1. Introduction

Coffee accounts for 75% of regular soft drinks consumption and is the most commonly consumed beverage in the world [

1]. Knowing the impact of coffee on human health is of keen interest. The excessive consumption of this beverage has been aggravating the risks associated with anxiety, depression, pregnancy-related problems and heart disease [

2].

Recently, the phytochemistry and biological properties of coffee over the negative effects were considered an excellent functional food as it has proven human health benefits[

3]. Specific molecules encompassed in coffee beverages are evidenced both in the epidemiological and experimental studies regarding the valuable effects against neurological diseases, metabolic disorders (type 2 diabetes), and psychoactive responses (alertness, mood change). However, in recent years, this has led to an increase in the consumption of green–coffee-based beverages[

4].

Globally, more than 80 different coffee species have been identified[

5]. But only two are economically important are Robusta coffee and Coffea arabica, the latter is popularly called Arabica coffee, which constitutes approximately 70% of the global coffee market. Coffee occupies a great place in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, as it is considered a symbol of generosity and hospitality, in addition to being a regular daily drink. The Kingdom is one of the largest countries in the world consuming coffee and second in the Arab world after Algeria. The consumption of coffee in the last three years is estimated at more than 170 thousand tons, with a value exceeding 2. 25 billion Saudi riyals, mainly imported from Ethiopia, which accounts for 72% of the total imports of coffee in Saudi Arabia[

6].

In humans, the optimal concentration of fluoride is beneficial; however, an excess of this ion can produce numerous adverse effects on humans health[

7,

8]. Daily, we consume various beverages like coffee, tea, and carbonated drinks, but water is the main source of fluoride. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) reported that more than 0.3 mg/L of fluoride is consumed through the intake of water and beverages prepared with it [

9,

10]. Additionally, studies by Wolska et al. [

11]. found an average concentration of 0.50 mg/L in Turkish coffee and less than 0.20 mg/L in espresso, both contain significant concentrations of fluoride. Continuous exposure to high fluoride concentrations leads to harmful health effects, dental fluorosis and later skeletal fluorosis[

12,

13]. Additionally, fluoride contributes to enhancing the hardness of tooth enamel and decreasing the frequency of dental issues caries[

14]. The arabic coffee has been the most widely consumed cultural beverage, to date, there is a lack of literature on the fluoride concentration in Arabic coffee. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the fluoride intake from consuming Arabic coffee beverages in various regions of Saudi Arabia. The aims of this study were

(1) to assess the fluoride concentration in Arabic coffee from different regions. and (2) to assess the dietary fluoride exposure by the Arabic coffee intake.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

A study proposal was submitted to the Standing Committee of Bioethics Research, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia, and ethical approval was obtained (SCBR-187/2023) before conducting the study.

Sample Selection.

The method of sampling Arabic coffee in this cross-sectional study was determined by the regions and preparation methods in Saudi Arabia. The regions were grouped into 5 based on their geographical locations: central, eastern, northern, western, and southern. 8samples were considered from each category for testing, and a total of 40 samples were considered. The sample size was determined using the G*power software.

Method of Arabic Coffee Preparation

The method of preparing Arabic coffee and its ingredients are described in the table given below.

| Region |

Contents |

Preparation of Saudi coffee |

| Central |

800ml of water(1ppm),40gram of medium roastedbeans,30gram of cardamom,0. 5 gram of Cloves and 0. 5gram of Saffron. |

1-Boil the water

2-Add the grounded coffee beans

3- brew it with medium heat for 17 minutes

4-Add the cardamom,cloves and saffron continue the brew for 2-3 more minutes.

5-Remove the coffee and let it rest for 2 minutes |

| Northern |

800ml of water(1ppm),40gram of dark roasted beans,30gram of cardamom. |

1-Boil the water

2-Add the grounded coffee beans

3- Brew it with medium heat for 20-30 minutes

4-Add the cardamom for 2-3 more minutes

5-Remove the coffee and let it rest for 2 minutes |

| Eastern |

800ml of water(1ppm),

40gram of medium roasted beans

30gram of cardamom and

0. 5gram of Saffron. |

1-Boil the water

2-Add the grounded coffee beans and Saffron

3- Brew it with medium heat for 17 minutes

4-Add the cardamom for 2-3 more minutes

5-Remove the coffee and let it rest for 2 minutes |

| Western |

800ml of water(1ppm),

40gram of medium roasted beans,

30gram of cardamom,

0. 5gram of Saffron and 1 gram of mastic gum. |

1-Boil the water

2-Add the grounded coffee beans

3-Add all the ingredients except the cardamom

4- Brew it with medium heat for 15 minutes

5-Add the cardamom for 5 more minutes

6-Remove the coffee and let it rest for 2 minutes |

| Southern |

800ml of water(1ppm),

40gram of light roasted beans,

30gram of cardamom,

0. 5gram of Saffron, 1 gram of Ginger,1gram of cinnamon,1 gram of fennel seeds and

1gram of Cloves. |

1-Boil the water

2-Add the grounded coffee beans

3-Add all the ingredients except the cardamom

4- Brew it with medium heat for 15 minutes

5-Add the cardamom for 5 more minutes

6-Remove the coffee and let it rest for 2 minutes |

The fluoride content of the water used for the coffee preparation was set at 1ppm, and the variant will be ingredients and the brew time. The brewed coffee was stored in the thermos(Dallah). Before the collection of coffee, the container was rinsed three times with distilled water to minimize the error, and then 300 mL of coffee sample was collected. After calibration, each sample will be examined using an ion chromatography system (ExStik® FL700 Fluoride Meter, USA) and according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Calibration of Fluoride Meter

Calibration of the fluoride meter was done before measuring the fluoride in different coffee solutions for the accuracy of measurement. This FL700 can be calibrated at four different calibrating points: 0.5,1, 5, or 10PPM fluoride ions. To calibrate the 1PPM, one TISAB (Total Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer)tablet was added to the sample cup in 20ml of 1PPM. Recalibration is required once the region of the sample is changed. The specification of the FL700 is a range of measurement of PPM(0.1 TO 10 PPM )operating temperature(0 to 60 degrees Celsius) accuracy (+/- 0.1PPM). The electrode used was Europium Europium-doped lanthanum fluoride single crystal, and the response time was less than 30 seconds. The measurement method is a potentiometric ion selective electrode.

To maintain consistency in measurements, the system will be configured with various recognition limits: two ppm, one ppm, 0.5 ppm, and the minimum detection limit of 0.01 ppm. Readings will be documented if fluoride is detected in the sample at the chosen limit. Multiple readings will also be taken at each detection limit.

Measuring the Fluoride Level in Coffee

Eight samples of each region were tested for measurement of fluoride in the Arabic coffee. A 25ml of prepared and homogenized coffee solution was taken in a container ( sample cup ) provided by the manufacturer. A total of 40 coffee samples were gathered and analyzed using an ion chromatography system (ExStik ® FL700 Fluoride Meter, USA). Following calibration, each sample underwent examination, testing, and retesting. The resulting average values were documented and organized into tables. To maintain consistency in measurements, multiple readings were conducted at the same detection limit across all samples. Additionally, all samples were assessed for the coffee temperature deemed suitable for consumption.

Dietary Intake Assessment

Using equations 1 and 2 the estimated daily intake (EDI)and risk assessment were determined concerning the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)7 mg of fluoride was considered as the upper limit[

10].

-

(1)

EDI = Fluoride concentration ( mg/L ) × Daily consumption ( L/day )

-

(2)

-

Risk Assessment = EDI ( mg/day ) × 100

Statistical Analysis:

In this study, we conducted both descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. Continuous measurement results are presented as Mean ± SD. A significance level of p=0.05 was established, and any values equal to or below 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) assessed the significance of study parameters across groups (intergroup analysis). If ANOVA results were significant, subsequent post hoc analyses were performed. We calculated Pearson’s Correlation coefficient to evaluate the relationship between fluoride PPM in various regions and the temperature of Arabic coffee. The data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), while Microsoft Word and Excel were utilized for creating graphs, tables, and other visualizations.

2. Results

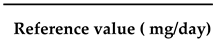

The evaluation and comparison of the fluoride concentration of Arabic Coffee in different regions of Saudi Arabia revealed a significant difference (p-value - 0.001) as shown in (

Table 2 and

Table 3) (

Figure 1). A comparative evaluation between different regions revealed no significant difference between central and Western, Central and Southern, Eastern and Northern, and between western and southern regions with respect to the fluoride concentration of Arabic Coffee (

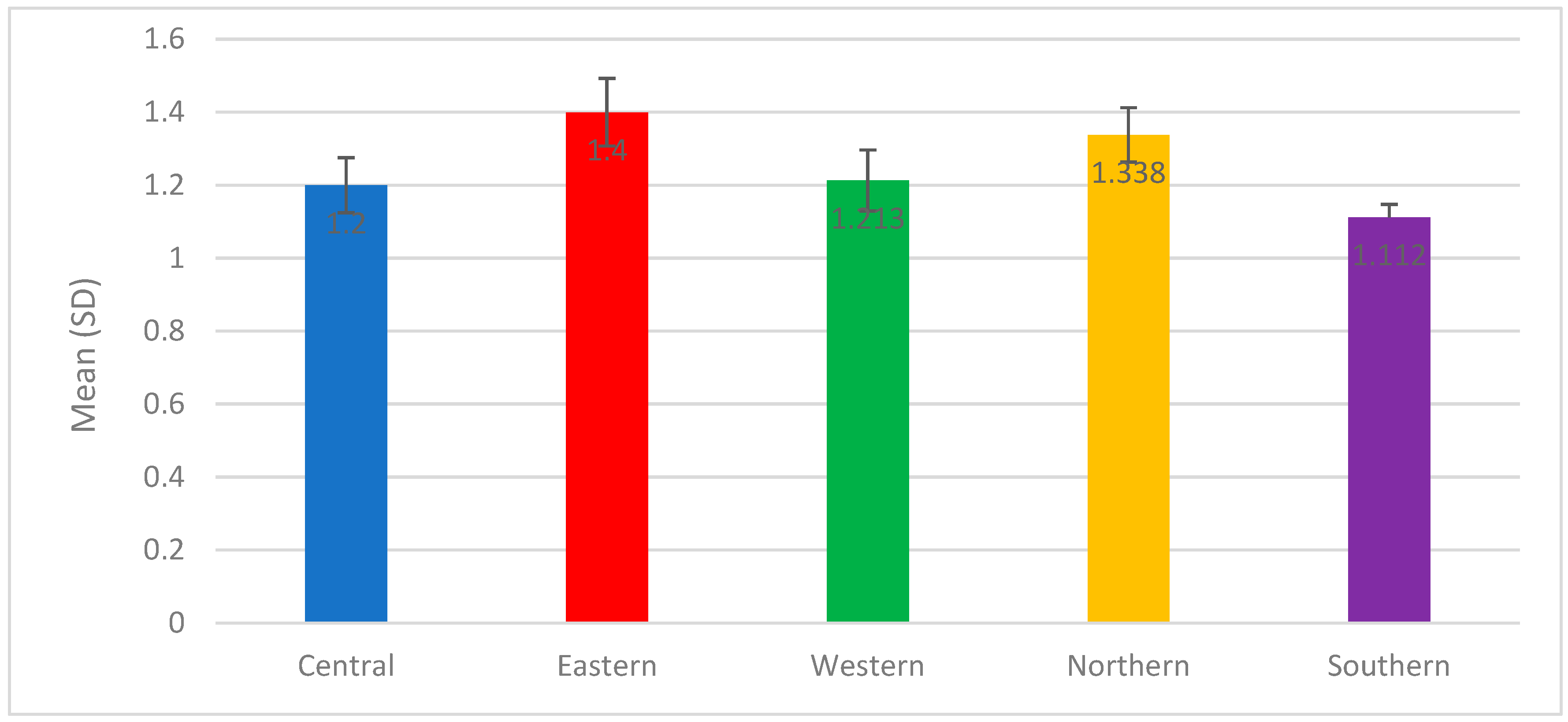

Table 2). The significant difference(0.031) between western and southern region showed when comparing the coffee temperature (

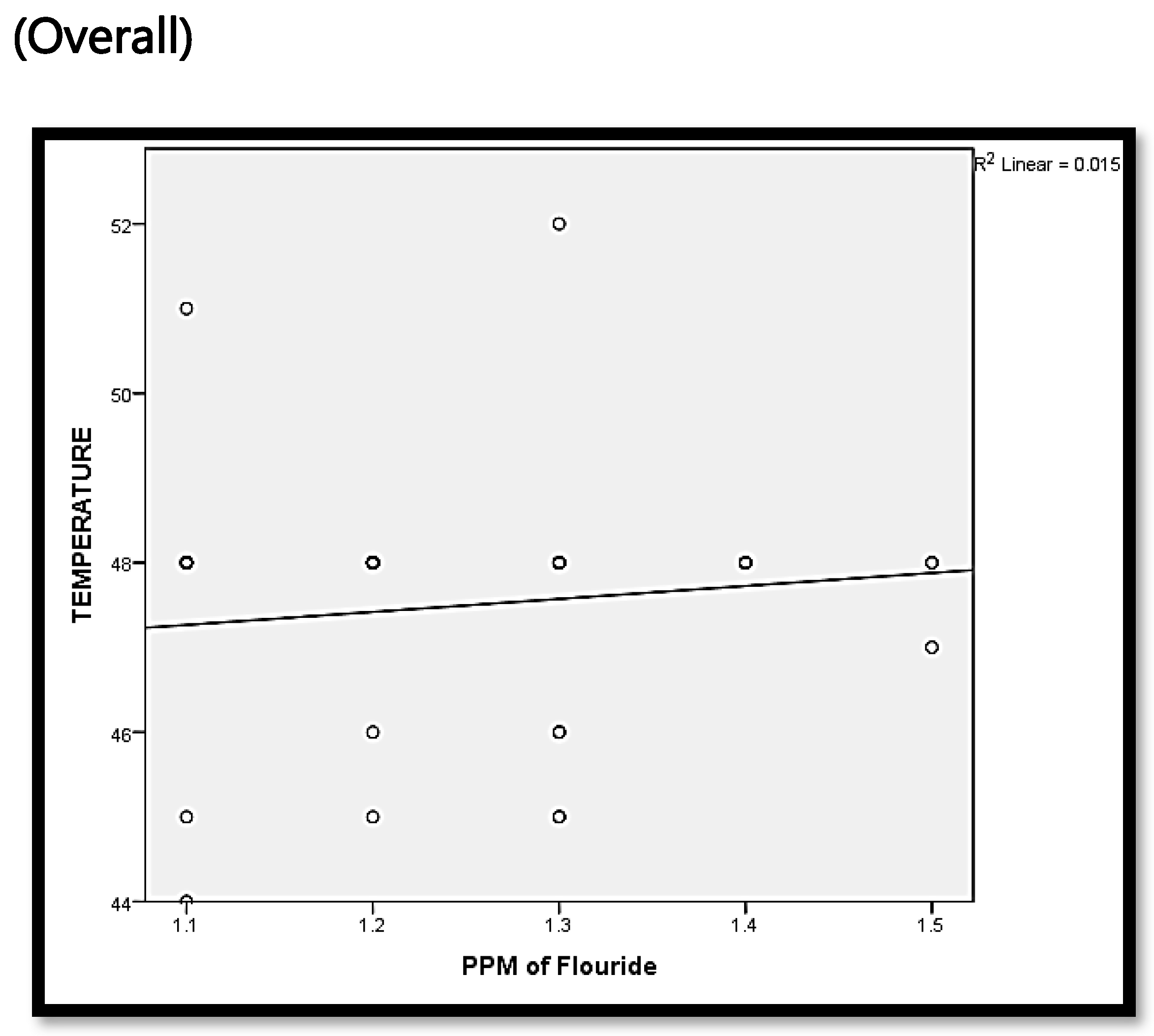

Table 4). No significant correlation (p value 0.449) between fluoride concentration with the temperature of Arabic coffee was reported in this study (

Table 5). Mean concentrations, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values of the fluoride and temperature in the Arabic coffee from different regions were presented (

Table 3 and

Table 6 Figure 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of PPM of Fluoride in terms of {Mean (SD)} among different regions using ANOVA test.

Table 2.

Comparison of PPM of Fluoride in terms of {Mean (SD)} among different regions using ANOVA test.

| Group |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

F value |

P value |

| Central |

8 |

1.200 |

0.0756 |

18. 882 |

<0.001** |

| Eastern |

8 |

1.400 |

0.0926 |

| Western |

8 |

1.213 |

0.0835 |

| Northern |

8 |

1.338 |

0.0744 |

| Southern |

8 |

1.112 |

0.0354 |

| Total |

40 |

1.253 |

0.1261 |

Table 3.

Post Hoc Analysis.

Table 3.

Post Hoc Analysis.

| Group |

In comparison with |

P value |

| Central |

Eastern |

<0.001** |

| Western |

0.997 |

| Northern |

0.007* |

| Southern |

0.157 |

| Eastern |

Western |

<0.001** |

| Northern |

0.465 |

| Southern |

<0.001** |

| Western |

Northern |

0.016* |

| Southern |

0.079 |

| Northern |

Southern |

<0.001** |

Table 4.

Comparison of Coffee Temperature in terms of {Mean (SD)} among different regions using ANOVA test.

Table 4.

Comparison of Coffee Temperature in terms of {Mean (SD)} among different regions using ANOVA test.

| Group |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

F value |

P value |

| Central |

8 |

47. 50 |

0.926 |

2. 450 |

0.064 |

| Eastern |

8 |

47. 50 |

1.069 |

| Western |

8 |

48. 50 |

2. 138 |

| Northern |

8 |

47. 75 |

0.707 |

| Southern |

8 |

46. 25 |

1.909 |

| Total |

40 |

47. 50 |

1.569 |

Table 5.

A comparative evaluation of Coffee Temperature between different regions.

Table 5.

A comparative evaluation of Coffee Temperature between different regions.

| Group |

In comparison with |

P value |

| Central |

Eastern |

1.000 |

| Western |

0.653 |

| Northern |

0.997 |

| Southern |

0.442 |

| Eastern |

Western |

0.653 |

| Northern |

0.997 |

| Southern |

0.442 |

| Western |

Northern |

0.842 |

| Southern |

0.031* |

| Northern |

Southern |

0.265 |

Table 6.

Correlation between PPM of fluoride in different regions and the temperature of coffee using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. .

Table 6.

Correlation between PPM of fluoride in different regions and the temperature of coffee using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. .

| PPM of fluoride of different regions |

No of samples |

Temperature of the coffee |

| R (correlation coefficient) |

P value |

| Overall |

40 |

0.123 |

0.449 |

| Central |

8 |

-0.408 |

0.315 |

| Eastern |

8 |

0.289 |

0.488 |

| Western |

8 |

-0.200 |

0.635 |

| Northern |

8 |

0.204 |

0.629 |

| Southern |

8 |

-0.265 |

0.526 |

Table 7.

Mean concentrations, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values of fluoride in the coffee from different regions.

Table 7.

Mean concentrations, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values of fluoride in the coffee from different regions.

| Region |

Central |

Eastern |

Western |

Northern |

Southern |

| Mean concentrations |

1.200 |

1.400 |

1.213 |

1.338 |

1.112 |

| Min. Value |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

| Max. Value |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.0756 |

0.0926 |

0.0835 |

0.0744 |

0.0354 |

Figure 1.

Comparison of PPM of Fluoride in terms of {Mean (SD)} among different regions using ANOVA test.

Figure 1.

Comparison of PPM of Fluoride in terms of {Mean (SD)} among different regions using ANOVA test.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Temperature in terms of {Mean (SD)} among different regions using ANOVA test.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Temperature in terms of {Mean (SD)} among different regions using ANOVA test.

Figure 3.

Correlation between PPM of fluoride in different regions and temperature using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Figure 3.

Correlation between PPM of fluoride in different regions and temperature using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

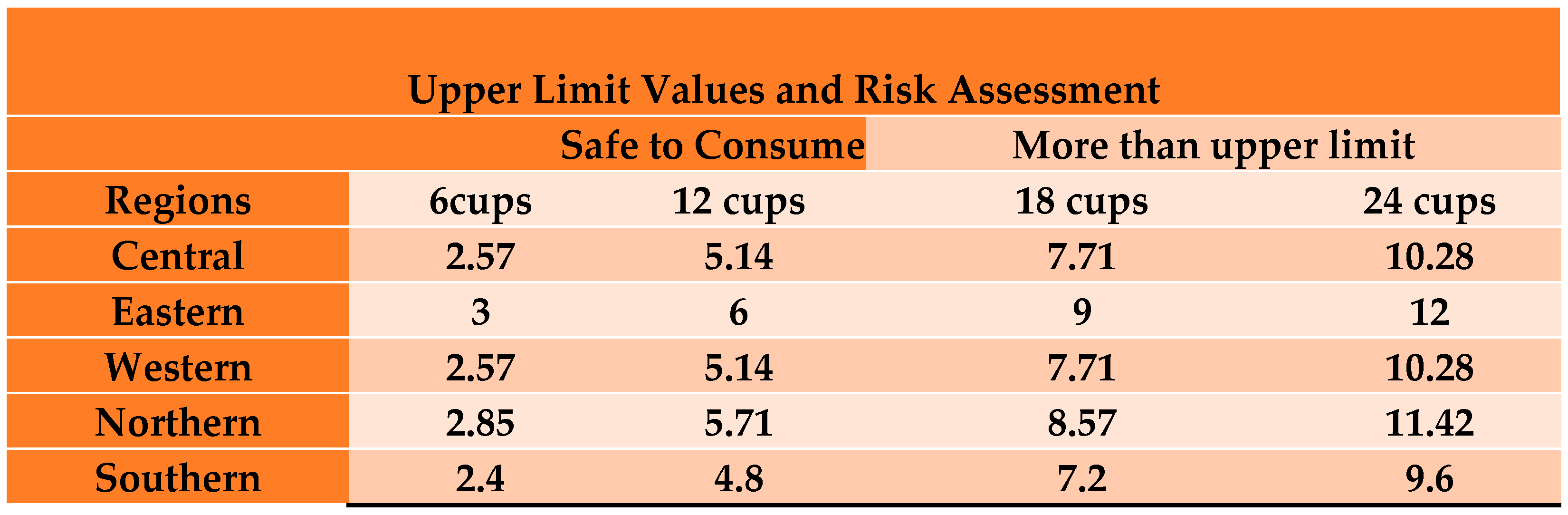

Figure 7.

The upper limit and assessment of risk by the Arabic coffee consumption. According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Upper Limit Is 7mg.

Figure 7.

The upper limit and assessment of risk by the Arabic coffee consumption. According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Upper Limit Is 7mg.

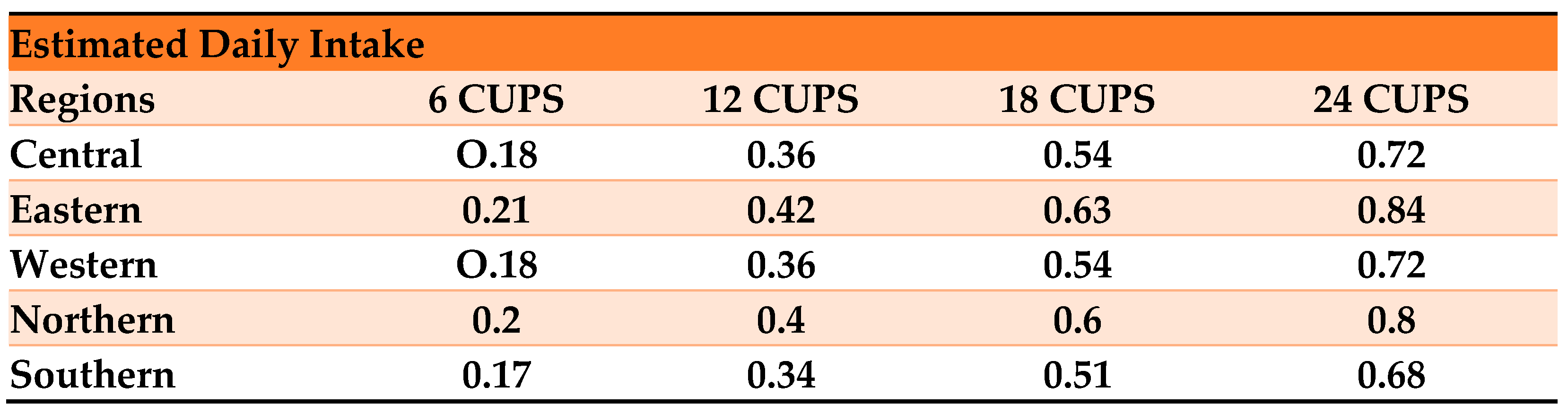

Figure 8.

Depicts the estimated daily intake of fluoride by consuming Arabic coffee.

Figure 8.

Depicts the estimated daily intake of fluoride by consuming Arabic coffee.

Figure 9.

Shows the PPM of fluoride concentration in Arabic coffee.

Figure 9.

Shows the PPM of fluoride concentration in Arabic coffee.

3. Discussion

The rich history of Arabic coffee consumption is growing continuously in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia(KSA). Arabic coffee is considered a welcoming beverage in the KSA that is served all day long. In 2015, UNESCO(United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization) recognized the significance and art of making the traditional method of coffee in Saudi Arabia’s culture. The Arabs used to say that the first cup of coffee is for the head, the second one is for the strength, and the third is for the mind to remove headaches.

Arabic Qahwa (AQ) is a staple food and traditional beverage not only in Saudi Arabia but in all Middle Eastern countries. Arabic coffee is prepared by adding different ingredients like cardamom, cloves, ginger, cinnamon, gum, and many more, according to their culture. The average volume of each cup is about 25 ml and the mean consumption of 6 cups of Arabia coffee by a normal individual. Many studies evidenced very high caffeine content in Turkish coffee, as much as 2 Nescafe®, and that weighs to 20 cups of Arabian coffee. [

15,

16]. Even the roasting process of coffee beans at different temperatures revealed the caffeine content ranges between 19–21 mg/g in Robusta beans and 10 and 12 mg/g in Arabica beans[

17,

18].

The shift towards bottled water consumption in Saudi Arabia, driven by concerns about natural water supplies' contamination, has implications for fluoride intake. Variations in fluoride concentration among bottled waters underscore the importance of accurate labeling and further research into optimal fluoride levels for dental health. [

19].

The presence of fluoride in the dentifrice’s mouthwashes may prevent the caries process[

20]. In the previous literature, the relationship between the fluoride and prevention of caries has been studied extensively[

21,

22]. The reduction in the incidence of early childhood caries is greatly affected by the regular use of fluoride-based interventions[

23]. The Fluoride ion reacts with the hydroxyl crystal present in the tooth enamel and forms into fluorapatite, which is more resistant against dental caries[

24]. This converted fluorapatite crystal is much stronger against acid attacks and enamel’s surface solubility [

25].

The study results revealed the mean fluoride concentration of the overall region was optimal. The lowest fluoride concentration in Arabic coffee was found in the southern region; this may be due to the type of ingredients used in the coffee. Furthermore, decaffeinated coffee contains the lowest fluoride concentration, likely due to the method used to reduce its caffeine content, which may also remove some fluoride in the process contains[

26].

Some evidence revealed that in roasted Arabic coffee, the fluoride content is less than the green coffee Olechno et al[

27]. The fluoride concentration in the ready-to-drink coffee was high compared to roasted Arabic coffee Satou et. al[

28]. Wolski et al. evidenced that the preparation and type of coffee beans affect the fluoride concentration in the coffee[

11].

The variations of fluoride concentration in Arabic coffee were multifactorial. The factors may be the absorption of fluoride by coffee plants, the fluoride content of the soil, water used for the cultivation, germination process, and fluoride content of the ingredients used for the coffee preparation [

7,

26]. The addition of various additives, such as evaporated milk or Coffee-mate, can significantly alter the caloric content of Arabic coffee. Evaporated milk, a prevalent additive in Arabic coffee, is also commonly used in Malaysian coffee culture [

29,

30]. Considering the popularity of these additives, it's crucial to recognize their impact on the overall caloric intake associated with Arabic coffee consumption. Arabic coffee without any additives inherently contains minimal to no calories[

16].

The contrasting findings regarding the health effects of Arabic coffee consumption, accompanied by additives and or sweets, had an increased risk of obesity [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. On the other hand, the study suggesting that Arabian coffee consumption, specifically Saudi coffee, may have positive effects on the body mass index (BMI), blood glucose levels, and blood pressure, offers an intriguing perspective. This indicates that moderate consumption of Arabic coffee, without excessive additives, may have potential benefits for metabolic health, including the management of early stages of hypertension[

40,

41]. Some researchers have identified that the nutritional benefits of date fruit suggest potential synergies with Arabic coffee consumption for individuals managing diabetes mellitus. [

42].

The recent data on coffee consumption of the Spanish population was 1.94kg/person/year, which is comparatively high43. Moreover, the overall latest report of coffee consumption in the Saudia population is markedly high, 6. 22kg/person in 2021but the Saudi coffee consumption data is not available. Finally, the results of our study revealed that 12 cups of Saudi coffee per day is safe to consume. However, the upper limit was reached by consuming more than 18 cups /day, which can impact the daily intake of fluoride in the diet. Nonetheless, most of the residents consume bottled water with a fluoride concentration of around 1PPM. Therefore, we used water of 1ppm fluoride in all the regions.

A need for further research on the preparation with different ppm of fluoride water. One of the limitations of our research was the small sample size, and different ingredients were used to prepare the Arabic coffee.

The positive and negative health effects of Arabic coffee consumption should be made through health fairs and cultural gatherings like conferences and national health programs to the younger generations to correct the wrong perceptions. Finally, the deeply ingrained traditions of serving Arabic coffee reflect centuries of cultural heritage and ancestral wisdom. Adherence to these traditions not only connects us to our past but also enriches the experience of enjoying Arabic coffee, making it as enjoyable as its origins. By preserving and honoring these traditions, we can continue to celebrate the cultural significance of Arabic coffee for generations to come.

5. Conclusions

The fluoride concentrations of Arabic coffee in 5 different regions were determined using ion-selective potentiometric technique. The overall mean concentration of fluoride was optimal (1.253PPM), but the highest content was recorded in the eastern (1.400PPM), and the lowest was found in the southern group (1.112PPM). A statistically significant difference was found in the fluoride content, but the comparative evaluation revealed no significance. Additionally, the temperature and the fluoride content did not reveal the correlation. The difference in the fluoride concentration of Arabic coffee among different regions was minimal this may be due to the number of ingredients used in the preparation.

Nonetheless, the generous amount(12 cups) of Arabic coffee consumption may not cause either acute or chronic fluoride toxicity. It is essential to evaluate the total fluoride intake, particularly if consumers are subjected to elevated fluoride levels in the water supply.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and R.B.S.; methodology, A.A. and R.B.S.; software, A.A. and R.B.S; validation, A.A. and R.B.S; formal analysis, A.A., R.B.S, and B.A.; investigation, O.A., A.Z., and R.B.S.; resources, A.A, O.A., A.Z., and R.B.S.; data curation, A.A., R.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A, R.B.S., A.A., A.Q., A.G., S.G.,S.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and R.S.; visualization, A.A. and R.S.; supervision, A.A. and R.S.; project administration, A.A. and R.B.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1446).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (protocol code SCBR-187/2023 and 08/11/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon suitable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding the study via project number (PSAU/2025/R/1446).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Toci, A. T.; Farah, A.; Pezza, H. R.; Pezza, L. Coffee Adulteration: More than Two Decades of Research. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry, 2016, 46, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot, P.; Jordan, S.; Eastwood, J.; Rotstein, J.; Hugenholtz, A.; Feeley, M. Effects of caffeine on human health. Food Additives & Contaminants, 2003, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, G.; Zannella, C.; Monda, V.; Dato, A.; Liccardo, D.; De Blasio, S.; Valenzano, A.; Moscatelli, F.; Messina, A.; Cibelli, G. The beneficial effects of coffee in human nutrition. Biology and Medicine, 2015, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, I. A.; Clifford, M. N.; Lean, M. E. J.; Ashihara, H.; Crozier, A. Coffee:biochemistry and potential impact on health. Food & Function, 2014, 5, 1695–1717. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, R. J. Coffee: green coffee/roast and ground, Encyclopedia of Food Science and Nutrition, 2nd ed.; Caballero, B., Trugo, L. C., Finglas, P., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- General Authority for Statistics (2018): Annual report. Saudi Arabia. https://www. stats. gov. sa.

- Rodríguez, I.; Jaudenes, J. R.; Hardisson, A.; Paz, S.; Rubio, C.; Gutiérrez, A. J.; Burgos, A.; Revert, C. Potentiometric determination of fluoride concentration in beers. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 181, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akuno, M. H.; Nocella, G.; Milia, E. P.; Gutierrez, L. Factors influencing the relationship between fluoride in drinking water and dental fluorosis: A ten-year systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Water Health 2019, 17, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fluoride. EFSA J. Panel Diet. Prod. Nutr. Allerg. 2013, 11, 3332. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Tolerable Upper Intake Levels for Vitamins and Minerals; European Food Safety Authority: Parma, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wolska, J.; Janda, K.; Jakubczyk, K.; Szymkowiak, M.; Chlubek, D.; Gutowska, I. Levels of Antioxidant Activity and Fluoride Content in Coffee Infusions of Arabica, Robusta and Green Coffee Beans in According to their Brewing Methods. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017, 179, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaudenes Marrero, J. R.; Hardisson de la Torre, A.; Gutiérrez Fernández, Á. J.; Rubio Armendáriz, C.; Revert Gironés, C. Evaluación del riesgo tóxico por la presencia de fluoruro en aguas de bebida envasada consumidas en Canarias. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 2261–2268. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, C. M. Focus on fluorides: Update on the use of fluoride for the prevention of dental caries. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2014, 14, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storsberg, J.; Loza, K.; Epple, M. Incorporation of Fluoride into Human Teeth after Immersion in Fluoride-Containing Solutions Dent. J. 2022, 10, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Rezk, N. L.; Ahmed, S.; Iqbal, M.; Rezk, O. A.; Ahmed, A. M. Comparative evaluation of caffeine content in Arabian coffee with other caffeine beverages. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Naser, L. R.; Sameh, A.; Muzaffar, I.; Omar, A. R.; Ahmed, M. A. Comparative evaluation of caffeine content in Arabian coffee with other caffeine beverages. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 12, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G. P.; Wu, A.; Yiran, L.; Force, L. Variation in caffeine concentration in single coffee beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 10772–10778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, S.; Beatriz Oliveira, M.; Ferreira, M. A. HPLC/diode-array applied to the thermal degradation of trigonelline, nicotinic acid and caffeine in coffee. Food Chem. 2000, 68, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrees, A.M.; Al-Manea, S.M. Fluoride content of bottled drinking waters available in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2010, 22, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, R.; Zafar, M. S. Oral and dental delivery of fluoride: a review. Fluoride 2015, 48, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Somaraj, V.; Shenoy, R. P.; Shenoy Panchmal, G.; Kumar, V.; Jodalli, P. S.; Sonde, L. Effect of herbal and fluoride mouth rinses on streptococcus mutans and dental caries among 12–15-year-old school children: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Dent. 2017, 5654373. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. B.; Slayton, R. L. Fluoride use in caries prevention in the primary care setting. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammari, J. B.; Baqain, Z. H.; Ashley, P. F. Effects of programs for prevention of early childhood caries. A systematic review. Med. Princ. Pract. 2007, 16, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N. R.; Lynch, R. J.; Anderson, P. Effects of fluoride concentration on enamel demineralization kinetics in vitro. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Neel, E. A.; Aljabo, A.; Strange, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Coathup, M.; Young, A. M.; Bozec, L.; Mudera, V. Demineralization- remineralization dynamics in teeth and bone. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 19, 4743–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alejandro-Vega, S.; Suárez-Marichal, D.; Niebla-Canelo, D.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, Á. J.; Rubio-Armendáriz, C.; Hardisson, A.; Paz-Montelongo, S. Fluoride Exposure from Ready-To-Drink Coffee Consumption. Life 2022, 12, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olechno, E.; Pu´scion-Jakubik, A.; Socha, K.; Zujko, M. E. Coffee Infusions: Can They Be a Source of Microelements with Antioxidant Properties? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satou, R.; Oka, S.; Sugihara, N. Risk assessment of fluoride daily intake from preference beverage. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, D.R.; Ross, R.; Janssen, I. Coffee, tea and their additives: Association with BMI and waist circumference. Obesity Facts 2010, 3, 345–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, E.Y.; Zalilah, M.S.; Ys Chin, Y.S.; Norhasmah, S. Dietary diversity is associated with nutritional status of Orang Asli children in Krau Wildlife Reserve, Pahang. Malaysian Journal of Nutrition 2012, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rola A Jalloun1*, Monebah H Alhathlool2* Arabic coffee consumption and the risk of obesity among Saudi's female population Journal of the Saudi Society for Food and Nutrition (JSSFN) 2020, 13, 59-67.

- Jalloun, R. A.; Alhathlool, M. H. Arabic coffee consumption and the risk of obesity among Saudi’s female population. J. Saud. Soc. Food Nutr. 2020, 13, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hino, A.; Adachi, H.; Enomoto, M.; Furuki, K.; Shigetoh, Y.; Ohtsuka, M.; Kumagae, S.; Hirai, Y.; Jalaldin, A.; Satoh, A.; et al. Habitual coffee but not green tea consumption is inversely associated with metabolic syndrome: An epidemiological study in a general Japanese population. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007, 76, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomilehto, J.; Hu, G.; Bidel, S.; Lindström, J.; Jousilahti, P. Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus among middle-aged Finnish men and women. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2004, 291, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; Marventano, S.; Galvano, F.; Pajak, A.; Mistretta, A. Factors associated with metabolic syndrome in a mediterranean population: Role of caffeinated beverages. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alawadh, R. A.; Abid, N.; Alsaad, A. S.; Aljohar, H. I.; Alharbi, M. M.; Alhussain, F. K. Arabic Coffee consumption, and its correlation to obesity among the general population in the eastern province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e30848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H. Y.; Kim, J. Coffee consumption, and the risk of obesity in Korean Women. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaabi, J.; Al-Dabbagh, B.; Saadi, H.; Gariballa, S.; Yasin, J. Effect of traditional Arabic coffee consumption on the glycemic index of Khalas dates tested in healthy and diabetic subjects. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 22, 565–573. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mssallem, M. Q.; Brown, J. E. Arabic coffee increases the glycemic index but not insulinemic index of dates. Saudi Med. J. 2013, 34, 923–928. [Google Scholar]

- Jalal, S. M.; Alsebeiy, S. H.; Aleid, H. A.; Alhamad, S. A. Effect of Arabic Qahwa on Blood Pressure in Patients with Stage One Hypertension in the Eastern Region of Saudi Arabia. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezq, A. A.; Qadhi, A. H.; Almasmoum, A.; Ghafouri, K. J. Effect of Arabian coffee (saudi coffee) consumption on body mass index, blood glucose level and blood pressure in some people of Makkah Region, KSA. Kasmera J. 2020, 48, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mirghani, H. O. Dates fruits effects on blood glucose among patients with diabetes mellitus: A review and meta-analysis. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 37, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar]

- MAPA. Informe del Consumo de Alimentación en España 2018; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 477–485. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).