Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) as a Framework

2.6. Data Collection and Data Management

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Semi-Structured Interview Data

3.2.1. Complex System

“So special mode, part of the medical administration service, handles wheelchair and stretcher-bound transport for qualified and eligible individuals. It provides door-to-door service, bringing them from home or a facility to appointments and back…special mode has the secondary option of vending (ID: 1010).”

“I can't allow non-ambulatory individuals on the vehicle. We don't have a ramp, lifting device, or any moving equipment, and my volunteers are certainly not medical staff (ID: 1012).”

“We partnered with Uber on May 10th last year to provide transportation for ambulatory Veterans—those who can walk and self-assist. Before that, they only had mileage reimbursement (ID: 1004).”

“Now Veterans qualify for what's called Beneficiary Travel. To qualify, you have to meet certain criteria, you got to be service connected, at least 30% pension, and have an income below $16,500. Not every Veteran qualifies. Ambulatory Veterans, those who can walk and self-assist, previously only received mileage reimbursement, currently 41.5 cents per mile, for travel to and from appointments if eligible (ID: 1004).”

“We prioritize special mode trips first. My office assigns drivers to these trips. Everything else is vented out to a contractor. Trips cannot be vended if the individual does not meet special mode criteria (ID: 1006).”

“There are so many regulatory components to transportation and Beneficiary Travel that oftentimes there's more services available than is known. It is not as clear because it is complex because there's so many different layers of the regulations…And there's different requests for adjustments of regulations to open coverage that's going through the congressional process (ID: 1000).”

“If you join VTS and you sign up 100% and you take their money and you take their vehicles, you have to do everything exactly like they say. That doesn't work for our area. Our leadership is more like do what you gotta do to go out there and bring these folks in and take them home (ID: 1006).”

“The clinical inpatient team determines whether a Veteran is ambulatory or requires a wheelchair or stretcher. This information is then communicated to the social worker, who completes a trip ticket specifying the transportation needs—such as requiring oxygen, a stretcher, or a wheelchair—by checking the appropriate box on a form (ID: 1014).”

“The social work service handles transportation for individuals who do not qualify for special mode, primarily focusing on discharge transportation (ID1010).”

“The Office of Rural Health, we partner with the Veteran Transportation Program to support their VTS program at rural sites. We help provide the funding and the VTS provides vehicle support for the personnel to get them up and running (ID: 1000).”

“Veterans Experience Office, drills down on all transportation complaints and issues. When someone calls patient advocate, they send that complaint out to the service for service recovery, and I get the transportation ones (ID: 1006).”

“It comes down to stakeholders sitting down with leadership at the division or facility level and selling the intent. If we think it would be beneficial to station 1-2 drivers at a Community-Based Outpatient Clinic…being able to show based on data what the resource impact would be, both on a dollar side, because then we're not spending funds on 3rd party contractors, vendors, and ambulances, while also increasing access to care for veterans in areas that struggle…being able to sell that point and gain leadership buy in (ID: 1008).”

“We piloted a rural shuttle because everyone said there was a huge need in Levy, Gilchrist, and Dixie County for transportation. We worked on it for six months, meeting with VFW, DAV, and the American Legion and got authorization to launch. We spread the word, advertised, and told people to call if they needed a ride. In six months, we got one call, and it wasn’t even legit. It never really got off the ground. I know there’s a need, but when it comes down to it, it’s hard to… I don’t know, get folks to do it (ID1006).”

“I do know there's a hiccup using Uber and Lyft because the Veteran needs a smartphone, and that's not always the case with older generations (ID: 1006).”

“If a Veteran is very poor, has a car that doesn’t work, or lives 3 hours away from a specialty care appointment without a friend or family member to assist, they might not either be eligible for mileage reimbursement or Uber if they're not ambulatory. And that can potentially cause further health concerns for that Veteran if they're not getting the care they need. I would love it if the VA could say every Veteran gets a ride to every appointment, but some of our areas are very rural. Even if the Veteran is eligible for Beneficiary or special mode travel, there might not be a vendor who's available to go to those more rural areas (ID: 1014).”

3.2.2. Transportation Strengths

“The strength is that North Florida, South Georgia is like no other facility in the planet…and it should be its own service because we're that big (ID: 1006).”

“I can speak to what we provide, and one of our strengths is flexibility in transportation. If a need arises that we wouldn’t typically support, we reassess and find a way to help, considering the long-term impact. For example, if a patient from the Panhandle had surgery in Gainesville and initially had transportation but now needs it for a follow-up appointment, we may classify it as a one-time or until the need is over. We're very flexible here, that's one of the strengths (ID: 1010).”

“Because of the integrated nature of VA care, we have a better opportunity through the collaboration between the transportation program and social work to provide better coordinated care, especially in terms of identifying and addressing the social determinants of health (ID: 1002).”

“The Office of Rural Health and the Veteran Transportation Program work really well together. We both recognize how important the other is, and that’s a real strength (ID: 1000).”

“My side of the house provides door-to-door service, offering one-on-one support between the Veteran and VA staff. It is also probably tracked better (ID: 1006).”

“Many of our Veterans are disabled, and not all disabilities are visible. It's great that we have resources for both seen and unseen disabilities, something not always available to non-Veterans. That’s definitely a strength (ID: 1014).”

“There is diversity within the system, with staff-operated, volunteer-operated, and third-party-operated systems providing coverage. This variety in transportation options is a strength (ID: 1012).”

“One of the strengths is that the program is primarily staffed by Veterans. They have a commitment to service and to other Veterans, and because they are Veterans, they have military experience with transportation and logistics and program management, personnel management. It's very unique as it is truly Veteran owned and Veteran operated entity within the VA (ID: 1002).”

“The support of Veterans as drivers, and their components of the service really helps. The frontline drivers really connect with Veterans well. Having worked in a rehab department for 20 years, really was able to appreciate drivers connecting and being the inspiration for a Veteran to get to an appointment or an added comfort for a Veteran to go to their appointment, it’s really impressive and impactful (ID: 1000).”

“We monitor all training and driver physicals, they're held to a higher standard (ID: 1006).”

3.2.3. Transportation Weaknesses

“We can always use more resources, manpower, vehicles because the demand is crazy. Funding is another, right now we're in a budget crunch, so everything is kind of frozen. The reason why is because we have a community care. So, if I'm a Veteran and can’t get seen within 30 days, then we can outsource it into the community and the VA is on the stick to pay for that. That has become very expensive, just for North Florida, South Georgia, it's a $700 million expensive (ID: 1004).”

“It's because of staffing. Each morning, my team receives a list of 25 to 35 people from Jacksonville, but we only have two drivers. At best, they can take four to six trips, with three passengers each. And people also have to understand that schedule changes daily. It's driven by patient appointment (ID: 1006).”

“One of the primary weaknesses is staffing. There's a FTE neutral policy and it's because of funding. Because transportation isn’t in the forefront of leaderships’ perspective when thinking the whole health mindset, transportation falls to the wayside. If we can get 25 doctors, that's perfectly fine, but if we can't get the patients to see them, then that's a piece of the pie. Because that's not thought of, transportation does fall to the wayside a lot, and the first thing to take a hit is personnel (ID: 1008).”

“The problem with volunteers, they're not consistent. I love every one of them and I wanna volunteer when I retire in a few years, but as far as something like that, you're messing with the patient's appointments (ID: 1006).”

“It is a weakness in the sense that if a volunteer goes on vacation for three months, which happens quite regularly, we don't have a built in backup (ID: 1012).”

“DAV provides a great product. That's not ran through us. They provide an outstanding shuttle service. It's pretty robust, but after COVID-19 it's gone down. They can't fill the volunteers. Probably average age 60+, and once COVID-19 came through, I think it spooked them. They have a 10-passenger van that would come into Jacksonville, they have two vans. The Jacksonville to Gainesville van would come in loaded every single day, five days a week, and now they don't even have the volunteers to move it every single day anymore. So, there's some holes that are developing within this catchment area (ID: 1010).”

“There’re administrative and clinical criteria that has to be met for Veterans to be eligible for that program, and that can sometimes affect a Veteran's access to care (ID: 1014).”

“We can do a better job communicating the criteria of what makes a Veteran eligible for certain programs within the VA, specifically regarding transportation (ID: 1014).”

3.2.4. Autonomous Ride-Sharing Services Opportunities

“It would open up the pool of employees that could successfully help with the transportation, so that would be helpful (ID: 1000).”

“It would provide a better resource for Veterans to have that consistent point of access in a city or town…all they have to do is show up to one of the stops, get on and away they go (ID: 1008).”

“It would be good if it could help rural Veterans get to their final urban track of their ride to make that standardized and less stressful (ID: 1000).”

“On a smaller scale to where it can be within the hospital because we have a lot of Veterans because our campus is so big, where we can have little routes to where they can jump on and jump off. Whether because they are handicap or just because they are running late. We can utilize it into parking, if it's something that can monitor the parking and pick people up. Even something for the employees, not just for the Veterans, to make their jobs easier to get to where they need to and navigate throughout the hospital or campus and even off site at surrounding locations (ID: 1004).”

“Knowing that they can be geofenced it would benefit in metropolitan areas. Autonomous vehicles would be extraordinarily beneficial in a large metropolitan area, because is much easier to maintain. There's a lot more accessible information; cell towers are popping up everywhere (ID: 1008).”

“Huge walkable developments, developed communities of Veterans, it would have to still be within the confines of a Veteran community to where this automated system would take folks, not just to medical appointments, but also to things like shopping for groceries, dining, entertainment, physical activity, and parks to address everything in terms of social determinants, get access to food, access to education and medical. And meeting all the other basic needs (ID: 1002).”

3.2.5. Autonomous Ride-Sharing Services Threats

“Their trips are so varied; they don't have similar routes to be able to have a shuttle to go back and forth on a standardized route. For it to be a level 4 would have to be close to the VA. For the level 4, it had to be like specific geographical components and rural Veterans have such variety of road conditions, the distance, the terrain… it's gonna be the topography whether impacts distance (ID: 1000).”

“It is being ran on satellites or some kind of tower control and is that going to be an issue in rural areas (ID: 1010).”

“Their primary concern would be safety and connectivity. We have tablets that drivers use that connect via satellite and cell towers for GPS connectivity and connecting with the Vet ride system. Even we encounter connectivity issues where they lose connection with the satellite or cell tower. It’s concerning because we lose some of that trip information. The tablets capture drive time, they capture a plethora of information whenever transporting Veterans. Knowing that we’ve that shortfall and that recurring issue is a concern when it comes to an autonomous vehicle that doesn't have a physical person that can troubleshoot on the fly (ID: 1008).”

“I could see it for fixed routes ambulatory only. But on my fixed routes, all vehicles have wheelchair lifts. So, if you started an autonomous vehicle on that route, well, and the first time someone has a wheelchair, what do you do? You have more folks needing transportation that have a rollator, wheelchair, scooter or power chair than are ambulatory (ID: 1006).”

“I could not right now foresee a vehicle without a person in it in case a Veteran needed assistance because so many times our drivers do that. There’re so many times that they go above and beyond to help a Veteran in need, to get higher level care. I would definitely advocate for somebody being in the vehicle at all times (ID: 1000).”

“If there's no driver, I think that may cause anxiety or add additional stress for any Veteran, regardless of their age. Our Veterans are very different population, and many have been through very traumatic events. They potentially could be more stressed out if getting into this vehicle and no one’s in here or how they know they're taking me to the right place or how do I know I'm going to be on time for my appointment. I think there are too many unknowns (ID1014).”

“We have more older Veterans than younger. We have younger Veterans who might be, oh, this technology is amazing. However, most of our Veterans that do require assistance with transportation are older Veterans and I believe that many of our older Veterans wouldn't be completely comfortable with a level 4-5 autonomous vehicle because they have a lot of older school thinking. Most will prefer to do a paper survey over a computer survey. Many don't still have access to email. Many of our older Veterans don't use my healthy Vet secure messaging, so they're not always thinking that technology is a great thing. Even if it is a great thing, they're not utilizing it. So, our bigger Veteran population that utilizes transportation here would not be on board with a Level 4-5 automated vehicle (ID: 1014).”

“I'm sure there's gonna be something where the Vets gotta hit a link and approve it. Because now you're approving transportation for yourself. There's probably something with a manifest, so I'm going to click this link. Not everybody is tech savvy. A lot of the Vets in this area are homeless…so now you're assuming that they have a cell phone (ID1010).”

3.2.6. Communication

“The transportation program has done a fantastic job at the local level of educating Veterans, providers, and administrative staff that there are transportation services available. Often, it's not an issue that Veterans don't know they can get a ride, they just don't know necessarily the best person to contact to schedule that appointment, and they almost 99% want to speak to a person on the telephone. So, it's more a matter of making sure they are connected to the right person to help them identify what transportation benefits they are eligible for…so we need to make sure that the connection is happening and the benefits are being given to the right Veterans at the right time to make sure they're getting to their appointment (ID: 1002).”

“We try to get the guidance out to the Veterans first to make sure what the criteria is for them to qualify...But once they know we put out guidance on Facebook, all the websites, and even provide literature here in terms of flyers and brochures so that they're aware of it (ID: 1004).”

“We don't have a lot of discussions with Veterans. Sometimes they'll sneak through and find our number, but everything that we do is a support, a function. How does anybody find out or get our name? Realistically, it's not out there. The only ones that need to know, know. If Veterans find out, you put them on a carousel, and I don't like doing that. Because they'll call here and be like you need to call this place. And they tell me, oh, I don't feel like getting bounced around, you're like the 5th call, but we don't have the tools in our department to check if they're truly qualified as in VA need (ID: 1010).”

“The current strengths I would say, communication probably is one of them. Logistically we communicate, and we collaborate with all the different sections to try to make things happen no matter what the demand is. A lot of it is just real strong communication with the other sites and even outside of our region to make sure we take care of our patients (ID: 1004).”

“The biggest barrier is sometimes the impatient team doesn't communicate to the social worker when the Veteran's gonna be ready for discharge. So, there might be a last-minute trip that comes in that might need to go six hours, our catchment area is very large and our Veterans come to this facility and our Lake City facility from all over our catchment area. Our catchment area is close to 14 thousand square miles and that's a huge geographical area to cover, 50 counties going into South Georgia, North Florida. So, if they don't tell us in a timely fashion that an escort is needed, sometimes we may have a delay in the discharge because it might be too late in the day to set up a transportation for the same day. That is a barrier (ID: 1014).”

3.2.7. Suggestions for Improvement

“One thing that would be really helpful is to have the Veteran transportation service program at all facilities because that service is for all Veterans, regardless of their service connection. So, you don't have to be eligible for anything other than that you're a Veteran. So that makes it more streamlined. There's one place to go for the rides and then if there's not enough services to meet the demand, then it would be very clear (ID: 1000).”

“From a transportation standpoint, I think it would be good because we have separate departments. If we would put it all under one stop shop, so even the communication is good as it is, it can be better because we're in one area. So, I think there's a lot of redundancy that we can minimize that for us to be more optimal in their care and the services that we give (ID: 1004).”

“With transportation operations that includes the VA drivers themselves one of the things that helps us save money is it would be more conducive for us to hire more drivers to go take care of the need of the Veteran and have more control versus paying a vendor so much more money under contracts to get that done (ID: 1004).”

“We can do a better job with communicating the criteria of what makes a Veteran eligible for certain programs within the VA, specifically regarding transportation. It would be great if we had better communication in terms of our public affairs sending out information. Did you know that you might be available for travel reimbursement if you meet this criteria? Or did you know that you might be eligible to receive a ride via Uber, Lyft, or ride-share or some other program if you meet this criteria? Most problems revolve around communication or a lack of communication. We could do better with educating and informing veterans of what they might be eligible for (ID: 1014).”

“There's a lot of phone calls, emails, teams back and forth which waste time. I think there's a way that you could build a huge communications nucleus and put everybody in the same area where they can just say, hey man, do you know, can you look this up, is this good, and talking across aisles is a lot faster than making multiple phone calls or teams messages (ID: 1010).”

“We need a broader sense of communication with alternate stakeholders. Being able to communicate with the staff services or third-party services. To be able to say, we have a run of six patients coming out of Jacksonville, I do not have a driver. Here is the manifest, here is the point of contacts and having that level of communication would allow them to kind of encompass on a day that we may fall short (ID: 1012).”

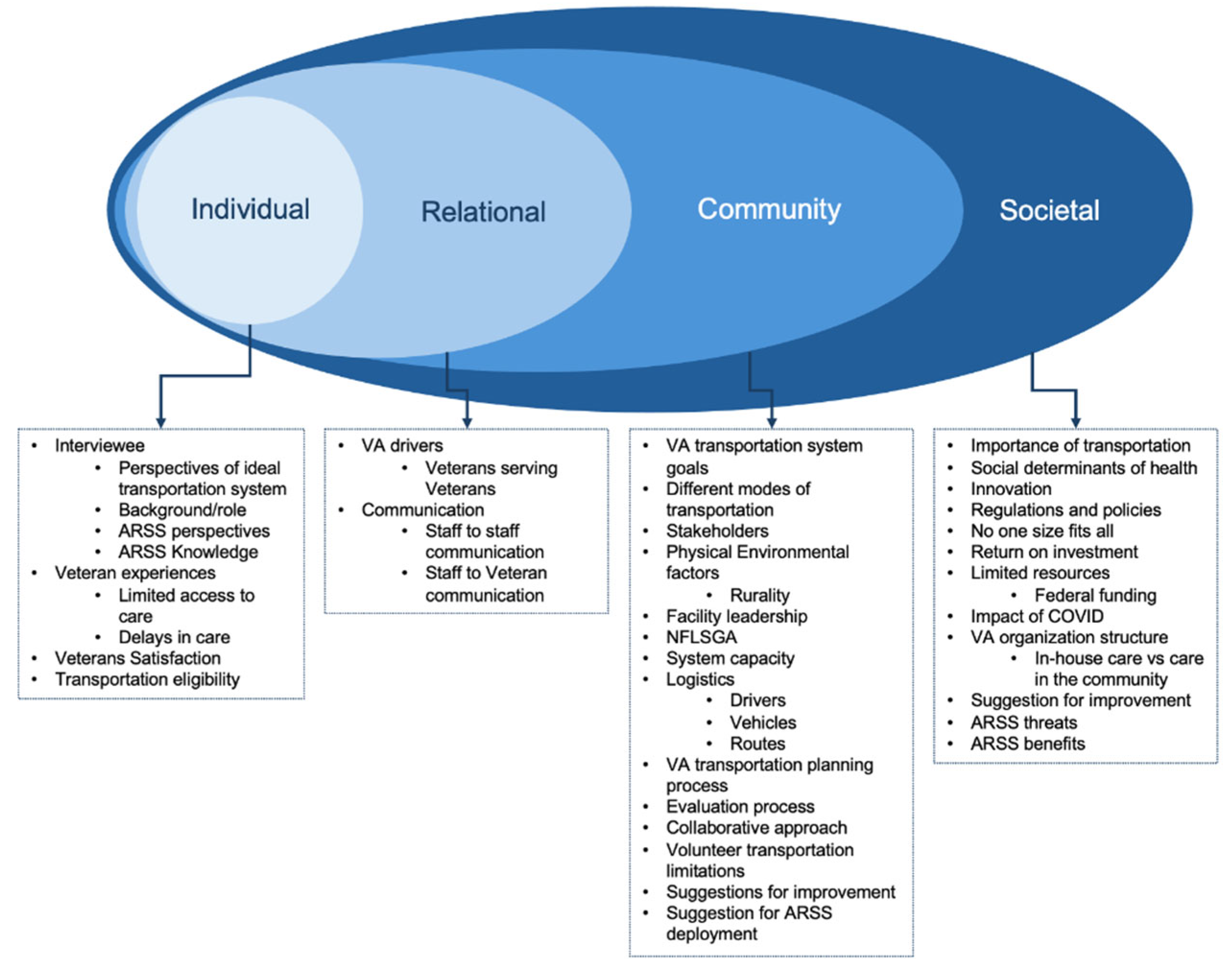

3.3. Findings Related to the Socio-Ecological Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. About the department: Veterans health care. 2025. Available online: https://department.va.gov/about/#:~:text=VA's%20Veterans%20Health%20Administration%20is:million%20enrolled%20Veterans%20each%20year (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration: About VHA. 2025. Available online: https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Highly Rural Transportation Grants [Fact Sheet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.va.gov/HEALTHBENEFITS/resources/publications/IB10-761_VA_HRTG_factsheet.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Transportation Service (VTS). 2019. Available online: https://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/vtp/veterans_transportation_service.asp (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Burkhardt, J. E., Rubino, J. M., & Yum, J. Improving Mobility for Veterans; Transportation Research Board, 2011. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/14507.

- Brownley, J., Welch, P., & Stabenow, D. Brownley, Welch, and Stabenow introduce legislation to increase travel reimbursement for veterans [Press Release]. 2023. Available online: https://juliabrownley.house.gov/brownley-welch-and-stabenow-introduce-legislation-to-increase-travel-reimbursement-for-veterans/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Hussey, P.S., Ringel, J.S., Ahluwalia, S., Price, R.A., Buttorff, C., Concannon, T.W., Lovejoy, S.L., Martsolf, G.R., Rudin, R.S., Schultz, D. and Sloss, E.M. Resources and capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide timely and accessible care to veterans. Rand Health Quarterly 2016, 5(4), 14. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5158229/.

- Shen, Y., Zhang, H., & Zhao, J. Integrating shared autonomous vehicle in public transportation system: A supply-side simulation of the first-mile service in Singapore. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2018, 113, 125-136. [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, A., Samaras, C., Hendrickson, C.T., Matthews, H.S. and Wong-Parodi, G. Integrating public transportation and shared autonomous mobility for equitable transit coverage: A cost-efficiency analysis. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 2022, 14, 100571. [CrossRef]

- Hwangbo, S.W., Stetten, N.E., Wandenkolk, I.C., Li, Y. and Classen, S. Lived experiences of people with and without disabilities across the lifespan on autonomous shuttles. Future Transportation 2024, 4(1), 27-45. [CrossRef]

- Classen, S., Wandenkolk, I.C., Mason, J., Stetten, N., Hwangbo, S.W. and LeBeau, K. Promoting veteran-centric transportation options through exposure to autonomous shuttles. Safety 2023, 9(4), 77. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & Doerzaph, Z. Road user attitudes toward automated shuttle operation: Pre and post-deployment surveys. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2022, 66(1), 315-319. [CrossRef]

- Benyahya, M., Kechagia, S., Collen, A., & Nijdam, N. A. The interface of privacy and data security in automated city shuttles: The GDPR analysis. Applied Sciences 2022, 12(9), 4413. [CrossRef]

- Tisdell, E. J., Merriam, S. B., & Stuckey-Peyrot, H. L. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Lohn Wiley & Sons, San Francisco, CA, 2025.

- Kahlke, R.M. Generic qualitative approaches: Pitfalls and benefits of methodological mixology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2014, 13(1), 37-52. [CrossRef]

- Portney, L. G., & Watkins, M. P. Foundations of clinical research: Applications to practice. Pearson/Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2009.

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Sage, 2002.

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1961, 32(1), 148-170. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2237615.

- MacDougall, C., & Fudge, E. Planning and recruiting the sample for focus groups and in-depth interviews. Qualitative Health Research 2001, 11(1), 117-126. [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, A., & Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Social Science & Medicine 1995, 41(12), 1667-1676. [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge, NY, 1967. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H. and Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity 2018, 52, 1893-1907. [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M. and Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine 2022, 114523. [CrossRef]

- Archibald, M.M., Ambagtsheer, R.C., Casey, M.G. and Lawless, M. Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2019, 18. [CrossRef]

- Gurl, E. SWOT analysis: A theoretical review. Journal of International Social Research 2017, 10(51), 994-1006. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Security and Compliance for Microsoft Teams. 2025. Available online: https://www.safeguardcyber.com/platform/channels-we-protect/ms-teams?gclid=CjwKCAjw__ihBhADEiwAXEazJg21St8fe43jrZFOLif7IxSFdC-oHHQvLoLixVcuuTJp0edXqrQmEBoCibgQAvD_BwE (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Thunberg, S. and Arnell, L. Pioneering the use of technologies in qualitative research–A research review of the use of digital interviews. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2022, 25(6), 757-768. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.R. Kielhofner's research in occupational therapy: Methods of inquiry for enhancing practice. FA Davis, 2017.

- Parekh, T., Kumar, B.V., Maheswar, R., Sivakumar, P., Surendiran, B. and Aileni, R.M. Intelligent transportation system in smart city: A SWOT analysis. In Challenges and Solutions for Sustainable Smart City Development, Springer, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2023. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 12) [Computer Software]. 2018.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3(2), 77-101. [CrossRef]

- Kondracki, N.L., Wellman, N.S. and Amundson, D.R. Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2002, 34(4), 224-230. [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. and Field, P.A. Nursing research: The application of qualitative approaches. Nelson Thornes, 1995.

- Krefting, L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 1991, 45(3), 214-222. [CrossRef]

- Knafl, K.A. and Breitmaye, B.J. Triangulation in qualitative research: Issues of conceptual clarity and purpose. In Qualitative Nursing Research: A Contemporary Dialogue, JM Morse, Aspen, Rockville, MD, 1991.

- Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage, 1994.

- Buzza, C., Ono, S.S., Turvey, C., Wittrock, S., Noble, M., Reddy, G., Kaboli, P.J. and Reisinger, H.S. Distance is relative: Unpacking a principal barrier in rural healthcare. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2011, 26, 648-654. [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.T., Gerber, B.S. and Sharp, L.K. Traveling towards disease: Transportation barriers to health care access. Journal of Community Health 2013, 38, 976-993. [CrossRef]

- Washington, D.L., Bean-Mayberry, B., Riopelle, D. and Yano, E.M. Access to care for women veterans: Delayed healthcare and unmet need. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2011, 26, 655-661. [CrossRef]

- Zullig, L.L., Jackson, G.L., Provenzale, D., Griffin, J.M., Phelan, S. and Van Ryn, M. Transportation—A vehicle or roadblock to cancer care for VA patients with colorectal cancer? Clinical Colorectal Cancer 2012, 11(1), 60-65. [CrossRef]

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Rural Health: Rural Veterans. 2024. Available online: https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Burkhardt, J.E., Rubino, J.M. and Yum, J. Improving Mobility for Veterans. Transportation Research Board, 2011. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/14507.

- Zhang, W., Guhathakurta, S., Fang, J. and Zhang, G. The performance and benefits of a shared autonomous vehicles based dynamic ridesharing system: An agent-based simulation approach. In Transportation Research Board 94th Annual Meeting, 2015.

- Schlüter, J., Bossert, A., Rössy, P. and Kersting, M. Impact assessment of autonomous demand responsive transport as a link between urban and rural areas. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2021, 39, 100613. [CrossRef]

- Prioleau, D., Dames, P., Alikhademi, K. and Gilbert, J.E. Autonomous vehicles in rural communities: Is it feasible? IEEE Technology and Society Magazine 2021, 40(3), 28-30. [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, H. Planning for the first and last mile: A review of practices at selected transit agencies in the United States. Sustainability 2021, 13(4), 2222. [CrossRef]

- Carney, C., Johnson-Kaiser, T. and Ahmad, O. Automated Vehicles in Rural America: What’s the Holdup? Transportation Research Board 2023, 347, 8-12. https://www.trb.org/Publications/Blurbs/183152.aspx.

- Bezyak, J.L., Sabella, S.A. and Gattis, R.H. Public transportation: An investigation of barriers for people with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 2017, 28(1), 52-60. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R., Vijaygopal, R. and Kottasz, R. Attitudes towards autonomous vehicles among people with physical disabilities. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2019, 127, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Dicianno, B.E., Sivakanthan, S., Sundaram, S.A., Satpute, S., Kulich, H., Powers, E., Deepak, N., Russell, R., Cooper, R. and Cooper, R.A. Systematic review: Automated vehicles and services for people with disabilities. Neuroscience Letters 2021, 761, 136103. [CrossRef]

- Dianin, A., Ravazzoli, E. and Hauger, G. Implications of autonomous vehicles for accessibility and transport equity: A framework based on literature. Sustainability 2021, 13(8), 4448. [CrossRef]

- Cacace, S., Smith, E., Desmarais, S. and Alders, E. Locale matters: Regional needs of US military service members and veterans. Military Behavioral Health 2022, 10(3), 221-234. [CrossRef]

- Parvanta, C., Nelson, D.E. and Harner, R.N. Public health communication: Critical tools and strategies. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2017.

| Themes/Subthemes | Operational Definitions of Themes and Subthemes |

| Complex System | The VA transportation system consists of multiple interconnected components, including the various modes of transportation, regulatory frameworks, diverse stakeholders, processes of change, and access to care. Each element contributes to the system’s complexity and functionality. |

| Different modes of transportation | Includes special mode transport for wheelchair and stretcher-bound patients, Uber/Lyft and volunteer services for ambulatory Veterans, and Beneficiary Travel for travel reimbursement. MAS outsources to vendors for trips to Veterans that are special mode. Each mode of transportation addresses different needs. |

| Regulations and policy | The regulatory structure is complex, involving multiple layers of rules and guidelines that influence funding, programs, and standard operating procedures for day-to-day operations. This complexity often leads to challenges in service provision, requiring flexibility and adaptation by transportation services. |

| Diverse stakeholders | The system involves Veterans, caregivers, healthcare personnel, the ORH, the Veterans Experience Office, and community partners such as the Disabled American Veterans (DAV). Stakeholders have a unique role in determining transportation needs, organizing services, managing complaints and working toward service improvements. |

| Process of change | The VA is integrating new technologies and piloting new services to improve accessibility. Challenges include technology reliance, coordination issues, and engagement difficulties. Efforts focus on identifying transportation deserts, expanding resources, and overcoming barriers to enhance service provision. |

| Access to care | Reliable transportation impacts Veterans' health outcomes by providing access to primary, specialty, and mental health services. High outsourcing costs emphasize the need to bring care back to VA facilities. Strict eligibility criteria and limited service availability pose significant barriers, especially in rural areas. |

| Transportation Strengths | Strengths include the NFLSGA unique ability to provide a wide range of flexible and adaptive transportation services. Strong collaboration between various transportation departments and external contractors. Personalized, high-quality services facilitated by trained and dedicated drivers, many of whom are Veterans themselves. |

| NFLSGA unique | NFLSGA is unique due to its geographic reach and the range of services it offers. It is flexible and adaptable and transport those who may not qualify under Beneficiary Travel criteria. The integration of services under one umbrella allows NFLSGA to cater to a wide array of needs, making it distinct from other facilities. |

| Collaborative approach | Collaborative efforts with various stakeholders such as social workers, nurses, and external contractors. This integrated approach ensures coordinated care and addresses the social determinants of health by working closely with all stakeholders involved in Veterans' healthcare. |

| Better customer service product | The VA transportation services are tailored to Veterans' needs, providing door-to-door service, better tracking, and higher safety standards. This personalized approach enhances Veterans overall experience. |

| Drivers working for the VA | The employment of Veterans as drivers, who share a unique bond and understanding with their passengers. This Veteran-to-Veteran interaction provides comfort and encouragement to Veterans. The high training standards and commitment to service further enhance the reliability and quality of the transportation provided. |

| Transportation Weaknesses | Limited resources, such as insufficient funding, manpower, and vehicles. Reliance on volunteer transportation presents challenges, including inconsistency, and restrictions on the types of patients that can be transported. Strict eligibility criteria further complicate access to transportation services. |

| Limited resources | Insufficient manpower, vehicles, and funding to meet the transportation demands of Veterans. This impacts the ability to provide timely and effective transportation services, as highlighted by the constraints of staffing and vehicle availability due to budget cuts and funding limitations. |

| Volunteer transportation limitations | Challenges in relying on volunteers for transportation services, including inconsistency of volunteer availability, lack of medical training, and restrictions on the types of patients they can transport. |

| Eligibility | Strict criteria that Veterans must meet to qualify for certain transportation services. The criteria often exclude Veterans who do not meet specific administrative or clinical requirements, thereby limiting their access to transportation services and impacting their access to healthcare. |

| ARSS Opportunities | Potential advantages and strategic recommendations for deploying ARSS. Perceived benefits include increased efficiency, resource reallocation, and improved accessibility for underserved populations. Suggestions for deployment include its integration in urban areas and hospital campuses. |

| Perceived benefits | Perceived benefits include the potential for increased efficiency and resource allocation within transportation services. By automating aspects of transportation, human resources can potentially be reallocated to other tasks. ARSS may improve accessibility for Veterans by providing consistent and reliable transportation options. |

| Suggestions for ARSS deployment | Implementing fixed routes, focusing on short trips, and providing transportation services in small communities. Serving able and ambulatory Veterans and deployment in urban areas as a last leg of trip. Incorporating ARSS in hospital campuses and parking lots may benefit both Veterans and employees. |

| ARSS Threats | The ARSS threats are the potential challenges and barriers that could impede the effective implementation and operation of ARSS. These threats encompass logistical, accessibility, and adoption issues. |

| ARSS logistics | Limited application for rural Veterans due to varied trips and geographical components. Funding limitations, connectivity issues, road conditions, operation constraints and the suitability of vehicles for different terrains and weather conditions, and limited reach due to reliance on fixed routes. |

| Serving PWDs | Serving PWDs in the context of ARSS involves ensuring that these services are accessible and accommodating to individuals with mobility challenges. This includes having personnel available to assist, which may be challenging with AVs that lack onboard staff to help with wheelchairs, scooters, or other assistive devices. |

| ARSS adoption | Factors influencing adoption include trust in the technology, comfort levels with driverless vehicles, and the perceived reliability of these services. This is particularly challenging for older Veterans, those living in rural areas, homeless Veterans and those with no access to technology or limited technological proficiency. |

| Communication | Encompasses the methods and effectiveness of information exchange between staff members and between staff and Veterans. It involves ensuring that all parties are informed about transportation options, eligibility criteria, scheduling processes, and service availability. |

| Staff to staff communication | Effective communication is important for coordinating transportation for Veterans. Challenges include timely communication between inpatient teams and social workers, which can delay discharges. Regular and structured communication among departments is needed to ensure smooth operations and timely transportation services. |

| Veteran and staff communication | Clear communication between Veterans and VA staff ensures Veterans are aware of the transportation services available to them and understand the eligibility criteria. This involves disseminating information through various channels and ensuring Veterans are connected to the right personnel for scheduling transportation. |

| Suggestions for Improvement | Streamline services by integrating departments under a unified system. The focus is on reducing redundancy, improving coordination, and ensuring that Veterans have better access to transportation options through clear eligibility criteria and efficient scheduling processes. |

| Streamline services | Consolidate departments and services under a unified system to reduce redundancy and improve efficiency. By centralizing services, the VA can enhance coordination, reduce operational delays, and better manage resources. This also includes hiring more drivers and transportation staff and reducing reliance on external vendors. |

| Communication strategies | Enhancing communication strategies includes improving internal communication within the VA and external communication with Veterans. Developing a centralized communication hub and utilizing public affairs to disseminate information about transportation eligibility and services can improve awareness and access. |

| Theme | Subthemes | Take-Home Messages |

| Complex System | Different modes of transportation, Regulations and policy, Diverse stakeholders, Process of change, Access to care | The VA transportation system is multifaceted, involving a variety of transportation options, regulatory challenges, diverse stakeholders, ongoing changes, and access to care issues. Flexibility and adaptability are important in addressing these complexities. |

| Transportation Strengths | NFLSGA unique, Collaborative approach, Better customer service product, Drivers working for the VA | Strengths include the unique aspects of the NFLSGA system due to its geographical size and transportation flexibility; a collaborative care model; personalized customer service; and the employment of Veterans as drivers, enhancing satisfaction and service quality. |

| Transportation Weaknesses | Limited resources, Volunteer transportation limitations, Eligibility | Weaknesses include funding constraints, a shortage of staff and drivers, inconsistency and reliability issues with volunteer drivers, and restrictive eligibility criteria. Addressing staffing shortages and budget constraints is essential for improving service delivery. |

| ARSS Opportunities |

Perceived benefits, Suggestions for ARSS deployment | ARSS may expand the pool of transportation employees, provide reliable access points in urban areas, and assist rural Veterans by standardizing and easing final leg journeys. ARSS may alleviate staffing constraints and offer a reliable solution for short trips. |

| ARSS Threats | ARSS logistics, Serving PWDs, ARSS adoption | Threats include logistical challenges in rural areas, connectivity and safety issues, the ability to serve Veterans with disabilities, and adoption barriers due to trust and technology acceptance issues. Threats need to be addressed to support ARSS implementation. |

| Communication | Staff to staff communication, Veteran and staff communication | Effective communication between Veterans and staff, as well as among staff members, is important for ensuring awareness and coordination of transportation services. Improving communication strategies can enhance service delivery and Veteran satisfaction. |

| Suggestions for Improvement | Streamline services, Communication strategies | Streamline services by implementing the VTS program at all facilities or consolidating departments into a centralized unit to reduce redundancy and improve efficiency. Hire more drivers and enhance communication about eligibility criteria. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).