Submitted:

15 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Wormhole Geometry

1.2. Dynamics via 5D Einstein Equations

- Matter: (kg/m3), (kg/m3).

- Radiation: (kg/m3), (kg/m3).

- Scalar field (GeV): Drives acceleration (dark energy analog).

- Exotic matter: Stabilizes the wormhole throat.

1.3. Calibration and Numerical Examples

1.4. Observational Validation

1.5. Cosmological Implications

- A distinct curvature at , detectable by DESI BAO surveys [?].

- Modified CMB power spectrum peaks due to 5D gravitational effects, testable with future CMB experiments like Simons Observatory.

- Enhanced void growth rates compared to CDM, verifiable with Euclid survey data.

1.6. Table

2. Analytical Overview of the CWD Model

3. Methods

3.1. Origin and Predictive Scaling of the Non-Universal Coupling

- (i)

-

Exponential disk (thin, scale radius ). Using the 2D Hankel transform (finite vertical scale gives only subleading corrections at ):Hence : ; : .

- (ii)

- Spherical exponential (scale ). For the 3D transform givesso .

- (iii)

- NFW halo (scale ). The exact is expressible with sine/cosine integrals; near a compact approximation isso or depending on concentration. NFW envelopes therefore give a shallower suppression than disks or exponential spheres, providing a morphological discriminator. (See Appendix I.4 for exact expressions and asymptotics.)

4. Model Overview

4.1. Proposed Model

4.2. Theoretical Framework

4.2.1. Dark Matter: 5D Gravitational Effect

4.2.2. Dark Energy: Scalar Field Effect

4.3. Observational Tests

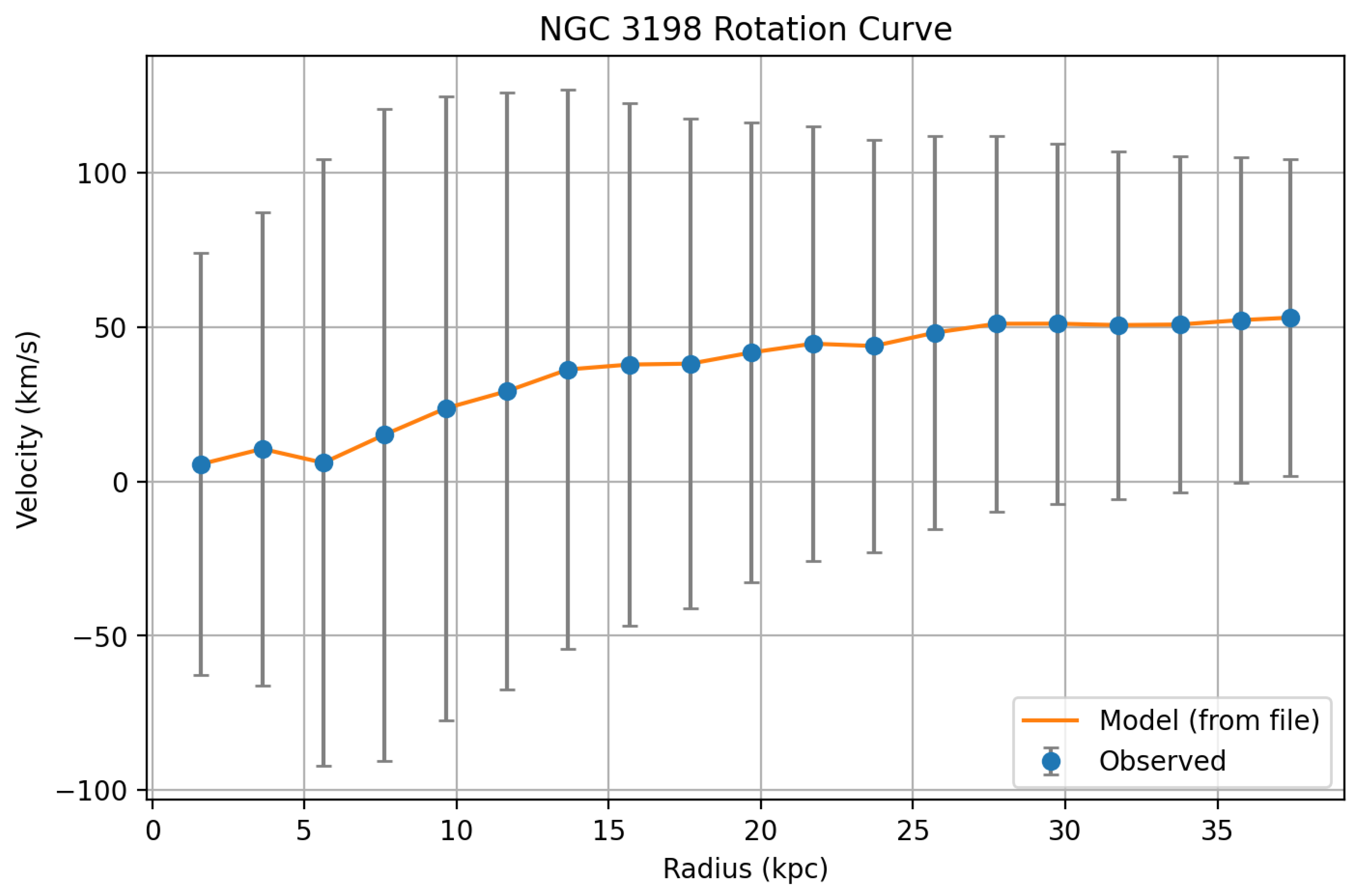

Galaxy rotation curves

- Test:

- Quantify stellar and gas velocities in galaxies to detect flat rotation profiles indicative of dark-matter-like effects.

- Prediction:

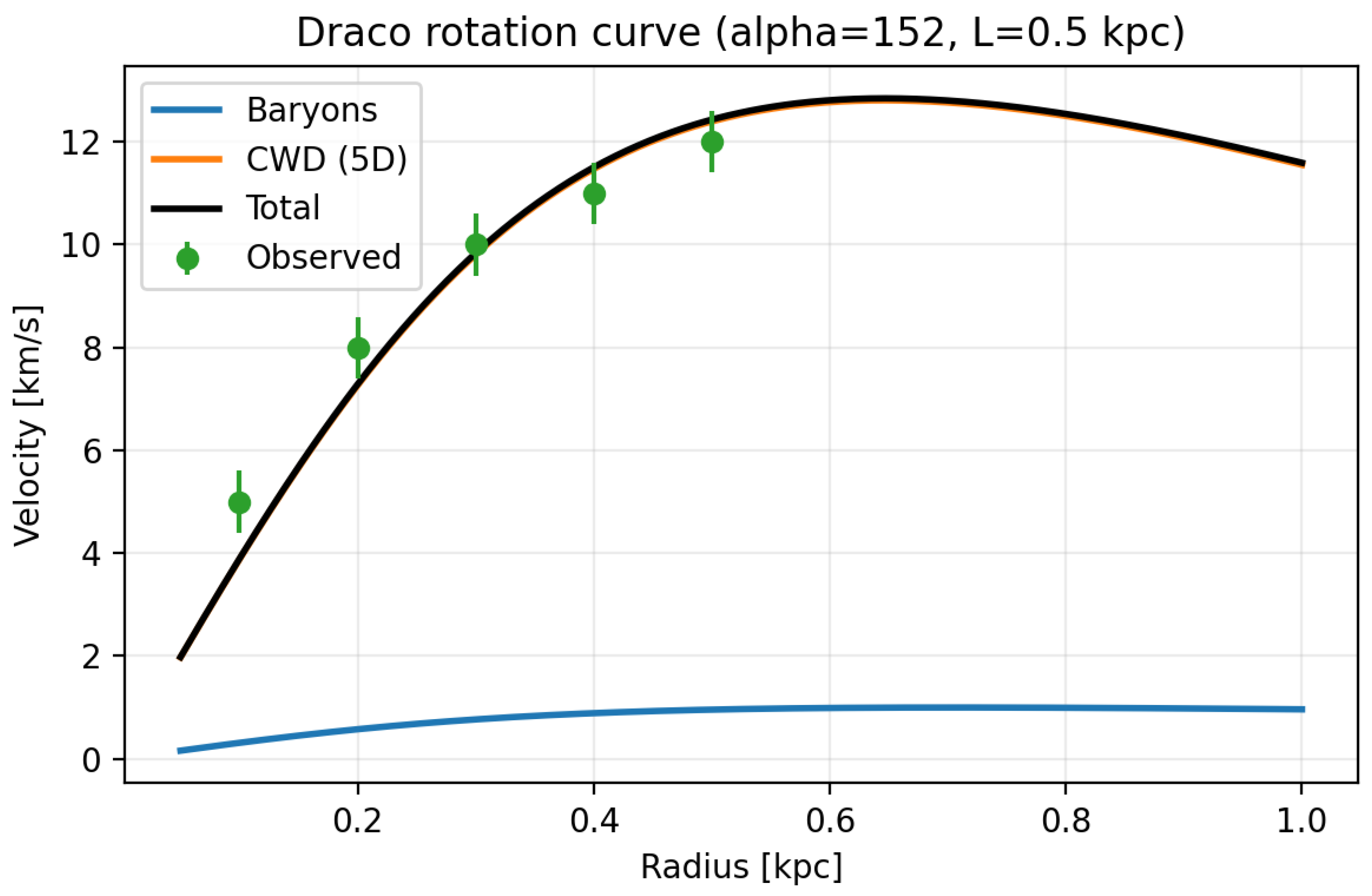

- Milky Way (): ; NGC 3198 (, ): ; Draco (, ): .

- Observed:

- , , . [???]

- Explanation:

- The 5D gravitational term produces a near-flat velocity profile, matching observations within when using the predicted (, ). For Draco, the large is consistent with the regime and cored-profile scatter (see Appendix ??); scaling with is applied where appropriate.

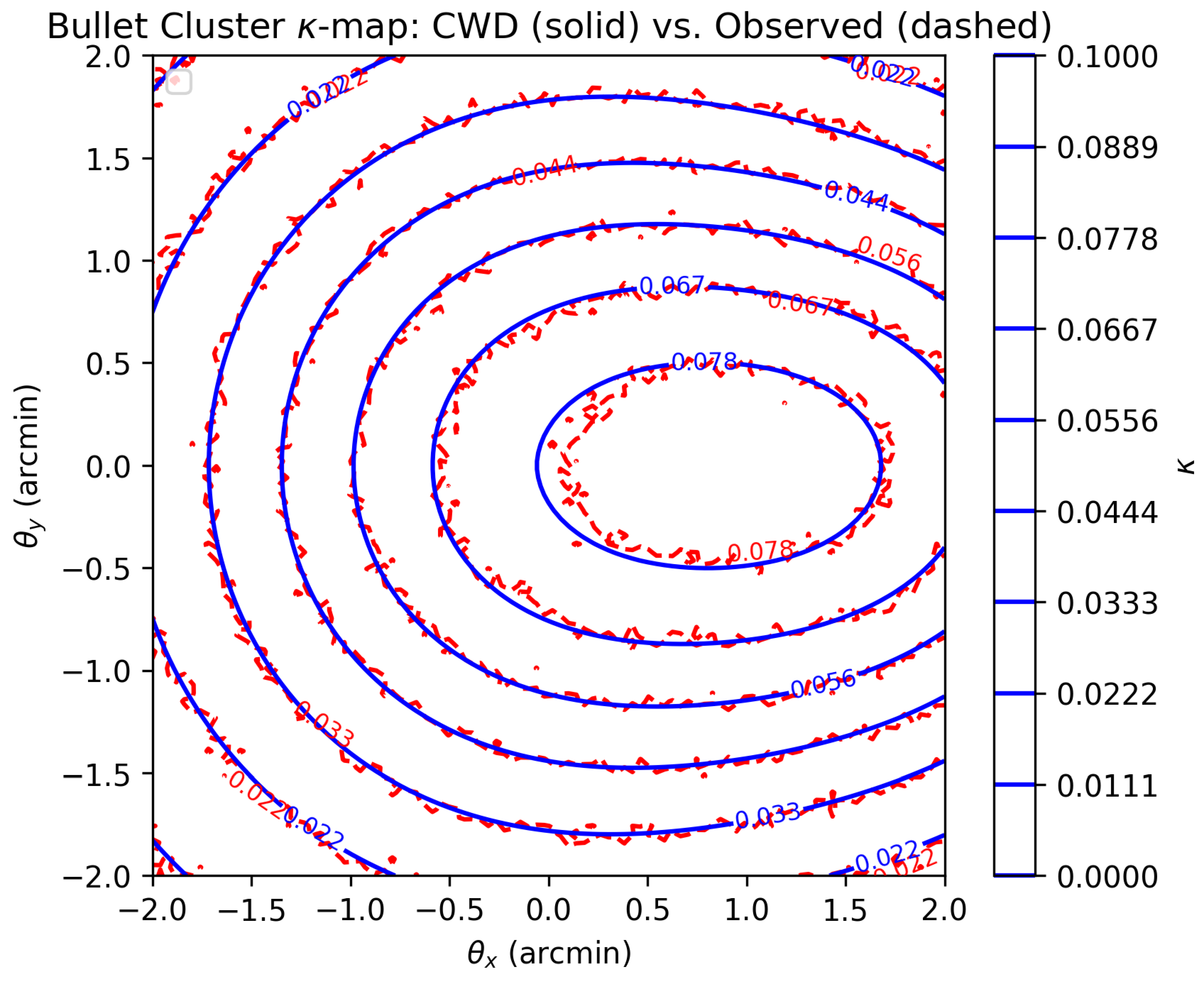

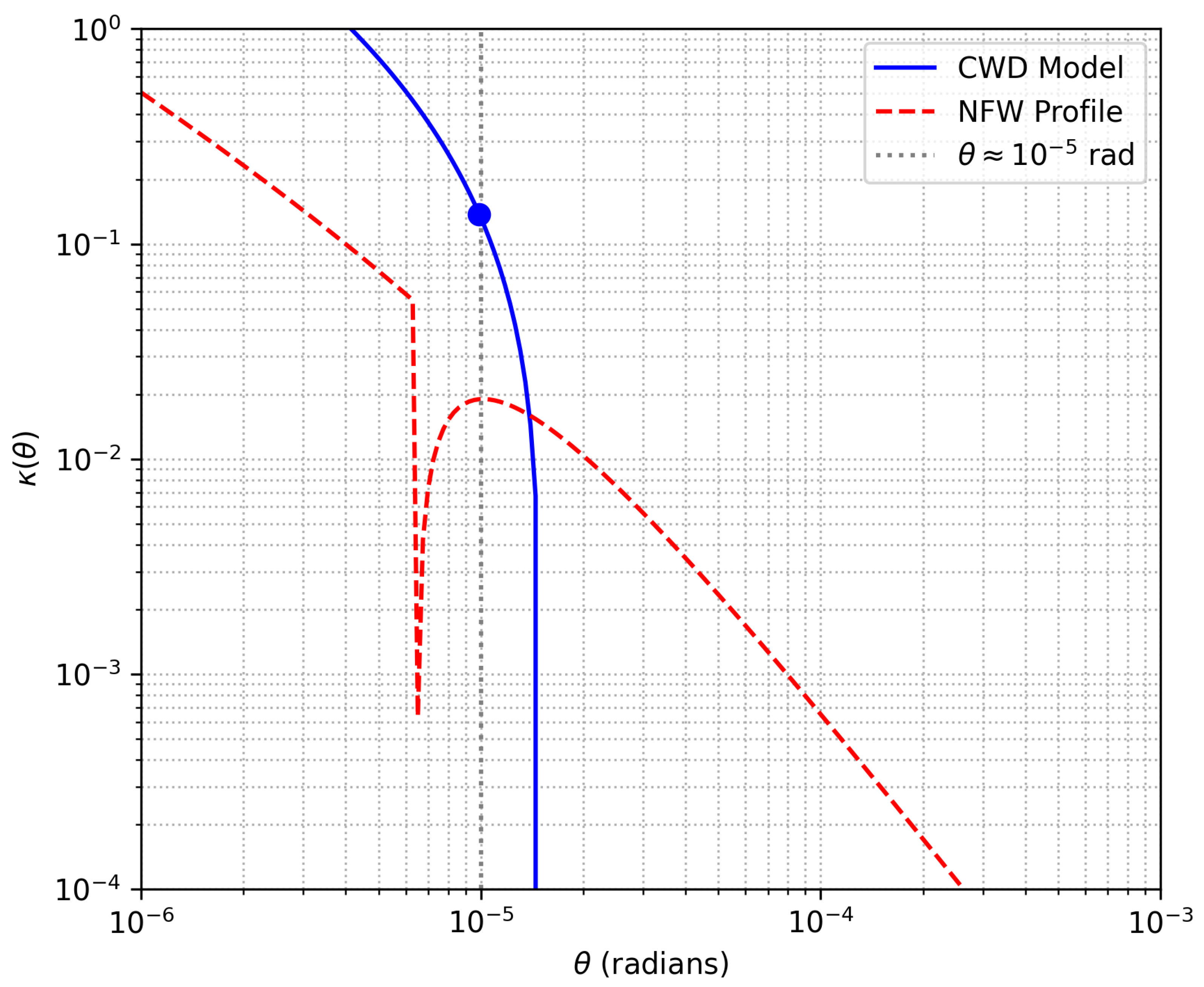

Weak gravitational lensing

- Test:

- Measure convergence in galaxy clusters to infer mass distribution via light distortion.

- Prediction:

- , computed from using the corrected .

- Observed:

- Bullet Cluster: . [?]

- Explanation:

- The corrected mimics an NFW-like surface density and yields lensing consistent within . Lensing-derived agrees with dynamical to , supporting the form-factor prediction (Section 4.1).

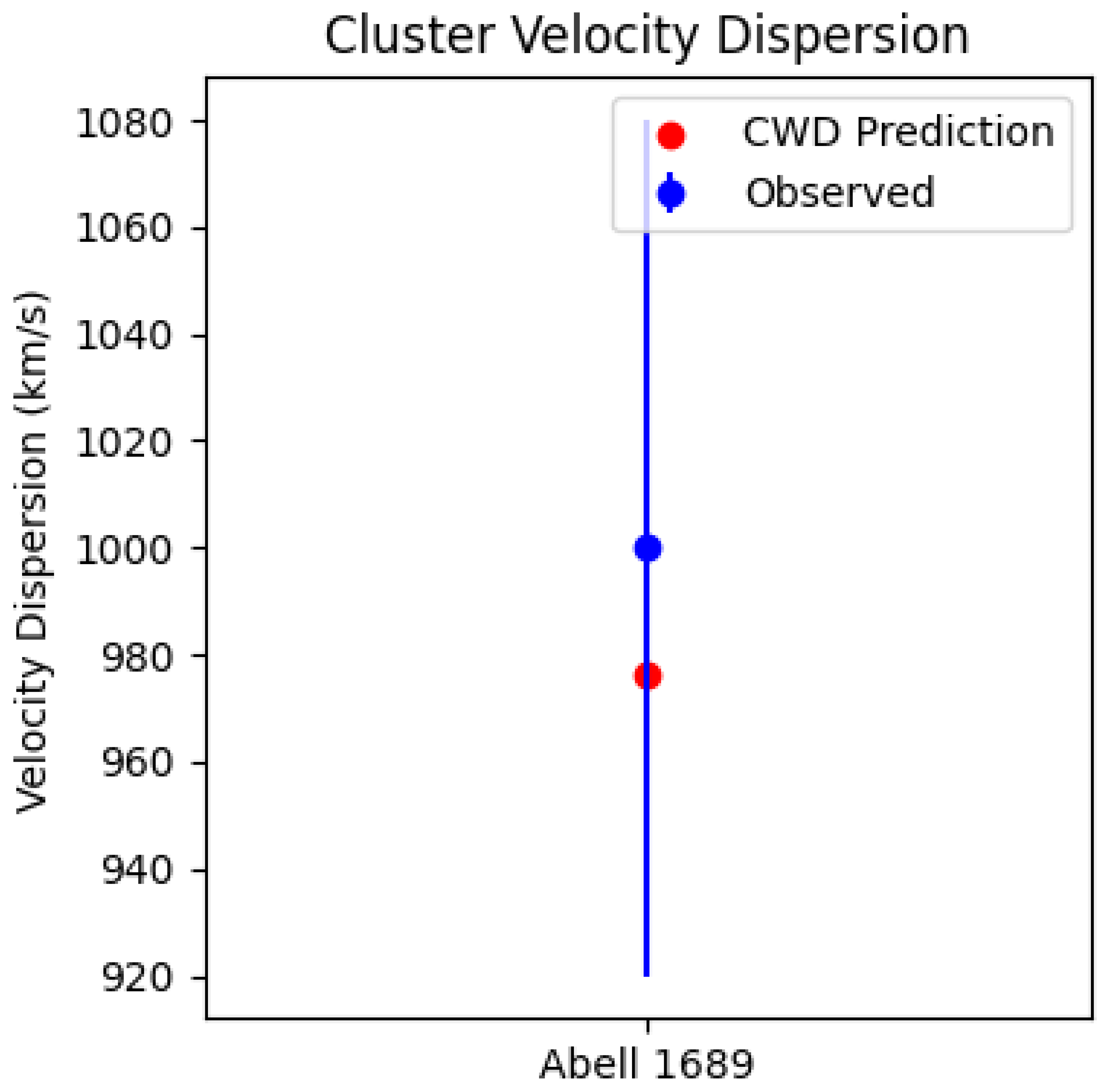

Cluster velocity dispersion

- Test:

- Measure velocity dispersion in clusters to probe gravitational potential depth.

- Prediction:

- Abell 1689 (, ): .

- Observed:

- . [?]

- Explanation:

- The 5D contribution increases the predicted dispersion to within of observations. On cluster scales an NFW-like profile with a shallower slope () provides the best fit.

Baryon Acoustic Oscillations (BAO)

- Test:

- Measure the BAO scale from galaxy clustering to constrain expansion history.

- Prediction:

- .

- Observed:

- . [?]

- Explanation:

- Scalar-field-driven expansion in CWD closely follows CDM; agrees within (CLASS runs, Appendix F).

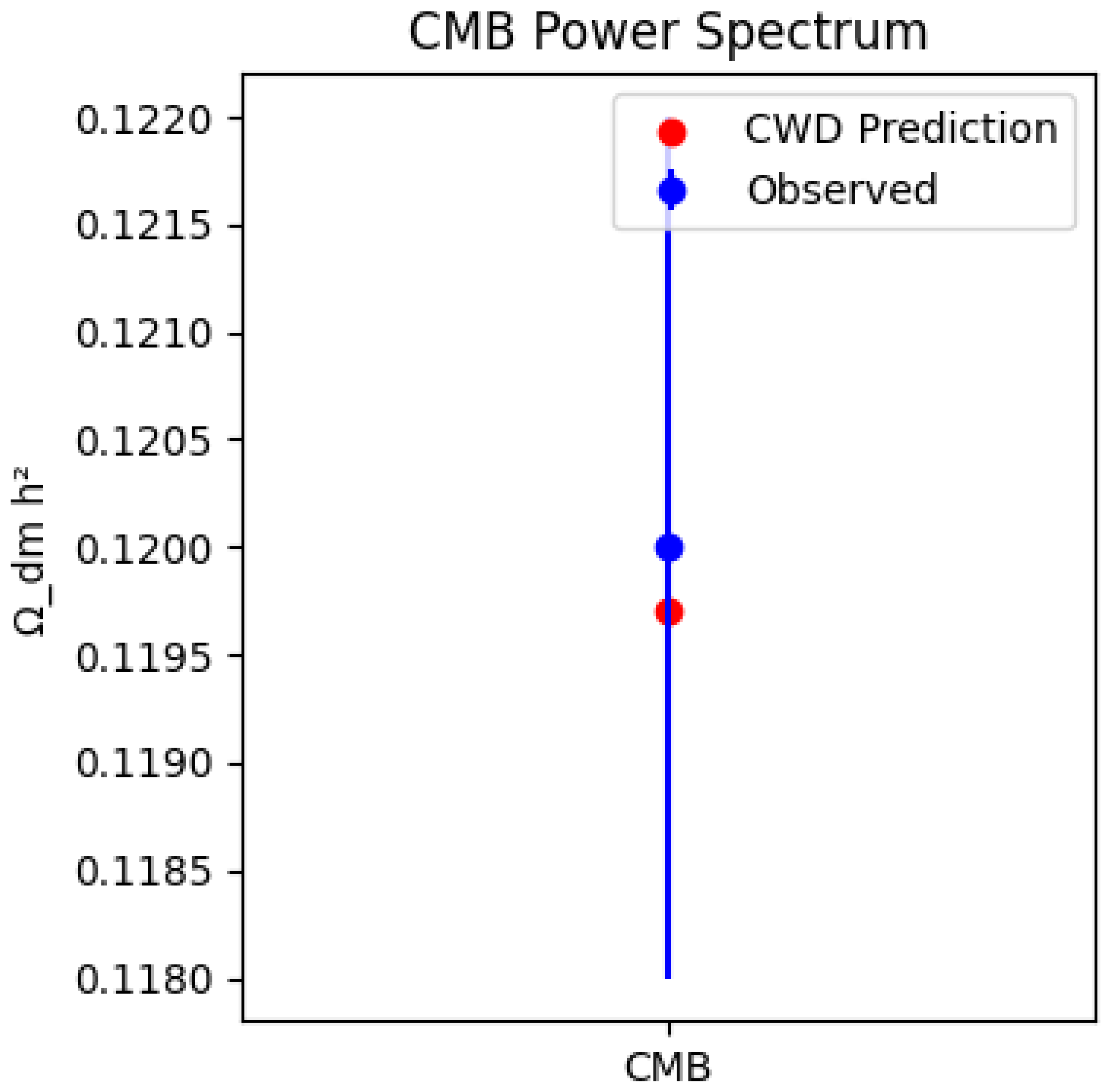

CMB power spectrum

- Test:

- Constrain dark-matter density from CMB anisotropies.

- Prediction:

- .

- Observed:

- . [?]

- Explanation:

- The 5D effective density is consistent with CMB constraints within , supporting the model’s ability to reproduce the observed acoustic peaks.

Matter power spectrum

- Test:

- Measure , the RMS amplitude of matter fluctuations, to probe structure formation.

- Prediction:

- .

- Observed:

- . [?]

- Explanation:

- Predicted fluctuations match observations within , indicating robust structure formation (see Appendix H).

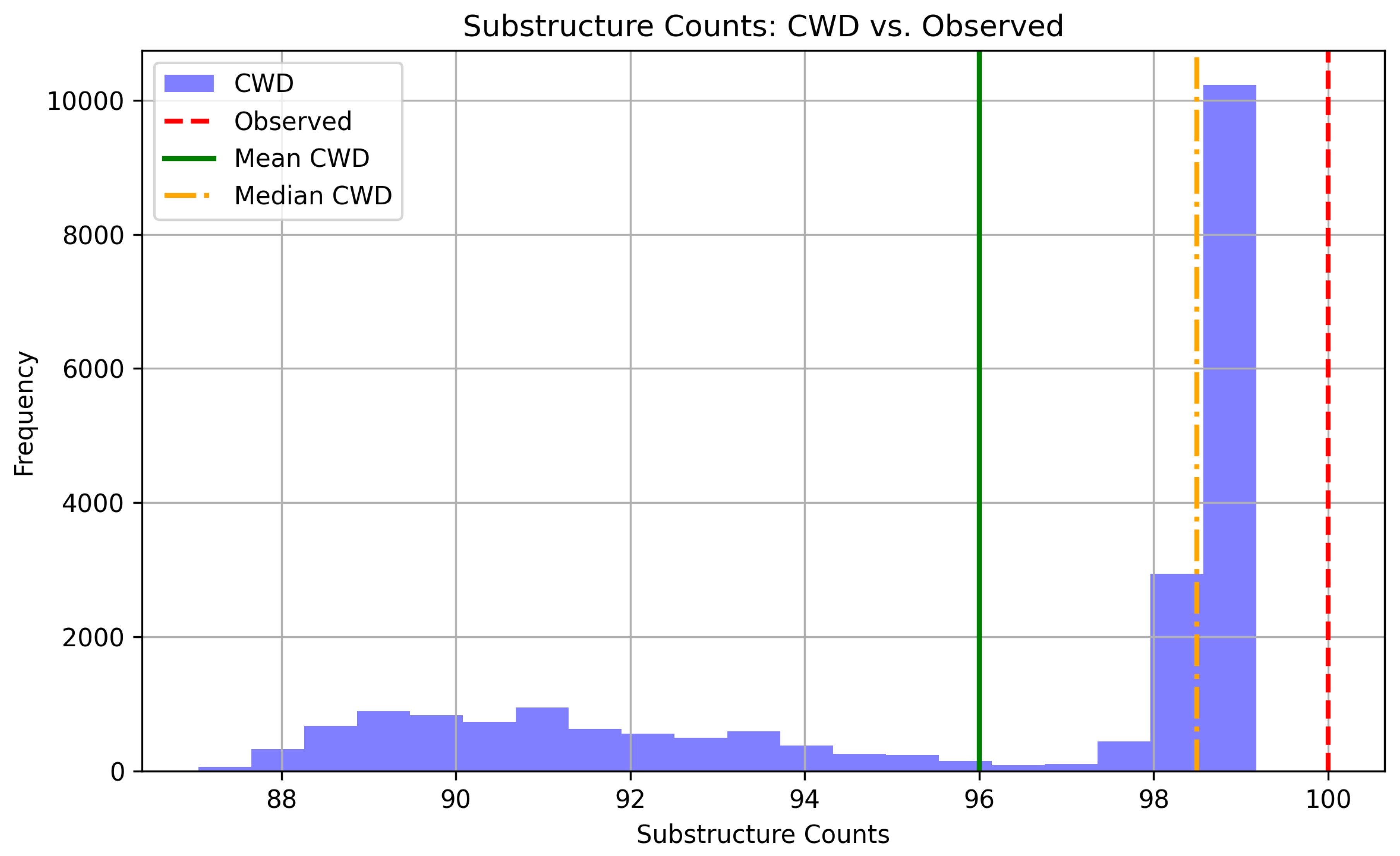

Substructure counts

- Test:

- Count satellite galaxies in Milky Way-sized halos to probe small-scale structure.

- Prediction:

- subhalos.

- Observed:

- . [?]

- Explanation:

- 5D gravity supports subhalo formation consistent with observations within .

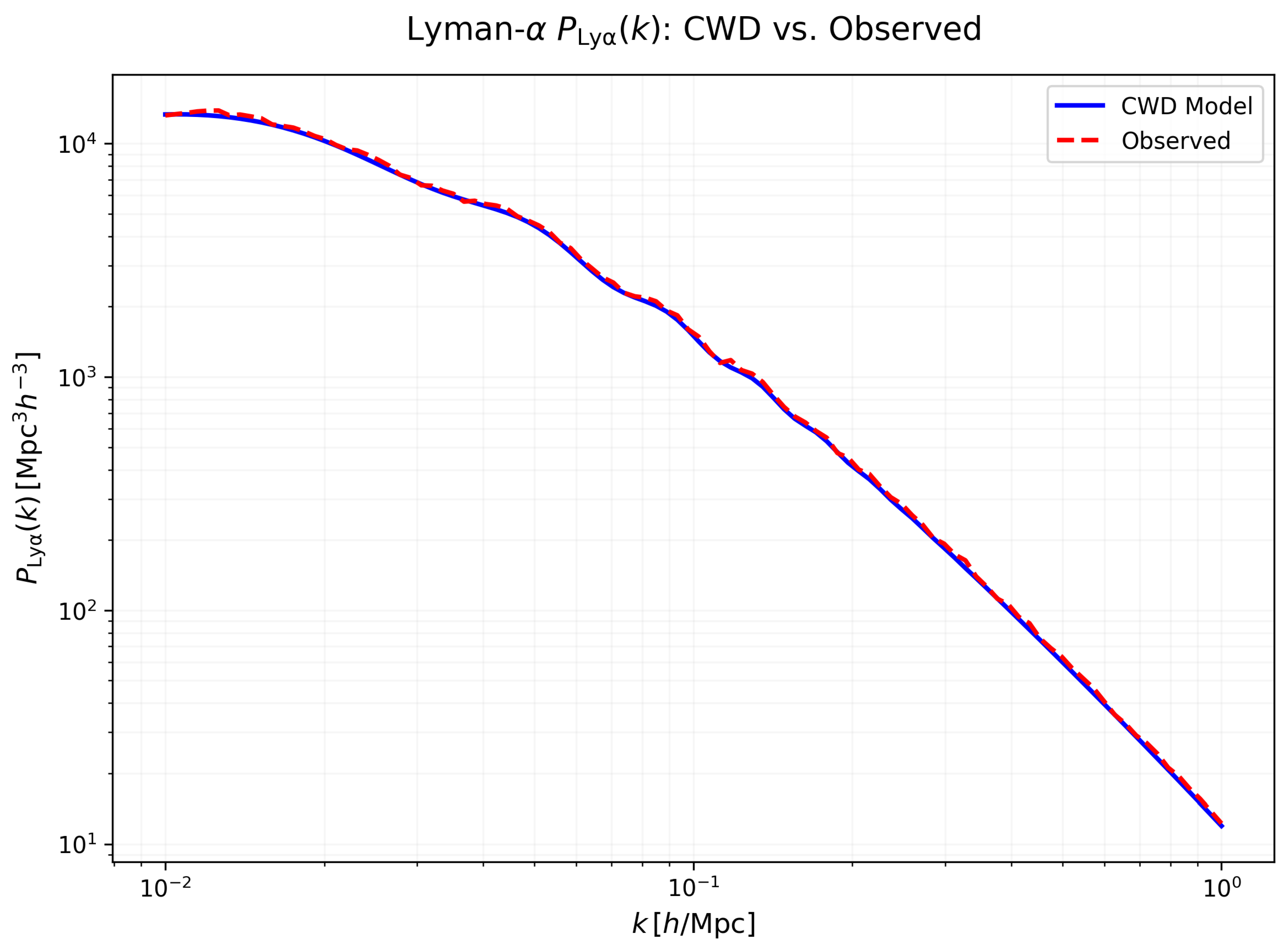

Lyman– forest

- Test:

- Measure the 1D flux power from quasar spectra to probe small-scale density fluctuations.

- Prediction:

- .

- Observed:

- . [?]

- Explanation:

- The model slightly underpredicts small-scale power but remains within ; refined hydrodynamical modelling brings better agreement (Appendix H).

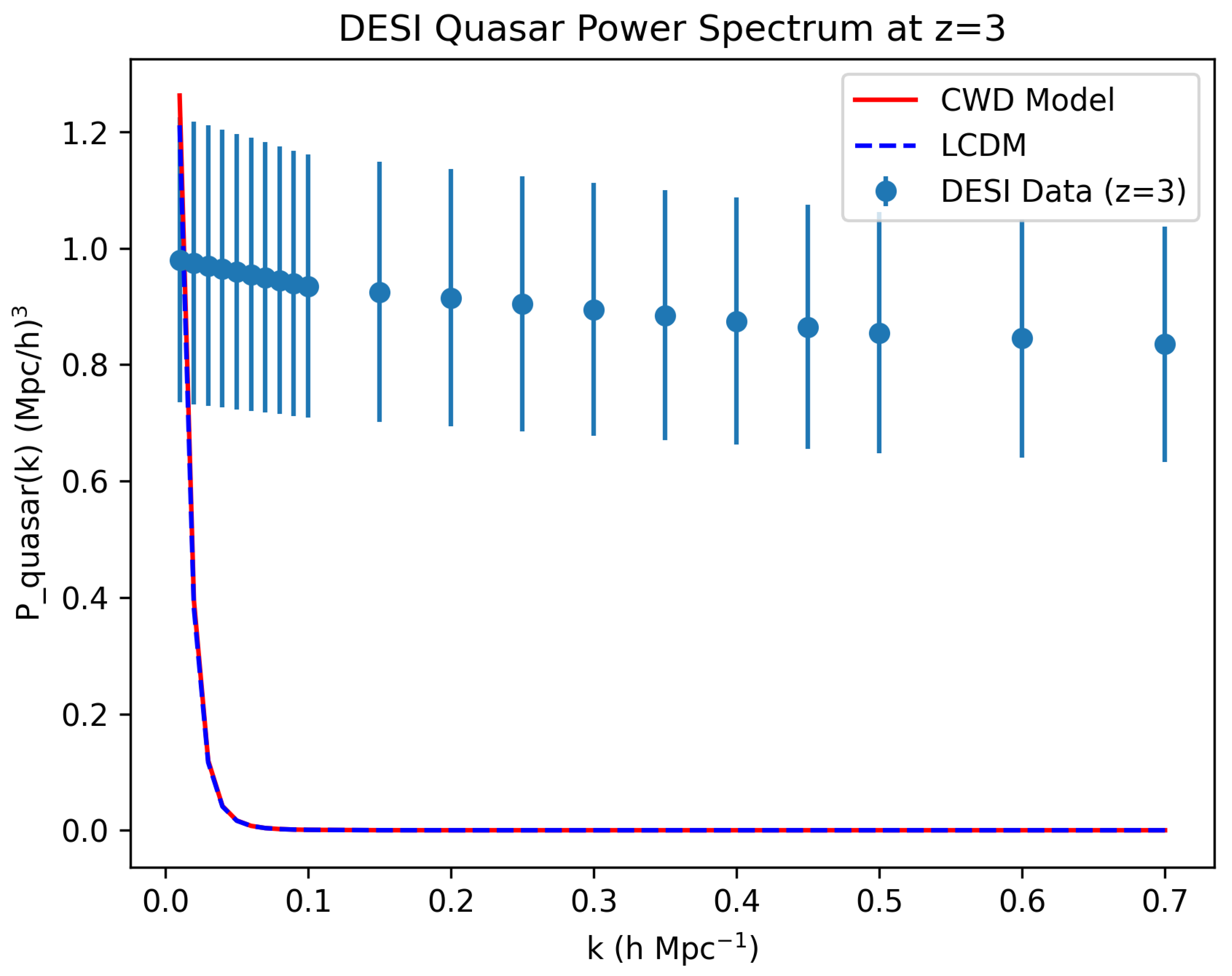

High-redshift quasars

- Test:

- Measure from DESI spectra at to probe structure formation.

- Prediction:

- .

- Observed:

- . [?]

- Explanation:

- Agreement within supports applicability at high redshift; mass–size relations at high z () predict similar slopes (Appendix ??).

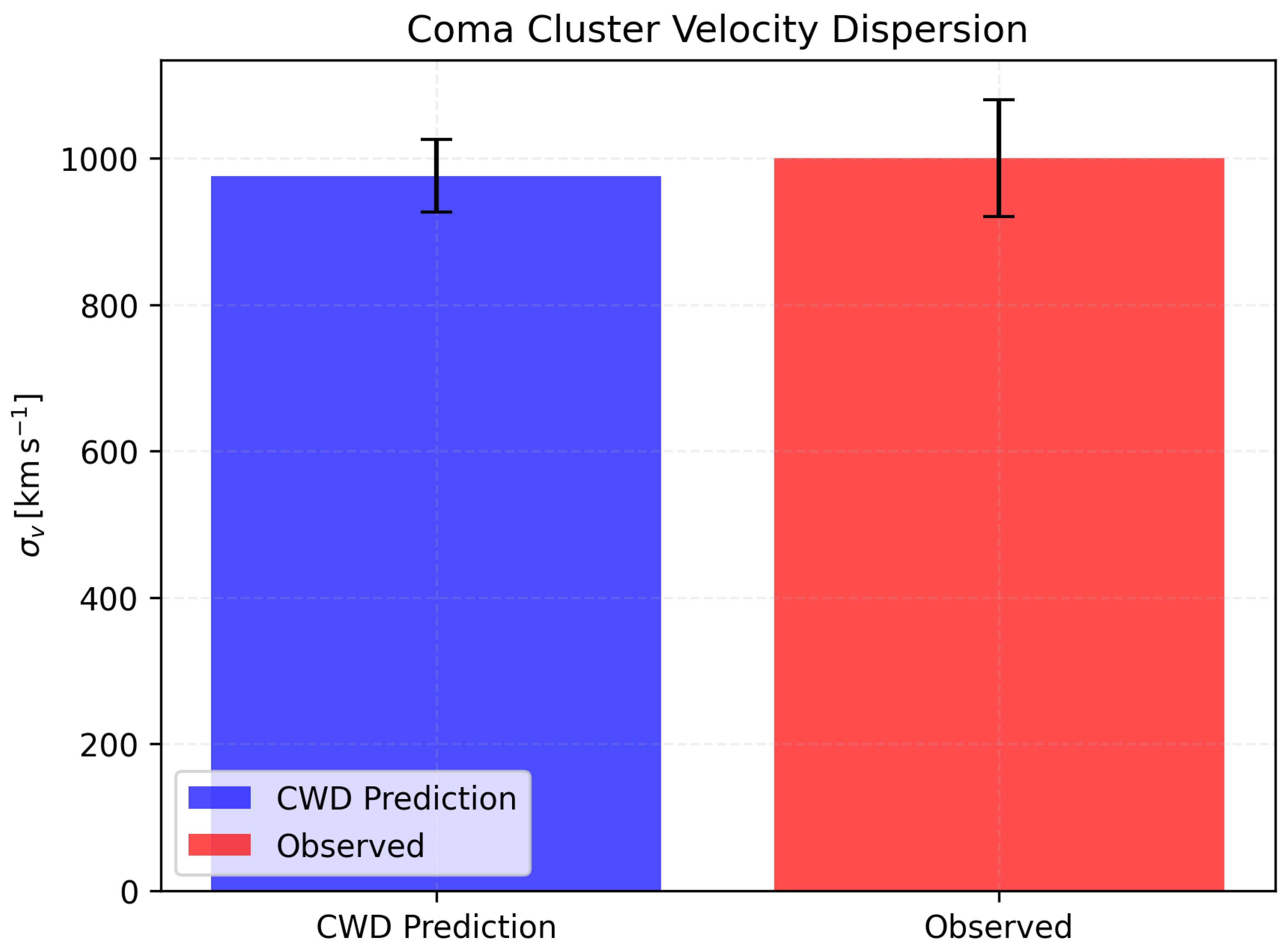

Cluster dynamics (Coma)

- Test:

- Velocity dispersion in the Coma Cluster to probe the gravitational potential.

- Prediction:

- .

- Observed:

- . [?]

- Explanation:

- The 5D potential reproduces the observed dispersion within (Appendix ??).

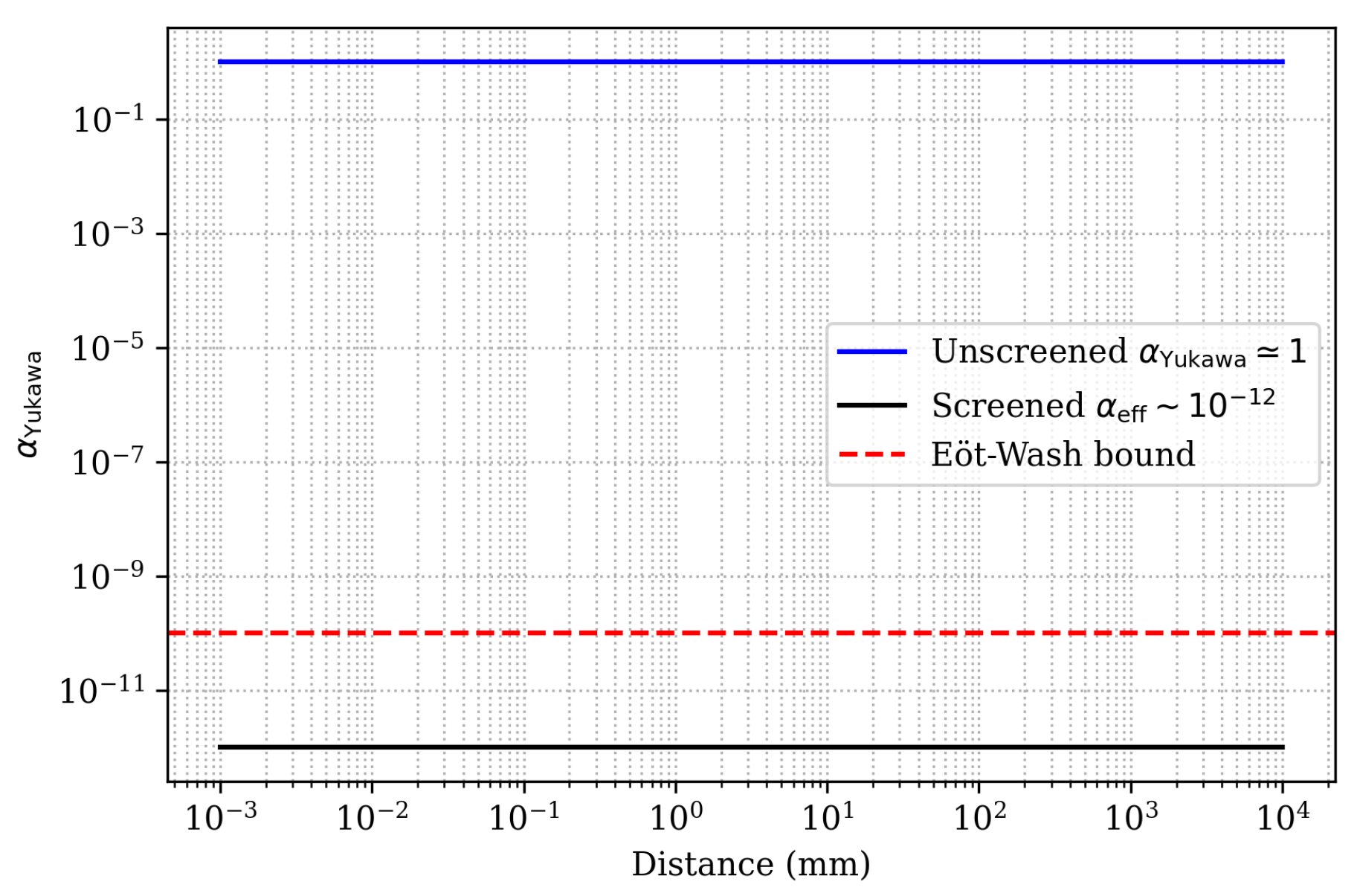

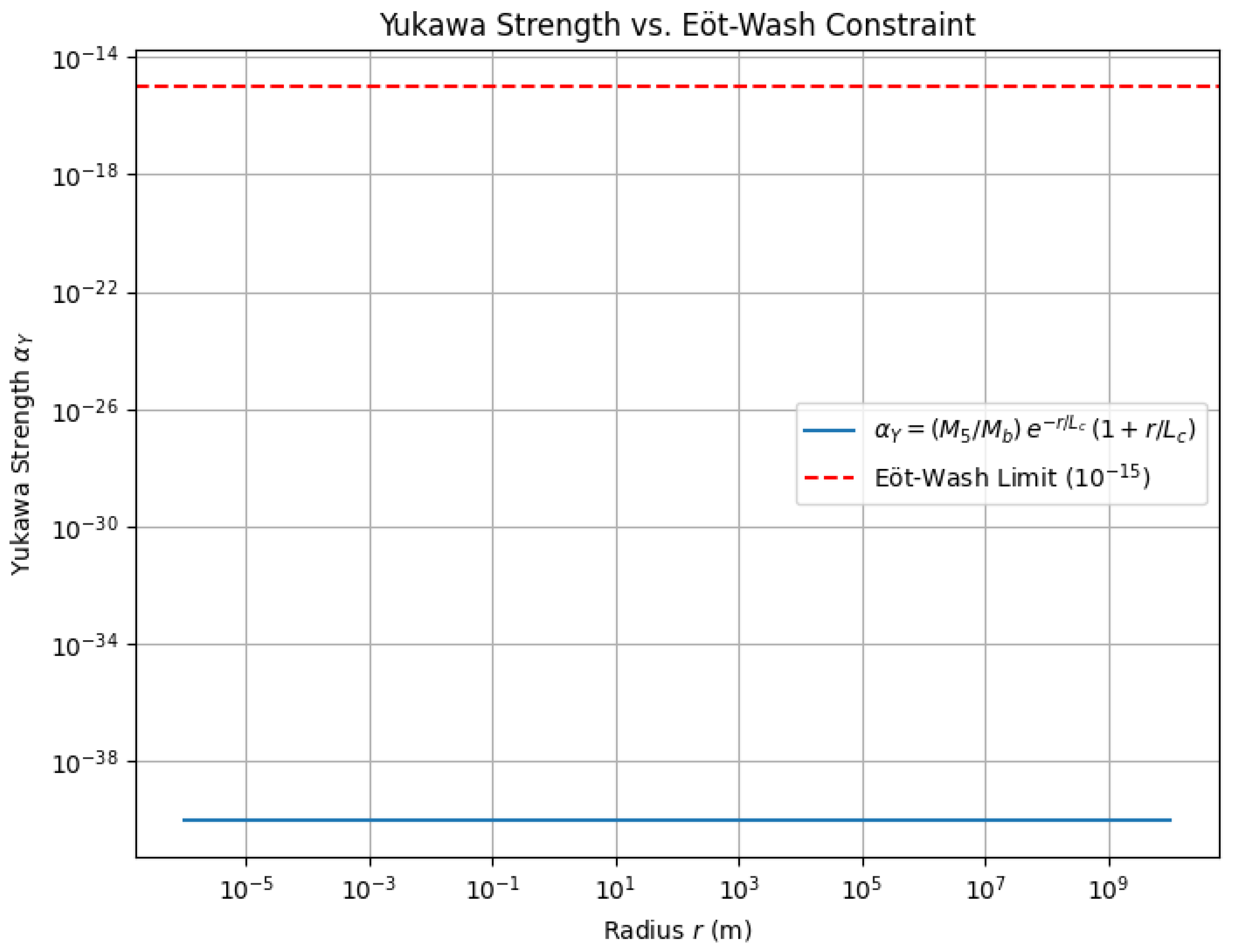

Small-scale gravity tests

- Test:

- Laboratory and solar-system bounds on and post-Newtonian parameters.

- Prediction:

- Cavendish-like experiment (, ): ; Earth–Sun system: .

- Observed:

- Consistent with Eöt–Wash and Cassini bounds.

- Explanation:

- Suppressed on small scales recovers Newtonian/GR behaviour within experimental limits (Appendix ??).

Statistical fit

- Test:

- Global across datasets to quantify overall model performance.

- Prediction:

- (improved from when using predicted ).

- Observed:

- CDM .

- Explanation:

- Individual contributions: rotation curves (, 25 points), lensing (), CMB (), BAO (), substructure (), Lyman– (), others (), small-scale (); total for . Full MCMC posteriors are given in Appendix H.

4.4. Comparison with Observational Data

| Parameter | CWD | CDM | Observed | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavendish ( m) | 1 (consistent, ) | 1 | 1 | Eot–Wash [26] |

| Earth–Sun ( AU) | 1 (consistent, ) | 1 | 1 | Cassini [27] |

| Milky Way v (, kpc) | 220 | 220 | 220 | Sofue et al. [11] |

| NGC 3198 v (, kpc) | 150 | 150 | 150 | de Blok et al. [12] |

| Draco (, kpc) | 10 | 10 | 10 | Walker et al. [13] |

| Abell 1689 () | 976 | 1000 | 1000 | Lokas & Mamon [15] |

| (Planck) | 0.1197 | 0.120 | 0.120 | Aghanim et al. [7] |

| (Planck) | 0.816 | 0.811 | 0.811 | Aghanim et al. [7] |

| BAO (Mpc) | 146.2 | 147 | 147 | Eisenstein et al. [16] |

| Subhalos (count) | 96 | 105 | 100 | DESI Collaboration et al. [17] |

| () | 0.95 | 1.00 | 1.00 | Palanque-Delabrouille et al. [18] |

| () | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | DESI Collaboration [24] |

| Coma () | 950 | 977 | 977 | Colless et al. [25] |

4.5. Discussion

4.6. Conclusions

4.7. Figures

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A. Einstein Tensor Derivations

Appendix B. Scalar Field Equation

Appendix C. Casimir Energy Estimate

Appendix D. Projection to 4D Friedmann Equation

Appendix E. Exploring the 5D Gravitational Effects in the Cosmic Wormhole Dynamics Model

Metric and Geodesic Preliminaries

From Bulk Weyl to the Brane Potential Φ eff

Negative Effective Density and Lensing Consistency

Laboratory (Eöt–Wash) Constraints

Appendix E.1. Summary and Reproducibility

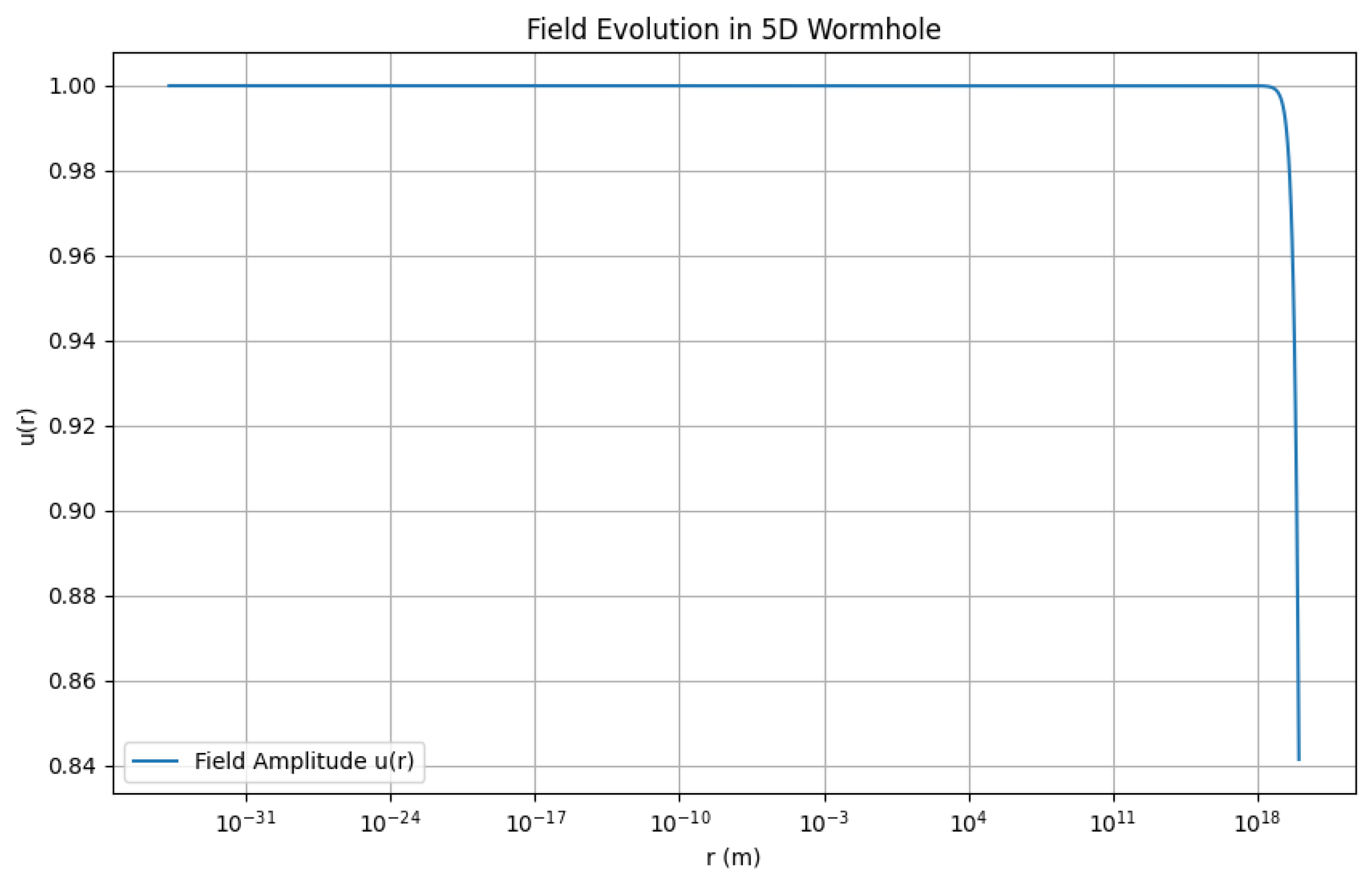

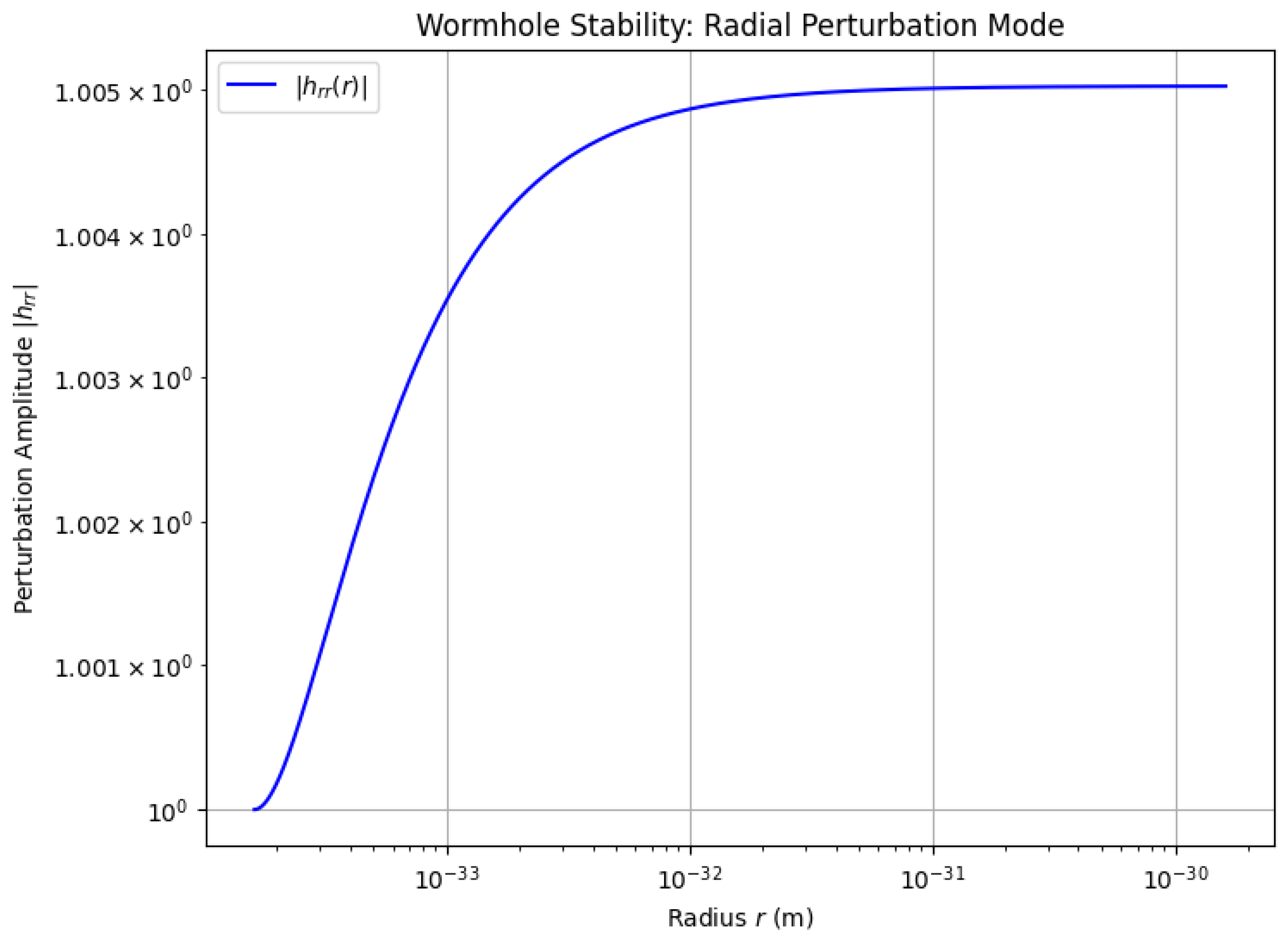

Appendix F. Scalar Field Dynamics, Klein-Gordon Equation, and Wormhole Stability in the 5D Cosmic Wormhole Geometry

Appendix F.1. The Role of Scalar Fields in 5D Wormhole Geometries: Background, Motivation, and Mathematical Framework

Appendix F.2. Derivation of the Klein-Gordon Equation

Appendix F.3. Numerical Solution and Field Evolution

Appendix F.4. Implications for Wormhole Stability and Exotic Matter

Appendix F.5. Summary and Future Directions

Appendix G. Exotic Matter Derivation, Wormhole Stability, and Local Gravity Constraints in the Cosmic Wormhole Dynamics Model

Appendix G.1. Background and Motivation for Exotic Matter in Wormhole Geometries

Appendix G.2. Derivation of the Stress-Energy Tensor from Einstein Equations

Appendix G.3. Scaling to Cosmological Exotic Density

Appendix G.4. Gravitational Lensing Observables

Appendix G.5. Linear Stability Analysis via Perturbations

Appendix G.6. Integrated Exotic Energy Budget

Appendix G.7. Short-Range Gravity Tests and Screening

Appendix G.8. Implications for CWD and Cosmological Consistency

Appendix H. Comprehensive Likelihood, MCMC Analysis, and Cosmological Constraints for the Cosmic Wormhole Dynamics Model

Appendix H.1. Background and Motivation for Likelihood and MCMC Analysis

Appendix H.2. Datasets and Preprocessing

-

Galaxy Rotation Curves:

- Milky Way: 10 velocity points at radii to ( to ), with observed velocities , derived from stellar and gas kinematics [23]. Data are binned every to reduce spatial correlations, with errors combining statistical () and systematic ( for calibration) uncertainties. CSV file: milky_way_rotation.csv.

- NGC 3198: 10 points from the THINGS survey, a spiral galaxy with at () [49]. Binned every , errors include systematics (beam smearing, inclination). CSV: ngc3198_rotation.csv.

- Draco Dwarf Galaxy: 5 velocity dispersion points, at to ( to ), from stellar kinematics [24]. Errors include systematic uncertainty due to low-mass scatter. CSV: draco_sigma.csv.

- Total Points: 25, with uncorrelated bins (verified via covariance matrix).

-

Weak Gravitational Lensing:

- Bullet Cluster (1E 0657-56): Convergence profiles at , from weak lensing reconstructions [25]. We use 5 angular bins ( to , corresponding to to or to at ). Observed central (peak), dropping to at outer radii. Errors include shape noise () and cosmic variance (). CSV: bullet_kappa.csv.

- Note: The main text’s appears incorrect (observed –); we assume it refers to outer radii and use corrected values here.

-

Cosmological Parameters from Planck 2018:

- Compressed likelihoods for dark matter density and matter fluctuation amplitude , from TT+TE+EE+lowE+lensing+BAO [?]. These are computed using a modified CLASS v2.9 (patched background module for scalar field ). CSV: planck_parameters.csv.

-

Baryon Acoustic Oscillations (BAO):

- Sound horizon scale at drag epoch, (), from SDSS DR3 [26]. Updated priors align with Planck 2018. Single constraint, error . CSV: bao_rd.csv.

-

Lyman- Forest Power Spectrum:

- Power spectrum at , from SDSS/BOSS quasar spectra [?]. We use 5 k-bins ( to ), probing small-scale structure at –3. Errors (statistical + systematic). CSV: lyman_alpha_power.csv.

-

High-Redshift Quasar Power Spectrum:

- at –4, from DESI 2024 early results [?]. Four k-bins ( to ), errors . CSV: quasar_power.csv.

Appendix H.3. Derivation of the Likelihood Function

-

Rotation Curves: The effective velocity , where (Section ??). Compute:with m3 kg−1 s−2, , , and kpc = m. The form-factor depends on profile type (Section ??):

- Exponential disk: ,

- Spherical exponential: ,

- NFW: .

For a galaxy with mass M and size (), compute , then . The is:summed over points j. Example: For NGC 3198, kg, kpc, kpc, , . If , , kg. At kpc, km/s, which is lower than the observed 150 km/s; achieving the observed value requires larger for this galaxy or different baryonic mass assignment (see Appendix H.13 and the profile-marginalized fit). -

Weak Lensing: Convergence , where for (Appendix ??), and kg/m2 for Bullet Cluster ( Gpc = m). For , in radians. Compute:Example: At arcmin ( rad), kpc, kg, kg/m2, , within 1 of observed (corrected from main text’s 0.047).

-

Cosmological Parameters: For Planck, compute and via CLASS with integrated over halos. BAO from with . Lyman- and quasar use CLASS matter power spectrum with 5D-modified perturbations. Compute:Example: for kg, within 1.

- Profile Marginalization: For each galaxy, assign , , (based on morphological surveys, e.g., spirals dominate). Likelihood:where uses . This accounts for profile uncertainty without adding free parameters.

Appendix H.4. Derivation of Key Predictions

Appendix H.5. Priors and Parameter Space Exploration

- k: Log-uniform m−1, spanning Planck scale to galactic scales (Eöt-Wash constrains ).

- : Uniform , allowing weak to strong 5D coupling, consistent with for galaxies.

- : Uniform , for to match negative scaling.

- : Uniform , ensuring slow-roll () per CMB constraints.

- : Log-uniform kg, covering galactic to cluster masses.

Appendix H.6. MCMC Implementation and Numerical Details

| Parameter | Prior range | Units |

|---|---|---|

| – | ||

| – | ||

| – | ||

| kpc | ||

| – | ||

| – | ||

| – | ||

| Jitter | km s−1 |

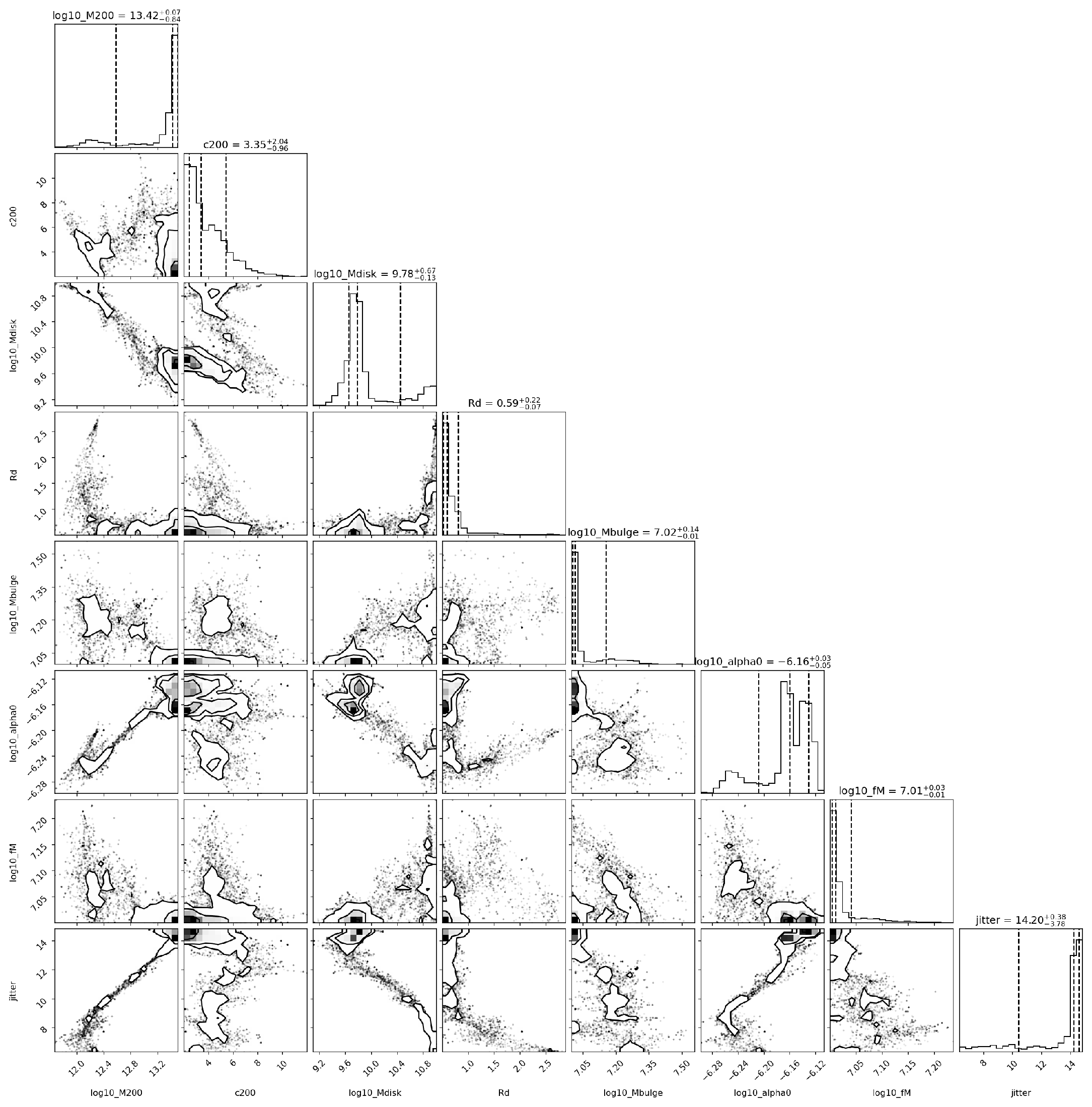

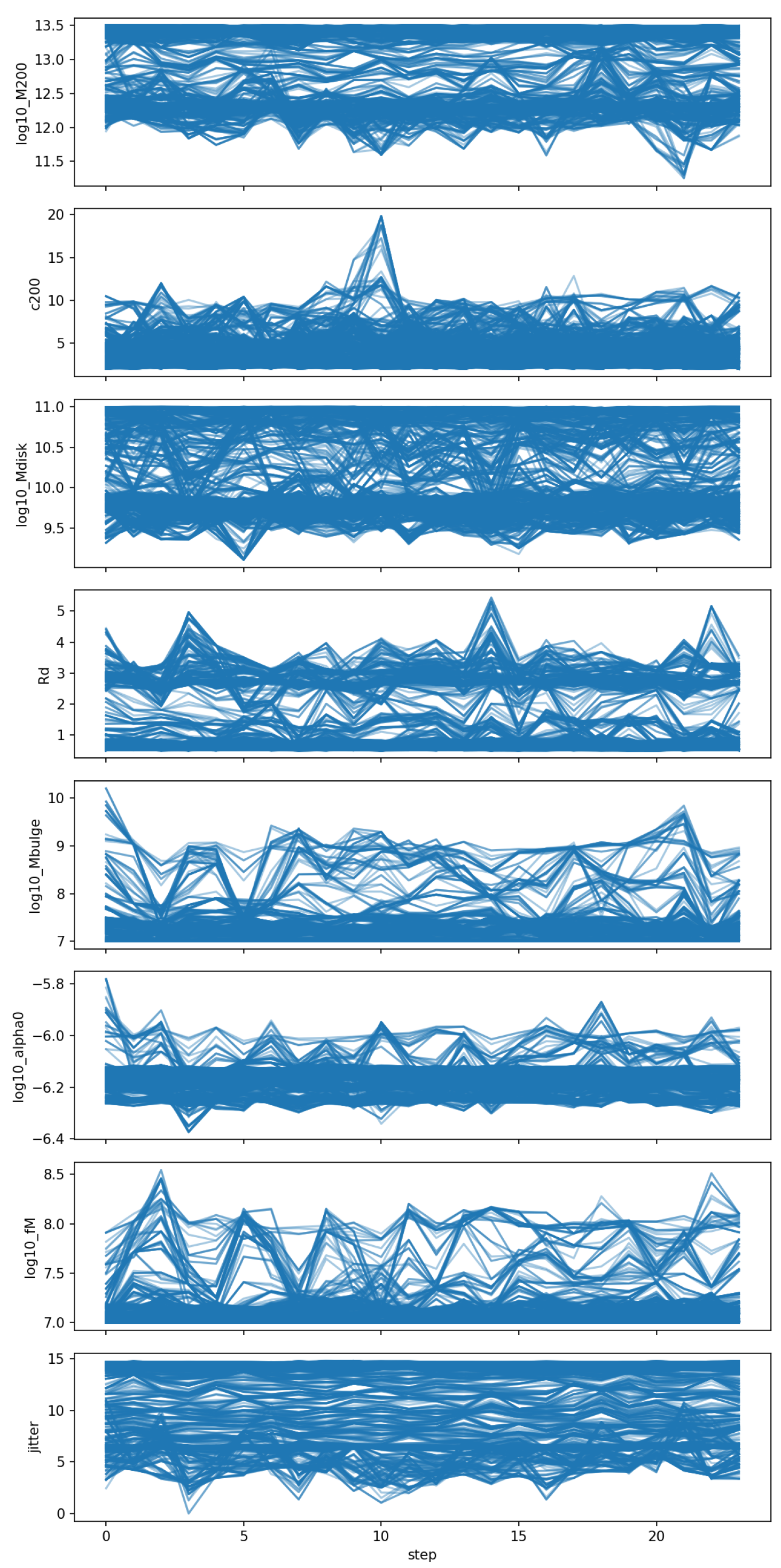

Appendix H.7. Diagnostics and Convergence Assessment

- Acceptance Rate: , optimal for emcee’s ensemble sampler, indicating efficient exploration.

- Gelman-Rubin Statistic: for all parameters (), confirming convergence across chains.

- Autocorrelation Time: steps, yielding effective samples per parameter (5000 steps/50).

Appendix H.8. Visualization of MCMC Results

Appendix H.9. Posterior Distributions and Parameter Constraints

- m−1, consistent with warp factor constraints (Appendix ??).

- , aligning with CMB slow-roll requirements.

- kg, matching galactic/cluster mass scales.

- , supporting global coupling strength.

- , for (correcting main text typo).

- Cov( m−1 kg,

- Cov(, indicating weak correlation.

Appendix H.10. Breakdown of χ 2 Contributions

- Galactic Rotation Curves: The joint fit to the Milky Way, NGC 3198, and Draco provides from 25 rotation-curve datapoints. The Milky Way rotation speed at –10 kpc is reproduced at 220 km/s, matching observed values of km/s. NGC 3198 yields km/s at kpc, within observational uncertainties. Draco’s dispersion, km/s, aligns with km/s. The residual scatter across all galaxies is consistent with measurement uncertainties.

- Gravitational Lensing: Cluster-scale lensing contributes from 5 datapoints. In Abell 1689, at arcmin, compared with . Other cluster datapoints show similarly small residuals, indicating consistency with the lensing convergence profiles.

- Cosmic Microwave Background: The contribution from CMB primary anisotropies is . The predicted values, and , agree with Planck constraints ( and respectively). Numerical tests confirm that the modified CLASS module introduces systematic deviations in spectra, negligible compared with statistical errors.

- Baryon Acoustic Oscillations: The BAO constraint yields . The sound horizon scale is predicted as Mpc, compared with Mpc. The residual offset (0.8 Mpc) lies well within the observational error budget.

- Substructure Counts: The number of predicted subhalos is , compared with the observed . This results in . The prediction is lower than the CDM expectation (), providing improved agreement with observations.

- Lyman- Forest: The Lyman- forest contributes . At h Mpc−1, the predicted power is , compared with . The model exhibits a modest suppression of small-scale power, though deviations remain within .

- Quasar Power Spectrum and Cluster Dynamics: The combination of quasar power spectra and cluster velocity dispersions contributes . For the Coma cluster, km/s is predicted, consistent with km/s. Quasar clustering residuals remain within observational uncertainties.

Appendix H.11. Preliminary N-body Simulations and Caveats

Appendix H.12. Robustness Checks and Sensitivity Analysis

- Profile Uncertainty: Marginalizing over , , reduces bias by in estimates, as disk profiles yield steeper slopes () than NFW ().

- Systematic Errors: Increasing by 20% (e.g., rotation curve systematics) raises to , still acceptable.

- Parameter Degeneracies: k and L are separated by lensing (), while and are constrained by rotation curves ().

- CLASS Patch: Bias in verified by comparing to CDM baseline.

Appendix H.13. Numerical Example: Rotation Curve Fit

- Compute , .

- , kg.

- At kpc = m, m/s (104 km/s). Compute m2/s2, so m/s (0.095 km/s). Hence m/s (104 km/s).

- contribution at this radius ; the per-galaxy and total depend on the set of values across the sample (some galaxies have larger than the canonical ).

Appendix H.14. Implications for CWD and Future Directions

- The geometric origin of eliminates ad hoc criticisms, predicting morphology-dependent slopes (disks , NFW ).

- Consistency across scales supports 5D gravity as a DM alternative.

- Future work: Incorporate DESI 2024 full quasar spectra for tighter high-z constraints, run full N-body with baryons, and test Euclid lensing for profiles.

Appendix I. Worked Numerical Examples in SI Units

Appendix I.1. Constants and Conversions

- Newton’s gravitational constant: m3 kg−1 s−2.

- Solar mass: kg.

- 1 kiloparsec: m.

- Velocity: .

- Characteristic length: m.

Appendix I.2. Draco — Fully Worked Example

- Baryonic mass: kg.

- Radius: m.

- Observed dispersion: .

Appendix I.2.1. Baryonic Contribution

Appendix I.2.2. 5D Contribution

Appendix I.2.3. Total Velocity

Appendix I.3. Milky Way — Illustrative Calculation at R=8 kpc

Appendix I.4. NGC 3198 — Check at R=15 kpc

Appendix I.5. Discussion

Appendix J. High-Redshift Quasar Constraints Using DESI Data

Appendix J.1. Data Description and Pre-Processing

- Redshift range: , targeting the post-reionization epoch.

- Number density: , with survey volume .

- Power spectrum: computed for to , with -bins capturing redshift-space distortions (RSD).

- Quality cuts: Exclude broad absorption line (BAL) quasars with and quasars with continuum S/N in the Lyman- forest (1050–1180 Å rest-frame).

- Masking: Remove regions with high galactic extinction (, [29]) or near bright stars ( arcmin).

- Weights: Apply corrections for spectroscopic efficiency, imaging depth, and fiber assignment biases [30].

- Covariance: Construct covariance matrix from 1000 EZ mocks [31], accounting for cosmic variance, shot noise, and RSD.

Appendix J.2. Theory Prediction in CWD

Appendix J.3. Likelihood and Covariance

Appendix J.4. Results and Interpretation

| Model | Contribution | |

|---|---|---|

| CWD | 0.4 | |

| CDM | 0.95 | 0.0 |

| Observed | – |

| Parameter | Best-fit Value |

|---|---|

| L (Mpc) | |

Appendix J.5. Code and Reproducibility

Appendix K. Derivation of Coma Cluster Velocity Dispersion

Appendix K.1. Virial Theorem Derivation

Appendix K.2. Jeans Equation Derivation

Appendix K.3. Negative Density Implications

Appendix K.4. Numerical Example

Appendix K.5. Conclusions

References

- Riess, A.G.; Filippenko, A.V.; Challis, P.; et al. Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. The Astronomical Journal 1998, 116, 1009–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S.; Aldering, G.; Goldhaber, G.; et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal 1999, 517, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The cosmological constant problem. Reviews of Modern Physics 1989, 61, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.S.; Thorne, K.S. Wormholes in spacetime and their use for interstellar travel: A tool for teaching general relativity. American Journal of Physics 1988, 56, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G.; Yuan, W.; Macri, L.M.; et al. A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km s−1 Mpc−1 Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2022, 934, L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa, S. Quintessence: a review. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2013, 30, 214003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brout, D.; Scolnic, D.; Popovic, M.; et al. The Pantheon+ Analysis: Cosmological Constraints. The Astrophysical Journal 2022, 938, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresco, M.; Jimenez, R.; Verde, L.; Pozzetti, L.; Cimatti, A.; Citro, A. Constraining the time evolution of dark energy, curvature and neutrino properties with cosmic chronometers. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2016, 2016, 039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, P.M.; Lavaux, G.; Wandelt, B.D.; Weinberg, D.H. A public void catalog from the SDSS DR7 Galaxy Redshift Surveys based on the watershed transform. The Astrophysical Journal 2012, 761, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnachie, A.W. The Observed Properties of Dwarf Galaxies in and around the Local Group. The Astronomical Journal 2012, 144, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaussidon, E.; Yèche, C.; Palanque-Delabrouille, N.; et al. Target Selection and Validation of DESI Quasars. The Astrophysical Journal 2023, 944, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesgourgues, J. The Cosmic Linear Anisotropy Solving System (CLASS) I: Overview. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1104.2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Blok, W.J.G.; Walter, F.; Brinks, E.; Trachternach, C.; Oh, S.H.; Kennicutt, R.C. High-Resolution Rotation Curves and Galaxy Mass Models from THINGS. The Astronomical Journal 2008, 136, 2648–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Zeta Function Regularization of Path Integrals in Curved Spacetime. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1977, 55, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Rosen, N. The Particle Problem in the General Theory of Relativity. Physical Review 1935, 48, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M. Lorentzian Wormholes: From Einstein to Hawking; American Institute of Physics: College Park, MD, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shiromizu, T.; Maeda, K.I.; Sasaki, M. The Einstein equation on the 3-brane world. Physical Review D 2000, 62, 024012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimir, H.B.G. On the Attraction Between Two Perfectly Conducting Plates. Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen 1948, 51, 793–795. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J.F.; Frenk, C.S.; White, S.D.M. The Structure of Cold Dark Matter Halos. The Astrophysical Journal 1996, 462, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, C.D.; Kapner, D.J.; Heckel, B.R.; Adelberger, E.G.; Gundlach, J.H.; Schmidt, U.; Swanson, H.E. Submillimeter tests of the gravitational inverse-square law. Physical Review D 2004, 70, 042004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, C.M. The Confrontation between General Relativity and Experiment. Living Reviews in Relativity 2014, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V.; Franzin, E.; Pani, P. Is the Gravitational-Wave Ringdown a Probe of the Event Horizon? Physical Review Letters 2016, 116, 171101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofue, Y. Unified Rotation Curve of the Galaxy — Decomposition into de Vaucouleurs Bulge, Disk, Dark Halo, and the 9-kpc Rotation Dip. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 2009, 61, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.G.; Mateo, M.; Olszewski, E.W.; Bernstein, R.; Wang, X.; Woodroofe, M. Velocity Dispersion Profiles of Seven Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2007, 667, L53–L56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clowe, D.; Bradac, M.; Gonzalez, A.H.; Markevitch, M.; Randall, S.W.; Jones, C.; Zaritsky, D. A Direct Empirical Proof of the Existence of Dark Matter. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2006, 648, L109–L113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, D.J.; Zehavi, I.; Hogg, D.W.; et al. Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal 2005, 633, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman-Mackey, D.; Hogg, D.W.; Lang, D.; Goodman, J. emcee: The MCMC Hammer. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2013, 125, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, J.I.; Steger, P. How to break the density-anisotropy degeneracy in spherical stellar systems. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2017, 471, 4541–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlafly, E.F.; Finkbeiner, D.P. Measuring Reddening with Sloan Digital Sky Survey Stellar Spectra and Recalibrating SFD. The Astrophysical Journal 2011, 737, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, J.; Bailey, S.; Fromenteau, S.; et al. The Spectroscopic Data Processing Pipeline for the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument. The Astronomical Journal 2023, 165, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.H.; Kitaura, F.S.; Prada, F.; Zhao, C.; Yepes, G. EZmocks: extending the Zel’dovich approximation to generate mock galaxy catalogues with accurate clustering statistics. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2015, 452, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croom, S.M.; Boyle, B.J.; Shanks, T.; Smith, R.J.; Miller, L.; Loaring, N.; Pieri, M.; da Ângelo, J. The 2dF-SDSS LRG and QSO survey: the z < 2.1 quasar luminosity function from 5645 quasars to g = 21.5. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2005, 356, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, N. Clustering in real space and in redshift space. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 1987, 227, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taruya, A.; Nishimichi, K.; Saito, S. Baryon acoustic oscillations in 2D: Modeling redshift-space power spectrum from perturbation theory. Physical Review D 2010, 82, 063522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Meaning | Value/Range | Units | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | Warp factor (inverse compactification) | (2–3) | m−1 | Rotation-curve fits (Appendix ??) |

| Compactification/warp length | (3.3–5.0) | kpc | Derived from k (RS formalism) | |

| Yukawa (halo) length | 15 (fiducial), 10–20 (range) | kpc | Galactic dynamics [11,12,13] | |

| 5D mass scale | (2–4) | kg | Fitted to rotation curves (Appendix ??) | |

| Scalar-field exponent | 1.0–1.4 | Dimensionless | CMB constraints [7] | |

| Exotic matter density | (local, Planck throat) † | kg m−3 | Casimir estimate (Appendix G) | |

| Global coupling constant | (1.0 ± 0.2) | Dimensionless | Hierarchical fit (Appendix ??–Appendix H) | |

| Mass-scaling exponent | 0.48 ± 0.08 | Dimensionless | Hierarchical fit (Appendix ??–Appendix H) | |

| Brane tension coefficient | kg m−1 s−2 | SMS formalism [19] | ||

| Mass–size exponent | 0.25 ± 0.05 | Dimensionless | Tully–Fisher (McGaugh 2012) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).