1. Introduction

The promise shown by quantum information as a means for computation is immense. This is primarily because of the characteristic of a quantum system. The size and complexity of the wave function, a mathematical function which represents quantum state can grow exponentially large as the number of particles in the quantum system increases. This exponential size can help us represent complex problems that a classical computer cannot. [1]Feynman was perhaps the first person to realize how much significance information processing in a quantum computer might hold in the future. He theorized how quantum laws can be simulated and understood at a deeper level in a quantum computer. [2]Any quantum algorithms of future would require reliable, robust and long-term storage solutions of quantum states, to represent information in order to process and have any significant impact on the computational landscape. It is however very difficult in practice to maintain stable quantum state over a long period of time due to quantum decoherence, pertaining to the environmental interference with a quantum system. It has been found that quantum states of photons of light are more reliable for storage purposes than any other quantum states, because of their relatively better isolation from environment and ease of manipulation for storage of information [

3,

4]. In this paper, we put forward a novel approach of storing and retrieving quantum information by using a quesi-particle polariton state, a mixed atomic dipole and photonic state generated by strong atom-light interaction in an electromagnetically induced transparent (EIT) ultra-cold atomic lattice ensemble.

Initial attempts at storing photonic states were very challenging and limited particularly because of the fact that any quantum state suffers from spontaneous decay from its initial state. The decoherence in turn make it challenging to use any such quantum state to encode information. One of the first attempts to use quantum states to store information was done storing states of atoms in a Zeeman ground state by coupling atomic levels with a cavity QED field and subsequent adiabatic transfer of the information of the atomic states to the states of cavity QED photons. [

5] However, the cavity damping of the QED field remained a practical issue preventing the realization of a robust quantum memory architecture. The cavity damping and population loss from the atomic levels storing a quantum state was shown to be bypassed by using a three level atomic system and two coherent lasers coupling an intermediate state with lowest lifetime to an initial atomic state, in which the system is initially prepared and a final atomic state, to which the system evolves at the end of the process, storing the quantum state of the population, which was initially prepared, both states having a much longer lifetime than the intermediate state. This process was leading the populations from the initial state to the intermediate state, which then get transferred to the final state by a Stokes pulse, bypassing the spontaneous emission from the intermediate state. [

6] The three level scheme to store quantum information as quantum states of an atom in an energy state was further extended to the collective atomic ensemble by the phenomenon of electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT). In this process, a quesi-quantum excitation field, composed of Raman-like atomic spin coherence states and photonic states was generated inside an atomic medium, by coupling a weaker “probe” and a stronger “control” laser between an initial ground state, at which the system is maintained initially and a final stable ground state, to which the system evolves eventually to an excited state for coherent Raman excitation of the populations. The coupling between the stable state and the excited state facilitated by the control laser splits the excited state due to which the probe laser does not get absorbed by the atomic medium, instead the photonic states of the laser get transferred to the collective atomic excitation of the medium, culminating in the stable state creating a ‘dark state’ The dark state is a superposition state of the initial state and the final stable state and therefore remain from the spontaneous emission. When such an atomic ensemble couples to a strong control cavity QED field, and reaches the collective dark state, the quantum state of the probe pulse gets stored in the atomic spin excitation of the final stable ground state, creating a superposition of the photonic and the atomic spin excitation state, known as ‘dark state polariton’. [

7] The coherence of the spin atomic excitation was shown enhanced by manipulation of the dispersion of the atomic medium by application of two counter-direction control lasers coupling the final stable state with the excited state. By the effect of these lasers, a standing wave is generated in the atomic medium, which creates a band gap in the band structure of the atomic medium, facilitating trapping of the probe pulse inside the medium as a standing wave probe. [

8] The effect of the standing wave probe inside the medium showed a greater coherence time for the quantum state stored inside it and hence provided a window of possibility to have more stable and robust quantum memories [

9,

10,

11]. It was theoretically shown how the counterpropagating control lasers eliminate total dispersion loss of the quantum state, stored as a perfectly standing wave probe field inside an EIT medium. [

12]

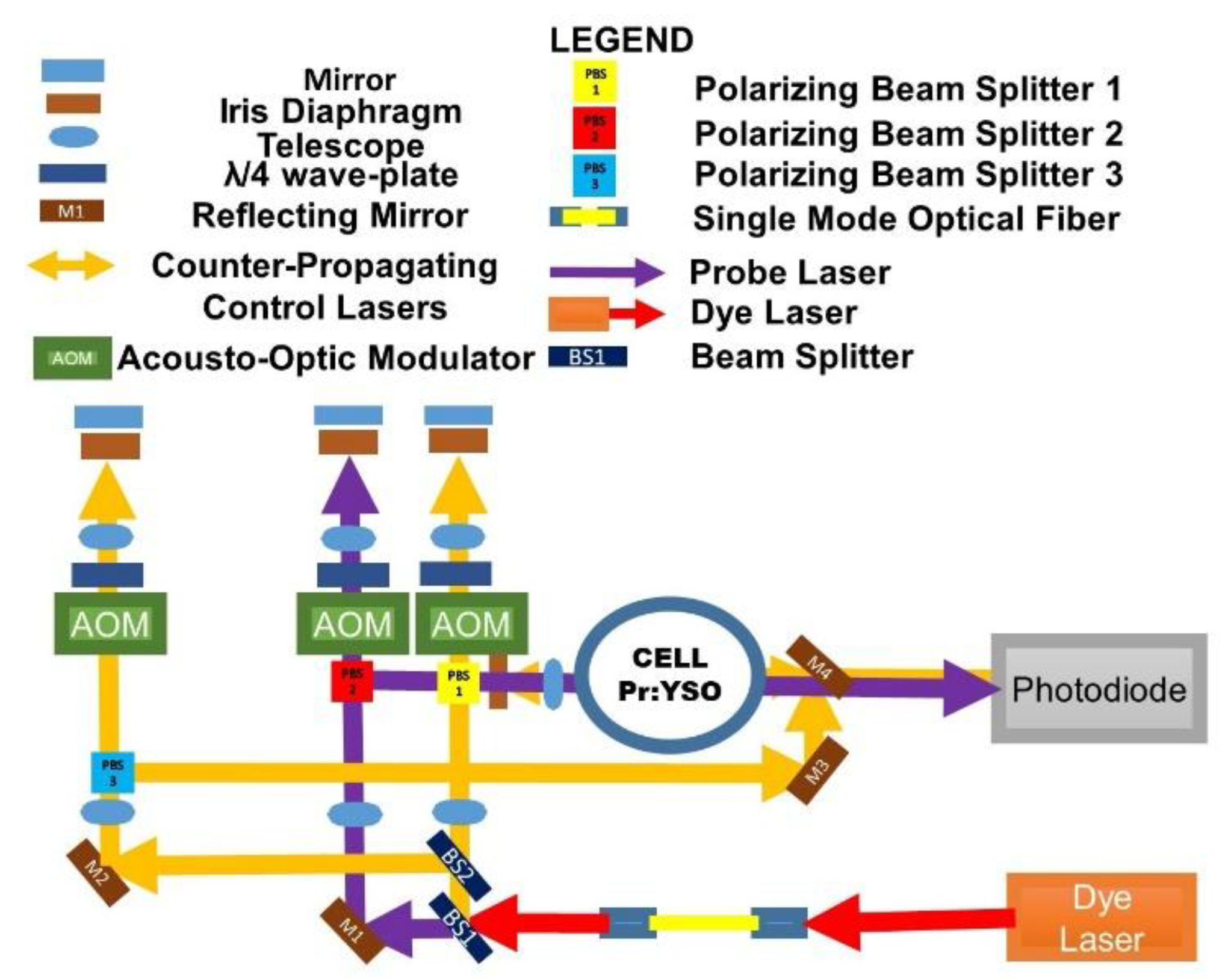

The trapped standing wave probe field can be a potent quantum memory in the future quantum computers. The retrieval of information as photonic state of the probe, however, requires one of the counter-directional lasers to be shut off for the probe to be retrieved by a photon detector in that particular direction, desired. It can be inferred that the elimination of the dispersion loss will not be present while the retrieval of the stored standing wave pulse as a travelling wave pulse is in progress inside the atomic medium. So, in fact the retrieved information about the quantum state will still not be free from environmental interference and will suffer incoherent losses. Therefore, the retrieval and propagation of the probe pulse inside the atomic medium as a polariton excitation, also demands shielding from the eminent diffusion losses, due to the diffusive motion of the atoms. It has already been shown that counter-directional control laser driven EIT system in the frequency-up conversion regime provide much better transparency windows to travelling probe pulse inside the medium, than travelling wave control laser field. In this paper, we put forward an adiabatic technique to address the issue by extending the shielding effect of the standing wave control field from the dispersion losses in the standing wave probe inside an EIT medium to the travelling probe as well and compare their effects with the travelling wave control field case. We present with an adiabatic Raman population transfer technique of EIT, by incorporating the effects of a standing wave control laser QED field on a travelling wave probe in an ensemble, composed of stationary atoms. We derive the propagation equation for the travelling probe field inside the EIT medium and show how the Fourier modes of the standing wave control laser field eliminate the diffusion loss in the travelling probe as well. We also propose an experiment to show how the storage of travelling probe pulse can be realized in a stationary atomic medium such as a rare-earth doped crystal lattice of Pr3+: Y2SiO5 by creation of an EIT system, using a Dye laser to couple the hyperfine levels 3H4 ↔1D2 of the crystal, having a very long lifetime.

2. Methodology

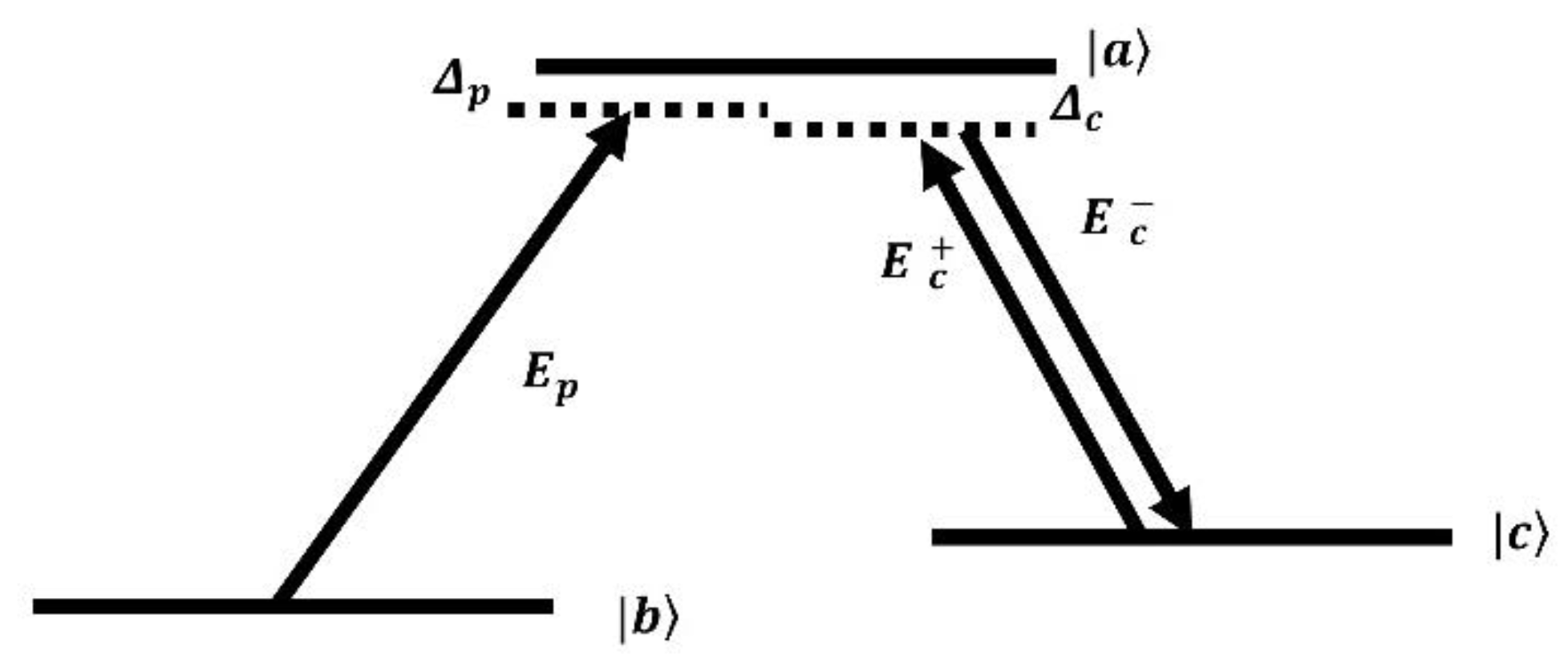

Our system is implemented using a solid crystalline atomic medium, structured as an ensemble lattice of atoms. We employ a lambda-level Electromagnetically Induced Transparency (EIT) scheme, wherein two hyperfine components of the ground-state energy levels are connected to an excited atomic state. Specifically, two strong counterpropagating coupling lasers, referred to as control lasers, with Rabi frequency

, couple the final stable ground-state component

to the excited state ∣a⟩. Concurrently, a weak coupling laser, referred to as the probe laser, links the initial ground-state component ∣b⟩ with the same excited state ∣a⟩. Notably, the direct transition between the two ground-state components ∣b⟩ and ∣c⟩ is forbidden. The system leverages quantum interference effects: the destructive interference of transition probability amplitudes for the transitions ∣b⟩→∣a⟩ and ∣c⟩→∣a⟩. This interference enables the probe laser pulse to propagate through the medium without significant absorption. Furthermore, the wave vectors of the probe and control lasers are configured to satisfy the velocity-tuned multiphoton processes, ensuring coherent coupling and efficient EIT dynamics. This configuration is crucial for achieving the desired transparency and enhanced control over light-matter interactions within the medium.

Figure 1.

A Lambda Level EIT System, where counter-propagating control lasers with amplitude and a probe laser with amplitude and are the detunings.

Figure 1.

A Lambda Level EIT System, where counter-propagating control lasers with amplitude and a probe laser with amplitude and are the detunings.

Here, ‘q’ represents the number of photons in the control laser pulse, while v denotes the atomic velocity. The detunings of the probe and control laser pulses are denoted by Δ

p and Δ

c, respectively. We consider a system comprising N lambda-level atoms interacting with two distinct laser fields: a standing-wave control laser field with amplitude E

c± and wave vector ±k

c, and a traveling-wave probe field with amplitude E

p and wave vector k

p. The atomic states are described using density matrix elements

, while

denotes the dipole operators. For simplicity, we assume the atomic velocity

v to be approximately zero, consistent with the ensemble configuration of our atomic lattice system. However, we acknowledge the presence of atomic diffusion in real lattice systems, where

v cannot be strictly zero. To further simplify the model, we consider near-resonant conditions for both the probe and control laser fields, such that Δ

p ≈ 0 and Δ

c ≈ 0. Under these assumptions, the Hamiltonian describing the interaction of the N-atom lambda-level system is expressed as follows:

This formulation provides a foundation for analysing the coherent dynamics and light-matter interactions within the atomic lattice under the specified EIT scheme. In the presence of laser-atom interaction, we assume that the time evolution of the atomic operators is slow compared to the timescale of the electromagnetic fields. This allows us to define slowly varying atomic elements for the analysis. Specifically, we define

,

and

and

are unit vectors along the propagation directions of the control and probe lasers, respectively. Additionally, the slowly varying atomic density matrix elements are denoted as

, in contrast to the standard atomic density matrix elements

. Substituting the slowly varying atomic elements into Heisenberg’s equation of motion and applying the rotating wave approximation (RWA), which eliminates rapidly varying terms, we derive the Heisenberg-Langevin equations of motion. Here,

represents the incoherent decay rates of the electron population in specific states.

Given that the probe pulse is significantly weaker than the standing-wave control laser fields, the equations can be solved using a perturbative approach, as outlined in [13]. In this method, the atomic density matrix elements are expanded in powers of ϵ, defined as the ratio of the amplitudes of the probe and control pulses. Under the initial condition that the majority of atoms are in the ground state

) , the atomic density matrix elements are obtained as follows:

Here,

. where Ω

c± are the control field components. The equations of motion derived in this framework, such as (3a), (3b), and (3c), evolve very slowly. To account for this, we define the characteristic timescale of laser operation as

. The slowly varying atomic operator

is expanded in powers of

. Expanding up to zeroth order in Equation (3c) and substituting

into Equation (3a), we derive the following:

By inserting the value of

in Equation 4(a), we get:

Rewriting these equations using the definitions

, we find the spin excitation of the probe where

is the total Rabi frequency of the control field, and

represents a constant phase.

We must also know the wave-equation of the electromagnetic field in an atomic medium. It has been shown that the wave equation can be written as: [13]

Having derived the atomic spin excitation operator for our atomic ensemble, we are now in a position to review in detail, how theses spin excitation helps quantum state to be stored as quantum information. In this study, we consider a system where all atoms are initially prepared in the ground state ∣b,0⟩. Under this condition, the interaction couples the system exclusively to the totally symmetric Dicke-like states. Specifically, if the field is prepared in an initial state containing at most one photon, the relevant eigenstates of the bare system are as follows: The total ground state ∣b,0⟩, which remains unaffected by the interaction. The ground state with a single photon in the field, ∣b,1⟩. The singly excited atomic states ∣a,0⟩ and ∣c,0⟩. These states form the basis of the interaction dynamics, with the system transitioning among them under the influence of the laser fields. The exclusion of other states simplifies the analysis and highlights the key physical processes associated with single-photon and single-atom excitations in the system. [13]

The eigenstates of the Hamiltonian in Equation (1) can be found as

can be identified as the required dark state, which we already discussed in the Introduction. For the ensemble the dark state for a single photonic excitation can be given as:

. Here,

is defined as the mixing angle. For n such excitations the expression can be given as:[

13]

By adiabatic rotation of the mixing angle

, from 0 to π/2 leads to reversible transfer of the photonic number states to the collective atomic spin excitations stored at the final stable state

[

13]

The operation generates a tensor product mix of the photonic states and the collective atomic spin excitations as [

13]

The formulation presented above is based on the time-independent version of the Hamiltonian at (1), however to derive the propagation equations of the probe inside the atomic ensemble with the preserved quantum states in the atomic excitation, we need to work with the time dependent dynamics of the above system, featuring a time dependent control field. Consequently, the atomic excitation derived in the Equations 4(a)-4(c) will also have to be time dependent. Please note we need to solve the coupled equations (4(c) ) and (5) to solve the propagation problem. Physically, this means we calculate how the atomic excitation evolves as the electromagnetic field of the probe propagates inside the atomic ensemble. To perform the time dependent calculations effectively we need to arrive at a single equation, which can predict the time dependence of both the atomic operator and the electromagnetic field. To solve the problem, a quesi-particle called ‘dark state polariton’ was introduced in [

13]. The quantum field

is defined as the linear superposition of the bosonic field (in our case probe laser electromagnetic field

and an atomic excitation operator field

allowing the above dark state transitions.

These field operators follow bosonic commutation relations.

The dark state transition then can be written as

being the vacuum state, i.e.:

. Now we are ready to derive the propagation equations for the polariton fields. For including the atomic diffusion into the polariton picture the propagation equation for the dark polariton field need to be of second order in special coordinate. For that we expand 3 (c) up to first order in

, and then insert the value of

in 4(a), we thus get

By using the definition of the polariton field in (7) we get

The wave equation for the probe field then can be written in terms of the dark polariton field, considering constant mixing angle

as:

In a solid-state system, the atomic operators exhibit vibrations corresponding to all possible wave vectors, enabling their representation as a Fourier series. These vibrations correspond to the complete set of standing wave modes of the control field within the cavity. The interaction between the atomic spin excitation field operators and these modes gives rise to polaritons, which encode the quantum state of the probe pulse photons. Therefore, the denominator

appearing on the right-hand side of Equation (10) can similarly be expressed as a Fourier series.

Substituting the fourier expansion of the denominator

in (10) we get:

The propagation equation for the spin excitation operator is derived, by finding the correct Fourier coefficient, for which the unidirectional polariton component

have the corresponding primary Fourier mode of the spin excitation (i.e.:

. The Fourier coefficients are given as [12]:

The final propagation wave equation for the travelling probe obtained after evaluating Equation (12) further, considering a very low decoherence rate

and using the relation between the second order derivative of space and time coordinates

will be as follows

As we have chosen a stationary atomic system, only first order Fourier coefficients are of significance as they are much larger than the higher order Fourier coefficients, so we only need to find the

as we are considering the special case of

using Equation (13 a) and (13 b):

. Substituting the Fourier coefficients in Equation(14), approximating the group velocity

and evaluating we get :

The wave equation governing the polariton fields under non-adiabatic conditions is presented, incorporating a second-order derivative term on the right-hand side. This term, identified as the diffusion term, arises from pulse broadening, which leads to the loss of polariton fields stored within the material as quantum memory. The term diminishes due to the standing wave control field Rabi frequencies. The equation is solved using the Fourier transform method, yielding a solution in Fourier space after integrating both sides. Assuming an initial Gaussian probe wave, expressed as

, selecting units where

for simplicity and choosing the group velocity’s time dependence as

, where

is the characteristic switching time of the laser, the solution is subsequently transformed back to real space via an inverse Fourier transform. The resulting expression, obtained numerically, provides insight into the behavior of the polariton field under the given conditions:

The total energy density obtained after substituting

in terms of field amplitude

based on the definition (7) is:

The total energy density derived under the given conditions reveals that, for a perfect standing wave configuration

the diffusion term on the right-hand side of the wave equation vanishes entirely.

In this scenario, there is no energy loss attributable to diffusion, although losses arising from decoherence may still persist. This result highlights the significance of the standing wave configuration in minimizing diffusion-related losses in the system. This feature has been previously demonstrated for a standing wave probe pulse trapped inside an EIT cavity. Our results extend this understanding by showing that diffusion losses of a traveling probe pulse inside an EIT cavity can also be minimized by the primary modes of the standing wave control field. The application of the standing wave control field reduces the traveling probe field losses, leading to extended coherence and storage times. However, our formulation assumes that the spontaneous downward transition of atoms in the dark state is negligible compared to the atomic population at that level. In a real atomic system, the spontaneous downward transition is significant and must be considered. This transition follows an exponential decay law, and incorporating the loss due to spontaneous emission allows the energy density derived earlier to be approximately recalculated as:

4. Results

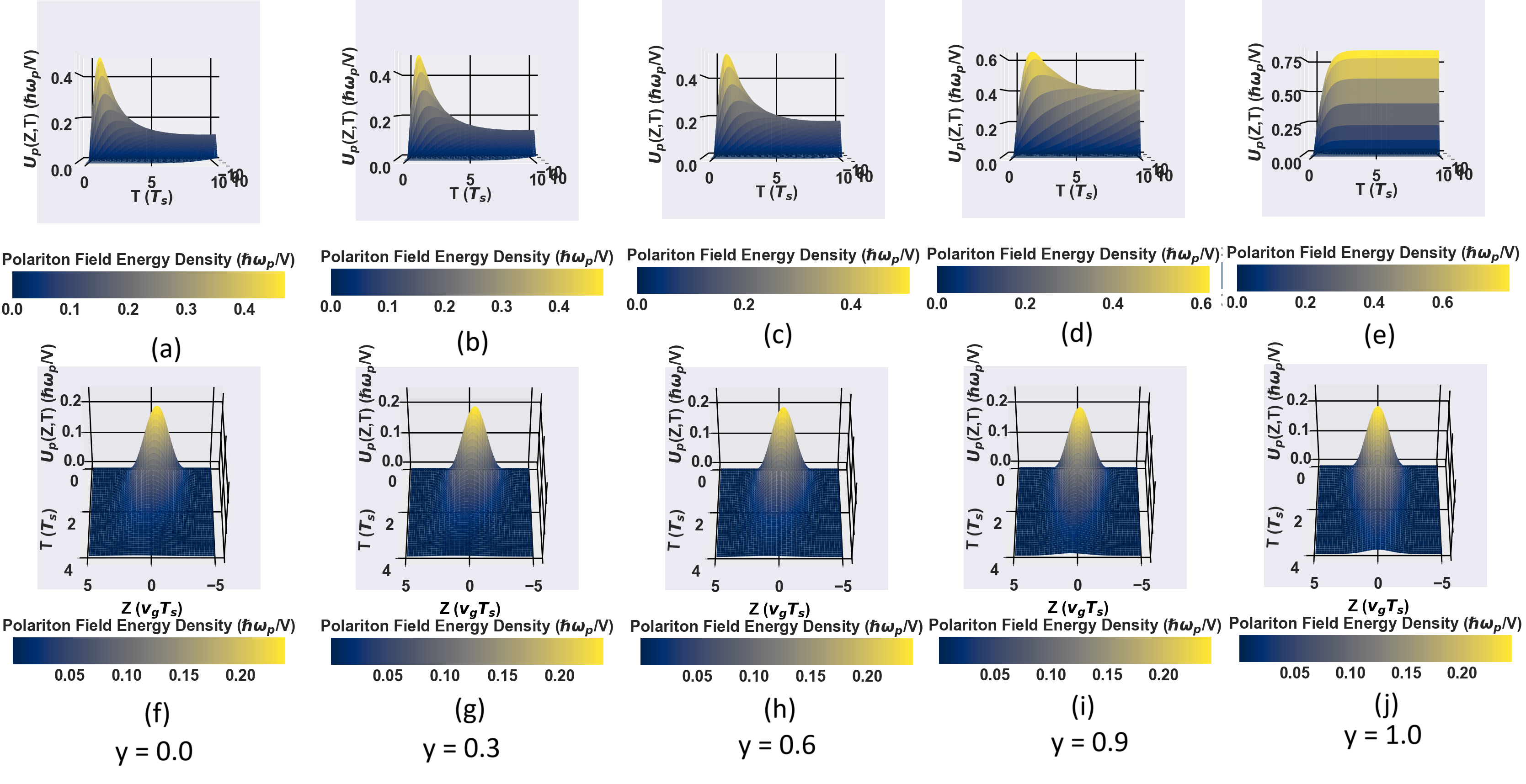

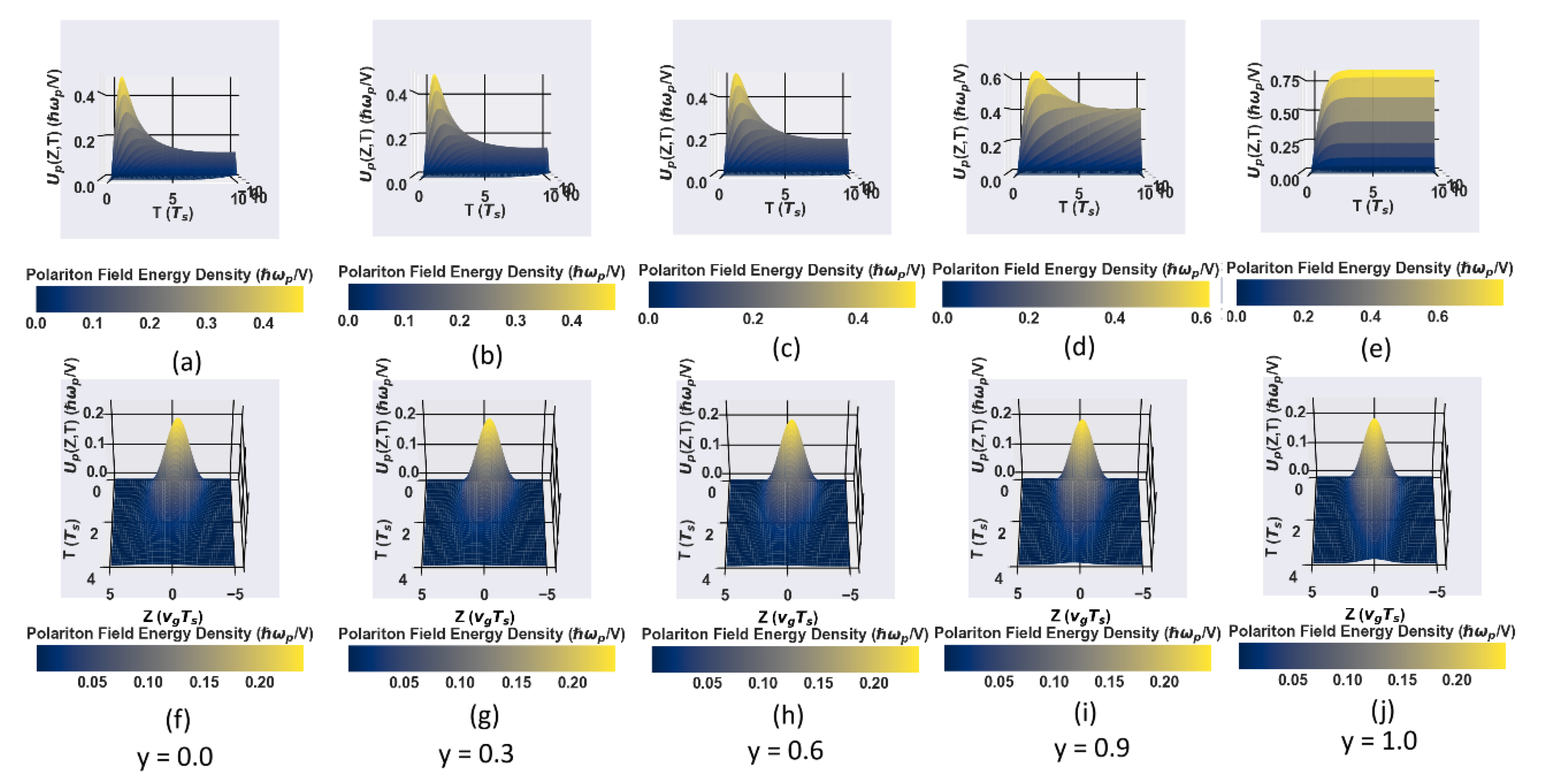

Equation (16) highlights the critical role of the Rabi frequencies of counter-propagating control lasers in shaping the traveling dark-state polariton (DSP) waveform. The counter-propagating laser pulses generate cavity modes that are inherently dependent on these Rabi frequencies, which, in turn, influence the EIT window through which the traveling probe polariton propagates. By varying the control laser fields, the Fourier modes of the control lasers can be adjusted, allowing precise manipulation of the probe pulse’s shape and duration. This tunability facilitates the manipulation of photonic quantum states within the atomic medium as polaritons, making them highly suitable for quantum memory applications that require extended coherence times. Different ratios of result in either enhanced or diminished waveforms of the probe polariton field. Notably, when counter-propagating control fields of equal intensities are applied, the polariton field stored within the crystal experiences no diffusion loss. Under these optimal conditions, the adiabatic storage of the probe pulse is limited solely by the spontaneous emission rates of the ground-level hyperfine states & , ensuring high-fidelity quantum memory storage.

Figure 3 (a)-(e) illustrates the energy decay of the polariton field under various control field configurations. In the case of a traveling wave control field (y=0.0), the polariton energy exhibits exponential decay due to diffusion losses. With counter-propagating control fields (y=0.3-0.9), the diffusion losses are significantly reduced, resulting in a slower decay of the polariton field energy and an extended coherence time for the photonic states mapped into atomic states. For a perfectly standing wave control field (y=1.0), diffusion losses are completely eliminated, and the polariton energy remains constant over time in the absence of spontaneous emission. This configuration ensures that the collective atomic excitations remain undisturbed, theoretically enabling indefinite storage. However, in real atomic systems, the finite spontaneous emission rate imposes a practical limitation on the storage duration.

Figure 3 (f)-(j) illustrates the effect of the standing wave control on the pulse broadening of the probe pulse inside the medium. As we approach the perfectly standing probe pulse condition, pulse broadening decreases and gets eliminated completely when perfectly standing wave control field is obtained.

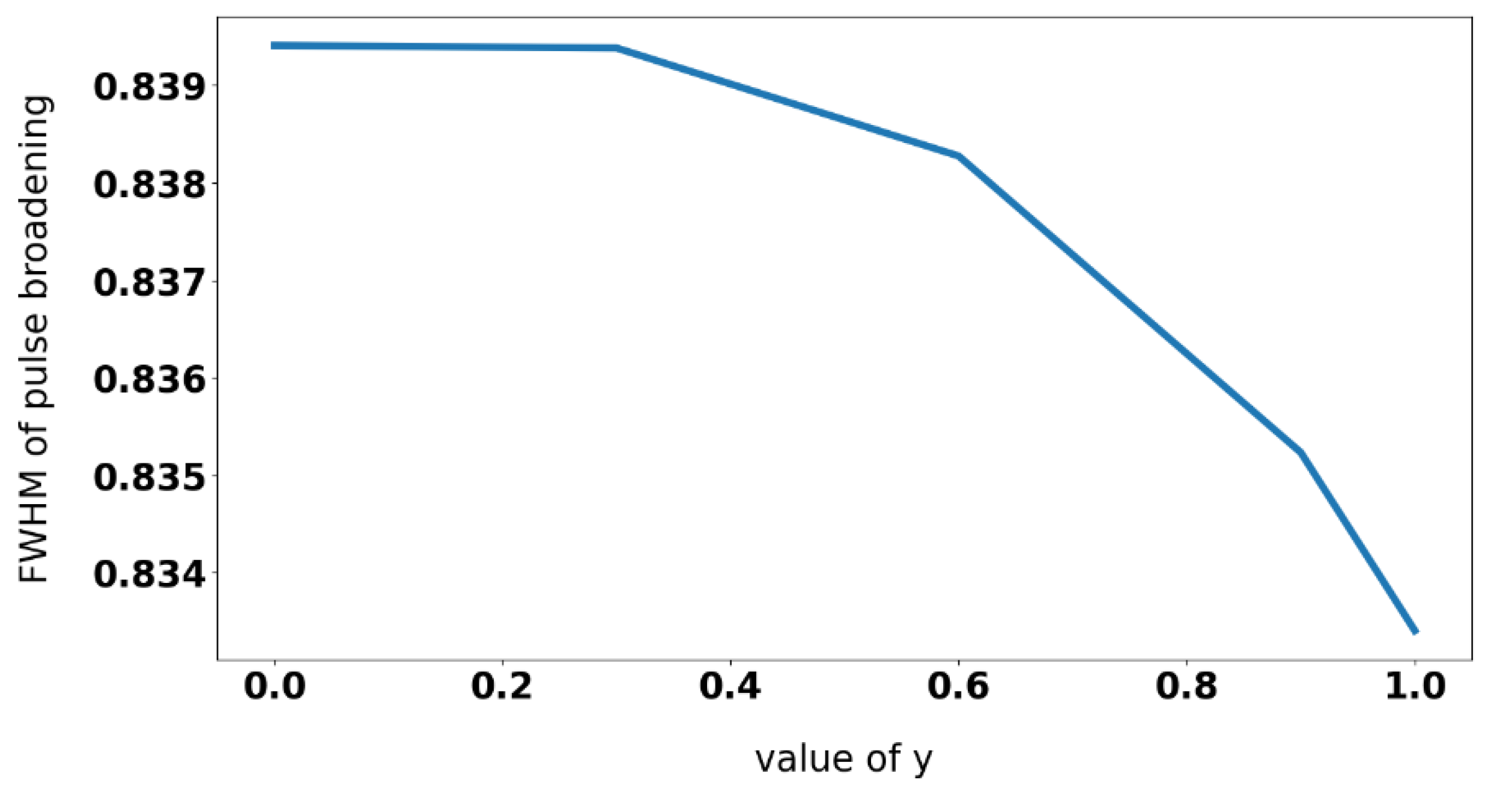

Figure 4 illustrates the variation in pulse broadening of the polariton with the Rabi frequency ratio,

. In the traveling wave control field configuration (y=0), the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of the polariton energy density distribution is the largest, indicating significant pulse broadening caused by diffusion-induced expansion. In contrast, for counter-propagating control fields (y=0.3-0.9), the FWHM decreases as diffusion losses are reduced, resulting in a narrower pulse width. The perfectly standing wave control field case (y=1) demonstrates the smallest FWHM, reflecting minimal pulse broadening due to the complete elimination of diffusion loss.

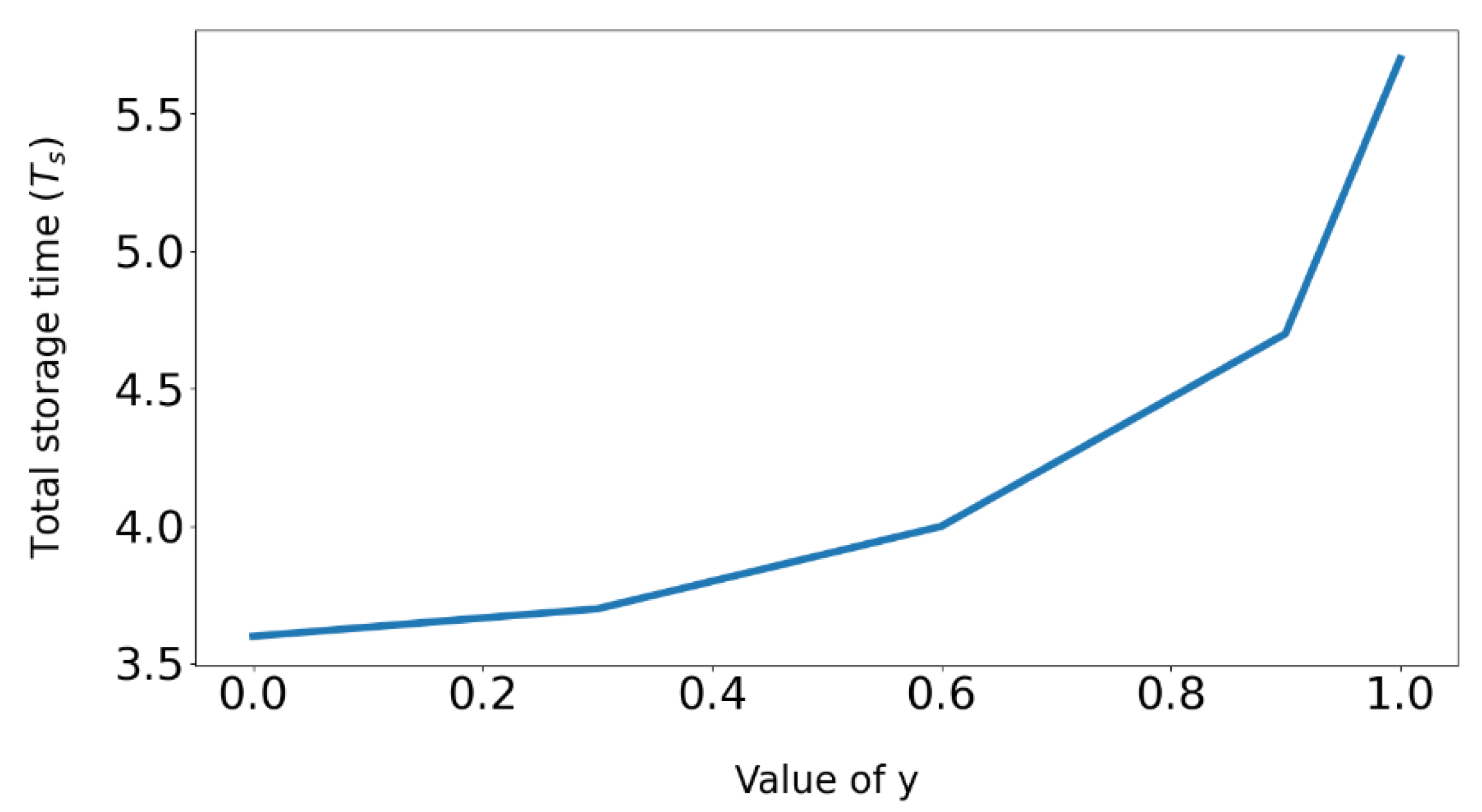

Figure 5 illustrates the perfectly standing wave control field

the storage duration of the probe pulse is significantly extended compared to the traveling wave case

, based on the time taken for the energy density

to fall below 0.01

, the storage time increases from approximately T ~ 3.6 T

s for the traveling wave case to T ~ 5.7 T

s for the standing wave case. Here, T

s represents the switching time of the control laser. These results highlight the advantages of the standing wave control field, which significantly prolongs the storage time of the probe field within the crystal, limited only by the lifetime of the ground state

3H

4. This makes the standing wave configuration a superior choice for quantum memory applications.