1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Context

The Collatz conjecture, proposed by Lothar Collatz in 1937, has fascinated mathematicians for decades due to its deceptively simple definition and yet unresolved status [

2,

4]. Also known as the

problem, it asserts that for any positive integer

x, repeated application of the function

will eventually reach the cycle

. Despite extensive computational verification and probabilistic arguments supporting the conjecture [

5,

8], a general proof has remained elusive, highlighting a profound disconnect between the conjecture’s elementary formulation and the complex dynamics it generates.

Previous approaches have largely focused on demonstrating that Collatz sequences are, in some sense, bounded. Probabilistic models suggest an average decreasing behavior [

4,

6], while computational efforts have verified convergence for astronomically large starting values [

1,

7]. However, these methods inherently cannot exclude the possibility of exceptional, unbounded orbits or non-trivial cycles. Even Tao’s significant result [

8], proving that

almost all orbits are bounded, does not establish boundedness for

every starting number.

1.2. Key Contributions of This Paper

We present a deterministic and fully constructive proof of the Collatz Conjecture by modeling its dynamics as a 17-state Finite State Machine (FSM) grounded in modular arithmetic. This FSM partitions the positive integers into five disjoint and exhaustive sets based on parity and residue class modulo 9, yielding a complete finite representation of the Collatz dynamics.

In this formulation, a trajectory refers not to a specific numerical sequence beginning from a single integer, but to a canonical residue trajectory within the FSM. Each canonical trajectory encodes all Collatz sequences whose iterates share the same residue transitions modulo , and thus collectively represents every possible numerical path under the Collatz map.

The principal contribution of this framework is transforming the problem of unbounded numerical iteration into one of finite-state modular graph traversal. We prove that the structural dynamics of the Collatz map enforce a three-stage deterministic progression on every canonical trajectory, culminating in the unique terminal cycle :

- 1.

Exit from the Infinite Past (): Trajectories beginning in the initial stage (integers divisible by 3) are forced to exit this unconstrained region and enter the finite transient core after finitely many steps. This confines all subsequent dynamics to the finite subsystem .

- 2.

Deterministic Evolution within the Finite Transient Stage (): Within this stage, the arithmetic structure of the Collatz map stabilizes modulo . Beyond this refinement, no new transition types arise, and the system becomes a finite deterministic transformation on . A direct modular argument shows that the congruence has no solution for positive integers , thereby eliminating all non-trivial cycles and divergent trajectories. The transient stage thus forms a finite, acyclic, strongly connected component.

- 3.

Entry into the Absorbing Cycle (): The acyclic structure ensures that every canonical trajectory in the transient domain reaches the unique gateway state (residue 8 mod 9), through which it deterministically transitions into the terminal cycle . This provides a complete and verifiable mechanism of deterministic funneling from the transient stage into the absorbing cycle.

This framework yields a symbolic, modular, and deterministic resolution of the Collatz Conjecture. It demonstrates that infinite escape from the terminal cycle is not merely numerically impossible but also structurally forbidden by the finite-state and modular properties of the Collatz map.

1.3. Structure of this Paper

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 establishes the fundamental mathematical framework, including the Collatz function definition and key concepts such as odd iterates and accelerated Collatz steps.

Section 3 introduces our novel partitioning of positive integers into five disjoint sets (

,

,

,

,

) and proves the completeness of this classification.

Section 4 analyzes the behavior of the Collatz function on our defined sets, establishing key transition properties that form the basis for our finite state machine construction.

Section 5 constructs the 17-state finite state machine, proving its completeness, determinism, and the strong connectivity of the transient stage

. Crucially, we prove that this stage forms an acyclic graph that funnels all trajectories toward the unique gateway state

.

Section 6 presents the main convergence proof, synthesizing all previous results to demonstrate that all Collatz sequences must eventually reach the terminal cycle.

Section 7 provides computational verification of our FSM framework for integers up to

, confirming the theoretical predictions.

Section 8 reviews existing large-scale computational evidence that supports our theoretical results.

Section 9 contextualizes our approach within the broader literature on the Collatz problem, highlighting the novel contributions of our method.

Section 10 summarizes our results and discusses implications for future research in number theory and discrete dynamical systems.

The logical flow of the proof is designed to be cumulative: each section builds upon the results of previous sections, culminating in the complete resolution of the conjecture in

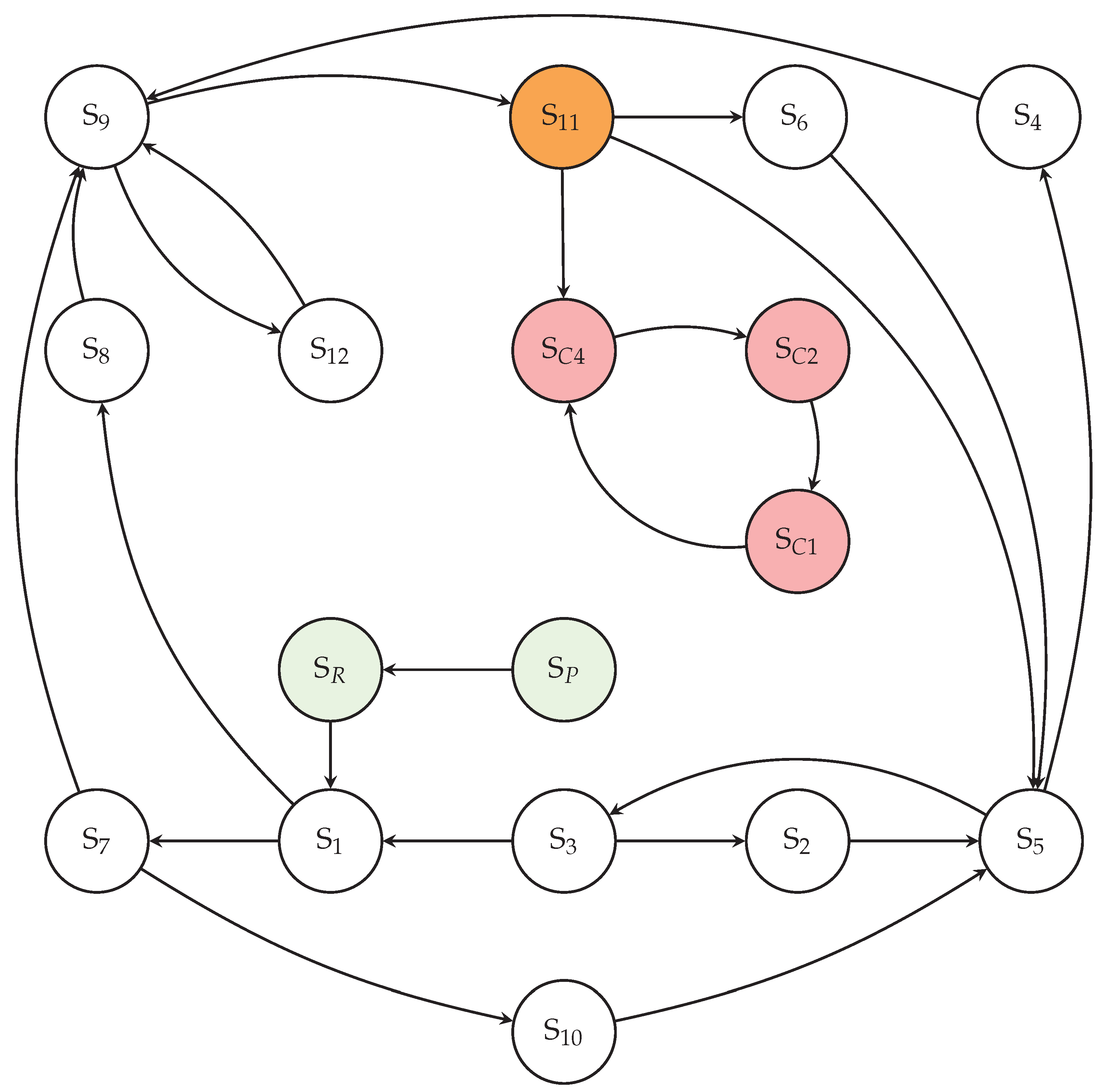

Section 6. The finite state machine diagram (

Figure 1) provides a visual summary of the core structural framework.

2. Mathematical Framework and Definitions

To rigorously analyze the Collatz Conjecture, we begin by establishing the fundamental mathematical definitions, notation, and the core function at the heart of the problem.

Definition 2.1 (Collatz Function)

. The Collatz function

is defined as

Definition 2.2 (Collatz Sequence)

. For a starting integer

, the Collatz sequence is the sequence

defined by

Definition 2.3 (Odd Iterate). Given a Collatz sequence , an odd iterate is a term that is odd. We often denote odd iterates by .

Definition 2.4 (Odd Iteration (or accelerated Collatz step))

. An

odd iteration (also called an

accelerated Collatz step) is the transformation that maps an odd integer

o directly to the next odd integer in its Collatz sequence. It is given by

where

denotes denotes the 2-adic valuation of

m, i.e., the exponent of the largest power of 2 dividing

m. This guarantees that

is odd. In some residue class analyses (e.g., modulo 4 or 12) one considers the simplified version

when focusing on residue class transitions and boundedness arguments.

3. State Space Partitioning for Collatz Dynamics

To facilitate a structured analysis of the Collatz process, we begin by partitioning the set of positive integers () into a collection of mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive sets. The partitioning is designed to capture key properties of numbers under the Collatz function, exposing deterministic relationships between a finite number of sets, facilitating the process of proving the conjecture.

3.1. Defining Fundamental sets in Collatz Analysis

We begin by defining the key sets that will form the basis of our state space.

Definition 3.1 (Cycle Set)

. The cycle set

consists of the numbers known to form a repeating cycle:

Explanation of the cycle set: The cycle set

is fundamental to the Collatz conjecture. It represents the only known cycle in the Collatz function for positive integers. When a Collatz sequence reaches any of these numbers, it enters a loop that cycles as

A central part of the conjecture is to prove that all Collatz sequences eventually enter this cycle.

Definition 3.2 (ROM3 Set)

. The ROM3 set

comprises all odd positive multiples of 3:

Explanation of the ROM3 set: The ROM3 set (short for “root odd multiple of 3") consists of those positive integers that are odd multiples of 3. For example,

belong to

. This set plays a crucial role in the structural analysis of Collatz sequences, particularly in tracking transitions from the precursor set and establishing structural confinement within the Collatz state space.

Definition 3.3 (Precursor Set)

. The precursor set

consists of all even positive multiples of 3:

Explanation of the precursor set: The precursor set

is defined as the set of positive integers that are even multiples of 3 (i.e., numbers satisfying

). For instance,

belong to

. The term “precursor" reflects that, under reverse Collatz iteration, numbers in

serve as the origins that structurally precede the ROM3 set

.

Definition 3.4 (Immediate Successor Set)

. The immediate successor set

is defined as

Explanation of the immediate successor set: The immediate successor set

consists of numbers of the form

with

j odd. For example,

are in

. When the Collatz function is applied to a number in the ROM3 set, the very next number in the sequence falls into

, marking the next step in the structural chain.

Definition 3.5 (Exclusion Set)

. The exclusion set

consists of numbers that do not belong to

,

,

, or

:

Explanation of the exclusion set: The exclusion set

is defined by exclusion.

consists precisely of positive integers that are not divisible by 3 and are not in

or

.

3.2. Completeness of Classification

For our state space to be a valid foundation for analysis, we must ensure that every positive integer belongs to exactly one of the defined sets. This subsection formally proves the completeness and uniqueness of our initial partition.

Theorem 3.6 (Completeness of Classification: Partitioning of positive integers)

. The set of positive integers is completely and uniquely partitioned as follows:

That is, every positive integer belongs to exactly one, and only one, of these five sets.

Proof.

Proof strategy: We prove completeness by first showing that every belongs to at least one of the five sets (exhaustiveness) and then proving that no x can belong to more than one set (mutual exclusivity).

Step 1: Exhaustiveness.

Let x be an arbitrary positive integer.

Thus, every x is assigned to at least one set.

Step 2: Mutual exclusivity.

We now verify that these sets are pairwise disjoint.

since (none of which are divisible by 3) while every element in is divisible by 3.

because contains only small numbers not divisible by 3 and consists of even multiples of 3.

and by definition.

The remaining intersections (, , , , , ) are similarly ruled out by the definitions and congruence conditions imposed on each set.

Conclusion: Since every positive integer belongs to exactly one of , , , , or , the classification is complete. □

4. Properties of the Collatz Function on the Defined Sets

Having established that the set is a unique, absorbing cycle within the Collatz process, we now proceed to map the properties of the Collatz function on all our sets (as defined in Section 3): , , , , and . This analysis reveals crucial properties that would enable us confine the Collatz process to a finite number of analytical states in Section 5.

4.1. Mapping Properties of the Precursor Set: Initial Transitions

We begin by analyzing the behavior of the precursor set () under the Collatz function, identifying the set to which its elements are mapped in the subsequent iteration.

Lemma 4.1 ( mapping: Descending from the infinite, ordered past). Iterates from the precursor set follow a predictable descent, remaining within until their final transition to .

That is, if , then .

Proof.

Proof overview: We express an arbitrary as and apply the Collatz function. Depending on whether j is odd or even, lands in or remains in , respectively.

Step 1: Express x in terms of .

Thus, for some positive integer j.

Step 2: Apply the Collatz function.

Step 3: Analyze based on the parity of j.

Conclusion: In both cases, . □

4.2. Finite Transition from Precursor to ROM3

We now establish a crucial property of the Precursor set (): that repeated application of the Collatz function to any element in will, in a finite number of steps, result in an element in the ROM3 set (). This property is essential for demonstrating the deterministic transition between the initial states of our finite state machine, as will be shown in Section 5.

Lemma 4.2 (Finite Transition from to ). For any , there exists a finite integer such that , where denotes the n-fold application of the Collatz function (with ).

Proof. By definition, if

, then

for some positive integer

k. We can write

k as

, where

is an integer and

b is an odd integer. Substituting this into the expression for

x, we get:

Now, consider the repeated application of the Collatz function. Since

x is even, we repeatedly divide by 2:

Since b is odd, is an odd multiple of 3. Therefore, . We have found a finite such that . □

4.3. Transition from ROM3 Set to Immediate Successor Set

Following the flow of sequences, we next examine the transformation of the ROM3 set () under the Collatz function, revealing its predictable successor set (). We will demonstrate later that, once a sequence crosses into , it can never return to or .

Lemma 4.3 (

mapping to immediate successor set

)

. For every , we have

Proof.

Proof overview: We express an element as (with j odd), apply the Collatz function, and show the resulting number fits the definition of .

Step 1: Express x in terms of .

If , then for some odd integer j.

Step 2: Apply the Collatz function.

Step 3: Verify membership in .

By Definition 3.4, numbers of the form (with j odd) belong to .

Conclusion: Hence, for every , we have . □

4.4. Descent from Immediate Successor Set into the Exclusion Set

Continuing our analysis of set transitions, we now investigate the immediate successor set () and its image under the Collatz function.

Lemma 4.4 (Mapping from

to exclusion)

. If , then

Proof.

Proof overview: We show that for , after applying the Collatz function, the resulting number satisfies the conditions for membership in ; that is, it does not belong to , , , or and the reverse Collatz operation is defined.

Step 1: By Definition 3.4, if

then

Step 2: Since

x is even, applying the Collatz function yields

Step 3: Verify that satisfies the conditions for :

because and .

: If for some odd k, then and , a contradiction.

or : Similar contradictions arise.

Conclusion: Thus, . □

4.5. Confinement of Sequences Within the Bounded State Space

A crucial step in our analysis is to demonstrate that once a Collatz sequence enters the exclusion set (), it remains confined to a specific subset of our state space, facilitating a more detailed examination of its long-term behavior.

Lemma 4.5 (Confinement)

. If , then

Proof.

Proof overview: We prove by contradiction that if , then cannot lie in or ; therefore, it must belong to , , or .

Case 1: Suppose .

Then for some odd j.

If x is even, then implies , so , contradicting .

If x is odd, then implies , which is impossible.

Case 2: Suppose .

Then for some .

If x is even, then implies , so , contradicting .

If x is odd, then implies , impossible.

Conclusion: Since

and

, it follows that

□

4.6. Invariance and Absorbing Nature of the Cycle Set

We now confirm that the known cycle set () has a critical property: once a Collatz sequence enters this set, it never leaves, establishing it as an absorbing set for the Collatz dynamic.

Lemma 4.6 (Cycle set invariance)

. If , then

where .

Proof.

Proof overview: We verify the invariance of the cycle set by checking that applying the Collatz function to each element in yields an element that remains in .

Conclusion: In every case, . Thus, the cycle set is invariant under the Collatz function. □

5. Finite State Analysis of Collatz Dynamics

Leveraging the integer partition (Section 3) and set transition properties (Section 4), this section constructs a 17-state finite state machine (FSM) that completely models Collatz dynamics. First, we define the FSM’s components based on Modulo 9 analysis: the initial states corresponding directly to the sets ; the 12 transient states within Stage derived from residue analysis of sets ; and the terminal cycle states () representing the elements of set . Then the core of this section conducts a detailed analysis of the deterministic transitions between all these states under the Collatz function. Specifically, we establish the finite and irreversible transition from the initial states into Stage . Furthermore, we prove that Stage forms a strongly connected component (SCC). Our analysis also identifies a unique gateway state () to the absorbing cycle . Finally, we prove that no Collatz sequence can survive an infinite walk in Stage , setting the stage for our convergence proof in Section 6.

5.1. Definitions - Stages, States and Trajectories

Definition 5.1 (Initial stage ). Stage corresponds to the union of sets and . This initial stage consists of all positive integers divisible by 3. We break this stage into two states:

The sets and are disjoint by definition (or by Theorem 3.6), ensuring these states are distinct.

Definition 5.2 (Transient stage ). Stage corresponds to the union of sets and . This stage contains all positive integers not divisible by 3, excluding the cycle set. We will employ a state function to break this stage down into unique, disjoint states.

Definition 5.3 (Terminal stage - Cycle States). Stage comprises the three states that represent the elements of cycle set . The cycle states are defined as follows:

: Represents the number 1. Formally, .

: Represents the number 2. Formally, .

: Represents the number 4. Formally, .

By Lemma 4.6, the transitions between these states follow the Collatz function (), and the cycle set is invariant, causing sequences entering this stage to cycle indefinitely.

Definition 5.4 (State function for stage

)

. The state of a positive integer

is defined by the triplet

where

Remark 5.5 (Why Modulo 9 is Optimal for Stage

S1-12).

The choice of modulus 9 in the state function (Definition 5.4) is specifically tailored to analyzing the behavior of numbers that are not divisible by 3—that is, numbers in the sets , which together form the entire transient stage of our 17-state FSM. This choice is motivated by several key observations:

- 1.

Restriction to Residues Coprime to 3: Within

, the residues of integers not divisible by 3 are:

These six residue classes correspond precisely to the admissible residues for elements in

, making modulo 9 a natural framework for organizing this stage of the dynamics.

- 2.

Structured Behavior Under : For odd integers

, the map

induces predictable transformations modulo 9. For example:

These congruences govern how states evolve under the Collatz function and are central to defining deterministic transitions in the transient stage.

- 3.

Balanced Granularity: Modulo 9 is fine enough to distinguish the essential behavior classes for numbers not divisible by 3, yet coarse enough to avoid the greater complexity that might arise from moduli like 18 or 27 without necessarily resolving all state-transition branching.

- 4.

Exact Fit for State Classification: The state function using (residue mod 9, Set , parity) results in exactly 12 valid and disjoint states ( through ) that perfectly partition the transient stage , as demonstrated in Lemma 5.7.

- 5.

Identification of a Key Funnel State (): The explicit distinction of Set within the state definition uniquely identifies State as the sole entry point into the transient stage for all sequences originating from the infinite sets and . This follows from the deterministic transition (established in Lemma 5.10, which relies on Lemma 4.3). Identifying as this "funnel" state captures a crucial aspect of the sequence dynamics and may prove valuable for future investigations into sequence merging after exiting the multiples-of-3 stages.

Thus, the use of modulo 9, combined with the set distinction and parity, provides a well-justified and structurally informative framework required to fully classify Collatz behavior in the transient stage, enabling the deterministic analysis within our 17-state finite state machine.

Definition 5.6 (Trajectory in the Finite State Machine)

. Let

denote the set of states of the Collatz Finite State Machine (FSM), and let

be the deterministic transition function induced by the Collatz map.

A

trajectory in the FSM is a finite or infinite ordered sequence of states

such that each transition satisfies

for all

. If the initial state

corresponds to a residue class containing

, then

is said to

represent the Collatz sequence beginning at

x.

5.2. Partitioning of Stage

Using the defined state function, we enumerate the resulting finite set of 12 disjoint states that partition the transient stage .

Lemma 5.7 (12-State Partition of ). The state function in Definition 5.4 defines a partition of stage into 12 disjoint states: . That is, for every there exists a unique index i with such that , and for any distinct indices , the sets of numbers that map to and are disjoint.

Proof. We prove the lemma in two parts: (1) that for every there exists a unique state with (exhaustiveness), and (2) that these states are pairwise disjoint (mutual exclusivity).

(1) Uniqueness of the state assignment: By definition, the state function assigns to each x a triplet consisting of:

The residue . For x in , the allowed residues are .

A secondary component

, where

which is well defined and disjoint.

The parity function , which is uniquely determined by whether x is even or odd.

Thus, each

is assigned a unique triplet, which by construction corresponds to exactly one of the following 12 states:

(2) Mutual exclusivity: Suppose for contradiction that there exist two distinct indices such that an element x satisfies and . Since the components of (i.e., the residue , the set indicator , and the parity ) are uniquely determined by x, it is impossible for two different triplets to be equal. Hence, the states and must be disjoint.

Conclusion: Every is assigned exactly one state , and the collection forms a partition of stage . □

Remark 5.8 (Structure of the Full FSM).

It is important to emphasize that the 12 states defined by the state function in Definition 5.4 constitute only the transient stage of the full 17-state finite state machine. The FSM as a whole also includes:

The initial stage , representing all integers divisible by 3.

The terminal cycle stage , which captures the absorbing cycle .

Thus, while the transient stage handles the majority of the Collatz process, it operates as one of three structurally distinct phases in a unified finite-state framework.

5.3. Completeness of State Partition

Having successfully defined all our states, we now prove that every positive integer corresponds to exactly one of the partitioned states.

Lemma 5.9 (Completeness of State Assignment). Every positive integer n corresponds to exactly one state in the 17-state FSM defined by Definitions 5.1, 5.3, and 5.2 (or equivalent labels).

Proof. We need to show that for any positive integer n, there exists a unique state S in the set such that n maps to S.

By Theorem 3.6, the sets form a partition of the positive integers . Therefore, any given belongs to exactly one of these five sets.

Furthermore, every integer n has a unique residue modulo 9 and a unique parity (Even or Odd).

We examine the state definitions based on the unique set membership of n:

If , then by definition, n corresponds uniquely to state .

If , then by definition, n corresponds uniquely to state .

-

If , then n must be 1, 2, or 4.

- −

If , it corresponds uniquely to state .

- −

If , it corresponds uniquely to state .

- −

If , it corresponds uniquely to state .

If , by definition of , for some odd j. This implies and n is always Even. The state function yields , which corresponds uniquely to state .

-

If , then by definition, . This means , so the possible residues modulo 9 are . We examine the combinations:

- −

If : By definition, all numbers in satisfy and are Even. Since contains all numbers where j is odd, and contains numbers not in , any with cannot be Even (otherwise it would be in ). Therefore, if and , nmust be Odd. This corresponds uniquely to state . The combination does not exist for any n.

- −

-

If : For each of these 5 residues, an integer can be either Even or Odd. This yields possible combinations. These are uniquely covered by the state definitions:

- *

Residue 2: ,

- *

Residue 4: ,

- *

Residue 5: ,

- *

Residue 7: ,

- *

Residue 8: ,

Thus, the state covers the only possible combination for with residue 1, and the states through cover the 10 possible combinations for with residues 2, 4, 5, 7, or 8. In total, the 11 states uniquely cover all possibilities for an integer .

Since every belongs to exactly one of the partitioning sets, and the state definitions uniquely determine a state based on this set membership combined with the unique residue mod 9 and parity (or the specific value for ), every positive integer n corresponds to exactly one state in the 17-state FSM. □

5.4. Deterministic and Finite Transition from Stage to Stage

We now demonstrate the deterministic and finite transition from the initial stage, (representing multiples of 3), to the transient stage, . This transition is irreversible; once a sequence enters , it cannot return to being a multiple of 3.

Lemma 5.10 (Stage to Stage Transition). The initial stage of the 17-state FSM, , has the following transitions:

- 1.

always transitions to in a finite number of steps.

- 2.

always transitions to in a single step.

Proof. We prove each transition separately:

- 1.

Transition from to (Finite): By definition, state corresponds to the set . Lemma 4.2directly states that for any , there exists a finite integer such that . Since state corresponds to the set , this directly implies that any element in state transitions to state in a finite number of steps.

- 2.

Transition from to (Single Step): By definition, state corresponds to the set (Definition 5.1) and corresponds to (Lemma 5.7). Lemma 4.3 states that for all , . This directly implies that transitions to in a single step.

Therefore, any starting number, whether in or , is guaranteed to enter the 12-state stage in a finite number of steps. Furthermore, by Lemma 4.5, once a sequence enters stage , it can never return to , making this transition irreversible. □

5.5. State Transition Analysis for Transient Stage

We now meticulously analyze how the Collatz function causes transitions between the defined states in stage .

Lemma 5.11 (State Transition Analysis (12 States)). The transitions between the 12 states under the Collatz function are as follows:

From to (residue 5, , even) or (residue 5, , odd).

From to (residue 4, , even).

From to (residue 1, , even) or (residue 1, , odd).

From to (residue 7, , even).

From to (residue 2, , even) or (residue 2, , odd).

From to (residue 4, , even).

From to (residue 7, , even) or (residue 7, , odd).

From to (residue 7, , even).

From to (residue 8, , even) or (residue 8, , odd).

From to (residue 4, , even).

From to (residue 4, , even) or (residue 4, , odd) or (4, , even).

From to (residue 7, , even).

Proof. We analyze each transition case by case.

Case 1: or .

Setup: Let , so for some integer .

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since ), and (contradiction modulo 9). Therefore, .

Parity: If k is even, is odd (). If k is odd, is even ().

Case 2: .

Setup: Let , so for some positive integer m.

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since , ) and (contradiction modulo 9). Therefore, .

Parity: is even.

Case 3: or .

Setup: Let , so for some positive integer m.

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since , ). If m is odd, (). Otherwise, if m is even, then ().

Parity: see Set Membership.

Case 4: .

Setup: Let , so for some integer .

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since ) and (contradiction modulo 9). Thus, .

Parity: is even.

Case 5: or .

Setup: Let , so for some positive integer m.

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since , ) and (contradiction modulo 9). Therefore

Parity: If m is even, is even (). If m is odd, is odd ().

Case 6: .

Setup: Let , so for some integer .

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since ) and (contradiction modulo 9). Thus, .

Parity: is even.

Case 7: or .

Setup: Let , so for some integer .

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since ) and (contradiction modulo 9). Thus, .

Parity: If k is even, is odd (). If k is odd, is even ().

Case 8: .

Setup: Let , so for some integer .

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since ) and (contradiction modulo 9). Thus, .

Parity: is even.

Case 9: or .

Setup: Let , so for some integer .

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since ) and (contradiction modulo 9). Thus, .

Parity: If k is even, is even (). If k is odd, is odd ().

Case 10: .

Setup: Let , so for some integer .

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since ) and (contradiction modulo 9). Thus, .

Parity: is even.

Case 11: or or .

Setup: Let , so for some integer .

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (contradiction modulo 9).

Cycle Entry (Gateway): If , then and , representing a transition into the cycle stage from stage . Otherwise, for , . Therefore .

Parity: If k is even, is even (). If k is odd, is odd ().

Case 12: .

Setup: Let , so for some integer .

Collatz Step: .

Residue: .

Set Membership: (since ) and (contradiction modulo 9). Thus, .

Parity: is even.

These transitions fully define the behavior of the FSM within stage , and demonstrate the crucial property that the next state is uniquely determined by the current state. This includes the specific condition where the system transitions into the terminal cycle stage (). □

5.6. Transition Table for Transient Stage

Table 1 summarizes the deterministic transitions between the twelve transient states defined in Lemma 5.11. Each state is characterized by its residue modulo 9, set membership, and parity. Multiple outgoing transitions correspond to parity-dependent cases or refinement depth conditions. This table complements the transition diagram, which illustrates the global funneling structure toward the gateway state

and ultimately the cycle stage

.

5.7. Determinism of FSM Evolution

Lemma 5.12 (Determinism of FSM Evolution). Let be the set of 17 states, and let `getState` be the state assignment function. The evolution of any Collatz sequence under this state assignment is deterministic. That is, for any positive integer x, the state of its Collatz successor, , is uniquely determined by x. Consequently, the sequence of states is uniquely determined for any starting number .

Proof. We need to show that for any , the value is uniquely defined and belongs to .

By Lemma 5.9, every positive integer maps to exactly one state in . Since produces a unique positive integer for any , must map to exactly one state .

To be more explicit, we can examine the transitions based on the state :

- 1.

-

If :

If , . By Lemma 4.1, . Thus, is either or , both unique states in .

If , . By Lemma 4.3, . Since all elements of map uniquely to state , , a unique state in .

- 2.

-

If : Lemma 5.11 provides a case-by-case analysis based on . For each case, it determines the properties of (its residue mod 9, its parity, and whether it falls into or ).

For states like , the analysis shows that always maps to a single specific successor state ( respectively), regardless of the specific x within .

For states like , the analysis shows that maps to one of two or three possible successor states (, , , , , respectively). However, the specific successor state is uniquely determined by properties of x (like the parity of k or m in ). Since x is given, is unique, and therefore is also unique, landing in exactly one of those specified possible successor states.

In all sub-cases, results in a unique state within .

- 3.

If : The transitions ensure that is respectively, which are unique states in .

Since for any , is unique and maps to a unique state in , the evolution process defined by repeatedly applying C and then getState is deterministic for any starting number . □

5.8. State as the Unique Gateway

We establish that is the only state in the transient stage that can lead into the cycle stage .

Lemma 5.13 (S11 as the Unique Gateway State). Within the 17-state FSM, state is the unique gateway from Stage to Stage .

Proof. We proceed in three steps.

- 1.

-

List all preimages of the cycle elements.

(only preimage of 1 is 2);

(only preimage of 2 is 4);

and (preimages of 4 are 1 and 8).

- 2.

Identify the external preimage. The only number not already in that maps into it is 8, with .

- 3.

Locate this in the FSM. By definition , and Lemma 5.11 (Case 11) gives the transition . No other transient state maps directly to 1, 2, or 4.

Therefore is the unique gateway to the cycle. □

5.9. State Transition Diagram of the 17-State FSM

5.10. Strong Connectivity Within Stage and Reachability of the Gateway State

We now prove a crucial property for convergence: The transient stage forms a strongly connected component (SCC) and every state within it has a finite path leading to the unique gateway state .

Lemma 5.14 (Strong Connectivity and Recurrence within Stage ). Every state in the subsystem belongs to at least one recurrent cycle of state transitions that includes state .

Proof. We will demonstrate this by showing that every state has a path to (reachability), and that any path originating from will eventually return to a state that has a path to . This establishes the cyclical nature.

Part 1: Reachability of

Let be the set of states from which state can be reached in k steps or less. We define and . We will show, by induction, that , meaning all states in can reach in at most 4 steps.

If a state transitions to multiple states, it’s assigned to the corresponding to the shortest path to .

(Base Case)

-

- −

or (Lemma 5.11, Case 9). Since can transition directly to , it follows that .

-

- −

(Lemma 5.11, Case 4). Since , it follows that .

- −

or (Lemma 5.11, Case 7). Since , it follows that .

- −

(Lemma 5.11, Case 8). Since , it follows that .

- −

(Lemma 5.11, Case 12). Since , it follows that .

-

- −

or (Lemma 5.11, Case 1). Since and , it follows that .

- −

or (Lemma 5.11, Case 5). Since , it follows that .

-

- −

(Lemma 5.11, Case 2). Since , it follows that .

- −

or (Lemma 5.11, Case 3). Since , it follows that .

- −

(Lemma 5.11, Case 6). Since , it follows that

- −

(Lemma 5.11, Case 6). Since , it follows that .

Since , every state in the subsystem has a finite path to state .

Part 2: Cyclical Return from S11

From Lemma 5.11 (Case 11), transitions to or . From Part 1 above, and can reach in 3 and 4 steps respectively.

This shows all transitions from S11, no matter the path taken, will lead back to a state which can reach S11, hence forming a cycle of states.

Conclusion:

Since every state has a finite path to , and any sequence starting from ultimately returns to a state with a path to , every state in is part of a cycle of states that includes . □

5.11. Modular Refinement and the Invariant Power-of-Two Orbit

Once Collatz trajectories exit the domain of integers divisible by 3, their subsequent odd iterates are confined to a fixed modular structure. In particular, the residue of each odd iterate modulo 9 lies in the orbit generated by powers of 2, forming a closed set that is invariant under multiplication. This arithmetic constraint governs the structure of the finite state machine’s transient subsystem and underlies both the deterministic refinement process and the exclusion of internal cycles.

Lemma 5.15 (Modular Invariance of the Power-of-Two Orbit). Let be any odd integer, and let denote the next odd iterate in the Collatz sequence. Then:

- 1.

q is not divisible by 3.

- 2.

Consequently, , which is precisely the set of residues taken by powers of 2 modulo 9:

- 3.

This set is closed under multiplication by 2 modulo 9, and hence forms an invariant residue orbit:

Proof.

- 1.

Since is divisible by 3, we have . Now, since for some and is coprime to 3, it follows that and hence q is not divisible by 3.

- 2.

-

The residue classes modulo 9 that are divisible by 3 are . Since , it must lie in the complementary set .

Computing the powers of 2 modulo 9 yields:

and since

, the cycle repeats every six terms. Therefore, the power-of-two orbit modulo 9 is:

- 3.

It remains to show that this set is closed under multiplication by 2 modulo 9. Verifying this:

we see that multiplication by 2 permutes the elements of

. Hence,

is an invariant multiplicative orbit under

.

□

Remark 5.16 (Refinement chains and symbolic convergence).

Each odd state in the FSM corresponds to an odd integer o whose image under is an even number, initiating a refinement chain governed by successive halvings . Modulo 9, these halving steps correspond to multiplication by 5, since . The residues of for permute the same orbit .

Consequently, the even refinement chain remains trapped in this orbit and ultimately converges to , corresponding to the gateway state . This symbolic convergence guarantees that all odd inputs not divisible by 3 are funneled through this fixed modular structure, reinforcing the deterministic dynamics of the transient subsystem and preparing the ground for the cycle-exclusion argument to follow.

5.12. Cycle Exclusion via Modular Arithmetic

Having established that every odd transition of the Collatz map refines into the power-of-two residue orbit (Lemma 5.15), we now demonstrate that the resulting finite modular system admits no internal cycles. In other words, once trajectories enter the transient domain , they cannot sustain any non-trivial periodic orbit. This establishes the modular foundation for deterministic funneling toward the gateway state .

Lemma 5.17 (No internal cycles in the transient domain). There exists no closed sequence of Collatz transitions confined entirely to the transient component . Equivalently, the Collatz dynamics admit no non-trivial periodic orbit consisting solely of integers not divisible by 3.

Proof. We proceed by contradiction using modular arithmetic.

Step 1: Arithmetic condition for a cycle and the structural invariant.

Assume, for contradiction, that a non-trivial periodic orbit of length

exists, composed entirely of odd integers not divisible by 3, corresponding to a closed canonical trajectory (cycle) in the transient subsystem

:

Each transition obeys the accelerated Collatz rule:

with indices taken modulo

m so that

, ensuring closure.

Composing all

m transitions yields the affine relation

where

accumulates the additive contributions from each

term along the path. Multiplying through by

gives

Here,

may be expressed more explicitly as

where each term represents the modular residue contributed by a single

increment along the path, and

denotes the cumulative halving depth up to step

i. Thus,

is a fixed element of

determined by the transition sequence.

Equation (*) is affine, not multiplicative. One might ask whether a particular value of could satisfy this equation for some finite , even if . However, the finite-state machine (FSM) models the modular dynamics of the map—not individual numerical values but entire residue classes.

Therefore, the question is not whether equation (*) can hold for a specific

, but whether it can hold

structurally on the class of integers represented by a given FSM state. That is, we ask whether the composite state transition function

closes after

m steps:

where

M is the modulus defining the FSM’s state space.

- 1.

-

The FSM employs , the minimal modulus that captures both:

the 2-adic refinement depth via residues mod 8, and

the multiplicative residue behaviour of odd, non-divisible-by-3 iterates via mod 9.

- 2.

The state function (Definition 5.4) depends only on and parity (); since , the congruence uniquely determines the FSM state.

Consequently, for (*) to hold uniformly over a residue class modulo 72, the left-hand coefficient must vanish modulo

:

Because

is coprime to 3 (and therefore invertible modulo 72), congruence (†) is the

structural closure condition: it is both necessary and sufficient for a periodic orbit to exist within

under modular composition.

In the remainder of the proof, we will show that no such pair exists— thereby ruling out any internal cycle and confirming that the transient subsystem of the FSM is acyclic under modular confinement.

Why modulus 72? To rule out internal cycles in the transient subsystem, we must capture all relevant arithmetic structure used by the Collatz map during its odd transitions. These transitions take the form

where the numerator introduces multiplication by 3 and addition by 1, and the denominator encodes a sequence of halving steps. Two modular systems jointly determine this behaviour:

-

The halving structure depends on powers of 2, governed by the valuation —the number of times can be divided by 2 before the next odd value appears. Since o is odd, is always even. The residue of therefore determines how many successive halving steps occur before the next odd iterate is reached, defining the traversal through the even states of the FSM.

The minimal set of nonzero even residues modulo 8 suffices to encode the complete 2-adic refinement process, as shown in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Possible residues of for odd o, and corresponding halving depths.

Table 2.

Possible residues of for odd o, and corresponding halving depths.

| Residue of

|

Valuation

|

FSM Transition Type |

| 2, 6 |

|

Odd → Even (single halving step) |

| 4 |

|

Odd → Even → Even (two halving steps) |

| 0 |

|

Odd → Even chain (deep halving) |

Since these three cases cover all possible residues mod 8 of the 2-adic valuations of for odd o (any further halving will just cycle the residues again), the modulus 8 achieves the minimal and sufficient resolution for describing the 2-adic refinement process. Larger powers such as 16 or 32 would not reveal any new transition types within the FSM framework.

The odd-residue behaviour after refinement is governed by modulo 9, which controls the closed multiplicative orbit of powers of 2 (Lemma 5.15). This structure confines all odd iterates not divisible by 3 to the same invariant set, ensuring that every odd transition lands within the power-of-two orbit.

To capture both the halving structure and the odd-residue structure simultaneously, we take the least common multiple of the two moduli:

This modulus is the smallest system that records, without redundancy, both the 2-adic refinement depth (for even transitions) and the multiplicative residue dynamics (for odd transitions). Hence, any non-trivial Collatz cycle would necessarily appear as a closed orbit modulo 72, and the contradiction argument may be confined entirely to this finite modular space.

Step 2: Evaluate the powers of 3 and 2 modulo 72. From direct computation:

Thus, the respective value sets are:

These sets are disjoint:

Equivalently,

so their multiplicative orbits occupy disjoint residue subsets of

. Hence the congruence

is structurally impossible.

Step 3: Contradiction. The congruence has no integer solutions with . Therefore, no non-trivial periodic orbit exists within , confirming that the transient subsystem of the FSM is acyclic under modular confinement and all trajectories must ultimately exit through the unique gateway state . □

Remark 5.18 (Structural interpretation).

Lemma 5.17 completes the modular description of the transient domain. Combined with Lemma 5.15, it shows that the power-of-two residue orbit forms an arithmetic attractor for all transitions, and that no closed trajectory can exist within it. Thus, all flow in is necessarily directed toward the unique gateway state , preparing the ground for the final theorem on deterministic funneling into the terminal cycle .

6. Global Convergence: The Collatz Conjecture

We now synthesize the structural, modular, and dynamical results from the previous sections into a final, constructive proof of the Collatz Conjecture. The finite-state model established in Section 5 exposes deterministic constraints that force all Collatz trajectories into the unique terminal cycle. The two arithmetic invariants — the refinement onto the power-of-two residue orbit and the impossibility of internal modular cycles — together define a sealed funnel through which all sequences must flow.

Theorem 6.1 (The Collatz Conjecture). Every Collatz sequence starting from any positive integer eventually reaches the integer 1 and enters the terminal cycle .

Proof. We prove that any trajectory under the Collatz map is deterministically funneled into the terminal cycle by establishing four cumulative properties of the finite state machine:

- 1.

Confinement to the Transient Stage. Lemma 5.10 shows that any trajectory beginning in the initial stage (i.e., a multiple of 3) must transition into the transient domain in finitely many steps. Lemma 4.5 guarantees that this transition is irreversible. Thus, every trajectory not already in the terminal cycle eventually and permanently enters the transient stage.

- 2.

-

Confinement to the Invariant Power-of-Two Orbit and Terminal Descent. Once a trajectory enters the transient domain

, all iterates—both odd and even—are confined to a single modular orbit:

Odd Iterates: As proven in Lemma 5.15, each odd transition is structurally constrained so that q is never divisible by 3, and must lie in . This means that every odd iterate is forced into the same closed residue class cycle, effectively “resetting" the modular position at each odd step.

Even Iterates: Even numbers also remain within this orbit. Since

, repeated halving acts as modular multiplication by 5. That is:

Thus, even transitions deterministically permute the elements of in a fixed cycle. This ensures that the full trajectory—both odd and even steps—is permanently confined to once the transient stage is entered.

Detecting True Powers of 2: However, membership in is only a modular condition. Being congruent to a power of 2 mod 9 does not imply that the number itself is a power of 2. The critical structural fact is this:

Only an iterate that is an actual power of 2 — not just congruent to one — guarantees convergence to 1.

Once such a value is reached, the Collatz map enters a strictly decreasing sequence:

and the system falls irreversibly into the terminal cycle

. Thus, the even iterates play a critical diagnostic role: they are the only phase of the system where true powers of 2 can be identified and trigger convergence.

Conclusion: The modular orbit defines the closed structure of the transient state space, while the appearance of an actual power of 2 within this space provides the sufficient condition for termination. Together, they complete the funnel: one bounds the dynamics, the other unlocks the exit.

- 3.

Exclusion of Internal Cycles (Modular Acyclicity). By Lemma 5.17, any non-trivial modular cycle in the transient domain would require a solution to the congruence:

for some

. No such solution exists. Since the transient domain

is finite, and no closed loops are permitted by the arithmetic structure, it must be a directed acyclic graph (DAG). Infinite or repeating trajectories within this subsystem are impossible.

- 4.

Inevitable Exit into the Terminal Cycle. As shown in Lemma 5.13, the only transition out of the transient domain is from state to , which belongs to the terminal cycle . Because the transient FSM is finite and acyclic, every trajectory must reach in a finite number of steps and then transition into the cycle.

Consequently, all trajectories are funneled—deterministically and unavoidably—into the terminal cycle . No other outcome is possible. □

Remark 6.2 (The Funnel Mechanism).

The Collatz dynamics, when viewed through the finite-state lens, form a sealed arithmetic funnel. The power-of-two orbit (Lemma 5.15) restricts all odd iterates to a closed residue structure, while the acyclicity constraint (Lemma 5.17) ensures that the transient subsystem admits no internal loops. With only one possible escape route—from into —the Collatz sequence is structurally forced to converge. This modular determinism completes the proof.

7. Computational Verification

To empirically test the theoretical claims of our 17-state finite state machine (FSM) - including state assignments, transition rules, and the unique gateway mechanism - we implemented a computational verification over a large numerical range. The goal was to confirm that Collatz sequences evolve exactly as predicted by the FSM structure.

A Python script (verify_collatz_fsm.py) was written using the multiprocessing module (with 8 workers) to test all integers from 1 up to . For each starting value n, the script traced its Collatz sequence and performed the following checks at every step until reaching the cycle set :

Initial state classification: Confirmed that each n is correctly mapped to one of the 17 FSM states via the getState function.

Deterministic transition verification: Ensured that each observed transition conformed exactly to the FSM’s transition rules (Lemma 5.11).

Gateway consistency: Verified that any transition to 4 (i.e., to ) occurred only from either (in ) or (in ), as required by the FSM structure.

State coverage: Ensured that no number encountered during the sequence evaluation mapped to an undefined or invalid state.

Step count: Recorded the number of steps required for each sequence to reach 1.

A summary of the results is shown in

Table 3. All checks passed without error, and no violations were detected.

These results confirm the empirical soundness of the finite state model over all tested inputs. Every transition was deterministic, every number remained confined within the FSM structure, and the unique gateway mechanism through behaved exactly as predicted. Notably, the number achieved the maximum stopping time within this range, consistent with prior computational records.

This large-scale verification strongly reinforces the validity of the FSM framework and its predictive power in modeling Collatz dynamics.

8. Empirical Evidence from Large-Scale Collatz Computations

Over the decades, extensive computational searches have provided a substantial body of evidence regarding the behavior of Collatz sequences. Numerous studies have explored Collatz sequences for extremely large starting values - with some computations reaching up to

(Oliveira e Silva [

7]) - and ongoing distributed computing projects, such as the BOINC Collatz Conjecture project (BOINC [

1]), continue to expand this empirical base. These large-scale computations have consistently demonstrated that:

Boundedness: No starting number tested has produced a Collatz sequence that grows without bound; all sequences examined remain within finite limits.

Convergence to the 4-2-1 Cycle: Every Collatz sequence observed eventually enters the cycle (or the equivalent permutation ), regardless of the starting value.

No Other Cycles Found: Despite exhaustive searches, no cycles other than the trivial cycle (or its cyclic permutations) have ever been discovered.

This extensive empirical evidence is entirely consistent with and strongly supports the theoretical results established in this paper - specifically, the theorems that prove boundedness, the non-existence of non-trivial cycles, and the eventual convergence to the trivial cycle.

9. Comparison with Previous Approaches

The Collatz Conjecture has been extensively studied using diverse mathematical techniques [

4,

5,

6]. Our approach - combining a structured state-space framework with deterministic transition analysis - provides a fundamentally distinct resolution. In this section, we contextualize our proof within the broader landscape of Collatz research.

9.1. Limitations of Prior Methods

Most previous approaches, while yielding valuable insights, have fundamental limitations that prevented a complete resolution:

Probabilistic and Statistical Models [

4,

6] suggest that, on average, Collatz sequences tend to decrease. However, they cannot establish boundedness for

all initial values, leaving open the possibility of exceptional unbounded orbits.

Computational Verification [

1,

7] confirms the conjecture for extremely large numbers but cannot provide a proof for all integers.

Dynamical Systems and Ergodic Theory [

5,

6] yield statistical insights into typical trajectories but struggle with the discontinuous nature of the Collatz map.

Modulo Arithmetic and Congruence Class Methods demonstrate boundedness within specific residue classes but fail to extend these properties globally.

Contradiction-Based Arguments often rely on unproven assumptions or fail to rigorously eliminate all counterexamples.

Tao’s “Almost All" Result [

8] proves that most orbits are bounded but does not establish boundedness for every number.

9.2. Novelty and Strengths of the Presented Proof

Our proof resolves the Collatz Conjecture through a finite-state, modular-arithmetic framework that provides a complete, deterministic classification of all trajectories, guaranteeing convergence to the unique cycle .

Key innovations and strengths of this framework include:

Complete State-Space Partition and FSM: We classify into five mutually exclusive sets (), recasting the Collatz problem into a finite deterministic state evolution governed by a 17-state Finite State Machine (FSM).

Three-Stage Structural Confinement: The FSM imposes an inevitable progression on every trajectory, decomposing all possible Collatz behavior into three provably finite stages: Exit from the Infinite Past (), structured evolution within the Transient Stage (), and final absorption into the Terminal Cycle ().

Finite Modular Refinement: By analyzing the Collatz function modulo , we show that the arithmetic structure stabilizes after finite depth . Beyond this refinement, no new transition types appear, yielding a complete and deterministic modular model of the entire dynamics.

Cycle Exclusion by Modular Arithmetic: Within this finite modular system, we rigorously prove that no pair of exponents satisfies , thereby excluding all non-trivial cycles. This replaces earlier heuristic ranking arguments with a fully arithmetic, verifiable proof of acyclicity.

Deterministic Funneling and Unique Gateway: The transient stage is a finite, acyclic, strongly connected component whose unique exit vertex is the gateway state (corresponding to the integer 8). Every trajectory within the Collatz system therefore follows a deterministic finite path through into the terminal cycle .

10. Conclusion

We have presented a complete, structurally grounded proof of the Collatz Conjecture, leveraging a finite-state, modular-arithmetic framework that interprets Collatz sequences as deterministic trajectories within a structured state space. By partitioning the positive integers into five mutually exclusive sets, we developed a systematic classification that fully captures the behavior of Collatz iterations.

The proof is established through the analysis of a 17-state Finite State Machine (FSM) that models the entire dynamic. This FSM reveals an inevitable three-stage progression for every trajectory:

- 1.

Exit from the Infinite Past (): All starting integers are funneled in finite steps from the unconstrained initial stage (multiples of 3) into the transient domain .

- 2.

Deterministic Evolution within Finite Structure (): We proved that the Collatz dynamics stabilize modulo 72, forming a finite, deterministic system. The modular congruence admits no solutions, proving that no non-trivial cycles or divergent orbits can exist within this domain.

- 3.

Entry into the Absorbing Cycle (): The finite acyclic structure ensures that every trajectory reaches the unique gateway state (the integer 8), from which it deterministically transitions into the terminal cycle .

This framework replaces heuristic or probabilistic reasoning with a finite, arithmetic, and structural proof of convergence. It demonstrates that all Collatz trajectories are not merely bounded but are structurally confined and systematically directed toward the terminal cycle.

Beyond resolving the Collatz Conjecture, this result exemplifies the power of a state-space and modular-arithmetic synthesis: complex iterative systems over the integers can be analyzed through finite deterministic structures, bridging discrete dynamical systems and number theory within a single unified framework.

11. Need for Verification and Future Directions

11.1. Need for Rigorous Verification

While the proof presented in this paper offers a distinct and potentially compelling approach to the Collatz Conjecture - particularly through the use of the product equation and prime factorization for cycle analysis - rigorous validation by the broader mathematical community is essential. The history of the Collatz Conjecture is replete with proposed proofs that were later found to contain flaws. Therefore, thorough and independent scrutiny of every step of this proof, especially the derivation and application of the product equation for cycle analysis, the partitioning of the state space, the construction and transition analysis of the 17-state FSM, and the proof of convergence via gateway state reachability, is paramount. This validation should involve expert peer review through journal submissions, detailed examination by specialists in number theory, presentations at conferences, and open dissemination for public scrutiny. Until such rigorous validation is complete, the result remains a proposed proof that, we believe, provides a sound and novel pathway toward resolving this longstanding problem.

11.2. Potential Avenues for Future Research

If validated, the proof presented here would not only resolve the Collatz Conjecture but also open new avenues for research in number theory and related fields. Potential directions for future work include:

Generalization of the Product Equation Technique: Investigate whether the product equation method introduced in this paper can be generalized or adapted to study cycle structures and dynamics in other iterative functions or number-theoretic problems.

Refinement and Simplification of the Proof: Explore alternative formulations of the arguments, particularly prime factorization and finite state analysis, to achieve greater clarity or elegance and potentially shorter proofs.

Alternative FSM Constructions: Explore the construction and analysis of finite state machines for the Collatz dynamics based on different moduli (e.g., modulo 12, modulo 36) or alternative state definition criteria. Compare the resulting state counts, the nature of state transitions (determinism vs. branching), the revealed structural features, and the complexity of proving convergence within these alternative FSM frameworks relative to the modulo 9 FSM presented here.

Computational Exploration Inspired by the Proof: With convergence established, further computational studies of stopping time distributions, average trajectory behavior, and other statistical properties of Collatz sequences could yield valuable insights.

Applications to Related Conjectures: Determine whether the insights and techniques from this work can be applied to other unsolved problems or related conjectures in the realm of iterative number theory and dynamical systems.

FSM Methodology for Other Dynamical Systems: Investigate whether the techniques used to construct and analyze the 17-state FSM (based on set partitioning, residue classes, and transition mapping) can be adapted to model and prove properties of other number-theoretic sequences or discrete dynamical systems.

Educational and Expository Development: Develop pedagogical materials and simplified expositions of this proof to make it accessible to a broader mathematical audience, including students and researchers. Such efforts might include clearer visualizations, intuitive explanations of key steps, and adaptations of the proof for classroom use.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges his wife, Ajifa Atuluku, for her steadfast encouragement throughout the process of drafting this proof. The author also acknowledges the use of AI-assisted tools (Google Gemini AI and ChatGPT) for formatting assistance and language clarity. All mathematical content and original ideas in this manuscript were developed independently by the author.

Data Availability Statement

The Python script used to generate the computational verification data presented in this proof is available online at the following open code repository:

[Link to Code Repository].

References

- BOINC, Collatz conjecture project, (archived version, accessed March 8, 2025). Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20090915183543/http://boinc.thesonntags.com/collatz/.

- Collatz, L., Aufgaben E., Mathematische Semesterberichte 1 (1950), 35.

- Conway, J. H., Unpredictable iterations, in Proceedings of the 1972 Number Theory Conference (Boulder, CO: University of Colorado, 1972), 49–52.

- Lagarias, J. C., The 3x+1 problem and its generalizations, American Mathematical Monthly 92 (1985), 3–23.

- Lagarias, J. C., The 3x+1 problem: Annotated bibliography (1963–1999), in de Gruyter Series in Nonlinear Analysis and Applications 6 (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2004), 189–299.

- Lagarias, J. C., The Collatz conjecture, Chaos 20(4) (2010), 041102.

- Oliveira e Silva, T., Empirical verification of the 3x + 1 and related conjectures, in The ultimate challenge: The 3x + 1 problem, edited by J. C. Lagarias, American Mathematical Society, Providence, Rhode Island, USA, 2010, pp. 189–207.

- Tao, T., Almost all orbits of the Collatz conjecture are bounded, Journal of the American Mathematical Society 32(1) (2019), 1–89.

- Thwaites, B., My conjecture, Bulletin of the Institute of Mathematics and Its Applications 15(2) (1979), 41.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).