1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The Collatz conjecture, proposed by Lothar Collatz in 1937, has fascinated mathematicians for decades. Its statement is deceptively simple: take any positive integer. If it is even, divide it by two; if it is odd, multiply it by three and add one. The conjecture asserts that this process, repeated indefinitely, will always eventually reach the number 1.

Despite its elementary formulation, the conjecture has resisted proof, leading to Paul Erdős’s famous remark, "Mathematics may not be ready for such problems." Previous approaches have ranged from probabilistic arguments suggesting an average decreasing behavior to extensive computational verifications for astronomically large numbers [

1,

2]. While significant progress, such as Tao’s result that

almost all orbits are bounded [

3], has been made, a complete and deterministic proof has remained elusive.

1.2. Thesis: Convergence via Finite State Graph Structure

The proof presented herein establishes the Collatz Conjecture by demonstrating that its dynamics are governed by a finite, deterministic state transition system, rather than by chaotic or unbounded numerical behavior. We construct a 17-state Finite State Machine (FSM) that partitions all positive integers according to congruence properties intrinsic to the Collatz map.

The central argument rests on two key topological properties of this FSM’s directed graph:

- (1)

The FSM contains a single transient Strongly Connected Component (SCC) encompassing all states except those representing the terminal cycle .

- (2)

This transient SCC possesses exactly one exit transition, which leads irreversibly to the states representing the terminal cycle , forming the sink of the system.

These graph-theoretic properties—proven through exhaustive state transition analysis— constitute structural invariants of the Collatz map. By the fundamental principles of finite directed graphs, any infinite trajectory within the FSM must eventually traverse the unique exit and enter the terminal sink. Hence, convergence to the cycle emerges not as a probabilistic tendency or magnitude-based descent, but as a structural necessity dictated by the topology of the FSM itself.

1.3. Structure of the Paper

The paper follows a constructive approach, building the proof from foundational principles to its final, inescapable conclusion.

2. The Structure of the Funnel: A Foundational Partition of Integers

To prove that a funnel exists, we must first define its shape. This section partitions the set of all positive integers into a handful of mutually exclusive and exhaustive sets. This partition is not arbitrary; each set is defined by properties that are fundamental to its behavior under the Collatz map. This classification forms the bedrock upon which our entire state-based model is built.

2.1. Preliminary Definitions

We begin by formalizing the core concepts.

Definition 2.1 (The Collatz Function)

. The Collatz function is defined as:

Definition 2.2 (Collatz Sequence). For a starting integer , the Collatz sequence is the sequence where for all .

2.2. The Five Foundational Sets

We now partition

into five sets, summarized in

Table 1.

Definition 2.3 (The Cycle Set,

)

. The set consists of the numbers in the known terminal cycle:

Definition 2.4 (The Precursor Set,

)

. The Precursor set consists of all even multiples of 3:

Definition 2.5 (The Root Odd Multiple Set,

)

. The set consists of all odd multiples of 3:

Definition 2.6 (The Immediate Successor Set,

)

. The set consists of integers that are the direct result of applying the Collatz function to an element of :

Definition 2.7 (The Exclusion Set,

)

. The set consists of all other positive integers:

2.3. Completeness of the Partition

For this framework to be valid, every integer must belong to exactly one set.

Theorem 2.8 (Completeness of Partition). The sets form a partition of the positive integers .

Proof. We prove this by showing every belongs to at least one set (exhaustiveness) and to no more than one set (mutual exclusivity).

Exhaustiveness: Let . We follow a decision tree:

- 1.

Is ? If yes, then .

- 2.

-

If no, is ?

- 3.

If no to both above, does for some ? If yes, .

- 4.

If no to all of the above, then by definition, .

This decision tree covers all positive integers, so the union of the sets is .

Mutual Exclusivity: We show the sets are pairwise disjoint.

By definition of , it is disjoint from all other sets.

The sets and contain multiples of 3, while and do not (elements of are ). Thus, .

as one contains even numbers and the other odd.

as the smallest element of is 10.

All sets are pairwise disjoint. Therefore, the classification is a complete and unique partition. □

Remark 2.1.

The rigorous partitioning of is the crucial first step. It allows us to move from analyzing the behavior of infinite numbers to analyzing the transitions between a finite number of categories.

3. The Mechanics of the Funnel: Proving the Rules of Transition

Having defined the static geography of our system, we now establish its laws of physics. This section proves a series of lemmas that reveal a deterministic, one-way flow between the sets. We will see that numbers are systematically passed from an infinite past () into a core domain (), from which they can never return.

3.1. Finite Descent from the Initial Domain ()

Lemma 3.1 (Finite Transition). For any , there exists a finite integer such that .

Proof. Let

. By Definition 2.4,

x is an even multiple of 3. We can write

, where

and

m is an odd integer. Since

x is a multiple of 3,

m must also be a multiple of 3. Thus

. Applying the Collatz function

a times yields:

Since

, the sequence reaches

in exactly

a steps. □

3.2. The Irreversible Bridge ()

Lemma 3.2 (Single-Step Transition). For every , its successor is in .

Proof. Let . By Definition 2.5, x is odd. We apply the Collatz rule . The definition of the set (Definition 2.6) is precisely . Therefore, . □

3.3. Structural Confinement ()

Lemma 3.3 (Irreversibility of the Bridge). If , then for all , .

Proof. An element of must be divisible by 3. Let . By definition, . We show one application of cannot produce a multiple of 3.

Case 1: x is odd. . Since , , so . An integer congruent to 1 mod 3 cannot be in or .

Case 2: x is even. . Assume for contradiction that . This means for some integer k. This implies , which means . This contradicts our premise that .

Since is never a multiple of 3, and this property is preserved at each step, no future iterate can ever enter . □

3.4. The Absorbing Nature of the Cycle ()

Lemma 3.4 (Invariance of the Cycle Set). If , then .

Proof. By direct computation: , , and . □

4. Formalizing the Funnel: A Refined Finite State Machine

The structure and mechanics we have proven point to a highly organized system. We now formalize this system by constructing a Finite State Machine (FSM). We will first build an intuitive model that shows the general flow, and then refine it into a perfectly deterministic machine whose properties can be rigorously proven.

4.1. The 17-State FSM (Mod 9)

We first construct an FSM based on the state function from Definition 4.2. This model, based on modulo 9, is excellent for visualizing the overall funneling behavior of the system.

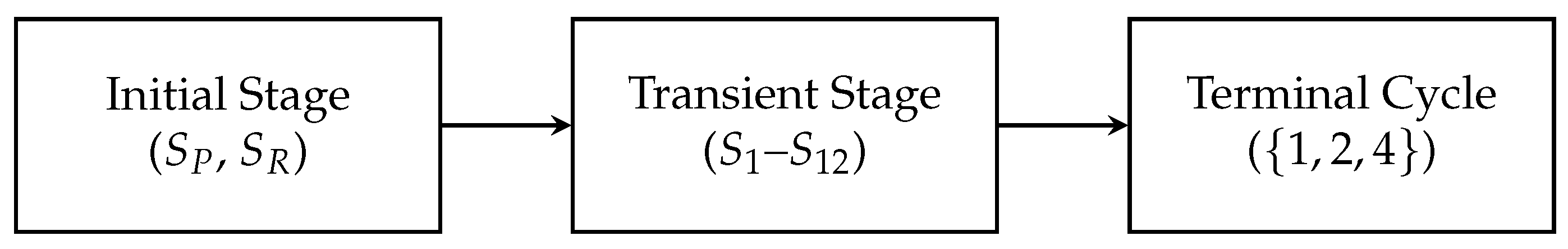

Definition 4.1 (The Three Stages). 1.

Initial Stage (): Corresponds to integers divisible by 3. Contains states (set ) and (set ).

-

2.

Transient Stage (): Corresponds to integers not divisible by 3 and not in . Contains 12 states, .

-

3.

Terminal Stage (): Corresponds to . Contains states .

Definition 4.2 (The State Function (mod 9)). For an integer , its state is determined by the triplet: . This function uniquely maps every such integer to one of the 12 transient states.

Lemma 4.3 (Confinement to the Power-of-Two Orbit). Every odd iterate in the transient stage has a residue modulo 9 belonging to the set .

Proof. Let o be an odd integer not divisible by 3. The next odd iterate is . Since , q cannot be divisible by 3. Its residue modulo 9 must therefore be in the set , which is precisely the set of residues of . □

Remark 4.1 (The Modular Carousel).

This confinement is critical. It shows that the seemingly random walk of odd numbers is, from a modular perspective, tightly constrained. Multiplication by 2 (or 5, its inverse) simply permutes the elements of this set, trapping all odd iterates in a modular carousel: .

Remark 4.2 (Why Modulo 9?).

The choice of modulo 9 is strategic. As proven in Lemma 4.3, it is the minimal modulus that reveals the fundamental confinement of the transient domain to the power-of-two orbit. This provides an intuitive and visually comprehensible map of the system’s overall funneling behavior.

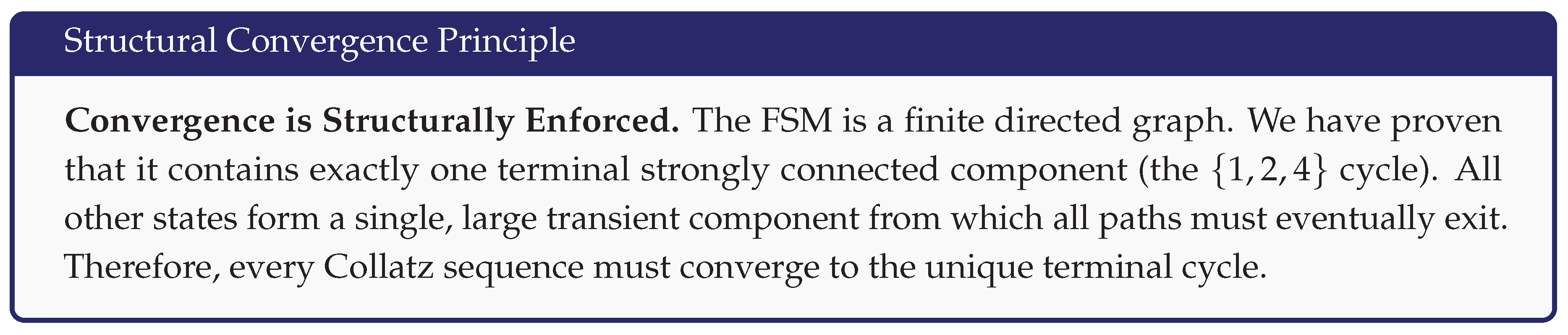

The state transitions are summarized in

Table 2 and visualized in

Figure 1. The rigorous justification for each transition is provided in the proof of Lemma 4.4 below.

4.2. State Transition Diagram of the 17-State FSM

Lemma 4.4 (Exhaustive State Transition Analysis). The transitions between the 12 transient states are deterministic.

Proof. We analyze each state by representing an integer x in its general form for that state and applying .

From : . . If m even, odd (). If m odd, even (). Next: .

From : . . , even, in . Next: .

From : . . If k odd, (). If k even, (). Next: .

From : . . , even, in . Next: .

From : . . If k even, even (). If k odd, odd (). Next: .

From : . . , even, in . Next: .

From : . . If k even, odd (). If k odd, even (). Next: .

From : . . , even, in . Next: .

From : . . If k even, even (). If k odd, odd (). Next: .

From : . . , even, in . Next: .

From : . . If , (). If even, even (). If k odd, odd (). Next: .

From : . . , even, in . Next: .

All transitions are deterministic and uniquely defined. □

4.3. Proving the Funnel’s Inescapable Properties

We now use this FSM transition analysis to prove the three crucial constraints on every Collatz trajectory.

4.3.1. The Unique Exit Path

Lemma 4.5 (The Unique Gateway State). State is the only state within the transient stage that has a direct transition to any state within the terminal cycle stage .

Proof. This follows directly from the exhaustive state transition analysis presented in Lemma 4.4. Reviewing the ’Next State(s)’ column for each of the 12 transient states ( through ), we observe:

States through and state transition only to other states within the transient stage .

State (representing integers , Even, ) has transitions to , , and . The transition to occurs specifically when , i.e., for the integer , where .

Therefore, is the unique state in the transient stage possessing a transition path leading directly into the terminal cycle stage . □

4.3.2. The Transient Stage as a Single SCC

Lemma 4.6 (Transient Stage as a Single SCC). The set of transient states forms a single Strongly Connected Component (SCC) under the Collatz state transitions.

Proof. To prove that forms a single SCC, we must show that for any ordered pair of states within , there exists a directed path from to . We establish this by demonstrating that all states can reach a central pivot state (), and that this pivot state can reach all other states.

Part 1: Universal Reachability to the Gateway (). Let be the set of states from which can be reached in at most k steps. We define and construct the sets recursively using the transition rules of Lemma 4.4:

(base case).

, since .

, since these states all have direct transitions to .

, since and , all of which are in .

, since these states all transition to states within .

The final set is . This exhaustive backward construction proves that every transient state has a finite directed path to .

Part 2: Universal Reachability from the Gateway (). We now show that has a path to every other state in . Let be the set of states reachable from in at most k steps.

.

From , transitions lead to . Thus, .

By exhaustive forward path tracing (as detailed in Lemma 4.4), we find that the set of reachable states expands with each step until .

This proves that a finite directed path exists from to every other state in .

Conclusion: For any pair of states in , there exists a path from to (by Part 1) and a path from to (by Part 2). Concatenating these paths establishes a path from to . Therefore, the set of transient states constitutes a single Strongly Connected Component. □

Remark 4.3.

The proof uses a standard pivot-based argument in graph theory: if all nodes in a set can reach and be reached from a common node (here, ), then the entire set is strongly connected. This satisfies the formal definition of an SCC: for any pair , there exists a directed path from to .

Remark 4.4 (Unique Exit via State S11).

Within the transient SCC , the only state with a direct transition to the terminal cycle is the gateway state . As shown in Lemma 4.4, this transition occurs only for the specific input , mapping . All other inputs to (where ) transition back into the transient SCC (to or ).

4.3.3. No Non-Trivial Cycles

We have established that the 12 transient states form a single, large Strongly Connected Component (Lemma 4.6). The final step is to prove that this component is truly transient—that is, that no trajectory can loop indefinitely within it. The following lemma proves that the existence of a non-trivial Collatz cycle is structurally incompatible with the FSM’s topology, as it would require a "sink component" where none can exist.

Lemma 4.7 (Acyclicity of the Transient Stage). No non-trivial Collatz cycle can exist within the transient stage .

Proof. Assume for contradiction that a non-trivial cycle, L, exists.

- (i)

By Lemma 3.3, this cycle L cannot contain any multiples of 3. Therefore, all integers and states in L must be contained entirely within the transient stage .

- (ii)

By definition, such a cycle L would form a sink component (a terminal SCC) in the state graph. This means that no state in L could have a directed path to any state outside of L.

- (iii)

This leads to a direct contradiction. The proof of Lemma 4.6 (Part 1) demonstrated via exhaustive backward construction that every state in has a finite, directed path to the gateway state .

- (iv)

By Lemma 4.5, has a valid exit transition to , which is outside .

Since every state in has a path to an exit, no subset of can form a sink component. Therefore, no non-trivial cycle L can exist. □

Remark 4.5 (Exit Paths and Acyclicity in a Strongly Connected Component).

The logic of Lemma 4.7 rests on a fundamental principle of finite directed graphs: a strongly connected component (SCC) cannot simultaneously contain an exit path—a transition that irreversibly leaves the component—and an internal sink component, such as a sub-cycle with no exit.

By definition, every node in an SCC must be reachable from every other node. If the SCC contains a node with an irreversible transition to another component (such as ), then all nodes in the SCC must have a path to that exit. This structurally prohibits the existence of any internal subset of nodes that does not lead to the exit, thereby ruling out internal sinks or non-trivial terminal cycles.

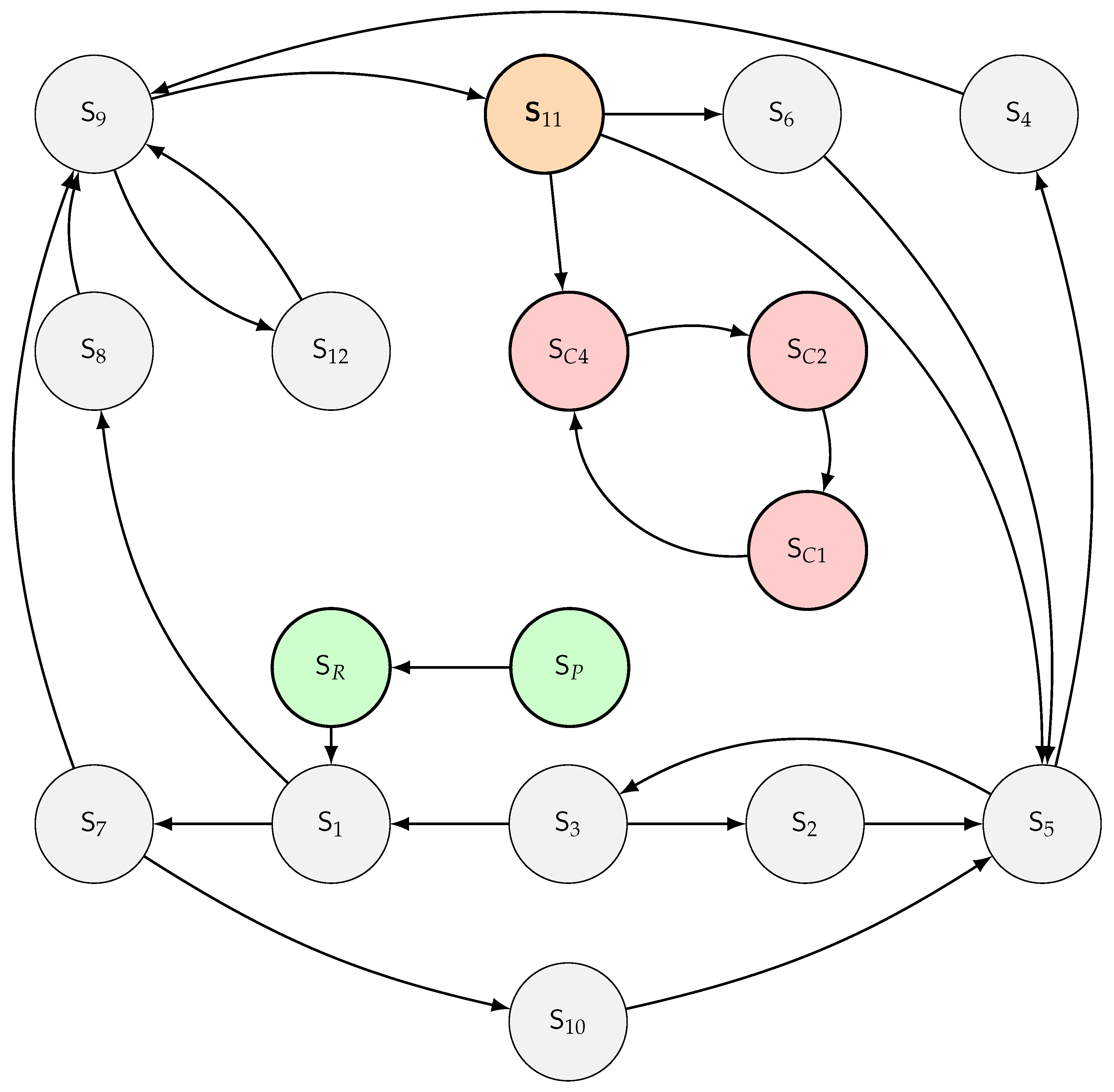

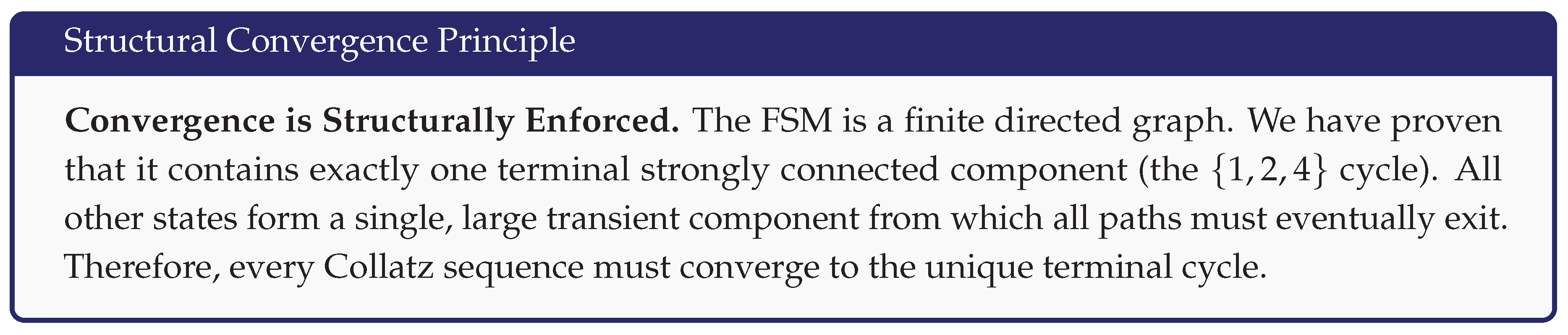

4.4. Global Structure via Graph Condensation

To synthesize the FSM’s topology in purely graph-theoretic terms, we condense its 17 states into three components based on strong connectivity. This reveals a funnel-shaped DAG structure that guarantees all trajectories ultimately terminate in the terminal cycle.

Lemma 4.8 (Condensation Structure of the FSM). The condensation graph of the 17-state FSM is a directed acyclic graph (DAG) with exactly three conceptual components: an initial component, a single transient strongly connected component, and a terminal absorbing cycle.

Proof. Let be the directed graph induced by the FSM. We identify three fundamental components based on their graph-theoretic properties:

: An acyclic entry component representing integers divisible by 3.

: A single strongly connected component representing the core funnel (as proven in Lemma 4.6).

: A closed cycle (and thus an SCC) corresponding to the terminal set (Lemma 3.4).

The transitions between these components follow the one-way structure:

Since no transitions leave , it acts as the unique sink component of the entire system. Furthermore, Lemma 4.7 proves that contains no internal sink components (i.e., no non-trivial cycles). Because is a transient component with a proven exit path to (Lemma 4.5), all trajectories that enter it must eventually take that exit.

Thus, the condensation graph of the FSM is a DAG that funnels all trajectories from the initial stage into the unique terminal sink. □

Figure 2.

Condensation graph of the FSM: a DAG with three components representing the initial, transient, and terminal stages.

Figure 2.

Condensation graph of the FSM: a DAG with three components representing the initial, transient, and terminal stages.

5. The Inevitable Convergence: Structural Proof of the Collatz Conjecture

With the state space of the Collatz map fully partitioned and its finite transition structure formalized as a directed graph, convergence follows as a direct consequence of that structure.

Theorem 5.1 (Structural Proof of the Collatz Conjecture). Every Collatz sequence starting from any positive integer eventually enters the terminal cycle .

Proof. The proof synthesizes the number-theoretic partition, the finite-state dynamics, and the graph-theoretic structure of the FSM:

-

Step 1.

Total State Coverage. By Theorem 2.8, every positive integer belongs to exactly one of the 17 states of the FSM. Thus, every Collatz sequence corresponds to a deterministic path through a finite state system.

-

Step 2.

Deterministic Transitions. By Lemma 4.4, the transition rules between states are deterministic. The evolution of any sequence is therefore a deterministic walk on a finite graph.

-

Step 3.

Absence of Non-Trivial Cycles. The existence of a non-trivial cycle (a loop other than ) is structurally impossible. As proven in Lemma 4.7, no subset of the transient states can form a "sink component" because all transient states have a directed path to the gateway state , which exits the transient stage.

-

Step 4.

Inevitable Convergence to Terminal Cycle. Since every sequence is a walk on a finite graph (Step 1) and non-trivial cycles are impossible (Step 3), the only possible infinite behavior is to enter a terminal SCC. By Lemma 3.4, the cycle () is an absorbing component. As all other states are transient (per Lemmas 3.1, 3.2, 4.5, and 4.7), all paths must eventually lead to and be absorbed by this unique terminal cycle.

It follows that the Collatz Conjecture is true. □

6. Supporting Evidence and Context

6.1. Computational Verification

To empirically test the theoretical claims of our 17-state finite state machine (FSM) - including state assignments, transition rules, and the unique gateway mechanism - we implemented a computational verification over a large numerical range. The goal was to confirm that Collatz sequences evolve exactly as predicted by the FSM structure.

A Python script (verify_collatz_fsm.py) was written using the multiprocessing module (with 8 workers) to test all integers from 1 up to . For each starting value n, the script traced its Collatz sequence and performed the following checks at every step until reaching the cycle set :

Initial state classification: Confirmed that each n is correctly mapped to one of the 17 FSM states via the getState function.

Deterministic transition verification: Ensured that each observed transition conformed exactly to the FSM’s transition rules (Lemma 4.4).

Gateway consistency: Verified that any transition to 4 (i.e., to ) occurred only from either (in ) or (in ), as required by the FSM structure.

State coverage: Ensured that no number encountered during the sequence evaluation mapped to an undefined or invalid state.

Step count: Recorded the number of steps required for each sequence to reach 1.

A summary of the results is shown in

Table 3. All checks passed without error, and no violations were detected.

These results confirm the empirical soundness of the finite state model over all tested inputs. Every transition was deterministic, every number remained confined within the FSM structure, and the unique gateway mechanism through behaved exactly as predicted. Notably, the number achieved the maximum stopping time within this range, consistent with prior computational records.

This large-scale verification strongly reinforces the validity of the FSM framework and its predictive power in modeling Collatz dynamics.

6.2. Empirical Evidence from Literature

Decades of large-scale computational searches have verified the conjecture up to enormous numbers (e.g.,

) [

2]. Our proof provides the theoretical explanation for these empirical results: divergent trajectories and non-trivial cycles are not just elusive, they are structurally forbidden.

6.3. Comparison with Previous Approaches

Unlike probabilistic models, which suggest convergence based on expected statistical behavior, the proof presented here is entirely deterministic, grounded in the rigorous graph-theoretic properties of a Finite State Machine (FSM) derived from the Collatz function itself. In contrast to purely computational verifications that confirm the conjecture only up to large numerical bounds, this framework provides a general, all-encompassing argument valid for every positive integer. Its novelty lies in synthesizing integer partitioning and modular arithmetic to construct a complete, finite FSM that models all possible Collatz trajectories. By analyzing the structural invariants of this FSM—specifically, the existence of a single transient Strongly Connected Component and a unique exit path to the terminal sink—the proof demonstrates that convergence to the cycle is not empirical or probabilistic, but a mathematical necessity imposed by the topology of the Collatz state graph.

7. Conclusion

We have presented a deterministic proof of the Collatz Conjecture by formalizing its dynamics within a rigorously defined 17-state Finite State Machine (FSM). This framework transcends probabilistic reasoning and large-scale computational verification, demonstrating instead that the conjecture’s truth arises from a deterministic structural funnel inherent in the arithmetic rules of the Collatz map.

Through exhaustive state transition analysis and graph-theoretic reasoning, we established the following key structural properties:

- (1)

The set of all positive integers can be partitioned such that their behavior under the Collatz map is completely represented by the 17-state FSM.

- (2)

The FSM’s transient states—those outside the terminal cycle —form a single Strongly Connected Component (SCC).

- (3)

This transient SCC possesses a unique exit transition leading irreversibly to the terminal states corresponding to the cycle .

These structural invariants—a finite directed graph containing one transient SCC with a single irreversible exit to an absorbing sink—mathematically necessitate that any trajectory, represented as a path through the FSM, must eventually traverse this exit and converge to the terminal cycle in a finite number of steps.

This result underscores the power of transforming problems defined over infinite domains (such as the positive integers) into finite, structurally complete models. By revealing the underlying finite-state topology of the Collatz map, this proof establishes that convergence is not a numerical coincidence or empirical regularity, but a structural necessity—a manifestation of hidden order within a system long regarded as chaotic.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges his wife, Ajifa Atuluku, for her steadfast encouragement throughout the process of drafting this proof. The author also acknowledges the use of AI-assisted tools (Google Gemini AI and ChatGPT) for formatting assistance and language clarity. All mathematical content and original ideas in this manuscript were developed independently by the author.

Data Availability Statement

The Python script used to generate the computational verification data presented in this proof is available online at the following open code repository:

[Link to Code Repository].

References

- J. C. Lagarias, "The 3x + 1 problem and its generalizations," American Mathematical Monthly, vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 3–23, 1985. [CrossRef]

- T. Oliveira e Silva, "Empirical verification of the 3x+1 and related conjectures," The Ultimate Challenge: The 3x+1 Problem, J. C. Lagarias, Ed. Providence, RI: Amer. Math. Soc., 2010, pp. 189–207.

- T. Tao, "Almost all orbits of the Collatz map attain almost bounded values," Forum of Mathematics, Pi, vol. 10, E2, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).