Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

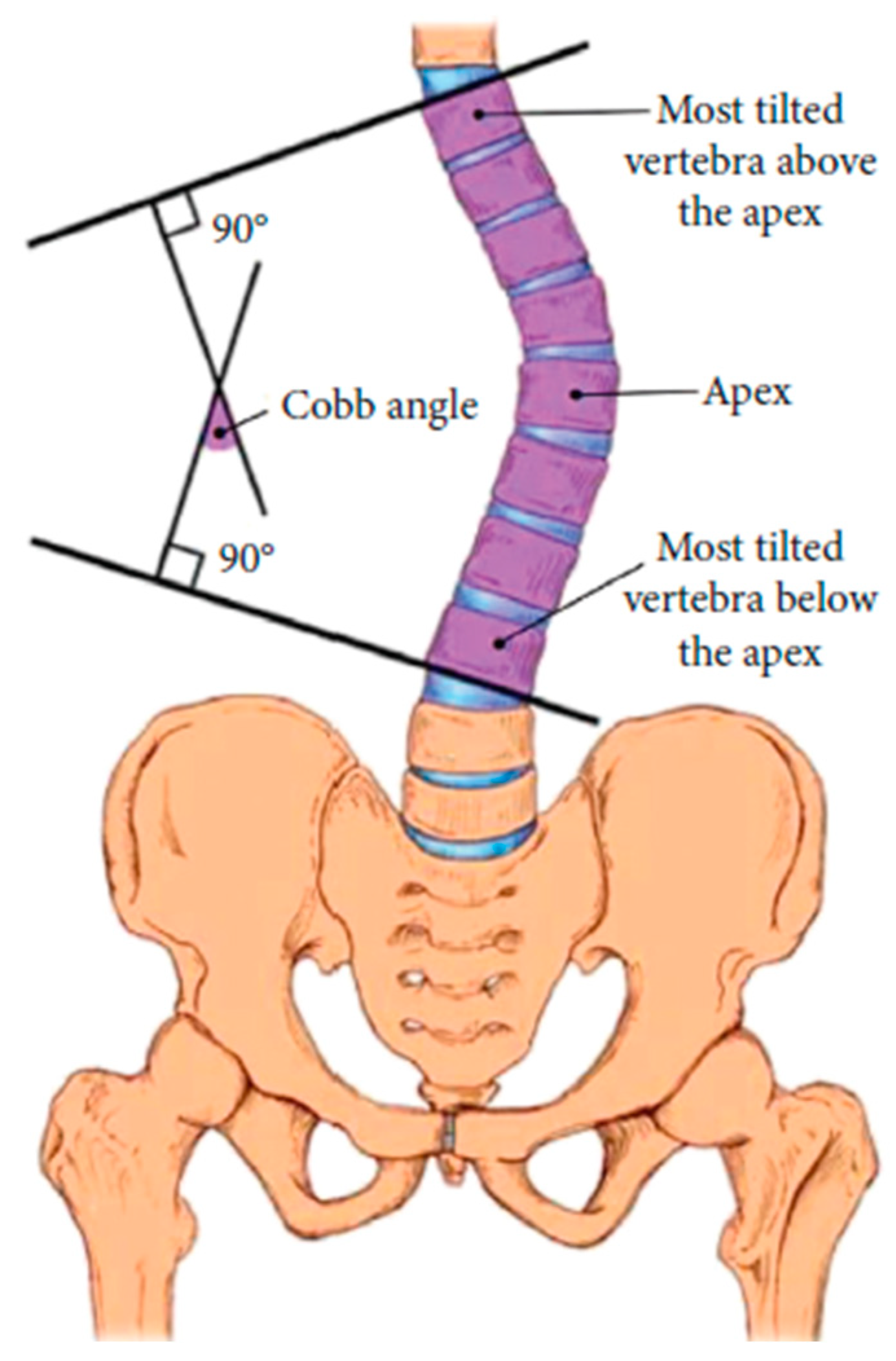

| Cobb angle | Definition |

|---|---|

| 0º - 10º | Spinal curve |

| 10º - 20º | Mild scoliosis |

| 20º - 40º | Moderate scoliosis |

| > 40º | Severe scoliosis |

2. Related Works

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Method

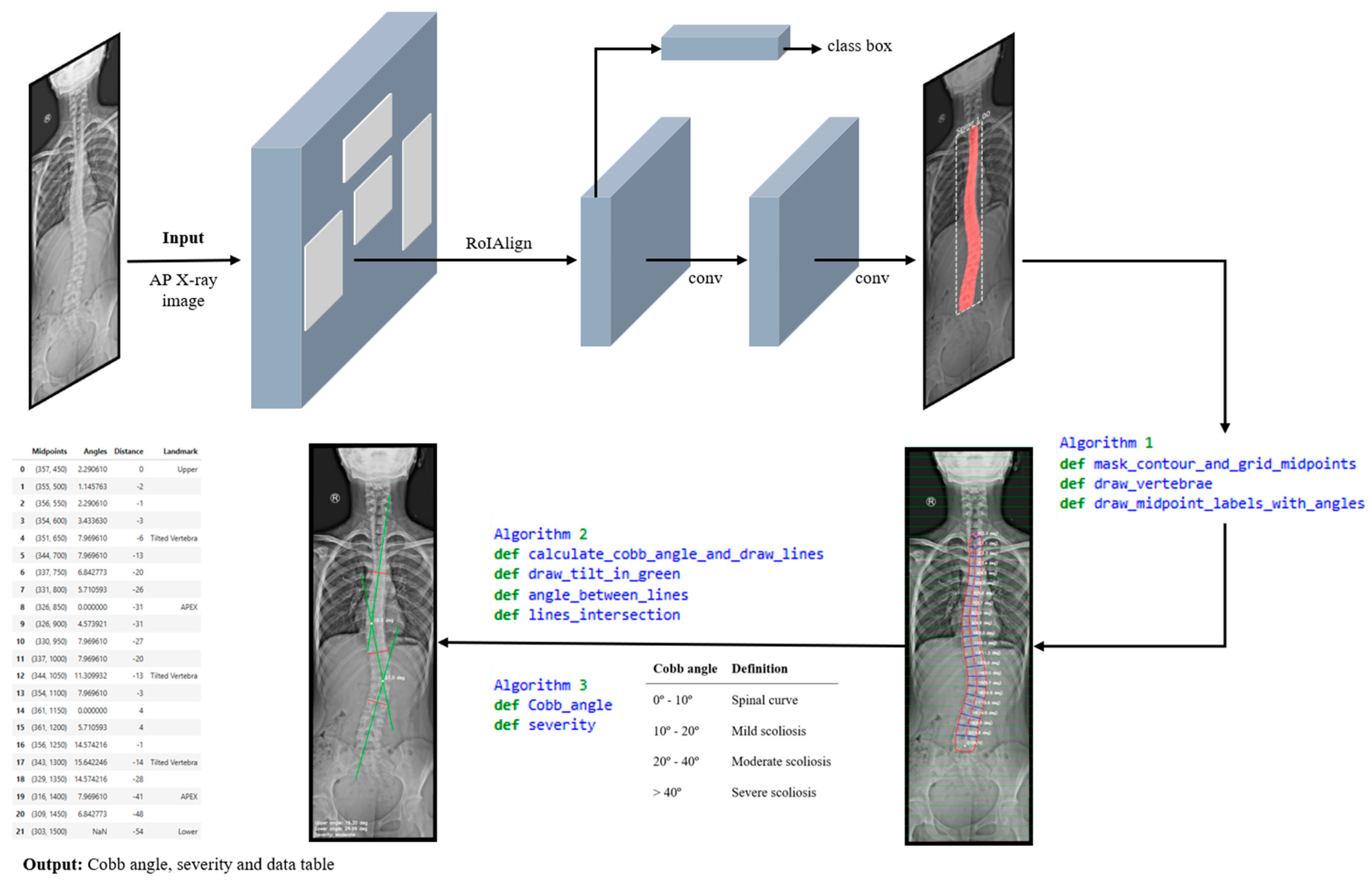

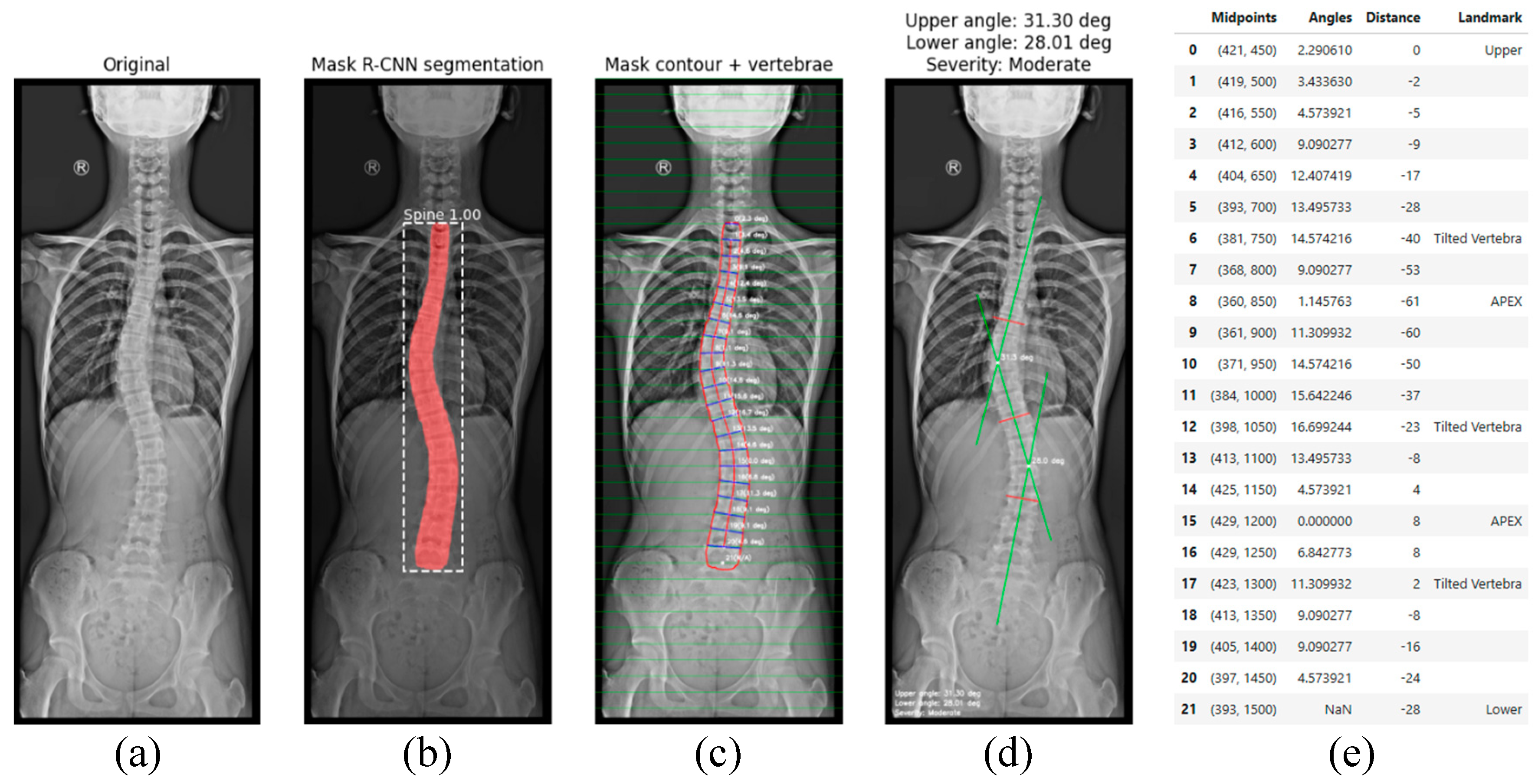

- Image acquisition and preprocessing is presented in Figure 6(a). The process begins with image acquisition through a user interface that allows the upload of an anterior–posterior (AP) full spine X-ray image.

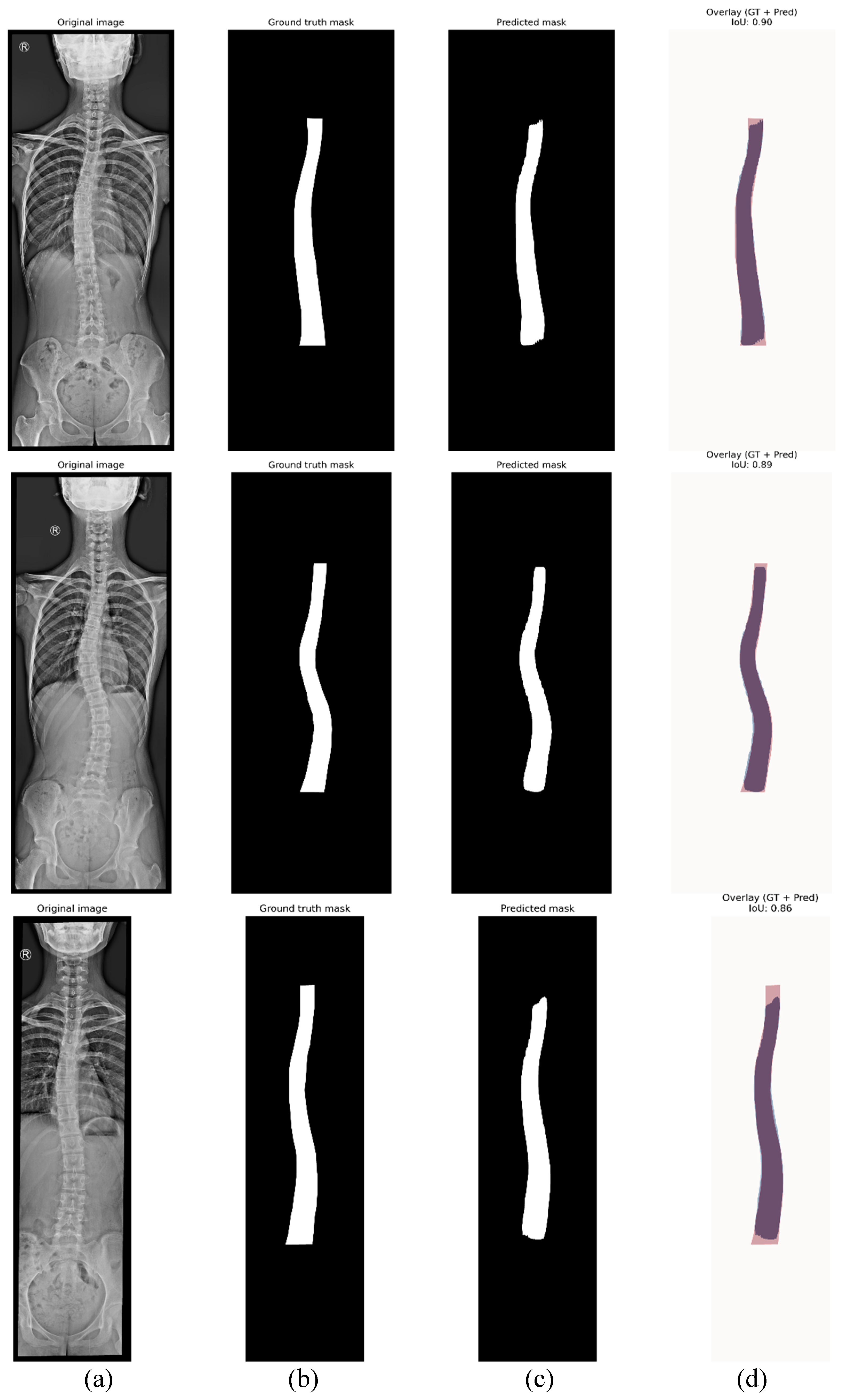

- Figure 6(b), shows the step corresponding with spinal segmentation using Mask R-CN. A pre-trained Mask R-CNN model is employed to perform instance segmentation of the spine. The model is loaded, and inference is conducted on the input image. To enhance segmentation reliability, only masks with a confidence score above a predefined threshold are retained. Among the detected regions, the mask with the largest segmented area is selected as the spinal region, assuming it corresponds to the spine. This approach ensures higher segmentation accuracy, reduces false positives, and improves spinal contour extraction. The accuracy of the proposed method in Cobb angle quantification and severity classification is highly dependent on the precision of generated mask. The more accurate the mask, the more precise the assessment.

- In Figure 6(c), contour extraction and midpoint detection are illustrated. Once the segmentation mask is obtained, the spinal contour is extracted using OpenCV’s cv2.findContours() function, which is employed for contour detection in binary images. The contour with the largest segmented area is identified and overlaid onto the image for visualisation. To represent the spinal curve, a grid of horizontal lines is drawn in the image with a predefined interval of 50 pixels. This interval was selected as all images have been scaled to a standardised height of 2000 pixels. The interface also provides a widget to adjust the grid interval, offering flexibility in measurement refinement. The grid interval is designed to keep the generated midline within the boundaries of individual vertebrae, which is essential for providing a simplified representation of the spine. At each grid line, two intersection points are detected where the line crosses the spinal mask contour. The distance between these two points is measured, and its mean position is calculated, defining the midpoint in the image. These midpoints serve as a key reference points for spinal curve estimation.

- Figure 6(d), depicts spinal curve estimation and Cobb angle calculation. In this step, the extracted midpoints are used to approximate the spinal curve, with the first and last midpoints identified as upper and lower, respectively. A spline interpolation is applied to refine the connections between midpoints, providing a more accurate approximation of the spinal curvature. At each midpoint, except for upper and lower, a perpendicular line is drawn relative to the tangent of the curve at that point. The inclination angle of these perpendicular lines with respect to the horizontal is then computed and annotated on the corresponding midpoints. These perpendicular lines, referred to as simplified vertebrae, allow for a visual assessment of the spinal curvature trend, facilitating an intuitive evaluation of scoliosis progression and severity. Based on the curvature analysis, key anatomical landmarks are identified, including tilted vertebrae and apex points. Tilted vertebrae are defined as those with the most pronounced inclination angles, representing the regions of greatest spinal deviation. Apex points, on the other hand, correspond to the locations where the spinal curve reaches its maximum deformation, characterised by the greatest lateral displacement relative to the upper reference point. These apex points are critical for scoliosis assessment, as they indicate the peak of the spinal misalignment. The Cobb angle is then computed by isolating perpendicular lines corresponding to the most tilted vertebrae, drawing representative lines that emulate the manual method, identifying the intersection point between these lines, and measuring the angle formed at their intersection.

- Finally, the visualization and data export stage is presented in Figure 6(e). The results are displayed in a multi-panel layout including: the original X-ray image; the segmentation mask; the extracted spinal contour with the computed midpoints, midline, and vertebral inclination; the image showing Cobb angle measurement and severity classification; and finally, the data table containing numerical values including anatomical landmarks such as tilted vertebrae, upper, lower and apex points. Processed images and the data table are exported as structured reports in .png and .csv formats, providing a comprehensive representation of the entire process. This facilitates data-driven monitoring and assessment of scoliosis progression, offering valuable insights for clinical experts.

4. Experimental Analysis and Results

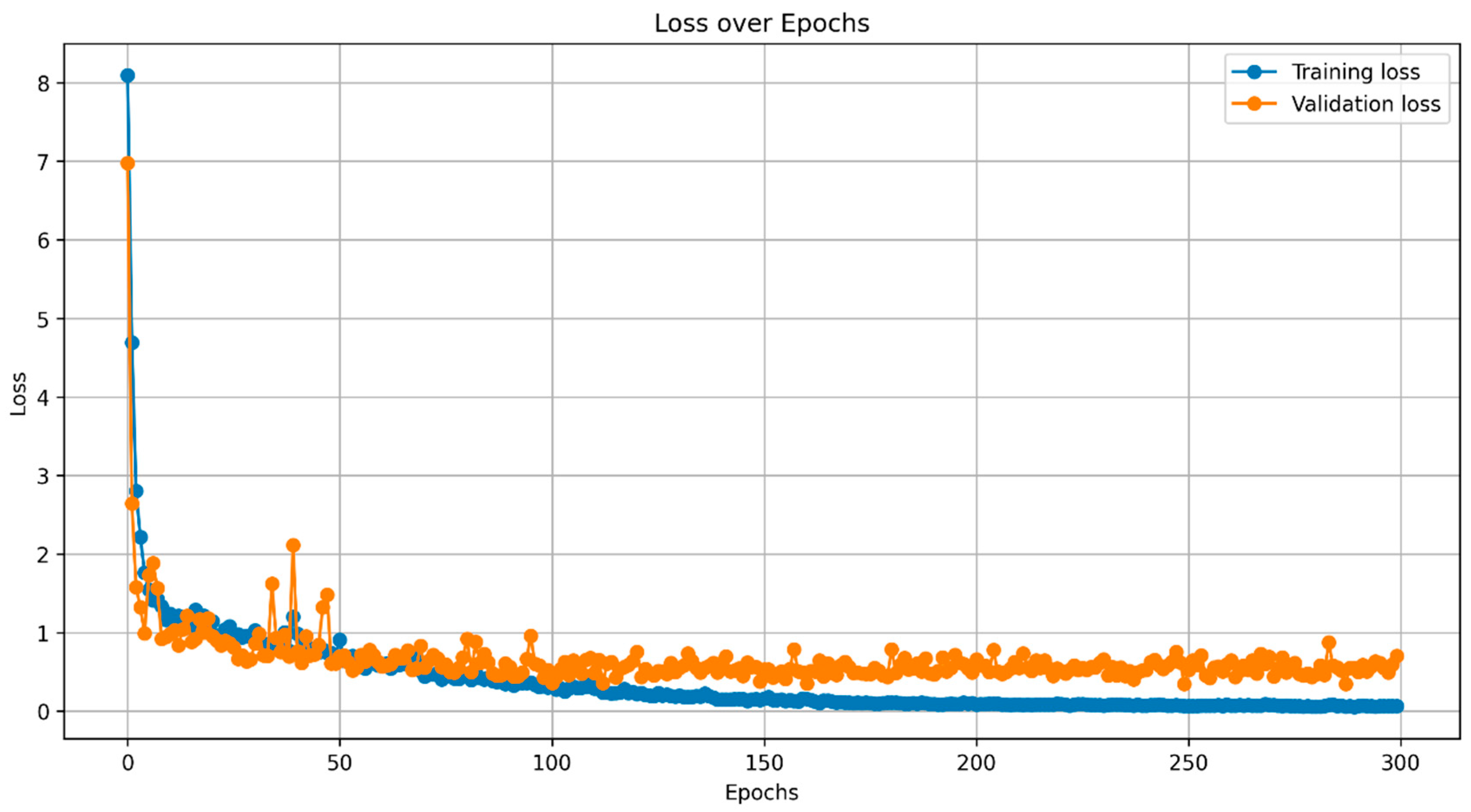

4.1. Instance Segmentation

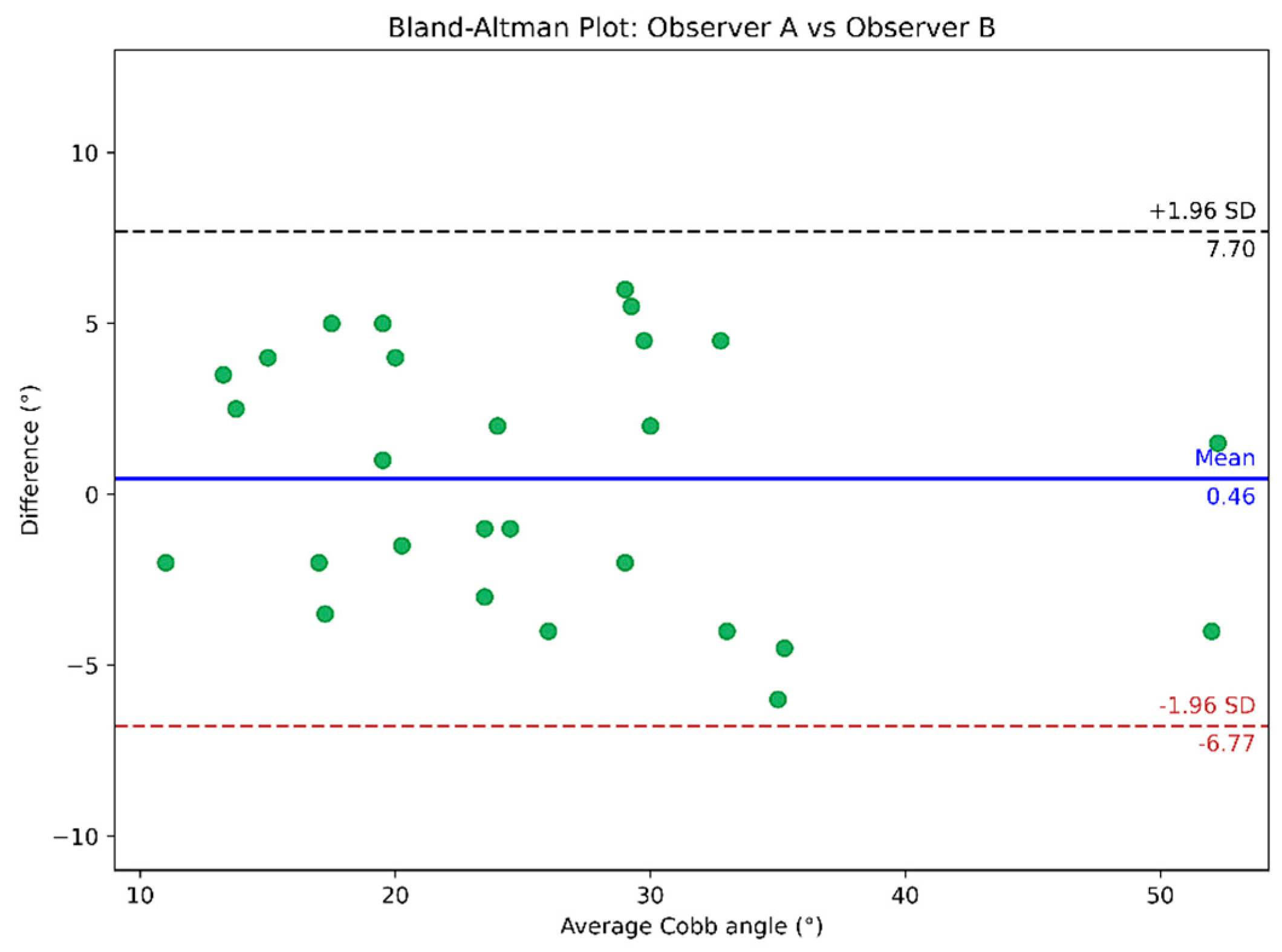

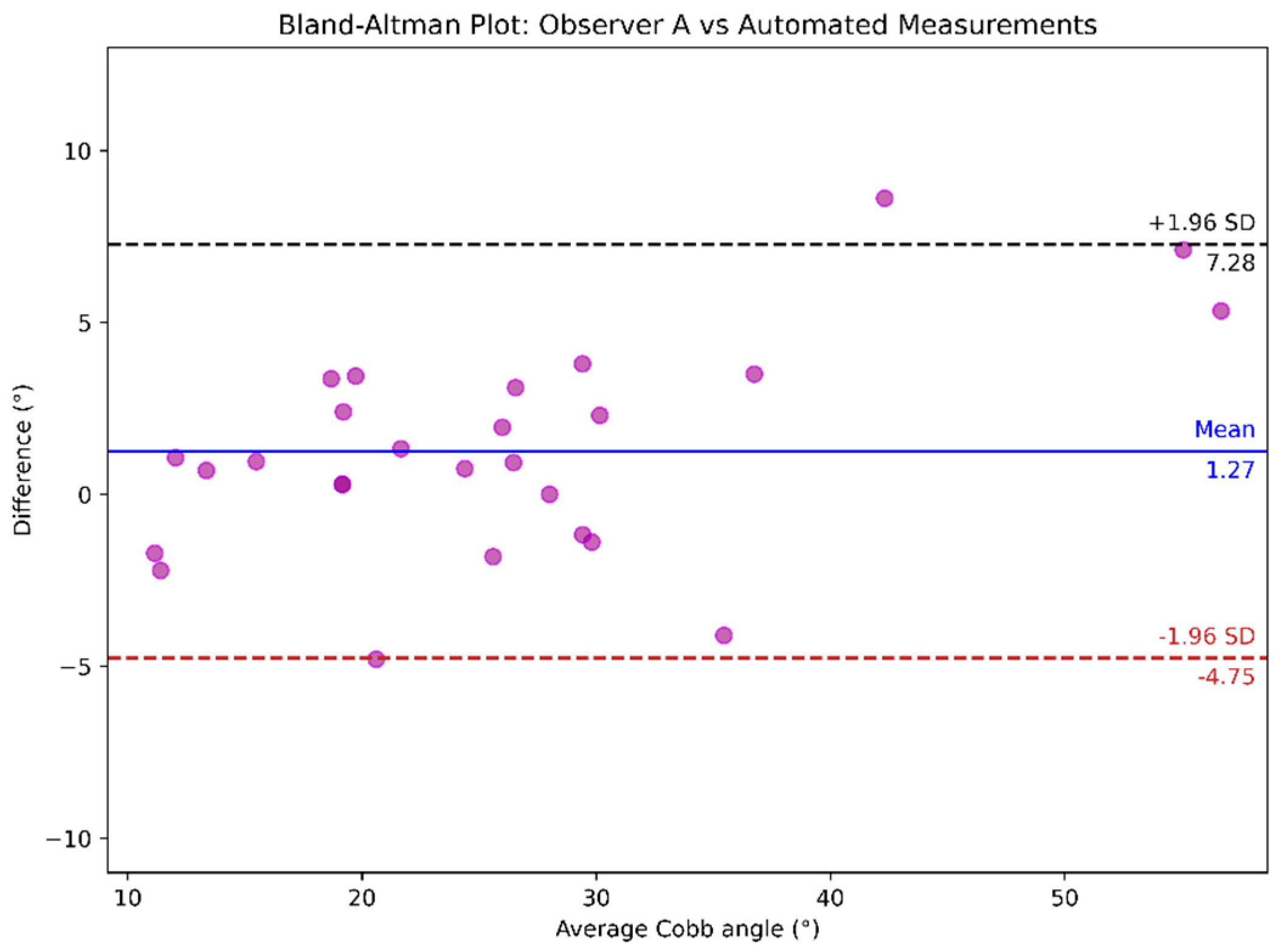

4.2. Cobb Angle Measurement

| Cobb angle measurements | Mean ± Standard deviation (range) |

|---|---|

| Manual measurement by observer A | 25.43° ± 10.85° (range 11.50-54.00°) |

| Manual measurement by observer B | 25.89° ± 10.00° (range 10.00-53.00°) |

| Measured by the automated method | 26.69° ± 12.50° (range 10.29-59.34°) |

| Analysis | ICC (95% CI) | MAD ± SD | MAE ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observer A vs. observer B | 0.939 (0.868, 0.971) | 3.31º ± 1.56º | 3.31° ± 1.53° |

| Observer A vs. automated | 0.961 (0.926, 0.984) | 2.54º ± 2.10º | 2.54° ± 2.06° |

| Observer B vs. automated | 0.895 (0.780, 0.950) | 4.07º ± 3.29º | 4.07° ± 3.22° |

| Overall: Observer A & B vs. automated | 0.928 (0.853, 0.967) | 3.31º ± 2.69º | 2.96° ± 2.60° |

5. Discussion and Scope

6. Conclusion

References

- ‘Scoliosis | Scoliosis Research Society’. Accessed: Sep. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.srs.org/Patients/Conditions/Scoliosis.

- M.-H. Horng, C.-P. Kuok, M.-J. Fu, C.-J. Lin, and Y.-N. Sun, ‘Cobb Angle Measurement of Spine from X-Ray Images Using Convolutional Neural Network’, Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, vol. 2019, no. 1, p. 6357171, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Li et al., ‘Deep learning automates Cobb angle measurement compared with multi-expert observers’, arXiv.org. Accessed: Oct. 06, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.12115v1.

- A. Thalengala, S. N. Bhat, and H. Anitha, ‘Computerized image understanding system for reliable estimation of spinal curvature in idiopathic scoliosis’, Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 7144, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Han et al., ‘Application of machine learning standardized integral area algorithm in measuring the scoliosis’, Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 19255, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Wiliński, A. Piekutin, K. Dmowska, W. Zawieja, and P. Janusz, ‘Which Method of the Radiologic Measurements of the Angle of Curvature in Idiopathic Scoliosis is the Most Reliable for an Inexperienced Researcher?’, Indian J Orthop, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 140–147, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- ‘Vertebral column | Anatomy & Function | Britannica’. Accessed: Feb. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.britannica.com/science/vertebral-column.

- B. Khanal, L. Dahal, P. Adhikari, and B. Khanal, ‘Automatic Cobb Angle Detection Using Vertebra Detector and Vertebra Corners Regression’, in Computational Methods and Clinical Applications for Spine Imaging, Y. Cai, L. Wang, M. Audette, G. Zheng, and S. Li, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 81–87. [CrossRef]

- X. Fu, G. Yang, K. Zhang, N. Xu, and J. Wu, ‘An automated estimator for Cobb angle measurement using multi-task networks’, Neural Comput & Applic, vol. 33, no. 10, pp. 4755–4761, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang et al., ‘The Comparison of Convolutional Neural Networks and the Manual Measurement of Cobb Angle in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis’, Global Spine Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 159–168, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Caesarendra, W. Rahmaniar, J. Mathew, and A. Thien, ‘Automated Cobb Angle Measurement for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Using Convolutional Neural Network’, Diagnostics, vol. 12, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C.-S. E. Chui et al., ‘Deep Learning-Based Prediction Model for the Cobb Angle in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Patients’, Diagnostics (Basel), vol. 14, no. 12, p. 1263, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ‘Deep learning automates Cobb angle measurement compared with multi-expert observers’. Accessed: Jun. 25, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/html/2403.12115v1.

- M. Gstoettner, K. Sekyra, N. Walochnik, P. Winter, R. Wachter, and C. M. Bach, ‘Inter- and intraobserver reliability assessment of the Cobb angle: manual versus digital measurement tools’, Eur Spine J, vol. 16, no. 10, pp. 1587–1592, Oct. 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. Anitha, A. K. Karunakar, and K. V. N. Dinesh, ‘Automatic extraction of vertebral endplates from scoliotic radiographs using customized filter’, Biomed. Eng. Lett., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 158–165, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Kundu, P. Lenka, R. Kumar, and A. Chakrabarti, ‘Cobb Angle Quantification for Scoliosis Using Image Processing Techniques’.

- K. He, G. Gkioxari, P. Dollár, and R. Girshick, ‘Mask R-CNN’, Jan. 24, 2018, arXiv: arXiv:1703.06870. [CrossRef]

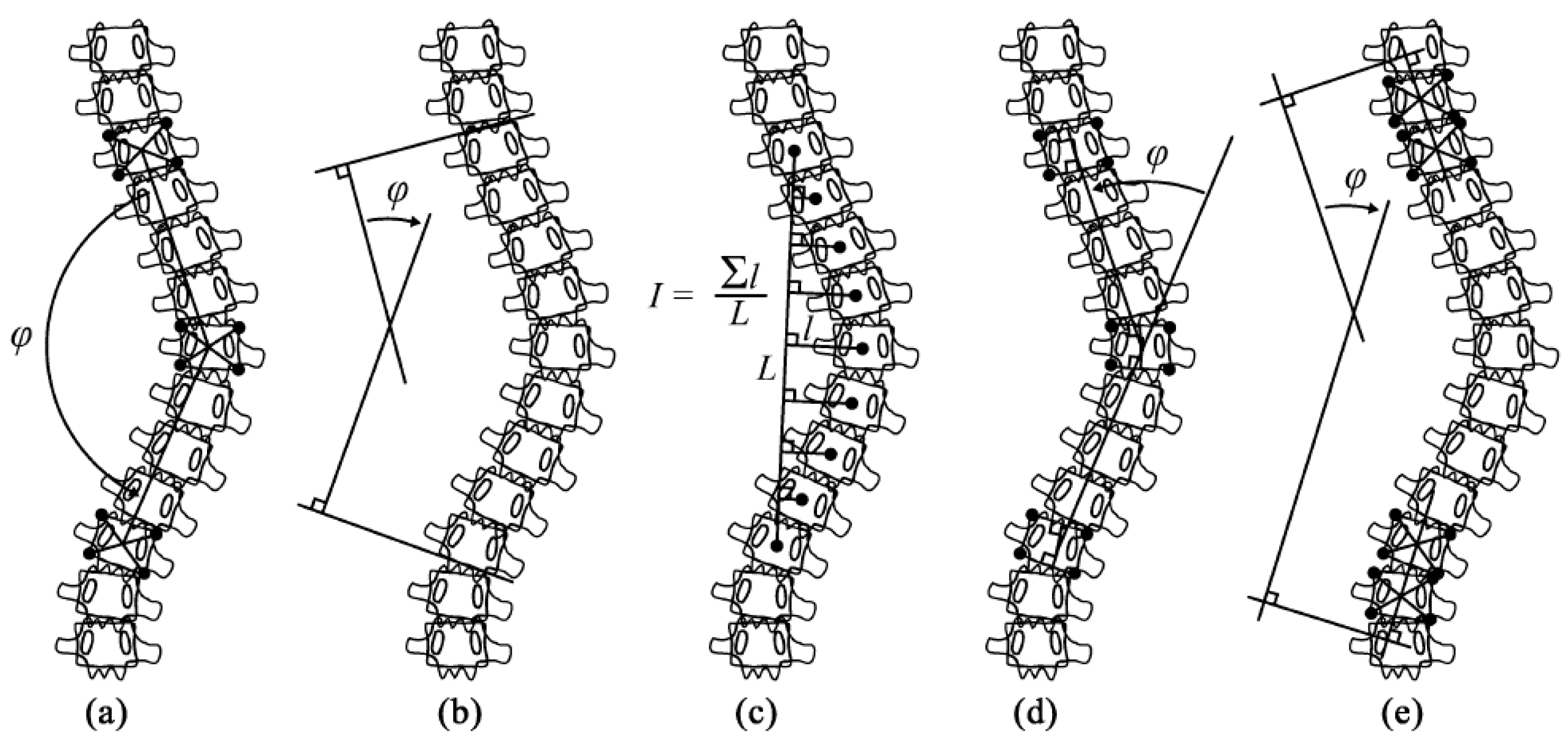

- T. Vrtovec, F. Pernuš, and B. Likar, ‘A review of methods for quantitative evaluation of spinal curvature’, Eur Spine J, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 593–607, May 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Jin, S. Wang, G. Yang, E. Li, and Z. Liang, ‘A Review of the Methods on Cobb Angle Measurements for Spinal Curvature’, Sensors, vol. 22, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Gstoettner, K. Sekyra, N. Walochnik, P. Winter, R. Wachter, and C. M. Bach, ‘Inter- and intraobserver reliability assessment of the Cobb angle: manual versus digital measurement tools’, Eur Spine J, vol. 16, no. 10, pp. 1587–1592, Oct. 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. Sun, X. Zhen, C. Bailey, P. Rasoulinejad, Y. Yin, and S. Li, Direct Estimation of Spinal Cobb Angles by Structured Multi-Output Regression, vol. 10265. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Wu, C. Bailey, P. Rasoulinejad, and S. Li, ‘Automatic Landmark Estimation for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Assessment Using BoostNet’, in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention − MICCAI 2017, M. Descoteaux, L. Maier-Hein, A. Franz, P. Jannin, D. L. Collins, and S. Duchesne, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 127–135. [CrossRef]

- H. Wu, C. Bailey, P. Rasoulinejad, and S. Li, ‘Automated comprehensive Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis assessment using MVC-Net’, Medical Image Analysis, vol. 48, pp. 1–11, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Chen, Q. Xu, L. Wang, S. Leung, J. Chung, and S. Li, ‘An Automated and Accurate Spine Curve Analysis System’, IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 124596–124605, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang et al., ‘Development and validation of deep learning algorithms for scoliosis screening using back images’, Commun Biol, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–8, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Yi, P. Wu, Q. Huang, H. Qu, and D. N. Metaxas, ‘Vertebra-Focused Landmark Detection for Scoliosis Assessment’, in 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Apr. 2020, pp. 736–740. [CrossRef]

- J. Cerqueiro, A. Comesaña-Campos, M. Casal-Guisande, and J. Bouza-Rodríguez, A proposal for using active contour parametrical models in Cobb angle determination. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, Y. Xing, Z. Zhao, X. Meng, G. Xu, and Y. Hai, ‘Comparison of manual versus automated measurement of Cobb angle in idiopathic scoliosis based on a deep learning keypoint detection technology’, Eur Spine J, vol. 31, no. 8, pp. 1969–1978, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Maeda, T. Nagura, M. Nakamura, and K. Watanabe, ‘Automatic measurement of the Cobb angle for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis using convolutional neural network’, Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 14576, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Qiu, J. Yang, and J. Wang, ‘MMA-Net: Multiple Morphology-Aware Network for Automated Cobb Angle Measurement’, Sep. 24, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2309.13817. [CrossRef]

- A. Suri et al., ‘Conquering the Cobb Angle: A Deep Learning Algorithm for Automated, Hardware-Invariant Measurement of Cobb Angle on Radiographs in Patients with Scoliosis’, Radiology: Artificial Intelligence, vol. 5, no. 4, p. e220158, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Hoblidar and G. Prabhu, ‘Automatic Quantification of Spinal Curvature in Scoliotic Radiograph using Image Processing’, Journal of medical systems, vol. 36, pp. 1943–51, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, and T. Brox, ‘U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation’, May 18, 2015, arXiv: arXiv:1505.04597. [CrossRef]

- A. O. Vuola, S. U. Akram, and J. Kannala, ‘Mask-RCNN and U-net Ensembled for Nuclei Segmentation’, Jan. 29, 2019, arXiv: arXiv:1901.10170. [CrossRef]

- R. H. Alharbi, M. B. Alshaye, M. M. Alkanhal, N. M. Alharbi, M. A. Alzahrani, and O. A. Alrehaili, ‘Deep Learning Based Algorithm For Automatic Scoliosis Angle Measurement’, in 2020 3rd International Conference on Computer Applications & Information Security (ICCAIS), Mar. 2020, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, L. Shi, J. C.-Y. Cheng, W. C.-W. Chu, and S. C.-H. Yu, ‘LPAQR-Net: Efficient Vertebra Segmentation From Biplanar Whole-Spine Radiographs’, IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 2710–2721, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, J. Zhang, H. Li, X. Gu, Z. Li, and S. Zhang, ‘Automatic Cobb angle measurement method based on vertebra segmentation by deep learning’, Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing, vol. 60, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. C. WONG, M. Z. REFORMAT, E. C. PARENT, K. P. STAMPE, S. C. SOUTHON HRYNIUK, and E. H. LOU, ‘Validation of an artificial intelligence-based method to automate Cobb angle measurement on spinal radiographs of children with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis’, Eur J Phys Rehabil Med, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 535–542, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Johari, ‘Automated Cobb angle measurement in scoliosis radiographs: A deep learning approach for screening - Annals Singapore’. Accessed: Jan. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://annals.edu.sg/automated-cobb-angle-measurement-in-scoliosis-radiographs-a-deep-learning-approach-for-screening/.

- Z. Liang et al., ‘From 2D to 3D: Automatic measurement of the Cobb angle in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with the weight-bearing 3D imaging’, The Spine Journal, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Rahmaniar, K. Suzuki, and T.-L. Lin, ‘Auto-CA: Automated Cobb Angle Measurement Based on Vertebrae Detection for Assessment of Spinal Curvature Deformity’, IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 640–649, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. K. I. Kassab, I. G. Kamyshanskaya, and A. A. Pershin, ‘Automatic scoliosis angle measurement using deep learning methods, how far we are from clinical application: A narrative review’.

- M. Maharasi, N. Senthilnayaki, and K. Snehaprabha, ‘Vertebrae Landmark Detection and Scoliosis Assessment Using Deep Learning’, 2024 International Conference on Communication, Computing and Internet of Things (IC3IoT), pp. 1–6, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Pan et al., ‘Evaluation of a computer-aided method for measuring the Cobb angle on chest X-rays’, Eur Spine J, vol. 28, no. 12, pp. 3035–3043, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Z. Low et al., ‘Automated Cobb angle measurement in scoliosis radiographs: A deep learning approach for screening’, Ann Acad Med Singap, vol. 53, no. 10, pp. 635–637, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ‘AASCE | AASCE - MICCAI 2019 Challenge: Accurate Automated Spinal Curvature Estimation’. Accessed: Feb. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://aasce19.github.io/.

- M.-H. Horng, C.-P. Kuok, M.-J. Fu, C.-J. Lin, and Y.-N. Sun, ‘Cobb Angle Measurement of Spine from X-Ray Images Using Convolutional Neural Network’, Comput Math Methods Med, vol. 2019, p. 6357171, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Singla, AarohiSingla/Mask-R-CNN-using-Tensorflow2. (Dec. 20, 2024). Jupyter Notebook. Accessed: Jan. 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/AarohiSingla/Mask-R-CNN-using-Tensorflow2.

- A. Gad, ahmedfgad/Mask-RCNN-TF2. (Feb. 04, 2025). Python. Accessed: Feb. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/ahmedfgad/Mask-RCNN-TF2.

| Threshold | mIoU | mDSC | mAP | Mean precision |

Mean recall |

Over-seg | Under-seg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.85 (epoch 146) | 0.8012 | 0.8878 | 0.645 | 0.9145 | 0.8643 | 0.0855 | 0.1357 |

| 0.85 (epoch 155) | 0.7980 | 0.8857 | 0.655 | 0.9150 | 0.8599 | 0.0850 | 0.1401 |

| 0.85 (epoch 287) | 0.7818 | 0.8750 | 0.625 | 0.9313 | 0.8268 | 0.0687 | 0.1732 |

| Analysis | ICC (95% CI) | MAD ± SD | MAE ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observer A vs. Observer B | 0.939 (0.868, 0.971) | 3.31º ± 1.56º | 3.31° ± 1.53° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).