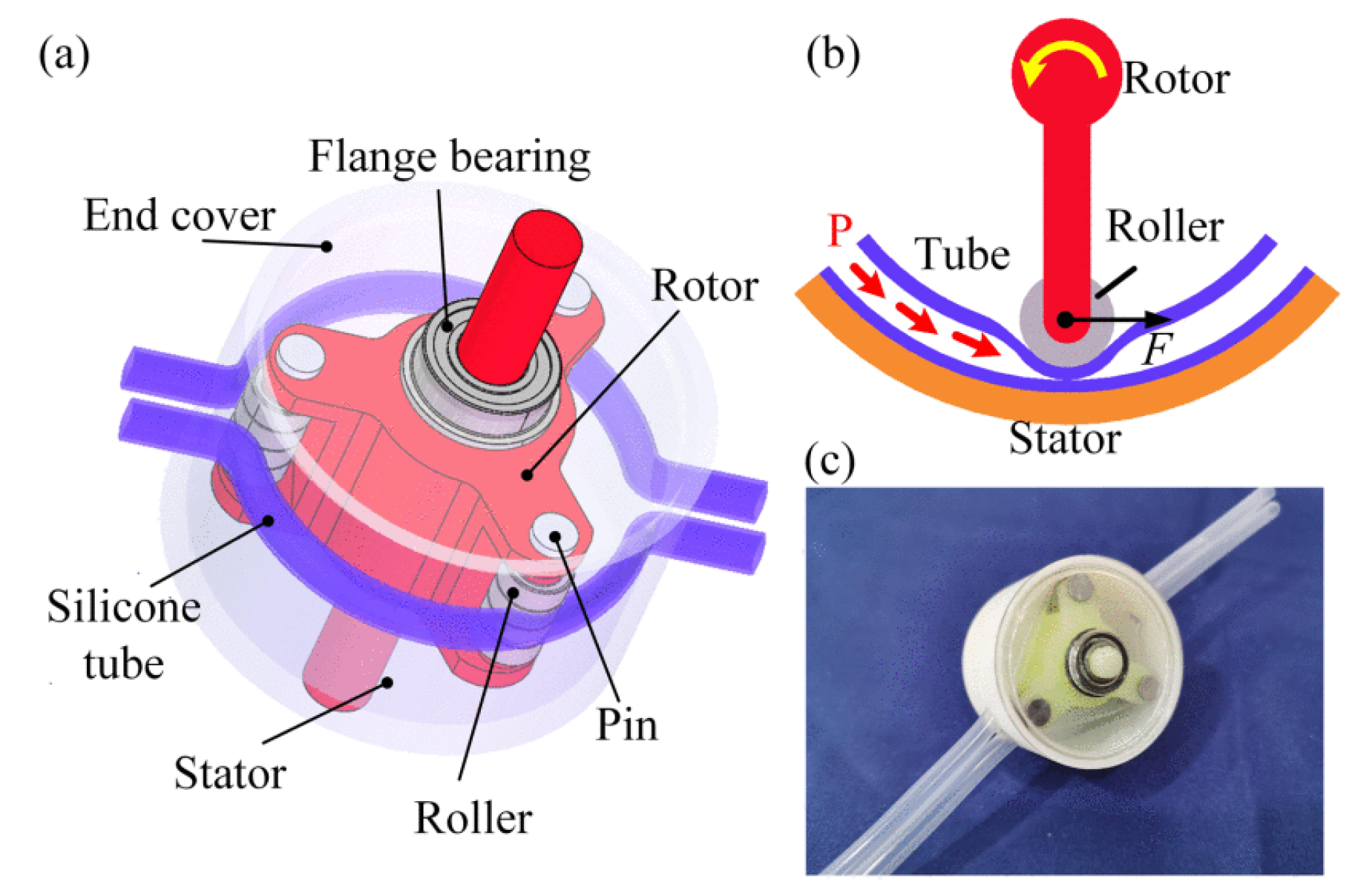

| Multi-mode pneumatic motor [193] | Supports continuous rotation and step mode switching, with good output performance and low-cost | Accuracy is affected by the elastic deformation and inertia of silicone tubing | Light load scenarios of pipeline robots, modular robotic arms, and fast mode switching |

| Pneumatic artificial muscles [194] | Flexibility and high precision, no stick-slip phenomenon, high-precision positioning | The maximum pressure limit restricts the torque output | Flexible robot joints, precision assembly, medical equipment |

5. Conclusions and Future Research Direction

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Future Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, K.L.; Yang, Y.X.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, Y.P. Haitao Ren Study on rock breaking mechanism of PDC bit with rotating module. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 192, 107312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, G.P.; Tang, S.N.; Wang, R.; Su, H.; Wang, C. Acoustic signal-based fault detection of hydraulic piston pump using a particle swarm optimization enhancement CNN. Applied acoustics 2022, 192, 108718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xu, B.; Wang, Q.N.; Lyu, F.; Li, K. Integrated slipper retainer mechanism to eliminate slipper wear in high-speed axial piston pumps. Frontiers of Mechanical Engineering 2022, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myszka, D.H.; Joo, J.J.; Murray, A.P. A Multi-Objective Mechanism Optimization for Controlling an Aircraft Using a Bio-Inspired Rotating Empennage. Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics 2022, 14(4), 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.Y.; Zhang, X. Numerical Study on Local Entropy Production Mechanism of a Contra-Rotating Fan. Entropy 2023, 25(9), 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satake, Y.; Takanishi, A.; Ishii, H. Novel growing robot with inflatable structure and heat-welding rotation mechanism. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2020, 25, 1869–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnowski, P.; Gładysiewicz, A.; Gładysiewicz, L.; Król, R.; Ozdoba, M. Conveyor Intermediate TT Drive with Power Transmission at the Return Belt. Energies 2022, 15(16), 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, V.U.; Weiss, L.; Zogg, M.; Wegener, K. Analytical flat belt drive model considering bilinear elastic behaviour with residual strains. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2023, 190, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.C.; Liang, X.; Jiang, T. Performance analysis of escalator drive chain plate used for 5 years. In 2020 5th International Conference on Mechanical, Control and Computer Engineering (ICMCCE). IEEE 2020, 788-791.

- Jiang, S.; Huang, S.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, S.J.; Lv, J.W.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Qu, W. Dynamic characteristics of the chain drive system under multiple working conditions. Machines 2023, 11(8), 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Q.; Zhang, D.; Tian, C.X. A family of generalized single-loop RCM parallel mechanisms: structure synthesis, kinematic model, and case study. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2024, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, B. Bionics design and dynamics analysis of space webs based on spider predation. Acta Astronautica 2019, 159, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yan, Y.; Yi, Z.Y. Bionic design and experimental study for the space flexible webs capture system. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 45411–45420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, K.; Ma, X.; Chen, X.; Hu, S.H.; Tang, Q.Y.; Liu, Z.J.; Ding, M.X.; Han, S. J. Optimal design and implementation of an amphibious bionic legged robot. Ocean Engineering 2023, 272, 113823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.G.; Li, R.Y.; Song, Z.P. Bionic muscle control with adaptive stiffness for bionic parallel mechanism. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2023, 20(2), 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ge, W.J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, B.; Liu, B.; Jin, S.K.; Li, Y.Z. Optimization Design and Performance Analysis of a Bionic Knee Joint Based on the Geared Five-Bar Mechanism. Bioengineering 2023, 10(5), 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.N.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, S.Q. Bionics-Inspired Structure Boosts Drag and Noise Reduction of Rotating Machinery. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2023, 20(6), 2797–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalders, J.W.G.; Wildeman, K.J.; Ploeger, G.R.; van der Meij, Z.N. New developments with the cryogenic grating drive mechanisms for the ISO spectrometers. Cryogenics 1989, 29(5), 550–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Noji, H.; Yengo, C.M.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Grainge, I. Biological nanomotors with a revolution, linear, or rotation motion mechanism. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2016, 80(1), 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Tadakuma, K.; Konyo, M.; Tadokoro, S. Bundled rotary helix drive mechanism capable of smooth peristaltic movement. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2020, 5(4), 5537–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.W.; Huang, W.Q.; Liu, W.Q.; Xiao, JR.; Liu, X.C.; Liang, Z.W. Meshing drive mechanism of double traveling waves for rotary piezoelectric motors. Mathematics 2021, 9, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, B.; Kist, S.; Hamada, A. Wireless Piezoelectric Motor Drive. Actuators 2023, 12(4), 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.Y.; Liang, Y.; Xu, D.Z.; Wang, Z.H.; Ji, J. Design on electrohydraulic servo driving system with walking assisting control for lower limb exoskeleton robot. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2021, 18(1), 1729881421992286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milecki, A.; Jakubowski, A.; Kubacki, A. Design and Control of a Linear Rotary Electro-Hydraulic Servo Drive Unit. Applied Sciences 2023, 13(15), 8598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermehl,C. ;Jacobs,G.; Neumann, S. A modeling method for gear transmission efficiency in transient operating conditions. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2020, 153, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, O.; Nosko, P.; Fil, P.; Nosko, O.; Olofsson, U. Prevention of resonance oscillations in gear mechanisms using non-circular gears. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2017, 114, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristivojević, M.; Lučanin, V.; Dimić, A.; Mišković, Z.; Burzić, A.; Stamenić, Z.; Rackov, M. Investigation of the heavy duty truck gear drive failure. Engineering Failure Analysis 2023, 144, 106995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidu.https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%BD%BF%E8%BD%AE%E6%9C%BA%E6%9E%84/10448252?fr=ge_ala, December 5, 2024.

- Chen, Z.Y.; Guo, Z.H.; Fang, B.; Gao, L.Y.; Su, G.S.; Liu, B.Q. Simulation study of the punching forming process and die wear of spur gears. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2024, 131(9), 4635–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero, J.I.; Sánchez, M.B.; Pleguezuelos, M. Analytical model of meshing stiffness, load sharing, and transmission error for internal spur gears with profile modification. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2024, 197, 105650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lei, Y.G.; Liu, H.; Yang, B.; Li, X.; Li, N.P. Rigid-flexible coupled modeling of compound multistage gear system considering flexibility of shaft and gear elastic deformation. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, 200, 110632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Zhang, X.F.; Zhou, J.X.; Wang, H.W.; Liu, Y. Analysis of dynamic load characteristics of high coincidence spur gears. Combination Machine Tool and Automation Processing Technology 2024, (09), 76-80+85.

- Achari, A.S.; Daivagna, U.M.; Banakar, P.; Algur, V. Effect of Addendum Modification on Helix Angle in Involute Helical Gear Pairs with Long-Short Addendum System Focusing on Specific Sliding. Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series C 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, S.; Marimuthu, P.; Dinesh Babu, P.; Venkatraman, R. Contact fatigue life estimation for asymmetric helical gear drives. International Journal of Fatigue 2022, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Gao, P.; Hu, X.L.; Sun, W.; Zeng, J. Effects of dynamic transmission errors and vibration stability in helical gears. Journal of mechanical science and technology 2014, 28, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, H.Z.; Sascha, W.; Konrad, W. Face-gear drive: Meshing efficiency assessment. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2022, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Wu, X.Y. Calculation and analysis of contact ratio of helical curve-face gear pair. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2017, 39, 2269–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschippang, H.A.; Weikert, S.; Wegener, K. Face-gear drive: Meshing efficiency assessment. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2022, 171, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.; Barman, A.G. Design optimization of worm gear drive with reduced power loss. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing 2019, 635(1), 012015.

- Deng, X.Q.; Wang, S.S.; Hammi, Y.; Qian, L.M.; Liu, Y.C. A combined experimental and computational study of lubrication mechanism of high precision reducer adopting a worm gear drive with complicated space surface contact. Tribology International 2020, 146, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, F.L.; Nava, A.; Fan, Q. Fuentes, A. New geometry of face worm gear drives with conical and cylindrical worms: generation, simulation of meshing, and stress analysis. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2002, 191, 3035–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.X.; Zhao, Y.P.; Cui, J.; Mu, S.B.; Li, G.F.; Chen, X.Y. Kinematics of point-conjugate tooth surface couple and its application in mixed mismatched conical worm drive. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2022, 167, 104528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, M.; Redkar, S. Optimal DMD Koopman Data-Driven Control of a Worm Robot. Biomimetics 2024, 9(11), 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahám, R.; Majdan, R.; Kollárová, K.; Tkáč, Z.; Matejková, E.; Masarovičová, S.; Drlička, R. Spike Device with Worm Gear Unit for Driving Wheels to Improve the Traction Performance of Compact Tractors on Grass Plots. Agriculture 2024, 14(4), 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chen, Y.H.; Lu, B.B.; Luo, W.J.; Chen, B.K. Study on the vibration characteristics of worm helical gear drive. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2024, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.C.; Nie, J.H. Dual lead linear contact biased worm driveⅠ- principle analysis. Journal of Beijing Institute of Technology 2011, 37(02), 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, S.B.; Zhao, Y.P.; Cui, J.; Meng, Q.X.; Li, H.F. Meshing theory of face worm gear drive with hardened cylindrical worm. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2023, 185, 105323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.H.; Hua, L.; Han, X.H.; Zheng, F.Y. Design and hot forging manufacturing of non-circular spur bevel gear. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2017, 133129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.W.; Chen, J.Y.; Han, Z.Y. Tooth surface mismatch design of cycloidal bevel gear based on two directions modification of pinion cutter. In Journal of Advanced Mechanical Design, Systems, and Manufacturing 2024,18(2), JAMDSM0024-JAMDSM0024.

- Gonzalez-Perez, I.; Fuentes-Aznar, A. An exact system of generation for face-hobbed hypoid gears: Application to high reduction hypoid gear drives. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2023, 179, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, J.J.; Li B, Zhao, J. W.; Wang, B.; Xin, W.; Cheng, B. Lapping adjustment method for actual surface of hypoid gears. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2023, 45(2), 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.Q.; Zong, L.J.; Lam, T.L. DISG: driving-integrated spherical gear enables singularity-free full-range joint motion. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2023, 39(6), 4464–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Oiwa, T.; Kotani, A. Proposal for a Multiple-DOF Spherical Gear and Investigation of Backlash and Transmitted Efficiency Between Gears. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 2021, 22, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.Y.; Hua, L.; Han, X.H.; Li, B.; Chen, D.F. Synthesis of indexing mechanisms with non-circular gears. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2016, 105, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundo, D. Geometric design of a planetary gear train with non-circular gears. Mechanism and machine theory 2006, 41(4), 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.H.; Yu, J.P.; Tong, J.H.; Ye, B.L.; Zheng, S.Y. Design of a Conjugated Concave convex Non circular Gear Mechanism. China Mechanical Engineering 2016, 27 (16), 2155-2159+2165.

- Chen, Y.Z.; Xiao, X.P.; Zhang, D.P.; Xiao, H.F.; Lyu, Y.L. Design method of a novel variable speed ratio line gear mechanism. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2021, 235(6),1071-1084.

- Ding, J.; Liu, L.W.; Wei, Y.T.; Deng, A.P. Improved design method for line gear pair based on screw theory. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology 2022, 36(4), 1867–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ding, H.F.; Zeng, M. Nonrelative sliding gear mechanism based on function-oriented design of meshing line functions for parallel axes transmission. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2018, 10(9), 1687814018796327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Kim, C.H.; Yun, P.H.; Kwon, S.M. Dual cycloid gear mechanism for automobile safety pretensioners. Journal of Central South University 2012, 19, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Chan, C.T. Development of magnetic gear mechanisms. Transactions of the Canadian Society for Mechanical Engineering 2017, 41(5), 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Fang, Y.; Pfister, P.D. A novel single-PM-array magnetic gear with HTS bulks. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2017, 27(4), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.B.; Gong, J.; Huang, Z.X.; Ben, T.; Huang, Y.H. A new structure for the magnetic gear. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 75550–75555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.M. A superconducting magnetic gear. Superconductor Science and Technology 2016, 29(5), 054008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Yu, H.T.; Hu, M.Q. Study of an axial-flux modulated superconducting magnetic gear. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2018, 29(2), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, R.C.; Wu, F.; Luo, J.; Pu, H.Y.; Chu, F.L.; Han, Q.K. Rotating single-electrode triboelectric V-belts with skidding and wear monitoring capabilities. Tribology International 2024, 193, 109404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, V.U.; Weiss, L.; Zogg, M.; Wegener, K. Analytical flat belt drive model considering bilinear elastic behaviour with residual strains. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2023, 190, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Shangguan, W.B.; Deng, J.X.; Jing, X.J. Modeling and dynamic analysis of accessory drive systems with integrated starter generator for micro-hybrid vehicles. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering 2019, 233(5), 1162-1177.

- Long, S.B.; Zhao, X.Z.; Shangguan, W.B.; Zhu, W.D. Modeling and validation of dynamic performances of timing belt driving systems. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2020, 144, 106910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.H.; Gao, S.; Feng, J.G.; Kong, Y.; Han, Q.K.; Chu, F.L. Intelligent triboelectric V-belts with condition monitoring capability. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2024, 209, 111132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.N.; Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.C.; Xia, X.D.; He, X.J. Design, modeling and experiment of a novel synchronous belt drive with noncircular pulleys. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology. Transactions of Mechanical Engineering 2020, 44, 533–542. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, R.; Noda, N.A.; Sano, Y.; Song, J.; Minami, T.; Birou, Y.; Miyagi, A.; Huang, Y.S. Fatigue strength analysis and fatigue damage evaluation of roller chain. Metals 2018, 8(10), 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaspeze, G.; Guilbert, B.; Manin, L.; Ville, F. Quasi-Static Chain Drive Model for Efficiency Calculation-Application to Track Cycling. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2024, 2024. 203, 105780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.J.; Chi, C.Z.; Wang, Y.Z.; Lin, P.; Zhao, R.H.; Liang, W. 3D FEM simulation of flow velocity field for 5052 aluminum alloy multi-row sprocket in cold semi-precision forging process. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2015, 25(3), 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.X.; Feng, Z.M.; Wang, X.G. Oil injection lubrication analysis of a silent chain drive system. Advances in Engineering Software 2022, 172, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.B.; Chen, L.X.; Ge, PY.; Chen, X.M.; Niu, J.X. Design and optimization of dual-phase chain transmission system based on single tooth chain plate. Mechanics Based Design of Structures and Machines 2023, 51(2), 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krithikaa, D.; Chandramohan, P.; Suresh, G.; Rathinasabapathi, G.; Madheswaran, D.K.; Mohammed Faisal, A. A study on: Design and fabrication of E-glass fiber reinforced IPN composite chain plates for low duty chain drives. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2024.

- Tiboni, M.; Amici, C.; Bussola, R. Cam Mechanisms Reverse Engineering Based on Evolutionary Algorithms. Electronics 2021, 10(24), 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miiller, M.; Hoffmann, M.; Hiising, M.; Corves, B. Using servo-drives to optimize the transmission angle of cam mechanisms. Mech. Mach. Theory 2019, 137, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidu.https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%87%B8%E8%BD%AE%E6%BB%9A%E5%AD%90/9971479?fr=ge_ala,(September 22, 2024).

- Yan, H.S.; Chen, H.H. Geometry design and machining of roller gear cams with cylindrical rollers. Mechanism and Machine Theory 1994, 29(6),803-812.

- Yousuf, L.S.; Marghitu, D.B. Analytic and numerical results of a disc cam bending with a roller follower. SN Applied Sciences 2020, 2, 2,1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.T.; Hu, Y. E. An integrally formed design for the rotational balancing of disk cams. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2021, 161, 104282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.T.; Hu, Y.E.; Chang W, C. An improved design for rotating balance of assembled type conjugate disk cams. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2022, 171, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, D.M.; Lin, B.J. Profile determination of planar and spatial cams with cylindrical roller-followers. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 1996, 210(6), 565-574.

- Kamali, S.H.; Miri, M.H.; Moallem, M.; Arzanpour, S. Cylindrical cam electromagnetic vibration damper utilizing negative shunt resistance. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2019, 25(2), 996-1004.

- Sakhaei, A.H.; Kaijima, S.; Lee, T.L.; Tan, Y.Y.; Dunn, M.L. Design and investigation of a multi-material compliant ratchet-like mechanism. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2018, 121, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, H.; Kang, H.; Chang, H. A rotary microgripper with locking function via a ratchet mechanism. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2015, 26(1), 015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P.H.; Dang, L.B.; Nguyen, D.T.; Nguyen, D.Q. A micro transmission system based on combination of micro elastic structures and ratchet mechanism. Microsystem Technologies 2017, 23, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, G.M. An investigation of compliant over-running ratchet and pawl clutches. Brigham Young University, America 2003.

- Bondaletov, V.P. Ratchet mechanisms for high-speed transmissions. Russian Engineering Research 2008, 28(9), 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizescu, C.I.; Baciu, D.E.; Rizescu, D. Study behaviour of ratchet mechanism manufactured with 3D printing technology. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing 2022, 1235(1), 012001.

- Khare, A.K.; Dave, R. K. Optimizing 4-bar crank-rocker mechanism. Mechanism and Machine Theory 1979, 14(5), 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, C.R. A complete classification of planar four-bar linkages. Mechanism and Machine Theory 1985, 20, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.E.; Baharom, M.B.; Aziz, A.R.A.; Zainal A, E.Z. Modelling of combustion characteristics of a single curved-cylinder spark-ignition crank-rocker engine. Energies 2019, 12(17), 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, D.E. Dynamic Design of Crank-Rocker SI Engine Mechanism. Journal of Vibration Engineering & Technologies 2022, 10(7), 2853-2875.

- Sapietová, A.; Štalmach, O.; Sapieta, M. Synthesis and sensitivity analysis of the crank-rocker mechanism. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing 2020, 776(1), 012060.

- Conn, A.T.; Burgess, S.C.; Ling, C.S. Design of a parallel crank-rocker flapping mechanism for insect-inspired micro air vehicles. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2007, 221(10), 1211-1222.

- Mutlu, H. Design of the crank–rocker mechanism for various design cases based on the closed-form solution. Sādhanā 2021, 46(1),4.

- Joshi, R.; Arakeri, J. Long-distance sinusoidal actuation in self-propelling apparatus: a novel spiral spring-based crank rocker mechanism. Sādhanā 2024, 49(1), 16.

- Tuan, D.A. Application of the double crank mechanism in designing complex-stroke press. Journal of Military Science and Technology 2023, (FEE), (FEE),149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Y. Simulation and Optimization of Double crank 2K-H Wheel System Reversing Device for Pumping Unit. Master’s thesis. Yanshan University. Qinhuangdao City, Hebei Province, China. June 2022.

- Radaelli, G. Reverse-twisting of helicoidal shells to obtain neutrally stable linkage mechanisms. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2021, 202, 106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Q.; Chen, Y. A double spherical 6R linkage with spatial crank-rocker characteristics inspired by kirigami. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2020, 153, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalec, M.; Svoboda, P.; Křupka, I.; Hartl, M. A review of the design and optimization of large-scale hydrostatic bearing systems. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2021, 24(4), 936-958.

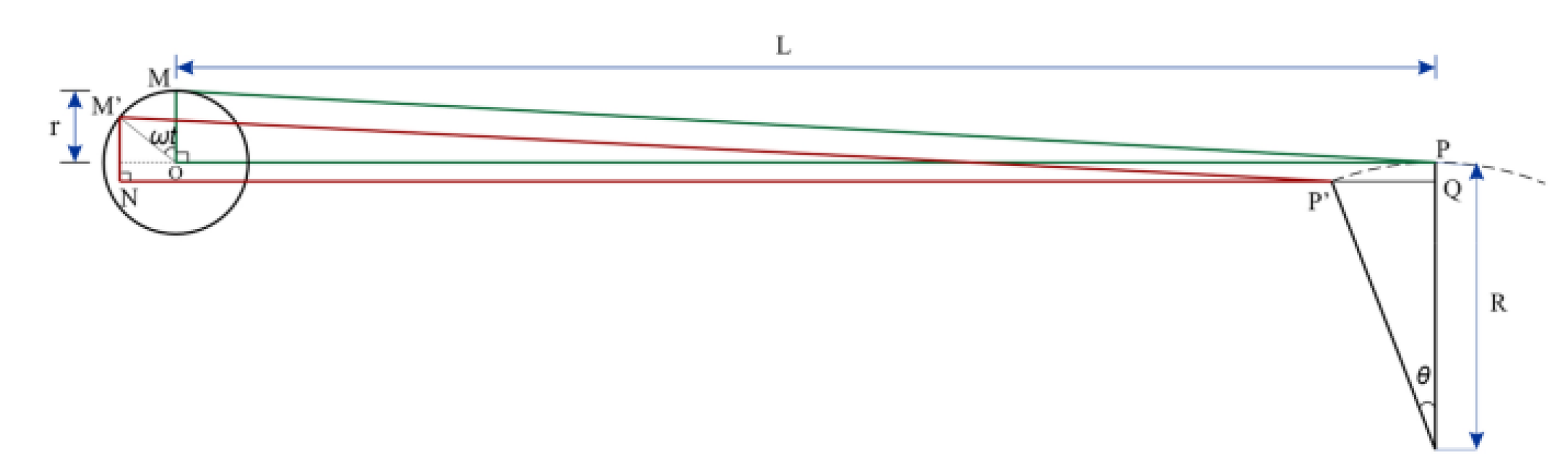

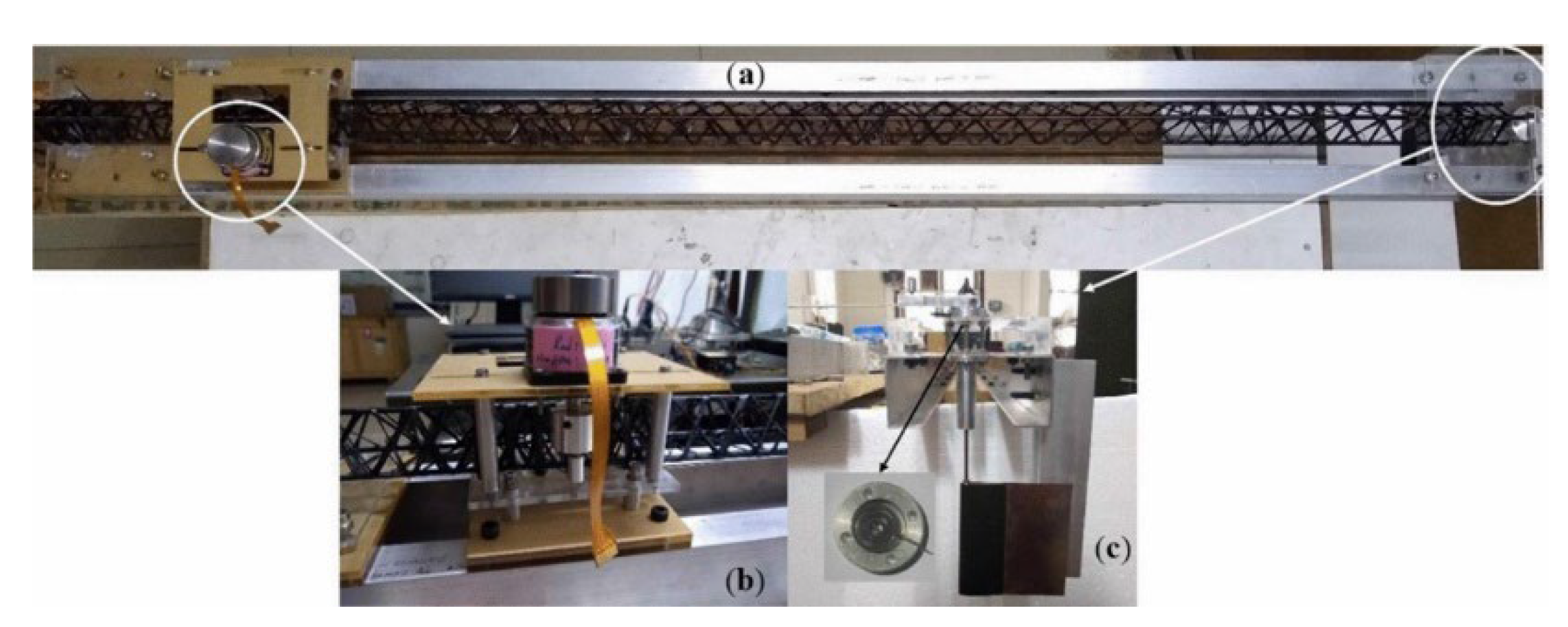

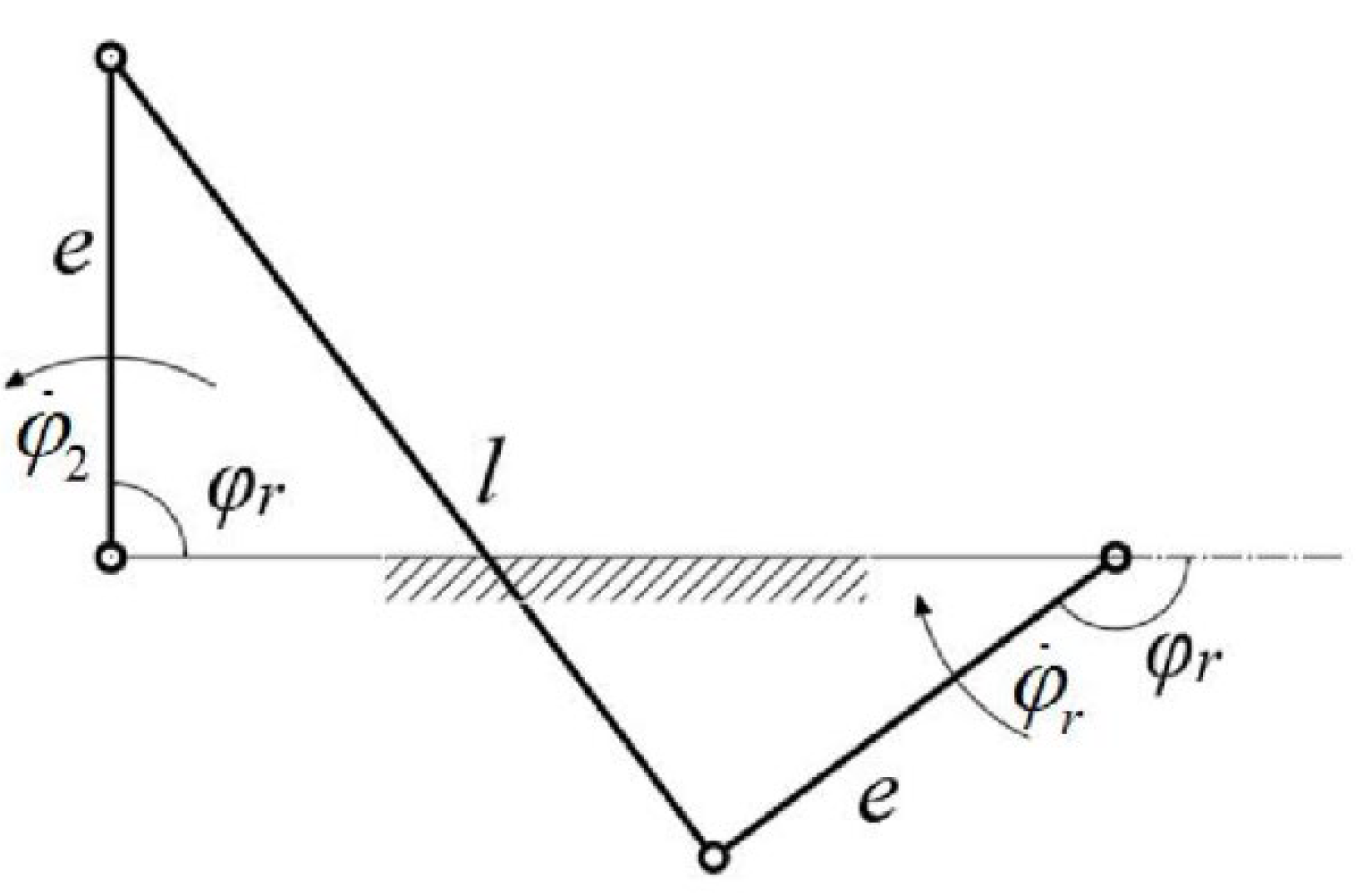

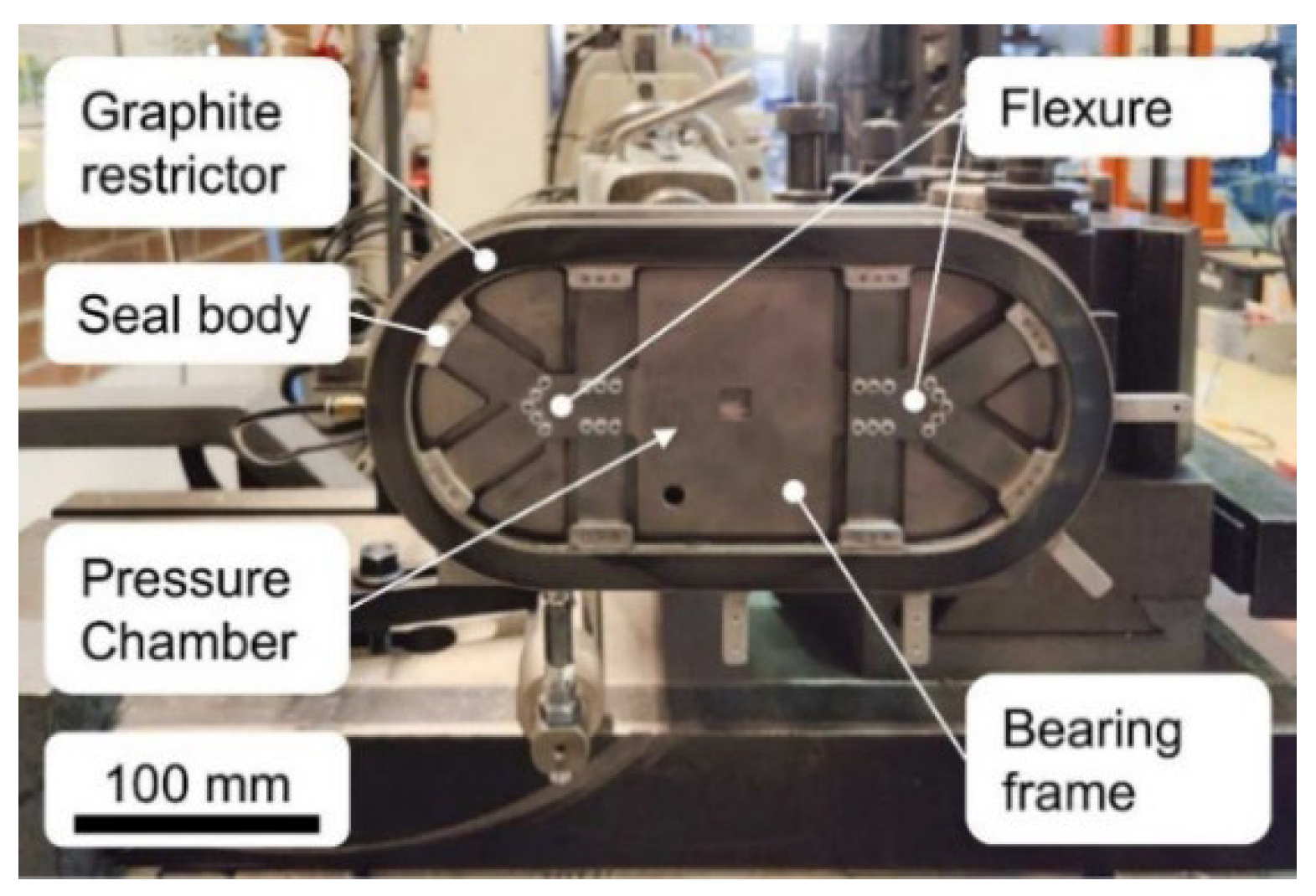

- Miettinen, M.; Vainio, V.; Theska, R.; Viitala, R. Aerostatically sealed chamber as a robust aerostatic bearing. Tribology International 2022, 173, 107614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laldingliana, J.; Debnath, S.; Biswas, P.K.; Das, U. Design and speed control of U-type 3-coil active magnetic bearing. Electrical Engineering 2024, 106(2), 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Lu, C.H.; Li, C.H. Current Status of Research on Hybrid Ceramic Ball Bearings. Machines 2024, 12(8), 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yan, K.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhu, Y.S.; Hong, J. Microscale simulation method for prediction of mechanical properties and composition design of multilayer graphene-reinforced ceramic bearings. Ceramics International 2021, 47(12), 17531–17539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Gao, L.W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.N.; Zhang, L.Q. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of ceramic bearing rotor system considering temperature variation fit clearance. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2024, 46(5), 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Wei, Y.J.; Kumar, A.; Ma, S.J.; Shao, M.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Y.H.; Xu, P.K. Dynamic analysis of full-ceramic bearing-rotor system under thermally induced loosening in aerospace applications. Engineering Failure Analysis 2024, 159, 108080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.Y.; Tsai, Y.H.; Hsiao, K.M. A new indexing motion program for optimum designs of Geneva mechanisms with curved slots. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2017, 231(21), 3974-3986.

- Pasika, V.; Nosko, P.; Nosko, O.; Bashta, O.; Heletiy, V.; Melnyk, V. A method to synthesise groove cam Geneva mechanisms with increased dwell period. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2024, 238(15), 7544-7555.

- Yang, Y.H.; Xie, R.; Wang, J.Y.; Tao, S.Y. Design of a novel coaxial cam-linkage indexing mechanism. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2022, 169, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douyin. https://v.douyin.com/iyC7S1tV/, September 6, 2024.

- Bilibili.https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1DFWxeGEXn/?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0&vd_source=a4b7c6e62117d66b6d9389ffbd501cca, August 21, 2024.

- Yang, Y.Q.; Chen, P.H.; Liu, Q. A wave energy harvester based on coaxial mechanical motion rectifier and variable inertia flywheel. Applied Energy 2021, 302, 117528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Qi, B.B.; Liu, Z.F.; Zhang, C.X.; Xue, D.Y. An accuracy degradation analysis of ball screw mechanism considering time-varying motion and loading working conditions. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2019, 134, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, C.X.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, T.; Shi, W.; Xue, D.Y. Kinematic modeling of a planetary roller screw mechanism considering runout errors and elastic deformation. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2023, 124(11), 4455–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.D.; Feng, X.Y.; He, Q.; Wang, Q.J.; Yu, H.W.; Liu, H.Y. Investigation on the thermal characteristics of double-driven hydrostatic lead screw micro-feed system. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 255, 123926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.X.; Peng, W.M.; Kong, W.H.; Luo, D.B.; Zhang, Z.T.; Li, L.F. An energy harvesting shock absorber for powering on-board electrical equipment in freight trains. Iscience 2023, 26(9).

- Zhu, L.X.; Wu, Q.Y.; Li, W.; Wu, W.M.; Koh, C.H.; Blaabjerg, F. A novel consequent-pole magnetic lead screw and its 3-D analytical model with experimental verification for wave energy conversion. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2023, 39(2), 1202–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.S.; Kong, L.J.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Wu, X.P.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.T.; Yan, J.Y. An electromagnetic vibration energy harvesting system based on series coupling input mechanism for freight railroads. Applied Energy 2024, 353, 122047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.X.; Zhu, Q.W.; He, J.Y.; Zhao, L.C.; Wei, K.X.; Zhang, W.M.; Du, R.H.; Liu, S. Energy harvesting floor using sustained-release regulation mechanism for self-powered traffic management. Applied Energy 2024, 353: 122082.

- He, J.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.C.; Gao, F.; Wu, Y.J.; Wang, Z.C. Kinematic design of a serial-parallel hybrid finger mechanism actuated by twisted-and-coiled polymer. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2020, 152, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, B.; Wang, L. Design, analysis, and test of a novel 2-DOF spherical motion mechanism. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 53561–53574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.T.; Wang, P.; Li, B.W.; Yang, Q.J. Analysis and compensation control of passive rotation on a 6-DOF electrically driven Stewart platform. Mechanical Sciences 2021, 12(2), 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.X.; Kim, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Lu, Q.; Peng, D.L. Robotic tensegrity structure with a mechanism mimicking human shoulder motion. Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics 2022, 14(2), 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, B.; Chander, S.A.; Vasamsetti, S. Hybrid offset slider crank mechanism for anthropomorphic flexion in prosthetic hands. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2023, 20(1), 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.Y.; Li, Y.F.; Zhang, J.W.; Zhang, D.; Yu, H.L. Design and optimization of a novel sagittal-plane knee exoskeleton with remote-center-of-motion mechanism. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2024, 194, 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.B.; Zhou, M.; Sun, H.; Wei, Z.X.; Dong, H.R.; Xu, T.B.; Yin, D.Q. Mechanism Analysis and Optimization Design of Exoskeleton Robot with Non-Circular Gear–Pentabar Mechanism. Machines 2024, 12(5), 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Lee, S.; Seo, T.W.; Kim, J.W. A new non-servo motor type automatic tool changing mechanism based on rotational transmission with dual four-bar linkages. Meccanica 2018, 53, 2447–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, G.N.; Weng, M.H.; Liu, J.H.; Zhou, J. Lu, B. Parameter Optimization of Large-Size High-Speed Cam-Linkage Mechanism for Kinematic Performance. In Actuators. MDPI 2022, 12(1), 2.

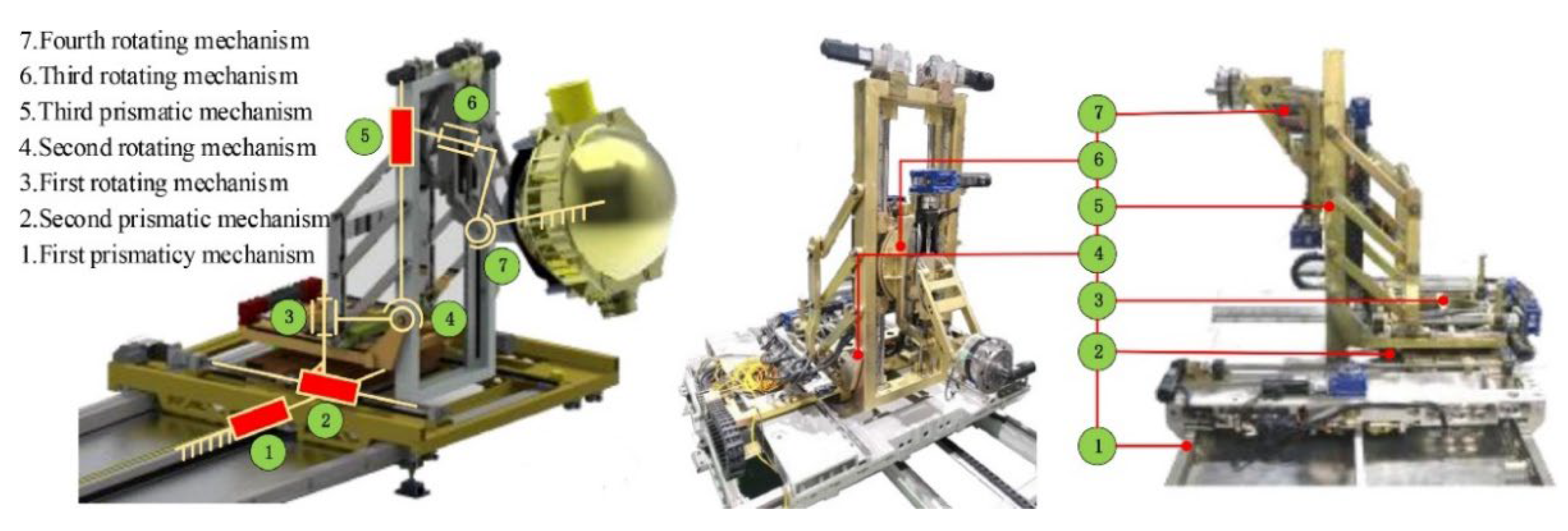

- Liu, Y.; Yi, W.M.; Feng, Z.Q.; Yao, J.T.; Zhao, Y.S. Design and motion planning of a 7-DOF assembly robot with heavy load in spacecraft module. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2024, 86, 102645.

- Tong, Z.P.; Yu, G.H.; Zhao, X.H.; Liu, P.F.; Ye, B.L. Design of vegetable pot seedling pick-up mechanism with planetary gear train. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2020, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.L.; Li, L.H.; Xu, C.L.; Li, E.Q.; Wang, Y.J. Optimized design and experiment of a fully automated potted cotton seedling transplanting mechanism. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2020, 13(4), 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhang, B.; Suo, H.B.; Lin, C.; Ji, J.T.; Xie, X.L. Design and Mechanical Analysis of a Cam-Linked Planetary Gear System Seedling Picking Mechanism. Agriculture 2023, 13(4), 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Xiao, Q.S.; Geng, J.Y. Research on a water-treading bionic propeller with variable pitch. Ocean Engineering 2022, 266, 112989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Emami, M.R.; Lei, Y. Model-based health monitoring of rotate-vector reducers in robot manipulators. Mechatronics 2024, 99, 103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojevic, M.; Marjanovic, N.; Djordjevic, Z.; Stojanovic, B.; Disic, A. A new design of a two-stage cycloidal speed reducer. Journal of Mechanical Design 2011,133 / 085001-1.

- Xu, L.X.; Zhong, J.L.; Li, Y.; Chang, L. Design and dynamic transmission error analysis of a new type of cycloidal-pin reducer with a rotatable output-pin mechanism. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2023, 181, 105218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.X.; Tang, P.; Zheng, J.; Dong, D.B.; Chen, X.H.; Bai, L.; Ge, W.J. Optimal design of a nonlinear series elastic actuator for the prosthetic knee joint based on the conjugate cylindrical cam. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 140846–140859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. D, Liu, B.H.; Yin, T.H.; Xiang, Y.H. Zhou, H.F.; Qu, S.X. Bistable rotating mechanism based on dielectric elastomer actuator. Smart Materials and Structures 2019, 29(1), 015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.X.; Cao, D.X.; Qu, R.H.; Zhang, G.Y.; Zhang, S. A novel design of torsion spring-connected nonlinear stiffness actuator based on cam mechanism. Journal of Mechanical Design 2022, 144(8), 083303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Cheng, G.G.; Kong, M.X.; Li, R.F. Design, Modeling, and Control of a Compact and Reconfigurable Variable Stiffness Actuator Using Disc Spring. Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics 2024, 16, 091006–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanık, Ç.M.; Parlaktaş, V.; Tanık, E.; Kadıoğlu, S. Steel compliant Cardan universal joint. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2015, 92, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Hao, G.B. Design and nonlinear spatial analysis of compliant anti-buckling universal joints. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2022, 219, 107111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakuş, R.; Tanık, Ç.M. Compliant universal joint with preformed flexible segments. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology 2022, 36(11), 5639–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douyin. https://v.douyin.com/i5m23ocP/,September 8, 2024.

- Douyin. https://v.douyin.com/i5m65JUJ/, September 8, 2024.

- Douyin. https://v.douyin.com/iDAPPXDw/, September 8, 2024.

- Douyin. https://v.douyin.com/iy9nJmFc/, January 14, 2025.

- Baidu. https://blog.csdn.net/qq_41931610/article/details/140814387, October 5, 2024.

- Chow, C.C.T.; Ainslie, M.D.; Chau, K.T. High temperature superconducting rotating electrical machines: An overview. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 1124–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terao, Y.; Seta, A.; Ohsaki, H.; Oyori, H.; Morioka, N. Lightweight design of fully superconducting motors for electrical aircraft propulsion systems. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2019, 29(5), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.W.; Weng, F.J. Li, J.W.; Souc, J.; Gomory, F.; Zou, S.N.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, W.J. No-insulation high-temperature superconductor winding technique for electrical aircraft propulsion. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2020, 6(4), 1613–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrey, D.; Parizh, M.; Bray, J.; Stautner, W.; Tapadia, N.; Xu, M.F.; Wu, A.B.; Zierer, J. Superconducting synchronous motors for electric ship propulsion. IEEE Transactions on applied superconductivity 2020, 30(4), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipenko, M.; Khn , L.; Gleixner ,T.; Thummet, M.; Lessmann , M.; Mller , D.; Bhm , M.; Schrter , A.; Hse, K.; Grundmann, J.; Wilke, M.; Frank , M.; Hasselt, P.V.; Richter , J.; Herranz-Garcia, M.; Weidermann, C.; Spangolo, A.; Klpzig , M.; Grppel , P.; Moldenhauer,S. Concept design of a high power superconducting generator for future hybrid-electric aircraft. Superconductor Science and Technology 2020, 33(5), 054002.

- Morita,G.;Nakamura,T.;Muta,I. Theoretical analysis of a YBCO squirrel-cage type induction motor based on an equivalentcircuit. Superconductor Science and Technology 2006, 19(6), 473.

- Nakamura, T.;Dong,T.H.; Matsuura, J.; Kiss, T.; Higashikawa, K.; Sato, S.; Zhang, P.H. Experimental and theoretical study on power generation characteristics of 1 kW class fully high temperature superconducting induction/synchronous generator using a stator winding with a bending diameter of 20 mm. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2022, 32(6), 1-5.

- Keysan, O.; Mueller, M. A modular and cost-effective superconducting generator design for offshore wind turbines. Superconductor Science and Technology 2015, 28(3), 034004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, K.L.; Verzhbitsky, L.G.; Kozub, S.S.; Penkin, V.T.; Larionov, A.E.; Modestov, K.A.; Ivanov, N.S.; Tulinova, E.E.; Dubensky, A.A. Brushless superconducting synchronous generator with claw-shaped poles and permanent magnets. IEEE Transactions on applied superconductivity 2016, 26(3), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kails, K.; Li, Q.; Mueller, M. A modular and cost-effective high-temperature superconducting generator for large direct-drive wind turbines. IET Renewable Power Generation 2021, 15(9), 2022–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuger, R.; Matsekh, A.; Kells, J.; Sercombe, D.B.T.; Guina, A. A superconducting homopolar motor and generator—new approaches. Superconductor Science and Technology 2016, 29(3), 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsi S, Hamilton K, Buckley R G, et al. Superconducting AC homopolar machines for high-speed applications. Energies 2018, 12(1), 86.

- Glowacki, J.; Sun, Y.; Storey, J.G.; Badcock, R. Temperature distribution in the field coil of a 500-kW HTS AC homopolar motor. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2021, 32(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colle, A.; Lubin, T.; Ayat, S.; Gosselin, O.; Leveque, J. Test of a flux modulation superconducting machine for aircraft. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing 2020, 1590(1), 012052.

- Dorget, R.; Ayat, S.; Biaujaud, R.; Tanchon, J.; Lacapere, J.; Lubin, T.; Lvque, J. Superconducting flux modulation machines for aircraft propulsion. Emissions Free Air Transport Through Superconductivity (EFATS) 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dorget, R.; Ayat, S.; Biaujaud, R.; Tanchon, J.; Lacapere, J.; Lubin, T.; Lvque, J. Design of a 500 kW partially superconducting flux modulation machine for aircraft propulsion. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing 2021, 1975(1), 012033.

- Dias, F.J.M.; Santos, B.M.O.; Sotelo, G.G.; Polasek, A.; Andrade, R.D. Development of a superconducting machine with stacks of second generation HTS tapes. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2019, 29(5), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.M.O.; Dias, F.J.M.; Sass, F.; Sotelo, G.G.; Polasek, A.; Andrade, R.D. Simulation of superconducting machine with stacks of coated conductors using hybrid AH formulation. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2020, 30(6), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, K.; Ivanov, N.; Zhuravlev, S.; Nekrasova, J.; Rusanov, D.; Kuznetsov, G. Development and testing of 10 kW fully HTS generator. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing 2020, 1559(1), 012137.

- Kovalev, K.; Ivanov, N.; Zhuravlev, S.; Rusanov, D.; Kuznetsov, G.; Podguzov, V. Calculation, design and test results of 3 kW fully HTS electric machine. Physica C: Superconductivity and its Applications 2021, 587, 1353892.

- Sasa, H.; Iwakuma, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Sato, S.; Sasayama, T.; Yoshida, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Miura, S.; Kawagoe, A.; Izumi, T.; Tomioka, A.; Konno, M.; Sasamori, Y.; Honda, H.; Hase, Y.; Syutoh, M.; Lee, S.; Hasuo, S.; Nakamura, M.; Hasegawa, T; Aoki,Y; Umeno, T. Experimental evaluation of 1 kW-class prototype REBCO fully superconducting synchronous motor cooled by subcooled liquid nitrogen for E-aircraft. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2021, 31(5), 1-6.

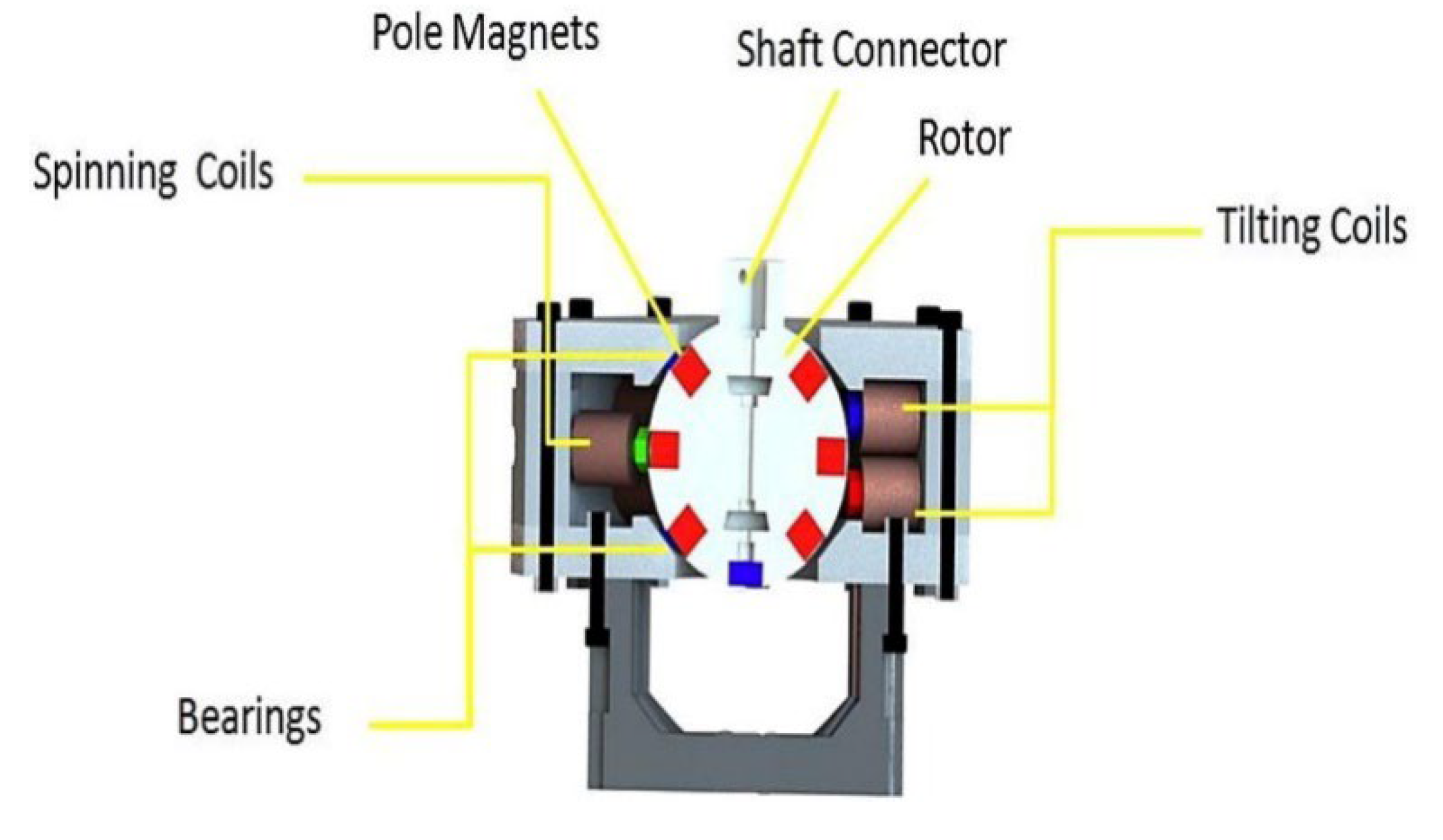

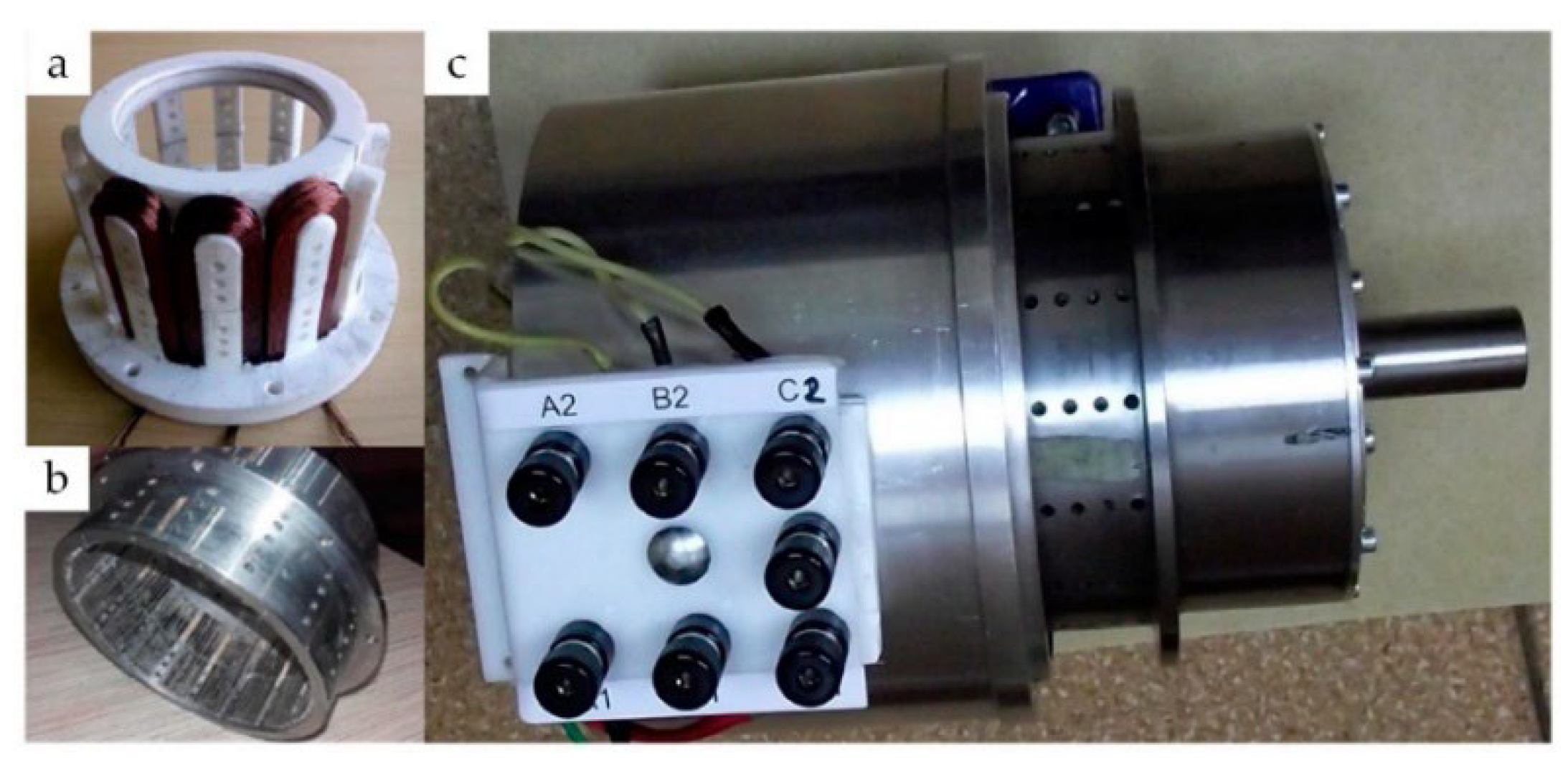

- Öğülmüş, A.S.; Tınkır, M. Development and performance analysis of novel design 3-DOF non-integrated runner permanent magnet spherical motor. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2023, 40, 101380.

- Sun, J.J.; XING, G.; Zhou, X.X.; Sun, H.X. Static magnetic field analysis of hollow-cup motor model and bow-shaped permanent magnet design. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 2022, 35(9), 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.J.; Ren, J.Y.; Sun, H.X. A Novel Design of an Inner Rotor for Optimizing the Air-Gap Magnetic Field of Hollow-Cup Motors. Machines 2022, 10(5), 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, Z.P.; Song, P.F.; Wang, L.M.; Liu, X.K. Sinusoidal Rotor Core Shape for Low Torque Ripple in Hollow-Cup Machines. Energies 2024, 17(13), 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelag, W.; Jedryczka, C.; Baranski, M.; Kurzawa, M. Design, Analysis and Experimental Verification of a Coreless Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Energies 2024, 17(7), 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Jiang, M.; Yang, F.F.; Rui, X.T. Modeling of a hexapod piezo-actuated positioning platform. Multibody System Dynamics 2024, 61(1), 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Xu, T.B. A Comprehensive Review of Piezoelectric Ultrasonic Motors: Classifications, Characterization, Fabrication, Applications, and Future Challenges. Micromachines 2024, 15(9), 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhao, L.L.; Yu, S.M.; et al. A novel rotary ultrasonic motor using the longitudinal vibration mode. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 135650–135655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.H.; Chen, S.J.; Huang, H.Y.; Qin, L.C.; Liu, T.F. Self-floating and self-rotating non-contact ultrasonic motor with single active vibrator. Tribology International 2023, 180, 108217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.S.; Zhang, Y.F.; Chen, X.Z.; Wang, Q.; Huang, Q.X. Development of a novel resonant piezoelectric motor using parallel moving gears mechanism. Mechatronics 2024, 97, 103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, M.X.; Yu, H.P.L; Liu, Y.X.; Deng, J.; Zhang, S.J.; Li, K. A precise rotary piezoelectric actuator based on the spatial screw compliant mechanism. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2022, 28(1), 223-232.

- Wang, F.; Hong, J.Y.; Xu, B.; Fiebig, W.J. Control design of a hydraulic cooling fan drive for off-road vehicle diesel engine with a power split hydraulic transmission. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2021, 27(5), 3717-3729.

- Zhu, D.M.; Fu, Y.L.; Han, X.; Li, Z.F. Design and experimental verification on characteristics of electro-hydraulic pump. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2020, 144, 106771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Liu, Z.Q.; Quan, L. Characterisation analysis of a new energy regenerative electro-hydraulic hybrid rotary system. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 25119–25128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, H.N.; Zhang, X.J.; Xu, Y.J.; Chen, H.S. Research progress on pneumatic catapult systems. Acta Aeronautica et Astronautica Sinica 2024, 45(22).

- Nuchkrua, T.; Leephakpreeda, T. Novel compliant control of a pneumatic artificial muscle driven by hydrogen pressure under a varying environment. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2021, 69(7), 7120–7129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.D.; Shi, H.Y.; Pinto, T.; Tan, X.B. A novel pneumatic soft snake robot using traveling-wave locomotion in constrained environments. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2020, 5(2), 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriy, O.; Vadim, D. Oscillatory Step Rotary Pneumatic Drives in Gas Transmission Systems. Procedia Engineering 2014, 69, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kang, S.; Zhao, Y.J.; Qi, Y.Y.; Zhong, S.Y.; Yang, Y. Multimode small-size pneumatic motors based on rigid-flexible coupling structure. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 2024, 3890–3900.

- Stoll, J.T.; Schanz, K.; Pott, A. A compliant and precise pneumatic rotary drive using pneumatic artificial muscles in a swash plate design. In 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE 2019, 3088-3094.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).