Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

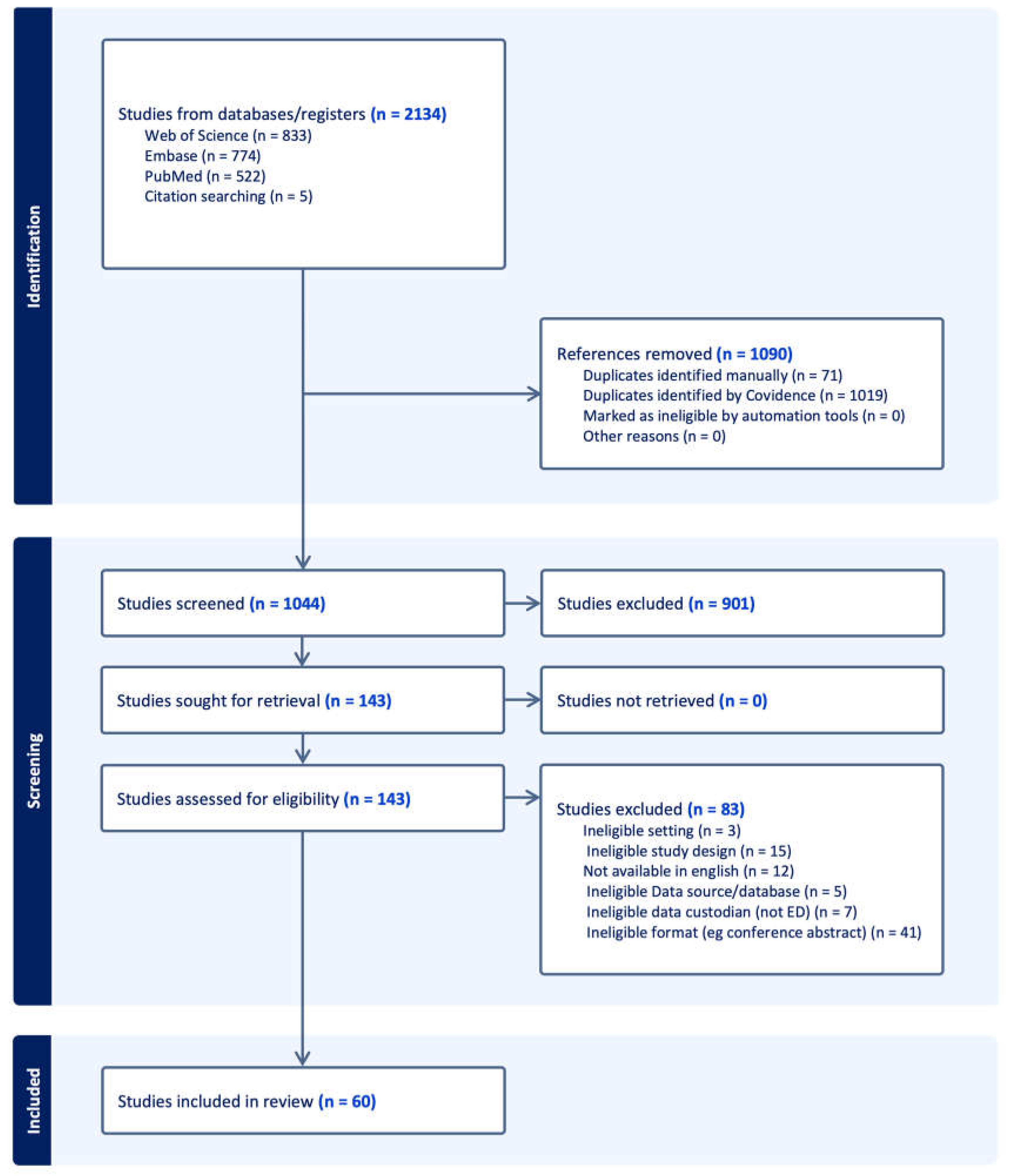

3.1. Search Results

| Scope | Primary registry publications 1 | Secondary publications 2 |

|---|---|---|

| General | 6 | 2 |

| Condition or population specific | 21 | 31 |

3.2. Characteristics of Primary ED Registry Publications

| Registry | Date Range | Country/ies | Number of EDs 3 | Condition or population | Funding | Associated studies 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Admission Database | Barford, 2012 | 22-09-2009 to 28-02-2010 | Denmark | 1 | General | Hillerød Hospital research grant. | 0 |

| American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Emergency Data Registry (CEDR) | Venkatesh, 2021 | 2017 1, 5 | USA | 889 | General | American College of Emergency Physicians | 0 |

| Centre des Urgences de Yaoundé (CURY) 4 | Jeong, 2022 | 01-2016 to 06-2018 1 | Africa | 1 | General | Korea International Cooperation Agency | 0 |

| Danish Database for Acute and Emergency Hospital Contacts (DDAEHC) | Lassen, 2016 | Not specified 5 | Denmark | 26 | General | Danish Regions. | 0 |

| Swedish Emergency Registry (SVAR) | Ekelund, 2011 | 01-01-2009 to 30-06-2009 1, 5 | Sweden | 6 | General | Region Skåne, the Stockholm County Council and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. | 1 |

| The Registry for Emergency Care (REC) | O’Reilly, 2020 | Not specified | Australia | 1 | General | No funding acknowledged. | 1 |

| Cleveland Clinic Emergency Airway Registry 4 | Phelan, 2010 | 01-07-2005 to 31-03-2007 | USA | 1 | Airway | No funding acknowledged. | 0 |

| Australia and New Zealand Emergency Department Airway Registry (ANZEDAR) | Fogg, 2016 | 01-04-2010 to 30-03-2014 5 | Australia | 1 | Airway | Emergency Care Institute research funding scheme. | 3 |

| Defense Registry for Emergency Airway Management (DREAM) | Mendez, 2021 | 01-2020 to 07-2020 1 | USA | 1 | Airway | No funding acknowledged. | 0 |

| Korean Emergency Airway Management Registry (KEAMR) | Choi, 2021 | 03-2006 to 12-2010 1 | Korea | 13 | Airway | No funding acknowledged. | 2 |

| National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) | Brown, 2015 | 01-07-2002 to 31-12-2012 5 | USA, Australia, Canada | 13 | Airway | No funding acknowledged. | 19 |

| South African Emergency Department Airway Registry 4 | Hart, 2020 | 01-09-2015 to 31-10-2016 1 | South Africa | 1 | Airway | No funding acknowledged. | 0 |

| Children's Injury Database (CID) | McCain, 2023 | 2021 1 | USA | 1 | Pediatric | No funding acknowledged. | 0 |

| Nicaragua Pediatric Emergency Registry 4 | Bressan, 2021 | 01-01-2017 to 31-12-2017 1 | Nicaragua | 7 | Pediatric | Regione Lombardia and the Associazione il Bambino Nefropatico | 0 |

| The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network Registry (PECARN) | Sara, 2018 | 01-2012 to 06-2016 1, 5 | USA | 7 | Pediatric | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 6. | 0 |

| Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry (EMPORER) | Pollack, 2011 | 01-01-2005 to 29-12-2008 | USA | 22 | Acute pulmonary embolism | GlaxoSmithKline. | 1 |

| Risk Profile of Patients VTED Attended in Spanish Emergency Departments Registry (ESPHERIA) | Jimenez, 2017 | 13-10-2014 to 14-12-2014 1 | Spain | 53 | Venous thromboembolism | Bayer Hispania. | 1 |

| Emergency Atrial Fibrillation Registry of the Catalan Institute of Health (URGFAICS) | Jacob, 2019 | 09-2016 to 02-2017 1 | Spain | 5 | Atrial fibrillation | No funding acknowledged. | 1 |

| Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments Registry (EAHFE) | Llorens, 2015 | 15-03 to 15-05-2007; 01-06 to 30-06-2009;07-11-2011 to 07-01-2012 | Spain | 29 | Heart failure | Partially funded by the Institute of Health. | 2 |

| Acute Epileptic Seizures in the Emergency Department Registry (ACESUR) | Alonso, 2019 | 01-02-2017 to 31-10-2017 | Spain | 18 | Acute epileptic seizures | No funding acknowledged. | 0 |

| Ain Shams University Hospital Trauma Registry 4 | Khalil, 2021 | 01-2017 to 12-2017 | Egypt | 1 | Trauma | Fogarty Institute in USA. | 0 |

| Auckland City Hospital Emergency Department Overdose Database | Theron, 2017 | 2002 to 2004 1 | New Zealand | 1 | Overdose | No funding acknowledged. | 0 |

| Emergency Medicine Events Register (EMER) | Hansen, 2016 | 12-2012 to 02-2015 1 | Australia, New Zealand | 21 | Safety incidents | Australasian College for Emergency Medicine | 0 |

| Procedural Sedation in the Community Emergency Department Registry (ProSCED) | Sacchetti, 2007 | 01-01-2003 to 04-03-2006 1 | USA | 14 | Procedural sedation | No funding acknowledged. | 1 |

| Singapore Head Injury Database 4 | Chong, 2015 | 01-2006 to 06-2014 1 | Singapore | 1 | Pediatric head injury | Pediatrics Academic Clinical Program, Singapore. | 0 |

| The Sepsis Registry 4 | Williams, 2011 | Not specified | Australia | 1 | Sepsis | Queensland Emergency Medicine Research Foundation. | 0 |

| VNICat (NIVCat in English) | Jacob, 2017 | 02-2015 to 03-2015 1 | Spain | 8 | Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | No funding acknowledged. | 1 |

3.3. Funding for Primary ED Registry Publications

3.4. Aims, Results and Conclusion in Primary ED Registry Publications with a General Scope

3.5. Aims, Results and Conclusion in Primary ED Registry Publications Specific for a Condition or Population

3.6. Aims, Results and Conclusion in Secondary Publications

4. Discussion

4.1. Emergency Department Registries Reported in the Literature

4.2. Emergency Department Registry Scope

4.3. Temporal Scope of Emergency Department Registries

4.4. Funding source for Emergency Department Registries

4.5. ED Registries as a Catalyst for Further Publications

4.6. ED Registries as a Catalyst for Quality –A Piece of the Learning Health System Puzzle?

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy

| Search Query | ||

|---|---|---|

| All databases | Full text available; English language | |

| PubMed | ((Emergency [Title]) AND (Registry [Title] OR Register[Title] OR Database[Title])) | |

| Embase | ((Emergency.ti.) AND (Registry.ti. OR Register.ti. OR Database.ti.)) | |

| Web of Science | (TI=(Emergency) AND (TI=(Registry) OR TI=(Register) OR TI=(Database))) |

References

- Trzeciak, S.; Rivers, E.P. Emergency department overcrowding in the United States: an emerging threat to patient safety and public health. Emerg Med J 2003, 20, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, V.; Barrington, G.; Page, S. The Tasmanian Emergency Care Outcomes Registry (TECOR) Protocol. Emerg Care Med 2024, 1, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.M.; Gardner, A.F.; Weiss, L.D.; Wood, J.P.; Ybarra, M.; Beck, D.M.; Stauffer, A.R.; Wilkerson, D.; Brabson, T.; Jennings, A.; et al. The future of emergency medicine. J Emerg Nurs 2010, 36, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprivulis, P.C.; Da Silva, J.-A.; Jacobs, I.G.; Frazer, A.R.L.; Jelinek, G.A. The association between hospital overcrowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments. MJA 2006, 184, 616–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlakhan, S.; Qayyum, H.; Burke, D.; Brown, R. The safety of emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2016, 33, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliklich, R.E.; Dreyer, N.A.; Leavy, M.B. AHRQ Methods for Effective Health Care. In Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User's Guide, Gliklich, R.E., Dreyer, N.A., Leavy, M.B., Eds.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville (MD), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S.M.; Scott, I.A.; Johnson, N.P.; Cameron, P.A.; McNeil, J.J. Development of clinical-quality registries in Australia: the way forward. Med J Aust 2011, 194, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secombe, P.; Millar, J.; Litton, E.; Chavan, S.; Hensman, T.; Hart, G.K.; Slater, A.; Herkes, R.; Huckson, S.; Pilcher, D.V. Thirty years of ANZICS CORE: A clinical quality success story. Crit Care Resusc 2023, 25, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Singer, Y.; Cleland, H.; Wood, F.; Cameron, P.; Tracy, L.M.; Gabbe, B.J. Driving improved burns care and patient outcomes through clinical registry data: A review of quality indicators in the Burns Registry of Australia and New Zealand. Burns 2021, 47, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission On Safety And Quality In Health Care. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/australian-framework-national-clinical-quality-registries-2024 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Australian Commission On Safety And Quality In Health Care. Australian Register of Clinical Registries. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/australian-register-clinical-registries (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- National Institutes of Health. List of Registries. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/health-information/nih-clinical-research-trials-you/list-registries (accessed on December 11, 2024).

- Etkin, C.D.; Springer, B.D. The American Joint Replacement Registry—the first 5 years. Arthroplasty Today 2017, 3, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bueno, M.; Pérez de la Sota, E.; Forteza Gil, A.; Ortiz-Berbel, D.; Castrodeza, J.; García-Cosío Carmena, M.D.; Barge-Caballero, E.; Rangel Sousa, D.; Díaz Molina, B.; Manrique Antón, R.; et al. Durable ventricular assist device in Spain (2007-2020). First report of the REGALAD registry. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2023, 76, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennergren, D.; Ekholm, C.; Sandelin, A.; Möller, M. The Swedish fracture register: 103,000 fractures registered. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadilhac, D.A.; Kim, J.; Lannin, N.A.; Kapral, M.K.; Schwamm, L.H.; Dennis, M.S.; Norrving, B.; Meretoja, A. National stroke registries for monitoring and improving the quality of hospital care: A systematic review. Int. J. Stroke 2015, 11, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, P.A.; Fitzgerald, M.C.; Curtis, K.; McKie, E.; Gabbe, B.; Earnest, A.; Christey, G.; Clarke, C.; Crozier, J.; Dinh, M.; et al. Over view of major traumatic injury in Australia––Implications for trauma system design. Injury 2020, 51, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, S.; O'Reilly, G.M.; Egerton-Warburton, D.; Jones, P.; Than, M.P.; Tran, V.; Taniar, D.; Moore, K.; Alvandi, A.; Tuxen-Vu, J.; et al. Making the most of what we have: What does the future hold for Emergency Department data? Emerg Med Australas 2024, 36, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O'Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Greenslade, J.H.; McKenzie, J.V.; Chu, K.H.; Brown, A.; Paterson, D.; Lipman, J. A prospective registry of emergency department patients admitted with infection. BMC Infect Dis 2011, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, A.; Ravi, S.; Rothenberg, C.; Kinsman, J.; Sun, J.; Goyal, P.; Augustine, J.; Epstein, S.K. Fair Play: Application of Normalized Scoring to Emergency Department Throughput Quality Measures in a National Registry. Ann Emerg Med 2021, 77, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oeveren, L.; Donner, J.; Fantegrossi, A.; Mohr, N.M.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Telemedicine-Assisted Intubation in Rural Emergency Departments: A National Emergency Airway Registry Study. Telemed J E Health 2017, 23, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, S.A.; Kaji, A.H.; Carlson, J.N.; McCormick, T.; Haukoos, J.S.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Video Laryngoscopy Is Associated With First-Pass Success in Emergency Department Intubations for Trauma Patients: A Propensity Score Matched Analysis of the National Emergency Airway Registry. Ann Emerg Med 2021, 78, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theron, L.; Jansen, K.; Miles, J. Benzylpiperizine-based party pills' impact on the Auckland City Hospital Emergency Department Overdose Database (2002-2004) compared with ecstasy (MDMA or methylene dioxymethamphetamine), gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB), amphetamines, cocaine, and alcohol. N Z Med J 2007, 120, U2416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stoecklein, H.H.; Kelly, C.; Kaji, A.H.; Fantegrossi, A.; Carlson, M.; Fix, M.L.; Madsen, T.; Walls, R.M.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Multicenter Comparison of Nonsupine Versus Supine Positioning During Intubation in the Emergency Department: A National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) Study. Acad Emerg Med 2019, 26, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandefur, B.J.; Liu, X.W.; Kaji, A.H.; Campbell, R.L.; Driver, B.E.; Walls, R.M.; Carlson, J.N.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Emergency Department Intubations in Patients With Angioedema: A Report from the National Emergency Airway Registry. J Emerg Med 2021, 61, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, A.; Senula, G.; Strickland, J.; Dubin, R. Procedural sedation in the community emergency department: initial results of the ProSCED registry. Acad Emerg Med 2007, 14, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, A.; Stander, E.; Ferguson, N.; Maniar, G.; Valko, P. Pediatric Procedural Sedation in the Community Emergency Department: results from the ProSCED registry. Pediatr Emerg Care 2007, 23, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, B.T.; Mali, M.; Kaji, A.H.; Kilgo, R.; Watts, S.; Wells, R.; Limkakeng, A.T.; Borawski, J.B.; Fantegrossi, A.E.; Walls, R.M.; et al. Direct vs Video Laryngoscopy for Difficult Airway Patients in the Emergency Department: A National Emergency Airway Registry Study. West J Emerg Med 2022, 23, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, C.V.; Schreiber, D.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Slattery, D.; Fanikos, J.; O'Neil, B.J.; Thompson, J.R.; Hiestand, B.; Briese, B.A.; Pendleton, R.C.; et al. Clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients diagnosed with acute pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: initial report of EMPEROR (Multicenter Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol 2011, 57, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, M.P.; Glauser, J.; Yuen, H.W.; Sturges-Smith, E.; Schrump, S.E. Airway registry: a performance improvement surveillance project of emergency department airway management. Am J Med Qual 2010, 25, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pediat Emergency Care Appl, R.; Davies, S.J.D.; Grundmeier, R.W.; Campos, D.A.; Hayes, K.L.; Bell, J.; Alessandrini, E.A.; Bajaj, L.; Chamberlain, J.M.; Gorelick, M.H.; et al. The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network Registry: A Multicentre Electronic Health Record Registry of Pediatric Emergency Care. Appl Clin Inform 2018, 9, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallin, D.J.; Dwyer, R.C.; Walls, R.M.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Techniques and Trends, Success Rates, and Adverse Events in Emergency Department Pediatric Intubations: A Report From the National Emergency Airway Registry. Ann Emerg Med 2016, 67, 610–615.e611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, R.; Blaschke, S.; Schirrmeister, W.; Drynda, S.; Walcher, F.; Greiner, F. Length of stay as quality indicator in emergency departments: analysis of determinants in the German Emergency Department Data Registry (AKTIN registry). Intern Emerg Med 2022, 17, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offenbacher, J.; Nikolla, D.A.; Carlson, J.N.; Smith, S.W.; Genes, N.; Boatright, D.H.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Incidence of rescue surgical airways after attempted orotracheal intubation in the emergency department: A National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) Study. Am J Emerg Med 2023, 68, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, G.M.; Mitchell, R.D.; Mitra, B.; Noonan, M.P.; Hiller, R.; Brichko, L.; Luckhoff, C.; Paton, A.; Smit, V.; Cameron, P.A. Impact of patient isolation on emergency department length of stay: A retrospective cohort study using the Registry for Emergency Care. Emerg Med Australas 2020, 32, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolla, D.A.; Offenbacher, J.; Smith, S.W.; Genes, N.G.; Herrera, O.A.; Carlson, J.N.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. First-Attempt Success Between Anatomically and Physiologically Difficult Airways in the National Emergency Airway Registry. Anesth Analg 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, Ò.; Martínez, G.; Masip, J.; Gil, V.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Llorens, P.; Herrero-Puente, P.; Sánchez, C.; Richard, F.; Lucas-Invernón, J.; et al. Effects on short term outcome of non-invasive ventilation use in the emergency department to treat patients with acute heart failure: A propensity score-based analysis of the EAHFE Registry. Eur J Intern Med 2018, 53, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, Ò.; Llorens, P.; Freund, Y.; Davison, B.; Takagi, K.; Herrero-Puente, P.; Jacob, J.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Gil, V.; Rosselló, X.; et al. Early intravenous nitroglycerin use in prehospital setting and in the emergency department to treat patients with acute heart failure: Insights from the EAHFE Spanish registry. Int J Cardiol 2021, 344, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, J.; Escandon, M.; Tapia, A.D.; Davis, W.T.; April, M.D.; Maddry, J.K.; Couperus, K.; Hu, J.S.; Chin, E.; Schauer, S.G. Development of the Defense Registry for Emergency Airway Management (DREAM). Med J (Ft Sam Houst Tex) 2021, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- McCain, J.E.; Bridgmon, A.E.; King, W.D.; Monroe, K. Children's injury database: development of an injury surveillance system in a pediatric emergency department. Inj Epidemiol 2023, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, P.; Escoda, R.; Miró, Ò.; Herrero-Puente, P.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Jacob, J.; Garrido, J.M.; Pérez-Durá, M.J.; Gil, C.; Fuentes, M.; et al. Characteristics and clinical course of patients with acute heart failure and the therapeutic measures applied in Spanish emergency departments: based on the EAHFE registry (Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments). Emergencias 2015, 27, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.W.; Schreiber, D.H.; Liu, G.; Briese, B.; Hiestand, B.; Slattery, D.; Kline, J.A.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Pollack, C.V. Therapy and outcomes in massive pulmonary embolism from the Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry. Am J Emerg Med 2012, 30, 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lembersky, O.; Golz, D.; Kramer, C.; Fantegrossi, A.; Carlson, J.N.; Walls, R.M.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Factors associated with post-intubation sedation after emergency department intubation: A Report from The National Emergency Airway Registry. Am J Emerg Med 2020, 38, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, A.T.; Jørgensen, H.; Jørsboe, H.B.; Odby, A.; Brabrand, M.; Steinmetz, J.; Mackenhauer, J.; Kirkegaard, H.; Christiansen, C.F. The Danish database for acute and emergency hospital contacts. Clin Epidemiol 2016, 8, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzler, N.M.; Cole, J.B.; Driver, B.E.; Carlson, J.; April, M.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Risk of peri-intubation adverse events during emergency department intubation of overdose patients: a national emergency airway registry (near) analysis. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2022, 60, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, S.; You, J.S.; Choi, H.J.; Chung, H.S. The clinical effectiveness of simulation based airway management education using the Korean emergency airway registry. Signa Vitae 2017, 13, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.A.; El-Setouhy, M.; Hirshon, J.M.; El-Shinawi, M. Developing a trauma registry for the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in Egypt: a step toward success. Egypt J Surg 2021, 40, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisler, M.C.; Hyde, R.J.; Sandefur, B.J.; Kaji, A.H.; Campbell, R.L.; Driver, B.E.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Awake intubations in the emergency department: A report from the National Emergency Airway Registry. Am J Emerg Med 2021, 49, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, S.; Ruiz-Artacho, P.; Merlo, M.; Suero, C.; Antolin, A.; Casal, J.R.; Sanchez, M.; Ortega-Duarte, A.; Genis, M.; Piñera, P. Risk profile, management, and outcomes of patients with venous thromboembolism attended in Spanish Emergency Departments: The ESPHERIA registry. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96, e8796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Kong, S.Y.; Shin, S.D.; Ro, Y.S.; Wi, D.H.; Kim, S.C.; Sun, K.M.; Kim, S.; Kang, S.B.; et al. Monitoring of characteristics of the patients visiting an emergency center in Cameroon through the development of hospital patient database. Afr J Emerg Med 2022, 12, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Cabello, I.; Yuguero, O.; Alexis Guzmán, J.; Arranz Betegón, M.; Abadías, M.J.; Francés Artigas, P.; Santos, J.; Esquerrà, A.; Mòdol, J.M. Emergency Atrial Fibrillation Registry of the Catalan Institute of Health (URGFAICS): analysis by type of atrial fibrillation and revisits within 30 days. Emergencias 2019, 31, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hart, J.C.; Goldstein, L.N. Analysis of the airway registry from an academic emergency department in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2020, 110, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.; Schultz, T.; Crock, C.; Deakin, A.; Runciman, W.; Gosbell, A. The Emergency Medicine Events Register: An analysis of the first 150 incidents entered into a novel, online incident reporting registry. Emerg Med Australas 2016, 28, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grp, A.; Alonso, C.F.; Avilés, R.A.; López, M.L.; Martínez, F.G.; Ferrer, M.F.; Bañeres, B.G.; Najera, D.; Loaiza, J.E.G.; García, L.B.Z.; et al. Differences in emergency department care of adults with a first epileptic seizure versus a recurrent seizure: a study of the ACESUR (Acute Epileptic Seizures in the Emergency Department) registry. Emergencias 2019, 31, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, S.I.; Sandefur, B.J.; Campbell, R.L.; Driver, B.E.; April, M.D.; Carlson, J.N.; Walls, R.M.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. First-Attempt Intubation Success Among Emergency Medicine Trainees by Laryngoscopic Device and Training Year: A National Emergency Airway Registry Study. Ann Emerg Med 2023, 81, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, T.; Alkhouri, H.; Vassiliadis, J. The Royal North Shore Hospital Emergency Department airway registry: Closing the audit loop. Emerg Med Australas 2016, 28, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, I.; Alkhouri, H.; Fogg, T.; Aneman, A. Ketamine use for rapid sequence intubation in Australian and New Zealand emergency departments from 2010 to 2015: A registry study. Emerg Med Australas 2019, 31, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.L.; Barbier, S.; Liu, N.; Ong, G.Y.; Ng, K.C.; Ong, M.E. Predictors for moderate to severe paediatric head injury derived from a surveillance registry in the emergency department. Injury 2015, 46, 1270–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Je, S.M.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, E. The factors associated with successful paediatric endotracheal intubation on the first attempt in emergency departments: a 13-emergency-department registry study. Resuscitation 2012, 83, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Park, J.W.; Kwak, Y.H.; Kim, D.K.; Jung, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, J.H.; Suh, D.; Lee, H.N.; Lee, E.J.; et al. Comparison of age-adjusted shock indices as predictors of injury severity in paediatric trauma patients immediately after emergency department triage: A report from the Korean multicentre registry. Injury 2024, 55, 111108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Cho, Y.S.; You, J.S.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, H.; Chung, H.S. Current status of emergency airway management for elderly patients in Korea: Multicentre study using the Korean Emergency Airway Management Registry. Emerg Med Australas 2013, 25, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, G.W.H.; Chai, C.Y.; Teo, J.S.Y.; Tjio, C.K.E.; Chua, M.T.; Brown, I.C. Emergency airway management in a Singapore centre: A registry study. Ann Acad Med Singap 2021, 50, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carriel Mancilla, J.; Jiménez Hernández, S.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Jiménez, D.; Fuentes Ferrer, M.; Ruiz-Artacho, P. Clinical characteristics and course in emergency department patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and symptomatic acute venous thromboembolic disease: secondary analysis of the ESPHERIA registry. Emergencias 2020, 32, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carriel Mancilla, J.; Jiménez Hernández, S.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Jiménez, D.; Lecumberri, R.; Alonso Valle, H.; Beddar Chaib, F.; Ruiz-Artacho, P. Profiles of patients with venous thromboembolic disease in the emergency department and their medium-term prognosis: data from the ESPHERIA registry. Emergencias 2021, 33, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, I.; Jacob, J.; Arranz, M.; Yuguero, O.; Guzman, J.; Moreno-Pena, A.; Frances, P.; Santos, J.; Esquerrà, A.; Mòdol, J.M. Impact of emergency department management of atrial fibrillation with amiodarone on length of stay. A propensity score analysis based on the URGFAICS registry. Eur J Emerg Med 2020, 27, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.A., 3rd; Kaji, A.H.; Fantegrossi, A.; Carlson, J.N.; April, M.D.; Kilgo, R.W.; Walls, R.M. Video Laryngoscopy Compared to Augmented Direct Laryngoscopy in Adult Emergency Department Tracheal Intubations: A National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) Study. Acad Emerg Med 2020, 27, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, S.; Da Dalt, L.; Chamorro, M.; Abarca, R.; Azzolina, D.; Gregori, D.; Sereni, F.; Montini, G.; Tognoni, G. Paediatric emergencies and related mortality in Nicaragua: results from a multi-site paediatric emergency registry. Emerg Med J 2021, 38, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.; Alkhouri, H.; Badge, H.; Long, E.; Chan, T.; Vassiliadis, J.; Fogg, T. Bed tilt and ramp positions are associated with increased first-pass success of adult endotracheal intubation in the emergency department: A registry study. Emerg Med Australas 2023, 35, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, O.; Cooper-Brown, L.A.; Lubov, J.; Allali, G.; Afilalo, M.; Launay, C.P. “Emergency Room Evaluation and Recommendations” (ER2) Tool for the Screening of Older Emergency Department Visitors With Major Neurocognitive Disorders: Results From the ER2 Database. Front Neurol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barfod, C.; Lauritzen, M.M.; Danker, J.K.; Sölétormos, G.; Berlac, P.A.; Lippert, F.; Lundstrøm, L.H.; Antonsen, K.; Lange, K.H. The formation and design of the 'Acute Admission Database'- a database including a prospective, observational cohort of 6279 patients triaged in the emergency department in a larger Danish hospital. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2012, 20, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balls, A.; LoVecchio, F.; Kroeger, A.; Stapczynski, J.S.; Mulrow, M.; Drachman, D. Ultrasound guidance for central venous catheter placement: results from the Central Line Emergency Access Registry Database. Am J Emerg Med 2010, 28, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arranz, M.; Jacob, J.; Sancho-Ramoneda, M.; Lopez, À.; Navarro-Sáez, M.C.; Cousiño-Chao, J.R.; López-Altimiras, X.; López, I.V.F.; García-Trallero, O.; German, A.; et al. Characteristics of prolonged noninvasive ventilation in emergency departments and impact upon effectiveness. Analysis of the VNICat registry. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed) 2021, 45, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- April, M.D.; Schauer, S.G.; Brown Rd, C.A.; Ng, P.C.; Fernandez, J.; Fantegrossi, A.E.; Maddry, J.K.; Summers, S.; Sessions, D.J.; Barnwell, R.M.; et al. A 12-month descriptive analysis of emergency intubations at Brooke Army Medical Center: a National Emergency Airway Registry study. US Army Med Dep J 2017, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- April, M.D.; Driver, B.; Schauer, S.G.; Carlson, J.N.; Bridwell, R.E.; Long, B.; Stang, J.; Farah, S.; De Lorenzo, R.A.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Extraglottic device use is rare during emergency airway management: A National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) study. Am J Emerg Med 2023, 72, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- April, M.D.; Arana, A.; Schauer, S.G.; Davis, W.T.; Oliver, J.J.; Fantegrossi, A.; Summers, S.M.; Maddry, J.K.; Walls, R.M.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Ketamine Versus Etomidate and Peri-intubation Hypotension: A National Emergency Airway Registry Study. Acad Emerg Med 2020, 27, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- April, M.D.; Arana, A.; Reynolds, J.C.; Carlson, J.N.; Davis, W.T.; Schauer, S.G.; Oliver, J.J.; Summers, S.M.; Long, B.; Walls, R.M.; et al. Peri-intubation cardiac arrest in the Emergency Department: A National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) study. Resuscitation 2021, 162, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- April, M.D.; Arana, A.; Pallin, D.J.; Schauer, S.G.; Fantegrossi, A.; Fernandez, J.; Maddry, J.K.; Summers, S.M.; Antonacci, M.A.; Brown, C.A., 3rd. Emergency Department Intubation Success With Succinylcholine Versus Rocuronium: A National Emergency Airway Registry Study. Ann Emerg Med 2018, 72, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouri, H.; Richards, C.; Miers, J.; Fogg, T.; McCarthy, S. Case series and review of emergency front-of-neck surgical airways from The Australian and New Zealand Emergency Department Airway Registry. EMA 2021, 33, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Af Ugglas, B.; Lindmarker, P.; Ekelund, U.; Djärv, T.; Holzmann, M.J. Emergency department crowding and mortality in 14 Swedish emergency departments, a cohort study leveraging the Swedish Emergency Registry (SVAR). PLoS One 2021, 16, e0247881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouri, H.; Vassiliadis, J.; Murray, M.; Mackenzie, J.; Tzannes, A.; McCarthy, S.; Fogg, T. Emergency airway management in Australian and New Zealand emergency departments: A multicentre descriptive study of 3710 emergency intubations. EMA 2017, 29, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, I.; Rashan, S.; Sigera, C.; Salluh, J.; Dondorp, A.M.; Haniffa, R.; Beane, A. A scoping review of registry captured indicators for evaluating quality of critical care in ICU. J Intensive Care 2021, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Commission On Safety And Quality In Health Care. Economic evaluation of clinical quality registries, Final report. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/Economic-evaluation-of-clinical-quality-registries-Final-report-Nov-2016.

- Lee, P.; Chin, K.; Liew, D.; Stub, D.; Brennan, A.L.; Lefkovits, J.; Zomer, E. Economic evaluation of clinical quality registries: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.S.; Davey, T.M.; Mok, M.T.; McClure, R.J.; Farrow, N.C.; Gruen, R.L.; Pollard, C.W. Standardising trauma monitoring: the development of a minimum dataset for trauma registries in Australia and New Zealand. Injury 2013, 44, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary; Olsen, L., Aisner, D., McGinnis, J.M., Eds.; National Academies Press (US) Copyright © 2007, National Academy of Sciences.: Washington (DC), 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pomare, C.; Mahmoud, Z.; Vedovi, A.; Ellis, L.A.; Knaggs, G.; Smith, C.L.; Zurynski, Y.; Braithwaite, J. Learning health systems: A review of key topic areas and bibliometric trends. LHS 2022, 6, e10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-clinical-registry (accessed on 5 March 2025).

| Category | Scope | Clinical quality registry example |

|---|---|---|

| Procedure, device or drug | Joint replacement | The American Joint Replacement Registry [13] |

| Ventricular Assisted Device | The Spanish Registry of durable ventricular assist devices [14] | |

| Disease or illness | Hip fracture | The Swedish Fracture Register [15] |

| Stroke | The Australian Stroke Clinical Registry [16] | |

| Specific healthcare resource | Trauma | The Australian Trauma Registry [17] |

| Intensive Care | The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Centre for Outcomes and Resources Evaluation [8] |

| Registry | Aim | Results | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Admission Database | Barford, 2012 | The objective of this article is to 1) describe the formation and design of the ‘Acute Admission Database’ and 2) characterize the cohort included. | In primary triage, patients were categorized as red (4.4%), orange (25.2%), yellow (38.7%) and green (31.7%). Abnormal vital signs were present at admission in 25% of the patients, most often temperature (10.5%), saturation of peripheral oxygen (9.2%), Glasgow Coma Score (6.6%) and respiratory rate (4.8%). A venous acid-base status was obtained in 43% of all patients. The majority (78%) had a pH within the normal range (7.35-7.45), 15% had acidosis (pH < 7.35) and 7% had alkalosis (pH > 7.45). Median length of stay was 2 days (range 1-123). The proportion of patients admitted to Intensive Care Unit was 1.6% (95% CI 1.2-2.0), 1.8% (95% CI 1.5-2.2) died within 7 days, and 4.2% (95% CI 3.7-4.7) died within 28 days after admission. | Despite challenges of data registration, we succeeded in creating a database of adequate size and data quality. Future studies will focus on the association between patient status at admission and patient outcome, e.g. admission to Intensive Care Unit or in-hospital mortality. |

| American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Emergency Data Registry (CEDR) | Venkatesh, 2021 | To develop a volume-adjusted ED throughput quality measure to balance variation at the ED group level. | We found marked differences in the classification of ED throughput performance between scoring approaches. The weighted standardized score (z score) approach resulted in the least skewed and most uniform distribution across the majority of ED types, with a kurtosis of 12.91 for taxpayer identification numbers composed of 1 ED, 2.58 for those with multiple EDs without any supercenter, and 3.56 for those with multiple EDs with at least 1 supercenter, all lower than comparable scoring methods. The plurality and simple average scoring approaches appeared to disproportionally penalize ED groups that staff a single ED or multiple large-volume EDs. | Application of a weighted standardized (z score) approach to ED throughput measurement resulted in a more balanced variation between different ED group types and reduced distortions in the length-of-stay measurement among ED groups staffing high-volume EDs. This approach may be a more accurate and acceptable method of profiling ED group throughput pay-for-performance programs. |

| Centre des Urgences de Yaoundé (CURY) 4 | Jeong, 2022 | This paper describes the methods of CURY patient data collection and the characteristics of the patients visited CURY from January 2016 to June 2018. | During the study period, a total of 18,875 patients’ data were collected (44.5% women, median age of 36). Of the total patients, 2.4% had chest pain, 2.7% had stroke, 1.9% had sepsis/septic shock, and 1.6% had multiple trauma. About 6.0% patients received operation and majority of patients were discharged either normally (48.2%) or with continuity of care (26.3%). About 5.0% of patients were transferred to other hospital and 5.2% of patients were dead. | This study serves to broaden understanding of the emergency patients in Yaoundé, Cameroon. The hospital patient database for emergency patients can be further used as a basis for providing improved quality of medical care and effective communication tool among the medical staffs. |

| Danish Database for Acute and Emergency Hospital Contacts (DDAEHC) | Lassen, 2016 | The aim of the Danish database for acute and emergency hospital contacts (DDAEHC) is to monitor the quality of care for all unplanned hospital contacts in Denmark (acute and emergency contacts). | The DDAEHC also includes age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index conditions, civil status, residency, and discharge diagnoses. The DDAEHC expects to include 1.7 million acute and emergency contacts per year. | The DDAEHC is a new database established by the Danish Regions including all acute and emergency hospital contacts in Denmark. The database includes specific outcome and process health care quality indicators as well as demographic and other basic information with the purpose to be used for enhancement of quality of acute care. |

| Swedish Emergency Registry (SVAR) | Ekelund, 2011 | To assess the feasibility of collecting selected quality of care data from six different Swedish EDs using automated data capture as a basis for a national quality of care registry, and to present some first results regarding throughput times and patient presentation times. | All EDs provided throughput times and patient presentation data without significant problems. In all EDs, Monday was the busiest day and the fewest patients presented on Saturday. All EDs had a large increase in patient inflow before noon with a slow decline over the rest of the 24 h, and this peak and decline was especially pronounced in elderly patients. The average LOS was 4 h of which 2 h was spent waiting for the first physician. These throughput times showed a considerable diurnal variation in all EDs, with the longest times occurring 6-7am and in the late afternoon. | These results demonstrate the feasibility of collecting benchmarking data on quality of care targets within Swedish EM, and form the basis for ANSWER, A National SWedish Emergency Registry. |

| The Registry for Emergency Care | O’Reilly, 2020 | The first objective of the REC Project is to determine the impact of patient isolation and IPC processes on ED length of stay for adult patients. | Clinical tools will be generated to inform emergency care, both during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. | The REC Project will support ED clinicians in the emergency care of all patients. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).