Submitted:

15 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

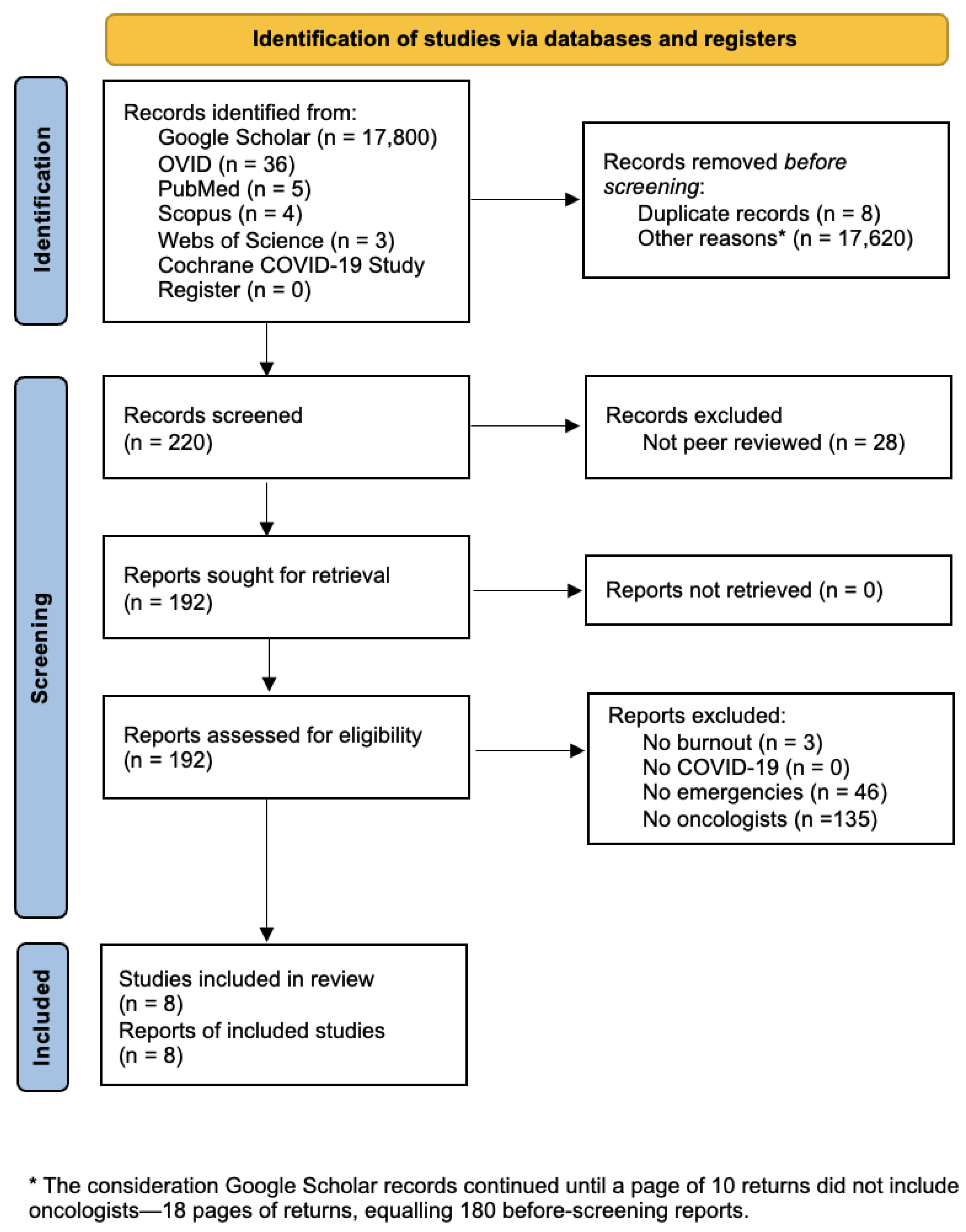

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Emergency Experienced

3.2. Burnout Response

3.3. Patient Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parmensis 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigby, J.; Satija, B. WHO Declares End to COVID Global Health Emergency. Reuters 2023.

- Nash, C. Burnout in Medical Specialists Redeployed to Emergency Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emergency Care and Medicine 2024, 1, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, K.; Banerjee, S. Burnout in Oncologists Is a Serious Issue: What Can We Do about It? Cancer Treatment Reviews 2018, 68, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, M.; Samuel, V. Burnout in Oncologists and Associated Factors: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care 2019, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, D.; Kunstár, O.; Kovács, A.; Petőné Csima, M. Burnout among Oncologists, Nurses, and Radiographers Working in Oncology Patient Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Radiography 2023, 29, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granek, L.; Nakash, O. Oncology Healthcare Professionals’ Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Current Oncology 2022, 29, 4054–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlubocky, F.J.; Back, A.L.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Gallagher, C.M.; Burke, J.M.; Kamal, A.H.; Paice, J.A.; Page, R.D.; Spence, R.; McGinnis, M.; et al. Occupational and Personal Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on US Oncologist Burnout and Well-Being: A Study From the ASCO Clinician Well-Being Task Force. JCO Oncology Practice 2021, 17, e427–e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlubocky, F.J.; Symington, B.E.; McFarland, D.C.; Gallagher, C.M.; Dragnev, K.H.; Burke, J.M.; Lee, R.T.; El-Jawahri, A.; Popp, B.; Rosenberg, A.R.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Oncologist Burnout, Emotional Well-Being, and Moral Distress: Considerations for the Cancer Organization’s Response for Readiness, Mitigation, and Resilience. JCO Oncology Practice 2021, 17, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Labaig, P.; Pacheco-Barcia, V.; Cebrià, A.; Gálvez, F.; Obispo, B.; Páez, D.; Quílez, A.; Quintanar, T.; Ramchandani, A.; Remon, J.; et al. Identifying and Preventing Burnout in Young Oncologists, an Overwhelming Challenge in the COVID-19 Era: A Study of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM). ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budisavljevic, A.; Kelemenic-Drazin, R.; Silovski, T.; Plestina, S.; Plavetic, N.D. Correlation between Psychological Resilience and Burnout Syndrome in Oncologists amid the Covid-19 Pandemic. Support Care Cancer 2023, 31, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.E.; Chisnall, G.; Vindrola-Padros, C. A Systematic Review of De-Escalation Strategies for Redeployed Staff and Repurposed Facilities in COVID-19 Intensive Care Units (ICUs) during the Pandemic. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 44, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alom, S.; Chiu, C.M.; Jha, A.; Lai, S.H.D.; Yau, T.H.L.; Harky, A. The Effects of COVID-19 on Cancer Care Provision: A Systematic Review. Cancer Control 2021, 28, 1073274821997425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powis, M.; Milley-Daigle, C.; Hack, S.; Alibhai, S.; Singh, S.; Krzyzanowska, M.K. Impact of the Early Phase of the COVID Pandemic on Cancer Treatment Delivery and the Quality of Cancer Care: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Model. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2021, 33, mzab088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, V.K.; Chavez, M.; Mason, T.M.; Martinez-Tyson, D. Emergency Preparedness during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Perceptions of Oncology Professionals and Implications for Nursing Management from a Qualitative Study. J Nurs Manag 2021, 29, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischof, J.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Creditt, A.B.; Wattana, M.K.; Pettit, N.R. The Current State of Acute Oncology Training for Emergency Physicians: A Narrative Review. Emerg Cancer Care 2022, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould Rothberg, B.E.; Quest, T.E.; Yeung, S.J.; Pelosof, L.C.; Gerber, D.E.; Seltzer, J.A.; Bischof, J.J.; Thomas, C.R.; Akhter, N.; Mamtani, M.; et al. Oncologic Emergencies and Urgencies: A Comprehensive Review. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 2022, 72, 570–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gri, N.; Longhitano, Y.; Zanza, C.; Monticone, V.; Fuschi, D.; Piccioni, A.; Bellou, A.; Esposito, C.; Ceresa, I.F.; Savioli, G. Acute Oncologic Complications: Clinical–Therapeutic Management in Critical Care and Emergency Departments. Current Oncology 2023, 30, 7315–7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugel, M.; Carlier, C.; Essner, C.; Debreuve-Theresette, A.; Beck, M.-F.; Merrouche, Y.; Bouché, O. Dramatic Changes in Oncology Care Pathways During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The French ONCOCARE-COV Study. The Oncologist 2021, 26, e338–e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Mousavi-Roknabadi, R.S. Burnout among Healthcare Providers of COVID-19; a Systematic Review of Epidemiology and Recommendations : Burnout in Healthcare Providers. Archives of Academic Emergency Medicine 2020, 9, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff Burn-Out. Journal of Social Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Burn-out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases 2019.

- Tabur, A.; Elkefi, S.; Emhan, A.; Mengenci, C.; Bez, Y.; Asan, O. Anxiety, Burnout and Depression, Psychological Well-Being as Predictor of Healthcare Professionals’ Turnover during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Study in a Pandemic Hospital. Healthcare 2022, 10, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8261-4191-0. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Research Synthesis Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M. Google Scholar to Overshadow Them All? Comparing the Sizes of 12 Academic Search Engines and Bibliographic Databases. Scientometrics 2019, 118, 177–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzendorf, M.; Featherstone, R.M. Evaluation of the Comprehensiveness, Accuracy and Currency of the Cochrane COVID -19 Study Register for Supporting Rapid Evidence Synthesis Production. Research Synthesis Methods 2021, 12, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemilt, I.; Noel-Storr, A.; Thomas, J.; Featherstone, R.; Mavergames, C. Machine Learning Reduced Workload for the Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register: Development and Evaluation of the Cochrane COVID-19 Study Classifier. Syst Rev 2022, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloconi, C.; Economou, M.; Charalambous, A. Burnout, Coping and Resilience of the Cancer Care Workforce during the SARS-CoV-2: A Multinational Cross-Sectional Study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2023, 63, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeklé, H.; Ladrat, L.; Landrin, T.; Beuzeboc, P.; Hervé, C. Bio-ethical Issues in Oncology during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Qualitative Study in a French Hospital. Evaluation Clinical Practice 2023, 29, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, E.; Pasanen, L.; LeGautier, R.; McLachlan, S.; Collins, A.; Philip, J. The Role of Telehealth in Oncology Care: A Qualitative Exploration of Patient and Clinician Perspectives. European J Cancer Care 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykers, K.; Tacey, M.; Bowes, J.; Brown, K.; Yuen, E.; Wilson, C.; Khor, R.; Foroudi, F. Victoria (Australia) Radiotherapy Response to Working through the First and Second Wave of COVID-19: Strategies and Staffing. J Med Imag Rad Onc 2021, 65, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melidis, C.; Vantsos, M. [Comment] Ethical and Practical Considerations on Cancer Recommendations during COVID-19 Pandemic. mol clin onc 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, D.; Kunstár, O.; Kovács, A.; Petőné Csima, M. Burnout among Oncologists, Nurses, and Radiographers Working in Oncology Patient Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Radiography 2023, 29, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.; Yang, V.; Han, S.; Zhuang, Q.; Zhou, S.; Mathur, S.; Kang, M.L.; Ngeow, J.; Yap, S.P.; Tham, C.K. Oncology Workload in a Tertiary Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare 2022, 31, 201010582110511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballatore, Z.; Bastianelli, L.; Merloni, F.; Ranallo, N.; Cantini, L.; Marcantognini, G.; Berardi, R. Scientia Potentia Est: How the Italian World of Oncology Changes in the COVID-19 Pandemic. JCO Global Oncology 2020, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Natale, G.; Ricciardi, V.; De Luca, G.; De Natale, D.; Di Meglio, G.; Ferragamo, A.; Marchitelli, V.; Piccolo, A.; Scala, A.; Somma, R.; et al. The COVID-19 Infection in Italy: A Statistical Study of an Abnormally Severe Disease. JCM 2020, 9, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowicz-Szlarska, E.; Forycka, J.; Harendarz, K.; Stanisławska, M.; Makówka, A.; Nowicki, M. Organizational Support, Training and Equipment Are Key Determinants of Burnout among Dialysis Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Nephrol 2022, 35, 2077–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.; Brereton, L.; Hoge, C.; Plantinga, L.C.; Agrawal, V.; Soman, S.S.; Choi, M.J.; Jaar, B.G.; Soman, S.; Jaar, B.; et al. Burnout Among Nephrologists in the United States: A Survey Study. Kidney Medicine 2022, 4, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, D.; DeCara, J.M.; Herrmann, J.; Arnold, A.; Ghosh, A.K.; Abdel-Qadir, H.; Yang, E.H.; Szmit, S.; Akhter, N.; Leja, M.; et al. Perspectives on the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Cardio-Oncology: Results from the COVID-19 International Collaborative Network Survey. Cardio-Oncology 2020, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, M.F.; Kimball, A.B.; Butt, M.; Stuckey, H.; Costigan, H.; Shinkai, K.; Nagler, A.R. Challenges for Dermatologists during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology 2022, 8, e013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.-J. Psychosocio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Practice. Gastroenterology Report 2021, 9, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellowlees, P. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Care Practitioners. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2022, 45, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlubocky, F.J.; Symington, B.E.; McFarland, D.C.; Gallagher, C.M.; Dragnev, K.H.; Burke, J.M.; Lee, R.T.; El-Jawahri, A.; Popp, B.; Rosenberg, A.R.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Oncologist Burnout, Emotional Well-Being, and Moral Distress: Considerations for the Cancer Organization’s Response for Readiness, Mitigation, and Resilience. JCO Oncology Practice 2021, 17, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlubocky, F.J.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Back, A.L.; Paice, J.A.; Tetzlaff, E.D.; Friese, C.R.; Kamal, A.H.; McFarland, D.C.; Lyckholm, L.; Gallagher, C.M.; et al. Creating a Blueprint of Well-Being in Oncology: An Approach for Addressing Burnout From ASCO’s Clinician Well-Being Taskforce. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2021, e339–e353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadi, M.; Msherghi, A.; Elgzairi, M.; Alhashimi, A.; Bouhuwaish, A.; Biala, M.; Abuelmeda, S.; Khel, S.; Khaled, A.; Alsoufi, A.; et al. Burnout Syndrome Among Hospital Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Civil War: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 579563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, E.S.; Winsvold, B.S.; Sandset, E.C.; Storstein, A.M.; Faiz, K.W. Experiences, Distress and Burden among Neurologists in Norway during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.G.; Walls, R.M. Supporting the Health Care Workforce During the COVID-19 Global Epidemic. JAMA 2020, 323, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwigson, A.; Huynh, V.; Myers, S.; Hampanda, K.; Christian, N.; Ahrendt, G.; Romandetti, K.; Tevis, S. Patient Perceptions of Changes in Breast Cancer Care and Well-Being During COVID-19: A Mixed Methods Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2022, 29, 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.; Heinert, S.; Sanchez, L.; Karasz, A.; Ramos, M.E.; Sarkar, S.; Rapkin, B.; In, H. A Qualitative Analysis of Patients’ Experiences with an Emergency Department Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Academic Emergency Medicine 2023, 30, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotlib Conn, L.; Tahmasebi, H.; Meti, N.; Wright, F.C.; Thawer, A.; Cheung, M.; Singh, S. Cancer Treatment During COVID-19: A Qualitative Analysis of Patient-Perceived Risks and Experiences with Virtual Care. Journal of Patient Experience 2021, 8, 23743735211039328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbia, V.; Bordonaro, R.; Blasi, L.; Piazza, D.; Pellegrino, A.; Iacono, C.; Spada, M.; Tralongo, P.; Firenze, A. Liability of Clinical Oncologists and the COVID-19 Emergency: Between Hopes and Concerns. Journal of Cancer Policy 2020, 25, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barranco, R.; Messina, C.; Bonsignore, A.; Cattrini, C.; Ventura, F. Medical Liability in Cancer Care During COVID-19 Pandemic: Heroes or Guilty? Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 602988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, B.E.; Cangemi, D.J.; Burke, C.A. Burnout in Gastrointestinal Providers. Am J Gastroenterol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buran, F.; Altın, Z. Burnout among Physicians Working in a Pandemic Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Legal Medicine 2021, 51, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.J.; Dubey, M.; Hall, J.A.; Catzen, H.Z.; Blanch-Hartigan, D.; Schwartz, R. What Is Empathy? Oncology Patient Perspectives on Empathic Clinician Behaviors. Cancer 2021, 127, 4258–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogenis, A.F.; Scarlat, M.M. Stress, Anxiety, and Burnout of Orthopaedic Surgeons in COVID-19 Pandemic. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 2022, 46, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macía-Rodríguez, C.; Alejandre De Oña, Á.; Martín-Iglesias, D.; Barrera-López, L.; Pérez-Sanz, M.T.; Moreno-Diaz, J.; González-Munera, A. Burn-out Syndrome in Spanish Internists during the COVID-19 Outbreak and Associated Factors: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaskandan, H.; Nimmo, A.; Savino, M.; Afuwape, S.; Brand, S.; Graham-Brown, M.; Medcalf, J.; Cockwell, P.; Beckwith, H. Burnout and Long COVID among the UK Nephrology Workforce: Results from a National Survey Investigating the Impact of COVID-19 on Working Lives. Clinical Kidney Journal 2022, 15, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Piccolo, L.; Donisi, V.; Raffaelli, R.; Garzon, S.; Perlini, C.; Rimondini, M.; Uccella, S.; Cromi, A.; Ghezzi, F.; Ginami, M.; et al. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Providers in Obstetrics: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 632999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, E.L.; Poore, S.O. Slowing the Spread and Minimizing the Impact of COVID-19: Lessons from the Past and Recommendations for the Plastic Surgeon. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 2020, 146, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A.; Duncan, A.A. Systematic and Scoping Reviews: A Comparison and Overview. Seminars in Vascular Surgery 2022, 35, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Pollock, D.; Khalil, H.; Alexander, L.; Mclnerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Peters, M.; Tricco, A.C. What Are Scoping Reviews? Providing a Formal Definition of Scoping Reviews as a Type of Evidence Synthesis. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2022, 20, 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Peters, M.Dj.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Munn, Z. Conducting High Quality Scoping Reviews-Challenges and Solutions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2021, 130, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best Practice Guidance and Reporting Items for the Development of Scoping Review Protocols. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poerwandari, E.K. Minimizing Bias and Maximizing the Potential Strengths of Autoethnography as a Narrative Research. Jpn Psychol Res 2021, 63, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, T.M.S.; Lienert, P.; Denne, E.; Singh, J.P. A General Model of Cognitive Bias in Human Judgment and Systematic Review Specific to Forensic Mental Health. Law and Human Behavior 2022, 46, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed Shaffril, H.A.; Samsuddin, S.F.; Abu Samah, A. The ABC of Systematic Literature Review: The Basic Methodological Guidance for Beginners. Qual Quant 2021, 55, 1319–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B.; Ghezzi-Kopel, K.; Hoddinott, J.; Homami, N.; Tennant, E.; Upton, J.; Wu, T. A Scoping Review of the Development Resilience Literature: Theory, Methods and Evidence. World Development 2021, 146, 105612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citation # | Report Title | Database | Year |

| [31] | Burnout, coping and resilience of the cancer care workforce during the SARS-CoV-2: A multinational cross-sectional study | PubMed | 2023 |

| [32] | Bio-ethical issues in oncology during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic: A qualitative study in a French hospital | OVID | 2023 |

| [33] | The role of telehealth in oncology care: A qualitative exploration of patient and clinician perspectives | OVID | 2022 |

| [34] | Victoria (Australia) radiotherapy response to working through the first and second wave of COVID-19: Strategies and staffing | OVID | 2021 |

| [35] | [Comment] Ethical and practical considerations on cancer recommendations during COVID-19 pandemic | OVID | 2020 |

| [36] | Burnout among oncologists, nurses, and radiographers working in oncology patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Radiography | Google Scholar | 2023 |

| [37] | Oncology workload in a tertiary hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic | Google Scholar | 2022 |

| [38] | Scientia potentia est: how the Italian world of oncology changes in the COVID-19 pandemic | Google Scholar | 2020 |

| # | Emergency Experienced | Burnout Response | Patient Outcome |

| [31] | Delay of critical surgeries, suspension or reduction of chemotherapy treatments and change of chemotherapy regimens, increased workload | There were increased levels of burnout, posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression, 35% of oncologists raising to 49% at follow up | 66% of oncologists reported an inability to perform their job effectively for patients in comparison with pre-COVID-19 |

| [32] | Patients have high COVID-19-associated mortality rates and decreased survival | Increased concern for patients is viewed as part of the increase in burnout | Prohibition of infected patient family visits implicated in increasing patient mortality |

| [33] | Inability to meet with patients in person, telehealth required for meetings | Experienced ethical distress over their poor performances in breaking bad news on telehealth | Faced decreased intimacy and familiarity previously formed from care pre-COVID-19 |

| [34] | Remote working strategies expanded, and additional telehealth supports were quickly adopted | Over half of the respondents indicated that they often or always felt worn out at the end of the working day | Contact of 90% of new and returning patient clinic reviews was by Internet video or telephone |

| [35] | Reduced number of treatment sessions than initially presented to patients with distinctions based on age criteria and level of emergency | More stressful working conditions than usual, resulting in augmented fatigue and less patience—additional accidents a possibility | Distressed cancer patients—feel they are being put aside and neglected by their oncologist, despite an increased mortality risk |

| [36] | Contending with COVID-19 in association with on-call duties and inappropriate communication techniques | Increased depersonalization and emotional exhaustion, particularly for males and those working more than 50h per week | Mishandling of patient emotions by their oncologists became overwhelming for patients during the pandemic’s progression |

| [37] | The proportion of emergency department admissions to medical oncology increased | The risk of fatigue resulting from the increased workload, leading to poor personal health | A decrease in elective admissions, postponement of non-essential clinic appointments |

| [38] | Required to redefine clinical organization and patient management | Very high perception of risk and concern of infectious danger for their family members | Clash between treatment for patients with cancer and COVID-19 management requirements |

| Citation # | Topic | Topic Details |

| [31,35,38] | Oncologist-centered | Delay of critical surgeries, suspension or reduction of chemotherapy treatments, and change of chemotherapy regimens |

| [31,36,37] | Oncologist-centered | Increased workload |

| [32] | Other-centered | Patients have high COVID-19-associated mortality rates, decreased survival |

| [33,34,36] | Other-centered | Inability to meet with patients in person, telehealth required for meetings |

| Citation # | Topic | Topic Details |

| [31,34,35,36,37] | Oncologist-centered | Posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and fatigue |

| [32] | Other-centered | Increased concern for patients’ health |

| [33] | Other-centered | Ethical distress for requiring telehealth |

| [38] | Other-centered | Concern for family members |

| Citation # | Topic | Topic Details |

| [31,35,36,37] | Oncologist-centered | Poor care from the oncologist |

| [32] | Oncologist-centered | Increased risk of mortality from oncologist burnout |

| [33,34,36] | Oncologist-centered | Loss of intimate contact with oncologist |

| [38] | Other-centered | Patient concerns contrasted with institutional decisions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).