2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

To understand the two navigators’ working experiences, we asked them to keep journals over the course of the pilot period (April 2021-March 2022). Only the navigators employed in the pilot were included in the study as we were interested in evaluating the program from multiple angles, including usage statistics, post-service use surveys, client and HCP interviews and the navigators’ perspectives [

8,

9,

10]. The inclusion criteria were the same as the employment criteria: the individual had to be TGD, they had to have either health care or CBO experience. The navigators were both researchers and participants, and they provided written informed consent when they were hired.

The navigators could keep their journals in the form (physical or digital) they preferred; both chose digital formats. All names were anonymized within the documents. The navigators are also not named here; their journals are attributed only to “Navigator A” or “Navigator B”: the intent of this is to minimize the possibility of identifying any individuals referred to, however obliquely, in quotations from the journals, by making it unclear exactly which navigator, in which region, is quoted.

2.2. Materials

The navigators were encouraged to reflectively interrogate their own biases in their interactions with both clients and HCPs. They were asked to think about what might be missing from these conversations: what the people who are TGD and HCPs do and don’t ask or say. Researchers stressed to the navigators that there was no wrong or right way to journal, and that the tone, style, and in particular, narrative of their journal might change from entry to entry or over the course of the pilot period. While some possible prompts were included, the navigators wrote freely. Navigators were asked to journal weekly about recent events to keep their memories fresh.

The journals were not edited by researchers, though quoted excerpts may be edited for clarity, brevity, and spelling or grammatical errors. The journal documents are stored on a secure University of Saskatchewan server accessible only to research team members. Researchers were people who are TGD, academic researchers, or both. The navigators were part of the research team.

2.3. Analysis

Given that there were only two data sets (the two journals) and taking into consideration the similarity of the two journals, we treated the journals as a single case study. Navigator A wrote 39 journal entries during the pilot period, while Navigator B wrote 57. This disparity was not meaningful, considering the varying length of the journal entries themselves, and overall, after cross-comparison, all research team members agreed that the journals could be analysed together; the main themes we found were present in both documents.

In analysing the data thematically, we followed the principles Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), given IPA’s “focu[s] on how individuals make sense of their experience of the thing of interest” [11] (p. 1). Engward and Goldspink outline six steps to IPA: 1) Read and re-read the data, 2) Make initial notes, 3) Develop emerging themes, 4) Search for connections across these themes, 5) Move to the next case, 6) Look for patterns across cases [

12] (p. 8). An IPA approach to analysing the journals was important, since IPA encourages researchers to acknowledge their own biases and perceptions of research data [

13]. We all knew the navigators well and had heard details of their work before—there was no way to be objective about our analysis of their journals, and, instead, the research team openly discussed their own perceptions of the navigators and their work with the navigators when we met to discuss codes and themes. We encouraged open discussion of disagreements among researchers and challenged each other to explain why we felt and thought the way we did to increase awareness of our biases. We followed Engward and Goldspink’s steps as researchers (K.M.; E.G.; T.F.M.; M.M.; S.J.M.; M.C.) completed our analyses of the journals using NVivo software (

https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home). The navigators completed the first three steps on their own journals, as did two other researchers per journal. The two smaller teams met to discuss each journal, with an additional researcher (G.R.) who attended both meetings and read both journals but did no initial coding. These steps resulted in the creation of emerging themes; given the navigators’ close personal connections to the data, their personal interpretations of their respective journals were given precedence in this process. In step four, researchers used extended discussion to establish consensus—if one researcher had coded a theme as “difficult tasks,” for example, and another had coded a theme as “challenging experiences,” these were merged after checking to see if the parts of the journals on which they were based corresponded.

Across both journals, our research team initially created 185 unique codes after merging duplicates. We defined “codes” as terms or phrases that were used to define a meaningful part of the data, as defined by highlighted sentences or paragraphs that contributed to that code. For example, a code titled “end of service” was defined by passages—from both journals—that reflected the navigators’ thoughts on the impending end of the pilot period, after which they would no longer be able to help their clients—this, and not their personal unemployment, was the chief concern of both navigators in reflections relating to this event.

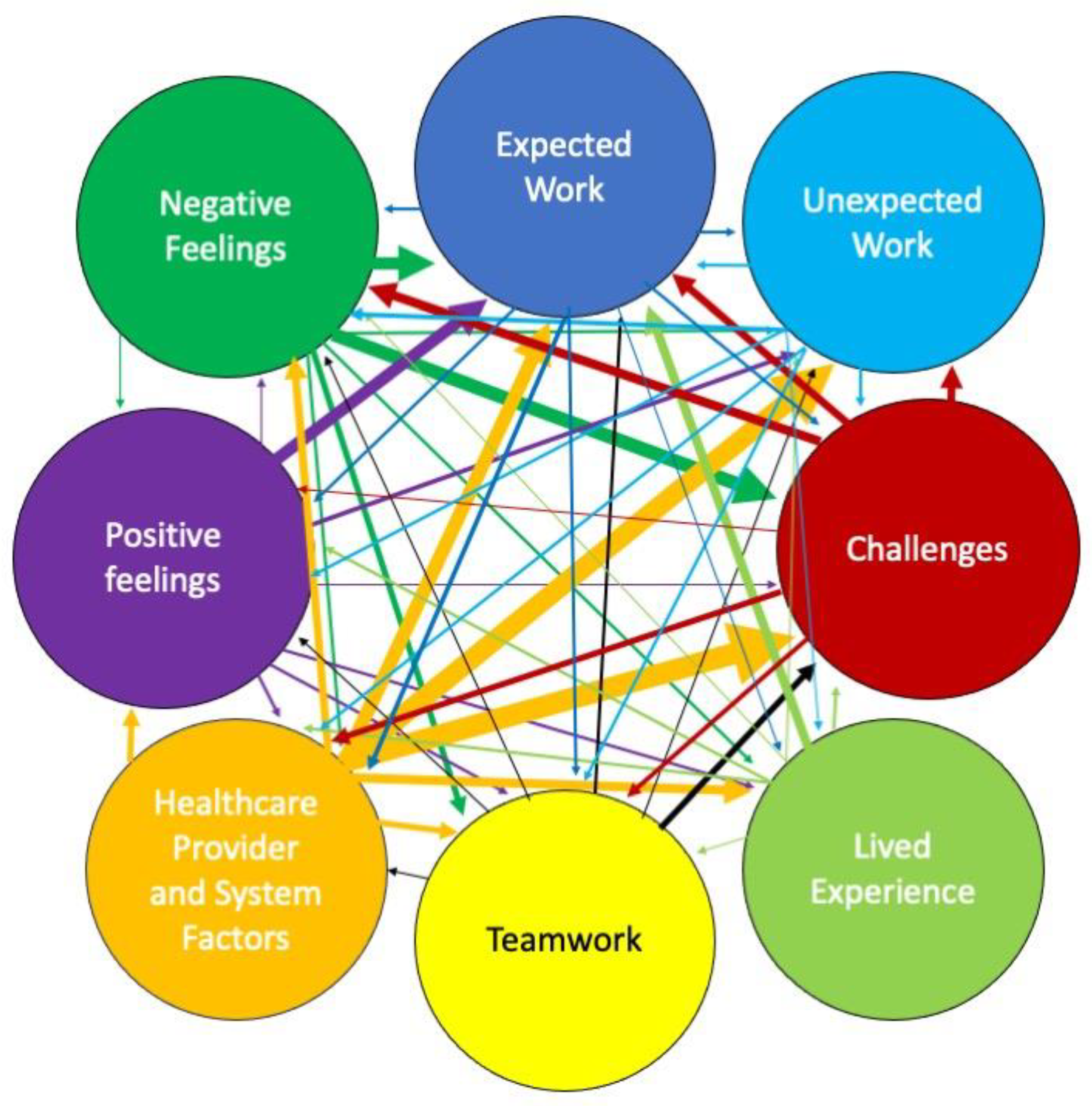

In step five, the two groups exchanged and compared data, including journals and coding, and then all researchers again worked to establish consensus around coding for the two journals together. In step six, researchers searched for patterns between the two journals, identifying connections across and between the codes. To achieve a more detailed understanding of these connections and patterns, codes that emerged from group discussion were further organized by S.J.M. and G.R. into six larger themes, first on a table, then at the request of the research team, as a graphic to visualize the connections.

Quotes selected for this paper were vetted by the navigators: as members of our community whose identities we know we cannot truly anonymize; we wanted to respect their personal lives and their comfort with sharing their recorded thoughts in a public platform. The navigators’ personal connections to this work, and that of research team members, also factored into our analysis of their journals and our commitment to the principle of “nothing about us, without us.” Given our long-established relationships as a team, our practices of open and honest communication, and the inclusion of people with a diversity of positionalities on each small analysis team, we felt assured that we would be able to address each other’s biases as they arose. Simultaneously, these factors allowed our research team to feel confident in our interpretation of the data and with how we portrayed the data in the themes and sub-themes.

2.4. Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Behavioural Research Ethics Board (Beh-1897). Maintaining the reflective journals was part of the navigators’ employment contract. All candidates for the navigator positions were informed about the journals during the job interview and the successful candidates provided written informed consent as part of the hiring process.

4. Discussion

This study is novel because it examined the navigators’ experiences, and not client outcomes or the efficacy of the program, which we assessed separately [

9,

10]. Overall, the themes we identified in the navigators’ journals tell us that their work was hard, yet rewarding. The sheer variety of tasks they took on was staggering, and they deftly switched between dealing with clients and HCPs. Though it was not the intent of this study, the navigators did reflect on their successes over time, and clearly indicated that they thought they were helping to improve the lives of people who are TGD in Saskatchewan. In the end, the navigators’ perceived their success to be most related to being able to assist their clients, and they were proud of the things they were able to accomplish. We found limited literature analysing the experiences of navigators in other peer health navigation programs, which was why we undertook this study.

We could only find two other studies that discussed the experiences of healthcare navigators. Both were published after the TRANS Project completed the planning phase. Reid et al. interviewed ten pediatric patient navigators across Canada [

3]. Seven were professional navigators, one was a peer navigator and the other two were lay navigators. They found, similarly to our navigators, that lay models of navigation made it easier to develop rapport with clients and that the navigators were not always respected by HCPs [

3]. In the professional models of navigation they found, also similarly to our navigators, that system knowledge and understanding client needs are essential [

3]. In Reid’s study, this came from professional training [

3], our navigators gained this knowledge from a combination of professional training and lived experience. Reid also found some commonalities between the lay and professional models [

3]. First that both fostered client-centred care and strove to meet people where they were which were important goals for our navigators. Reid’s study found that being embedded in the healthcare system was an advantage [

3], and our navigators identified being outside the system was a barrier to their work. Finally, Reid found that the personality and experience of the navigators was important [

3], which is very similar to our navigators who repeatedly commented on how much their lived experience helped them in their jobs.

Gauthier et al. conducted a pilot study with lay navigators in primary care in Sudbury and Ottawa, Ontario, Canada [

6]. They had two navigators reflectively journal about critical learning incidents; together they recorded a total of 66 journal entries [

6]. The research explored the navigators’ learning experiences and its implications for education and health promotion. They found five themes; four of which were very similar to ours and one which differed. The similar themes were: Gaining and Building Trust, Experiencing Hope and Optimism, Feeling Helpless and Celebrating Gains and Successes [

6]. They found that gaining and building trust was an ongoing process that lasted for the entire duration of the intervention with each client, which contrasted with our navigators who found that they built trust quickly. Similarly to our navigators, Gauthier’s navigators experienced hope and optimism when clients demonstrated motivation to help themselves and followed through with recommendations. Both Gauthier’s and our navigators felt helpless in very similar circumstances, when up against systemic obstacles. There were some additional differences, Gauthier’s navigators ran up against barriers posed by the study design and frustration when clients’ lacked motivation and follow through, while our navigators were limited by working outside the healthcare system. Both sets of navigators took huge pleasure in celebrating even small improvements or achievements for their clients. The theme that was most different form our results was "Gaining and Building Trust" [

6]. Our navigators wrote about how easily trust developed between them and their clients, contrasting with the navigators in the Gauthier study. A possible reason for this difference is that our navigators shared more of their lived experience with their clients which facilitated rapport and trust, whereas the navigators in Gauthier’s study did not share the lived experience of their clients. The research questions were also quite different between the two studies, which is likely to have been part of the different emphases in the findings. Despite their differences, the similarities between our study and Reid’s and Gauthier’s is remarkable. This suggests that we have found some characteristics of healthcare navigation that are transferable across settings, at least within Canada, such as the importance of rapport, empathy and lived experience, that navigators who work outside the healthcare system are not always respected by HCPs, that systemic barriers impede navigators’ work, and that clients’ successes make the job rewarding.

The navigators consistently noted that doing this work as people who are TGD themselves, who functioned as advocates for members of and on behalf of their own community, was part of their success and helped them to establish rapport with clients, as well as providing them with greater understanding of why people who are TGD might seek care, and the type of care that they hoped to receive. This was anticipated, as the rationale that peer navigation is employed—to lean on the relatability and expertise of people with lived expertise who represent a community. It provided meaning to the navigators and made the work particularly rewarding to them, and they themselves identified this as a factor that they believed contributed to their successes.

Barriers to their work were perceived as both frustrating and, in some cases, unnecessary. A lack of affirming HCPs willing to provide trans-specific care led to difficulty in helping clients access care or caused substantial delays. The navigators consistently highlighted that resistance from HCPs to providing trans-specific care hindered their work and were based on HCPs’ personal choices as opposed to strictly medical reasons. Christopherson et al. studied Saskatchewan HCPs’ comfort and willingness with providing trans-specific care, and found 66.5% (n= 125) of the188 Saskatchewan HCPs surveyed indicated they had no formal training with transition-related healthcare [

2]. Only 30.3% (n=57) of respondents indicated that they were comfortable providing transition-related medical care [

2]. The researchers also noted that 9.6% of respondents (n=18) indicated that they had “ethical, religious, or moral reservations about providing transition-related healthcare” [

2] (p. 471). Since Christopherson et al. also found that most participants (76%, n = 142) were interested in education on trans-specific healthcare needs [

2], training must be prioritized: given the lack of primary HCPs was so frequently discussed in the journals.

Another challenge for the navigators that created a barrier to effectively conducting their work was the perceived legitimacy of their positions, which operated outside of Saskatchewan’s formal healthcare system. This was a by-product of their positions being piloted by a university research team, as opposed to by the healthcare system itself. Their journals reflected a very real perception that working from within the healthcare system would have increase the perceived legitimacy of their work in the eyes of HCPs, and that being based in CBOs reduced their credibility. As healthcare and health needs were the primary focus of their work with and on behalf of people who are TGD, the navigators identified a desire for their work to be acknowledged as healthcare work, and that future navigation work in Saskatchewan on behalf of the TGD community would be best accomplished by fully integrating these positions within the healthcare system itself.

We found only one other study that addressed the perceived legitimacy of navigators as part of the healthcare team or how their "homebase" affected their credibility among other HCPs [

3]. Another pilot study noted limits for their navigators’ work simply as a by-product of being a pilot [

15]. We also note that, overall, it seems to be unusual for navigators to be housed outside formal healthcare systems [

4,

6,

16,

17,

18]. This suggests that being based from a CBO was a barrier. Here we identify that more study of the experiences of navigators themselves is needed, beyond merely evaluating the efficacy of their positions. In British Columbia in particular, peer navigators for people who are TGD

are housed in the provincial health authority [

4], so there is another Canadian model supporting what our navigators perceived as the most effective way to conduct their work, although a published formal evaluation of this provincial program’s efficacy has not been undertaken.

Strengths and Limitations

The journaling method produced insights that could not have been obtained through retrospective interviews. We were able to analyze how the navigators felt about issues and topics as they arose. We were able to see how the navigators felt about their own work, including what was clearly a high workload and a high-stress, if high-reward, working environment. We were also able to identify improvements and recommendations from the navigators to improve their quality of work, or their ability to do their jobs. Analyzing the journals together at the end of the project gave the navigators insights such as what they had learned over time and how they had incorporated past experiences into present practice over the course of the pilot year. Our large analysis team, which included the navigators, was strength, because it allowed us to include people who are TGD throughout the process without unduly adding to minority stress; it allowed us to assign researchers who did not live in the same city as the navigator to the smaller analysis teams to protect anonymity, and it gave us the benefit of the navigators’ deep understanding of their roles when analyzing the journals.

We acknowledge limitations present in the method as well: having the navigators participate in the analysis may have caused other researchers on the team to self-censor during discussions. However, we were a well-established research team, since 2018, with norms that promoted open, respectful discussions, encouraged expression of disagreement, and welcomed questions. Including only the two journals as data did not allow for a triangulation analysis which may have limited the validity of our findings. However, given that the purpose of this research was not to find truth, but rather to make meaning [

19] (p. 238), having a large analysis team that worked by consensus worked to ensure that there was a shared understanding of the experience of being navigators that was not unduly influenced by any individual’s bias. Including only two journals, from only one navigator program, does suggest a certain homogeneity in experiences between the two navigators given how closely they worked together and a limitation in the variability of experiences. Thus, there is no way to know if saturation has been reached. It is our intention to use these results as a foundation to study the experiences of trans healthcare navigators across Canada to better understand the differences and similarities among services and how they affect navigators’ work.

Implications

There are several implications from this work. The first is a better understanding of the complexity of our healthcare navigators for people who are TGD’s work in terms of the number of tasks that they performed, the diversity of these tasks and the emotional demands of the work. Better understanding the actual requirements of the work allowed us to provide better support to the navigators as the pilot was running, e.g., emotionally, continuing eduction, on the job training and mentorship. It may assist others who are establishing navigator programs to anticipate their navigators’ needs and to have supports, benefits, including adequate coverage for mental healthcare and time off, and education in place earier than we did, which is likely to reduce stress on the peer navigators.

The second major implication is that understanding the network of the navigators’ responsibilities, and how they interact with HCPs, CBOs and other service providers in the community allows for a focus on relationship building. This may avoid the difficulities we had with the navigators not being taken seriously by some HCPs and the turf conflicts they had early on with some 2SLGBTQ+ CBOs. Stronger relationships would both reduce stress on the navigators and improve services for clients, as there would be less duplication of services, better flow for clients and HCPs might be more likely to reach out to the navigators for education, which would increase the number of providers available to provide care to people who are TGD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.M., M.C. and S.J.M.; methodology, M.C.M., M.C., S.J.M.; validation, G.R., K.M., E.G., T. F-M., M.C.M, M.C, S.J.M.; formal analysis, G.R., K.M., E.G., T. F-M., M.C.M, M.C, S.J.M.; resources, M.C., S.J.M.; data curation, G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.R.; writing—review and editing, G.R., K.M., E.G., T. F-M., M.C.M, M.C, S.J.M.; visualization, G.R., S.J.M.; supervision, M.C., S.J.M; project administration, K.M., E.G., M.C., S.J.M.; funding acquisition, M.C., S.J.M.