Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Argumentation of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Theoretical Justification of the Possibilities for Utilizing Local Resources Through Rural Tourism Activities

- Carpentry – (common to all three areas) – involves the construction of houses and household annexes using only wood;

- Joinery (specific to Humor and Dorna Areas) – involves making door and window frames as well as furniture using wood;

- Cooperage – (common to all three areas) – involves the making of wooden containers to store liquids, cheese, and preserved fruits;

- Blacksmithing (specific to Humor and Dorna Areas) – involves the processing of iron to produce various objects and tools;

- Pottery (specific to Humor Area only) – involves processing clay (especially clay) to make household items;

- Spinning and Weaving – (common to all three areas) – involves making fabrics for clothing and decorative textile items, using flax, hemp, and wool;

- Sewing (specific to Humor and Dorna Areas) – the traditional technique is still preserved in 2025;

- Leatherwork or processing of skins and furs (common to all three areas) – involves using sheep and cattle skins to create clothing items known as “cojoace”;

- Roofing (specific to Humor and Dorna Areas) – involves covering houses, generally using spruce wood;

- Rope-making (specific to Humor Area) – the craft of making ropes from hemp, which were later used to tie cattle;

- Egg Decorating or Dyeing (common to all three areas) – this craft is especially practiced in the Câmpulung Moldovenesc Area in Romania;

- Folk Musical Instruments (specific to Câmpulung Moldovenesc and Dorna Areas) – involves the making of folk musical instruments mostly from resonant wood such as fir and spruce;

- Making of traditional shoes and boots (common to all three areas) – involves creating footwear typical of the 20th century rural Romania, using pig or calf leather;

- Belt-making (specific to Câmpulung Moldovenesc Area) – involves mounting leather ornaments made by specialized women, as well as making and repairing harnesses for horses, bridles, and whips;

- Vegetable Dyeing (specific to Dorna Area) – involves dyeing flax, hemp, and wool threads using plant-based dyes extracted from plant roots, rhizomes, stems, leaves, or flowers;

- Horn Processing (specific to Dorna Area) – involves making objects from deer or cattle horns, which was once practiced in the Bistrița Gold Valley (especially in Cârlibaba), and belonged to the Huțul horse people settled there in the 18th century. The objects, whether decorated or not, had various uses, such as horns for blowing, measuring, or storing gunpowder.

3.2. Analysis of the Tourist Offer in the Humor Area, Câmpulung Moldovenesc Area, and Dorna Area

3.3. Analysis of Tourist Demand in the Humor, Câmpulung Moldovenesc, and Dorna Areas

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGehee, N.G.; Andereck, K.L. Factors Predicting Rural Residents’ Support of Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 131–140. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.mmediu.ro/app/webroot/uploads/files/Strategia%20Nationala%20de%20Dezvoltare%20%20a%20Turismului%202023-2035%281%29.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Muresan, I.C.; Oroian, C.F.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Porutiu, A.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Todea, A.; Lile, R. Local residents’ attitude toward sustainable rural tourism development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 100. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.E.; Reid, D.G. Community integration: Island tourism in Peru. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 113–139.

- Andriotis, K. Local authorities in Crete and the development of tourism. J. Tour. Stud. 2002, 13, 53–62.

- Brida, J.G.; Osti, L.; Faccioli, M. Residents’ perception and attitudes towards tourism impacts, a case study of the small rural community of Folgaria (Trentino–Italy). Benchmarking Int. J. 2011, 18, 359–385.

- Hanafiah, M.H.; Jamaluddin, M.R.; Zulkifly, M.I. Local Community Attitude and Support towards Tourism Development in Tioman Island, Malaysia. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 792–800. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Pour, S.A. Effects of economic, social and environmental factors of tourism on improvement of Perceptions of local population about tourism: Kashan touristic city, Iran. Int. J. AYER. 2014, 4, 72–84.

- Aguiló, E.; Roselló, J. Host Community perceptions. A cluster analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 925–941.

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Porras-Bueno, N.; de los Ángeles Plaza-Mejía, M. Explaining residents’ attitudes to tourism. Is a universal model possible? Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 460–480.

- Stetic, S. Specific features of rural tourism destinations management. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. Spec. Issue 2012, 1, 131–137.

- Neumeier, S.; Pollermann, K. Rural Tourism as Promoter of Rural Development—Prospects and Limitations: Case Study Findings From A Pilot Projectpromoting Village Tourism. Eur. Countrys. 2014, 6, 270–296. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Choi, B.R. Rural Tourism: Does It Matter for Sustainable Farmers’ Income? Sustainability 2021, 13, 10440.

- He, Y.; Gao, X.; Wu, R.; Wang, Y.; Choi, B.-R. How Does Sustainable Rural Tourism Cause Rural Community Development? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13516.

- Mihai, C.; Ulman, S.-R.; David, M. New Assessment of Development Status among the People Living in Rural Areas: an Alternative Approach for Rural Vitality. Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2019, 66(2). 167-192.

- Ulman, S.-R.; Mihai, C.; Cautisanu, C.; Bruma, I.-S.; Coca, O.; Stefan, G. Environmental Performance in EU Countries from the Perspective of Its Relation to Human and Economic Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18(23). [CrossRef]

- Ulman, S.-R.; Mihai, C.; Cautisanu, C. Original Inconsistencies in the Dynamics of Sustainable Development Dimensions in Central and Eastern European Countries. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30(3), 2779-2798. [CrossRef]

- Iacobuta, A.-O.; Mursa, G.-C.; Mihai, C.; Cautisanu, C.; Cismas, L.-M. Institutions and sustainable development: a cross-country analysis. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2019, 18(2A), 628-646. WOS:000498305700015.

- Ulman, S.-R.; Isan, V.; Mihai, C.; Ifrim, M. The responsiveness of the rural area to the related-decreasing poverty measures of the sustainable development policy: the case of north-east region of Romania. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2018, 17(2B), 780-805. WOS:000450699300014.

- Ulman, S.-R.; Mihai, C.; Cautisanu, C. Peculiarities of the Relation between Human and Environmental Wellbeing in Different Stages of National Development. Sustainability 2020, 12(19). [CrossRef]

- Mihai, C.; Hatmanu, M. Particular Aspects Of Consumer Profile Of The Public Goods Generated In A Region With Extensive Agricultural Activities: The Case Of Dorna Valley Area Of Romania. EURINT, Centre for European Studies, Al. I. Cuza University 2018, 5, 272-288. WOS:000459250600016.

- Available online: https://op.europa.eu/ro/publication-detail/-/publication/6f6546d4-a9a9-458d-8878-b7232e3a6b78 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Available online: https://www.usab-tm.ro/utilizatori/universitate/file/doctorat/sustinere_td/2019/isac%20ecaterina/Rezumatul%20tezei.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Popescu, G.; Popescu, C.A.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Pet, E.; Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R. Sustainability through Rural Tourism in Moieciu Area-Development Analysis and Future Proposals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4221. [CrossRef]

- Frochot, I. A benefit segmentation of tourists in rural areas: A Scottish perspective. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 335–346. [CrossRef]

- Sharpley R. Rural tourism and the challenge of tourism diversification: The case of Cyprus, Tour. Management. 2002, 23, 233-244. [CrossRef]

- Panyik, E.; Costa, C.; Ratz, T. Implementing integrated rural tourism: An event-based approach. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1352–1363. [CrossRef]

- Gogonea, R.-M.; Baltalunga, A.A.; Nedelcu, A.; Dumitrescu, D. Tourism Pressure at the Regional Level in the Context of Sustainable Development in Romania. Sustainability 2017, 9, 698. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pfister, R.E. Residents attitudes toward tourism and perceived personal benefits in a rural community. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 84–93. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C. A.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Croitoru, I.M.; Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R. Rural Tourism in Mountain Rural Comunities-Possible Direction/Strategies: Case Study Mountain Area from Bihor County. Sustainability 2024, 16(3), 1127. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.adrnordest.ro/regiunea-nord-est/localizare-istorica-si-geografica/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Lupi, C.; Giaccio, V.; Mastronardi, L.; Giannelli, A.; Scardera, A. Exploring the features of agritourism and its contribution to rural development in Italy. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 383–390. [CrossRef]

- Marin, D. Study on the economic impact of tourism and of agrotourism on local communities. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 47, 160–163.

- Adamowicz, M.; Zwoli’ nska-Ligaj, M. The “Smart Village” as a Way to Achieve Sustainable Development in Rural Areas of Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6503. [CrossRef]

- Su, L., & Swanson, S. R. The effect of personal benefits from, and support of, tourism development: The role of relational quality and quality-of-life. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28(3), 433–454. [CrossRef]

- Saghin, D., Lăzărescu, L.-M., Diacon, L. D., & Grosu, M. Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism: A Decisive Variable in Stimulating Entrepreneurial Intentions and Activities in Tourism in the Mountainous Rural Area of the North-East Region of Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14(16), 10282. [CrossRef]

- Calina, A.; Calina, J.; Iancu, T. Research regarding the implementation, development and impact of Agritourism on Romania’s rural areas between 1990 and 2015. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 157–168. [CrossRef]

- Karabati, S.; Dogan, E.; Pinar, M.; Celik, M.L. Socio-Economic Effects of Agri-Tourism on Local Communities in Turkey: The Case of Aglasun. Intl. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2009, 10, 129–142. [CrossRef]

- Stucki, E. Le developpement équilibré du monde rurale en Europe occidentale. Sauvegarde Nat. 1992, 58, 1–64.

- Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Adamov, T.; Mateoc-Sîrb, N. Agritourism—A Business Reality of the Moment for Romanian Rural Area’s Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6313. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; van Es, J.C. Factors for success in rural tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 132–138. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [CrossRef]

- Nemirschi, N.; Craciun, A. Entrepreneurship and tourism development in rural areas: Case of Romania. Rom. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2014, 5, 138–143.

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A. The agritourism as a means of sustainable development for rural communities: A research from the field. Int. J. Interdiscip. Environ. Stud. 2014, 8, 17–29. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 850–867. [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Rural tourism and sustainable rural tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [CrossRef]

- MADR. Analiza Socio-Economica în Perspectiva Dezvoltarii Rurale 2014–2020; MADR: Bucharest, Romania, 2012; p. 67. Availeble online: https://www.madr.ro/docs/dezvoltare-rurala/Descrierea_generala_a_situatiei_economice_actuale_4_11_2013.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Leki’c, O.Z.; Gadži’c, N.; Milovanovi’c, A. Sustainability of rural areas—Exploring values, challenges and socio-cultural role. In Sustainability and Resilience—Socio-Spatial Perspective; Fikfak, A., Kosanovi’c, S., Konjar, M., Anguillari, E., Eds.; TU Delft Open: Delft, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 171–184.

- Adamowicz, M.; Zwoli’nska-Ligaj, M. New concept for rural development in the strategies and policies of the European Union. Econ. Reg. Stud. 2018, 11, 7–31. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Europa 2020, A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, Communication from the Commission; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:2020:FIN:en:PDF (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Jurnalul Oficial al Uniunii Europene. Aviz-Sustenabilitatea Zonelor Rurale. 2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/ LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2013:356:0080:0085:RO:PDF (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Feher, A.; Sorin, S.; Tiberiu, I.; Tabita, C.; Ramona, M.; Raul, P.; Banes, A.; Miroslav, R.; Gosa, V. Design of the macroeconomic evolution of Romania’s agriculture 2020–2040. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105815. [CrossRef]

- Feher, A.; Goșa, V.; Raicov, M.; Harangus, D.; Condea, B.V. Convergence of Romanian and Europe Union agriculture–evolution and prospective assessment. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 670–678. [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches–Towards a new generation concept? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1133–1156. [CrossRef]

- Paresishvili, O.; Kvaratskhelia, L.; Mirzaeva, V. Rural tourism as a promising trend of small business in Georgia: Topicality, capabilities, peculiarities. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2017, 15, 344–348. [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Jepson, D. Rural tourism a spiritual experience? Ann. Tour. Res., 2011, 38(1), 52-71. [CrossRef]

- Polo-Peña, A.I.; Frías-Jamilena, D.; Rodríguez-Molina, M.A. The perceived value of the rural tourism stay and its effect on rural tourist behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1045–1065. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impacts the quality of life of community ersidents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.; Ladkin, A. Sustainable tourism: A regional perspective. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 430–440. [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S.; Thompson-Fawcett, M. Tourism in a small town: Impacts on community solidarity. Int. J. Sustain. Soc. 2011, 3,174–189. [CrossRef]

- Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Peț, E.; Popescu, G.; Șmuleac, L. Sustainability of Agritourism Activity. Initiatives and Challenges in Romanian Mountain Rural Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2502. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Tribe, J. Sustainability indicators for small tourism enterprises—An exploratory perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 575–594. [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J.; Getz, D.; Ali-Knight, J. The environmental attitudes and practices of family businesses in the rural tourism and hospitality sectors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 281–297. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, B.; Twining-Ward, L. Seven steps towards sustainability: Tourism in the context of new knowledge. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 109–122. [CrossRef]

- Coroș, M.M.; Privitera, D.; Paunescu, L.M.; Nedelcu, A.; Lupu, C.; Ganușceac, A Marginimea Sibiului Tells Its Story: Sustainability, Cultural Heritage and Rural Tourism—A Supply-Side Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5309. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Álvaro, J.-J.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Sáez-Martínez, F.-J. Rural Tourism: Development, Management and Sustainability in Rural Establishments. Sustainability 2017, 9, 818. [CrossRef]

- Ivona, A. Sustainability of Rural Tourism and Promotion of Local Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8854. [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R.; Adamov, T.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Lile, R.; Rujescu, C.; Marin, D. Agritourism-A Sustainable Development Factor for Improving the ‘Health’ of Rural Settlements. Case Study Apuseni Mountains Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1467. [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Roman, M.; Prus, P. Innovations in Agritourism: Evidence from a Region in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4858. [CrossRef]

- Daye, M.; Gill, K. Social Enterprise Evaluation: Implications for Tourism Development. In Social Entrepreneurship and Tourism; Sheldon, P., Daniele, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 173–192. [CrossRef]

- Anisiewicz, R. Conditions for Development of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Tourism in the Border Area of the European Union: The Example of the Tri-Border Area of Poland–Belarus–Ukraine. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13595. [CrossRef]

- Muresan, I. C., Harun, R., Arion, F. H., Oroian, C. F., Dumitras, D. E., Mihai, V. C., Ilea, M., Chiciudean, D. I., Gliga, I. D., & Chiciudean, G. O. Residents’ Perception of Destination Quality: Key Factors for Sustainable Rural Development. Sustainability 2019, 11(9), 2594. [CrossRef]

- Demirovic Bajrami, D.; Radosavac, A.; Cimbaljevic, M.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, Y.A. Determinants of Residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: Implications for Rural Communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9438. [CrossRef]

- Kummitha, H.R.; Kolloju, N.; Jancsik, A.; Szalók, Z.C. Can Tourism Social Entrepreneurship Organizations Contribute to the Development of Ecotourism and Local Communities: Understanding the Perception of Local Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11031. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, E. The importance of tourism impacts for different local resident groups: A case study of a Swedish seaside destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 46–55. [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H.L. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [CrossRef]

- Euromontana. Background paper on sustainable mountain tourism. In Proceedings of the Conference Sustainable Active Tourism-Mountain Communities Leading Europe in Finding Innovative Solutions, Inverness, UK, 27–28 September 2011; Available online: https://www.euromontana.org/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Dax, T.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y. Agritourism Initiatives in the Context of Continuous Out-Migration: Comparative Perspectives for the Alps and Chinese Mountain Regions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4418. [CrossRef]

- Ibanescu, B.-C.; Stoleriu, O.; Munteanu, A.; Iațu, C. The Impact of Tourism on Sustainable Development of Rural Areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3529. [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, E. The role of rural tourism on the development of rural areas: The case of Cyprus. Rom. J. Reg. Sci. 2014, 8(1), 38–53.

- Ivona, A.; Rinella, A.; Rinella, F.; Epifani, F.; Nocco, S. Resilient Rural Areas and Tourism Development Paths: A Comparison of Case Studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3022. [CrossRef]

- Panyik, E.; Costa, C.; Ratz, T. Implementing integrated rural tourism: An event-based approach. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1352–1363. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, J. How does tourism in a community impacts the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Lorenzo, A.; Lyu, J.; Babar, Z.U. Tourism and development in developing economies: A policy implication perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1618. [CrossRef]

- Satco E.; Niculică A. Enciclopedia Bucovinei: Personalităţi, localităţi, societăţi, presă, instituţii. Vol. 3/ (colaboratori principali) Beck, Erich; Chindriş, Adriana; Pintilei, Elena; Niculică, Bogdan Petru - Suceava: Karl A. Romstorfer, 2018, 912. ISBN 9786068698250.

- Available online: https://usv.ro/despre-noi/istoria-locului/bucovina-trecut-prezent-si-perspective/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Iacobescu, M. Din istoria Bucovinei. Vol.I (1774-1862). București, Ed. Academiei Române, p.113. 1993. ISBN 973-27-0449-7, ISBN 973-27-0448-9.

- European Tourism Indicator System, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013. ISBN 978-92-79-29339-9. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6f6546d4-a9a9-458d-8878-b7232e3a6b78 (accessed on 20 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Simeanu, C.; Păsărin, B.; Simeanu, D.; Bodescu, D.; Moraru, R.-A. Evolution of demand for tourism services on the territory of Suceava County, Romania, in the period 2010-2019. Sci. Papers, Ser. Manag. Econom. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2022, 22(1). WOS:000798307300066.

- Simeanu, C.; Moraru, R.A.; Pasarin, B.; Simeanu, D.; Bodescu, D. The market dynamics of the tourism demand in Botosani County during the period 2009-2018. Sci. Papers, Ser. Manag. Econom. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2019, 19(4). WOS: 000503074300042.

- Nedelea A.-M.; Mironiuc M.; Huian M.-C.; Bȋrsan, M. and Bedrule-Grigoruţă, M.- V. Modeled Interdependencies between Intellectual Capital, Circular Economy and Economic Growth in the Context of Bioeconomy. Amfiteatru Economic 2018, 20(49). https://doi.org/10.24818/EA/2018/49/616.

- Bodescu, D.; Stefan, G.; Panzaru, R.-L.; Moraru, R.-A. Perception of the beekeepers regarding the principles of sustainable development in the North-Eastern Region of Romania. Sci. Papers, Ser. Manag. Econom. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2019, 19(1). WOS:000466139000009.

- Ursu L. Turism rural în Bucovina / Consiliul Judeţean Suceava, Centrul Naţional de Informare şi Promovare Turistică, Suceava: Muşatinii, 2013. ISBN 978-606-656-025-2 0. Available online: http://visitingbucovina.ro/wp-includes-fisiere/2019/07/Brosura-turism-rural-romana.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Nedelea A.; Nedelea M. – O. Strategii de promovare a brandului turistic Bucovina - Turism activ în Bucovina, Volum conferință, Suceava, pag. 36-49, 2009. Available online: http://www.turismactiv.ro/attachments/Vol_Ro.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/@47.5521184,25.8514227,11z?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDIwOS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed 12 February 2025).

- Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/@47.5661531,25.490321,11z?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDIwOS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed 12 February 2025).

- Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/@47.3685392,25.2948762,11z?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDIwOS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed 12 February 2025).

| Research steps and objectives |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| Places | Years UM: Number |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Berchisești | : | : | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cacica | 3 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 15 | 15 |

| Capu Câmpului | : | : | : | : | : | : | : | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ciprian Porumbescu | : | : | : | : | : | : | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ilișești | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | : | : | : | : | : |

| Mănăstirea Humorului | 12 | 14 | 18 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 30 | 33 | 42 |

| Ostra | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Păltinoasa | : | : | : | : | : | : | : | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Pârtestii de Jos | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Poieni-Solca | : | : | : | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | : |

| Stulpicani | : | : | : | : | : | : | : | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Todirești | 1 | : | : | : | : | : | : | 1 | : | : |

| Total | 20 | 21 | 30 | 36 | 34 | 33 | 37 | 55 | 59 | 69 |

| Places | Years UM: Number |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Breaza | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Frumosu | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Fundu Moldovei | 2 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 16 | 17 | 19 |

| Moldova Sulița | : | : | : | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Moldovița | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| Pojorâta | 10 | 8 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 16 | 30 | 34 | 31 |

| Sadova | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 17 | 17 | 19 |

| Vama | 19 | 18 | 18 | 22 | 24 | 23 | 24 | 31 | 32 | 31 |

| Vatra Moldoviței | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 15 |

| Total | 43 | 44 | 48 | 70 | 75 | 74 | 80 | 130 | 136 | 134 |

| Places | Years UM: Number |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Cârlibaba | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ciocănești | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Coșna | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Crucea | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Dorna Candreni | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 16 | 18 |

| Dorna Arini | 12 | 12 | 13 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 32 | 35 | 44 |

| Iacobeni | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Panaci | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 12 | 12 |

| Stampa Meadow | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Șaru Dornei | 5 | 5 | 7 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 25 | 27 | 33 |

| Total | 34 | 35 | 43 | 65 | 69 | 70 | 76 | 107 | 114 | 134 |

| Years | Accommodation capacity in operation (places-days) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) |

The rhythm of dynamics (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 95128 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 102594 | 7466 | 7466 | 107.85 | 107.85 | 7.85 | 7.85 |

| 2016 | 125711 | 30583 | 23117 | 132.15 | 122.53 | 32.15 | 22.53 |

| 2017 | 119636 | 24508 | -6075 | 125.76 | 95.17 | 25.76 | -4.83 |

| 2018 | 133109 | 37981 | 13473 | 139.93 | 111.26 | 39.93 | 11.26 |

| 2019 | 135371 | 40243 | 2262 | 142.30 | 101.70 | 42.30 | 1.70 |

| 2020 | 115696 | 20568 | -19675 | 121.62 | 85.47 | 21.62 | -14.53 |

| 2021 | 217053 | 121925 | 101357 | 228.17 | 187.61 | 128.17 | 87.61 |

| 2022 | 256082 | 160954 | 39029 | 269.20 | 117.98 | 169.20 | 17.98 |

| 2023 | 285479 | 190351 | 29397 | 300.10 | 111.48 | 200.10 | 11.48 |

| 158585.9 | 21150.11 | 1.1298 (112.98%) | 12.98% | ||||

| Years | Accommodation capacity in operation (places-days) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) |

The rhythm of dynamics (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 145702 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 167473 | 21771 | 21771 | 114.94 | 114.94 | 14.94 | 14.94 |

| 2016 | 170307 | 24605 | 2834 | 116.89 | 101.69 | 16.89 | 1.69 |

| 2017 | 208059 | 62357 | 37752 | 142.80 | 122.17 | 42.80 | 22.17 |

| 2018 | 238184 | 92482 | 30125 | 163.47 | 114.48 | 63.47 | 14.48 |

| 2019 | 244792 | 99090 | 6608 | 168.01 | 102.77 | 68.01 | 2.77 |

| 2020 | 178769 | 33067 | -66023 | 122.69 | 73.03 | 22.69 | -26.97 |

| 2021 | 348930 | 203228 | 170161 | 239.48 | 195.18 | 139.48 | 95.18 |

| 2022 | 371804 | 226102 | 22874 | 255.18 | 106.56 | 155.18 | 6.56 |

| 2023 | 412447 | 266745 | 40643 | 283.08 | 110.93 | 183.08 | 10.93 |

| 2486467 | 29638.33 | 1.1225 (122.25%) | 22.25% | ||||

| Years | Accommodation capacity in operation (places-days) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) |

The rhythm of dynamics (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 166061 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 181578 | 15517 | 15517 | 109.34 | 109.34 | 9.34 | 9.34 |

| 2016 | 179047 | 12986 | -2531 | 107.82 | 98.61 | 7.82 | -1.39 |

| 2017 | 239753 | 73692 | 60706 | 144.38 | 133.91 | 44.38 | 33.91 |

| 2018 | 238882 | 72821 | -871 | 143.85 | 99.64 | 43.85 | -0.36 |

| 2019 | 264206 | 98145 | 25324 | 159.10 | 110.60 | 59.10 | 10.60 |

| 2020 | 189129 | 23068 | -75077 | 113.89 | 71.58 | 13.89 | -28.42 |

| 2021 | 342400 | 176339 | 153271 | 206.19 | 181.04 | 106.19 | 81.04 |

| 2022 | 366117 | 200056 | 23717 | 220.47 | 106.93 | 120.47 | 6.93 |

| 2023 | 383444 | 217383 | 17327 | 230.91 | 104.73 | 130.91 | 4.73 |

| 2550617 | 24153.67 | 1.0974 (109.74%) | 9.74% | ||||

| Years | T(x) | Humor Area y = 21429x - 4E + 07 |

Câmpulung Moldovenesc Area y = 29725x - 6E + 06 |

Dorna Area y = 24957x - 5E + 07 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 11 | 266410.13 | 403409.2 | 386342.93 |

| 2025 | 12 | 292617.72 | 437862.3 | 415121.90 |

| 2026 | 13 | 319880.46 | 474721.7 | 444864.87 |

| 2027 | 14 | 351544.60 | 509054.7 | 470260.50 |

| 2028 | 15 | 381309.75 | 546893.8 | 504281.45 |

| Years | Index of net utilization of accommodation capacity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Humor Area | Câmpulung Moldovenesc Area | Dorna Area | |

| 2014 | 14.62 | 19.27 | 19.82 |

| 2015 | 18.99 | 19.11 | 20.87 |

| 2016 | 25.89 | 20.41 | 25.44 |

| 2017 | 34.05 | 18.45 | 23.71 |

| 2018 | 34.11 | 21.11 | 27.81 |

| 2019 | 38.98 | 22.64 | 29.25 |

| 2020 | 25.64 | 20.35 | 25.16 |

| 2021 | 27.04 | 22.68 | 25.80 |

| 2022 | 28.40 | 22.78 | 25.55 |

| 2023 | 26.11 | 25.68 | 25.53 |

| Years | Arrivals (number of persons) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) | The rhythm of dynamics (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 6482 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 9224 | 2742 | 2742 | 142.30 | 142.30 | 42.30 | 42.30 |

| 2016 | 15823 | 9341 | 6599 | 244.10 | 171.54 | 144.10 | 71.54 |

| 2017 | 17434 | 10952 | 1611 | 268.96 | 110.18 | 168.96 | 10.18 |

| 2018 | 19162 | 12680 | 1728 | 295.61 | 109.91 | 195.61 | 9.91 |

| 2019 | 21271 | 14789 | 2109 | 328.15 | 111.00 | 228.15 | 11.00 |

| 2020 | 13420 | 6938 | -7851 | 207.03 | 63.09 | 107.03 | -36.90 |

| 2021 | 26640 | 20158 | 13220 | 410.98 | 198.50 | 310.98 | 98.50 |

| 2022 | 31115 | 24633 | 4475 | 480.02 | 116.79 | 380.02 | 16.79 |

| 2023 | 33213 | 26731 | 2098 | 512.38 | 106.74 | 412.38 | 6.74 |

| 19378.4 | 2970.11 | 1.1990 (119.90%) | 19.90% | ||||

| Years | Arrivals (number of persons) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) | The rhythm of dynamics (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 10665 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 13946 | 3281 | 3281 | 130.76 | 130.76 | 30.76 | 30.76 |

| 2016 | 17829 | 7164 | 3883 | 167.17 | 127.84 | 67.17 | 27.84 |

| 2017 | 19143 | 8478 | 1314 | 179.49 | 107.37 | 79.49 | 7.37 |

| 2018 | 24706 | 14041 | 5563 | 231.65 | 129.06 | 131.65 | 29.06 |

| 2019 | 26176 | 15511 | 1470 | 245.44 | 105.95 | 145.44 | 5.95 |

| 2020 | 16247 | 5582 | -9929 | 152.34 | 62.07 | 52.34 | -37.93 |

| 2021 | 35149 | 24484 | 18902 | 329.57 | 216.34 | 229.57 | 116.34 |

| 2022 | 37116 | 26451 | 1967 | 348.02 | 105.60 | 248.02 | 5.60 |

| 2023 | 49443 | 38778 | 12327 | 463.60 | 133.21 | 363.60 | 33.21 |

| 25042 | 4308.67 | 1.1858 (118.58%) | 18.58% | ||||

| Years | Arrivals (number of persons) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) | The rhythm of dynamics (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 12933 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 15337 | 2404 | 2404 | 118.59 | 118.59 | 18.59 | 18.59 |

| 2016 | 17011 | 4078 | 1674 | 131.53 | 110.91 | 31.53 | 10.91 |

| 2017 | 24428 | 11495 | 7417 | 188.88 | 143.60 | 88.88 | 43.60 |

| 2018 | 25508 | 12575 | 1080 | 197.23 | 104.42 | 97.23 | 4.42 |

| 2019 | 30259 | 17326 | 4751 | 233.97 | 118.63 | 133.97 | 18.63 |

| 2020 | 21573 | 8640 | -8686 | 166.81 | 71.29 | 66.81 | -28.71 |

| 2021 | 39096 | 26163 | 17523 | 302.30 | 181.23 | 202.30 | 81.23 |

| 2022 | 40553 | 27620 | 1457 | 313.56 | 103.73 | 213.56 | 3.73 |

| 2023 | 42409 | 29476 | 1856 | 327.91 | 104.58 | 227.91 | 4.58 |

| 26910.7 | 3275.11 | 1.1410 (114.10%) | 14.10% | ||||

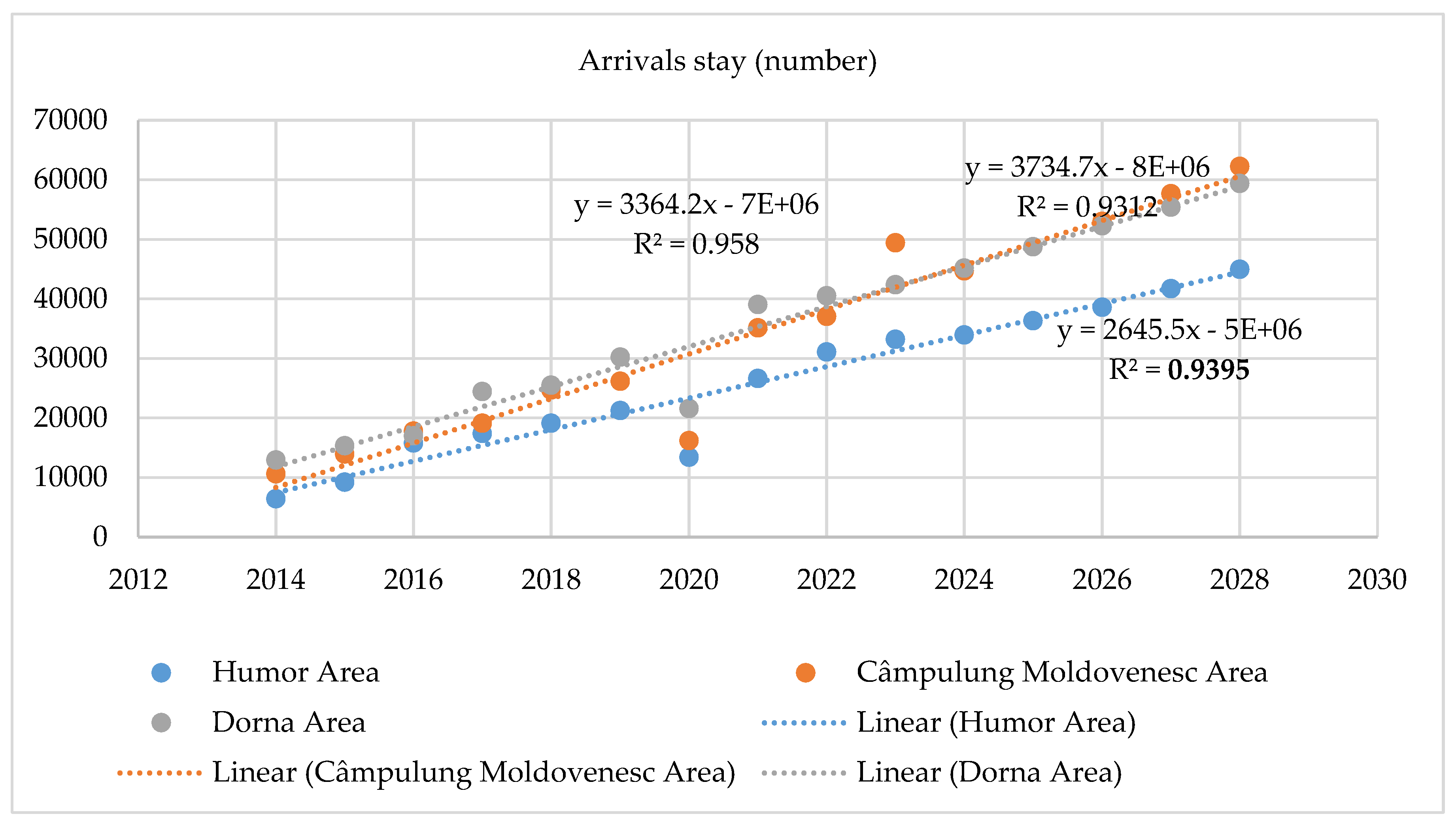

| Years | T(x) | Humor Area y = 0.012x – 21.874 |

Câmpulung Moldovenesc Area y = 0.0005x + 1.2239 |

Dorna Area y = -0.0375x + 78.159 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 11 | 33977.33 | 44727.80 | 45190.93 |

| 2025 | 12 | 36377.87 | 48768.25 | 48775.64 |

| 2026 | 13 | 38636.79 | 53028.97 | 52284.77 |

| 2027 | 14 | 41748.76 | 57707.95 | 55414.7 |

| 2028 | 15 | 45014.20 | 62262.26 | 59422.89 |

| Years | Overnight stays (number) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) | The rhythm of dynamics (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 13904 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 19482 | 5578 | 5578 | 140.12 | 140.12 | 40.12 | 40.12 |

| 2016 | 32545 | 18641 | 13063 | 234.07 | 167.05 | 134.07 | 67.05 |

| 2017 | 40731 | 26827 | 8186 | 292.94 | 125.15 | 192.94 | 25.15 |

| 2018 | 45401 | 31497 | 4670 | 326.53 | 111.47 | 226.53 | 11.47 |

| 2019 | 52771 | 38867 | 7370 | 379.54 | 116.23 | 279.54 | 16.23 |

| 2020 | 29665 | 15761 | -23106 | 213.36 | 56.21 | 113.36 | -43.79 |

| 2021 | 58696 | 44792 | 29031 | 422.15 | 197.86 | 322.15 | 97.86 |

| 2022 | 72730 | 58826 | 14034 | 523.09 | 123.91 | 423.09 | 23.91 |

| 2023 | 74534 | 60630 | 1804 | 536.06 | 102.48 | 436.06 | 2.48 |

| 44045.9 | 6736.67 | 1.2050 (120.50%) | 20.50% | ||||

| Years | Overnight stays (number) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) | The rhythm of dynamics (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 28076 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 32012 | 3936 | 3936 | 114.02 | 114.02 | 14.02 | 14.02 |

| 2016 | 34761 | 6685 | 2749 | 123.81 | 108.59 | 23.81 | 8.59 |

| 2017 | 38389 | 10313 | 3628 | 136.73 | 110.44 | 36.73 | 10.44 |

| 2018 | 50272 | 22196 | 11883 | 179.06 | 130.95 | 79.06 | 30.95 |

| 2019 | 55417 | 27341 | 5145 | 197.38 | 110.23 | 97.38 | 10.23 |

| 2020 | 36379 | 8303 | -19038 | 129.57 | 65.65 | 29.57 | -34.35 |

| 2021 | 79122 | 51046 | 42743 | 281.81 | 217.49 | 181.81 | 117.49 |

| 2022 | 84694 | 56618 | 5572 | 301.66 | 107.04 | 201.66 | 7.04 |

| 2023 | 105908 | 77832 | 21214 | 377.22 | 125.05 | 277.22 | 25.05 |

| 54503 | 77832 | 1.1589 (115.89%) | 15.89% | ||||

| Years | Overnight stays (number) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) | The rhythm of dynamics (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 32920 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 37892 | 4972 | 4972 | 115.10 | 115.10 | 15.10 | 15.10 |

| 2016 | 45544 | 12624 | 7652 | 138.35 | 120.19 | 38.35 | 20.19 |

| 2017 | 56846 | 23926 | 11302 | 172.68 | 124.82 | 72.68 | 24.82 |

| 2018 | 66434 | 33514 | 9588 | 201.80 | 116.87 | 101.80 | 16.87 |

| 2019 | 77286 | 44366 | 10852 | 234.77 | 116.34 | 134.77 | 16.34 |

| 2020 | 47579 | 14659 | -29707 | 144.53 | 61.56 | 44.53 | -38.44 |

| 2021 | 88324 | 55404 | 40745 | 268.30 | 185.64 | 168.30 | 85.64 |

| 2022 | 93536 | 60616 | 5212 | 284.13 | 105.90 | 184.13 | 5.90 |

| 2023 | 97877 | 64957 | 4341 | 297.32 | 104.64 | 197.32 | 4.64 |

| 64423.8 | 7217.44 | 1.1287 (112.87%) | 12.87% | ||||

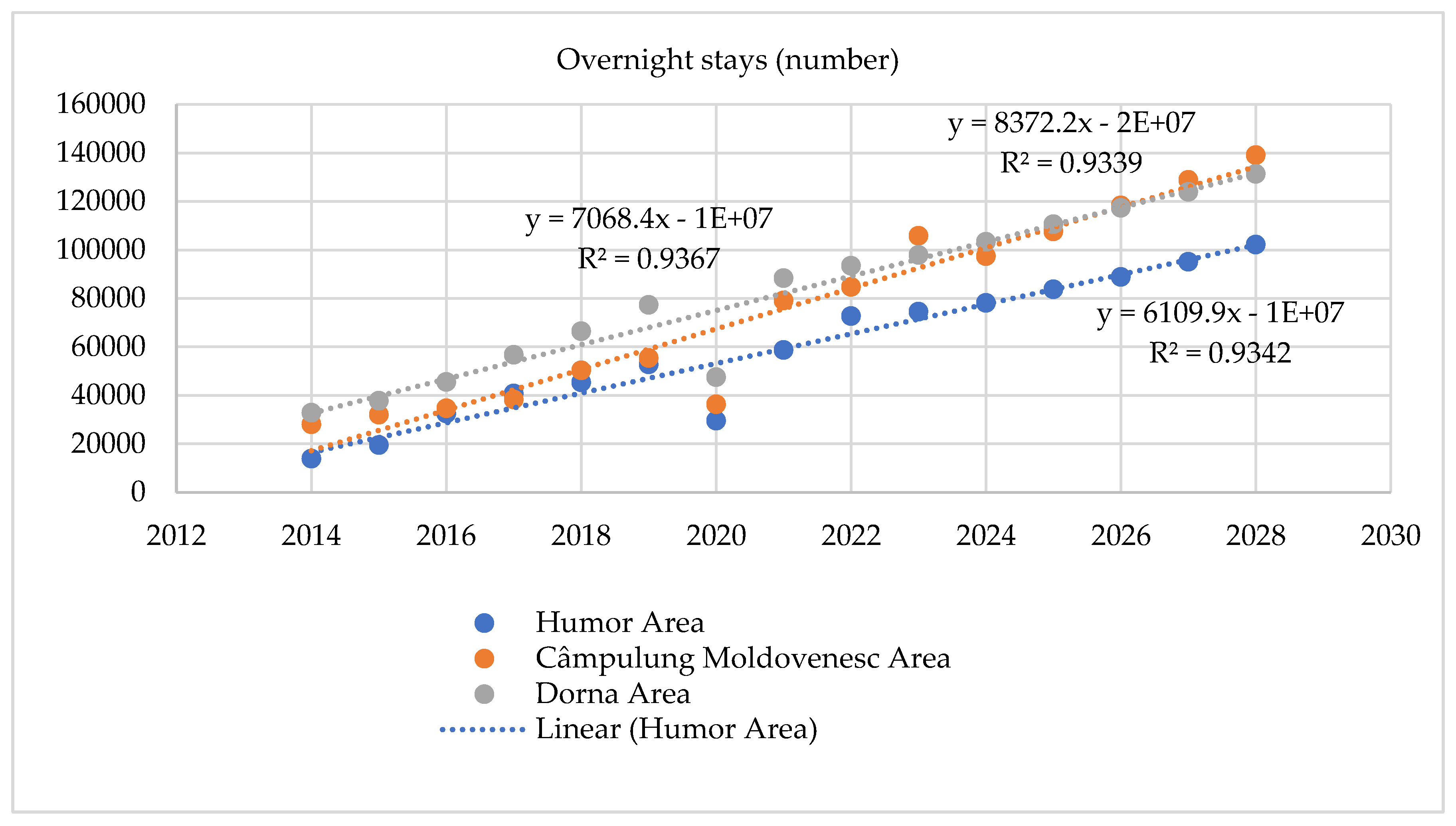

| Years | T(x) | Humor Area y = 6109.9x – 1E + 07 |

Câmpulung Moldovenesc Area y = 8372.2x - 2E + 07 |

Dorna Area y = 7068.4x - 1E + 07 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 11 | 78157 | 97509.07 | 103459.53 |

| 2025 | 12 | 83763.6 | 107664.3 | 110672.81 |

| 2026 | 13 | 88816.77 | 118302.3 | 117394.64 |

| 2027 | 14 | 95089.24 | 128885.2 | 123993.67 |

| 2028 | 15 | 102302.18 | 139099.2 | 131456.13 |

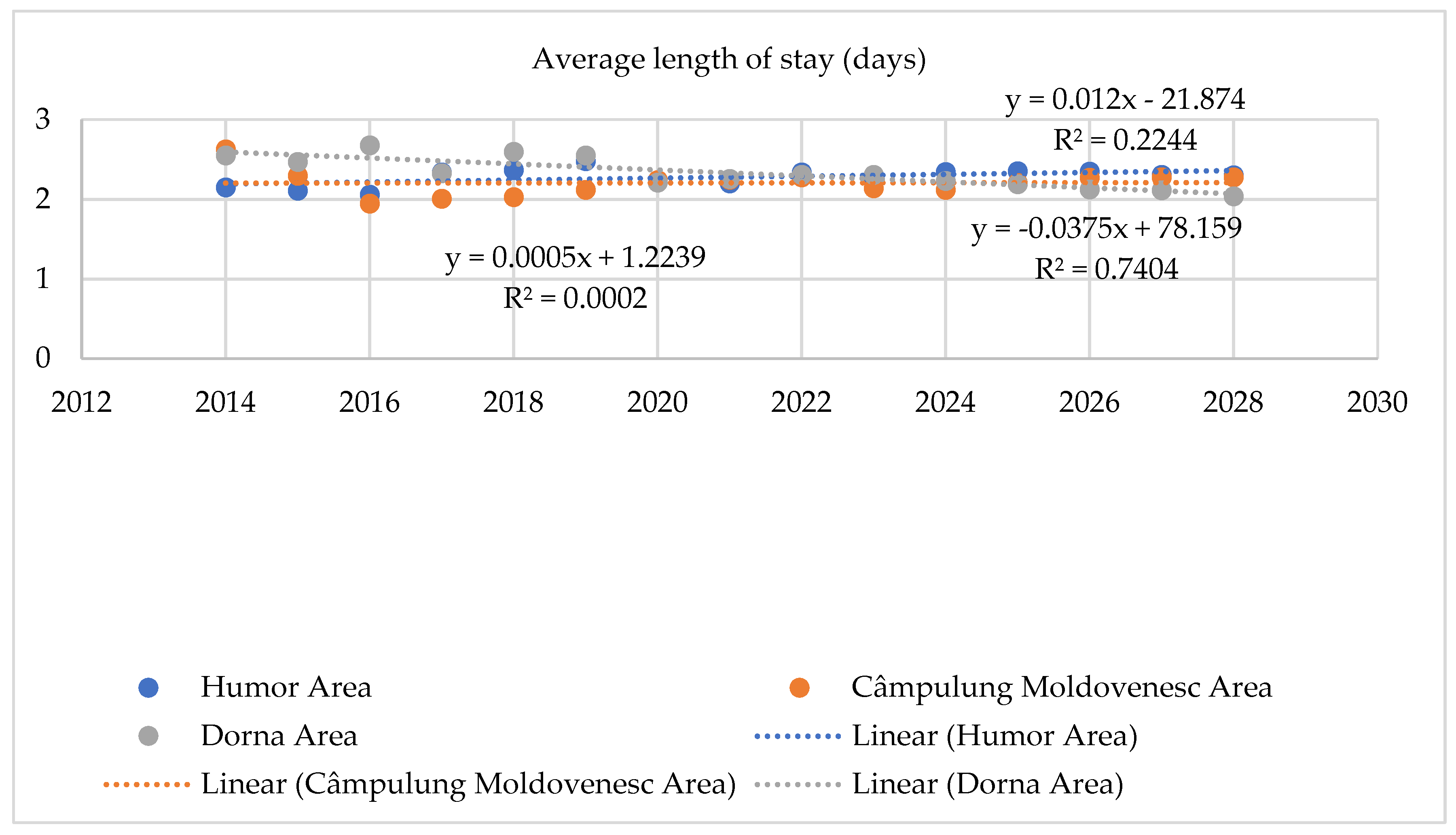

| Years | DMS (days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Humor Area | Câmpulung Moldovenesc Area | Dorna Area | |

| 2014 | 2.15 | 2.63 | 2.55 |

| 2015 | 2.11 | 2.30 | 2.47 |

| 2016 | 2.06 | 1.95 | 2.68 |

| 2017 | 2.34 | 2.01 | 2.33 |

| 2018 | 2.37 | 2.03 | 2.60 |

| 2019 | 2.48 | 2.12 | 2.55 |

| 2020 | 2.21 | 2.24 | 2.21 |

| 2021 | 2.20 | 2.25 | 2.26 |

| 2022 | 2.34 | 2.28 | 2.31 |

| 2023 | 2.24 | 2.14 | 2.31 |

| Years | DMS (days) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) | The rhythm of dynamics (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 2.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 2.11 | -0.04 | -0.04 | 98.14 | 98.14 | -1.86 | -1.86 |

| 2016 | 2.06 | -0.09 | -0.05 | 95.81 | 97.63 | -4.19 | -2.37 |

| 2017 | 2.34 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 108.84 | 113.59 | 8.84 | 13.59 |

| 2018 | 2.37 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 110.23 | 101.28 | 10.23 | 1.28 |

| 2019 | 2.48 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 115.35 | 104.64 | 15.35 | 4.64 |

| 2020 | 2.21 | 0.06 | -0.27 | 102.79 | 89.11 | 2.79 | -10.89 |

| 2021 | 2.20 | 0.05 | -0.01 | 102.33 | 99.55 | 2.33 | -0.45 |

| 2022 | 2.34 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 108.84 | 106.36 | 8.84 | 6.36 |

| 2023 | 2.24 | 0.09 | -0.1 | 104.19 | 95.73 | 4.19 | -4.27 |

| 2.25 | 0.01 | 1.0045 (100.45%) | 0.45% | ||||

| Years | DMS (days) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) | The rhythm of dynamics (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 2.63 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 2.30 | -0.33 | -0.33 | 87.45 | 87.45 | -12.55 | -12.55 |

| 2016 | 1.95 | -0.68 | -0.35 | 74.14 | 84.78 | -25.86 | -15.22 |

| 2017 | 2.01 | -0.62 | 0.06 | 76.43 | 103.08 | -23.57 | 3.08 |

| 2018 | 2.03 | -0.6 | 0.02 | 77.19 | 101.00 | -22.81 | 1.00 |

| 2019 | 2.12 | -0.51 | 0.09 | 80.61 | 104.43 | -19.39 | 4.43 |

| 2020 | 2.24 | -0.39 | 0.12 | 85.17 | 105.66 | -14.83 | 5.66 |

| 2021 | 2.25 | -0.38 | 0.01 | 85.55 | 100.45 | -14.45 | 0.45 |

| 2022 | 2.28 | -0.35 | 0.03 | 86.69 | 101.33 | -13.31 | 1.33 |

| 2023 | 2.14 | -0.49 | -0.14 | 81.37 | 93.86 | -18.63 | -6.14 |

| 2.20 | -0.05 | 0.9773 (97.73%) | -2.27% | ||||

| Years | DMS (days) |

Absolute changes | Dynamics index (%) | The rhythm of dynamics (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆t/1 | ∆t/t-1 | It/1 | It/t-1 | Rt/1 | Rt/t-1 | ||

| 2014 | 2.55 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2015 | 2.47 | -0.08 | -0.08 | 96.86 | 96.86 | -3.14 | -3.14 |

| 2016 | 2.68 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 105.10 | 108.50 | 5.10 | 8.50 |

| 2017 | 2.33 | -0.22 | -0.35 | 91.37 | 86.94 | -8.63 | -13.06 |

| 2018 | 2.60 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 101.96 | 111.59 | 1.96 | 11.59 |

| 2019 | 2.55 | 0 | -0.05 | 100.00 | 98.08 | 0.00 | -1.92 |

| 2020 | 2.21 | -0.34 | -0.34 | 86.67 | 86.67 | -13.33 | -13.33 |

| 2021 | 2.26 | -0.29 | 0.05 | 88.63 | 102.26 | -11.37 | 2.26 |

| 2022 | 2.31 | -0.24 | 0.05 | 90.59 | 102.21 | -9.41 | 2.21 |

| 2023 | 2.31 | -0.24 | 0 | 90.59 | 100.00 | -9.41 | 0.00 |

| 2.43 | 0.03 | 0.9890 (98.90%) | -1.1% | ||||

| Years | T(x) | Humor Area y = 6109.9x – 1E + 07 |

Câmpulung Moldovenesc Area y = 8372.2x - 2E + 07 |

Dorna Area y = 7068.4x - 1E + 07 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 11 | 2.34 | 2.12 | 2.23 |

| 2025 | 12 | 2.36 | 2.21 | 2.19 |

| 2026 | 13 | 2.35 | 2.27 | 2.13 |

| 2027 | 14 | 2.31 | 2.28 | 2.11 |

| 2028 | 15 | 2.31 | 2.28 | 2.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).