Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

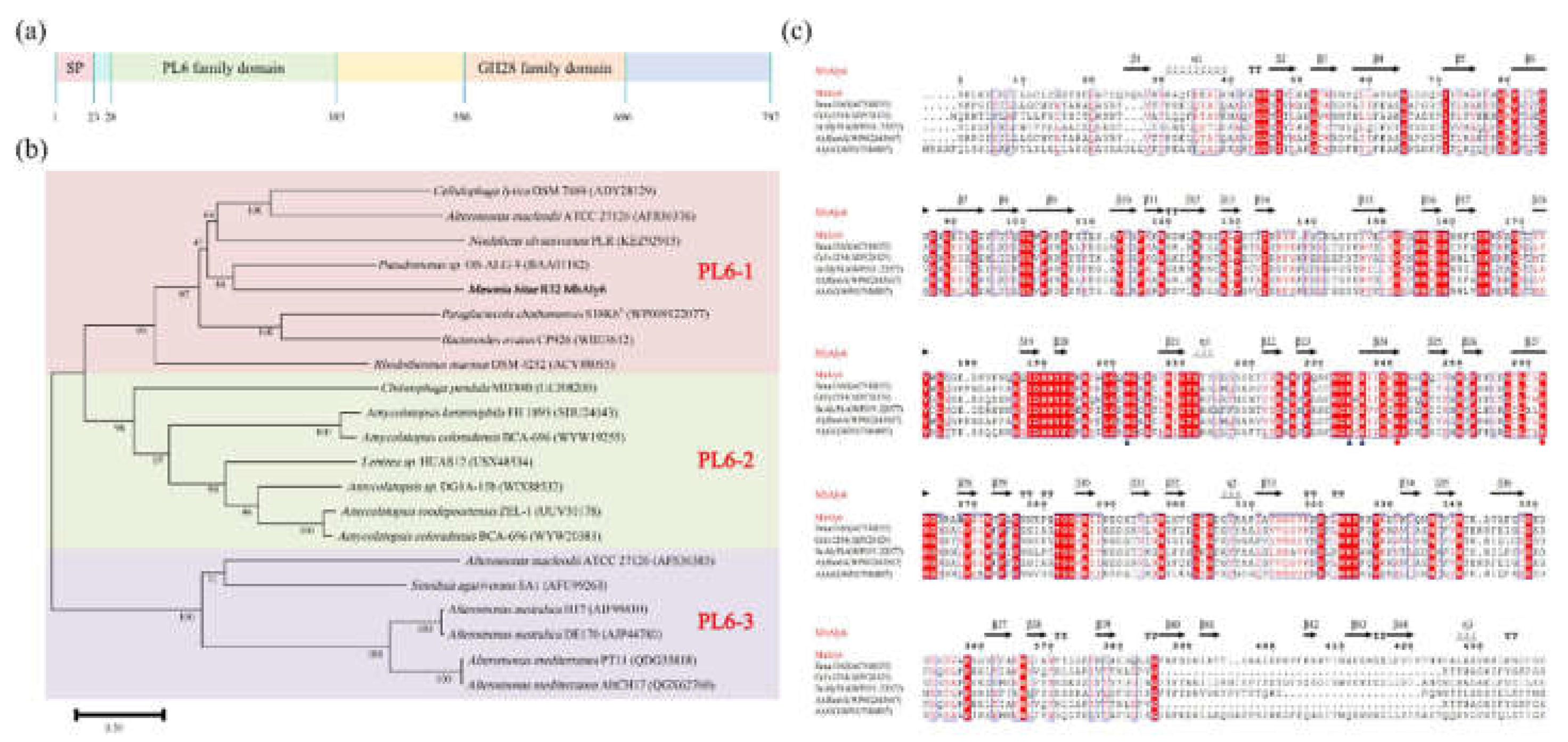

2.1. Analysis of Gene and Protein Sequence of MhAly6

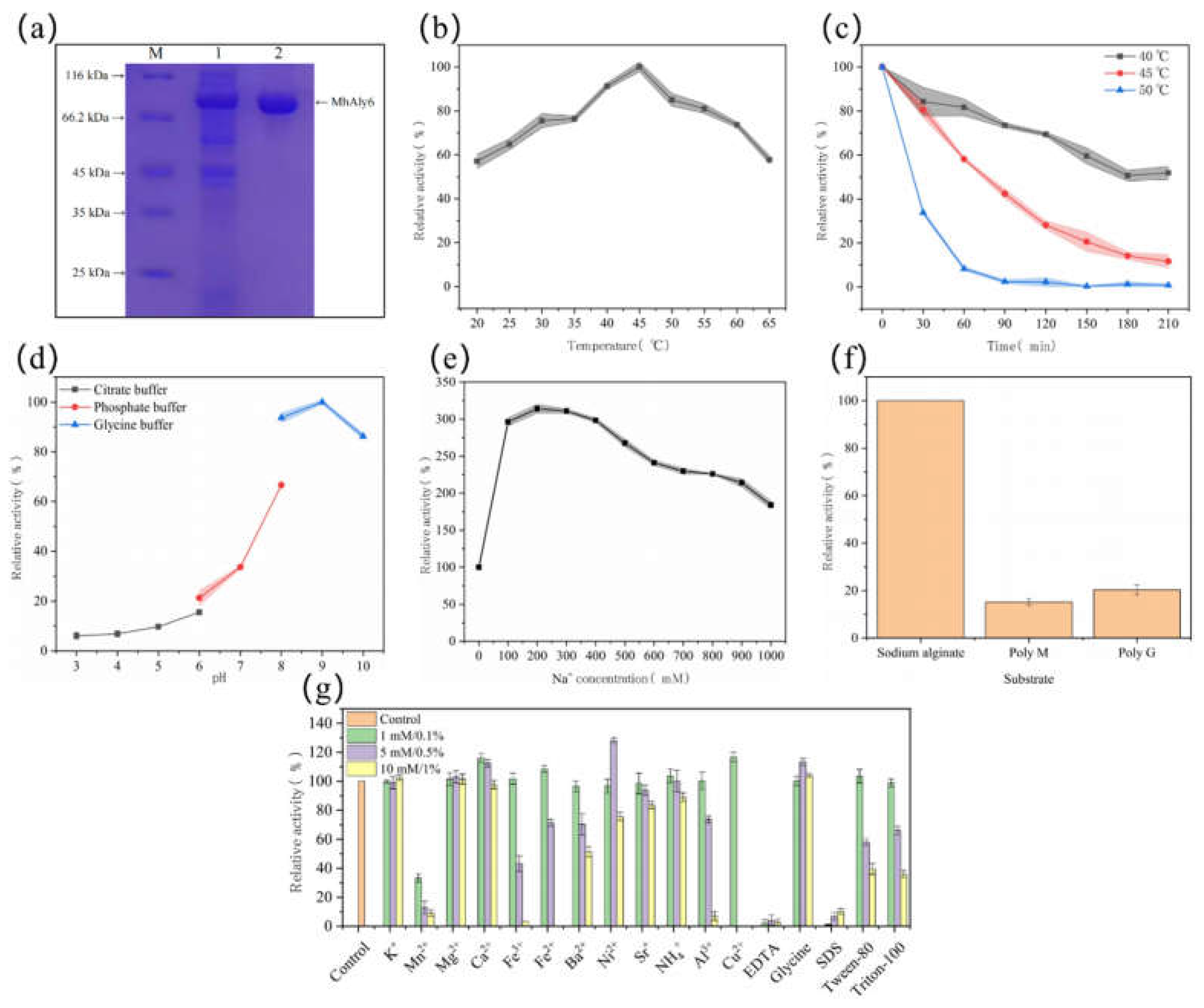

2.2. Biochemical Characterization of MhAly6

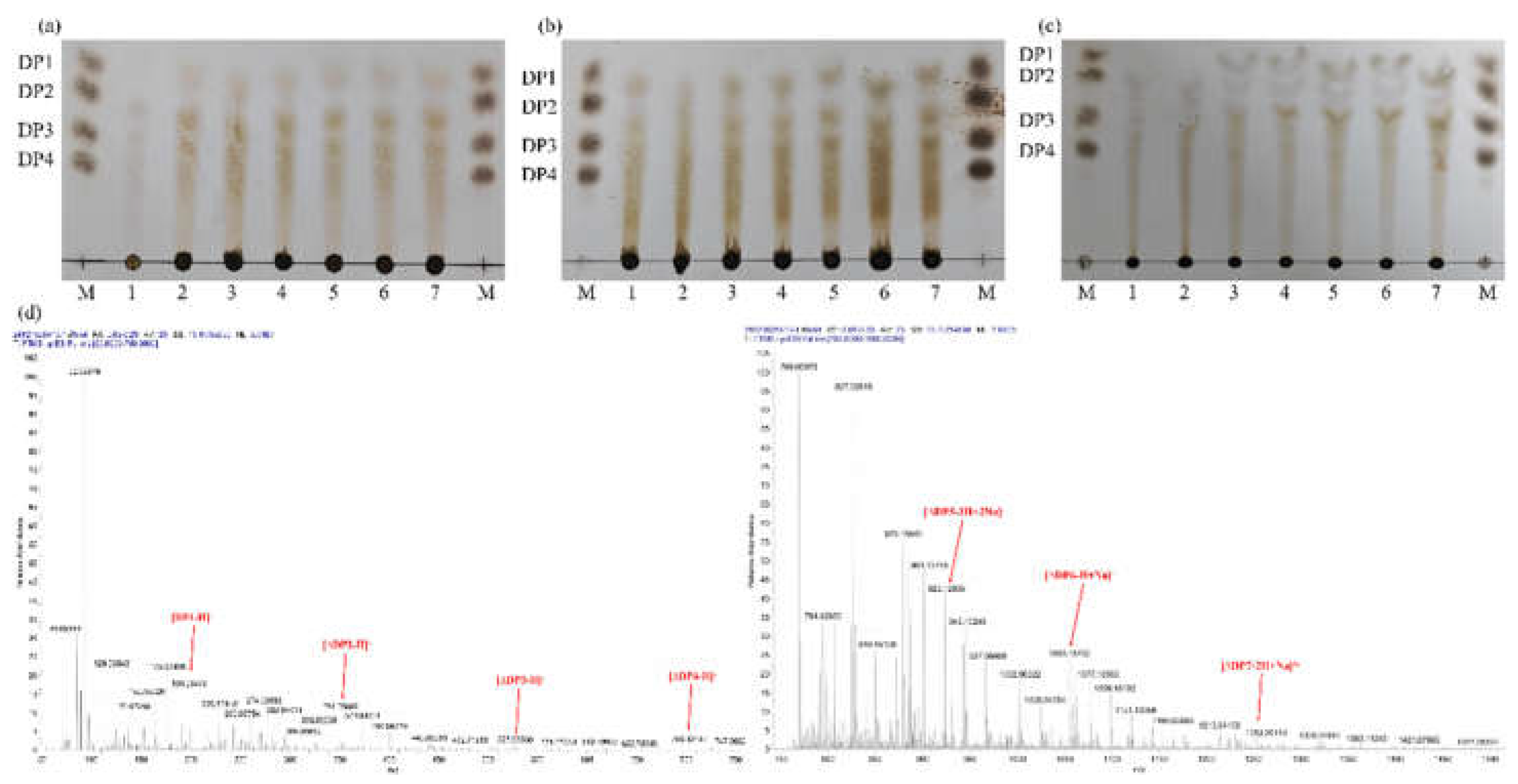

2.3. Analysis of the Degradation Products of MhAly6

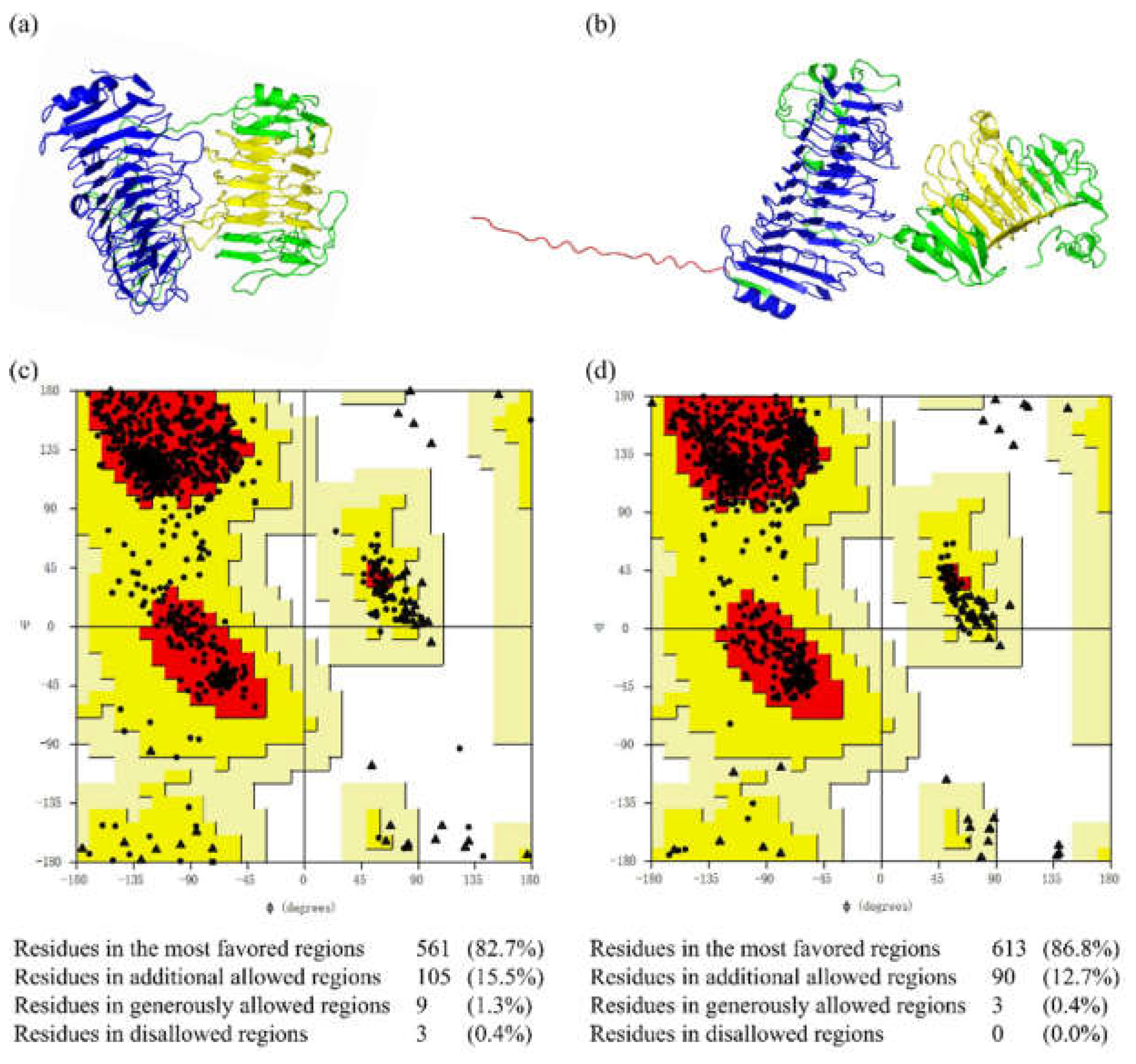

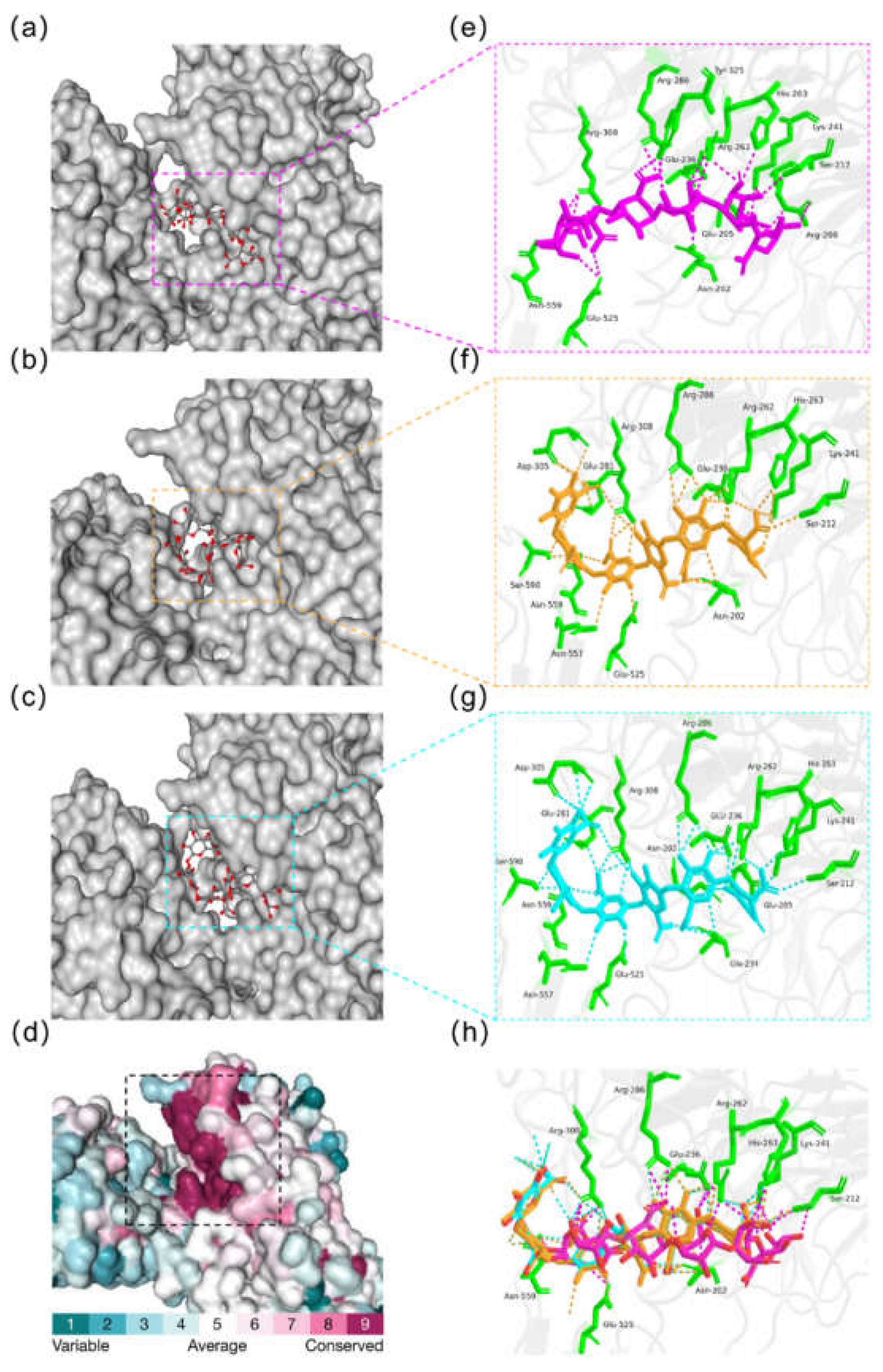

2.4. Structural Modeling and Evaluation of MhAly6

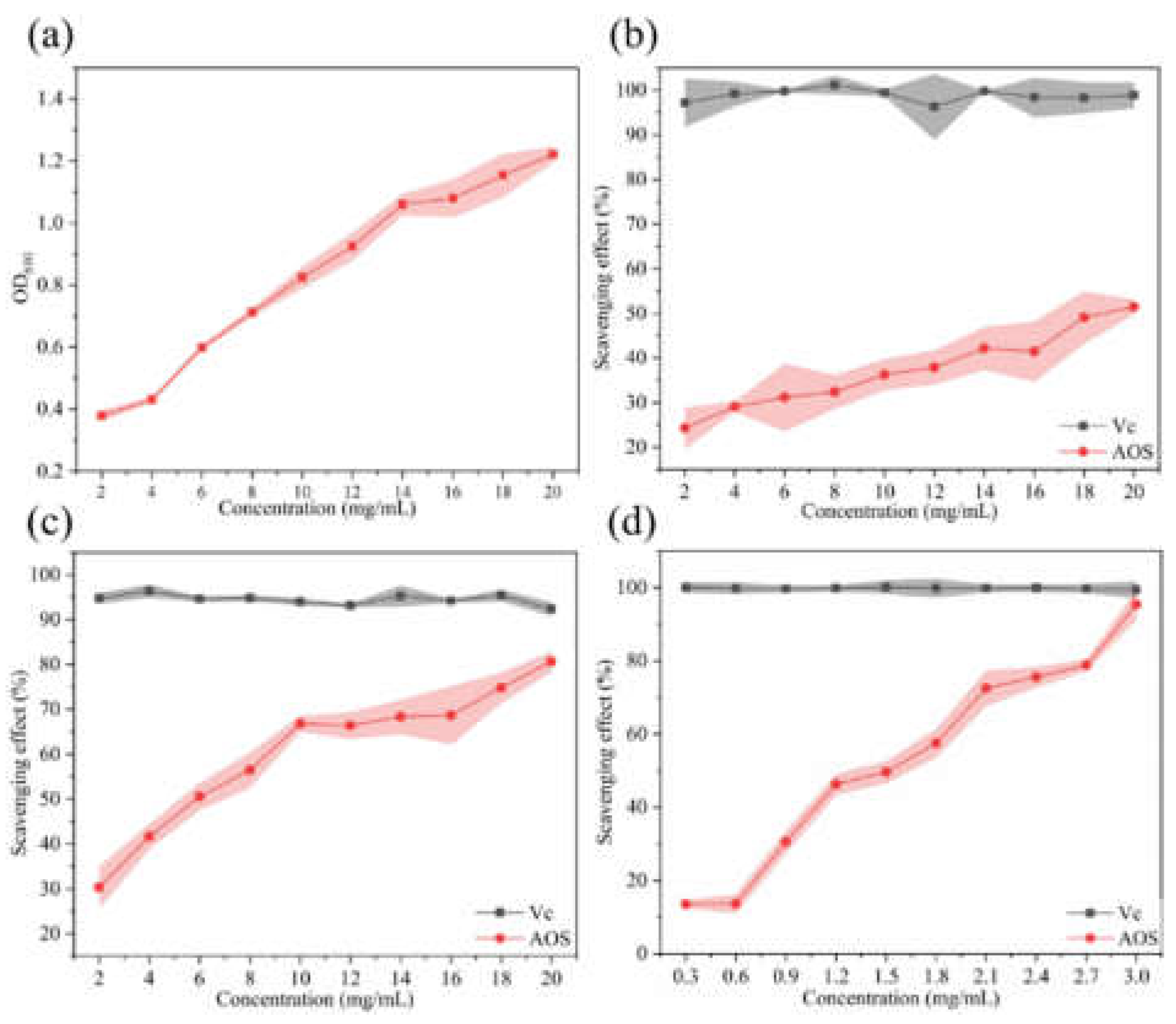

2.5. Antioxidant Activity of AOS Derived from MhAly6-Mediated Degradation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Strains

3.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

3.3. Cloning, Expression and Purification of MhAly6

3.4. Biochemical Characterization of MhAly6

3.5. Analysis of Degradation Products

3.6. Structural Modeling and Molecular Docking of MhAly6

3.7. Antioxidant Properties of the Alginate Degradation Products Produced by MhAly6

3.7.1. Ferric Reducing Capacity

3.7.2. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Capacity

3.7.3. Scavenging Activity of 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)

3.7.4. Scavenging Activity of 2,2′-Azinobis-(3-Ethylbenzthiazoline-6-Sulphonate) (ABTS)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| M | β-D-mannuronic acid |

| G | α-L-guluronic acid |

| Mw | Molecular weight |

| Poly M | Poly β-D-mannuronic acid |

| Poly G | Poly α-L-guluronic acid |

| AOS | Alginate oligosaccharides |

| DP | Degrees of polymerization |

| PL | Polysaccharide lyase |

| IPTG | Isopro-pyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

| ESI-MS | Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry |

| Vc | Ascorbic acid |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2′-Azinobis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonate) |

References

- Grobler, C.E.; Mabate, B.; Prins, A.; Le Roes-Hill, M.; Pletschke, B.I. Expression, Purification, and Characterisation of Recombinant Alginate Lyase (Flammeovirga AL2) for the Bioconversion of Alginate into Alginate Oligosaccharides. Molecules 2024, 29, 5578.

- Pirouzzadeh, M.; Moraffah, F.; Samadi, N.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Motasadizadeh, H.; Vatanara, A. Enhancement of burn wound healing using optimized bioactive probiotic-loaded alginate films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 301, 140454. [CrossRef]

- Alkhayer, M.; Hamzehpour, N.; Eghbal, M.K.; Rahnemaie, R. The use of magnesium-enriched brine for stabilization of highly erodible playa surfaces: A comparative study with sodium alginate and sodium silicate. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123339. [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, L.P.d.O.; Aroucha, E.M.M.; dos Santos, F.K.G.; Souza, R.L.d.S.e.; Nunes, R.I.; Leite, R.H.d.L. Influence of alginate extraction conditions from the brown seaweed Dictyota mertensii on the functional properties of a novel glycerol plasticized alginate film. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 352, 123225. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Luo, Y.; Liang, M.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Rhizobacteria protective hydrogel to promote plant growth and adaption to acidic soil. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Fu, L.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Zhao, L.; Seswita-Zilda, D.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J. A Novel Bifunctional Alginate Lyase and Antioxidant Activity of the Enzymatic Hydrolysates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 4116–4126. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.-M.; Lin, Q.; Zheng, B.-D.; Zhao, W.-L.; Ye, J.; Xiao, M.-T. Preparation and potential antitumor activity of alginate oligosaccharides degraded by alginate lyase from Cobetia marina. Carbohydr. Res. 2023, 534, 108962. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.; Luise, D.; Costa, M.; Carvalho, D.; Martins, C.; Correa, F.; Pinho, M.; Mirzapour-Kouhdasht, A.; Garcia-Vaquero, M.; Mourato, M.; et al. Impact of dietary Laminaria digitata with alginate lyase or carbohydrase mixture on nutrient digestibility and gut health of weaned piglets. Animal 2024, 18, 101189. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.M.; Leclercq, C.C.; Charton, S.A.; Costa, M.M.; Carvalho, D.F.P.; Cocco, E.; Sergeant, K.; Renaut, J.; Freire, J.P.B.; Prates, J.A.M.; et al. Enhanced ileum function in weaned piglets via Laminaria digitata and alginate lyase dietary inclusion: A combined proteomics and metabolomics analysis. J. Proteom. 2023, 289, 105013. [CrossRef]

- Ziane, S.O.; Imehli, Z.; Talibi, Z.E.A.; Koraichi, S.I.; Meddich, A.; El Modafar, C. Biocontrol of tomato Verticillium wilt disease by plant growth-promoting bacteria encapsulated in alginate extracted from brown seaweed. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133800. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Li, L.; Yuan, X. Efficient preparation of alginate oligosaccharides by using alginate lyases and evaluation of the development promoting effects on Brassica napus L. in saline-alkali environment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 131917. [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, J.; Yan, C.; Wang, A.; Xia, X. Alginate oligosaccharide improves 5-fluorouracil-induced intestinal mucositis by enhancing intestinal barrier and modulating intestinal levels of butyrate and isovalerate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133699. [CrossRef]

- Abdo, A.A.A.; Hou, Y.; Hassan, F.A.; Al-Sheraji, S.H.; Aleryani, H.; Alanazi, A.; Sang, Y. Antioxidant potential and protective effect of modified sea cucumber peptides against H2O2-induced oxidative damage in vitro HepG2 cells and in vivo zebrafish model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131090. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Uddin, M.; Singh, S.; Ahmed, K.B.M.; Bhat, U.H.; Chishti, A.S.; Chauhan, A.; Khan, M.M.A. Radiolytically Depolymerized Low Molecular-Weight Chitosan (ICH) and Sodium Alginate (ISA) Improve Growth Attributes, Physiological Performance and the Production of Steviol Glycosides (SGs) of S. rebaudiana (Bertoni). J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Samdurkar, A.N.; Choudhary, A.D.; Varshney, L.; Badere, R.S. Application of 28.1 kDa Alginate Oligosaccharide Improves the Yield and Quality of Grain in Rice. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.A.; Eliwa, N.E.; Safwat, G. Role of gamma-irradiated sodium alginate on growth, physiological and active components of iceberg lettuce (Lactuca sativa) plant. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.H.; Woo, H.C.; Lee, J. Eco-Friendly Depolymerization of Alginates by H2O2 and High-Frequency Ultrasonication. Clean Technologies 2023, 5, 1402–1414.

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, Y. Molecular Engineering of Alginate Lyases and the Potential Agricultural Applications of Their Enzymatic Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 5666–5684. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Na, K.; Wei, J.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X. Alginate oligosaccharides: The structure-function relationships and the directional preparation for application. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 284, 119225. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Chen, G.; Zheng, L.; Mei, X.; Xue, C.; Chang, Y. Discovery and characterization of a novel poly-mannuronate preferred alginate lyase: The first member of a new polysaccharide lyase family. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 343, 122474. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Fang, F.; Wang, J.; Huang, S.; Xu, J.; Peng, Y.; Xie, C. Isolation of salt-tolerant Vibrio alginolyticus X511 for efficient co-production of 2,3-butanediol and alginate lyase from Laminaria japonica. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 288, 138765. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Wang, Q.; Xu, W.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Q.; Liang, X.; Dong, X.; Li, F.; Peng, L. A bifunctional endolytic alginate lyase with two different lyase catalytic domains from Vibrio sp. H204. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1509599. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, M.; Mo, K.; Hu, Y.; Gu, H.; Sun, D.; Bao, S.; Huang, H. Genome Analysis of Multiple Polysaccharide-Degrading Bacterium Microbulbifer thermotolerans HB226069: Determination of Alginate Lyase Activity. Mar. Biotechnol. 2024, 26, 488–499. [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, R.; Ojima, T.; Ohnishi, Y.; Kumaki, Y.; Aizawa, T.; Inoue, A. An oxidative metabolic pathway of 4-deoxy-L-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronic acid (DEHU) from alginate in an alginate-assimilating bacterium. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.T.; Chataway, T.; Araujo, R.; Puri, M.; Franco, C.M.M. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Alginate Lyase from a Marine Streptomyces Species Isolated from Seaweed. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 590. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Li, J.; Gu, J.; Hu, W.; Han, W.; Li, Y. Alginate-Degrading Modes, Oligosaccharide-Yielding Properties, and Potential Applications of a Novel Bacterial Multifunctional Enzyme, Aly16-1. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2374. [CrossRef]

- Nedashkovskaya, O.I.; Kim, S.B.; Han, S.K.; Lysenko, A.M.; Rohde, M.; Zhukova, N.V.; Falsen, E.; Frolova, G.M.; Mikhailov, V.V.; Bae, K.S. Mesonia algae gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel marine bacterium of the family Flavobacteriaceae isolated from the green alga Acrosiphonia sonderi (Kutz) Kornm. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1967–1971. [CrossRef]

- Na Wang; Jia Rong Liu; Xi Ying Zhang; Shen Fan; Yu Zhong Zhang; Hui Hui Fu Mesonia Profundi Sp. Nov., Isolated from Deep-Sea Sediment of the Mariana Trench. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2024, 74.

- Rao, H.; Huan, R.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, X.; Li, W.; He, H. Characteristics and Application of a Novel Cold-Adapted and Salt-Tolerant Protease EK4-1 Produced by an Arctic Bacterium Mesonia algae K4-1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7985. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, X.; Xu, J.; Li, G.; Ma, R.; Yan, P.; Dong, C.; Shao, Z. Mesonia hitae sp. nov., isolated from the seawater of the South Atlantic Ocean. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 004911. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, L.; Liu, S.; Huang, Z.; Wang, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Mechanistic analysis of thermal stability in a novel thermophilic polygalacturonase MlPG28B derived from the marine fungus Mucor lusitanicus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 136007. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, S.; Henrissat, B.; Labre, F.; Skjåk-Bræk, G.; Helbert, W. Functional Exploration of the Polysaccharide Lyase Family PL6. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0159415. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Dong, S.; Li, F.-L.; Ma, X.-Q. Structural basis for the exolytic activity of polysaccharide lyase family 6 alginate lyase BcAlyPL6 from human gut microbe Bacteroides clarus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 547, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Dan, M.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhao, G.; Wang, D. Improving the thermostability of a novel PL-6 family alginate lyase by rational design engineering for industrial preparation of alginate oligosaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 249, 125998. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Dong, F.; Wang, P.; Cao, H.-Y.; Li, C.-Y.; Li, P.-Y.; Pang, X.-H.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Chen, X.-L. Novel Molecular Insights into the Catalytic Mechanism of Marine Bacterial Alginate Lyase AlyGC from Polysaccharide Lyase Family 6. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 4457–4468. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Cao, L.; Tang, W.; Liu, Z.; Feng, S. Improving the anti-autolytic ability of alkaline protease from Bacillus alcalophilus by a rationally combined strategy. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2024, 184, 110561. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Masuda, T.; Ohashi, H.; Mihara, H.; Suzuki, Y. Multiple Proline Substitutions Cumulatively Thermostabilize Bacillus Cereus ATCC7064 Oligo-1,6-Glucosidase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994, 226, 277–283.

- Gao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Su, H.; Tang, L.; Tan, Y.; Yu, W.; Han, F. Characterization of a new endo-type polysaccharide lyase (PL) family 6 alginate lyase with cold-adapted and metal ions-resisted property. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 729–735. [CrossRef]

- Belik, A.; Silchenko, A.; Malyarenko, O.; Rasin, A.; Kiseleva, M.; Kusaykin, M.; Ermakova, S. Two New Alginate Lyases of PL7 and PL6 Families from Polysaccharide-Degrading Bacterium Formosa Algae KMM 3553T: Structure, Properties, and Products Analysis. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 130.

- Li, Q.; Hu, F.; Wang, M.; Zhu, B.; Ni, F.; Yao, Z. Elucidation of degradation pattern and immobilization of a novel alginate lyase for preparation of alginate oligosaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 146, 579–587. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, C.; Li, L.; Xue, C.; Mao, X. Biochemical characterization and degradation pattern analysis of a novel PL-6 alginate lyase from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Food Chem. 2020, 323, 126852. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Sun, X.-M.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Fan, S.-J.; Xu, F. A Novel Alginate Lyase: Identification, Characterization, and Potential Application in Alginate Trisaccharide Preparation. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 159. [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Hu, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Ni, H.; Li, Q.; Zhu, Y. A bifunctional exolytic alginate lyase from Microbulbifer sp. ALW1 with salt activation and calcium-dependent catalysis. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2022, 161, 110109. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, W.; Lyu, Q.; Ran, L.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, X.-H. Characterization of Multiple Alginate Lyases in a Highly Efficient Alginate-Degrading Vibrio Strain and Its Degradation Strategy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0138922. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dan, M.; Li, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wang, D. Characterization of degradation patterns and enzymatic properties of a novel alkali-resistant alginate lyase AlyRm1 from Rubrivirga marina. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 6, 100414. [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Li, L.; Zhu, B.; Yao, Z. Elucidation of non-catalytic domain alterations effects on properties and action pattern of a novel alginate lyase. Process. Biochem. 2023, 133, 39–48. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; De Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [CrossRef]

- Studer, G.; Rempfer, C.; Waterhouse, A.M.; Gumienny, R.; Haas, J.; Schwede, T. QMEANDisCo—distance constraints applied on model quality estimation. Bioinformatics 2019, 36, 1765–1771. [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [CrossRef]

- Pontius, J.; Richelle, J.; Wodak, S.J. Deviations from Standard Atomic Volumes as a Quality Measure for Protein Crystal Structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 264, 121–136. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Shao, Y.; Jiao, C.; Yang, Q.-M.; Weng, H.-F.; Xiao, A.-F. Characterization and Application of an Alginate Lyase, Aly1281 from Marine Bacterium Pseudoalteromonas Carrageenovora ASY5. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 95.

- Kelishomi, Z.H.; Goliaei, B.; Mahdavi, H.; Nikoofar, A.; Rahimi, M.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A.; Mamashli, F.; Bigdeli, B. Antioxidant activity of low molecular weight alginate produced by thermal treatment. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 897–902. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Wu, K.-C.; Chiang, S.-H. Antioxidant properties and protein compositions of porcine haemoglobin hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1537–1543. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cui, D.; Ma, S.; Chen, W.; Chen, D.; Shen, H. Characterization of a novel PL 17 family alginate lyase with exolytic and endolytic cleavage activity from marine bacterium Microbulbifer sp. SH-1. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 169, 551–563. [CrossRef]

- Alashi, A.M.; Blanchard, C.L.; Mailer, R.J.; Agboola, S.O.; Mawson, A.J.; He, R.; Girgih, A.; Aluko, R.E. Antioxidant properties of Australian canola meal protein hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2014, 146, 500–506. [CrossRef]

- Puja, B.K.; Mallick, S.; Dey, T.; Chanda, S.; Ghosh, S. Xylooligosaccharide Recovery from Sugarcane Bagasse Using β-Xylosidase-Less Xylanase, BsXln1, Produced by Bacillus Stercoris DWS1: Characterization, Antioxidant Potential and Influence on Probiotics Growth under Anaerobic Conditions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 285, 138307.

| Enzyme | Source | Substrate Specificitya | AOS products (DP) | ActionMode | Activatorsb | Inhibitorsc |

Optimal Temperature (℃)/ pH |

Stability | Reference |

| MhAly6 | Mesonia hitae R32 | SA>PM> PG | 2-7 | Exo | Ni2+(5 mM); Cu2+(1 mM); Ca2+(1 mM) | Cu2+(5 mM); EDTA(10 mM); Fe3+(10 mM) | 45/9.0 | 40℃,60min, remaining 80% | This study |

| TsAly6A | Thalassomonas sp. LD5 | PG>SA>PM | 2-3 | Endo | Ca2+(-); Mg2+(-); Fe3+(-) | EDTA(-); SDS(-); Na+(500 mM) | 35/8.0 | 40 ℃, 60 min, remaining 29% | [38] |

| ALFA4 | Formosa algae KMM 3553T | - | 2(Main) | - | - | - | 30/8.0 | 37 ℃, 100 min, remaining 50% | [39] |

| AlyPL6 | Pedobacter hainanensis NJ-02 | SA>PG>PM | 2-6 | Exo | Na+(1 mM) | Mn2+(1 mM); Zn2+(1 mM); Co2+(1 mM) | 45/10 | 40 ℃, 60 min, remaining 50% | [40] |

| OUC-ScCD6 | Streptomyces ecolicolor A3(2) | SA>PM>PG | 2-10 | Endo | Mn2+(1 mM); Fe3+(1 mM); Zn2+(1 mM) | EDTA(1 mM); Ni2+(1 mM); Cu2+(1 mM) | 50/9.0 | 40 ℃, 60 min, remaining 50% | [41] |

| AlyM2 | Pseudoalteromonasarctica M9 | PMG>SA>PM>PG | 3(Main) | - | - | - | 30/8.0 | - | [42] |

| AlgL6 | Microbulbifer sp. ALW1 | PG>SA>PM | 2-4 | Exo | Tween 80(1%); Tween 20(1%); Na+(500 mM) | Cu2+(10 mM); Fe2+(10 mM); Ba2+(10 mM) | 35/8.0 | 40 ℃, 60 min, remaining 19% | [43] |

| VpAly-VII | Vibrio pelagius WXL662 | SA>PM>PG | 3-6 | Endo | - | - | 50/8.0 | - | [44] |

| AlyRm1 | Rubrivirga marina | PM>SA>PG | 2-5 | Exo | SDS(1 mM); Ca2+(1 mM); K+(1 mM) | EDTA(1 mM); Zn2+(1 mM); Mn2+(1 mM) | 30/10.0 | 40 ℃, 60 min, remaining 20% | [45] |

| TAPL6 | Thalassotaleaalgicola | PM>SA>PG | 2-6 | Exo | Mg2+(1 mM); Ca2+(1 mM); K+(1 mM) | Zn2+(1 mM); Fe2+(1 mM); Ni2+(1 mM) | 25/10.0 | 40 ℃, 60 min, remaining 20% | [46] |

| AlyRmA | Rhodothermus marinus | SA>PM>PG | 2-4 | Exo | Mg2+(1 mM); Ca2+(1 mM) | Cu2+(1 mM); Zn2+(1 mM); Ni2+(1 mM) | 70/8.0 | 70 ℃, 60 min, remaining 100% | [11] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).