Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

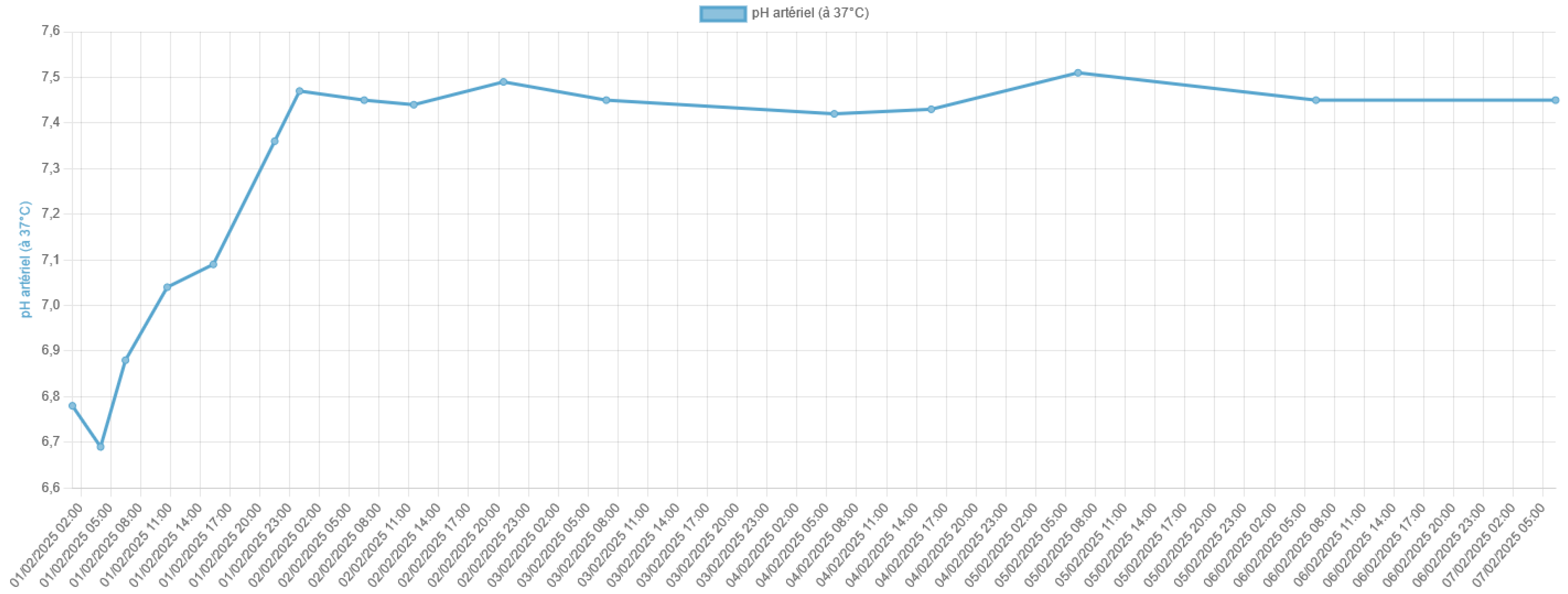

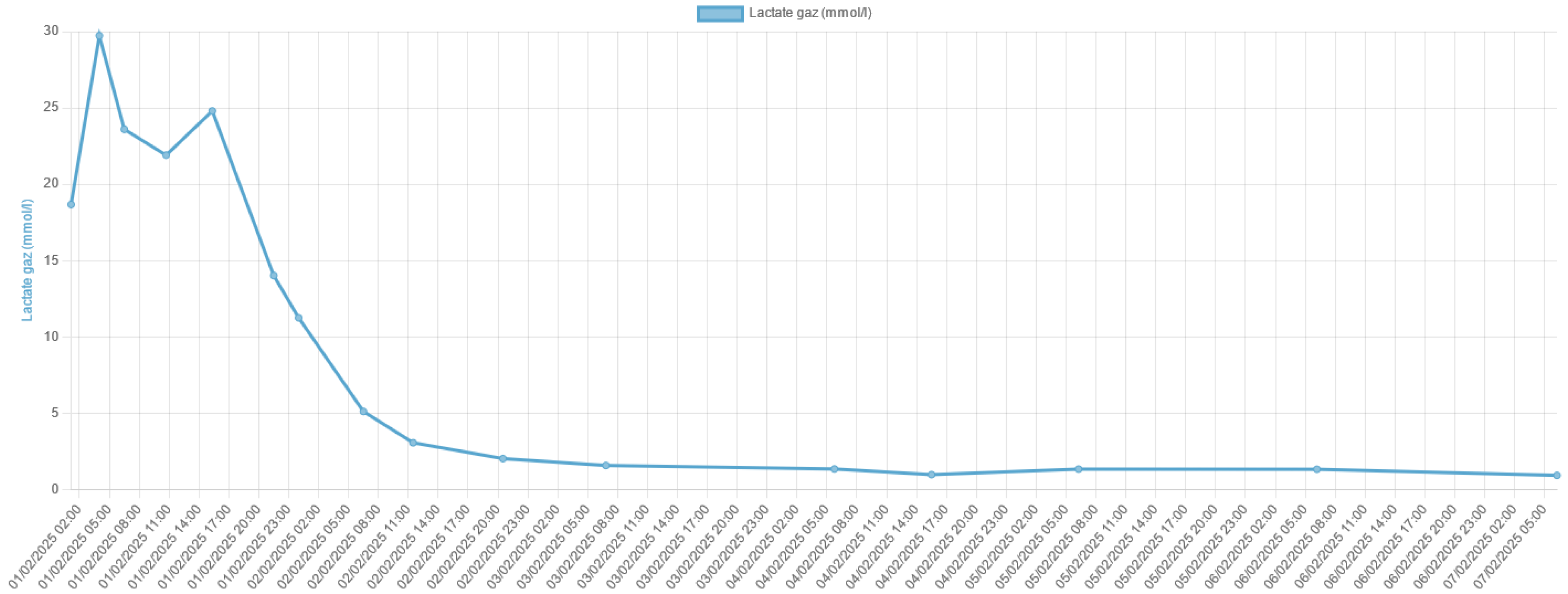

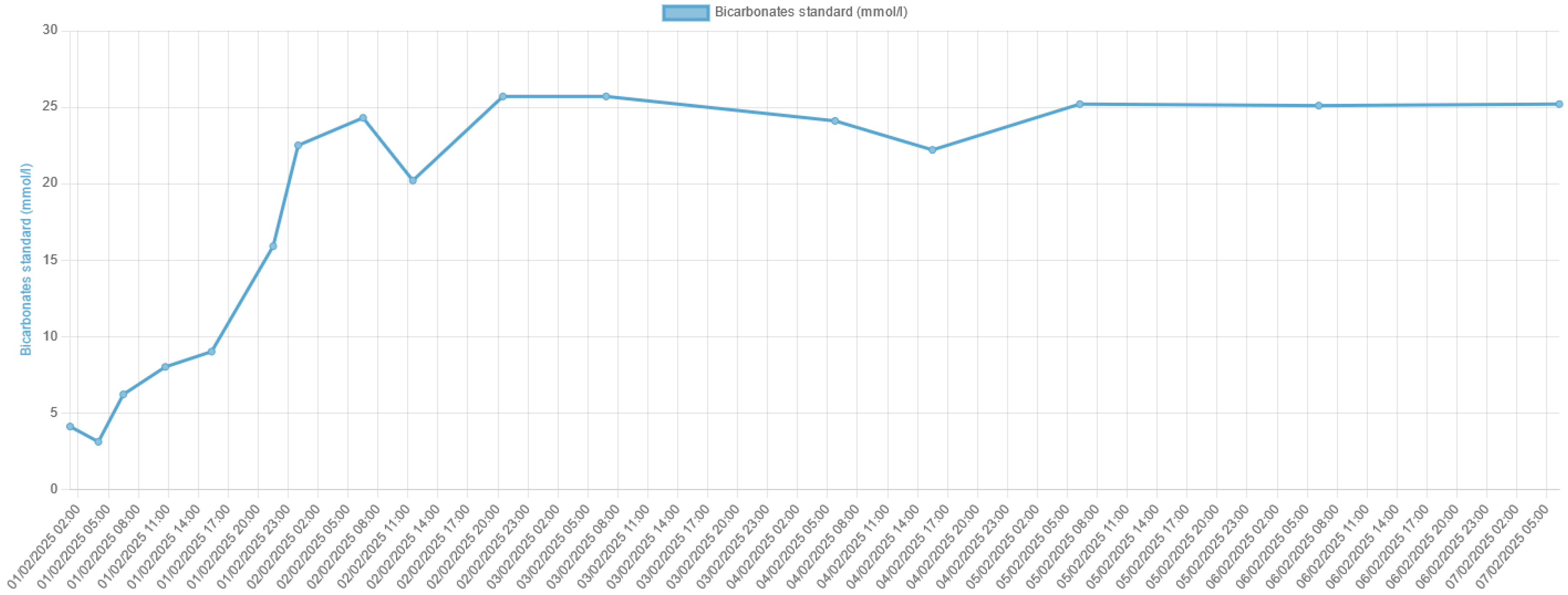

Lactic acidosis is a serious metabolic disorder characterized by an accumulation of lactate in the body, which can lead to a severe acid-base imbalance. Metfor-min-associated lactic acidosis is a rare but life-threatening complication of metformin therapy, particularly in the setting of acute kidney injury or other conditions that im-pair lactate clearance. In this case report, we present the remarkable survival of a patient who experienced severe metformin-associated lactic acidosis with a blood pH of 6.8 and a lactate level of 29 mmol/L, which are typically considered incompatible with life.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

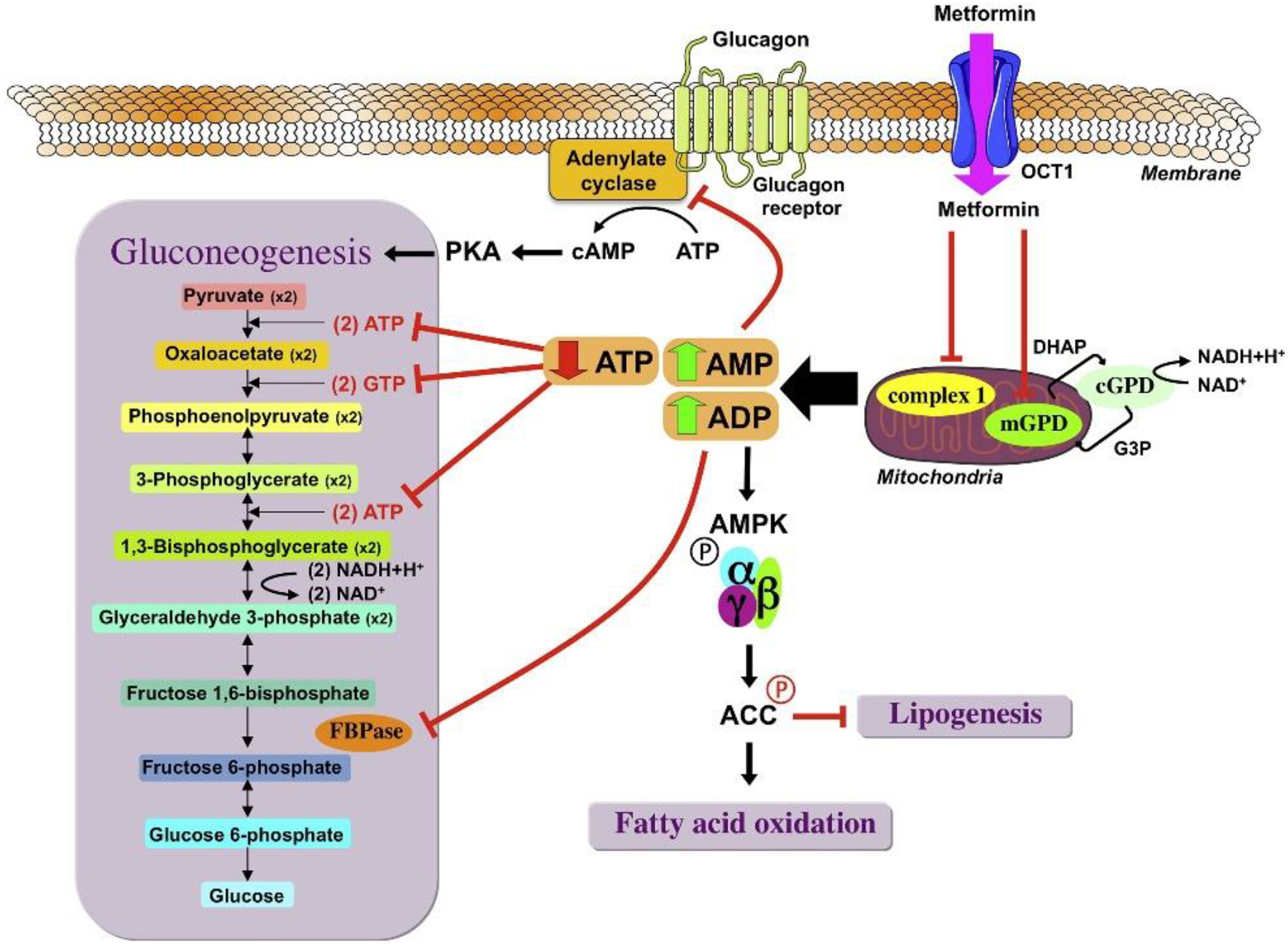

Pathophysiology of Metformin-Associated Lactic Acidosis (MALA)

Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induced by Metformin

The Role of Renal Dysfunction

Acidosis and the Impact on Cellular Function

Triggers and Predisposing Factors

Reframing the Lactate Threshold in MALA

Role of Renal Replacement Therapy

Clinical Implications and Lessons

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montagnani A, Nardi R. Lactic acidosis, hyperlactatemia and sepsis. Ital J Med. 15 déc 2016;10(4):282-8.

- Nnodum BN, Oduah E, Albert D, Pettus M. Ketogenic Diet-Induced Severe Ketoacidosis in a Lactating Woman: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. [cité 26 févr 2025]; Disponible sur. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2019/1214208.

- Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes - PubMed [Internet]. [cité 28 févr 2025]. Disponible sur. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25538310/.

- Metformin and lactic acidosis in diabetic humans - Lalau - 2000 - Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cité 28 févr 2025]. Disponible sur. Available online: https://dom-pubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1463-1326.2000.00053.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed.

- Seidowsky A, Nseir S, Houdret N, Fourrier F. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis: A prognostic and therapeutic study*: Crit Care Med. juill 2009;37(7):2191-6.

- The criteria for metformin-associated lactic acidosis: the quality of reporting in a large pharmacovigilance database - Kajbaf - 2013 - Diabetic Medicine - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cité 28 févr 2025]. Disponible sur. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/dme.12017.

- El-Mir MY, Nogueira V, Fontaine E, Avéret N, Rigoulet M, Leverve X. Dimethylbiguanide inhibits cell respiration via an indirect effect targeted on the respiratory chain complex I. J Biol Chem. 7 janv 2000;275(1):223-8.

- Davidson MB, Peters AL. An overview of metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. janv 1997;102(1):99-110.

- Andersen LW, Mackenhauer J, Roberts JC, Berg KM, Cocchi MN, Donnino MW. Etiology and Therapeutic Approach to Elevated Lactate Levels. Mayo Clin Proc. 1 oct 2013;88(10):1127-40.

- Lalau JD, Kajbaf F, Bennis Y, Hurtel-Lemaire AS, Belpaire F, De Broe ME. Metformin Treatment in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 3A, 3B, or 4. Diabetes Care. 5 janv 2018;41(3):547-53.

- Foretz M, Guigas B, Bertrand L, Pollak M, Viollet B. Metformin: From Mechanisms of Action to Therapies. Cell Metab. 2 déc 2014;20(6):953-66.

- Bench-to-bedside review: Lactate and the kidney | Critical Care | Full Text [Internet]. [cité 28 févr 2025]. Disponible sur. Available online: https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/cc1518.

- Kraut JA, Madias NE. Lactic Acidosis. N Engl J Med. 11 déc 2014;371(24):2309-19.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).