Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

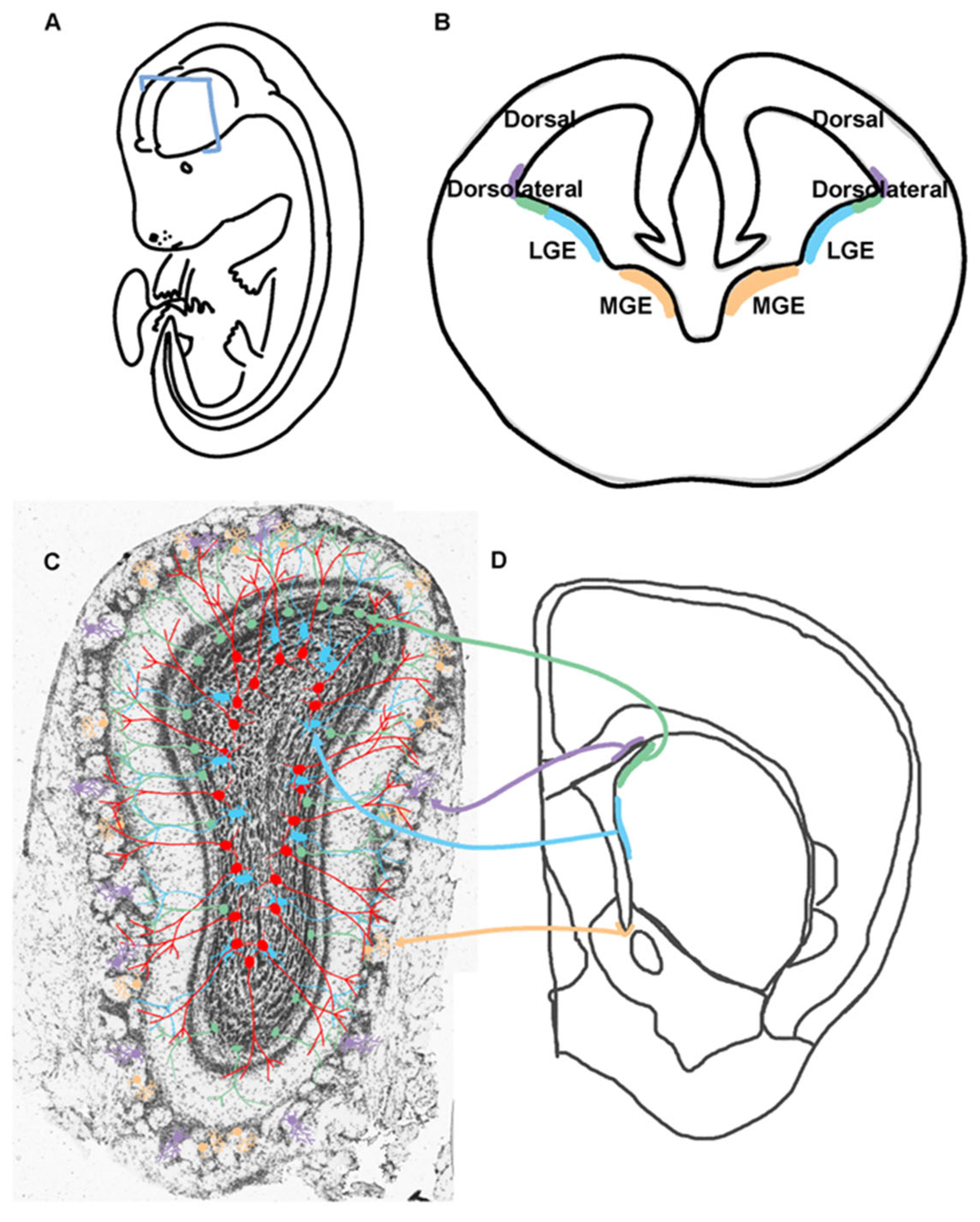

2. Heterogeneity in the V-SVZ

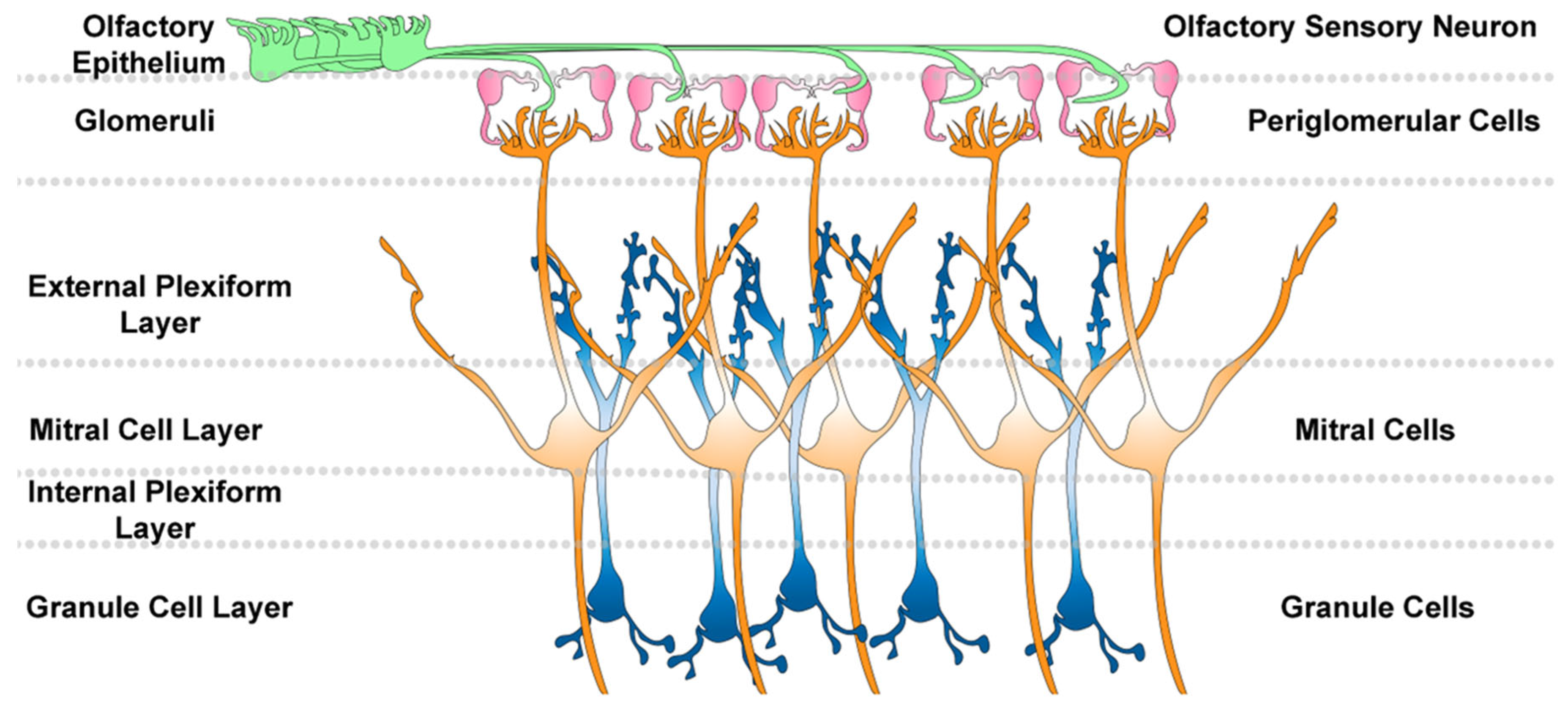

3. Targets of Postnatal Neurogenesis

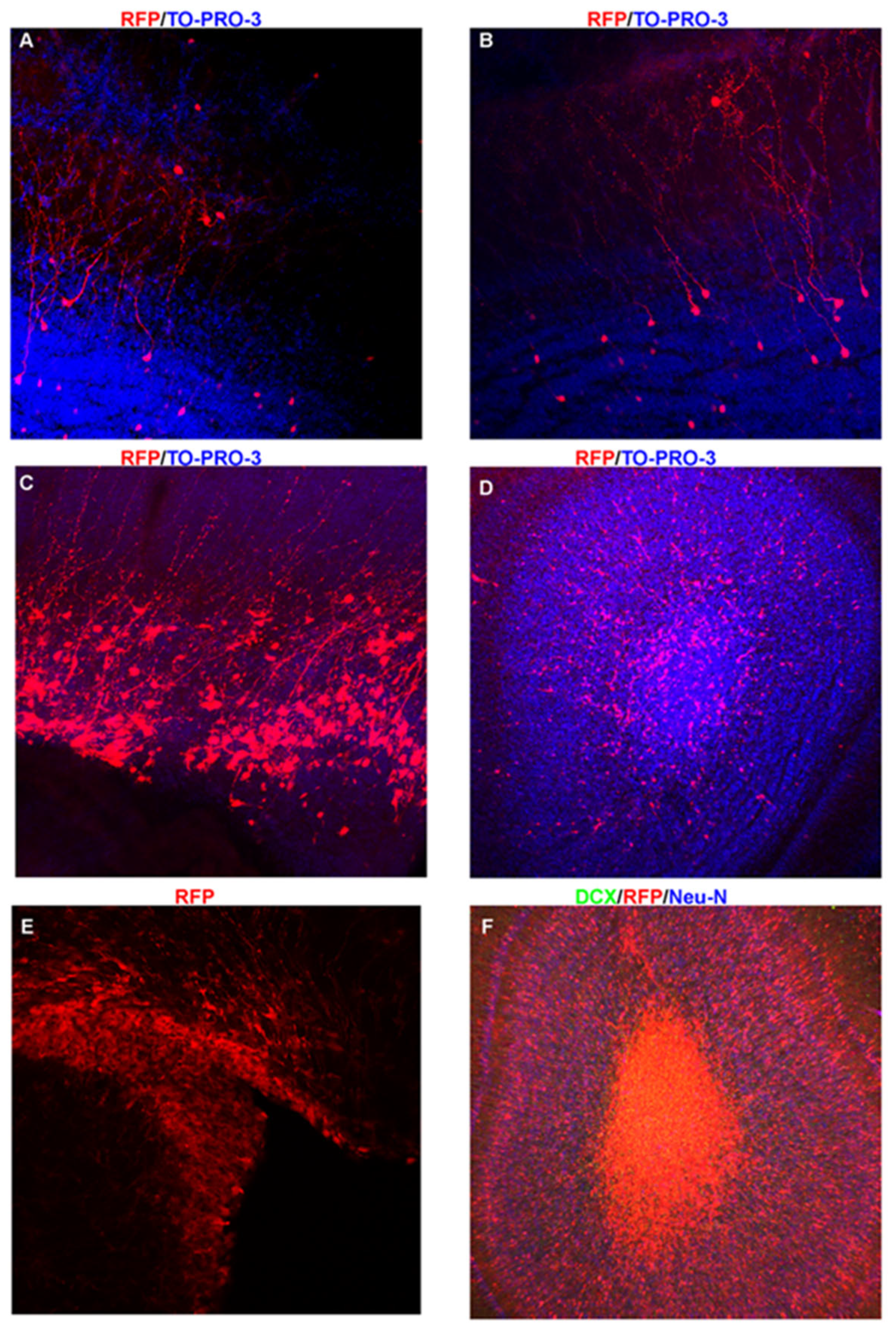

4. Techniques for Studying V-SVZ NSCs

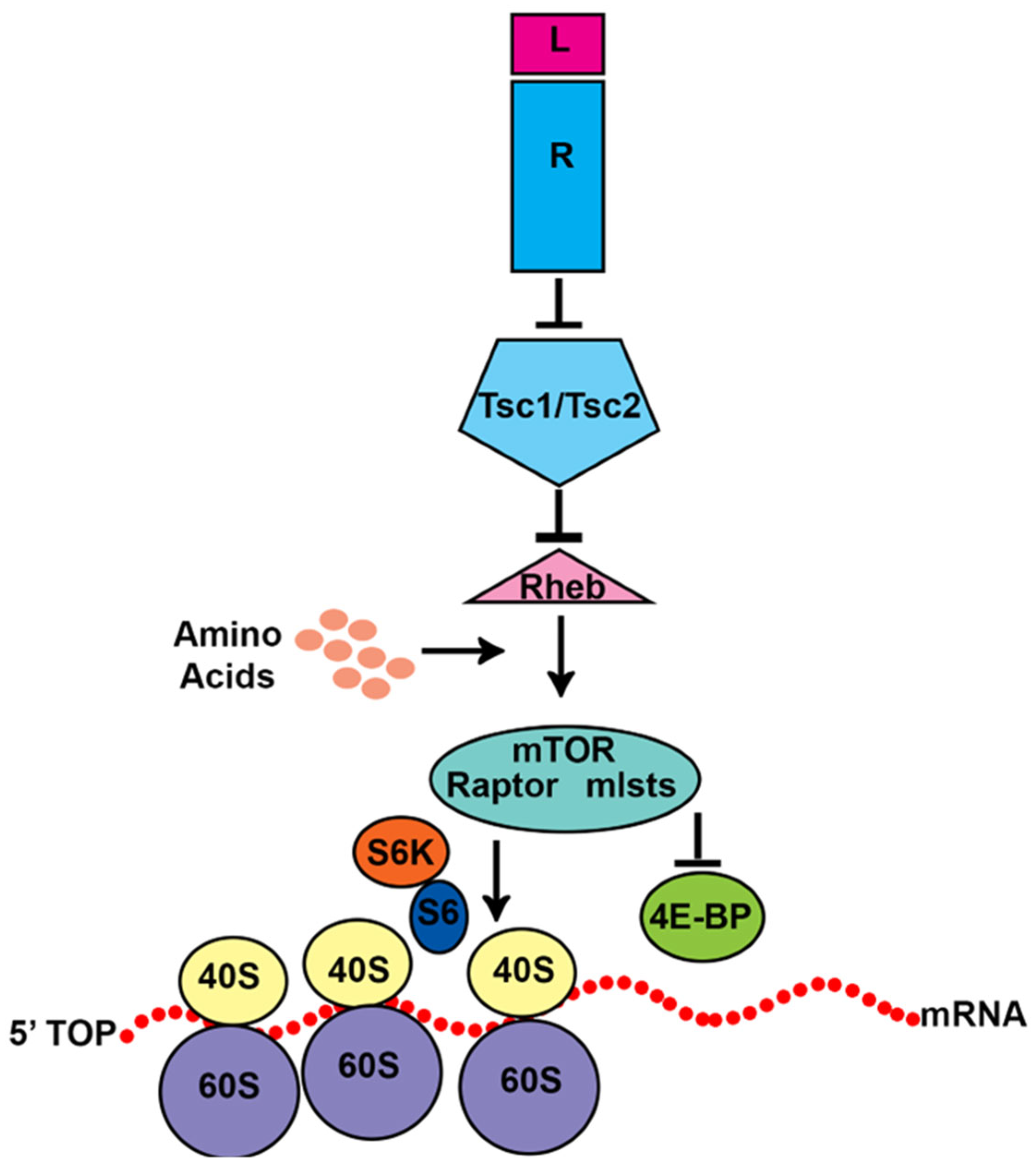

5. The mTOR Pathway

6. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC)

7. The TSC-mTORC1 Pathway in V-SVZ Neurogenesis

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Altman, J.; Das, G.D. Post-Natal Origin of Microneurones in the Rat Brain. Nature 1965, 207, 953–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, J. Autoradiographic study of degenerative and regenerative proliferation of neuroglia cells with tritiated thymidine. Exp. Neurol. 1962, 5, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, J.; Das, G.D. Postnatal Neurogenesis in the Guinea-pig. Nature 1967, 214, 1098–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, J. Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. IV. Cell proliferation and migration in the anterior forebrain, with special reference to persisting neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb. J. Comp. Neurol. 1969, 137, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doetsch, F.; García-Verdugo, J.M.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Cellular Composition and Three-Dimensional Organization of the Subventricular Germinal Zone in the Adult Mammalian Brain. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 5046–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luskin, M.B. Restricted proliferation and migration of postnatally generated neurons derived from the forebrain subventricular zone. Neuron 1993, 11, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihrie, R.A.; Álvarez-Buylla, A. Lake-Front Property: A Unique Germinal Niche by the Lateral Ventricles of the Adult Brain. Neuron 2011, 70, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casingal, C.R.; Descant, K.D.; Anton, E. Coordinating cerebral cortical construction and connectivity: Unifying influence of radial progenitors. Neuron 2022, 110, 1100–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, K.Y.; Šestan, N.; Anton, E.S. Transcriptional co-regulation of neuronal migration and laminar identity in the neocortex. Development 2012, 139, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.A.; Suzuki, S.O.; Goldman, J.E. Gliogenic and neurogenic progenitors of the subventricular zone: Who are they, where did they come from, and where are they going? Glia 2003, 43, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegstein, A.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. The Glial Nature of Embryonic and Adult Neural Stem Cells. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 32, 149–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Chevigny, A.; Core, N.; Follert, P.; Wild, S.; Bosio, A.; Yoshikawa, K.; Cremer, H.; Beclin, C. Dynamic expression of the pro-dopaminergic transcription factors Pax6 and Dlx2 during postnatal olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winpenny, E.; Lebel-Potter, M.; E Fernandez, M.; Brill, M.S.; Götz, M.; Guillemot, F.; Raineteau, O. Sequential generation of olfactory bulb glutamatergic neurons by Neurog2-expressing precursor cells. Neural Dev. 2011, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkle, F.T.; Mirzadeh, Z.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Mosaic Organization of Neural Stem Cells in the Adult Brain. Science 2007, 317, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, F.T.; Fuentealba, L.C.; A Sanders, T.; Magno, L.; Kessaris, N.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Adult neural stem cells in distinct microdomains generate previously unknown interneuron types. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, R.N.; Lim, D.A. Embryonic Nkx2.1-expressing neural precursor cells contribute to the regional heterogeneity of adult V–SVZ neural stem cells. Dev. Biol. 2015, 407, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenman, J.; Toresson, H.; Campbell, K. Identification of Two Distinct Progenitor Populations in the Lateral Ganglionic Eminence: Implications for Striatal and Olfactory Bulb Neurogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Dimos, J.T.; A Fasano, C.; Phoenix, T.N.; Lemischka, I.R.; Ivanova, N.B.; Stifani, S.; E Morrisey, E.; Temple, S. The timing of cortical neurogenesis is encoded within lineages of individual progenitor cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, A.C.; Maldonado-Soto, A.R.; Silva-Vargas, V.; Mizrak, D.; von Känel, T.; Tan, K.R.; Paul, A.; Madar, A.; Cuervo, H.; Kitajewski, J.; et al. Release of stem cells from quiescence reveals gliogenic domains in the adult mouse brain. Science 2021, 372, 1205–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois, C.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Long-Distance Neuronal Migration in the Adult Mammalian Brain. Science 1994, 264, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doetsch, F.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Network of tangential pathways for neuronal migration in adult mammalian brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 14895–14900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, M.C.; Greer, C.A. Synaptic Integration of Adult-Generated Olfactory Bulb Granule Cells: Basal Axodendritic Centrifugal Input Precedes Apical Dendrodendritic Local Circuits. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 9951–9961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluzzi, O.; Benedusi, M.; Ackman, J.; LoTurco, J.J. Electrophysiological Differentiation of New Neurons in the Olfactory Bulb. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 10411–10418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailor, K.A.; Valley, M.T.; Wiechert, M.T.; Riecke, H.; Sun, G.J.; Adams, W.; Dennis, J.C.; Sharafi, S.; Ming, G.-L.; Song, H.; et al. Persistent Structural Plasticity Optimizes Sensory Information Processing in the Olfactory Bulb. Neuron 2016, 91, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsch, W.; Lin, C.-W.; Lois, C. Sequential development of synapses in dendritic domains during adult neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16803–16808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, G.M.; Chen, W.R.; Willhite, D.; Migliore, M.; Greer, C.A. The olfactory granule cell: From classical enigma to central role in olfactory processing. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 55, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rall, W.; Shepherd, G.; Reese, T.; Brightman, M. Dendrodendritic synaptic pathway for inhibition in the olfactory bulb. Exp. Neurol. 1966, 14, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepousez, G.; Valley, M.T.; Lledo, P.-M. The Impact of Adult Neurogenesis on Olfactory Bulb Circuits and Computations. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013, 75, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.M.; Linster, C.; Escanilla, O.; Sacquet, J.; Didier, A.; Mandairon, N. Olfactory perceptual learning requires adult neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 17980–17985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, A.; Alkass, K.; Bernard, S.; Salehpour, M.; Perl, S.; Tisdale, J.; Possnert, G.; Druid, H.; Frisén, J. Neurogenesis in the Striatum of the Adult Human Brain. Cell 2014, 156, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klausa, G.; Prime, G.; Bruggencate, G.T.; Schlösser, B. Postnatal development of calretinin- and parvalbumin-positive interneurons in the rat neostriatum: An immunohistochemical study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999, 405, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, D.; Dumitru, I.; Zuccotti, A.; Yen, T.-Y.; Herranz-Pérez, V.; Tan, L.L.; Neitz, A.; García-Verdugo, J.M.; Kuner, R.; Alfonso, J.; et al. Neurogenesis of medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens continues into adulthood and is enhanced by pathological pain. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4616–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Ninomiya, M.; Acosta, P.H.; García-Verdugo, J.M.; Sunabori, T.; Sakaguchi, M.; Adachi, K.; Kojima, T.; Hirota, Y.; Kawase, T.; et al. Subventricular Zone-Derived Neuroblasts Migrate and Differentiate into Mature Neurons in the Post-Stroke Adult Striatum. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 6627–6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanai, N.; Nguyen, T.; Ihrie, R.A.; Mirzadeh, Z.; Tsai, H.-H.; Wong, M.; Gupta, N.; Berger, M.S.; Huang, E.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.-M.; et al. Corridors of migrating neurons in the human brain and their decline during infancy. Nature 2011, 478, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.A.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. The Adult Ventricular–Subventricular Zone (V-SVZ) and Olfactory Bulb (OB) Neurogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a018820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inta, D.; Alfonso, J.; von Engelhardt, J.; Kreuzberg, M.M.; Meyer, A.H.; van Hooft, J.A.; Monyer, H. Neurogenesis and widespread forebrain migration of distinct GABAergic neurons from the postnatal subventricular zone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 20994–20999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.-P.; Miyawaki, A.; Gage, F.H.; Jan, Y.N.; Jan, L.Y. Local generation of glia is a major astrocyte source in postnatal cortex. Nature 2012, 484, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzadeh, Z.; Merkle, F.T.; Soriano-Navarro, M.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Neural Stem Cells Confer Unique Pinwheel Architecture to the Ventricular Surface in Neurogenic Regions of the Adult Brain. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 3, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, H.G.; Winkler, J.; Kempermann, G.; Thal, L.J.; Gage, F.H. Epidermal Growth Factor and Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 Have Different Effects on Neural Progenitors in the Adult Rat Brain. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 5820–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doetsch, F.; Caillé, I.; Lim, D.A.; García-Verdugo, J.M.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Subventricular Zone Astrocytes Are Neural Stem Cells in the Adult Mammalian Brain. Cell 1999, 97, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, M.C.; Neckles, V.N.; Seluzicki, C.M.; Holmberg, J.C.; Feliciano, D.M. Neonatal Subventricular Zone Neural Stem Cells Release Extracellular Vesicles that Act as a Microglial Morphogen. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitz, M.; Pfannkuche, K.; Rajewsky, K.; Edenhofer, F. Ability of the hydrophobic FGF and basic TAT peptides to promote cellular uptake of recombinant Cre recombinase: A tool for efficient genetic engineering of mammalian genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4489–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatazza, J.; Lee, H.H.; Di Nardo, A.A.; Tibaldi, L.; Joliot, A.; Hensch, T.K.; Prochiantz, A. Choroid-Plexus-Derived Otx2 Homeoprotein Constrains Adult Cortical Plasticity. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1815–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutin, C.; Diestel, S.; Desoeuvre, A.; Tiveron, M.-C.; Cremer, H. Efficient In Vivo Electroporation of the Postnatal Rodent Forebrain. PLOS ONE 2008, 3, e1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.M.; Lafourcade, C.A.; Bordey, A. Neonatal Subventricular Zone Electroporation. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, e50197–e50197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, N.W.; Lin, T.V.; Zhang, L.; Paquelet, G.E.; Feliciano, D.M.; Bordey, A. mTORC1 Targets the Translational Repressor 4E-BP2, but Not S6 Kinase 1/2, to Regulate Neural Stem Cell Self-Renewal In Vivo. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, J.C.; Riley, V.A.; Sokolov, A.M.; Mukherjee, S.; Feliciano, D.M. Protocol for electroporating and isolating murine (sub)ventricular zone cells for single-nuclei omics. STAR Protoc. 2024, 5, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.M.; Su, T.; Lopez, J.; Platel, J.-C.; Bordey, A. Single-cell Tsc1 knockout during corticogenesis generates tuber-like lesions and reduces seizure threshold in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 1596–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platel, J.-C.; Dave, K.A.; Gordon, V.; Lacar, B.; Rubio, M.E.; Bordey, A. NMDA Receptors Activated by Subventricular Zone Astrocytic Glutamate Are Critical for Neuroblast Survival Prior to Entering a Synaptic Network. Neuron 2010, 65, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, F.; Chen, F.; Aron, A.W.; Fiondella, C.G.; Patel, K.; LoTurco, J.J. Fate Mapping by PiggyBac Transposase Reveals That Neocortical GLAST+ Progenitors Generate More Astrocytes Than Nestin+ Progenitors in Rat Neocortex. Cereb. Cortex 2014, 24, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Rosiene, J.; Che, A.; Becker, A.; LoTurco, J. Tracking and transforming neocortical progenitors by CRISPR/Cas9 gene targeting and PiggyBac transposase lineage labeling. Development 2015, 142, 3601–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, V.A.; Holmberg, J.C.; Sokolov, A.M.; Feliciano, D.M. Tsc2 shapes olfactory bulb granule cell molecular and morphological characteristics. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 970357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Miyata, T. Embryonic Neocortical Microglia Express Toll-Like Receptor 9 and Respond to Plasmid DNA Injected into the Ventricle: Technical Considerations Regarding Microglial Distribution in Electroporated Brain Walls. eneuro 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagace, D.C.; Whitman, M.C.; Noonan, M.A.; Ables, J.L.; DeCarolis, N.A.; Arguello, A.A.; Donovan, M.H.; Fischer, S.J.; Farnbauch, L.A.; Beech, R.D.; et al. Dynamic Contribution of Nestin-Expressing Stem Cells to Adult Neurogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 12623–12629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levison, S.W.; Goldman, J.E. Both oligodendrocytes and astrocytes develop from progenitors in the subventricular zone of postnatal rat forebrain. Neuron 1993, 10, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, C. , Kudelski, A. & Sehgal, S. N. Rapamycin (AY-22, 989) a new antifungal antibiotic. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1975, 28, 721–726. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, D.M.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Lui, M.; Tempst, P.; Snyder, S.H. RAFT1: A mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a rapamycin-dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs. Cell 1994, 78, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, P.E.; Barrow, R.K.; Cohen, N.A.; Snyder, S.H.; Sabatini, D.M. RAFT1 phosphorylation of the translational regulators p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 1432–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Kuo, C.J.; Crabtree, G.R.; Blenis, J. Rapamycin-FKBP specifically blocks growth-dependent activation of and signaling by the 70 kd S6 protein kinases. Cell 1992, 69, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.J.; Albers, M.W.; Shin, T.B.; Ichikawa, K.; Keith, C.T.; Lane, W.S.; Schreiber, S.L. A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin–receptor complex. Nature 1994, 369, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabers, C.J.; Martin, M.M.; Brunn, G.J.; Williams, J.M.; Dumont, F.J.; Wiederrecht, G.; Abraham, R.T. Isolation of a Protein Target of the FKBP12-Rapamycin Complex in Mammalian Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, D.W.; Ye, L.; Katajisto, P.; Goncalves, M.D.; Saitoh, M.; Stevens, D.M.; Davis, J.G.; Salmon, A.B.; Richardson, A.; Ahima, R.S.; et al. Rapamycin-Induced Insulin Resistance Is Mediated by mTORC2 Loss and Uncoupled from Longevity. Science 2012, 335, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbassov, D.D.; Ali, S.M.; Sengupta, S.; Sheen, J.-H.; Hsu, P.P.; Bagley, A.F.; Markhard, A.L.; Sabatini, D.M. Prolonged Rapamycin Treatment Inhibits mTORC2 Assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol. Cell 2006, 22, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, C.K.; Murata, K.; Walz, T.; Sabatini, D.M.; Kang, S.A. Structure of the Human mTOR Complex I and Its Implications for Rapamycin Inhibition. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylett, C.H.S.; Sauer, E.; Imseng, S.; Boehringer, D.; Hall, M.N.; Ban, N.; Maier, T. Architecture of human mTOR complex 1. Science 2016, 351, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, K.; Maruki, Y.; Long, X.; Yoshino, K.-I.; Oshiro, N.; Hidayat, S.; Tokunaga, C.; Avruch, J.; Yonezawa, K. Raptor, a Binding Partner of Target of Rapamycin (TOR), Mediates TOR Action. Cell 2002, 110, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos, D.S.; et al. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Gingras, A.-C.; Gygi, S.P.; Raught, B.; Polakiewicz, R.D.; Abraham, R.T.; Hoekstra, M.F.; Aebersold, R.; Sonenberg, N. Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: a novel two-step mechanism. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 1422–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, P.E.; Barrow, R.K.; Cohen, N.A.; Snyder, S.H.; Sabatini, D.M. RAFT1 phosphorylation of the translational regulators p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 1432–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, D.J.; Grove, J.R.; Calvo, V.; Avruch, J.; Bierer, B.E.; Grove, J.R. Rapamycin-Induced Inhibition of the 70-Kilodalton S6 Protein Kinase. Science 1992, 257, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoki, K.; Li, Y.; Xu, T.; Guan, K.-L. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Saucedo, L.J.; Ru, B.; Edgar, B.A.; Pan, D. Rheb is a direct target of the tuberous sclerosis tumour suppressor proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, A.R.; Manning, B.D.; Roux, P.P.; Cantley, L.C.; Blenis, J. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Gene Products, Tuberin and Hamartin, Control mTOR Signaling by Acting as a GTPase-Activating Protein Complex toward Rheb. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garami, A.; Zwartkruis, F.J.; Nobukuni, T.; Joaquin, M.; Roccio, M.; Stocker, H.; Kozma, S.C.; Hafen, E.; Bos, J.L.; Thomas, G. Insulin Activation of Rheb, a Mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP Signaling, Is Inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 1457–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibble, C.C.; Elis, W.; Menon, S.; Qin, W.; Klekota, J.; Asara, J.M.; Finan, P.M.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Murphy, L.O.; Manning, B.D. TBC1D7 Is a Third Subunit of the TSC1-TSC2 Complex Upstream of mTORC1. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbani, D. M.; Crino, P. B. Tuberous sclerosis complex. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 2018, 148, 813–822. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D.L.; Calder, T.; Lawson, J.A.; Mowat, D.; Kennedy, S.E. The natural history of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis complex: a review. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 29, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.M. The Neurodevelopmental Pathogenesis of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC). Front. Neuroanat. 2020, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Slegtenhorst, M.; et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science 277, 805–808 (1997).

- The European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium. Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell 75, 1305–1315 (1993).

- Henske, E. P. , Jóźwiak, S., Kingswood, J. C., Sampson, J. R. & Thiele, E. A. Tuberous sclerosis complex. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2, 16035 (2016).

- Feliciano, D.M.; Lin, T.V.; Hartman, N.W.; Bartley, C.M.; Kubera, C.; Hsieh, L.; Lafourcade, C.; O'Keefe, R.A.; Bordey, A. A circuitry and biochemical basis for tuberous sclerosis symptoms: from epilepsy to neurocognitive deficits. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2013, 31, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zywitza, V.; Misios, A.; Bunatyan, L.; Willnow, T.E.; Rajewsky, N. Single-Cell Transcriptomics Characterizes Cell Types in the Subventricular Zone and Uncovers Molecular Defects Impairing Adult Neurogenesis. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2457–2469.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, O.; Krieger, T.G.; Muraro, M.J.; Wiebrands, K.; Stange, D.E.; Frias-Aldeguer, J.; Rivron, N.C.; van de Wetering, M.; van Es, J.H.; van Oudenaarden, A.; et al. Troy+ brain stem cells cycle through quiescence and regulate their number by sensing niche occupancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 201715911–E619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrian-Silla, A.; Nascimento, M.A.; A Redmond, S.; Mansky, B.; Wu, D.; Obernier, K.; Rodriguez, R.R.; Gonzalez-Granero, S.; García-Verdugo, J.M.; A Lim, D.; et al. Single-cell analysis of the ventricular-subventricular zone reveals signatures of dorsal and ventral adult neurogenesis. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.D.; Hockemeyer, D.; Doudna, J.A.; Bateup, H.S.; Floor, S.N. Widespread Translational Remodeling during Human Neuronal Differentiation. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 2005–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, A.; Skabkin, M.; Kleber, S.; Dang, Y.; Balta, G.S.G.; Kalamakis, G.; Göpferich, M.; Ibañez, D.C.; Schefzik, R.; Lopez, A.S.; et al. Onset of differentiation is post-transcriptionally controlled in adult neural stem cells. Nature 2019, 566, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, A.; Skabkin, M.; Kleber, S.; Dang, Y.; Balta, G.S.G.; Kalamakis, G.; Göpferich, M.; Ibañez, D.C.; Schefzik, R.; Lopez, A.S.; et al. Onset of differentiation is post-transcriptionally controlled in adult neural stem cells. Nature 2019, 566, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paliouras, G.N.; Hamilton, L.K.; Aumont, A.; Joppé, S.E.; Barnabé-Heider, F.; Fernandes, K.J.L. Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling Is a Key Regulator of the Transit-Amplifying Progenitor Pool in the Adult and Aging Forebrain. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 15012–15026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.A.; Pacold, M.E.; Cervantes, C.L.; Lim, D.; Lou, H.J.; Ottina, K.; Gray, N.S.; Turk, B.E.; Yaffe, M.B.; Sabatini, D.M. mTORC1 Phosphorylation Sites Encode Their Sensitivity to Starvation and Rapamycin. Science 2013, 341, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochard, L.M.; Levros, L.-C.; Joppé, S.E.; Pratesi, F.; Aumont, A.; Fernandes, K.J.L. Manipulation of EGFR-Induced Signaling for the Recruitment of Quiescent Neural Stem Cells in the Adult Mouse Forebrain. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, E.C.; Hively, W.P.; DePinho, R.A.; Varmus, H.E. A constitutively active epidermal growth factor receptor cooperates with disruption of G1 cell-cycle arrest pathways to induce glioma-like lesions in mice. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 3675–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Pozuelo, J.; Figlia, G.; Kaya, O.; Martin-Villalba, A.; Teleman, A.A. Cdk4 and Cdk6 Couple the Cell-Cycle Machinery to Cell Growth via mTORC1. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

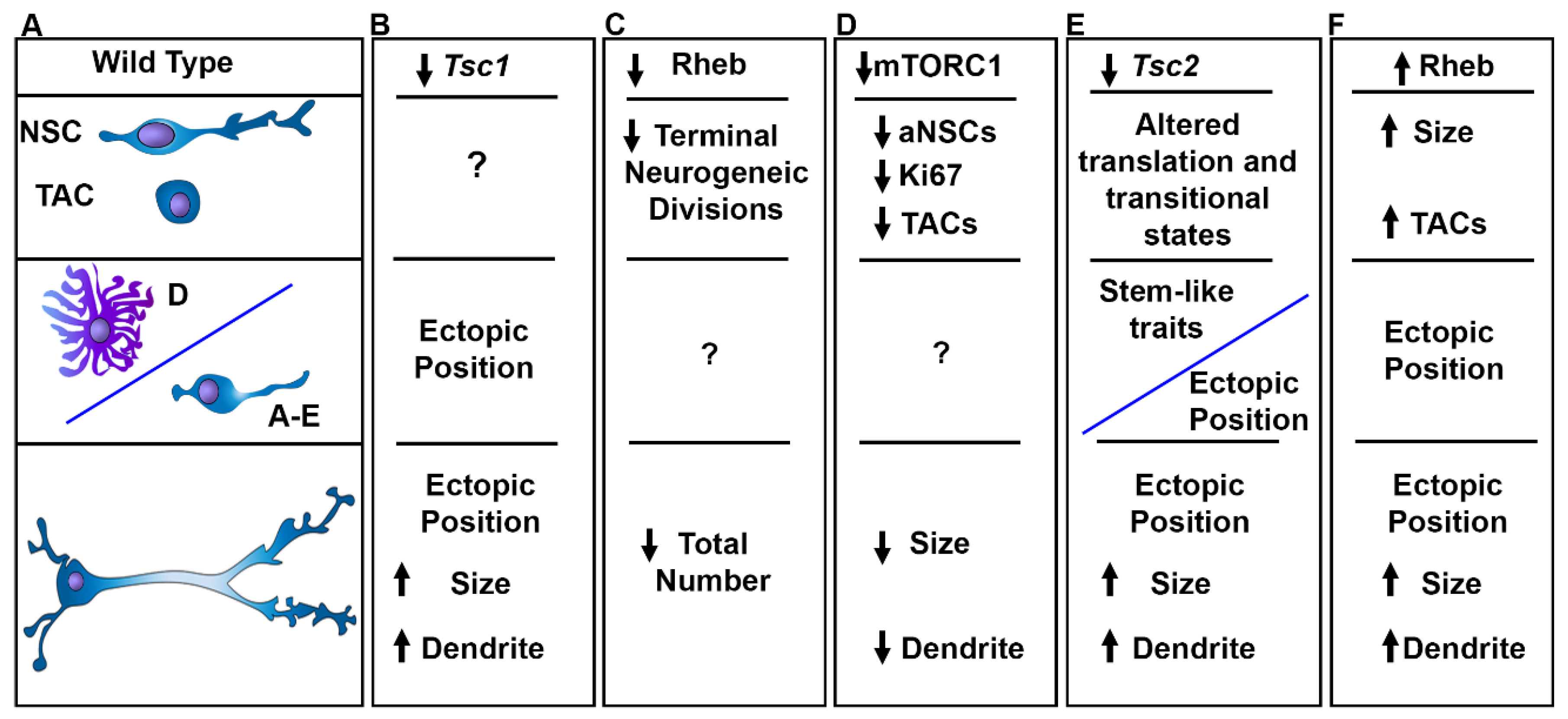

- Zhou, J.; Shrikhande, G.; Xu, J.; McKay, R.M.; Burns, D.K.; Johnson, J.E.; Parada, L.F. Tsc1 mutant neural stem/progenitor cells exhibit migration deficits and give rise to subependymal lesions in the lateral ventricle. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, C.; Feliciano, D.M.; Bordey, A.; Hartman, N.W. Switching on mTORC1 induces neurogenesis but not proliferation in neural stem cells of young mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 614, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feliciano, D.M.; Quon, J.L.; Su, T.; Taylor, M.M.; Bordey, A. Postnatal neurogenesis generates heterotopias, olfactory micronodules and cortical infiltration following single-cell Tsc1 deletion. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushing, G.V.; A Brockman, A.; Bollig, M.K.; Leelatian, N.; Mobley, B.C.; Irish, J.M.; Ess, K.C.; Fu, C.; A Ihrie, R. Location-dependent maintenance of intrinsic susceptibility to mTORC1-driven tumorigenesis. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201800218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, J.A.; Talley, T.; Qiu, M.; Puelles, L.; Rubenstein, J.L.R.; Jones, K.R. Cortical Excitatory Neurons and Glia, But Not GABAergic Neurons, Are Produced in the Emx1-Expressing Lineage. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 6309–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohwi, M.; et al. A subpopulation of olfactory bulb GABAergic interneurons is derived from Emx1- and Dlx5/6-expressing progenitors. J. Neurosci. 27, (2007).

- Magri, L.; Cambiaghi, M.; Cominelli, M.; Alfaro-Cervello, C.; Cursi, M.; Pala, M.; Bulfone, A.; Garcìa-Verdugo, J.M.; Leocani, L.; Minicucci, F.; et al. Sustained Activation of mTOR Pathway in Embryonic Neural Stem Cells Leads to Development of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex-Associated Lesions. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 9, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, V.A.; Shankar, V.; Holmberg, J.C.; Sokolov, A.M.; Neckles, V.N.; Williams, K.; Lyman, R.; Mackay, T.F.; Feliciano, D.M. Tsc2 coordinates neuroprogenitor differentiation. iScience 2023, 26, 108442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crino, P.B.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Dichter, M.A.; Eberwine, J. Embryonic neuronal markers in tuberous sclerosis: Single-cell molecular pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 14152–14157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zordan, P.; Cominelli, M.; Cascino, F.; Tratta, E.; Poliani, P.L.; Galli, R. Tuberous sclerosis complex–associated CNS abnormalities depend on hyperactivation of mTORC1 and Akt. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 1688–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafourcade, C.A.; Lin, T.V.; Feliciano, D.M.; Zhang, L.; Hsieh, L.S.; Bordey, A. Rheb Activation in Subventricular Zone Progenitors Leads to Heterotopia, Ectopic Neuronal Differentiation, and Rapamycin-Sensitive Olfactory Micronodules and Dendrite Hypertrophy of Newborn Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 2419–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magini, A.; Polchi, A.; Di Meo, D.; Mariucci, G.; Sagini, K.; De Marco, F.; Cassano, T.; Giovagnoli, S.; Dolcetta, D.; Emiliani, C. TFEB activation restores migration ability to Tsc1-deficient adult neural stem/progenitor cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 3303–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolov, A.M.; Holmberg, J.C.; Feliciano, D.M. The amino acid transporter Slc7a5 regulates the mTOR pathway and is required for granule cell development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020, 29, 3003–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalecka, A.; Liszewska, E.; Bilinski, R.; Gkogkas, C.; Khoutorsky, A.; Malik, A.R.; Sonenberg, N.; Jaworski, J. mTOR kinase is needed for the development and stabilization of dendritic arbors in newly born olfactory bulb neurons. Dev. Neurobiol. 2016, 76, 1308–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.L.; de Anda, F.C.; Mangoubi, T.; Yoshii, A. Multiple Critical Periods for Rapamycin Treatment to Correct Structural Defects in Tsc-1-Suppressed Brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklin, P.; Bergman, P.; Zhang, B.; Triantafellow, E.; Wang, H.; Nyfeler, B.; Yang, H.; Hild, M.; Kung, C.; Wilson, C.; et al. Bidirectional Transport of Amino Acids Regulates mTOR and Autophagy. Cell 2009, 136, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, A.M.; Holmberg, J.C.; Feliciano, D.M. The amino acid transporter Slc7a5 regulates the mTOR pathway and is required for granule cell development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020, 29, 3003–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafourcade, C.A.; Lin, T.V.; Feliciano, D.M.; Zhang, L.; Hsieh, L.S.; Bordey, A. Rheb Activation in Subventricular Zone Progenitors Leads to Heterotopia, Ectopic Neuronal Differentiation, and Rapamycin-Sensitive Olfactory Micronodules and Dendrite Hypertrophy of Newborn Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 2419–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).