1. Introduction

Pertussis, also known as whooping cough, is a respiratory infection caused by

Bordetella pertussis [

1]. The hallmark of classic pertussis is a prolonged cough that can persist for several weeks. The illness is characterized by intense bouts of coughing, known as paroxysms, which often conclude with a distinctive gasping sound called a "whoop" [

2].

Pertussis is a vaccine-preventable disease, and introducing the pertussis vaccine in the 20th century has significantly reduced the number of pertussis cases and deaths in children [

3]. Pertussis continues to be a primary public health concern, with significant rates of illness and death [

4]. According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about one-third of infants with pertussis require hospitalization, and 1% of these hospitalized cases result in death [

5]. Pertussis remains one of the leading causes of illness and mortality among infants [

6]. Whooping cough affects individuals of all ages, but it is most severe in infants, who have the highest age-specific incidence of the disease and account for nearly all hospitalizations and deaths related to pertussis [

7].

Globally, pertussis affects millions of individuals annually, with children bearing the brunt of the disease burden [

8]. The World Health Organization estimates that pertussis causes over 160.000 deaths annually, primarily in infants under six months of age who are not fully vaccinated [

9]. Severe complications, including pneumonia, encephalopathy, and even death, underscore the disease's high stakes in pediatric health. Such outcomes are particularly concerning in resource-limited settings, where access to vaccines, diagnostic tools, and medical care may be constrained [

10].

Despite decades of extensive immunization campaigns, whooping cough seriously threatens world health [

11]. The highly infectious disease can cause severe respiratory difficulties, especially in newborns and young children. Periodic illness outbreaks in different communities highlight the intricacy of its epidemiology and the shortcomings of existing prevention interventions, even though vaccination programs have significantly decreased pertussis-related morbidity and death [

12].

Even though acellular vaccinations (aP) have fewer side effects than whole-cell vaccines (wP), concerns have been raised over their long-term effectiveness and the necessity of booster shots due to their shorter lifetime of protection [

13]. Furthermore, discussions about vaccination methods, such as the timing and makeup of immunization regimens, have been triggered by the impact of the pertussis comeback in highly vaccinated populations [

14].

The persistence of pertussis as a public health threat is multifaceted [

15,

16]. Waning immunity after vaccination or natural infection, incomplete vaccine coverage, and the emergence of

Bordetella pertussis strains with reduced vaccine sensitivity contribute to the ongoing burden of disease [

17]. Moreover, diagnostic challenges, including nonspecific early symptoms and limited access to advanced diagnostic tools, can delay treatment and containment, exacerbating its spread. [

18]. For this reason, pertussis is also known as "the 100-day cough." [

19]. These factors highlight the need for continued research to refine preventive and management strategies for pertussis, especially in pediatric populations.

Pertussis typically begins with symptoms resembling a mild upper respiratory infection [

20]. A mild cough progressively intensifies within 1 to 2 weeks, becoming paroxysmal. These coughing fits increase in frequency and severity before gradually subsiding over several weeks or longer [

21]. Paroxysms are characterized by rapid coughs without inhalation, followed by the characteristic "whoop," which is a desperate effort to breathe through a swollen glottis [

22]. During a paroxysm, the patient may turn cyanotic, and vomiting often follows the intense coughing. Multiple paroxysms can occur in quick succession, leaving the patient exhausted. Also, they tend to be more severe at night. Between these episodes, the patient generally appears normal [

23]. While fever is uncommon in pertussis, the condition is often associated with elevated levels of neutrophils, C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin, indicating the possible presence of concurrent bacterial infections [

24]. Even after the illness resolves, the cough can persist for many weeks, and intercurrent viral infections may provoke a recurrence of the paroxysms [

25,

26,

27].

Leukocytosis is a hallmark of pertussis [

28]. Studies have shown that children with severe pertussis exhibit significantly higher white blood cell counts than those with milder forms of the disease, with particularly elevated levels observed in fatal cases [

29]. The poor deformability of these white blood cells leads to obstruction in the narrowed alveolar capillary beds, resulting in embolism due to the formation of leukocyte clumps [

30]. This embolism causes hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension, which can impair cardiac function and lead to heart failure in severe cases [

31,

32]. Severe hyperleukocytosis is recognized as an independent risk factor for malignant pertussis, a life-threatening form of the disease [

33].

Given the rise in whooping cough incidence cases in the EU/EEA, 112 cases of whooping cough were recorded in Romania in the first 4 months of 2024, representing a significant increase compared to 16 cases reported in 2023, respectively 93 cases on average in 5 pre-pandemic years (2015-2019) [

34]. The cases belong to 22 Romanian counties, while the most affected age group was 0-4 years (33% of the cases were infants, of whom 89% were eligible for vaccination) [

35]. Two months later, this number dramatically increased to 417; two deaths were recorded, both in infants (in Bucharest and Iasi County) [

36]. In this context, the present study aims to fill critical gaps in understanding pertussis's clinical and epidemiological aspects in pediatric populations. By integrating detailed analyses of patient presentations, disease outcomes, and vaccination statuses alongside a comprehensive literature review, this work seeks to (i) highlight the complex interplay between vaccination, immunity, and disease resurgence, (ii) explore the unique vulnerabilities of children to pertussis, including age-specific risks and outcomes, and (iii) address diagnostic and management challenges, particularly in resource-limited contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective clinical study was performed on 38 pediatric patients diagnosed with Bordetella pertussis infection from Southeast Romania. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Constanta County Clinical Emergency Hospital "St. Apostle Andrew" Document number 08, approved on March 05, 2025. The pediatric patients were children aged <1 year to 13 years, all of whom were hospitalized with pertussis in the Pediatric Departments of the hospital between January 1, 2024, and September 30, 2024.

2.1. Data Collection

Data were extracted from hospital databases and medical charts, including demographic details (age and gender), clinical features, length of hospital stay, and complications. Clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging techniques confirmed the diagnosis of B. pertussis infection.

2.2. Molecular Diagnostics

The CFX96 Real-Time PCR (qPCR) Detection System by Bio-Rad was used to detect and quantify Bordetella pertussis DNA. This system allows high-performance real-time PCR and is widely used in molecular diagnostics. It features the following specifications:

96-well capacity for high-throughput experiments.

6-target detection allows multiplex PCR assays for simultaneous detection of different targets.

Fast and precise thermal cycling using a Peltier-based heating/cooling system.

Optical detection system with high-intensity LEDs and a precise CCD camera for sensitive fluorescence detection.

User-friendly software: CFX Maestro software was used for easy data analysis, including gene expression analysis, melt curve analysis, and relative quantification.

The basic protocol for qPCR includes the following steps:

Sample Preparation: Extraction of DNA from clinical samples.

PCR Setup: A reaction mix containing template DNA, forward and reverse primers, fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green), and qPCR master mix was prepared.

Thermal Cycling Program: The thermal cycling protocol typically included initial denaturation at 95°C, followed by cycles of denaturation (95°C), annealing (55-65°C), and extension (72°C).

Data Analysis: CFX Maestro software was employed to analyze amplification curves and calculate the Ct (threshold cycle) values for quantification.

2.3. Imaging and Laboratory Tests

In addition to qPCR, diagnostic imaging (chest X-ray) was performed to evaluate pulmonary involvement. Laboratory tests included serological assays and culture by standard diagnostic practices for pertussis in children.

Typical reference values for the laboratory tests and imaging criteria for interpreting chest X-rays were used based on established local guidelines for pediatric patients.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics analyzed data, and clinical patterns, complications, and outcomes were identified to assess the burden and severity of

B. pertussis infection in the pediatric population. The variable parameters are displayed as absolute frequencies (number,

n) and relative frequencies (percentage) [

37]. The extensive data analysis involved other different tools of XLSTAT Life Sciences v 2024.3.0. 1423 by Lumivero (Denver, CO, USA): ANOVA single factor and correlations between variable parameters [

38]. Statistical significance was established at p < 0.05 [

39].

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Baseline Data of the Pediatric Patients

The retrospective study was performed on 38 pediatric patients, 19/38 (50%) boys and 19/38 (50%) girls, 17/38 (44.74%) with rural residence, and 21/38 (55.26%) from urban zones. Statistically significant differences are reported between boys and girls of age groups <1-3 and 4-13 years,

B. pertussis vaccination, and clinical laboratory diagnosis method (

p < 0.05). Data are recorded in

Table 1.

Most pediatric patients (31/38, 81.58%) have up to 3 years, while only 7/38 (18.42%) have 9-13 years (

p<0.05,

Table 1). Only 7/38 (18.42%) received the

B. pertussis vaccine, while 31/38 (81.58%) were not vaccinated (

p<0.05). No pediatric patients were protected through a maternal vaccine. Serological diagnosis (ELISA) of

B. pertussis was performed for 6/38 (15.79%) patients, while 32/38 (84.21%) were diagnosed through Real-time PCR (qPCR),

p<0.05 (

Table 1).

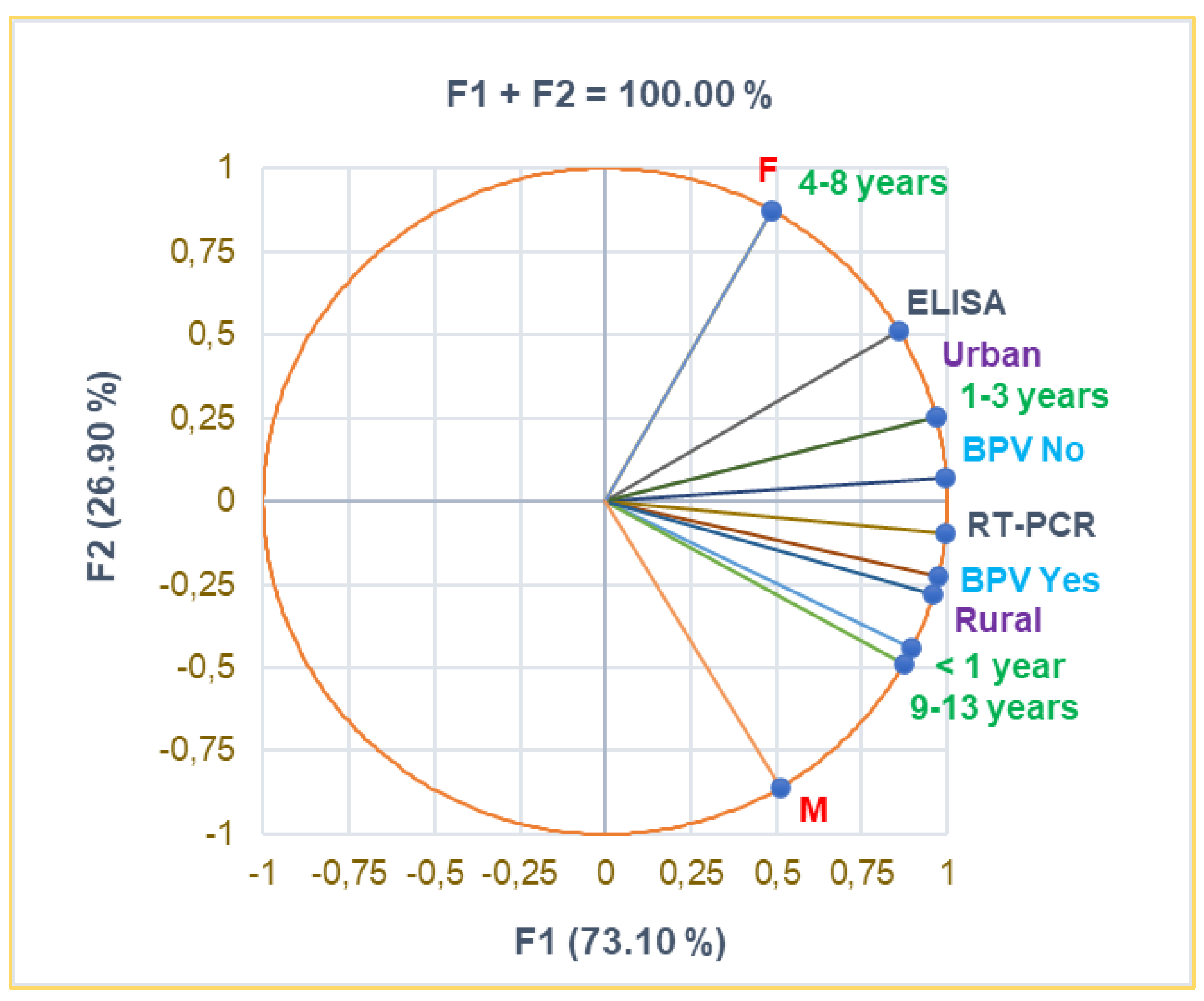

The correlation Matrix and

Figure 1 evidence a substantial correlation between rural residence and BPV Yes, urban residence and 1-3 years age group, and female patients and 4-8 years (r = 0.999,

p<0.05). The 1-3 age group highly correlates with BPV No, qPCR, and Elisa diagnosis (r = 0.939 - 0.983,

p>0.05). BPV Yes strongly correlates with age groups <1 year and 9-13 years and qPCR diagnosis. The rural zone is moderately associated with boys and urban residence with girls (r = 0.731, r = 0.693,

p<0.05).

3.2. Associated Pathogens and Clinical Manifestations

B. pertussis was associated with several viral pathogens in pediatric patients. Enterovirus-human-rhinovirus (EV-HRV) was detected in 12/38 patients (31.58%), Coronavirus SARS-CoV2 in 5/38 (13.16%), and Human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV-3) in 2/38 (5.26%),

p<0.05 (

Table 2). Human adenovirus (HAdVs), Measles virus (MV), and Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) were each detected in 1/38 (2.63%) pediatric patients. Other pathogens identified in pediatric patients were

Streptococcus pneumoniae (7/38 patients, 18.42%),

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and

Pneumocystis jirovecii (1/38 patients, 2.63%),

p<0.05 (

Table 2).

Cough was the main symptom identified in all pediatric patients (38/38, 100%). 16/38 patients (42.11%) had a fever; high fever (>39

o C) was detected in 3/38 ones (7.89%), p<0.05 (

Table 2). 23/28 patients (60.53%) had acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS, respiratory failure), 14/38 (36.84%) had rhinorrhea, and 7/38 (18.42%) had Oxygen desaturation (O2 DS), p<0.05. Other symptoms include emesis (7/38, 18.42%) and rash (1/38, 2.63%), p<0.05 (

Table 2).

Around 36/38 patients (94.74%) claimed respiratory symptoms several days before presentation in ECU (RSB), while only 2/38 (5.26%) did not have them, p<0.05 (

Table 2). 24/38 patients (63.16%) manifested respiratory symptoms 4-14 days before, while 7/38 (18.42%) and 5/38 (13.16%) claimed them 1-3 days and respectively over 20 days before admission, p<0.05 (

Table 2).

Most pathogens were co-detected in pediatric patients with respiratory symptoms 4-9 days before presentation in ECU (12/38, 31.58%). Thus, S. pneumoniae was co-detected in 6/12 patients (50%), EV-HRV and SARS-CoV2 were each co-detected in 3/12 patients (25%), while HPIV-3, HAdVs, M. pneumoniae, and P. jirovecii in 1/12 (8.33%). EV-HRV and MV were co-detected in 4/5 children (80%) with respiratory symptoms 20 days before admission in the pediatric department. Other pathogens (HPIV-3, SARS-CoV2, RSV, and S. pneumoniae) were co-detected in 5/7 (71.43%) patients with respiratory syndrome 1-3 days before, and in only 3/12 (25%) ones with 10-14 days (EV-HRV).

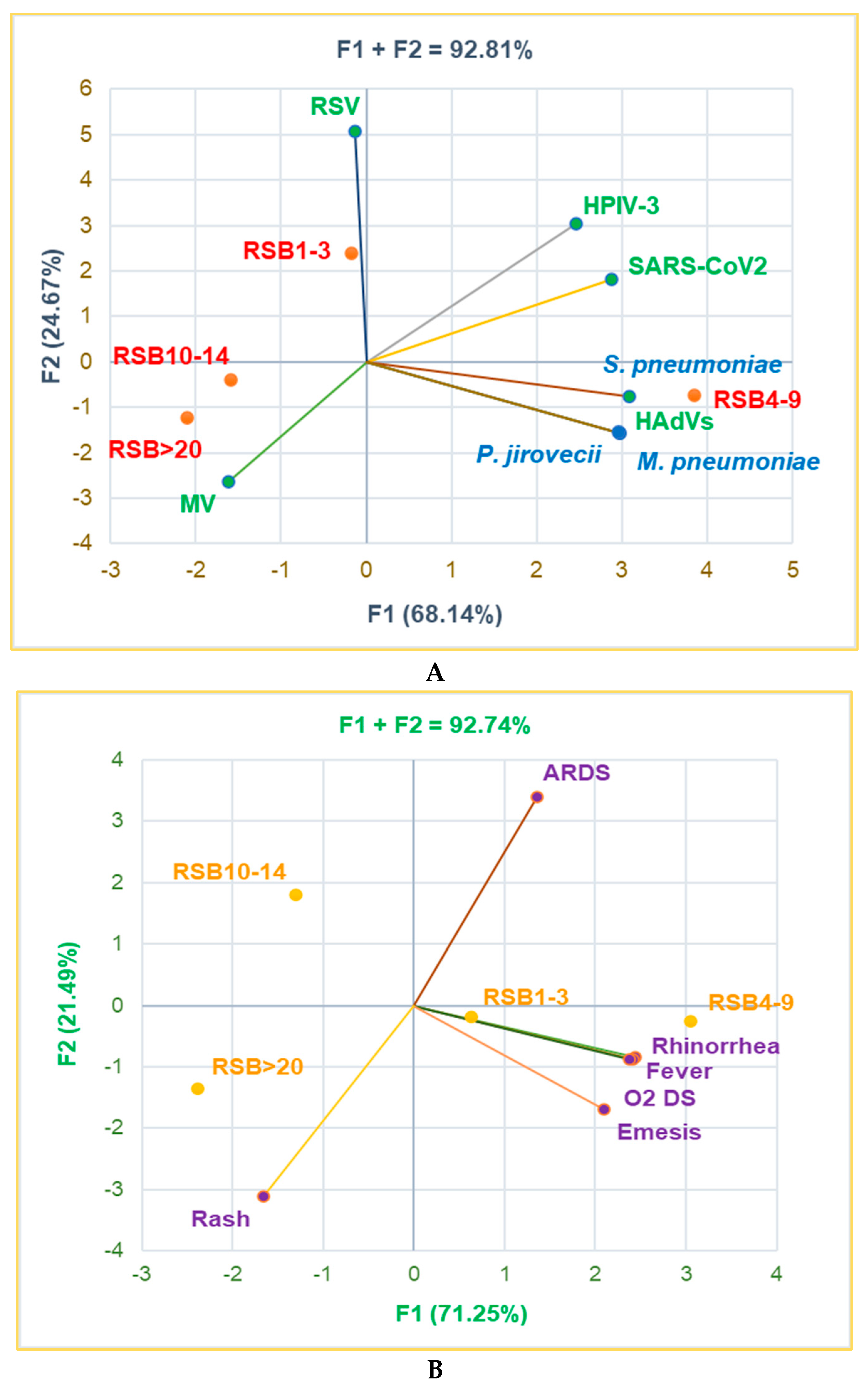

The correlation matrix and

Figure 2A report a substantial correlation between RSB>20 and MV, RSB4-9 and HAdVS,

S. pneumoniae, M. pneumoniae, and

P. jirovecii, and RSB1-3 and RSV (r = 0.986 – 0.999,

p<0.05).

RSB>20 significantly correlates with rash and RSB4-9 with emesis (r = 0.999, r = 0.962,

p<0.05,

Figure 2B). Moreover, rhinorrhea is strongly associated with O2 DS and fever (r = 0.971 – 0.997,

p<0.05,

Figure 2B).

Figure 2C shows that MV substantially correlates with rash, emesis with HAdVs,

S.

pneumoniae, M. pneumoniae and

P. jirovencii, Rhinorheea, and O2 DS with SARS-CoV2 and HPIV-3, and fever with SARS-CoV2 (r = 0.962 – 0.999,

p<0.05).

3.3. Clinical Laboratory and Radiological Investigations

The corresponding data are registered in

Table 3.

Eighteen children (18/38, 47.37%) had WBCs in the normal range, while the same number had WBCs increased (20-100 x 10

3). Only 2/38 (5.26%) had WBCs > 100 x 10

3. Both deceased patients had WBCs > 20 x 10

3; the other 9/38 children (74%) were transferred to another healthcare unit (

p<0.05,

Table 3). Of 8/38 pediatric patients with Lym cells ≤ 40%, 2/38 were deceased, and one was transferred (

p<0.05,

Table 3). PBS indicated significant changes in blood cells in 7/38 children (18.42%); 1/7 were deceased, and 5/7 were transferred (p<0.05). Only 1/7 remained hospitalized for clinical cure.

Six patients (6/38, 15.79%) had substantially high CRP levels (11 - >100 mg/dL); 2/6 (33%) were deceased, and 2/6 (33%) were transferred during the first 8 days of hospitalization (

Table 3).

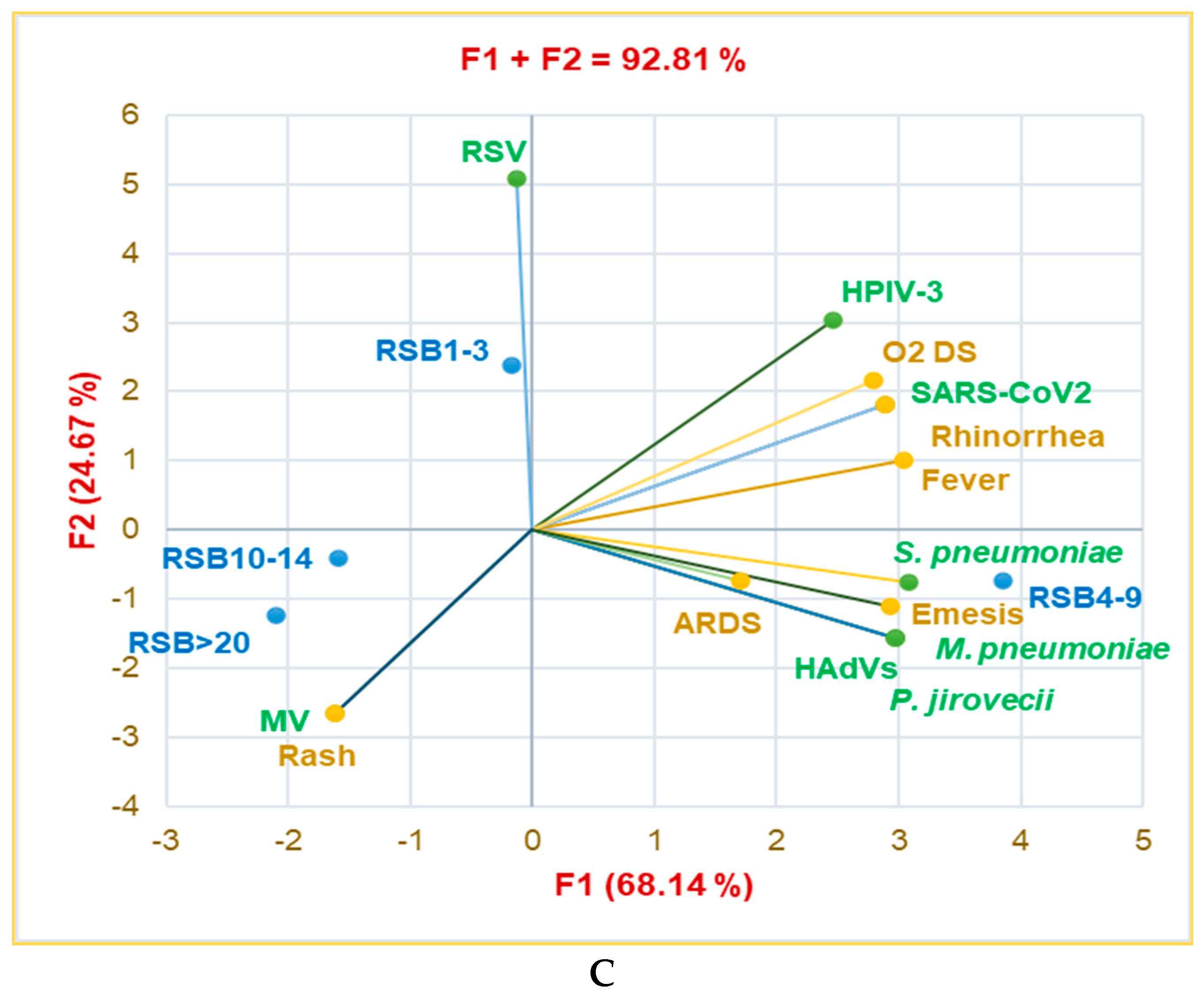

Thirty patients (30/38, 78.95%) had Chest X-ray exams positive; seven different results were obtained, noted C-X-ray 1-7: C-X-ray 1 -Accentuated interstitial pattern below the hilum bilaterally; C-X-ray 2 – Alveolar Opacities Around and Below the Right Hilum; C-X-ray 3 - Bilateral pulmonary infiltrate; C-X-ray 4 - Blurring of the right basal pulmonary field: C-X-ray 5 - Congestive Pulmonary Hila, Microalveolar and Reticular Opacities Around and Below the Hilum Bilaterally; C-X-ray 6 - Enlarged Congestive Hila, Confluent Alveolar Opacities Around the Left Hilum and Below the Hilum Bilaterally; C-X-ray 7 - Right pulmonary consolidation process; C-X-ray 8 - Widespread, homogeneous opacities of medium intensity, with blurred margins, showing air bronchograms, located in the upper third of both lung fields and left retrocardiac area—indicative of pulmonary infiltrates (

Figure 3).

Around 23/38 (60.53%) had a bilaterally accentuated interstitial pattern below the hilum (C-X-ray 1); similar numbers (1/38, 2.63%) had C-X-ray 2-8. 4 children (4/38, 10.53% had no Chest X-ray exam, and other 4/38 had a normal chest image (

Figure 3A).

The patients with C-X-ray 1 (62.50%), 2 (12.50%), and 7 (12.50%) had clinical cures; those with C-X-ray 1 (66.67%), 4, 5, 6 (each 8.33%) were transferred; deceased ones had C-X-ray 3 and 8 (

Figure 3B-D).

Four children had complications: Bilateral apical-lateral-basal Pneumothorax, Pulmonary condensation process in the lower 1/3 of the right pulmonary field, Confluent alveolar opacities, and interstitial peri- and hylo-basal bilateral enlarged congestive hilar regions, aspiration pneumonia, kidney failure, paroxysmal manifestations, and anasarca: two patients died, and one was transferred (

Table 3). Sixteen patients (16/38, 42.11%) had HD=6-10 days, while 12/38 (31.58%) were moved in the first 1-8 days (

p<0.05). 2/38 (5.26%) had >10 HD, 4/38 (10.53%) had 2-5 days, and the other 4/38 were not hospitalized.

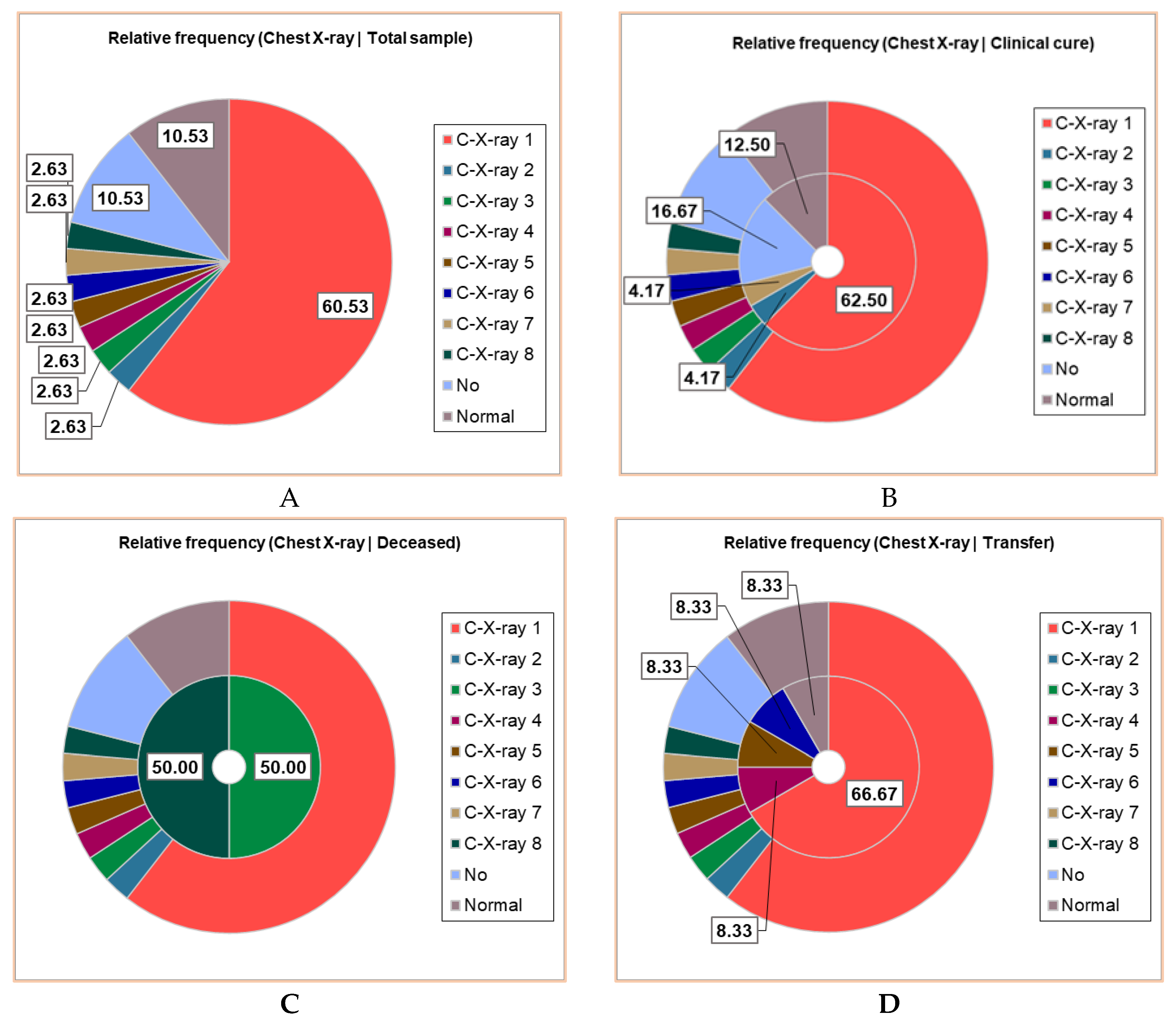

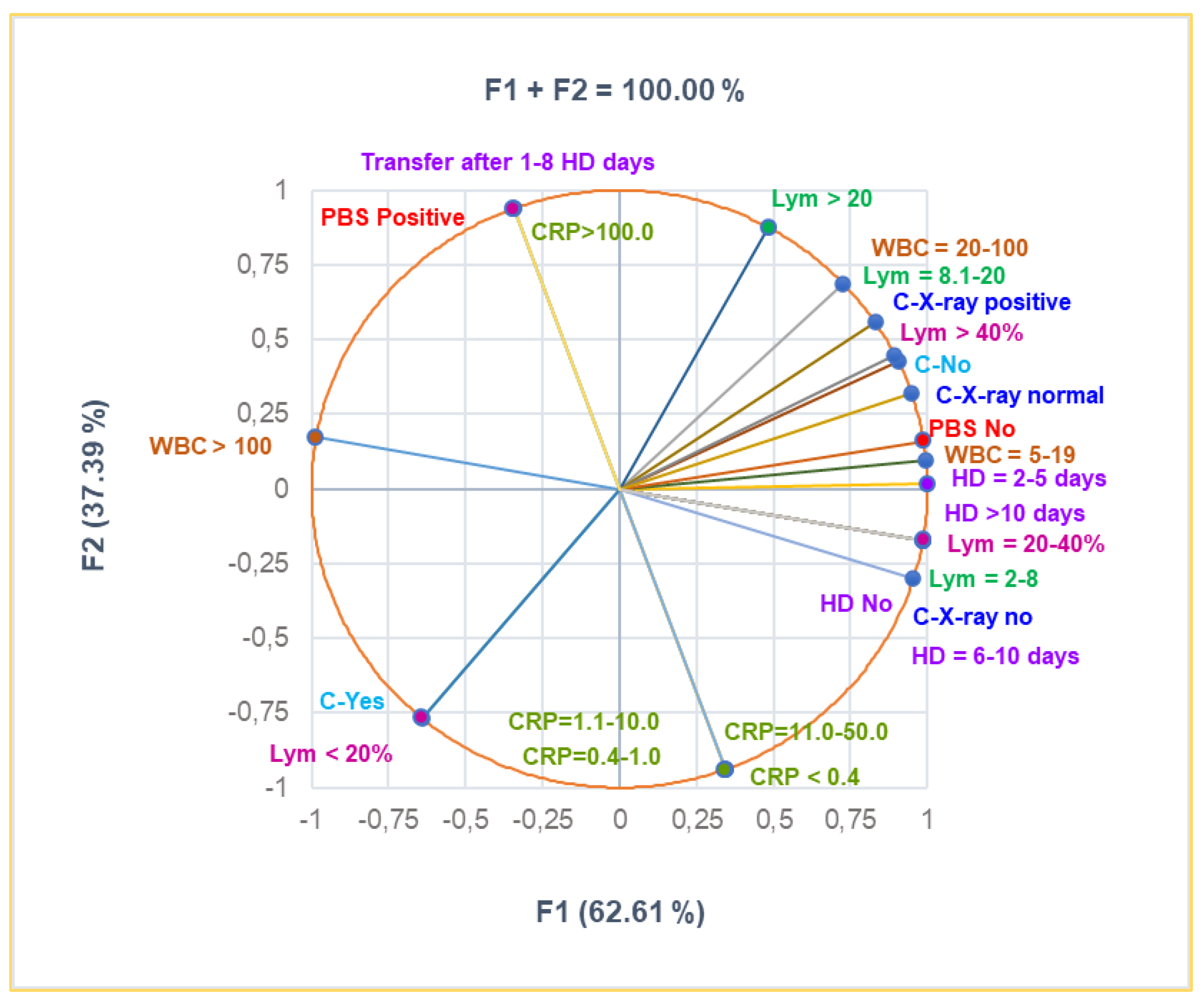

The correlation matrix and

Figure 4 show that Lym<20% substantially correlates with C-Yes, Lym>40% with C-X-ray positive, PBS positive with CRP>100mg/dL, PBS-no with C-X-Ray normal and C-X-ray no with HD No and HD = 3-5 (r = 0.998 – 0.999,

p<0.05). C-No highly correlates with HD-No and HD=3.5 (r = 0.878,

p>0.05), while CRP>100mg/dL significantly correlates with transfer after 1-8 days (r = 0.999,

p<0.05).

3.4. Treatment and Evolution

Antimicrobial treatment involves antibacterials and antivirals. The antibacterial treatment administered in hospitalized pediatric patients includes macrolides (Azithromycin and Clarithromycin) and beta-lactams (Amoxicillin and Ceftriaxone). The administration route, dosage per dose and day, and treatment duration differ by antibiotic type. Macrolides were administered orally -Azithromycin (10 mg/kg, maximum 500 mg, 3- 5 days) and Clarithromycin (7.5 mg/kg/dose twice daily (maximum 500 mg per dose)). From beta-lactams, Ceftriaxone was administered intravenous (IV) 50–100 mg/kg/day (maximum 2 g/day) in one or two divided doses, 7-10 days, and Amoxicillin orally (20–40 mg/kg/day in two or three divided doses (maximum 500 mg/dose)).

The antiviral therapy was used for coinfections with other viral pathogens, such as Remdesivir for cases involving SARS-CoV-2 or other respiratory viruses, based on clinical indication: Remdesivir IV (loading dose: 5 mg/kg on day 1 (maximum 200 mg), maintenance dose: 2.5 mg/kg/day (maximum 100 mg) from day 2, 5–10 days, depending on the clinical response).

In the present study, 26/38 (68.42%) received macrolides: Azithromycin (21/38, 55.26%) and Clarithromycin (5/38, 13.16%),

p<0.05. 10/38 were treated with beta-lactams: Ceftriaxone (8/38, 21.05%) and Amoxicillin (2/38, 5.26%),

p<0.05 (

Table 4). Two children had Remdesivir (2/38, 5.26%).

Of the pediatric patients, 7/38 (18.42%) needed intensive care in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU,

Table 4).

In the studied pediatric group, 37/38 patients received anti-inflammatory steroids: Dexamethasone (Dex, 21/38, 55.26%) and Hydrocortisone hemisuccinate (HHC, 14/38, 36.84%), while 31/38 (81.58%) received nebulized Adrenaline, (

p<0.05,

Table 4). Furosemide was administered to 2/38 children (5.26%), while only 1/38 (2.63%) received Aminophylline, Epinephrine, Norepinephrine, Mannitol, and Albumin.

Oxygen therapy was necessary for 22/38 patients: Low-flow nasal cannula O2 therapy (LFNCO2, 18/38, 47.37%) and High-flow nasal cannula O2 therapy (HFNCO2, 4/38, 10,53%),

p<0.05. For 3/38 children (7.89%), nasogastric intubation was necessary, 2/38 (5.26%) received mechanical ventilation and blood transfusion, and 1/38 (2.63%) were supposed to have bilateral pleurotomy (

p<0.05,

Table 4).

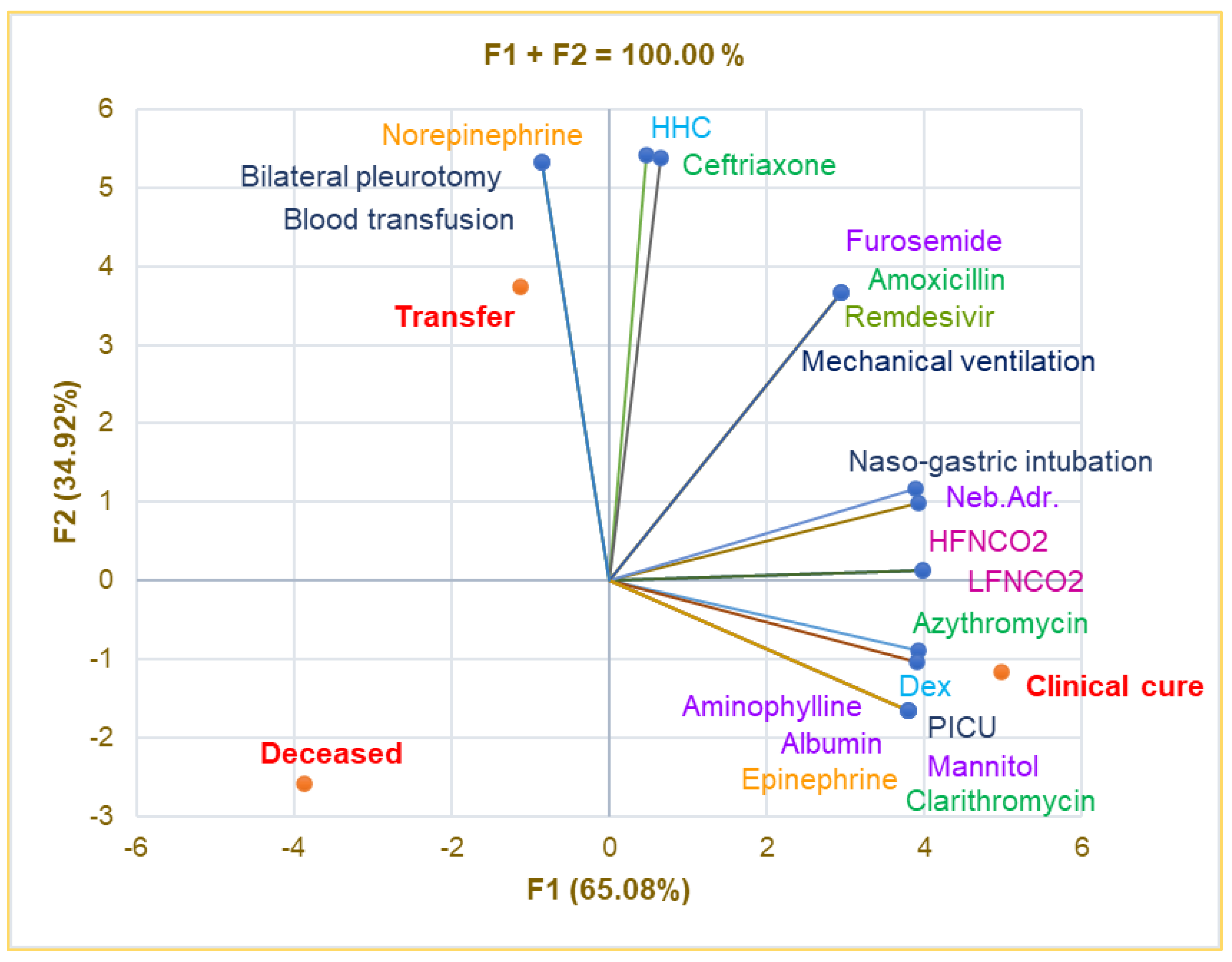

The correlation matrix and

Figure 5 show that intensive care in the PICU is substantially associated with Albumin, Aminophylline, Mannitol, Epinephrine, Clarithromycin, and clinical cure (r = 0.999,

p<0.05) and strongly correlates with LFNC, HFNC, nasogastric intubation, Azithromycin, and Dex (r = 0.899 – 0.990,

p>0.05).

The transfer significantly correlates with bilateral pleurotomy, blood transfusion, and Norepinephrine (r = 0.999, p<0.05) and is strongly associated with HHC and Ceftriaxone (r = 0.929 – 0.945, p>0.05). Mechanical ventilation is remarkably correlated with Furosemide, Remdesivir, and Amoxicillin (r = 0.999, p<0.05) and shows a good correlation with nasogastric intubation and nebulized Adrenaline (r = 0.849 - 0.866, p>0.05). Bilateral pneumotomy strongly correlates with Ceftriaxone and HHC (r = 0.929 – 0.945, p>0.05).

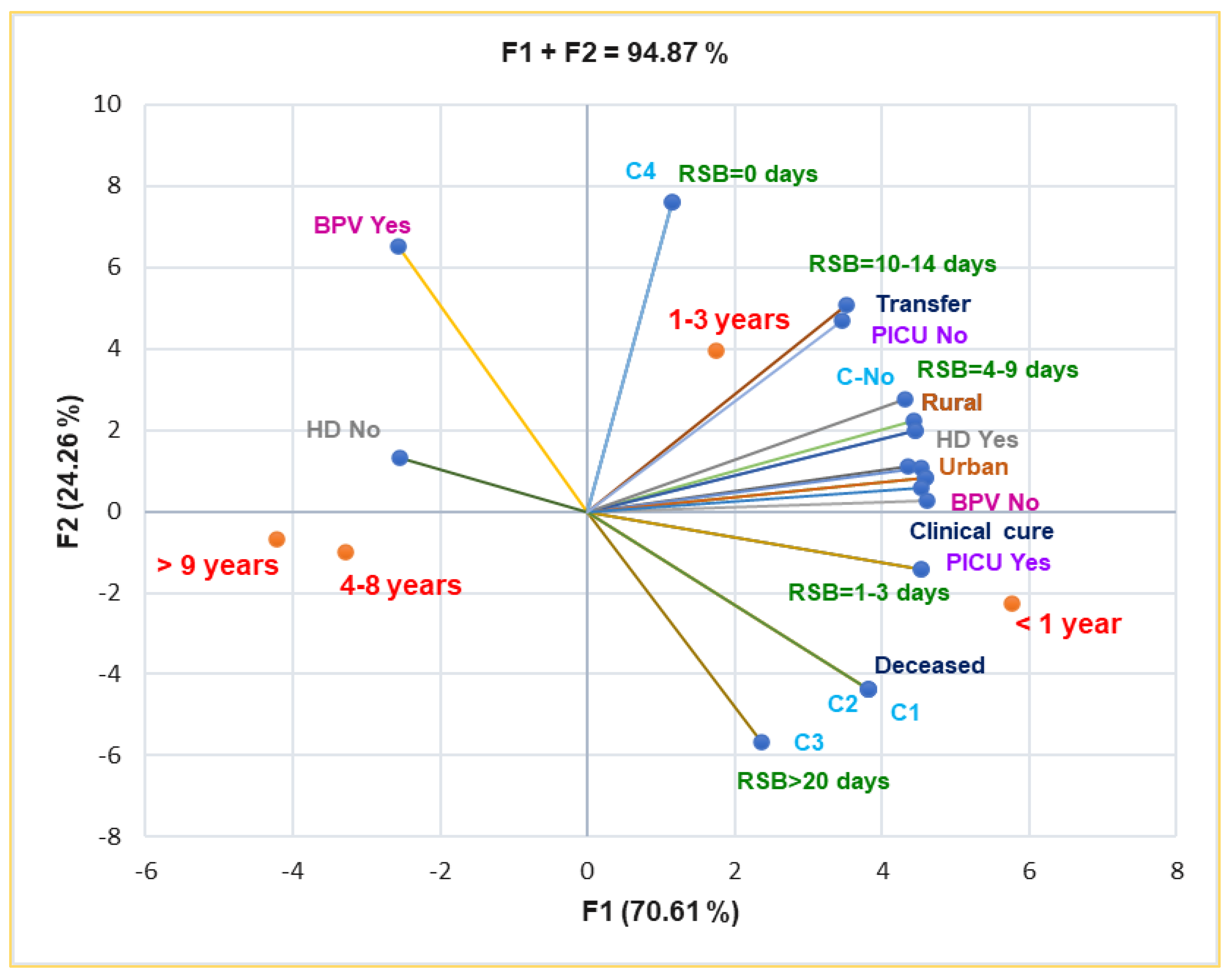

3.5. Correlations of Sociodemographic & Baseline Factors and Clinical Findings

The BPV-No is significantly associated with HD-yes, rural residence, RSB=1 – 3 days and 4 – 9 days, and PICU intensive care (r = 0.957 – 0.975,

p<0.05,

Figure 6). It also shows a good correlation with complications C1-C4 and death prognostic (r = 0.808,

p>0.05), RSB=10-14 days, and transfer (r = 0.785 – 0.761,

p>0.05).

Both rural and urban residences are substantially correlated with HD-Yes and clinical cure (r = 0.973 – 0.996,

p<0.05) and moderately associated with complications (C1-C3), r = 0.757 – 0.662,

p>0.05 (

Figure 6).

C1-C3 are moderately associated with RSB>20 days, RSB=4-9 days, and clinical cure (r = 0.730 – 0.786,

p>0.05), and evidence a high correlation with PICU intensive care (r = 0.917, p>0.05). C2 and C3 remarkably correlate with death (r = 0.999,

p<0.05). Moreover,

Figure 6 also indicates the place of each age group associated with all baseline and clinical outcomes: infants and young children up to 3 years are the most vulnerable pediatric patients.

4. Discussion

Bordetella pertussis infection can affect individuals across all age groups, with a wide range of clinical manifestations posing a significant global public health challenge [

42]. The number of reported cases and incidences of pertussis disease are collected annually through the WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form on Immunization [

43]. Each country's news is updated and made publicly available in a short time. All recent information results in global trends and leads to evidence-based decisions in different policies (for example, the need for booster vaccine doses and targeted age groups) [

44,

45]. The present study aims to conduct a complex investigation of the clinical and epidemiological aspects of

Bordetella pertussis infection in children, focusing on disease burden, risk factors, and vaccination efficacy. It involves 38 pediatric patients from the Southeast region of Romania hospitalized with

B. pertussis infection in the Pediatric Departments of Constanta County Clinical Emergency Hospital "St. Apostle Andrew" between January 1, 2024, and September 30, 2024, most of them up to 3 years age (31/38, 81.58%).

4.1. Clinical Insights

Our study results emphasize the need for comprehensive diagnostic approaches in pediatric patients presenting with respiratory symptoms, as coinfections can complicate the clinical picture and delay effective treatment. Early detection of these pathogens through advanced molecular techniques, such as qPCR, and careful monitoring of respiratory symptom progression can significantly improve patient outcomes and prevent complications associated with these infections.

Our findings highlight the significant prevalence of various pathogens' codetection in pediatric patients with respiratory symptoms, with the timing of pathogen detection before presentation to the Emergency Care Unit (ECU) showing a clear correlation to the clinical outcomes and severity of respiratory infections. The most common codetection (31.58%) occurred between 4-9 days before admission, where

Streptococcus pneumoniae was the predominant co-pathogen, detected in 50% of these cases. Respiratory viruses, such as enteroviruses (EV-HRV) and SARS-CoV-2, were also frequently co-detected in this period, each found in 25% of patients. Other pathogens, such as

Human Parainfluenza Virus-3 (HPIV-3),

Human Adenovirus (HAdVs),

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and

Pneumocystis jirovecii, were less commonly co-detected but were still notable, each appearing in 8.33% of the patients. These findings align with studies demonstrating coinfection's role in pediatric respiratory diseases' severity and complexity [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Codetection of bacterial and viral pathogens is common in pediatric patients with acute respiratory infections. They influence the clinical course of pertussis infections and the outcome of pneumonia and bronchiolitis [

50]

. S. pneumoniae has been identified as a frequent co-infecting bacterium in viral respiratory infections, particularly in children with influenza or respiratory viral infections [

51]. Similarly, RSV and EV-HRV have been implicated in severe respiratory illness when combined with other respiratory pathogens [

52].

This study confirms that pertussis manifests with a broad range of clinical symptoms in pediatric patients, from a mild, persistent cough to severe paroxysmal episodes that can lead to complications such as apnea, pneumonia, and even encephalopathy. The disease was most severe in infants under six months old, who had the highest hospitalization rates. In severe cases, infants may develop pneumonia and/or respiratory failure, necessitating advanced therapeutic interventions such as conventional mechanical ventilation, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, plasmapheresis, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) [

53,

54].

The poorest prognosis is linked to hyperleukocytosis with a predominance of lymphocytes, making ECMO a crucial intervention to lower leukocyte counts [

55]. It has been suggested that these fatalities result from leukocyte aggregation in small pulmonary vessels, leading to irreversible pulmonary hypertension [

56,

57]. Several retrospective studies have identified hyperleukocytosis as a significant risk factor for mortality in young infants and an independent predictor of fatal outcomes across all age groups [

28,

31,

58]. Therefore, an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count is a hallmark feature of pertussis. It is significantly higher in severe cases than in mild cases and reaches extreme levels in fatal cases [

59,

60,

61]. The impaired deformability of white blood cells contributes to their tendency to obstruct narrowed alveolar capillaries. Unlike erythrocytes, which pass through these vessels efficiently, leukocytes require 10–15 times longer, leading to embolism due to leukocyte aggregation [

62]. This blockage can result in hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension, which, in turn, can compromise cardiac function and lead to heart failure in critical cases [

63]. Severe hyperleukocytosis, defined as a WBC count exceeding 50 × 10

3/µL, has been identified as an independent risk factor for malignant pertussis, a life-threatening form of the disease [

33]. Research has demonstrated that in cases where leukocyte counts exceeded 100 × 10⁹/L and no targeted interventions were implemented to reduce WBC levels, standard treatment alone was ineffective, resulting in fatal outcomes in all reported instances [

64]. Our findings align with previous research indicating that an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count is a key clinical feature of pertussis, particularly in severe and fatal cases. The data suggest that leukocytosis contributes significantly to disease progression and poor outcomes. Four children experienced complications, including bilateral apical-lateral-basal pneumothorax, a pulmonary condensation process in the lower third of the right pulmonary field, confluent alveolar opacities, and interstitial peri- and hylo-basal bilateral enlarged congestive hilar regions. Additional very severe complications included aspiration pneumonia, kidney failure, paroxysmal manifestations, and anasarca. Our study reports that two pediatric patients did not survive despite comprehensive medical intervention.

Complications associated with pertussis, including post-tussive vomiting, sleep disturbances, and rib and vertebral fractures caused by intense coughing episodes, remain overlooked and underreported in clinical practice [

65]. The impact of long-term respiratory consequences also requires further investigation, as studies have shown that persistent cough and airway hyperreactivity can persist for months following recovery [

66,

67].

The antibacterial treatment [

68], including macrolides [

69] and beta-lactams [

70], was administered according to international and national guidelines for managing pertussis [

71]. Based on clinical indication, the antiviral treatment was mainly used for coinfections with other viral pathogens, such as Remdesivir, in cases involving SARS-CoV-2 [

72].

4.2. Epidemiological Insights

Pertussis disease is particularly dangerous for infants and young children, as it can cause serious complications (pneumonia, extensive lung lesions, encephalitis, etc.) and even death [

73]. It is estimated that the immunity determined by the disease is not permanent, which explains the frequent reinfection of some patients [

74]. The vaccine against pertussis was introduced in Romania in 1960, and the routine immunization program for children led to substantial reductions in the occurrence of the disease; 2008 was the year of the switch to aP vaccines for the primary series of vaccination, the reinforcing dose, and preschool booster) [

75]. Although pertussis is recognized as a vaccine-preventable disease, our findings show that only 7/38 pediatric patients (18.42%) received the

B. pertussis vaccine (

Table 5). This aspect is similar to those from other countries regarding a decline in vaccination coverage by 24 months [

76]. Moreover, our pediatric patients did not benefit from maternal pertussis immunization; therefore, the highest incidence of whooping cough in infants <1 year (17/38, 44.74%) is because Pertussis vaccine acceptancy by Romanian pregnant women decreased from 85% in 2019 to 44.4% in 2022 (p < 0.01), in association with an increasing pregnancy age and a considerable diminution of the educational level [

77]

. Of 7 vaccinated pediatric patients, 3 are young children (1-3 years), 2 are 4-8 years, and the other 2 are teenagers (>9 years). Our findings are similar to those recently reported in Europe [

78]

. The minimal percentage of vaccinated pediatric patients could result from the worldwide immunization routine regression during the COVID-19 pandemic [

79]. The parental antivaccination beliefs could also explain the progressive incidence of pertussis [

80,

81,

82,

83] and other preventable infectious diseases in childhood [

84,

85,

86,

87]

.

The clinical outcomes, hospitalization period, and therapeutic protocol analysis highlight the benefits of pertussis vaccination in pediatric patients (

Table 5). Hence, the incidence of fever, ARDS, rhinorrhea, and O2 DS is appreciably lower in vaccinated children (28.57% vs. 45.16% and 67.74%, 14.29% vs. 41.94% and 0% vs. 22.58%,

p<0.05). The highest WBC, Lym, and CRP levels are measured in non-vaccinated pediatric patients (6.45% vs. 0%, 35.48% vs. 14.29%, and 3.23% vs. 0%,

p<0.05). Only 57.14% of BPV-Yes patients were hospitalized vs. 96.77% of non-vaccinated ones,

p<0.05 (

Table 5). Vaccinated children had no complications (100% vs. 87.10%,

p<0.05), and they did not need HFNCO2 and special care in PICU (0% vs. 12.90% and 22.58%, respectively,

p<0.05). The deceased children were unvaccinated (6.45% vs. 0%, p<0.05). Our results are consistent with previous research indicating that younger infants face the most significant risk of severe pertussis complications [

28] and death caused by their underdeveloped immune systems due to lack or incomplete vaccination [

5,

88].

Our study confirms previous research, indicating that pertussis is diagnosed more often in urban areas (21/38, 55.26%) than in rural regions (17/38, 44.74%), p<0.05. In addition, almost all vaccinated pediatric patients had urban residences (85.71% vs. 14.29%,

p<0.05). This discrepancy may be due to higher population density, better healthcare access, frequent testing, and greater awareness among urban healthcare professionals [

89,

90]

. However, it does not necessarily imply a lower disease burden in rural areas; instead, it suggests the possibility of underreporting due to limited diagnostic resources [

91]

Regarding pertussis management, the National Institute for Public Health from Romania publicly displayed the following recommendations [

35]:

Seeing a doctor when symptoms suggestive of the disease appear: intense and prolonged coughing fits, vomiting after coughing fits, difficulty breathing in infants, noisy inhales ("whooping cough");

Timely vaccination of infants and recovery of arrears;

Vaccination of pregnant women to ensure the newborn and mother's protection;

Adults' vaccination with a booster every 10 years;

Promotion of "cocooning" vaccination in the infant's entourage (in a family expecting a newborn, the parents, grandparents, and siblings of the infant should be vaccinated according to the national vaccination calendar or recommendations for adults).

Although vaccination campaigns are widespread, the continued occurrence of pertussis cases in fully immunized children highlights the shortcomings of current acellular pertussis vaccines [

92]. Szwejser-Zawislak et al. found that children who received their last dose more than five years ago faced a significantly higher risk of infection, further supporting evidence of waning immunity [

93]. This finding strengthens the growing consensus that aP vaccines offer only short-term protection, emphasizing the need for alternative approaches, including (i) administering booster doses earlier and more frequently [

94,

95]

, (ii) reevaluating the use of whole-cell pertussis vaccines in specific populations [

93,

96,

97]

, and (iii) developing enhanced pertussis vaccines with longer-lasting immunity [

98,

99,

100]

. Recent advancements in the development of live attenuated pertussis vaccines (LAVs) have shown encouraging results in preclinical research, offering stronger mucosal immunity and more durable protection than acellular vaccines [

101,

102,

103,

104]. These findings underscore the importance of continued vaccine innovation in overcoming existing pertussis prevention and control challenges [

99,

105,

106,

107,

108]. Moreover, vaccinating mothers during pregnancy has been proven to lower the risk of severe pertussis in young infants by providing passive immunity [

109,

110,

111]

.

4.3. Limitations

Despite its valuable findings, this study has several limitations that should be mentioned.

As a retrospective analysis, the study relies on previously recorded medical data, which may introduce biases such as incomplete documentation, variability in clinical assessments, and potential misclassification of diagnoses.

The study includes only 38 pediatric patients, which may not represent the broader population of children affected by Bordetella pertussis infection. The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings and reduce statistical power for specific associations.

Data were collected from a single hospital (Constanta County Clinical Emergency Hospital), which may not fully capture regional or national variations in pertussis infection patterns, coinfections, and clinical management strategies. Future studies should incorporate a prospective, multicenter design with a larger cohort, include long-term follow-up of patients, and evaluate the impact of vaccination status and socioeconomic factors on disease outcomes.

4.4. Essential Considerations

Our study revealed that many cases were initially mistaken for viral respiratory infections, resulting in delays in appropriate treatment and contact tracing. While qPCR testing has enhanced early detection, its sensitivity diminishes as the disease progresses, particularly in later stages. The accurate and timely diagnosis of pertussis remains a significant challenge. Improving clinical awareness and expanding laboratory capacity are crucial for enhancing detection rates and controlling transmission. Serological testing is increasingly being investigated as a supplementary diagnostic method, especially for young children with persistent coughs [

112,

113,

114]. However, the widespread adoption of this approach remains limited due to the lack of standardized serological assays [

115].

Another major challenge is the underreporting and misclassifying pertussis cases in national surveillance systems, contributing to underestimating the disease burden. Strengthening integrated surveillance systems, raising physician awareness, and improving laboratory testing capabilities are essential to address these issues [

35]. The variation in positivity rates may be linked to the underdiagnosis of

Bordetella pertussis, either due to the lack of routine testing for the bacterium or, particularly during the winter season, the potential misinterpretation of symptoms as those of other common respiratory infections [

50,

116].

Multiple factors, including maternal vaccination during pregnancy and the child's age, influence the frequency and severity of pertussis in infants [

117,

118,

119]. However, a significant factor sustaining disease transmission could be asymptomatic carriage and underdiagnosis, especially among older children and adults, who act as reservoirs for infection, as previous findings reported [

116,

120].

5. Conclusions

Despite widespread vaccination campaigns, Bordetella pertussis remains a significant public health concern, primarily due to waning immunity and diagnostic limitations. Combatting antivaccination practices through solid and accurate medical education, strengthening booster vaccination programs, improving early detection, and enhancing surveillance efforts are critical for effective pertussis control. Bridging these gaps through ongoing research and targeted public health initiatives will be essential in reducing the disease burden among children and ensuring more sustained protection against pertussis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, PBS abnormalities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.M., T.C., V.P., and R.M.S.; methodology T.C., V.P., and R.M.S.; software, T.C., and V.P.; validation A.L., A.L.B., G.B., and S.C.C.; formal analysis, V.P.; investigation, C.M.M., A.L., A.L.B., G.B., S.F., V.V.L., S.C.C., M.G., F.S., F.D.E., A.S., and R.M.S.; resources, T.C., S.C.C., F.D.E., G.B., S.F.; data curation, C.M.M., T.C., A.L.B., and S.F.; writing—T.C., V.P., A.L.B., F.D.E., A.S., and R.M.S.; writing—review and editing, C.M.M., A.L., T.C., A.L.B., G.B., S.F., V.V.L., V.P., S.C.C., M.G., F.S., F.D.E., A.S., and R.M.S; visualization, C.M.M., A.L., T.C., A.L.B., G.B., S.F., V.V.L., V.P., S.C.C., M.G., F.S., F.D.E., A.S., and R.M.S.; supervision, C.M.M., A.L., T.C., G.B., and R.M.S.; A.L. and G.B. contributed equally with C.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Studies of Constanta County Clinical Emergency Hospital "St. Apostle Andrew". Document number 08 was approved on March 05, 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the solely retrospective use of the clinical electronic repository without altering the clinical pathways or the patient's treatment.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the ongoing study, the data presented in this study are available on request from the first author and the first corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Caulfield, A.D.; Harvill, E.T. Bordetella Pertussis. In Molecular Medical Microbiology; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 1463–1478.

- Decker, M.D.; Edwards, K.M. Pertussis (Whooping Cough). J Infect Dis 2021, 224, S310–S320. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhuo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fan, F.; Wang, C.; Zhou, W.; Xiao, G.; Chen, F. Clinical Features of Pertussis in 248 Hospitalized Children and Risk Factors of Severe Pertussis. Chinese Journal of Applied Clinical Pediatrics 2023, 38. [CrossRef]

- Fry, N.K.; Campbell, H.; Amirthalingam, G. JMM Profile: Bordetella Pertussis and Whooping Cough (Pertussis): Still a Significant Cause of Infant Morbidity and Mortality, but Vaccine-Preventable. J Med Microbiol 2021, 70. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, S.; Liao, Q.; Wan, C. Invasive Bordetella Pertussis Infection in Infants: A Case Report. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Vyas, H. Early Infantile Pertussis; Increasingly Prevalent and Potentially Fatal. Eur J Pediatr 2000, 159, 898–900. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, E.; Edwards, K. Health Burden of Pertussis in Adolescents and Adults. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2005, 24, S44–S47. [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.D.; Wendorf, K.; Bregman, B.; Lehman, D.; Nieves, D.; Bradley, J.S.; Mason, W.H.; Sande-Lopez, L.; Lopez, M.; Federman, M.; et al. An Observational Study of Severe Pertussis in 100 Infants ≤120 Days of Age. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2018, 37, 202–205. [CrossRef]

- WHO Pertussis Vaccines: WHO Position Paper, August 2015-Recommendations. Vaccine 2016, 34.

- Sobanjo-ter Meulen, A.; Duclos, P.; McIntyre, P.; Lewis, K.D.C.; Van Damme, P.; O'Brien, K.L.; Klugman, K.P. Assessing the Evidence for Maternal Pertussis Immunization: A Report From the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Symposium on Pertussis Infant Disease Burden in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2016, 63, S123–S133. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D.P.; Von König, C.H.W.; Heininger, U. Health Burden of Pertussis in Infants and Children. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2005, 24.

- Abu-Raya, B.; Bettinger, J.A.; Vanderkooi, O.G.; Vaudry, W.; Halperin, S.A.; Sadarangani, M.; Bridger, N.; Morris, R.; Top, K.; Halperin, S.; et al. Burden of Children Hospitalized With Pertussis in Canada in the Acellular Pertussis Vaccine Era, 1999–2015. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2020, 9, 118–127. [CrossRef]

- Préziosi, M.; Halloran, M.E. Effects of Pertussis Vaccination on Disease: Vaccine Efficacy in Reducing Clinical Severity. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2003, 37, 772–779. [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, T.; Dinleyici, E.C.; Kara, A.; Kurugöl, Z.; Tezer, H.; Aksakal, N.B.; Biri, A.; Azap, A. The Present and Future Aspects of Life-Long Pertussis Prevention: Narrative Review with Regional Perspectives for Türkiye. Infect Dis Ther 2023, 12, 2495–2512. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yue, N.; Nie, D.; Ai, L.; Zhu, C.; Lv, H.; Wang, G.; Hu, D.; Wu, Y.; et al. Impact of Outdoor Air Pollution on the Incidence of Pertussis in China: A Time-Series Study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2231. [CrossRef]

- Kovitwanichkanont, T. Public Health Measures for Pertussis Prevention and Control. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017, 41.

- Donzelli, A.; Bellavite, P.; Demicheli, V. Epidemiology of Pertussis and Prevention Strategies: Problems and Perspectives. Epidemiol Prev 2019, 43. [CrossRef]

- Raguckas, S.E.; VandenBussche, H.L.; Jacobs, C.; Klepser, M.E. Pertussis Resurgence: Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention, and Beyond. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy 2007, 27, 41–52. [CrossRef]

- What is the 100-day cough?, available online at https://www.unicef.org/eca/stories/what-100-day-cough (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- Qin, S.M.; Song, X.L.; Dong, W.Y.; Yang, D.D.; Qin, L.; Ma, X.Q.; Mo, S.Y. Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics of Pertussis in 139 Infants. Journal of Medical Pest Control 2022, 38. [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Lan, S.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; Hu, B. Croup and Pertussis Cough Sound Classification Algorithm Based on Channel Attention and Multiscale Mel-Spectrogram. Biomed Signal Process Control 2024, 91, 106073. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-S.; Wang, H.-M.; Yao, K.-H.; Liu, Y.; Lei, Y.-L.; Deng, J.-K.; Yang, Y.-H. Clinical Characteristics, Molecular Epidemiology and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Pertussis among Children in Southern China. World Journal of Pediatrics 2020, 16, 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Dan-Xia, W.; Qiang, C.; Lan, L.; Kun-Ling, S.; Kai-Hu, Y. Prevalence of Bordetella Pertussis Infection in Children with Chronic Cough and Its Clinical Features. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics 2019, 21. [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, T.K.; Samprathi, M.; Jayashree, M.; Gautam, V.; Sangal, L. Clinical Profile of Critical Pertussis in Children at a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit in Northern India. Indian Pediatr 2020, 57. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Xu, L.; Pan, J. Analysis of Multiple Factors Involved in Pertussis-Like Coughing. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2020, 59, 641–646. [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Picone, J.; Harati, A.; Lu, S.; Jenkyns, M.H.; Polgreen, P.M. Detecting Paroxysmal Coughing from Pertussis Cases Using Voice Recognition Technology. PLoS One 2013, 8, e82971. [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.M.; Kang, J.; Kenney, S.M.; Wong, T.Y.; Bitzer, G.J.; Kelly, C.O.; Kisamore, C.A.; Boehm, D.T.; DeJong, M.A.; Wolf, M.A.; et al. Reinvestigating the Coughing Rat Model of Pertussis To Understand Bordetella Pertussis Pathogenesis. Infect Immun 2021, 89. [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiar, B.; Zhiaul Muttaqin, I.; Maulana, G.; Tsurayya, G.; Safana, G. Leukocytosis as a Predictor of Clinical Worsening and Complications in Children with Pertussis: A Systematic Review of Case Study. Poltekita : Jurnal Ilmu Kesehatan 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, C.; Klein, N.; Peters, M. Is Leukocytosis a Predictor of Mortality in Severe Pertussis Infection? Intensive Care Med 2000, 26. [CrossRef]

- Coquaz-Garoudet, M.; Ploin, D.; Pouyau, R.; Hoffmann, Y.; Baleine, J.-F.; Boeuf, B.; Patural, H.; Millet, A.; Labenne, M.; Vialet, R.; et al. Malignant Pertussis in Infants: Factors Associated with Mortality in a Multicenter Cohort Study. Ann Intensive Care 2021, 11, 70. [CrossRef]

- De Berry, B.B.; Lynch, J.E.; Chung, D.H.; Zwischenberger, J.B. Pertussis with Severe Pulmonary Hypertension and Leukocytosis Treated with Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Pediatr Surg Int 2005, 21, 692–694. [CrossRef]

- Carbonetti, N.H. Pertussis Leukocytosis: Mechanisms, Clinical Relevance and Treatment. Pathog Dis 2016, 74.

- Tian, S.; Wang, H.; Deng, J. Fatal Malignant Pertussis with Hyperleukocytosis in a Chinese Infant. Medicine 2018, 97, e0549. [CrossRef]

- Increase of Pertussis Cases in the EU/EEA. 2024, available online at https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/increase-pertussis-cases-eueea (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- Cresterea indidentei tusei convulsive in Romania, available online at https://insp.gov.ro/2024/05/14/comunicat-privind-cresterea-incidentei-tusei-convulsive-in-romania-si-recomandari-de-sanatate-publica/ (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- Campania de prevenire a bolilor transmisibile 2024, available online at https://dspb.ro/2024/08/23/campania-de-prevenire-a-bolilor-transmisibile-care-se-desfasoara-pe-toata-luna-august-2024-in-vederea-informarii-populatiei-doritoare/ (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- Mihai, C.M.; Lupu, A.; Chisnoiu, T.; Balasa, A.L.; Baciu, G.; Lupu, V.V.; Popovici, V.; Suciu, F.; Enache, F.-D.; Cambrea, S.C.; et al. A Comprehensive Analysis of Echinococcus Granulosus Infections in Children and Adolescents: Results of a 7-Year Retrospective Study and Literature Review. Pathogens 2025, 14, 53. [CrossRef]

- Moroșan, E.; Dărăban, A.; Popovici, V.; Rusu, A.; Ilie, E.I.; Licu, M.; Karampelas, O.; Lupuliasa, D.; Ozon, E.A.; Maravela, V.M.; et al. Sociodemographic Factors, Behaviors, Motivations, and Attitudes in Food Waste Management of Romanian Households. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2738. [CrossRef]

- Streba, L.; Popovici, V.; Mihai, A.; Mititelu, M.; Lupu, C.E.; Matei, M.; Vladu, I.M.; Iovănescu, M.L.; Cioboată, R.; Călărașu, C.; et al. Integrative Approach to Risk Factors in Simple Chronic Obstructive Airway Diseases of the Lung or Associated with Metabolic Syndrome—Analysis and Prediction. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1851. [CrossRef]

- WBC counts, available online at https://www.verywellhealth.com/white-blood-cell-wbc-count-1942660 (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- Lymphocytes, available online at https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-are-lymphocytes-4140826 (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- Zhang, M.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H.; Yin, Z.; Liang, X. Challenges to Global Pertussis Prevention and Control. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology 2023, 44.

- WHO, Pertussis reported cases and incidence, available online at https://immunizationdata.who.int/global/wiise-detail-page/pertussis-reported-cases-and-incidence?CODE=ROU&YEAR= (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- Vaccination schedule for Pertussis, World Health Organization, Overview Vaccines, and Immunization, available online at https://immunizationdata.who.int/global/wiise-detail-page/vaccination-schedule-for-pertussis?ISO_3_CODE=&TARGETPOP_GENERAL= (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- World Health Organization, Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Surveillance Standards, available online at https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/immunization-analysis-and-insights/surveillance/surveillance-for-vpds/vpd-surveillance-standards (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- Jiang, S.; Liu, P.; Xiong, G.; Yang, Z.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Yu, X. Coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 and Multiple Respiratory Pathogens in Children. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) 2020, 58, 1160–1161. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Deng, L.; Xiao, F.; Fu, J.; Deng, J.; Wang, F.; Yang, J. [Clinical Analysis of Children with Pertussis and Significance of Respiratory Virus Detection in the Combined Diagnosis]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2017, 55.

- Tabatabai, J.; Ihling, C.M.; Manuel, B.; Rehbein, R.M.; Schnee, S. V; Hoos, J.; Pfeil, J.; Grulich-Henn, J.; Schnitzler, P. Viral Etiology and Clinical Characteristics of Acute Respiratory Tract Infections in Hospitalized Children in Southern Germany (2014–2018). Open Forum Infect Dis 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Almannaei, L.; Alsaadoon, E.; AlbinAli, S.; Taha, M.; Lambert, I. A Retrospective Study Examining the Clinical Significance of Testing Respiratory Panels in Children Who Presented to a Tertiary Hospital in 2019. Access Microbiol 2022, 4. [CrossRef]

- Efendiyeva, E.; Kara, T.T.; Erat, T.; Yahşi, A.; Karbuz, A.; Kocabaş, B.A.; Özdemir, H.; Karahan, Z.C.; İnce, E.; Çiftçi, E. The Incidence and Clinical Effects of Bordetella Pertussis in Children Hospitalized with Acute Bronchiolitis. Turkish Journal of Pediatrics 2020, 62. [CrossRef]

- Giucă, M.C.; Cîlcic, C.; Mihăescu, G.; Gavrilă, A.; Dinescu, M.; Gătej, R.I. Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Haemophilus Influenzae Nasopharyngeal Molecular Detection in Children with Acute Respiratory Tract Infection in SANADOR Hospital, Romania. J Med Microbiol 2019, 68, 1466–1470. [CrossRef]

- Gunning, C.E.; Rohani, P.; Mwananyanda, L.; Kwenda, G.; Mupila, Z.; Gill, C.J. Young Zambian Infants with Symptomatic RSV and Pertussis Infections Are Frequently Prescribed Inappropriate Antibiotics: A Retrospective Analysis. PeerJ 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Halasa, N.B.; Barr, F.E.; Johnson, J.E.; Edwards, K.M. Fatal Pulmonary Hypertension Associated With Pertussis in Infants: Does Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Have a Role? Pediatrics 2003, 112, 1274–1278. [CrossRef]

- Krawiec, C.; Ballinger, K.; Halstead, E.S. Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation as an Airway Clearance Technique during Venoarterial Extracorporeal Life Support in an Infant with Pertussis. Front Pediatr 2017, 5. [CrossRef]

- Bailly, D.K.; Reeder, R.W.; Zabrocki, L.A.; Hubbard, A.M.; Wilkes, J.; Bratton, S.L.; Thiagarajan, R.R. Development and Validation of a Score to Predict Mortality in Children Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Respiratory Failure: Pediatric Pulmonary Rescue With Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Prediction Score*. Crit Care Med 2017, 45, e58–e66. [CrossRef]

- Fueta, P.O.; Eyituoyo, H.O.; Igbinoba, O.; Roberts, J. Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Pulmonary Hypertension in an Infant with Pertussis Case Report. Case Rep Infect Dis 2021, 2021, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Blasi, F.; Bonanni, P.; Braido, F.; Gabutti, G.; Marchetti, F.; Centanni, S. The Unmet Need for Pertussis Prevention in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in the Italian Context. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020, 16.

- Oñoro, G.; Salido, A.G.; Martínez, I.M.; Cabeza, B.; Gillén, M.; De Azagra, A.M. Leukoreduction in Patients with Severe Pertussis with Hyperleukocytosis. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2012, 31. [CrossRef]

- Crowcroft, N.S.; Booy, R.; Harrison, T.; Spicer, L.; Britto, J.; Mok, Q.; Heath, P.; Murdoch, I.; Zambon, M.; George, R.; et al. Severe and Unrecognised: Pertussis in UK Infants. Arch Dis Child 2003, 88. [CrossRef]

- Al Hanshi, S.; Al Ghafri, M.; Al Ismaili, S. Severe Pertussis Pneumonia Managed with Exchange Transfusion. Oman Med J 2014, 29. [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, K.; Skerry, C.; Carbonetti, N. Association of Pertussis Toxin with Severe Pertussis Disease. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11, 373. [CrossRef]

- Straney, L.; Schibler, A.; Ganeshalingham, A.; Alexander, J.; Festa, M.; Slater, A.; Maclaren, G.; Schlapbach, L.J. Burden and Outcomes of Severe Pertussis Infection in Critically Ill Infants. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2016, 17. [CrossRef]

- AOYAMA, T.; IDE, Y.; WATANABE, J.; TAKEUCHI, Y.; IMAIZUMI, A. Respiratory Failure Caused by Dual Infection with Bordetella Pertussis and Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Pediatrics International 1996, 38, 282–285. [CrossRef]

- Paddock, C.D.; Sanden, G.N.; Cherry, J.D.; Gal, A.A.; Langston, C.; Tatti, K.M.; Wu, K.H.; Goldsmith, C.S.; Greer, P.W.; Montague, J.L.; et al. Pathology and Pathogenesis of Fatal Bordetella Pertussis Infection in Infants. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2008, 47. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Fan, H.; Guo, H.; Yin, Z.; Dong, M.; Huang, X. Multiple Rib and Vertebral Fractures Associated with Bordetella Pertussis Infection: A Case Report. BMC Infect Dis 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, A.; Aris, E.; Harrington, L.; Simeone, J.C.; Ramond, A.; Lambrelli, D.; Papi, A.; Boulet, L.P.; Meszaros, K.; Jamet, N.; et al. Burden of Pertussis in Individuals with a Diagnosis of Asthma: A Retrospective Database Study in England. J Asthma Allergy 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Chacón, G.P.; Fathima, P.; Jones, M.; Estcourt, M.J.; Gidding, H.F.; Moore, H.C.; Richmond, P.C.; Snelling, T. Association between Pertussis Vaccination in Infancy and Childhood Asthma: A Population-Based Record Linkage Cohort Study. PLoS One 2023, 18. [CrossRef]

- Cimolai, N. Pharmacotherapy for Bordetella Pertussis Infection. II. A Synthesis of Clinical Sciences. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2021, 57, 106257. [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.-M.; Hua, C.-Z.; Fang, C.; Liu, J.-J.; Xie, Y.-P.; Lin, L.-N.; Wang, G.-L. Effect of Macrolides and β-Lactams on Clearance of Bordetella Pertussis in the Nasopharynx in Children With Whooping Cough. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2021, 40, 87–90. [CrossRef]

- He, W.-Q.; Kirk, M.D.; Sintchenko, V.; Hall, J.J.; Liu, B. Antibiotic Use Associated with Confirmed Influenza, Pertussis, and Nontyphoidal Salmonella Infections. Microbial Drug Resistance 2020, 26, 1482–1490. [CrossRef]

- Pertussis Treatment and Prophylaxis 2024, available online at https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/pertussis/hcp/treatment.html (Accessed on March 10, 2025).

- Samuel, A.M.; Hacker, L.L.; Zebracki, J.; Bogenschutz, M.C.; Schulz, L.; Strayer, J.; Vanderloo, J.P.; Cengiz, P.; Henderson, S. Remdesivir Use in Pediatric Patients for SARS-CoV-2 Treatment: Single Academic Center Study. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2023, 42, 310–314. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, K.H.T.; Duclos, P.; Nelson, E.A.S.; Hutubessy, R.C.W. An Update of the Global Burden of Pertussis in Children Younger than 5 Years: A Modelling Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17. [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, A.E.; Pastore Celentano, L.; Ciofi Degli Atti, M.L.; Salmaso, S. Diagnosis and Management of Pertussis. CMAJ. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2005, 172.

- Heininger, U.; André, P.; Chlibek, R.; Kristufkova, Z.; Kutsar, K.; Mangarov, A.; Mészner, Z.; Nitsch-Osuch, A.; Petrović, V.; Prymula, R.; et al. Comparative Epidemiologic Characteristics of Pertussis in 10 Central and Eastern European Countries, 2000-2013. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0155949. [CrossRef]

- Hill, H.A.; Yankey, D.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Mu, Y.; Chen, M.; Peacock, G.; Singleton, J.A. Decline in Vaccination Coverage by Age 24 Months and Vaccination Inequities Among Children Born in 2020 and 2021 — National Immunization Survey-Child, United States, 2021–2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024, 73, 844–853. [CrossRef]

- Herdea, V.; Tarciuc, P.; Ghionaru, R.; Lupusoru, M.; Tataranu, E.; Chirila, S.; Rosu, O.; Marginean, C.O.; Leibovitz, E.; Diaconescu, S. Vaccine Hesitancy Phenomenon Evolution during Pregnancy over High-Risk Epidemiological Periods—"Repetitio Est Mater Studiorum." Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; Samara, A.; Campbell, H.; Ladhani, S.N.; Amirthalingam, G. Recent Increase in Infant Pertussis Cases in Europe and the Critical Importance of Antenatal Immunizations: We Must Do Better…now. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2024, 146, 107148. [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.; Jombart, T. Worldwide Routine Immunisation Coverage Regressed during the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3531–3535. [CrossRef]

- Glanz, J.M.; McClure, D.L.; Magid, D.J.; Daley, M.F.; France, E.K.; Salmon, D.A.; Hambidge, S.J. Parental Refusal of Pertussis Vaccination Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Pertussis Infection in Children. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1446–1451. [CrossRef]

- Stein-Zamir, C.; Shoob, H.; Abramson, N.; Brown, E.H.; Zimmermann, Y. Pertussis Outbreak Mainly in Unvaccinated Young Children in Ultra-Orthodox Jewish Groups, Jerusalem, Israel 2023. Epidemiol Infect 2023, 151. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, N.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Cui, T.; Jin, H. The Association between Vaccine Hesitancy and Pertussis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ital J Pediatr 2023, 49. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Botia, I.; Riera-Bosch, M.T.; Rodríguez-Losada, O.; Soler-Palacín, P.; Melendo, S.; Moraga-Llop, F.; Balcells-Ramírez, J.; Otero-Romero, S.; Armadans-Gil, L. Impact of Vaccinating Pregnant Women against Pertussis on Hospitalizations of Children under One Year of Age in a Tertiary Hospital in Catalonia. Enfermedades infecciosas y microbiologia clinica (English ed.) 2022, 40. [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, M.; Müller, M.; Ladhani, S.; Yarwood, J.; Salathé, M.; Ramsay, M. Keep Calm and Carry on Vaccinating: Is Antivaccination Sentiment Contributing to Declining Vaccine Coverage in England? Vaccine 2020, 38, 5297–5304. [CrossRef]

- Aslan, S.; Ozkara, A.; Kasım, I.; Aksoy, H. Why Turkish Parents Refuse Childhood Vaccination? A Qualitative Study. Arch Iran Med 2023, 26, 267–274. [CrossRef]

- Demir Karabulut, S.; Zengin, H.Y. Parents' and Healthcare Professionals' Views and Attitudes towards Antivaccination. Gulhane Medical Journal 2021, 63, 260–266. [CrossRef]

- Cottone, D.M.; McCabe, P.C. Increases in Preventable Diseases Due to Antivaccination Beliefs: Implications for Schools. School Psychology 2022, 37, 319–329. [CrossRef]

- Łoś-Rycharska, E.; Popielarz, M.; Wolska, J.; Sobieska-Poszwa, A.; Dziembowska, I.; Krogulska, A. The Antivaccination Movement and the Perspectives of Polish Parents. Pediatr Pol 2022, 97, 183–192. [CrossRef]

- Slivesteri, S. "Striking Observation of the Discrepancies between the Rural and Urban Healthcare Services Delivery: The Need to Bridge the Gap between Urban and Rural Areas of Uganda." Biomed J Sci Tech Res 2023, 53. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.P.; Johri, M. Socioeconomic and Geographic Inequities in Vaccination among Children 12 to 59 Months in Mexico, 2012 to 2021. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 2023, 47, 1. [CrossRef]

- Kassam, S.; Serrano-Lomelin, J.; Hicks, A.; Crawford, S.; Bakal, J.A.; Ospina, M.B. Geography as a Determinant of Health: Health Services Utilization of Pediatric Respiratory Illness in a Canadian Province. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 8347. [CrossRef]

- Alghounaim, M.; Alsaffar, Z.; Alfraij, A.; Bin-Hasan, S.; Hussain, E. Whole-Cell and Acellular Pertussis Vaccine: Reflections on Efficacy. Medical Principles and Practice 2022, 31, 313–321. [CrossRef]

- Szwejser-Zawislak, E.; Wilk, M.M.; Piszczek, P.; Krawczyk, J.; Wilczyńska, D.; Hozbor, D. Evaluation of Whole-Cell and Acellular Pertussis Vaccines in the Context of Long-Term Herd Immunity. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 11, 1. [CrossRef]

- Versteegen, P.; Barkoff, A.M.; Valente Pinto, M.; van de Kasteele, J.; Knuutila, A.; Bibi, S.; de Rond, L.; Teräsjärvi, J.; Sanders, K.; de Zeeuw-Brouwer, M. lène; et al. Memory B Cell Activation Induced by Pertussis Booster Vaccination in Four Age Groups of Three Countries. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Versteegen, P.; Bonačić Marinović, A.A.; van Gageldonk, P.G.M.; van der Lee, S.; Hendrikx, L.H.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; Buisman, A.M. Long-Term Immunogenicity upon Pertussis Booster Vaccination in Young Adults and Children in Relation to Priming Vaccinations in Infancy. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Perez Chacon, G.; Ramsay, J.; Brennan-Jones, C.G.; Estcourt, M.J.; Richmond, P.; Holt, P.; Snelling, T. Whole-Cell Pertussis Vaccine in Early Infancy for the Prevention of Allergy in Children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Witt, M.A.; Arias, L.; Katz, P.H.; Truong, E.T.; Witt, D.J. Reduced Risk of Pertussis Among Persons Ever Vaccinated With Whole Cell Pertussis Vaccine Compared to Recipients of Acellular Pertussis Vaccines in a Large US Cohort. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2013, 56, 1248–1254. [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, A.D.; Callender, M.; Harvill, E.T. Generating Enhanced Mucosal Immunity against Bordetella Pertussis: Current Challenges and New Directions. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Huang, L.; Luo, S.; Qiao, R.; Liu, F.; Li, X. A Novel Vaccine Formulation Candidate Based on Lipooligosaccharides and Pertussis Toxin against Bordetella Pertussis. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.A.; Boehm, D.T.; DeJong, M.A.; Wong, T.Y.; Sen-Kilic, E.; Hall, J.M.; Blackwood, C.B.; Weaver, K.L.; Kelly, C.O.; Kisamore, C.A.; et al. Intranasal Immunization with Acellular Pertussis Vaccines Results in Long-Term Immunity to Bordetella Pertussis in Mice. Infect Immun 2021, 89. [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.I.; Cherry, J.D.; Chang, S.-J.; Partridge, S.; Lee, H.; Treanor, J.; Greenberg, D.P.; Keitel, W.; Barenkamp, S.; Bernstein, D.I.; et al. Efficacy of an Acellular Pertussis Vaccine among Adolescents and Adults. New England Journal of Medicine 2005, 353, 1555–1563. [CrossRef]

- Klein, N.P.; Bartlett, J.; Rowhani-Rahbar, A.; Fireman, B.; Baxter, R. Waning Protection after Fifth Dose of Acellular Pertussis Vaccine in Children. New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 367. [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, S.; McIntyre, P.; Liu, B.; Fathima, P.; Snelling, T.; Blyth, C.; Klerk, N. de; Moore, H.; Gidding, H. Pertussis Burden and Acellular Pertussis Vaccine Effectiveness in High-Risk Children. Vaccine 2022, 40. [CrossRef]

- Knuutila, A.; Dalby, T.; Ahvenainen, N.; Barkoff, A.M.; Jørgensen, C.S.; Fuursted, K.; Mertsola, J.; He, Q. Antibody Avidity to Pertussis Toxin after Acellular Pertussis Vaccination and Infection. Emerg Microbes Infect 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Gregg, K.A.; Merkel, T.J. Pertussis Toxin: A Key Component in Pertussis Vaccines? Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11, 557. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, P.; Borkner, L.; Jazayeri, S.D.; McCarthy, K.N.; Mills, K.H. Nasal Vaccines for Pertussis. Curr Opin Immunol 2023, 84.

- Dewan, K.K.; Linz, B.; DeRocco, S.E.; Harvill, E.T. Acellular Pertussis Vaccine Components: Today and Tomorrow. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8, 217. [CrossRef]

- Munoz, F.M. Safer Pertussis Vaccines for Children: Trading Efficacy for Safety. Pediatrics 2018, 142.

- Gilbert, N.L.; Guay, M.; Kokaua, J.; Lévesque, I.; Castillo, E.; Poliquin, V. Pertussis Vaccination in Canadian Pregnant Women, 2018–2019. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 2022, 44. [CrossRef]

- PK, S.; G, S.; B, K.; D, K.; R, B. Public Health Measures for Pertussis Immunization in Pregnancy- A Rationalized Study. Int J Curr Res Rev 2021, 13, 157–161. [CrossRef]

- Vygen-Bonnet, S.; Hellenbrand, W.; Garbe, E.; von Kries, R.; Bogdan, C.; Heininger, U.; Röbl-Mathieu, M.; Harder, T. Safety and Effectiveness of Acellular Pertussis Vaccination during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. BMC Infect Dis 2020, 20, 136. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.X.; Chen, Q.; Yao, K.H.; Li, L.; Shi, W.; Ke, J.W.; Wu, A.M.; Huang, P.; Shen, K.L. Pertussis Detection in Children with Cough of Any Duration. BMC Pediatr 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, R.; Bafna, S.; Choudhary, M.L.; Reddy, M.; Katendra, S.; Maheshwari, S.; Jadhav, S. Looking beyond Pertussis in Prolonged Cough Illness of Young Children. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Skirda, T.A.; Borisova, O.Y.; Borisova, A.B.; Kombarova, S.Y.; Pimenova, A.S.; Gadua, N.T.; Chagina, I.A.; Petrova, M.S.; Kafarskaya, L.I. Determination of Anti-Pertussis Antibodies in Schoolchildren with Long-Term Cough. Jurnal Infektologii 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Duterme, S.; Vanhoof, R.; Vanderpas, J.; Pierard, D.; Huygen, K. Serodiagnosis of Whooping Cough in Belgium: Results of the National Reference Centre for Bordetella Pertussis Anno 2013. Acta Clin Belg 2016, 71, 86–91. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.M.; Simon, A.; Thomas, S.; Tunali, A.; Satola, S.; Jain, S.; Farley, M.M.; Tondella, M.L.; Skoff, T.H. Evaluation of Asymptomatic Bordetella Carriage in a Convenience Sample of Children and Adolescents in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.D. The Prevention of Severe Pertussis and Pertussis Deaths in Young Infants. Expert Rev Vaccines 2019, 18, 205–208. [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Wang, L.; Du, S.; Fan, H.; Yu, M.; Ding, T.; Xu, X.; Zhang, D.; Huang, L.; Lu, G. Mortality Risk Factors among Hospitalized Children with Severe Pertussis. BMC Infect Dis 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, H.; Xu, F. Risk Factors Associated with Death in Infants <120 Days Old with Severe Pertussis: A Case-Control Study. BMC Infect Dis 2020, 20, 852. [CrossRef]

- Althouse, B.M.; Scarpino, S. V. Asymptomatic Transmission and the Resurgence of Bordetella Pertussis. BMC Med 2015, 13, 146. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The correlations between baseline variable parameters. BPV = Bordetella pertussis vaccine, F – female, M – male, RT-PCR - reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, ELISA – serological diagnosis.

Figure 1.

The correlations between baseline variable parameters. BPV = Bordetella pertussis vaccine, F – female, M – male, RT-PCR - reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, ELISA – serological diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Correlations between variable parameters: A. co-detected pathogens with RSB; B. the main clinical manifestations with RSB; C. Clinical manifestation with co-detected pathogens. RSB = Respiratory symptoms claimed before presentation in ECU (days); SARS-CoV2 – Coronavirus type 2; HPIV-3 - Human parainfluenza virus type 3; HAdVs - Human adenovirus; MS – Measles virus; RSV - Respiratory syncytial virus; ARDS - Acute respiratory distress syndrome (respiratory failure); O2 DS - Oxygen desaturation.

Figure 2.

Correlations between variable parameters: A. co-detected pathogens with RSB; B. the main clinical manifestations with RSB; C. Clinical manifestation with co-detected pathogens. RSB = Respiratory symptoms claimed before presentation in ECU (days); SARS-CoV2 – Coronavirus type 2; HPIV-3 - Human parainfluenza virus type 3; HAdVs - Human adenovirus; MS – Measles virus; RSV - Respiratory syncytial virus; ARDS - Acute respiratory distress syndrome (respiratory failure); O2 DS - Oxygen desaturation.

Figure 3.

The correspondence between radiological findings and the illness severity: A. Total sample; B. Clinical cure; C. Death; D. Transfer. C-X-ray 1 -Accentuated interstitial pattern below the hilum bilaterally; C-X-ray 2 – Alveolar Opacities Around and Below the Right Hilum; C-X-ray 3 - Bilateral pulmonary infiltrate; C-X-ray 4 - Blurring of the right basal pulmonary field: C-X-ray 5 - Congestive Pulmonary Hila, Microalveolar and Reticular Opacities Around and Below the Hilum Bilaterally; C-X-ray 6 - Enlarged Congestive Hila, Confluent Alveolar Opacities Around the Left Hilum and Below the Hilum Bilaterally; C-X-ray 7 - Right pulmonary consolidation process; C-X-ray 8- Widespread, homogeneous opacities of medium intensity, with blurred margins, showing air bronchograms, located in the upper third of both lung fields and left retrocardiac area—indicative of pulmonary infiltrates.

Figure 3.

The correspondence between radiological findings and the illness severity: A. Total sample; B. Clinical cure; C. Death; D. Transfer. C-X-ray 1 -Accentuated interstitial pattern below the hilum bilaterally; C-X-ray 2 – Alveolar Opacities Around and Below the Right Hilum; C-X-ray 3 - Bilateral pulmonary infiltrate; C-X-ray 4 - Blurring of the right basal pulmonary field: C-X-ray 5 - Congestive Pulmonary Hila, Microalveolar and Reticular Opacities Around and Below the Hilum Bilaterally; C-X-ray 6 - Enlarged Congestive Hila, Confluent Alveolar Opacities Around the Left Hilum and Below the Hilum Bilaterally; C-X-ray 7 - Right pulmonary consolidation process; C-X-ray 8- Widespread, homogeneous opacities of medium intensity, with blurred margins, showing air bronchograms, located in the upper third of both lung fields and left retrocardiac area—indicative of pulmonary infiltrates.

Figure 4.

The correlations between clinical laboratory analyses, radiological examination, complications, and hospitalization period. PBS – peripheral blood smear – all PBS abnormalities were detailed in the Supplementary Material. CRP – C reactive protein: normal <0.4 mg/mL; moderately increased 0.4 – 1.0 mg/mL; high level: 1.1 – 10 mg/mL; C-complications; WBCs – white blood cells; Lym – Lymphocytes; C-X-ray – Chest radiography; HD – hospitalization days.

Figure 4.

The correlations between clinical laboratory analyses, radiological examination, complications, and hospitalization period. PBS – peripheral blood smear – all PBS abnormalities were detailed in the Supplementary Material. CRP – C reactive protein: normal <0.4 mg/mL; moderately increased 0.4 – 1.0 mg/mL; high level: 1.1 – 10 mg/mL; C-complications; WBCs – white blood cells; Lym – Lymphocytes; C-X-ray – Chest radiography; HD – hospitalization days.

Figure 5.

Correlations between therapy and clinical outcomes on pediatric patients. PICU – pediatric intensive care unit; Dex – Dexamethasone; HHC – Hydrocortisone hemisuccinate; Neb.Adr. – Nebulised Adrenaline; HFNCO2 – High Flow nasal cannula Oxygen Therapy; LFNCO2 – Low Flow nasal cannula Oxygen Therapy.

Figure 5.

Correlations between therapy and clinical outcomes on pediatric patients. PICU – pediatric intensive care unit; Dex – Dexamethasone; HHC – Hydrocortisone hemisuccinate; Neb.Adr. – Nebulised Adrenaline; HFNCO2 – High Flow nasal cannula Oxygen Therapy; LFNCO2 – Low Flow nasal cannula Oxygen Therapy.

Figure 6.

Correlations between baseline data and clinical outcomes on pediatric patients. RSB – Respiratory symptoms before presentation in ECU; HD – Hospitalization days, C = Complications; PICU – pediatric intensive care unit; BPV – B. pertussis vaccination.

Figure 6.

Correlations between baseline data and clinical outcomes on pediatric patients. RSB – Respiratory symptoms before presentation in ECU; HD – Hospitalization days, C = Complications; PICU – pediatric intensive care unit; BPV – B. pertussis vaccination.

Table 1.

Baseline data of the pediatric patients' group (n = 38).

Table 1.

Baseline data of the pediatric patients' group (n = 38).

| Aspect |

Total |

F |

M |

p-value |

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Total |

38 |

100 |

19 |

50 |

19 |

50 |

|

| Age (years) |

< 1 year |

17.00 |

44.74 |

6.00 |

31.58 |

11.00 |

57.89 |

< 0.05 |

| 1-3 years |

14.00 |

36.84 |

8.00 |

42.11 |

6.00 |

31.58 |

| 4-8 years |

4.00 |

10.53 |

4.00 |

21.05 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| 9-13 years |

3.00 |

7.89 |

1.00 |

5.26 |

2.00 |

10.53 |

| Residence |

Rural |

17.00 |

44.74 |

7.00 |

36.84 |

10.00 |

52.63 |

< 0.05 |

| Urban |

21.00 |

55.26 |

12.00 |

63.16 |

9.00 |

47.37 |

|

B. pertussis vaccination |

No |

31.00 |

81.58 |

16.00 |

84.21 |

15.00 |

78.95 |

> 0.05 |

| Yes |

7.00 |

18.42 |

3.00 |

15.79 |

4.00 |

21.05 |

|

B. pertussis diagnosis |

ELISA |

6.00 |

15.79 |

4.00 |

21.05 |

2.00 |

10.53 |

< 0.05 |

| qPCR |

32.00 |

84.21 |

15.00 |

78.95 |

17.00 |

89.47 |

Table 2.

Associated pathogens and clinical manifestations correlated with respiratory symptoms claimed before presentation (RSB) in the Emergency Care Unit (days).

Table 2.

Associated pathogens and clinical manifestations correlated with respiratory symptoms claimed before presentation (RSB) in the Emergency Care Unit (days).

| Aspect |

Total |

Respiratory symptoms claimed before presentation in ECU (days) |

| No |

1-3 days |

4-9 days |

10-14 days |

>20 days |

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Total |

38 |

100 |

2 |

5.26 |

7 |

18.42 |

12 |

31.58 |

12 |

31.58 |

5 |

13.16 |

| Viruses |

| EV-HRV |

12.00 |

31.58 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

3.00 |

42.86 |

3.00 |

25.00 |

3.00 |

25.00 |

3.00 |

60.00 |

| HPIV-3 |

2.00 |

5.26 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

14.29 |

1.00 |

8.33 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| SARS-CoV2 |

5.00 |

13.16 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

2.00 |

28.57 |

3.00 |

25.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| HAdVs |

1.00 |

2.63 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

8.33 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| MV |

1.00 |

2.63 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

20.00 |

| RSV |

1.00 |

2.63 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

14.29 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Other pathogens |

| S. pneumoniae |

7.00 |

18.42 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

14.29 |

6.00 |

50.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| M. pneumoniae |

1.00 |

2.63 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

8.33 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| P. jirovecii |

1.00 |

2.63 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

8.33 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| CM |

| Fever |

16.00 |

42.11 |

1.00 |

50.00 |

4.00 |

57.14 |

5.00 |

41.67 |

3.00 |

25.00 |

3.00 |

60.00 |

| ARDS |

23.00 |

60.53 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

5.00 |

71.43 |

7.00 |

58.33 |

7.00 |

58.33 |

4.00 |

80.00 |

| Rhinorrhea |

14.00 |

36.84 |

1.00 |

50.00 |

4.00 |

57.14 |

5.00 |

41.67 |

2.00 |

16.67 |

2.00 |

40.00 |

| O2 DS |

7.00 |

18.42 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

3.00 |

42.86 |

4.00 |

33.33 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Emesis |

7.00 |

18.42 |

1.00 |

50.00 |

1.00 |

14.29 |

4.00 |

33.33 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

20.00 |

| Rash |

1.00 |

2.63 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

20.00 |

Table 3.

Clinical laboratory analyses, radiological examination, complications, and hospitalization period.

Table 3.

Clinical laboratory analyses, radiological examination, complications, and hospitalization period.

| Parameter |

Total |

Outcome |

| Clinical cure |

Deceased |

Transfer |