1. Introduction

Cancer remains one of the most significant challenges in modern medicine, characterized by uncontrolled cell growth, invasion of surrounding tissues, and, in many cases, metastasis to distant organs[

1,

2]. Among the diverse array of cancers, glioblastoma (GBM) stands out as the most aggressive and lethal primary brain tumor in adults[

3]. Classified as a World Health Organization (WHO) grade IV glioma, GBM is marked by rapid proliferation, extensive infiltration into surrounding brain tissue, resistance to conventional therapies, and poor patient prognosis[

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Asymmetric cell division (ACD), a conserved mechanism for generating cellular diversity, has recently gained attention for its role in glioblastoma[

9]. Dysregulated ACD may contribute to GSC persistence, tumor growth, therapeutic resistance, and recurrence. ACD research offers insights into tumor growth and treatment resistance, highlighting potential therapeutic targets[

9]. This paper aims to close gaps in understanding the relationship between ACD and tumorigenesis, focusing on abnormal ACD mechanisms that contribute to malignancies.

This study conducted a literature review using PubMed publications from 2008 to the present. By analyzing regulatory control elements, we aim to provide insights into potential therapeutic strategies for glioblastoma.

2. Discovery of Asymmetric Cell Division

Edwin Conklin (1863–1952), an American biologist, was the first to observe that during the development of ascidian embryos, a distinct yellow-colored cytoplasm is unevenly distributed during cell division, leading to different cell fates in the daughter cells[

10]. This discovery provided the first demonstration of asymmetric cell division (ACD). This historical observation underscores the fundamental importance of cytoplasmic determinants in cell fate decisions, a concept that has since been recognized as a cornerstone in developmental biology[

11].

Despite Conklin’s observations over a century ago, the mechanistic understanding of ACD has progressed slowly. While the detailed mechanisms of ACD are beyond the scope of this paper, this paper will focus on its relevance to cancer initiation, tumor growth, progression, and potential therapeutic strategies. Understanding the relationship between ACD and cancer is crucial, as dysregulation in this process has been implicated in cancer stem cell maintenance and therapeutic resistance, particularly in aggressive cancers like glioblastoma.

3. The Mechanism of Asymmetric Cell Division

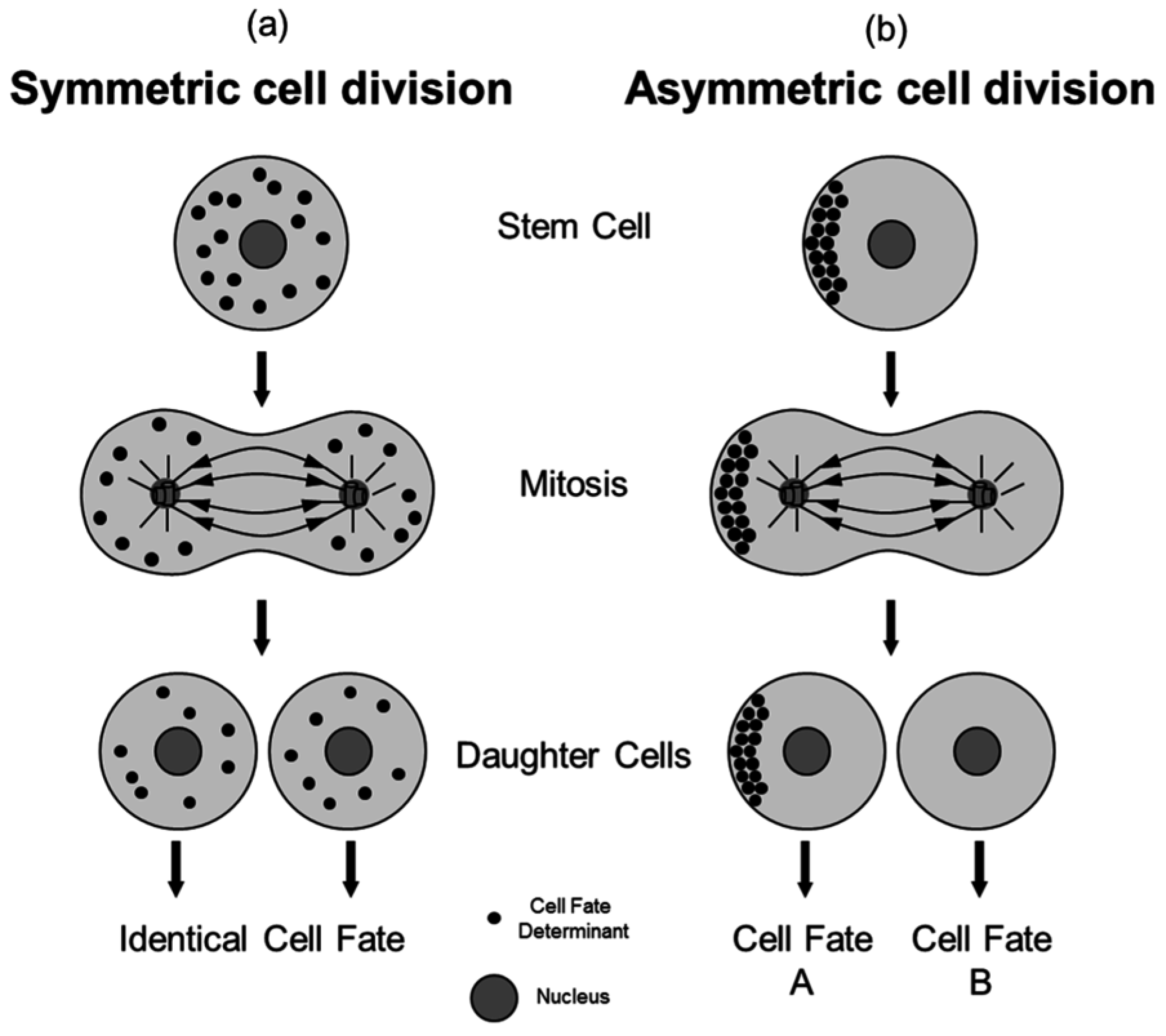

A key principle of ACD is the establishment of distinct sibling cell fates by mechanisms linked to mitosis (

Figure 1). This figure illustrates the fundamental differences between symmetric and asymmetric cell division. In panel (a), symmetric cell division (SCD) results in two daughter cells with identical fates, achieved through the equal distribution of cell fate determinants. In contrast, panel (b) depicts asymmetric cell division (ACD), where daughter cells inherit different amounts or compositions of cell fate determinants, resulting in distinct cell fates[

12].

Asymmetric fate can be established through exposure to cell-extrinsic signaling cues. Alternatively, asymmetric inheritance of cell-intrinsic cell fate determinants such as proteins or RNA can induce asymmetric cell fate decisions. ACD, a process through which a single cell divides into two distinct daughter cells, is critical for maintaining healthy stem cell populations and tissue integrity. ACD is particularly important within stem cell populations[

13]. Stem cells are specialized cells capable of dividing and differentiating into various cell types, contributing to tissue renewal and repair. They generate diverse cell types such as blood, bone, and muscle cells while simultaneously self-renewing to maintain their population. Importantly, stem cells play a crucial role in cancer treatment, particularly in hematological malignancies like blood cancers, as well as in regenerative medicine[

14].

The discovery of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies depends on unlocking the mechanisms of asymmetric cell division (ACD) together with its cancer-related functions. Cell differentiation, tissue homeostasis, and cancer development are intimately linked to the proper regulation of ACD. Dysregulation of this process can lead to tumorigenesis and therapeutic resistance, underscoring the importance of ongoing research in this field.

Figure 1.

Symmetric versus Asymmetric Cell Division. During a SCD [

15].

Figure 1.

Symmetric versus Asymmetric Cell Division. During a SCD [

15].

4. Relevance of Asymmetric Cell Division and Cancer

4.1. ACD and Tumorigenesis

Cancer is a complex, multifaceted disease characterized by uncontrolled cell growth and differentiation. It arises through the stepwise acquisition of genetic mutations that provide a survival advantage to affected cells. Cell cycle has been one of the most studied mechanisms in cancers[

16,

17]. Among the various processes that contribute to tumorigenesis, dysregulation of asymmetric cell division (ACD) plays a significant role in cancer initiation and progression[

18]. ACD is critical in normal tissues for maintaining tissue homeostasis and generating cellular diversity[

19]. Under physiological conditions, stem cells dynamically switch between symmetric cell division (SCD) and ACD to preserve homeostasis. This process requires highly coordinated intra- and extracellular signaling events. When dysregulated, however, asymmetric division increases the risk of malignant transformation[

20].

4.2. ACD in Stem and Progenitor Cells

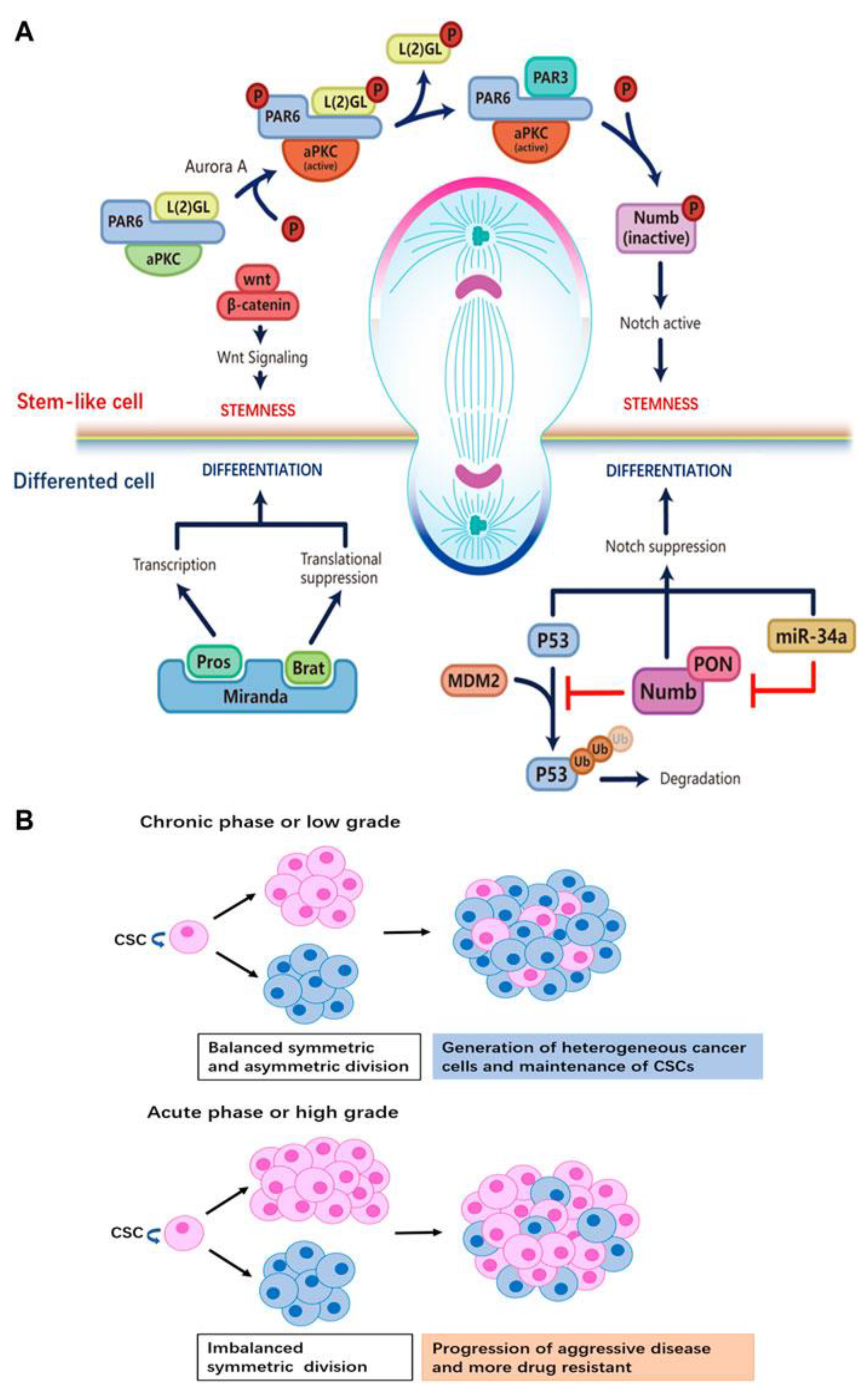

Stem and progenitor cells are defined by their self-renewal capacity and their ability to produce differentiated progeny (

Figure 3). A delicate balance between these processes is essential for developmental cellular diversity and adult tissue maintenance. Dysregulation of ACD disrupts this balance, potentially driving tumorigenesis by producing aggressive, fast-dividing daughter cell clones that are often resistant to treatment.

Emerging evidence supports the notion that ACD functions as a tumor-suppressive mechanism. Disruption of ACD in Drosophila neuroblasts has been associated with abnormal proliferation and genomic instability, suggesting its potential role in early carcinogenesis[

22]. Studies indicate that oncogenic mutations can hijack ACD pathways, disrupting mechanisms responsible for cell proliferation, cycle progression, and genomic integrity.

For example, Subhas Mukherjee et al. demonstrated that cancer stem cells (CSCs), which drive tumor initiation and propagation, often rely on symmetric divisions. Loss of ACD may thus result in tissue dysregulation, contributing to the development and growth of tumors. Aberrant ACD also promotes stem-like cell accumulation and limits differentiation, reinforcing cancer stemness[

23,

24].

4.3. ACD and Cancer Treatment Resistance

The dysregulation of ACD can generate daughter cells with enhanced treatment resistance, contributing to tumor heterogeneity. This phenomenon raises the clinically significant question: Can we target ACD mechanisms to improve cancer diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes?

Hitomi et al. discovered that ACD generates progeny with increased growth factor receptor expression, such as EGFR and p75NTR, conferring greater therapeutic resistance in glioblastoma CSCs. Similarly, resistance to radiation therapy (RT) in head and neck cancers has been linked to accelerated stem cell division and impaired asymmetric division, underscoring the relevance of ACD dysregulation in cancer treatment resistance[

20].

Figure 4.

Regulatory Mechanisms of ACD in CSCs and Their Impact on Tumor Progression[

20].

Figure 4.

Regulatory Mechanisms of ACD in CSCs and Their Impact on Tumor Progression[

20].

5. ACD in Glioblastoma

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a highly malignant brain tumor with limited treatment options and a median survival time of less than two years. Recent research highlights the relevance of ACD in glioblastoma progression and treatment response[

25].

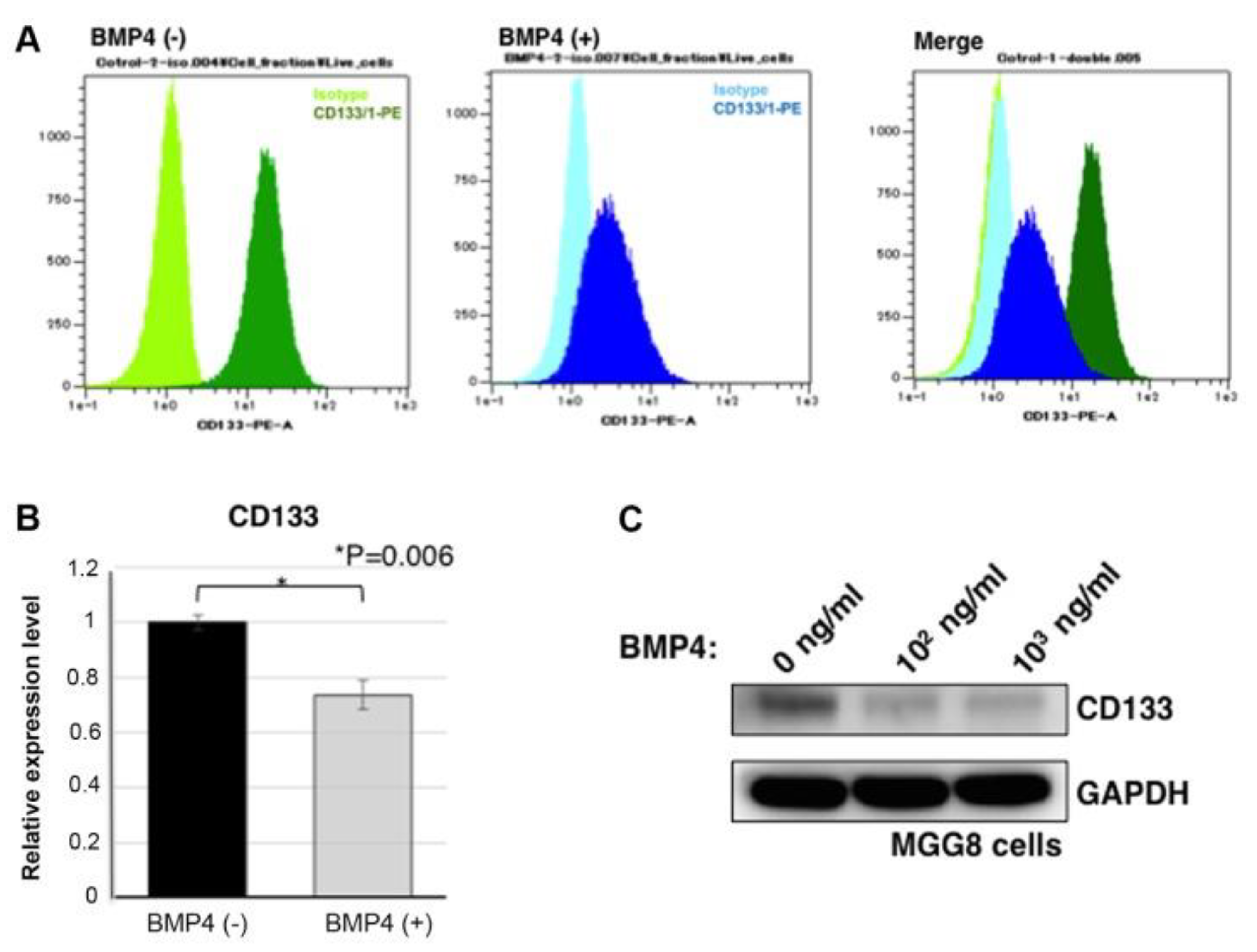

Koguchi et al. demonstrated that inducing ACD in glioblastoma stem-like cells (GSCs) via bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) treatment reduces cancer stemness. BMP4 suppresses CD133 expression, promotes differentiation, and shifts GSCs toward asymmetric division. These findings provide compelling evidence for the potential of 'ACD therapy' in GBM treatment.

Figure 5.

BMP4-Induced ACD and CD133 Downregulation in Glioblastoma Stem-Like Cells[

25].

Figure 5.

BMP4-Induced ACD and CD133 Downregulation in Glioblastoma Stem-Like Cells[

25].

Additionally, glioblastoma tumors often exhibit reduced TRIM3 protein expression, which normally regulates stem cell proliferation via ACD. Restoring TRIM3 levels reestablishes asymmetric division, reduces cancer stemness, and limits tumor growth. These findings emphasize the therapeutic potential of modulating ACD mechanisms in glioblastoma[

25].

6. Prospective and Future Directions

6.1. Molecular Mechanisms of ACD

Future research should focus on elucidating the intricate molecular signaling pathways that regulate ACD, including the roles of polarity proteins, spindle orientation, and cell-fate determinants.

6.2. ACD in Cancer Stem Cells

Investigating the relationship between ACD and cancer stem cells (CSCs) could provide insights into tumor initiation, progression, and resistance to therapies. Identifying molecular signatures of ACD dysregulation in CSCs may lead to novel diagnostic markers.

6.3. Therapeutic Targeting of ACD

Developing therapeutic strategies to modulate ACD, such as restoring asymmetric division in CSCs, holds promise for cancer treatment. For instance, targeting regulators like TRIM3 or employing BMP4-based therapies could be explored further.

6.4. ACD Dynamics Across Cancer Types

Comparative studies across different cancer types can uncover cancer-specific and universal aspects of ACD dysregulation, potentially leading to broad-spectrum or tailored therapeutic approaches.

6.5. Technological Advancements

Integrating single-cell analysis[

26,

27,

28,

29], RNA sequencing[

30,

31], confocal imaging[

32,

33], network-phrmacology [

34,

35], and patient-derived xenograft models[

36], CRISPR-based genetic manipulation[

37] could provide a more comprehensive understanding of ACD dynamics in cancer development.

6.7. Clinical Translation

Translating findings from preclinical models to clinical applications requires systematic investigation, including the development of biomarkers for ACD activity and patient stratification for personalized therapies.

7. Summary

ACD is fundamental to maintaining tissue homeostasis and cellular diversity[

12]. Dysregulation of this process is implicated in cancer initiation, progression, and treatment resistance. A deeper understanding of ACD's molecular underpinnings may facilitate the development of innovative diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions, potentially improving outcomes in cancers such as glioblastoma. By prioritizing these research areas proposed in this paper, scientists can further uncover the critical roles of ACD in cancer biology and develop innovative strategies to combat malignancies more effectively.

Author Contributions

Rebecca Golin conducted the review with Hengrui Liu. Rebecca Golin drafted the manuscript and Hengrui Liu edited the paper. Hengrui Liu supervised the project.

Funding

No funding received

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Weifen Chen, Zongxiong Liu, Yaqi Yang, and Bryan Liu for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

References

- Senga SS, Grose RP: Hallmarks of cancer-the new testament. Open biology 2021, 11, 200358.

- Sonkin D, Thomas A, Teicher BA: Cancer treatments: Past, present, and future. Cancer Genet 2024, 286-287, 18-24.

- Chen R, Smith-Cohn M, Cohen AL, Colman H: Glioma Subclassifications and Their Clinical Significance. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 284–297. [CrossRef]

- Wang LM, Englander ZK, Miller ML, Bruce JN: Malignant Glioma. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2023, 1405, 1–30.

- Wirsching HG, Galanis E, Weller M: Glioblastoma. Handb Clin Neurol 2016, 134, 381–397.

- Liu H, Weng J: A Comprehensive Bioinformatic Analysis of Cyclin-dependent Kinase 2 (CDK2) in Glioma. Gene 2022, 146325.

- Liu H, Weng J, Huang CL, Jackson AP: Is the voltage-gated sodium channel β3 subunit (SCN3B) a biomarker for glioma? Funct Integr Genomics 2024, 24, 162. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Tang T: A bioinformatic study of IGFBPs in glioma regarding their diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic prediction value. Am J Transl Res 2023, 15, 2140–2155.

- Hitomi M, Chumakova AP, Silver DJ, Knudsen AM, Pontius WD, Murphy S, Anand N, Kristensen BW, Lathia JD: Asymmetric cell division promotes therapeutic resistance in glioblastoma stem cells. JCI Insight 2021, 6.

- Gonzalez C: Centrosomes in asymmetric cell division. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2021, 66, 178–182. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Yamashita YM: Centrosome-centric view of asymmetric stem cell division. Open biology 2021, 11, 200314.

- Sunchu B, Cabernard C: Principles and mechanisms of asymmetric cell division. Development 2020, 147.

- Venkei ZG, Yamashita YM: Emerging mechanisms of asymmetric stem cell division. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 3785–3795. [CrossRef]

- Kochendoerfer AM, Modafferi F, Dunleavy EM: Centromere function in asymmetric cell division in Drosophila female and male germline stem cells. Open biology 2021, 11, 210107.

- Berika M, Elgayyar ME, El-Hashash AH: Asymmetric cell division of stem cells in the lung and other systems. Front Cell Dev Biol 2014, 2, 33.

- Li R, Xiao C, Liu H, Huang Y, Dilger JP, Lin J: Effects of local anesthetics on breast cancer cell viability and migration. BMC cancer 2018, 18, 666.

- Liu H, Dilger JP, Lin J: The Role of Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 7 (TRPM7) in Cell Viability: A Potential Target to Suppress Breast Cancer Cell Cycle. Cancers 2020, 12.

- Buss JH, Begnini KR, Lenz G: The contribution of asymmetric cell division to phenotypic heterogeneity in cancer. J Cell Sci 2024, 137.

- Morrison SJ, Kimble J: Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature 2006, 441, 1068–1074. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Zhang YY, Zhang H, Yang J, Chen Y, Lu H: Asymmetric Cell Division and Tumor Heterogeneity. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 938685.

- Evano B, Khalilian S, Le Carrou G, Almouzni G, Tajbakhsh S: Dynamics of Asymmetric and Symmetric Divisions of Muscle Stem Cells In Vivo and on Artificial Niches. Cell reports 2020, 30, 3195–3206.e3197. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Wu S, Yao R, Wei X, Ohlstein B, Guo Z: Eclosion muscles secrete ecdysteroids to initiate asymmetric intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. Dev Cell 2024, 59, 125–140.e112.

- Chao S, Yan H, Bu P: Asymmetric division of stem cells and its cancer relevance. Cell Regen 2024, 13, 5.

- Majumdar S, Liu ST: Cell division symmetry control and cancer stem cells. AIMS Mol Sci 2020, 7, 82–98. [CrossRef]

- Koguchi M, Nakahara Y, Ito H, Wakamiya T, Yoshioka F, Ogata A, Inoue K, Masuoka J, Izumi H, Abe T: BMP4 induces asymmetric cell division in human glioma stem-like cells. Oncol Lett 2020, 19, 1247–1254.

- Liu H, Dong A, Rasteh AM, Wang P, Weng J: Identification of the novel exhausted T cell CD8 + markers in breast cancer. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 19142.

- Liu H, Karsidag M, Chhatwal K, Wang P, Tang T: Single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing analysis reveals CENPA as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in cancers. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0314745.

- Li Y, Liu H: Clinical powers of Aminoacyl tRNA Synthetase Complex Interacting Multifunctional Protein 1 (AIMP1) for head-neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer biomarkers : section A of Disease markers 2022.

- Liu H, Li Y: Potential roles of Cornichon Family AMPA Receptor Auxiliary Protein 4 (CNIH4) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer biomarkers : section A of Disease markers 2022, 35, 439–450.

- Liu H, Li Y, Karsidag M, Tu T, Wang P: Technical and Biological Biases in Bulk Transcriptomic Data Mining for Cancer Research. Journal of Cancer 2025, 16, 34–43.

- Liu H, Guo Z, Wang P: Genetic expression in cancer research: Challenges and complexity. Gene Reports 2024, 102042.

- Ou L, Hao Y, Liu H, Zhu Z, Li Q, Chen Q, Wei R, Feng Z, Zhang G, Yao M: Chebulinic Acid isolated from Aqueous Extracts of Terminalia chebula Retz inhibits Helicobacter pylori infection by potential binding to cag A protein and regulating adhesion. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 15, 1416794.

- Ou L, Zhu Z, Hao Y, Li Q, Liu H, Chen Q, Peng C, Zhang C, Zou Y, Jia J et al: 1,3,6-Trigalloylglucose: A Novel Potent Anti-Helicobacter pylori Adhesion Agent Derived from Aqueous Extracts of Terminalia chebula Retz. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 29, 1161. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu Z, Rasteh AM, Dong A, Wang P, Liu H: Identification of molecular targets of Hypericum perforatum in blood for major depressive disorder: a machine-learning pharmacological study. Chinese Medicine 2024, 19, 141. [CrossRef]

- Hengrui L: An example of toxic medicine used in Traditional Chinese Medicine for cancer treatment. J Tradit Chin Med 2023, 43, 209–210.

- Li R, Huang Y, Liu H, Dilger JP, Lin J: Comparing volatile and intravenous anesthetics in a mouse model of breast cancer metastasis. In: Proceedings of the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2018. vol. 78: American Association for Cancer Research; 2018: 2162.

- Liu H, Wang P: CRISPR screening and cell line IC50 data reveal novel key genes for trametinib resistance. Clin Exp Med 2024, 25, 21. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).