Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

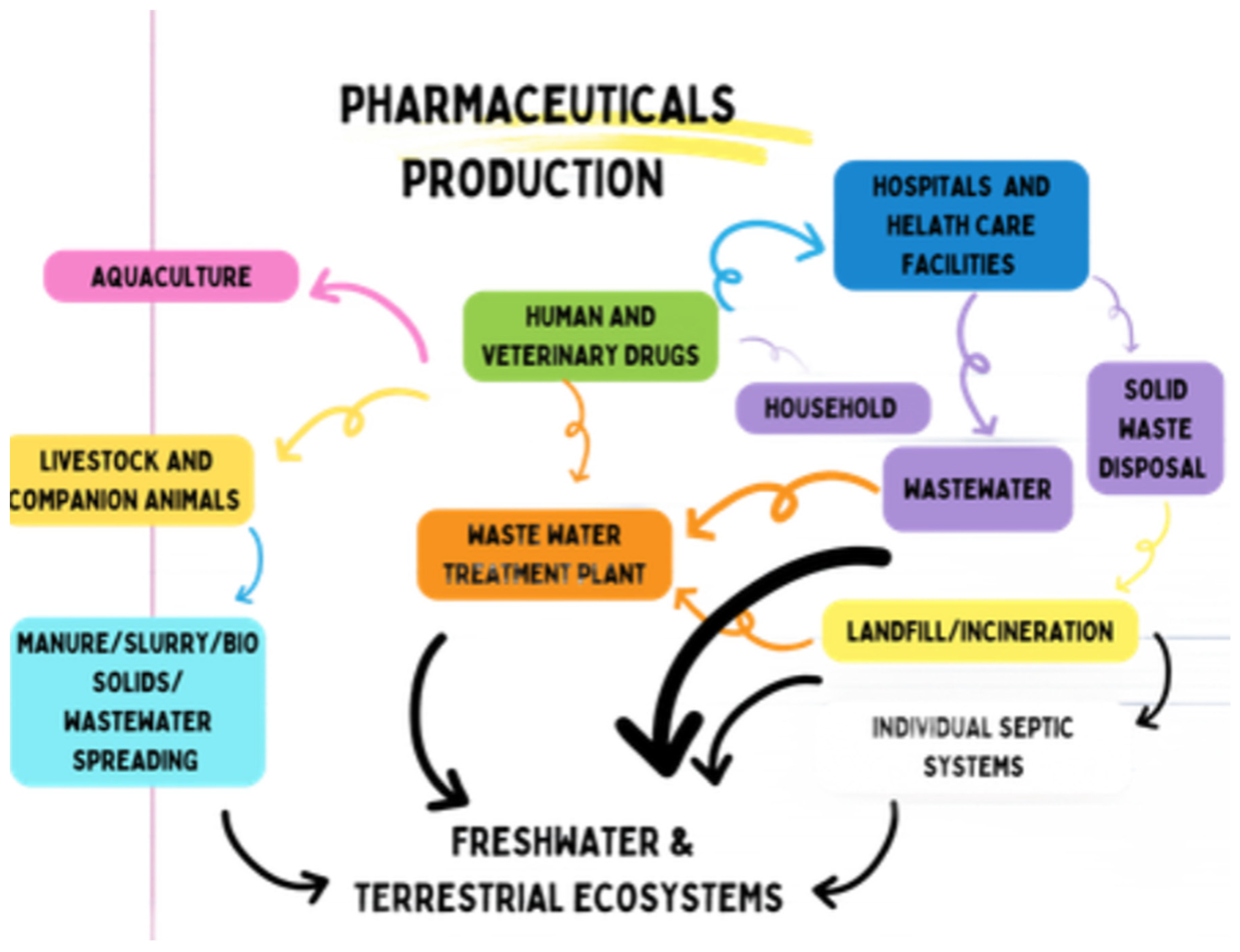

2. Sources and Distribution of Pharmaceuticals and Microplastics

2.1. Wastewater Discharge

2.1.1. Pharmaceuticals

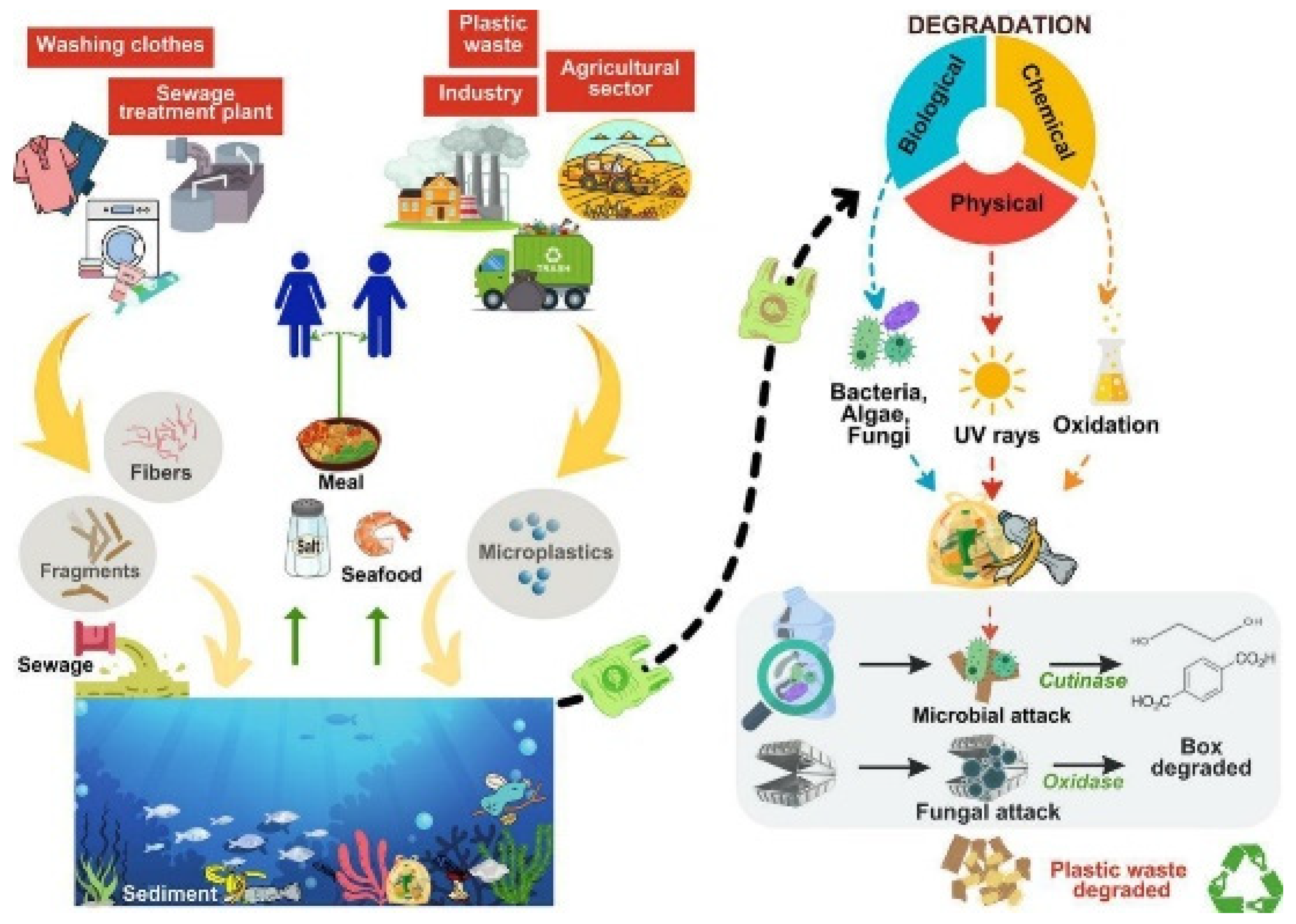

2.1.2. Microplatics

2.2. WWTP Effluents

2.2.1. Pharmaceuticals

2.2.2. Microplastics

2.3. Agricultural Runoff

2.3.1. Pharmaceuticals

2.3.2. Microplastics

2.4. Aquaculture Operations

2.4.1. Pharmaceuticals

2.4.2. Microplastics

2.5. Land Application of Biosolids

2.5.1. Pharmaceuticals

2.5.2. Microplastics

2.6. Atmospheric Deposition

2.6.1. Pharmaceuticals

2.6.2. Microplastics

3. Effects on Freshwater Fish

3.1. The Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification of Pharmaceuticals Within Freshwater Food Chains

3.2. Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification of Microplastics in Aquatic Food Chain

4. Physiological Effects on Fish, Encompassing Effects on Growth, Reproduction, Immune System Performance, and Behavioral Modifications

4.1. Pharmaceuticals

4.2. Microplastics

5. Impacts on Fish

5.1. Ecological Effects of Pharmaceuticals on Fish Populations

5.2. Ecological Effects of Microplastics on Fish Populations

6. Impact on Human Health

7. Conclusion

8. Recommendations

Improving Wastewater Treatment Technologies

Strengthening Public Health Policies

Raising Public Awareness and Education

Investing in Research and Innovation

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of Data and Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. H. Chaudry, “Evaluating non-point source microplastic pollution and its impact Evaluating non-point source microplastic pollution and its impact on biota in the Huron River on biota in the Huron River,” Eastern Michigan University, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://commons.emich.edu/theses.

- R. Naidu, V. A. Arias Espana, Y. Liu, and J. Jit, “Emerging contaminants in the environment: Risk-based analysis for better management,” Chemosphere, vol. 154, pp. 350–357, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Borrull, A. Colom, J. Fabregas, E. Pocurull, and F. Borrull, “A simple, fast method for the analysis of 20 contaminants of emerging concern in river water using large-volume direct injection liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry,” Anal Bioanal Chem, vol. 411, no. 8, pp. 1601–1610, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Česen, M. Ahel, S. Terzić, D. J. Heath, and E. Heath, “The occurrence of contaminants of emerging concern in Slovenian and Croatian wastewaters and receiving Sava river,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 650, pp. 2446–2453, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Fram and K. Belitz, “Occurrence and concentrations of pharmaceutical compounds in groundwater used for public drinking-water supply in California,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 409, no. 18, pp. 3409–3417, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen et al., “Antidepressants as emerging contaminants: Occurrence in wastewater treatment plants and surface waters in Hangzhou, China,” Front Public Health, vol. 10, p. 963257, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Carvalho et al., “Ciprofloxacin Concentrations in Aquatic Environments Cause Sublethal Effects on Males and Females Rhamdia Quelen after Long-Term Exposure,” 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Verlicchi, A. Galletti, M. Petrovic, and D. BarcelÓ, “Hospital effluents as a source of emerging pollutants: An overview of micropollutants and sustainable treatment options,” J Hydrol (Amst), vol. 389, no. 3–4, pp. 416–428, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Schwarzenbach et al., “The Challenge of Micropollutants in Aquatic Systems,” Science (1979), vol. 313, no. 5790, pp. 1072–1077, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- P. Sharma, L. Rani, A. S. Grewal, and A. L. Srivastav, “Impact of pharmaceuticals and antibiotics waste on the river ecosystem: a growing threat,” Ecological Significance of River Ecosystems: Challenges and Management Strategies, pp. 15–36, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Pharmaceutical Residues in Freshwater,” Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Shen, Y. Li, B. Song, C. Zhou, J. Gong, and G. Zeng, “Smoked cigarette butts: Unignorable source for environmental microplastic fibers,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 791, p. 148384, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Fick, H. Söderström, R. H. Lindberg, C. Phan, M. Tysklind, and D. G. J. Larsson, “Contamination of surface, ground, and drinking water from pharmaceutical production,” Environ Toxicol Chem, vol. 28, no. 12, pp. 2522–2527, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. D. McEachran, D. Shea, W. Bodnar, and E. G. Nichols, “Pharmaceutical Occurrence in Groundwater and Surface Waters in Forests Land-Applied with Municipal Wastewater,” Environmental toxicology and chemistry / SETAC, vol. 35, no. 4, p. 898, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

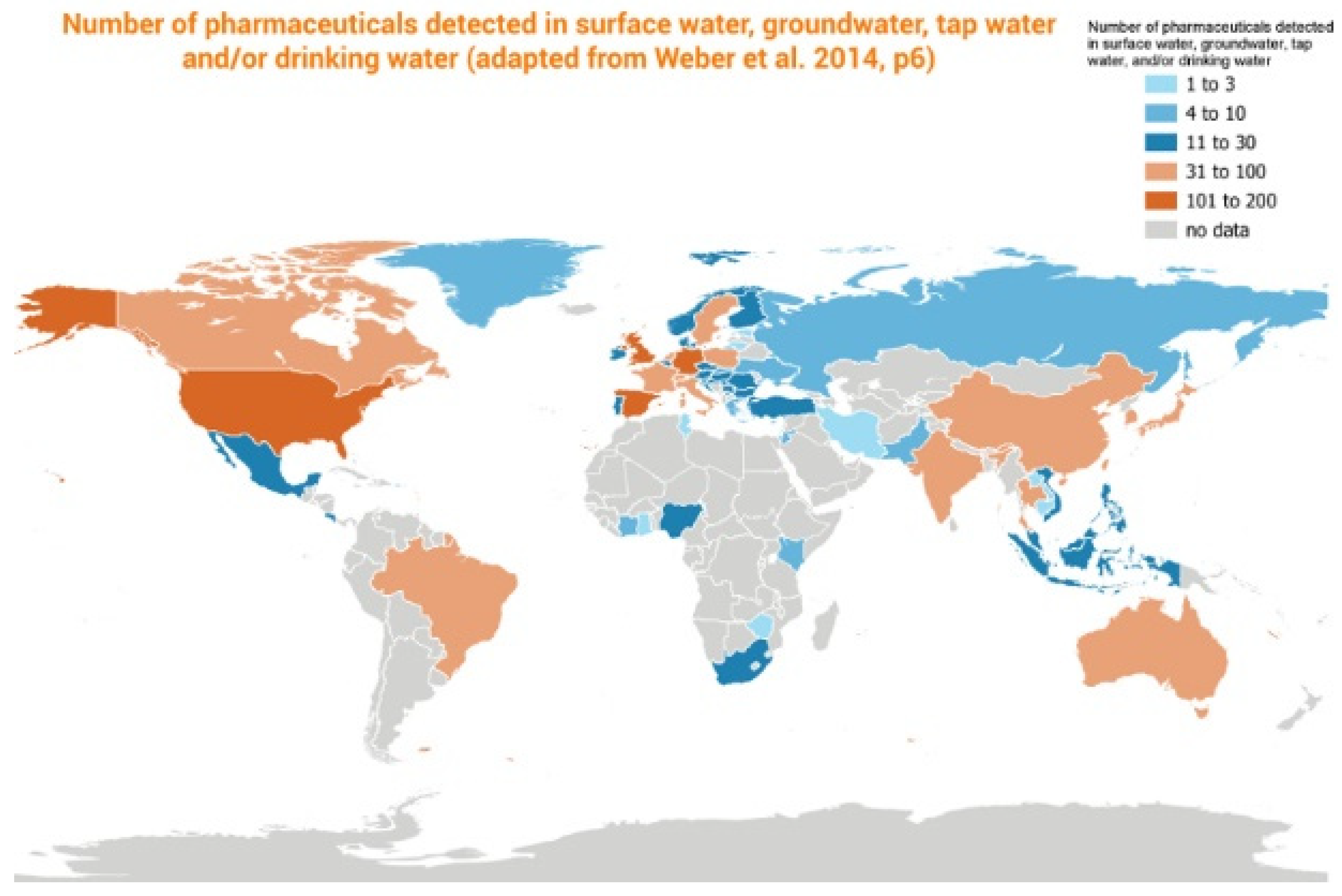

- R. Hernández-Tenorio, E. González-Juárez, J. L. Guzmán-Mar, L. Hinojosa-Reyes, and A. Hernández-Ramírez, “Review of occurrence of pharmaceuticals worldwide for estimating concentration ranges in aquatic environments at the end of the last decade,” Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, vol. 8, p. 100172, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tim aus der Beek, Frank-Andreas Weber, Axel Bergmann, and Gregor Grüttner, “(PDF) Pharmaceuticals in the environment: Global occurrence and potential cooperative action under the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM),” vol. 67, pp. 1862–4804, Sep. 2016, Accessed: Oct. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330934183_Pharmaceuticals_in_the_environment_Global_occurrence_and_potential_cooperative_action_under_the_Strategic_Approach_to_International_Chemicals_Management_SAICM/figures?lo=1&utm_source=google&utm_medium=organic.

- M. Clara, B. Strenn, O. Gans, E. Martinez, N. Kreuzinger, and H. Kroiss, “Removal of selected pharmaceuticals, fragrances and endocrine disrupting compounds in a membrane bioreactor and conventional wastewater treatment plants,” Water Res, vol. 39, no. 19, pp. 4797–4807, Nov. 2005. [CrossRef]

- L. Charuaud et al., “Veterinary pharmaceutical residues in water resources and tap water in an intensive husbandry area in France,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 664, pp. 605–615, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhou, G. Lu, Z. Yan, R. Jiang, X. Bao, and P. Lu, “A review of the influences of microplastics on toxicity and transgenerational effects of pharmaceutical and personal care products in aquatic environment,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 732, p. 139222, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Du et al., “A review of microplastics in the aquatic environmental: distribution, transport, ecotoxicology, and toxicological mechanisms,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 27, no. 11, pp. 11494–11505, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Hejna, D. Kapuścińska, and A. Aksmann, “Pharmaceuticals in the Aquatic Environment: A Review on Eco-Toxicology and the Remediation Potential of Algae,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, Vol. 19, Page 7717, vol. 19, no. 13, p. 7717, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Jain et al., “Microplastic pollution: Understanding microbial degradation and strategies for pollutant reduction,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 905, p. 167098, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Geyer, J. R. Jambeck, and K. L. Law, “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made,” Sci Adv, vol. 3, no. 7, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Carvalho and L. Santos, “Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: A review of the European scenario,” Environ Int, vol. 94, pp. 736–757, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Albarano et al., “Assessment of ecological risks posed by veterinary antibiotics in European aquatic environments: A comprehensive review and analysis,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 954, p. 176280, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Isidori, M. Lavorgna, A. Nardelli, L. Pascarella, and A. Parrella, “Toxic and genotoxic evaluation of six antibiotics on non-target organisms,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 346, no. 1–3, pp. 87–98, Jun. 2005. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Vivekanand, S. Mohapatra, and V. K. Tyagi, “Microplastics in aquatic environment: Challenges and perspectives,” Chemosphere, vol. 282, p. 131151, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Yu and S. Singh, “Microplastic Pollution: Threats and Impacts on Global Marine Ecosystems,” Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 13252, vol. 15, no. 17, p. 13252, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Ghosh, J. K. Sinha, S. Ghosh, K. Vashisth, S. Han, and R. Bhaskar, “Microplastics as an Emerging Threat to the Global Environment and Human Health,” Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 10821, vol. 15, no. 14, p. 10821, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Roursgaard, M. Hezareh Rothmann, J. Schulte, I. Karadimou, E. Marinelli, and P. Møller, “Genotoxicity of Particles From Grinded Plastic Items in Caco-2 and HepG2 Cells,” Front Public Health, vol. 10, p. 906430, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Palaniappan, C. M. Sadacharan, and B. Rostama, “Polystyrene and Polyethylene Microplastics Decrease Cell Viability and Dysregulate Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Markers of MDCK and L929 Cells In Vitro,” Expo Health, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 75–85, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. ; ; Diomede et al., “Microplastics Affect the Inflammation Pathway in Human Gingival Fibroblasts: A Study in the Adriatic Sea,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, Vol. 19, Page 7782, vol. 19, no. 13, p. 7782, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Fent, A. A. Weston, and D. Caminada, “Ecotoxicology of human pharmaceuticals,” Aquat Toxicol, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 122–159, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- L. H. M. L. M. Santos, A. N. Araújo, A. Fachini, A. Pena, C. Delerue-Matos, and M. C. B. S. M. Montenegro, “Ecotoxicological aspects related to the presence of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 175, no. 1–3, pp. 45–95, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. G. A. Barboza, L. R. Vieira, and L. Guilhermino, “Single and combined effects of microplastics and mercury on juveniles of the European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax): Changes in behavioural responses and reduction of swimming velocity and resistance time,” Environ Pollut, vol. 236, pp. 1014–1019, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Álvarez-Muñoz et al., “Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and endocrine disrupting compounds in macroalgaes, bivalves, and fish from coastal areas in Europe,” Environ Res, vol. 143, pp. 56–64, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Samal, S. Mahapatra, and M. Hibzur Ali, “Pharmaceutical wastewater as Emerging Contaminants (EC): Treatment technologies, impact on environment and human health,” Jun. 16, 2022, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- A. B. A. Boxall et al., “Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: What are the big questions?,” 2012, Public Health Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services. [CrossRef]

- J. Kazakova et al., “Monitoring of pharmaceuticals in aquatic biota (Procambarus clarkii) of the Doñana National Park (Spain),” J Environ Manage, vol. 297, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Ternes, M. Stumpf, J. Mueller, K. Haberer, R.-D. Wilken, and M. Servos, “Behavior and occurrence of estrogens in municipal sewage treatment plants I. Investigations in Germany, Canada and Brazil,” 1999.

- J. L. Santos, I. Aparicio, and E. Alonso, “Occurrence and risk assessment of pharmaceutically active compounds in wastewater treatment plants. A case study: Seville city (Spain),” Environ Int, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 596–601, 2007. [CrossRef]

- E. Zuccato, S. Castiglioni, R. Bagnati, M. Melis, and R. Fanelli, “Source, occurrence and fate of antibiotics in the Italian aquatic environment,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 179, no. 1–3, pp. 1042–1048, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Obimakinde, O. Fatoki, B. Opeolu, and O. Olatunji, “Veterinary pharmaceuticals in aqueous systems and associated effects: an update,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 3274–3297, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Pashaei, R. Dzingelevičienė, S. Abbasi, M. Szultka-Młyńska, and B. Buszewski, “Determination of the pharmaceuticals–nano/microplastics in aquatic systems by analytical and instrumental methods,” Feb. 01, 2022, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [CrossRef]

- R. Pashaei et al., “Pharmaceutical and Microplastic Pollution before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Surface Water, Wastewater, and Groundwater,” Oct. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- J. Radjenović, M. Petrović, and D. Barceló, “Fate and distribution of pharmaceuticals in wastewater and sewage sludge of the conventional activated sludge (CAS) and advanced membrane bioreactor (MBR) treatment,” Water Res, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 831–841, 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Verlicchi, A. Galletti, M. Petrovic, and D. BarcelÓ, “Hospital effluents as a source of emerging pollutants: An overview of micropollutants and sustainable treatment options,” Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. Mara and N. Horan, “Handbook of Water and Wastewater Microbiology,” 2003. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291139679.

- “82d18bbd088cd47b8eee58569f8f6a36”.

- D. Fatta-Kassinos, S. Meric, and A. Nikolaou, “Pharmaceutical residues in environmental waters and wastewater: Current state of knowledge and future research,” Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. H. M. L. M. Santos, A. N. Araújo, A. Fachini, A. Pena, C. Delerue-Matos, and M. C. B. S. M. Montenegro, “Ecotoxicological aspects related to the presence of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment,” Mar. 15, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y. Luo et al., “A review on the occurrence of micropollutants in the aquatic environment and their fate and removal during wastewater treatment,” Mar. 01, 2014, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- A. N. Shaik, T. Bohnert, D. A. Williams, L. L. Gan, and B. W. Leduc, “Mechanism of Drug-Drug Interactions between Warfarin and Statins,” J Pharm Sci, vol. 105, no. 6, pp. 1976–1986, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. N. Shaik et al., “Comparison of enzyme kinetics of warfarin analyzed by LC-MS/MS QTrap and differential mobility spectrometry,” J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci, vol. 1008, pp. 164–173, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Deblonde, C. Cossu-Leguille, and P. Hartemann, “Emerging pollutants in wastewater: A review of the literature,” Int J Hyg Environ Health, vol. 214, no. 6, pp. 442–448, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. J. S. Basha et al., “Concurrent determination of ezetimibe and its phase-I and II metabolites by HPLC with UV detection: Quantitative application to various in vitro metabolic stability studies and for qualitative estimation in bile,” J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci, vol. 853, no. 1–2, pp. 88–96, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. Björkblom et al., “Estrogenic and androgenic effects of municipal wastewater effluent on reproductive endpoint biomarkers in three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus a culeatus),” Environ Toxicol Chem, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 1063–1071, May 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Uddin, S. W. Fowler, and M. Behbehani, “An assessment of microplastic inputs into the aquatic environment from wastewater streams,” Mar Pollut Bull, vol. 160, no. June, p. 111538, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Yaseen, I. Assad, M. S. Sofi, M. Z. Hashmi, and S. U. Bhat, “A global review of microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Understanding their occurrence, fate and impact,” Environ Res, vol. 212, no. PB, p. 113258, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Sami, A. Hedström, E. Kvarnström, H. Österlund, K. Nordqvist, and I. Herrmann, “Treatment of greywater and presence of microplastics in on-site systems,” J Environ Manage, vol. 366, no. July, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Browne et al., “Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines woldwide: Sources and sinks,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 45, no. 21, pp. 9175–9179, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. L. Jang, J. Jeong, S. Eo, S. H. Hong, and W. J. Shim, “Occurrence and characteristics of microplastics in greywater from a research vessel,” Environmental Pollution, vol. 341, no. November 2023, p. 122941, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Farmer, “Handbook of Environmental Protection and Enforcement: Principles and Practice,” Handbook of Environmental Protection and Enforcement: Principles and Practice, pp. 1–279, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Ternes{, “OCCURRENCE OF DRUGS IN GERMAN SEWAGE TREATMENT PLANTS AND RIVERS*.”.

- T. Ternes et al., “Official partners of the POSEIDON project Associated end-user of the POSEIDON project Scientific Officer of the EU for POSEIDON,” 2001.

- J. Fick et al., “Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in the Environment CONTAMINATION OF SURFACE, GROUND, AND DRINKING WATER FROM PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTION”. [CrossRef]

- A. khalidi-idrissi et al., “Recent advances in the biological treatment of wastewater rich in emerging pollutants produced by pharmaceutical industrial discharges,” Oct. 01, 2023, Institute for Ionics. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Angeles et al., “Assessing pharmaceutical removal and reduction in toxicity provided by advanced wastewater treatment systems,” Environ Sci (Camb), vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 62–77, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Taoufik, W. Boumya, M. Achak, M. Sillanpää, and N. Barka, “Comparative overview of advanced oxidation processes and biological approaches for the removal pharmaceuticals,” Jun. 15, 2021, Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- B. Kasprzyk-Hordern, R. M. Dinsdale, and A. J. Guwy, “The occurrence of pharmaceuticals, personal care products, endocrine disruptors and illicit drugs in surface water in South Wales, UK,” Water Res, vol. 42, no. 13, pp. 3498–3518, 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. H. D. Tang and T. Hadibarata, “Microplastics removal through water treatment plants: Its feasibility, efficiency, future prospects and enhancement by proper waste management,” Environmental Challenges, vol. 5, no. August, p. 100264, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Kang, B. Ji, Y. Zhao, and T. Wei, “How can we trace microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: A review of the current knowledge on their analysis approaches,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 745, p. 140943, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Sun, X. Dai, Q. Wang, M. C. M. van Loosdrecht, and B. J. Ni, “Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Detection, occurrence and removal,” Water Res, vol. 152, pp. 21–37, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Murphy, C. Ewins, F. Carbonnier, and B. Quinn, “Wastewater Treatment Works (WwTW) as a Source of Microplastics in the Aquatic Environment,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 50, no. 11, pp. 5800–5808, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang and Y. Chen, “Effects of microplastics on wastewater and sewage sludge treatment and their removal: A review,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 382, no. July 2019, p. 122955, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Hollman, J. A. Dominic, G. Achari, C. H. Langford, and J. H. Tay, “Effect of UV dose on degradation of venlafaxine using UV/H2O2: perspective of augmenting UV units in wastewater treatment,” Environmental Technology (United Kingdom), vol. 41, no. 9, pp. 1107–1116, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gojkovic, R. H. Lindberg, M. Tysklind, and C. Funk, “Northern green algae have the capacity to remove active pharmaceutical ingredients,” Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, vol. 170, pp. 644–656, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Feier, I. Ionel, C. Cristea, and R. Sǎndulescu, “Electrochemical behaviour of several penicillins at high potential,” New Journal of Chemistry, vol. 41, no. 21, pp. 12947–12955, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. C. Li, “Occurrence, sources, and fate of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environment and soil,” Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Pal, K. Y. H. Gin, A. Y. C. Lin, and M. Reinhard, “Impacts of emerging organic contaminants on freshwater resources: Review of recent occurrences, sources, fate and effects,” Nov. 15, 2010. [CrossRef]

- B. Aomson, “Antibiotics in sediments and run-off waters from feedlots,” 1984.

- K. Sarmah, M. T. Meyer, and A. B. A. Boxall, “A global perspective on the use, sales, exposure pathways, occurrence, fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in the environment,” Oct. 2006. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Smalling et al., “Environmental fate of fungicides and other current-use pesticides in a central California estuary,” Mar Pollut Bull, vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 144–153, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Weston and M. J. Lydy, “Urban and agricultural sources of pyrethroid insecticides to the sacramento-san joaquin delta of California,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 1833–1840, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. H. M. L. M. Santos et al., “Contribution of hospital effluents to the load of pharmaceuticals in urban wastewaters: Identification of ecologically relevant pharmaceuticals,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 461–462, pp. 302–316, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. G. J. Larsson, C. de Pedro, and N. Paxeus, “Effluent from drug manufactures contains extremely high levels of pharmaceuticals,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 148, no. 3, pp. 751–755, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lan, C. Coetsier, C. Causserand, and K. Groenen Serrano, “An experimental and modelling study of the electrochemical oxidation of pharmaceuticals using a boron-doped diamond anode,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 333, pp. 486–494, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Loos et al., “Electrochemical oxidation of key pharmaceuticals using a boron doped diamond electrode,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 195, pp. 184–191, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Kumar, J. T. Lee, and J. Y. Cho, “Fate, occurrence, and toxicity of veterinary antibiotics in environment,” Dec. 01, 2012, Korean Society for Applied Biological Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- E. Popova, D. A. Bair, K. W. Tate, and S. J. Parikh, “Sorption, Leaching, and Surface Runoff of Beef Cattle Veterinary Pharmaceuticals under Simulated Irrigated Pasture Conditions,” J Environ Qual, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 1167–1175, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Bermúdez-Couso, D. Fernández-Calviño, M. A. Álvarez-Enjo, J. Simal-Gándara, J. C. Nóvoa-Muñoz, and M. Arias-Estévez, “Pollution of surface waters by metalaxyl and nitrate from non-point sources,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 461–462, pp. 282–289, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. B. A. Boxall, P. Johnson, E. J. Smith, C. J. Sinclair, E. Stutt, and L. S. Levy, “Uptake of veterinary medicines from soils into plants,” J Agric Food Chem, vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 2288–2297, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- W. C. Li, “Occurrence, sources, and fate of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environment and soil,” Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Okeke et al., “Microplastics in agroecosystems-impacts on ecosystem functions and food chain,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 177, no. September 2021, p. 105961, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Shah and W. Wu, Use of plastic mulch in agriculture and strategies to mitigate the associated environmental concerns, 1st ed., vol. 164. Elsevier Inc., 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. M. De Santisteban, J. Casalí, and J. J. López, “Assessing soil erosion rates in cultivated areas of Navarre (Spain),” Earth Surf Process Landf, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 487–506, 2006. [CrossRef]

- R. Rehm, T. Zeyer, A. Schmidt, and P. Fiener, “Soil erosion as transport pathway of microplastic from agriculture soils to aquatic ecosystems,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 795, p. 148774, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Rico et al., “Use of chemicals and biological products in Asian aquaculture and their potential environmental risks: A critical review,” Rev Aquac, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 75–93, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. Cunningham, J. Elliott, and P. Lees, Eds., Comparative and Veterinary Pharmacology, vol. 199. in Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, vol. 199. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010. [CrossRef]

- B. Halling-Sorensen, S. N. Nielsen, P. F. Lanzky, F. Ingerslev, H. C. H. Liitzhofl, and S. E. Jorgensen, “Occurrence, Fate and Effects of Pharmaceutical Substances in the Environment-A Review,” 1998.

- M. Aboubakr and A. Soliman, “Pharmacokinetics of danofloxacin in African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) after intravenous and intramuscular administrations,” Acta Vet Hung, vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 602–609, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Dudgeon et al., “Freshwater biodiversity: Importance, threats, status and conservation challenges,” May 2006. [CrossRef]

- P. Verlicchi, A. Galletti, M. Petrovic, and D. BarcelÓ, “Hospital effluents as a source of emerging pollutants: An overview of micropollutants and sustainable treatment options,” Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Diana, “Aquaculture production and biodiversity conservation,” Bioscience, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 27–38, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- X. Xiong, S. Xie, K. Feng, and Q. Wang, “Occurrence of microplastics in a pond-river-lake connection water system: How does the aquaculture process affect microplastics in natural water bodies,” J Clean Prod, vol. 352, no. April, p. 131632, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Skirtun, M. Sandra, W. J. Strietman, S. W. K. van den Burg, F. De Raedemaecker, and L. I. Devriese, “Plastic pollution pathways from marine aquaculture practices and potential solutions for the North-East Atlantic region,” Mar Pollut Bull, vol. 174, p. 113178, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Huntington, “Marine Litter and Aquaculture Gear,” White Paper. Report produced by Poseidon Aquatic Resources Management Ltd for the Aquaculture Stewardship Council, no. November, p. 20, 2019.

- M. Sandra et al., “Knowledge wave on marine litter from aquaculture sources,” D2.2 Aqua-Lit project, vol. 2, p. 136, 2020.

- “Editorial Drugs in the environment.”.

- M. S. Díaz-Cruz, M. J. López De Alda, and D. Barceló, “Environmental behavior and analysis of veterinary and human drugs in soils, sediments and sludge,” Jun. 01, 2003, Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- N. Kemper, “Veterinary antibiotics in the aquatic and terrestrial environment,” Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Lapworth, N. Baran, M. E. Stuart, and R. S. Ward, “Emerging organic contaminants in groundwater: A review of sources, fate and occurrence,” Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Martín, D. Camacho-Muñoz, J. L. Santos, I. Aparicio, and E. Alonso, “Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in wastewater and sludge from wastewater treatment plants: Removal and ecotoxicological impact of wastewater discharges and sludge disposal,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 239–240, pp. 40–47, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Md. S. Parvez, H. Ullah, O. Faruk, E. Simon, and H. Czédli, “Role of Microplastics in Global Warming and Climate Change: A Review,” Water Air Soil Pollut, vol. 235, no. 3, p. 201, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang et al., “Meta-analysis of the effects of microplastic on fish: Insights into growth, survival, reproduction, oxidative stress, and gut microbiota diversity,” Water Res, vol. 267, p. 122493, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Jambeck et al., “the Ocean : the Ocean :,” Marine pollution, vol. 347, no. 6223, pp. 768-, 2015.

- S. D. Kim, J. Cho, I. S. Kim, B. J. Vanderford, and S. A. Snyder, “Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals and endocrine disruptors in South Korean surface, drinking, and waste waters,” Water Res, vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 1013–1021, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Ferrey, M. Coreen Hamilton, W. J. Backe, and K. E. Anderson, “Pharmaceuticals and other anthropogenic chemicals in atmospheric particulates and precipitation,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 612, pp. 1488–1497, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Lafontaine et al., “Relative Influence of Trans-Pacific and Regional Atmospheric Transport of PAHs in the Pacific Northwest, U.S.,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 49, no. 23, pp. 13807–13816, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Landers et al., “The Western airborne contaminant assessment project (WACAP): An interdisciplinary evaluation of the impacts of airborne contaminants in Western U.S. national parks,” Feb. 01, 2010. [CrossRef]

- K. Thekla Kiffmeyer et al., “Vapour pressures, evaporation behaviour and airborne concentrations of hazardous drugs: implications for occupational safety,” 2002.

- “Mechanisms of atmospheric wet deposition of chemical contaminants | Health & Environmental Research Online (HERO) | US EPA.” Accessed: Apr. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://hero.epa.gov/hero/index.cfm/reference/details/reference_id/2181464.

- Y. Huang, X. Qing, W. Wang, G. Han, and J. Wang, “Mini-review on current studies of airborne microplastics: Analytical methods, occurrence, sources, fate and potential risk to human beings,” TrAC - Trends in Analytical Chemistry, vol. 125, p. 115821, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Ding, C. Sun, C. He, L. Zheng, D. Dai, and F. Li, “Atmospheric microplastics in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean: Distribution, source, and deposition,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 829, p. 154337, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Abbasi et al., “Microplastics captured by snowfall: A study in Northern Iran,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 822, p. 153451, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Szewc, B. Graca, and A. Dołęga, “Atmospheric deposition of microplastics in the coastal zone: Characteristics and relationship with meteorological factors,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 761, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Maack et al., “Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: Just One Stressor Among Others or Indicators for the Global Human Influence on Ecosystems?,” Mar. 01, 2022, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Wilkinson et al., “Pharmaceutical pollution of the world’s rivers,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 119, no. 8, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Sumpter, A. C. Johnson, and T. J. Runnalls, “Pharmaceuticals in the Aquatic Environment: No Answers Yet to the Major Questions,” Environ Toxicol Chem, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 589–594, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Meador, “Rationale and procedures for using the tissue-residue approach for toxicity assessment and determination of tissue, water, and sediment quality guidelines for aquatic organisms,” Dec. 01, 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Miller, M. Hamann, and F. J. Kroon, “Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of microplastics in marine organisms: A review and meta-analysis of current data,” Oct. 01, 2020, Public Library of Science. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, Z. Tan, J. Peng, Q. Qiu, and M. Li, “The behaviors of microplastics in the marine environment,” Mar Environ Res, vol. 113, pp. 7–17, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Sumpter and L. Margiotta-Casaluci, “Environmental Occurrence and Predicted Pharmacological Risk to Freshwater Fish of over 200 Neuroactive Pharmaceuticals in Widespread Use,” Toxics, vol. 10, no. 5, p. 233, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Daughton and T. A. Ternes, “Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: agents of subtle change?,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 107, no. SUPPL. 6, pp. 907–938, 1999. [CrossRef]

- B. W. Brooks et al., “DETERMINATION OF SELECT ANTIDEPRESSANTS IN FISH FROM AN EFFLUENT-DOMINATED STREAM,” 2005.

- M. Shen et al., “Occurrence, Bioaccumulation, Metabolism and Ecotoxicity of Fluoroquinolones in the Aquatic Environment: A Review,” Toxics, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 966, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Shenker, D. Harush, J. Ben-Ari, and B. Chefetz, “Uptake of carbamazepine by cucumber plants - A case study related to irrigation with reclaimed wastewater,” Chemosphere, vol. 82, no. 6, pp. 905–910, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xie, G. Lu, Z. Yan, J. Liu, P. Wang, and Y. Wang, “Bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of pharmaceuticals in food webs from a large freshwater lake,” Environmental Pollution, vol. 222, pp. 356–366, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. W. Brooks, T. M. Riley, and R. D. Taylor, “Water quality of effluent-dominated ecosystems: Ecotoxicological, hydrological, and management considerations,” Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Boethling and D. Mackay Boethling, “Property Estimation Methods for Chemicals Property Estimation Methods for Chemicals Property Estimation Methods for Chemicals.”.

- A. A. Koelmans, E. Besseling, A. Wegner, and E. M. Foekema, “Plastic as a carrier of POPs to aquatic organisms: A model analysis,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 47, no. 14, pp. 7812–7820, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang et al., “Bioaccumulation, trophic transfer, and human health risk of quinolones antibiotics in the benthic food web from a macrophyte-dominated shallow lake, North,” ElsevierL Zhang, S Qin, L Shen, S Li, J Cui, Y LiuScience of the total environment, 2020•Elsevier, Accessed: May 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004896972030067X.

- P. Sathishkumar, R. Meena, … T. P.-S. of the total, and undefined 2020, “Occurrence, interactive effects and ecological risk of diclofenac in environmental compartments and biota-a review,” ElsevierP Sathishkumar, RAA Meena, T Palanisami, V Ashokkumar, T Palvannan, FL GuScience of the total environment, 2020•Elsevier, Accessed: May 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969719340343.

- Z. Xie et al., “Occurrence, bioaccumulation, and trophic magnification of pharmaceutically active compounds in Taihu Lake, China,” ElsevierZ Xie, G Lu, J Liu, Z Yan, B Ma, Z Zhang, W ChenChemosphere, 2015•Elsevier, 2015, Accessed: May 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0045653515005706.

- Z. Xie et al., “Bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of pharmaceuticals in food webs from a large freshwater lake,” ElsevierZ Xie, G Lu, Z Yan, J Liu, P Wang, Y WangEnvironmental Pollution, 2017•Elsevier, 2017, Accessed: May 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749116310727.

- U. Anand et al., “Occurrence, transformation, bioaccumulation, risk and analysis of pharmaceutical and personal care products from wastewater: a review,” Environmental Chemistry Letters 2022 20:6, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 3883–3904, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Muir et al., “Bioaccumulation of pharmaceuticals and personal care product chemicals in fish exposed to wastewater effluent in an urban wetland,” Scientific Reports 2017 7:1, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. Gong, and B. C. Kelly, “Bioaccumulation Behavior of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Adult Zebrafish (Danio rerio): Influence of Physical-Chemical Properties and Biotransformation,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 51, no. 19, pp. 11085–11095, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Arnnok, R. R. Singh, R. Burakham, A. Pérez-Fuentetaja, and D. S. Aga, “Selective Uptake and Bioaccumulation of Antidepressants in Fish from Effluent-Impacted Niagara River,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Du et al., “Bioaccumulation and trophic dilution of human pharmaceuticals across trophic positions of an effluent-dependent wadeable stream,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 369, no. 1656, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Haddad, A. Luek, W. Scott, … G. S.-J. of hazardous, and undefined 2018, “Spatio-temporal bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of ionizable pharmaceuticals in a semi-arid urban river influenced by snowmelt,” ElsevierSP Haddad, A Luek, WC Scott, GN Saari, SR Burket, LA Kristofco, J CorralesJournal of hazardous materials, 2018•Elsevier, 2018, Accessed: May 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304389418305934.

- A. Lagesson, J. Fahlman, T. Brodin, … J. F.-S. of the T., and undefined 2016, “Bioaccumulation of five pharmaceuticals at multiple trophic levels in an aquatic food web-Insights from a field experiment,” ElsevierA Lagesson, J Fahlman, T Brodin, J Fick, M Jonsson, P Byström, J KlaminderScience of the Total Environment, 2016•Elsevier, 2016, Accessed: May 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969716311445.

- M. Heynen, J. Fick, M. Jonsson, J. Klaminder, and T. Brodiny, “Effect of bioconcentration and trophic transfer on realized exposure to oxazepam in 2 predators, the dragonfly larvae (Aeshna grandis) and the Eurasian perch (Perca,” Wiley Online LibraryM Heynen, J Fick, M Jonsson, J Klaminder, T BrodinEnvironmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2016•Wiley Online Library, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 930–937, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Richmond et al., “A diverse suite of pharmaceuticals contaminates stream and riparian food webs,” Nature Communications 2018 9:1, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Sokołowski et al., “Bioaccumulation of pharmaceuticals and stimulants in macrobenthic food web in the European Arctic as determined using stable isotope approach,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 909, p. 168557, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Vasquez, A. Lambrianides, M. Schneider, K. Kümmerer, and D. Fatta-Kassinos, “Environmental side effects of pharmaceutical cocktails: What we know and what we should know,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 279, pp. 169–189, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- O. Frédéric and P. Yves, “Pharmaceuticals in hospital wastewater: Their ecotoxicity and contribution to the environmental hazard of the effluent,” Chemosphere, vol. 115, no. 1, pp. 31–39, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Du et al., “Environmental fate and impacts of microplastics in aquatic ecosystems: A review,” RSC Adv, vol. 11, no. 26, pp. 15762–15784, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Gao, S. Zhang, Z. Feng, J. Lu, and G. Fu, “The bio – accumulation and – magnification of microplastics under predator – prey isotopic relationships,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 480, no. July, p. 135896, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. E. McHale and K. L. Sheehan, “Bioaccumulation, transfer, and impacts of microplastics in aquatic food chains,” Journal of Environmental Exposure Assessment, vol. 3, no. 3, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Wright, R. C. Thompson, and T. S. Galloway, “The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: a review.,” Environ Pollut, vol. 178, pp. 483–492, 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. Srivastava, P. R.-Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res, and undefined 2021, “Impacts of human pharmaceuticals on fish health,” researchgate.net, vol. 12, no. 10, p. 5185, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Sih, A. M. Bell, J. C. Johnson, and R. E. Ziemba, “Behavioral Syndromes: An Integrative Overview,”, vol. 79, no. 3, pp. 241–277, Sep. 2004. [CrossRef]

- D. Réale and M. Festa-Bianchet, “Predator-induced natural selection on temperament in bighorn ewes,” Anim Behav, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 463–470, Mar. 2003. [CrossRef]

- B. R. Smith and D. T. Blumstein, “Fitness consequences of personality: a meta-analysis,” Behavioral Ecology, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 448–455, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Woodward, “Biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and food webs in fresh waters: assembling the jigsaw puzzle,” Freshw Biol, vol. 54, no. 10, pp. 2171–2187, Oct. 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Reid et al., “Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity,” Biological Reviews, vol. 94, no. 3, pp. 849–873, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Scott and K. A. Sloman, “The effects of environmental pollutants on complex fish behaviour: integrating behavioural and physiological indicators of toxicity,” Aquatic Toxicology, vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 369–392, Jul. 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Melvin and S. P. Wilson, “The utility of behavioral studies for aquatic toxicology testing: A meta-analysis,” Chemosphere, vol. 93, no. 10, pp. 2217–2223, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Vaudin, C. Augé, N. Just, S. Mhaouty-Kodja, S. Mortaud, and D. Pillon, “When pharmaceutical drugs become environmental pollutants: Potential neural effects and underlying mechanisms,” Environ Res, vol. 205, p. 112495, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Ohtake et al., “Modulation of oestrogen receptor signalling by association with the activated dioxin receptor,” Nature 2003 423:6939, vol. 423, no. 6939, pp. 545–550, May 2003. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Heath, G. K. Iwama, A. D. Pickering, J. P. Sumpter, and C. B. Schreck, “Fish stress and health in aquaculture,” Estuaries, vol. 21, no. 3, p. 501, Sep. 1998. [CrossRef]

- G. Van Der Kraak, “observations of endocrine effects in wildlife with evidence of their causation,” Pure & Appl. Chem, vol. 70, pp. 1785–1794, 1998.

- D.E. Kime et al., “Use of computer assisted sperm analysis (CASA) for monitoring the effects of pollution on sperm quality of fish; application to the effects of heavy metals,” Aquatic Toxicology, vol. 36, pp. 223–237, 1996.

- C. R. Tyler, S. Jobling, J. P. Sumpter, and C. Tyler, “Endocrine Disruption in Wildlife: A Critical Review of the Evidence,” 1998.

- J. and M. P. G. Louis J. Guillette, “Alterations in development of reproductive and endocrine systems of wildlife populations exposed to endocrine-disrupting contaminants,” Reproduction, vol. 122, pp. 857–864, 2001.

- J. P. Nash et al., “Long-term exposure to environmental concentrations of the pharmaceutical ethynylestradiol causes reproductive failure in fish,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 112, no. 17, pp. 1725–1733, Dec. 2004. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Grieshaber et al., “Relation of contaminants to fish intersex in riverine sport fishes,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 643, pp. 73–89, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Johnson and R. J. Williams, “A model to estimate influent and effluent concentrations of estradiol, estrone, and ethinylestradiol at sewage treatment works,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 38, no. 13, pp. 3649–3658, Jul. 2004. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Tyler, S. Jobling, J. P. Sumpter, and C. Tyler, “Endocrine Disruption in Wildlife: A Critical Review of the Evidence,” 1998.

- J. M. Martin et al., “Impact of the widespread pharmaceutical pollutant fluoxetine on behaviour and sperm traits in a freshwater fish,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 650, pp. 1771–1778, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Haubruge, F. Petit, and M. J. G. Gage, “Reduced sperm counts in guppies (Poecilia reticulata) following exposure to low levels of tributyltin and bisphenol A,” Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, vol. 267, no. 1459, pp. 2333–2337, Nov. 2000. [CrossRef]

- T Colborn, “Chemically Induced Alterations in Sexual and Functional Development: The Wildlife/Human Connection,” Princeton Scientific Publishing, 1992, Accessed: May 09, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Bern+HA+1992.+The+fragile+fetus.+In%3A+Chemically-Induced+Alterations+in+Sexual+and+Functional+Development%3A+The+Wildlife+Human+Connection+%28Colborn+T%2C+Clement+C%2C+eds%29.+Princeton%2C+NJ%3APrinceton+Scientific+Publishing%2C+9%E2%80%9315.

- A. Dawson, “Comparative reproductive physiology of non-mammalian species,” Pure and Applied Chemistry, vol. 70, no. 9, pp. 1657–1669, Sep. 1998. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Strüssmann and M. Nakamura, “Morphology, endocrinology, and environmental modulation of gonadal sex differentiation in teleost fishes,” Fish Physiol Biochem, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 13–29, 2002. [CrossRef]

- R. Länge et al., “Effects of the synthetic estrogen 17α-ethinylestradiol on the life-cycle of the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas),” Environ Toxicol Chem, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 1216–1227, Jun. 2001. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Meston and P. F. Frohlich, “The Neurobiology of Sexual Function,” Arch Gen Psychiatry, vol. 57, no. 11, pp. 1012–1030, Nov. 2000. [CrossRef]

- L. Gunnarsson, A. Jauhiainen, E. Kristiansson, O. Nerman, and D. G. J. Larsson, “Evolutionary conservation of human drug targets in organisms used for environmental risk assessments,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 42, no. 15, pp. 5807–5813, Aug. 2008. [CrossRef]

- N. Kreke and D. R. Dietrich, “Physiological Endpoints for Potential SSRI Interactions in Fish,” Crit Rev Toxicol, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 215–247, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. Lillesaar, “The serotonergic system in fish,” J Chem Neuroanat, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 294–308, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Michelangeli, C. R. Smith, B. B. M. Wong, and D. G. Chapple, “Aggression mediates dispersal tendency in an invasive lizard,” Anim Behav, vol. 133, pp. 29–34, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Cote, S. Fogarty, K. Weinersmith, T. Brodin, and A. Sih, “Personality traits and dispersal tendency in the invasive mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis),” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 277, no. 1687, pp. 1571–1579, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. D. McDonald, “An AOP analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for fish,” Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology, vol. 197, pp. 19–31, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Fursdon, J. M. Martin, M. G. Bertram, T. K. Lehtonen, and B. B. M. Wong, “The pharmaceutical pollutant fluoxetine alters reproductive behaviour in a fish independent of predation risk,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 650, pp. 642–652, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. B. Chapman et al., “To boldly go: Individual differences in boldness influence migratory tendency,” Ecol Lett, vol. 14, no. 9, pp. 871–876, 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Brodin, S. Piovano, J. Fick, J. Klaminder, M. Heynen, and M. Jonsson, “Ecological effects of pharmaceuticals in aquatic systems—impacts through behavioural alterations,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 369, no. 1656, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Brodin, J. Fick, M. Jonsson, and J. Klaminder, “Dilute concentrations of a psychiatric drug alter behavior of fish from natural populations,” Science (1979), vol. 339, no. 6121, pp. 814–815, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. Stanley, A. J. Ramirez, C. K. Chambliss, and B. W. Brooks, “Enantiospecific sublethal effects of the antidepressant fluoxetine to a model aquatic vertebrate and invertebrate,” Chemosphere, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 9–16, Aug. 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Gaworecki and S. J. Klaine, “Behavioral and biochemical responses of hybrid striped bass during and after fluoxetine exposure,” Aquatic Toxicology, vol. 88, no. 4, pp. 207–213, Jul. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Crane, C. Watts, and T. Boucard, “Chronic aquatic environmental risks from exposure to human pharmaceuticals,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 367, no. 1, pp. 23–41, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- B. Quinn, F. Gagné, and C. Blaise, “An investigation into the acute and chronic toxicity of eleven pharmaceuticals (and their solvents) found in wastewater effluent on the cnidarian, Hydra attenuata,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 389, no. 2–3, pp. 306–314, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- F. Pomati et al., “Effects of a complex mixture of therapeutic drugs at environmental levels on human embryonic cells,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 2442–2447, Apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Grzesiuk, E. Spijkerman, S. C. Lachmann, and A. Wacker, “Environmental concentrations of pharmaceuticals directly affect phytoplankton and effects propagate through trophic interactions,” Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, vol. 156, pp. 271–278, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Legradi et al., “An ecotoxicological view on neurotoxicity assessment,” Environ Sci Eur, vol. 30, no. 1, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Sollmann, “THE EFFECTS OF A SERIES OF POISONS ON ADULT AND EMBRYONIC FUNDULI,”, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1–46, May 1906. [CrossRef]

- U. S. A Stephen A Forbes, B. E. Victor Shelford, and P. D. Errata, “An Experimental Study of the Effects of Gas Waste Upon Fishes, with Especial Reference to Stream Pollution,” Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin, vol. 11, no. 1–10, pp. 381–412, Mar. 1918. [CrossRef]

- M. Saaristo et al., “Direct and indirect effects of chemical contaminants on the behaviour, ecology and evolution of wildlife,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, vol. 285, no. 1885, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. T. Ford et al., “The Role of Behavioral Ecotoxicology in Environmental Protection,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 55, no. 9, pp. 5620–5628, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Bertram et al., “Frontiers in quantifying wildlife behavioural responses to chemical pollution,” Biological Reviews, vol. 97, no. 4, pp. 1346–1364, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Nunes et al., “Acute Effects of Tetracycline Exposure in the Freshwater Fish Gambusia holbrooki: Antioxidant Effects, Neurotoxicity and Histological Alterations,” Arch Environ Contam Toxicol, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 371–381, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Dong, J. Gao, X. Xie, and Q. Zhou, “DNA damage and biochemical toxicity of antibiotics in soil on the earthworm Eisenia fetida,” Chemosphere, vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 44–51, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Snavely and G. R. Hodges, “The neurotoxicity of antibacterial agents,” Ann Intern Med, vol. 101, no. 1, pp. 92–104, 1984. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Thomas, “Neurotoxicity of antibacterial therapy.,” South Med J, vol. 87, no. 9, pp. 869–874, Sep. 1994. [CrossRef]

- G. Nentwig, “Effects of pharmaceuticals on aquatic invertebrates. Part II: The antidepressant drug fluoxetine,” Arch Environ Contam Toxicol, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 163–170, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Fraz et al., “Paternal Exposure to Carbamazepine Impacts Zebrafish Offspring Reproduction over Multiple Generations,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 53, no. 21, pp. 12734–12743, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. W. R. E. P. B. VP Palace, “Biochemical and histopathological effects of ethynylestradiol in pearl dace (Semotilus margarita) exposed to the synthetic estrogen in a whole lake,” 2006, Accessed: May 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?hl=en&volume=25&publication_year=2006&pages=1114-1125&journal=Environ.+Toxicol.+Chem.&author=VP+Palace&title=Biochemical+and+histopathological+effects+of+ethynylestradiol+in+pearl+dace+%28Semotilus+margarita%29+exposed+to+the+synthetic+estrogen+in+a+whole+lake+experiment.

- V. P. Palace et al., “Interspecies differences in biochemical, histopathological, and population responses in four wild fish species exposed to ethynylestradiol added to a whole lake,” Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, vol. 66, no. 11, pp. 1920–1935, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Runnalls, D. N. Hala, and J. P. Sumpter, “Preliminary studies into the effects of the human pharmaceutical Clofibric acid on sperm parameters in adult Fathead minnow,” Aquatic Toxicology, vol. 84, no. 1, pp. 111–118, Aug. 2007. [CrossRef]

- W. Sanchez et al., “Adverse effects in wild fish living downstream from pharmaceutical manufacture discharges,” Environ Int, vol. 37, no. 8, pp. 1342–1348, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S. Ogawa, and I. S. Parhar, “Role of serotonin in fish reproduction,” Front Neurosci, vol. 9, no. MAY, p. 141586, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Constantine, J. W. Green, and S. Z. Schneider, “Ibuprofen: Fish Short-Term Reproduction Assay with Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Based on an Extended OECD 229 Protocol,” Environ Toxicol Chem, vol. 39, no. 8, pp. 1534–1545, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. G. A. Godoi et al., “Endocrine disruptive action of diclofenac and caffeine on Astyanax altiparanae males (Teleostei: Characiformes: Characidae),” Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology, vol. 231, p. 108720, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Liang, F. Wang, K. Li, X. Nie, and H. Fang, “Effects of norfloxacin nicotinate on the early life stage of zebrafish (Danio rerio): Developmental toxicity, oxidative stress and immunotoxicity,” Fish Shellfish Immunol, vol. 96, pp. 262–269, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. A. de Lima et al., “Diets containing purified nucleotides reduce oxidative stress, interfere with reproduction, and promote growth in Nile tilapia females,” Aquaculture, vol. 528, p. 735509, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Milla, S. Depiereux, and P. Kestemont, “The effects of estrogenic and androgenic endocrine disruptors on the immune system of fish: a review,” Ecotoxicology 2011 20:2, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 305–319, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Liang, S. Yan, R. Chen, X. Hong, and J. Zha, “3-(4-Methylbenzylidene) camphor induced reproduction toxicity and antiandrogenicity in Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes),” Chemosphere, vol. 249, p. 126224, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Kleinert, E. Lacaze, M. Mounier, S. De Guise, and M. Fournier, “Immunotoxic effects of single and combined pharmaceuticals exposure on a harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) B lymphoma cell line,” Mar Pollut Bull, vol. 118, no. 1–2, pp. 237–247, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Rehberger et al., “Long-term exposure to low 17α-ethinylestradiol (EE2) concentrations disrupts both the reproductive and the immune system of juvenile rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss,” Environ Int, vol. 142, p. 105836, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li et al., “Elucidating mechanisms of immunotoxicity by benzotriazole ultraviolet stabilizers in zebrafish (Danio rerio): Implication of the AHR-IL17/IL22 immune pathway,” Environmental Pollution, vol. 262, p. 114291, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Bera, S. Kumar, T. Paul, K. P. Prasad, S. P. Shukla, and K. Kumar, “Triclosan induces immunosuppression and reduces survivability of striped catfish Pangasianodon hypophthalmus during the challenge to a fish pathogenic bacterium Edwardsiella tarda,” Environ Res, vol. 186, p. 109575, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Khan et al., “Impact, disease outbreak and the eco-hazards associated with pharmaceutical residues: a Critical review,” International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 677–688, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zenker, M. R. Cicero, F. Prestinaci, P. Bottoni, and M. Carere, “Bioaccumulation and biomagnification potential of pharmaceuticals with a focus to the aquatic environment,” J Environ Manage, vol. 133, pp. 378–387, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Mallik, K. A. M. Xavier, B. C. Naidu, and B. B. Nayak, “Ecotoxicological and physiological risks of microplastics on fish and their possible mitigation measures,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 779, p. 146433, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. M. M. Hasan, M. Hamed, J. Hasan, C. J. Martyniuk, S. Niyogi, and D. P. Chivers, “A review of the neurobehavioural, physiological, and reproductive toxicity of microplastics in fishes,” Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, vol. 282, p. 116712, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- I. Patra et al., “Toxic effects on enzymatic activity, gene expression and histopathological biomarkers in organisms exposed to microplastics and nanoplastics: a review,” Environmental Sciences Europe 2022 34:1, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Rashid, S. M. Hussain, S. Ali, P. K. Sarker, and M. A. Farah, “Investigating the toxicity of polylactic acid microplastics on the health and physiology of freshwater fish, Cirrhinus mrigala,” Ecotoxicology, vol. 33, no. 10, pp. 1210–1221, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ronald Smith MD, “The Impacts of Microplastics on Health,” Protect Henderson Inlet.

- X. Zheng et al., “Growth inhibition, toxin production and oxidative stress caused by three microplastics in Microcystis aeruginosa,” Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, vol. 208, p. 111575, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Kidd et al., “Direct and indirect responses of a freshwater food web to a potent synthetic oestrogen,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 369, no. 1656, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. P. Wright, L. Zhang, I. Cheng, J. Aherne, and G. R. Wentworth, “Impacts and Effects Indicators of Atmospheric Deposition of Major Pollutants to Various Ecosystems - A Review,” Aerosol Air Qual Res, vol. 18, no. 8, pp. 1953–1992, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Bradley et al., “Pilot-scale expanded assessment of inorganic and organic tapwater exposures and predicted effects in Puerto Rico, USA,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 788, p. 147721, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Fahrig and G. Merriam, “Conservation of Fragmented PopulationsConservación de poblaciones fragmentadas,” Conservation Biology, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 50–59, Mar. 1994. [CrossRef]

- R. Smith and D. T. Blumstein, “Fitness consequences of personality: a meta-analysis,” Behavioral Ecology, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 448–455, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Brooks and S. I. Dodson, “Predation, body size, and composition of plankton,” Science (1979), vol. 150, no. 3692, pp. 28–35, Oct. 1965. [CrossRef]

- Balvanera et al., “Quantifying the evidence for biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning and services,” Ecol Lett, vol. 9, no. 10, pp. 1146–1156, Oct. 2006. [CrossRef]

- “Pharmaceutical Residues in Freshwater Hazards and Policy Responses Pharmaceutical Residues in Freshwater Hazards and Policy Responses Contents.”.

- A. Ballinger and P. S. Lake, “Energy and nutrient fluxes from rivers and streams into terrestrial food webs,” Mar Freshw Res, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 15–28, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- C. Gross, J. L. Ruesink, C. Pruitt, A. C. Trimble, and C. Donoghue, “Temporal variation in intertidal habitat use by nekton at seasonal and diel scales,” J Exp Mar Biol Ecol, vol. 516, pp. 25–34, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Liu et al., “Changes in fish assemblages following the implementation of a complete fishing closure in the Chishui River,” Fish Res, vol. 243, p. 106099, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Arnold, A. R. Brown, A. R. Brown, G. T. Ankley, and J. P. Sumpter, “Medicating the environment: Assessing risks of pharmaceuticals to wildlife and ecosystems,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 369, no. 1656, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. G. Bean, A. B. A. Boxall, J. Lane, K. A. Herborn, S. Pietravalle, and K. E. Arnold, “Behavioural and physiological responses of birds to environmentally relevant concentrations of an antidepressant,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 369, no. 1656, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Kidd et al., “Direct and indirect responses of a freshwater food web to a potent synthetic oestrogen,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 369, no. 1656, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. N. O. Ajima and P. K. Pandey, “Effects of Pharmaceutical Waste in Aquatic Life,” Advances in Fisheries Biotechnology, pp. 441–452, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, J. Ge, and X. Yu, “Bioavailability and toxicity of microplastics to fish species: A review,” Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, vol. 189, no. March 2019, p. 109913, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. R. Hossain and J. D. Olden, “Global meta-analysis reveals diverse effects of microplastics on freshwater and marine fishes,” Fish and Fisheries, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 1439–1454, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Lusher, Microplastics in fisheries and aquaculture. Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper 61. 2017.

- N. Khalid et al., “Linking effects of microplastics to ecological impacts in marine environments,” Chemosphere, vol. 264, p. 128541, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. M. M. Hasan, M. Hamed, J. Hasan, C. J. Martyniuk, S. Niyogi, and D. P. Chivers, “A review of the neurobehavioural, physiological, and reproductive toxicity of microplastics in fishes,” Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, vol. 282, no. July, p. 116712, 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Dong, X. Liu, Q. Hou, and Z. Wang, “From natural environment to animal tissues: A review of microplastics(nanoplastics) translocation and hazards studies,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 855, no. August 2022, p. 158686, 2023. [CrossRef]

- “World Health Organization (WHO).” Accessed: Feb. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/.

- M. Smith, D. C. Love, C. M. Rochman, and R. A. Neff, “Microplastics in Seafood and the Implications for Human Health,” Curr Environ Health Rep, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 375, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Leslie, M. J. M. van Velzen, S. H. Brandsma, A. D. Vethaak, J. J. Garcia-Vallejo, and M. H. Lamoree, “Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood,” Environ Int, vol. 163, May 2022. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).