Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

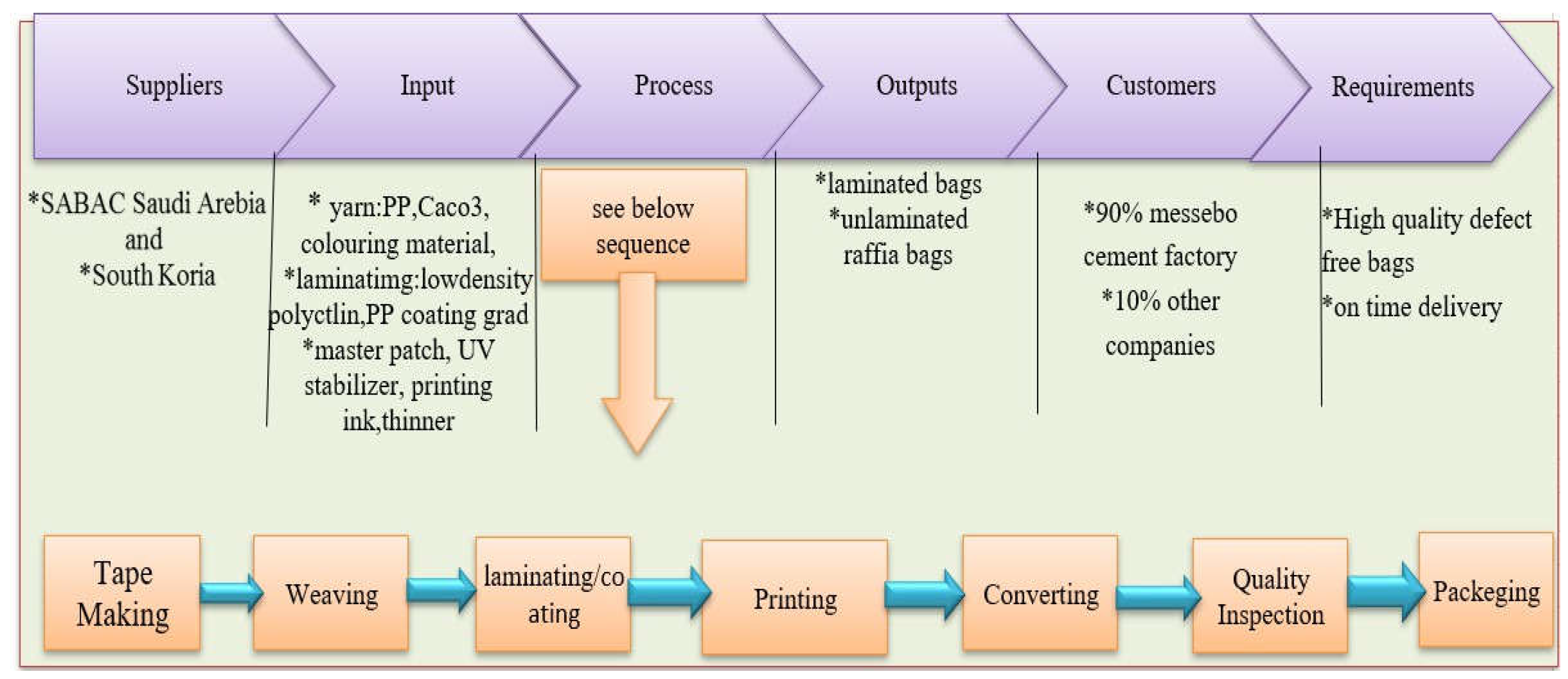

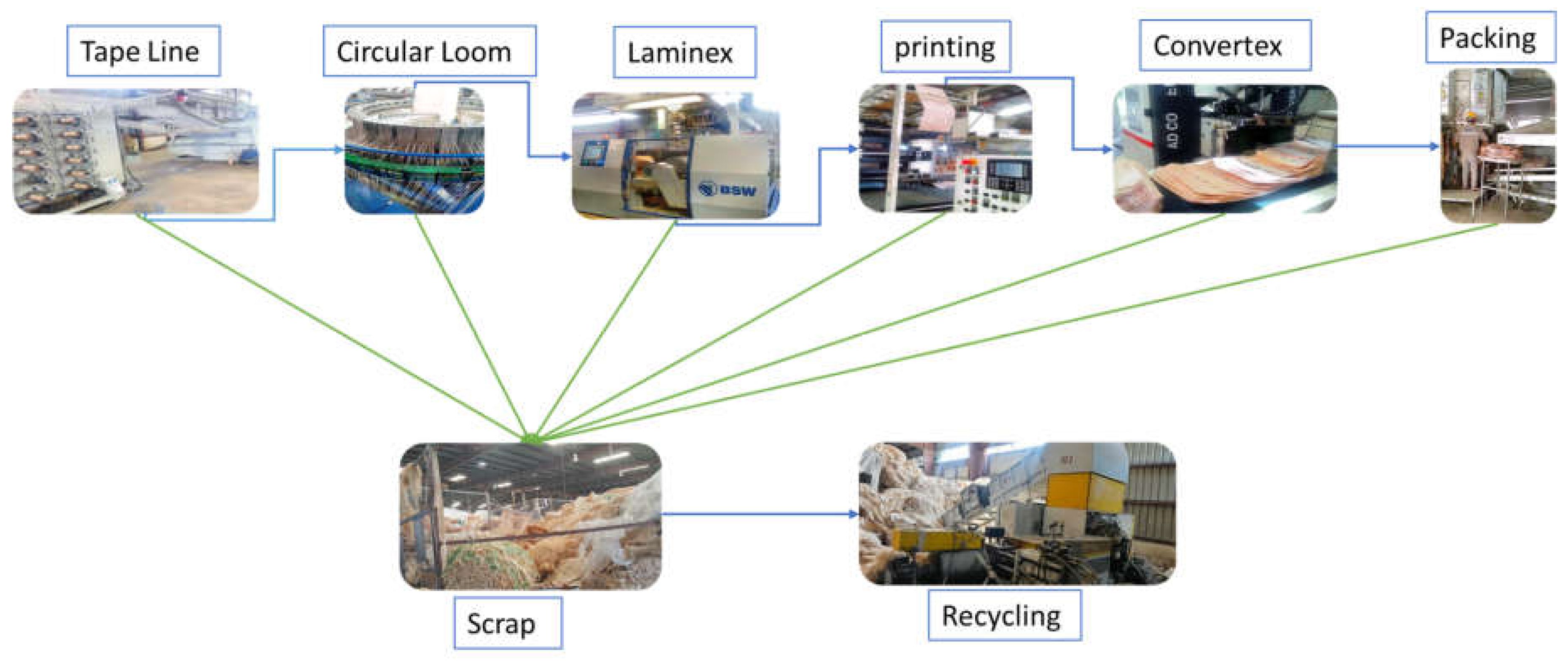

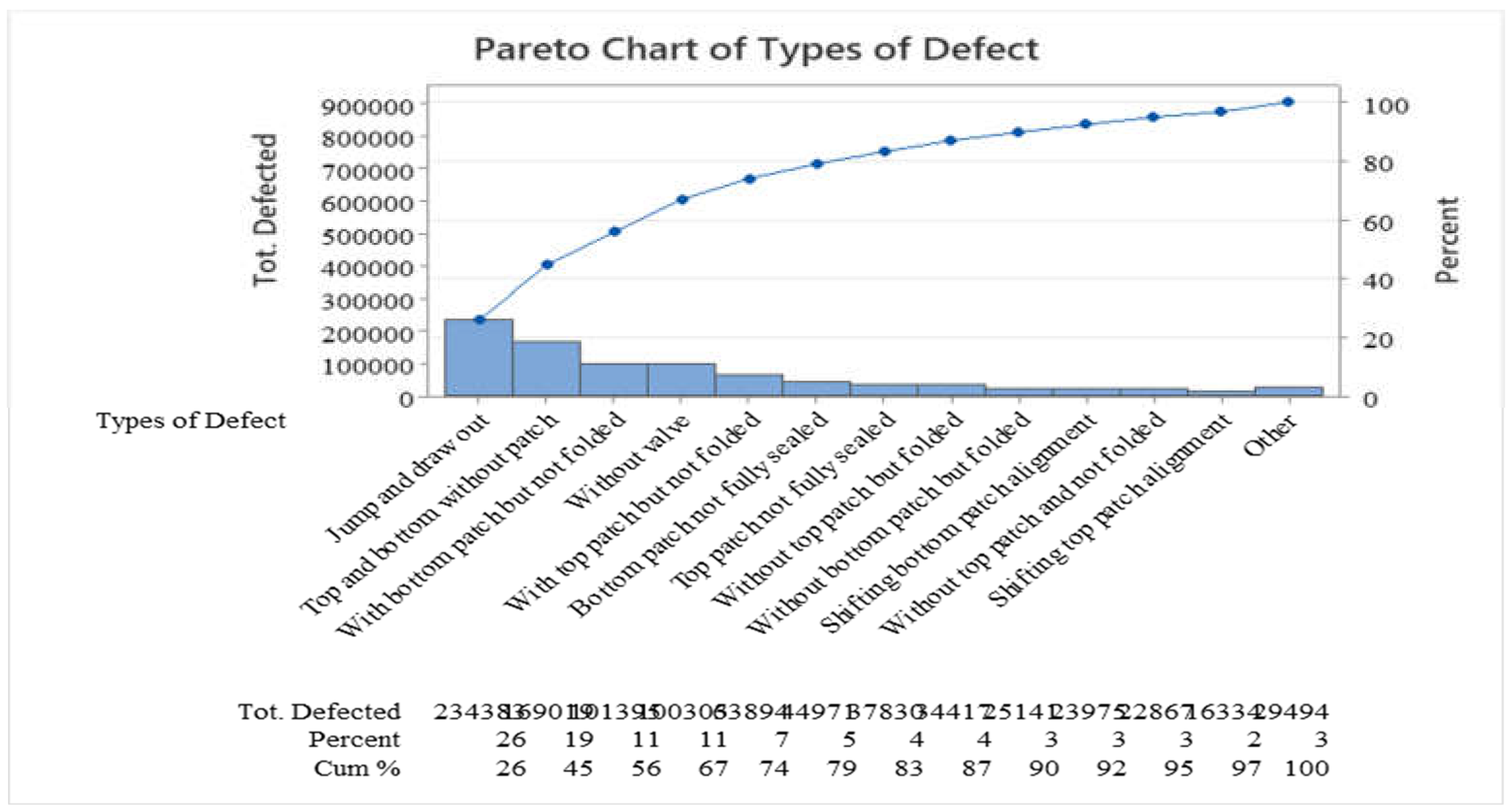

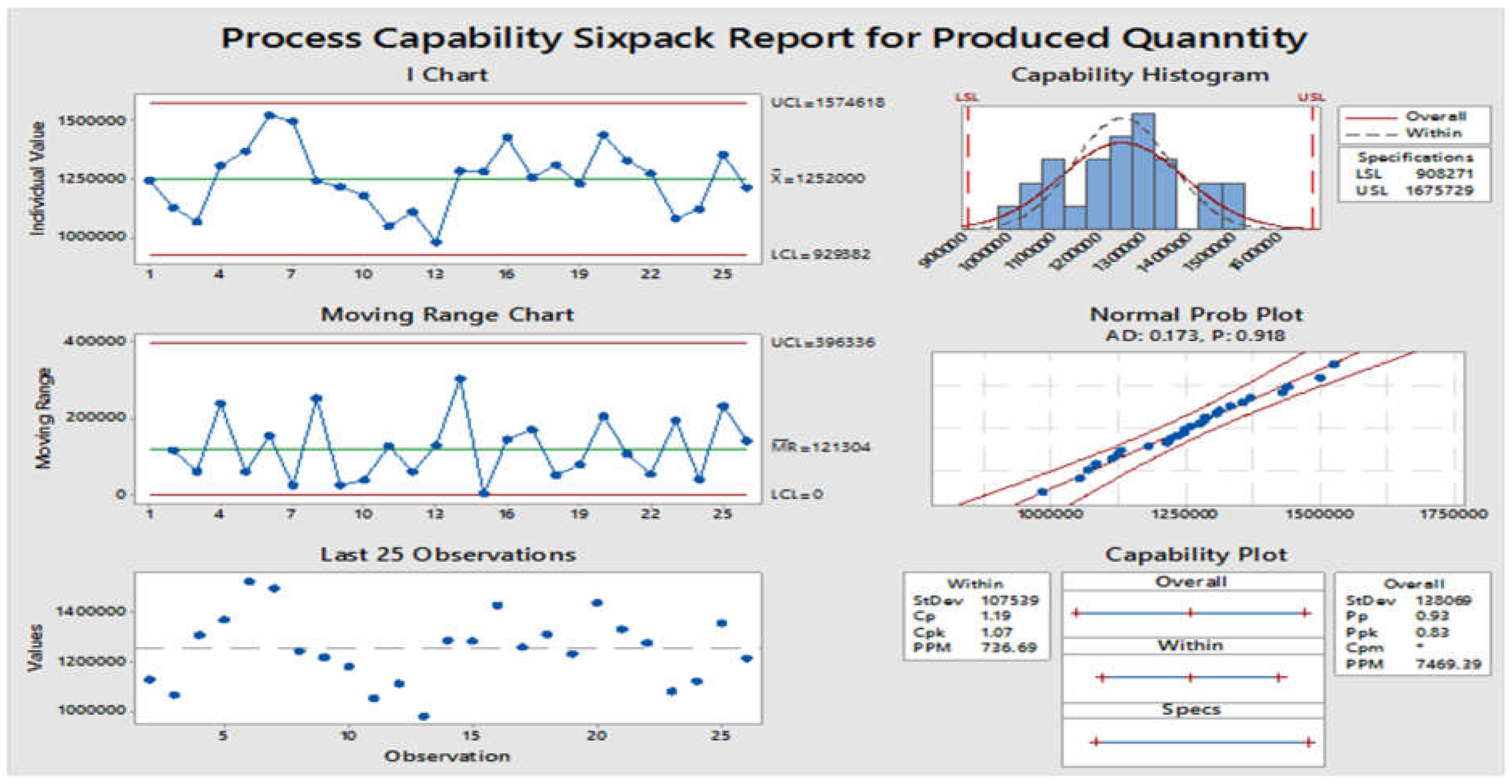

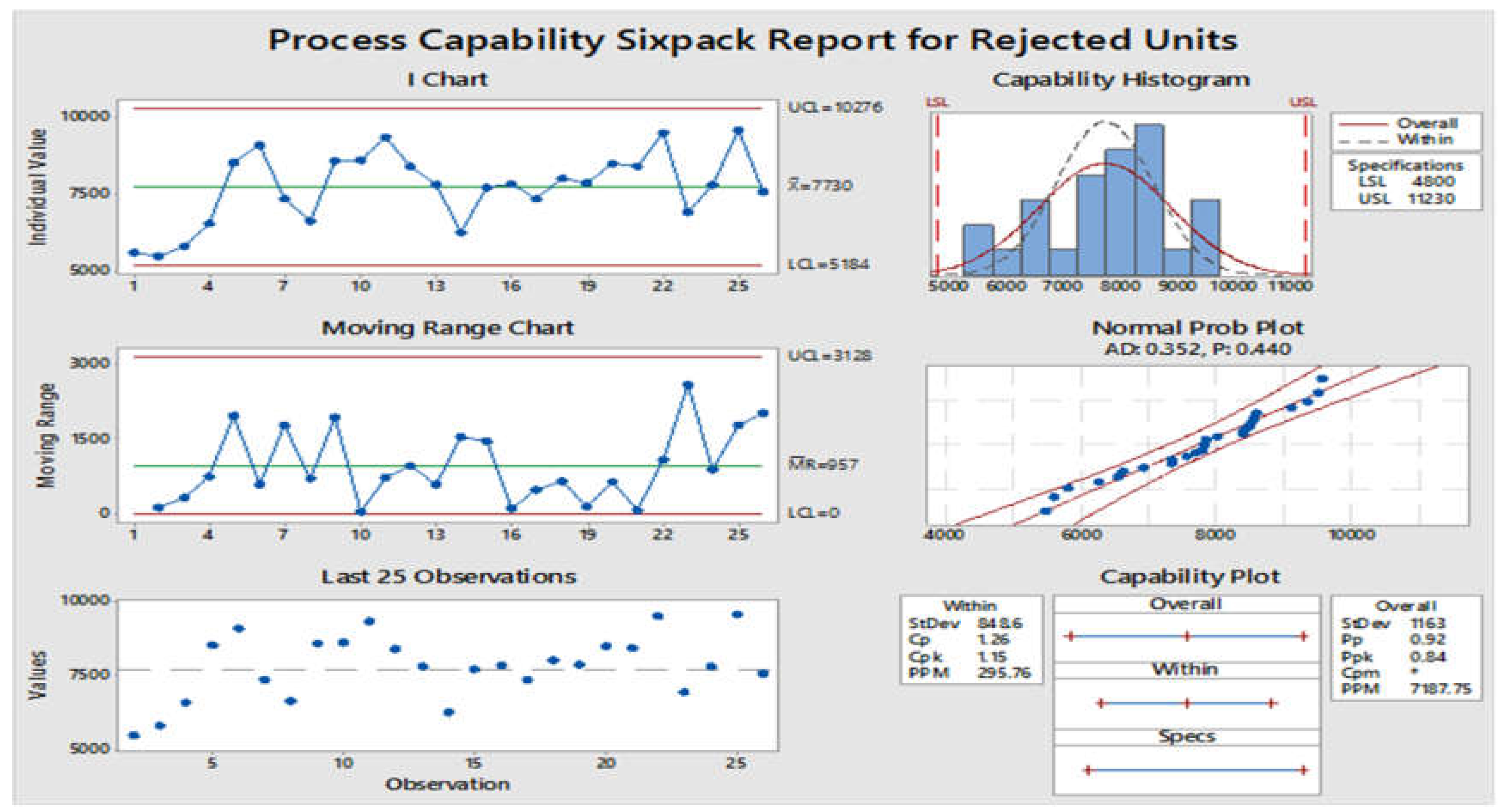

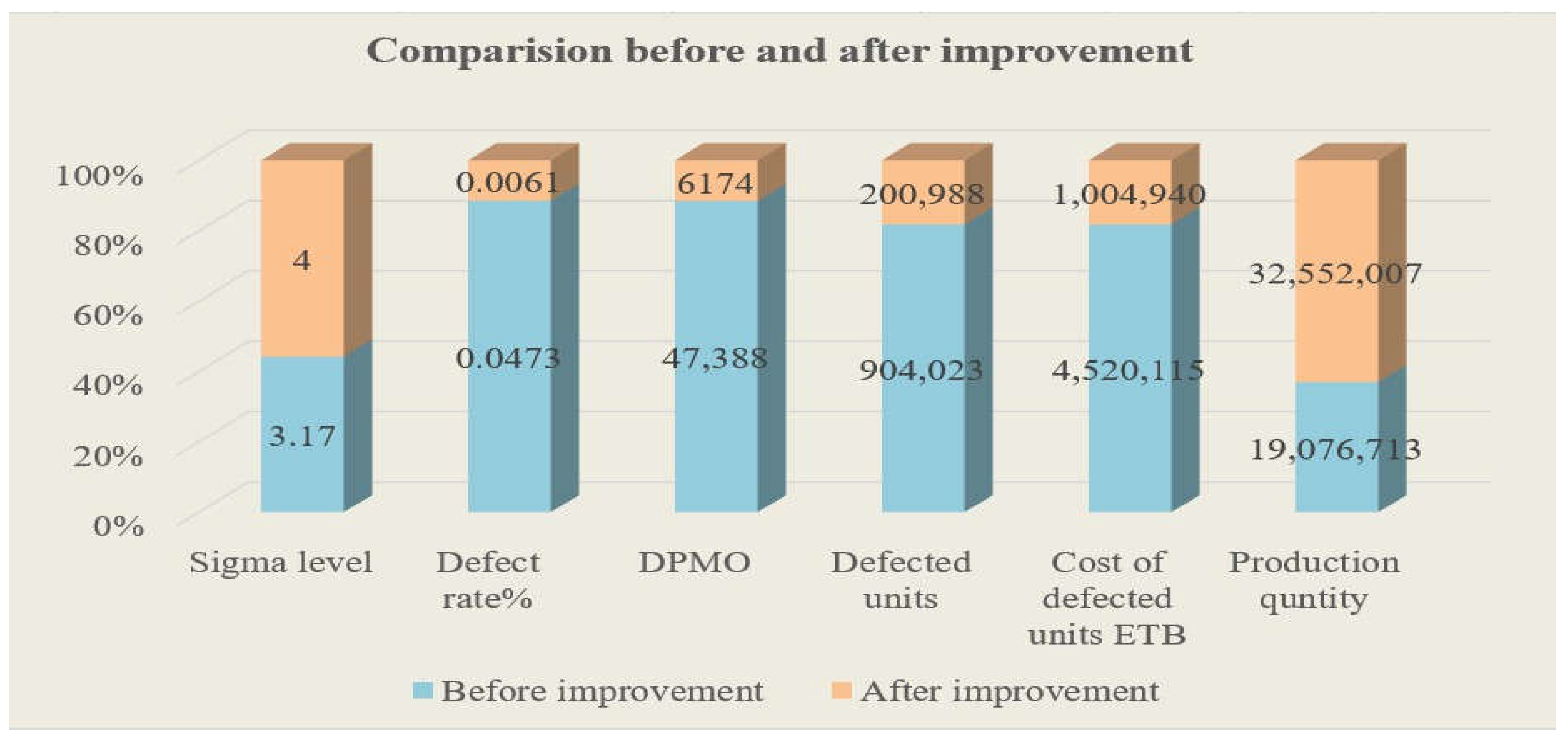

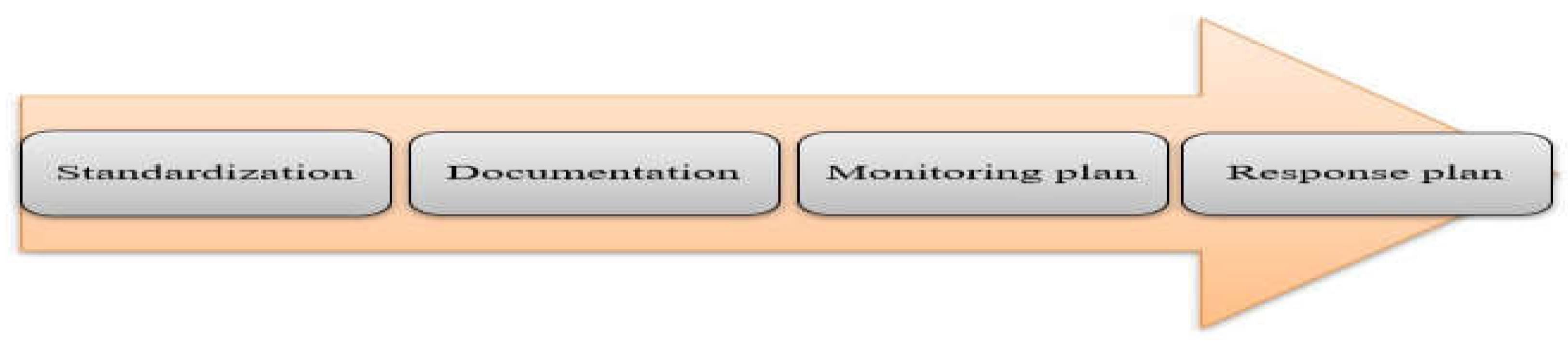

Total Quality Management (TQM) projects, particularly those utilizing Six Sigma, are globally recognized for enhancing quality and productivity in the manufacturing industry. The study applies Six Sigma's DMAIC framework and SQC tools to improve defects in Messebo PP bag manufacturing's Convertex finishing section. The objective is to identify and eliminate defects, reduce rejection rates, and enhance sigma levels. in the define phase of DMAIC process, SIPOC tool, and customer questionnaires were used to map process flows and align improvement efforts with customer requirements (VOC). The Measure phase involved analyzed of existing data considering the performance of the Convertex section and process capability plots were generated to understand the current process performance against requirements. A key six most dominated defects (vital few) contributing to the majority of issues were identified through pareto analysis. The initial performance baseline revealed a Sigma level of 3.17, considered non-competitive, with a defect rate of 4.73%, a Defects Per Million Opportunities (DPMO) of 47,389, and process capability indices of 0.55 and 0.58 for processing quantity and defective units respectively. This data demonstrated the urgent need for improvement. The analyzing phase investigates the root cause of the vital few causes of defects considering team brainstormed and systematically categorized potential causes using Fishbone diagram, in which this structural analysis helps the team to understand past symptoms and underlying reason for the issues and develop effective solutions. Considering analysis phase, in the improvement phase specific solutions were developed and put for improvement, as a result the sigma level becomes 4.00 (industry average), defect rate 0.61%, DPMO 6174, and the process capability of produced quantity and defect units becomes 1.19 and 1.26 respectively, which is very capable and led to significant and immediate positive results in the overall quality and productivity of the Convertex section. Lastly, the control phase was conducted to sustain the results found in the improvement phase and to keep the changes moving forward. It has four procedures, standardization documentation, monitoring plan, and response plan, which control the newly implemented changes and developed procedures.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Justification and Specific Objectives of the Study

2. Literature Review

2.1. Total Quality Management

2.2. Quality Control

2.3. Six Sigma and Its Application in Manufacturing Process

3. Methodology

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. Defining Phase

4.1.1. Flow Chart and Detail Expression of the Company

4.1.2. Voice of Customers

| Q/no | Excellent | Very Good | Good | Average | Poor | No of Respondents | Education | No of Respondents | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 20 | Below Diploma | 5 | 25% |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 20 | Collage Diploma | 8 | 40% |

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 20 | BA/BSc | 6 | 30% |

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 20 | MA/MSc | 1 | 5% |

| 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 20 | Total | 20 | 100% |

| 6 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 20 | ||||

| 7 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 20 | |||

| Total | 23 | 28 | 39 | 36 | 14 | ||||

| 16% | 20% | 28% | 26% | 10% | 140 |

4.2. Measuring Phase

| Types of Defects | Tot. Defected | Total % | Cumulative (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak sealing | 4196 | 0.46% | 0.46% |

| Without valve | 100303 | 11.10% | 11.56% |

| Without a top patch but folded | 34417 | 3.81% | 15.37% |

| Without a bottom patch but folded | 25141 | 2.78% | 18.15% |

| Punch out covered | 2079 | 0.23% | 18.38% |

| Shifting top patch alignment | 16334 | 1.81% | 20.18% |

| Shifting bottom patch alignment | 23975 | 2.65% | 22.84% |

| Burn on top | 2421 | 0.27% | 23.10% |

| Burn on bottom | 3202 | 0.35% | 23.46% |

| Without a top patch and not folded | 22867 | 2.53% | 25.99% |

| Without a bottom patch and not folded | 14648 | 1.62% | 27.61% |

| The top patch is not fully sealed | 37830 | 4.18% | 31.79% |

| The bottom patch is not fully sealed | 44971 | 4.97% | 36.77% |

| Not perforated | 2948 | 0.33% | 37.09% |

| With top patch but not folded | 63894 | 7.07% | 44.16% |

| With bottom patch but not folded | 101395 | 11.22% | 55.38% |

| Top and bottom without patch | 169019 | 18.70% | 74.07% |

| Jump and draw out | 234383 | 25.93% | 100.00% |

| Total | 904023 |

4.2.1. Pareto Analysis

| Types of Defects | Tot. Defected | Cumulative (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Jump and draw out | 234383 | 25.93% |

| Top and bottom without patch | 169019 | 18.70% |

| With bottom patch but not folded | 101395 | 11.22% |

| Without valve | 100303 | 11.10% |

| With top patch but not folded | 63894 | 7.07% |

| The bottom patch is not fully sealed | 44971 | 4.97% |

4.2.2. Calculation of Current Sigma Level and CP Before Improvement

| Process outcome-95% Confidence interval for defect rate, yield rate %, DPM/DPMO and sigma (Short and long term) | |||||

| Enter the number of defects | 904023 | ||||

| Enter Sample Size(N) | 19076713 | ||||

| Defect rate % | 4.73888 | Yield rate% | 95.26112 | DPM | 47388.8243 |

| Observed defect rate % (lower limit) | 4.72936 | Observed yield rate % (Upper limit) | 95.25157 | Observed DPM (lower limit) | 47293.5699 |

| observed defect rate % (Upper limit) | 4.74843 | Observed yield rate % (Lower limit) | 95.27064 | observed DPM (upper limit) | 47484.26093 |

| Short term Sigma | 3.17 | Long term Sigma | 1.98 | ||

| Observed Sigma (lower limit) | 3.17 | observed Sigma (lower limit) | 1.98 | ||

| Observed Sigma (upper limit) | 3.17 | Observed Sigma (Upper limit) | 1.98 | ||

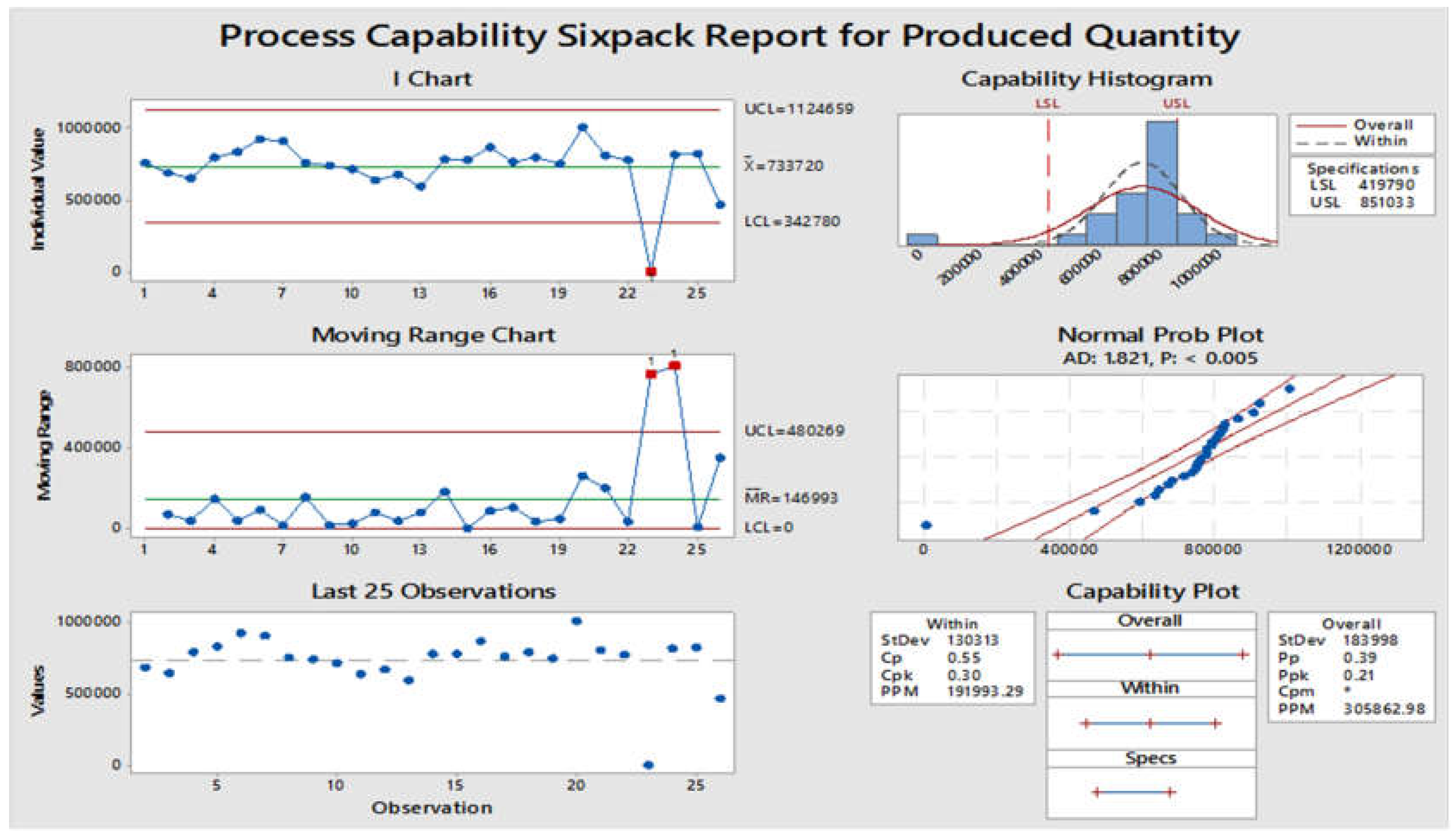

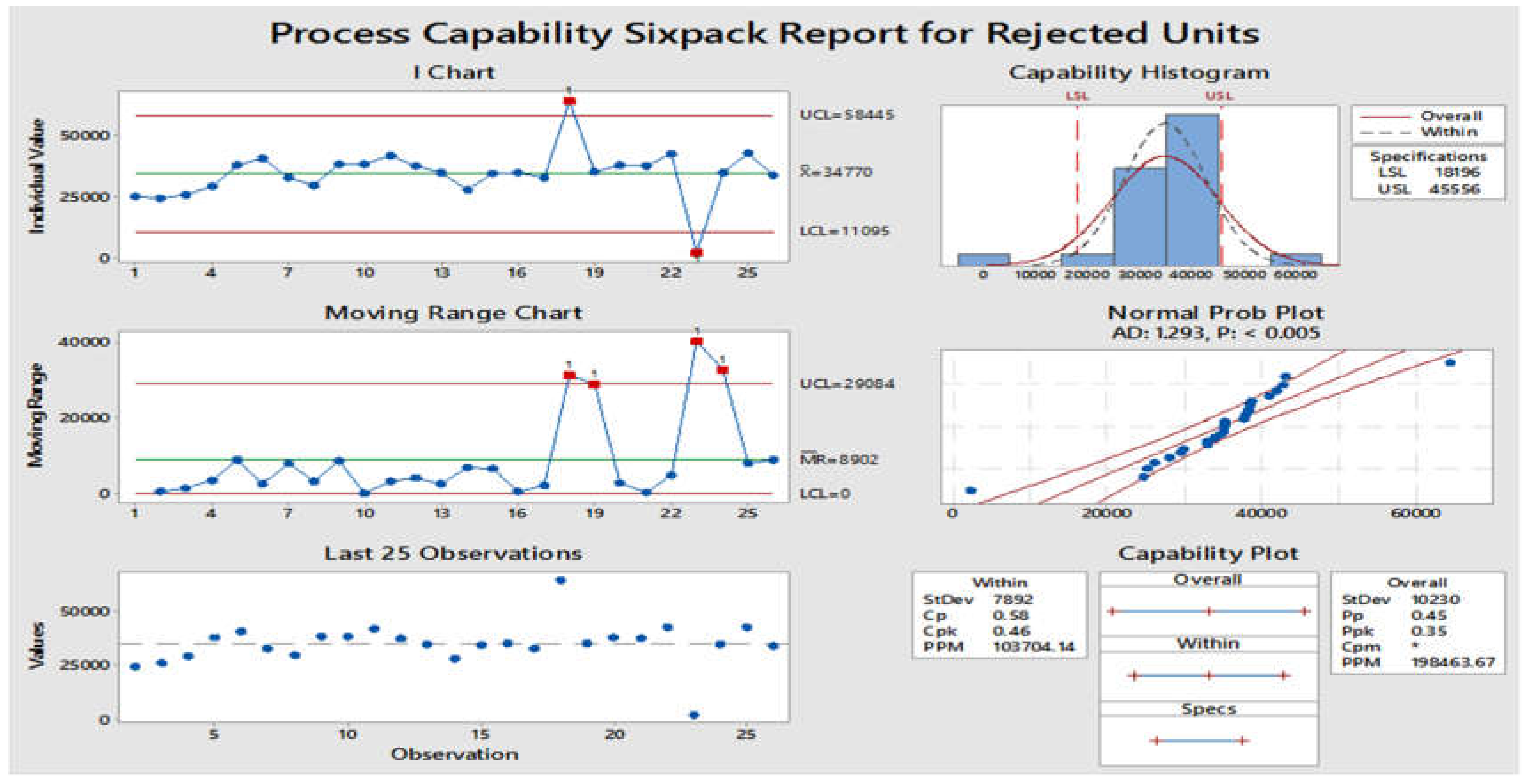

4.2.3. Key Assumptions and Interpretations of the Above Chart

4.2.4. Chart Interpretation

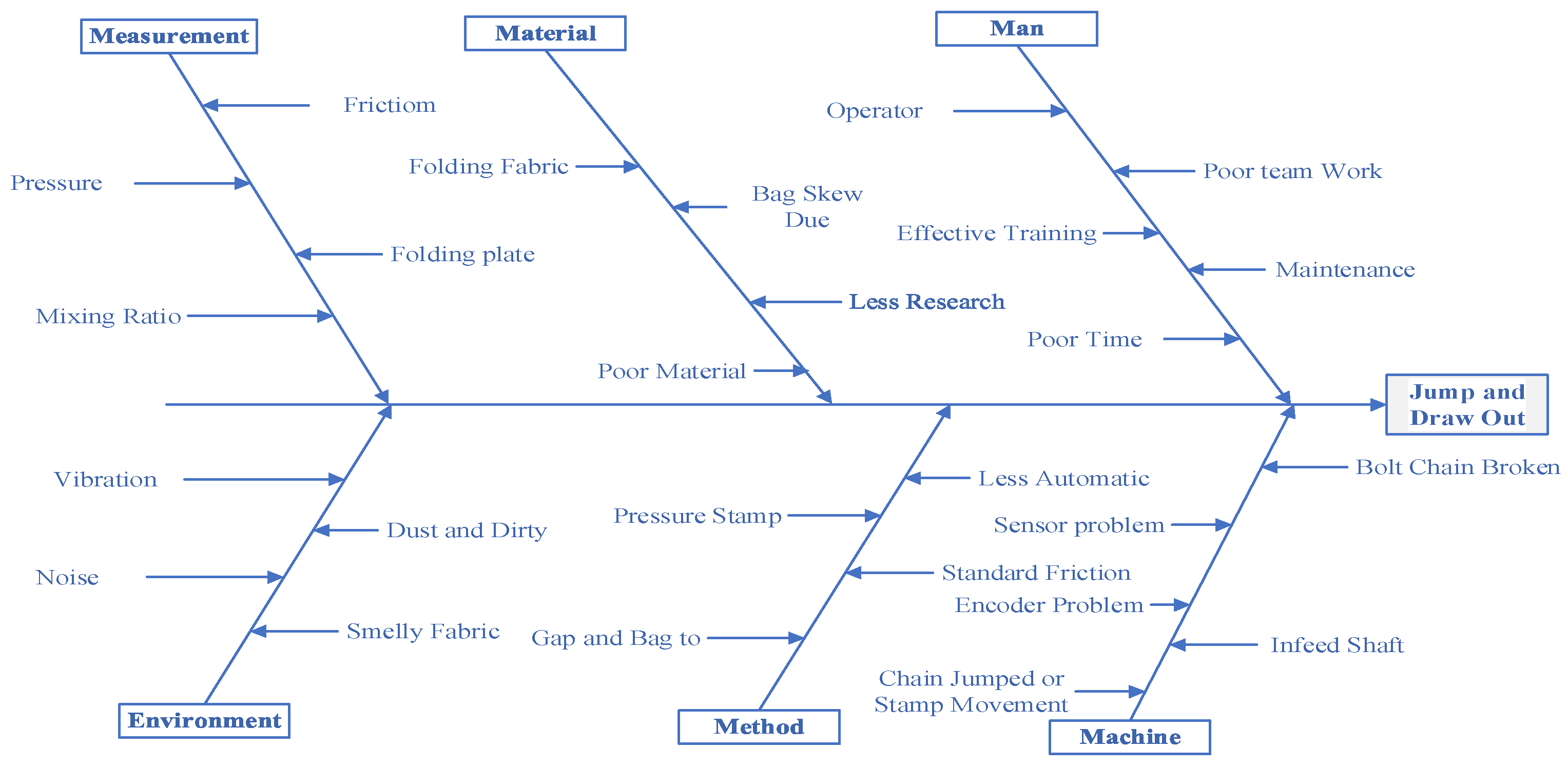

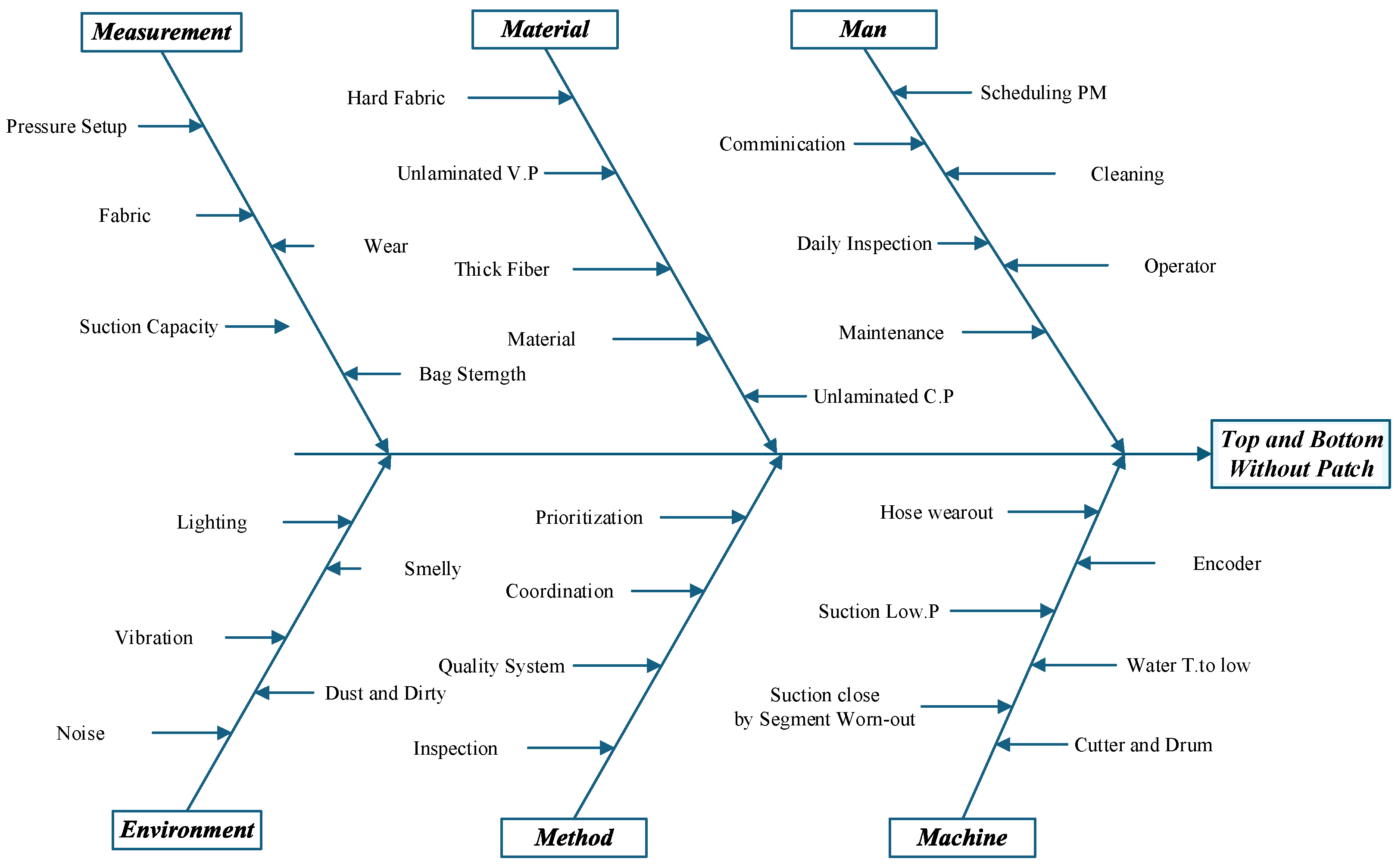

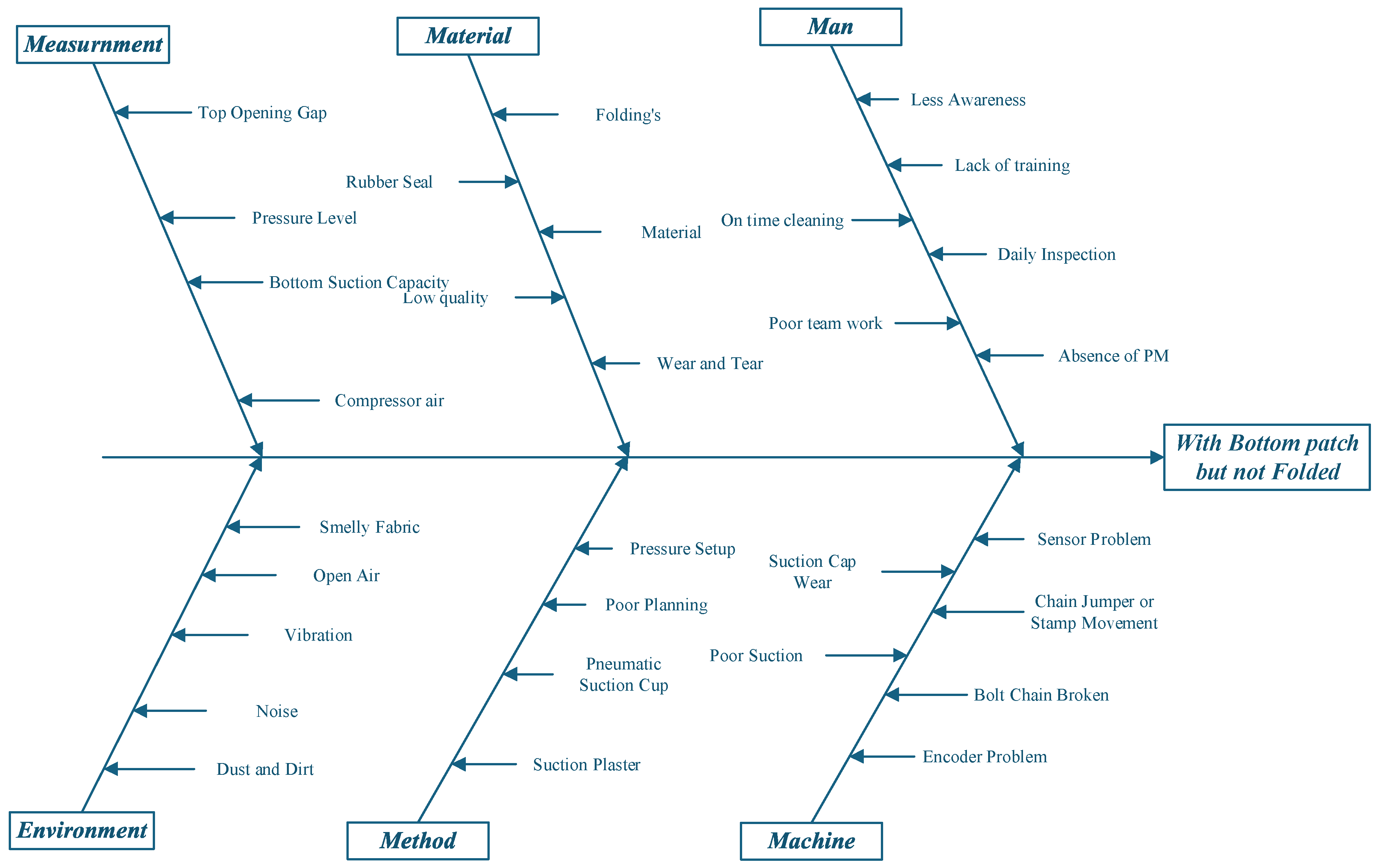

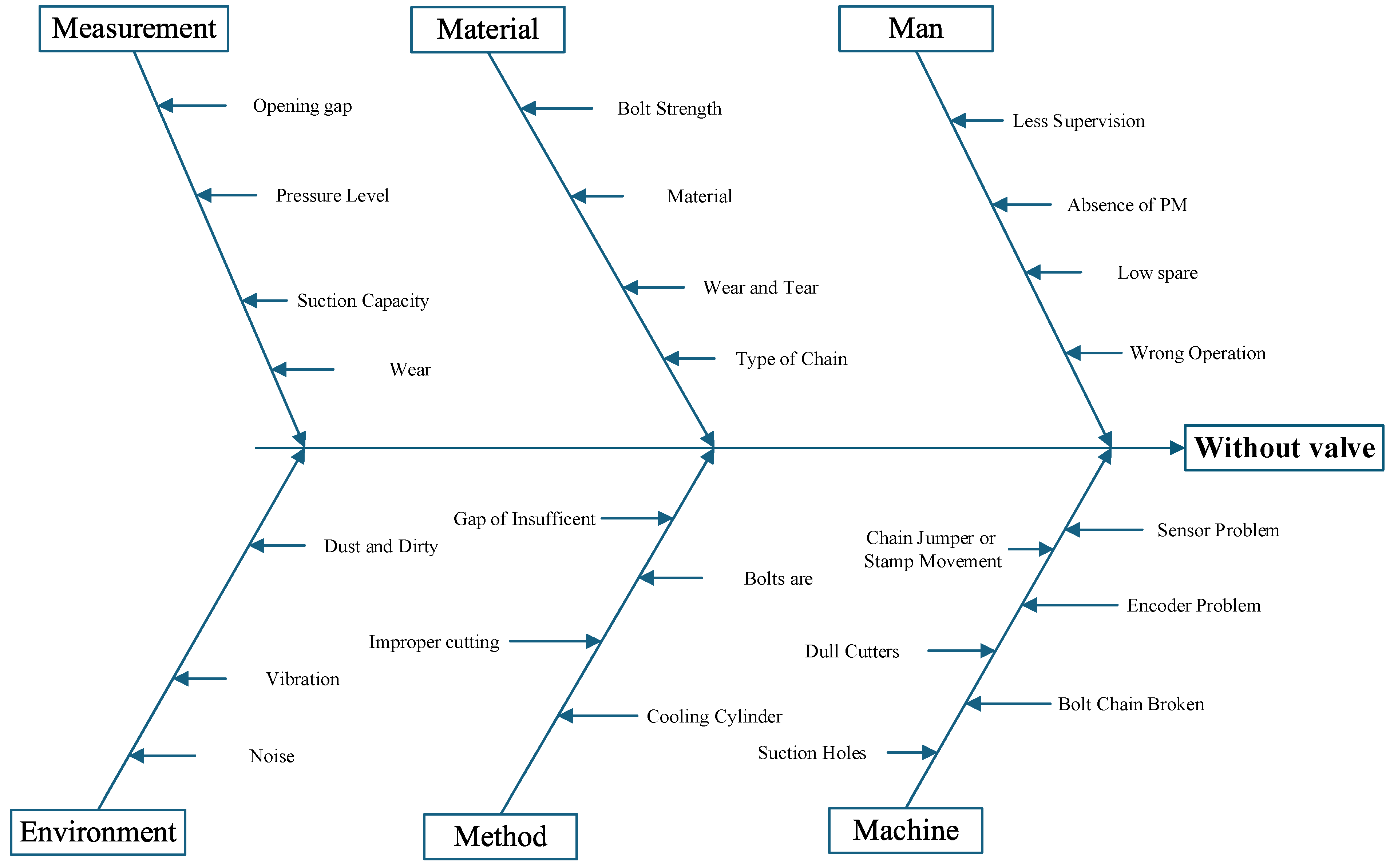

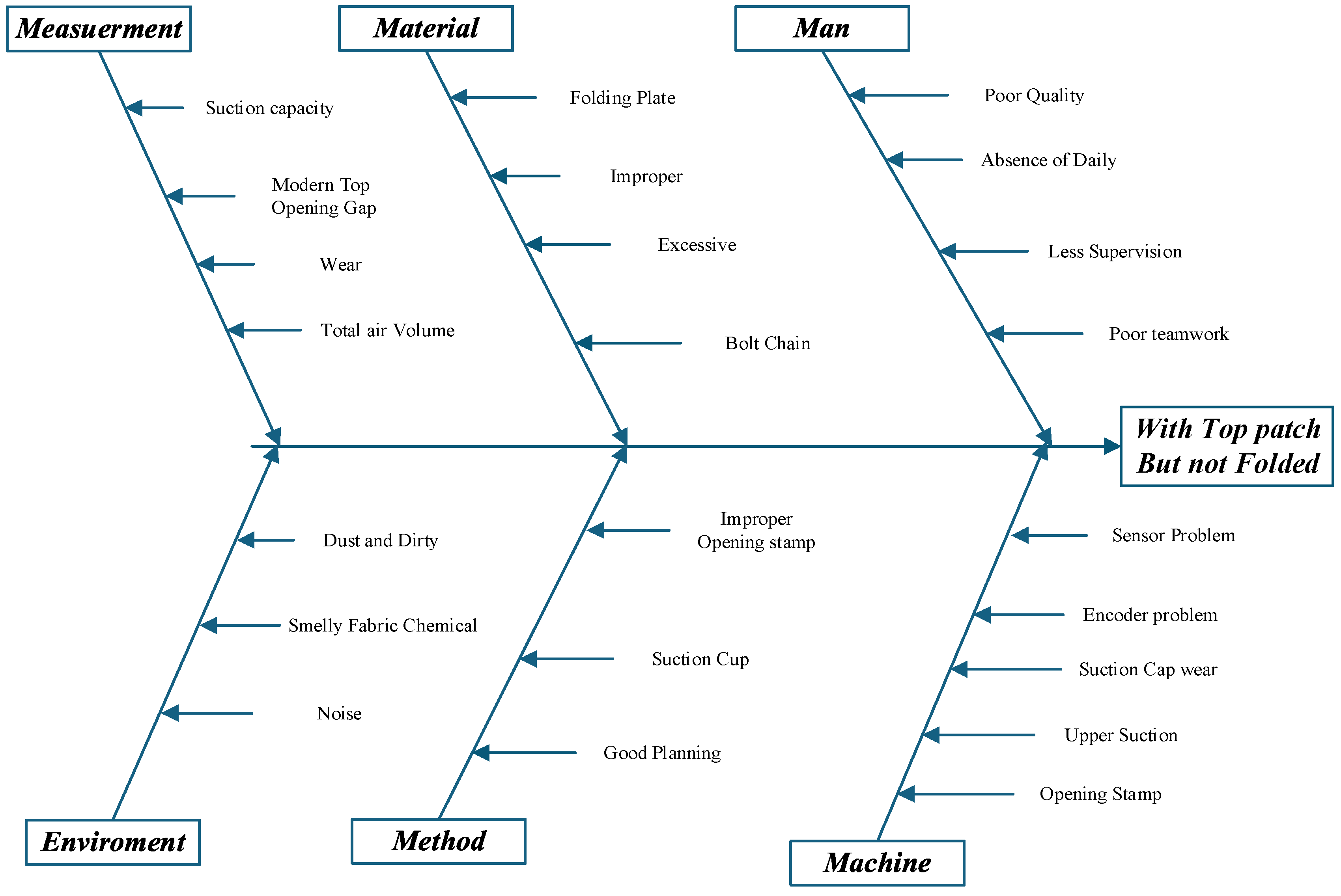

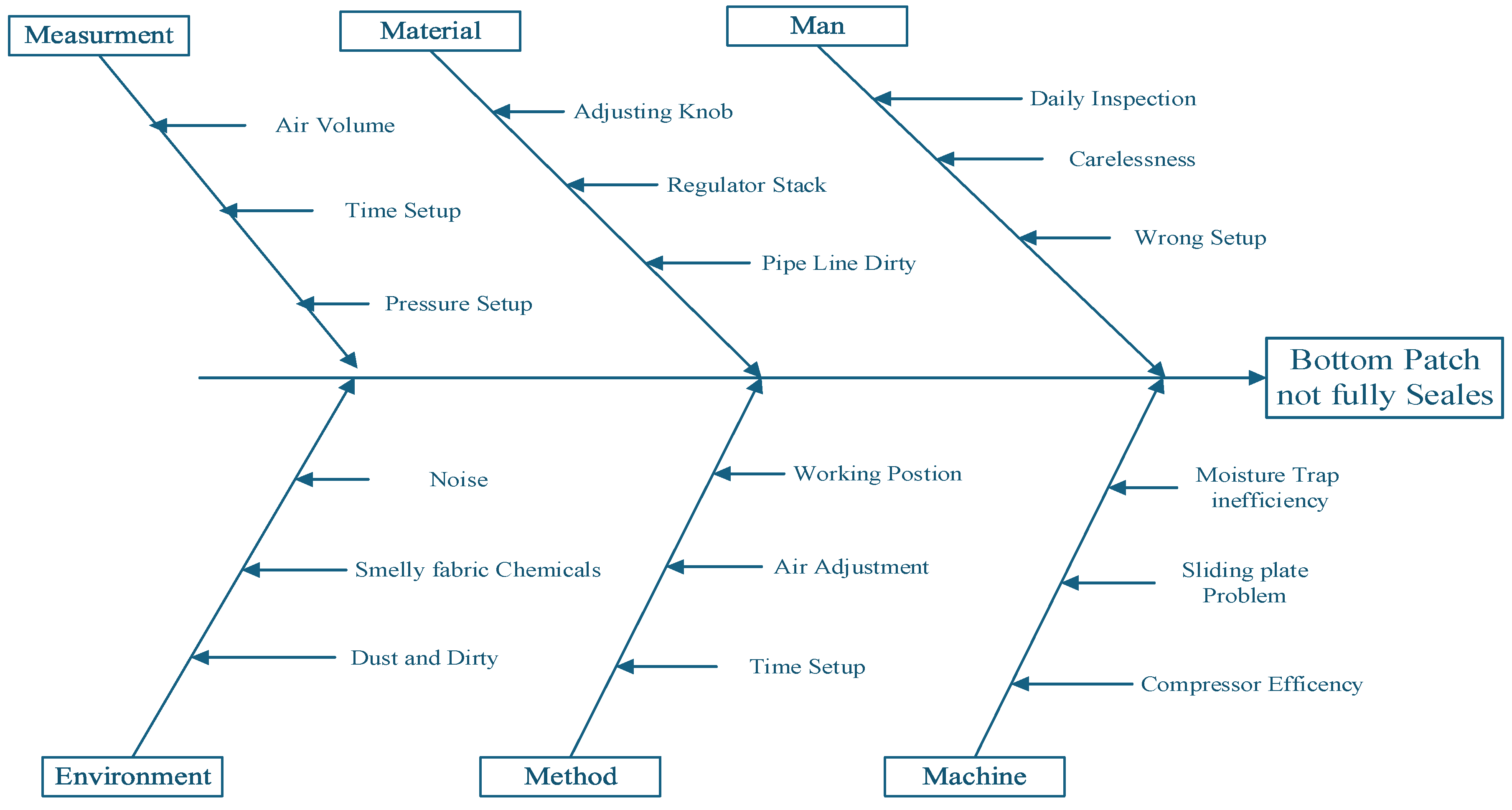

4.3. Analyses Phase

4.4. Improve Phase

4.4.1. Remedies of Jump and Draw-Out Defects

4.4.2. Remedies Top and Bottom Without Patch Defects

4.4.3. Remedies of With Bottom Patch but Not Folded Defects

4.4.4. Remedies of Without Valve Defects

4.4.5. Remedies of With Top Patch but Not Folded Defects

4.4.6. Remedies of Bottom Patch Not Fully Sealed Defects

4.4.7. Calculation of Defect Rate, DPMO, and Sigma Level After Improvement

| Process outcome-95% Confidence interval for defect rate, yield rate %, DPM/DPMO and sigma (Short and long term) | |||||

| Enter the number of defects | 200988 | ||||

| Enter Sample Size(N) | 32552007 | ||||

| Defect rate % | 0.61744 | Yield rate% | 99.38256 | DPM | 6174.3658 |

| Observed defect rate % (lower limit) | 0.61475 | Observed yield rate % (Upper limit) | 99.38525 | Observed DPM (lower limit) | 6147.51376 |

| observed defect rate % (Upper limit) | 0.62013 | Observed yield rate % (Lower limit) | 99.37987 | observed DPM (upper limit) | 6201.33447 |

| Short term Sigma | 4.00 | Long term Sigma | 2.74 | ||

| Observed Sigma (lower limit) | 4.00 | observed Sigma (lower limit) | 2.74 | ||

| Observed Sigma (upper limit) | 4.00 | Observed Sigma (Upper limit) | 2.74 | ||

4.4.8. Chart Interpretation After Improvement

4.5. Control Phase

5. Conclusions

References

- M. Q. Alsudani et al. , "RETRACTED ARTICLE: Smart logistics with IoT-based enterprise management system using global manufacturing," Journal of combinatorial optimization, vol.45, no.2, p.57, 2023.

- A. Zonnenshain and R. S. Kenett, "Quality 4.0—the challenging future of quality engineering," Quality Engineering, vol.32, no.4, pp.614-626, 2020.

- M. Colledani, T. Tolio, and A. Yemane, "Production quality improvement during manufacturing systems ramp-up," CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology, vol.23, pp.197-206, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. O. R. Okpala and M. Korzeniowska, "Understanding the relevance of quality management in agro-food product industry: From ethical considerations to assuring food hygiene quality safety standards and its associated processes," Food Reviews International, vol.39, no.4, pp.1879-1952, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Javaid, A. Haleem, R. P. Singh, and R. Suman, "Significance of Quality 4.0 towards comprehensive enhancement in the manufacturing sector," Sensors International, vol.2, p.100109, 2021.

- M. Helmold, "Total quality management (TQM)," in Virtual and Innovative Quality Management Across the Value Chain: Industry Insights, Case Studies and Best Practices: Springer, 2023, pp.27-41.

- T. A. Ibidapo, "Quality Tools and Techniques," in From Industry 4.0 to Quality 4.0: An Innovative TQM Guide for Sustainable Digital Age Businesses: Springer, 2022, pp.251-271.

- J. Singh, R. Singh, S. Singh, H. Vasudev, and S. Kumar, "Reducing scrap due to missed operations and machining defects in 90PS pistons," International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), vol.17, no.5, pp.2527-2539, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, D. Zhuang, and W. Shen, "The impact of quality management practices on manufacturing performance: an empirical study based on system theory," Soft Computing, pp.1-16, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Le, Y. Li, and F. Ren, "Does air quality improvement promote increased enterprise productivity? Based on the spatial spillover effect of 242 cities in China," Frontiers in Public Health, vol.10, p.1050971, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Psarommatis, J. Sousa, J. P. Mendonça, and D. Kiritsis, "Zero-defect manufacturing the approach for higher manufacturing sustainability in the era of industry 4.0: a position paper," International Journal of Production Research, vol.60, no.1, pp.73-91, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Palange and P. Dhatrak, "Lean manufacturing a vital tool to enhance productivity in manufacturing," Materials Today: Proceedings, vol.46, pp.729-736, 2021.

- J. Shi, "In-process quality improvement: Concepts, methodologies, and applications," IISE transactions, vol.55, no.1, pp.2-21, 2023.

- P. De Giovanni and G. Zaccour, "A survey of dynamic product quality models," European Journal of Operational Research, vol.307, no.3, pp.991-1007, 2023.

- F. Psarommatis and D. Kiritsis, "A hybrid Decision Support System for automating decision making in the event of defects in the era of Zero Defect Manufacturing," Journal of Industrial Information Integration, vol.26, p.100263, 2022.

- S. Azimpoor and S. Taghipour, "Joint inspection and product quality optimization for a system with delayed failure," Reliability Engineering & System Safety, vol.215, p.107793, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Tsarouhas, "Reliability, availability and maintainability analysis of a bag production industry based on the Six Sigma DMAIC approach," International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, vol.12, no.2, pp.237-263, 2021.

- S. Shingo, Zero quality control: Source inspection and the poka-yoke system. Routledge, 2021.

- S. Mandal, S. K. Kalakandan, and A. Sugumar, "Effective packaging and handling of food grains for quality and safety management," in Unit Operations in Food Grain Processing: Elsevier, 2024, pp.513-546.

- S. Bhat, J. Antony, M. Maalouf, G. EV, and S. Salah, "Applications of Six Sigma for service quality enhancement in the UAE: a multiple case study analysis and lessons learned," International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, vol.14, no.7, pp.1492-1517, 2023.

- A. Rosa et al. , "Assessing Lean Six Sigma and quality performance improvement in Italian public healthcare organizations: a validated scale," The TQM Journal, vol.36, no.9, pp.392-412, 2024.

- S. Rath and R. Agrawal, "Prediction of novel operating parameters using Six Sigma: A study in the steel making process," Quality Management Journal, vol.30, no.3, pp.187-201, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Joghee and R. Varghese, "Application of Six Sigma methodology in the analysis of variance: process shift versus inflation coefficient," International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 2024.

- S. Qayyum, F. Ullah, F. Al-Turjman, and M. Mojtahedi, "Managing smart cities through Six Sigma DMADICV method: A review-based conceptual framework," Sustainable Cities and Society, vol.72, p.103022, 2021.

- I. C. Pérez-Balboa and S. O. Caballero-Morales, "Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control (DMAIC)," in Lean Manufacturing in Latin America: Concepts, Methodologies and Applications: Springer, 2024, pp.333-352.

- M. Milosevic, M. Djapan, R. D’Amato, N. Ungureanu, and A. Ruggiero, "Sustainability of the production process by applying lean manufacturing through the PDCA cycle–a case study in the machinery industry," in Advances in Manufacturing Engineering and Materials II: Proceedings of the International Conference on Manufacturing Engineering and Materials (ICMEM 2020), 21–25 June 2021, Nový Smokovec, Slovakia, 2021: Springer, pp.199-211.

- M. Colledani et al. , "Design and management of manufacturing systems for production quality," Cirp Annals, vol.63, no.2, pp.773-796, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Gamal Aboelmaged, "Six Sigma quality: a structured review and implications for future research," International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, vol.27, no.3, pp.268-317, 2010.

- J. E. Brady and T. T. Allen, "Six Sigma literature: a review and agenda for future research," Quality and Reliability Engineering International, vol.22, no.3, pp.335-367, 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. Bazrkar, S. Iranzadeh, and N. Feghhi Farahmand, "Total quality model for aligning organization strategy, improving performance, and improving customer satisfaction by using an approach based on a combination of balanced scorecard and lean six sigma," Cogent Business & Management, vol.4, no.1, p.1390818, 2017.

- J. S. Oakland, Total quality management and operational excellence: text with cases. Routledge, 2014.

- A. Permana, H. H. Purba, and N. D. Rizkiyah, "A systematic literature review of Total Quality Management (TQM) implementation in the organization," International Journal of Production Management and Engineering, vol.9, no.1, pp.25-36, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Collinson, P. Edwards, and C. Rees, Involving employees in total quality management: employee attitudes and organizational context in unionized environments. Department of Trade and Industry London, 1998.

- J. Huang, M. Irfan, S. S. Fatima, and R. M. Shahid, "The role of Lean Six Sigma in driving sustainable manufacturing practices: an analysis of the relationship between Lean Six Sigma principles, data-driven decision making, and environmental performance," Frontiers in Environmental Science, vol.11, p.1184488, 2023.

- A. D. Makwana and G. S. Patange, "A methodical literature review on application of Lean & Six Sigma in various industries," Australian Journal of Mechanical Engineering, vol.19, no.1, pp.107-121, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Joghee, "Six Sigma quality evaluation of life test data based on Weibull distribution," International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, vol.38, no.4, pp.1005-1022, 2021.

- S. Kalaivani and J. Ravichandran, "Performance evaluation of exponential distribution using Six Sigma-based tail probabilities," Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, vol.50, no.11, pp.3125-3145, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Hollingshed, "Standardizing Six Sigma Green Belt training: identification of the most frequently used measure phase DMAIC tools," International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, vol.13, no.2, pp.276-294, 2022.

- N. Paneerselvam, N. A. Muhammad, A. M. Azhan, and N. Muhammad, "Analyzing critical success factors in Lean Six Sigma training," International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 2024.

- V. Gupta, R. Jain, M. Meena, and G. Dangayach, "Six-sigma application in tire-manufacturing company: a case study," Journal of Industrial Engineering International, vol.14, pp.511-520, 2018.

- M. H. Sajjad et al. , "Waste reduction of polypropylene bag manufacturing process using Six Sigma DMAIC approach: A case study," Cogent Engineering, vol.8, no.1, p.1896419, 2021.

- M. J. Ershadi, O. Qhanadi Taghizadeh, and S. M. Hadji Molana, "Selection and performance estimation of Green Lean Six Sigma Projects: a hybrid approach of technology readiness level, data envelopment analysis, and ANFIS," Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol.28, pp.29394-29411, 2021.

- D. A. Desai, P. Kotadiya, N. Makwana, and S. Patel, "Curbing variations in packaging process through Six Sigma way in a large-scale food-processing industry," Journal of Industrial Engineering International, vol.11, pp.119-129, 2015.

- M. Hu and J. Pieprzak, "Using axiomatic design to improve conceptual design robustness in Design for Six Sigma (DFSS) methodology," International Journal of Six Sigma and Competitive Advantage, vol.1, no.3, pp.245-262, 2005.

- B. Rahardjo, F. -K. Wang, S. -C. Lo, and T. -H. Chu, "A Sustainable Innovation Framework Based on Lean Six Sigma and Industry 5.0," Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, vol.49, no.5, pp.7625-7642, 2024.

- Y. Y. Liao, E. Soltani, A. Iqbal, and R. van der Meer, "The utility of performance review systems: A total quality management perspective," Strategic Change, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Lloréns Montes, A. Verdú Jover, and L. Miguel Molina Fernández, "Factors affecting the relationship between total quality management and organizational performance," International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, vol.20, no.2, pp.189-209, 2003.

- S. P. Goffnett, "Leadership, goal acceptance, and QMS conformance readiness: exploring the mediating effects of audit team cohesion," Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, vol.31, no.1-2, pp.43-67, 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar and R. Sharma, "Leadership styles and their relationship with TQM focus for Indian firms: An empirical investigation," International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, vol.67, no.6, pp.1063-1088, 2018.

- L. Gaikwad and V. Sunnapwar, "An integrated Lean, Green and Six Sigma strategies: a systematic literature review and directions for future research," The TQM Journal, vol.32, no.2, pp.201-225, 2020.

- J. A. González Ruiz, N. Blanco, and M. Gascons, "Enhancing process performance for composite padel racket manufacture using Six Sigma-DMAIC and VSM synergetic support," Cogent Engineering, vol.9, no.1, p.2084982, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Schmitt, J. Bönig, T. Borggräfe, G. Beitinger, and J. Deuse, "Predictive model-based quality inspection using Machine Learning and Edge Cloud Computing," Advanced engineering informatics, vol.45, p.101101, 2020.

- M. S. Kaswan and R. Rathi, "Green Lean Six Sigma for sustainable development: Integration and framework," Environmental impact assessment review, vol.83, p.106396, 2020.

- R. Rathi, M. S. Kaswan, J. A. Garza-Reyes, J. Antony, and J. Cross, "Green Lean Six Sigma for improving manufacturing sustainability: Framework development and validation," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol.345, p.131130, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Elkateb, A. Métwalli, A. Shendy, and A. E. Abu-Elanien, "Machine learning and IoT–Based predictive maintenance approach for industrial applications," Alexandria Engineering Journal, vol.88, pp.298-309, 2024.

- Y. Trakulsunti, J. Antony, R. Edgeman, B. Cudney, M. Dempsey, and A. Brennan, "Reducing pharmacy medication errors using Lean Six Sigma: A Thai hospital case study," Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, vol.33, no.5-6, pp.664-682, 2022.

- S. Bhat, E. Gijo, J. Antony, and J. Cross, "Strategies for successful deployment and sustainment of Lean Six Sigma in the healthcare sector in India: a multi-level perspective," The TQM Journal, vol.35, no.2, pp.414-445, 2023.

- G. D. Sharma, S. Kraus, M. Srivastava, R. Chopra, and A. Kallmuenzer, "The changing role of innovation for crisis management in times of COVID-19: An integrative literature review," Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, vol.7, no.4, p.100281, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Hacklin, Management of convergence in innovation: strategies and capabilities for value creation beyond blurring industry boundaries. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- A. M. Evans et al. , "Dissemination and analysis of the quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) practices of LC–MS-based untargeted metabolomics practitioners," Metabolomics, vol.16, no.10, p.113, 2020. 10.1007/s11306-020-01728-5.

- L. K. Toke and S. D. Kalpande, "Total quality management in small and medium enterprises: An overview in Indian context," Quality Management Journal, vol.27, no.3, pp.159-175, 2020.

- J. Abbas, "Impact of total quality management on corporate green performance through the mediating role of corporate social responsibility," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol.242, p.118458, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Abbas, "Impact of total quality management on corporate sustainability through the mediating effect of knowledge management," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol.244, p.118806, 2020.

- A. Syafarudin, "The effect of product quality on customer satisfaction implications on customer loyalty in the era Covid-19," Ilomata International Journal of Tax and Accounting, vol.2, no.1, pp.71-83, 2021.

- P. Kwiatek, Z. Morgan, and M. Thanasi-Boçe, "The role of relationship quality and loyalty programs in building customer loyalty," Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, vol.35, no.11, pp.1645-1657, 2020.

- N. Haber, M. Fargnoli, and T. Sakao, "Integrating QFD for product-service systems with the Kano model and fuzzy AHP," Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, vol.31, no.9-10, pp.929-954, 2020.

- N. M. Duc, D. T. P. Chi, N. H. Tien, and T. T. K. Hong, "Factors affecting customer satisfaction at Vietinbank in Vietnam," International Journal of Research in Human Resource Management, vol.3, no.2, pp.62-70, 2021.

- F. Pakdil and F. Pakdil, "Overview of quality and Six Sigma," Six Sigma for Students: A Problem-Solving Methodology, pp.3-40, 2020.

- E. Gijo, J. Scaria, and J. Antony, "Application of Six Sigma methodology to reduce defects of a grinding process," Quality and reliability Engineering International, vol.27, no.8, pp.1221-1234, 2011.

- S. Gupta, S. Modgil, and A. Gunasekaran, "Big data in Lean Six Sigma: a review and further research directions," International Journal of Production Research, vol.58, no.3, pp.947-969, 2020.

- M. Zhang, W. Wang, T. N. Goh, and Z. He, "Comprehensive Six Sigma application: a case study," Production Planning & Control, vol.26, no.3, pp.219-234, 2015.

- I. T. B. Widiwati, S. D. Liman, and F. Nurprihatin, "The implementation of Lean Six Sigma approach to minimize waste at a food manufacturing industry," Journal of Engineering Research, 2024.

- A. Mittal, P. Gupta, V. Kumar, A. Al Owad, S. Mahlawat, and S. Singh, "The performance improvement analysis using Six Sigma DMAIC methodology: A case study on the Indian manufacturing company," Heliyon, vol.9, no.3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. L. Lizarelli and D. H. Alliprandini, "Comparative analysis of Lean and Six Sigma improvement projects: performance, changes, investment, time and complexity," Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, vol.31, no.3-4, pp.407-428, 2020.

- N. Nandakumar, P. Saleeshya, and P. Harikumar, "Bottleneck identification and process improvement by lean six sigma DMAIC methodology," Materials Today: Proceedings, vol.24, pp.1217-1224, 2020.

- F. Tsung and K. Wang, "Six Sigma," in Springer Handbook of Engineering Statistics: Springer, 2023, pp.239-259.

- B. John and R. S. Kadadevaramath, "Improving the resolution time performance of an application support process using Six Sigma methodology," International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, vol.11, no.4, pp.663-686, 2020.

- E. Gijo, S. Bhat, and N. Jnanesh, "Application of Six Sigma methodology in a small-scale foundry industry," International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, vol.5, no.2, pp.193-211, 2014.

- K. C. Arredondo-Soto, J. Blanco-Fernández, M. A. Miranda-Ackerman, M. M. Solís-Quinteros, A. Realyvasquez-Vargas, and J. L. García-Alcaraz, "A plan-do-check-act based process improvement intervention for quality improvement," IEEE Access, vol.9, pp.132779-132790, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Realyvásquez Vargas, J. L. García Alcaraz, S. Satapathy, D. A. Coraza, and Y. Báez López, "The PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) Cycle," in Lean Manufacturing in Latin America: Concepts, Methodologies and Applications: Springer, 2024, pp.409-437.

- J. Trippner-Hrabi, J. Chądzyński, and A. Kam, "Enhancing Goal Achievement During Remote Work in Public Utility Services: Unveiling the Significance of the PDCA Deming Cycle," in Ethics and Innovation in Public Administration: Springer, 2024, pp.299-311.

- M. Gupta, A. Digalwar, A. Gupta, and A. Goyal, "Integrating Theory of Constraints, Lean and Six Sigma: a framework development and its application," Production Planning & Control, vol.35, no.3, pp.238-261, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Surjit, G. Indu, B. Anusri Mahalakshmi, and M. Shubha Shree, "Six Sigma Approach: A Pathway to Zero Waste Sustainable Apparel Industry," in Zero Waste Sustainable Apparel Industry: Springer, 2024, pp.25-41.

- P. Patel and D. Desai, "Implementation of Six Sigma Methodology in Indian Plastic Manufacturing Industry-A Case Study," Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series C, pp.1-23, 2024.

- A. Sharma, A. Chouhan, L. Pavithran, U. Chadha, and S. K. Selvaraj, "Implementation of LSS framework in automotive component manufacturing: a review, current scenario, and future directions," Materials Today: Proceedings, vol.46, pp.7815-7824, 2021.

- P.-S. Chen, J. C. -M. Chen, W. -T. Huang, and H. -T. Chen, "Using the Six Sigma DMAIC method to improve procurement: a case study," Engineering Management Journal, vol.35, no.1, pp.70-83, 2023.

- M. Kharub, S. Kattekola, and S. K. Pendyala, "80/20 your organization using AHP for quantitative decision making," Materials Today: Proceedings, vol.56, pp.2437-2442, 2022.

- R. Kumar, K. Singh, and S. K. Jain, "Agile manufacturing: a literature review and Pareto analysis," International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, vol.37, no.2, pp.207-222, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Kwilinski and M. Kardas, "Enhancing process stability and quality management: A comprehensive analysis of process capability indices," Virtual Economics, vol.6, no.4, pp.73-92, 2023.

- E. K. Saied, A. Y. Besees, A. Wazeer, and A. A. Abd-Eltwab, "Process Performance Analysis In Cement Industry," International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, vol.9, no.06, pp.844-860, 2020.

- Y. Y. Tesfay and Y. Y. Tesfay, "Process capability analysis," Developing structured procedural and methodological engineering designs: applied industrial engineering tools, pp.187-209, 2021.

- P. L. Ramos, A. P. Silva Figueiredo, D. Carvalho do Nascimento, F. Moala, and E. Flores, "Beyond Regular SPC: Bridging the C pk Capability Index for (a) Symmetric Data," Annals of Data Science, pp.1-27, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Agustiady and E. A. Cudney, "TPM and Sigma," in Total Productive Maintenance: CRC Press, 2024, pp.16-49.

- N. P. d. Rocha et al. , "Statistical process control of manufacturing tablets for antiretroviral therapy," Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, vol.59, p. e22099, 2023.

- H. U. Pawar, S. K. Bagga, and D. K. Dubey, "Investigation of production parameters for process capability analysis: A case study," Materials Today: Proceedings, vol.43, pp.196-202, 2021.

- Q. Xiao and G. Li, "Application and challenges of statistical process control in radiation therapy quality assurance," International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, vol.118, no.1, pp.295-305, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Shandilya, J. Arora, and V. Kalluri, "To study the comparison and effect of Six Sigma and Red Bin Analysis in Indian manufacturing industries," The TQM Journal, vol.35, no.7, pp.1658-1685, 2023. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).