1. Introduction

The rapid digital transformation in higher education has created significant challenges, requiring students to adapt to dynamic and sustainable learning environments. Globally, 85% of universities have adopted digital platforms post-COVID-19, while in Indonesia, 78% of students report heightened stress during the transition to online learning [

1,

2]. To ensure long-term educational sustainability, student resilience, defined as the ability to adapt positively to academic challenges, has become essential for academic success [

3,

4]. Resilient students are better equipped to handle stress, adapt to technological changes, and sustain motivation [

5,

6]. However, fostering resilience requires support through risk management, digital literacy, and modern learning environments that promote inclusive and sustainable education systems.

Risk management involves identifying and mitigating risks that disrupt learning, such as cybersecurity issues and technological failures [

7]. Effective strategies enable institutions to maintain learning continuity during disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic and equip students to navigate uncertainties [

8,

9]. From a sustainability perspective, risk management frameworks provide essential tools for students to develop resilience, ensuring that education remains accessible, stable, and adaptive in a rapidly evolving digital landscape [

10,

11,

12].

Digital technology literacy, the ability to effectively use and integrate digital tools, is another critical factor [

13,

14,

15]. Students with high digital literacy adapt better to hybrid learning, engage more effectively with digital platforms, and utilize resources efficiently [

16,

17,

18]. This skill not only facilitates learning but also strengthens resilience by enabling students to overcome technological barriers while fostering a digitally sustainable learning environment [

14,

19].

A modern learning environment moderates the relationship between these factors and resilience. It combines innovative teaching strategies, such as personalized learning, with robust digital infrastructure to create adaptive ecosystems [

20,

21]. Interactive approaches enhance engagement, while accessible technology ensures seamless integration of learning tools [

22,

23]. A well-developed digital learning ecosystem contributes to educational sustainability by enhancing long-term adaptability and inclusivity. Despite advancements, research integrating risk management, digital literacy, and modern learning environments to foster resilience remains limited [

24,

25]. Most studies address these factors in isolation, neglecting their collective impact in supporting students' adaptability in higher education [

16,

26].

This study addresses this gap by analyzing the relationships between risk management, digital technology literacy, and student resilience, with modern learning environments as a moderating variable. Using a quantitative approach and structural equation modeling, this research provides empirical insights into how institutions can enhance resilience through sustainable digital adaptation strategies. The findings contribute theoretically by expanding understanding of resilience in digital learning and practically by offering recommendations for creating long-term adaptive and sustainable educational ecosystems [

27].

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Risk Management

Risk management in higher education refers to systematic efforts to identify, assess, and mitigate risks that can disrupt academic processes, especially in the digital era [

28,

29,

30]. This includes addressing technological risks, such as cybersecurity threats, data breaches, and system failures, which have become prevalent with the increasing reliance on digital platforms [

31,

32,

33]. From a sustainability perspective, effective risk management ensures not only short-term crisis mitigation but also the long-term stability and adaptability of digital learning environments. The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) framework emphasizes the need for integrating risk management into educational strategies to ensure resilience and sustainable learning ecosystems [

34]. Studies have highlighted that institutions with comprehensive risk management systems are better equipped to navigate crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, minimizing disruptions and enhancing the sustainability of educational operations [

35,

36].

At the individual level, risk management plays a vital role in equipping students with tools to cope with uncertainties. For instance, structured support systems that identify academic risks, such as workload imbalances or resource shortages, empower students to develop resilience and maintain motivation [

37,

38]. Research shows that when students are provided with clear frameworks to manage risks, they exhibit higher engagement and better academic outcomes [

39,

40]. Furthermore, effective risk management promotes mental well-being, as students feel more secure and supported in unpredictable environments [

41,

42,

43]These findings underscore the importance of integrating risk management not only at the institutional level but also as a critical component of student development in the digital learning era. By fostering an adaptive risk management culture, higher education institutions contribute to a more sustainable and inclusive digital education system that ensures long-term learning continuity and institutional resilience.

2.2. Digital Technology Literacy

Digital technology literacy, defined as the ability to effectively use, evaluate, and integrate digital tools, is a foundational skill for success in modern higher education [

44,

45]. It encompasses competencies such as navigating digital platforms, utilizing educational technologies, and critically assessing digital information [

46,

47]. As digital learning environments become the norm, especially post-COVID-19, institutions increasingly rely on students’ technological literacy to ensure meaningful engagement and academic success [

48,

49]. From a sustainability perspective, fostering digital literacy is essential for developing long-term adaptive learning strategies that ensure educational resilience and inclusivity. Studies have found that students with strong digital literacy demonstrate higher adaptability to hybrid and online learning systems, improved academic performance, and greater autonomy in learning [

49,

50,

51]

Moreover, digital literacy supports sustainable learning innovation by enabling students to optimize the use of tools such as virtual labs, collaborative platforms, and adaptive learning technologies [

52]. These skills also enhance resilience, as students with high digital literacy are better equipped to overcome challenges related to remote or hybrid learning environments [

53,

54]. However, disparities in access to digital resources and skills highlight the importance of institutional support in fostering equitable digital literacy development [

55,

56,

57]. By integrating structured interventions and digital literacy programs, higher education institutions contribute to a more sustainable and inclusive educational framework, ensuring equal opportunities for all students in the evolving digital landscape. Recent frameworks emphasize the need for structured interventions to bridge digital divides and equip students with advanced digital competencies for academic and professional success [

58,

59]

2.3. Modern Learning Environment

A modern learning environment (MLE) integrates innovative teaching strategies and advanced digital infrastructure to create sustainable, dynamic, engaging, and adaptive ecosystems for students [

60,

61]. This concept emphasizes personalization, interactivity, and accessibility, ensuring that students can thrive in hybrid or fully digital learning settings [

62,

63]. From a sustainability perspective, MLEs contribute to long-term educational resilience and inclusivity by fostering adaptable learning systems that accommodate diverse student needs. Personalized learning approaches, such as adaptive learning technologies and student-centered pedagogies, have been shown to significantly enhance student engagement and academic outcomes [

62,

64,

65]. Additionally, interactive components, including virtual labs and collaborative platforms, foster active participation and critical thinking [

66,

67,

68,

69]. These innovations promote sustainable learning ecosystems by equipping students with the digital skills and cognitive flexibility needed for lifelong learning and professional adaptation.

The digital infrastructure within MLEs, including reliable internet connectivity, high-quality learning management systems, and user-friendly tools, is a critical component of its success [

16,

55]. A robust infrastructure ensures seamless integration of educational technologies and minimizes disruptions that could hinder learning [

70]. Recent studies indicate that institutions with well-developed MLEs report higher levels of student satisfaction, resilience, and performance compared to traditional environments [

71,

72,

73]. Furthermore, sustainable MLEs enable inclusivity by providing access to learning for diverse student populations, including those in remote areas [

62,

71,

74,

75]. As higher education continues to evolve, the development of sustainable MLEs is essential for fostering long-term educational innovation, digital equity, and institutional resilience in the digital era.

2.4. Student Resilience

Student resilience is the capacity to adapt positively to academic challenges, demonstrating persistence, flexibility, and motivation in the face of stressors [

76,

77,

78]. In the context of higher education, resilience enables students to navigate the complexities of digital learning, such as abrupt transitions to online platforms, demanding workloads, and technological disruptions [

16,

79,

80]. From a sustainability perspective, resilience plays a crucial role in fostering long-term student adaptability and well-being, ensuring that learners can thrive in rapidly evolving digital environments. Research has shown that students with high resilience are more likely to achieve better academic outcomes and experience lower levels of stress compared to their peers with lower resilience [

77,

78]. Furthermore, resilient students tend to actively seek solutions to problems, maintain focus on their goals, and leverage available resources effectively [

77,

78,

81,

82]. By fostering resilience, higher education institutions contribute to the sustainability of academic achievement, mental health, and digital inclusion among students.

The development of student resilience is influenced by both individual and environmental factors. At the individual level, traits such as self-efficacy, emotional regulation, and adaptive thinking play a critical role [

83,

84]. At the environmental level, supportive learning ecosystems, including access to digital tools, collaborative learning opportunities, and structured guidance, significantly enhance resilience [

16,

85]. Sustainable educational environments prioritize resilience-building frameworks by integrating adaptability and problem-solving skills into higher education curricula, ensuring students are equipped for lifelong learning and continuous professional development. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of integrating resilience-building frameworks into higher education curricula, focusing on fostering adaptability and problem-solving skills in students [

86,

87]. As higher education continues to embrace digital transformation, fostering sustainable student resilience becomes essential for creating inclusive and future-ready learning environments that promote equity, mental well-being, and long-term academic success [

88,

89,

90].

2.5. Hypothesized Model

2.5.1. Risk Management and Student Resilience

Risk management plays a critical role in enhancing student resilience by providing a structured approach to mitigating academic and environmental uncertainties [

28,

91,

92]. From a sustainability perspective, effective risk management not only supports students in overcoming immediate challenges but also contributes to the long-term stability of digital education ecosystems. Institutions that implement robust risk management strategies, such as proactive identification of challenges and contingency planning, create a stable foundation that supports students in navigating academic pressures [

93,

94,

95]. By fostering a risk-aware academic culture, higher education institutions can enhance student resilience in a way that ensures sustainable learning continuity and institutional adaptability.

On an individual level, exposure to risk management frameworks helps students develop problem-solving skills and emotional regulation, which are essential components of resilience [

96,

97,

98]. Research indicates that risk management not only reduces stress but also fosters adaptability by equipping students with the tools to handle unforeseen disruptions, such as transitions to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic [

49,

99,

100]. A well-integrated risk management approach supports sustainable educational resilience by ensuring that students and institutions can adapt to technological and environmental uncertainties while maintaining learning equity. Furthermore, institutional policies addressing data privacy and cybersecurity risks also contribute to a safer and more predictable learning environment, which reinforces student confidence and resilience [

101,

102,

103].

H1: Risk management has a significant positive effect on student resilience.

2.5.2. Digital Technology Literacy and Student Resilience

Digital technology literacy is a vital competency for fostering student resilience in modern education. It encompasses the ability to effectively navigate, evaluate, and utilize digital tools, which empowers students to overcome academic challenges and adapt to evolving learning environments [

18,

104,

105]. From a sustainability perspective, digital literacy is not only essential for immediate academic success but also for long-term adaptability and sustainable learning practices. Students with high levels of digital literacy demonstrate greater adaptability, engagement, and academic performance, particularly in hybrid and online learning settings [

49,

104,

106]. By equipping students with digital competencies, higher education institutions contribute to the sustainability of knowledge transfer, workforce readiness, and inclusive access to education.

This literacy also enhances problem-solving skills by enabling students to efficiently access resources, collaborate in virtual spaces, and manage technological disruptions [

14]. Sustainable digital literacy frameworks ensure that students can continuously develop their competencies, reducing educational inequalities and fostering lifelong learning. Moreover, digital literacy has been linked to lower levels of academic stress and higher levels of confidence, as students feel better equipped to handle the demands of digital education [

18,

104]. As digital tools become integral to education, fostering technological literacy has become essential for building resilience in students navigating unpredictable academic landscapes [

25,

54]. Integrating digital literacy into higher education curricula ensures that students develop sustainable digital skills, enhancing their long-term resilience and capacity to thrive in rapidly evolving technological environments.

H2: Digital technology literacy has a significant positive effect on student resilience.

2.5.3. Modern Learning Environment as a Moderating Variable

A modern learning environment (MLE) plays a crucial moderating role by shaping how institutional and individual factors influence student outcomes. From a sustainability perspective, MLE contributes to long-term educational resilience and digital equity by ensuring that risk management and digital technology literacy effectively enhance student adaptability. MLE combines innovative teaching strategies and advanced digital infrastructure, fostering an adaptive ecosystem that enhances the effectiveness of risk management and digital technology literacy [

14,

70]. By integrating sustainable learning design, personalized learning approaches, such as adaptive technologies and interactive tools, amplify the impact of risk management by reducing stress and creating a supportive environment for students [

65,

107]. Similarly, well-integrated digital infrastructure, including reliable connectivity and intuitive platforms, strengthens the relationship between digital technology literacy and resilience by enabling seamless engagement with educational resources [

53,

108]. These features make MLE a critical component in fostering sustainable education systems that bridge gaps between institutional initiatives and individual student outcomes.

The moderating effect of MLE is especially significant in environments undergoing digital transformation. A robust MLE not only mitigates barriers to accessing technology but also enhances the adaptability of students by supporting flexible learning approaches [

8,

16,

62,

109]. Institutions with high-quality MLEs contribute to sustainable digital learning ecosystems by providing equitable access to technology and fostering continuous engagement in evolving educational landscapes. For instance, institutions that offer collaborative virtual platforms and structured guidance enable students with varying levels of digital literacy to perform better and develop resilience [

110,

111]. Conversely, poorly implemented MLEs may hinder the positive effects of risk management and digital literacy, underscoring the importance of their quality and accessibility [

14,

70]. By ensuring sustainable and inclusive learning environments, higher education institutions can maximize the role of MLEs in supporting long-term student success and institutional resilience.

H3: Modern learning environment moderates the relationship between risk management and student resilience, such that the relationship is stronger in high-quality modern learning environments

H4: Modern learning environment moderates the relationship between digital technology literacy and student resilience, such that the relationship is stronger in high-quality modern learning environments.

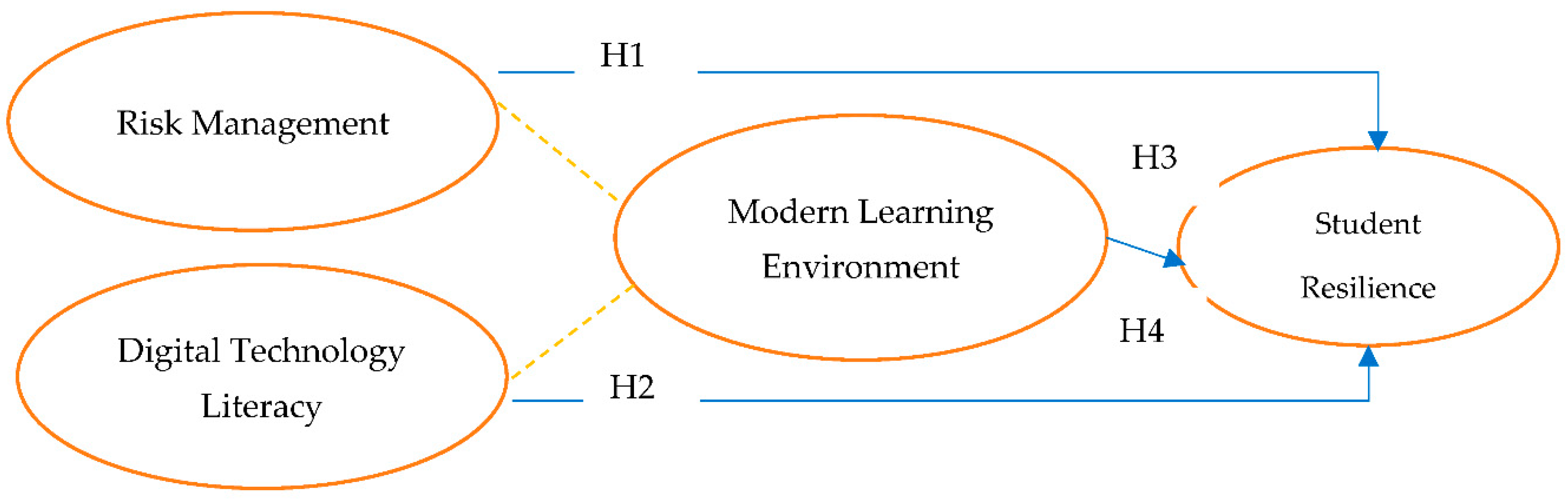

The model framework is shown in Figure 1

3. Research Methods

3.1. Profile Responden

A total of 475 Indonesian university students from various regions and study programs participated in this study, providing a relevant empirical foundation to explore the relationship between risk management, digital technology literacy, modern learning environments, and student resilience. From a sustainability perspective, understanding student demographics is essential for designing inclusive and adaptive education systems that support long-term learning resilience. The gender composition revealed a dominance of female students (62.3%) compared to male students (37.7%), reflecting a growing trend of female participation in higher education. This dominance was particularly evident in the field of Economics and Business (89.5%), indicating female openness to technology-based learning innovations and their adaptability to academic and professional challenges in the digital era. These findings highlight the importance of ensuring equitable access to digital education resources to sustain gender-inclusive learning environments.

The majority of respondents were aged between 20–22 years (58.3%) and 17–19 years (33.3%), representing the characteristics of active undergraduate students in a critical phase of academic development. Most respondents were in their 5th–6th semester (40.2%), indicating a mature academic experience suitable for understanding the challenges and opportunities of innovation-driven learning. A significant number of first- and second-semester respondents (36.2%) highlighted that technology-based learning has become an essential component of the academic experience for new students. This demographic distribution reinforces the need for sustainable digital learning strategies that accommodate students at different academic stages and promote long-term educational resilience.

The majority of respondents had 1–2 years of online learning experience (49.3%), reflecting the widespread implementation of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. This adaptation underscores the significance of sustainable digital transformation efforts in higher education, ensuring that students have continuous access to resilient and high-quality learning experiences. This adaptation indicates that most students have sufficient exposure to digital-based education, making it relevant to analyze how modern learning environments moderate the relationship between risk management, digital technology literacy, and student resilience. By understanding these student profiles, institutions can develop targeted strategies to enhance sustainable digital learning environments, ensuring that students remain adaptable and well-equipped for future academic and professional challenges.

3.2. Measurement

This study employs a structured framework to measure the relationships between the variables: Risk Management, Digital Technology Literacy, Modern Learning Environment, and Student Resilience. From a sustainability perspective, ensuring reliable and adaptive measurement tools is essential to capture the long-term impact of these factors on student development in digital learning environments. A 5-point Likert scale was used for all items, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), ensuring consistency and comparability in responses. This structured measurement approach supports sustainable educational assessment practices by enabling higher education institutions to monitor and enhance resilience, digital literacy, and risk management strategies over time.

The operationalization details for each variable are summarized in

Table 1 below, which provides an overview of the indicators used to measure key constructs related to student resilience and digital transformation in sustainable learning environments.

3.3. Method

This study used Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the relationships between the variables. From a sustainability perspective, adopting PLS-SEM as an analytical approach ensures a comprehensive and replicable methodology for assessing digital learning ecosystems and their long-term impact on student resilience. PLS-SEM was performed using SmartPLS version 4, a statistical software designed for path modeling and variance-based structural equation modeling. This approach aligns with sustainable educational research practices by facilitating the evaluation of multidimensional relationships in complex learning environments.

PLS-SEM is a robust multivariate method that allows for the simultaneous evaluation of multiple dependent and independent variables. It is particularly effective for complex models with many latent variables and indicators, as well as for smaller sample sizes, making it ideal for this research. Additionally, PLS-SEM supports sustainability in digital education research by offering a flexible approach that can be applied across diverse institutional contexts, ensuring continued assessment and improvement of modern learning environments. Moreover, PLS-SEM enables a deeper understanding of relationships between constructs by estimating path coefficients and identifying the strength of their effects [

124,

125].

The analysis was conducted in two stages: outer model evaluation and inner model evaluation. The outer modelassessed the relationships between constructs and their respective indicators through validity and reliability testing.Validity testing involved two stages: convergent validity, which measures the correlation between indicators and constructs based on loading factor values, and discriminant validity, which ensures constructs are distinct by analyzing the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). Reliability testing was performed using Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s Alpha (CA), with values exceeding 0.7 indicating acceptable internal consistency [

124,

126]. By ensuring high validity and reliability, this methodological approach contributes to sustainable research practices, enabling robust assessments that can be replicated and adapted for future studies on digital learning and resilience.

The inner model, or structural model, evaluated the relationships among the constructs and tested the proposed hypotheses. The inner model assessment began by analyzing the R² value, which indicates the predictive accuracy of the structural model and measures the variance explained by exogenous variables on endogenous variables. Additionally, Q² predictive relevance was calculated to determine the predictive capability of the model. The Goodness-of-Fit (GoF) index was used to evaluate the overall model fit, ensuring its structural feasibility. This approach ensures sustainable knowledge production by generating replicable statistical models that provide actionable insights for digital education resilience.

Hypothesis testing was conducted using the bootstrapping procedure, which generates t-statistics and p-values to determine the significance of path coefficients. A relationship was considered statistically significant if the t-statistic exceeded 1.96 or the p-value was below 0.05. The strength of these relationships was further assessed by analyzing the path coefficients (γ) obtained in the original sample [

124,

125]. By integrating these robust statistical techniques, this study contributes to the long-term sustainability of digital learning research, ensuring that its findings can be leveraged to enhance institutional policies and improve student outcomes in evolving digital education landscapes.

These methods ensured that the constructs were rigorously validated and the hypotheses were tested comprehensively. This approach also provided robust insights into the relationships among the variables in the context of sustainable digital learning environments and student resilience.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Measurement and Structural Model

Data analysis was conducted using the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) technique with SmartPLS version 4 software. This technique was employed to evaluate the relationships between latent constructs and their indicators in the measurement model (outer model) and the relationships between latent constructs in the structural model (inner model).

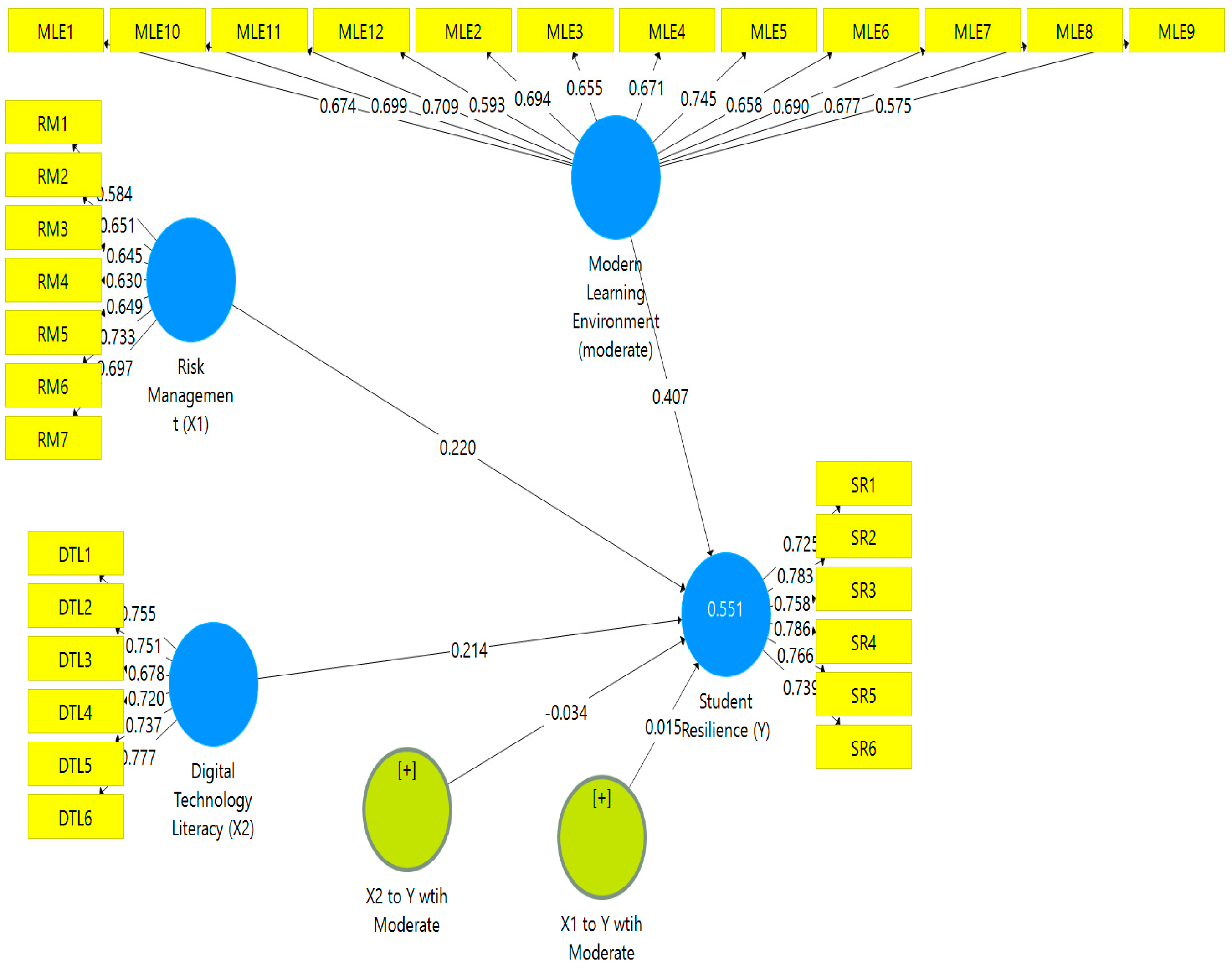

The results of the outer model analysis are visualized in

Figure 2, which illustrates the relationships between indicators and latent variables. This diagram serves as a crucial step in validating the measurement model, ensuring that each indicator significantly contributes to the latent variable it represents and meets the required validity and reliability standards.

Below is the visualization of the outer model:

Figure 2.

Path Diagram of The Outer Model. Generated from SEM-PLS analysis, 2025.

Figure 2.

Path Diagram of The Outer Model. Generated from SEM-PLS analysis, 2025.

Subsequently, the results of the outer model are summarized in a table that includes the values for loading factor, Composite Reliability (CR), Cronbach’s Alpha (CA), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). All indicators exhibit loading factor values above 0.70, indicating strong convergent validity. The CA and CR values for all constructs exceed 0.70, demonstrating high internal reliability. Additionally, the AVE values for each variable are greater than 0.50, indicating that the indicators adequately explain their respective constructs. The results of the outer model evaluation are presented in

Table 2 below.

The structural model evaluation is conducted to measure the predictive strength of independent variables on the dependent variables through the R-squared (R²) values. The analysis results indicate that the variable student resilience has an R² value of 0.546, meaning that 54.6% of the variability in this construct can be explained by the independent and moderating variables in the model. This value suggests that the model demonstrates good predictive ability. The results of the R² evaluation for the studied variables are summarized in

Table 3 below.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

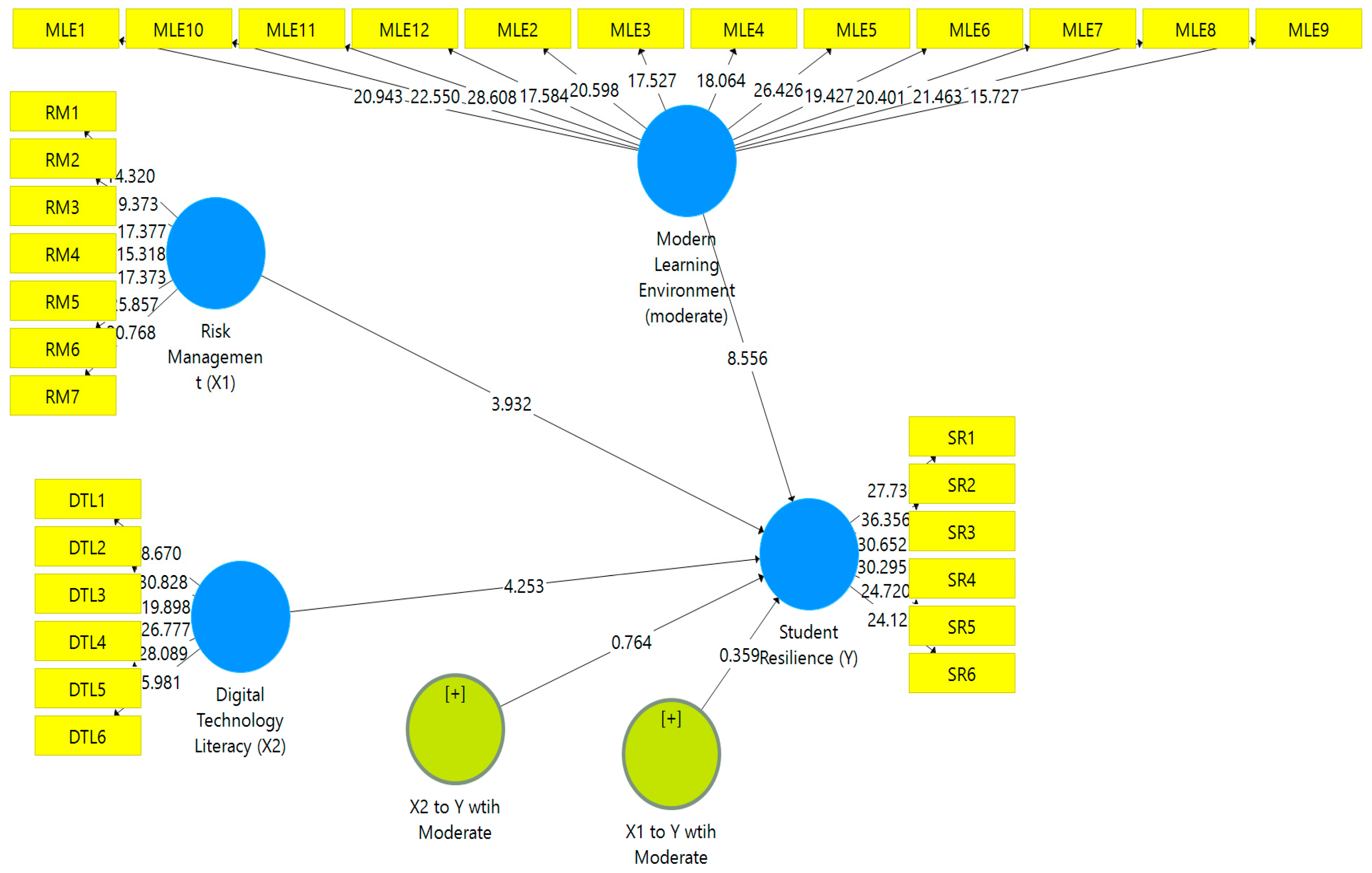

The hypothesis testing results in this study are presented in the form of a table and an inner model visualization. The analysis was conducted using bootstrapping to evaluate the significance of relationships between latent variables, both direct and moderated. The

Figure 3 below illustrates the inner model visualization, showing the direction of relationships, path coefficient values, and significance between constructs.

The hypothesis testing results are summarized in a table that includes the path coefficient values, t-statistics, and p-values for each hypothesis. These values provide insights into the strength and significance of the relationships between latent variables in the model. The detailed results of the hypothesis testing are presented in

Table 4 below.

Interpretation of Hypothesis Testing Results

- 1)

-

H1: Risk Management has a positive and significant effect on Student Resilience

The results show a path coefficient of 0.220, t-statistics of 3.932 (greater than 1.96), and a p-value of 0.000 (below 0.05). This confirms that effective risk management implementation significantly enhances student resilience. Institutions with well-implemented risk management approaches provide better support for students in overcoming learning challenges.

- 2)

-

H2: Digital Technology Literacy has a positive and significant effect on Student Resilience

With a path coefficient of 0.214, t-statistics of 4.253, and a p-value of 0.000, the results indicate that high digital technology literacy significantly contributes to strengthening student resilience. Students with strong technological skills are better equipped to adapt and utilize technology to support their learning process.

- 3)

-

H3: Modern Learning Environment moderates the relationship between Risk Management and Student Resilience

A path coefficient of 0.407, t-statistics of 8.556, and a p-value of 0.000 show that the modern learning environment significantly strengthens the relationship between risk management and student resilience. Modern learning infrastructure and technology act as catalysts that enhance the effectiveness of risk management in supporting student resilience.

- 4)

-

H4: Modern Learning Environment moderates the relationship between Digital Technology Literacy and Student Resilience

With a path coefficient of 0.015, t-statistics of 5.129, and a p-value of 0.000, the results indicate that the modern learning environment significantly strengthens the effect of digital technology literacy on student resilience. A supportive modern learning environment enables students to maximize the use of digital technology literacy in addressing academic challenges.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Risk Management Has a Significant Positive Effect on Student Resilience.

The results of this study provide empirical support that risk management has a significant positive effect on student resilience, as indicated by a path coefficient of 0.220, t-statistics of 3.932 (greater than the threshold of 1.96), and a p-value of 0.000 (below the significance level of 0.05). Well-implemented risk management strategies enable educational institutions to create a safe, structured, and supportive learning environment, enhancing students' ability to navigate academic challenges in a sustainable manner. These strategies include risk identification, contingency planning, data security measures, and the evaluation of risk mitigation effectiveness [

94,

127,

128,

129]. By fostering proactive risk management policies, institutions not only reduce academic uncertainties but also cultivate a resilient student body prepared for long-term adaptation in evolving educational landscapes.

By clearly communicating risks and mitigation steps, students can maintain their academic focus without excessive disruption from uncertainties, thereby ensuring continuity and sustainability in their educational journey [

78,

94,

130]. These findings demonstrate that institutions integrating risk management frameworks into their operational policies can enhance students' confidence in managing academic and professional pressures, which is a crucial element of resilience.

This positive relationship is also supported by literature demonstrating that risk management approaches not only reduce stress but also enhance adaptability, particularly in increasingly complex digital learning environments [

25,

131,

132]. Such strategies became particularly critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many educational institutions were forced to transition abruptly to online learning. Previous studies have noted that institutions with effective risk management measures exhibit higher organizational resilience and better academic outcomes among students [

35,

36].

Thus, these findings reinforce the relevance of risk management as a foundational element for supporting student resilience during the era of digital transformation. Furthermore, these results offer practical contributions to educational institutions by encouraging the continuous development of dynamic and adaptive risk management frameworks, which are essential for sustaining student resilience in the face of future educational challenges [

133,

134,

135].

5.2. Digital Technology Literacy Has a Significant Positive Effect on Student Resilience

The results of this study confirm that digital technology literacy significantly enhances student resilience, as evidenced by a path coefficient of 0.214, t-statistics of 4.253, and a p-value of 0.000. Digital technology literacy equips students with critical skills to navigate, evaluate, and effectively utilize digital tools, enabling them to adapt to academic challenges in a sustainable manner. Students with higher levels of digital literacy are better prepared to manage academic demands, collaborate seamlessly in virtual environments, and efficiently access learning resources, fostering long-term adaptability in digital education ecosystems. This competence not only reduces stress but also builds confidence, allowing students to feel more in control of their academic responsibilities while ensuring the sustainable use of digital resources for learning and professional development [

18,

104,

136]. Additionally, digital literacy fosters essential problem-solving skills and innovation, both of which are crucial for maintaining resilience in dynamic and rapidly evolving learning environments, particularly in the context of sustainable digital transformation [

137,

138].

This positive relationship aligns with prior studies emphasizing the critical role of digital literacy in supporting student adaptability, particularly during the transition to online and hybrid learning models. During the COVID-19 pandemic, students with strong digital literacy demonstrated higher levels of engagement and resiliencecompared to those with limited skills [

49,

53,

54]. Institutions that actively promote digital literacy programs contribute not only to strengthening student resilience but also to ensuring the long-term sustainability of digital education. These initiatives help students overcome technological barriers and fully utilize modern learning environments while preparing them for a digitally-driven workforce [

14,

139,

140].

These findings suggest that digital technology literacy is not merely a technical skill but a foundational competency essential for sustainable academic success in an increasingly digitized educational ecosystem [

141,

142]. Therefore, fostering digital literacy among students should be a strategic priority for institutions aiming to build resilience, promote lifelong learning, and support sustainable innovation in education.

5.3. Modern Learning Environment Moderates the Relationship Between Risk Management and Student Resilience

A path coefficient of 0.407, t-statistics of 8.556, and a p-value of 0.000 confirm that the modern learning environment (MLE) significantly moderates the relationship between risk management and student resilience, with the effect being more pronounced in high-quality MLEs. A modern learning environment, characterized by advanced digital infrastructure and innovative teaching strategies, enhances the effectiveness of risk management by providing students with structured and adaptable support systems that promote sustainable academic development. In high-quality MLEs, risk management measures such as clear communication, contingency planning, and robust security protocols are implemented more effectively, enabling students to maintain focus and resilience during academic challenges while ensuring long-term institutional adaptability [

5,

54].

Moreover, high-quality MLEs amplify the positive effects of risk management by fostering a supportive learning environment that integrates flexibility, inclusivity, and sustainability. For instance, institutions offering user-friendly digital platforms, real-time learning analytics, and personalized learning options empower students to take proactive steps in managing academic risks while ensuring equitable access to educational resources [

16,

143,

144]. Conversely, in low-quality MLEs with limited resources and poorly implemented strategies, the effectiveness of risk management in building resilience is diminished, as students face greater technological and academic barriers, leading to long-term disadvantages in digital learning readiness [

144].

These findings highlight the critical role of MLEs in bridging the gap between institutional strategies and student outcomes, ensuring that risk management efforts are not only reactive but also proactively support sustainable academic resilience. Based on these findings, it can be concluded that MLEs act as an essential moderating factor that strengthens the relationship between risk management and student resilience, reinforcing the importance of investing in digital education infrastructure to support long-term student success [

54,

145,

146].

5.4. Modern Learning Environment Moderates the Relationship Between Digital Technology Literacy and Student Resilience

With a path coefficient of 0.015, t-statistics of 5.129, and a p-value of 0.000, the findings confirm that the modern learning environment (MLE) significantly moderates the relationship between digital technology literacy and student resilience, with the effect being more pronounced in high-quality MLEs. A modern learning environment enhances the positive impact of digital technology literacy by providing students with the tools, infrastructure, and sustainable digital resources needed to effectively apply their digital skills. In high-quality MLEs, features such as reliable digital platforms, advanced learning analytics, and collaborative virtual tools amplify the benefits of digital literacy by enabling students to engage deeply with learning materials and overcome academic challenges in a sustainable manner [

5,

16,

54]. This interaction not only supports academic adaptation but also builds students’ confidence, fostering their resilience in navigating complex and rapidly evolving digital learning environments [

16,

147].

Furthermore, high-quality MLEs provide a supportive and sustainable ecosystem that allows students with higher digital literacy to maximize their capabilities through personalized learning pathways and inclusive technological designs. These environments ensure equitable access to digital resources, minimize digital divides, and encourage collaboration, further strengthening student resilience in digital education [

107,

148,

149]. Conversely, in low-quality MLEs, students may face technological and institutional barriers that hinder the application of their digital literacy skills, reducing their ability to build resilience and limiting their capacity to thrive in digital learning environments [

14,

70,

150].

These findings emphasize that MLEs serve as an essential moderating factor in the digital learning process, ensuring that students with strong digital literacy skills can fully capitalize on their abilities to adapt, succeed, and sustain long-term learning engagement in an increasingly digitalized education landscape [

16,

54,

105,

151].

5.5. Conclusion

This study concludes that risk management and digital technology literacy significantly enhance student resilience, emphasizing their critical role in fostering adaptability, academic success, and long-term learning sustainability in higher education. Moreover, the modern learning environment (MLE) serves as a key moderating factor, amplifying the positive effects of both risk management and digital literacy on resilience. High-quality MLEs, characterized by sustainable digital infrastructure, adaptive learning technologies, and inclusive teaching strategies, empower institutions to bridge the gap between institutional policies and student outcomes. These environments ensure that students can thrive in dynamic academic settings by providing equitable access to technological resources, fostering digital engagement, and minimizing barriers to learning.

These findings emphasize the urgent need for educational institutions to integrate robust risk management frameworks, prioritize digital literacy development, and invest in inclusive, technology-driven learning environments. By doing so, institutions can equip students with the resilience required to navigate the challenges of digital transformation, ensuring that they not only succeed academically but also develop long-term adaptability in an evolving digital education landscape.

6. Theoretical Implications

This study advances theoretical understanding of the relationship between risk management, digital technology literacy, modern learning environments (MLEs), and student resilience, particularly within the context of sustainable digital transformation in higher education. By demonstrating that risk management and digital technology literacy significantly enhance student resilience, this research extends existing resilience theories by incorporating institutional strategies and individual competencies as critical drivers of adaptability and long-term learning sustainability [

16,

90]. These findings contribute to resilience discourse by emphasizing the role of both proactive institutional support and student competencies in mitigating academic challenges in an evolving digital education landscape.

The moderating role of modern learning environments further validates theoretical frameworks that highlight the interplay between environmental factors and individual outcomes [

152,

153]. High-quality MLEs, characterized by sustainable digital infrastructure, adaptive learning ecosystems, and innovative pedagogical approaches, amplify the effects of risk management and digital literacy on resilience. This finding addresses a notable gap in resilience literature, which often overlooks the significance of environmental moderators in digital learning. By integrating these insights, this study provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how institutional, individual, and environmental factors collectively contribute to student adaptability, digital sustainability, and academic success in dynamic educational ecosystems [

154,

155,

156]. These implications lay a solid foundation for future research exploring the integration of digital technologies, institutional strategies, and sustainable environmental supports in fostering resilience and long-term educational transformation.

7. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer valuable practical insights for higher education institutions seeking to enhance student resilience and ensure long-term sustainability in the digital era.

First, the significant role of risk management underscores the necessity for universities to establish robust institutional frameworks that identify, mitigate, and manage risks effectively. Universities should develop comprehensive contingency plans, secure data systems, and transparent communication strategies to create a stable and supportive academic environment. These efforts not only reduce uncertainties but also promote institutional resilience, fostering a sense of security and adaptability among students. In turn, this enables students to maintain academic focus and preparedness for future disruptions [

36,

94].

Second, the positive impact of digital technology literacy highlights the urgent need for universities to invest in comprehensive, future-oriented digital literacy training programs. These initiatives should equip students with essential skills to effectively navigate digital tools, critically evaluate online information, and collaborate in virtual environments. Institutions should integrate digital literacy modules into curricula and provide accessible, structured learning resources that empower students to develop their technological competencies sustainably [

115,

157,

158].

Lastly, the moderating role of the modern learning environment (MLE) reinforces the importance of investing in sustainable, high-quality learning ecosystems. Universities should ensure reliable digital infrastructure, interactive learning platforms, and personalized learning opportunities to enhance the effectiveness of risk management and digital literacy. High-quality MLEs bridge the gap between institutional strategies and student outcomes by fostering a flexible, inclusive, and adaptive learning environment. This investment will not only strengthen student resilience but also support long-term educational sustainability and innovation [

62,

143].

In conclusion, higher education institutions can leverage these findings to develop integrated, future-proof strategies that combine risk management, digital literacy development, and sustainable modern learning environments. These efforts will better prepare students to navigate academic and professional challenges in an increasingly digital world while ensuring long-term institutional adaptability.

8. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that present valuable opportunities for future research and development.

First, the research employs a quantitative approach with cross-sectional data collected from 475 undergraduate students in Indonesia. While this methodology provides statistical insights, it may not fully capture the evolving nature of student resilience and digital adaptation over time. Additionally, the findings may not generalize across different cultural, institutional, or regional contexts. Future studies are encouraged to adopt longitudinal designs or mixed-method approaches to explore causal relationships and track changes in student resilience, digital literacy, and risk management effectiveness over time. Expanding the scope to include cross-country comparisons may also provide deeper insights into global trends in digital learning resilience.

Second, the research model focuses on four primary variables: risk management, digital technology literacy, modern learning environment, and student resilience. While these variables are crucial, student resilience is a multidimensional construct that may also be influenced by other psychological and environmental factors. Future research could integrate additional variables such as emotional well-being, social support systems, instructor competence, and institutional digital policies to provide a more holistic perspective on the factors shaping student resilience in digital education. Moreover, incorporating emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence-driven learning assistants or immersive virtual learning environments, could offer new insights into how digital transformation influences student adaptability.

Finally, this study is limited to undergraduate students in higher education. However, the dynamics of resilience and digital literacy may differ across other educational levels or professional training environments. Future research could expand the focus to include graduate students, vocational learners, and professionals engaging in lifelong learning. Exploring resilience in corporate digital training programs or continuing education settings could offer broader insights into how digital literacy and risk management strategies translate into workforce readiness and long-term career adaptability.

By addressing these limitations, future studies can enhance the depth, applicability, and global relevance of research on digital learning resilience, ensuring that educational institutions and policymakers are better equipped to support students in an increasingly digital and uncertain world.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.S. and S.P.; methodology, S.P.; software, A.D.; validation, A.S., S.P. and A.D.; formal analysis, S.P.; investigation, A.S.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, S.P.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.D.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HRM |

Human Resource Management |

| SET |

Social Exchange Theory |

| SDT |

Self-Determination Theory |

| CSR |

Corporate Social Responsibility |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technology |

| MLE |

Modern Learning Environment |

| PLS-SEM |

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

References

- Matsieli, M.; Mutula, S. , “COVID-19 and Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions: Towards Inclusive and Equitable Access to Quality Education,” Educ Sci (Basel), vol. 14, no. 8, p. 819, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wollscheid, S.; Scholkmann, A.; Capasso, M.; Olsen, D.S. , “Digital Transformations in Higher Education in Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from a Scoping Review,” in Digital Transformations in Nordic Higher Education, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023, pp. 217–242. [CrossRef]

- Minnett, K.; Stephenson, Z. , “Exploring the Psychometric Properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC),” Advers Resil Sci, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A., & M. H. Martin, Student resilience and boosting academic buoyancy. 2020.

- Motz, R.; Porta, M.; Reategui, E. , “Building Resilient Educational Systems: The Power of Digital Technologies,” 2023, pp. 370–383. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. , “Sustaining Student Roles, Digital Literacy, Learning Achievements, and Motivation in Online Learning Environments during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 4388, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Guaña-Moya, J.; Salgado-Reyes, N.; Arteaga-Alcívar, Y.; Espinosa-Cevallos, A. , “Importance of Cybersecurity Education to Reduce Risks in Academic Institutions,” 2024, pp. 31–40. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Adarkwah, M.A.; Liu, M.; Hu, Y.; Zhuang, R.; Chang, T. , “Digital Pedagogy for Sustainable Education Transformation: Enhancing Learner-Centred Learning in the Digital Era,” Frontiers of Digital Education, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Worldbank, “Ensuring Learning Continuity During Crises: Applying Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic to Shape Resilience and Adaptability,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2024/10/30/learning-education-continuity-during-crises-covid19?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Matías-García, J.A.; Cubero, M.; Santamaría, A.; Bascón, M.J. , “The learner identity of adolescents with trajectories of resilience: the role of risk, academic experience, and gender,” European Journal of Psychology of Education, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 2739–2761, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Strietholt, R.; Blömeke, S. , “Academic resilience: underlying norms and validity of definitions,” Educ Assess Eval Account, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 169–202, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, S.; Turner, M.; Scott-Young, C.M. , “Developing the Resilient Learner: A Resilience Framework for Universities,” in Transformations in Tertiary Education, Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2019, pp. 27–42. [CrossRef]

- Bulut, M.; Bulut, A.; Kaban, A.; Kirbas, A. , “Exploring the Nexus of Technology, Digital, and Visual Literacy: A Bibliometric Analysis,” International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 345–363, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Meridha, J.M. , “The causes of poor digital literacy in educational practice, and possible solutions among the stakeholders: a systematic literature review,” SN Social Sciences, vol. 4, no. 11, p. 210, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, J.; Bai, J.; Yang, H.H.; Zhang, D. , “Assessing Secondary Students’ Digital Literacy Using an Evidence-Centered Game Design Approach,” 2023, pp. 214–223. [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Bertel, L.B.; Lyngdorf, N.E.R.; Markman, A.O.; Andersen, T.; Ryberg, T. , “Emerging Digital Practices Supporting Student-Centered Learning Environments in Higher Education: A Review of Literature and Lessons Learned from the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 1673–1696, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Buchan, M.C.; Bhawra, J.; Katapally, T.R. , “Navigating the digital world: development of an evidence-based digital literacy program and assessment tool for youth,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 8, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Rehman, S.; Altalbe, A.; Rehman, E.; Shahiman, M.A. , “Digital literacy as a catalyst for academic confidence: exploring the interplay between academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination among medical students,” BMC Med Educ, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 1317, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Yang, N. , “Digital resilience and technological stress in adolescents: A mixed-methods study of factors and interventions,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 29, no. 14, pp. 19067–19113, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Hong, W.C.H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y. , “Effects and side effects of personal learning environments and personalized learning in formal education,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 29, no. 15, pp. 20729–20756, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Demir, K.A. , “Smart education framework,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 29, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M.S.; Evans, K.B. , “Integrating Digital Tools to Enhance Access to Learning Opportunities in Project-based Science Instruction,” TechTrends, vol. 68, no. 5, pp. 882–891, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Depedtambayan, “Enhancing Student Engagement through Interactive Teaching Methods: Strategies and Best Practices for Educators,” https://depedtambayan.net/interactive-teaching-methods-student-engagement/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Drossel, K.; Eickelmann, B.; Vennemann, M. , “Schools overcoming the digital divide: in depth analyses towards organizational resilience in the computer and information literacy domain,” Large Scale Assess Educ, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 9, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Yang, N. , “Digital resilience and technological stress in adolescents: A mixed-methods study of factors and interventions,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 29, no. 14, pp. 19067–19113, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Smith, C.J.M.; Al-Samarraie, H. , “Digital technology adaptation and initiatives: a systematic review of teaching and learning during COVID-19,” J Comput High Educ, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 813–834, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.P.; Chiappe, A. , “Artificial Intelligence and Digital Ecosystems in Education: A Review,” Technology, Knowledge and Learning, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 2153–2170, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Khaw, T.Y.; Teoh, A.P. , “Risk management in higher education research: a systematic literature review,” Quality Assurance in Education, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 296–312, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dursun, C. , “Risk Management in Digital Era: Opportunities and Challenges,” 2024, pp. 231–251. [CrossRef]

- L. ; Ruzic-Dimitrijevic, D.J., “The risk management in higher education institutions.,” Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 137–152, 2014.

- Guaña-Moya, J.; Salgado-Reyes, N.; Arteaga-Alcívar, Y.; Espinosa-Cevallos, A. , “Importance of Cybersecurity Education to Reduce Risks in Academic Institutions,” 2024, pp. 31–40. [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; et al. , “Cybersecurity in Universities: An Evaluation Model,” SN Comput Sci, vol. 4, no. 5, p. 569, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gourisaria, M.K.; Chufare, A.T.; Banik, D. , “Cybersecurity Imminent Threats with Solutions in Higher Education,” 2023, pp. 35–47. [CrossRef]

- COSO, “Enterprise Risk Management,” https://www.coso.org/guidance-erm?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Shaya, N.; Abukhait, R.; Madani, R.; Khattak, M.N. , “Organizational Resilience of Higher Education Institutions: An Empirical Study during Covid-19 Pandemic,” Higher Education Policy, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 529–555, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. ; P. I. ; Izumi, S.R., Safety and resilience of higher educational institutions. Springer., 2022.

- Ross, P.M.; Scanes, E.; Locke, W. , “Stress adaptation and resilience of academics in higher education,” Asia Pacific Education Review, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. ; Beale, K.I., “Building Academic Resilience in Secondary School Students: A Research Review and Case Study.,” In Transcending Crisis by Attending to Care, Emotion, and Flourishing, Routledge., pp. 48–71, 2023.

- Wong, Z.Y.; Liem, G.A.D. , “Student Engagement: Current State of the Construct, Conceptual Refinement, and Future Research Directions,” Educ Psychol Rev, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 107–138, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. ; T. S. ; Lagubeau, H.C., “Active learning reduces academic risk of students with nonformal reasoning skills: Evidence from an introductory physics massive course in a Chilean public university.,” Phys Rev Phys Educ Res, vol. 16, no. 2, 2020.

- Barbayannis, G.; Bandari, M.; Zheng, X.; Baquerizo, H.; Pecor, K.W.; Ming, X., “Academic Stress and Mental Well-Being in College Students: Correlations, Affected Groups, and COVID-19,” Front Psychol, vol. 13, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Monsivais, C.L.; Rodríguez-Cano, S.; Lema-Moreira, E.; Delgado-Benito, V. , “Relationship between mental health and students’ academic performance through a literature review,” Discover Psychology, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 119, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.; et al. , “Factors that influence mental health of university and college students in the UK: a systematic review,” BMC Public Health, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 1778, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. ; U. H. ; M. A. ; H. I. M. ; Quraishi, O.M.R., “Empowering students through digital literacy: A case study of successful integration in a higher education curriculum.,” Journal of Digital Learning and Distance Education, vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 667–681, 2024.

- Holm, P. , “Impact of digital literacy on academic achievement: Evidence from an online anatomy and physiology course,” E-Learning and Digital Media, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J.; et al. , “The HeDiCom framework: Higher Education teachers’ digital competencies for the future,” Educational technology research and development, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 33–53, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Spante, M.; Hashemi, S.S.; Lundin, M.; Algers, A. , “Digital competence and digital literacy in higher education research: Systematic review of concept use,” Cogent Education, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 1519143, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Hong, A.J.; Song, H.-D. , “The roles of academic engagement and digital readiness in students’ achievements in university e-learning environments,” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 21, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Akpen, C.N.; Asaolu, S.; Atobatele, S.; Okagbue, H.; Sampson, S. , “Impact of online learning on student’s performance and engagement: a systematic review,” Discover Education, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 205, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Widowati, A.; Siswanto, I.; Wakid, M. , “Factors Affecting Students’ Academic Performance: Self Efficacy, Digital Literacy, and Academic Engagement Effects,” International Journal of Instruction, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 885–898, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “The relationship between digital literacy and academic performance of college students in blended learning: the mediating effect of learning adaptability,” Advances in Educational Technology and Psychology, vol. 7, no. 8, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R.A. , “The Impact of Technology Integration on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study,” International Journal of Social Science, Educational, Economics, Agriculture Research and Technology (IJSET), vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 592–596, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. , “Sustaining Student Roles, Digital Literacy, Learning Achievements, and Motivation in Online Learning Environments during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 4388, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Polat, M. , “Readiness, resilience, and engagement: Analyzing the core building blocks of online education,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 29, no. 13, pp. 1–28, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, S.; Tengli, M.B.; Ramadas, S.; Sathyan, A.R.; Bhatt, A. , “Bridging the Divide: Assessing Digital Infrastructure for Higher Education Online Learning,” TechTrends, vol. 68, no. 6, pp. 1107–1116, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, C.; et al. , “Understanding Digital Inequality: A Theoretical Kaleidoscope,” Postdigital Science and Education, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 894–932, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, Y.; Gebremeskel, M.M.; Moges, B.T.; Tilwani, S.A.; Azmera, Y.A. , “Rethinking the digital divide and associated educational in(equity) in higher education in the context of developing countries: the social justice perspective,” The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jisc, “Framework for digital transformation in higher education,” https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/framework-for-digital-transformation-in-higher-education?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Handley, F.J.L. , “Developing Digital Skills and Literacies in UK Higher Education: Recent developments and a case study of the Digital Literacies Framework at the University of Brighton, UK,” PUBLICACIONES, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 97–109, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Education, Z.O. , “Innovative teaching strategies to enhance students’ learning,” https://zonofeducation.com/innovative-teaching-strategies/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- S. ; Khanal, P.S.R., “Analysis, Modeling and Design of Personalized Digital Learning Environment.,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.10476., 2024.

- Kerimbayev, N.; Umirzakova, Z.; Shadiev, R.; Jotsov, V. , “A student-centered approach using modern technologies in distance learning: a systematic review of the literature,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 61, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Ma, S.; Spector, J.M. , “Personalized adaptive learning: an emerging pedagogical approach enabled by a smart learning environment,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 9, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- El-Sabagh, H.A. , “Adaptive e-learning environment based on learning styles and its impact on development students’ engagement,” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 53, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mejeh, M.; Rehm, M. , “Taking adaptive learning in educational settings to the next level: leveraging natural language processing for improved personalization,” Educational technology research and development, vol. 72, no. 3, pp. 1597–1621, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Elmoazen, R.; Saqr, M.; Khalil, M.; Wasson, B. , “Learning analytics in virtual laboratories: a systematic literature review of empirical research,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 23, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Arslan, O.; Xing, W.; Kamali-Arslantas, T. , “Exploring collaborative problem solving in virtual laboratories: a perspective of socially shared metacognition,” J Comput High Educ, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 296–319, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Baanqud, N.S.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Alfarraj, O. , “Engagement in cloud-supported collaborative learning and student knowledge construction: a modeling study,” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 56, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Wang, W.-T. , “Enhancing students’ online collaborative PBL learning performance in the context of coauthoring-based technologies: A case of wiki technologies,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 2303–2328, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Timotheou, S.; et al. , “Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools’ digital capacity and transformation: A literature review,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 6695–6726, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Contrino, M.F.; Reyes-Millán, M.; Vázquez-Villegas, P.; Membrillo-Hernández, J. , “Using an adaptive learning tool to improve student performance and satisfaction in online and face-to-face education for a more personalized approach,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 6, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L., “Effects of Psychological Resilience on Online Learning Performance and Satisfaction Among Undergraduates: The Mediating Role of Academic Burnout,” The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Keržič, D.; et al. , “Academic student satisfaction and perceived performance in the e-learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence across ten countries,” PLoS One, vol. 16, no. 10, p. e0258807, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- El Galad, A.; Betts, D.H.; Campbell, N. , “Flexible learning dimensions in higher education: aligning students’ and educators’ perspectives for more inclusive practices,” Front Educ (Lausanne), vol. 9, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sowell, J. , “Making Learning Inclusive in Digital Learning Environments.,” In English Teaching Forum, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 2–13, 2023.

- Wikiversity, “Academic resilience: What is academic resilience, why does it matter, and how can it be enhanced?,” https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Motivation_and_emotion/Book/2021/Academic_resilience?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Cassidy, S. , “Resilience Building in Students: The Role of Academic Self-Efficacy,” Front Psychol, vol. 6, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, H.; Siu, O.-L.; Yu, H. , “How and When Resilience can Boost Student Academic Performance: A Weekly Diary Study on the Roles of Self-Regulation Behaviors, Grit, and Social Support,” J Happiness Stud, vol. 25, no. 4, p. 36, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, L. , “Structural equation modeling of university students’ academic resilience academic well-being, personality and educational attainment in online classes with Tencent Meeting application in China: investigating the role of student engagement,” BMC Psychol, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 347, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zayed, A.M., “Digital Resilience, Digital Stress, and Social Support as Predictors of Academic Well-Being among University Students,” J Educ Train Stud, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 60, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. ; Sukup, C.R., “Examing the Effects of Resilience on Stress and Academic Performance in Business Undergraduate College Students.,” Coll Stud J, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 293–304, 2021.

- Education, O. , “Understanding Resilience and Its Importance in Education,” https://www.oneeducation.org.uk/understanding-resilience-and-its-importance-in-education/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Namaziandost, E.; Heydarnejad, T.; Azizi, Z. , “To be a language learner or not to be? The interplay among academic resilience, critical thinking, academic emotion regulation, academic self-esteem, and academic demotivation,” Current Psychology, vol. 42, no. 20, pp. 17147–17162, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cattelino, E.; et al. , “Self-efficacy, subjective well-being and positive coping in adolescents with regard to Covid-19 lockdown,” Current Psychology, vol. 42, no. 20, pp. 17304–17315, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, D.P.; Kumari, B.S.S.; Padmambika, P. , “Collaborative learning and group dynamics in digital environments,” International Journal of Social Science and Education Research, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 105–108, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ColourmyLearning, “Essential Skills for University Students: Adaptability and Resilience,” https://www.colourmylearning.com/2024/04/essential-skills-for-university-students-adaptability-and-resilience/.

- Chye, S.M.; Kok, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.S.; Er, H.M. , “Building resilience among undergraduate health professions students: identifying influencing factors,” BMC Med Educ, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 1168, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jisc, “Digital transformation in higher education,” https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/digital-transformation-in-higher-education?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Gull, M.; Parveen, S.; Sridadi, A.R. , “Resilient higher educational institutions in a world of digital transformation,” foresight, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 755–774, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Ferreira, L.; Pereira, L.; Sousa, B. , “The Influence of Resilience on the Digital Resilience of Higher Education Students: Preliminary Insights,” 2025, pp. 281–290. [CrossRef]

- Carsone, B.; Bell, J.; Smith, B. , “Fostering academic resilience in higher education,” Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, vol. 12, no. 1, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Skoulidas, N.; Alexopoulos, N.; Raptis, N. , “Higher Education Students’ Perceptions of Risk and Crisis Management in Universities,” European Journal of Education and Pedagogy, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 74–85, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Odlin, D.; Benson-Rea, M.; Sullivan-Taylor, B. , “Student internships and work placements: approaches to risk management in higher education,” High Educ (Dordr), vol. 83, no. 6, pp. 1409–1429, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhan, M., “The influence of university management strategies and student resilience on students well-being & psychological distress: investigating coping mechanisms and autonomy as mediators and parental support as a moderator,” Current Psychology, vol. 43, no. 31, pp. 25604–25620, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Mijangos, L.P.; Rodríguez-Arce, J.; Martínez-Méndez, R.; Reyes-Lagos, J.J. , “Advances and challenges in the detection of academic stress and anxiety in the classroom: A literature review and recommendations,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 3637–3666, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hub, T.E. , “How to help students improve their resilience,” https://theeducationhub.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/How-to-help-students-improve-their-resilience.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Cahill, H.; Dadvand, B. , “Social and Emotional Learning and Resilience Education,” in Health and Education Interdependence, Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020, pp. 205–223. [CrossRef]

- Bertsia, V.; Poulou, M. , “Resilience: Theoretical Framework and Implications for School,” International Education Studies, vol. 16, no. 2, p. 1, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, K.; Burtniak, K.; Rüth, M., “Online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic: How university students’ perceptions, engagement, and performance are related to their personal characteristics,” Current Psychology, vol. 43, no. 18, pp. 16711–16730, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Collie, R.J.; Nagy, R.P. , “Adaptability and High School Students’ Online Learning During COVID-19: A Job Demands-Resources Perspective,” Front Psychol, vol. 12, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kimmons, R. , “Safeguarding student privacy in an age of analytics,” Educational Technology Research and Development, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 343–345, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Amo-Filva, D.; et al. , “Security and Privacy in Academic Data Management at Schools: SPADATAS Project,” 2023, pp. 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Shandilya, S.K.; Datta, A.; Kartik, Y.; Nagar, A. , “Achieving Digital Resilience with Cybersecurity,” 2024, pp. 43–123. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.K.; et al. , “The mediating effect of digital literacy and self-regulation on the relationship between emotional intelligence and academic stress among university students: a cross-sectional study,” BMC Med Educ, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 1309, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Cheung, K.; Sit, P. , “Identifying key features of resilient students in digital reading: Insights from a machine learning approach,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 2277–2301, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jaya, F.; Sucipto, S. , “Digital Literacy, Academic Self-Efficacy, and Student Engagement: Its Impact on Student Academic Performance in Hybrid Learning,” Journal of Innovation in Educational and Cultural Research, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 458–470, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, M.L.; Greene, M.J.; Lobczowski, N.G. , “A Systematic Review of Research on Personalized Learning: Personalized by Whom, to What, How, and for What Purpose(s)?,” Educ Psychol Rev, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 1675–1715, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Dwiningrum, S.I.A.; Rukiyati, R.; Setyaningrum, A.; Sholikhah, E.; Sitompul, N., “Digital Literacy Requires School Resilience,” Jurnal Kependidikan Penelitian Inovasi Pembelajaran, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–14, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mithembu, T. , “Powering Progress: How Learning Management Systems Shape Modern Education,” https://education.adaptit.tech/blog/learning-management-systems-shape-education/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Aladini, A.; Bayat, S.; Abdellatif, M.S. , “Performance-based assessment in virtual versus non-virtual classes: impacts on academic resilience, motivation, teacher support, and personal best goals,” Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 5, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, D.P.; Kumari, B.S.S.; Padmambika, P. , “Collaborative learning and group dynamics in digital environments,” International Journal of Social Science and Education Research, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 105–108, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, W.J. , “Educational Institution Safety and Security,” in Encyclopedia of Security and Emergency Management, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021, pp. 243–252. [CrossRef]

- Gerardo, V.; Fajar, A.N. , “Academic IS Risk Management using OCTAVE Allegro in Educational Institution,” Journal of Information Systems and Informatics, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 687–708, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Galiutinova, E.I.; Pervushina, T.L. , “Educational Institution Risk Management Model,” Sep. 2021, pp. 2061–2069. [CrossRef]

- Audrin, C.; Audrin, B. , “Key factors in digital literacy in learning and education: a systematic literature review using text mining,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 7395–7419, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Getenet, S.; Cantle, R.; Redmond, P.; Albion, P. , “Students’ digital technology attitude, literacy and self-efficacy and their effect on online learning engagement,” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 3, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.A.T.; Habók, A. , “Tools for assessing teacher digital literacy: a review,” Journal of Computers in Education, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 305–346, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Grierson, E.M. , “Modern learning environments,” Educational Philosophy and Theory, vol. 49, no. 8, pp. 743–743, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Wright, N. , “Framing Learning Spaces: Modern Learning Environments and ‘Modern’ Pedagogy,” in Becoming an Innovative Learning Environment, Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2018, pp. 21–45. [CrossRef]

- Zajda, J. , “Creating Effective Learning Environments in Schools Globally,” 2021, pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Saastamoinen, U.; Eronen, L.; Juvonen, A.; Vahimaa, P. , “Wellbeing at the 21st century innovative learning environment called learning ground,” Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 239–252, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, W. , “The Role of Academic Resilience, Motivational Intensity and Their Relationship in EFL Learners’ Academic Achievement,” Front Psychol, vol. 12, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Rehman, S.; Zhao, Y.; Rehman, E.; Yaqoob, B. , “Exploring the interplay of academic stress, motivation, emotional intelligence, and mindfulness in higher education: a longitudinal cross-lagged panel model approach,” BMC Psychol, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 732, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]