Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

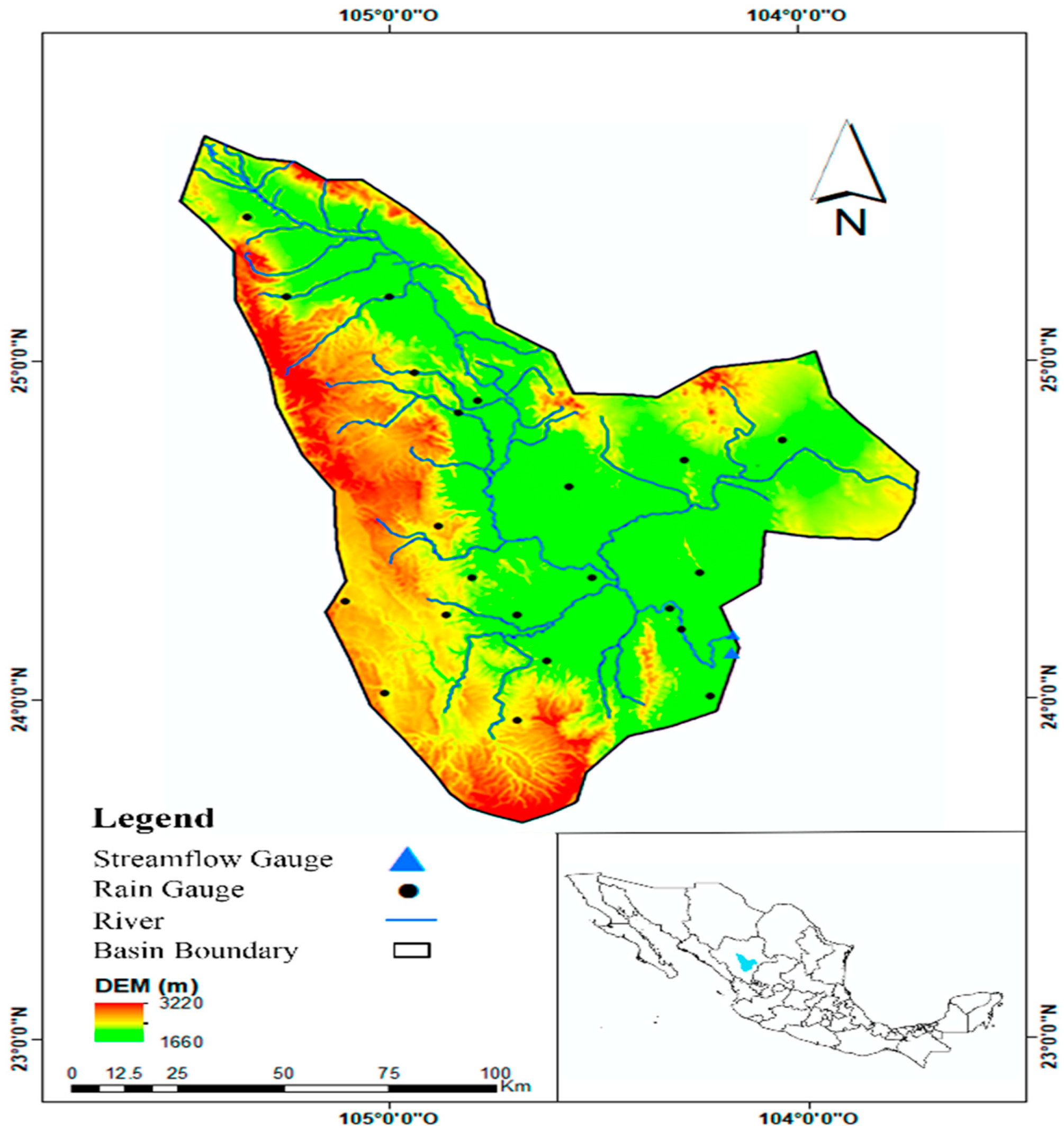

2.1. Study Area

| KEY | NAME | STATE | LAT | LON | HEIGHT (msnm) |

Topograpy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10002 | Canatlán/SMN) | Durango | 24.55 | 104.74 | 1960 | Plane |

| 10016 | Chinacates | Durango | 25.01 | 105.21 | 2050 | Mountain |

| 10022 | El Pino | Durango | 24.62 | 104.87 | 2100 | Mountain |

| 10024 | El Saltito | Durango | 24.03 | 104.35 | 1847 | Plane |

| 10027 | Francisco I. Madero | Durango | 24.4 | 104.32 | 1960 | Plane |

| 10030 | Guadalupe Victoria [40] | Durango | 24.45 | 104.12 | 2000 | Plane |

| 10051 | Otinapa | Durango | 24.05 | 105.01 | 2400 | Mountain |

| S10066 | San José de Acevedo | Durango | 23.81 | 104.27 | 2100 | Mountain |

| 10076 | Santiago Bayacora | Durango | 23..9 | 104.6 | 2150 | Mountain |

| 10083 | Tejamén | Durango | 24.81 | 105.13 | 1930 | Plane |

| 10090 | Canatlán [40] | Durango | 24.52 | 104.78 | 2000 | Plane |

| 10092 | Durango [40] | Durango | 24.02 | 104.67 | 1900 | Plane |

| 10103 | Santa Barbara [40] | Durango | 23.82 | 104.93 | 2260 | Mountain |

| 10110 | Hacienda La Pila | Durango | 24.12 | 104.29 | 1890 | Plane |

| 10137 | Guatimape | Durango | 24.81 | 104.92 | 1974 | Plane |

2.2. Datos

2.2.1. Satellite Precipitation Products

2.2.2. Rain and Hydrometric Gauge Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Extreme Rainfall and Runoff Indices

2.3.2. Accuracy Assessment Methods

2.3.3. Hydrologic Model Calibration

3. Results and Discussion

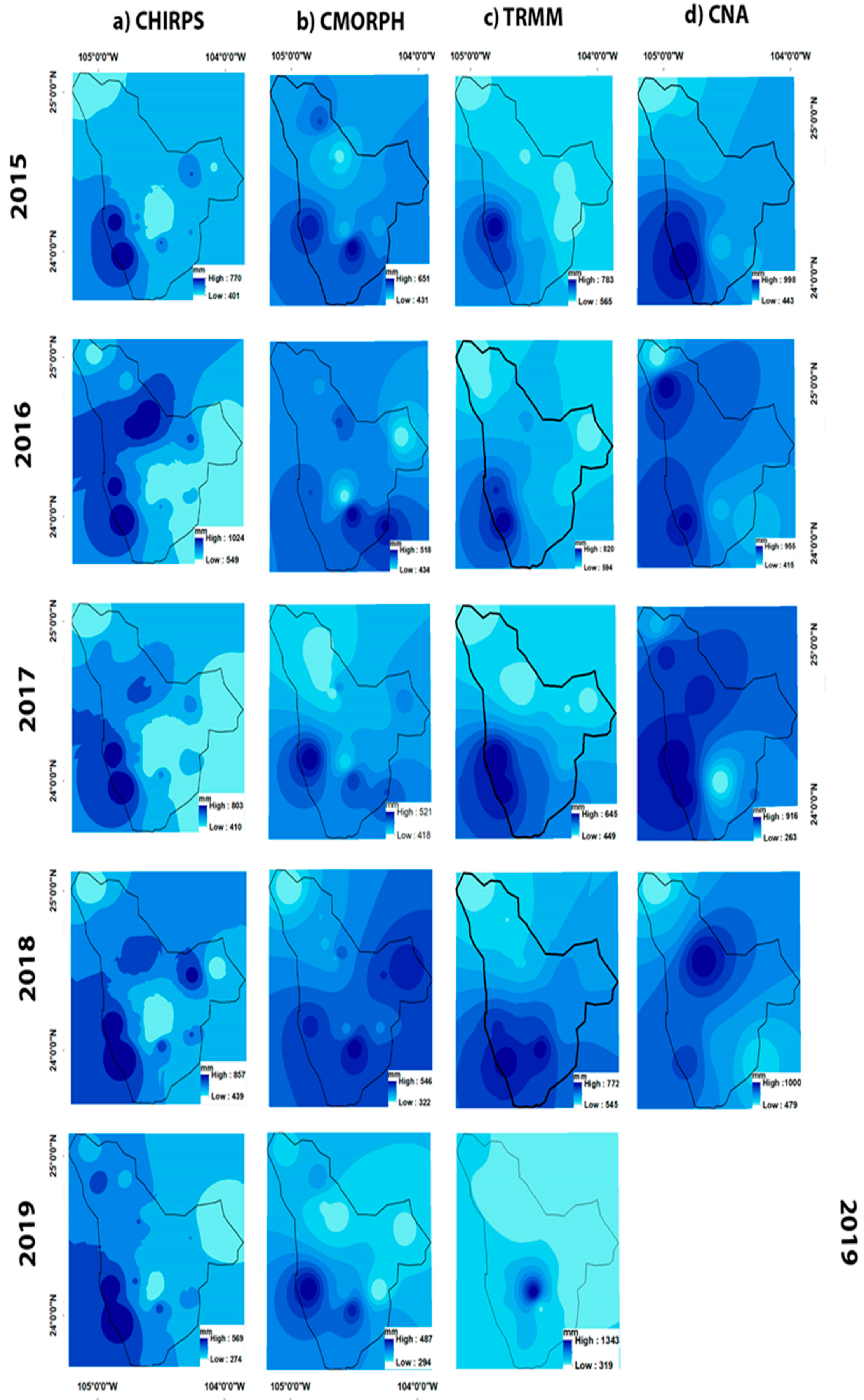

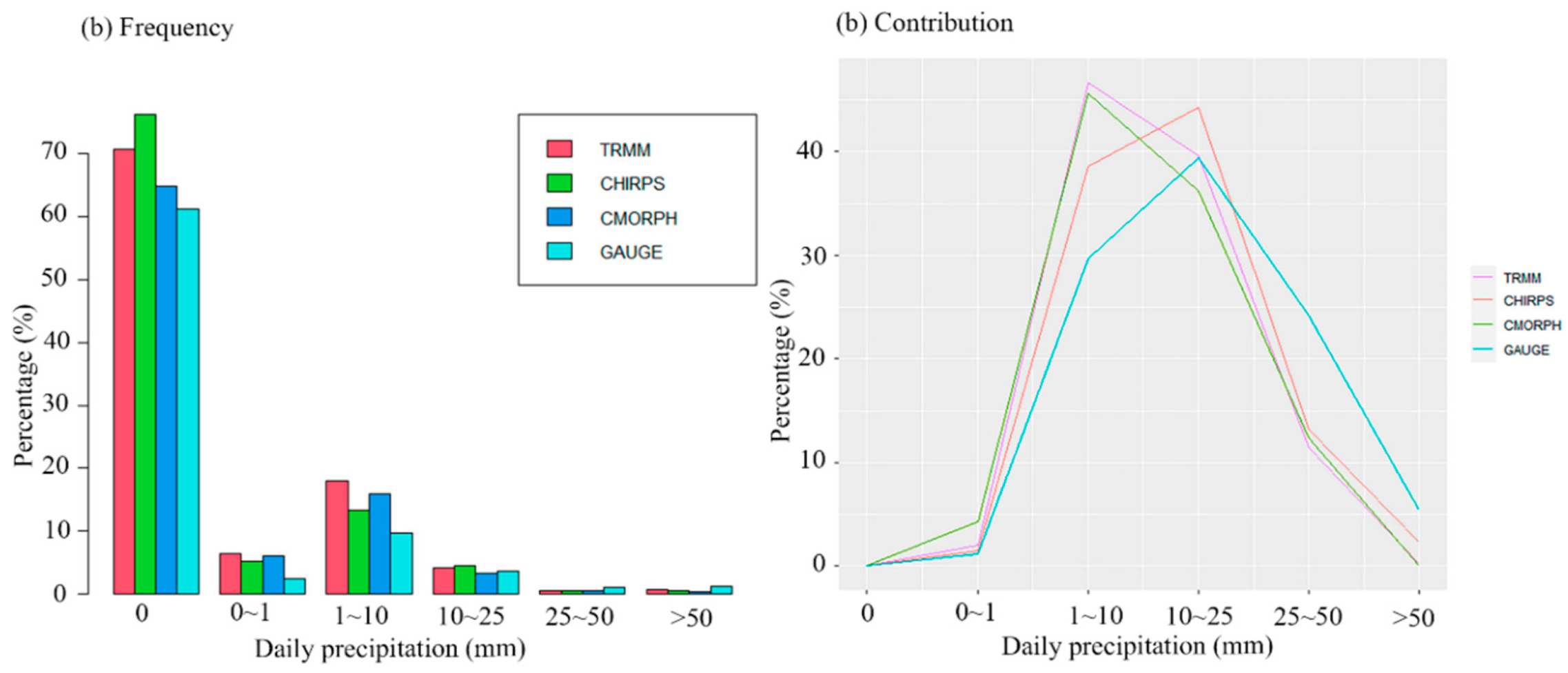

3.1. Satellite Product Comparison

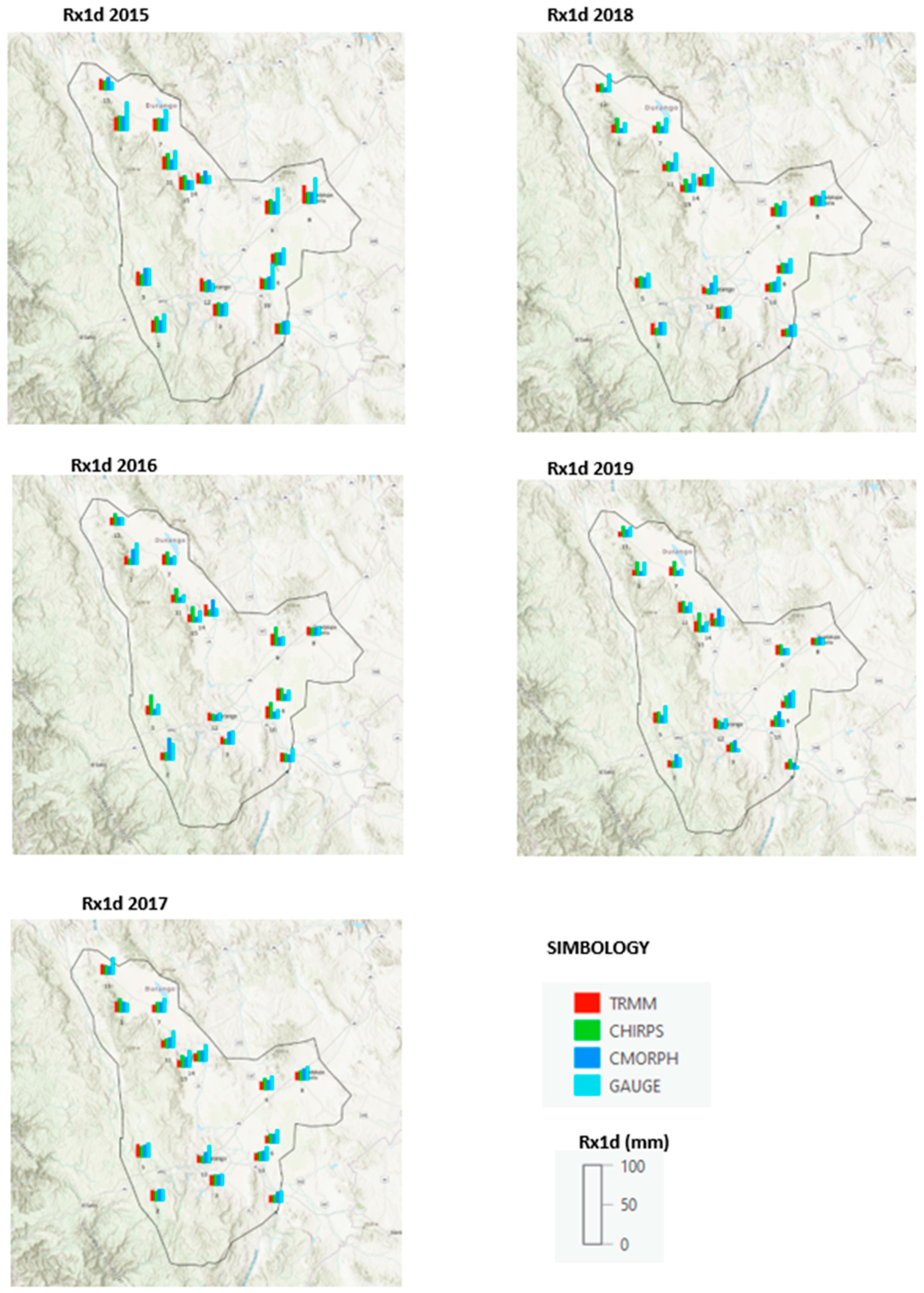

3.2. The Efficiency of PPS in Monitoring Extreme Precipitation Events

3.3. The performance of SPPs in Extreme Flow Capture

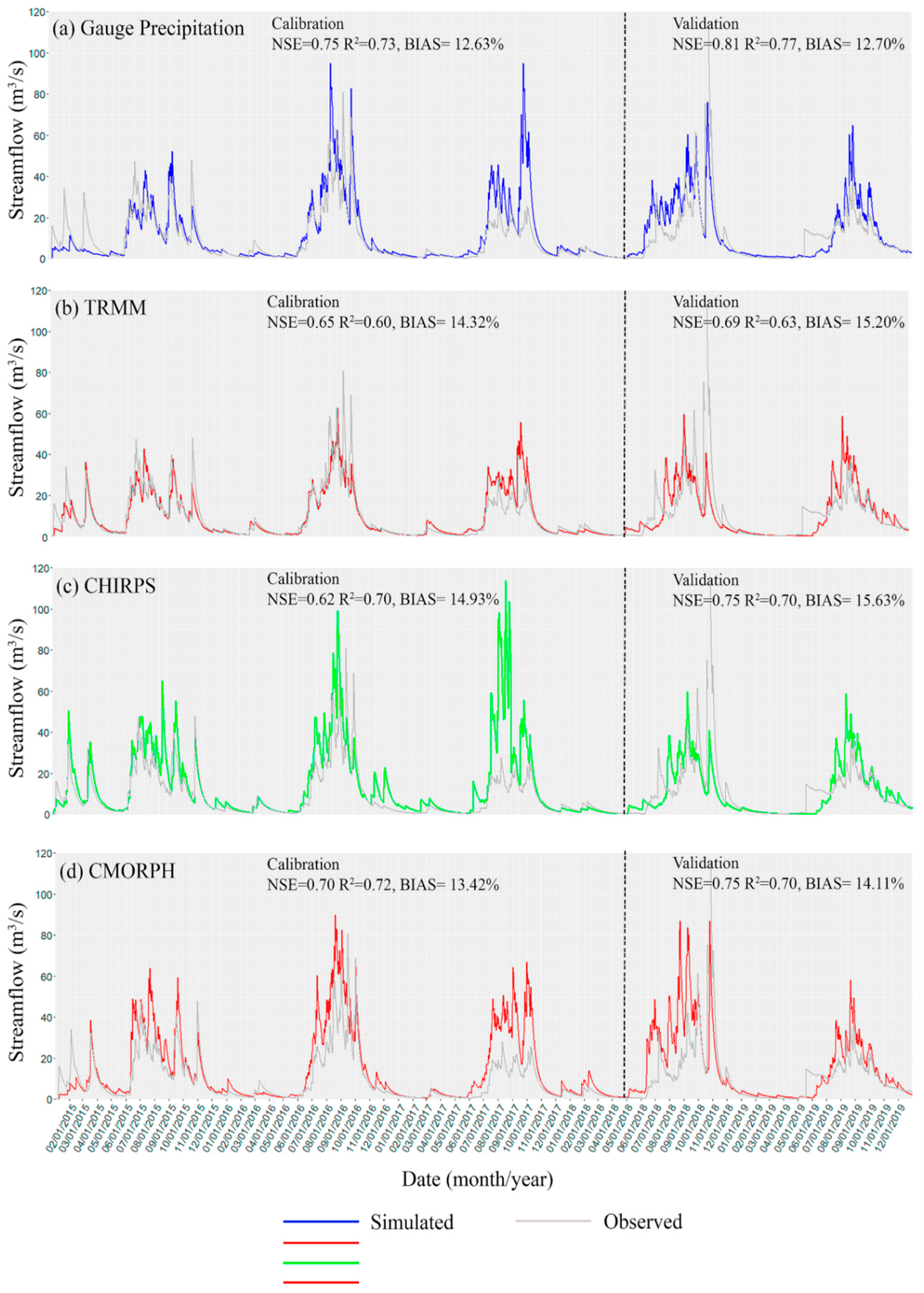

3.3.1. Validation of the PCSWMM Model

3.3.2. Extreme Flow Assessment of the Three PPSs

| Extreme runoff indices | Statistical results | TRMM | CHIRPS | CMORPH | Precipitation Gauge (CONAGUA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qx1d | R | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.95 |

| RMSE (mm) | 174.80 | 153.74 | 185.78 | ||

| ME (mm) | 17.25 | 5.38 | 17.35 | ||

| BIAS (%) | -11.40 | -1.54 | -12.40 | 3.0 | |

| Qx3d | R | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.94 |

| RMSE (mm) | 4.10 | 4.088 | 4.089 | ||

| ME (mm) | 2.83 | 2.85 | 2.83 | ||

| BIAS (%) | 35.86 | 14.36 | 36.16 | 3.5 | |

| Qx5d | R | -0.183 | 0.006 | 0.123 | 0.93 |

| RMSE (mm) | 21.15 | 20.81 | 21.17 | ||

| ME (mm) | 15.34 | 15.14 | 15.42 | ||

| BIAS (%) | -15.48 | -23.88 | -2.50 | 3.2 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Myhre, G.; Alterskjær, K.; Stjern, C.W.; Hodnebrog, Ø.; Marelle, L.; Samset, B.H.; Sillmann, J.; Schaller, N.; Fischer, E.; Schulz, M.; et al. Frequency of extreme precipitation increases extensively with event rareness under global warming. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 16063. [CrossRef]

- Papalexiou, S.M.; Montanari, A.J.W.R.R. Global and regional increase of precipitation extremes under global warming. 2019, 55, 4901-4914. [CrossRef]

- Flint, L.E.; Flint, A.L.; Stolp, B.J.; Danskin, W.R. A basin-scale approach for assessing water resources in a semiarid environment: San Diego region, California and Mexico. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 3817-3833. [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Pisani, B.; Hernández, H.; Li, Y.J.B.d.l.S.G.M. Assessing the impact of climate change on water resources in a semi-arid area in central Mexico using a SWAT model. 2020, 72. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Accuracy of satellite precipitation products in data-scarce Inner Tibetan Plateau comprehensively evaluated using a novel ground observation network. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2023, 47, 101405. [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.; Roshun, S.H.; Booij, M.J. Comparison of satellite-based and reanalysis precipitation products for hydrological modeling over a data-scarce region. Climate Dynamics 2024, 62, 3505-3537. [CrossRef]

- Tavakol-Davani, H.; Goharian, E.; Hansen, C.H.; Tavakol-Davani, H.; Apul, D.; Burian, S.J. How does climate change affect combined sewer overflow in a system benefiting from rainwater harvesting systems? Sustainable Cities and Society 2016, 27, 430-438. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yang, Y.; Xia, J. Hydrological cycle and water resources in a changing world: A review. Geography and Sustainability 2021, 2, 115-122. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Chaosakul, T.; Priyankara, D.P.; Chuyen, L.H.; Myat, S.S.; Syne, N.K.; Irvine, K.N.; Koottatep, T.; Babel, M.S.J.J.o.W.M.M. Application of PCSWMM to explore possible climate change impacts on surface flooding in a Peri-urban area of Pathumthani, Thailand. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Schuurmans, J.M.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Effect of spatial distribution of daily rainfall on interior catchment response of a distributed hydrological model. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 677-693. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.K.J.A.J.o.C.C. Markers for global climate change and its impact on social, biological and ecological systems: A review. 2020, 9, 159. [CrossRef]

- Rijal, M.; Luo, P.; Mishra, B.K.; Zhou, M.; Wang, X. Global systematical and comprehensive overview of mountainous flood risk under climate change and human activities. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 941, 173672. [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, S.; Levizzani, V.; Anagnostou, E.; Bauer, P.; Kasparis, T.; Lane, J.E. Precipitation: Measurement, remote sensing, climatology and modeling. Atmospheric Research 2009, 94, 512-533. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, R.J.; Janowiak, J.E.; Arkin, P.A.; Xie, P. CMORPH: A Method that Produces Global Precipitation Estimates from Passive Microwave and Infrared Data at High Spatial and Temporal Resolution %J Journal of Hydrometeorology. 2004, 5, 487-503. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, L. Rainfall Spatial Estimations: A Review from Spatial Interpolation to Multi-Source Data Merging. 2019, 11, 579. [CrossRef]

- Chintalapudi, S.; Sharif, H.O.; Yeggina, S.; Elhassan, A. Physically Based, Hydrologic Model Results Based on Three Precipitation Products. 2012, 48, 1191-1203. [CrossRef]

- Tsintikidis, D.; Georgakakos, K.P.; Sperfslage, J.A.; Smith, D.E.; Carpenter, T.M. Precipitation Uncertainty and Raingauge Network Design within Folsom Lake Watershed. 2002, 7, 175-184. [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Nicholson, S.E.; Landsfeld, M.; Klotter, D.; Peterson, P.; Harrison, L. The Centennial Trends Greater Horn of Africa precipitation dataset. Scientific Data 2015 b, 2, 150050. [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Landsfeld, M.; Pedreros, D.; Verdin, J.; Shukla, S.; Husak, G.; Rowland, J.; Harrison, L.; Hoell, A.; et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Scientific Data 2015 a, 2, 150066. [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Trejo, F.J.; Barbosa, H.A.; Lakshmi Kumar, T.V. Validating CHIRPS-based satellite precipitation estimates in Northeast Brazil. Journal of Arid Environments 2017, 139, 26-40. [CrossRef]

- Katsanos, D.; Retalis, A.; Tymvios, F.; Michaelides, S. Analysis of precipitation extremes based on satellite (CHIRPS) and in situ dataset over Cyprus. Natural Hazards 2016, 83, 53-63. [CrossRef]

- Poméon, T. Evaluating the Contribution of Remote Sensing Data Products for Regional Simulations of Hydrological Processes in West Africa using a Multi-Model Ensemble. Dissertation, Bonn, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, 2019, 2019.

- Maggioni, V.; Nikolopoulos, E.I.; Anagnostou, E.N.; Borga, M.J.I.T.o.G.; Sensing, R. Modeling satellite precipitation errors over mountainous terrain: The influence of gauge density, seasonality, and temporal resolution. 2017, 55, 4130-4140. [CrossRef]

- Sayama, T.; Ozawa, G.; Kawakami, T.; Nabesaka, S.; Fukami, K. Rainfall–runoff–inundation analysis of the 2010 Pakistan flood in the Kabul River basin. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2012, 57, 298-312. [CrossRef]

- Skofronick-Jackson, G.; Berg, W.; Kidd, C.; Kirschbaum, D.B.; Petersen, W.A.; Huffman, G.J.; Takayabu, Y.N. Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM): Unified Precipitation Estimation from Space. In Remote Sensing of Clouds and Precipitation, Andronache, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 175-193.

- You, Y.; Wang, N.-Y.; Kubota, T.; Aonashi, K.; Shige, S.; Kachi, M.; Kummerow, C.; Randel, D.; Ferraro, R.; Braun, S.; et al. Comparison of TRMM Microwave Imager Rainfall Datasets from NASA and JAXA %J Journal of Hydrometeorology. 2020, 21, 377-397. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Austin, G. Studies of General Precipitation Features with TRMM PR Data: An Extensive Overview. 2019, 11, 80. [CrossRef]

- George Huffman, W.M., Charles Cosner and Jacob Reed. Global Precipitation Measurement. The Global Precipitation Measurement Mission (GPM). Earth Science Division/National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2024.

- Demirdjian, L.; Zhou, Y.; Huffman, G.J. Statistical Modeling of Extreme Precipitation with TRMM Data %J Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. 2018, 57, 15-30. [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, J.; Wood, E.F.; Pan, M.; Beck, H.; Coccia, G.; Serrat-Capdevila, A.; Verbist, K.J.W.R.R. Satellite remote sensing for water resources management: Potential for supporting sustainable development in data-poor regions. 2018, 54, 9724-9758. [CrossRef]

- Pakoksung, K.; Takagi, M. Effect of satellite based rainfall products on river basin responses of runoff simulation on flood event. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment 2016, 2, 143. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Ghosh, S.K.; Chen, J. Spatial Interpolation. In Semantic Kriging for Spatio-temporal Prediction; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; pp. 19-41.

- Wu, Y.-H.; Hung, M.-C.J.A.o.s.s. Comparison of spatial interpolation techniques using visualization and quantitative assessment. 2016, 17-34. [CrossRef]

- Kuras, A. Airborne hyperspectral imaging for multisensor data fusion. 2023.

- Ye, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liang, L.; Tian, J.J.R.S. Extensive evaluation of four satellite precipitation products and their hydrologic applications over the Yarlung Zangbo River. 2022, 14, 3350. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Petersen, W.A.; Wolff, D.B. Validation of Satellite-Based Precipitation Products from TRMM to GPM. 2021, 13, 1745. [CrossRef]

- Kidd, C.; Matsui, T.; Blackwell, W.; Braun, S.; Leslie, R.; Griffith, Z. Precipitation Estimation from the NASA TROPICS Mission: Initial Retrievals and Validation. 2022, 14, 2992. [CrossRef]

- Adam Hernández Hernández, M.L.A.J., Ramón Domínguez Mora, ; Ibarra, E.C.E.e.I.P. HIDROGRAMAS DE DISEÑO OBTENIDO CON ANÁLISIS DE ESCURRIMIENTOS. UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA 2018.

- Banco, I.M.D.T.D.A.; (BANDAS)., N.d.D.d.A.S. Regiones hidrologicas administrativas. 2020.

- Tu, M.-c.; Wadzuk, B.; Traver, R.J.P.O. Methodology to simulate unsaturated zone hydrology in storm water management model (SWMM) for green infrastructure design and evaluation. 2020, 15, e0235528. [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.E.; Rilee, M.L. Remote sensing tools for exploration: observing and interpreting the electromagnetic spectrum; Springer Science & Business Media: 2010.

- Awasthi, N.; Tripathi, J.N.; Petropoulos, G.P.; Gupta, D.K.; Singh, A.K.; Kathwas, A.K. Performance Assessment of Global-EO-Based Precipitation Products against Gridded Rainfall from the Indian Meteorological Department. 2023, 15, 3443.

- Harrison, L.; Landsfeld, M.; Husak, G.; Davenport, F.; Shukla, S.; Turner, W.; Peterson, P.; Funk, C. Advancing early warning capabilities with CHIRPS-compatible NCEP GEFS precipitation forecasts. Scientific Data 2022, 9, 375. [CrossRef]

- Koo, M.-S.; Hong, S.-Y.; Kim, J.J.A.-P.J.o.A.S. An evaluation of the tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) multi-satellite precipitation analysis (TMPA) data over South Korea. 2009, 45, 265-282.

- Prat, O.P.; Nelson, B.R.J.W.R.R. Mapping the world's tropical cyclone rainfall contribution over land using the TRMM Multi-satellite Precipitation Analysis. 2013, 49, 7236-7254. [CrossRef]

- Council, N.R.; Policy, B.o.H.S.; Earth, D.o.; Studies, L.; Sciences, B.o.E.; Resources; Science, C.o.R.P.f.E.; Health, P. Earth materials and health: Research priorities for earth science and public health; National Academies Press: 2007.

- Nakamura, K.J.J.o.t.M.S.o.J.S.I. Progress from TRMM to GPM. 2021, 99, 697-729.

- Kummerow, C.; Simpson, J.; Thiele, O.; Barnes, W.; Chang, A.; Stocker, E.; Adler, R.; Hou, A.; Kakar, R.; Wentz, F.J.J.o.A.M.; et al. The status of the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) after two years in orbit. 2000, 39, 1965-1982. [CrossRef]

- Zagrodnik, J.P. Comparison and validation of Tropical Rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) Rainfall algorithms in Tropical Cyclones. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Kummerow, C.; Simpson, J.; Thiele, O.; Barnes, W.; Chang, A.; Stocker, E.; Adler, R.; Hou, A.; Kakar, R.; Wentz, F. The status of the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) after 2 years in orbit. 1999.

- YANG, R.; RUI, H. APPLICATIONS OF TRMM SCIENTIFIC DATA. In Observation, Theory and Modeling of Atmospheric Variability; pp. 473-483.

- Cheema, M.J.M.; Bastiaanssen, W.G.M. Local calibration of remotely sensed rainfall from the TRMM satellite for different periods and spatial scales in the Indus Basin. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2012, 33, 2603-2627. [CrossRef]

- Kummerow, C.; Olson, W.S.; Giglio, L.J.I.T.o.G.; Sensing, R. A simplified scheme for obtaining precipitation and vertical hydrometeor profiles from passive microwave sensors. 1996, 34, 1213-1232. [CrossRef]

- Giglio, L.; Kendall, J.D.; Tucker, C.J. Remote sensing of fires with the TRMM VIRS. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2000, 21, 203-207. [CrossRef]

- Weng, F.; Zhao, L.; Ferraro, R.R.; Poe, G.; Li, X.; Grody, N.C.J.R.S. Advanced microwave sounding unit cloud and precipitation algorithms. 2003, 38, 33-31-33-13. [CrossRef]

- Bruster-Flores, J.L.; Ortiz-Gómez, R.; Ferriño-Fierro, A.L.; Guerra-Cobián, V.H.; Burgos-Flores, D.; Lizárraga-Mendiola, L.G.J.W. Evaluation of precipitation estimates CMORPH-CRT on regions of Mexico with different climates. 2019, 11, 1722. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xia, J.; She, D.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Zou, L.J.R.S. Evaluation of six satellite-based precipitation products and their ability for capturing characteristics of extreme precipitation events over a climate transition area in China. 2019, 11, 1477.

- Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Qi, W.; Xu, C.-Y.; Kim, J.-S. Evaluation of Multi-Satellite Precipitation Datasets and Their Error Propagation in Hydrological Modeling in a Monsoon-Prone Region. 2020, 12, 3550. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Liu, J.; Tuo, Y.; Chiogna, G.; Disse, M. Evaluation of eight high spatial resolution gridded precipitation products in Adige Basin (Italy) at multiple temporal and spatial scales. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 573, 1536-1553. [CrossRef]

- Filianoti, P.; Gurnari, L.; Zema, D.A.; Bombino, G.; Sinagra, M.; Tucciarelli, T. An Evaluation Matrix to Compare Computer Hydrological Models for Flood Predictions. 2020, 7, 42. [CrossRef]

- Yosef, Y.; Aguilar, E.; Alpert, P.J.I.J.C. Is it possible to fit extreme climate change indices together seamlessly in the era of accelerated warming. 2021, 41, E952-E963. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Dereczynski, C.; Freitas, M.A.V.; Chou, S.C. Climate Change Index: A Proposed Methodology for Assessing Susceptibility to Future Climatic Extremes %J American Journal of Climate Change. 2014, Vol.03No.03, 12. [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Sterl, A.J.J.o.G.R.A. Global changes in indices describing moderate temperature extremes from the daily output of a climate model. 2011, 116. [CrossRef]

- Codjoe, S.N.; Atiglo, D.Y.J.F.i.C. The implications of extreme weather events for attaining the sustainable development goals in sub-Saharan Africa. 2020, 2, 592658. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Alnahit, A.; Campbell, B. Impact of land uses, drought, flood, wildfire, and cascading events on water quality and microbial communities: A review and analysis. Journal of Hydrology 2021, 596, 125707. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Rahman, A.; Haddad, K.; Ouarda, T.B.J.S.E.R.; Assessment, R. Peaks-over-threshold model in flood frequency analysis: a scoping review. 2022, 36, 2419-2435. [CrossRef]

- Norheim, S. Flood frequency analysis: Comparing annual maximum series and peak over threshold: A case study for Norway. Høgskulen på Vestlandet, 2018.

- Mostofi Zadeh, S.; Durocher, M.; Burn, D.H.; Ashkar, F.J.H.S.J. Pooled flood frequency analysis: a comparison based on peaks-over-threshold and annual maximum series. 2019, 64, 121-136.

- Wi, S.; Valdés, J.B.; Steinschneider, S.; Kim, T.-W.J.S.e.r.; assessment, r. Non-stationary frequency analysis of extreme precipitation in South Korea using peaks-over-threshold and annual maxima. 2016, 30, 583-606. [CrossRef]

- Dams, J.; Nossent, J.; Senbeta, T.B.; Willems, P.; Batelaan, O. Multi-model approach to assess the impact of climate change on runoff. Journal of Hydrology 2015, 529, 1601-1616. [CrossRef]

- Cooley, A.K.; Chang, H.J.J.o.W.; Change, C. Detecting change in precipitation indices using observed (1977–2016) and modeled future climate data in Portland, Oregon, USA. 2021, 12, 1135-1153. [CrossRef]

- Moran-Tejeda, E.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Ceballos-Barbancho, A.J.H.s.j. The contrasted evolution of high and low flows and precipitation indices in the Duero basin (Spain). 2012, 57, 591-611. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, V.; Harrington Jr, J.J.I.J.o.C. Assessment of climate change for extreme precipitation indices: A case study from the central United States. 2019, 39, 1013-1025. [CrossRef]

- Bitew, M.M.; Gebremichael, M. Assessment of satellite rainfall products for streamflow simulation in medium watersheds of the Ethiopian highlands. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 1147-1155. [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, V.; Massari, C. On the performance of satellite precipitation products in riverine flood modeling: A review. Journal of Hydrology 2018, 558, 214-224. [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, H. Hydrological modeling of a large urban catchment using a stormwater management model (SWMM). Aalto University, 2013.

- Zeng, Z.; Yuan, X.; Liang, J.; Li, Y. Designing and implementing an SWMM-based web service framework to provide decision support for real-time urban stormwater management. Environmental Modelling & Software 2021, 135, 104887. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Woo, W.; Park, Y.S. A User-Friendly Software Package to Develop Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) Inputs and Suggest Low Impact Development Scenarios. 2020, 12, 2344. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qiao, W.; Xiao, Y.; Lu, Y.J.N.H. Analysis of regional flooding in the urbanization expansion process based on the SWMM model. 2023 a, 117, 1349-1363. [CrossRef]

- Dell, T.; Razzaghmanesh, M.; Sharvelle, S.; Arabi, M. Development and Application of a SWMM-Based Simulation Model for Municipal Scale Hydrologic Assessments. 2021, 13, 1644.

- Montalvo, C.; Reyes-Silva, J.D.; Sañudo, E.; Cea, L.; Puertas, J. Urban pluvial flood modelling in the absence of sewer drainage network data: A physics-based approach. Journal of Hydrology 2024, 634, 131043. [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Hall, M.; Hong, B.; Zhang, L. Impact of SWMM Catchment Discretization: Case Study in Syracuse, New York. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 2014, 19, 223-234. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T.; Capozzoli, C.R.; Rafee, S.A.A.; de Freitas, E.D. Hydrological Modeling of Urbanized Basins. In Environmental Governance of the São Paulo Macrometropolis: Perspectives on Climate Variability, Jacobi, P.R., Turra, A., Bermann, C., Freitas, E.D.d., Frey, K., Giatti, L.L., Travassos, L., Sinisgalli, P.A.d.A., Momm, S., Zanirato, S., et al., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 231-240.

- Gichamo, T.; Nourani, V.; Gökçekuş, H.; Gelete, G.J.J.o.W.; Change, C. Ensemble rainfall–runoff modeling of physically based semi-distributed models using multi-source rainfall data fusion. 2024, 15, 325-347. [CrossRef]

- Snikitha, S.; Kumar, G.P.; Dwarakish, G.S. A Comprehensive Review of Cutting-Edge Flood Modelling Approaches for Urban Flood Resilience Enhancement. Water Conservation Science and Engineering 2024, 10, 2. [CrossRef]

- Abedin, S.; MacVicar, B. Understanding the impacts of hydraulic uncertainties on urban flood mapping. In River Flow 2022; CRC Press: 2024; pp. 1028-1034.

- Manandhar, B.; Cui, S.; Wang, L.; Shrestha, S. Urban Flood Hazard Assessment and Management Practices in South Asia: A Review. 2023, 12, 627. [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, F. Modeling the effectiveness of flood adaptation strategies under climate change. Drexel University, 2024.

- Mayou, L.A.; Alamdari, N.; Ahmadisharaf, E.; Kamali, M. Impacts of future climate and land use/land cover change on urban runoff using fine-scale hydrologic modeling. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 362, 121284. [CrossRef]

- Khatooni, K.; Hooshyaripor, F.; MalekMohammadi, B.; Noori, R. A new approach for urban flood risk assessment using coupled SWMM–HEC-RAS-2D model. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 374, 123849. [CrossRef]

- Sañudo, E.; Cea, L.; Puertas, J. Modelling Pluvial Flooding in Urban Areas Coupling the Models Iber and SWMM. 2020, 12, 2647. [CrossRef]

- Zafeirakos, N. A study on the Mandra flash flood of 2017 using a coupled 1D/2D model (SWMM/P-DWave). 2020.

- de Lourdes Corral-Bermudez, M.; Sánchez-Ortiz, E.; Álvarez-Bernal, D.; Gutiérrez-Montenegro, M.O.; Cassio-Madrazo, E.J.P. Scenarios of availability of water due to overexploitation of the aquifer in the basin of Laguna de Santiaguillo, Durango, Mexico. 2019, 7, e6814. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.; Levresse, G.; Aranda-Gómez, J.J.; Henry, C.D.; Valencia-Moreno, M.; Landín, L.O.; Ferrari, L.; Levresse, G.; Aranda-Gómez, J.J.; Henry, C.D.; et al. Tectonomagmatic Pulses and Multiphase Mineralization in the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico. In Tectonomagmatic Pulses and Multiphase Mineralization in the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico; Society of Economic Geologists: 2020; Volume 61, p. 0.

- Qiu, Y.; da Silva Rocha Paz, I.; Chen, F.; Versini, P.A.; Schertzer, D.; Tchiguirinskaia, I. Space variability impacts on hydrological responses of nature-based solutions and the resulting uncertainty: a case study of Guyancourt (France). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 3137-3162. [CrossRef]

- Gwak, Y.; Kim, S.J.H.P. Factors affecting soil moisture spatial variability for a humid forest hillslope. 2017, 31, 431-445. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Han, H.J.A.R. Evaluation of the CMORPH high-resolution precipitation product for hydrological applications over South Korea. 2021, 258, 105650. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Shao, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, T.; Chen, C.; Ding, Q.; Du, H. Evaluation and Intercomparison of High-Resolution Satellite Precipitation Estimates—GPM, TRMM, and CMORPH in the Tianshan Mountain Area. 2018, 10, 1543. [CrossRef]

- Katiraie-Boroujerdy, P.-S.; Nasrollahi, N.; Hsu, K.-l.; Sorooshian, S. Evaluation of satellite-based precipitation estimation over Iran. Journal of Arid Environments 2013, 97, 205-219. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Xiong, A.; Wang, Y.; Xie, P.J.J.o.G.R.A. Performance of high-resolution satellite precipitation products over China. 2010, 115. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Xia, J.; Zou, L. Evaluation of Multi-Satellite Precipitation Products and Their Ability in Capturing the Characteristics of Extreme Climate Events over the Yangtze River Basin, China. 2020, 12, 1179. [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Landsfeld, M.; Pedreros, D.; Verdin, J.; Shukla, S.; Husak, G.; Rowland, J.; Harrison, L.; Hoell, A.J.S.d. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. 2015, 2, 1-21.

- Beck, H.E.; Van Dijk, A.I.; Levizzani, V.; Schellekens, J.; Miralles, D.G.; Martens, B.; De Roo, A.J.H.; Sciences, E.S. MSWEP: 3-hourly 0.25 global gridded precipitation (1979–2015) by merging gauge, satellite, and reanalysis data. 2017, 21, 589-615.

- Guo, H.; Bao, A.; Liu, T.; Chen, S.; Ndayisaba, F. Evaluation of PERSIANN-CDR for Meteorological Drought Monitoring over China. 2016, 8, 379. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Bao, A.; Liu, T.; Ndayisaba, F.; He, D.; Kurban, A.; De Maeyer, P. Meteorological Drought Analysis in the Lower Mekong Basin Using Satellite-Based Long-Term CHIRPS Product. 2017, 9, 901. [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Ashouri, H.; Hsu, K.-L.; Sorooshian, S.; Duan, Q. Evaluation of the PERSIANN-CDR Daily Rainfall Estimates in Capturing the Behavior of Extreme Precipitation Events over China %J Journal of Hydrometeorology. 2015, 16, 1387-1396. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shi, Z.; Liu, R.; Xing, M. Evaluating the performance of global precipitation products for precipitation and extreme precipitation in arid and semiarid China. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2024, 130, 103888. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, M.; Nzabarinda, V.; Bao, A.; Meng, X.; Zhu, L.; De Maeyer, P. Assessment of Three Long-Term Satellite-Based Precipitation Estimates against Ground Observations for Drought Characterization in Northwestern China. 2022, 14, 828. [CrossRef]

- Manchikatla, S.K.; Umamahesh, N.J.W.P. Simulation of flood hazard, prioritization of critical sub-catchments, and resilience study in an urban setting using PCSWMM: a case study. 2022, 24, 1247-1268. [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.N.; Chua, L.H.C.J.J.o.W.M.M. Modeling stormwater runoff from an urban park, Singapore using PCSWWM. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L.J.T.o.t.A. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. 2007, 50, 885-900. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cruz, D.; Gutiérrez, M.; Alarcón-Herrera, M.J.S.o.F.D.; Challenges, C.C.i.t.G.S.; Agenda, O.f.t. Spatial and temporal analysis of precipitation and drought trends using the climate forecast system reanalysis (CFSR). 2020, 129-146.

- Agel, L.; Barlow, M.; Qian, J.-H.; Colby, F.; Douglas, E.; Eichler, T. Climatology of Daily Precipitation and Extreme Precipitation Events in the Northeast United States %J Journal of Hydrometeorology. 2015, 16, 2537-2557. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Wang, K. The Role of Satellite-Based Remote Sensing in Improving Simulated Streamflow: A Review. 2019, 11, 1615. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Lombardo, L.; Gariano, S.L.; Cheng, W.; Liu, C.; Xiong, J.; Wang, R. Using satellite rainfall products to assess the triggering conditions for hydro-morphological processes in different geomorphological settings in China. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 102, 102350. [CrossRef]

| Short name | Spatial coverage | Reference | Time span | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHIRPS | 50°S-50°N | (Funk et al., 2015) | 1981—present | https://www.chc.uc sb.edu/data/chirps/ |

| CMORPH | 60°S-60°N | (Joyce et al., 2004) | 1998—present | ftp://ftp.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/precip/ CMORPH_V1.0/ |

| TRMM | 35°S-35°N | (National Research Council 2006) | 1997-present | https://gpm.nasa.gov/missions/trmm/mission-end |

| Category | ID | Definition | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme precipitation indices | RR95p | The 95th percentile of daily precipitation on wet days (days with daily precipitation ≥1 mm) | mm/día |

| R25mm | Annual count of days when daily precipitation is ≥25 mm | días | |

| Rx1d | Maximum annual precipitation of 1 day | mm | |

| Rx2d | Annual maximum of 5 days of consecutive precipitation | mm | |

| Extreme flow rates | Qx1d | Maximum annual flow rate of 1 day | m3/S |

| Qx2d | Maximum annual flow rate of 2 days | m3/S | |

| Qx3d | Maximum annual flow rate of 3 days | m3/S |

| Statistical index | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Bias volume (%) | (1) | |

| Mean square error | (2) | |

| Correlation | (3) | |

| Medium bias |

where Qv is the volume of observation Qvs is the volume simulation Qpo is the observation peak Qps is the simulation peak Qo is the data of observation Qs is the simulation data n is the total sample number. |

(4) |

| Parameters and attributes | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Area | Watershed area (hectares or acres) | |

| Width | Characteristic width of the flow path due to the runoff superficial. | |

| %Slope | Average slope of the basin in % | |

| %Imprev | Percentage of watershed whose soil is impermeable. | |

| N-Inprev | Manning's n coefficient for surface flow over the área Waterproof over the basin. | |

| N-Prev | Manning's N coefficient for surface flow over the área permeable over the basin. | |

| Dstore-Imperv | Storage height in depression above the Impermeable area of the basin. | |

| Dstore-Prev | Storage height in depression above the area permeable of the basin. | |

| %Zero-Imprev | Percentage of impermeable soil that does not have depression storage. | |

| Percent Routed | Percentage of runoff between different areas | |

| Infiltration | Infiltration is the process of precipitation that penetrates the Soil surface in the unsaturated soil zone of permeable catchment sub-areas SWMM offers five models as an option in infiltration modeling: Horton's classical method. Horton's Modified Method. Green-Ampt Method. Modified Green-Ampt method. Curve Number Method. |

|

| Extreme precipitation indices | Statistical results | TRMM | CHIRPS | CMORPH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR95p | R | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.65 |

| RMSE (mm) | 150.00 | 120.00 | 160.00 | |

| ME (mm) | 12.00 | 3.00 | 13.00 | |

| BIAS (%) | -8.00 | -0.50 | -9.00 | |

| R25mm | R | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.40 |

| RMSE (mm) | 3.50 | 3.20 | 3.40 | |

| ME (mm) | 2.20 | 2.00 | 2.20 | |

| BIAS (%) | 30.00 | 10.00 | 32.00 | |

| Rx1d | R | -0.10 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| RMSE (mm) | 18.00 | 16.50 | 18.50 | |

| ME (mm) | 12.00 | 11.50 | 12.50 | |

| BIAS (%) | -10.00 | -18.00 | -0.50 | |

| Rx3d | R | -0.10 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| RMSE (mm) | 30.00 | 28.00 | 31.00 | |

| ME (mm) | 25.00 | 24.00 | 25.50 | |

| BIAS (%) | -30.00 | -22.00 | -35.00 | |

| Rx5d | R | -0.08 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| RMSE (mm) | 29.50 | 27.50 | 30.00 | |

| ME (mm) | 25.00 | 24.00 | 25.50 | |

| BIAS (%) | -30.00 | -22.00 | -35.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).