1. Introduction

The use of digital tools in learning has been seized upon as a viable and effective approach to pedagogy in many universities and jurisdictions, even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a wholesale, if temporary, switch to digital learning across the globe [

1]. Many global north countries have universities whose entire portfolio is based online, and facilitated by digital tools, such as the Open University in the UK. Additionally, a significant majority of traditional campus-based universities now offer online courses and, following the global pandemic in particular, offer blended courses (a mixture of both on campus and online learning opportunities, within the same course), so much so that in the United Kingdom, the Office for Students (OfS – the regulator of higher education in England) has felt it necessary to produce clear guidance for universities on their regulatory obligations in regard to the use of blended learning and the rights of service users [

2].

However, it is clear that good quality, well considered digital learning has an established and potentially escalating place in Higher Education (HE), which has been exacerbated by the global pandemic. It is equally clear, though, that the spotlight should be firmly fixed on the rationale, efficacy and pedagogy of the decisions made in relation to the embrace of digital learning. Following the global COVID-19 pandemic, a cross-university team working under the auspices of the Research Institute for Social Mobility and Education (RISE) in the United Kingdom undertook an internationally focused piece of qualitative research to determine if there were key factors that led to successful digital learning in the Higher Education (HE) sector. Twenty-one key individuals with established expertise in digital learning were identified at twenty universities in six global north countries. Each of them was interviewed between 2022 and 2023, using discussion guides that were tailored to different university roles (e.g. lecturer, senior university manager).

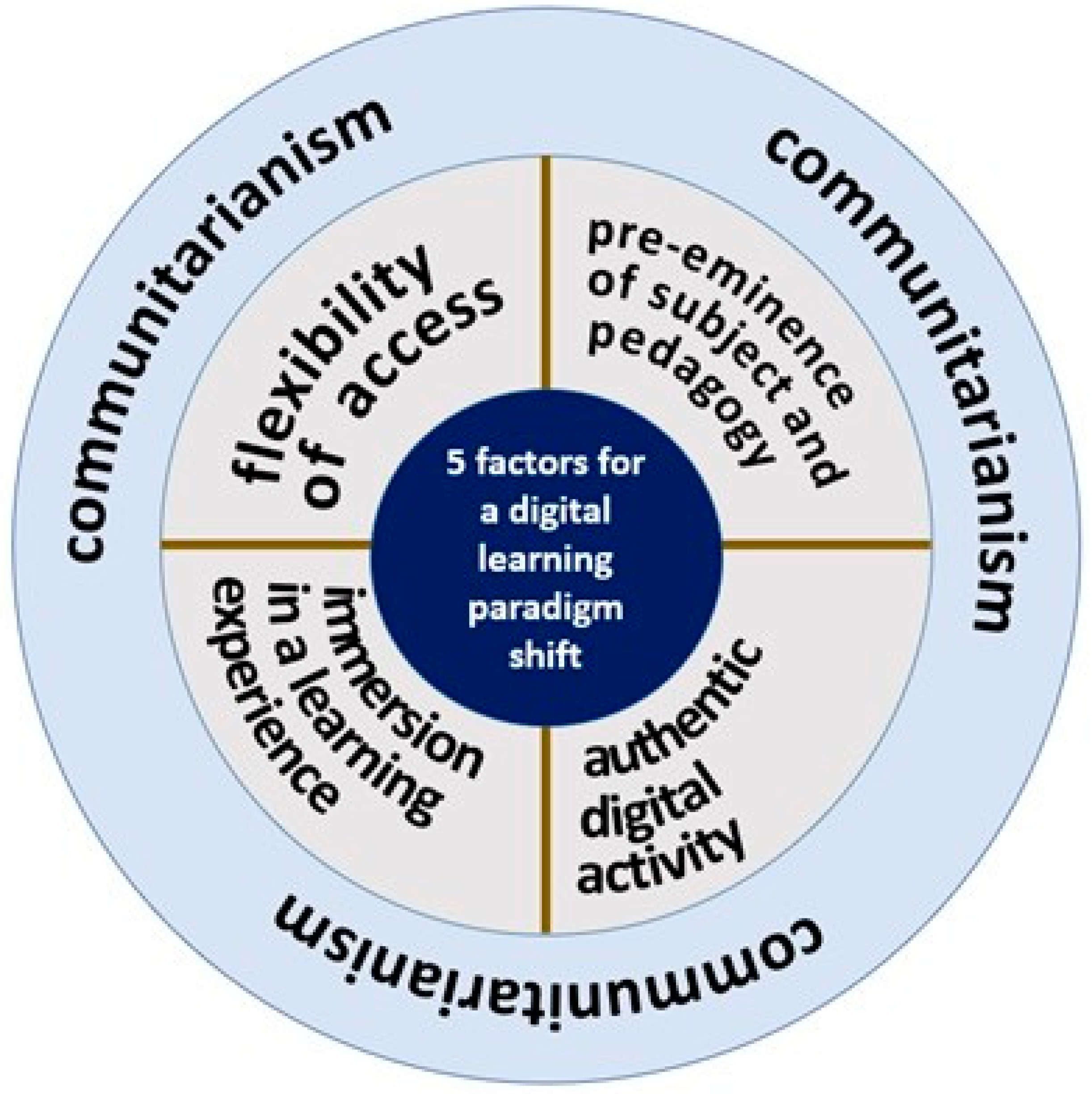

This paper presents the key findings of the study and applies a paradigmatic shift model to identify the five key elements to successful digital learning within universities globally that emerged from the study. These are:

Communitarianism;

The pre-eminence of subject and pedagogy;

Flexibility of access;

Immersion within a learning experience; and

Authentic digital activity.

We conclude the paper by tentatively suggesting that these elements, when taken together and self-consciously implemented as a set, may constitute the beginnings of a paradigm shift [

3] in the practice of digital learning in HE. This shift may well have been precipitated by the dislocation in learning in HE occasioned by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the transition undertaken by higher education institutions throughout the world [

4].

2. Digital Learning in UK Universities: Gravity Assist

In 2020, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK’s Secretary of State for Education commissioned a report which reviewed online teaching and learning in higher education. The report, written by Sir Michael Barber, was titled Gravity Assist: Propelling Higher Education Towards a Brighter Future (2021). Barber’s report was based on 52 interviews with digital pedagogy experts and a survey of 1,852 people (of which 1,285 were students).

Barber’s report highlighted the speed at which the move to online teaching and learning during the pandemic occurred in UK universities. By December 2020, 92% of students had moved to a form of online pedagogy – with video seminars, online lectures and lecture slides being placed online representing the most common ways in which students were taught. More innovative modes of teaching, learning and assessment – such as online masterclasses for music students and digitally simulated training for paramedics – also emerged. Barber notes that “the speed and scope of adaptation were extraordinary.” [

5] (p.4)

Among the interview respondents, Barber reports a consensus view that the innovation that the COVID-19 pandemic forced to occur will leave a lasting, positive change within UK higher education. But what are these benefits? Gravity Assist identifies them as: increased flexibility, personalised learning, increased career prospects, pedagogical opportunities and global opportunities.

These benefits are better evidenced in some cases than others and, as we discuss, our research better supports some of Barber’s claims than his own report. It is clear, for example, that digital pedagogy does offer what Barber terms ‘pedagogical opportunities’ – which he says is technology allowing educators to do more – but our interviewees gave more definitive examples of this than Gravity Assist offers. Less clear is how Barber concluded, within 12 months of these innovations taking place during the pandemic, that digital pedagogy presents increased career prospects when the evidence underpinning this heading includes claims such as students become self-directed learners and online learning can better reflect the workplace [

6] (p. 32). It is possible that digital pedagogy can do these things, and we reflect upon the latter point in response to one of our informants from an Australian university, but they are not a given simply because the technology is adopted – rather, the pedagogy must enable them.

So how are these benefits achieved? Barber rightly says that the conditions for good digital teaching and learning must be met. These conditions are outlined in the list below [

7] (p. 9), taken from the report, and there are some clear comparisons with the model we present in this paper (e.g. what Barber calls inclusion has parallels with our definition of communitarianism).

Barber’s model presents six components of successful digital pedagogy, which are:

Appropriate design of pedagogy, curriculum and assessment

Access to digital infrastructure

Develop digital skills necessary to engage

Technology is used strategically to enhance experience and outcomes

Inclusion for different student groups is embedded from the start

All of the five points above are contained within a consistent strategy

Our research finds that many of the elements of Barber’s model are consistent with what experts around the world believe represents best practice, but in some cases the report lacks the depth or the detail in particular areas. How, for example, should technology be used strategically to enhance experience and outcomes? Whilst we build upon Barber’s findings, our work is not simply an attempt to replicate his study at a later date, with greater benefit of hindsight and reflection. Barber’s work begins from a position of asking ‘what happened?’ and then offers some suggestions for improvement within this context. Our project, from the beginning, has asked ‘what should happen?’ in the context of achieving best practice in digital pedagogy.

3. Methods

The research team of academics on the project undertook individual semi-structured interviews following the development of a purposive sampling frame [

8], where only participants who had an established track record working digitally within HE prior to the global pandemic were considered. Twenty one individuals were identified globally: participants were based in the United States of America, Australia, New Zealand, Finland, Norway and the United Kingdom. These participants all held responsibility for digital learning in some respect, and included lecturers, staff development leaders, senior university managers, and digital technologists. Following the research design and data collection protocol being assessed for ethical suitability against both the criteria and spirit of the British Educational Research Association’s ethical guidelines [

9]. The project was launched, following a principle of radical collegiality [

10] within and amongst our global academic community members, foregrounding a commitment to equality and peer-learning (1999: 21), acknowledging in our ontology that we, as teachers, are in fact reciprocal learners [

11] (p. 22), and reaffirming our commitment to collegiality through democratic discourse [

12] (p. 25). The rationale for this approach was to allow the participants to interpret the research questions themselves and, utilising their exemplary knowledge, reveal their insights into successful digital learning. This would (and did) reveal a breadth of responses and perspectives, not limited by a pre-determined lens or framework. Our collegial approach was inspired by a passage from Merton [

13], who criticised approaches to research which discounted the ‘face value’ of participant statements, and tried to find new or ‘real’ meaning where the researcher “does not so much create a following as he ‘speaks for’ a following to whom his analyses ‘make sense,’ i.e., conform to their previously unanalyzed experience” [

14] (p. 219).

The interviews were conducted in a manner such that our participants would be “encouraged to reveal, through discussion, their ways of understanding a phenomenon, that is, to disclose their relationship to the phenomenon under consideration” [

15], to elicit the ‘rich’ detail necessary to fully explore the area of successful digital learning in HE. They were conducted online via a software platform that included recording and transcription facilities, with these data files collected from the primary research phase stored on a ‘Cyber Essentials accredited’ university network, secured by password and two-factor authentication protection.

The research team then utilised a six-stage thematic approach to coding the raw data, as promoted by Braun and Clarke [

16] to unearth a collective phenomenon and identify areas of common perception. The first stage involved familiarisation with the data via the verbatim transcription of each interview recording, with the second stage involving the generation of initial codes. The third stage required the formulation of themes from the generated codes, “a list of themes, a complex model with themes, indicators, and qualifications that are causally related” [

17]. In stage four, the themes were reviewed against the entire data set to establish key errors or omissions in the theme-creation phase. This, in turn, led to the development of five key areas of good digital practice. In stage five of the process, these themes were named and defined and, in stage six of the process, the team identified the “vivid and compelling extracts relating back to the original research questions” [

18] (p. 610). These ‘vivid and compelling extracts’ are discussed in the following section, as we introduce our five key elements to good digital learning in HE.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. A Five Factor Model of Good Digital Learning

The research undertaken revealed following analysis five clear themes within the data, pertinent to successful digital learning in higher education, which taken together form a visual depiction as seen below in

Figure 1.

Evidenced throughout the statements made by our participants was the necessity to create community within the pedagogy, both within the student body – but also the academic staff delivering the learning. Although this is not unique within literature, this is clearly an element of digital pedagogy that has still not fully manifested itself in the education population, as digital learning is still often undertaken in isolation. We have labelled these factors – of belonging, community, confidence etc. – as communitarianism. These are an essential underpinning for each of the other four elements that we have identified; it is for this reason that our model presents communitarianism as a ‘wrap around’ element rather than as a discrete segment. Within this creation of community, we identified a further four elements related to the design of digital pedagogical approaches. The first was around capitalising on the flexibility of access that digital tools bring, to allow choice and agency in the student body. The second related to the pre-eminence of subject and pedagogy and identified a tendency amongst many ‘pro-educational technology’ educators to use contemporary digital tools irrespective of their pertinence to the subject or efficacy in promoting learning. The third identified a need for authentic digital activity around the learning episode, noting that if an educator has developed a digital approach to delivery, then the activities (e.g. assessment) undertaken by the student body should be authentic to that digital approach and not simply a replication of the activities undertaken in a traditional class, lecture, or module. The final element of our model is to develop truly immersive learning experiences for learning. Whilst this does not necessarily mean the creation of virtual or immersive reality experiences, it does refer to creating deep, contextual learning opportunities rather than for instance superficial presentations and documents.

The following subsections will introduce each of the five elements in detail. Each sub-section follows the same structure: statement of key learning, examples to illustrate the finding, and a discussion of the theme.

4.2. The Five Elements

4.2.1. Flexibility of Access

Key learning: Digital approaches to learning – by their very nature – bring the potential for flexibility, so it would be ridiculous to not capitalise on that flexibility in digital learning. The device du jour currently seems to be the smartphone, so educators need to ask themselves how that device should be foregrounded in learning design approaches.

Frank, a UK-based informant who taught film and media production, discussed the benefits of flexible access to learning. He gave the example of having previously gathered students in a classroom space at the beginning of a term to demonstrate how equipment such as cameras work, but that some students did not need to apply these skills until weeks later and – by that time – had forgotten how to use the equipment. By moving towards a more flexible, digital approach to delivering this learning, though, the interviewee has been able to address this problem. He now produces brief YouTube videos, on a channel only accessible to his students, in which he demonstrates how to use each piece of equipment. Students can, and do, access the videos as and when they are needed to teach themselves, or refresh their understanding of, how to use the equipment they require. The interviewee noted that the views on a video increase at the same time a piece of equipment is borrowed from the University by a student. This, for Frank, confirmed that the videos are viewed in sync with the equipment being used. This builds upon and adds depth to the identification by many, such as Kukulska-Hulme & Traxler [

19] and Powell [

20] that flexible access is a key tool for the promulgation of education in our changing society.

Further, according to our participants, the notion of flexibility is multifaceted, but arguably revolves primarily around the flexibility of access (on the part of the student) and flexibility of planning and communication on the part of the educator. Meredith reminded us that ‘our content should be “on the go.” It should be flexible in that it can be accessed while the student is cooking at home or feeding their kids. So, we develop materials that fit in, and work in, your hand. We develop materials that can be downloaded at the student’s convenience, and then accessed when the mood takes them.’ This chimes with UNESCO’s 2011 educational policy, which according to Sophonhiranrak [

21] over a decade ago postulated the key role that mobile phone technology could play in education across the globe, precisely because of its flexibility and ubiquity. Two UK academics charged with developing a digital pedagogy strategy across their university told us that this flexibility extends to synchronous events, such as course meetings and tutorials. They argued that academics and administrators still tend to think in terms of timetables, workload planning, attendance and engagement, and annual assessment ‘windows.’ They posited that a truly digital curriculum should focus less on these managerial elements and more on the flexible and global potential of a well-considered digital approach.

Building on this notion of flexibility, Daisy, a professor in the United States, also argued for a flexible approach to communication. She passionately explained that many students can be intimidated by the communications routinely utilised by academics, such as email and video conferencing. For several years now she has utilised mobile communications (Slack) to develop a more conversational style to digital learning, explaining that:

“I know some people hate the sort of instantaneous nature of these kinds of communication methods, but for me, I’ve noticed that my students can easily just, you know, message me a quick question or comment, where they never would have dropped in my office in person and said this, or even sent me an email because it just felt too formal… there’s like this casual nature of it and they’re just like, hey, I had this random thought…”

4.2.2. Pre-Eminence of Subject and Pedagogy

Key learning: Learning should always be about the outcome and the subject, not the medium. Never use digital just because it’s new or in vogue. Forget about the technology, put the students, and what you want them to learn, first.

Erin, an Australian university lecturer, confirmed the sentiment that “content is king”, and that the content of the course should prevail over and above ‘showing off’ the technology, but she added the caveat that there should nonetheless be minimum standards of production. That is to say, the successful delivery of learning online – regardless of whether it is ‘good quality’ in pedagogical terms – is absolutely dependent upon suitable and reliable technology at both terminal points: the student end and at the teacher end. She provided a specific example in relation to sound quality and the importance of having a good quality microphone (particularly if students are not native speakers of the teacher’s language) to ensure that meaning is conveyed clearly. The interviewee also saw it as critical for the teacher to have a working understanding of how to use digital technology in their delivery to ensure these minimum standards of production, stating that, “It is no good saying ‘I am not a technology person’, you must be good with technology to be a good, modern academic.”

Whilst interviewees universally recognised the benefits of online teaching and learning, they were equally united in the view that the subject content needed to be foregrounded; technological abilities and opportunities should be used to deliver teaching content and enhance pedagogy, not included or inserted into teaching merely because it is available to the teacher. As one Australian participant said, teachers in higher education should not simply use online tools to demonstrate their own understanding of them, but because they help to deliver the objectives of the teaching.

This was supported by a senior manager (Pro Vice Chancellor) in a UK university whose role was to coordinate digital pedagogy across the institution. She explained that the role of her learning technologist team was to support academics to achieve their teaching objectives across their programmes, using the best digital platforms and opportunities available; this was not a case of the University’s management having a veto over course content, rather it was their attempt to support their academics and teachers to find the ‘best fit’ approaches for their modules.

4.2.3. Authentic Digital Activity

Key learning: The considered use of digital tools can in itself activate student learning, but not if those tools and approaches are simply replicating what has always been done but in a different medium. Digital tools should achieve something that other approaches cannot, so we should adapt our pedagogy by giving construct validity to our digital approaches – for instance, let’s assess using digital posters, blog authoring etc. Why deliver a module using innovative approaches and then assess using an essay or a timed exam?

Several informants emphasised the need for pedagogy to be adapted to the new online platform, taking into account the opportunities and challenges that moving to an online space presented. Central to this point was the need to design learning materials and course content afresh, rather than simply trying to replicate in-person teaching (especially traditional lectures) over Zoom or a similar platform. This finding echoed Tim Fütterer et al [

22] who observed that online teaching during the pandemic “ranged from students being left completely to their own devices” to being “passive listeners” to recorded lectures. By contrast, the study notes the importance of cognitive activation to high-quality learning. In this vein, a UK-based interviewee at a non-Russell Group university in North West England discussed how his teaching was designed around his ability to split screens when teaching a particular software package, demonstrating practical skills whilst also lecturing, and having students complete practical tasks during the course of the class (as a means of taking advantage of being at their own computers).

Another UK informant who was a senior manager within a London university discussed the challenge of convincing academics and teaching staff to engage in authentic digital activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. She said that academics often did not recognise that because they put a lot of effort into recording 50-minute-long lectures (simply replicating on camera what they would have said in an in-person lecture) that this did not necessarily equate to good, engaging online delivery. In this respect, she highlighted that it can sometimes take a period of trial and error, allowing teaching staff to find out for themselves what works and what does not in the context of their discipline, because some were “rigid” in their initial unwillingness to adapt to new ways of delivering their subject. There was, however, some recognition after experiencing online delivery that there are other, more appropriate styles of teaching online that make better use of technology and digital opportunities, rather than trying to replicate the in-person experience.

Whilst the key focus of the interviews was the delivery of teaching and learning online, several participants were keen to note the importance of assessing students in a way that matched how the course material had been delivered. Informants emphasised that it did not make sense to use new technologies and advanced digital platforms to deliver teaching and learning, only to then revert to more traditional, in-person methods of assessment at the end of the teaching. Their strong view was that assessment activity could (and should) also be designed in a way that breaks with convention and builds upon new technological opportunities.

This point was made by a senior learning technologist who has a university-wide digital transformation role at an Australian university which offers a traditional academic curriculum alongside a series of vocational programmes. The interviewee noted that it is a federal requirement for students at the institution on vocational programmes to gain work experience as part of their qualification and that, as a result, the university has built a work experience module into its courses. These modules have credits that count towards the final qualification. On these modules, the university re-creates tasks relevant to the different professions with which the vocational programmes align, so that assessments are based on real-world tasks that students might face in a workplace relevant to their career aims. These tasks are conducted online and students complete them within the workplace environment rather than a traditional exam hall. This is typical of the wider university culture at this institution, which the interviewee said has very few traditional exams and is instead focused on developing new, innovative forms of digital assessment.

Another interviewee, also based in Australia, whose thinking was broadly the same as this, did caution that alternative ‘back up’ assessment options were needed for students who did not have adequate technology at home or who were based in countries, like China, where they faced censorship and online restrictions.

This element of our model links seamlessly with the findings of the Gravity Assist research, which stated that, “[t]echnology cannot just be bolted onto existing teaching material. There needs to be a focus on how students learn. Instead of blunt attempts to replicate in-person settings, learning outcomes should drive how technology is used” [

23] (p. 10).

4.2.4. Immersive Learning Experiences

Key learning: The 'setting' of the learning can and does activate an emotional response and connection to the learning matter, therefore there is a place for well-considered extended reality approaches to add value to learning. However, on a smaller scale, we need to think about the depth of provision provided and the extent to which we can immerse a student in the subject. For instance, when learning digitally, are all the resources required to learn a topic easily and immediately accessible by the student?

Ingrid, a Norwegian lecturer spoke with passion about the need to immerse the student within a learning experience. Touching on the thinking of de Freitas and Neumann (2009), she suggested that ‘the setting [of the learning] activates the emotions and feelings about the subject.’ She argued that, in the same way that educators might use real-world experiences such as visits and guest speakers, digital pedagogues should use technology to provide a corresponding approach and experience. She felt that using immersive reality could provide a suitable vehicle for activating student learning and creating what she termed ‘active learning environments.’ This notion was built upon by Mika, a digital technology lead in a large Finnish university who declared that, in his view, the next major impact on learning practice would come from immersive or virtual reality. This view chimes with the writing of Frehlich [

24], Kukulska-Hulme & Traxler [

25], and Aukstakalnis [

26] amongst many others. Karen, an Associate Dean at a large Australian university linked her thinking to that of Laurillard, when she told us that, ‘it takes us back to the point that Diana Laurillard makes, she wrote about vicarious perception where she’s clear that you can’t take a cohort of students to the lip of a volcano. But you can show them what it’s like and they get everything except for the heating and the smell.’ Though Laurillard [

27] (p. 100) was discussing the power of well-considered video artefacts, this only served to underscore our suggestion of the need for immersion as a tool for simulation and the potential learning value of vicarious perception.

The concept of ‘embodied cognition’ was replete in our research and connects effortlessly to our immersive learning experiences concept. Embodied cognition is the notion that the actions and movements of the body, i.e., how the body interacts with the environment around it, actually has an impact on how we as an organism learn and adapt new knowledge. The theory suggests that how the body experiences something will add an additional dimension of sensory input strengthening the brain’s ability to process new information. Essentially, according to embodied cognitivists such as Shapiro [

28] or Friston [

29] the interactions of the body have an influence on how we transfer between working memory and long-term memory - so learning is connected to our bodily experience.

However, the notion of immersive learning experience does not necessarily extend to the need for the development of virtual or immersive reality learning artefacts. Very practical suggestions were offered by our participants, who reminded us that when a student is undertaking digital studies, it is vitally important that all their required materials, opportunities for collaboration, and any other pertinent learning artefacts are available immediately to the student, without the need for switching platforms, additional log-ins, or having to search for additional information. In essence, even on a traditional two-dimensional screen, the student should be able to immerse themselves in the learning experience, with distraction and ‘fuss’ designed out of the process, as far as possible.

4.2.5. Communitarianism

Key learning: This theme came up in every single interview, to different extents. The key takeaway from this theme was that good digital learning should have at least an element of the human touch; human contact both with the tutor and amongst the student community. Key notions included relationship building, foregrounding synchronous approaches for building social relationships within the learning experience, and the importance of creating presence and a sense of community.

The importance of communitarianism, as we have labelled it, is best summarised by Meredith, the leader of a large suite of online courses at UK university:

“Most important? I think it's the human side of things, that human element. We miss the human touch when it isn’t there. It's important to put a face to a name, to put a voice to a name. And no matter how cutting-edge technology becomes, I think the human element still prevails.”

Although the label ‘communitarianism’ - argued by ten Have and Patrᾶo Neves [

30] to have first been used by Barmby in 1841 - was selected by the research team at stage five of the analysis, rather than being cited explicitly in interview, this theme was prevalent to some extent in every interview undertaken in a way which reflected, without fail, the sentiment of Meredith’s words. Key terms included notions such as relationship building, humanity, social relationships, and developing a feeling of community. This is not a new conception. Coaplen et al [

31] for instance linked this argument to Etienne Wenger’s seminal work on social learning but, in our study, the focus of our participants seemed – perhaps as a result of working through the global pandemic – to be more closely related to the feeling of belonging, friendship, of community, and the notion that learning needs a ‘human touch,’ in order to help learners to locate themselves as motivated and cemented within the learning, rather than the more common exploration of the potential benefits to cognition that a social element can provide. Basic issues such as students having the social confidence to turn on their cameras and speak up in front of one another were cited as examples of why a sense of community and belonging is important.

Tabatha, a lecturer and active researcher in digital learning at a university in the United States, told us that ‘you cannot underestimate the power of the tutor’s presence, and their human touch,’ whereas Daisy, a lecturer and researcher at a different US university, reminded us of the implicit formality of many digital communication forms. Daisy expressed in her interview examples of the unintended pressure that the receipt of an email from a university lecturer may cause in a student. whereas she had adopted an appreciation for ‘the importance of synchronous, chatty communication. Use informal contact, use smileys and be casual,’ because, as she explained, this is how a conversation outside a lecture theatre or in the dining hall would be conducted. Her key observation was that we must foreground synchronous approaches to communication to build social relationships, despite the acknowledgement that the digital tools for communication employed by many universities do not lend themselves naturally to conveying such messages, unless staff are mindful and imaginative about their use.

Liv, a professor in a Norwegian university, offered practical advice in this area, suggesting that to maintain community, group sizes should be kept reasonable and manageable, because ‘digital learning is not about getting more for less, it isn’t about being more efficient, it is about learning!’

The power of digital to create opportunities and space for human contact was also examined, with Mika, a digital learning manager in a Finnish University, stating passionately that ‘moving forwards, the big ideas such as AI should be used to automate the things that CAN be automated, in order to free up human time for the things that really shouldn’t be automated.’

The key concern from this emerging theme was that in the view of our participants, good digital learning should have a considered element of human presence, whether that be purposeful personal contact with the tutor, or organised opportunities for socialisation and collaboration within the student community, even where these opportunities are delivered digitally.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to compare how the formation of social relationships differed between two different cohorts of students: those whose first year of university was experienced on campus and those whose first year was delivered remotely, having started their studies during lockdown. An Australian academic, who teaches at a university where most programmes are delivered on a hybrid basis, observed that online seminar/small group delivery among those students whose first year had been on campus flowed more easily and had greater social interaction; the seminars of those whose first year was delivered online tended to lack the same social dynamic.

The interviewee put this down to students in the former cohort having the opportunity to develop social relationships (i.e. friendships and social confidence) in person – which eliminated awkwardness or unfamiliarity – whereas the latter cohort had not had this. Her recommendation for future years, on her own programme but more generally in relation to hybrid teaching, was that it is optimal to have first-year delivery in person so that social bonds can form and then deliver subsequent years’ teaching remotely, building upon these relationships. Her thinking reflects that of Claudia Ghergel, Shoko Yasuda and Yosuke Kita [

32] whose work discusses students’ preferences for at least some access to in-person campus experiences alongside online provision and for social interaction more generally. Their study also found some evidence to support the claim that “more opportunities for social interaction during class were associated with more emotional and behavioural engagement, and with more self-directed study time” [

33]. This is commensurate with our view that communitarianism is foundational to online learning.

5. Final Thoughts, Conclusions, and Cementing a Paradigm Shift for Transformative Digital Pedagogy in HE

We believe – and the participants that contributed to our research believe – that digital pedagogy has the agency to transform learning in the university sector for the better. As professional educators, we need to be mindful that although digital learning may not be the best fit for all students, all situations, and all subjects, it will be the most appropriate, engaging, and effective approach for some students, in some situations and in some subjects. For this reason alone, we are duty-bound to ensure that, for those students, we include a strong working knowledge of digital learning in our academic toolkit and the purpose of this article has been to enhance that knowledge.

Our research enabled us to determine our five-piece model, which provides a blueprint for curriculum designers to utilise when developing new episodes of digital learning in the university sector, or at minimum provides conversation prompts and a framework around which to discuss the pedagogical requirements of good digital learning. We stand by this but, as we reflect on the model that we have just described and the testimony of our interviewees in a variety of countries and contexts, we wonder whether there is something deeper happening here. The integration of these five elements and the emergence of communitarianism as a key theme that binds the others together, prompts us to question if there is a more profound shift occurring in the practice of digital pedagogy in higher education. This is particularly pertinent in the post-COVID era, and we suggest that this may be akin to what Thomas Kuhn referred to as a paradigm shift.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn [

34] argued that a paradigm shift is a fundamental change in the basic concepts and practices of a scientific discipline. Although Kuhn focussed on scientific practice, the concept is now commonly applied across a range of disciplines where there has been a profound change in both the understanding of key ideas and modifications that revolutionises practice. Kuhn identifies four phases in the development of a paradigm shift:

Normal science – This is when a dominant paradigm that is characterised by a set of commonly accepted theories and ideas that puts boundaries around what is possible and rational to do.

Extraordinary research – When enough significant anomalies have accrued against a current paradigm, the scientific discipline is thrown into a state of crisis.

Adoption of a new paradigm – When new practices begin to be adopted and gain influence by explaining or predicting phenomena much better than before.

Aftermath of the scientific revolution – In the long run, the new paradigm becomes institutionalised as the dominant one.

We do not want to overclaim here, but we do believe that contained in our five factor model are significant differences in approach, style and substance than has traditionally been the case. This is particularly so with ‘communitarianism’ where we claim that effective digital learning should have an element of the human touch to it. In other work [

35] we have used Habermas’ tri-paradigmatic schema (Instrumental, Phenomenological and Critical) as a way of explaining the shortcomings of various policies and practices in education. Using this framework, we would argue that the Gravity Assist model was conceived of and operates within the top-down or instrumental paradigm. On the other hand, we suggest that our ‘five elements’ model is located within the Critical paradigm, in so far as it serves to emancipate and empower the learner. This is well evidenced in the testimony we have reported from our interviewees.

There is another factor to be considered here. This research project was designed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic but the interviews took place in the wake of it. The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic almost instantaneously changed life for just about everyone globally. In most countries of the world, economic discipline was abandoned, businesses closed, staff were furloughed or asked to work from home, and so on. The challenge for educational leaders is knowing how to respond to such a cataclysmic event in a morally purposeful, authentic and principled way. It is now clear that conventional strategies are unable to meet the post-COVID challenge. Ironically the COVID hiatus gives us the opportunity, as presaged in our interviews, to create an educational future that delivers on the moral purpose most educators and leaders in higher education (though also schools) have for their students.

Pasi Sahlberg [

36] expresses the challenge in the following way. Disruption leads to one of three scenarios:

Scenario 1: Adaptation which includes shrinking budgets, downsizing services, new standardisation and more online delivery through policy-driven change.

Scenario 2: Status quo which represents survival, fixing the damage and catching up.

Scenario 3: Transformation which represents investing in public education, diversifying schools, more flexibility and trust in teacher-led and school-led change.

The disruption in this case is, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic. That is the given: the question is how do we respond? Unfortunately, as we survey the world’s education systems they seem to be responding by either downsizing and reducing budgets (Scenario 1) or by trying to maintain the status quo (Scenario 2). We are with Pasi Sahlberg, in believing that we should be courageous by using this unprecedented event to make a paradigm change that embraces diversity and achieves equity through excellence (Scenario 3).

Given that our sample is international and that the five-element model has emerged inductively from the date we gathered we are reasonably confident that it has some generalisable power. If the model contains the seeds of a paradigm shift, what is required for the shift to be sustained? This leads us into the field of organisational change, which is something our respondents also commented on. Abbas [

37] defines sustainable organisational change as the ability of an organisation to continuously adapt and improve its processes in order to make lasting change and have a competitive edge. Sustainable change involves not only implementing proposed change but to sustain for long period of time. In his paper, Abbas also articulates the 5 pillars of sustainable organisational change. We briefly describe each pillar and demonstrate its relevance for digital learning in HE with an illustration from our interviews.

This research utilised primary interviews with 21 established digital pedagogues in six countries to learn from their practical and intellectual experiences, to determine any fundamental lessons for integrating and embracing digital learning into higher education. Although the original purpose of our research was not to create a model, our analysis revealed five key elements that can contribute to successful digital learning. These are presented in the diagram below, our model of 5 elements for a digital learning paradigm shift and we explored the five elements previously within this paper.

The elements identified within our analysis were flexibility of access, the pre-eminence of subject and pedagogy, authentic digital activity, immersive learning experiences, and communitarianism. The four ‘inner’ elements were not deemed to be dependent on one another, or interconnected in any way, hence there is not a particular ‘way’ or ‘approach’ required to ‘read’ the model. However, it was also clear that the notion that we termed communitarianism, or the requirement to create a feeling of community and belonging amongst the participants in good digital learning seemed to encompass or even pre-empt everything else, hence our design-decision to display communitarianism as a wrap-around, enveloping the remainder of the model.

We advocate this model as a consideration for both educators and faculties whose ambition is to develop successful digital pedagogy within the university sector, but further position this model as a pivotal catalyst for a digital paradigm shift in university practices. University education is one that is largely based on tradition and history, it has a zeitgeist that in Kuhnian terms, represents the normal science (1962) of university pedagogy. We do not consider - in this paper - the potential consequences for higher education of failing to acknowledge the paradigm shift that the sector currently sits on the precipice of, but rather we embrace the potential for positive change and enhancement that the real and considered emergence of digital learning brings global higher education, and celebrate the opportunity that we as educators now have for the adoption of a new paradigm of university learning.

References

- Burki, T. K. (2020). COVID-19: Consequences for higher education. The Lancet Oncology News, 21(6), 758.

- OfS (2022). Blended learning and OfS regulation. O: UK.

- Kuhn, T. (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions 2nd Ed. International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, Vol2(2).

- Alon, L.; Sung, S.; Cho, J.; Kizilcec, R.F. From emergency to sustainable online learning: Changes and disparities in undergraduate course grades and experiences in the context of COVID-19. Comput. Educ. 2023, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OfS (2021). Gravity assist: propelling higher education towards a brighter future. UK: Office for Students. Available at: https://ofslivefs.blob.core.windows.net/files/Gravity%20assist/Gravity-assist-DTL-finalforweb.

- OfS (2021). Gravity assist: propelling higher education towards a brighter future. UK: Office for Students. Available at: https://ofslivefs.blob.core.windows.net/files/Gravity%20assist/Gravity-assist-DTL-finalforweb.

- OfS (2021). Gravity assist: propelling higher education towards a brighter future. UK: Office for Students. Available at: https://ofslivefs.blob.core.windows.net/files/Gravity%20assist/Gravity-assist-DTL-finalforweb.

- Gray, D. (2014). Doing research in the real world. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- BERA (2018). Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research (4th Ed). London: BERA.

- Fielding, M. Radical collegiality: Affirming teaching as an inclusive professional practice. Aust. Educ. Res. 1999, 26, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, M. Radical collegiality: Affirming teaching as an inclusive professional practice. Aust. Educ. Res. 1999, 26, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, M. Radical collegiality: Affirming teaching as an inclusive professional practice. Aust. Educ. Res. 1999, 26, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. (1949). Social theory and social structure. Toward the codification of theory and research. Illinois: The Free Press of Glencoe.

- Merton, R. (1949). Social theory and social structure. Toward the codification of theory and research. Illinois: The Free Press of Glencoe.

- Bowden, J. (2000). The nature of phenomenographic research. In: J. Bowden & E. Walsh, Phenomenography. Melbourne: RMIT University Press.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. ( 3(2), 77–101. [PubMed]

- Boyatzis, R.E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. London: SAGE Publications.

- Gray, D. (2014). Doing research in the real world. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Kukulska-Hulme, A. & Traxler, J. (2020). Design principles for learning with mobiles. In: H. Beetham & R. Sharpe. Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Powell, P. (2023). Strategic models for distance education. In: L.Amrane-Cooper, D.Baume, S.Brown, S.Hatzipanagos, P.Powell, S.Sherman & A.Tait. Online and distance education for a connected world. London: UCL Press.

- Sophonhiranrak, S. Features, barriers, and influencing factors of mobile learning in higher education: A systematic review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fütterer, T.; Hoch, E.; Lachner, A.; Scheiter, K.; Stürmer, K. High-quality digital distance teaching during COVID-19 school closures: Does familiarity with technology matter? Comput. Educ. 2023, 199, 104788–104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OfS (2021). Gravity assist: propelling higher education towards a brighter future. UK: Office for Students. Available at: https://ofslivefs.blob.core.windows.net/files/Gravity%20assist/Gravity-assist-DTL-finalforweb.

- Frehlich, C. (2020). Immersive learning. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Kukulska-Hulme, A. & Traxler, J. (2020). Design principles for learning with mobiles. In: H. Beetham & R. Sharpe. Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Aukstakalnis, S. (2017). Practical augmented reality. USA: Pearson Education.

- Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking university teaching. 2nd Ed. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Shapiro, L. The Embodied Cognition Research Programme. Philos. Compass 2007, 2, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, Karl. (2011). Embodied Inference: or “I think therefore I am, if I am what I think”. The Implications of Embodiment: Cognition and Communication.

- ten Have, H., Patrão Neves, M. (2021). Communitarianism. In: Dictionary of Global Bioethics. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Coaplen, C.J. , Tonise Hollis, E., & Bailey, R. (2014). Going beyond the content: building community through collaboration in online teaching. a: The Researcher.

- Gherghel, C.; Yasuda, S.; Kita, Y. Interaction during online classes fosters engagement with learning and self-directed study both in the first and second years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Educ. 2023, 200, 104795–104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gherghel, C.; Yasuda, S.; Kita, Y. Interaction during online classes fosters engagement with learning and self-directed study both in the first and second years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Educ. 2023, 200, 104795–104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, T. (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions 2nd Ed. International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, Vol2(2).

- Hopkins, D. (2022) School Improvement: Precedents and prospects In: C S E LEADING EDUCATION SERIES, No 12, 22. 20 August.

- Sahlberg (2022) Understanding equity in education. Scan. Vol.41(6). [online] Available at: https://pasisahlberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Pasi-SCAN-article-1-Aug-2022. 20 March.

- Abbas, T. (2020) Sustainability Development in Education: Empirical Evidence and Discussion about Authentic Leadership, Religiosity Commitment. In: International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. 1: Vol.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).