1. Introduction

ABC transporters are presented in a wide range of organisms and transport a wide variety of substances coupled to ATP binding and hydrolysis. These latter are provided by conserved intracellular ABC domains, whereas substrate specificity is determined by the transmembrane regions. Human ABC multidrug transporters reside in important tissue barriers and work together in defense against various chemically unrelated compounds by extruding toxic endo- and xenobiotics [

1,

2,

3]. Among these, the ABCG2 multidrug transporter is present in the plasma membrane of several cells and tissue barriers, including the blood-brain barrier, kidney, intestines and stem cells [

4,

5,

6]. The importance of ABCG2 has been shown in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME) and toxicity of various drugs, and has a role in the multidrug resistance of cancer cells [

7,

8,

9]. Besides causing drug resistance, ABCG2 is also important in uric acid excretion and mutations in the

ABCG2 gene contribute to a genetic susceptibility to gout [

10,

11]. Being a multidrug transporter, the substrates of ABCG2 vary in structure and size, thus understanding the molecular transport mechanism of ABCG2 should help drug design and therapeutic decisions. Investigating the interactions with ABCG2 of a new drug under development is recommended by both the FDA and EMA [

12,

13].

Current ABCG2 structural models are based on high-resolution atomic structures and knowledge about similar ABCG transporters, ABCG2 [

14,

15,

16], ABCG5/G8 [

17], and ABCG1 [

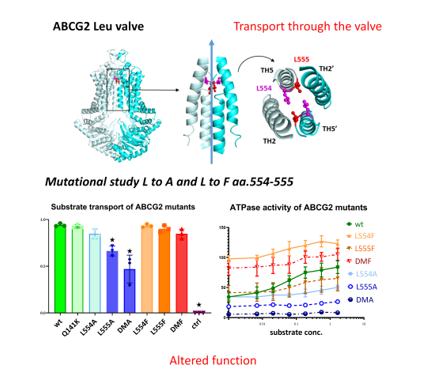

18]). However, the exact drug binding site(s) and the molecular pathway of exporting various drugs are still not fully uncovered, although molecular dynamic simulations along with mutational studies should help to understand the biochemical details of drug transport. Recent cryo-EM structural and mutational studies suggested that the opening and closing of the molecular extrusion pathway is controlled by a ‘leucine valve/plug’ in the near extracellular part of transmembrane domains (positions 554L, 555L) [

14,

15,

19]. ABCG2 functions as a homodimer, and this leucine valve is suggested to be formed by residues of both monomers – see also

Supplementary Figure S3A.

However, several details of these earlier studies were controversial. A report indicated that the L555A mutant could not be expressed, while the L554A variant was expressed and showed significantly higher baseline ATPase activity, with reduced stimulation by E1S (estrone-1-sulfate), although E1S transport was accelerated [

15]. In another study, the L554 and L555 residues were substituted by alanine, isoleucine, and cysteine, and functionality was tested in HEK293 cells [

19]. The authors concluded that all L555 mutants showed strongly reduced expression, still, the mitoxantrone transport capability of the L555A mutant was retained and this variant had an increased ATPase activity. This suggestion is partially in contrast with our previous study in Sf9 insect cells [

20], reporting that the L555A variant could be expressed normally but the functionality was compromised. In this report we have also shown that mutation of the L558 residue to alanine, localized near to the 554-555 residues, did not change transport activity while drug stimulation of the ATPase activity was decreased.

In recent studies, the homologous positions to the proposed “leucine valve” of ABCG2, have also been shown to have important function in other ABCG type proteins. The human ABCG1, ABCG4, ABCG5 and ABCG8 transporters are involved in sterol transport, the homologous sites are often phenylalanines instead of leucines (F570, F571 in ABCG1, F576, M577 in ABCG8 and L549, F548 in ABCG5 in ABCG5/G8 heterodimer), and sterol binding was localized near these residues [

18,

21]. In the case of the ABCG36 plant protein, when the corresponding L704 residue was mutated to phenylalanine, a significant change in the transported substrate specificity was observed [

22].

In the present work we aimed to revisit the analysis of this region and our hypothesis was that mutating the “valve” leucines to alanine or phenylalanine in ABCG2 may alter the function and substrate recognition of this transporter. The variants examined in our experiments were the following: L554A, L555A, L554A-L555A (DMA) double mutant to alanine, L554F, L555F, and L554F-L555F (DMF) double mutant to phenylalanine. In HEK293 cells both transient and stable expression of these mutants was achieved. We measured the cell surface expression of ABCG2 by binding of the 5D3 antibody that recognizes an extracellular epitope of ABCG2, while total ABCG2 protein expression was estimated by western blotting. EGFP was expressed from the constructs using an IRES2 element, thus ABCG2 was not tagged while the cellular expression levels could be followed by simultaneous eGFP expression levels. ABCG2 dependent Hoechst33342 transport experiments were performed in live cells by using flow cytometry. In parallel experiments ABCG2 variants were also expressed in Sf9 insect cells, known to properly express even those membrane protein variants which are hard to express in mammalian cells. Both ABCG2-ATPase and substrate transport measurements were performed in isolated membranes of the ABCG2 expressing Sf9 cells.

2. Results

2.1. Expression and Function of ABCG2 Variants in a Human Cell Line, HEK293

The ABCG2 variants we have examined in HEK293 cells were the L554F, L555F, and the L554F-L555F (DMF) double phenylalanine mutant, as well as the alanine mutants L554A, L555A, and the L554A-L555A (DMA) double alanine mutant. During some of the experiments, in addition to the WT-ABCG2, the well-characterized, naturally occurring Q141K variant was also used as a control (the Q141K-ABCG2 was shown to have a reduced cell surface expression due to folding deficiency but retained function [

23,

24,

25]). ABCG2 variants were either investigated after transient expression or stably inserted in the genome via the Sleeping Beauty transposon method. ABCG2 expression in the construct applied is driven by a CAG promoter and the transcribed mRNA contains an untagged ABCG2 and an eGFP code, separated by an IRES2 element [

25]. This enables simultaneous expression of the ABCG2 and eGFP, and transfection efficiency can be monitored based on GFP fluorescence in the cells. Stable cell lines could also be generated by sorting GFP positive cells after genomic insertion of the sequence by the Sleeping Beauty transposon system.

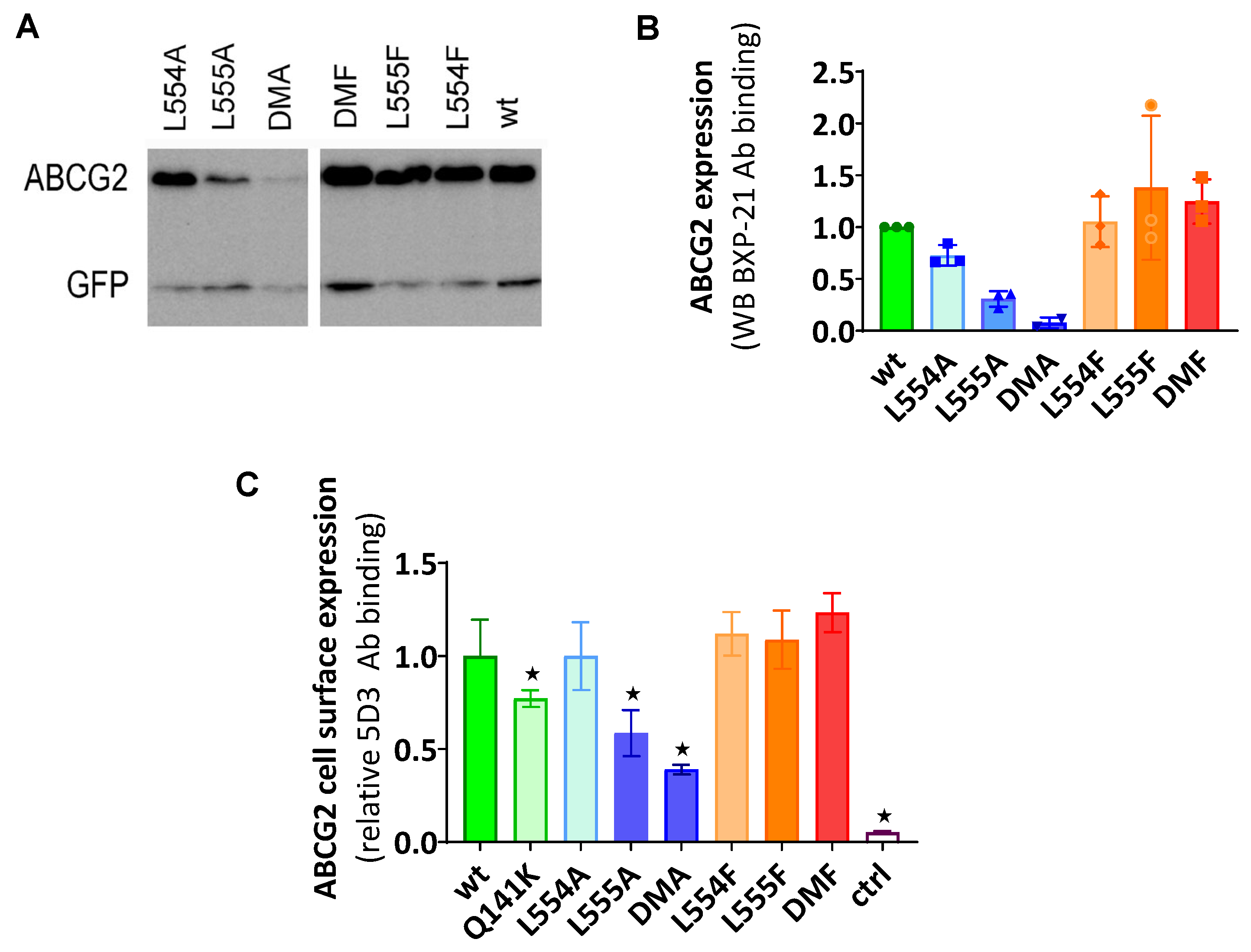

According to the western blot results shown in

Figure 1A,B, phenylalanine variants were expressed at similar levels to the WT in the transiently transfected cells, while alanine mutants showed decreased levels of ABCG2, especially if L555 was mutated. When compared to the WTABCG2, L554A showed a slightly lower expression level, L555A resulted in a large decrease in ABCG2 protein expression, while the double alanine mutant L554A-L555A (DMA) showed almost negligible protein expression.

To investigate the presence and amount of ABCG2 in the plasma membrane, cell surface expression measurements were performed in live cells via flow cytometry, after labeling the cells with the 5D3 antibody recognizing the extracellular epitope of ABCG2. Levels of the ABCG2 variants on the cell surface were found to be similar to the WT ABCG2 for L554F, L555F, DMF and L554A variants but L555A and DMA cell surface level (58% and 38% respectively) was even less than Q141K (77%) used as a reference for reduced surface level (

Figure 1C). These data were similar both in HEK cells transiently or stably expressing the ABCG2 variants.

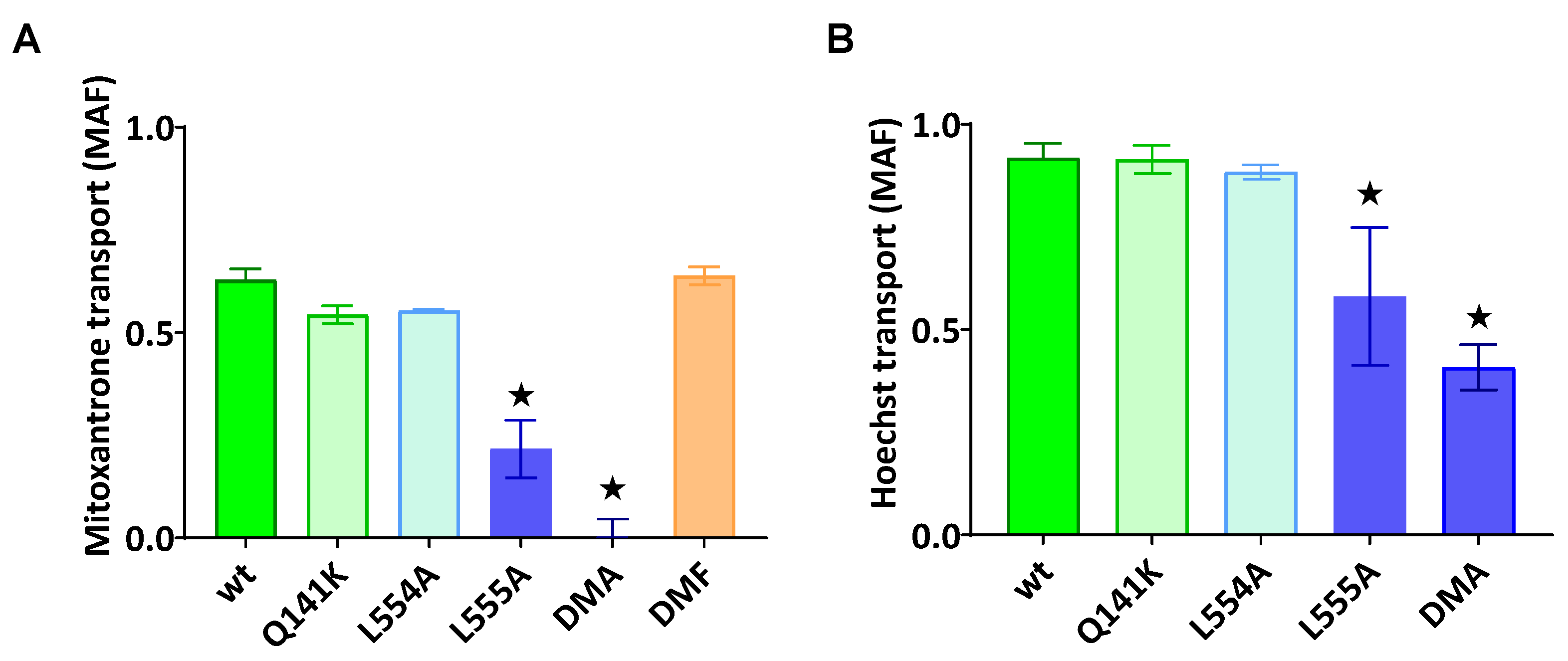

Functionality of the ABCG2 variants was examined by using the transported fluorescent substrates mitoxantrone and Hoechst33342 and uptake was measured in HEK293 cells via flow cytometry. In the following experiments, using cells transiently expressing ABCG2, transport activity was measured 48 hours after transfection. Cells were gated for GFP expression to include only ABCG2 positive cells and dye uptake was measured in the absence (active transport) and in the presence of Ko143 (fully inhibiting ABCG2 function). The MAF (multidrug resistance activity factor) values, corresponding to relative transport activity, were calculated from these measurements (for details see Methods).

As documented in

Figure 2A,B, the ABCG2-L555A expressing cells showed a significantly decreased Hoechst33342 and mitoxantrone transport activity, and the L554A-L555A double mutant ABCG2 showed practically no mitoxantrone transport and a strongly decreased Hoechst transport activity. In these experiments we found no significantly altered transport activity of the L554A, the L554F, the L555F and the L554F-L555F double mutants (from the phenylalanine variants only the double mutant (DMF) is shown in

Figure 2A).

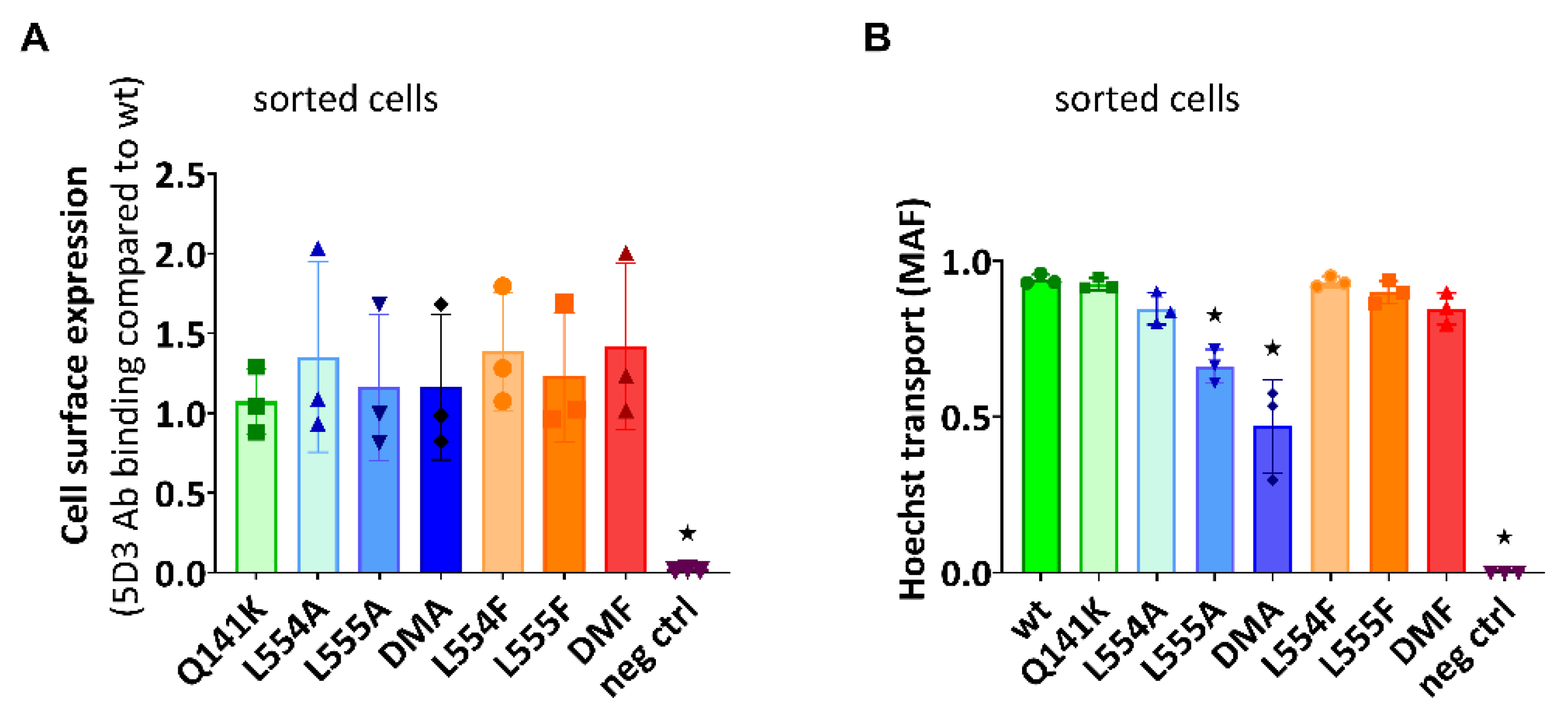

In the following experiments we wanted to explore if the diminished substrate transport rate of the ABCG2 L555A and DMA mutants is a functional defect, or the consequence of a lower cell surface presence of these variants. For these studies, we have generated stable ABCG2 expressing HEK cell lines by the Sleeping Beauty transposon method (see Methods), and then the cells were sorted based on equal levels of cell surface 5D3 anti-ABCG2 antibody staining by flow cytometry. Transposon-based integration of the expression constructs may cause various protein expression levels but this method enabled the selection of stable cell lines expressing similar amounts of the examined ABCG2 variants at the cell surface. As shown in

Figure 3A, by using this method we could select cells with similar, relatively high levels of ABCG2 expression on the cell surface, even from the L555A and DMA expressing HEK cell lines. Thereby we could measure ABCG2 transport function at nearly equal cell surface expression levels of all the ABCG2 variants. In these experiments we used relatively higher Hoechst33342 concentrations (up to 10 uM) to explore potential functional differences at increased substrate loading.

As shown in

Figure 3B, although having similar plasma membrane expression level in the sorted ABCG2-HEK cells, we still observed a significantly impaired function of the L555A and the L554A-L555A ABCG2 variants. These experiments indicate that these variants have a major folding problem, which does not only reduce their trafficking to the cell membrane but directly affects their substrate transport function as well.

2.2. Expression and Function of Human ABCG2 Variants Expressed in Sf9 Insect Cells

It has been shown that a baculovirus-based insect cell protein expression system can be successfully used for membrane protein expression even in the case of significant folding and processing problems of these proteins in mammalian cells [

26,

27]. Therefore, here we used Sf9 cells to express the Leu valve ABCG2 variants, and membrane vesicles were prepared from the baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells for functional characterization of these variants.

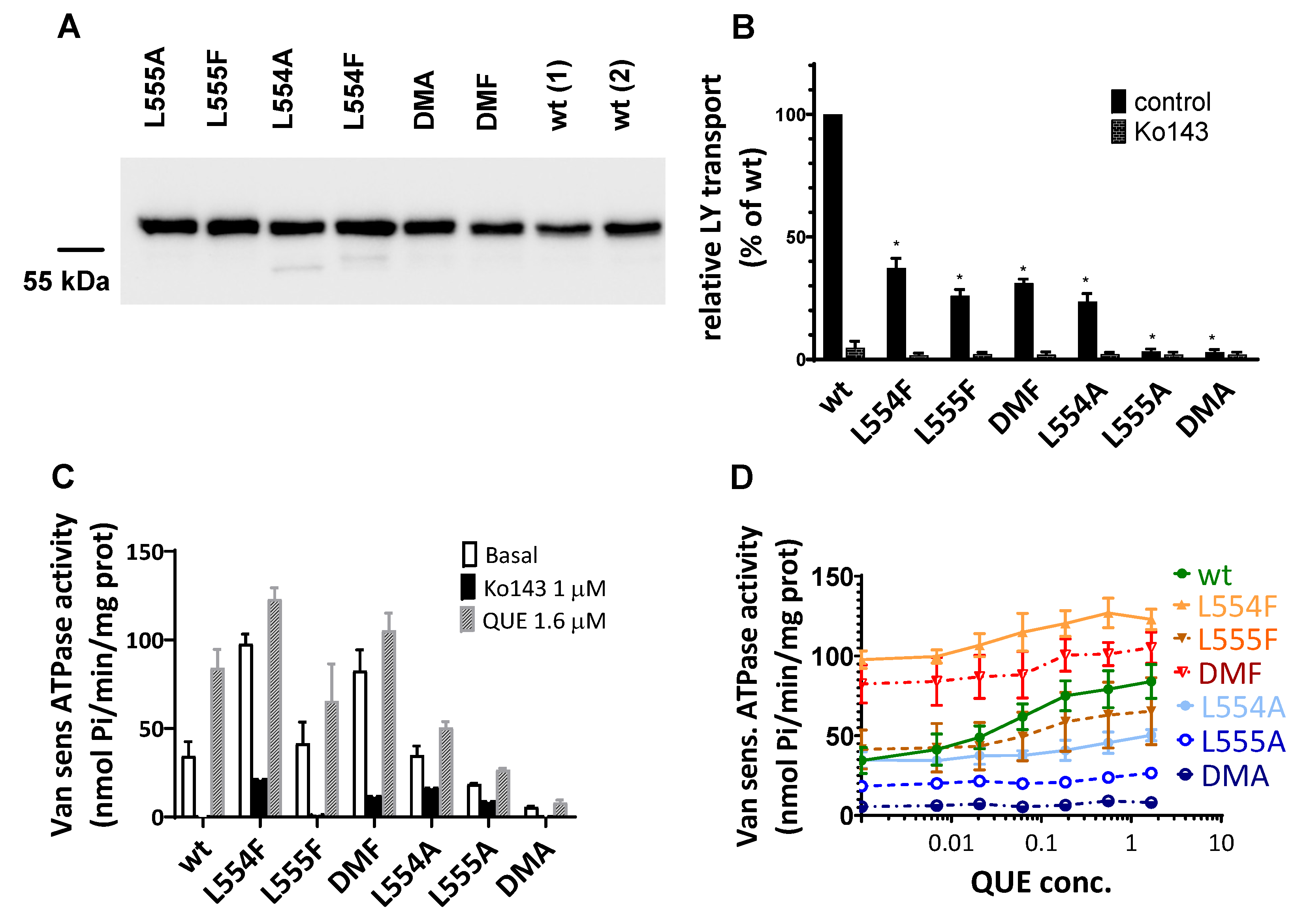

In Sf9 membrane ABCG2 variant expression was followed by western blot analysis. As shown in

Figure 4A, we found a high level and comparable expression for all the examined ABCG2 variants, similar to that of the wild type ABCG2. It should be mentioned that ABCG2 from Sf9 expression runs a bit lower in SDS-Page gels due to the shorter glycosylation produced by insect cells. Batch to batch variations may be significant when using this expression system, therefore two independent batches for the wild-type ABCG2 expression level are presented in the

Figure 4A.

Transport activity of the ABCG2 variants was measured in membrane vesicles by following an ATP-dependent lucifer yellow substrate uptake. Lucifer yellow (LY) is a relatively hydrophilic substrate transported by WT ABCG2, and some mutant variants (e.g. the R482G ABCG2) are unable to transport LY, although retaining Hoechst dye and mitoxantrone transport [

28]. The Sf9 cell membrane has a low cholesterol level which results in a low transport activity of ABCG2, and it has been shown that this transport activity can be greatly increased by loading cholesterol into the Sf9 membrane vesicles [

29]. In the present experiments cholesterol-cyclodextrin was applied for achieving this high ABCG2 transport activity (see Methods), while without added cholesterol all ABCG2 variants showed very low or undetectable transport activity (data not shown).

As shown in

Figure 4B most of the ABCG2 variants examined (L554F, L555F, DMF, L554A) showed active LY transport activity, except the L555A and DMA mutant variants. Still, as compared to the wild-type ABCG2 variant with similar membrane expression level, the L554F, L555F, DMF, and the L554A variants had only about one third of the LY transport activity. In all cases the specific inhibitor Ko143 abolished the ABCG2 mediated LY uptake into the membrane vesicles.

ABC multidrug transporters show a vanadate sensitive membrane ATPase activity connected to their transport function, therefore measuring this ATPase activity is a widely used method to follow drug interactions or functional changes in ABC transporter variants. As shown in

Figure 4C, most of the ABCG2 mutants examined here showed a significant vanadate sensitive and Ko143-inhibited basal ATPase activity, except the L555A (showing only a slight activity) and the DMA mutant, which had no such specific ATPase activity. Interestingly, this basal activity was relatively high (almost twice as high as that of the wild-type ABCG2) in the case of the L554F and the DMF variants.

Quercetin is a transported drug for ABCG2, and significantly stimulates the ATPase activity of the wild-type transporter [

20,

29]. As documented here (

Figure 4C), while the activity of the wild type ABCG2 is about 2.5 times higher in the presence of quercetin, this stimulation is much less in the case of the case of all L554 and L555 variants (although the L554F and the DMF variants have relatively high basal ATPase activity).

A similar phenomenon was observed when using prazosin, another ABCG2 substrate, for stimulation of the ATPase activity. In contrast to a major (2.5 x) stimulation of the wild-type ABCG2-ATPase, in the mutant variants prazosin had only a negligible stimulation of this ATPase (see below,

Table 1 and

Supplementary Figure S1).

In order to explore the potential differences in the quercetin-dependence of this ATPase activation, we have measured this effect at a wide range of quercetin concentrations (

Figure 4D). We found that the lack of significant quercetin activation of the L554F, the L555F and the L554F-L555F (DMF) variants was not due to a major shift in the concentration dependence of the ATPase activation but to a general quercetin insensitivity of this activity. Again, the L555A and the L554A-L555A (DMA) ABCG2 variants had low ATPase activity and no significant activation was observed in the whole range of quercetin concentrations.

Since membrane cholesterol has a significant stimulatory effect on the function of the ABCG2 transporter, we have also studied the cholesterol dependence of the ATPase activity of the variants. As shown in

Table 1 and in

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2, in the case of wild-type ABCG2, cholesterol loading of the Sf9 cell membranes had little effect on the basal ATPase activity, while the quercetin-stimulation or the prazosin-stimulation of the ATPase activities were significantly increased upon cholesterol loading. In the case of the L554F, the L555F, the L554F-L555F (DMF) and the L554A variants, cholesterol loading only slightly increased both the basal and the drug-stimulated ATPase activities, thus the influence of cholesterol was much less pronounced. In

Supplementary Figure S2 we show the effect of a few other known modulators and substrates on the ATPase activity of ABCG2 mutants. These auxiliary results, not discussed here in detail, are in accordance with the main experiments.

2.3. MD Simulations for the Leu-Valve Mutations in ABCG2

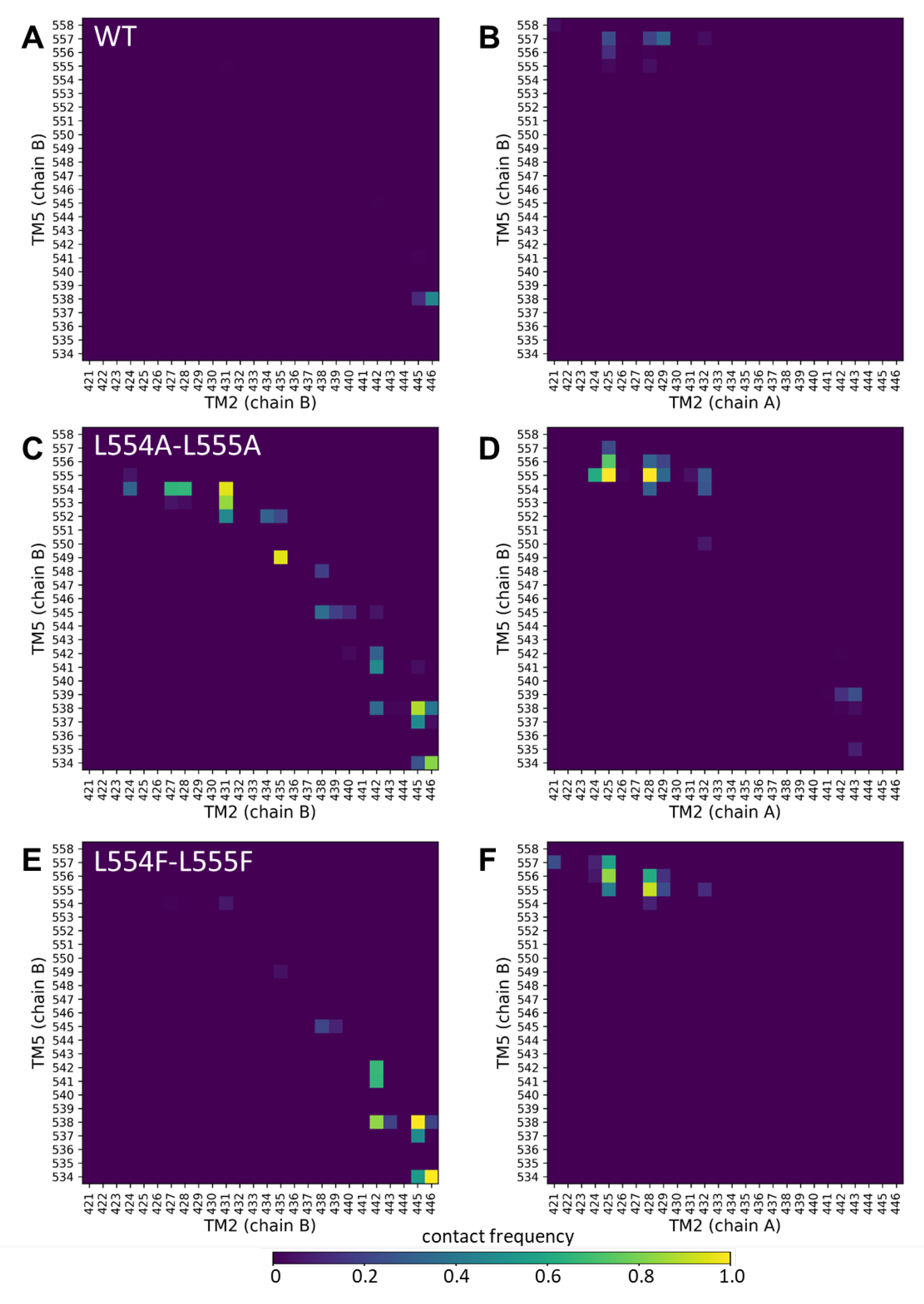

Since the mutations in the Leu-valve likely exert their effects on the orientation of the central four helices (TM2 and TM5 from both protomers), we performed molecular dynamics simulations with an inward-open conformation of ABCG2 (PDBID: 6HIJ, [

30]). The trajectories from these equilibrium simulations were stable and did not revealed differences in dynamic fluctuations of the WT, L554A-555A, and L554F-L555F constructs (

Supplementary Figure S3). Therefore, we explored contacts between the central helices, including TM2 and TM5 from one half, and TM2 and TM5 from the other half of the transporter, since static differences can be expected to develop along the simulations.

Only very few contacts with low frequencies were observed between the TM5 (chain B) and any of the TM2 (chain B or chain A) (

Figure 5A,B). Similarly, low contacts were detected between the TM5 (chain A) and TM2 helices (

Supplementary Figure S4A,B). Interestingly, the Ala mutations at positions 554 and 555 resulted in a highly increased number of non-native contacts between TM5 (chain B) and TM2 (chain B) from the same protomer (

Figure 5C).

Contacts at the extracellular ends between TM5 (chain B) and TM2 (chain A) from the opposite protomer were also increased in the L554A-L555A ABCG2 (e.g. 555A/N425 and 555A/G428) (

Figure 5D). The majority of the non-native contacts between TM5 (chain B) and TM2 (chain B) did not develop in the L554F-L555F ABCG2, except those between residues T538/V442, T538/F445, and V534/E446 (

Figure 5E). The non-native contacts present between the opposite TM2 and TM5 in L554A-L555A were also present in the L554F-L555F ABCG2 (

Figure 5F). All these phenomena were observed for interactions of the TM5 (chain A) from the other protomer (

Supplementary Figure S4). It is important to note that differences can be observed in dynamics and interactions of the two halves of the protein, in spite of the homomeric nature of the ABCG2 dimer, that may arise from the not completely symmetric initial structure.

3. Discussion

In the present study we performed an analysis of the potential role of the L554 and L555 residues in ABCG2, by generating and characterizing selected mutant variants both in mammalian and insect cell expression systems. These residues have been suggested to have important roles by forming a valve/plug-like structure in the drug transporting ABCG2 dimer [

14,

15,

19]. In other ABCG-type protein structures, in the corresponding positions leucines are often replaced by phenylalanine residues [

18,

31,

32], and in these cases the activity or the substrate specificity of the transporter were shown to be altered. The loops forming a hydrophobic gate in the corresponding region of ABCG1, a cholesterol and lipid transporter, contain phenylalanines [

18]. In the case of the ABCG5/G8 heterodimer protein, a cholesterol and sitosterol transporter, the corresponding residues (F576, M577 in ABCG8; and L549 in ABCG5) participate in a structure that probably serves the transport of flat sterol molecule [

18,

32]. Therefore, in this work we exchanged the L554 and L555 residues in ABCG2 with the relatively conservative phenylalanines and the structurally different alanine moieties.

We found that the L554F, L555F and L554F-L555F ABCG2 variants, when expressed in HEK293 cells, had similar total cellular or membrane expression levels to the WT ABCG2 protein. Also, the transport functions of these variants, when measuring Hoechst33342 or mitoxantrone extrusion, were similar to the wild-type ABCG2. However, in detailed functional studies, performed in an Sf9 insect cell expression system and using isolated membrane vesicles, we found a significantly decreased (although still cholesterol-dependent) Lucifer Yellow transport by these ABCG2 variants. Also, the L554F and L554F-L555F variants had elevated basal ATPase activities and lower levels of quercetin and prazosin stimulation, when compared to that in the WT protein.

These results indicate that the 554-555 phenylalanine variants of ABCG2 preserve the basic folding and trafficking features, and only subtle changes in the substrate recognition – hardly recognizable in a cellular system – may occur in the variants. Still, the insect cell expression results suggest that substrate binding/transport is compromised and a higher uncoupled ATPase activity can be observed in the L554F and L554F-L555F ABCG2 mutants.

In parallel experiments, when the Leucine residues 544 and 555 were mutated to alanine, in the HEK293 cell expression system we found that the cell surface expression and the transport function of the L554A variant were preserved, while the L555A, and especially the L554A-L555A ABCG2 variants suffered major folding and trafficking problems. Moreover, in experiments measuring the transport activity of these ABCG2 variants in HEK cells, sorted to have a similar, stable transporter expression, we observed an impaired Hoechst dye transport by the L555A, and especially the L554A-L555A variants. These results indicate that, in addition to the folding/trafficking problems, these L to A mutations also have a direct effect on the transport function of ABCG2.

In the Sf9 insect cell expression system, the L554A variant was functional but showing a lower level of substrate stimulation, and had a reduced Lucifer Yellow transport capacity. The L555A and the L554A-L555A mutant variants could also be properly expressed in the insect cells, while the specific substrate transport function and the related ATPase activity of these latter variants were practically lost. This loss of function suggests severe structural alterations in the L554A-L555A ABCG2 variant.

Our in silico molecular dynamics simulations support the above conclusions. While the L555F mutation exerted only minor effects on intramolecular contacts, our simulations highlighted large changes in residue contacts among the central helices in the L554A-L555A protein, when compared to the wild-type and L554F-L555F double mutant variants. The Ala mutations at positions 554 and 555 resulted in a highly increased number of non-native contacts between TM5 and TM2 helices

Our previous molecular dynamics studies [

33,

34], indicated that the orientation of the TM helices may play a role in substrate recognition and cholesterol regulation of ABCG2 function may also involve the TM helix orientation. In the R482G-ABCG2 variant the TH3 (transmembrane helix 3) moved closer to TH4 and drifted away from TH1 [

33], altering the shape of a potential lateral substrate binding pocket or interaction site. The presence of cholesterol in the membrane bilayer, which is also required for ABCG2 function, promoted the closure of the intracellular ends of ABCG2 [

34]. Similarly, in our current study the central TM helices exhibited altered conformation upon mutations in the “Leu-valve” region, affecting the available conformational space of the transporter, consequently altering transport properties.

Our current results underline the importance of this “valve” or “plug” region residues in the ABCG2 protein. They also suggest moderate changes in transport function and ATPase coupling of drug transport when leucines 544 and 555 are exchanged for phenylalanines and the L554F mutation had a more significant role in this respect. Our current results do not indicate a key role of these ABCG2 residues for substrate recognition, rather, they show a major effect on protein expression, folding and trafficking of the L554A, and L555A, especially the double mutant L554-L555A variants in mammalian cells, resulting in significantly less protein reaching the plasma membrane. These results also contradict a specific uncoupling effect of the transport and ATPase activity in the ABCG2 L555A variant, as suggested by [

19]. In fact, the combined expression and functional measurements suggest that in this variant, even if expressed at high levels, both substrate transport and ATPase activity are strongly impaired.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mammalian Expression System – Cell Culturing and Cell Line Generation

HEK293H cells were grown in DMEM/high glucose/GlutaMAX medium (Gibco, cat. 10569010) completed with 10% FBS (Gibco, cat. 1640071) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco, cat. 15070063) at 37 °C (5% CO

2). Transfection of HEK293 cells was carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, cat. 11668019) in Opti-MEM medium (Gibco, cat. 31985070), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The ABCG2-expressing stable cell lines were generated using the Sleeping Beauty transposon-transposase system. We used a 1:9 SB100X transposase coding plasmid: pT4 transposon plasmid ratio for transfection [

35]. Three days after transfection, the eGFP positive cells were sorted using BD FACS Aria II and seeded on 6-well plates. Another sort was performed after two more weeks of culturing.

4.2. ABCG2 Transport Function Measurements in Live Cells by Flow Cytometry

Hoechst 33342 (Hst, Thermo Fisher, cat. H1399) and mitoxantrone (Sigma Aldrich, cat. M2305000) uptake was determined on HEK293 stable cell lines. Cells were trypsinized and then preincubated for 5 minutes at 37 °C with or without 1 µM of the selective ABCG2 inhibitor, Ko143 (MedChemExpress, cat. HY-10010). Hoechst33342 dye (1 µM in all cases except stable cell lines, where 10 µM was used in cells sorted for equal high ABCG2 surface expression –

Figure 3B) or mitoxantrone (1 µM) was added to the cells and incubated at 37 °C for 20 minutes. Drug accumulation fluorescence (Hoechst or mitoxantrone) of the eGFP positive cells was measured using the violet laser (405 nm) and VL1 detector for Hoechst, and the red laser (637 nm) and RL1 detector for mitoxantrone accumulation on the Attune NxT Cytometer. MAF (Multidrug resistance activity factor) values were calculated from the median averaged fluorescence results the following way: MAF = (F(inh) – F (no inh))/F(inh), where F(inh) is the median of Hoechst or mitoxantrone fluorescence of the cells with the inhibitor, while F (no inh) is the fluorescence of the cells without the inhibitor.

4.3. ABCG2 Cell Surface Expression Level Measurements by Flow Cytometry

Antibody labeling was performed on trypsinized cells with the ABCG2-specific 5D3 mouse monoclonal antibody (gift of Bryan Sorrentino, Division of Experimental Hematology, Department of Hematology/Oncology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital). Ko143 is an ABCG2 inhibitor that has an impact on ABCG2 conformation thus helping 5D3 antibody recognition. 1 µM Ko143 was added to the samples before the antibody labeling. Alexa Fluor 647-labeled IgG2b (Thermo Fisher, cat. A-21242) was used as a secondary antibody. Measurements were carried out by the Attune NxT Cytometer after gating for live, EGFP positive cells.

4.4. Western Blot

Total protein from the HEK293 cells or Sf9 membranes was extracted by the addition of TE sample buffer (0.1 M TRIS-PO4, 4% SDS, 4 mM Na-EDTA, 40% glycerol, 0.04% bromophenol blue, and 0.04% β-mercaptoethanol; materials from Sigma-Aldrich). Equal amounts of the protein samples as determined by Lowry method were loaded on 7.5% (Sf9 membranes) or 10% (HEK) acrylamide gels. PVDF blots were probed with the following primary antibodies: anti-ABCG2 (BXP-21, Abcam, cat. ab3380), anti-β-actin (Sigma, cat. A1978). Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) HRP conjugate (Abcam, cat. ab97023) secondary antibody was used to visualize and quantify the results. Detection was performed with Clarity Western ECL Substrate (BioRad, cat. 1705060), detection was performed via the BioRad ChemiDoc Imaging System. Densitometry analysis was performed by ImageLab 6.0.1 (BioRad) and ImageJ software v1.42q.

4.5. Generation of ABCG2-Expressing Sf9 Insect Cells and Membrane Preparation

Sf9 insect cells were grown in suspension at 27°C in TNM-FH medium (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. T3285) supplemented with 5% FBS. ABCG2 variant expressing baculovirus vectors were constructed (pACUW vector, expression from p10 promoter as in our previous papers) and combined with Flashback ULTRA Kit (Oxford Expression Technologies Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Membrane fraction was prepared from infected cells after 72h by mechanical disruption and differential centrifugation method as described earlier [

27] and stored at -80

oC. Cholesterol content of the Sf9 membranes was increased by loading the membranes during membrane preparation procedure as described in [

29]. Total protein content was measured by Lowry method and ABCG2 expression was detected on western blot as described above.

4.6. ATPase Activity Measurement in ABCG2-Sf9 Membrane Vesicles

ATPase activity of WT ABCG2 and the mutant variants was measured by colorimetric detection of inorganic phosphate liberation in microplates, as described previously [

27,

36]. Protein concentrations (5 μg/well) were normalized according to western blots for ABCG2, thus equal amounts of the ABCG2 variants were used in the measurements. Cholesterol loading of the membranes was achieved by the addition of 0.6 mM RAMEβ-cholesterol (Cyclolab Ltd, Budapest, Hungary) before measurements, and the membranes were incubated for 10 min on ice, according to [

29]. The measurement of the ATPase activity was started with the addition of 3.1 mM MgATP, the samples incubated at 37°C and the reaction terminated after 25 minutes with the P-reagent. Photometric measurements were carried out in Victor Multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer) at 660 nm. ABC transporter specific activity was determined as vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity (1 mM of Na-vanadate was applied). ABCG2 specific ATPase activity was verified by adding the ABCG2 specific inhibitor Ko143 to the reaction. Other investigated drug compounds were applied in DMSO (final DMSO concentration was below 1% and this amount of DMSO had no effect on the results). Compounds (Merck) and concentrations are given in the main text.

4.7. Lucifer Yellow Transport Assay in ABCG2-Sf9 Membrane Vesicles

Sf9 membrane vesicles (30 μg protein/sample) were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min (without or with 4 mM of Mg-ATP) in 50 μL volume, in the presence of ABCG2 transporter specific fluorescent substrate 5 μM lucifer yellow (LY) Specificity and quality was controlled by reference inhibitor Ko143(1 μM). Mg-ATP (3 mM) dependent uptake was measured [

29]. After incubation, samples were rapidly filtered and washed on filter plates (MSFBN6B10, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Accumulated substrates in vesicles were resolved from the filter by 100 μL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate and centrifuged into another plate. A 100-μL volume of fluorescence stabilizer was added to the samples (DMSO). Fluorescence of the samples was measured by a plate reader (Victor X3 Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at appropriate wavelengths (405/535 nm) for LY. ABCG2 protein related transport was calculated by subtracting passive uptake measured without Mg-ATP.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments included at least 3 biological replicates with at least 2 technical parallel measurements. GraphPad Prism8 was used for data analysis and visualization. Western blot results, ABCG2 cell surface expression results and flow cytometry-based transport results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (95% confidence interval) was performed when comparing results to the wt-ABCG2 results. Columns marked with a star showed significant difference compared to the wt-ABCG2 (adjusted p-value<0.05).

4.9. Molecular Dynamics

The apo, inward-open ABCG2 structural model determined by cryo-EM (PDB ID: 6HIJ) was subjected to loop modelling [

30]. We favored this conformation, since the transmembrane helices of the ATP-bound structures are packed tightly, thus their movements are sterically limited and not reveal changes upon mutations on the time scale of molecular dynamics simulations. Shorter missing regions (a.a. 49-58, 302-327, and 355-368) were built using the standard loop modelling method of Modeller 9.23 [

37].

The input files for all steps (energy minimization, equilibration, and production run) were generated by the CHARMM-GUI web interface [

38,

39] by submitting the full-length WT structure, oriented according to the OPM database [

39]. The mutations were also introduced at CHARMM-GUI. The membrane bilayer was asymmetric containing 35:25:25:15 cholesterol:POPC:PLPC:SSM and 35:18:17:17:8:5 cholesterol:POPC:PLPC:POPE:POPS:DMPI25 (POPC: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine; PLPC: 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoylphosphatidylcholine; SSM: stearoyl-sphingomyelin; POPE: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylethanolamine; POPS: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylserine; DMPI25: Dimyristoylphosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate). 150 mM KCl in TIP3 water was used, grid information for PME (Particle-Mesh Ewald) electrostatics was generated automatically, and a temperature of 310 K was set. The structures were energy-minimized using the steepest descent integrator (maximum number to integrate: 50,000 or converged when force is <1,000 kJ/mol/nm). From the energy-minimized structures parallel equilibrium simulations (3 for each system) were forked, followed by production runs for 1 µs. Nosé-Hoover thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostat were applied. Electrostatic interactions were calculated using the fast smooth PME algorithm [

40] and the LINCS algorithm was used to constrain bonds [

41]. Constant particle number, pressure, and temperature ensembles with a time step of 2 fs were used. Simulations were performed with CHARMM36m force field using GROMACS 2020 [

42,

43].

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values were calculated using GROMACS tools. Contact maps were generated using the MDAnalysis Python package [

44]. RMSF and contact maps were derived from a trajectory obtained by merging the equilibrated portions (last 250 ns) of three parallel simulations. Plots were generated using the Matplotib Python package (10.1109/MCSE.2007.55).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary material S1.pdf.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization B.S. and T.H. and Á.T; investigation and formal analysis O.M. and K.S.Sz and A.B. and CS.K. and T.H., data curation: Á.T. and O.M. and T.H., methodology L.H. and GY.V., writing—original draft preparation O.M. and Á.T. and T.H., writing—review and editing B.S., supervision B.S. and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NRDIO/NKFIH grant numbers K137610, TKP2021-EGA-23, 2024-1.2.3-HU-RIZONT-2024-00003 (T.H.), K128123 (L.H.). Project no. KDP-1017403, (O.M.), has been implemented with support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the KDP-2020 funding scheme. This research has also been supported by a grant of 2024-1.1.1-KKV_FÓKUSZ-2024-00022.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

no acknowledgement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABC transporter |

ATP binding casette transporter |

| eGFP |

green fluorescent protein |

| IRES |

internal ribosome entry site |

| Cryo-EM |

cryo-electronmicroscopy |

| MAF |

multidrug resistance factor |

| LY |

lucifer yellow |

References

- Robey, R.W.; To, K.K.; Polgar, O.; Dohse, M.; Fetsch, P.; Dean, M.; Bates, S.E. ABCG2: a perspective. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2009, 61, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkadi, B.; Homolya, L.; Szakacs, G.; Varadi, A. Human multidrug resistance ABCB and ABCG transporters: participation in a chemoimmunity defense system. Physiological reviews 2006, 86, 1179–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkadi, B.; Homolya, L.; Hegedus, T. The ABCG2/BCRP transporter and its variants - from structure to pathology. FEBS letters 2020, 594, 4012–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maliepaard, M.; Scheffer, G.L.; Faneyte, I.F.; van Gastelen, M.A.; Pijnenborg, A.C.; Schinkel, A.H.; van De Vijver, M.J.; Scheper, R.J.; Schellens, J.H. Subcellular localization and distribution of the breast cancer resistance protein transporter in normal human tissues. Cancer research 2001, 61, 3458–3464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abbott, B.L. ABCG2 (BCRP) expression in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells. Hematological oncology 2003, 21, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Ross, D.D.; Nakanishi, T.; Bailey-Dell, K.; Zhou, S.; Mercer, K.E.; Sarkadi, B.; Sorrentino, B.P.; Schuetz, J.D. The stem cell marker Bcrp/ABCG2 enhances hypoxic cell survival through interactions with heme. The Journal of biological chemistry 2004, 279, 24218–24225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, K.; Katayama, K.; Mitsuhashi, J.; Sugimoto, Y. Functions of the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) in chemotherapy. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2009, 61, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakács, G.; Váradi, A.; Ozvegy-Laczka, C.; Sarkadi, B. The role of ABC transporters in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity (ADME-Tox). Drug discovery today 2008, 13, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robey, R.W.; Pluchino, K.M.; Hall, M.D.; Fojo, A.T.; Bates, S.E.; Gottesman, M.M. Revisiting the role of ABC transporters in multidrug-resistant cancer. Nature reviews Cancer 2018, 18, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Tseng, C.C.; Yen, J.H.; Chang, J.G.; Chou, W.C.; Chu, H.W.; Chang, S.J.; Liao, W.T. ABCG2 contributes to the development of gout and hyperuricemia in a genome-wide association study. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, S.W.; Brackman, D.J.; Ennis, E.A.; Sugiyama, Y.; Kamdem, L.K.; Blanchard, R.; Galetin, A.; Zhang, L.; Giacomini, K.M. Influence of Transporter Polymorphisms on Drug Disposition and Response: A Perspective From the International Transporter Consortium. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2018, 104, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillgren, K.M.; Keppler, D.; Zur, A.A.; Giacomini, K.M.; Stieger, B.; Cass, C.E.; Zhang, L.; International Transporter Consortium. Emerging transporters of clinical importance: an update from the International Transporter Consortium. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2013, 94, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamek-Gliszczynski, M.J.; Taub, M.E.; Chothe, P.P.; Chu, X.; Giacomini, K.M.; Kim, R.B.; Ray, A.S.; Stocker, S.L.; Unadkat, J.D.; Wittwer, M.B.; Xia, C.; Yee, S.W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; International Transporter Consortium. Transporters in Drug Development: 2018 ITC Recommendations for Transporters of Emerging Clinical Importance. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2018, 104, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, N.M.I.; Manolaridis, I.; Jackson, S.M.; Kowal, J.; Stahlberg, H.; Locher, K.P. Structure of the human multidrug transporter ABCG2. Nature 2017, 546, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolaridis, I.; Jackson, S.M.; Taylor, N.M.I.; Kowal, J.; Stahlberg, H.; Locher, K.P. Cryo-EM structures of a human ABCG2 mutant trapped in ATP-bound and substrate-bound states. Nature 2018, 563, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Ni, D.; Kowal, J.; Manolaridis, I.; Jackson, S.M.; Stahlberg, H.; Locher, K.P. Structures of ABCG2 under turnover conditions reveal a key step in the drug transport mechanism. Nature communications 2021, 12, 4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kinch, L.N.; Borek, D.M.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Urbatsch, I.L.; Xie, X.S.; Grishin, N.V.; Cohen, J.C.; Otwinowski, Z.; Hobbs, H.H.; Rosenbaum, D.M. Crystal structure of the human sterol transporter ABCG5/ABCG8. Nature 2016, 533, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarda, L.; Kowal, J.; Locher, K.P. Structure of the Human Cholesterol Transporter ABCG1. Journal of molecular biology 2021, 433, 167218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khunweeraphong, N.; Szollosi, D.; Stockner, T.; Kuchler, K. The ABCG2 multidrug transporter is a pump gated by a valve and an extracellular lid. Nature communications 2019, 10, 5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telbisz, A.; Hegedus, C.; Varadi, A.; Sarkadi, B.; Ozvegy-Laczka, C. Regulation of the function of the human ABCG2 multidrug transporter by cholesterol and bile acids: effects of mutations in potential substrate and steroid binding sites. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2014, 42, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegyi, Z.; Hegedus, T.; Homolya, L. The Reentry Helix Is Potentially Involved in Cholesterol Sensing of the ABCG1 Transporter Protein. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Siffert, A.; Torres, O.; Banasiak, J.; Pakuła, K.; Ziegler, J.; Rosahl, S.; Ferro, N.; Jasiński, M.; Hegedűs, T.; Geisler, M.M. A key residue of the extracellular gate provides quality control contributing to ABCG substrate specificity. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.; Wakabayashi, K.; Tamura, A.; Nakagawa, H.; Morishima, Y.; Osawa, Y.; Ishikawa, T. Major SNP (Q141K) variant of human ABC transporter ABCG2 undergoes lysosomal and proteasomal degradations. Pharmaceutical research 2009, 26, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarankó, H.; Tordai, H.; Telbisz, Á.; Özvegy-Laczka, C.; Erdős, G.; Sarkadi, B.; Hegedűs, T. Effects of the gout-causing Q141K polymorphism and a CFTR ΔF508 mimicking mutation on the processing and stability of the ABCG2 protein. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2013, 437, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zámbó, B.; Mózner, O.; Bartos, Z.; Török, G.; Várady, G.; Telbisz, Á.; Homolya, L.; Orbán, T.I.; Sarkadi, B. Cellular expression and function of naturally occurring variants of the human ABCG2 multidrug transporter. Cellular and molecular life sciences CMLS 2020, 77, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oers, M.M. Opportunities and challenges for the baculovirus expression system. Journal of invertebrate pathology 2011, 107, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozvegy, C.; Váradi, A.; Sarkadi, B. Characterization of drug transport, ATP hydrolysis, and nucleotide trapping by the human ABCG2 multidrug transporter. Modulation of substrate specificity by a point mutation. The Journal of biological chemistry 2002, 277, 47980–47990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedus, C.; Szakács, G.; Homolya, L.; Orbán, T.I.; Telbisz, A.; Jani, M.; Sarkadi, B. Ins and outs of the ABCG2 multidrug transporter: an update on in vitro functional assays. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2009, 61, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telbisz, A.; Müller, M.; Ozvegy-Laczka, C.; Homolya, L.; Szente, L.; Váradi, A.; Sarkadi, B. Membrane cholesterol selectively modulates the activity of the human ABCG2 multidrug transporter. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2007, 1768, 2698–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.M.; Manolaridis, I.; Kowal, J.; Zechner, M.; Taylor, N.M.I.; Bause, M.; Bauer, S.; Bartholomaeus, R.; Bernhardt, G.; Koenig, B.; Buschauer, A.; Stahlberg, H.; Altmann, K.H.; Locher, K.P. Structural basis of small-molecule inhibition of human multidrug transporter ABCG2. Nature structural molecular biology 2018, 25, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, F.; Farhat, D.; Gursu, G.; Samnani, S.; Lee, J.Y. Snapshots of ABCG1 and ABCG5/G8: A Sterol’s Journey to Cross the Cellular Membranes. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, C.S.; Yu, X.; Lee, J.; Vaish, A.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, M.; Wang, Z.; Min, X. Cryo-EM structure of ABCG5/G8 in complex with modulating antibodies. Communications biology 2021, 4, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- László, L.; Sarkadi, B.; Hegedűs, T. Jump into a New Fold-A Homology Based Model for the ABCG2/BCRP Multidrug Transporter. PloS one 2016, 11, e0164426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, T.; Tóth, Á.; Telbisz, Á.; Sarkadi, B.; Tordai, H.; Tordai, A.; Hegedűs, T. The transport pathway in the ABCG2 protein and its regulation revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. Cellular and molecular life sciences CMLS 2021, 78, 2329–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pryputniewicz-Dobrinska, D.; Nagy, E.; Kaufman, C.D.; Singh, M.; Yant, S.; Wang, J.; Dalda, A.; Kay, M.A.; Ivics, Z.; Izsvák, Z. Regulated complex assembly safeguards the fidelity of Sleeping Beauty transposition. Nucleic acids research 2017, 45, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkadi, B.; Price, E.M.; Boucher, R.C.; Germann, U.A.; Scarborough, G.A. Expression of the human multidrug resistance cDNA in insect cells generates a high activity drug-stimulated membrane ATPase. The Journal of biological chemistry 1992, 267, 4854–4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiser, A.; Sali, A. Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Methods Enzymol 2003, 374, 461–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.; Cheng, X.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Park, S.J.; Patel, D.S.; Beaven, A.H.; Lee, K.I.; Rui, H.; Park, S.; Lee, H.S.; Roux, B.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr.; Klauda, J.B.; Qi, Y.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI 10 years for biomolecular modeling and simulation. Journal of computational chemistry 2017, 38, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomize, M.A.; Lomize, A.L.; Pogozheva, I.D.; Mosberg, H.I. OPM: orientations of proteins in membranes database. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 623–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.C.; Fraaije, J.G.E.M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. Journal of computational chemistry 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nature methods 2017, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. Journal of computational chemistry 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud-Agrawal, N.; Denning, E.J.; Woolf, T.B.; Beckstein, O. MDAnalysis: a toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of computational chemistry 2011, 32, 2319–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).